Introduction

The administration of medicines and other products, including blood, remains a critical component of prehospital care. Given the uniquely dynamic nature of prehospital practice, including continuous variation in environmental temperature, maintaining optimal conditions for storage of drugs and other products is uniquely challenging. Poor temperature control has been shown to reduce drug efficacy and potency Reference Grant, Carroll and Church1–Reference Gammon, Su and Huckfeldt4 with potential implications for patient safety. This becomes particularly concerning when considering the potential for prolonged exposure to extremely high vehicle temperatures in the context of a greenhouse effect inside vehicles. Reference Helm, Castner and Lampl5,Reference Madden, O’Connor and Evans6 Studying the relationship between climate and the temperature inside emergency vehicles across different regions will help guide the development of strategies for effective drug storage and improve the quality and safety of prehospital emergency care.

The aim of this study was to monitor temperatures in emergency vehicles at a helicopter Emergency Medical Service (EMS) in the east of England region to provide insights into the extent to which the climate of this region might compromise the viability of drugs carried in emergency vehicles and the impact of different operational strategies on vehicle temperatures. In this study, temperature probes were deployed in vehicles at Essex & Herts Air Ambulance (EHAAT; Essex, United Kingdom) and data relating to temperature variation and the duration of exposure to temperatures exceeding manufacture-recommended conditions were collected. These data were subsequently used to inform the local standard operating procedure at EHAAT for drug storage while vehicles are operational.

Methods

A single-center prospective observational study was conducted to determine the storage temperatures of drugs in emergency vehicles. Data were gathered over a 12-month period spanning from September 2022 through August 2023. ALTA Industrial Wireless continuous recording temperature sensors (Monnit Corporation; South Salt Lake, Utah USA) were used, which have an operating range of −40°C to 85°C and are accurate to ±1°C (as stated by the manufacturer). Seasonal study periods were defined as per the Met Office (Exeter, Devon, United Kingdom) Meteorological Guidance: Summer = June 1st – August 31st; Autumn = September 1st – November 30th; Winter = December 1st – February 28th; and Spring = March 1st – May 31st. External ambient data were obtained from the Writtle Weather Station, which is located in Essex, and is an equal distance from the two bases from which EHAAT operates. Information relating to the Writtle Weather Station was accessed via the Met Office Integrated Data Archive System (MIDAS) Open Dataset Pages in the Centre for Environmental Data Analysis (CEDA; Didcot, South Oxfordshire, United Kingdom) data catalogue. This data set provided absolute daily minimum and daily maximum temperatures.

Two types of vehicles were included as part of this study: an Agusta Westland 169 (AW169; Leonardo Helicopters, Italy) helicopter and five rapid response vehicle (RRV) Volvo XC90 cars (Volvo Car; Gothenburg, Sweden). A temperature probe housed within a carry pouch was placed in each of these vehicles within close proximity to the location of the medicines.

The aircraft was kept outside on a ground-level airfield helipad during the day and stored in a hangar overnight. Temperature control in the hangar operates via radiant panels arranged on each side of the hanger. The space temperature of the hangar is monitored by sensors located on the walls which provide heating if the hangar temperature falls below setpoint. The hangar radiant panels were placed at a set point minimum of 16°C with the heating activating at 20°C (to maintain a temperature above 16°C). This system is able to heat but does not provide any cooling. Due to annual servicing requirements, it was not possible to collect data from the AW169 aircraft during the months of September 2022 and both July and August 2023. Furthermore, the aircraft was occasionally taken offline, during which time it was kept inside the hangar. Reasons for hangaring the aircraft included poor weather, maintenance, and unavailability of personnel. This accounted for 15 days in total of the study period.

Operational land-based vehicles (RRV05, RRV06, RRV07, and RRV08) were generally kept inside a garage whilst at base and between taskings, but they were also left outside for periods. A probe was also placed in a spare vehicle (RRV02) which was permanently stationed outside. This allowed comparison between the two different vehicle stationing strategies to determine whether indoor storage of vehicles between taskings offered some protection from extreme temperature changes. Temperature probes continued to record even while vehicles were responding to taskings away from base to reflect actual and real time temperature changes to which drugs were exposed. All RRVs were Volvo XC90s and each probe was placed in a small bag located in the boot of each vehicle, in close proximity to the location of the drugs pouch. This aimed to replicate the conditions to which drugs were exposed when inside the vehicles.

Each sensor was set to record every 30 minutes, 24 hours a day. If the temperature recorded by the sensor exceeded pre-set parameters, an alert would be automatically triggered and sent to both the duty doctor phone and a member of the clinical management team who could take appropriate action. Manufacturer instructions for drugs being carried stated storage at either “room temperature” or “refrigerated temperature;” alert parameters for each sensor were informed by the United States Pharmacopeial Convention (United States Pharmacopeia; Bethesda, Maryland USA) definition for these conditions. Recordings of 25°C or above triggered a “Too Hot” alert while temperatures below 2°C triggered a “Too Cold” alert. Given the 30-minute interval between each temperature recording, when analyzing the data, it was assumed that any temperature excursion was maintained until the next temperature recording.

Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp.; Redmond, Washington USA) was used to extract and process the data by three-month intervals, corresponding to each respective weather season. For each sensor, daily mean, median, maximum, and minimum temperatures, as well as number of alerts triggered, were recorded. Both mean and median values have been included in the analysis for a complete and comprehensive review. Pearson correlation coefficient was determined to assess the correlative relationship between vehicle and environmental temperatures. The study did not involve any patients and ethical board review was not required.

Results

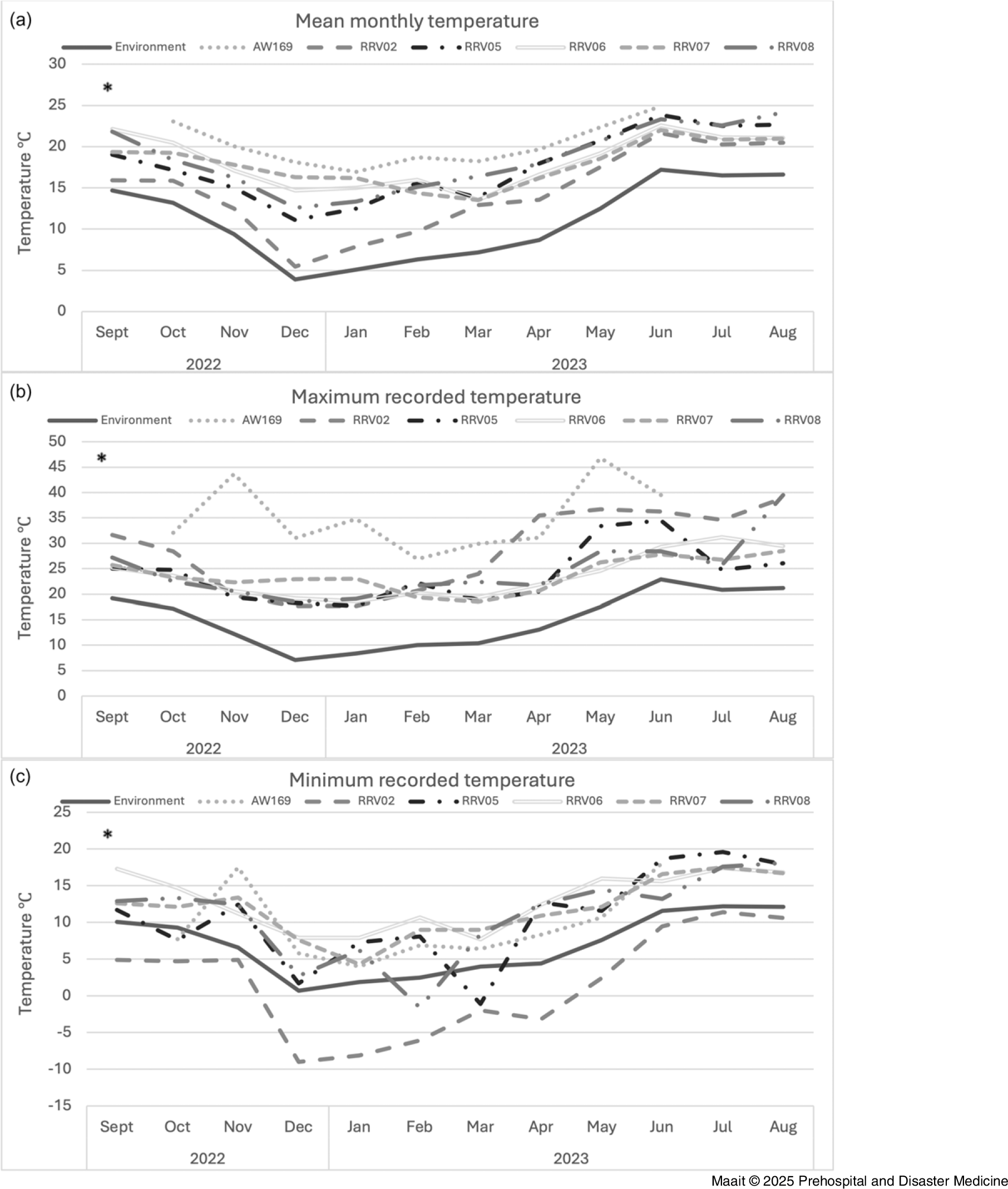

Over a twelve-month period and across all six vehicles, a total of 102,524 temperature readings were recorded with an overall temperature range of −9°C to 46.8°C. Figure 1a, 1b, 1c, and 1d display the monthly mean, median, maximum, and minimum temperatures, respectively, across all vehicles. Table 1 displays the same data but in a seasonal distribution. Monthly mean and median temperature in the AW169 almost reached the upper limit of 25°C, recording both the highest mean and median value of 24.9°C during the month of June in the summer period. Monthly mean and median values for all other vehicles remained within range throughout the observation period – the lowest mean (7.9°C) and median (7.7°C) value was recorded in the RRV02. Both absolute (MeanAbsolute, MedianAbsolute, MinimumAbsolute, MaximumAbsolute) and mean (MeanMean, MinimumMean, MaximumMean) temperatures across the four active RRVs with similar operating patterns (RRV05, RRV06, RRV07, and RRV08) were comparable and remained in a similar range.

Figure 1. Monthly Temperature Trends. (1a) Mean Monthly Temperature: Average of All Temperature Recordings for Each Month. (1b) Monthly Maximum Temperature: Highest Temperature Reading Recorded Each Month. (1c) Monthly Minimum Temperature: Lowest Temperature Reading Recorded Each Month.

Note: AW169 refers to an Augusta Westland 169 helicopter operated by Essex & Herts Air Ambulance. RRV02 refers to a ground based rapid response vehicle operated by Essex & Herts Air Ambulance as spare vehicle. RRV05, RRV06, RRV07, and RRV08 refer to ground-based rapid response vehicles operated by Essex & Herts Air Ambulance.

*No data available for the aircraft during the months of September 2022 and July & August 2023.

**Environmental temperature from the Writtle Station as per the Met Office Integrated Data Archive System (MIDAS).

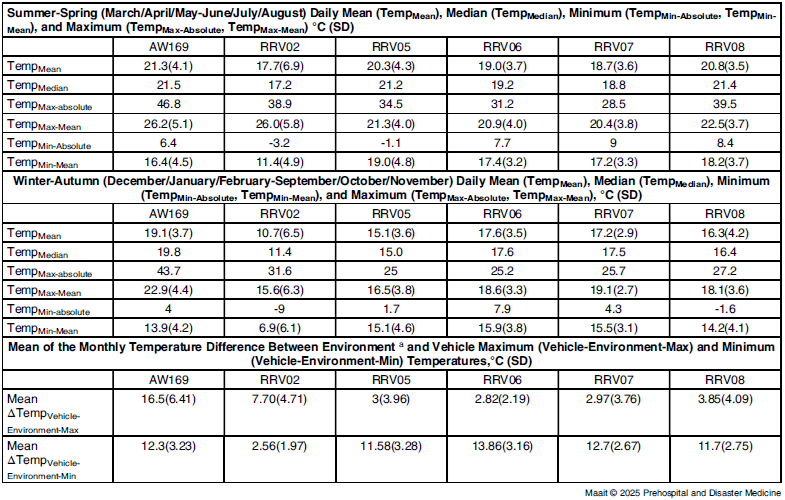

Table 1. Seasonal Trends in Internal Vehicle Temperatures Recorded from Emergency Response Vehicles Operating in the East of England

Note: AW169 refers to an Augusta Westland 169 helicopter operated by Essex & Herts Air Ambulance; RRV02 refers to a ground-based rapid response vehicle operated by Essex & Herts Air Ambulance as spare vehicle; RRV05, RRV06, RRV07, and RRV08 refer to ground-based rapid response vehicles operated by Essex & Herts Air Ambulance.

a Environmental temperature from the Writtle Station as per the Met Office Integrated Data Archive System (MIDAS).

Maximum temperature values within the vehicles ranged from 17.7°C to 46.8°C (Figure 1 and Table 1). Maximum temperatures across all six vehicles were persistently greater than the outside air temperatures (Figure 1 and Table 1), particularly in the AW169 aircraft and the RRV02 vehicle. The highest maximum temperature of 46.8°C was reached in the AW169 during the month of May (Figure 1). The corresponding environmental maximum temperature for that month was 20.9°C. Maximum temperatures were persistently higher across all vehicles compared to environmental temperature (Figure 1), and this pattern was maintained throughout the year but was most pronounced during the winter months (December-February). All vehicles experienced temperature excursions exceeding 25°C during the year; this was most prominently seen in the months of May, June, and July. Of note, the maximum recorded temperature of most vehicles dipped in July 2023 before rising again (Figure 1). This coincides with July 2023 being one of the United Kingdom’s wettest on record, whilst June 2023 was one of the warmest and sunniest, as per the Met Office climate summary report for the summer of 2023. 7

Minimum temperature values ranged from −9°C to 19.6°C (Figure 1 and Table 1). The coldest temperature of −9°C was recorded in the RRV02 during the month of December with the corresponding minimum environmental temperature for that month being −12.2°C. The temperature in most vehicles was largely maintained at levels higher than that of the environment and remained mostly above 2°C. The RRV02 deviated from this pattern and instead minimum temperatures were consistently below 2°C in the winter months and more closely matched environmental temperatures.

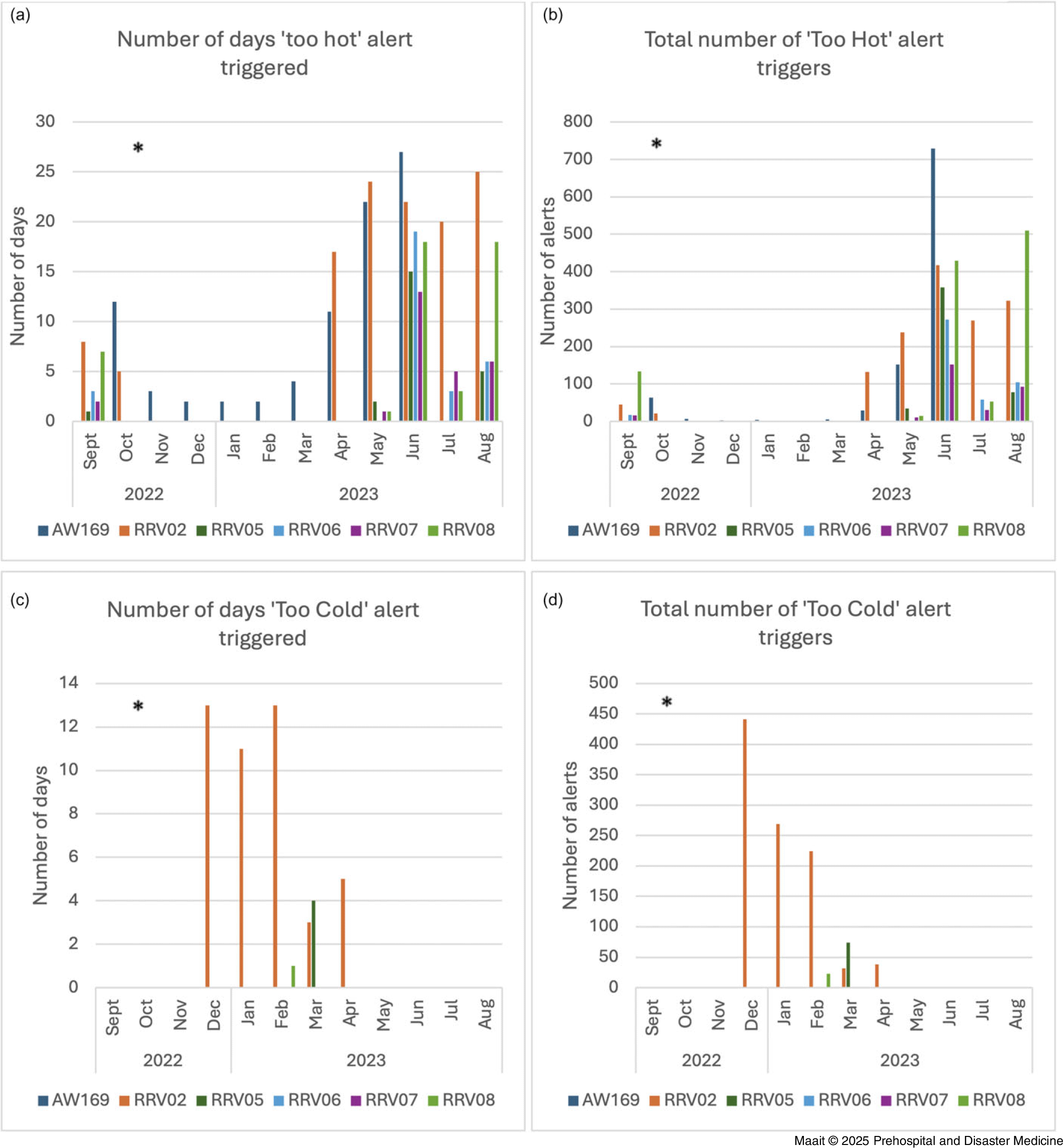

Figure 2a and 2c show the number of days each month which featured a temperature alert; the total number of alerts triggered each month is shown in Figure 2b and 2d – each alert corresponded to a half-hour period during which it was assumed that the temperature recorded was maintained. The “Too Hot” alert was most commonly triggered by the AW169 (9/9 months) followed by the RRV02 (7/12 months). “Too Hot” alerts were most frequently triggered during the month of June on the AW169. A total of 729 alerts (Figure 2) were observed, corresponding to approximately 364 hours of temperatures outside of the recommended range across 27 days (90%) of the month (Figure 2). Conversely, “Too Cold” alerts were most commonly triggered in the RRV02 during the month of December. In total, 441 triggered (Figure 2) – corresponding to approximately 220 hours – across 13 days (43%) of the month (Figure 2).

Figure 2. “Too Hot” and “Too Cold” Alert Patterns. (2a) Frequency of “Too Hot” Alerts on Monthly Basis, Showing Number of Days Each Month when Alert was Triggered. (2b) Cumulative Total of “Too Hot” Alerts Triggered Each Month. (2c) Frequency of “Too Cold” Alerts on Monthly Basis, Showing Number of Days Each Month when Alert was Triggered. (2d) Cumulative Total of “Too Cold” Alerts Triggered Each Month.

Note: AW169 refers to an Augusta Westland 169 helicopter operated by Essex & Herts Air Ambulance. RRV02 refers to a ground based rapid response vehicle operated by Essex & Herts Air Ambulance as spare vehicle. RRV05, RRV06, RRV07, and RRV08 refer to ground-based rapid response vehicles operated by Essex & Herts Air Ambulance.

*No data available for the aircraft during the months of September 2022 and July & August 2023.

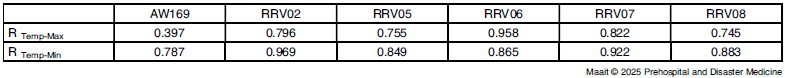

All vehicles showed a moderate-to-strong positive correlation with environmental temperatures (Table 2). Interestingly, maximum temperatures in the AW169 showed the weakest correlation with environmental temperatures. This might suggest a greenhouse effect (whereby sunlight entering through the windshields heats up air, which is trapped inside the vehicle) created within the AW169, leading to higher and less predictable temperatures.

Table 2. Pearson Correlation Coefficient (R) between Monthly Maximum (Temp-Max) and Minimum (Temp-Min) Temperature Values from Each Emergency Response Vehicle as Compared to the Environmental Monthly Maximum and Minimum Temperatures, Respectively

Note: AW169 refers to an Augusta Westland 169 helicopter operated by Essex & Herts Air Ambulance; RRV02 refers to a ground-based rapid response vehicle operated by Essex & Herts Air Ambulance as spare vehicle; RRV05, RRV06, RRV07, and RRV08 refer to ground-based rapid response vehicles operated by Essex & Herts Air Ambulance.

Environmental temperature from the Writtle Station as per the Met Office Integrated Data Archive System (MIDAS).

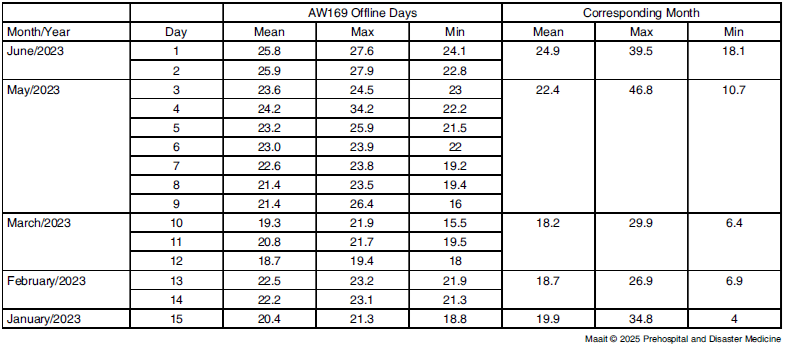

Results for the days during which the aircraft was hangered showed similar mean temperature values when compared to the mean temperature values across other days during the same month. However, a notable difference was observed in the form of lower maximum and higher minimum temperature values reached on those days as compared to the remaining days for that month (Table 3).

Table 3. Mean, Maximum, and Minimum Temperatures in AW169 for Days Aircraft was Hangered and Corresponding Aircraft Temperature Values for the Remainder of that Month

Note: AW169 refers to an Augusta Westland 169 helicopter operated by Essex & Herts Air Ambulance.

Discussion

The overall range of temperatures encountered (-9°C to 46.8°C) is comparable to those seen in other studies. A study from the south of Germany by Helm, Castner, and Lampl Reference Helm, Castner and Lampl5 reported a temperature range of −13.2°C to 50.6°C, while in Shropshire, United Kingdom, Smith, et al Reference Smith, Doughty, Bishop, Herbert and Nash8 with the Midlands Air Ambulance reported a temperature range of −0.3°C to 60.6°C. Similar findings have also been reported by veterinary colleagues: Carter, et al Reference Carter, Hall, Connolly, Russell and Mitchell9 reported a temperature range of −7.4°C to 54.7°C in vehicles used for transport of dogs and drugs in the East Midlands (United Kingdom), while Ondrak, et al Reference Ondrak, Jones and Fajt10 reported temperatures of up to 54.4°C within veterinary practice vehicles in Texas (USA) – highlighting the prevalence and scale of this issue.

The current results show that all vehicles experienced temperatures exceeding manufacturer recommendations for “controlled room temperature,” as outlined by the United States Pharmacopeial Convention Reference Madden, O’Connor and Evans6,Reference Brown, Krumperman and Fullagar11 – in line with findings from other studies across various climates.11-14 An existing body of work has demonstrated the susceptibility of several drugs used in prehospital medicine to the effects of temperature variation – particularly high temperatures. McMullan, et al Reference McMullan, Jones and Barnhart15 distributed study boxes containing vials of midazolam, diazepam, and lorazepam across four active EMS units before using liquid chromatography at 30-day intervals to determine drug concentration – they concluded that lorazepam experienced significant degradation after 120 days. Armenian, et al Reference Armenian, Campagne and Stroh2 investigated the thermal stability of prehospital medication by exposing eight different medications (atropine, diphenhydramine, fentanyl, hydromorphone, midazolam, morphine, naloxone, and ondansetron) to various temperature exposure regimes. They found that atropine and naloxone showed heat dependent degradation, with atropine being undetectable after four weeks of heat exposure. Similarly, Grant et al Reference Grant, Carroll and Church1 studied the extent of temperature-dependent degradation on two different epinephrine concentrations (1:1,000 and 1:10,000). Grant, et al Reference Grant, Carroll and Church1 observed a significant loss of concentration of the parent compound of 1:10,000 epinephrine after eight weeks of heat treatment.

Better temperature control was achieved in RRV05-RRV08 vehicles as compared to the RRV02. Given that all vehicles are of the same make and model, this can be attributed to whether or not the vehicles were stationed indoors between taskings. The RRV02 was the only RRV that remained outdoors at all times, and as the fleet spare, it was utilized less frequently. Indoor storage of the other RRVs between taskings did help to reduce the occurrence of temperature alerts. It was particularly effective at protecting from extreme low temperatures within the vehicles but less effective when it came to extreme high temperatures. This impact of indoor storage is further supported by the finding of less variation among mean, mean maximum, and mean minimum temperature (TempMean, TempMax-Mean, and TempMin-Mean) between those vehicles, as well as smaller and more consistent differences between maximum vehicle and environment temperature (ΔTempVehicle-Environment-Max) values in the RRV05-RRV08 vehicles compared to RRV02. By comparing maximum and minimum temperatures on days when the AW169 was non-operational and hangared, similar conclusions regarding the protective effect of indoor storage from extreme temperatures (as observed in the RRVs) can be drawn. The effectiveness of indoor storage is also supported by a study by Allegra, et al Reference Allegra, Brennan, Lanier, Lavery and MacKenzie14 conducted in northern New Jersey (USA) whereby temperature monitors were distributed within prehospital medication boxes across various locations. They observed that, when stored within climate-controlled garages, prehospital medications were less prone to thermal injury and freezing.

The AW169 showed similarly poor temperature control to the RRV02, in contrast to the other vehicles. However, while it is possible to draw direct comparisons between the RRVs, this is more difficult with the aircraft given the completely different structure of the AW169 as well as its different operating patterns (stationed outside during the day and inside a hangar during the night). Nonetheless, some conclusions can be drawn from the pattern of the data: notably, the AW169 seemed far more susceptible to the effects of high temperature. It is likely that this is due to a larger greenhouse effect in the AW169, possibly a result of its structure and the materials from which it is composed. Other factors such as heat generated from the significantly larger engines of the helicopter may also have contributed to such high temperatures. It is unclear whether these phenomena are unique to the design of the AW169 or if this is a theme across helicopters, as well as the extent to which positioning of the probes within the aircraft may have had an impact. Smith, et al Reference Smith, Doughty, Bishop, Herbert and Nash8 undertook a study to map temperatures across different parts of a H145 helicopter used as part of their emergency service. They observed significant temperature differences across various positions within the aircraft itself, thereby demonstrating the importance for robust aircraft-specific temperature mapping within prehospital services to guide safe storage of medication inside the aircraft.

Environmental temperatures, although positively correlated with the vehicle temperatures (Table 2), were often unreliable in predicting the temperature reached inside vehicles and drug pouches, particularly on hotter days, suggesting that environmental temperature should be used cautiously to anticipate conditions to which drugs will be exposed. The greatest difference between environment and vehicle temperatures is seen when comparing maximum temperatures, which likely reflects the significant role of the greenhouse effect in influencing temperatures inside vehicles. A study by Madden, et al Reference Madden, O’Connor and Evans6 monitored temperatures inside two Bell 407 helicopters in Fort Worth, Texas (USA) and they too found only a moderate correlation between temperatures inside drug bags and ambient temperatures. They suggested both the greenhouse effect (given large glass windows on either side of the rear cabin) and low call volumes (with subsequently less frequent ventilation) as possible explanations.

Consistently high temperatures present a challenge for prehospital medical teams, and these results indicate that helicopters might be intrinsically more susceptible to high temperatures compared to land-based vehicles. Equally, extremely low temperatures might pose a serious risk to the integrity of medication, and it is clear that, for vehicles stationed outdoors, freezing temperatures occur frequently during the winter months. Ensuring, where possible, that vehicles are kept indoors while idle is one strategy that would be effective as a protective measure. Alternatively, keeping medication bags indoors between periods of operational activity is likely to be equally as protective from extreme highs and lows of temperature; however, this might impact operational efficiency in a role where timely response to callouts is essential. Other strategies to consider include the use of insulated or heated/cooled compartments inside kit bags and transport vehicles. This has been validated by Dubois Reference DuBois16 who compared the effectiveness of temperature control on rescue vehicles between mechanically cooled and non-mechanically cooled compartments. Dubois found that storage within cooled compartments maintained drugs at or below manufacturers’ recommended temperatures as opposed to non-cooled compartments which did not. Dubois concluded that keeping drugs in non-cooled medical bags did not amount to safe storage during the summer months. Horak, et al Reference Horak, Haberleitner and Schauberger17 went further by studying transport boxes under lab conditions to help improve compliance to standards for drug storage within veterinary practice. They concluded a series of recommendations, which include: thermal preconditioning of storage boxes with thermal packs; regular monitoring of temperature inside boxes; and that insulated transport boxes are not suitable for use to store drugs over 12 hours.

It is important that prehospital care providers as well as health care regulators take note of findings such as these to inform local practices. An example of this is seen in New Jersey (USA) where the State Office of Emergency Medical Services issued regulations regarding temperature control and monitoring standards for prehospital medication in response to a study which identified that medications were often stored outside of the recommended temperature range. Reference Mehta, Doran, Lavery and Allegra18 The authors of the study then conducted a state-wide re-survey of mobile intensive care units and found that most services had changed their practices and implemented effective measures for controlling and monitoring prehospital medication storage temperature. Reference Mehta, Doran, Lavery and Allegra18 More work is needed to understand the precise mechanisms through which environmental conditions impact the storage of medicines deployed in the prehospital setting, and how to control for these factors such that climate-specific guidelines for medication storage in prehospital care can be produced. The factors contributing to higher temperatures in the helicopter as compared to the land-vehicles should be explored to determine if higher temperatures are reached in helicopters generally, or if this is unique to the AW169. Prehospital emergency service providers and regulators should also seek to work with manufacturers to understand how environmental temperature variations are transmitted throughout vehicles, and to explore structural modifications that could reduce the impact and allow for better temperature control. In some climates where drugs are kept inside vehicles, it might be necessary to have continuous or intermittent temperature monitoring since environmental temperatures are a poor predictor for the temperature inside vehicles. It is essential that prehospital teams have in place systems to control environmental factors and to ensure compliance with regulatory standards for the storage of medication.

Limitations

This is a single-center study, limiting the generalizability and transferability of the results, particularly across other regions and climate zones and other services with different operational strategies. Although unlikely, any temperatures outside of the ALTA industrial sensor’s operating range (-40°C to 80°C) will not have been reported, potentially leading to misrepresentation or under-estimation of extreme temperatures. It is possible that temperature excursions may have also been over-represented, given that this study assumed temperature excursions triggering an alert were maintained for a 30-minute period until the next recording. Furthermore, while the study attempted to account for differences in outdoor versus indoor storage strategies for vehicles, it was unable to control for factors such as insulation, ventilation, and direct exposure to sunlight. Similarly, the use of climate control measures inside the vehicles during operational taskings was not audited during this study.

Conclusion

This study highlights that weather patterns in the east of England lead to temperature changes within emergency vehicles which frequently exceed recommended storage conditions. It also highlights that temperatures inside vehicles, particularly the AW169 aircraft, are consistently greater than ambient temperature and remain greater for a longer period of time. Additionally, indoor storage of vehicles during periods of inactivity offered some protection against extreme low temperatures. These findings may inform strategies for safe medication storage in prehospital care (as they have done at EHAAT), therefore improving the quality and safety of care being delivered.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Essex & Herts Air Ambulance, who allowed the data from their vehicles to be used as part of the study.

Author Contributions

Yousef Maait: Study design; data analysis and interpretation; drafting of manuscript; revision of manuscript.

Laurie Phillipson: Study conception and project supervision; data acquisition; revision of manuscript.

Both authors approved the final manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI)

No AI tools were used in the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest/funding

This research was supported by Essex & Herts Air Ambulance (Essex, United Kingdom). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.