Introduction

Once an election is over, the media get their turn to interpret the voters’ verdict. These news stories often portray some parties as election winners, while naming others as losers of the electoral contest. In majoritarian systems where two‐party systems are common, there tends to be little room for interpretation because the candidate or party winning the majority can be easily identified as election winner. In systems with proportional representation by contrast, assessments of electoral performances are more complex (Plescia, Reference Plescia2019). First, proportional systems often lead to multi‐party systems and no clear majority for a single party. If winning is understood as gaining governmental office, there could be several such perceived winners (see Singh et al., Reference Singh, Karakoç and Blais2012). Second, and related, some of the coalition parties may be comparatively small or may have lost votes compared to previous elections. In other words, these may be perceived as election losers despite their subsequent participation in government. Third, the party with the largest vote share may not automatically be considered an election winner – either because it fared worse than expected, or because other parties, which have considerably increased their support since the last elections, are also considered winners in the eyes of their supporters (see Stiers et al., Reference Stiers, Daoust and Blais2018).

It is likely that such diverging perceptions stem from media coverage. However, we do not know this because existing research has mostly focused on the media coverage during election campaigns given the role media play for electoral behaviour (e.g., Bos et al., Reference Bos, Van der Brug and De Vreese2011; Larsen & Fazekas, Reference Larsen and Fazekas2020; Schuck et al., Reference Schuck, Xezonakis, Elenbaas, Banducci and Vreese2011; Valentino et al., Reference Valentino, Beckmann and Buhr2001). Very little is known about how the media report on the actual election results. The analyses of Hale (Reference Hale1993) and Mendelsohn (Reference Mendelsohn1998) are notable exceptions in this respect. Both studies examine how the media substantiate election results, attributing electoral victories (or defeat) to factors such as policy platforms and campaign strategies. Both studies focus on Anglo‐American countries with plurality voting systems, which – in the absence of ambiguity over election outcomes – may explain their interest in how media provide the basis for the public legitimacy of electoral mandates. Yet, to the best of our knowledge, we are not aware of studies analyzing which parties are portrayed as ‘winners’ or ‘losers’ in the first place; particularly not in countries with proportional representation. This is surprising because citizens’ perceptions of electoral winners and losers affect their satisfaction with democracy (Blais & Gélineau, Reference Blais and Gélineau2007; Nemčok, Reference Nemčok2020; Plescia, Reference Plescia2019; Plescia et al., Reference Plescia, Daoust and Blais2021; Singh et al., Reference Singh, Karakoç and Blais2012) and their perceived legitimacy of government parties (Plescia & Eberl, Reference Plescia and Eberl2021). We know that election campaign coverage can influence voters’ expectations with respect to government formation (Bowler et al., Reference Bowler, McElroy and Müller2021) and affect political trust and satisfaction with democracy (see Banducci & Karp, Reference Banducci and Karp2003; Lelkes, Reference Lelkes2016). The study of media coverage of election results therefore represents a crucial first step in order to understand the potential consequences of this type of media coverage.

The aim of this manuscript is two‐fold: First, we seek to understand the incentives of political journalists to decide to report on the electoral performances of certain political parties and not others in their post‐election news coverage (party news selection). Second, once selected, we are interested in the determinants of portraying these political parties either as electoral winners or as losers of electoral contests (party representation in the news).

Theoretically, we draw on political and media logic to explain variation in the news coverage of political parties’ electoral performance. These are not opposing logics, as both can be simultaneously at play. According to political logic, ‘the needs of the political system and political institutions […] take center stage and shape how political communication is played out, covered, and understood’ (Strömbäck, Reference Strömbäck2008, p. 234). Newsmakers should thus be guided by the parties’ objective electoral performance when covering election results. In turn, media logic entails an accentuation of certain news values, including negativity, conflict and entertainment, in political news reporting (Mazzoleni, Reference Mazzoleni1987, p. 86; Van Aelst et al., Reference Van Aelst, Maddens, Noppe and Fiers2008, p. 196). Due to the mediatization of politics, this incentive has arguably become more important over time for the interpretation of political reality (Mazzoleni, Reference Mazzoleni1987; Strömbäck, Reference Strömbäck2008). Following media logic, as we will elaborate below, news coverage is likely to focus on parties with more radical policy positions.

Empirically, we rely on the most recent European Parliament (EP) election that took place in the (then) 28 European Union (EU) member states between 23 and 26 May 2019. EP elections represent an excellent case for our enquiry. First, all member states are required to organize EP elections in line with the Uniform Electoral Procedure which stipulates that these elections comply with proportional representation.Footnote 1 Therefore, the electoral systems in EP elections are more similar than national elections across countries. Second, the EP election allows us to hold the main election context constant across Europe. This would have been different if we had considered several independent elections across proportional systems as we would have had to account for additional contextual variables.

However, EP elections are also distinct in the sense that they are commonly referred to as second‐order national elections, meaning that party performance tends to be contingent upon domestic rather than European politics (Ehin & Talving, Reference Ehin and Talving2021; Hix & Marsh, Reference Hix and Marsh2011; Reif & Schmitt, Reference Reif and Schmitt1980). Likewise, national media coverage of EP elections tends to be dominated by domestic issues and actors (e.g. Belluati, Reference Belluati2016; Schuck et al., Reference Schuck, Xezonakis, Elenbaas, Banducci and Vreese2011).

Moreover, one important particularity is that the EU political system is not (yet) designed in such a way that it offers ‘government clarity’ (Hobolt & Tilley, Reference Hobolt and Tilley2014, p. 145). The executive (in this case the European Commission) is not directly formed by those parties and politicians that compete (and win) in EP elections. The heads of state or government in the European Council nominate the Commission President and Commissioners who are then subject to approval by the Parliament. This is why the EP has recently tried to advocate a new procedure by which European party families run their campaigns with pan‐European lead candidates for the office as Commission President. Although the procedure has had limited consequences for party campaigning (e.g., Braun & Popa, Reference Braun and Popa2018) and voter behaviour (Gattermann & Marquart, Reference Gattermann and Marquart2020; Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Hobolt and Popa2015), one of these lead candidates (Jean‐Claude Juncker) indeed became Commission President in 2014. The procedure was ignored after the 2019 election when Ursula von der Leyen became Commission President without having been a contender for that office beforehand. However, this outcome was not foreseeable right after the elections. In other words, ‘winning’ one of the most crucial offices at the EU level was still an option at the time of the election. We account for the particularity of EP elections in the theory section and discuss the implications and potential for future research based on media coverage of national elections in the conclusions.

Our sample considers 215 parties having competed in the 2019 EP election. Based on a manual content analysis of 1,955 articles published in a total of 64 newspapers in 16 member states, we identify (a) which parties’ election results are selected for reporting by the media in the days after the election and (b) whether these parties are represented as election winners or losers. Our findings lend support to the applicability of both political and media logic in the news coverage of political parties’ electoral performances underlining that these logics are complementary. In particular, the results show that party ideology matters in addition to the arithmetic of election results. All else being equal, the election results of parties with polarized views on socio‐cultural issues, such as Greens and radical right parties, tend to be selected for news coverage more often and are also more likely to be portrayed as election winners. We conclude that media bias in post‐election coverage creates an uneven playing field in the aftermath of elections and therefore have important implications for future research on citizen satisfaction with democracy and the public legitimacy of political parties.

Journalistic incentives to report on political parties’ electoral performance

Which factors explain variation in the media coverage of the electoral performance of political parties in proportional systems? To answer this question, we distinguish two forms of unequal media coverage: first, not all political parties are equally likely to be reported upon in relation to election results. In systems with proportional representation, a multitude of political parties compete for relatively few seats, which entails that journalists likely make a selection of parties for inclusion in the news. For example, following the 2019 EP election, 749 legislators of a total of 182 domestic parties (plus two independent candidates) from across 28 countries took up their seats in the new Parliament.Footnote 2 Put differently, each country delegation comprised 6.5 parties on average.Footnote 3 Journalists are expected to focus their reporting on those parties whose election results they consider newsworthy, at the expense of others that they may consider less relevant. Second, once selected for reporting, journalists decide how to represent those parties in their news stories. Perceptions of election winners and losers may vary, however, among the electorate in general and party supporters in particular (e.g., Plescia, Reference Plescia2019; Stiers et al., Reference Stiers, Daoust and Blais2018). These divergent perceptions may be a consequence of different representations in news reporting. The baseline assumption of our argumentation, therefore, is that there are particular considerations in journalists’ decisions to represent some parties as election winners and others as election losers.

We draw on the political communication and journalism literature that analyzes incentive structures in the news production process. As journalists may choose to report on a certain political party because they consider it an election winner or loser, we expect that the underlying mechanisms are similar for both the selection and representation of political parties’ electoral performance in post‐election news coverage.Footnote 4 We aim to understand the extent to which political and media logic (Mazzoleni, Reference Mazzoleni1987; Strömbäck, Reference Strömbäck2008) guide the news coverage of election results. Both logics are not necessarily mutually exclusive but can simultaneously be at play. In the following, we explain why.

Political logic and objective electoral performance

Political communication following political logic puts political institutions, political actors and issues at the centre of its reporting (Strömbäck, Reference Strömbäck2008). News production is thus guided by the political reality and what is considered important in the political sphere, and ‘media companies are perceived as political or democratic institutions, with some kind of moral, if not legal, obligation to assist in making democracy work’ (Strömbäck, Reference Strömbäck2008, p. 234). If political logic guides news reporting of election results, we would expect journalists to draw on objective measures of the parties’ electoral performance. Election results provide facts about winners and losers and – in theory – the room for interpretation is relatively small. Thus, journalists are motivated to report accurately on the political reality (see McQuail, Reference McQuail1992). Objective reporting constitutes one major incentive of political journalists, adheres to organizational routines (Tuchman, Reference Tuchman1978) and protects the journalistic profession against criticism (Tuchman, Reference Tuchman1972).

We identify two yardsticks journalists can use to determine election winners and losers based on the arithmetic of election results, namely levels of and changes in electoral support. First, we expect the party winning most votes (i.e., the plurality party) to be more likely declared as an election winner. Winning more votes than all other competitors is arguably one way to define ‘winning’, even if the party falls short of winning an absolute majority in the election, which is not an unlikely outcome in proportional systems. Indeed, voters often identify the plurality party as an election winner (Plescia, Reference Plescia2019; Stiers et al., Reference Stiers, Daoust and Blais2018). If we consider that voters rely on information from the media when they provide such assessments, this may be an indication that journalists do the same. This latter argument rests on the assumption that journalists are incentivized to inform democratic citizens of election outcomes; and the plurality party represents the most unambiguous election result. It follows that journalists are more likely to (a) select the plurality party for inclusion in their news coverage and (b) represent this party as an electoral winner compared to other parties that received fewer votes.

Hypothesis 1 (plurality winner)

H1a (selection): The party winning most votes in the election is more likely to be selected for post‐election news coverage.

H1b (representation): The party winning most votes in the election is more likely to be portrayed as a winner in post‐election news coverage.

Second, journalists are likely to assess parties’ electoral performance relative to that in previous elections. Vote gains also increase the likelihood that voters perceive certain parties as winners of electoral contests (Plescia, Reference Plescia2019; Stiers et al., Reference Stiers, Daoust and Blais2018). For journalists, we expect that vote changes have slightly different effects on the selection and representation of post‐election news coverage. All else being equal, journalists are more likely to focus on those parties with substantial differences in electoral support compared to the previous election. In other words, both vote losses and vote gains should increase the probability that a party's election result is selected for news coverage. In terms of representation, however, the direction of change in electoral support is likely to matter: parties with vote gains are more likely to be portrayed as election winners, while those who lost votes, compared to before, are more likely to be represented as election losers.

In EP elections, journalists can assess vote changes with two potential points of reference: previous EP election results and those of national general elections. Both are reasonable benchmarks to evaluate a party's performance. References to the previous EP election are plausible because the electoral context is the same and many challenger parties have more chances of being elected to the EP compared to the national parliament if electoral systems differ. Prime examples are the British Greens and the United Kingdom Independence Party, who have increased their vote shares in EP elections for which proportional representation applies, while they have hardly any chance to enter the House of Commons given the British First‐Past‐The‐Post electoral system. National elections also offer important reference points for journalists for several reasons: as we discussed at the outset, EP elections have long been described as second‐order national elections (Reif & Schmitt, Reference Reif and Schmitt1980) and mostly the same domestic parties compete in both national and European elections. Lastly, previous national elections tend to be more recent compared to the previous EP election.Footnote 5 The following hypotheses therefore consider European and national elections as a benchmark for the selection and representation of political parties in the post‐election news coverage.

Hypothesis 2 (vote changes: EP election)

H2a (selection): Parties with larger absolute vote changes since the last European election are more likely to be selected for post‐election news coverage.

H2b (representation): Parties with vote gains (losses) since the last European general election are more likely to be portrayed as winners (losers) in post‐election news coverage.

Hypothesis 3 (vote changes: national election)

H3a (selection): Parties with larger absolute vote changes since the last national general election are more likely to be selected for post‐election news coverage.

H3b (representation): Parties with vote gains (losses) since the last national general election are more likely to be portrayed as winners (losers) in post‐election news coverage.

Media logic and the newsworthiness of radical policy platforms

Media logic focuses on other incentives for political communication than political logic. It implies that journalists consider audience‐oriented routines when writing news stories. ‘News values’ are used as a yardstick for what newsmakers believe the audience finds interesting (e.g., Galtung & Ruge, Reference Galtung and Ruge1965; Shoemaker & Reese, Reference Shoemaker1996). Within the media logic paradigm, this concerns particularly those news values involving conflict, negativity, personalization and entertainment (e.g., Brants & van Praag, Reference Brants and Praag2006; Mazzoleni, Reference Mazzoleni1987; Van Aelst et al., Reference Van Aelst, Maddens, Noppe and Fiers2008). Media and political logic are not necessarily mutually exclusive as potential news stories might be politically relevant and attract the interest of larger audiences.Footnote 6 Yet, journalists following media logic prioritize newsworthiness over political relevance. Some argue that media logic has become increasingly relevant in political news coverage (e.g., Brants & van Praag, Reference Brants and Praag2006; Mazzoleni, Reference Mazzoleni1987). Despite such claims of the ‘mediatization of politics’ (Strömbäck, Reference Strömbäck2008), the empirical evidence for an increased importance of news values related to media logic is mixed (e.g., Magin, Reference Magin2015; Vliegenthart et al., Reference Vliegenthart, Boomgaarden, Boumans, Brants and Voltmer2011), also with respect to media coverage of EU politics (Gattermann, Reference Gattermann2018). However, when it comes to how EU politics are framed in the media across Europe, research finds that journalists often apply the conflict frame (e.g., Schuck et al., Reference Schuck, Vliegenthart, Boomgaarden, Elenbaa, Azrout, Spanje and Vreese2013; Semetko & Valkenburg, Reference Semetko and Valkenburg2000; de Vreese, Reference De Vreese2003), which suggests that media logic does play a role.

According to media logic, news coverage of election results goes beyond the objective electoral performance of political parties and considers the newsworthiness of political competitors and their election results. One crucial shortcut of a party's newsworthiness is party ideology. European party systems are changing as established mainstream parties face increasing electoral pressure from challenger parties on the fringes of the party system (Hobolt & Tilley, Reference Hobolt and Tilley2016; Rooduijn, Reference Rooduijn2015; de Vries & Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020). With more radical positions on economic and socio‐cultural issues, these parties tend to carry a higher news value than established mainstream parties. Communication by and about radical parties also induces conflict because they tend to compete explicitly on an anti‐elite rhetoric and challenge the political mainstream (Rooduijn & Akkerman, Reference Rooduijn and Akkerman2017). Radical parties also tend to be more Eurosceptic (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002) and thus transport negative images of the EU. Electoral victories of such parties in EP elections hence lead to a higher share of political representatives that are sceptical of, or even openly opposed to, the EU as a political system.

We expect journalists to focus more on the electoral performances of radical parties than on those of more moderate mainstream competitors. All else being equal, parties with more radical policy platforms are more likely to be (a) selected for inclusion in news coverage and (b) represented as election winners compared to mainstream parties. The flipside of this argument is that moderate parties are less often considered worth reporting in the first place compared to radical parties. However, if they are included in news coverage, they are more likely to be portrayed as election losers than radical parties because we consider the implosion of the political centre as more negative than electoral defeat at the fringes of the political spectrum.

To test these arguments, we need to specify the policy space in which parties operate. A myriad of research (e.g., Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002; Kriesi et al., Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Marks et al., Reference Marks2006) suggests a two‐dimensional policy space in European politics with a socio‐economic dimension and a socio‐cultural issue dimension. The former dimension separates parties advocating social equality from those supporting economic liberalism (‘old politics’). The socio‐cultural dimension deals with ‘new politics’ issues such as immigration, lifestyle and the environment. The two poles on this dimension separate green, alternative and libertarian (GAL) parties from traditional, authoritarian and nationalist (TAN) ones.

We have no ex ante expectation which type of extremism is more relevant for our argument. Therefore, we include both dimensions in the empirical analysis. Doing so also accounts for the fact that positions on both dimensions are correlated, although the strength and direction of this relationship differs across countries (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012). Hence, we expect:

Hypothesis 4 (Media partisan bias: socio‐economic issues)

H4a (selection): Parties with more radical positions on socio‐economic issues are more likely to be selected for post‐election news coverage.

H4b (representation): Parties with more radical positions on socio‐economic issues are more likely to be portrayed as winners in post‐election news coverage.

Hypothesis 5 (Media partisan bias: socio‐cultural issues)

H5a (selection): Parties with more radical positions on socio‐cultural issues are more likely to be selected for post‐election news coverage.

H5b (representation): Parties with more radical positions on socio‐cultural issues are more likely to be portrayed as winners in post‐election news coverage.

Data and methodsFootnote 7

Sample

We study media coverage of election results from 16 EU member states.Footnote 8 The sample is representative regarding length of EU membership as an indicator of socialization with EP elections (including founding members as well as the most recent member Croatia), geographical location (spanning from Ireland to Slovakia as well as from Sweden to Italy) and number of elected representatives to the European Parliament, including delegations from small (e.g., Austria, Denmark) and large countries (e.g., France, Germany, Poland, Spain). In each country, we selected four newspapers for the content analysis. The newspaper selection was guided by the media sample of the 2009 European Election Study (Schuck et al., Reference Schuck, Xezonakis, Banducci and Vreese2010) and comprised centre‐left and centre‐right broadsheets, financial or business newspapers and the popular press (see Appendix A). We acknowledge that there are other media, but newspapers are a reliable source of information for comparative academic research in Europe (e.g., Belluati, Reference Belluati2016; Gattermann, Reference Gattermann2018; Larsen & Fazekas, Reference Larsen and Fazekas2020; Magin, Reference Magin2015; Vliegenthart et al., Reference Vliegenthart, Boomgaarden, Boumans, Brants and Voltmer2011). While they are not representative of the whole media landscape within and across European countries, particularly quality newspapers are considered influential in shaping the news agenda of other media outlets (e.g., Harder et al., Reference Harder, Sevenans and Van Aelst2017; Vliegenthart & Walgrave, Reference Vliegenthart and Walgrave2008).

We are interested in the post‐election coverage of election results. Thus, our core focus lies on the three days after the final election day on 26 May 2019 (i.e., 27–29 May). We obtained hard or digital copies of all newspapersFootnote 9, but a handful of editions were not available to us (see online Appendix A for further information). We considered all articles published on the front page and those in the following sections: domestic political news, foreign politics/internal affairs, editorials and comments (by own newspaper staff; letters to the editor or comments written by externals were disregarded), and any special report section concerning the EU election. The article selection criteria were as follows: to be considered, the headline, sub‐headline, lead or first paragraph of an article had to clearly refer to the EP election, candidates or parties or an article featured charts or tables on polls and election results. Articles dealing with national or local elections were discarded, as well as those that only mentioned the EP election in passing in the remainder of the article. Our original sample comprises 1,955 articles (see Appendix A).

For our analyses, we start from the population of national parties that competed in the 2019 EP election. The Parlgov database includes 290 parties and electoral alliances for this election (Döring & Manow, Reference Döring and Manow2019). We exclude independent candidates and double counts for electoral alliances (when both the alliance and the constituent parties are included in the Parlgov data). Due to missing data on party ideology for minor parties, especially those without seats in the EP, the number of cases for the empirical analysis drops to 215. To test the hypotheses, we measured the extent to which (selection) and how (representation) each of these parties was reported upon across all newspapers included in our sample, regardless of where these newspapers are published among the 16 countries that we consider.

Coding

The coding is based on the headline, sub‐headline (if available), lead paragraph (font differs from main text; if available), and the first paragraph of the article.Footnote 10 Our codebook comprises several items (see online Appendix B). In this study, we are interested in how the electoral performance of up to five parties and politicians, respectively, are evaluated by journalists. Coders identified these political actors and coded whether they are portrayed as ‘winner’, ‘loser’, ‘ambivalent/mixed’ or whether no such reference was made (‘not relevant’). The 12 coders had high language proficiency (often native speakers) and an interest in European politics. Following coder training, we conducted inter‐coder reliability tests on sub‐samples of eight articles published in The Irish Independent on 27 May and 12 articles of the British Daily Mail on 28 May. Inter‐coder reliability was determined calculating Lotus coefficients for each variable (Fretwurst, Reference Fretwurst2015). This measure allows us to assess inter‐coder agreement on variables that exhibit little variation (e.g., due to the small sample) by adjusting for randomness and to compare the coding of individual coders with both the ‘gold standard’ (i.e., one of the authors) and among each other. It has also been used in other communication research (e.g., Blassnig et al., Reference Blassnig2019; Boukes et al., Reference Boukes, Jones and Vliegenthart2020; Matthes et al., Reference Matthes2015); online Appendix C shows that the scores are satisfactory overall.Footnote 11

News reports referring to national party elites (e.g., Macron, Salvini, Merkel) or EP candidates as winners or losers were subsumed under their respective party (to match these data to party characteristics such as vote changes). Articles referring to parties without mentioning their performance are not included in the analysis. In total, our final dataset comprises 2,836 references to parties as election winners or losers.

Model

We chose a Heckman selection model (Heckman, Reference Heckman1979) to model the selection (stage 1) and representation (stage 2) of the news coverage of election results. The unit of analysis is the political party running in the 2019 EP election. In the first (selection) stage, we use a probit model to estimate the probability that those parties that participated in the 2019 EP election are included in news reports (1) or not (0). In the second stage, we use a linear regression model to explain the representation of all parties mentioned in the news. Specifically, we count the number of articles where a party is mentioned as a winner (w) or a loser (l). As our dependent variable in the second stage, we then use the logged ratio of both counts (ln[(w + 1)/(l + 1)]) to indicate a party's leaning towards a winning and a losing pole.Footnote 12 Parties with a negative score are mentioned primarily as election losers, those with a positive score are often characterized as election winners. Those with an equal number of reports as winners and losers are located at zero. We cluster standard errors by country to account for the interdependence of observations in the same party system.

We also follow the Parlgov party codes to identify election results from previous national and EP elections (Döring & Manow, Reference Döring and Manow2019). Plurality winner (H1) is a dichotomous variable to distinguish the party that won most votes (1) from all other parties in a party system (0). Two variables indicate the (absolute) vote changes (in percentage points) compared to the most recent EP (H2) and national parliamentary elections (H3). We measure ideological extremism using the 2019 Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES; Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2020). We merged CHES and Parlgov data using the Party Facts database (Döring & Regel, Reference Döring and Regel2019) with some minor updates for the 2019 EP election. Party positions on the economic left‐right dimension (H4) and the GAL/TAN dimension (H5) are measured on 0–10 scales.Footnote 13 We include these variables along with their squared term to test whether radical parties are more likely to be characterized as election winners.Footnote 14

We consider several control variables in the analysis. First, we control for party vote share to isolate the effect of the plurality winner from that of party size. Second, we include a dichotomous variable for new parties that have not competed in previous EP or national elections. We do so to distinguish the effect of vote changes (a vote share of zero in previous elections) from that of being a new political competitor. Third, we include a dichotomous variable to distinguish government (1) from opposition parties (0) at the time of the 2019 EP elections. Government parties may ceteris paribus be more newsworthy and thus more likely to receive news coverage than opposition parties. Moreover, government parties (Narud & Valen, Reference Narud, Valen, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008; Rose & Mackie, Reference Rose, Mackie, Daalder and Mair1983), and in particular junior coalition partners (Klüver & Spoon, Reference Klüver and Spoon2020), tend to lose electoral support in second‐order elections while being in office, and may thus be less likely to be identified as election winners. Data on the party composition of the current government is also based on Parlgov (Döring & Manow, Reference Döring and Manow2019). We also use a dummy variable to measure whether a party belongs to the European People's Party's (EPP) group (1) or not (0). The EPP was the plurality winner at the European level, and similar to our expectations in H1a and H1b, its member parties might be more likely to be portrayed as election winners in the post‐election news coverage. Finally, we include a dummy variable in the selection stage to indicate whether a party is from a country included in our country sample (1) or not (0). All else being equal, parties from countries included in our country sample should be more likely to receive news coverage.

Results

Before we proceed to the explanatory analyses, we provide a descriptive overview of our data. Regarding journalistic selection of political parties, about two‐thirds (143 of 215) of all parties are reported upon as either election winners or losers in the post‐election news coverage. The majority (75%) of the 72 parties not mentioned in the newspapers are from countries other than the 16 countries included in our study. Moreover, these parties are substantially smaller (mean vote share: 6.6 per cent) than those mentioned in the news (mean vote share: 14.6 per cent; t(213) = −6.25; p < 0.001).

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the loser‐winner representation for the 143 parties covered in newspapers. It is centred around zero (M = 0.24) and bell‐shaped (SD = 1.98), indicating a balanced reporting about election winners and losers. Parties such as the British Brexit Party (4.8), the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (4.2) and the French Rassemblement National (4.2) are clear examples of election winners, while the Italian Five Star Movement (−4.3), the German Social Democrats (SPD; −3.9) and the French Conservatives (Les Républicains; −3.7) are extreme cases of portrayed election losers. For other parties, the overall assessment is balanced; for example, there is a roughly equal number of articles characterizing the Austrian Freedom Party (−0.1) and Forza Italia (0.3) as election winners or losers, respectively.

Figure 1. The distribution of party representation in the news.

Note: Representation indicates the logged ratio of articles portraying a party as election winner vs. election loser. Based on all parties mentioned in the newspapers (N = 143).

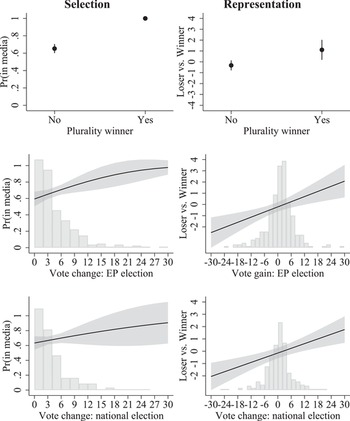

Explaining the variation in the news coverage of election winners and losers, Table 1 shows the results of the Heckman selection model. We plot the predicted values for variables of interest in Figures 2 and 3. In line with Hypothesis 1, the plurality winner is more likely to be selected for inclusion in the post‐election news coverage (H1a). Being the plurality winner in an election increases the probability to receive news coverage by 35 percentage points (see also upper panel in Figure 2). In fact, all of the plurality‐winning parties in the (then) 28 EU member states receive post‐election news coverage. The largest party is also more likely to be seen as an election winner (H1b). The representation on the loser‐winner scale is 1.4 points higher than that of other parties. Note that these effects hold while we control for party vote share. Hence, the plurality winner has an additional effect on news representation independent of a party's sheer size.

Table 1. Explaining post‐election news coverage in the 2019 EP election

Note: Standard errors (clustered by country) in parentheses.

+p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Figure 2. News coverage depending on objective electoral performance.

Note: Predicted values (solid lines) based on the model reported in Table 1. Bar charts denote the distribution of the respective variable on the x‐axis. Remaining covariates are held at their observed values.

Figure 3. News coverage depending on policy positions.

Note: Predicted values (solid lines) based on the model reported in Table 1. Bar charts denote the distribution of the respective variable on the x‐axis. Remaining covariates are held at their observed values.

We also find evidence that vote changes since the last EP election in 2014 affect the news coverage of the performance of political parties (Hypothesis 2). Parties with substantial changes in electoral support are more likely to be selected for news items (H2a): compared to parties with a similar vote share as in the 2014 EP election, those experiencing vote changes of five percentage points (the mean value) in 2019 have a higher chance to be reported upon in newspapers (+10 percentage points). Moreover, parties with vote gains are more likely to be portrayed as election winners than those with vote losses (H2b): increasing a party's vote change from the first to the third quartile (from −2.7 to +5.1 percentage points) increases the representation by about 0.6 on the loser‐winner scale (see Figure 1).

We find similar effects for vote changes compared to the results of the last national general election (Hypothesis 3). The magnitude of the effects for absolute vote changes (H3a) and vote gains (H3b) is similar to that for vote changes compared to the last European election (see also Figure 2). In line with H3b, there is a substantial and statistically significant positive effect of vote gains on the representation of parties as election winners. In contrast, the effect in the selection stage does not comply with conventional levels of statistical significance. We therefore reject H3a.

We also expect a partisan bias in the news coverage of election results: parties with more radical positions on economic (H4) and socio‐cultural issues (H5) should be (a) more likely to be selected for news coverage and (b) represented as election winners. We find evidence for these assumptions based on socio‐cultural issue positions, but not based on economic policy positions (Figure 3). Radical party policy positions on the economy do not significantly increase the probability that a party is selected for inclusion in the post‐election news coverage (see the upper left panel in Figure 3). We thus reject H4a. Parties on the fringes of the economic left‐right dimension are also not more likely to be portrayed as election winners. In fact, fringe parties on the economic left such as the French Communists (Parti communiste français) are somewhat less likely to be portrayed as election winners compared to other parties in the mainstream and the economic right. We therefore also reject H4b.

In contrast, we find strong effects of ideological extremism for the socio‐cultural issue dimension (lower panels in Figure 3). There is a strong selection effect in the coverage of election results in support for H5a: all else being equal, parties’ moderate positions on this issue dimension have a 20 percentage points lower probability to be included in the news coverage of election results than parties on the GAL/TAN extremes. Moreover, and partially in line with H5b, parties on the green, alternative, libertarian (GAL) pole, but not parties on the TAN pole, are much more likely to be represented as election winners than parties with more moderate policy positions. Note that these effects hold while we control for essential elements of party election results (in particular vote share, vote changes and status as the plurality winner). Hence, this ideological bias cannot be explained by the objective electoral success of green or progressive parties in these elections.

One way to illustrate the joint effect of selection and representation in Hypothesis 5 is to use the following example. Imagine 30 parties that only differ in their issue positions on the 0–10 GAL/TAN issue dimension competed in the EP election: 10 parties have progressive issue stances (1), 10 parties have a centrist position (5), and 10 parties hold a conservative issue position (9). Eight out of the 10 progressive parties would be covered in the news and these parties are mostly portrayed as election winners (representation: +0.68). Seven of the conservative parties make the news and their loser‐winner coverage is more negative (representation: −0.36). Only six of the centrist parties receive news coverage and their loser‐winner coverage is also negative (representation: −0.35). Hence, progressive parties have a double advantage compared to the centrist parties: all else being equal, more progressive parties make the news more often and are also more likely to be portrayed as election winners than centrist parties.

Sensitivity analyses

We test the robustness of these results in additional model specifications. First, the effect of party ideology may also result from a party's position towards European integration. Parties with more extreme policy positions are more likely to oppose EU integration (Hooghe, Marks & Wilson, Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002). Hence, more radical party policy positions on the GAL/TAN issue dimension (Hypothesis 5) might also be a proxy opposition to European integration. To test the robustness of our results, we re‐ran the regression model from Table 1 accounting for party policy positions on EU integration. Data for party positions on European integration on a scale from ‘1’ (‘strongly opposed’) to ‘7’ (‘strongly in favour’) comes from the 2019 Chapel Hill expert survey (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2020). Adding this variable does not alter the main conclusions from our analysis (see online Appendix D).

We also test whether our findings are sensitive to the case and sample selection: while only 60% of all parties in our sample have been selected for post‐election news coverage, this share is substantially higher (86%) for the 16 countries that we included in the sample for the media content analysis.Footnote 15 This suggests that the selection stage is primarily important for parties from other EU member states. How does this affect our findings for the representation of the loser‐winner coverage? To answer this question, we study the representation of the loser‐winner coverage only for parties from countries included in our media content analysis sample. As the vast majority of these parties (107 of 125) are mentioned in the news, we ignore the selection stage and estimate a linear regression model (with standard errors clustered by country) and the representation of the news coverage as the dependent variable. The results of this regression model (online Appendix E) are similar to those in the second stage of the Heckman model presented in Table 1 and increase our confidence in the representation hypotheses (in particular H1b, H2b, H3b and H5b) and the null finding for a party's economic policy positions (H4b) from above.

Finally, we test whether the objective electoral performance constrains journalists in using media logic when covering election results (online Appendix F). Framing post‐election coverage depending on party ideology might be harder if parties clearly lost or gained votes compared to previous elections. Vice versa, the media logic might be at play particularly among those parties with a more ambiguous election result (i.e., small vote gains or losses). To test this expectation, we split the sample based on vote changes compared to the last national election and separate parties with clear gains and losses (>3.5 percentage points) from those with a more ambiguous electoral performance (vote change ≤ 3.5 percentage points). Contrary to what one might expect, media logic actually has a stronger effect for parties that are electoral winners or losers. Those parties are per se more newsworthy, and among them newspapers report more often on the election results of more extreme parties. Hence, it is not the case that journalists are constrained by the objective performance. Rather, journalists concentrate their reporting on parties with ‘clear’ election results and an extreme ideology.

Discussion and conclusion

Elections are exciting events for political parties, the media and voters. However, little is known about how results are reported by the media after Election Day. Our article therefore represents an important first step to understand how public perceptions of election winners and losers come about in proportional systems. To this end, the aim of this article was to examine variation in the selection and representation of political parties’ electoral performance in post‐election news coverage. Our study was set up against the backdrop of the 2019 EP election that enabled us to compare newspaper coverage across several countries while holding the electoral context constant.

Our results suggest that both political and media logic guide reporting on election results. Regarding the former, journalists’ reporting on election results ‘mirrors’ political reality (e.g., McQuail, Reference McQuail1992; Tuchman, Reference Tuchman1978). We find, first, that those parties with the largest vote share are both more likely to be selected for news coverage in the aftermath of the elections and more likely to be portrayed as electoral winners compared to other parties. Second, parties with significant changes in electoral support since the previous EP elections are more likely to receive post‐election coverage, while past performances in national elections do not matter for party news selection. However, journalists tend to use both the most recent national election and the previous European election as yardsticks to assess a party's electoral performance in their news representation. These findings suggest that, despite the second‐order nature of EP elections, electoral dynamics within the same (in this case, supranational) political context have consequences for media reporting.

As regards the applicability of media logic, our results suggest that there is a substantial media bias in the reporting: All else being equal, journalists consider parties with radical policy positions on socio‐cultural issues more newsworthy compared to those with moderate positions on the same dimension in the aftermath of elections. Likewise, newspapers are more likely to portray GAL parties as election winners than parties with more moderate policy positions. We do not find the same effects for radicalism on socio‐economic issues. One potential explanation for the different effects on both policy dimensions could be related to the combined party ideology on both socio‐economic and socio‐cultural issues. For example, the Spanish party Vox holds positions on the right both on economic and in socio‐cultural issues (according to the CHES). Yet, its newsworthiness may primarily be linked with its radical views on socio‐cultural issues.

The existence and the magnitude of the media bias in reporting election results has important implications for public perceptions of elections, party systems and political institutions. It creates an uneven playing field in the aftermath of elections: moderate parties will find it more difficult to present themselves as election winners. The media's attention to election victories of radical parties amplifies the public perception of a growing polarization of European party systems. This is problematic as differing perceptions of electoral performances may lead populists across the globe to falsely interpret official election results to their own favour in the future with the intention to undermine the legitimacy of democratic elections.Footnote 16 Similarly, our results highlight the important role of the (mass) media in shaping the public perception of politics in modern democracies. In line with Manin's (Reference Manin1997) notion of ‘audience democracy’, election results do not speak for themselves but rather are being interpreted in public debates (see also Michailidou & Trenz, Reference Michailidou and Trenz2013, for the EU). It is therefore crucial that future research explicitly tests how post‐election media coverage affects citizens’ perceptions of election results (see Plescia, Reference Plescia2019; Plescia & Eberl, Reference Plescia and Eberl2021; Stiers et al., Reference Stiers, Daoust and Blais2018).

Despite the study's implications, there are also several limitations and potential avenues for future research. First, it remains to be seen whether our findings also hold for post‐election news coverage of national parliamentary elections. Despite recent attempts to indirectly elect the Commission President in EP elections, electoral competition and coalition formation in the EU is different from that in parliamentary systems of EU member states. For example, plurality winners in parliamentary elections at the national level might have an even bigger role in post‐election media coverage because of their importance in the government formation process (Bäck & Dumont, Reference Bäck and Dumont2008; Döring & Hellström, Reference Döring and Hellström2013). Likewise, small parties (that gained votes) may still be able to enter government at the national level, whereas EP election results of these parties have no direct consequence for Commission portfolios at the EU level.

We also have to bear in mind that media do not necessarily report election results accurately, especially if these are still preliminary, that is, right after Election Day. Research, for example, shows that news reports are of low quality in Dutch poll coverage when reporting on differences between parties, among other things (Louwerse & van Dijk, Reference Louwerse and Dijk2021). Likewise, poll coverage in Denmark tends to focus on changes at the expense of stability (Larsen & Fazekas, Reference Larsen and Fazekas2020). These considerations are important because our sample is selected on the dependent variable: that is the media may also choose not to report about certain parties. Our results from the Heckman model indeed show that vote share is an important selection criterion for journalists to report about parties in the first stage; that is, the higher its vote share, the more likely that the media include a party in their post‐election coverage. Thus, smaller parties received less media attention. Moreover, and inspired by these pioneering studies (Larsen & Fazekas, Reference Larsen and Fazekas2020; Louwerse & van Dijk, Reference Louwerse and Dijk2021), we recommend that future research considers pre‐election news coverage of polls in its ambition to explain variation in post‐election news coverage. While we focused on previous elections as a reference point for journalists to select and represent parties as winners or losers, comparisons to more recent polls may yield another reasonable yardstick for the evaluation of political parties’ performances. Ideally, studies on the dynamics of media reporting on (expected) electoral performances should be paired with panel surveys to study the long‐ and short‐term media effects on citizens’ attitudes.

Another limitation of our study is that we were unable to control for partisan bias among newspapers. Likewise, there is a large amount of variation of media systems and press cultures across Europe (e.g., Brüggemann et al., Reference Brüggemann2014; Hallin & Mancini, Reference Hallin and Mancini2004); and not all media systems are characterized by a strong popular press and/or an influential business newspaper. We therefore recommend that future research expands the sample to include additional media outlets with diverging funding models (private vs. public), commercial incentives (tabloid vs. quality) and political orientations to study variation across different types of media in the news coverage of election results within a certain country context. This would also allow drawing comparisons at the system level. Here, the differences between news representations of winners and losers may be more pronounced in countries with high levels of political parallelism among the press (see Lelkes, Reference Lelkes2016). In sum, our study provides an important and comprehensive first account of post‐election news coverage and opens up a considerable agenda for future research on its consequences for democratic societies.

Acknowledgements

We thank Nikolina Blažanović, Barbara Erling, Laura Galante, Robin Groß, Jitka Kloudová, Daniel Komáromy, João Palhau, David Ragger, Cady Rasmussen, Katharina Storms, Lisa Zehnter, and Anouk Zwaan for excellent research assistance. We are also grateful to Andrea Ceron, Jonas Lefevere, Lukas Stötzer, Isabella Rebasso, and participants at the 2020 ECPR General Conference, the 2020 Political Behaviour Workshop at HU Berlin, and the Annual ICA Conference 2021 for valuable feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supplementary information

Supplementary information

Supplementary information

Table A1. Case selection

Table A2. Missing newspaper editions

Table C1. Intercoder reliability test results (Krippendorff's alpha and Fretwurst's Lotus)

Table D.1: Explaining post‐election news coverage in the 2019 EP election (incl. EU integration)

Figure D.1: News coverage depending on objective electoral performance

Figure D.2: News coverage depending on policy positions

Table E.1: Explaining post‐election news coverage in the 2019 EP election (based on 16 countries)

Figure E.1: News coverage depending on objective electoral performance

Figure E.2: News coverage depending on policy positions

Table F.1: Explaining post‐election news coverage: clear vs. ambiguous objective electoral performance

Figure F.1: News coverage depending on policy positions: Ambiguous electoral performance

Figure F.2: News coverage depending on policy positions: Clear election winners & losers

Figure G.1: The interdependence of political and media logic in an additive model