1. Introduction

In a surprising turn of events, fossil fuel companies and climate justice activists now agree on the basic facts of global warming: burning fossil fuels causes climate change, and humanity should make a concerted effort towards cleaner energy production. Despite previously promoting climate denial,Footnote 3 major fossil fuel companies now largely accept the scientific consensus in recent legal claims. Opinions diverge, however, on corporate responsibility to address the problem. While defendants acknowledge that their activities have contributed to global warming and recognize themselves as key players in the global energy transition, they emphasize that climate change is a multi-causal issue, involving a wide range of societal and economic factors.Footnote 4 In the courtroom, fossil fuel companies strategically leverage this complexity to challenge attempts to hold them legally responsible. Climate science is a key point of contention: defendants acknowledge its validity for understanding climate change and developing political responses, but contest its use in attributing liability. They use climate science to deflect responsibility away from corporations and attempt to invalidate evidence that points to liability on the part of fossil fuel companies.

Given the political inertia on climate change mitigation, a growing wave of climate litigation has been filed against governments and corporations demanding climate action.Footnote 5 Scientific evidence is critical for legitimizing these claims within the legal framework, especially in terms of establishing a causal link with defendants.Footnote 6 The science is evolving rapidly: new studies and research frameworks make it easier to link specific emitters with specific impacts, increasing the prospects of successful litigation.Footnote 7 Based on recent scientific advances, lawsuits have been filed against fossil fuel companies in various jurisdictions.Footnote 8 Normative discussions are ongoing in academic and legal contexts about whether climate science holds up to legal evidentiary standards.Footnote 9 Attribution science, which links specific impacts to anthropogenic climate change, is key: the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) recognized in its Sixth Assessment Report that recent advances in attribution science ‘provide the basis for climate litigation’ to hold both countries and companies accountable for climate change impacts.Footnote 10 These discussions have high stakes: if courts recognize attribution science as legitimate evidence for linking major emitters to climate change impacts, companies could face an overwhelming wave of lawsuits over climate damage.Footnote 11

Socio-legal research has shown how activist plaintiffs often use legal mobilization as a site of knowledge production. The legal process allows them to make and validate factual claims about broader social problems and who has the responsibility to address them. Past research has analyzed how plaintiffs’ arguments and judicial evaluation of evidence are linked to broader normative concerns.Footnote 12 However, few authors have systematically interrogated how defendants respond, as discussed in the following section. Academic literature on climate litigation has mostly examined legal arguments from the perspective of existing or potential plaintiffs, such as childrenFootnote 13 and victims of loss and damage,Footnote 14 seeking to hold corporations or governments responsible. Discussions about evidence have also focused on plaintiffs – for example, on how attribution science could be applied most effectively to establish legal liability for extreme weather events.Footnote 15 Furthermore, socio-legal research has analyzed the narratives promoted by climate litigation plaintiffs.Footnote 16 However, little attention has been paid to the arguments of corporate emitters when they are brought to court over climate change. Gaining insight into these perspectives is key for capturing the dynamics of legal mobilization and understanding how powerful defendants, such as governments and corporations, may address the wider social and political issues underlying strategic litigation.

The present article addresses this gap by offering the first detailed examination of the legal responses of corporate emitters to climate litigation, focusing on their arguments about science and evidence. I build on socio-legal work on legal mobilization and evidence as well as theoretical discussions in science and technology studies (STS) about science and legal knowledge as conceptual lenses to study the dynamics of legal argumentation. Focusing on how they engage with scientific evidence, I develop a comparative framework for analyzing defendants’ counter-arguments in the context of legal mobilization. I identify three strategies: the first is counter-narrative, in which defendants present a competing interpretation of the facts and evidence – for example, fossil fuel defendants use climate research to argue that global warming is a broader social issue that goes beyond the responsibility of individual companies. The second strategy is to challenge the substantive quality of evidence, in which defendants argue that plaintiffs’ evidence is not sufficiently rigorous. Employing this approach, fossil fuel defendants have stated that climate science does not hold up as legal evidence because of underlying uncertainties. The third strategy is to challenge the integrity of evidence, with defendants arguing that factual claims do not hold up to normative standards of knowledge production. Following this line, corporate emitters have claimed that research put forward as key evidence in climate trials is legally inadmissible as the authors are biased against fossil fuel companies.

Fossil fuel companies will play a key role in shaping the world’s future climate. This article examines how they engage with climate science to advance claims regarding their responsibility for addressing global warming. My comparative framework highlights overlapping dynamics and strategies between cases, showing where the lines of disputes are, and the solutions that companies are likely to propose (Sections 4 and 5). I begin with an overview of theoretical perspectives on legal and scientific knowledge in the context of strategic litigation (Section 2). After explaining my methodological framework (Section 3), I present the key themes emerging from my case studies (Section 4). Based on a critical analysis of these empirical findings, I end with a discussion of the broader ramifications (Section 5).

2. Legal Mobilization and Knowledge Production: Defendants’ Perspectives

Around the world, social movements are using legal strategies to advocate for change on issues such as climate change, racism, and animal rights, among many others. In the socio-legal literature, such engagement is studied within the framework of ‘legal mobilization’.Footnote 17 Litigators often draw on scientific and other forms of knowledge to justify and evidence their claims, whether in the context of environmental concerns,Footnote 18 racialized policing practices,Footnote 19 or abortion rights.Footnote 20 This literature has focused largely on the strategies of activist plaintiffs, as discussed in Section 2.1. It provides a useful lens for studying how parties’ legal strategies are linked to their broader social concerns. The present article contributes an analytical framework to those discussions for studying how powerful defendants respond to arguments about science and evidence in the context of legal mobilization. I begin with an overview of how the production of legal knowledge has been discussed in the legal mobilization literature, particularly around climate litigation (Section 2.1). I then draw on perspectives from STS to explore how legal and scientific knowledge intersect in climate litigation, and develop an analytical framework for understanding defendants’ evidentiary strategies (Section 2.2).

2.1. Climate Litigation and Legal Mobilization

Socio-legal scholars have examined how plaintiffs’ legal knowledge claims emerge alongside broader activist concerns, particularly in the context of legal mobilization.Footnote 21 Research has traced how plaintiffs strategically produce and present evidence that contributes to activist narratives. Reviewing academic discussions about climate litigation from a socio-legal perspective, Fisher finds that litigation can legitimize wider social concerns about climate change.Footnote 22 Once climate change is framed as a legal fact, it appears more ‘real’ in the public eye. Many cases have drawn significant public and media attention, turning courtrooms into sites of knowledge production where activists draw on scientific research to make social and political arguments about climate justice.

In a comparative study of claims against the Dutch, Norwegian, and Irish governments over climate policy, Paiement examines how the cases are embedded in wider transnational concerns.Footnote 23 He finds that they employ a common narrative about the clarity of science and urgency of government action. Analyzing these lawsuits within their broader social context highlights how factual claims in court are co-produced together with political claims about who should take responsibility for climate change. The article also provides a brief overview of defendants’ arguments that their emissions reduction plans are sufficient. Similarly to Paiement, Vanhala traces how environmental activists drew on scientific research to support the legal designation of the polar bear as ‘endangered’.Footnote 24 This opened new legal avenues to advocate for climate action aimed at protecting polar bear habitats.

These studies focus primarily on the legal arguments of activists, offering only tangential insights into corporate or government perspectives. Recent legal research provides some insights into defendants’ perspectives in climate litigation and related fields. According to a rare study of the approaches of businesses to multinational human rights litigation,Footnote 25 defendants see claims about human rights abuses not merely as legal disputes, but as broader strategic and financial challenges. In their legal strategies, defendants must balance legal goals such as avoiding liability with other business interests, including protecting reputation, and maximizing shareholder value.

A series of country reports on corporate climate litigation from the British Institute of International and Comparative Law offers some insights into defendants’ strategies. In German cases, companies challenge the justiciability of climate claims, question that a causal link can be drawn between defendants’ emissions and alleged harm, and argue that they did not engage in unlawful acts as they had lawful licences to operate.Footnote 26 The Netherlands report outlined arguments from Milieudefensie v. Shell – discussed in further detail below – including that the defendant’s contribution to climate change is minimal, and that its operations provided a public benefit.Footnote 27 The United States (US) report provides a brief overview of fossil fuel companies’ arguments against cases brought by states and cities over climate harm. Defendants delay cases through jurisdictional challenges, argue that their conduct was not unreasonable in terms of legal standards for torts, and find that the types of harm alleged are not sufficiently imminent.Footnote 28 In the United Kingdom (UK) report, Bouwer speculates that there may be some degree of strategic coordination among fossil fuel defendants, much like there are networks of climate litigators on the plaintiffs’ side.Footnote 29 This article contributes to those discussions an in-depth view of defendants’ arguments about scientific evidence in four key cases.

2.2. Science and the Law: STS Perspectives

A key concern for socio-legal scholars is how evidence is used to inform legal arguments.Footnote 30 When legal parties submit evidence to court, they do not merely present indisputable truths; rather, they draw on various knowledge regimes to construct factual claims strategically. These claims support their normative view about the issues under dispute. Courts evaluate these factual claims in relation to legal standards of proof, and when they decide to accept particular claims, these become inscribed as legal facts in rulings and verdicts.

Scientific knowledge often plays a significant role as evidence in legal trials. The discipline of STS provides helpful perspectives for analyzing how science and law interact. This has been recognized by socio-legal scholars drawing on theories and concepts from STS;Footnote 31 the work of Bruno Latour and Sheila Jasanoff is insightful in this regard. Latour argues that judicial process, like science, is a regime of truth production: its institutional aim is to discern justified claims from false assertions. Judges require facts to make legitimate rulings. In this framework, individual facts are tools that contribute to the legal system’s overarching goal of producing justice.Footnote 32 In a similar vein, Jasanoff argues that for both science and law, the perceived absence of truth threatens their institutional legitimacy.Footnote 33 Scientific inquiry is usually open-ended – scientific facts are potentially subject to future revision. By contrast, legal proceedings must establish facts within a normative framework in order to reach a verdict.Footnote 34 Judges seek to set the facts straight so that they may conclude the case.Footnote 35 Judges and juries determine what becomes legal fact and which arguments fail to meet the threshold. The typical standard in civil claims, such as the climate cases under study here, is the ‘balance of probabilities’: something must be more likely than not. The standard of evidence is higher in criminal cases, which often require that something must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt.

Scientific knowledge enters the courtroom not as bare facts or truth, but as evidence.Footnote 36 Lawyers must present scientific knowledge in a format that fits the epistemological standards of law.Footnote 37 Courts rely on scientific evidence to establish causation, iteratively interpreting it through legal reasoning.Footnote 38 Since the Industrial Revolution, the belief has grown among legal scholars and practitioners that scientific evidence can reliably inform legal disputes.Footnote 39 Nevertheless, science and law often involve different standards of proof: while science strives to produce universally valid knowledge, law produces knowledge that is relevant within the confines of a particular legal case and jurisdiction. Often, legal processes involve different conceptions of facticity and truth from those required for scientific knowledge. What counts as a fact in a court of law may not count as a fact for science, and vice versa.Footnote 40 Scientific evidence can help to define the parameters of the issue and guide judicial intervention. While legal provisions set parameters for truth-finding in the courtroom, this process is often informed by scientific experts who are called as witnesses.

How does the judicial construction of knowledge play out in legal disputes about climate change? Zhu and Fan identify three common factual questions in climate litigation:

(1) is climate change anthropogenic and related to [greenhouse gas (GHG)] emissions, (2) is global climate change specifically responsible for the alleged adverse local impacts to a particular group of individuals and (3) can the proposed measures make any difference?Footnote 41

While the first question is largely undisputed in the cases studied in this article, defendants’ arguments revolve around the latter two questions, as discussed below. Addressing these questions requires legal practitioners and judges to engage with a vast and rapidly growing field of scientific research. Bringing evidence into court can be challenging as science and law often involve different conceptual languages. For example, scientists and lawyers may both speak about uncertainty, but understand the term in different ways.Footnote 42 Challenges of understanding between science and law may account for the fact that climate lawsuits often do not incorporate the latest scientific research.Footnote 43 While existing research has largely studied these dynamics from the perspective of plaintiffs and courts, a focus on defendants’ arguments about scientific evidence provides a broader and more holistic analysis of the dynamics of legal mobilization. To systematically analyze defendants’ strategies, I develop a comparative framework to identify and evaluate their arguments.

3. Data and Methods

Based on an exploratory study of four emblematic climate change lawsuits involving fossil fuel companies, I examine defendants’ strategies from a qualitative perspective. The number of strategic climate change lawsuits against major emitters has increased in recent years, but many cases have faced procedural delays. As a result, there have been few substantial discussions of evidentiary issues. Four case studies were selected based on the following criteria: (i) broader strategic cases aimed at setting a precedent, (ii) substantial discussions of climate science, and (iii) availability of defendants’ written or oral arguments relating to scientific evidence. Based on these criteria, I selected the following cases.

3.1. Saúl Ananías Luciano Lliuya v. RWE AG (Luciano Lliuya)

Filed in 2015 by Peruvian farmer and mountain guide Saúl Luciano Lliuya against the utility RWE, one of Europe’s largest GHG emitters, this claim concerned the company’s alleged contribution to glacial retreat and flood risk affecting the plaintiff’s house in the Peruvian Andes.Footnote 44 It sought a declaratory judgment and damages, arguing that RWE should bear a proportional share of the costs of protective measures in line with its contribution to historical GHG emissions (0.47%, amounting to around US$ 20,000). The claim was based on a property interference provision under German civil law. It aimed to set a precedent for corporate climate accountability and is one of the most well-known climate lawsuits worldwide in terms of media attention. It was initially dismissed in 2016 by the Essen Regional Court before going into a full trial on appeal at the Hamm Upper Regional Court. In 2017, judges found that the case was legally admissible and ruled to enter the evidentiary stage.Footnote 45 The case was dismissed in 2025 as the court found that the plaintiff did not face a sufficiently high risk. However, in a groundbreaking move and legal first, the judgment confirmed that major emitters can be held liable for climate-related harm in principle.Footnote 46 As one of the few corporate climate compensation cases that has gone to trial, there have been extensive discussions of scientific evidence.

3.2. Milieudefensie et al. v. Royal Dutch Shell Plc

Filed by the environmental non-governmental organization (NGO) Milieudefensie alongside other NGOs and citizens,Footnote 47 the claim demanded that Shell reduce its carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by 45% by 2030 relative to 2019, in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement.Footnote 48 This was a tort claim brought under the social duty of care provision of the Dutch Civil Code.Footnote 49 The plaintiffs argued that Shell’s climate policy constituted unlawful endangerment by failing to align with the Paris Agreement goal to limit global warming to 1.5°C. They further invoked human rights provisions under Articles 2 (right to life) and 8 (right to private and family life) of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR),Footnote 50 interpreted in Dutch case law to apply horizontally to private entities.Footnote 51 The claimants argued that Shell’s actions violated its duty of care to prevent dangerous climate change, as recognized in Dutch jurisprudence. This case produced a groundbreaking ruling when The Hague District Court found in favour of the plaintiffs in 2021.Footnote 52 This ruling constituted one of the first significant precedents in corporate climate litigation, and the trial involved detailed disputes about scientific evidence. The ruling against Shell was overturned by The Hague Court of Appeal in 2024. While the court concluded that Shell did have a duty of care to reduce its emissions in line with Paris Agreement targets, it found a lack of scientific consensus to determine the precise emissions reduction pathway.Footnote 53

3.3. The People of the State of California v. BP Plc (California)

The cities of Oakland and San Francisco in California (US) alleged that five major oil companies (BP, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, Exxon Mobil, Royal Dutch Shell) were liable for the costs of abating a climate change nuisance affecting the cities.Footnote 54 The cases were filed on behalf of ‘the People of the State of California’ and have been heard together in court. The suits, which were virtually identical, were brought under state common law provisions about public nuisance, private nuisance, and failure to warn. They demanded that companies abate the nuisance by funding climate adaptation measures. The claims argued that fossil fuel defendants engaged in a decades-long deception campaign that facilitated a business model which perpetuated global warming. The cases began in 2017 alongside claims by other US cities, municipalities, and states.Footnote 55 After procedural delays over whether the cases should be heard in federal court, the plaintiffs won the right to hear them in state court through a US Supreme Court ruling in 2022 pending federal appeals.Footnote 56 The cases are still pending. If successful, the cases could set a significant precedent that could affect similar ongoing lawsuits in other US states. While the cases have not yet gone to trial (at the time of writing in 2025), the presiding judge organized a climate science tutorial in court at an early stage in which the parties provided detailed comments on the evidence.

3.4. City & County of Honolulu v. Sunoco LP (Honolulu)

Filed in 2020 against 13 fossil fuel defendants (Aloha Petroleum, BHP, BP, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, Energy Transfer Operating, ExxonMobil, Marathon Petroleum Corporation, Mobil, Phillips 66, Royal Dutch Shell, Sunoco, and Texaco), this claim applied legal provisions relating to public nuisance, private nuisance, failure to warn, and trespass.Footnote 57 It alleged that the defendants knowingly contributed to climate change while misleading the public. It claimed abatement costs to cover climate change adaptation measures, as well as punitive damages. It was remanded to state court in 2022 by the US Supreme Court and is currently pending. Like California, this case could set a groundbreaking precedent. At the time of writing in 2025, legal arguments have been mostly procedural but parties have made filings related specifically to evidence, which are analyzed in this article.Footnote 58

In total, eight documents from the four cases were studied. These include defences submitted as legal briefs to court responding to plaintiffs’ arguments. Such documents were available for Luciano Lliuya, Milieudefensie v. Shell, and Honolulu, and were submitted by RWE, Shell, and Chevron, respectively. I cite remarks from Chevron’s counsel in a hearing for California, drawn from the official court transcript. Finally, I quote comments from RWE’s attorney in a court hearing for Luciano Lliuya, in which I conducted ethnographic fieldwork. The quotation is drawn from my fieldnotes. The documents from Milieudefensie v. Shell are unofficial English translations of Royal Dutch Shell’s Statement of Defence (available from the Climate Change Litigation Database of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law SchoolFootnote 59 ) and of the company’s Statement of Appeal (available from ShellFootnote 60 ). The documents from California and Honolulu can be accessed through the Public Access to Court Electronic Records service.Footnote 61 The defendant’s legal briefs from Luciano Lliuya are not publicly available but were provided to me by the plaintiff for research purposes.

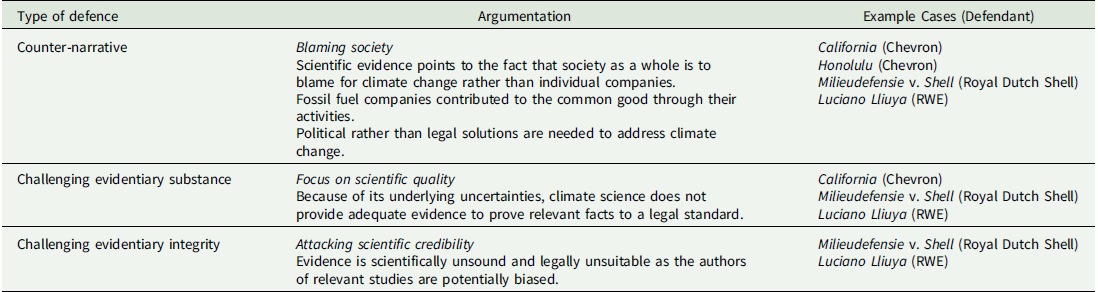

I conducted a systematic textual analysis to evaluate the defendants’ climate-related factual claims, discussions about climate science, and related legal arguments. Individual claims and arguments were logged and manually coded by subject. After conducting the case studies, I did a comparative qualitative evaluation of the arguments. This led to the identification of three broad themes of argumentation across the case studies: (i) counter-narrative, (ii) challenging evidentiary substance, and (iii) challenging evidentiary integrity (see Table 1). These approaches are not mutually exclusive; in most of the cases studied, the defendants applied a combination of these strategies. Arguments are likely to overlap between cases as they often involve the same companies. In the California and Honolulu cases, the defendant Chevron is represented by the same attorney and law firm. This overlap occurs even though the cases differ significantly in their aims, as detailed above. This typology may be useful for understanding how evidentiary discussions could play out in future climate change lawsuits and other types of strategic litigation. Legal mobilization covers a broad range of issues and, accordingly, defendants’ arguments are wide-ranging. This typology offers a starting point for systematically assessing parallels between defendants’ arguments about scientific evidence across individual claims. It is a tool for examining how defendants respond to legal arguments and evidence presented by plaintiffs. This does not cover defendants’ efforts to produce and present new evidence, an issue which merits further research. While the typology identifies key themes of argumentation, this is not exhaustive. Future research may identify additional themes in other cases and contexts.

Table 1. Typology of Defendants’ Evidentiary Strategies in Climate Litigation

4. Corporate Responses to Climate Litigation: A Typology of Defences

4.1. Counter-narrative: Blaming Society

Fossil fuel companies argue that scientific evidence linking them to climate impacts is irrelevant because they act in the public interest. Moreover, they frame climate change as a broader issue extending beyond corporate responsibility. Defendants contend that fossil fuel consumption is driven by demand, and energy companies provide a vital public service. From this perspective, climate change is caused by wider social and economic forces; it must be addressed through action at the political level rather than individual fossil fuel companies being held legally liable. The evidence, according to this argument, points to the responsibility of society rather than individual companies.

Lawyers for both Chevron in California Footnote 62 and ShellFootnote 63 in Milieudefensie v. Shell cite the same passage from the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report: ‘Anthropogenic GHG emissions are mainly driven by population size, economic activity, lifestyle, energy use, land use patterns, technology and climate policy’.Footnote 64

In a hearing for the California case, Chevron’s lawyer argued that ‘the IPCC does not say it’s the extraction and production of oil that is driving these emissions. It’s the energy use. It’s economic activity that creates demand for energy’.Footnote 65 Similarly, Shell’s lawyers argued that ‘demand from society for different sources of energy drives the global energy market, not the supply by Shell or any other energy company’.Footnote 66 In the Honolulu case, Chevron’s lawyers wrote it was misguided to blame ‘a handful of energy companies for a widely discussed phenomenon that is inherent to modern industrial society and the economic foundations of modern life’.Footnote 67 Supporting this, lawyers pointed out that the US and other countries had promoted the use of fossil fuels despite knowing about adverse impacts.Footnote 68 As such, socio-economic development is to blame for GHG emissions and climate change, rather than individual companies responding to those forces.

Furthermore, defendants have argued that they contributed to the common good through their activities. According to Shell’s lawyers, the company serves ‘fundamental interests’ through its fossil fuel activities, which help ‘to satisfy basic human needs’.Footnote 69 Energy, including from fossil fuels, is needed to achieve the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs),Footnote 70 and fossil fuels cannot be replaced by renewable sources such as wind and solar to meet global energy demand.Footnote 71 At a hearing for Luciano Lliuya in 2017, RWE’s lawyer told the court that the company’s emissions ‘have been produced for the common good to ensure a stable energy supply for the population’.Footnote 72 If companies were operating in the public interest, the reasoning goes, they should not be held legally liable for contributing to global warming.

Arguing that lawsuits against individual emitters are unsuitable for addressing the immense social challenges posed by climate change, defendants concur that solutions must be found through a common international effort directed by policymakers. According to Chevron’s lawyer in the California v. BP hearing, ‘climate change is a global issue that requires global engagement and global action’.Footnote 73 Chevron offered a similar defence in the Honolulu case: ‘Global action by governments, market participants, and consumers around the world is necessary to address these important issues and develop meaningful and workable solutions’.Footnote 74 According to Shell, individual companies are not equipped to lead the way. Rather, it is ‘the responsibility of the government to drive the energy transition and achieve the climate goals, by creating policy and regulatory frameworks within which the various actors – industry, governments and individuals – can act’.Footnote 75 In its appeal, Shell ‘calls for a just and orderly transition – one that balances social, environmental, and economic considerations’ to help to achieve the objectives of the Paris Agreement.Footnote 76 According to Shell, this careful balancing act must be led by governments, which courts should not disrupt by imposing ‘absolute and inflexible targets on individual actors’.Footnote 77 Furthermore, Shell argues that imposing an emissions reduction obligation on the company would not be effective as other suppliers would take their place in the market.Footnote 78

As a legal strategy, this defence interprets causal evidence to mean that society as a whole, rather than individual fossil fuel companies, is to blame for climate change. This legal framing of the evidence shifts responsibility away from defendants. The defendants recognize that climate change is a problem and support efforts to implement the energy transition. For example, Shell’s lawyers describe at length the company’s efforts to promote renewable energyFootnote 79 and Chevron’s lawyer contends that fracking helped to reduce US emissions by offsetting coal burning.Footnote 80 Nevertheless, policymakers are responsible for leading this transition, according to defendants. Responsibility for climate change is undeniably complex, involving a vast network of actors, economic structures, and policy decisions. Fossil fuel defendants strategically emphasize this complexity to argue that no individual company can be held legally responsible.

4.2. Challenging Evidentiary Substance: Focus on Scientific Quality

The second argument relates to the quality of science as legal evidence. Defendants in the cases studied do not engage in climate denialism. They recognize the validity of climate science for understanding and addressing global warming. Nevertheless, fossil fuel companies have argued that climate science presented to court by plaintiffs lacks substantive quality, making it unsuitable as legal evidence. By emphasizing uncertainties, they questioned its scientific robustness. They questioned whether the evidence meets legal standards of proof and whether it supports the imposition of legal duties. The evidence is not good enough.

While defendants acknowledge their role in climate change, they argue that this does not establish legal causation; the evidence does not fulfil legal standards. For example, Shell ‘does not deny that its companies partly contributed to aggregate [GHG] emissions’, but lawyers argue that the causal link is ‘indirect at best’.Footnote 81 Asserting that Shell produces a ‘negligible’ amount of emissions, lawyers contend that the company cannot be held legally responsible for contributing to dangerous climate change.Footnote 82

Defendants have argued that numerous factors contribute to climate change, making it difficult to trace scientifically the role of individual contributors. According to Shell’s lawyers, it is too simplistic to say that global warming is caused by humans using fossil fuels.Footnote 83 RWE’s lawyers denounce as reductive the argument that GHGs have caused global climate change via an increase in global temperatures.Footnote 84 Both cite the IPCC AR5,Footnote 85 pointing to numerous natural and anthropogenic processes that shape the climate, such as GHGs and land-use change.

Both companies also appeal to the materiality of CO2 in their defences, arguing that plaintiffs would need to trace the impacts of individual molecules to prove liability. According to Shell, ‘CO2 molecules are indistinguishable from each other and it is not possible to determine who emitted certain CO2 emissions at what point in time’.Footnote 86 In a 2016 legal brief,Footnote 87 RWE’s lawyers argued that it was scientifically and legally impossible to trace emissions to an individual polluter in cases of cumulative causality.Footnote 88 Both cite historical jurisprudence from their respective jurisdictions pointing to the need to trace material impacts in cases of environmental damage. RWE’s lawyers drew a parallel with a set of cases from the 1980s concerning damage to forests caused by sulphur dioxide (SO2) emissions, allegedly originating from nearby industry.Footnote 89 The German Federal Court of Justice ruled that liability could not be established as numerous actors had emitted SO2, which subsequently mixed in the air, making it impossible to determine whose molecules had damaged which specific trees. Citing this decision, RWE’s lawyers argued that it was not possible to establish causal liability in cases of cumulative environmental damage. Much like SO2 molecules from different sources mix in the air, CO2 and other GHG molecules become inextricably linked when they enter the atmosphere. Consequently, they found, there could be no individualized causal relation in legal terms between RWE and the plaintiff, or more specifically between RWE’s emissions and potential climate change impacts in Peru affecting the plaintiff’s property.Footnote 90 RWE and Shell argued that the evidence did not fulfil legal standards of certainty by focusing on the materiality of individual GHG molecules as they ascend into the atmosphere and become lost among countless other molecules from countless other sources.

In the appeal to the ruling in Milieudefensie v. Shell ordering Shell to reduce its emissions by 45% by 2030, the company’s lawyers pointed to a lack of scientific consensus around applying a global reduction target to an individual company. They acknowledged that the figure of 45%, which stems from the IPCC, is based on a scientific consensus around the global level of emissions reduction required to limit warming to 1.5°C. However, they argue that this cannot be translated into a specific target or legal obligation for an individual company under Dutch civil law. The global figure of 45% does not mean that all actors reduce their emissions according to the same pathway; some countries and sectors must do so more quickly than others.Footnote 91

When legal discussions turn to the intricacies of climate models and attribution science, defendants have highlighted underlying uncertainties. In a hearing for the California case, Chevron’s lawyer argued that increasing complexity in climate modelling ‘introduces new sources of possible error’.Footnote 92 Citing the IPCC, he found that some models overestimated the impact of human activity on global temperatures.Footnote 93 Finally, he downplayed the threat of sea level rise to Californian cities by emphasizing that an extreme rise of 10 feet by 2100 was very unlikely to happen according to current studies.Footnote 94 With such uncertainties, the evidentiary validity of climate science stands in question.

As the Luciano Lliuya case has progressed the furthest of the cases under study concerning specific local impacts, evidentiary discussions are the most detailed. The initial claim filed in 2015 cited data from the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report attributing glacial retreat in the Peruvian Andes to anthropogenic climate change. With the science rapidly evolving, new evidence emerged as the case progressed. In 2021, an independent study came out attributing flood risk at Lake Palcacocha in the Peruvian Andes to anthropogenic climate change. It was published by researchers at the Universities of Oxford (UK) and Washington (US) in the leading journal Nature Geoscience.Footnote 95 The glacial lake lies above the plaintiff’s house, and the lawsuit revolves around RWE’s alleged contribution to the increased risk. Relying on climate and glacier modelling, the study examined the relation between global atmospheric warming, local warming at Lake Palcacocha, the retreat of the Palcaraju glacier above the lake, and a potential increase in flood risk. It found that around 95% of the local warming and subsequent glacial retreat was as a result of human influence. The study relied on established methods in the attribution science community but was the first of its kind in that it examined the impact of climate change on flood hazard at an individual glacial lake. It was submitted as evidence by the plaintiff’s legal team in April 2021.Footnote 96

RWE’s lawyers claimed that the study was unsuitable for resolving the evidentiary questions at stake. In a legal brief filed in December 2021, they stated that its methods are not adequate for establishing glacial lake flood risk, that it relies on insufficient data to prove a local temperature increase, and that its glacial modelling is imprecise. They also attacked the authors’ credibility; I examine this in the following section. The lawyers argued that the publication offered ‘no new insights regarding a concrete GLOF [glacial lake outburst flood] risk at the Palcacocha glacial lake’.Footnote 97 According to their analysis, the underlying methods were suitable only for identifying potentially dangerous glacial lakes at a regional level and did not sufficiently account for the parameters of an individual lake. To reach this conclusion, they drew on scientific research commissioned by RWE.Footnote 98

RWE’s lawyers questioned the efficacy of climate models for determining a local temperature increase in the Peruvian Andes. They argued that the model used by Stuart-Smith and co-authorsFootnote 99 operates at much too large a scale to allow for reliable conclusions about temperature variability at the lake. To prove an increase in temperature, they contended that the plaintiff must present local measurement data going back decades. Where such data is unavailable, as in the case at hand, climate scientists typically use gridded temperature observations that assimilate measurements from elsewhere in the region, re-analysis data, and climate models. According to the lawyers, such modelling does not provide suitable evidence. They argued that the authors’ approach has significant underlying uncertainties as a result of insufficient real-world data input and relies on imprecise assumptions.

Based on a selective analysis of existing research and raw temperature data at one location, RWE’s lawyers concluded that there is ‘no stronger warming in higher areas than in lower areas’ in the Andes. While this appears to be carefully formulated in that it draws these conclusions based only on the specific studies under scrutiny, it contributes to a narrative of doubt about whether temperatures in the Peruvian Andes are increasing, despite the fact that this development is widely recognized in the scientific community, most recently in the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report.Footnote 100 While not explicitly rejecting established climate science methodologies as a whole, the lawyers raise doubts about individual studies and datasets to undermine the plaintiff’s evidentiary basis. They avoid positioning themselves as climate science deniers but emphasize uncertainties to claim that existing research does not meet legal standards of evidence.

Similarly, the defendant’s lawyers question the efficacy of a glacier model used by Stuart-Smith and co-authorsFootnote 101 to evaluate how the Palcaraju glacier above Lake Palcacocha has retreated since 1880. Once again, they point to underlying uncertainties and assumptions. The lawyers do not deny that the glacier has retreated – this has been documented in extensive research and historical photography – but argue that the model in question does not accurately represent how the glacier has changed because of discrepancies between modelling results and real-world measurements. They conclude that ‘even if such models may be a relevant instrument for science, they do not fulfil the legal standard for causation and evidence’.Footnote 102 The model provides only ‘a statement of probability that is insufficient for establishing causal proof under civil law’.Footnote 103

Overall, RWE’s lawyers ask legal questions of the science. They argue that the science, in its current state, does not fulfil legal evidentiary standards. Furthermore, they present seemingly contrary findings. Through questioning the validity of specific scientific insights, the lawyers establish a narrative that no adequate evidence is available to prove RWE’s causal contribution to climate change impacts in Peru. Across cases, fossil fuel defendants argue that climate science may be useful for understanding the processes of global warming but is inadequate for establishing legal liability.

4.3. Challenging Evidentiary Integrity: Attacking Scientific Credibility

The first two sets of arguments outlined above offer a solid basis of defence: liability cannot be established because fossil fuel companies were acting in the public interest and the science is too uncertain. When defendants faced compelling scientific evidence that potentially established their liability, they have resorted to a more assertive strategy: questioning the impartiality of potential court experts and the authors of relevant scientific studies, meaning that their expertise should not be admissible. When parties put forward scientific studies as legal evidence, they must usually demonstrate that these are rigorous according to scientific standards. Peer review helps to ensure research integrity and eliminate bias, and journals typically require authors to declare funding sources and potential conflicts of interest. Higher standards apply to court experts who must demonstrate impartiality according to legal standards.

Both the Luciano Lliuya and Milieudefensie v. Shell plaintiffs draw on the Carbon Majors Report that quantified historical emissions and linked them to individual companies.Footnote 104 This report found that Shell and RWE have contributed 2.12% and 0.47% respectively of industrial GHG emissions between 1854 and 2010. Shell’s lawyers questioned the study’s scientific rigour, characterizing it as an ‘outlier publication’.Footnote 105 Going further, they argued that the circumstances of the study’s production suggested a lack of impartiality: it ‘was commissioned by Greenpeace International, an NGO that conducts activist litigation against the oil and gas industry globally, including for attribution-based damages claims relating to climate change’.Footnote 106

In Luciano Lliuya, RWE’s lawyers questioned the impartiality of potential court experts and of scientists who authored studies submitted as evidence. After the lawsuit entered the evidentiary stage in 2017, the court asked both parties to suggest scientists who could act as independent court-appointed experts. The court’s preference was to appoint German-speaking experts. The plaintiff’s lawyers proposed Friederike Otto, a well-known climate scientist who participated in the development of climate change attribution methodologies that are widely recognized and used in the scientific community. RWE’s lawyers argued in responseFootnote 107 that Otto was unsuitable as an independent expert based on an alleged bias against fossil fuel companies that underlies her work. Their legal brief included colour prints of three Twitter posts going years back in which Otto shared news articles about climate litigation. While Otto stated in her posts that the claims were ‘interesting’, the lawyers took this to mean that she ‘expressed support for legal claims in relation to climate change’.

In the same legal brief, the lawyers pointed out that Otto had participated in two events alongside lawyers from ClientEarth, an organization involved in climate litigation, including claims against fossil fuel companies. Consequently, they found that Otto was trying to ‘position her work in connection to potential climate liability claims’ by promoting it to environmental lawyers. Finally, RWE’s lawyers pointed to the fact that Otto and the plaintiff’s lawyer, Roda Verheyen, gave talks as part of the same climate change seminar series in Hamburg (Germany), albeit on different dates and on different topics. Consequently, the defendant’s lawyers expressed their worry that Otto and Verheyen ‘are part of the same interest and contact network’.Footnote 108 The lawyers concluded that based on her public statements expressing interest in climate litigation and her association with so-called ‘activist lawyers’, Otto was potentially biased in favour of the plaintiff and would be unable to examine the evidentiary questions from a neutral point of view if the court appointed her as an expert witness. She could not act as an impartial expert according to the standards of jurisprudence. Instead, they suggested the judges appoint Judith Curry, a climatologist who has publicly questioned the scientific consensus on the anthropogenic contribution to global warming.Footnote 109 Ultimately, the court did not choose any of the people suggested by the lawyers and found its own experts.Footnote 110

When the plaintiff’s lawyers submitted the attribution study by Stuart-Smith and co-authorsFootnote 111 as evidence in 2021, RWE’s lawyers criticized the article in scientific terms, as discussed above. In the same legal brief, they questioned the authors’ impartiality. The judges had found in a ruling that it was an independent piece of research that had a higher evidentiary validity than scientific studies commissioned by one legal party.Footnote 112 When the plaintiff’s lawyers submitted the study to the court, they asserted that they had no involvement in its production.Footnote 113

In their legal brief,Footnote 114 RWE’s lawyers questioned the independence and impartiality of the study’s authors. They alleged, without proof, that the plaintiff’s lawyers were involved in the production of the study,Footnote 115 and argued that the authors aimed to influence the lawsuit in the plaintiff’s favour. The authors had publicly stated their hope that the study would clarify the facts in the ongoing legal process.Footnote 116 In procedural terms, the defendant’s lawyers argued, it was not independent proof; its evidentiary legitimacy was compromised.Footnote 117

In addition, the lawyers alleged that some of the authors have ‘publicly positioned themselves as enemies of CO2 emitters and have been active on the side of climate activists and climate litigators’. They based this accusation on the fact that Rupert Stuart-Smith, the study’s lead author, has expressed that he wishes to bring ‘together science and the law to tackle climate change’. In addition, they stated that he regularly shares articles and opinions on his Twitter account about the responsibility of corporations in relation to climate litigation. Furthermore, they argued that Stuart-Smith is a member of a youth climate group which, they alleged, has organized activities with the activist movement Extinction Rebellion. They also pointed out that another author, Myles Allen, provided support to plaintiffs in a US climate lawsuit against the fossil fuel industry and authored an article in The Guardian newspaper titled ‘Big Oil Must Pay for Climate Change’.Footnote 118 For the lawyers, this was sufficient evidence to argue that the authors’ scientific work is biased against fossil fuel companies such as RWE.

The lawyers further questioned the authors’ scientific integrity by associating them with the plaintiff’s lawyers and scientific advisers. ‘The authors’, they state, ‘are part of a certain circle of people who present at events together, publish together and cite each other in publications.’ They pointed out that the plaintiff’s lawyer, Roda Verheyen, and the author Myles Allen both contributed to an inquiry about climate change by the Philippines Human Rights Commission.Footnote 119 Without providing evidence, they alleged that Stuart-Smith and his colleagues had contact with two scientists who advised the plaintiff’s legal team. Finally, the lawyers pointed to professional links between the study’s authors and Friederike Otto whose impartiality they questioned in an earlier legal brief.

In sum, RWE’s lawyers contended that climate scientists who have expressed concern about the responsibility of corporations for global warming and potentially engaged in public advocacy do not fulfil legal standards of impartiality and should not be admitted as court experts. They applied similarly high expectations of impartiality to the authors of studies submitted as evidence. Following this line of argumentation, peer-reviewed scientific publications should not be admitted by courts as independent evidence in climate litigation if the authors are suspected to have critical opinions about fossil fuel companies. Co-authorship and academic referencing are potential signs of impartiality. Nevertheless, it may be difficult to find a climate scientist who has not expressed concern about the issues underlying their work and has never been associated with or cited a scientist who believes that fossil fuel companies might have a responsibility for addressing climate change.

5. Discussion

Climate science plays a key role in legal claims against fossil fuel companies over their responsibility for global warming. In a significant shift from previous denialist strategies, major fossil fuel companies have largely accepted the scientific consensus on climate change. While no longer engaging in open denial, they have emphasized the uncertainty inherent in climate science in recent claims to hold them legally liable for climate change impacts.Footnote 120 Defendants construct counter-narratives by reinterpreting the evidence to shift blame from individual companies to society as a whole. This strategy is proactive in that it draws attention away from plaintiffs’ narratives and presents an alternative understanding of the facts. Future research could compare the narratives of both corporate and government defendants in climate litigation, and examine how legal arguments relate to their communications, policies, and actions addressing climate change. An area for further investigation is the involvement of plaintiffs and defendants in the production of evidence through commissioning and funding scientific research. Beyond the scope of climate litigation, broader research within the framework of legal mobilization could explore how defendants in other types of case use litigation as a site of knowledge production. It may also be fruitful to compare defendants’ courtroom narratives with their broader public communications.

Challenging substance and integrity are both reactive approaches: they are strategies to discount evidence submitted by plaintiffs. However, they have divergent implications. The substantive challenge implies that evidence may hold up in court if it were stronger. When fossil fuel defendants argue that climate change attribution research cannot be used to establish legal causality because of underlying uncertainties, they leave the door open for evidence to be admitted if scientific methodologies improve and uncertainties are reduced. This strategy postpones liability by awaiting further scientific development and judicial clarity on evidentiary standards. The challenge to scientific integrity involves a more fundamental attack on the epistemological legitimacy of evidence. When defendants argue that courts should not consider certain scientific studies because the authors are not impartial, they imply that any evidence submitted by those researchers – or anyone else with potential bias or indirect links to the plaintiff’s legal team – is inadmissible. It should be noted that challenges to evidentiary substance and integrity can both contribute to defendants’ broader legal counter-narratives, as when fossil fuel companies insisted that there was insufficient evidence linking their emissions to specific climate change impacts. The socio-legal literature would benefit from further research in examining how defendants challenge plaintiffs’ arguments about scientific evidence in other types of legal mobilization. The typology developed in this article can serve as a starting point for future studies of defendants’ perspectives. A more systematic analysis of a wider range of cases would be beneficial to determine how the typology could be refined, and the additional types of argument that could be added.

5.1. Corporate Avoidance of Climate Responsibility

Major polluters walk a fine line. They publicly accept the reality of climate change while questioning the legal admissibility of evidence that points to their potential responsibility. The results of this study contribute to broader research on the engagement of fossil fuel companies with climate change. A study of ExxonMobil’s climate change communications since the 1970s found that the company shifted from explicit scepticism about climate science to acknowledging anthropogenic global warming since the mid-2000s.Footnote 121 However, public communications highlighted scientific uncertainties and promoted a narrative that GHG emissions are caused by public demand for energy rather than the actions of fossil fuel companies, shifting responsibility to consumers. The study cites oral arguments made by Chevron’s counsel in California and points to a dual narrative: fossil fuel companies simultaneously claim that climate science is ambiguous and that the public is well informed about the dangers of anthropogenic global warming.Footnote 122 Shell and RWE employed similar arguments in Milieudefensie v. Shell and Luciano Lliuya.

Public statements made by fossil fuel companies also reflect their defence argument that their activities serve the public good. Lamb and co-authors identify industry arguments that fossil fuels are essential for human well-being and poverty reduction.Footnote 123 Research by Supran and OreskesFootnote 124 on ExxonMobil’s communications identifies a ‘fossil fuel savior’ narrative that portrays fossil fuels as indispensable for meeting global energy demand. This emphasizes the role of fossil fuels in driving economic growth, alleviating energy poverty, and ensuring global prosperity. By highlighting consumer demand for energy, the narrative suggests that responsibility for climate change lies with individual choices and market demand rather than with the corporations that extract and sell fossil fuels. Legal arguments by Shell and RWE reflect this narrative, arguing that their polluting activities serve the common good. Noticeably, Shell’s argumentation was unsuccessful in Milieudefensie v. Shell. Despite finding in favour of the company overall, The Hague Court of Appeal ruled that while fossil fuel use may be driven by demand, Shell still has a responsibility to reduce its supply of fossil fuels.Footnote 125

In all four cases under study, the defendants argue that climate change requires broad political solutions and should not be addressed through litigation against individual polluters. This contrasts the documented efforts of fossil fuel companies to prevent and delay climate policy action. They redirect responsibility away from major polluters, highlight the downsides of climate policies, and push for non-transformational solutions such as carbon capture and storage.Footnote 126 The fossil fuel industry in the US has provided significant funding to US organizations that publicly question the scientific consensus on climate change and lobby against government climate action.Footnote 127 In addition, the industry has funded economic research that overstated the costs of climate policies while downplaying the benefits. This influenced political discussions in the US and ultimately delayed policy implementation.Footnote 128 The argument that political solutions are needed on climate change may be a legally pertinent defence in that it redirects responsibility elsewhere, but it appears to contradict the efforts of fossil fuel companies to counter climate policy. Further research could compare companies’ public statements with their legal arguments in more detail.

5.2. Pivotal Role for Evidentiary Standards

Standards of evidence regulate how courts establish the facts of a case. In climate litigation, as in many other legal disputes, the facts are often complex, and epistemological certainty is rarely absolute. How courts understand scientific evidence in relation to legal standards of proof plays a significant role in shaping the prospects of success for climate litigation. A central issue of dispute is whether underlying uncertainties in climate models make them inadmissible as legal evidence. By stating that climate models do not fulfil relevant legal evidentiary tests, defendants can argue that they cannot be used to establish legal causation.

Climate science does not answer political and legal questions about which impacts should be prioritized and who should take responsibility.Footnote 129 Nevertheless, it can provide evidence that informs courts and policymakers, helping them to address those questions within the normative framework of law. Academic and legal debates are ongoing about whether climate science holds up to judicial evidentiary standards. This is especially pertinent when it comes to questions of causation. Across jurisdictions, courts often apply the ‘but-for test’ to establish causation: if it were not for the defendants’ conduct, a particular type of harm would not have occurred.Footnote 130 In the context of climate change, causation is cumulative: it involves multiple causal parties whose actions collectively result in global climate change, which, in turn, manifests in a multitude of specific local impacts.Footnote 131 Some argue that the ‘but-for test’ should be relaxed to allow for attribution evidence that provides statements of probability about the occurrence of extreme weather events.Footnote 132 Nevertheless, the ‘but-for test’ may be met in terms of the defendants’ contribution: every GHG emission contributes equally to global warming.Footnote 133

In the cases discussed above, fossil fuel defendants highlighted the uncertainties that underlie climate models, undermining their validity for providing causal evidence and establishing liability. There are parallels in Juliana v. United States (2020),Footnote 134 a case brought by youth plaintiffs over the government’s responsibility to address climate change, in which the government’s lawyers attacked the reliability of attribution evidence and argued that confounding factors such as land-use change and economic circumstances could not be disentangled from anthropogenic climate change impacts.Footnote 135 Since attribution science is a relatively new field, courts can draw on few precedents for using it as evidence to establish causation. Cases revolving around damages or compensation – such as Luciano Lliuya, Oakland, and Honolulu – rely most heavily on probabilistic attribution evidence, opening them up to attack over the underlying uncertainties in climate modelling.

A further challenge for courts relates to which science should be accepted as legitimate evidence. Evidentiary standards often prescribe that scientific methods should be generally accepted, meaning there is scientific consensus about their validity.Footnote 136 The nature of such consensus may be disputed in practice. One of the grounds for dismissal in Milieudefensie v. Shell by The Hague Court of Appeal was that scientific opinions differed on the emissions reduction pathway that was required for Shell.Footnote 137 While all experts who provided testimony agreed that Shell should reduce its emissions, even those hired by the company, Shell’s lawyers, successfully argued that there was a lack of scientific consensus as various figures were provided for the level of reduction required to stay in line with the global target of limiting warming to 1.5°C. Different calculations and modelling approaches inevitably produce varying results, even if all results point in the same direction. In future cases, courts may consider that scientific consensus is often manifested in broad trends, rather than precise numbers.

In climate litigation against major corporate emitters, how judges apply evidentiary standards may determine whether key evidence is considered serviceable for proving causal responsibility. Broader comparative research would be helpful in examining how standards of proof affect legal argumentation in different jurisdictions and how judges apply these standards to climate science in different types of case. Comparative work examining how standards of evidence are applied in other types of environmental and tort litigation would also provide useful insights. Such research may highlight where corporate climate litigation has the greatest prospects for success in evidentiary terms. Researchers could also analyze how arguments related to scientific evidence differ between cases concerning corporate responsibility for past emissions like Luciano Lliuya, California and Honolulu, lawsuits like Milieudefensie v. Shell over emitters’ future conduct, and claims against governments over climate policy targets. My research indicates that standards of evidence are particularly important in cases involving complex causal chains and specific local impacts.

If courts recognize existing scientific evidence as legitimate proof for holding major emitters liable, repercussions might also be felt on the stage of international climate politics.Footnote 138 Attribution science is pertinent to political discussions about climate change and responsibility, particularly for negotiations on loss and damage at UN climate negotiations,Footnote 139 and climate litigation may increase momentum for political solutions at this stage.Footnote 140 Knowledge claims about causation and responsibility are highly politicized in a context where governments from the US, the European Union, and other major economies have consistently refused to acknowledge that past emissions might imply financial liability.Footnote 141 Attribution research can support developing countries’ claims for compensation.Footnote 142 Legal validation of causal evidence could provide additional support to vulnerable countries seeking financial redress from those who contributed most to global warming.

5.3. Legal Knowledge Claims Linked to Broader Social Concerns

In legal mobilization claims, as in litigation more broadly, plaintiffs and defendants present factual claims that support their legal narrative. When it comes to climate litigation, legal arguments are often linked to much wider social and political concerns, such as the moral responsibility of major corporate emitters to address global warming. Fossil fuel defendants have questioned the legal admissibility of evidence if the authors of relevant studies expressed opinions that run counter to the companies’ interests. In this interpretation, the potential concern of scientists about climate change and the responsibility of major emitters makes their research epistemologically contaminated. From a scientific standpoint, researchers’ personal opinions and political views do not necessarily mean that the knowledge they produce is biased. Peer review is intended to eliminate bias by judging research based on its academic merits. When corporate defendants argue that climate science publications are biased, they attack the integrity of peer review and the academic knowledge production process which is designed to eliminate bias.

Contemporary court discussions about climate change echo legal disputes against tobacco companies decades earlier. Numerous industry-funded studies denied that smoking causes health risks.Footnote 143 Science may play a similar key role in litigation against fossil fuel companies.Footnote 144 This is already playing out in Luciano Lliuya, with RWE funding research that downplayed the severity of glacial flood risk in the Peruvian Andes.Footnote 145 Such disputes highlight that all knowledge is relational and value-imbued, emerging in line with normative concerns about how the world is – and should be – ordered.Footnote 146 Climate science is often produced in response to policymakers’ demands, public concerns, and researchers’ own worries about global warming.Footnote 147 To argue that this relationality of climate change knowledge makes it biased may lead to the absurd conclusion that all climate science is illegitimate for use within a legal framework. In extremis, it would mean that the entire discipline of climate science is biased, echoing the arguments of climate change denialists.Footnote 148 In a similar vein, one might argue that cancer researchers are biased if they want to stop people from dying from cancer. Instead, it may be more fruitful to avoid the naïve conception that science can – or even should – be entirely uninterested. The production of climate change knowledge is intrinsically intertwined with people’s concerns about the devastating impacts felt around the world. This is equally relevant in a policy context where serviceable knowledge is required to help public authorities in addressing climate change.

Scientific evidence in climate litigation supports broader narratives about how corporations and governments should address global warming. Across jurisdictions, plaintiffs often build on each other in terms of their broader arguments. With their narratives, they seek not only to convince judges but also to influence public understandings of climate change and climate justice.Footnote 149 Similarly, defendants’ narratives are likely to build on each other, particularly those of corporate emitters countering causal liability claims. Recognizing the value-imbued nature of knowledge, cross-jurisdictional comparative research on legal mobilization could examine how broader social concerns shape corporate and government defendants’ argumentation inside and outside the courtroom.

6. Conclusions

Past research has shown how activist plaintiffs use legal mobilization as an opportunity to produce knowledge that supports their normative claims and legal arguments. In this article, I demonstrate how fossil fuel defendants use the judicial process to make strategic legal arguments about the facts in climate litigation. Calling for an increased comparative study of defendants’ perspectives on legal mobilization, I develop an analytical framework for studying their legal arguments regarding science and evidence. Firstly, fossil fuel companies develop counter-narratives, drawing on factual claims to present competing understandings of the underlying issues that absolve them of legal responsibility. They point to the responsibility of society rather than individual companies. Secondly, defendants challenge the substantive quality of evidence, highlighting uncertainties and arguing that evidence presented by plaintiffs is not rigorous enough to fulfil legal standards. Finally, defendants attack the integrity of plaintiffs’ evidence, questioning the scientific objectivity of researchers and arguing that their work fails to meet standards of objectivity and legal admissibility. Future research can apply this typology to other forms of legal mobilization where scientific evidence plays a central role, such as public health or environmental litigation.

The legal arguments of fossil fuel companies reflect a broader strategy to avoid responsibility for addressing climate change. Going forward, how courts apply legal standards of evidence to climate modelling and climate change attribution studies is likely to shape the viability of strategic climate litigation. If courts accept climate science as proof of legal causation linking individual polluters to specific impacts, major emitters could face immense financial liabilities. Corporate defendants tread carefully in recent climate litigation against major emitters: they concede that climate change is a major global problem and that burning fossil fuels plays a significant part but refuse to accept legal responsibility for addressing climate change and its impacts. As the number of climate lawsuits against corporate emitters grows around the world, courts will have to decide whose facts are more factual. The legal evaluation of climate science will continue to play a key role in shaping judicial outcomes and informing climate policy.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Lisa Vanhala, Joana Setzer, Joy Reyes, Nicholas Petkov, Zoe Savitsky and Elena Borisova for their valuable feedback on earlier drafts of this article. I am also grateful to the three anonymous reviewers for TEL for their insightful comments and constructive suggestions.

Funding statement

This work was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council of the United Kingdom (Grant references: ES/W00674X/1, ES/Y003314/1) and the Grantham Institute – Climate Change and the Environment at Imperial College London (UK).

Competing interests

I was a scientific adviser to the plaintiff’s legal team for the climate change lawsuit Luciano Lliuya v. RWE. This work did not compromise my academic integrity as this article does not aim to foster any specific legal arguments, but to examine the broader dynamics of climate litigation.