Emetophobia is a fear of vomiting that is classified as a specific phobia in current diagnostic systems. 1,2 Most people with emetophobia fear that they, themselves, will have to vomit, or fear both vomiting and seeing others vomit. Reference Keyes, Gilpin and Veale3 A minority of about 10–12% of persons with emetophobia exclusively fear seeing others vomit. Reference Meule, Seufert and Kolar4 As a result of these fears, persons with emetophobia show a wide range of both safety behaviours (e.g. checking expiry dates of food, hand-washing, checking own and others’ health status, overcooking food) and avoidance behaviours (e.g. refusing to go to school, avoiding sick or drunk people, avoiding consumption of certain foods or alcohol, avoiding travelling/public transportation Reference Keyes, Gilpin and Veale3 ). There is also a high comorbidity with related conditions such as other anxiety disorders and obsessive–compulsive disorder, Reference Meule, Seufert and Kolar4 which may contribute to or reinforce these behaviours.

Earliest reports about individuals with emetophobia can be traced back to the middle of the 20th century. For example, Allen and Broster described a case of a young woman in 1945 who ‘vomited after eating sardines, at the age of 12, [and] developed an obsessional fear of this recurring’ Reference Allen and Broster5 . Other case reports describing children with a fear of vomiting were published in 1958 and 1961. Reference Sutton, Falstein and Judas6,Reference Blitzer, Rollins and Blackwell7 While authors in the previous century used to describe this condition as either vomit phobia, phobia of vomiting or fear of vomiting, it seems that the term emetophobia was not used in the scientific literature until the 21st century. Reference Lipsitz, Fyer, Paterniti and Klein8 Although cases had already been described more than half a century ago, emetophobia has received little attention in research and is a relatively unknown disorder among the general public. However, it seems that many psychotherapists are familiar with it because they frequently encounter persons with emetophobia in clinical practice. Reference Vandereycken9

Compared with other specific phobias (of which fear of animals is the most common), emetophobia is among the least common. Reference Becker, Rinck, Türke, Kause, Goodwin and Neumer10 However, a recent study by Veale and colleagues now suggests that it may, in fact, be the most common specific phobia that requires treatment. Reference Veale, Beeson and Papageorgiou11 Specifically, the authors analysed the data of more than 1000 UK patients who had received treatment for a specific phobia and found that around 20% presented with emetophobia, which was the most prevalent specific phobia subtype in this sample. Moreover, patients with emetophobia differed from those with other specific phobias in that the former were more likely to be female and to have received in-patient treatment. They also tended to be younger than those with other specific phobias, although this was found only for adults.

Veale and colleagues’ study is a valuable contribution to the literature on emetophobia because there have been, in fact, only a handful of studies that examined possible differences between emetophobia and other specific phobias. Reference Becker, Rinck, Türke, Kause, Goodwin and Neumer10,Reference Davidson, Boyle and Lauchlan12,Reference Meule, Zisler, Metzner, Voderholzer and Kolar13 Importantly, the study suggests that, although emetophobia is a relatively rare condition, the numerous safety and avoidance behaviours seem to impair daily functioning much more than do other specific phobias, which is why it more often requires treatment (and even more intensive in-patient treatment) than other specific phobias.

This concurs well with a recent study that retrospectively analysed the data of 110 persons with specific phobia as primary diagnosis and who had received in-patient treatment at the Schoen Clinic Roseneck (Prien am Chiemsee, Germany) between January 2015 and February 2024. Reference Meule, Zisler, Metzner, Voderholzer and Kolar13 Of these individuals, 70 had emetophobia and 40 had other specific phobia subtypes (e.g. fear of going to school, test anxiety, phagophobia, blood/injection/injury-type phobia). These numbers are interesting in themselves because they suggest that, if persons with a specific phobia receive in-patient treatment (which is a fairly uncommon treatment setting for this condition), those with emetophobia are over-represented in such a sample compared with the overall population of those with specific phobias, in line with the findings by Veale and colleagues. Reference Veale, Beeson and Papageorgiou11 This may be partially explained by the fact that persons with emetophobia often restrict food intake, with many presenting as underweight and, thus, require a more intensive treatment setting. Reference Meule, Zisler, Metzner, Voderholzer and Kolar13,Reference Veale, Costa, Murphy and Ellison14

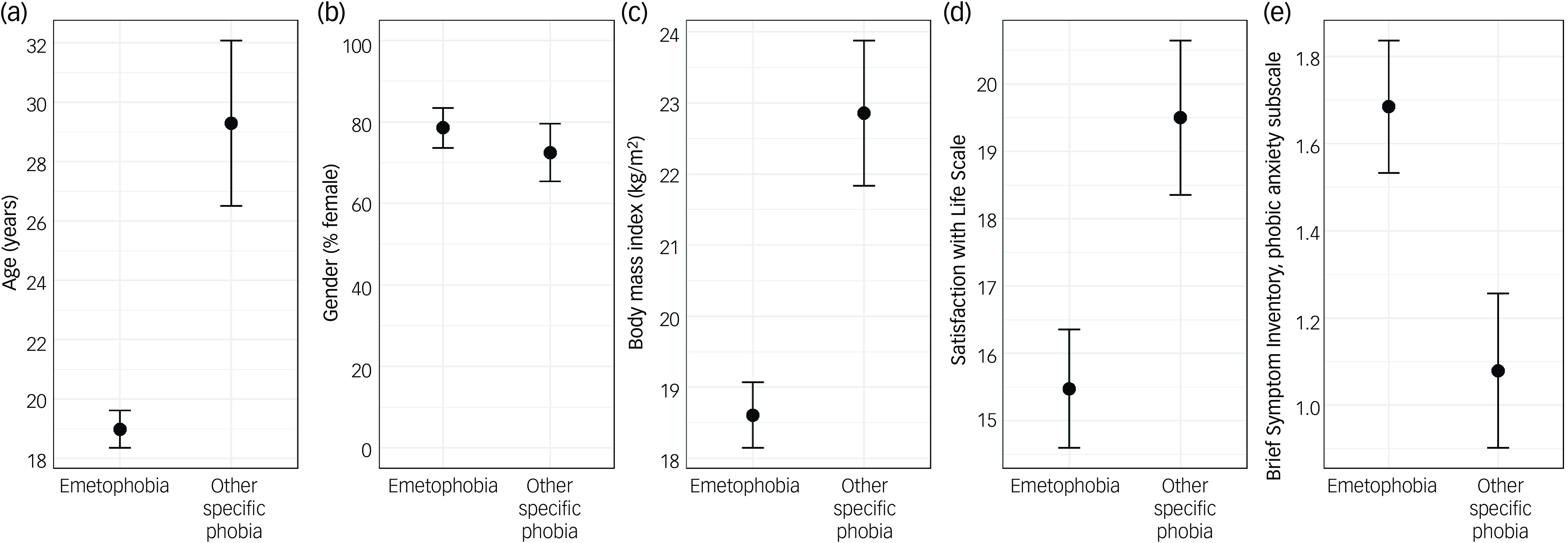

Figure 1 depicts differences between in-patients with emetophobia and those with other specific phobias. As can be seen, the former were younger (a finding that is also in line with Veale and colleagues’ study), had a lower body weight and reported both lower life satisfaction and higher phobic anxiety. In contrast to Veale and colleagues’ study, gender distribution did not differ between groups in this study. However, the female:male ratio of 9:1 in adults reported by Veale and colleagues Reference Veale, Beeson and Papageorgiou11 is in accord with a recent meta-analysis that produced a pooled estimate, across 21 samples, of 91% of (mostly adult) persons with emetophobia being female. Reference Meule, Seufert and Kolar4

Fig. 1 (a) Mean age, (b) percentage of females, (c) mean body mass index, (d) mean sum scores on the Satisfaction with Life Scale and (e) mean scores on the phobic anxiety subscale of the Brief Symptom Inventory in persons with emetophobia and those with other specific phobias at admission to in-patient treatment. Error bars indicate s.e.m. This figure is based on the data reported in ref. Reference Meule, Zisler, Metzner, Voderholzer and Kolar13

In conclusion, emetophobia is a rare condition that, nonetheless, appears to be one of the most commonly treated specific phobias. Although it can usually be treated in an out-patient setting, Reference Boschen and Jones15 its impairing impact on daily functioning sometimes necessitates more intensive in-patient treatment. While early reports of emetophobia date back to the mid-20th century, research has only recently begun systematically to examine its distinct characteristics. Given its debilitating nature and unique clinical presentation, further research is essential to refine treatment approaches and raise awareness among both healthcare professionals and the general public.

Funding

No funding was received for the preparation of this work.

Declaration of interest

None.

Adrian Meule, PhD, is a senior scientist and lecturer in the Department of Psychology at the University of Regensburg, Germany, specialising in clinical psychology.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.