The Berlin puzzle

On 18 May 2020, Germany's Chancellor Angela Merkel surprised policy makers and observers alike. Together with France's President Emmanuel Macron, Angela Merkel called to set up an EU‐wide recovery package to help member states offset the socio‐economic damages caused by the Corona pandemic. The Franco–German initiative envisioned the creation of a debt‐financed and grants‐based fund amounting to €500 billion and administered by the Commission, which would be tasked with borrowing capital on financial markets. This initiative provided a breakthrough for what would subsequently become Next Generation EU (NGEU), a comprehensive spending package, which contains €390 billion in grants and €360 billion in loans. NGEU marks a significant break with the austerity‐based EU response to the Euro crisis, which was championed by the German government at the time.

The German government's support for such an ambitious fiscal instrument is puzzling, to say the least. For decades, German governments have projected their ‘ordoliberal tradition and stability culture’ (Matthijs & McNamara, Reference Matthijs and McNamara2015, p. 234) onto the EU's economic and monetary integration agenda. During the Euro crisis, Germany was among the first governments to rule out joint debt instruments, such as Eurobonds. Instead, it tied financial assistance to austerity measures and structural reform programs in debt‐ridden Eurozone countries. Chancellor Merkel and Germany's finance minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, both stressed in 2012 that there would be no Eurobonds and hence no joint debt instrument during their lifetimes. Angela Merkel's volte‐face in the context of the Corona pandemic is thus ever more remarkable. Only weeks before the Franco–German announcement on the fiscally ambitious recovery fund, the German government had still sided with like‐minded, fiscally conservative member states, the so‐called ‘frugal’ alliance, who opposed an EU‐wide grant‐based fiscal stimulus package (Fleming et al., Reference Fleming, Brunsden and Khan2020). What, then, explains Germany's fiscal policy U‐turn in the EU against the backdrop of the Corona pandemic?

We argue that the German government's support for EU‐wide fiscal burden‐sharing, in the context of the Corona pandemic, cannot be adequately understood without the framing of the Corona pandemic as a crisis that was no one's fault. When the pandemic hit Europe in early March 2020, German government officials realised that existing EU policy measures proved inadequate to muster an effective crisis response. To avoid the ‘common bad’ of a looming pan‐European recession and socio‐economic crisis, there was a strongly perceived need that European fiscal cooperation had to be stepped up. In the debate over the EU‐wide crisis responses, a dominant crisis framing emerged depicting the Corona pandemic as a natural disaster. Framing the pandemic as a crisis for which no one could be blamed made calls for EU‐wide solidarity through expansive fiscal burden‐sharing increasingly uncontested. The German government's acceptance of a bold fiscal response that included fiscal burden‐sharing can only be understood against the backdrop of such a crisis framing.

Drawing on insights from the Euro crisis allows us to treat it as a ‘shadow case’ (Soifer, Reference Soifer2020), which in turn, enables us to identify important similarities and differences regarding the German government's response during the Corona crisis. During both crises, the German government supported EU‐wide fiscal measures to overcome negative interdependence and deficient EU capacities. Throughout the Euro crisis, the government did not become tired of mentioning domestic economic mismanagement and fiscal profligacy in the debtor states as the main sources of the crisis, and was adamant that the countries hit hardest by the crisis had mainly themselves to blame (Matthijs & McNamara, Reference Matthijs and McNamara2015). During the Euro crisis, crisis frames remained vigorously contested amongst the Eurozone states, calling for fiscal burden‐sharing and European solidarity on the one hand, and those claiming national responsibility and opposing fiscal burden‐sharing on the other hand. In the course of the Corona crisis, by contrast, such national responsibility‐frames – arguments blaming member states for their own shortcomings – became increasingly untenable. Governments in support of a joint debt instrument argued that since the crisis was nobody's fault, a display of European solidarity, expressed through fiscal burden‐sharing, was the appropriate course of action. While the predominant framing of the Corona crisis as one about European solidarity affected the German government's positioning on transnational fiscal‐sharing, we do not find any evidence that the government's preferences about transnational fiscal‐sharing actually changed. Acting in line with the EU solidarity frame during the Corona pandemic did not imply that the government changed its overall preference for fiscally prudent policies in the EU. The government emphasised that the exceptional circumstances that the Corona pandemic brought upon the EU required a change in course, albeit not a change in orientation. Comparing the German government's response to the Corona crisis with its Euro crisis response suggests that the kind of crisis framing, whether a European solidarity or national responsibility framing prevails, is an important scope condition for the eventual crisis response, that is, if there is sufficient support for transnational solidarity expressed through burden‐sharing measures.

This paper is structured as follows. In the next section, we place our paper in the existing literature on EU crisis politics and discuss its shortcomings in explaining the German Corona crisis response. Against this backdrop, we introduce our theoretical argument which sheds light on the conditions under which crisis politics in the EU is amenable to transnational solidarity. In ‘Analysis: Why Germany supported the Corona recovery fund’ section, we present our empirical analysis of the German response to the Corona crisis before we discuss the broader theoretical and empirical implications of the analysis in the final section.

Contribution to the literature

This paper contributes to the growing literature on fiscal burden‐sharing in the EU in times of crisis (see, e.g., Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2021; Schelkle, Reference Schelkle2021). We distinguish two main strands in this literature, which emphasise that governments’ preferences and ensuing political conflicts over fiscal burden‐sharing are either shaped by structural differences in economic interests or differences in economic ideas (see Wasserfallen, Reference Wasserfallen, Adamski, Amtenbrink and de Haan2023). For those emphasising differences in economic interests, preferences about fiscal burden‐sharing relate to a state's position in patterns of international economic interdependence. During the Euro crisis, fiscally challenged states that were in a debtor position had a strong preference for EU‐wide fiscal burden‐sharing, while creditor states, less affected by the crisis, preferred national solutions (see, among others, Biermann et al., Reference Biermann2019; Schimmelfennig, Reference Schimmelfennig2015, Reference Schimmelfennig2018). Germany – a creditor state – preferred that the costs of economic adjustment would be borne by the debt‐ridden countries. Fiscal support would have to be tightly circumscribed, based on strict conditionality requirements. Debtor states, by contrast, called for more extensive joint European action, among others through the introduction of common debt instruments, such as Eurobonds. In the context of the Corona pandemic, the German government's preferences for a limited European fiscal policy have remained largely intact (Schramm, Reference Schramm2023). Initially, it positioned itself clearly in the camp opposing fiscal burden‐sharing (Krotz & Schramm, Reference Krotz and Schramm2022). As the pandemic unfolded, the German government shifted its position and came to support a fiscally more ambitious response. Unlike in the Euro crisis, policy makers in Germany had come to realise that the fiscal and economic costs of the crisis were more symmetrically distributed across the EU, which made a joint crisis response necessary (see Schramm, Reference Schramm2023), because nothing less than preserving the functioning of the Single Market was at stake (Becker, Reference Becker2022; Bulmer, Reference Bulmer2022, p. 176; Schelkle, Reference Schelkle2021: 47). What is striking from this perspective, though, is the speed with which the German government changed course in the spring of 2020, at a time when a majority of major economic interest groups and peak associations were vocally sceptic of fiscal burden‐sharing measures. Was the German government's fiscal policy U‐turn then simply the consequence of its assessment that Germany's economic environment was taking a turn for the worse and that a sizable EU‐wide fiscal response was the solution?

Another strand of literature highlights that states’ preferences for EU‐wide fiscal burden‐sharing are shaped by economic ideas held by domestic and transnational political and economic elites (Blyth, Reference Blyth, Béland and Cox2011; Brunnermeier et al., Reference Brunnermeier, James and Landau2016; Matthijs, Reference Matthijs2015; Matthijs & McNamara, Reference Matthijs and McNamara2015). According to this perspective, ‘ideational power’ (Carstensen & Schmidt, Reference Carstensen and Schmidt2018) – not positional or material attributes – is constitutive of actors’ interests and preferences. In the context of the Euro crisis, economic ideas were widely employed to (de‐)legitimise fiscal risk‐sharing proposals, exemplified in the ‘Northern saints’ versus ‘Southern sinners’ metaphor (Matthijs & McNamara, Reference Matthijs and McNamara2015). Matthijs (Reference Matthijs2015) argues, for instance, that the power intrinsic to ideas can even lead policy makers to propagate self‐harming policies. By clinging to its ordoliberal creed, the German government actually contributed to the worsening of the crisis. If we conceive of economic preferences as deeply entrenched and institutionalised economic ideas, explaining the German government's fiscal burden‐sharing U‐turn during the Corona pandemic is puzzling, to say the least. Ideas do not change overnight and neither do actor coalitions supportive of ordoliberal ideas suddenly disappear. Could new or alternative ideas have come to the fore? Genschel and Jachtenfuchs (Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2021) argue, for instance, that unlike in the Euro crisis, the Corona crisis paved the way towards fiscal risk‐sharing because the idea of solidarity was effectively ‘debordered’ from its national container: Transnational solidarity with fellow Europeans became a widely supported and legitimate idea in the context of the Corona pandemic. As a result, member states that opposed burden‐sharing measures were now heavily on the defensive (Smeets & Beach, Reference Smeets and Beach2023). This sounds plausible, but the mechanism remains obscure. How precisely did the notion of transnational solidarity overwrite ordoliberal policy ideas and challenge its supporters to change course? In an attempt to reconcile ideational and economic accounts, Crespy and Schramm (Reference Crespy and Schramm2021, p. 6) point to the ‘co‐construction’ of material interests and crisis discourse to explain the German government's breaking of the ‘budgetary taboo’ in the context of setting up NGEU. Yet, their argument suggests that material interests only become intelligible through shared ideas, thus emphasising the primacy of ideas and shared discourse.

Both strands of literature offer only partial accounts for the German government's fiscal policy U‐turn during the Corona pandemic. Economic interest‐based explanations highlight patterns of economic interdependence and crisis affectedness and can plausibly explain why EU governments demanded a joint EU‐wide response to the Corona pandemic as well as why some governments were more in favour of a joint response than others. Yet, the particular design of that policy response remains elusive. Ideational accounts, by contrast, fail to explain why and how the notion of transnational solidarity became influential so as to override the German government's long‐held opposition to fiscal burden‐sharing. Our approach goes beyond the existing literature in two ways. First, we present a causal sequence, which systematically links materialist with ideational mechanisms, to explain the German government's crisis response. In doing so, second, we make a broader theoretical contribution by spelling out conditions under which crisis politics can expand the scope of possible crisis response outcomes, giving way to fiscal burden‐sharing. The ensuing section develops this argument in detail.

Theory: Interdependence, crisis framing, frame legitimation and burden‐sharing

To explain why the German government came out in support of fiscal burden‐sharing in the context of the Corona pandemic, we develop a three‐step causal mechanism. First, the prospect of negative interdependence triggers a perceived need for joint action in order to avoid a ‘common bad’. Second, EU member states and other EU actors engage in framing contests about what solidarity entails in a particular crisis context. The emergence of a solidarity framing is rendered possible if the crisis can be successfully framed as an exogenous crisis, which is no one's fault. Third, to the extent that the European solidarity frame and its associated policy prescriptions becomes increasingly uncontested, governments whose preferences do not align with these prescriptions face mounting social pressure to support burden‐sharing policies.

Step 1: Negative interdependence: Avoiding a ‘common bad’

International interdependence is the main driving force behind EU integration in two of the main integration theories, liberal intergovernmentalism and neofunctionalism. To reap the benefits of transnational exchanges, such as cross‐border trade and investment, or to avoid negative policy externalities, for example, through regulatory dumping, states engage in policy coordination. The more dependent a state is on other states to obtain its desired policies or to avoid undesired policies, the stronger the demand for policy coordination. In short, interdependence affects integration preferences. Consequently, when the scope of interdependence changes, so do states’ integration preferences (see Leuffen et al., Reference Leuffen, Rittberger and Schimmelfennig2022, pp. 11−13). Integration theories differ in the analytical status they ascribe to interdependence. For liberal intergovernmentalism, changes in interdependence result from exogenous shocks and trends (Moravcsik, Reference Moravcsik1998); for neofunctionalism, changes in interdependence are endogenous to prior steps of integration (see, for instance, Stone Sweet & Sandholtz, Reference Stone Sweet and Sandholtz1997). This is because international dependence triggers processes of self‐reinforcement (Pierson, Reference Pierson1996) or ‘spillover’ (Haas, Reference Haas1968), which breed further integration. As integration progresses, international interdependence increases and ‘[i]ntegration preferences become more endogenous’ (Leuffen et al., Reference Leuffen, Rittberger and Schimmelfennig2022, p. 398).

Drawing on neofunctionalism, we expect the Corona pandemic to unleash an endogenous, path‐dependent preference‐formation process. To the extent that EU member states do not possess the economic and fiscal capacities to unilaterally cope with the economic consequences of the pandemic, they will have to turn to existing EU policy instruments to avoid negative externalities, such as the contraction of cross‐border trade, private and corporate solvency problems, another banking crisis or spiralling public debt. The Euro crisis has given rise to unprecedented fiscal and financial integration because of the deficiencies of existing EU policies: the Eurozone has ‘failed forward’ (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Kelemen and Meunier2016). Yet, fiscal integration remains partial and contested. The ECB's bond‐buying programmes, which it introduced in the wake of the Euro crisis, are subject to political and legal challenges. Likewise, issuing common European debt continued to be an anathema as the Euro crisis gradually abated. Yet, the Euro crisis example shows that unless the member states were ready to risk a systemic challenge – the breakdown of the Euro – they perceived a clear need to advance supranational integration in another area to stabilise the system – by moving ahead with limited fiscal policy integration. Overall, as policy interdependence increases with further integration, the EU becomes more vulnerable if relationships of interdependence are interrupted through shocks and crises (see Pierson, Reference Pierson1996). When such crises loom, member states are likely to support joint action to mitigate negative interdependence. In line with neofunctionalism, this argument implies that as integration progresses, member states’ preferences become increasingly endogenous to prior integration (Leuffen et al., Reference Leuffen, Rittberger and Schimmelfennig2022). Member states, such as Germany, that were adamantly opposed to any form of fiscal integration prior to the Euro crisis, subsequently acquiesced to a limited form of fiscal integration during the Euro crisis in order to minimise the arguably higher costs a ‘common bad’ – the breakup of the Eurozone – would imply (Schimmelfennig, Reference Schimmelfennig2015).

What are the implications of this argument for analysing Germany's integration preferences in the context of the Corona pandemic? As the Corona crisis exposed the socio‐economic vulnerabilities of the EU's highly integrated economies, governments should have come to realise that avoiding a ‘common bad’ required joint action, including a fiscal stimulus to avoid economic contraction. This argument does not, however, help us explain why Germany would propose issuing common debt and introducing over €500 billion worth of grants alongside loans (that would have to be paid back eventually). In other words: Why did member states not only agree on the lowest common denominator to avoid a ‘common bad’, by drawing on the EU's existing regulatory and budgetary instruments, but also opted for deeper fiscal integration (see Rhodes, Reference Rhodes2021)? To answer this question, we need to look at the crisis framing and how the notion of solidarity was contested in the context of the Corona pandemic.

Step 2: Framing contests: What kind of crisis?

Post‐functionalism assumes that the question about who deserves solidarity tends to be answered in the positive by political communities characterised by a strong sense of self‐identification. To the extent that EU policies increasingly touch upon ‘core state powers’ (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2021) and carry substantial (re‐)distributive implications (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009), calls for EU‐wide burden‐sharing, and hence solidarity, have become commonplace, especially in times of crisis. Yet, the question of whether the sense of community and identification with the EU is strong enough to introduce sizable burden‐sharing measures in the EU, is hotly debated (Börzel & Risse, Reference Börzel and Risse2018; Kuhn, Reference Kuhn2019; Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Reference Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2021; Ferrara & Kriesi, Reference Ferrara and Kriesi2022). Crises are highly disruptive events. Not only do they call into question the problem‐solving capacity of a polity, they also tend to have considerable and uneven distributive consequences, since not everyone is equally affected. How do twenty‐seven EU member states respond to calls for EU‐wide solidarity? An answer to this question inevitably requires guidance from social norms and values shared by those affected by the crisis: Crises render community values salient; they can even ‘constitute urgent threats to core community values’ (Boin et al., Reference Boin, ’t Hart and McConnell2009, pp. 83−84). Who deserves EU‐wide solidarity? And when? To address these questions, we need to look at the particular framing of a crisis for the public. Crises are public ‘framing contests’ (Boin et al., Reference Boin, ’t Hart and McConnell2009). To frame a problem or crisis is ‘to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation’ (Entman, Reference Entman1993: 52). One crucial aspect of political framing contests in times of crisis revolves around the question of responsibility: Who is responsible and hence to blame for a policy failure? Why did the failure come about? How can it be redressed?

Depending on their preferences for fiscal burden‐sharing, political actors employ different ‘causal frames’ (Boin et al., Reference Boin, ’t Hart and McConnell2009, p. 87) to support or oppose demands for fiscal burden‐sharing. The Euro crisis is an instructive example, because demands for fiscal burden‐sharing were highly contested. ‘Debtor’ states demanded European solidarity through fiscal burden‐sharing; ‘creditor’ states stressed the ‘debtor’ states’ fiscal woes were a matter of national responsibility rather than of transnational, European solidarity. By employing ‘causal frames’, actors advanced different interpretations of the crisis with regard to questions about responsibility and deservingness. For proponents of a national responsibility frame, crisis‐induced domestic fiscal challenges should not be redressed through EU‐wide fiscal risk‐ or burden‐sharing, but through domestic fiscal and economic reforms, because fiscal and economic hardship is caused by ‘bad’ policies and is thus a national responsibility. The actions leading to domestic socio‐economic hardship are portrayed as controllable, which puts the brunt of responsibility on domestic policy makers (Stone, Reference Stone2012, pp. 209–210). Following this logic, transnational fiscal solidarity would reward a government's fiscally irresponsible behaviour and breed moral hazard (Genschel & Hemerijck, Reference Genschel and Hemerijck2018, pp. 3–4). Proponents of a national responsibility crisis framing stress the ‘home‐made’ (endogenous) source of a crisis. In stark contrast, proponents of the European solidarity frame emphasise exogenous crisis sources, such as outside actors, uncontrollable forces and accidents (Boin et al., Reference Boin, ’t Hart and McConnell2009, p. 87, see also Stone, Reference Stone2012, p. 208). In the Euro crisis example, ‘debtor’ states pointed to external circumstances and uncontrollable forces, such as the institutional design flaws of the EMU or greedy financial markets. Calls for transnational fiscal solidarity are thus justified by externalising the responsibility for the crisis and its consequences.

What are the implications of this argument for analysing when and why Germany came to align itself with a European solidarity frame? With regard to the Corona pandemic, differential crisis affectedness should be reflected in actors advancing different ‘causal frames': The countries hardest hit by the pandemic should be the most vocal in support of a European solidarity frame, while those least supportive of fiscal‐sharing instruments should emphasise a national responsibility frame.

Step 3: Frame legitimation: Normative compliance‐pull

Framing contests over transnational burden‐sharing can have essentially two outcomes: The first is that actors are either unable to resolve their disagreements or strike an agreement that reflects the lowest common denominator. In the latter case, the framing contest remains undecided, because both the European solidarity and national responsibility frames can draw on broad political support. A frame becomes dominant when it enjoys widespread legitimacy in the public and among the actors involved in the framing contest. Absent a widespread and agreed‐upon understanding of who deserves fiscal solidarity, social enforcement mechanisms, such as blaming, shaming or shunning, remain unavailable to actors propagating transnational burden‐sharing. As a consequence, the compliance‐pull of calls for fiscal solidarity remains weak (see Schimmelfennig, Reference Schimmelfennig2003; Rittberger & Schimmelfennig, Reference Rittberger and Schimmelfennig2006). The second possible outcome is that one frame ‘wins’ the contest, which occurs when one frame comes to enjoy widespread legitimacy in the public and amongst policy makers. When is this likely to be the case? A frame enjoys widespread legitimacy if the ‘causal’ story it tells about crisis responsibility and deservingness of solidarity aligns with norms that are constitutive for the respective community as a whole. When activated, such norms define a standard of legitimacy that defines the duties of the members of a given community and compels them to justify their (self‐interested) behaviour in light of this standard (see Schimmelfennig, Reference Schimmelfennig2001). By subscribing to the community's constitutive norms and values, community members can become normatively and rhetorically entrapped, when their behaviour contradicts those community norms they had subscribed to.

The question now is under what conditions can a European solidarity frame become dominant and define a standard of legitimacy, which commands a normative compliance‐pull on EU member states who initially opposed such a frame? The distinction between frames that emphasise the endogenous or exogenous causes of a crisis is crucial to explain when and why a European solidarity frame can become predominant, command widespread legitimacy and thereby place normative pressure on member states who oppose European solidarity. If a crisis can be effectively framed as an unforeseeable, uncontrollable event, it would fall into the same category as a natural disaster or any accident with an exogenous cause. Socio‐economic hardship brought about by a crisis framed as exogenous is not attributed to ‘bad’ policies or faulty political choices, but follows a causal narrative that stipulates ‘yes, this is big, bad and urgent, but this is not our doing; all of us need to unite to cope with this unfortunate tragedy’ (Boin et al., Reference Boin, ’t Hart and McConnell2009, p. 88). A crisis that can be framed as accidental should thus be ‘an easy issue for European solidarity because such disasters have exogenous causes’ (Genschel & Hemerijck, Reference Genschel and Hemerijck2018,p. 4). The Euro crisis is illustrative because the framing contest between European solidarity and national responsibility frames was never effectively resolved. The group of states claiming that the root causes of the Euro crisis were endogenous – the result of ‘bad’ domestic policy – remained vocal during the course of the Euro crisis. Moreover, public support for transnational solidarity for indebted states ranks low among European publics, compared with exogenous crisis causes, such as natural disasters or military attacks (Genschel & Hemerijck, Reference Genschel and Hemerijck2018, p. 4). Calls for European solidarity could thus not command the kind of legitimacy that would have normatively compelled sceptics of fiscal burden‐sharing to cave in.

What does this argument imply for our analysis of Germany's fiscal policy U‐turn in the context of the adoption of NGEU? We would expect a process of frame legitimation to ensue: The proponents of fiscal burden‐sharing are likely to emphasise that the socio‐economic fallout from the crisis was exogenous and hence no one's fault. Critics of expansive fiscal burden‐sharing, which initially included the German government, should eventually succumb to accepting demands for transnational fiscal solidarity since arguments to withhold fiscal support would contradict the government's commitment to the European solidarity frame and thus lack a justificatory basis. As demands for transnational solidarity become increasingly uncontested, financial aid should thus become the imperative. Conversely, we would expect arguments and behaviours contesting European solidarity and its implications to be openly delegitimised. In the ensuing section, we will empirically probe our three‐step causal sequence to account for the Berlin puzzle.

Analysis: Why Germany supported the Corona recovery fund

We carry out a theory‐testing process‐tracing analysis (Beach & Pedersen, Reference Beach and Pedersen2019) to account for the drivers behind the German government's fiscal response to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Process‐tracing is particularly well‐suited to analyse the German government's change of preference as it allows for within‐case inferences about the presence or absence of causal mechanisms in single case studies (Bennett & Checkel, Reference Bennett, Checkel, Bennett and Checkel2014, p. 4). By closely tracking the change of the German government's preferences over time, it reveals the sequences and mechanisms that caused Germany to propose the Corona recovery fund. To probe the causal mechanisms specified in the previous section, the article employs different sources. First, we analyse the information gained in nine semi‐structured interviews conducted between April 2021 and June 2021.Footnote 1 The interviewees were selected to represent a wide range of policy makers from both German and European institutions. On the national level, interviews were conducted with public officials from the German Federal Chancellery, the Finance Ministry and the Bundestag. On the European level, interviewees included officials from the Commission and European Parliament (EP). To obtain candid accounts, interviewees were guaranteed confidentiality. We triangulate the evidence gained from the interviews with information drawn from official policy documents, speeches and news sources.

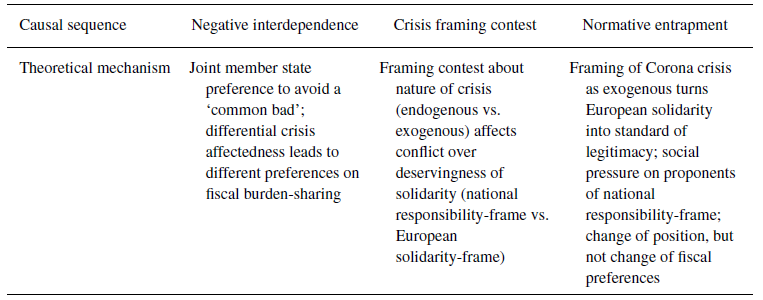

In the following, we will demonstrate that the German government's support for the Corona recovery fund can be explained by the causal mechanism formulated in the preceding section. The empirical analysis will be organised along the sequence of the causal mechanism. Table 1 provides a summary overview of the causal mechanism.

Step 1: Worse than the Euro crisis: The perceived imperative to avoid a ‘common bad’

Table 1. Overview of the theoretical sequence

In the spring of 2020, the rapid spreading of the Coronavirus throughout Europe caught health systems and policy makers off guard. Health measures and lockdowns resulted in an economic slowdown across the EU, affecting cross‐border trade, supply chains, labour migration as well as depressing levels of consumption. Yet, the ability of different EU member states to provide an immediate fiscal response to cushion the socio‐economic challenges produced by the pandemic proved to be uneven. This state of affairs was strikingly similar to the Euro crisis, where ‘Northern’ member states were less affected economically and possessed better fiscal capacities than many of the ‘Southern’ member states, who faced unsustainable debt burdens and prohibitive refinancing costs. Not only was the assessment of the similarity between the two crises shared among public officials and economists (Interview 8), as a senior official from the German Chancellery emphasised, but also the German government was initially convinced that it was well capable of cushioning the economic damage caused by the pandemic on its own (Interview 7). Convinced to possess the resources to address the economic fallout of the crisis unilaterally, the German government displayed little interest in an EU‐wide fiscal response at the outset of the pandemic. On 16 March 2020, German Finance Minister Olaf Scholz even dismissed proposals for loans from the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) as unnecessary and ‘premature’ (Greive & Hildebrand, Reference Greive and Hildebrand2020, own translation).

During this very early phase of the pandemic, the German government shared the same position as the ‘frugal’ alliance, since it sought to minimise the EU's fiscal role in managing the impact of the crisis (see Krotz & Schramm, Reference Krotz and Schramm2022). Hence, the first set of measures to combat the economic impact of the crisis were based on relaxing EU state aid rules as well as making use of already existing EU financial support measures. The German government envisioned the ECB to become a key actor to combat the economic impact of the Corona crisis. According to a German official quoted in the Financial Times, the prevalent notion was that ‘member states didn't need to do any fiscal stuff because the ECB would always save the day’ (Mallet et al., Reference Mallet, Chazan and Fleming2020). In fact, the ECB appeared to have heeded these expectations when, on 18 March, it announced the launch of the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP), a temporary asset purchase programme of private and public sector securities to counter the risks that the pandemic posed to the Eurozone. Meanwhile, the German government took extraordinary fiscal measures to support its national businesses, proposing funds to support small businesses as well as big companies, totalling several hundreds of billion euros. Facilitated by the prospect of low borrowing costs, the Bundestag swiftly passed the respective legislation, a supplementary budget as well as a suspension of the debt brake, the so‐called schwarze Null.

As the pandemic unfolded, concerns that the looming economic crisis would turn into a systemic crisis, as was the case during the sovereign debt and Euro crisis, endangering the stability of the Eurozone resurfaced. For the Eurozone as a whole, the massive plunge projected by several economic and manufacturing indicators suggested that the Eurozone economies were expected to contract faster in the second quarter of 2020 than they did during the crisis of 2008–2009. Despite Germany's privileged fiscal and economic position, its economic well‐being is nevertheless tied to the block's overall economic vitality and the stability of the common currency. Fear was looming that Italy would become the EU's latest ‘construction site that could not be saved’ (Interview 2, own translation).

By the end of March 2020, the risk of a Eurozone breakdown became real and the prospect of a significant contraction of EU‐wide trade was equally perceived as increasingly damaging for Germany's economy. According to a senior official from the German Chancellery, it was ‘not up to debate’ (Interview 4, own translation) that something bold had to be done. The unparalleled economic implications of the pandemic heightened the consequences of negative interdependence. Marking an economic downturn of ‘historic proportions’ (Interview 7, own translation), the pandemic was seen to pose the ‘greatest economic difficulty since World War II’ (Interview 1, own translation). Even for Germany, economists predicted a deeper economic recession than at the height of the Euro crisis (Karnitschnig, Reference Karnitschnig2020). Regarding its economic implications, one Chancellery official said that the pandemic was ‘massively different in its breadth and depth than the Euro crisis’ (Interview 4, own translation). This assessment also necessitated a reconsideration of the adequacy of existing fiscal policy instruments at the EU's disposal. The pandemic thus presented a challenge to develop instruments that would ‘provide sufficient financial assistance and be effective in the end’ (Interview 1, own translation). As explained by a senior official from the Federal Chancellery, the instruments introduced in the context of the Euro crisis were considered insufficient: It was simply impossible to ‘continue to work in a pandemic with the […] instruments and the procedures that apply in normal life’ (Interview 4, own translation). Avoiding the ‘common bad’ of yet another episode of currency instability, the looming threat of an EU‐wide economic contraction coupled with insufficient EU‐level capacities to effectively address these challenges, the German government came to re‐evaluate its stance on supranational fiscal cooperation.

By early April 2020, the German government had agreed to set up new rescue instruments specifically designed for the Corona pandemic. Endorsing a joint European fiscal response in principle, the Chancellery engaged in an intensive bilateral dialogue with the Élysée to discuss what form this joint fiscal response should take (Krotz & Schramm, Reference Krotz and Schramm2022). While the French advocated an ambitious, standalone recovery instrument, which involved joint debt, they were aware of Germany's aversion to fiscal burden‐sharing (Herszenhorn et al., Reference Herszenhorn, Bayer and Momtaz2020; Crespy & Schramm, Reference Crespy and Schramm2021). Thus, both governments sought to develop a proposal that would be acceptable to both sides (Interview 7). The first results of these deliberations became visible on 9 April, when the Eurogroup released a statement on the comprehensive economic policy response to the pandemic in which the Euro area finance ministers decided on an emergency Eurozone rescue package worth €540 billion consisting of loans and guarantees for workers, companies and health‐related state expenditures (European Council, 2020). The close working relationship between Finance Ministers Olaf Scholz and Bruno Le Maire was particularly crucial in overcoming Dutch and Italian resistance to some aspects of the emergency rescue package (Chazan et al., Reference Chazan2020). As such, the Franco–German ‘embedded bilateralism’ (Krotz & Schramm, Reference Krotz and Schramm2022) enabled the balancing out of divergent member state interests. The package served to ensure rapid market stabilisation (Interview 5) and even led observers to judge that the pandemic ‘revives Franco–German relations’ (Chazan et al., Reference Chazan2020).

Still, the Franco—German relationship remained strained due to their different positions on a joint debt instrument (Chazan et al., Reference Chazan2020). While the French government continued lobbying for the introduction of Eurobonds, Germany followed its ‘anything but fiscal burden‐sharing’ mantra. As late as April 2020, Chancellor Merkel publicly rejected debt mutualisation (The Federal Government, 2020b). As aptly described by an EU diplomat, quoted in the Financial Times in response to the first emergency Eurozone rescue package: ‘After a somewhat slow start, the Franco–German engine worked at full speed during the last few days and did its magic […]. But we should not pretend that the deeper debate over debt mutualisation is resolved’ (Chazan et al., Reference Chazan2020).

On March 26, during a video summit amongst EU heads of state and government, the battle lines seemed to be firmly drawn followed by heated discussions (Fleming et al., Reference Fleming, Brunsden and Khan2020) in an atmosphere of ‘anger and resentment’ (Herszenhorn et al., Reference Herszenhorn, Bayer and Momtaz2020). Chancellor Merkel and the ‘frugal’ camp left no doubt that joint debt was ‘something out of fiscal fantasyland’ (Herszenhorn et al., Reference Herszenhorn, Bayer and Momtaz2020). Chancellor Merkel is reported to have told her Italian counterpart, Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte, that if he was waiting for Coronabonds, they will never come (Alexander, Reference Alexander2020; Hoffmann et al., Reference Hoffmann, Hornig, Mayr, Medick, Müller, Sandberg and Zuber2020). According to a Commission official, the discussions were ‘painful’ and resulted in an ‘ugly, ugly atmosphere where […] bad things were said to each other’ (Interview 6). And following the summit António Costa, the Portuguese Prime Minister, qualified the Dutch finance minister's comments as ‘repugnant’ (Herszenhorn et al., 2020). The March 26 summit marked a low‐point in the EU leaders’ attempts to display unity and to resolve the combat around the socio‐economic fallout of the Corona crisis. At the same time, March 26 also marked a turning point. Despite the acrimony of the debate over the kind of joint response the EU should adopt, political leaders came to share the notion that the crisis was ‘no one's fault’ and that its solution required a joint European effort. This emerging framing of a crisis that necessitated European solidarity, played an important role in unlocking the deadlock between the two camps and in pushing the German government to agree to a common debt‐instrument.

Step 2: The case for European solidarity: No more sinners, only victims

To explain the German government's shift on the question of shared European debt, it is thus necessary to look at the framing of the Corona crisis. The unfolding crisis framing contest displayed remarkable similarities to the Euro crisis. While EU leaders agreed early on that a recovery fund of a ‘sufficient magnitude’ was needed to deal with ‘this unprecedented crisis’,Footnote 2 what remained contested was the financing modalities of the envisaged recovery package. The ‘frugal’ alliance of ‘Northern’ states, initially led by Austria, Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands, argued that a global health crisis should be addressed with conditionality‐based rescue instruments attached to the loans and dismissed the use of grants as an inefficient use of money, endangering the EU's finances.Footnote 3 On the other side, a larger group of member states from Eastern and Southern Europe, at times referred to as the ‘friends of cohesion’, pleaded for an expansive fiscal stimulus that should be mainly based on grants rather than loans in order not to add to their already high debt‐burdens (see Drachenberg, Reference Drachenberg2021). Similar to the Euro crisis, solidarity became a widely debated issue amongst and within EU member states: Who has a legitimate claim to transnational solidarity? How should solidarity be practiced (Genschel & Hemerijck, Reference Genschel and Hemerijck2018; Wallaschek, Reference Wallaschek2020; Hobbach, Reference Hobbach2021)? During the Euro crisis, mainly ‘Southern’ EU member state governments insisted that a break‐up of the Eurozone could be best prevented by a show of transnational, European solidarity, practiced via fiscal burden‐sharing. Addressing the root causes of the crisis and finding solutions was portrayed as a European responsibility that required European solidarity. Other, mainly ‘Northern’ governments, counter‐claimed that one of the key problems that led to the crisis in the first place was fiscally irresponsible behaviour on the part of indebted (‘Southern’) member states, which required fiscal prudence and domestic reforms rather than solidarity defined as transnational risk‐sharing (see Matthijs & McNamara, Reference Matthijs and McNamara2015). Their emphasis thus lay on states assuming national responsibility before they can demand European solidarity. In sum, all governments were in agreement that solidarity was an important value to uphold, especially in such taxing times, yet there was strong disagreement about what solidarity entailed.

By contrast, the fact that no member state could be plausibly blamed for the Corona pandemic was crucial for changing the framing of the acceptability of joint‐debt during the Corona crisis. Unlike in the Euro crisis, the European solidarity frame and associated demands for EU‐wide joint‐debt became the dominant crisis frame. According to a senior official from the German Finance Ministry, the central aspect in making a debt‐financed and a grants‐based recovery fund politically viable, was the general impression among the political elite and the population that no one was effectively to blame for the crisis: ‘The pandemic wasn't anyone's fault. That is a completely different reading than the one that very quickly prevailed in the Euro crisis. […] Back then, serious accusations came from both Germany and Greece in the form of: Who is actually to blame? And this question never came up during this pandemic’ (Interview 5, own translation). A senior official from the Chancellery highlighted that before the pandemic, Germany could always put blame on the debtor states for their own financial malaise (Interview 7). While a ‘saints versus sinners’ dichotomy characterised the overarching discourse during the Euro crisis (Matthijs & McNamara, Reference Matthijs and McNamara2015), the Corona crisis knew no ‘sinners’ only victims.

Hence, despite their varied preferences regarding the design of an EU‐wide financial response to tackle the economic effects of the Corona crisis, EU leaders shared the perception that the crisis called for European solidarity rather than solely national responsibility. As described by a senior official from the Chancellery, some countries were certainly hit harder by the pandemic than others, but this was not the impression that prevailed: ‘We were all shocked when we saw the pictures from Italy. We realised: This could be us!’ (Interview 7, own translation) Whereas the Euro crisis (as well as the migration crisis) resulted in ‘us’ versus ‘them’ narratives (Börzel & Risse, Reference Börzel and Risse2018; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Hutter & Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2019), the Corona crisis induced no such distinctions: There was no ‘othering’ – member states identified with each other and with their respective burden.

With preferences over the EU's joint financial response still divided and a German government opposed to proposals for Coronabonds or debt mutualisation, one could qualify the widespread appeals to European solidarity as shallow rhetoric or even insincere. We argue that this was not the case. What this constellation laid bare is a tension between ‘ought’ – a commitment to European solidarity – and ‘is’ – a lack of joint action due to conflicting preferences about how to practice European solidarity and hence transnational burden‐sharing. A tension of this kind, that is, between a shared normative commitment among community members and behaviour that contradicts such a commitment, is a condition that is conducive for effective normative pressure: It empowers actors who want to see the commitment upheld over actors whose behaviour conflicts with normative commitments (see Rittberger & Schimmelfennig, Reference Rittberger and Schimmelfennig2006). As we will see in the next section, this tension between ‘ought’ and ‘is’ helped bring about a joint response and thus sheds light on Germany's change of course.

Step 3: Normative pressure: Avoiding isolation and running out of arguments

Less than two months after the ‘[s]ummit debacle’ of 26 March (Herszenhorn et al., Reference Herszenhorn, Bayer and Momtaz2020), on 18 May, France and Germany announced an ‘initiative for the European recovery from the coronavirus crisis’, making the case for an ‘ambitious’ recovery fund and a proposal to allow the Commission to borrow on markets on behalf of the EU to finance the recovery instrument.Footnote 4 In contrast to its stance during the Euro crisis, where the German government adamantly opposed debt‐sharing measures, it now broke with this long‐standing taboo. What explains the government's ‘stunning shift, from guardian of austerity to a champion of a joint debt program’ (Herszenhorn et al., Reference Herszenhorn, Bayer and Momtaz2020)?

During the course of April 2020, the support for debt mutualisation grew at the European as well as at the domestic level. At the European level, several member states were quick to emphasise that the pandemic was no one's fault and beyond anyone's control, using these points to frame the Corona pandemic as a crisis requiring an EU‐level financial response that would not be an additional burden on member states’ public debts and, therefore, should not involve loan conditionality. Member states supporting a shared debt became much more open and vocal in accusing the ‘frugal’ alliance as well as the German government for their lack of solidarity. France, in particular, increased the pressure on the German government (Berretta, Reference Berretta2020; Crespy & Schramm, Reference Crespy and Schramm2021; Krotz & Schramm, Reference Krotz and Schramm2022). France's President Macron criticised the German position on various occasions in public, saying that it would be a historic mistake to say that ‘the sinners must pay’ as they did in the Euro crisis (Mallet & Khalaf, Reference Mallet and Khalaf2020). On 25 March, 2020 nine member states, including France, Italy and Spain, stepped up the pressure on Germany and the ‘frugal’ alliance by penning an open letter to European Council President, Charles Michel, demanding that European solidarity be put into action through a common debt instrument: ‘The case for such a common instrument is strong, since we are all facing a symmetric external shock, for which no country bears responsibility, but whose negative consequences are endured by all’ (Governo Italiano, 2020, italics added).

This open letter of the nine, chiefly initiated by Macron, had precisely the intention to put public pressure on Germany and the ‘frugal’ alliance, not through direct accusation, but by highlighting the urgency to follow up on commitments to transnational solidarity with joint action. By bringing Ireland's Toaiseach Leo Varadkar to sign the letter, the group of signatories even included a government that used to see itself rather close to the ‘frugal’ alliance. Overall, the nine signatories represented a sizeable and diverse group of states totalling 60 per cent of the EU's GDP. With the initiative proposed in the letter, France also broke the norm that France and Germany align their positions ahead of EU summit meetings. The intended message of this open letter was apparently not lost on Merkel (Berretta, Reference Berretta2020). One interviewee emphasised that the German government was left isolated and felt stupefied with regard to the open letter (Interview 5). According to a Commission official, the German government was ‘upset’ (Interview 6) and furious about the French move (Chazan et al., Reference Chazan2020). Officials from the German Finance Ministry and from the Commission identified the letter as critical in reframing the debate on a joint European debt instrument (Interviews 6 and 8). The staunchest supporters of shared debt employed the European solidarity frame to claim moral authority, reminding the sceptics that commitments are worthless unless implemented, making the German government and the other ‘frugals’ appear petty, lacking solidarity and isolated.

The open letter and the summit meeting on 26 March are strong indications that normative pressure was being exercised. But did it work? The open letter and its reactions left a stark impression on the Chancellery: ‘A signal to the outside world’ was needed that ‘would be perceived as being legitimate’ (Interview 7, own translation). Suggesting that the government had already lost standing, a senior official emphasised that the government would re‐gain considerable ‘political capital’ (Interview 4, own translation), and thus standing, when it showed its goodwill to its southern neighbours. By mid‐April, the German government noticeably refrained from legitimising its minimalist approach, and itself started to loudly chant the European solidarity tune. Chancellor Merkel came to emphasise the importance of the EU in countering the crisis impact more frequently and decisively. In a session of the German Bundestag on 23 April, she announced that Germany would be willing to pay significantly higher contributions to the next European budget for a limited period ‘in a spirit of solidarity’ (The Federal Government, 2020a). Notably, she followed the line of argumentation penned by ‘the nine’ in their open letter: ‘Europe is not Europe if it does not show solidarity when times are hard through no fault of anyone's’ (The Federal Government, 2020a). While she did not mention the EU even a single time in her televised address to the nation on 18 March, the words ‘Europe’ or ‘European’ were now mentioned a total of 39 times. As poignantly emphasised by Ferrera et al. (Reference Ferrera, Miró and Ronchi2021, p. 1342), German leaders now avoided destructive‐conflictual tones and instead ‘sought the compromise in the name of European solidarity’. While the German government was pivoting towards embracing a joint financial solution, the question about its design and modalities remained unresolved. The German government had joined the European solidarity choir but continued to sing a song against debt mutualisation. How was this schism resolved?

It was arguably the hour of the Commission, which made the right suggestion at the right time (see Smeets & Beach, Reference Smeets and Beach2023). Its resourceful ‘budget wonks’ (Herszenhorn et al., Reference Herszenhorn, Bayer and Momtaz2020) and legal experts (Alexander, Reference Alexander2020) seized the opportunity to link the discussions about the crisis‐related financial stimulus to the ongoing negotiations about the EU's Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF). Within the context of the MFF, the EU could ‘do extraordinary things under the most ordinary circumstances’ (Herszenhorn et al., Reference Herszenhorn, Bayer and Momtaz2020). It was a like finding a ‘trick’ (Alexander, Reference Alexander2020) to unlock the stalemate: Within the framework of the MFF, member states could use time‐tested legislative procedures to raise the EU's own resources‐ceiling and put the Commission in charge to borrow the necessary funds on the financial markets. Moreover, the Commission sought to mobilise Article 122 TFEU as the legal basis for the EU to enact extraordinary measures, and hence as a temporary exception to the no‐bailout clause (Article 125 TFEU) and the prohibition for the EU budget to go into deficit (Articles 310 and 311 TFEU).

Why was this proposal so consequential in order to explain the German government's pivot towards supporting a joint debt instrument? For normative pressure to be effective, it is critical that legitimate counter‐arguments are in short supply. The German government did not dispute that European solidarity was necessary and that it should involve a financial component, however it had now retreated to proceduralism: Rather than fighting grants on substantive grounds, the government repeatedly pointed to the legal impossibility of proposals for shared debt. In the past, the Chancellery has looked at the Commission's ‘creative treaty interpretations’ (Alexander, Reference Alexander2020) with considerable suspicion and this was also the case when discussions about the Commission's plans for a recovery instrument took off. References to legal obstacles were a main line defence from the Chancellery against any form of debt mutualisation. On 20 April, Chancellor Merkel argued that the solidarity clause under Article 122 of the EU treaties could be used to finance other forms of financial assistance for national governments precluding EU debt mutualisation (von der Burchard, Reference von der Burchard2020). But within Merkel's own government, the voices supporting shared European debt grew stronger and ultimately even the legal sceptics, including Merkel's EU politics chief advisor Uwe Corsepius, dropped their reservations (Alexander, Reference Alexander2020; Ziedler, Reference Ziedler2020). What had happened? One reason is that in domestic political circles the legal impossibility‐argument lost traction: It was no longer disputed that a fiscal solidarity instrument could be set‐up legally, based on Article 122 TFEU, which, in turn, would also not violate other treaty obligations, such as the no‐bailout clause of Article 125, or require a treaty change (see, e.g., Grund et al., Reference Grund, Guttenberg and Odendahl2020). Even within Merkel's own parliamentary party, legal concerns appeared assuaged, as long as Coronabonds and treaty revision were off the table (Alexander, Reference Alexander2020; Hoffmann et al., Reference Hoffmann, Hornig, Mayr, Medick, Müller, Sandberg and Zuber2020). Second, with the transition from Wolfgang Schäuble (CDU) to Olaf Scholz (SPD) at the helm of the finance ministry, its political leadership had become a strong advocate of a bold fiscal stimulus package. Among Scholz's top officials, Jörg Kukies and Jacob von Weizsäcker had been influential in designing the domestic ‘Corona‐Bazooka’ and were also strongly advocating for a comparable measure at the EU‐level (Alexander, Reference Alexander2020).

Overall, the German government's legal reservations were no longer a viable counter‐claim to a shared debt instrument. The German government's remaining (legitimate) procedural reservations to exercise fiscal solidarity were thus reduced to the respect of the existing treaties and the temporary nature of putative fiscal‐sharing instruments. While normative pressure was effectively at work, ‘shoving’ the government on the path towards NGEU, it was assisted by internal ‘pushing’: Pressure on the Chancellery to follow up on European solidarity rhetoric came from within the government itself, most notably from the finance ministry (Alexander, Reference Alexander2020).

Discussion and conclusion

Our process‐tracing analysis has shown that as the European solidarity frame became the predominant crisis frame, fiscal burden‐sharing was no longer predicated on deservingness and political conditionality, but amounted to a shared sense of moral duty. In short: Providing fiscal assistance was the appropriate and legitimate thing to do and became the standard of legitimacy guiding the debate about the Corona recovery fund. The German government had now become committed to the European solidarity frame, but its actions did not yet follow suit. It still opposed shared debt as an instrument of EU fiscal integration more generally. We showed that this disjuncture between talk and action became unsustainable, as normative pressure from the other member states – orchestrated by France – mounted, and isolated the German government. To re‐gain standing and political capital, Chancellor Merkel threw herself behind a joint fiscal response. The Franco–German proposal reflects that, eventually, the German Chancellor gave her belated blessing for a shared debt instrument. The proposal broke the impasse and was deemed ‘historic’ (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Fleming and Chazan2020). Germany's Finance Minister Olaf Scholz even claimed that the EU is seeing its ‘Hamiltonian moment’ (Finke Reference Finke2021). The German government thus satisfied the calls for a strong display of European solidarity.

Yet, the initiative also reveals the German government's continued aversion to long‐term fiscal sharing (see Becker, Reference Becker2022: 15): The government has changed its position on shared debt, but not its preference against it. When examining the design of the Franco–German proposal, it becomes apparent that through its linkage to the MFF, the German government sought to explicitly avoid long‐term lock‐in effects. First, the government insisted that the proposed Corona recovery fund would be a temporary instrument to cushion the socio‐economic impact of the Corona crisis. According to Chancellery officials, the fund was a ‘one‐off action in a one‐off or – at any rate – absolutely exceptional constellation’ (Interview 4, own translation) and ‘unique because the situation was unique’ (Interview 7, own translation). Second, the proposal envisaged only a limited form of financial liability. The German government insisted that the negotiations about the recovery fund be linked to the negotiation of the MFF (Interview 9). The result was that member states will have to repay the loans according to their share of the EU budget, thereby limiting the liability of individual countries (see Krotz & Schramm, Reference Krotz and Schramm2022). While calling the design of the recovery fund as a ‘trick’ (Interview 3) pulled off by the German government likely overestimates the latter's political cunningness, our findings lend support to the claim that Germany's policy U‐turn in the Corona pandemic does not signify a larger shift towards deepening European fiscal integration, but will likely remain a temporary U‐turn instead.

Our findings contribute to the theoretical debate on fiscal burden‐sharing in the EU in times of crisis (e.g., Biermann et al., Reference Biermann2019; Carstensen & Schmidt, Reference Carstensen and Schmidt2018; Matthijs & McNamara, Reference Matthijs and McNamara2015; Schimmelfennig, Reference Schimmelfennig2015). First, they highlight the paucity of monocausal explanations for burden‐sharing in times of crisis. Both material factors (avoiding enormous economic costs due to negative interdependence) and non‐material factors and mechanisms (adhering to the normative expectations raised by crisis framing) are needed to fully explain the German change in position on the EU recovery fund. Thereby our argument differs from existing explanations by showing how material and ideational factors complement each other rather than assuming that crisis perceptions causally precede material considerations (Crespy & Schramm, Reference Crespy and Schramm2021) or ignoring ideational considerations altogether (Schramm, Reference Schramm2023). Furthermore, by comparing the Corona crisis to the Euro crisis, we were able to identify conditions under which perceptions and frames influence member state preferences. During the Euro crisis, framing contests remained unresolved, which enabled governments to stick to their distributive preferences. By contrast, during the Corona crisis, a dominant European solidarity frame emerged, which empowered actors whose preferences were aligned with the dominant crisis framing and standard of legitimacy, and constrained those actors – including the German government – whose preferences were at odds with the dominant European solidarity frame. In addition, we were able to show that framing success crucially depends on the nature of the crisis itself, that is, whether its origins are perceived to be endogenous or exogenous. This finding has implications for how we study the ‘politics of crises’ in the EU. For instance, the ‘energy crisis’, which had become a prospect in the context of Russia's war of aggression against Ukraine, has not led to an outpouring of expressions of European solidarity with states whose energy supply was heavily dependent on Russia. Similar to the Corona crisis, the energy crisis is the result of an exogenous shock (the Russian invasion of Ukraine) with asymmetric consequences. However, unlike in the pandemic, those states that are most affected by the crisis – such as Austria, Germany and Hungary – have been previously criticised for their risky gas strategy because of their energy dependence on Russia. Thus, they can be blamed for their own shortcomings and are unlikely to count on successfully activating the European solidarity frame. Furthermore, Germany has sufficient resources to mobilise, unlike Italy or Spain during the Corona pandemic. The national responsibility frame will likely be more ‘successful’ in a looming energy crisis. Comparing the framing contests that unfold in different transboundary crises provides an exciting avenue for future research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Previous versions of this paper were presented at the EUSA 17th Biennial Conference 2022 in Miami (USA) and at the International Relations research colloquium at LMU Munich. Special thanks go to Johannes Lindner, Alasdair Young, Stephan Weltzer and the reviewers for their detailed and encouraging feedback. We also wish to thank the journal editors for their support.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

List of interviews

Interview 1 (2021), German Bundestag, MP, via Zoom, 20 May.

Interview 2 (2021), German Bundestag, party group offical, via Zoom, 25 May.

Interview 3 (2021), European Parliament, assistant to MEP, via Zoom, 26 May.

Interview 4 (2021), German Federal Chancellery, senior official, via phone, 28 May.

Interview 5 (2021), German Finance Ministry, senior official, via Zoom, 1 June.

Interview 6 (2021), European Commission, member of cabinet, via WebEx, 14 June.

Interview 7 (2021), German Federal Chancellery, senior official, via WebEx, 15 June.

Interview 8 (2021), Representative of the Ifo Institute for Economic Research, via Zoom, 16 June.

Interview 9 (2021), European Commission, official, via WebEx, 28 June.