The mental health status of university students has been discussed over many years. Reference Mahdavinoor, Rafiei and Mahdavinoor1–Reference Mahdavinoor, Moghimi, Mollaei, Teimouri, Abedi Yarandi and Loveneh Nasab6 Admission to university brings about changes in individual, family and social life and is therefore regarded as a highly sensitive phase. Reference Mahdavinoor, Rafiei and Mahdavinoor1 The pressures imposed on students and their difficult circumstances make their mental health more vulnerable than that of the general population. Reference Naser, Dahmash, Al‐Rousan, Alwafi, Alrawashdeh and Ghoul7,Reference Arsandaux, Montagni, Macalli, Texier, Pouriel and Germain8 This increased vulnerability to mental disorders among students can lead to a wide range of adverse outcomes, including suicide. In fact, students are at greater risk of suicidal than the non-student population, Reference Lageborn, Ljung, Vaez and Dahlin9 so that approximately one of every four students worldwide has experienced suicidal ideation in some way. Reference Mortier, Cuijpers, Kiekens, Auerbach, Demyttenaere and Green10 Suicide is also a major public health concern in low- and middle-income countries: according to a World Health Organization report, 77% of all suicides occur in these countries. 11 Poor screening, absence of comprehensive suicide prevention systems, lack of government investment in people’s mental health, class differences, poverty, social crises and so forth are probably among the contributory factors. Reference Yaghubi, Soleimani, Abedi Yarandi, Mollaei and Mahdavinoor4 The key issue about suicide is its effect on society. It has been reported that every successful suicide puts 135 more people at risk of suicide. Reference Cerel, Brown, Maple, Singleton, van de Venne and Moore12 This means that suicide does not increase in an arithmetical progression, but rather in a geometric progression. Despite the fact that suicide occurs more frequently in low- and middle-income countries, accurate information concerning its prevalence and associated factors is usually not available depending to the conditions of those countries. For example, there are limited and contradictory data with respect to the frequency of suicide in Iran. Reference Hassanian-Moghaddam and Zamani13 This lack of information complicates practical planning for the prevention of suicide.

In Iran, several studies have measured the prevalence of suicidal ideation and attempts among university students. Niusheh Soofi et al estimated the prevalence of suicidal ideation at 6% in students from Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences. Reference Niusheh Soofi, Marziye, Parvin and Mohsen14 In another study at Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Nakhostin-Ansari et al approximated the prevalence of suicidal ideation among students to be 32%. Reference Nakhostin-Ansari, Akhlaghi, Etesam, Sadeghian and Pavon15 Rohani and Esmaeili also found that 20% of students at the University of Isfahan had experienced suicidal ideation. Reference Rohani and Esmaeili16 Differing prevalence rates of suicide attempts have also been reported among Iranian students. For example, Poorolajal et al Reference Poorolajal, Mohammadi, Soltanian and Ahmadpoor17 estimated the prevalence of suicide attempts among students at 13 universities of medical sciences in Iran to be 1.7%. In addition, another study at Ardabil University of Medical Sciences found that this rate was 7.9%. Reference Narimani, Khezeli, Babaei, Rezapour, Habibi and Rohallahzadeh18

Student suicide in low- and middle-income countries appears to be a highly important matter given its high prevalence in these countries, in addition to the effect of each person’s suicide on other people and the high costs imposed on society. Despite the importance of suicide among students, to our knowledge there has been no systematic review of studies reporting the prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among Iranian university students. Therefore, our goal was to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis focusing on the prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among this group. Our research can provide a comprehensive view of suicide among Iranian students.

Method

Study design

We developed and conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis in line with two methodological guides: the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Reference Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li and Page19 and a step-by-step guide for conducting systematic reviews and meta-analyses with simulation data. Reference Tawfik, Dila, Mohamed, Tam, Kien and Ahmed20 We also reported this review according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guideline. Reference Page, Moher, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann and Mulrow21 The protocol of this research has been registered with the International Registration of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under the following registration number: CRD42023471340. Our review question was developed based on the CoCoPop Reference Munn, Moola, Lisy, Riitano and Tufanaru22 framework, where ‘Condition’ refers to suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, ‘Context’ to studies conducted in Iran and ‘Population’ to university students.

Search strategy for detection of relevant studies

We performed both manual and electronic searching and carried out a systematic search of several international databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus and PsycINFO, up to 3 September 2023. Following that, we updated the search up to 20 February 2025. Data were extracted starting on 5 November 2023, and updated data extraction began on 20 February 2025. We also used Magiran to find Persian papers. Our search strategy included the following keywords and Medical Subject Heading terms: Suicid* AND Iran* AND student*. Persian synonymous words were used to search the national database. Each database was searched with no restrictions on publication year or language. The full search syntaxes and number of records retrieved from each database are provided in the supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2025.10921. We manually checked the reference lists of all included studies to identify any other eligible studies that may have been missed by our literature searches.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The included studies were as follows: (a) all types of observational studies and (b) all epidemiological studies examining the occurrence of suicide attempts and suicidal ideation among Iranian university students. Studies with the following criteria were excluded: (a) animal studies, conference abstracts, comments, clinical trials, case reports, letters, any type of review, in vitro studies and case series; (b) duplicate publications; (c) qualitative investigations; (d) studies assessing the validity and reliability of questionnaires; and (e) studies that did not contain sufficient data to calculate the required parameters.

Assessment of risk of bias (quality)

Two authors independently evaluated the quality of each study using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) checklist. NOS scoring ranges from 0 (lowest quality) to 10 (highest quality) and assesses studies in terms of group selection, group comparability and determination of the desired outcome. Considering that all studies were cross-sectional, we used the modified version of NOS. Reference Modesti, Reboldi, Cappuccio, Agyemang, Remuzzi and Rapi23 Because NOS has no standardised cut-offs, and arbitrary thresholds may vary across reviews, we reported individual NOS scores for each study descriptively rather than applying fixed categories. Disagreements were resolved through consensus and, if needed, were determined by another author.

Screening and data extraction

One reviewer checked the titles and abstracts of the identified studies, then two reviewers independently assessed the full texts against the predefined eligibility criteria. Two other reviewers extracted the data independently; at each stage, differences between the two reviewers were resolved through consensus. If the disagreement between the authors was not resolved by consensus, another author as a third person made the final decision. The data extraction checklist involved the name of the first author, publication year, location of study, sample size, sampling method, mean age, percentage of suicide attempts and suicidal ideation.

Data synthesis strategy

We analysed the data according to the guideline on conducting proportional meta-analyses across different types of systematic reviews, Reference Barker, Migliavaca, Stein, Colpani, Falavigna and Aromataris24 as well as the methodological guideline for performing meta-analysis of binomial data with Stata. Reference Nyaga, Arbyn and Aerts25 We analysed the data using Stata/MP version 16.0 for Windows (StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas, USA). In this research, we extracted the prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts with 95% confidence intervals; when prevalences were not reported in the original studies, we calculated these based on the available data. Heterogeneity among studies was calculated using the I 2 statistic and Cochran’s Q-test. Because we anticipated that the true prevalence could plausibly vary across studies (for example, due to differences in populations, settings and assessment instruments), we chose to use a random-effects model and pooled proportions with Stata’s metaprop command (Freeman–Tukey double-arcsine transformation). Reference Nyaga, Arbyn and Aerts25 We also used meta-regression to explore potential sources of heterogeneity. We fitted random-effects, multivariable, meta-regression models, entering publication year, study quality (NOS score), total sample size and male:female ratio as predictors. After conducting meta-regression analyses, we produced bubble plots for each statistically significant moderator to visualise the relationship between effect size and moderator; these plots are provided in Supplementary Figs 1–3. To assess robustness, a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was carried out, systematically removing one study at a time and recalculating the overall prevalence to evaluate the influence of each individual study on the final results.

Results

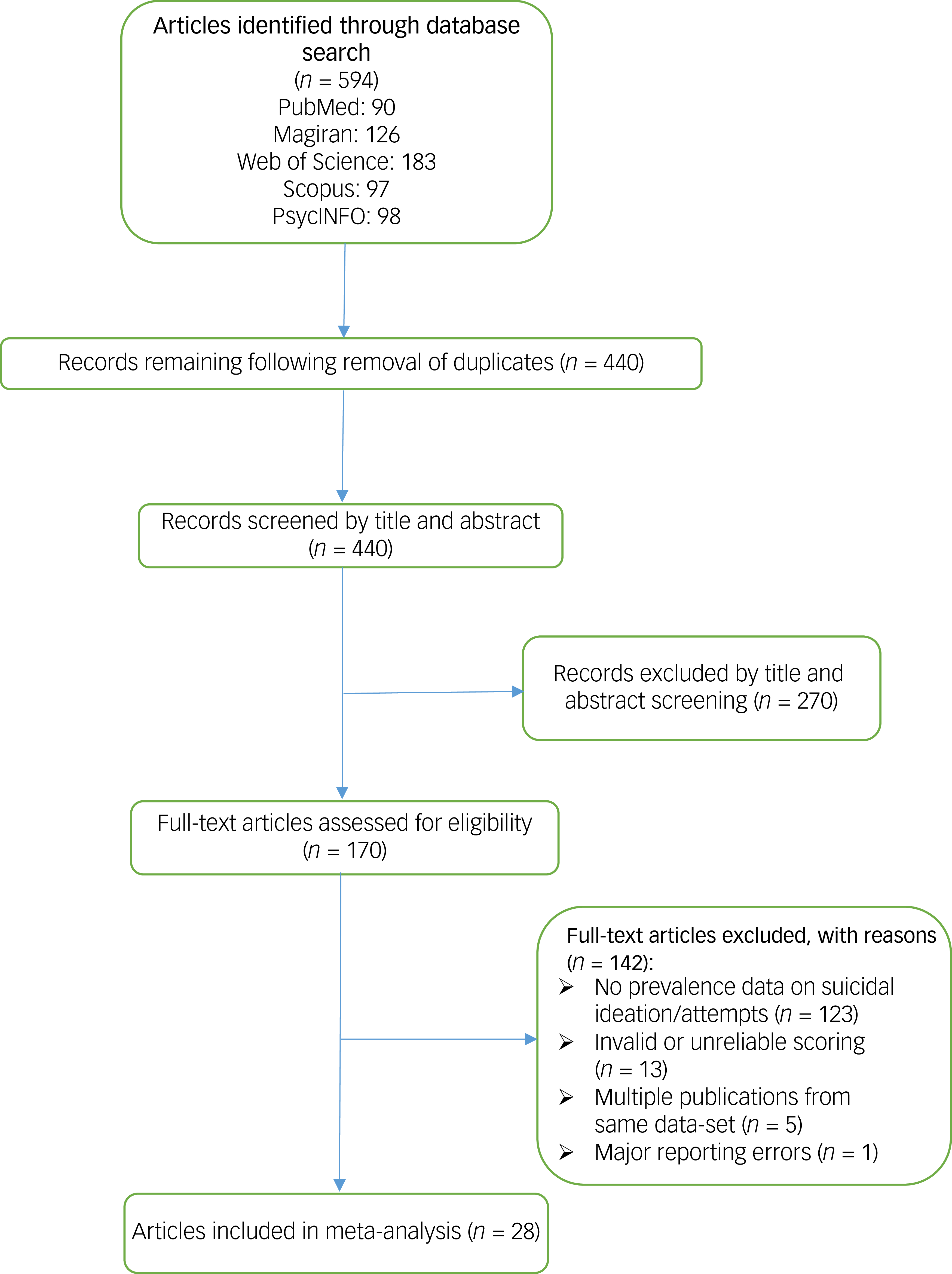

Literature search

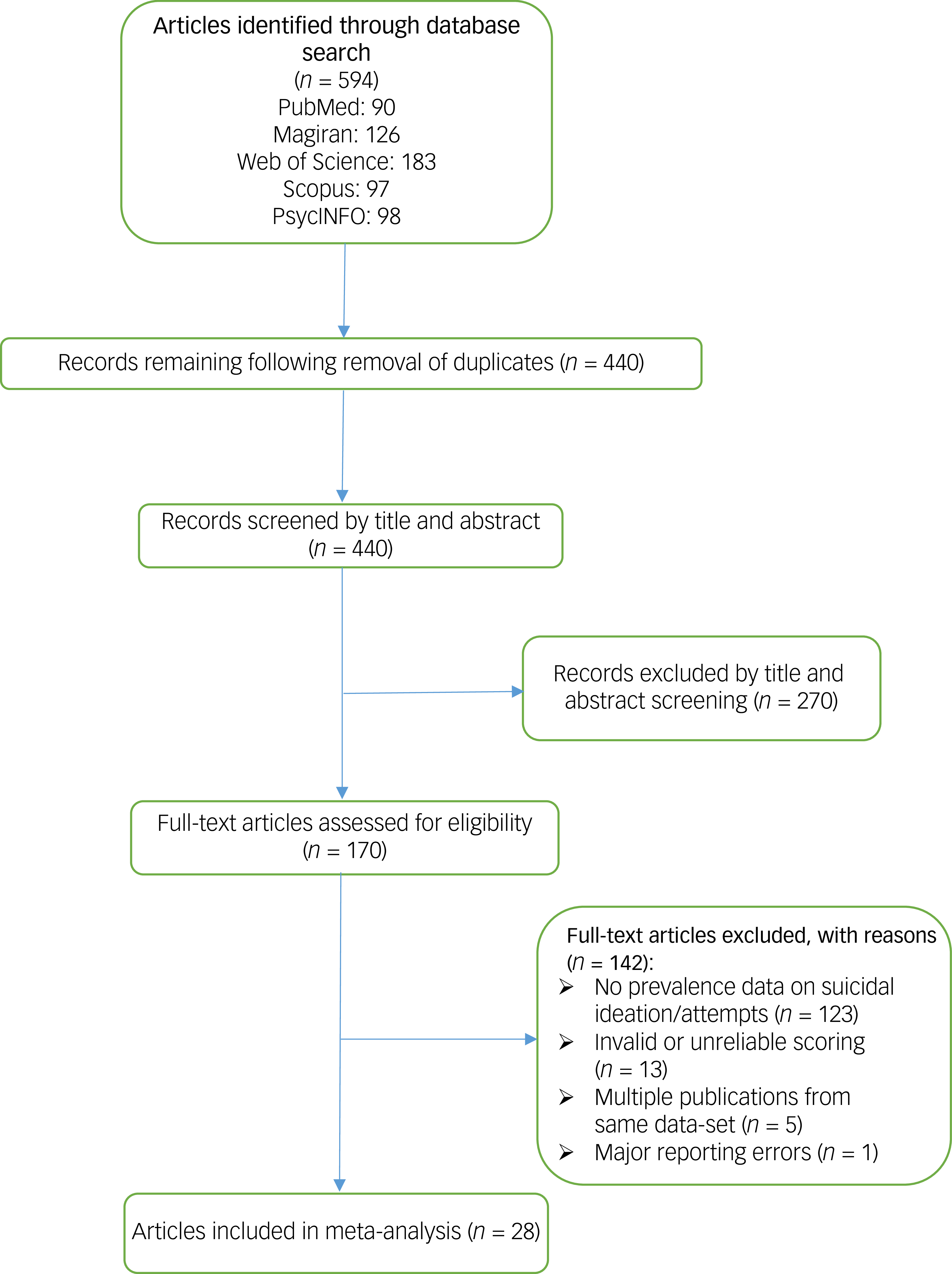

A total of 440 studies were identified after searching different databases and removing duplicates. A total of 170 articles were selected for full-text review. After the full texts were separately checked by the two reviewers, 141 studies were excluded because of not meeting the inclusion criteria. We also excluded one article due to substantial errors in reporting the results. Reference Taban, Vosoghi, Nooraeen, Nojomi, Mesbah and Malakouti26 The process of searching and eliminating those studies that did not satisfy the inclusion criteria is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart for the study selection process.

Study characteristics

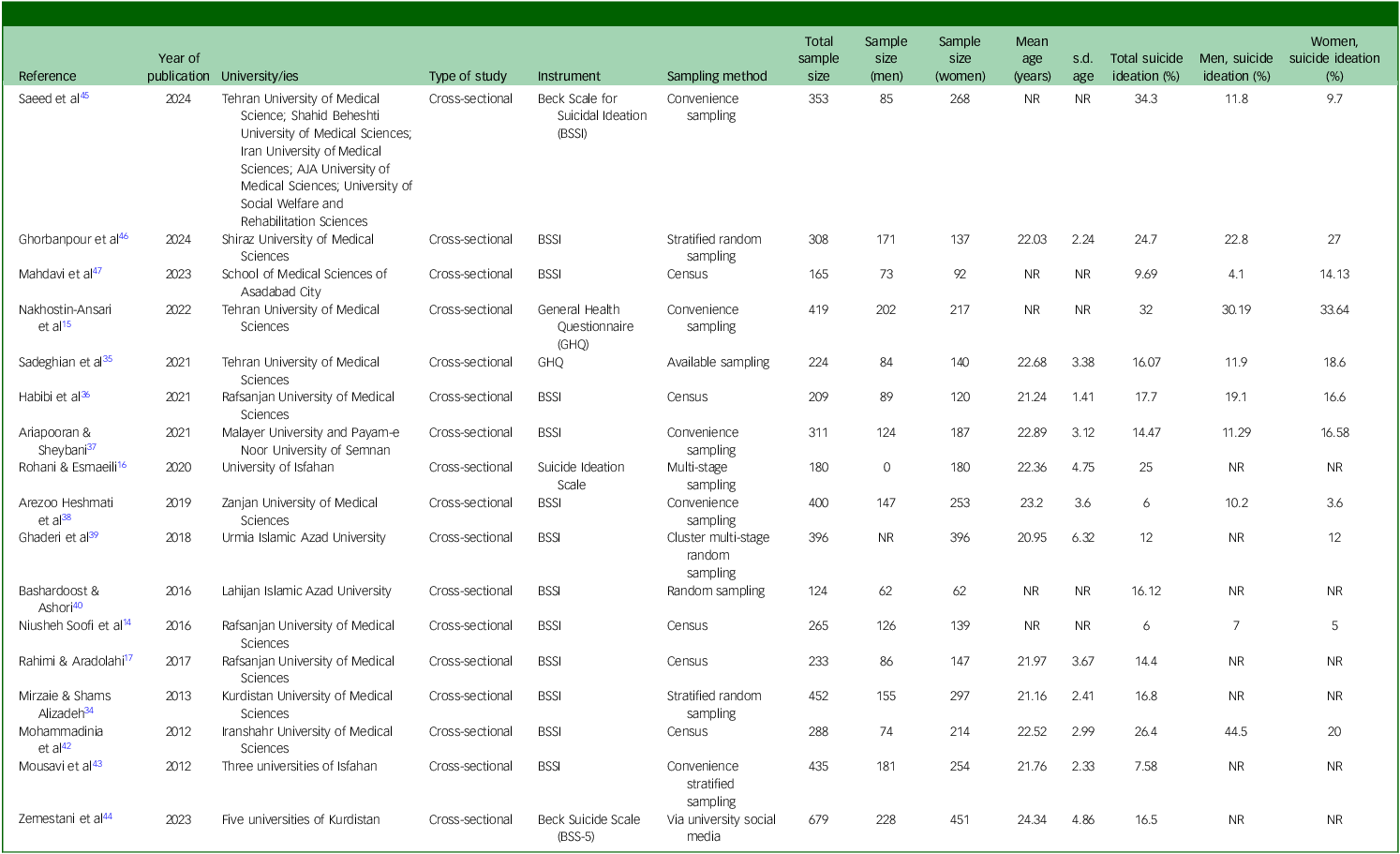

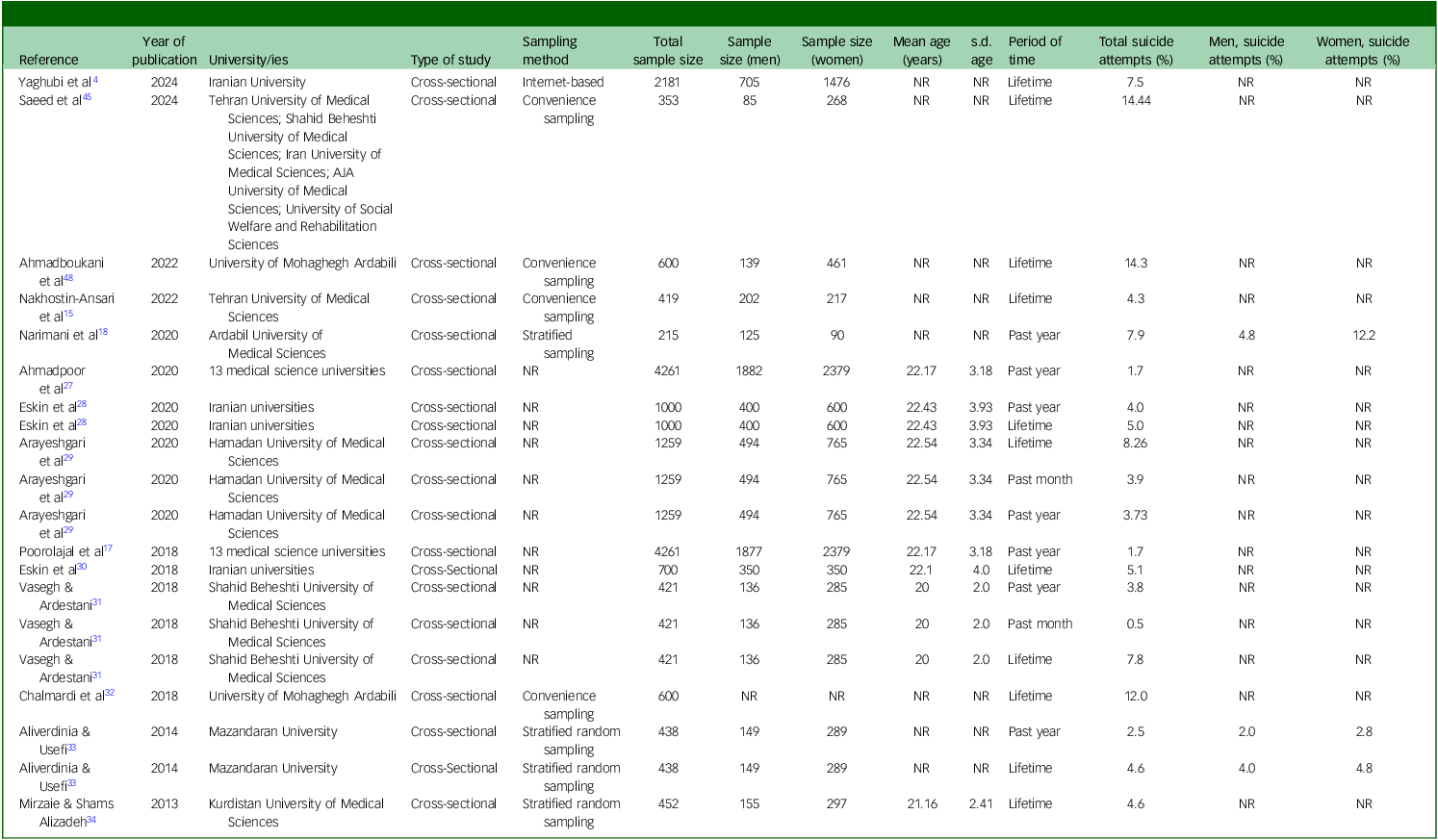

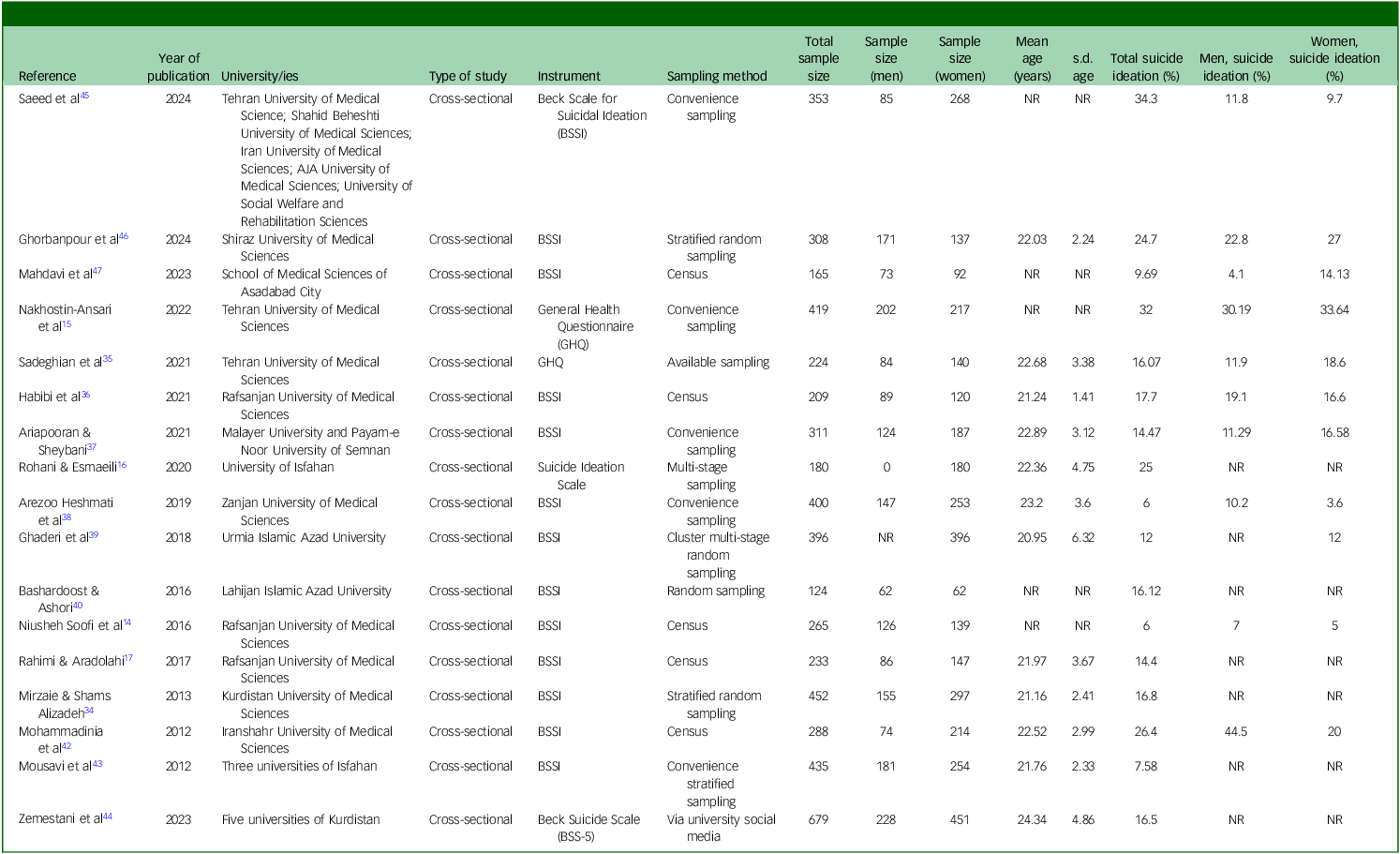

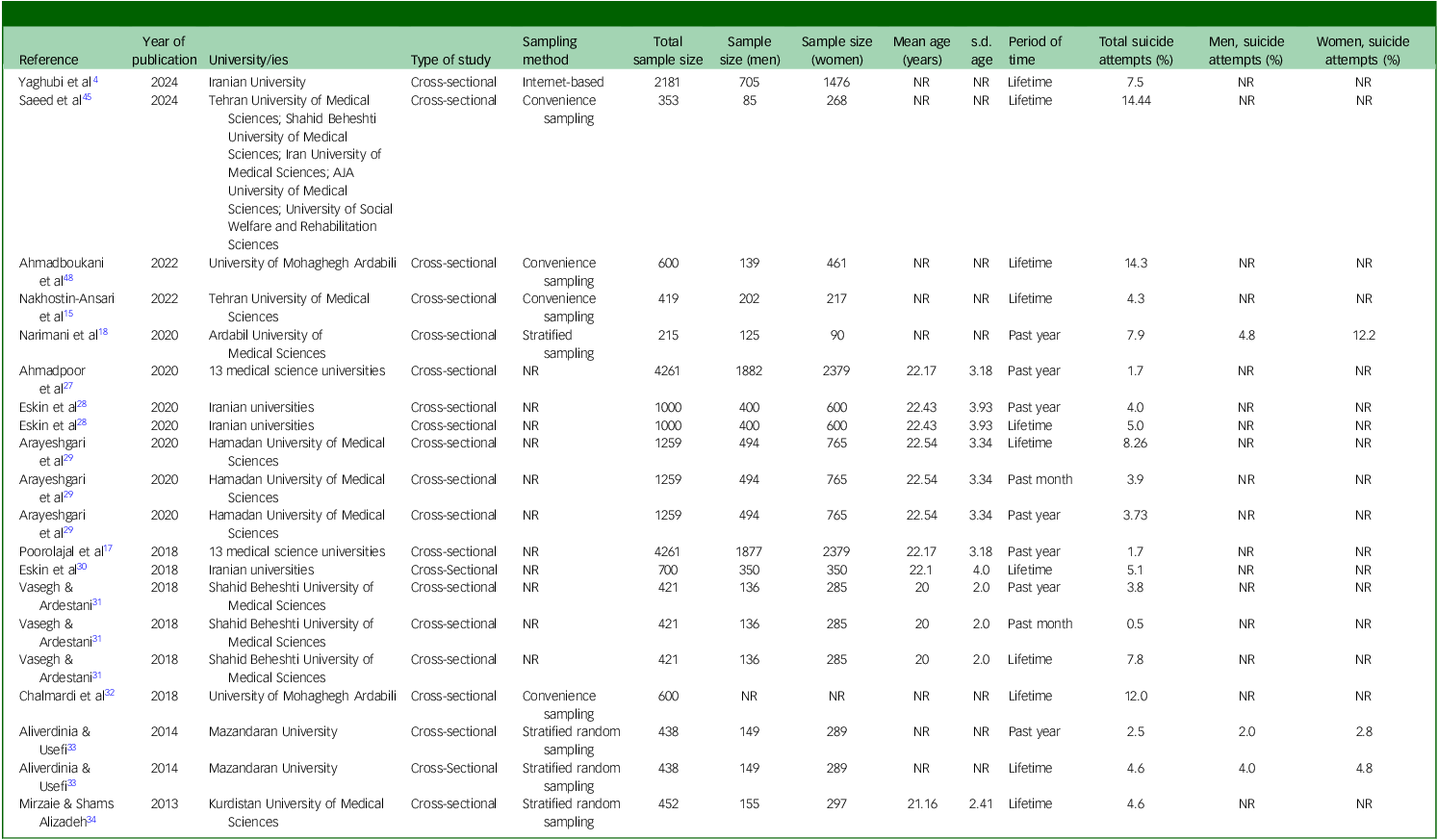

Finally, 28 articles Reference Yaghubi, Soleimani, Abedi Yarandi, Mollaei and Mahdavinoor4,Reference Niusheh Soofi, Marziye, Parvin and Mohsen14–Reference Narimani, Khezeli, Babaei, Rezapour, Habibi and Rohallahzadeh18,Reference Ahmadpoor, Mohammadi, Soltanian and Poorolajal27–Reference Ahmadboukani, Dargahi and Toosi48 were included in the study. A total of 14 articles included information on suicide attempts Reference Yaghubi, Soleimani, Abedi Yarandi, Mollaei and Mahdavinoor4,Reference Nakhostin-Ansari, Akhlaghi, Etesam, Sadeghian and Pavon15,Reference Poorolajal, Mohammadi, Soltanian and Ahmadpoor17,Reference Narimani, Khezeli, Babaei, Rezapour, Habibi and Rohallahzadeh18,Reference Ahmadpoor, Mohammadi, Soltanian and Poorolajal27–Reference Mirzaie and Alizadeh34,Reference Saeed, Ghalehnovi, Saeidi, Ali beigi, Vahedi and Shalbafan45,Reference Ahmadboukani, Dargahi and Toosi48 and 17 included information regarding suicidal ideation. Reference Niusheh Soofi, Marziye, Parvin and Mohsen14–Reference Rohani and Esmaeili16,Reference Mirzaie and Alizadeh34–Reference Mahdavi, Darabi and Ahmadinia47 Among the 17 articles that assessed the prevalence of suicidal ideation, all but 3 used BSSI. In other words, according to our results, this instrument – despite its age – was the one most commonly used for assessment of suicidal ideation in Iran. Sample sizes ranged from 124 to 2181 participants. Sampling methods varied (e.g. cluster multi-stage random sampling, census and convenience sampling); however, some studies did not report their sampling method. Although we applied no restrictions on publication year, the earliest included study was published in 2013. The data extraction process is shown in Tables 1 and 2. In addition, studies were conducted in different cities of Iran.

Table 1 Data extraction file for prevalence of suicide ideation

NR, not reported.

Table 2 Data extraction file for prevalence of suicide attempts

NR, not reported.

Methodological quality

The methodological quality of the included studies varied; although some studies scored highly on NOS, several others had notable limitations. In particular, some studies did not receive a star in the statistical test domain because confidence intervals were not reported. A number of studies also provided no description of response rates, nor the characteristics of respondents versus non-respondents. Additionally, some studies did not stratify or adjust for key confounders such as gender or age, resulting in lower scores in the comparability domain. These issues may have affected the accuracy of prevalence estimates and contributed to heterogeneity. The quality ratings of each article are presented in full in the supplementary material.

Prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts

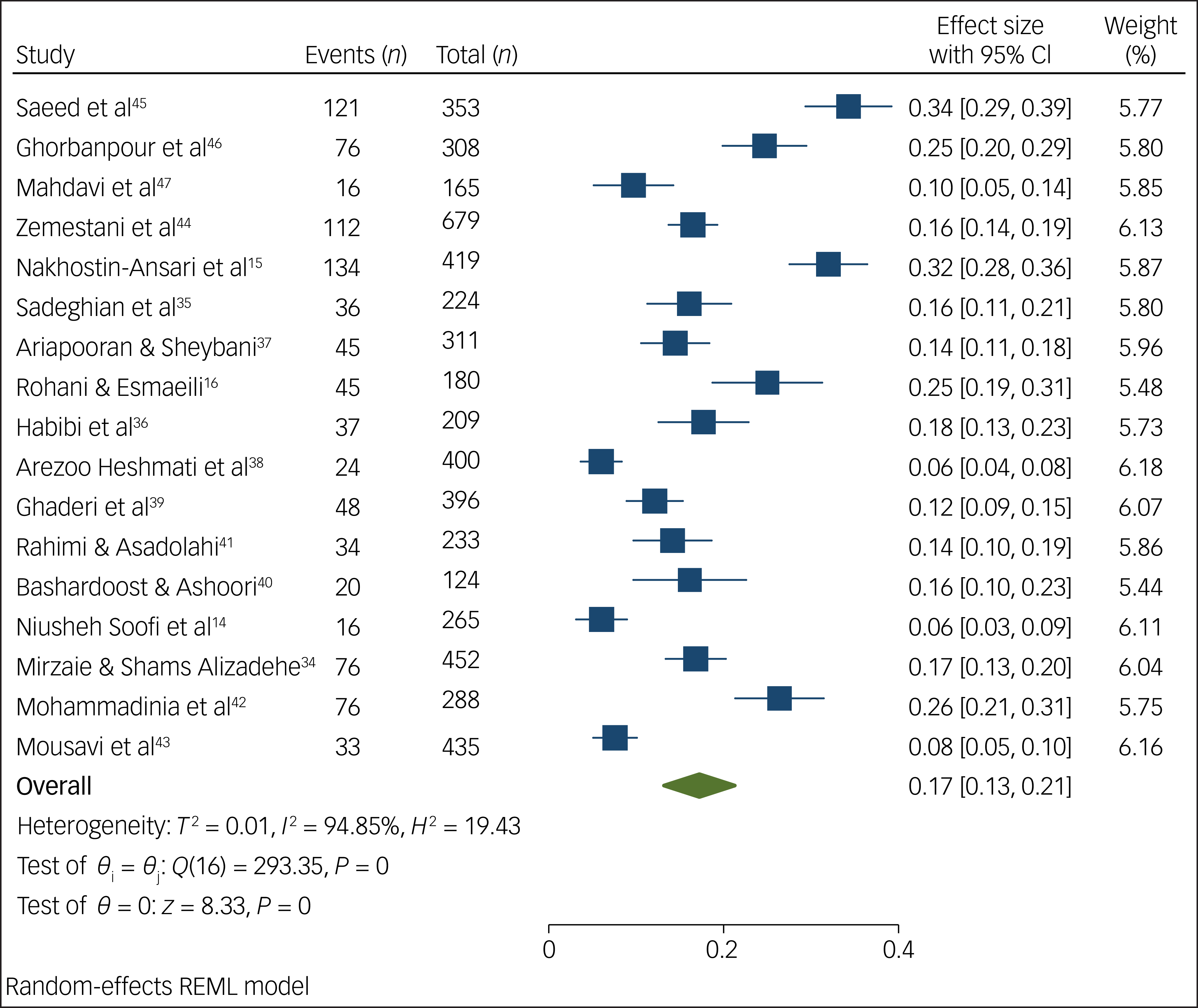

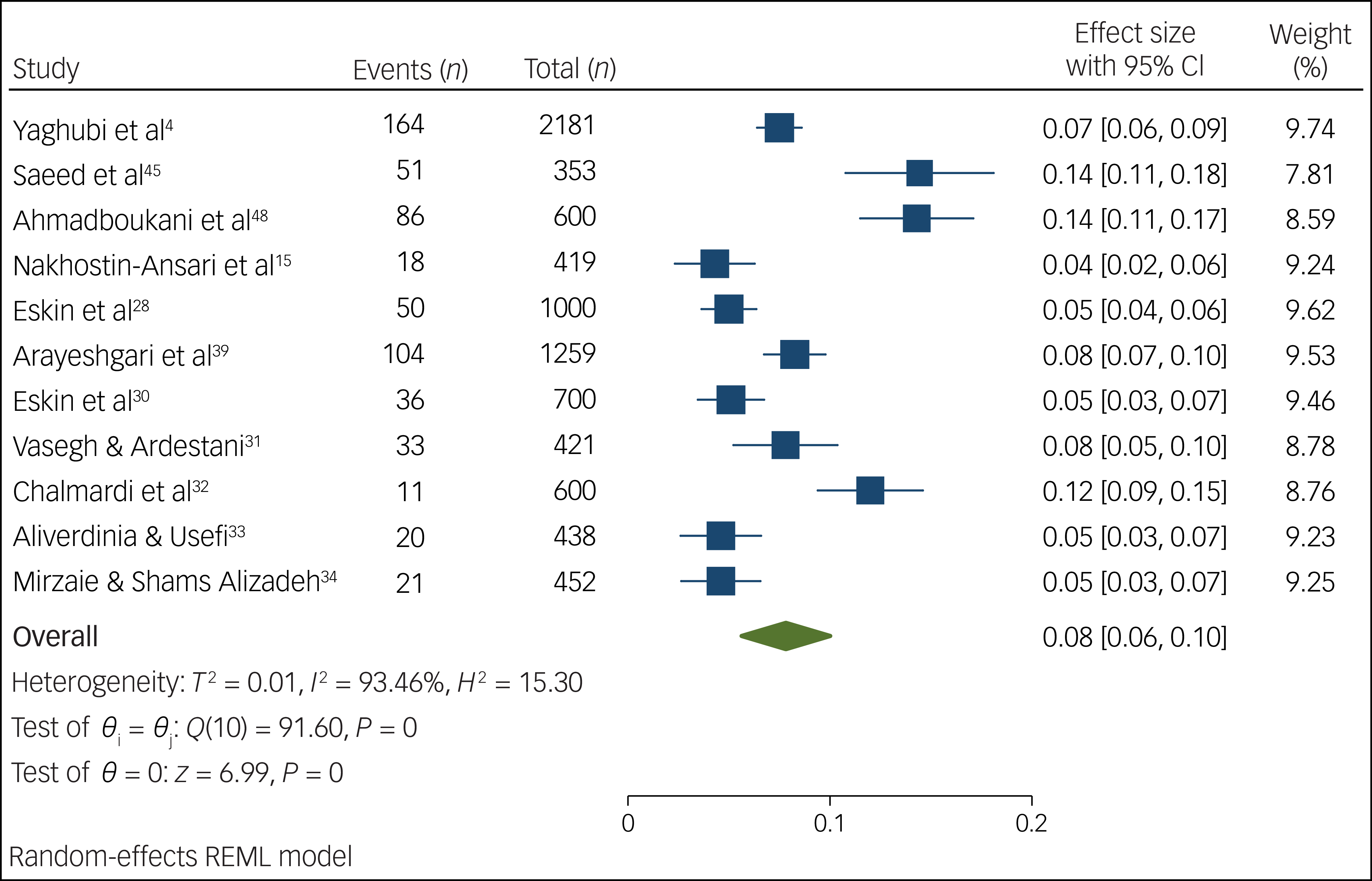

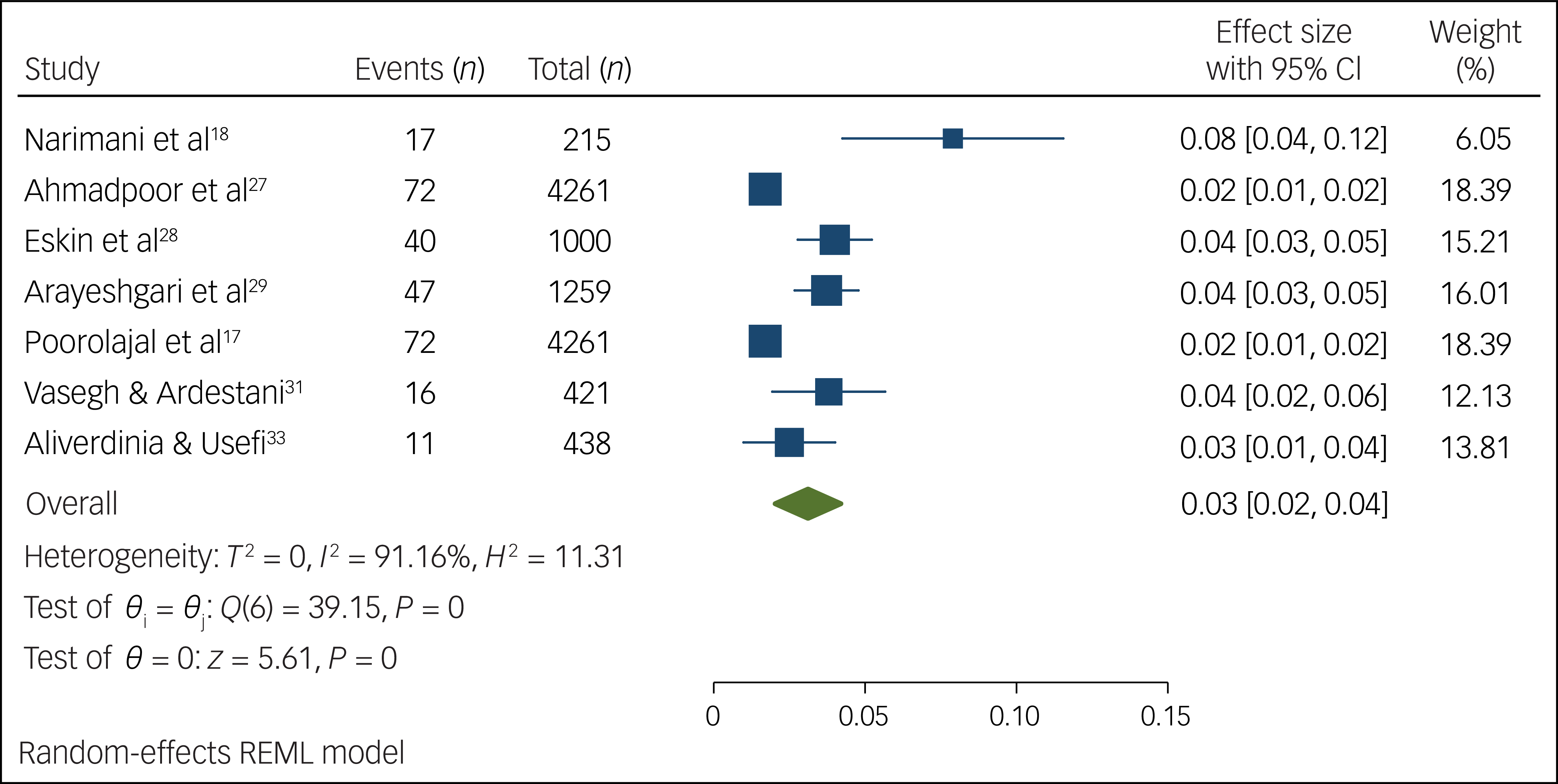

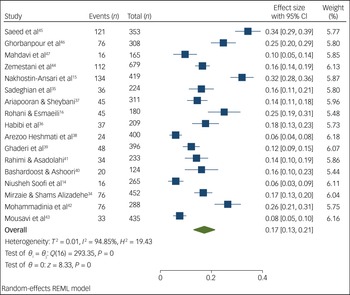

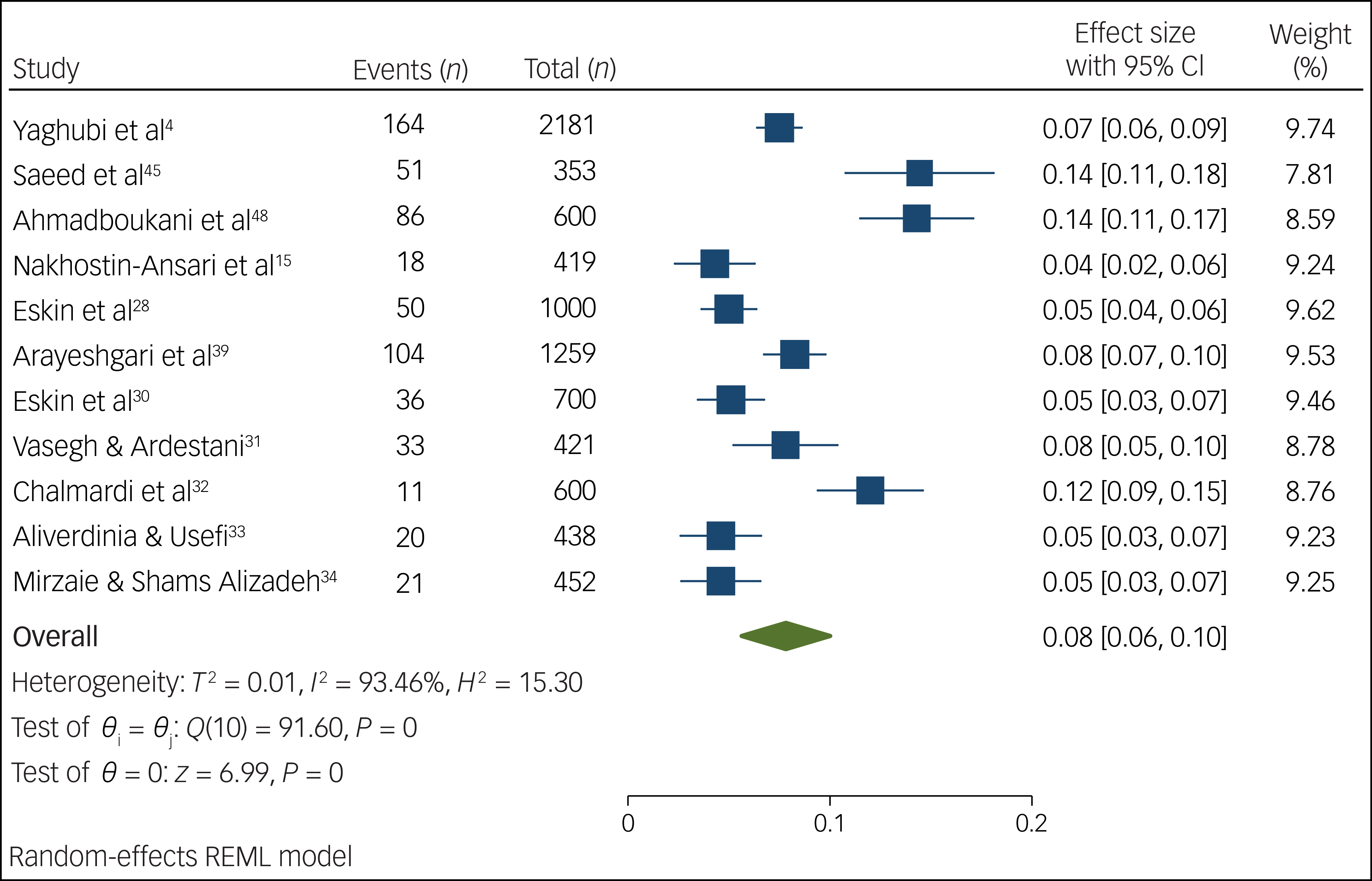

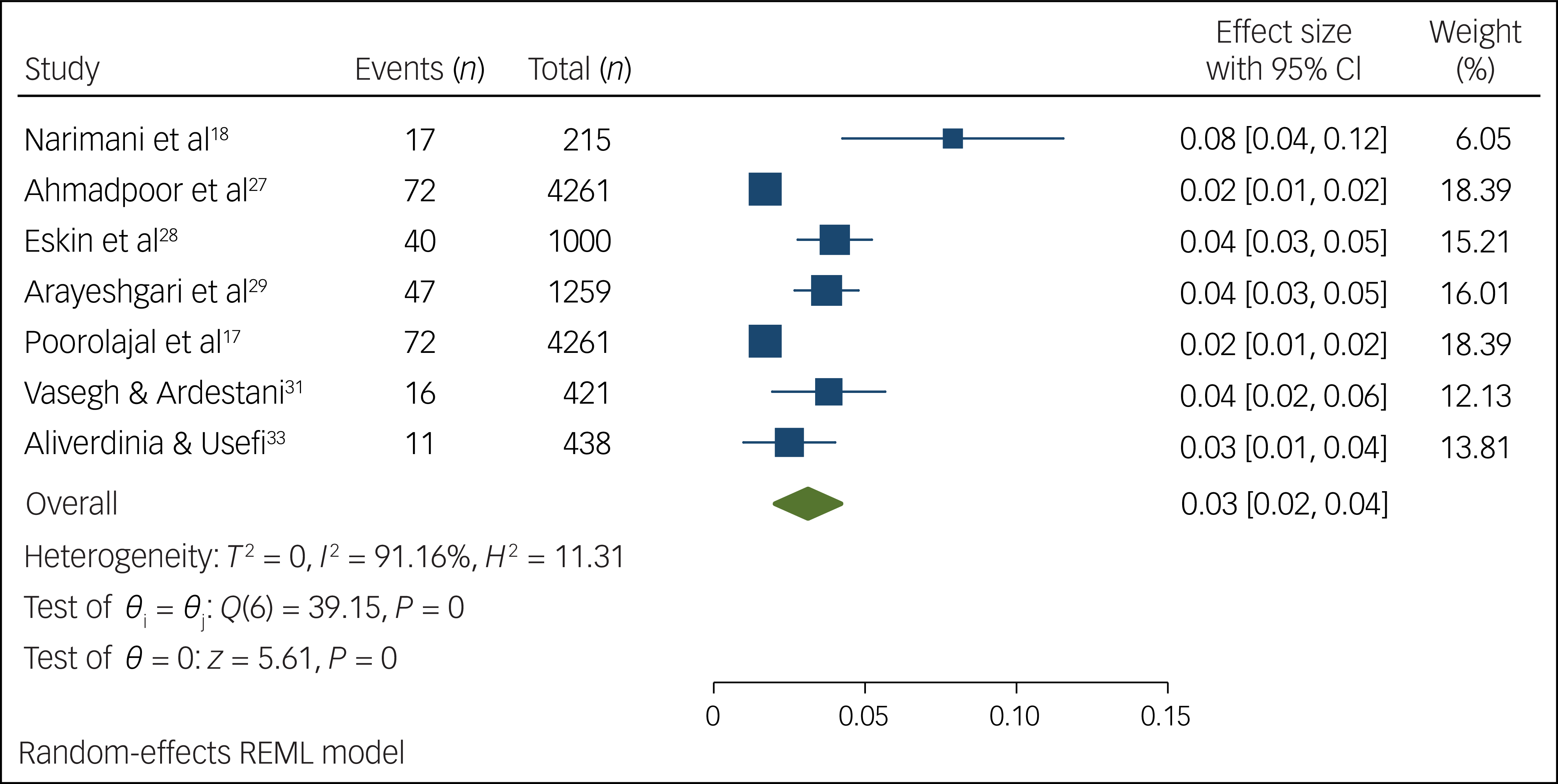

The meta-analysis performed on the occurrence of suicidal ideation among Iranian students (Fig. 2) included 17 articles published between 2012 and 2024. Study heterogeneity was strong (I 2 = 94.85%, P < 0.01). Results from the forest plot indicated 17% pooled suicidal ideation among Iranian students, with a 95% CI of 13–21%. Similarly, the meta-analysis on suicide attempts among Iranian students (Figs 3 and 4) comprised 14 articles published between 2013 and 2024. We performed a meta-analysis of the prevalence of suicide attempts, both lifetime and for the past year, thereby obtaining the lifelong prevalence of suicide attempts as 8% with a 95% CI of 6–10%; we also obtained the pooled prevalence rate of suicide attempts in the past year at 3%, with a 95% CI of 2–4%. Again, study heterogeneity was strong for both lifelong prevalence (I 2 = 93.46%, P < 0.01) and past-year prevalence (I 2 = 91.16%, P < 0.01). Given the substantial heterogeneity in the meta-analyses of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, we conducted sensitivity analyses and meta-regression, the outcomes of which will now be elaborated upon.

Fig. 2 Prevalence of suicidal ideation among Iranian students. REML, restricted maximum likelihood.

Fig. 3 Prevalence of lifetime suicide attempts among Iranian students. REML, restricted maximum likelihood.

Fig. 4 Prevalence of past-year suicide attempts among Iranian students. REML, restricted maximum likelihood.

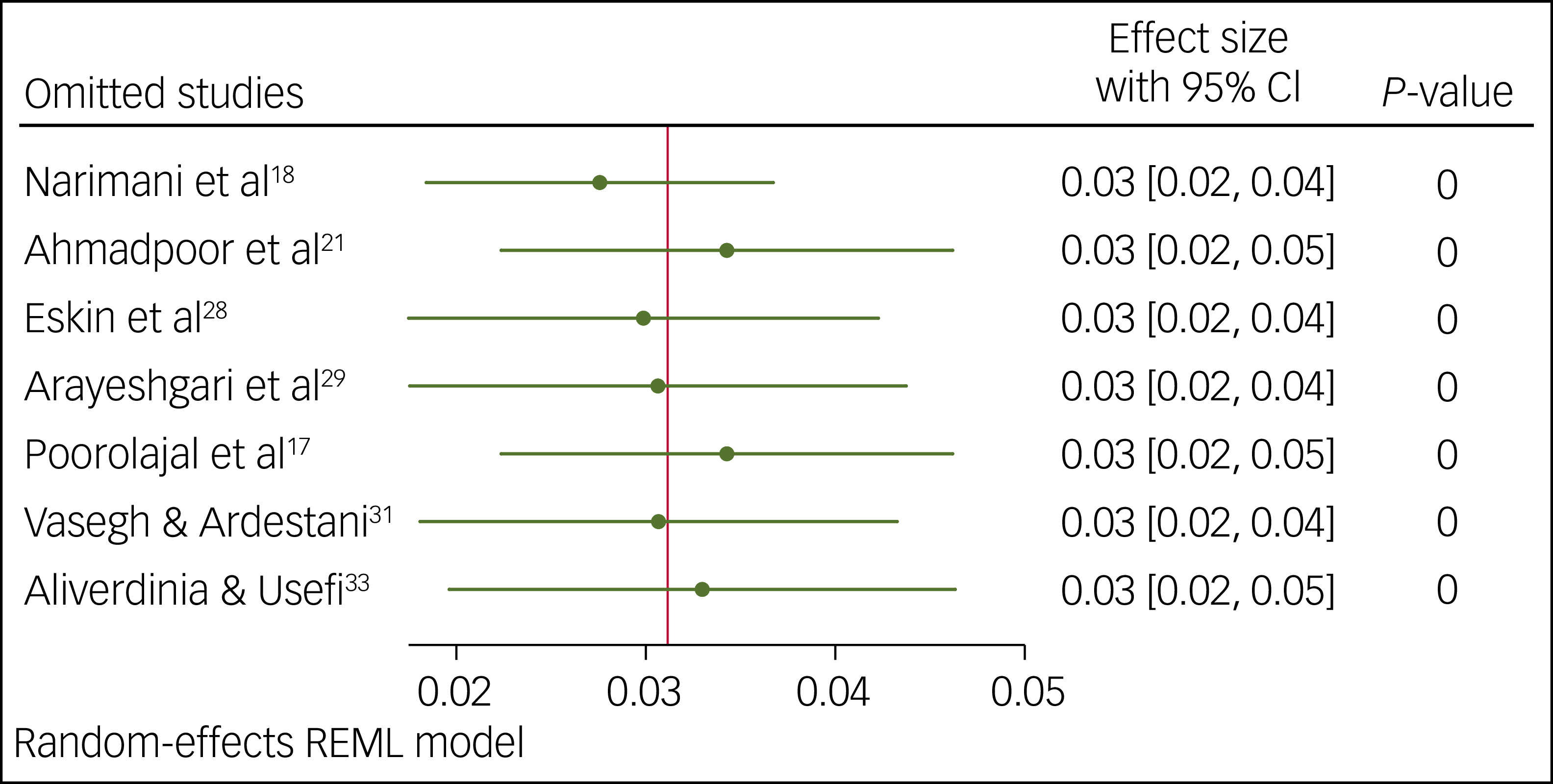

Sensitivity analysis

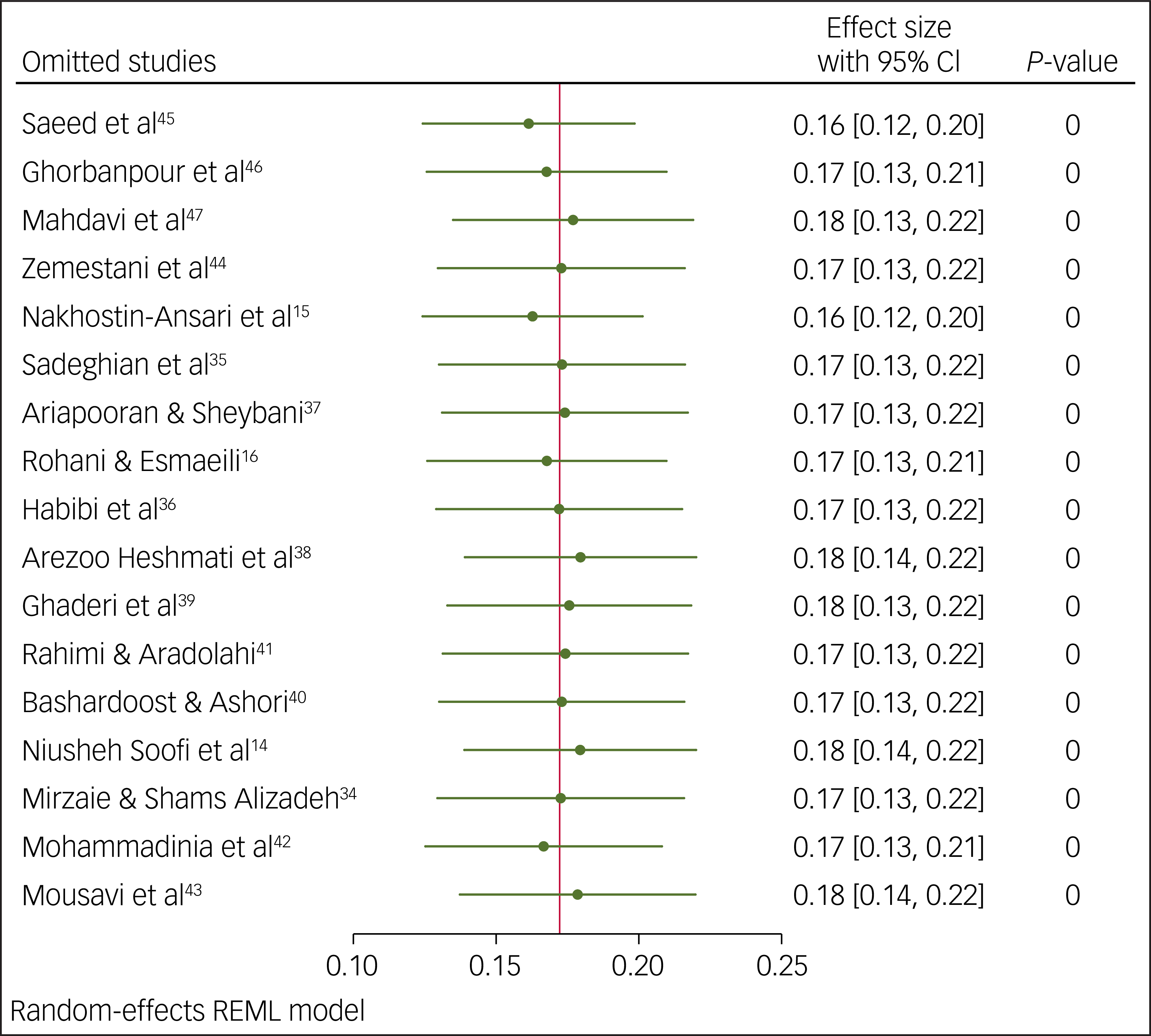

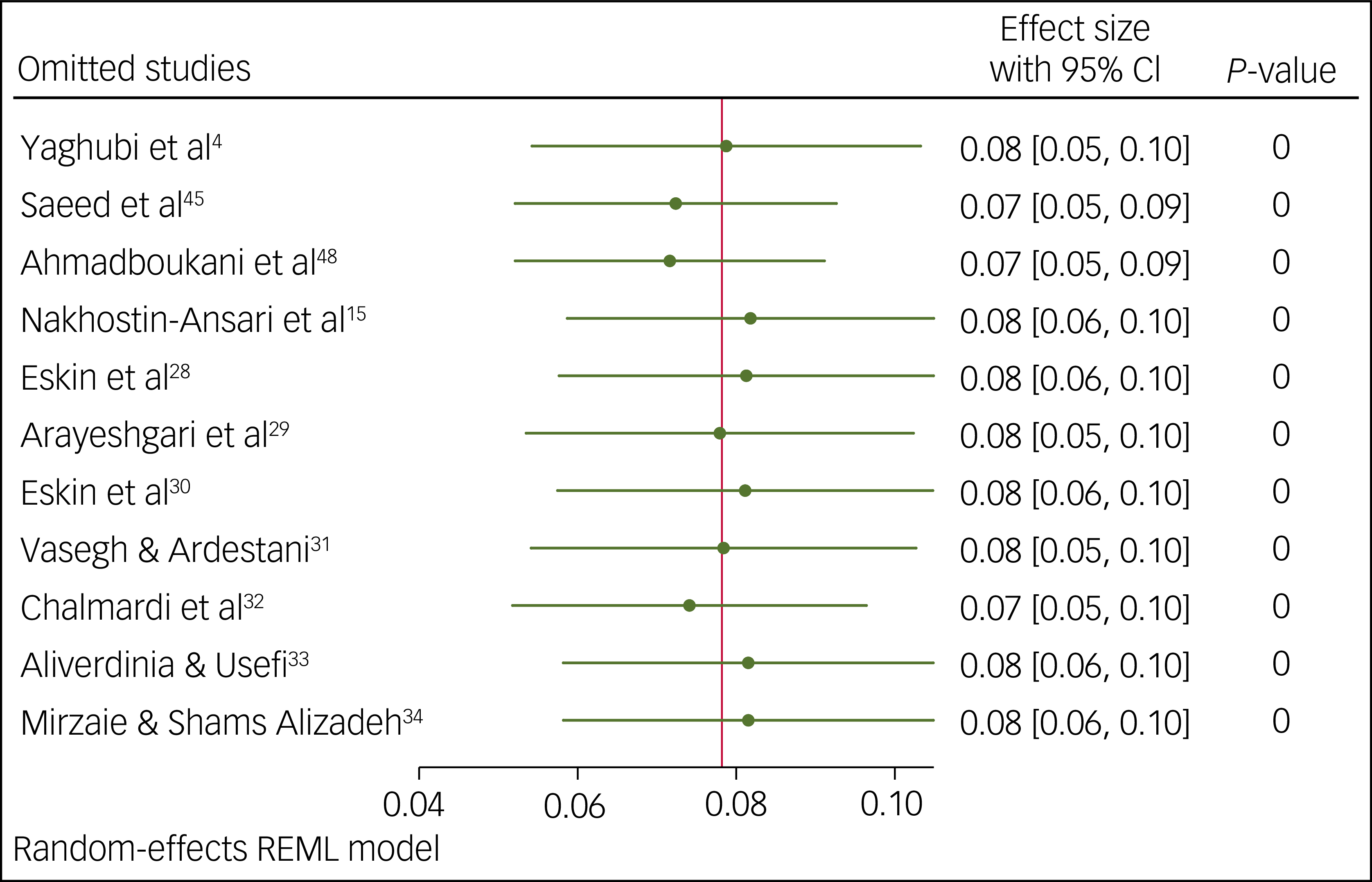

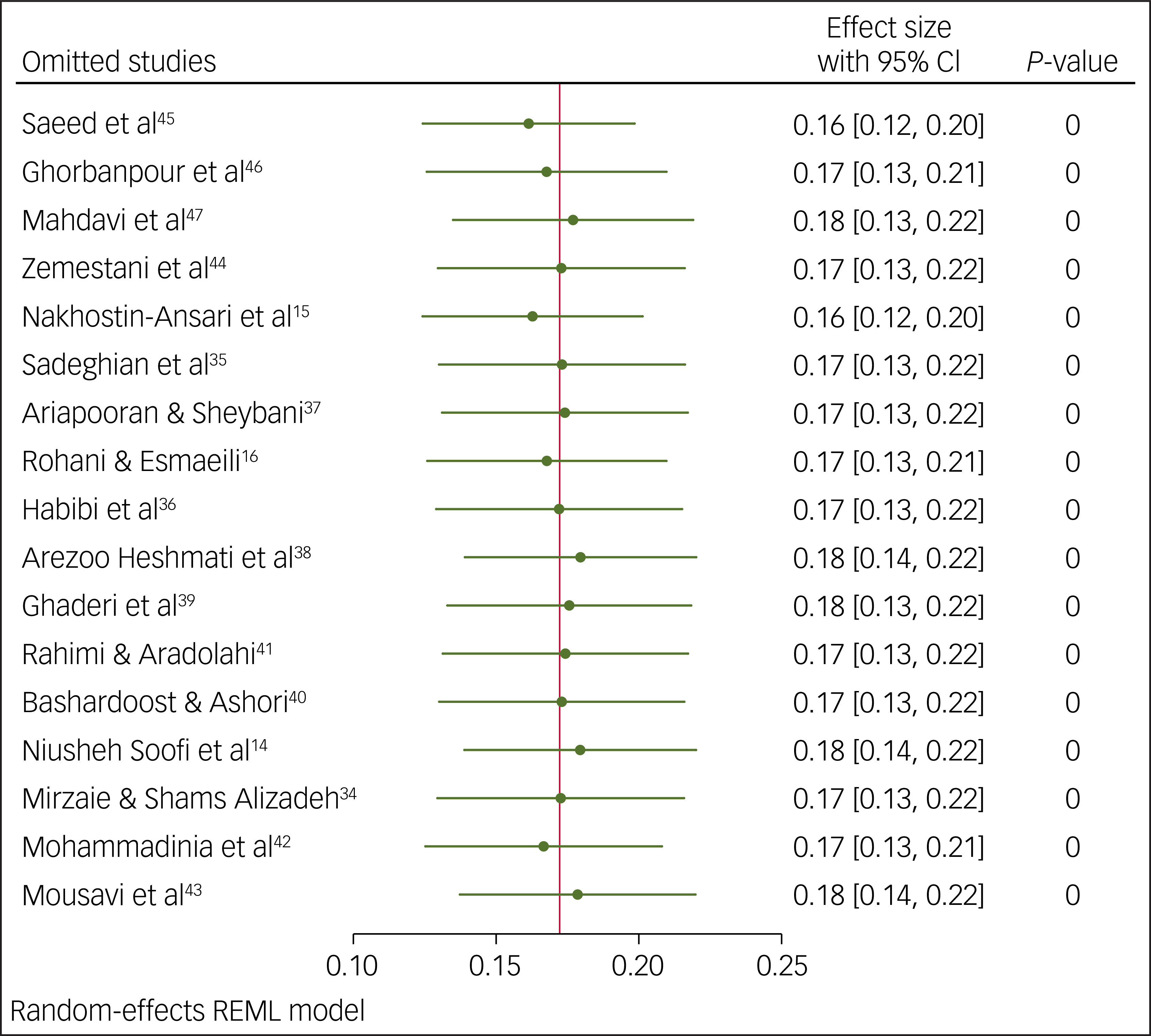

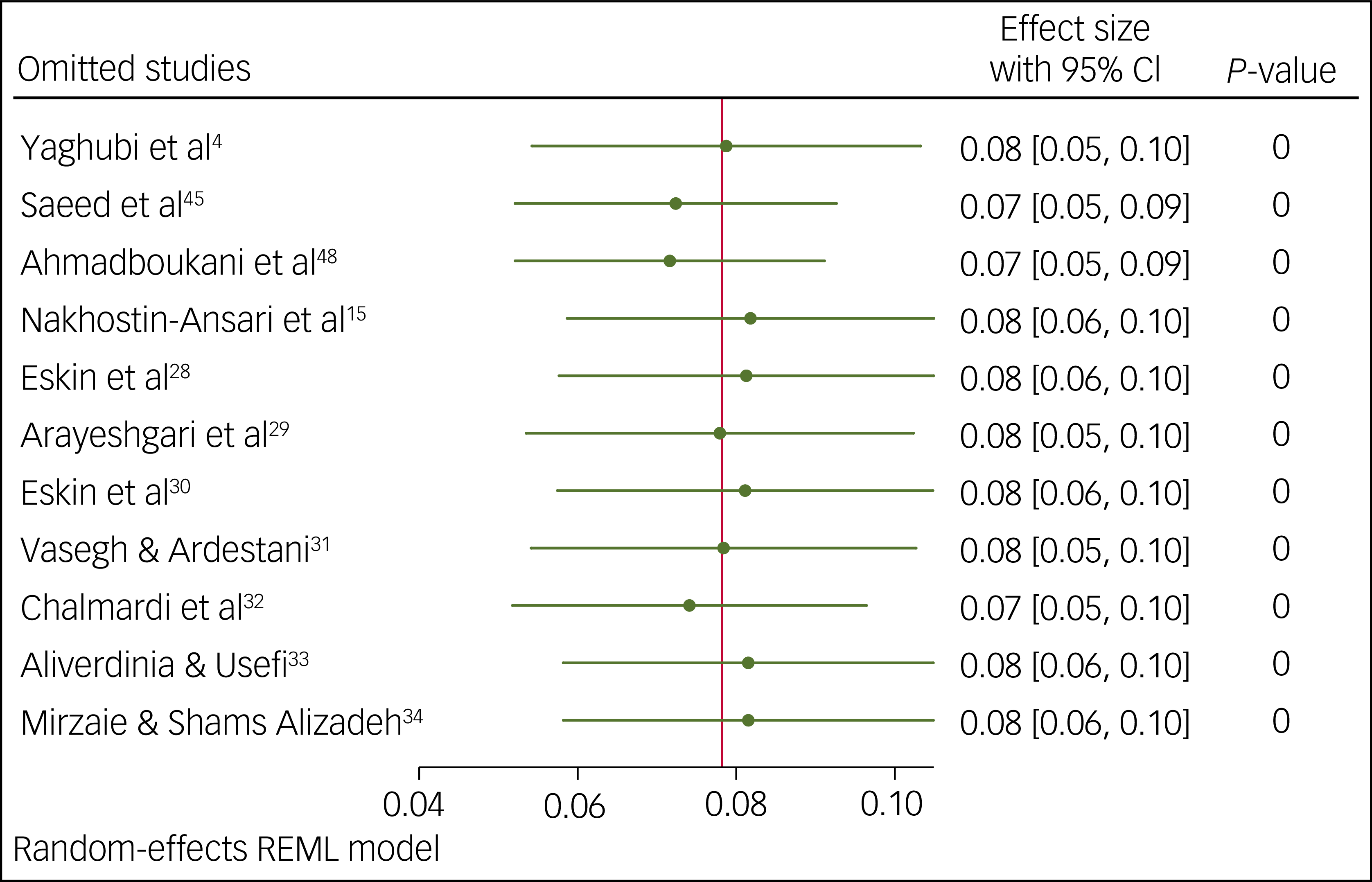

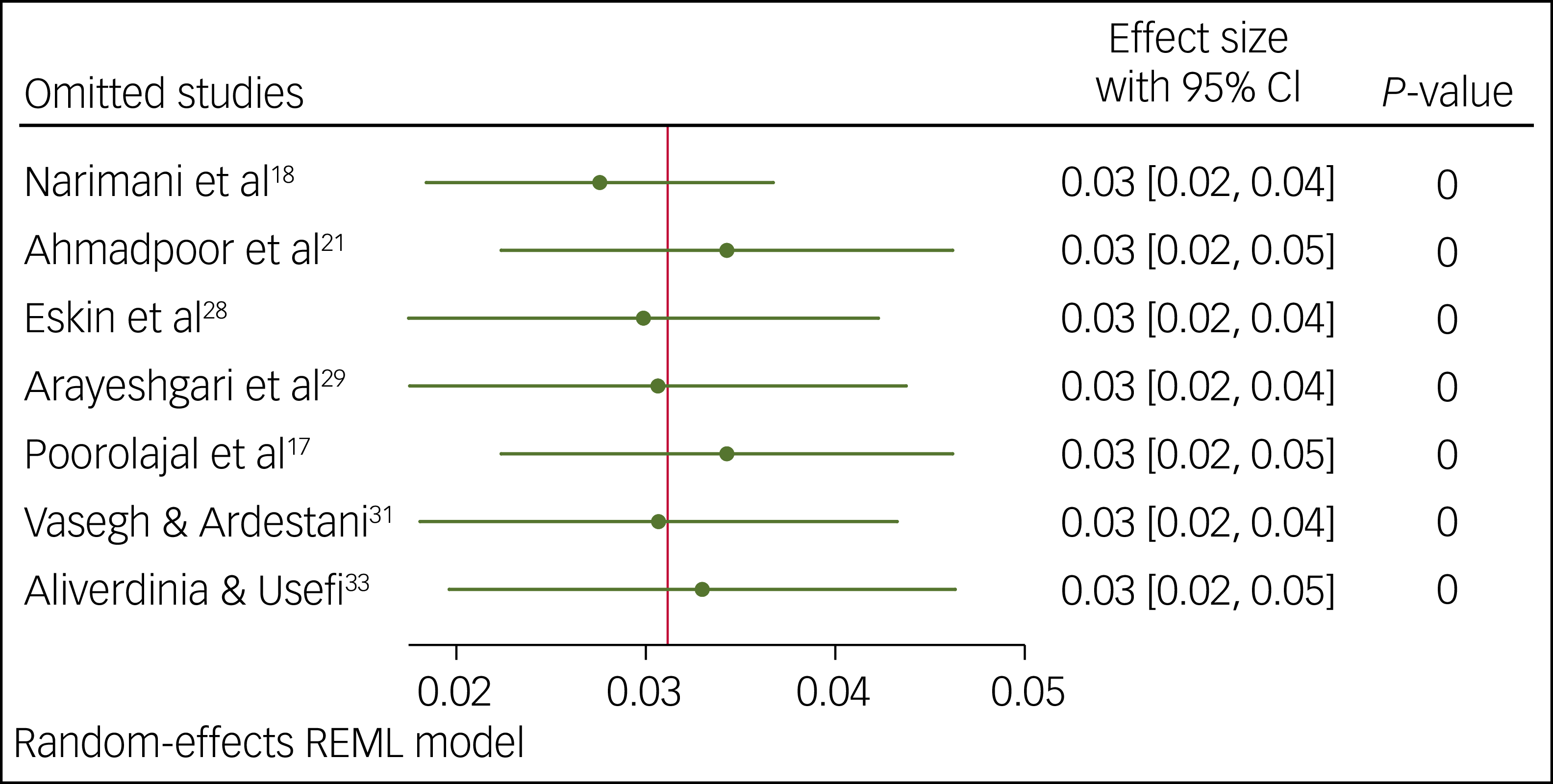

We performed a sensitivity analysis for the prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts using the leave-one-out method. The results of this analysis indicated that none of the point estimates for the occurrence of suicidal ideation (Fig. 5), or attempts of suicide (Figs 6 and 7), deviated from the overall 95% confidence interval. In essence, fluctuations in the prevalence of suicidal ideation ranged 16–18%, variations in the occurrence of lifetime attempts of suicide ranged 7–8% and the point estimation for past-year suicide attempt was 3%, all of which were statistically significant (P < 0.001).

Fig. 5 Sensitivity analysis for prevalence of suicidal ideation among Iranian students. REML, restricted maximum likelihood.

Fig. 6 Sensitivity analysis for lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts among Iranian students. REML, restricted maximum likelihood.

Fig. 7 Sensitivity analysis for prevalence of past-year suicide attempts among Iranian students. REML, restricted maximum likelihood.

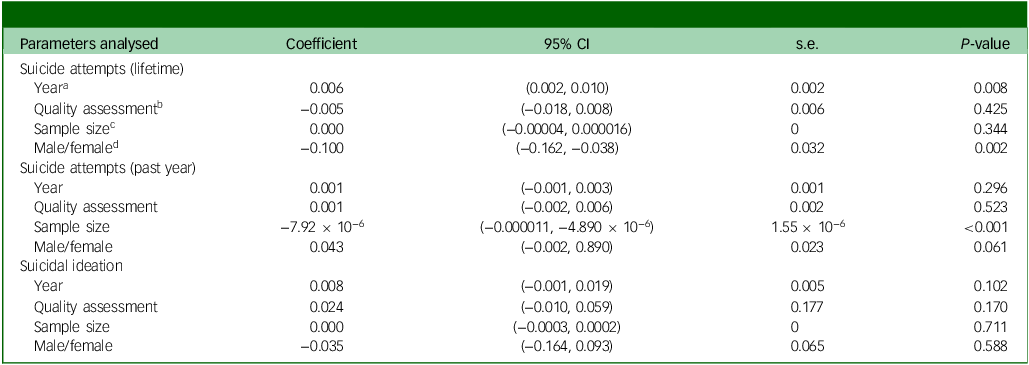

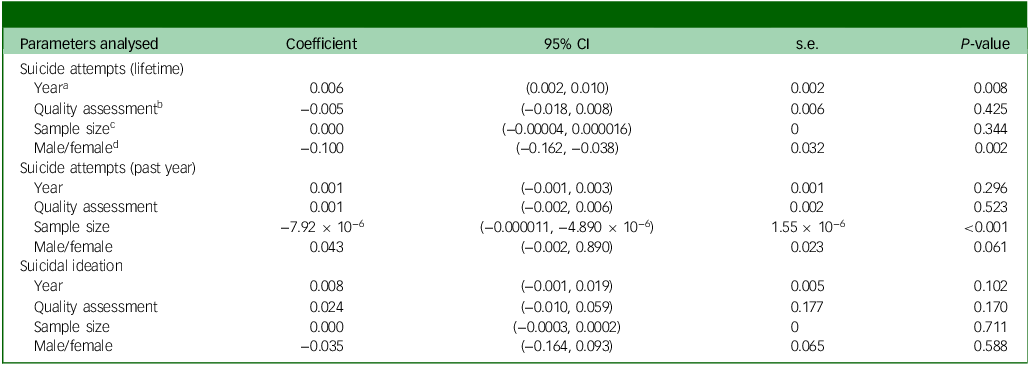

Results of meta-regression analysis

We used meta-regression to identify the sources of heterogeneity. In the suicidal ideation analysis, none of the examined moderators were significantly associated with effect size. In the lifetime suicide attempts analysis, publication year (P = 0.008) and male:female ratio (P = 0.002) were significantly associated with effect size (i.e. the prevalence of lifetime suicide attempts), so that more recent studies and a higher proportion of women were both associated with higher prevalence. In the analysis of past-year suicide attempts, only sample size showed a significant association with effect size (P < 0.001), with smaller studies reporting higher prevalence rates (Table 3).

Table 3 Meta-regression analyses on the prevalence of suicide attempts (lifetime, past year) and suicidal ideation

a. Publication year. b. Newcastle–Ottawa quality score (higher score denotes better quality). c. Total participants (units, 1). d. Male:female ratio.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to estimate the prevalence rates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among university students in Iran. According to our meta-analysis, the pooled prevalence of suicidal ideation and 12-month and lifetime suicide attempts among Iranian students was 17% (95% CI: 13–21%), 3% (95% CI: 2–4%) and 8% (95% CI: 6–10%), respectively.

By conducting a meta-analysis of 17 studies, we found that the current prevalence of suicidal ideation in Iranian students is 17% (95% CI: 13–21%). Based on a systematic review and meta-analysis, Reference Arafat, Baminiwatta, Menon, Singh, Varadharajan and Guhathakurta49 the current and 12-month prevalence of suicidal ideation in students of Muslim-majority countries is 6.4% (95% CI: 4.5–9%) and 13.4% (95% CI: 11.1–16.1%), respectively. In addition, Mortier et al Reference Mortier, Cuijpers, Kiekens, Auerbach, Demyttenaere and Green10 found that the worldwide 12-month frequency of suicidal ideation in college students was 10.6% (95% CI: 9.1–12.3%). It appears that students of Muslim-majority countries, including Iran, exhibit more frequent suicidal ideation than other students around the world. Reference Mortier, Cuijpers, Kiekens, Auerbach, Demyttenaere and Green10,Reference Arafat, Baminiwatta, Menon, Singh, Varadharajan and Guhathakurta49 The higher suicidal ideation of students in Muslim-majority countries is probably due to their harsh living conditions. Extensive economic sanctions, high inflation, shortage of medicines and medical equipment, administrative corruption, lack of democracy and the non-existence of security are among the problems inherent in these countries. Reference Mahdavinoor and Mahdavinoor50 These difficulties can have negative effects on students’ mental health in the long term. Despite these conditions, religion as a source of meaning in life can probably act as an defence against suicide in Muslim-majority countries. Reference Mahdavinoor and Alizadeh51–Reference Mahdavinoor53 Moreover, Islamic teachings consider suicide a greater sin (kabīrah), and this strong religious prohibition could reduce suicide rates in Muslim societies. 54

In this research, by performing a meta-analysis on 7 studies, we found that the 12-month prevalence of suicide attempts in Iranian students is 3% (95% CI: 2–4%); and, using a meta-analysis of 11 studies, we found that the lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts in Iranian students is 8% (95% CI: 6–10%). According to another study, the occurrence of suicide attempts in the general population of Iran was 131 per 100 000 people, Reference Asadiyun and Daliri55 which is clearly lower than the rate among students. This variation in the prevalence of suicide attempts between students and the general population is probably due to the more difficult living conditions of the former. If a person does not have a valued meaning in life, problematic living conditions and mental pressures can lead to suicide, with the aim of relieving pain. Reference Edwards and Holden56 The results of a research conducted in 2022 in one of Iran’s universities also showed that about 95% of students felt they had no meaning in life and that they were not searching for any. Reference Mahdavinoor, Mollaei and Mahdavinoor2 According to one meta-analysis, Reference Mortier, Cuijpers, Kiekens, Auerbach, Demyttenaere and Green10 the frequency of suicide attempts in college students worldwide during their lifetime and over the past year was 3.2% (95% CI: 2.2–4.5%) and 1.2% (95% CI: 0.8–1.6%), respectively, which is lower than the suicide attempt rate for Iranian students. According to another meta-analysis, Reference Arafat, Baminiwatta, Menon, Singh, Varadharajan and Guhathakurta49 suicide attempts among students of Muslim-majority countries during their lifetime and over the past year were 6.6% (95% CI: 5.4–8%) and 4.9% (95% CI: 3.6–6.5%), respectively.

Considering the relatively high prevalence of suicidal ideation and attempts among Iranian university students, measures should be taken as soon as possible to resolve this problem. Furthermore, there are limited suicide-related studies in Iran, and these investigations usually have methodological flaws. The government should continuously monitor the prevalence of suicidal ideation and behaviour among students, with extensive and long-term planning, in order to find both protective and risk factors in each subculture separately. Efforts to destigmatise mental disorders and psychologist consultation, Reference Mahdavinoor and Mahdavinoor50 continuous logotherapy of students Reference Mahdavinoor, Miandashti and Mahdavinoor57 and increasing the amount of education loans to solve economic problems are probably appropriate short-term solutions.

The high level of heterogeneity observed in our meta-analysis is a common challenge in prevalence studies, Reference Migliavaca, Stein, Colpani, Barker, Ziegelmann and Munn58 reflecting the diverse methodologies, populations and measurement tools used in the included studies. Meta-regression showed that, for lifetime suicide attempts, publication year was positively associated with the pooled prevalence, and that the male:female ratio was negatively associated with it; for past-year suicide attempts, sample size was negatively associated with the estimates (consistent with small-study effects). Nevertheless, residual heterogeneity remained substantial and, with the available moderators, we could not fully account for between-study variability. This unresolved heterogeneity underscores the need for future studies with standardised methodologies and consistent reporting of key variables (e.g. demographic characteristics and study design features). Furthermore, exploring broader contextual contributors – such as cultural, regional or institutional differences – may provide greater insight into factors driving the variability in suicidal ideation and attempts among Iranian university students.

Limitations

The study we conducted has a number of limitations, most of which we encountered stem from those of the primary studies. First, the majority of studies used BSSI Reference Beck, Kovacs and Weissman59 to measure the prevalence of suicidal ideation. Some studies had scored the scale in new ways, but none reported evidence for the validity and reliability of their new scoring methods. In the present research, to measure the occurrence of suicidal ideation we included only those studies that used valid scales and scoring methods. Second, due to the nature of this work (a prevalence meta-analysis), heterogeneity was high and its sources could not be fully identified. Third, the studies we reviewed estimated prevalence at different times and in various locations; given the scarcity of studies, we could not determine whether suicide has decreased or increased over time. Another limitation was the small number of studies conducted within Iran’s various subcultures. Iran comprises multiple subcultures and, in this study, we were unable to estimate suicide prevalence separately for each subculture. We also found that several questionnaires had been used across studies to measure suicidal ideation; this may be one of the reasons for differences in prevalence rates between countries. It is not possible to specify the direction of this effect – that is, whether the use of different questionnaires tends to increase or decrease reported prevalence. Finally, although the protocol for this review was registered in PROSPERO (no. CRD42023471340), the statistical analysis section in the registered record was mistakenly written based on a different, unrelated study. Nevertheless, the analyses actually conducted in this review were appropriately designed in accordance with its specific objectives and data-set.

Clinical implications

The findings of this study indicate that suicidal ideation and suicide attempts are highly prevalent among Iranian university students. This has serious implications for both public health and higher education, and universities should consider suicidality as a major priority in student health policies. Early detection and prevention programmes must be systematically implemented in universities. Counselling centres should be strengthened and made more accessible. Awareness campaigns and peer-support initiatives are also needed to reduce the stigma around mental health services. Routine screening for suicidal ideation could help identify students at risk before a crisis occurs.

Future directions

This systematic review and meta-analysis highlights the prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among Iranian university students, emphasising the urgent need for more robust and comprehensive research in this area. The current body of research in Iran is not only limited, but also marked, by significant methodological and statistical shortcomings, including small and unrepresentative samples, lack of standardised tools for assessment of suicidal behaviours and inconsistent data reporting.

Future studies should focus on overcoming these limitations through employing rigorous methodologies, such as larger, more diverse and representative samples, standardised instruments for measuring suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, and advanced statistical analyses. Moreover, there is a pressing need for longitudinal studies to explore causal relationships and trends over time, as well as mixed-methods research to provide deeper insights into the underlying cultural, social and academic factors that contribute to suicidal behaviours.

Efforts should also be directed towards developing and evaluating culturally appropriate interventions, such as mental health education programmes, accessible counselling services and peer support networks, to reduce the prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in this population. Moreover, fostering collaboration among universities, mental health organisations and policy-makers will be critical to designing and implementing effective, evidence-based strategies for suicide prevention among university students in Iran.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2025.10921

Data availability

Following reasonable request, the data will be made available by the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the assistance of ChatGPT (GPT-4) by OpenAI for language enhancement and clarity improvement in the preparation of this manuscript. Artificial intelligence was used solely for linguistic refinement, and all intellectual content, interpretations and conclusions remain the responsibility of the authors.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation, methodology, data curation, validation, project administration and writing – original draft: S.M.M.M.; investigation: N.M., L.S., A.-H.B., R.D. and S.M.M.M.; formal analysis: A.M.; supervision: S.M.M.M. and L.S.; writing – review and editing: S.M.M.M and L.S.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.