Introduction

Promoting healthy eating in children is a key public health priority, given its influence not only on lifelong eating behaviors but also on the predisposition to various long-term morbidities, including obesity, ischemic heart disease, and dental caries.(Reference Mascarenhas, Furtado, Almeida, Ferraz, Ferraz and Oliveira1,Reference Weihrauch-Blüher, Schwarz and Klusmann2) Within this context, the family environment plays a fundamental role in the implementation of appropriate dietary strategies, given that family members are central to shaping healthy habits. Evidence consistently shows that early adoption of adequate dietary practices leads to more favorable long-term outcomes, and the family’s eating pattern should therefore be regarded as a modifiable factor with the potential to influence health throughout life.(Reference Zhang, Yu and Yu3,Reference Mahmood, Flores-Barrantes, Moreno, Manios and Gonzalez-Gil4)

Healthy eating from pregnancy onward is essential to ensure proper child growth and development. During the first 1,000 days of life, from conception to two years of age, adequate maternal and infant nutrition helps reduce cardiometabolic risk and future obesity while supporting cognitive development and human capital formation.(Reference Bhutta, Ahmed and Black5–Reference Black, Liu and Hartwig7) Adequate intake of macro- and micronutrients plays a vital role in this process: folic acid prevents neural tube defects, iron supports brain development, and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) deficiency is linked to premature birth.(Reference Christifano8–Reference Reis, Teixeira and Maia10) Exclusive breastfeeding up to 6 months, followed by the gradual introduction of in natura or minimally processed foods, is fundamental for ensuring healthy growth and balanced microbiota composition, thereby reducing the risk of noncommunicable diseases.(Reference Onyango, Kimani-Murage and Kitsao-Wekulo11–Reference Naghavi, Ong and Aali17)

Educational technologies are increasingly used to disseminate health information effectively.(Reference Teles, de Oliveira and Campos18) Within nutrition education, several strategies have shown promising outcomes, such as comic books, illustrated brochures, and visual media that enhance engagement and retention of information.(Reference Leung, Tripicchio, Agaronov and Hou19–Reference Fonseca, Bertolin, Gubert and da Silva23) The use of comics in health education has been validated across multiple contexts, proving to be an innovative and playful yet effective method for conveying complex information and promoting behavioral change.(Reference Benevides, Coutinho and Pascoal24–Reference Morel, Peruzzo, Juele and Amarelle32)

The Playing and Learning About Health initiative aims to provide lay audiences with accessible educational materials. This study builds on that framework, focusing on the development and validation of a comic book designed to promote healthy eating among caregivers of children aged 0 to 5 years, as well as to assess its impact on participants’ knowledge.

Methods

This study involves the development of an educational technology. It was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards outlined in Resolution 466/2012 of the National Health Council of the Ministry of Health and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (CAAE: 55114821.6.0000.5374). Financial support was provided by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP; Grant number: 2022/02599-6), which funded only the research-related costs. The funding agency had no role in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, interpretation, manuscript preparation, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

The validation of the comic book involved an invitation extended to 31 expert judges and 62 representatives of the target audience, who were caregivers responsible for feeding children aged 0 to 5 years. The selection of expert judges was based on curriculum analyses available on the Lattes Platform (http://lattes.cnpq.br/), an integrated database of individual researchers and Brazilian institutions, supervised by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq). Inclusion criteria required that candidates meet at least two of the following requirements: a minimum of 10 years’ experience in child-focused health promotion or prevention activities; scientific publications related to food health and/or childhood obesity; participation in the development and validation of educational materials; and possession of a master’s or doctoral degree with scientific output in the fields of nutrition, collective health or pediatrics. Representatives of the target audience were recruited by convenience sampling in the waiting room of a private pediatric clinic in Lavras, Minas Gerais (MG). To be eligible, participants had to be responsible for feeding at least one child aged 0 to 5 years.

The study was conducted in four phases:

-

1 – Script creation:

The story script was developed after reviewing the literature and consulting guidelines published by the Brazilian Society of Pediatrics(33) and the Ministry of Health.(34) The narrative follows a character who, after a typical day, wakes up the next morning, looks into the mirror, and finds that her appearance has changed. Seeking answers, she visits a friend, who helps her recall the healthy eating practices her family has followed. The script emphasizes key aspects of food health, including maternal nutrition during pregnancy,(Reference Fisk, Crozier, Inskip, Godfrey, Cooper and Robinson35,Reference Ouyang, Cai and Wu36) exclusive breastfeeding until six months of age,(Reference Hossain and Mihrshahi37,Reference Onyango, Kimani-Murage and Kitsao-Wekulo38) the introduction of all food groups during complementary feeding,(Reference Snetselaar, de Jesus, DeSilva and Stoody39,Reference Soriano, Ciciulla and Gell40) the exclusion of processed and ultra-processed foods,(Reference Khoury, Martínez and Garcidueñas-Fimbres41–Reference Petridi, Karatzi, Magriplis, Charidemou, Philippou and Zampelas43) and the importance of healthy snacks during the school year.(Reference Correa-Burrows, Rodríguez, Blanco, Gahagan and Burrows44,Reference Jamaluddine, Akik and Safadi45)

-

2 – Preparation of the initial version of the comic book (illustrations, layout, design):

Based on the script, original illustrations were developed and characters were created. Page formatting, layout, and design were executed using Adobe Photoshop® and Adobe InDesign®, in collaboration with an experienced graphic designer. Content development followed key criteria related to substance, structure and organization, language, layout, design, cultural sensitivity, and contextual appropriateness for the intended audience. The characters were modeled after those used in previous publications from the Playing and Learning About Health project. To ensure clarity and accessibility, inclusive and respectful language was used to facilitate understanding and emphasize the roles of both individuals and families in promoting healthy eating practices.(Reference Alexandre and Coluci46) During this phase, the Flesch Readability Index (FI) was calculated to ensure a minimum threshold of 70%, and classified the material as reasonably easy to very easy to understand.(Reference Benevides, Coutinho and Pascoal24,Reference Alexandre and Coluci46)

-

3 – Validation of the initial version:

Expert judges were provided with a printed copy of the comic book along with a questionnaire containing eight items to gather sociodemographic data. After a careful and critical reading of the material, they completed an evaluation questionnaire,(Reference da Rosa, Girardon-Perlini, Gamboa, Nietsche, Beuter and Dalmolin47) which was organized into three sections: adequacy (5 items), structure (8 items), and relevance (5 items) of the comic book. Responses were recorded using a four-point Likert scale: Totally Adequate (TA), Adequate (A), Partially Adequate (PA), and Inadequate (I). Space was provided for the judges to justify their ratings and offer suggestions for improvement.

Based on the judges’ responses, the Content Validity Index (CVI) was calculated for each item (I-CVI), for each block (S-CVI/AVE Block), and globally (S-CVI/AVE Global). The CVI measures the relevance and representativeness of each element in a research instrument, with values ranging from 0 to 1. The calculation involved summing the number of responses rated as “Adequate” and “Totally Adequate,” dividing by the total number of responses, and multiplying by 100. The minimum acceptable threshold defined for this study was 80%.(Reference de Medeiros, Zanin, Sperandio, de Souza Fonseca Silva and Flório25,Reference Flório, Rached, Victorelli, Silva and Arsati26,Reference Benevides, Coutinho and Pascoal48)

-

4 – Preparation of the revised version of the comic book and pilot test:

Following the revisions to the comic book based on the expert judges’ suggestions, the FI was recalculated, and the final version of the material was completed. A pilot test was then conducted with representatives of the target audience. Before reading the comic book, participants completed a questionnaire comprising four sociodemographic questions and six questions assessing knowledge of practices related to healthy eating. This questionnaire – developed by the researchers and reviewed by 11 pediatricians and nutritionists – addressed the following topics: characteristics of a healthy diet(Reference Blumfield, Mayr and De Vlieger49,Reference Vinitchagoon, Hennessy and Zhang50) ; recommendations for exclusive breastfeeding(Reference Meek and Noble51,Reference Nigatu, Azage and Motbainor52) ; strategies for introducing complementary feeding(Reference Chiang, Hamner, Li and Perrine53,Reference Roe, Meengs, Birch and Rolls54) ; characteristics of healthy snacks for children(Reference Jansen, Thapaliya, Beauchemin, D’Sa, Deoni and Carnell55); eating behaviors in children over 2 years of age(Reference Beets, Tilley, Kim and Webster56); and appropriate snack choices during the school year.(Reference Beets, Tilley, Kim and Webster56)

The printed comic books were distributed, and after being made available for 15 days, participants completed an evaluation questionnaire regarding the material. The questionnaire was divided into 4 blocks: reading process (3 questions), content (6 questions), visual (5 questions), and characters (3 questions), using a valuation scale from “Totally Adequate” (TA) to “Inadequate” (I). Additionally, five questions addressed the organization, writing style, appearance, narrative motivation, and overall usefulness of the comic book.(Reference de Medeiros, Zanin, Sperandio, de Souza Fonseca Silva and Flório25,Reference Flório, Rached, Victorelli, Silva and Arsati26) At this time, the knowledge questionnaire was also reapplied. The CVI for version 2 of the material was calculated at the item level (I-CVI), block level (S-CVI/AVE Block), and globally (S-CVI/UA Global).

The educational comic book developed and validated in this study is entitled Dentitos – Playing and Learning About Health: Food Health. On the inside cover, the Playing and Learning About Health initiative is introduced, along with its objective of using educational technologies to reach the target audience. The body of the publication consists of a comic strip, while the final section presents a timeline highlighting the key recommendations for food health in children aged 0 to 5 years, as well as thematic activities. The material was registered with the Brazilian Book Chamber (CBL) under ISBN: 978-65-86718-61-4 (Portuguese and English versions) and comprises a cover, back cover, and 16 pages, formatted in a standard size of 21 cm high by 14.8 cm wide. The final version of the comic book is available for free download in both Portuguese and EnglishFootnote 1 .

For each version of the comic book, an exploratory statistical analysis was conducted using Microsoft Office Word, assessing components of the material, including the presentation and body of the comic strip. The number of pages, words, characters (with and without spaces), paragraphs, and lines – typed using single spacing – were recorded. Descriptive and exploratory analyses were also performed to characterize the profiles of the expert judges and members of the target audience, based on absolute and relative frequencies.

The FI was calculated for both versions (01 and 02) to evaluate the readability level of the text, based on a scale from 0 to 100. Higher FI values indicate easier reading and suggest that the material requires a lower level of formal education for comprehension by a lay audience.(Reference Benevides, Coutinho and Pascoal24) CVIs were then estimated at the item level (I-CVI) for each block of the evaluation questionnaire completed by expert judges (objectives, structure, and relevance) and by the target audience (content, audiovisual elements, and characters). The CVI quantifies the proportion of evaluators who consider each item relevant or representative.(Reference Alexandre and Coluci46) For this purpose, responses were grouped into two categories: “relevant/representative” (sum of responses rated “Totally Adequate” and “Adequate”) and “needs correction” (sum of responses rated “Partially Adequate” and “Inadequate”). Subsequently, CVIs were calculated at the block level (S-CVI/AVE), representing the average of the I-CVIs within each block, as well as the global level.

CVIs were also estimated at the scale level (S-CVI/UA), which measures the proportion of items rated as positive by each judge or layperson, along with the global average. In the present study, a minimum CVI of 0.70 (70%) was considered acceptable,(Reference Lopes, Silva and de Araujo57) while a more stringent threshold of 80% was established to ensure the validity of the material.(Reference Benevides, Coutinho and Pascoal24–Reference Flório, Rached, Victorelli, Silva and Arsati26,Reference Yusoff58) To compare scores on the knowledge questions before and after reading the comic book, the paired Wilcoxon test was applied. In addition, the absolute and relative frequencies of participants were calculated based on the change in the total score following the intervention. All analyses were conducted using R software, with the significance level set at 5%.

Results

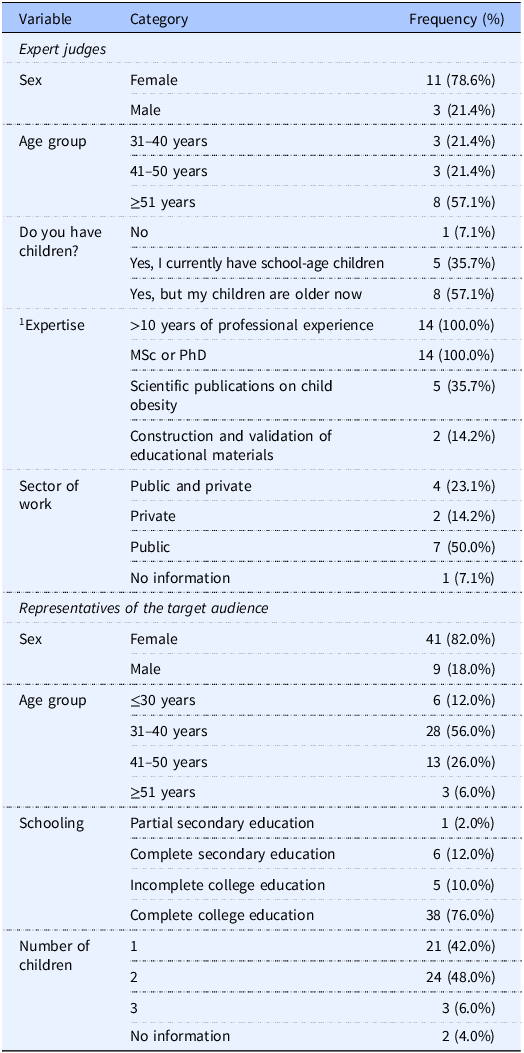

Table 1 presents the profile of the expert judges and the representatives of the target audience who participated in the study. Among the 31 expert judges invited, 14 agreed to evaluate the initial version of the comic book. Most of the judges were women (76.8%), and over 51 years of age (57.1%). All held stricto sensu graduate degrees and had more than 10 years of professional experience. Regarding the target audience, the majority of the participants were women (82%), aged 40 years or younger (68%), and had completed college (76.0%).

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of expert judges (n = 14) and the representatives of the target audience (n = 50)

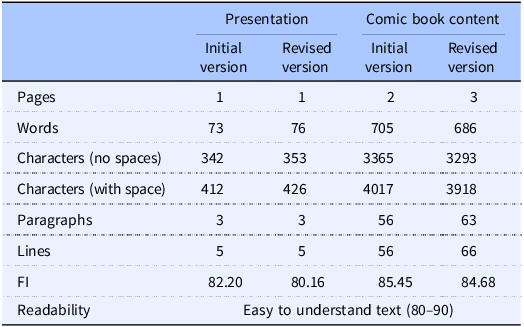

Table 2 presents the exploratory analysis of statistics generated using Microsoft Office Word, as well as the calculation of the FI and its corresponding reading ease classification. Following the expert evaluation of the initial version, modifications were made – primarily an increase in the amount of text in the introductory section and a reduction in the text within the comic strip itself. These adjustments did not affect the overall readability of the material. In both versions, the F1 scores remained between 80 and 90, classifying the content as “easy to understand.”

Table 2. Exploratory statistics generated by Microsoft Office Word, Flesch Readability Index (FI), and readability classification for each section of the comic book

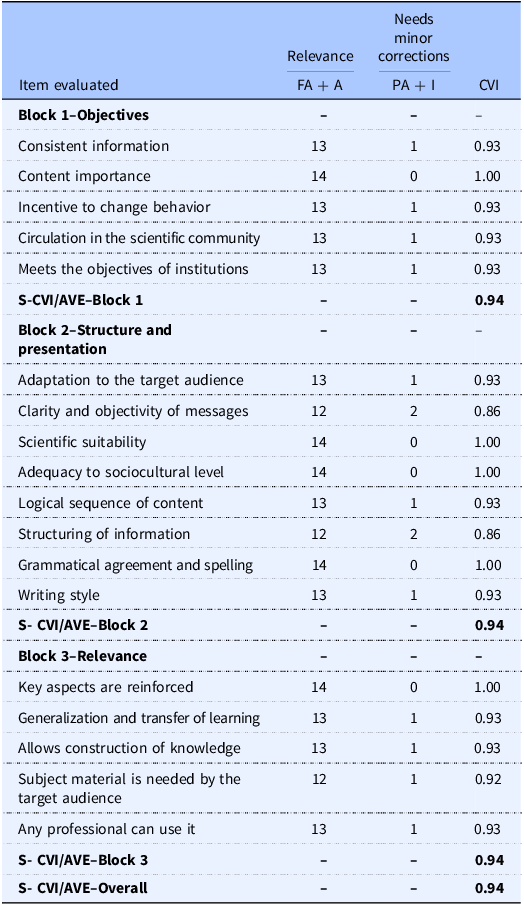

Table 3 presents the CVIs of the initial version of the comic book, as rated by expert judges. These include item-level indices (I-CVI), block-level averages (S-CVI/AVE Block), and the overall index (S-CVI/AVE Global). The global CVI was 0.94 (94%), a value equivalent to the indices obtained for the “Objectives,” “Structure and Presentation,” and “Relevance” blocks. These values indicate excellent agreement in the evaluations performed by the judges. Furthermore, all items evaluated in each block presented CVIs equal to or greater than 0.86. Most of the expert judges’ suggestions were incorporated into the revised version. These included rephrasing and condensing certain dialogues and narrative passages, as well as refining terminology to make technical content more accessible to lay readers. Modifications were also made to broaden the portrayal of caregiving responsibilities, emphasizing the role of all caregivers – not just mothers. In addition, adjustments were made to the positioning of selected illustrations for improved visual coherence. The main focus of the comic book, originally centered on childhood obesity, was expanded to encompass general dietary health. This change reflected the broader scope of the content and acknowledged that obesity, as a multifactorial condition, could not be addressed comprehensively within the format of the comic book.

Table 3. Content validity indices by item, block, and overall, according to expert judges – Initial version of the comic book (n = 14)

A, Adequate; FA, Fully Adequate; PA, Partially Adequate; I, Inadequate; CVI, Content Validity Index; S-CVI/AVE, Scale-Level Content Validity Index (average calculation method).

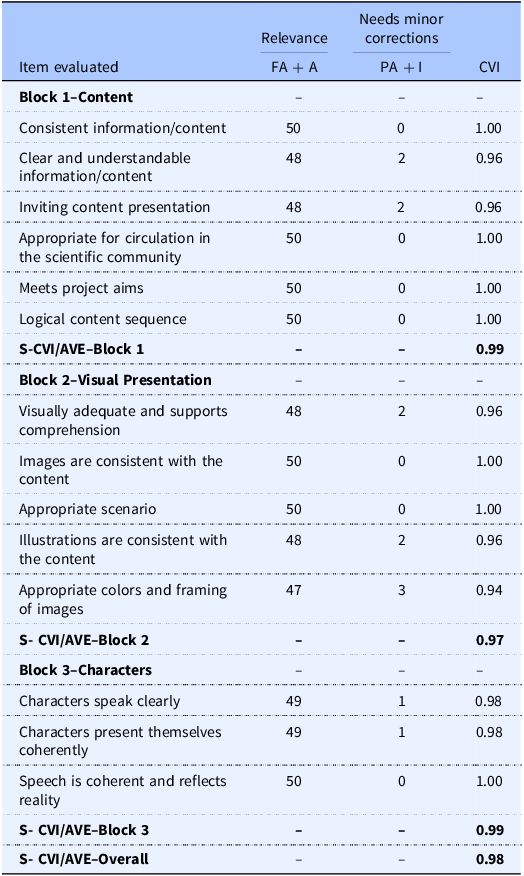

After implementing these changes, the revised version of the comic book was submitted for evaluation by the target audience. The CVIs derived from the responses are shown in Table 4. The average scale-level CVI (S-CVI/UA) was 0.98, exceeding the established minimum threshold of 0.80. The CVI was 0.99 (99%) for the “Content” block, 0.97 (97%) for the “Visual” block, and 0.99 (99%) for the “Characters” block. The lowest I-CVI observed was 0.94 (94%), indicating strong agreement among participants regarding the quality and relevance of the material.

Table 4. Content validity indices by item, block, and overall, according to the general public – Revised version of the comic book (n = 50)

A, Adequate; FA, Fully Adequate; PA, Partially Adequate; I, Inadequate; CVI, Content Validity Index; S-CVI/AVE (Scale-level Content Validity Index, average calculation method).

The descriptive analysis of the overall evaluation revealed a highly favorable reception of the comic book. A total of 98% (n = 49) of readers considered the illustrative cover to be visually appealing and conducive to engagement, and 98% (n = 49) found the text presentation interesting. All participants (100%, n = 50) agreed that the illustrations enhanced their understanding of the narrative in an imaginative and playful manner. Additionally, 98% (n = 49) reported feeling motivated to read the story to its conclusion, and 100% (n = 50) believed the comic book would contribute to health education efforts for the general population.

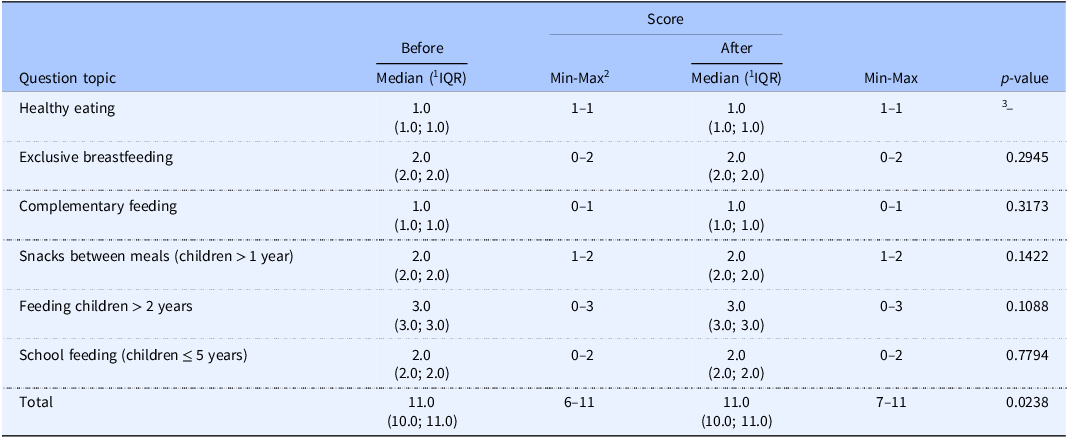

Table 5 shows that reading the comic book led to an increase in the number of correct responses on the knowledge assessment instrument concerning healthy eating practices for children aged 0 to 5 years.

Table 5. Analysis of participants’ knowledge scores before and after reading the comic book (n = 50)

1IQR: Interquartile Range (Q1; Q3). 3 p-value could not be calculated due to lack of variation among responses; all had a score of 1 both before and after reading.

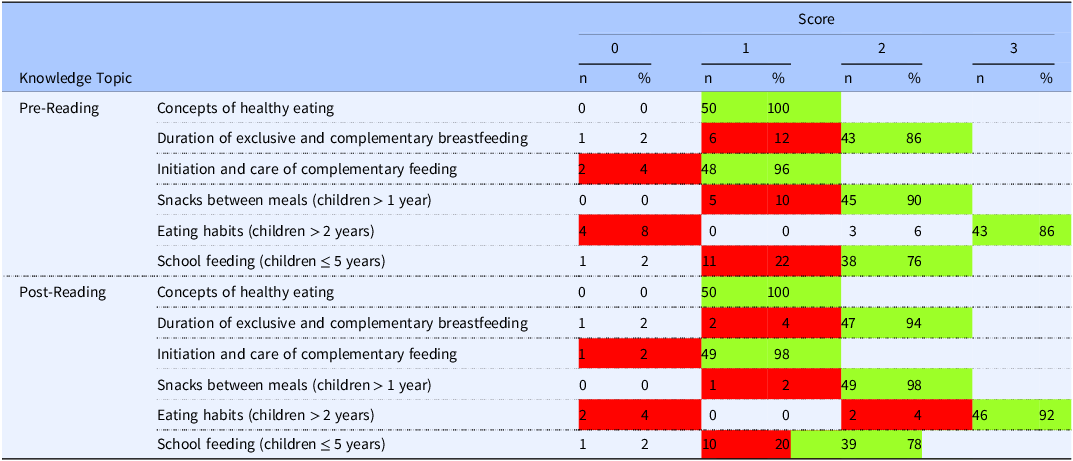

Table 6 presents the descriptive analysis of responses to the knowledge assessment questionnaire administered before and after the intervention. While participants already demonstrated satisfactory knowledge on the general concept of healthy eating during the pre-test (100% correct), improvements were observed in several specific areas after reading the comic book. Notably, correct responses regarding the recommended duration of exclusive breastfeeding and complementary feeding increased from 86% to 94%, the ability to identify appropriate snacks between meals for children over one year of age rose from 90% to 98%, and knowledge of dietary behavior in children over two years of age improved from 86% to 92%. Additionally, marked gains were observed in the proportion of participants who achieved maximum scores on items related to the initiation and care of complementary feeding (from 96% to 98%), and school feeding for children up to five years of age (from 76% to 78%).

Table 6. Descriptive analysis of the questionnaire responses on knowledge of healthy eating in children (n = 50)

Legend: green – highest frequency of responses, red – second highest frequency of responses.

Discussion

The use of comic books in health education has proven effective across a range of contexts.(Reference Leung, Tripicchio, Agaronov and Hou19,Reference Flório, Rached, Victorelli, Silva and Arsati26,Reference Mioramalala, Bruand and Ratsimbasoa59) In the present study, the validated comic book emerged as a valuable resource for promoting healthy eating practices in children aged 0 to 5 years. It achieved high CVI scores and demonstrated strong acceptance by the target audience. CVI values exceeded 80% in both stages of evaluation, surpassing the minimum acceptable threshold of 70%(Reference Benevides, Coutinho and Pascoal24) and reaching the ideal benchmark of 85%.(Reference Lopes, Silva and de Araujo57) These findings indicate that the material was considered representative and relevant by expert judges, while also being clearly understood and positively received by the lay audience.

The evaluation of readability is vital to prevent learning limitations related to low educational attainment.(Reference Teles, de Oliveira and Campos18) The classification of the comic book in terms of ease of reading and comprehension(Reference Benevides, Coutinho and Pascoal24) confirmed its suitability even for individuals with limited formal education. Expert judges highlighted the authors’ attention toward minimizing the amount of text and maximizing the use of images, thereby enhancing accessibility to information. This emphasis is especially important considering that limited knowledge about healthy eating in childhood can lead to adverse outcomes in both the short(Reference Kim, Lee and Ha60,Reference Mertens, Benjamin-Chung and Colford61) and long term.(Reference Bander, Murphy-Alford and Owino62)

Food preferences and dietary habits begin to form during the earliest years of life.(Reference Moore, Fisher, Burgess, Morris, Croce and Kong63) Evidence shows that the attitude and behaviors of caregivers are key to ensuring adequate nutritional health in childhood.(Reference Almeida, Azevedo, Gregório, Barros, Severo and Padrão64–Reference Romanos-Nanclares, Zazpe, Santiago, Marín, Rico-Campà and Martín-Calvo67) Educational strategies directed at caregivers demonstrate effectiveness in increasing knowledge about infant feeding,(Reference De Rosso, Ducrot, Chabanet, Nicklaus and Schwartz68) which is associated with both the encouragement of healthy food consumption by children(Reference Moore, Fisher, Burgess, Morris, Croce and Kong63,Reference Sirasa, Mitchell, Rigby and Harris69) and how caregivers engage in nutritional education.(Reference Serasinghe, Vepsäläinen and Lehto70)

In this study, the target audience comprised adults responsible for feeding children under five years of age, recruited from the waiting room of a private pediatric clinic. Most participants had completed college, which may explain the high baseline knowledge observed.(Reference Moura and Masquio71) This characteristic likely contributed to the absence of statistically significant differences in some comparisons, suggesting a possible ceiling effect that should be considered when interpreting the Wilcoxon test results. Such effects are common in educational and behavioral interventions when participants exhibit high baseline knowledge or favorable attitudes before exposure, which limits the observable margin for improvement. Similar outcomes have been reported in studies using comics and visual narratives in health education, where participants with higher literacy or prior familiarity with the topic demonstrated strong baseline comprehension, resulting in small post-intervention gains despite high engagement and acceptance of the tool.(Reference McCormick, Richard and Caulfield14,Reference Joshi, Hillwig-Garcia and Joshi31)

Although education does not directly determine income, it is often associated with greater job opportunities and financial stability. Income also shapes the home food environment: more affluent families often provide conditions favorable to healthy food choices, while those with fewer resources may lack adequate storage, preparation space, or access to markets offering fresh produce.(Reference Moore, Fisher, Burgess, Morris, Croce and Kong63,Reference Serasinghe, Vepsäläinen and Lehto70,Reference Noiman, Lee, Marks, Grap, Dooyema and Hamner72) In Brazil, maternal education has been shown to influence the quality of a child’s diet; mothers with lower education levels or younger age often provide less dietary diversity and poorer overall nutrition.(Reference Guedes, Höfelmann and Madruga73)

Despite the predominantly high educational level of the sample, composed mainly of caregivers recruited from a private pediatric clinic, the comic book had a positive impact on participants’ knowledge. However, this profile may limit the generalizability of the findings to populations with different socioeconomic and literacy backgrounds. Future studies should include participants from more socioeconomically diverse contexts and assess the applicability of this educational tool in school- and community-based nutrition education programs aimed at promoting healthy eating habits from early childhood.(74)

Overall, participants demonstrated awareness of the fundamental aspects of a healthy diet, including the importance of a balanced intake rich in fruits, vegetables, and legumes consumed daily. Targeted interventions, such as promoting family meals and educating parents, have been shown to increase fruit and vegetable consumption among children.(Reference Noiman, Lee, Marks, Grap, Dooyema and Hamner72) A dietary pattern that incorporates a variety of food groups ensures the intake of essential nutrients needed for proper growth, cognitive development, and immune system support in early childhood.(Reference Guedes, Höfelmann and Madruga73) Participants also recognized the importance of exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life, followed by the introduction of complementary foods, including cereals, tubers, legumes, vegetables, meats, eggs, and fruits. Continued breastfeeding should be encouraged, with emphasis on both its duration and the critical role of exclusivity during the first six months, since this establishes a foundation for long-term health and development.(Reference Juharji, Albalawi and Aldwaighri75)

Regarding snacks between meals for children over one year of age, respondents recognized that these should consist of light, nutritious options such as fruits, bread rolls with cheese, and milk. Regarding 100% fruit juice – that is, juice without sugars or preservatives – there is still controversy in the literature, since the addition of such ingredients is a common habit in many cultures around the world. Some studies indicate that moderate consumption of pure fruit juice does not increase the risk of obesity,(Reference Murray76,Reference O’Neil, Nicklas, Rampersaud and Fulgoni77) and suggest that it may complement the intake of in natura fruits, though it should not replace them entirely.(Reference O’Neil, Nicklas, Rampersaud and Fulgoni77) However, there is growing evidence that excessive consumption of fruit juice can lead to increased intake of calories and sugars.(Reference Styne, Arslanian and Connor78) The consumption of yogurt is somewhat less controversial, since it is generally associated with nutritional benefits, particularly due to its high calcium and protein content.(Reference Cifelli, Agarwal and Fulgoni79,Reference Fiore, Di Profio, Sculati, Verduci and Zuccotti80) Nonetheless, the sugar content of commercially available yogurts varies widely, and excessive intake may negatively affect a child’s health. For this reason, the recommendation is to opt for natural yogurts or, at least, low-sugar alternatives.(Reference Moore, Horti and Fielding81)

Analysis of the issue regarding school snacks revealed that, even after reading the comic book, some participants continued to view processed foods as acceptable options. This perception may reflect the growing time pressures faced by families – particularly mothers – who often balance professional obligations with household responsibilities.(Reference Bechtlufft and Costa82,Reference Cunha, Dimenstein and Dantas83) In the revised version of the comic book, the topic of shared responsibility for children’s nutrition was addressed, aiming to challenge and reshape cultural paradigms in societies where such duties are disproportionately assumed by women.(Reference Benenson84) Although equitable distribution of caregiving duties is ideal, the high proportion of female participants in this study indirectly reflects a reality in which most children attending medical appointments are accompanied by their mothers.

In regard to school snacks, it is important to note that in Brazil, Federal Law No. 11.947, of July 16, 2009, guarantees the right to healthy food in public schools, requiring that snacks be prepared under the supervision of nutritionists. However, this legislation does not apply to private institutions. A persistent challenge involves the lunchboxes prepared by families – especially mothers – for their children attending private schools, where the nutritional quality of food often differs from that offered in public schools.(Reference Vieira, Castro, Fisberg and Fisberg85) International literature also highlights differences between school systems. In some countries, private schools exhibit better nutritional practices,(Reference Sezer, Alpat Yavaş, Saleki, Bakırhan and Pehlivan86) and disparities have also been observed in the types of food options sold in retail outlets surrounding public and private schools.(Reference Smith, Li and Du87)

In addition to the comic strip itself, the educational material also included a timeline summarizing key milestones in healthy eating, such as exclusive breastfeeding up to six months(Reference Meek and Noble51) and the timely introduction of complementary foods.(Reference Lutter, Grummer-Strawn and Rogers13) This timeline reinforces the importance of establishing appropriate feeding practices from gestation through early childhood, consistent with current literature and public health recommendations.(Reference Murphy and Santos-Calderón89)

The use of comic books in health education has proven effective across various contexts. In the present study, the validated comic book emerged as a valuable resource for promoting healthy eating practices in children aged 0 to 5 years, achieving high CVI scores and strong acceptance by the target audience. CVI values exceeded the ideal benchmark of 85%, confirming the material’s relevance and clarity.

Importantly, the evaluation of readability ensured that the material was accessible even to individuals with limited formal education, enhancing its public health applicability. However, it is important to acknowledge that the sample predominantly comprised caregivers with higher educational attainment, recruited from a private pediatric clinic, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to populations with lower literacy levels or different socioeconomic backgrounds. Future research should evaluate the impact of this educational tool in more diverse populations.

Conclusion

The educational comic book was validated for appearance, content, and readability, demonstrating a positive impact on caregivers’ knowledge regarding healthy eating practices for children aged 0 to 5 years. Given its accessibility and effectiveness, the comic book may serve as a scalable tool in community-based nutrition education programs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants who took part in the study and the professionals who contributed to the validation process of the educational material.

Author contributions

CCS: development of the comic book script and validation process, data collection, and manuscript writing. LZ: validation of the comic book and preliminary drafting of the manuscript. MS: translation of the comic book and preliminary drafting of the manuscript. FMF: study supervision, development of the comic book script and validation process, data analysis, and manuscript writing. All authors approved the final version.

Financial support

This study was supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), Grant number 2022/02599-6.

Ethical approval

Approved by the Research Ethics Committee (CAAE: 55114821.6.0000.5374)

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.