Introduction: Social Enterprises and the Original Sins

Social enterprises, as organisations combining an entrepreneurial and a social dimension, and operating in the interstices between the market and the state, have grown to become a salient phenomenon in both academia and policy-making. In Western Europe, the concept, initially bound to the experience of Italian social cooperatives established to facilitate work insertion of people in vulnerable circumstances, has expanded to include any form of socially purposive business activity (Defourny and Nyssens Reference Defourny and Nyssens2010; Nicholls Reference Nicholls2006; Kerlin Reference Kerlin2013). How did a concept become so central to European academic and policy-makers interests? This special issue argues, through its contributions, that the concept and the social phenomena it is meant to portray, have been and still are the reflection of a given socio-economic-political context and zeitgeist that is twentieth-century Europe. Therefore, although we are aware of the difficulties in agreeing on a world-shared definition of social enterprise (Mair Reference Mair, Fayolle and Matlay2010), the papers presented in this special issue build from a ‘European-bound’ operational definition, that is one generated within the EMES network which conceives of social enterprises as:

…organisations with an explicit aim to benefit the community, initiated by a group of citizens and in which the material interest of capital investment is subject to limits. Social enterprises also place high value on the autonomy and on economic risk-taking related to on-going socio-economic activities (Defourny and Nyssens Reference Defourny, Nyssens and Nyssens2006: 5).

Still, the papers gathered in this thematic issue also provide insight into earlier forms of societal organisations that we consider as possible ‘predecessors’ of social enterprises’ activities for they share with social enterprises the ‘…creation of a community benefit regardless of ownership or legal structure and with varying degrees of financial self-sufficiency, innovation and social transformation’ (Brouard and Larivet Reference Brouard, Larivet, Fayolle and Matlay2010: 39).

The file rouge we adopt to analyse the diachronic evolution of those social endeavours that we call social enterprises is their contribution to the development of the most institutionalised form of solidarity experienced in European societies: the welfare state. However, before addressing the connection between social enterprises and welfare states, we shall discuss how, in Europe, social enterprise became such a salient policy tool across a range of domains like employment, care, education, health and well-being.

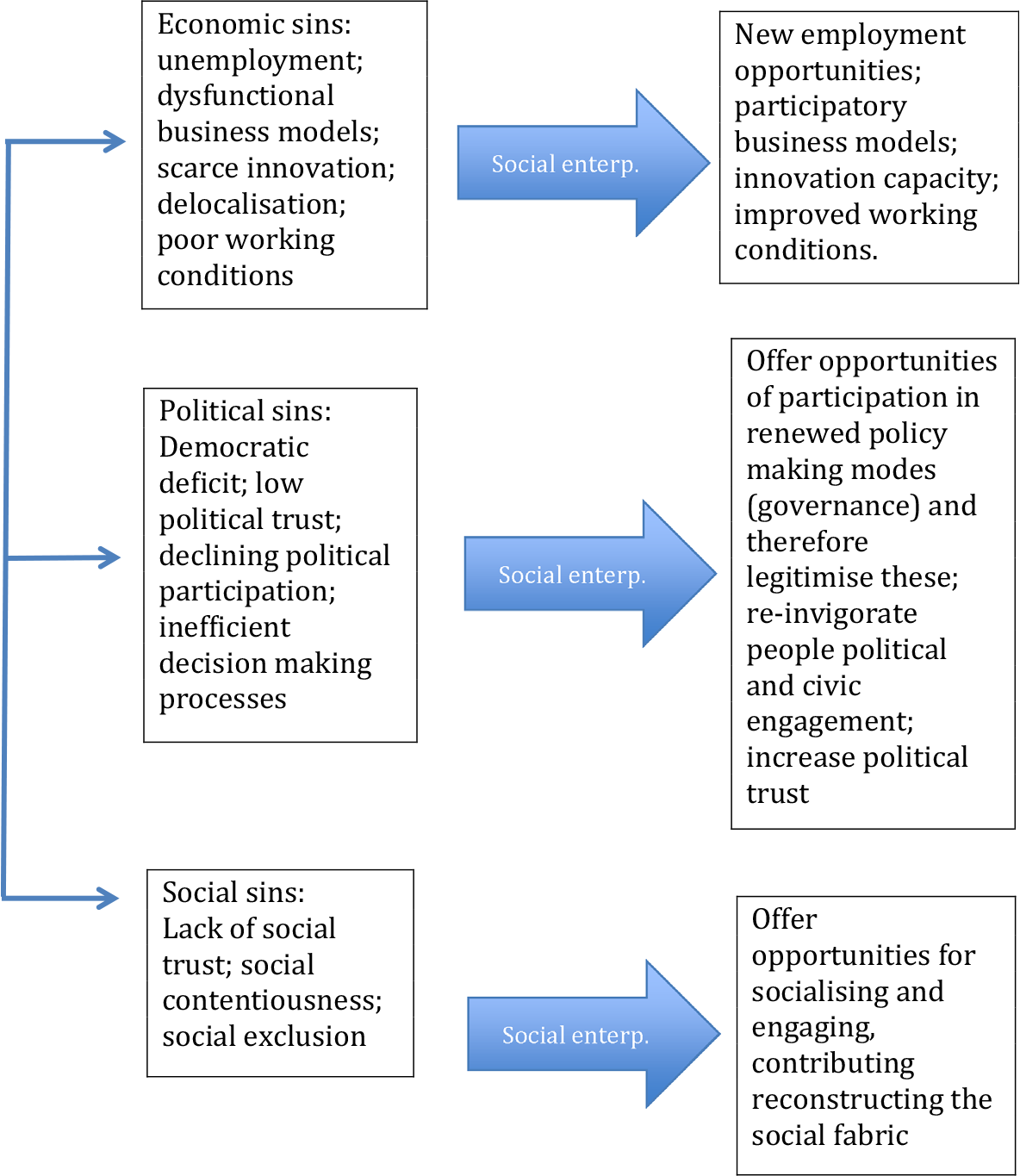

Social enterprise’s centrality in academic and policy discourses is mainly due to its being a malleable concept (Teasdale Reference Teasdale2012), reflecting a multifaceted set of initiatives to remedy structural ‘sins’ at economic, political and social junctures that all reached deadlock from the 1990s onwards.

From an economic point of view, the sin to be cured in Europe was the poor capacity of advanced market economies to secure full employment, and in particular to tackle unemployment among young people and vulnerable categories such as the disabled. By the late 1980s, it was clear that some of the capitalist market economies that had flourished in the post-war years had entered a long cycle of recession in which chances of gainful employment for young people, as well as for vulnerable groups (the disabled, but also people with health issues or criminal backgrounds), were constrained to very limited windows of opportunity. The situation worsened with the emergence of some of the negative consequences of economic globalisation such as job delocalisation, and social (salary) dumping. Moreover, just when publicly funded action could have eased the social and economic burden of the high unemployment rates through Keynesian policies, the states’ capacity to afford them was dramatically curtailed on the one hand by global, financial and economic investment strategies punishing highly debt-ridden countries, and, on the other hand, by those countries subscribing to supranational agreements, anchoring them to financial ‘austerity’ (such as regulations for entering the European monetary union).

From a political point of view, there were several sins that necessitated a redemption solution. From the early 1990s onwards, Western European countries (and even more Central-Eastern ones) started experiencing a chasm between the demos and the political elites governing them. Citizens began to challenge their political authorities by questioning poor performance in meeting societal needs (Kupchan Reference Kupchan2012). Consequently, public trust vis-à-vis political institutions and politicians entered a relentless decline (Klingemann and Fuchs Reference Klingemann and Fuchs1998). European countries were ensnared in a diffused ‘democratic deficit’ given that its ‘demos’ had pulled away from its political elites, and decision-making mechanisms questioning their system’s overall legitimacy. To contrast such a corrosion of the pillars of modern democracies, politicians themselves started addressing the sins via political engineering (for example, by means of constitutional changes deemed to increase decision-making, transparency and legitimacy, e.g. devolution in the UK, in Italy and in other countries), or via proper revolutionary changes such as those that occurred in soviet-controlled, Central-Eastern Europe, and also through forms of experimental decision-making (participatory democracy, e.g. popular budgeting, and so on).

A critical crack in the social juncture level was another sin to be cured. Such a social sin was a consequence of both economic and political failure. Political and economic dysfunction has increased people’s sense of insecurity: They have lost the perspective of a permanent, life-long, decently paid job, and they consider political elites as incapable of reversing enduring inequality. As a result, social trust, social capital and civic engagement started a dramatic decline across Europe and beyond (Klingemann and Fuchs Reference Klingemann and Fuchs1998; Putnam Reference Putnam2000; Wuthnow Reference Wuthnow1998). Moreover, such attitudes of mistrust and disaffection were soon to be politicised by astute political entrepreneurs cultivating vested interests in the promotion of polarised (and polarising) public attitudes towards social vulnerability.

Social enterprises made their ‘social debut’ in such a context of multiple, intertwined, cracks at critical economic, political and social junctures, and they began to be considered as a powerful remedy to address them all.

From the economic ‘sin’ point of view, social enterprises were considered an opportunity to reinvigorate, in Schumpeterian fashion, the spirit of entrepreneurial creativity typical of capitalism. Social enterprise’s ‘entrepreneurial’ dimension, although coupled with a social purpose, brought into the economy innovative ideas that could be used to engender economic development on a broader scale. Moreover, they offered opportunities of employment to people considered hard to employ through ordinary employment channels. Furthermore, social enterprise represented a different business organisational model, one in which employees themselves would take a central managerial position, a business model accommodating a range of societal interests (Spear et al. Reference Spear, Cornforth, Aitken, Defourny, Hulgård and Pestoff2014). Finally, most of the social enterprise jobs are ‘locally’ sourced: They are generated by a specific local setting and, as such, are sheltered from delocalisation risk.

From the political ‘sin’ perspective, social enterprises are perfectly aligned with discourses and practices of policy innovation: They represent, for example, one, if not the key, actor(s) (renamed as ‘stakeholders’) in the ‘new’ policy-making paradigm centred on governance as a replacement for government. The classical modus operandi of Western democratic systems was—and still is in part—based on policy decisions and implementation being a reserved domain of governmental (public) actors, with private actors providing advice, and eventually playing an ancillary role in policy delivery. Such a model of ruling democracy has met with increasing criticism for its poor capacity to fulfil people’s needs, once these have become more diversified and their beneficiaries’ pool broadened. But they have also been criticised for their sclerotised bureaucracies or their systemic bugs such as corruption and clientelistic dynamics (Della Porta and Vannucci Reference Della Porta and Vannucci1999, Reference Della Porta and Vannucci2016). A new model of ‘governance’ has emerged in which governmental and non-governmental actors are simultaneously activated (Piattoni Reference Piattoni2010) with the intention to make policy-making not only more efficient and effective in its capacity to deliver services, but also more transparent and accountable.

Through their participation in the co-production and co-management of public services (Brandsen et al. Reference Brandsen, Pestoff, Verschuere, Defourny, Hulgård and Pestoff2014; Pestoff Reference Pestoff2014), social enterprises participate in such a process of relegitimisation of devalued political institutions and policy processes via (supposed, at least) participatory forms of public decision-making. Therefore, policy-makers (at various levels of government) have a strong interest in supporting social enterprises as they become one of the few available tools to strengthen public action legitimacy at a time of scarce resources and increasing popular discontent.

From the social ‘sin’ viewpoint, social enterprises, putting people at the centre of the action, as well as with their emphasis on people engagement via organisational governance mechanisms are considered valuable remedies to contrast it with. From such a social-fabric reconstruction perspective, social enterprises are deemed to contribute reinvigorating social capital, civic and political engagement, and therefore provide new emphasis to the ‘demos’ underpinning the renovated spirit of democracy that goes with governance (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Sins and their social enterprises remedies

Within such a framework of mutually reinforcing counter-effects of political, economic and social cracks or sins, there is a domain in which social enterprises have played a pivotal role, and a domain which itself is paradigmatic to understanding contemporary (and earlier) societies: the welfare state, as an institutionalised way to address solidarity and to attempt remedying at least some of those sins. In the next section, we present our arguments in support of that, and we illustrate how the countries included in the special issue contribute to a better understanding of the social enterprise-democracy-welfare state nexus.

Social Enterprise Models and Welfare State Regimes: A Diachronic Perspective of State-Individuals Relationships

While the reader will learn from each contribution of this special issue about how a specific context and time generated its own ‘social enterprise flavour’, what we aim at in this introduction is to portray the commonalities existing among the various social enterprise traditions and models, and make of them a single, albeit differentiated, but comparable, mosaic-style phenomenon.

The framework we use across this special issue to present the picture of social enterprise diachronic evolution builds from connecting them with the welfare state. There are various reasons explaining this choice. Firstly, since its inception, the concept of social enterprise was intimately related with the welfare state: In Europe, it was meant to understand organisations acting to support employability of vulnerable people, and as such, as an organised form of solidarity which made the market economy permeable and adaptable to people with special needs (Borzaga and Santuari Reference Borzaga and Santuari2003; Defourny and Nyssens Reference Defourny and Nyssens2010). Since those earlier forms, social enterprise as a concept has kept evolving in connection with the welfare state, and today it indicates a range of organisations and businesses deploying services in health, social care, education, and employment, typical welfare state action domains. Secondly, by adopting the welfare-state lenses, we can trace the experience of current forms of social enterprises back to earlier decades and even centuries and periods when equivalent (to the welfare state action) forms of support for people’s well-being was put in place by church-related or charity-driven solidarity activities that shared with social enterprises the creation of community benefit and varying degrees of innovation and social transformation.

Furthermore, approaching social enterprises through welfare-state lenses has an additional advantage. It allows for capturing the changes occurring in the relationship between the state and individuals, or, between the state as a form of government and its demos (people). The welfare state has been developed as a social pact through which the state and its citizens have agreed to exchange support in case of need and protection from risks (state duty) against loyalty and obedience (citizens’ duty) (Ferrera Reference Ferrera2005). By so doing, welfare states have strongly contributed to processes of nation building by strengthening inter-individual bonds of state-regulated and organised solidarity (Keating Reference Keating, Adams and Robinson2002, Reference Keating2010). Within such a relation so central in modern democratic state-crafting, services operated by social enterprises have played and still play a salient role. Before the development of the welfare state, those organisational forms that we consider the ancestors of social enterprises, such as charity-inspired or religious organisations helping people with fewer resources or in vulnerable situations, have played a salient role in social and economic inclusion.

Therefore, social enterprises taken either in their current or in their ‘predecessor’ clothes are closely interlinked with changes and challenges experienced by welfare states in Europe. This special issue builds on new research developed in the framework of the EU FP7 Project EFESEIIS—Enabling the Flourishing and Evolution of Social Entrepreneurship for Innovative and Inclusive Societies—to capture the path dependencies and development trajectories of social enterprises in different welfare regimes in Europe. In particular, the special issue focuses on social enterprises’ developmental path in three types of welfare regime as defined by the classic work of Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) who classified liberal, conservative-corporatist and social democratic welfare regimes and revisions of his model further specifying a Southern European model of welfare state as a residual or sub-protective one (Ferrera Reference Ferrera1996; Ritter Reference Ritter2003; Gallie and Paugam Reference Gallie and Paugam2000). Thus, the first section of the special issue discusses social enterprises in conjunction with conservative-corporatist welfare regimes (Germany and France). The second section of the special issue turns to two cases of social enterprise development occurring in the context of residual or sub-protective welfare states (Italy and Poland, sharing a residual welfare state in which private institutions such as the Catholic Church and family play key roles). The third section discusses the case of social enterprise in the context of a hybrid welfare regime, one of former Communist countries, which offered some basic provision of protection to the entire population, though is now in a rapid transition towards a neoliberal market economy and a ‘liberal’ model of welfare state (Serbia). The final paper discusses the peculiar case of social enterprises in the context of a different type of hybrid welfare state, one which departed from its original ‘liberal’ model (the UK), mitigating it with policy measures that are more typical of a ‘social democratic’ welfare regime (the Scottish case).

Each paper discusses social enterprise development in connection with the welfare state adopting a cross-temporal approach. While consideration is given to the early inception phases, emphasis is placed on the last two decades, through which authors assess whether social enterprises have led to an expansion of their country’s welfare regimes, or whether they have replaced welfare state services, thereby providing evidence of public retrenchment from welfare state activities.

Before discussing the implications between welfare states and social enterprises in Europe, we need to consider another contextual dimension which is discussed in the special issue papers: the type of capitalism and economy system in place in each country. In fact, because social enterprises are social organisations that operate on the market, we need to introduce as well the type of market or the type of economy they are part of. In particular, in this special issue we consider the type of capitalism by adopting the classical distinction between corporatist versus pluralistic capitalist economies, in which the former are characterised by a set of established, organised social forces that mitigate conflict via negotiation, while the latter is characterised by an economic arena in which a plurality of actors compete in an open market, and where competition, rather than negotiation and consensus building, is the ruling principle (Schmitter Reference Schmitter1997).

Discussion

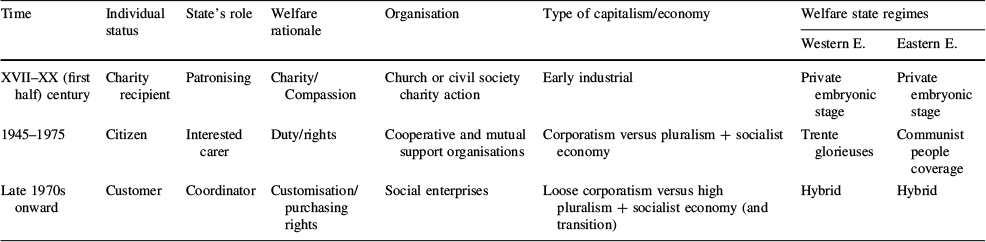

In this special issue, we conceptualise the relationship between social enterprises and welfare states as a diachronic evolution of the way, and of the rationale through which solidarity—as a set of policies and actions—has been organised by individuals and institutions. At each main temporal category, we find a specific pattern of organised solidarity that matches a given individual-state relationship and a given economic organisation of the society: Table 1 presents a synthesis of the key issues and findings discussed in the special issue.

Table 1 Social enterprises and the welfare state: evolutionary paths of organised solidarity in Europe

Time |

Individual status |

State’s role |

Welfare rationale |

Organisation |

Type of capitalism/economy |

Welfare state regimes |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Western E. |

Eastern E. |

||||||

XVII–XX (first half) century |

Charity recipient |

Patronising |

Charity/Compassion |

Church or civil society charity action |

Early industrial |

Private embryonic stage |

Private embryonic stage |

1945–1975 |

Citizen |

Interested carer |

Duty/rights |

Cooperative and mutual support organisations |

Corporatism versus pluralism + socialist economy |

Trente glorieuses |

Communist people coverage |

Late 1970s onward |

Customer |

Coordinator |

Customisation/purchasing rights |

Social enterprises |

Loose corporatism versus high pluralism + socialist economy (and transition) |

Hybrid |

Hybrid |

As Table 1 shows, up to the 19th century, in the early phases of mass industrialisation, action to address needs related to vulnerabilities emanated primarily from private organisations, largely created by religious groups and churches. In such a context, individuals were not yet ‘citizens’; therefore, the state allowed charitable action to happen by virtue of a sort of patronising approach to people and their needs. Religious organisations and early capitalist-philanthropists often coalesced to create associations supporting the poor, as happened in Germany (Obuch and Zimmer in this issue). In contrast, workers in secularised France, already in the early phases of industrialisation and urbanisation, organised among themselves (initially in secret since workers’ self-organisations were illegal until 1864) by creating workers cooperatives and small emergency funds to be mutually used in case of need, from which the famous French ‘mutuelles’ system originated (Chabanet in this issue). The conceptualisation of welfare-related services occurring in such an inception phase of market capitalism was still inspired by assistance criteria, while the insurance rationale that would characterise more modern welfare regimes was yet to happen. Therefore, early forms of social enterprise corresponded to such an understanding of welfare service support: They were private organisations providing help on the basis of compassion, mutual comradeship and/or altruism.

As soon as the development of the relationship between the individual and the state progressed towards a citizenship-based one, the state departed from a patronising approach and adopted a more ‘active carer’ role in which it started providing publicly funded protection schemes on a rights/entitlement basis. Early public social protection schemes emerged during this period when the rationale of organising welfare support shifted across European countries from assistance to insurance based. In such a new policy environment, social enterprise predecessors did not disappear from the welfare state arena: Actually, they consolidated their status through the acquisition of quasi-monopolistic positions as the state’s main partners in the delivery of publicly subsidised welfare services (as in the case of Germany where the large charity organisations such as Caritas and Diakonie expanded their range of action and their influence, but also the French and Italian cooperatives), or they kept their range of activities as an economic sector bound to complement the welfare state.

After the Second World War, when the relationship between state and individuals became one based on full citizenship—including in those areas of Europe that departed from democracy to embrace Communism—the welfare state reached its peak in terms of public provision (the so-called trente glorieuses meaning the period from 1945 to 1975 in which publicly funded welfare programmes experienced an unprecedented expansion), and again, civil society or charity-based welfare action continued to increase in importance. However, at this point in history, the paths between Western and Eastern Europe parted, with the former corroborating its democratic textures and its capitalist economies, and the latter embarking on the implementation of a socialist economic system, albeit with slightly different flavours. That was accomplished through a peculiar model of welfare state characterised by the overwhelming presence of public, government-led and implemented, actions (as was the case with the two former Communist countries discussed in this special issues, Poland and Serbia). Still, in both cases, welfare provisions were deployed on a rights- and entitlement-based model rather than on a charitable or compassion-led action, as had happened in earlier periods (although in Poland, the Catholic Church kept playing a pivotal role in welfare state service delivery).

In those post-war years, the state established itself as an interested carer, actively engaged in fulfilling its duty of protection towards rights entitled citizens rather than subjects. Early social enterprise roles in such a mature welfare phase developed along different paths according to the type of capitalism it was part of, be this a corporatist or a pluralist system (or, even more diversely in non-capitalist economies, such as in the socialist countries of Europe).

In neo-corporatist countries, such as France, Germany and to some extent Italy, in this special issue, a range of well-articulated religious or secular organisations like cooperatives and mutuelles accompanied public action expansion and did form a multifaced, but integrated constellation of actors whose impact was so relevant as to name those countries’ economies as ‘regulated systems of capitalism’.

In pluralistic market economies, a range of private organisations accompanied the development of public provision too, but these private organisations were, at first, more inclined to do business than to mutualise risks and coverage, and, secondly, they did not configure a unicum with public action, but acted more as independent, business-interested and business-run models of organisational structures. That is the case in the UK, for example, although Britain would be better understood as a pattern of different situations and paths, as the Scottish case analysis (Mazzei and Roy, in this issue) unveils. As part of the mature British welfare state, Scottish communities, especially those placed in remote areas, have continued using social enterprise predecessors to provide, for example, essential care or well-being services which a distant and sometimes politically distracted centralised public actor would forget to offer. And they would continue doing so when some years later, through devolution, part of the welfare state would be reorganised at a spatial-political level much closer to those remote areas (Alcock Reference Alcock2012; Mooney and Williams Reference Mooney and Williams2006).

In the immediate years after the Second World War, though, a third species of economic configuration appeared: the planned economies of the Communist countries. In these countries, although civil society life was tough, and its existence in forms other than ‘incognito’ almost impossible, civil society-based welfare-state action continued to exist through cooperatives devoted to supporting disabled people, in particular disabled war veterans, similar to what occurred in Serbia (Zarkovic Rakic et al., in this issue). Moreover, in Poland, the persistence of the underground social movement (Solidarnosc), together with the activism of the Catholic Church, contributed towards keeping civil society alive during the dictatorship years when any form of private organisation or collective action happening outside the state and party shadow was illegal (Praszkier et al., in this issue). Therefore, such an underground civic vigour contributed towards maintaining a vibrant ‘zeitgeist’ that would lead, later on, when the country shifted towards democracy and capitalist market economy, to the creation of social enterprises.

In the last three decades, the relationship between the state and the individual, as well as welfare states configuration and capitalist economies, has changed again. Therefore, the functions played by social enterprises—this time, appropriately called as such—have changed as well. Among the countries included in this special issue, a first general feature we should note is that socio-economic and political changes have occurred since the late 1980s leading to a convergence among what were very different countries in Western and Central-Eastern Europe. The former socialist economies have turned into liberal market economies imprinted by the same global capitalism that characterises Western European countries. Moreover, global neoliberal market rules have mitigated the effect and capacity of neo-corporatist contexts to reach consensus or agreement, while emphasising their pluralistic connotations (Streeck Reference Streeck2014).

Individuals, while maintaining their status as citizens, are considered by public authorities more and more in their consumer capacity, also when welfare state-related services are at stake. This attempt at ‘privatisation’ of individual-state relationships has resulted from three different issues: the reduction in public expenditure (states need to revise their budgets due to difficulties in borrowing and increased public debt, but also due to the adoption of pro-austerity policies); the further emancipation of citizens making individuals subjects, allowed to choose among alternative options of welfare support and provision; the increasing types of social risks uncovered by traditional welfare state action. In other words, both demand and supply dynamics have played a role in the transformation of welfare state services (Ascoli and Ranci Reference Ascoli and Ranci2002; Lorenz Reference Lorenz2013). People are sometimes in need and ‘entitled’ to choose between welfare services and providers as they would choose any other type of market product.

In this changed scenario, the state acts as a coordinator of services and a rule maker for private organisations, while social enterprises represent a relevant actor in a context of loose corporatism—where corporatism used to be the ruling context—or of intense pluralism—where pluralism happened to be the original scenario. In countries such as Germany, the traditional, established social organisations are challenged by new ‘lean’ forms of social entrepreneurship, more capable of competing along market rules than the traditional social enterprises which counted on state or public protection and privileged access to welfare state-related public resources (Obuch and Zimmer in this issue). Forced to operate within a proper competitive market, such new generations of social enterprises strengthened their business skills through innovative managerial, financial but also service tools (Ibidem).

In countries where social enterprises were enrooted in secularised, rights-based collective action, and the welfare state was a stronghold of the democratic construction, governmental actors have used social economy discourse and policies to enforce a neo-liberalisation agenda which otherwise would have met with strong social and, in part, political resistance. And therefore, the social enterprise sector has become a strongly politicised domain (as the French, Italian and in part Serb cases presented in this issue unveil).

The welfare state resulting from such a set of socio-economic and political changes is a hybrid one: On the one hand, it has been identified within the mix of public and private actors and called the welfare mix (Evers Reference Evers1995) which often combines innovation with protection capacity, while in other circumstances, the ‘mix’ has moved the pendulum towards a strong commercialisation of welfare services, with consequent reductions to its de-commodification capacity.

To Conclude

To conclude this introduction, we would like to draw attention to some of the aspects that emerge from the papers as potential issues for further thinking on social enterprises and welfare state regimes.

Firstly, we should consider how social enterprises have represented remedies for the economic, political and social sins through their engagement with the welfare state, as a policy institution set to address some of the sins’ effects. From the papers presented in this special issue, it appears that the expectations put on social enterprises for these to cure the sins exceeded the sector’s capacity in each of the sin ‘domains’. From the economic viewpoint, social enterprises have not been able to provide such a salient reservoir of jobs as was expected (and actually the quality of employment they have produced is considered a critical aspect) (Montgomery et al. Reference Montgomery, Mazzei, Baglioni and Sinclair2017). Still, their overall contribution to countries’ economic performance is not detrimental at all. Actually, in countries such as France or Italy (Chabanet in this issue, Biggeri et al., in this issue), the social enterprise sector has secured a significant amount of economic and financial resources, although not enough perhaps to mitigate the impact of disinvestment on other strategic economic sectors such as manufacturing.

Concerning the social enterprise sector’s impact on policy innovation, the results across the countries examined here do not provide a reassuring picture: The sector participation in the governance system is linked to specific episodic opportunities (e.g. at the sector law design phase), but the sector capacity to affect, for example, the neo-liberalisation of welfare-state or social-policy services has been very limited to say the least. Actually, in some circumstances, such as in former Communist countries (Zarkovic Rakic in this issue) the sector has facilitated the transition towards a neoliberal market economy and a ‘neoliberal’ welfare regime.

What happens to the social dimensions of social enterprises? Have they met the expectations? For sure social enterprises, as they are discussed in the papers gathered here, have offered opportunities to individuals they might not have had otherwise, and in this sense, they have represented an innovative way to partially cure the sin. Whether such action has been reflected on a large scale to change the generally declining social trust and civic engagement remains to be seen.

Finally, vis-à-vis the welfare state, what evidence is provided by these papers? They provide evidence suggesting that the sector has promoted genuine innovations in terms of increased capacity to reach specific vulnerable groups, as well as in terms of capacity to deliver new services. However, such an innovation has often been pursued in combination with public action retrenchment, sometimes helping to justify it, with consequences on people’s lives that still demand a full investigation.

Acknowledgements

The paper is based on research carried out in the framework of the project entitled: Enabling the flourishing and evolution of social entrepreneurship for innovative and inclusive societies (EFESEIIS), which received funding from the EU FP7 program (Grant No. 613179). Thanks to two anonymous reviewers for their useful comments on an earlier version of the paper.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The author is not aware of any conflict of interest.