Introduction

Non-partisan ministerial appointments – ministers without formal party affiliation at the time of their appointmentFootnote 1 – to Western European cabinets have been increasing since the mid-1970s (de Winter Reference De Winter, Blondel and Thiébault1991; Neto and Strøm Reference Neto and Strøm2006, 619).Footnote 2 Non-partisan ministers are even more frequently encountered in newly democratized former communist countries (Semenova Reference Semenova2020; Tavits Reference Tavits2009). In our sample of 30 European democracies, the mean proportion of non-partisan ministers was around 7% in the late 1940s, decreased to some 3% by the late 1960s, then increased to around 9% in the 1970s. After post-communist countries democratized, the proportion of non-partisan ministers jumped to 13% in the 1990s and further still to 19% by the start of the 2020s.

This trend potentially weakens the relevance of parties in government, which might have other consequences for democracy. Representative democracy was built on party representation, with parties traditionally providing a check upon their leaders. Weakening parties might enhance the control of their leaders and other members of the executive; it might weaken electoral ties and possibly weaken the political responsiveness of governments to the electorate. However, before we can meaningfully analyze its consequences, we need to understand what lies behind the increase in non-partisan ministers. We focus on three sets of factors: constitutional, institutional, and contextual. The first consists of the formal powers of heads of state and prime ministers (PMs). The second consists of conventions and understandings associated with those powers. The third concerns historical factors, notably the history of non-partisan appointments in countries that moved from authoritarian to democratic regimes. We concentrate upon the first two, using control variables for the third. Our analysis is not historical as such but rather concerns the specific constitutional and institutional framework within which non-partisans are appointed.

Numerous studies address the increase in non-partisan appointments, but without taking account of constitutional and institutional factors. They examine the increasing complexity of governance; the weakening of the party government model; executive ‘presidentialization’ (see various contributions in Costa Pinto, Cotta, and Tavares de Almeida Reference Costa Pinto, Cotta and de Almeida2018); presidential preferences (Tavits Reference Tavits2009); and authoritarian legacies (Semenova Reference Semenova2020). They also consider such appointments as strategies to reduce delegation problems (Martínez-Gallardo and Schleiter Reference Martínez-Gallardo and Schleiter2015; Neto and Samuels Reference Neto and Samuels2010), ‘neutralise politically-sensitive portfolios in coalition governments’, or ‘signal a non-partisan approach in a given sector of government in single-party cabinets’ (de Winter Reference De Winter, Blondel and Thiébault1991, 50). Non-partisan ministers are often appointed in circumstances of crisis (Brunclík and Parízek Reference Brunclík and Parízek2019; McDonnell and Valbruzzi Reference McDonnell and Valbruzzi2014). Additionally, the likelihood of non-partisan appointments may reflect the president’s popularity and legislative support (Camerlo and Pérez-Liñán Reference Camerlo and Pérez-Liñán2015; Lee Reference Lee2018). These explanations are not necessarily rivals to each other, nor to our analysis. A specific non-partisan minister might indeed have been chosen to neutralize political conflict within a coalition; what we address is why that is more likely to occur in some constitutional settings rather than others.

Our study differs methodologically in three important ways from earlier work examining the constitutional settings of non-partisan appointments. First, previous studies lump together different countries into what might broadly be termed ‘regime types’. Scholars normally distinguish between parliamentary and (semi)presidential settings, the latter characterized by popularly elected presidents (Protsyk Reference Protsyk2005a, Reference Protsyk2005b, Reference Protsyk2006; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2010; Tavits Reference Tavits2009). As others have noted, regime-type categorizations are not as rigid as generally assumed (Blondel Reference Blondel2015; Cheibub, Elkins, and Ginsburg Reference Cheibub, Elkins and Ginsburg2014; Fruhstorfer Reference Fruhstorfer2019). So we delve a bit deeper into the specific constitutional powers of heads of state and governments. For example, countries where the head of state rarely intervenes display a clear difference in non-partisan appointments.Footnote 3

Semi-presidential systems, which hold popular elections for presidents, who wield varying constitutionally granted powers, are thought to be more prone to intra-executive conflicts (Shugart and Carey Reference Shugart and Carey1992) than parliamentary systems, precisely because there are two executive loci, the president and the PM (Raunio and Sedelius Reference Raunio and Sedelius2020); and they do tend to have proportionally more non-partisan ministers than parliamentary systems (Neto and Strøm Reference Neto and Strøm2006; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009a, Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2010; Tavits Reference Tavits2009). Some studies make distinctions between presidential-parliamentary and premier-presidential systems (Shugart and Carey Reference Shugart and Carey1992) or even more complex typologies (Ganghof Reference Ganghof2018, Reference Ganghof2024). Again, we eschew these ways of lumping countries together. Instead, we demonstrate that specific powers and understandings underlie ministerial appointment processes, and it is they that are explanatory. Regime types are useful for some purposes, but they are constructs of various powers and legal relationships, and as such can hide the precise mechanisms that lead to different outcomes (Kaiser Reference Kaiser1997). Hence, our focus on specific powers that vary across and within regime types.

For similar reasons, we also eschew the use of indices of presidential powers. Previous studies adopt various indices of presidential power as proxies for presidents’ and PMs’ powers to appoint non-partisan ministers. For instance, Neto and Strøm (Reference Neto and Strøm2006) use the index of presidential legislative powers; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones (Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2010) an index of combined presidential powers; and Tavits (Reference Tavits2009) an index of legislative powers, an index of non-legislative powers, a combined index of presidential powers, and an index of presidential powers without a popular election variable. The literature offers numerous rival indices (e.g., Doyle and Elgie Reference Doyle and Elgie2016; Metcalf Reference Metcalf2000; Siaroff Reference Siaroff2003), but they are not accurate or fine-grained enough to model the link between constitutional settings and non-partisan appointments.

Researchers disagree about the precise relationship between the constitution and non-partisan appointments (see Tavits Reference Tavits2009, ch. 2) for both theoretical and methodological reasons. Neto and Strøm (Reference Neto and Strøm2006) regard presidents and PMs as roughly equal in negotiations over cabinet ministers; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones (Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009a, Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2010) consider each is constrained differently depending on the constitutional setting. We side with the latter but note that they do not demonstrate the specific constitutional powers leading to the appointment of non-partisans.Footnote 4 We demonstrate that constitutional rules, institutional factors, and historical legacies are all important factors in determining both whether non-partisan ministers are appointed at all and in what numbers.

Constitutional powers – particularly to dissolve parliaments – both constrain and enable significant actors in appointing non-partisan ministers. PMs are generally reluctant to appoint non-partisans, needing to realize the ambitions of their party in government. Popularly elected presidents, in contrast, are more open to non-partisan ministers. Where the PM has a freer hand in cabinet appointments and dissolution power over parliament, the political costs of non-partisan appointments are greater. So we should expect fewer cabinets to have any non-partisan ministers and lower numbers when they are appointed. Presidents vary in their ability to insist on non-partisan appointments depending on their constitutional powers. Presidents with greater power over government and parliamentary dismissal should have more cabinets with a higher magnitude of non-partisans.

Our second major contribution is demonstrating that the process of appointing non-partisan ministers needs to be modeled as a two-step structure. The first step is whether to appoint non-partisans at all. If so, the second step concerns how many. While the same mechanisms operate in both steps, they do not affect the tendency and the magnitude of non-partisan appointments in the same manner. Modeling the decision this way shows that 0s (the entire absence of non-partisan ministers in cabinets) are not a result of data generation but a process driven by factors other than 1s (the presence of non-partisans).

This fact is demonstrated by our third contribution: introducing to political science a novel method from financial economics: a two-step fractional response regression (Ramalho and da Silva Reference Ramalho and da Silva2009; Ramalho et al. Reference Ramalho, Ramalho and Henriques2010, Reference Ramalho, Ramalho and Murteira2011). Using this method enables us to keep these two processes apart. We apply this novel method to a unique dataset on non-partisan appointments in 957 cabinets in 30 European democracies from 1945 to 2024.

Powers of the agents

Cabinet formation in parliamentary and semi-presidential systems

Delegation models are the most prominent framework for analyzing ministerial appointments, highlighting the nature of principal–agent relationships within the government. In parliamentary systems, cabinets generally rely upon parliamentary support, with delegation typically managed by political parties (Müller Reference Müller2000). MPs are subject to party discipline and, importantly, fulfill a gatekeeper function for party leadership and cabinet positions. Party leaderships negotiate the selection of the PM when forming coalitions (Kam et al. Reference Kam, Bianco, Sened and Smith2010; Saalfeld Reference Saalfeld2000). The PM, in turn, selects cabinet ministers (Strøm et al. Reference Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008), usually in consultation with the other coalition party leaders (Bergman et al. Reference Bergman, Bäck and Hellström2021, Reference Bergman, Ilonszki and Hellström2024).

Political parties are often indirectly involved in ministerial selection and in the distribution of cabinet portfolios (Dowding and Dumont Reference Dowding and Dumont2009; Saalfeld Reference Saalfeld2000), because parliaments and party organizations are where the ex ante screening of candidates mostly takes place. Such screening is crucial because ex post mechanisms of solving delegation problems (such as a minister’s dismissal) may be unavailable or even endanger coalition survival (Dowding and Dumont Reference Dowding and Dumont2009). Consequently, partisanship and parliamentary experience are considered important factors for cabinet recruitment in Europe (de Winter Reference De Winter, Blondel and Thiébault1991; Huber and Martínez-Gallardo Reference Huber and Martínez-Gallardo2008; Martin Reference Martin2016; Semenova Reference Semenova, Costa Pinto, Cotta and Tavares de Almeida2018). Moreover, parties want their partisans in the cabinet so they can keep tabs on their coalition partners (Thies Reference Thies2001).

In semi-presidential systems, the chain of delegation from voters to the PM and her cabinet is supplemented by an additional chain of delegation from voters to a popularly elected president. Cabinets are thus responsible to two principals: the parliament and the president (Elgie Reference Elgie and Elgie1999, 13). This system changes the role of political parties in cabinet appointments. As in parliamentary systems, the delegation chain remains in the hands of political parties, and party leaderships control cabinet appointments. But two additional actors are involved: the president, elected in a nationwide constituency, and her party, whose members are elected in individual constituencies representing a fraction of the president’s electorate (Linz Reference Linz, Linz and Valenzuela1994). Differences in electoral support between the president and her party may cause the interests of these actors to diverge. Divergence between presidential and the governing coalition’s interests increases the probability of intra-executive conflict (Protsyk Reference Protsyk2006; Shugart and Carey Reference Shugart and Carey1992). Divergence between the interests of the president and her party increases the probability of intra-party dispute, even in government (Carey Reference Carey2007; Samuels and Shugart Reference Samuels and Shugart2010). Presidents try to overcome such problems by building coalitions across party lines or by presenting themselves as non-partisan actors (Neto and Strøm Reference Neto and Strøm2006).

Researchers disagree on precisely how presidents influence cabinet formation and for what purpose. Some argue that presidents are potent actors with the leverage to negotiate cabinet composition by proposing candidates for specific portfolios (Neto and Strøm Reference Neto and Strøm2006; Shugart Reference Shugart, Rhodes, Binder and Rockman2006, 358). Often, such candidates are non-partisan because they are considered natural presidential allies to help realize presidential preferences (Tavits Reference Tavits2009). Others argue that presidents cannot negotiate cabinet composition because the PM’s appointment is already the outcome of the parties’ negotiation, and party leaderships determine cabinet positions (Protsyk Reference Protsyk2005b; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009a). Nevertheless, the president is more likely to nominate non-partisans than the political parties (Schleiter and Morgan-Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009a, Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2010).

Constitutional powers and cabinet formation and termination

To understand presidential effects on non-partisan appointments, we need to examine the constitutional powers assigned to all political actors and assess their individual effects on the presence of non-partisan ministers. It is evident that dividing European political systems into just two – parliamentary and semi-presidential – is not sufficient, because it misses another type – constitutional monarchies. These are often subsumed under parliamentary systems but possess distinct features, as we see below.

In parliamentary systems, the parliament can terminate cabinets through a vote of no confidence (Lupia and Strøm Reference Lupia and Strøm1995). Presidents in European parliamentary systems are usually considered weak compared to their semi-presidential counterparts (Grimaldi Reference Grimaldi2023a, Reference Grimaldi2023b; Shugart and Carey Reference Shugart and Carey1992), but nevertheless have potentially key constitutional powers. First, they usually have the power to appoint PMs. Of course, this power is limited, since the executive is selected from the parliament. But it is not completely hollow, as various examples of such interventions demonstrate. For instance, in Italy, in 2012, President Napolitano refused to appoint the leader of the Partito Democratico, Pier Luigi Bersani, as PM, despite his majority in the lower chamber (though not in the Senate); while in 2018, President Mattarella refused to appoint as PM someone he was not confident could ‘muster at least a razor-thin parliamentary majority’ (Valbruzzi Reference Valbruzzi2018, 461, 462–3).

In some parliamentary systems, presidents can unilaterally dissolve parliament. For instance, in pre-1986 Greece, presidents could dissolve the parliament ‘if there were indications of popular discontent’ with it (Gerapetritis Reference Gerapetritis, Featherstone and Sotiropoulos2020, 158). In Italy, President Cossiga dissolved parliament when Socialists and Christian Democrats disregarded an informal agreement about an effective alternation of the PM position (Grimaldi Reference Grimaldi2023b, 190); and Presidents Leone and Pertini, in 1972 and 1979, dissolved parliament when alternative governments failed to win a confidence vote (Grimaldi Reference Grimaldi2023b, 194). Undoubtedly, heads of state have on occasion used their powers of dissolution to the advantage of their own party, but it would be unjust to argue that Italian presidents use their dissolution power lightly; in numerous cases, they have actively tried to prevent dissolution (Pasquino Reference Pasquino2012, 853). Clearly, such powers of dissolution in parliamentary systems are an essential instrument of cabinet termination and must be considered when discussing non-partisan cabinet appointments.

Constitutional monarchies also grant distinct and important powers to their PMs and governments. The PMs in these systems often have discretionary powers to dissolve parliament – for example, in Denmark, Spain, and the UK.Footnote 5 This instrument is considered a counterweight to the parliamentary majority’s dismissal power (Strøm and Swindle Reference Strøm and Swindle2002, 576). Parliamentary dissolution allows the PM to ‘reset the clock’ and start a fresh term in office – provided they correctly predict the electoral outcome (Balke Reference Balke1990, 202). Sometimes a government is forced to call new elections: for example, when coalitions are unstable or as a minority government (Balke Reference Balke1990, 203). For instance, in 1974, the Danish PM, leading a minority government, called an early election after his policy proposal failed to achieve a parliamentary majority (Becher and Christiansen Reference Becher and Christiansen2015, 652). Comparative studies have shown that if the PM can dissolve the parliament at their discretion, dissolutions occur more often than when they require agreement among various actors or are in the president’s hands (Schleiter and Morgan-Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009b).

Another feature of constitutional monarchies is that the power to dissolve the parliament may be delegated to governments collectively, as it is, for example, in Luxembourg and the Netherlands (Goplerud and Schleiter Reference Goplerud and Schleiter2016). Because constitutional monarchs (like some other heads of state) are non-partisan, they lack the power to dissolve the parliament at their own discretion, but act on the advice of the PM and parliament (Schleiter and Morgan-Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009b, 499). While some monarchs – the UK’s for example – formally possess the power to dissolve parliament against the PM’s will, to exercise it would cause a constitutional crisis, potentially threatening the monarch’s position.Footnote 6

Finally, in semi-presidential systems, cabinets can be terminated through a vote of no confidence (Lupia and Strøm Reference Lupia and Strøm1995). Like their parliamentary counterparts, presidents in semi-presidential systems have their (constrained) say on the PM’s candidacy. For instance, in 2019, the Austrian president appointed the president of the Constitutional Court, Brigitte Bierlein, as PM after the previous government lost a vote of no confidence (Grimaldi Reference Grimaldi2023b, 180).

Popularly elected presidents have greater discretionary powers than their indirectly elected counterparts. They are often granted the power to dissolve parliament – for example, in Austria, Iceland, Portugal, and post-1958 France (Table 1). Finnish presidents lost this power in 1991 but had actively used it previously. President Kekkonen (1956–1982) ‘selected prime ministers, pushed parties into coalitions, forced governments to resign, appointed non-partisan presidential cabinets, and dissolved parliaments’ (Nousiainen Reference Nousiainen2001, 101). In Iceland, until 1991, the president was very active in bringing about majority coalitions by threatening the PM with appointing a non-partisan cabinet led by a presidential appointee (Kristjánsson and Indridason Reference Kristjánsson, Indridason, Bergman and Strom2011). Portuguese presidents have also used their dissolution power frequently. Austria, though, is an outlier: its presidents have never used their dissolution power (Grimaldi Reference Grimaldi2023b, 181).

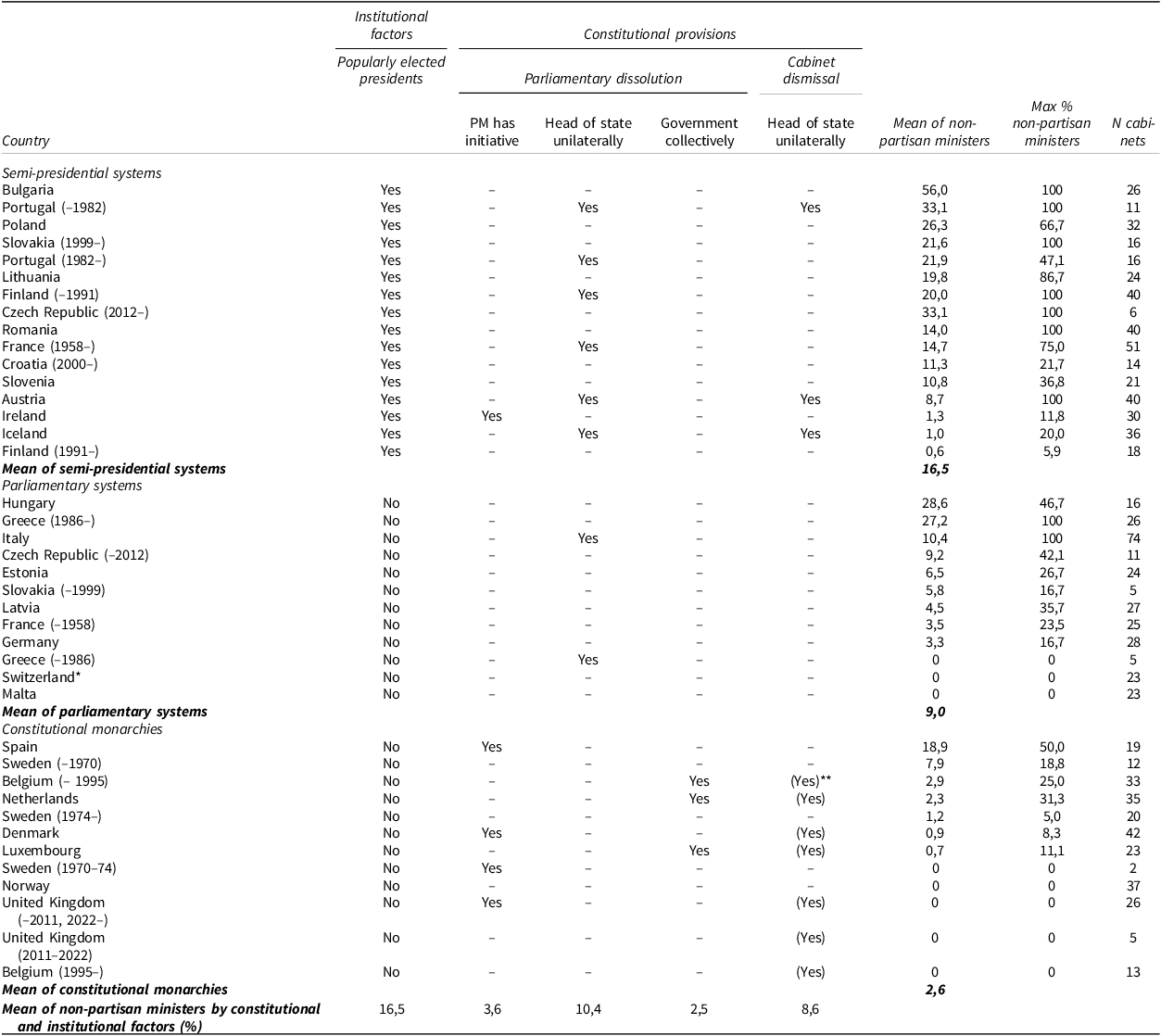

Table 1. Constitutional rules and the proportion of non-partisan ministers in 30 European democracies, 1945–2024 (percentages)

* Switzerland, strictly speaking, is not a parliamentary democracy. The Federal Council has seven members elected by the Federal Assembly, chaired by the President of the Swiss Confederation, who has no greater powers than other members. Institutionally, this resembles a parliamentary democracy more than our other categories. No results are affected if we exclude Switzerland from the analysis.

** Although hereditary heads of state often have constitutional powers to dismiss the cabinet, their constitutional status ensures that they cannot use them (we therefore put these powers in parentheses).

Source: authors’ classification and calculations.

In some semi-presidential systems, the presidents also have discretionary power to dismiss the cabinet (that is, to dismiss the PM) – in Austria, Iceland, and (with different qualifications at different times) Portugal, for example. Again, Austrian presidents have never used this power over our observation period. In Portugal, the 1976 constitution granted the president the power to force the cabinet to resign by withdrawing his confidence (Neto and Costa Lobo Reference Neto and Costa Lobo2009, 238), although that power was somewhat tempered in 1982 by constitutional revision in 1982 (Grimaldi Reference Grimaldi2023b, 176; Neto and Costa Lobo Reference Neto and Costa Lobo2009, 240). It is important to underline that, in European democracies, the president’s power to dismiss the cabinet is rare and, if present, goes together with the president’s dissolution power (Table 1).

Descriptive analysis

So, the powers of the major actors vary across different institutional and constitutional settings. The complexity of these differences suggests that understanding the precise rules governing the powers of PMs and heads of state might provide deeper insight into the mechanisms governing non-partisan appointments than trying to explain them in terms of regime type. The data on non-partisan ministers also suggest variation in the processes that lead to their appointment. While the average proportion of non-partisan ministers in 30 European democracies is around 10%, there is a considerable cross-country variation in the magnitude of non-partisan cabinet appointments (see Table 1). Descriptively, we find four significant patterns.

First, constitutional monarchies tend to have the lowest (approximately 3%) and semi-presidential systems (i.e., those with popularly elected presidents) the highest (around 17%) proportion of non-partisan ministers. This supports previous findings (Tavits Reference Tavits2009).

Second, there is considerable variation in the proportion of non-partisan ministers within each type of political system. For instance, among systems with popularly elected presidents, Bulgarian cabinets contain as many as 56% non-partisan ministers, and Irish and Icelandic cabinets only around 1% (Table 1, Mean % of non-partisan ministers column). In parliamentary systems, non-partisan ministers have been well represented in Hungarian and post-1986 Greek cabinets (approximately 29% and 27%, respectively), but there have been none in Maltese cabinets. Finally, Spanish cabinets represent an outlier among constitutional monarchies (around 19% non-partisan ministers, compared to none in the UK).

Third, Table 1 shows the variation in the proportion of non-partisan ministers within systems that have undergone substantial constitutional changes in the competencies of prominent political actors. For instance, in Finland, the 1999 constitutional amendment removed the president’s power to dissolve the parliament. The proportion of non-partisans in Finnish cabinets, previously as high as 20%, dropped to 1% thereafter. However, in Greece, the 1986 removal of the president’s power to dissolve the parliament had the opposite effect. Beforehand, there were no non-partisans in Greek cabinets; afterwards, the proportion reached almost 27%. One reason for this is that, despite their formal powers, Greek presidents were largely viewed as ceremonial, and, as mentioned above, their power of dissolution relied upon there being popular discontent with parliament (not, note, with government).

Fourth, countries also vary in the magnitude of non-partisan appointments (Table 1, Max % of non-partisan ministers column). Spain has been mentioned as an outlier among constitutional monarchies; among parliamentary systems, Italy is often cited as a country with many non-partisan technocratic cabinets (McDonnell and Valbruzzi Reference McDonnell and Valbruzzi2014), but in fact the overall proportion of non-partisans in Italian cabinets equals the European average.

These substantial variations reveal complex relationships among the type of political system, constitutional provisions, and appointing non-partisan ministers. Our empirical analysis is designed to disentangle these complexities. First, we look at the constitutional rules we believe lie at the heart of non-partisan appointments, developing some hypotheses; then we turn to our statistical analysis.

Non-partisan ministers and constitutional and institutional rules: hypotheses

To appoint or not to appoint?

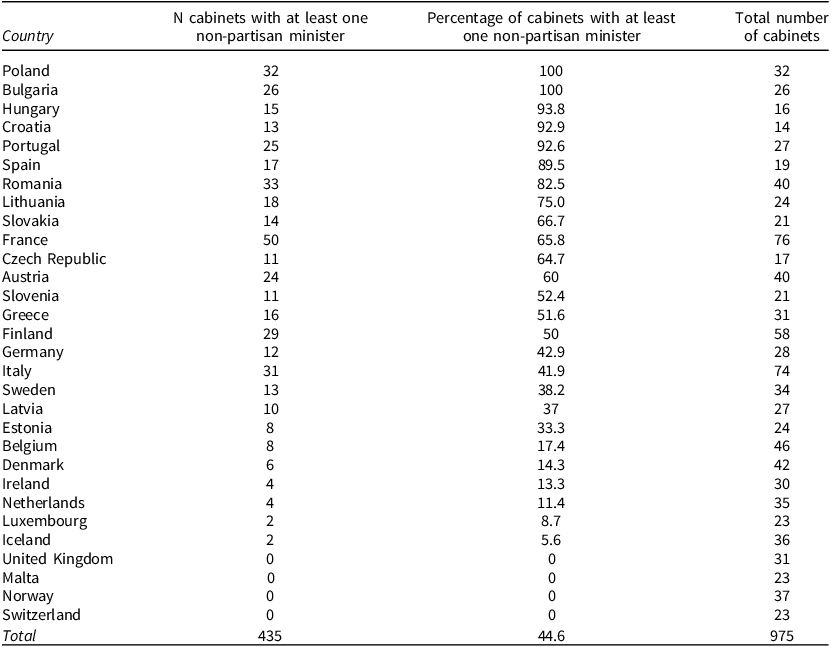

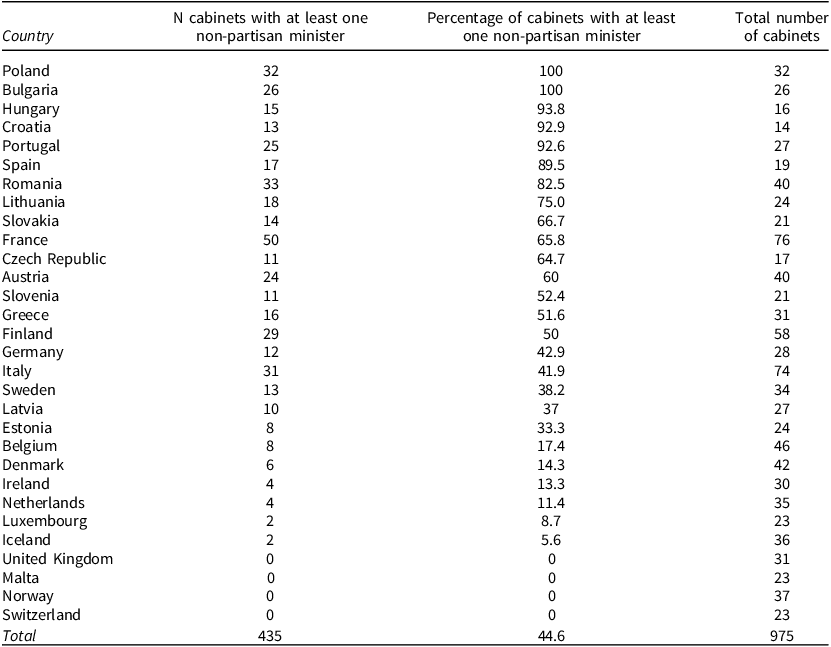

On average, 45% of all European cabinets include at least one non-partisan minister (Table 2). However, there are substantial cross-country differences. For instance, in the cabinets of former communist countries and in Portugal and Spain, non-partisan ministers are the rule rather than the exception. Non-partisan ministers are often appointed to Austrian, Finnish, French, and Greek cabinets; they are less common in the cabinets of Denmark, Sweden, and the Benelux countries; and they are nonexistent in the cabinets of Malta, Norway, Switzerland, and the UK.

Table 2. Cabinets with at least one non-partisan minister, European democracies, 1945–2024

Source: authors’ calculations.

The problem for analysis is that in two countries, all cabinets have had at least one non-partisan minister, but in four countries, no cabinets at all have had any non-partisan ministers. For effective analysis, therefore, the cabinet rather than the country needs to be our observation unit. The question we address is how to model these 0s (the absence of non-partisan ministers) across all cabinets. Are they the result of a data-generation process or of a process distinct from that of 1s (the cabinets including non-partisan ministers)? Consider smoking. While the cost of cigarettes should affect how many cigarettes someone smokes (and might lead some to desist altogether), many people will not smoke no matter how cheap cigarettes are. Non-partisans’ absence (i.e., 0s) results from a non-random self-selection process. For instance, in the UK, while there is no constitutional bar to appointing non-parliamentary ministers, ministers have always served in one of the two houses. PMs have adopted the practice of creating life peers in the non-elected House of Lords to enable their appointment as cabinet ministers (Kelly Reference Kelly2023, 13–15); many of these are former members of the House of Commons in any case, and all are partisan. In Malta, the party system is highly polarized and dominated by just two parties (Bulmer Reference Bulmer2014), leaving no space for non-partisans. Thus, whether to appoint or not appoint non-partisan ministers is a separate decision from how many to appoint. Not appointing can be a conventional response to longstanding understandings, though this is highly related (though not exclusively) to being constitutional monarchies, where the number also tends to be low in countries where they are sometimes appointed.

As we describe in detail below, we model the appointment of non-partisan ministers in European democracies as two related but distinct processes: the first is the decision to appoint non-partisan ministers or not; the second (for those countries that decide to appoint) is how many non-partisans to appoint (Ramalho and da Silva Reference Ramalho and da Silva2009; Ramalho et al. Reference Ramalho, Ramalho and Murteira2011). The first stage models the 0 cabinets, where no cabinet has non-partisan ministers. While our observations are cabinets, the determinants that we are modeling are the precise powers of the two key actors, PMs and heads of state. Since we are also interested in the magnitude of those non-partisan appointments, at the second stage, we model the proportion of non-partisans from above 0 (the proportion of non-partisans in relation to all ministers in the cabinet over time) to 100 (where all cabinet ministers are non-partisans). We still assume that both stages are affected by the same constitutional and institutional factors: that is, those factors that shape the diverging preferences of PMs and presidents and party control, but we model their effects separately. We shall explain our hypotheses for, first, the likelihood of appointing non-partisan ministers and, second, the magnitude of their presence; then we turn to a more detailed description of our models before providing the analysis.

The likelihood of non-partisan appointments: hypotheses

Where there is only one delegation relationship, there should be few, if any, non-partisan ministers, because the role of political parties is expected to be dominant. Where the leaders of winning political parties negotiate over the premiership and candidates for cabinet, we should expect a low tendency to appoint non-partisan ministers. Doing so would mean relinquishing party control of those cabinet portfolios. Moreover, while the power to dissolve parliament granted to the PM can be used to discipline parliament, it is unlikely that the PM would use this threat to force party leaders to accept non-partisan ministers. In contrast, where two delegation relationships exist, political parties have weaker control over portfolios. Popularly elected heads of state in semi-presidential systems have greater incentives to promote non-partisan ministers, because their interests may diverge from those of their parties in parliament.

Therefore, regardless of other system characteristics,

-

Popularly elected heads of state are more likely to make non-partisan appointments (H1.1)

-

Where the PM has the power to dissolve parliament, there is a lower probability of non-partisan appointments (H1.2)

Neto and Strøm (Reference Neto and Strøm2006) argue that the head of state’s power to affect government terminations should be positively related to the president’s bargaining power vis-à-vis the PM, particularly in semi-presidential systems. In the cabinet appointment game, the president either accepts the PM’s candidates or ‘there is a parliamentary dissolution, precipitated by whatever procedure the constitution prescribes’ (Neto and Strøm Reference Neto and Strøm2006, 628). Schleiter and Morgan-Jones (Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009a, 666) correctly observe that the PM should not be considered the president’s bargaining partner, because the PM is the outcome of bargaining among coalition parties. Presidential powers in semi-presidential systems vary enormously (Doyle and Elgie Reference Doyle and Elgie2016; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009a, 669), but previous studies have not examined the effects of individual presidential powers; rather, they have used a total number of presidential powers as an index (Schleiter and Morgan-Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009a; Tavits Reference Tavits2009), an index of the president’s powers and the presidential discretion to dismiss cabinets (Schleiter and Morgan-Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2010), or an index of the president’s legislative powers (Neto and Strøm Reference Neto and Strøm2006).

Consider what happens when the president proposes a non-partisan cabinet minister. The PM and leaders of the coalition parties could either negotiate another candidacy or reject it (Neto and Strøm Reference Neto and Strøm2006). If the president can dissolve the parliament discretionally, threatening the survival of both the PM and the coalition, the president might get his way. Of course, the president would not threaten dissolution lightly, but he can control the timing to benefit his supporters in the subsequent elections (Schleiter and Morgan-Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2018). A deterrent to opportunistic dissolutions would be the anticipated response from voters and consequent electoral punishment (Schleiter and Tavits Reference Schleiter and Tavits2018). However, compared to PMs, the possible negative effects on the president’s re-election are expected to be marginal, because term limits are entrenched in all European constitutions (Elkins et al. Reference Elkins, Ginsburg and Melton2025). Moreover, many presidents in Europe, either because of constitutional requirements or informal expectations, relinquish their party membership once elected. Becoming non-partisan themselves allows presidents to increase their appearance of neutrality and thus reduce electoral backlash against their parties should they exercise their dissolution power.

Therefore,

-

When the president has the power to dissolve the parliament, there will be a higher tendency to make non-partisan appointments (H1.3)

The magnitude of non-partisan appointments: hypotheses

We have argued that various constitutional and institutional factors affect the probability of there being non-partisan appointments. We now turn to the number (magnitude) of such appointments. The only established finding here is that semi-presidential systems have more non-partisan ministers than parliamentary ones (Neto and Strøm Reference Neto and Strøm2006; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009a, Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2010; Tavits Reference Tavits2009). However, some comparative studies on non-partisan ministerial appointments in Eastern Europe have pointed out that where popularly elected presidents appoint non-partisan ministers, it is likely to be to the most prestigious portfolios and in the policy areas particularly important to the president – foreign affairs, defense, and finance (Semenova Reference Semenova, Costa Pinto, Cotta and Tavares de Almeida2018, Reference Semenova2020). We do not consider these findings incompatible, as presidents may want to fill the most crucial positions with non-partisans as a minimum. If presidents have leverage over cabinet termination, they do not object to further non-partisan appointments. It is also plausible to expect few non-partisans in systems where the PM may dissolve the parliament because of the greater power of political parties over appointments. Table 1 supports this expectation.

Given these considerations, we expect that

-

The magnitude of non-partisan appointments will be higher under popularly elected heads of state (H2.1)

-

The magnitude of non-partisan appointments will be lower in systems where PMs can dissolve the parliament (H2.2)

-

The magnitude of non-partisan appointments will be higher in systems where presidents can dissolve the parliament (H2.3)

Controls

Using the literature on coalitions, semi-presidentialism, and ministerial recruitment, we employ a set of control variables. The type of cabinet affects the leeway of PMs to appoint ministers. PMs have greater power in the majority than in the minority cabinets (Huber and Martínez-Gallardo Reference Huber and Martínez-Gallardo2008), while the interim character of caretaker cabinets is likely to boost the power of PMs to appoint non-partisans (Neto and Strøm Reference Neto and Strøm2006; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009a). Therefore, we use as controls the binary variables Minority and Caretaker cabinet. Neto and Strøm (Reference Neto and Strøm2006, 627–8) argue that presidents are more likely to appoint non-partisan ministers in cohabitation: that is, when they are forced to negotiate cabinets with the opposition instead of their own party. We include the variable Cohabitation, coded as 1 if the president’s party is not in the coalition. We also control for bicameralism, which increases cabinet survival if the coalition has an upper-chamber majority (Druckman and Thies Reference Druckman and Thies2002). Although the cabinet never depends on upper-chamber approval, conflictual relations between the chambers may hamper the government’s policy output, so it may try to nominate non-partisans to reduce potential conflict. We use the binary variable Bicameralism to test this assumption.

Parliamentary factors may also increase the probability of recruiting non-partisans. Fractionalized parliaments tend to produce highly heterogeneous and fragile coalitions (Warwick Reference Warwick1994). In these circumstances, PMs may prefer to nominate non-partisans to decrease the likelihood of intra-cabinet ideological conflict among partisan ministers (see Neto and Samuels Reference Neto and Samuels2010, 14). In contrast, high fractionalization within the governing coalition should lead to fewer non-partisan ministers, because the PM’s freedom will be significantly restricted by coalition partners. The variables parliamentary fractionalization, measured as the effective number of parties (Laakso and Taagepera Reference Laakso and Taagepera1979), and cabinet fractionalization, calculated as the number of coalition partners, are used as controls.

Certain features of party systems might be important for cabinet appointments. Some electoral systems produce more independents, who might become cabinet ministers. More proportional electoral systems have fewer independents (Matland and Studlar Reference Matland and Studlar2004), reducing the likelihood of non-partisans featuring in cabinets. Another pertinent feature is party institutionalization, which defines how stable parties are, whether they value the party’s long-term goals over elites’ short-term preferences, and how well they are connected to and can mobilize voters (Bizzarro et al., Reference Bizzarro, Hicken and Self2017, 4). We expect that if party-system institutionalization is low, non-partisan appointments will occur more often, because overall party control over political positions will also be low. We use the V-Dem Party Institutionalization Index (Bizzarro et al., Reference Bizzarro, Hicken and Self2017) as a control.

Finally, we include the variable Age of Democracy, which distinguishes between established democracies (such as the UK) and democracies of the second and third waves (such as Italy, Spain, and post-communist Eastern Europe) (Huntington Reference Huntington1991). We coded it as 1 if the country is a third-wave democracy and 0 otherwise. We expect third-wave democracies to have less institutionalized party systems and weaker links between voters and political parties. Consequently, political parties will have less control over cabinet appointments, and, in the case of non-partisan appointments, voters will refrain from punishing political parties for their lack of control over specific policy areas.

Data and method

The analysis is based on a unique dataset measuring the proportion of non-partisan ministers in each of 975 cabinets existing in 30 European democracies from 1945 until 2024. The data covers Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland,Footnote 7 and the UK. The unit of observation is a cabinet in a country. We analyze 975 cabinets since 1945, or from the first democratic election (for example, the 1970s in Spain or the early 1990s in post-communist countries).

As shown above, there are some cabinets with no non-partisan ministers and some countries in which non-partisan ministers are present in every cabinet. In our sample, non-partisan ministers were present in 44.6% of all cabinets (Table 1). The magnitude of non-partisan ministers in each cabinet also differs, with cabinets including no non-partisan ministers, just one non-partisan minister, cabinets consisting entirely of non-partisan ministers, and anything in between. For instance, in our sample, there are 32 cabinets (some 3%) consisting of non-partisan ministers only.

In econometric terms, we have a non-random process of non-partisan presence in cabinets. The magnitude of non-partisan presence is observed on the interval between 0% (no non-partisan ministers) and 100% (cabinets with non-partisans only). As such, this proportion of non-partisan ministers in the cabinet is a bounded variable, because a cabinet cannot contain a negative proportion of non-partisans: the lower boundary is 0. Nor can it have more than 100%: the upper boundary. Moreover, there is a non-trivial accumulation of values on one of the boundaries (in our case, 0s, i.e., no non-partisan ministers in cabinets).

How can one model such data? The first method is to ignore the bounded nature of the dependent variable (the proportion of non-partisans in cabinet) and accumulation of values at the boundary (0s), assume a linear conditional mean model, and use an OLS regression. However, an OLS regression is unsuitable for fractional data because the predicted values can lie outside the unit interval (Papke and Wooldridge Reference Papke and Wooldridge1996, 619–20; Ramalho et al. Reference Ramalho, Ramalho and Murteira2011, 21). In other words, predicted values might be over 100% of non-partisan ministers in the cabinet.

Another method could be to use a Tobit regression. Again, the choice of this model is criticized by econometricians: while it is appropriate to describe the data censored in the standard unit interval [0, 1], its application to the data defined in this interval only is difficult to justify. In our data, 0s do not represent data censoring but are a natural result of the data process itself – that is to say, we have no a priori reason for excluding some countries (for more statistical details, see Ramalho et al. Reference Ramalho, Ramalho and Henriques2010, Reference Ramalho, Ramalho and Murteira2011, 22).

A third method is to use a beta fractional regression model (Ferrari and Cribari-Neto Reference Ferrari and Cribari-Neto2004, 799). However, this type of regression cannot handle the dependent variable’s observations at one or both extreme boundaries of 0 (0%) and 1 (100%).

Because we have our dependent variable values at both extreme boundaries (0% non-partisans in the cabinet and 100% non-partisans in the cabinet) and we have an accumulation of 0s in our data, we cannot use a beta regression. Ramalho et al. (Reference Ramalho, Ramalho and Murteira2011, 25) show that a two-step (or two-part) fractional response model is the most suitable method to analyze such data (see also Ramalho and da Silva Reference Ramalho and da Silva2009 and Ramalho et al. Reference Ramalho, Ramalho and Henriques2010 for application of such models in financial economics). Methodologically, the regression model has two equations.Footnote 8 The first step is a discrete choice model, which describes whether y is a boundary observation. The first equation is conducted using the entire sample of the data. In the second step, only for those cases with positive outcomes – i.e., where 0 < y ≤ 1 – a conditional mean fractional response model is employed (Ramalho and da Silva Reference Ramalho and da Silva2009; Ramalho et al. Reference Ramalho, Ramalho and Henriques2010, Reference Ramalho, Ramalho and Murteira2011). We use the first step to model the 0 cabinets (i.e., cabinets with no non-partisan ministers). Without this first step, the fractional response regression model will simply discard the 0 cabinets (Papke and Wooldridge Reference Papke and Wooldridge1996, 621). Therefore, we lose that information on the 0 cabinets and model the proportion of non-partisan ministers in those cabinets where these ministers are present.

For our analysis, the first-step equation models the presence of non-partisan ministers in all 975 European cabinets. The dependent variable is the presence of non-partisans in the cabinet (1 if at least one non-partisan minister is present and 0 otherwise). As advised (Ramalho et al. Reference Ramalho, Ramalho and Murteira2011), we use the Ramsey RESET test to check possible misspecifications of the functional form. This test suggests the logit functional form is preferable for the binary part of the two-step fractional response regression. We therefore use a fractional response logit model for estimating the first-step equation on the presence of non-partisan ministers in cabinets.

At the second step, we exclude all the cabinets with no non-partisan ministers (i.e., we selected only cases with positive outcomes) and estimate a conditional mean fractional response model. Thus, the two steps are not entirely independent of each other, as the first step determines which observations are included in the second. At the second-step equation, our dependent variable is the proportion of non-partisan ministers out of all ministers appointed to each cabinet. For instance, in the first cabinet of Romanian PM Dăncilă (2018–19), one minister out of 28 was a non-partisan at the time of appointment. Thus, the value of the dependent variable for this cabinet will be 3.6%. In contrast, the cabinet headed by Austrian PM Bierlein (2019–20) consisted of non-partisans only, yielding a value for the dependent variable of 100%.

Note that for a two-step fractional response regression, the dependent variable must be bounded on the standard unit interval, i.e., 0 ≤ y ≤ 1 (see Papke and Wooldridge Reference Papke and Wooldridge1996; Ramalho et al. Reference Ramalho, Ramalho and Murteira2011), so the percentage value is divided by 100. In our examples, the value of the dependent variable for the Dăncilă cabinet will become 0.036 (3.6% divided by 100), and the value for the Bierlein cabinet will be 1 (100% divided by 100). The second step requires this process to ensure that both the dependent variable and, most importantly, the predicted values obtained via postestimation commands (such as margins) are bounded to the interval 0 < y ≤ 1. Otherwise, it will be possible to get predicted values for non-partisans of less than 0 or more than 100%.

To check for misspecifications of the functional form of our fractional response model, we use the P-Test (Ramalho et al. Reference Ramalho, Ramalho and Murteira2011). It shows that the log-log functional form is preferable for the fractional part of the regression for our data. For both parts of the equation (i.e., the binary one in the first step and the fractional one in the second step), we calculate robust standard errors for coefficients to account for undetected misspecifications.Footnote 9 In order to account for country-based heterogeneity, we also clustered standard errors by country.

Non-partisan appointments to European cabinets: empirical analyses

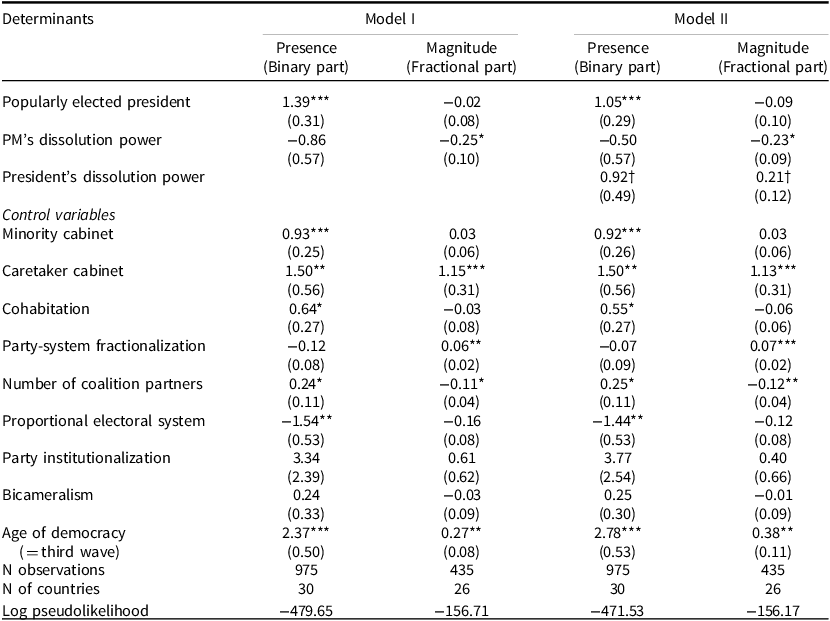

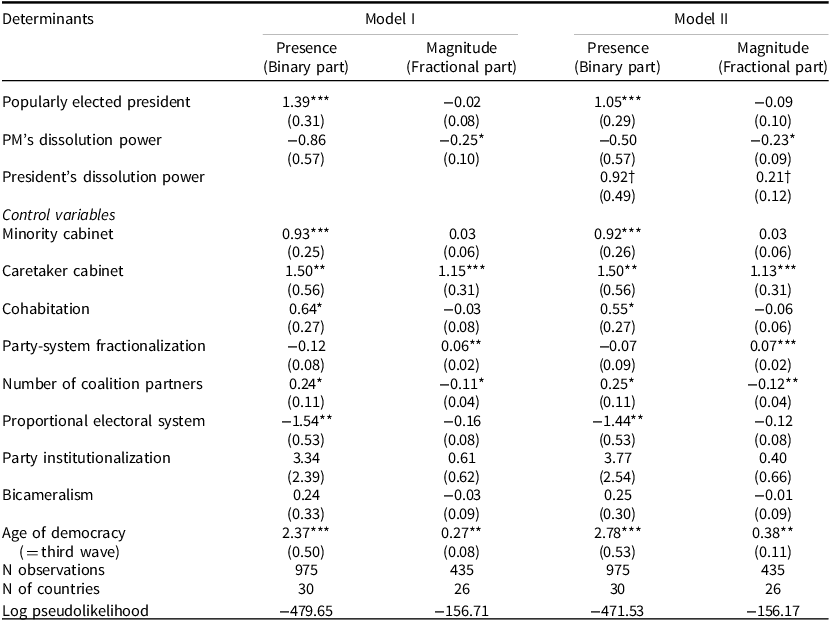

The results of our two-step fractional response regressions suggest that the presence of non-partisan ministers and the magnitude of their presence are indeed processes partially driven by different determinants (Table 3). As the econometric literature recommends (Hoetker Reference Hoetker2007; Papke and Wooldridge Reference Papke and Wooldridge1996; Villadsen and Wulff Reference Villadsen and Wulff2021; Wulff Reference Wulff2019), we do not interpret coefficients from the model directly but use average marginal effects, and we provide graphic representation of these effects.

Table 3. Coefficients from two-step fractional response regression models

Note: robust standard errors clustered by country in parentheses. *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05, † p < 0.1

Source: authors’ calculation.

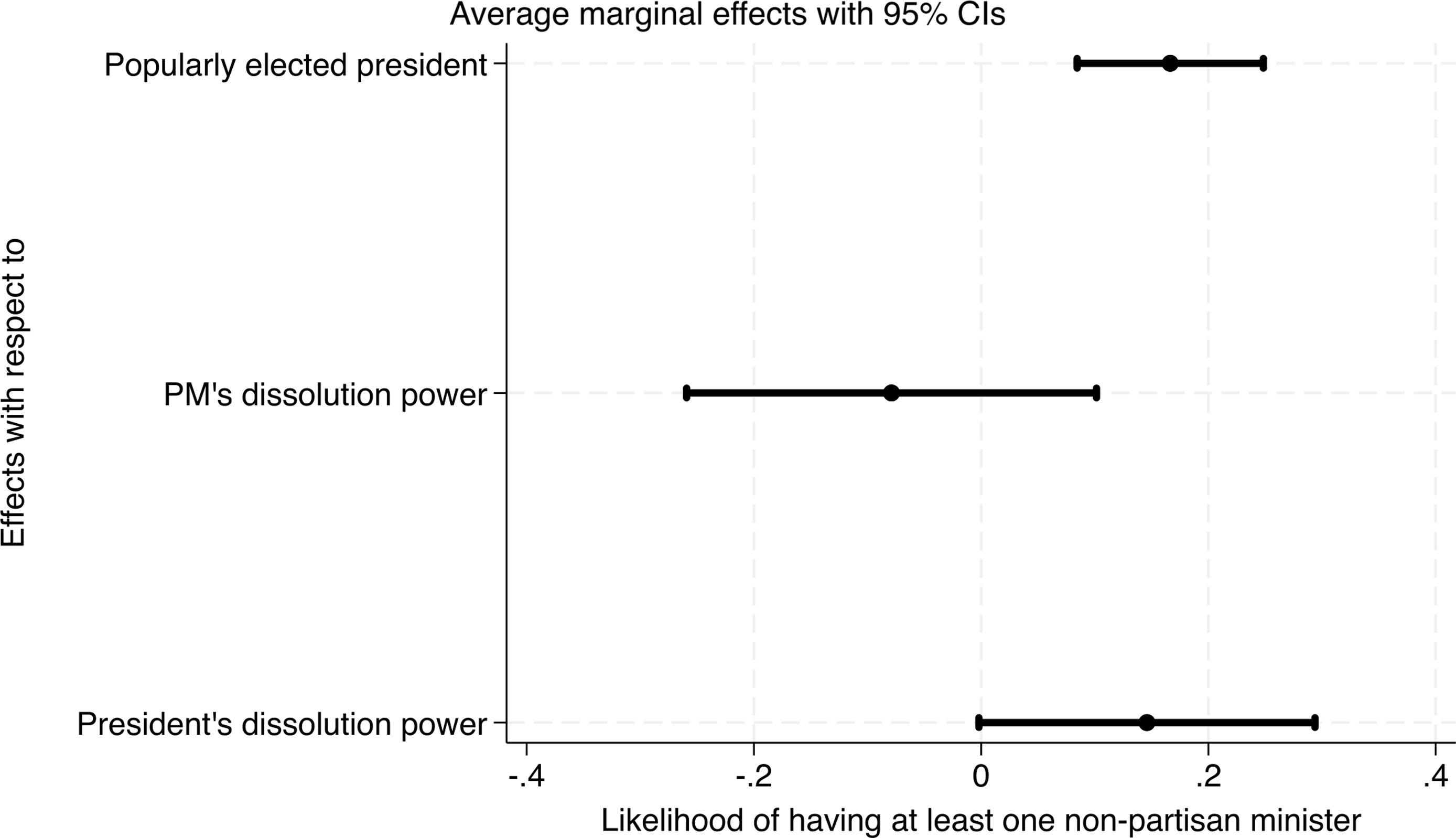

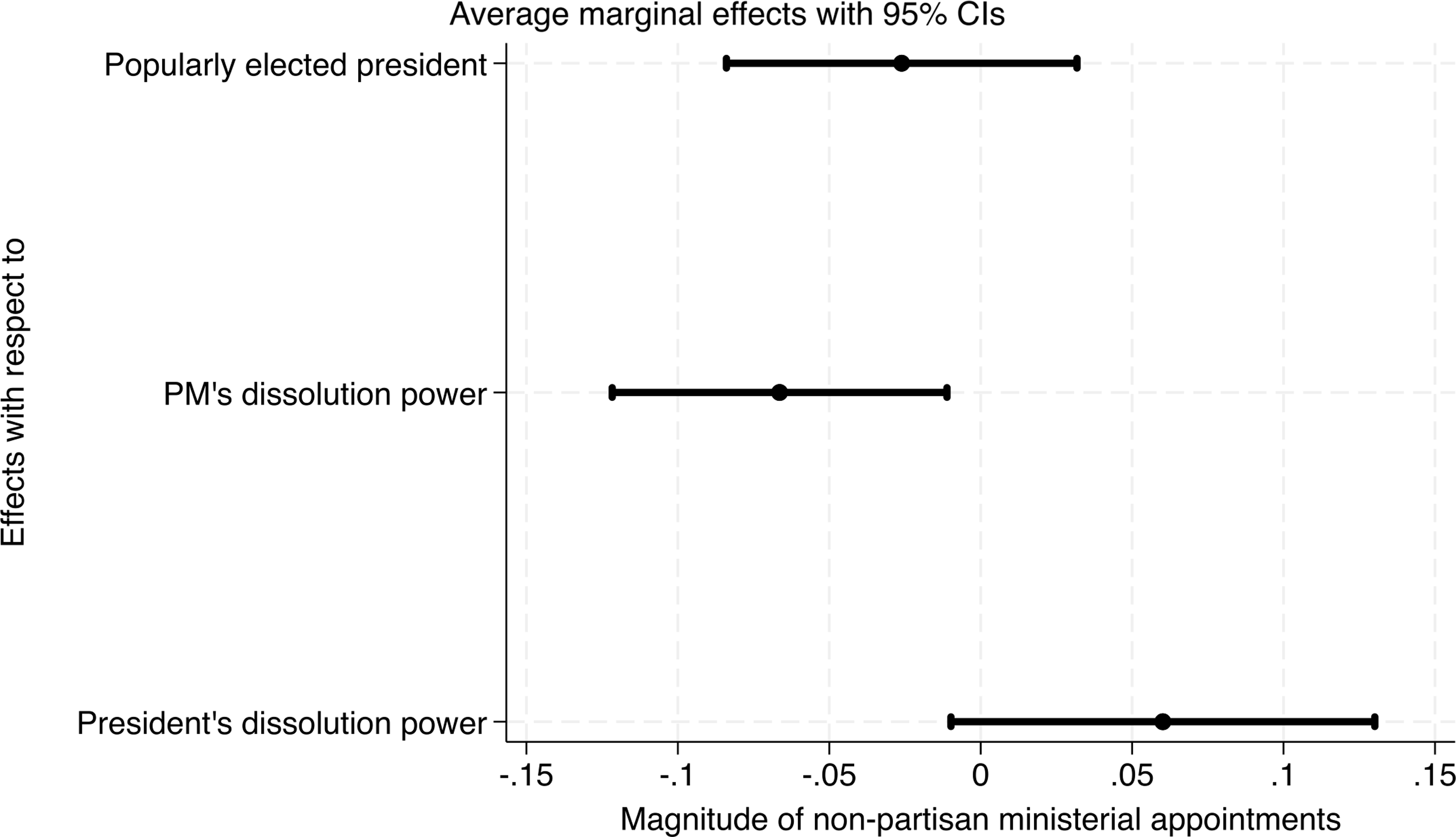

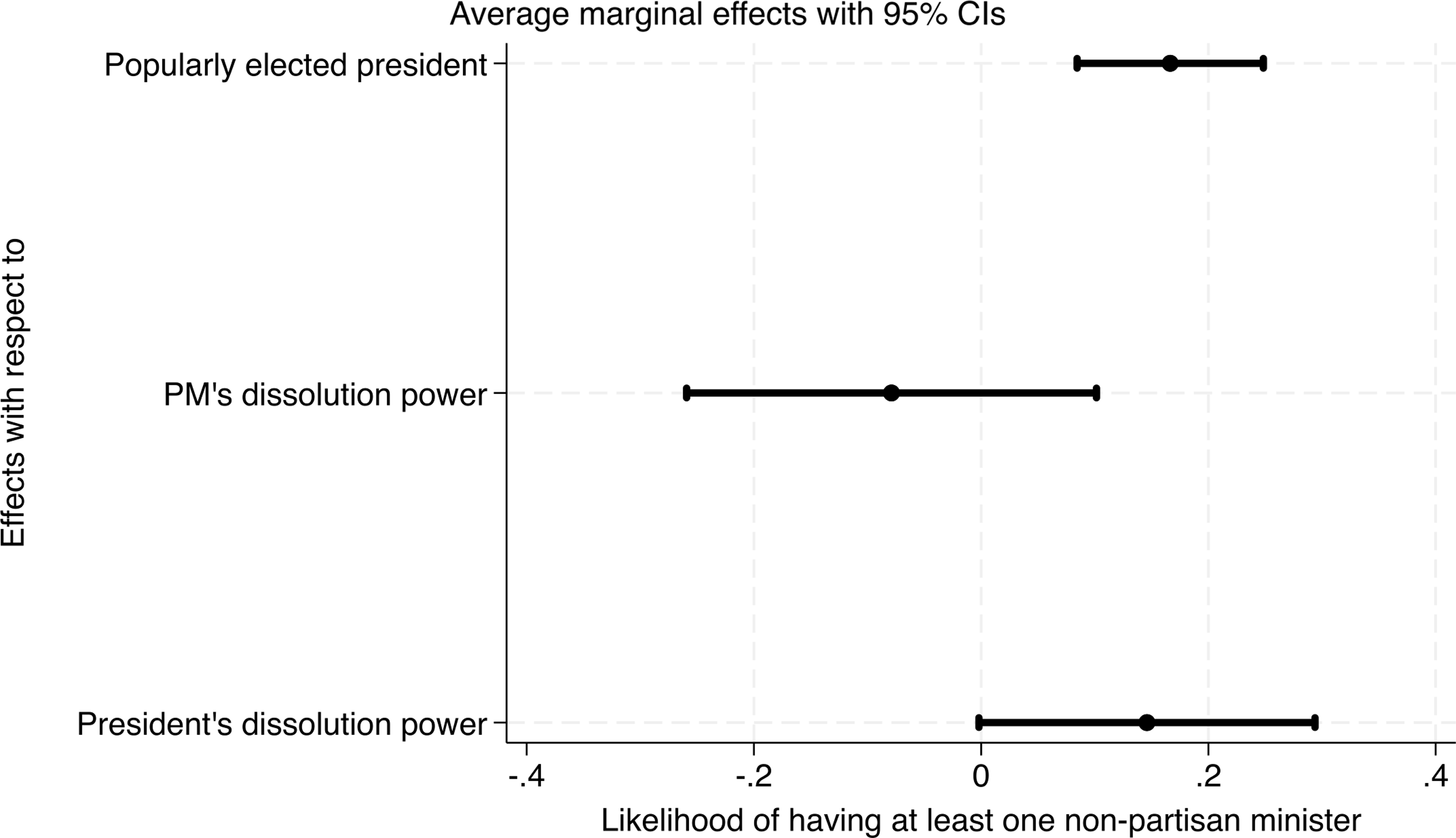

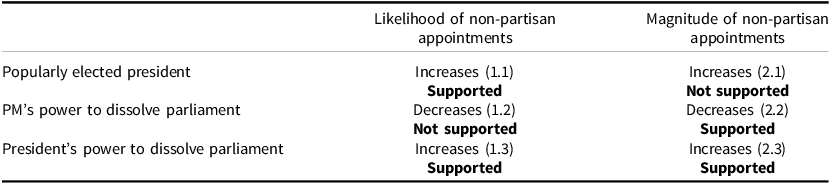

The only determinant significantly increasing the likelihood of non-partisan appointments is the popular election of the president, while the positive effect of the president’s parliamentary dissolution power is marginally significant (Table 3, Models I and II, Binary part). Specifically, the likelihood of non-partisan appointments increases by approximately 17 percentage points under popularly elected presidents and by approximately 15 percentage points in systems where presidents have discretional parliamentary dissolution power (Figure 1). In contrast, the PM’s power to dissolve the parliament has no significant effect on the presence of non-partisans in cabinet (and the direction of the effect is negative).

Figure 1. Average marginal effects of constitutional and institutional rules on the likelihood of non-partisan appointments (in percentage points, with 95% CIs).Notes: Based on Table 3 (Model II, Binary part). The average marginal effects are displayed as proportions on the standard interval [0; 1].

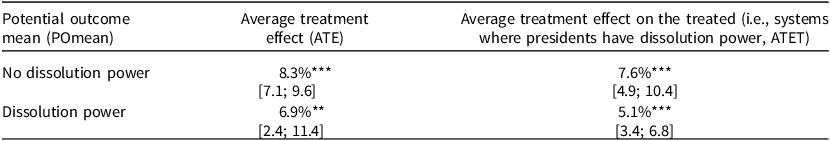

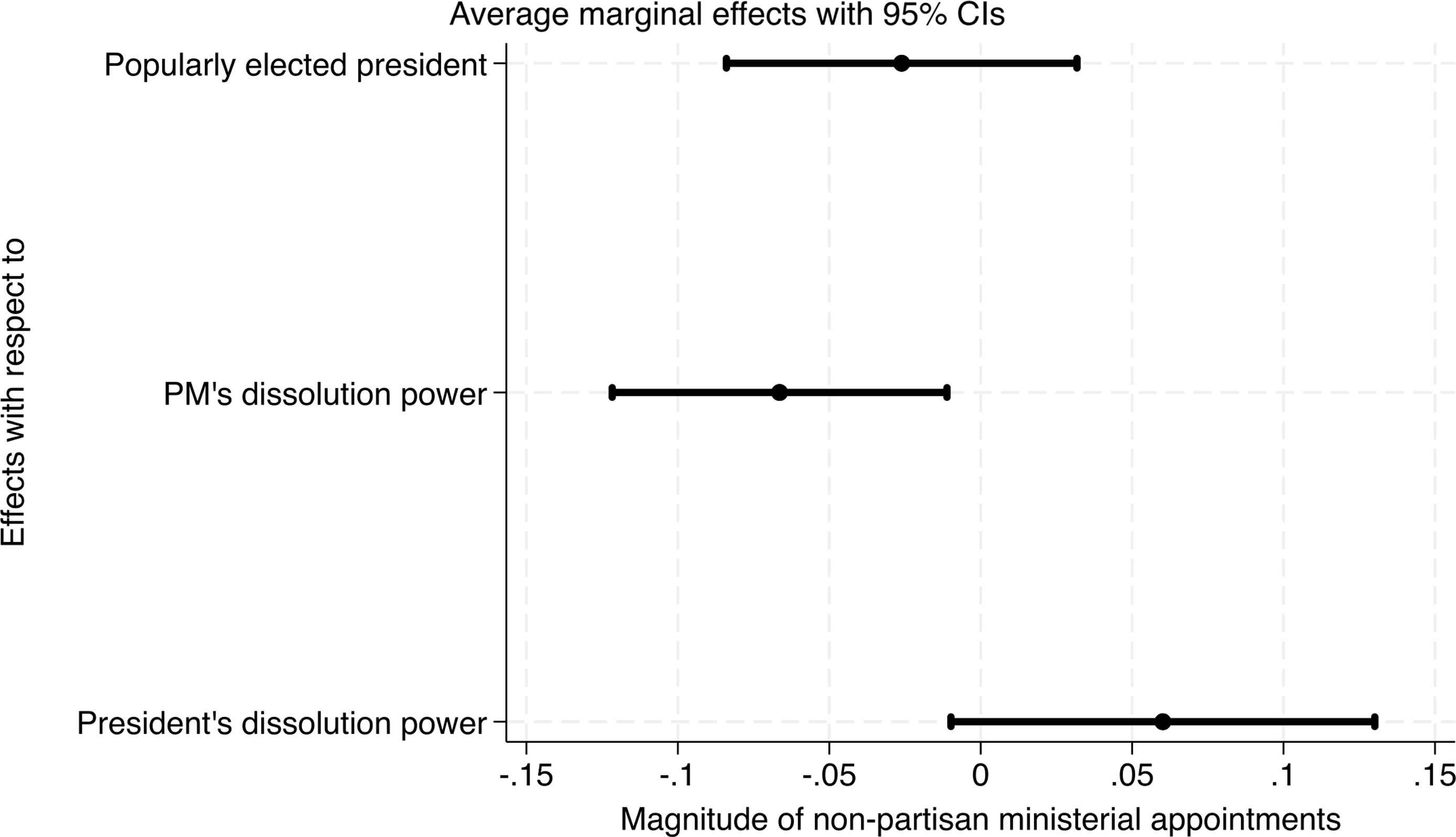

In the fractional part of the regression, two constitutional powers proved influential. The PM’s power to dissolve parliament decreases the mean proportion of non-partisan ministers by 7 percentage points (Figure 2), which is consistent with our hypothesis. Moreover, the president’s power to dissolve parliament tends to increase the mean proportion of non-partisan appointments by 6 percentage points. However, the mode of presidential elections does not appear to have any effect on the proportion of non-partisans in cabinets (Table 3, Model II, Fractional part).

Figure 2. Average marginal effects of constitutional rules on the magnitude of non-partisan appointments (in percentage points, with 95% CIs).Note: based on Table 3 (Model II, fractional part). The average marginal effects are displayed as proportions on the standard interval [0; 1].

For the control variables, the likelihood of non-partisan appointments increases by some 13 percentage points for a minority cabinet and by 24 percentage points if the cabinet has caretaker status (online Supplementary Materials, Figure A2). The age of the democracy (=third-wave democracies) has the largest increasing average effect on the likelihood of non-partisan appointments (approximately 44 percentage points). Proportional electoral systems decrease the likelihood of non-partisan appointments by some 23 percentage points, while bicameralism, party institutionalization, and cohabitation have no substantial effect at all. Finally, as expected, the effects of the party system and cabinet fractionalization on the likelihood of non-partisan appointments take different directions. While more party-system fractionalization has no effect on the likelihood that non-partisans will be appointed to European cabinets, cabinet fractionalization increases it (Supplementary Materials, Figure A3).

For the magnitude of non-partisan appointments, the mean proportion of non-partisan appointments increases by 33 percentage points for caretaker cabinets. The age of the democracy also has a positive effect on the mean proportion of non-partisans, increasing by 11 percentage points for new democracies (Supplementary Materials, Figure A4). The marginal effects of cabinet and party-system fractionalization show that the magnitude of non-partisan appointments substantially increases with growing parliamentary fractionalization and decreases with growing cabinet fractionalization (Supplementary Materials, Figure A5). Finally, all other control factors have no significant effect on the magnitude of non-partisan appointments.

Robustness

We examine robustness in various ways. The variable Decade, containing information about the decade when the cabinet was formed, has no significant effect on the likelihood of appointing any non-partisan ministers. However, there is a small positive effect on the magnitude of non-partisan appointments (p < 0.1) since the 2000s. The effects of our major explanatory variables and all control variables remain unchanged (Supplementary Materials, Figures A6-A7). We also found no effect of government ideology on the likelihood and magnitude of non-partisan appointments.

Some European constitutions grant parliamentary dissolution power to their indirectly elected presidents, so we estimated a model with an interaction between the mode of presidential elections and the president’s parliamentary dissolution power, finding no effect on the likelihood and a small negative effect on the magnitude of non-partisan appointments. However, the latter effect is driven entirely by Italy and disappears when Italy is excluded.

We also used three different operationalizations of presidential power in our models. The first operationalization uses Doyle and Elgie’s (Reference Doyle and Elgie2016) index of presidential powers instead of individual presidential powers, confirming our findings. The presidential power index has a significant positive effect on the likelihood of non-partisan appointments, but not on their magnitude (Supplementary Materials, Table A1, Models I and II).

Second, we tested the typology of semi-presidential systems (Samuels and Shugart Reference Samuels and Shugart2010; Shugart and Carey Reference Shugart and Carey1992) using president-parliamentarism (the PM and cabinet are collectively responsible to both the legislature and the president) and premier-presidentialism (the PM and cabinet are collectively responsible to the legislature only). Premier-presidentialism has a strong positive effect on the presence of non-partisan appointments, while president-parliamentarism has a nonsignificant effect on the likelihood of non-partisan ministerial appointments and a small negative effect on the magnitude of such appointments. The effect of the PM’s dissolution power remains the same (Supplementary Materials, Figures A8-A9). Both operationalizations support our results. However, we want to underline that while both presidential power indices (e.g., Elgie Reference Elgie2011) and system types (Kaiser Reference Kaiser1997) are helpful tools for comparative analysis, they hide crucial institutional determinants: most importantly, what, specifically, drives these effects – in our case, the president’s parliamentary dissolution power.

Third, we examined both presidential powers related to cabinet terminations: parliamentary dissolution and cabinet dismissal powers. Again, our findings are supported (Supplementary Materials, Figures A10-A11). The president’s dissolution power on both the likelihood and magnitude of non-partisan ministerial appointments is even stronger if we add the cabinet dismissal power in the model.

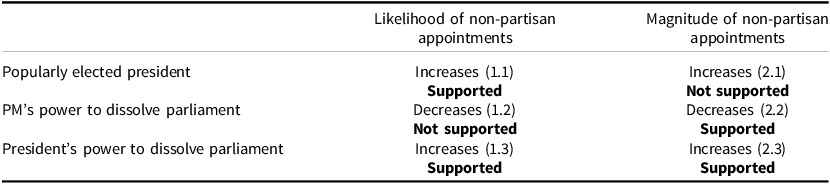

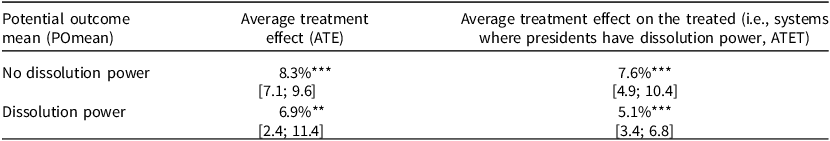

To assess the size of the presidential dissolution power effect, we conducted an additional causal analysis by estimating the regression-adjusted impact of the introduction of the presidential power to dissolve parliament on the proportion of non-partisan ministers (Table 4). The average effect of introducing such presidential power is related to the increase in the proportion of non-partisans by 6.9 percentage points: from 8.3% to approximately 15%. For systems with presidential dissolution power (i.e., treated systems) we examine the average treatment effect (average treatment effect on the treated, ATET). The introduction of the dissolution power is related to the average increase in the proportion of non-partisan ministers by 5.1 percentage points, to some 13%.

Table 4. The effects of presidential power to dissolve parliament on the proportion of non-partisan ministers (coefficients from the fractional logistic IPW adjusted regression)

Note: adjusted for the determinants: popular presidential elections, cohabitation, bicameralism, minority cabinet, caretaker cabinet, party system fractionalization, coalition fractionalization, age of democracy (=third-wave democracy), party system institutionalization, and proportional electoral system.

Robust standard errors are in parentheses; *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01.

Conclusion

We demonstrate that the detail of constitutional powers and institutional rules – particularly the specifics of prime ministerial and presidential power – are highly relevant for understanding ministerial appointments. The standard method of examining these issues by regime type misses important institutional features. The literature on non-partisan appointments generally argues that regime-type characteristics have a systematic impact on the appointment of non-partisan cabinet ministers. Divergencies in claims about those system-level effects concern the separate issues of appointing non-partisans and the number of such appointments. However, no previous study examines both the likelihood and the magnitude of non-partisan appointments together. Starting from the observation that many cabinets contain no non-partisans, we derive our claim that decisions on appointing non-partisan ministers and decisions on how many to appoint are two separate processes. Accordingly, we developed an empirical strategy to examine the two processes side by side. Thus, we introduce to political science a new empirical strategy – a two-step fractional response regression – making use of a novel dataset on non-partisan appointments in 30 European democracies from 1945 to 2024. Our core finding is that the presence of non-partisans in cabinets and the magnitude of their presence are indeed two distinct processes, partially driven by different factors.

In earlier, simpler models, researchers found a strong positive effect of semi-presidentialism on the proportion of non-partisan ministers in Europe (Neto and Strom Reference Neto and Strøm2006; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2010; Tavits Reference Tavits2009). We show that while direct election increases the likelihood of non-partisan appointments, it does not have an independent effect on their magnitude (Table 3, Model I). Being directly elected gives greater legitimacy to presidents to press or bargain for non-partisan appointments, but only when there is public support for such a move (Grimaldi Reference Grimaldi2023a). For presidents, there are many benefits in appointing non-partisan ministers, and presidents tend not to bear the electoral costs if such ministers fail, as would be the case for PMs (Semenova and Dowding Reference Semenova and Dowding2021). When it comes to the magnitude of such appointments, other more specific features of the constitutional powers, notably having substantial non-legislative powers, enable presidents to appoint higher numbers of non-partisan ministers. There are no interaction effects between these two factors.

Unlike the mode of presidential elections, the presidential power to dissolve parliament increases both the likelihood of non-partisan appointments and their magnitude (Figures 1 and 2). While presidents use this power less often than PMs (Neto and Costa Lobo Reference Neto and Costa Lobo2009; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2009b), the president’s dissolution power has electoral consequences, boosting the vote for the PM’s party associated with the president by around 5 percentage points (Schleiter and Morgan-Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2018). The presidential threat of parliamentary dissolution tends to render both coalition and opposition leaders more receptive to presidential preferences in ministerial appointments. Additional causal analysis (Table 4, ATET) shows that the introduction of the presidential power to dissolve parliament leads to an increase in the number of non-partisan appointments by approximately 7 percentage points to some 15% – or three non-partisan ministers out of an average cabinet of 20 ministers.

The PM’s power to dissolve parliament does not affect the likelihood of non-partisan appointments but strongly decreases their magnitude. The first finding supports previous studies about the high level of party control in systems where the PMs can dissolve the parliament (Strøm and Swindle Reference Strøm and Swindle2002). In such systems, the selection of ministers occurs through and within parties. Another feature of such systems is individual ministerial responsibility for failures, which tends to shift the blame from the PM and her party to an individual minister (Dewan and Dowding Reference Dewan and Dowding2005). Under these circumstances, appointing a non-partisan minister breaks with party-government tradition, while the failure of such a minister immediately pins the blame on the PM, who chose a non-partisan over party-experienced candidates. Hence, if there are any non-partisan ministers in systems where the PM has great discretionary powers, their magnitude is minuscule (see also Table 2). The exception to this rule is Spain, where several PMs have appointed large numbers of non-partisan ministers since the late 1970s.Footnote 10

Minority cabinets, cohabitation, and proportional electoral systems explain the likelihood of non-partisan appointments, but not their magnitude. Minority cabinets and cohabitation are associated with a higher probability of non-partisan ministers, supporting previous assumptions in the literature (Neto and Strøm Reference Neto and Strøm2006; Schleiter and Morgan-Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2010). We find that proportional electoral systems are associated with a lower probability of non-partisan ministers; minority cabinets, cohabitation, and proportional electoral systems have no effect on the proportion of non-partisans in cabinets; and bicameralism has no effect on either the appointment or magnitude of non-partisans.

There are just two determinants – age of the democracy and caretaker cabinet status – that increase both the likelihood and the magnitude of non-partisan appointments at the same time. These results confirm the idea that non-partisan ministers are used as placeholders in cabinets formed after or amid crisis situations (Lee Reference Lee2018; Neto and Strom Reference Neto and Strøm2006). Compared to established democracies (such as the UK) and second-wave democracies (such as France), third-wave democracies (such as Poland and Spain) have a higher propensity to appoint non-partisans in larger quantities. These findings align with previous studies on non-partisans in European third-wave democracies (Costa Pinto and Tavares de Almeida Reference Costa Pinto, Tavares de Almeida, Costa Pinto, Cotta and Tavares de Almeida2018; Semenova Reference Semenova, Costa Pinto, Cotta and Tavares de Almeida2018, Reference Semenova2020).

Finally, as expected, party-system fractionalization and cabinet fractionalization show opposing effects on the likelihood and magnitude of non-partisan appointments. With fractionalization of parliaments, the likelihood of non-partisan appointments slightly decreases, but their magnitude increases, in line with previous studies (Schleiter and Morgan-Jones Reference Schleiter and Morgan-Jones2010). Fractionalization of coalitions is associated with a higher probability of non-partisan appointments, but a lower number of non-partisans with every additional coalition partner (see Neto and Strøm Reference Neto and Strøm2006). This finding is also plausible, as the higher the number of coalition partners needed to establish a viable coalition, the less likely they are to relinquish control over policy areas assigned to them via negotiations by delegating these policy areas to non-partisan ministers.

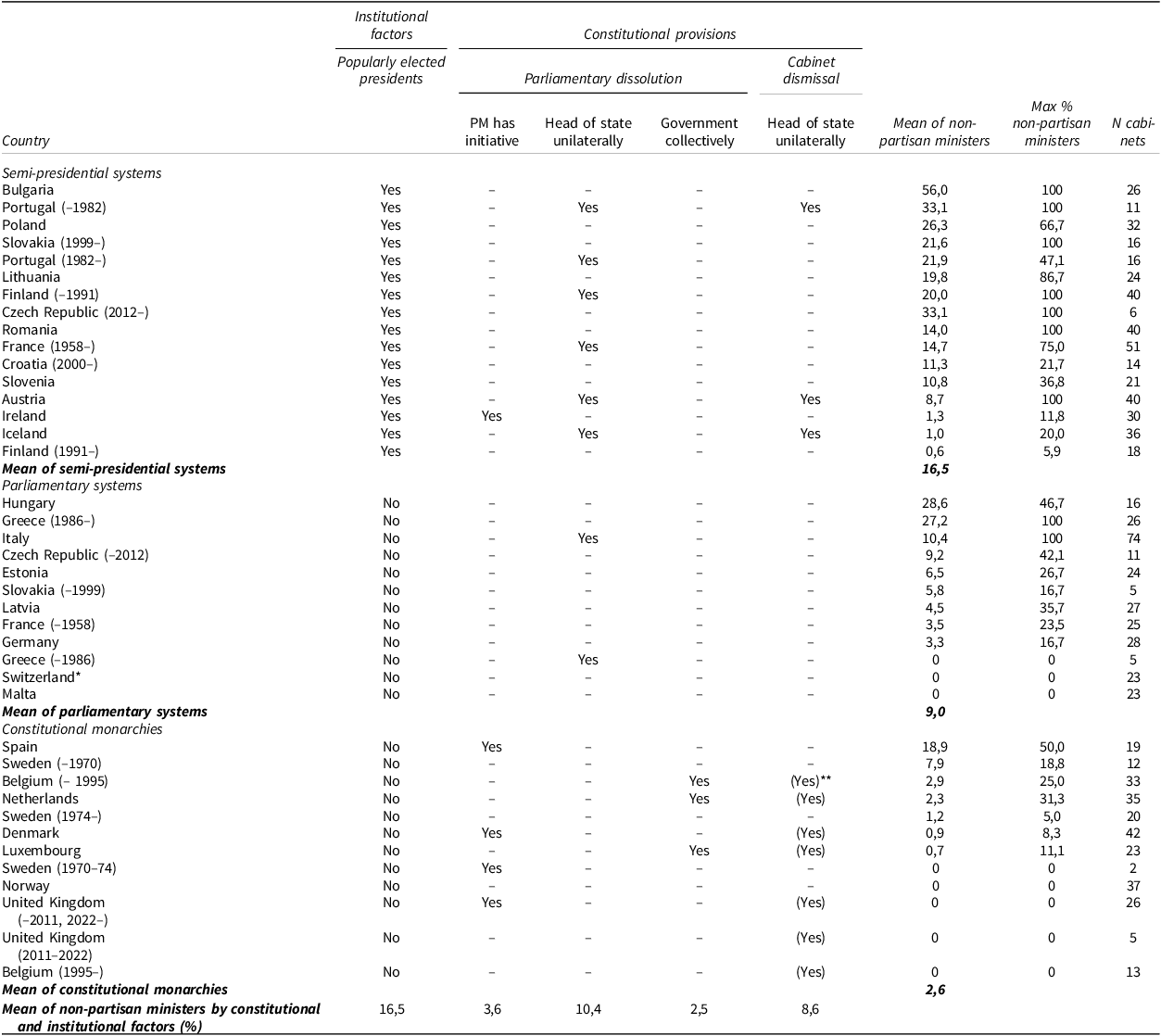

Table 5 summarizes our findings in relation to our original hypotheses.

Table 5. Summary of hypotheses

Our analysis points out that country-specific history trajectories are also important, as the Greek anomaly in relation to the presidential power of parliamentary dissolution and non-partisan legacies in third-wave democracies suggests. Country-specific informal understandings are harder to capture in large-N studies and require detailed case studies. While we have developed hypotheses based on previous literature and the logic of prime ministerial and presidential powers and their primary motivations, we have also demonstrated that examining the descriptive empirics and then choosing an appropriate statistical approach to tease out relationships is important to understanding potential causal mechanisms.

Our findings here suggest further research directions, such as examining the effects of non-partisan ministerial appointments on democracy development, on policy outputs, and on public attitudes towards party government. For example, public perceptions of non-partisan appointments differ depending on their likelihood and magnitude in any given country (Semenova, Dowding, Kaiser et al. Reference Semenova, Dowding, Kaiser and Di Biagio2025). The career backgrounds and the personal characteristics of non-partisan ministers in relation to partisan ministers, the probability of resignation in relation to partisan ministers, and what post-ministerial careers they have are all future directions for research. All these research directions require a more fine-grained analysis of appointments than we present here. They also depend on our major argument that precise institutional powers and understanding can have large effects, and thus our explanations often need to go beyond regime types.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1475676525100492.

Data availability statement

Replication data can be found in the Supporting Information.

Financial support

The project is supported by the German Scientific Foundation, grant Nr: 469033183.

Competing interests

The authors have declared none.