Introduction

Quaternary sciences depend on diverse sources to reconstruct historic conditions. Most often these provide indirect evidence (proxies) that bears only partially on the knowledge sought, and each source has limitations that must be considered in interpretation. To obtain the most accurate understanding, multiple types of data are used together. Introducing new forms of evidence often significantly changes the interpretation of past events.

Indigenous oral histories, stories passed aloud from generation to generation, provide rich sources of information on historic events that can complement and augment Western science proxies (Echo-Hawk, Reference Echo-Hawk2000; Mackenthun and Mucher Reference Mackenthun and Mucher2021; Angelbeck et al. Reference Angelbeck, Springer, Jones, Williams-Jones and Wilson2024). Once regarded by Western transcribers as purely mythical and imaginary stories (Lowie, Reference Lowie1915; Dorson, Reference Dorson1963; Mason, Reference Mason2000), oral-history narratives are now understood to contain elements of past eyewitness accounts that can serve as a valuable new source of paleoenvironmental information (Whiteley, Reference Whiteley2002; Hittman, Reference Hittman2013; Stoffle et al., Reference Stoffle, Van Vlack, Lim, Bell and Yarrington2024).

Indigenous oral-history narratives abound in cultures around the world (Hulan and Eigenbrod, Reference Hulan and Eigenbrod2008). In western North America, they have been used successfully in combination with geologic analysis of past catastrophic events, such as volcanic eruptions (Moodie et al., Reference Moodie, Catchpole and Abel1992; Budhwa et al., Reference Budhwa, Mackenthun, Mucher, Mackenthun and Mucher2021; Angelbeck et al., Reference Angelbeck, Springer, Jones, Williams-Jones and Wilson2024), megathrust earthquakes and tsunamis (Hutchinson and McMillan, Reference Hutchinson and McMillan1997), and massive landslides and floods (McMillan and Hutchinson, Reference McMillan and Hutchinson2002; Budhwa et al., Reference Budhwa, Mackenthun, Mucher, Mackenthun and Mucher2021). Many Indigenous oral-history narratives involve plants and animals and describe their dietary and cultural values (Sutton, Reference Sutton1989; Berkes et al., Reference Berkes, Colding and Folke2000). Paleoecological dynamics within the narratives, however, such as plant migration and biogeography, are under-investigated.

Oral tradition has long been recorded in the Great Basin, USA (Lowie, Reference Lowie1909; Kelly, Reference Kelly1938; Fowler and Fowler, Reference Fowler and Fowler1971). Although most analysts have compared content from the narratives with Western science to validate the former, we move beyond this to examine Indigenous sources for new information useful to Western science. We use Indigenous content to expand and test Western science hypotheses. Our overall goal is to document the power of oral-history narratives in paleoecological analysis through a case study of one Great Basin (GB) narrative, the Theft of Pine Nuts (TPN). TPN is a common story in the opus of GB oral-history narratives, with many variants and well-represented throughout the region. At its core, TPN is an epic-origins story, describing how pine nuts—an essential element of GB diets—were brought to the People. Our specific objectives are to (1) compile variants of the TPN story; (2) evaluate the antiquity of TPN; (3) analyze the stories for their ecological and physical content; and (4) use that content to test and expand Western science hypotheses of late Pleistocene–Holocene pinyon pine (Pinus monophylla) biogeography and migration.

Oral-history narratives and Indigenous science

Indigenous histories are steeped in social values and interwoven with cultural identity. As such, they comprise a very different category of knowledge than those conventionally used in Quaternary sciences. Drawing upon these stories responsibly requires an explicit respect for the culture from which they come and understanding of Indigenous storytelling traditions (Echo-Hawk, Reference Echo-Hawk2000; Whiteley, Reference Whiteley2002). Indigenous GB scholars have long argued that tribal input is essential for developing insights into deep history of the GB (Crum, Reference Crum1994; Brewster, Reference Brewster2003; Blackhawk, Reference Blackhawk2006; Teeman, Reference Teeman2024). The embedded cultural context of these narratives must be appreciated for the symbolism, latent content, and allegory they contain. The Indigenous partners in this study shared insights into these histories that interpret the traditional lifeways and natural environments reviewed here. In a companion paper, the same authors develop in more detail the nature, history, and survival of GB oral history (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Millar, Benner, Fillmore, Cossette, Teeman and Wewain press); here we focus specifically on ecological and physical insights in these oral histories.

GB Indigenous narratives, by definition, were spoken by Elder storytellers and carry much of the content of Indigenous science. Most of those transcribed over the last 150 years were translated into English, where regrettably much of the original meaning was potentially lost. The stories describe events of fundamental significance (e.g., creation) or represent epic-adventure stories that transmit cultural norms and codify moralities (Liljeblad, Reference Liljeblad1986). The narratives are not expressed as hypotheses subject to testing or validation; they describe events accepted as real and correct history, “what actually happened” (Hittman, Reference Hittman2013). To survive over generations, the narratives were structured to be entertaining (thus, remembered) as well as instructive, and often contain colorful, playful, or exaggerated elements.

Space (place) and time play out in the oral-history narratives in different ways. Many stories contain recognizable elements of local landscape, such as mountain peaks and plant and animal species. The (English) transcriptions sometimes use modern place-names and common names of known animals or birds. Such descriptions are often sufficient to locate stories and their variants in the current landscape.

Unlike geography, time (including dates, ages, and chronological order) is more difficult to interpret—nor was it important from the narrator’s perspective—in the oral-history narratives (Liljeblad, Reference Liljeblad1986). Events are commonly described as occurring “in time immemorial” or “a long time ago.” Time is understood to be nonlinear, and each cycle rests upon collapsing onto the previous. Narratives that we assessed represent a period of time “when Animals were People,” considered to be in deep time.

Recognizing vast differences in goals, methods, and intent between Indigenous science and Western science, we provisionally assume that Indigenous oral-history narratives could contain elements that reflect eyewitness observations as well as fictional imagery (Echo-Hawk, Reference Echo-Hawk2000; Whiteley, Reference Whiteley2002). As with other indirect sources of information in Quaternary sciences, we acknowledge that advantages, disadvantages, and biases likely exist, and temper our interpretations accordingly.

Current understanding of historic pinyon biogeography

Singleleaf pinyon pine and its relatives in genus Pinus subsection Cembroides have evolutionary origins in what is now southwestern North America dating to the early Paleogene (>60 Ma; Axelrod, Reference Axelrod1986; Millar, Reference Millar1993). The northern pinyons in subsection Cembroides, including singleleaf pinyon, diversified in tandem with the emerging geologic landscape of the GB (Axelrod, Reference Axelrod1958).

Few records of pinyon pine have been dated to the Early or middle Pleistocene in the GB, likely due to limitations of the record rather than absence of the species (Betancourt, Reference Betancourt and Everett1986). A pollen core from Owens Lake that extends more than 800,000 years documents abundant Pinus pollen (Litwin et al., Reference Litwin, Adam, Frederiksen, Woolfenden, Smith and Bischoff1997). Pinyon-type pollen, interpreted as P. monophylla, was analyzed from the last 180,000 years of the core (Woolfenden, Reference Woolfenden2003) and occurred in high-enough abundances to indicate local populations of pinyons. Pinyon pollen percentages showed significant fluctuations that correlated with major cycles of cold (glacial) and warm (interglacial) periods during the last 180,000 years.

We focus on the late Pleistocene (LP; ∼22–11.7 ka) and the Holocene (<11.7 ka). Evidence of pinyon’s occurrence in the GB during that time comes primarily from macrofossils in ancient packrat (Neotoma spp.) middens (Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, Van Devender and Martin1990). Early work on pinyon distribution led to a widely accepted hypothesis that pinyon was absent from most of the GB during the LP and Early Holocene, as climates were too cold for it to survive (Lanner, Reference Lanner and Thomas1983; Wigand and Nowak, Reference Wigand, Nowak, Hall, Doyle-Jones and Widawski1992; Lanner and Van Devender, Reference Lanner, Van Devender and Richardson1998; Grayson, Reference Grayson2011; Cole et al., Reference Cole, Fisher, Ironside, Mead and Koehler2013). Instead, pinyon and its closest relatives retreated southward to areas currently dominated by Mojave Desert ecosystems, where they found conditions favorable for growth (Spaulding, Reference Spaulding, Betancourt, Van Devender and Martin1990). With warming temperatures of the Holocene, pinyon began to migrate north, mostly after 7–8 ka, into the GB, reaching its modern northern boundary only in the past several hundred years (Lanner and Van Devender, Reference Lanner, Van Devender and Richardson1998; Figs. 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Current known distribution of singleleaf pinyon pine (Pinus monophylla) (dark-brown shading) in the southwestern United States. Gray shading is the hydrologic Great Basin. Source: DataBasin (2024).

Figure 2. Pinyon hypothesis 1: Migration of pinyon pine from a southern Pleistocene refugium, estimated from midden locations and radiocarbon dates (reprinted from Millar and Thomas, Reference Millar, Thomas and Thomas2024a). The brown polygon denotes the southern late Pleistocene refugium, red arrows show movement out of that refugium during the Early Holocene, and blue arrows show subsequent movement. Gray shading is the hydrologic Great Basin. Numbers represent midden sites used by Millar and Thomas (Reference Millar, Thomas and Thomas2024a) to show pinyon migration.

Using revised radiocarbon dates and adding new sites, Thomas and Millar (Reference Thomas and Millar2024; also Millar and Thomas Reference Millar, Thomas and Thomas2024a) updated this traditional interpretation, and proposed an alternative scenario (Fig. 3). This retained the LP, southern Mojave refugium, and in addition proposed several high-latitude pinyon refugia. These were suggested as areas where pinyon had advanced during an earlier warm interval, and where, during the last ice age, pinyon survived in very restricted and scattered populations. High-latitude refugia were proposed for the northern White Mountains, CA; Warner Mountain region, CA/NV/OR; the Bonneville region, NV/UT; and the Bear Lake region, UT/ID (Fig. 3). Various lines of evidence were brought forward for these refugia, and tests were employed to compare the hypotheses (Millar and Thomas, Reference Millar, Thomas and Thomas2024a). In the end, both had strengths and weaknesses and were retained for further testing.

Figure 3. Pinyon hypothesis 2: Northward migration of pinyon pine from the southern Pleistocene refugium and outward from four Pleistocene refugia at higher latitudes in the western and eastern Great Basin (GB), estimated from pollen and midden locations and radiocarbon dates and, for the northeast California refugium, from ethnographic evidence and herbarium records (reprinted from Millar and Thomas, Reference Millar, Thomas and Thomas2024a). Brown polygons denote five late Pleistocene refugia, red arrows show movement out of the refugia during the Early Holocene, and blue arrows show subsequent movement. Gray shading is the hydrologic GB. Numbers represent midden sites used by Millar and Thomas (Reference Millar, Thomas and Thomas2024a) to show pinyon migration.

Great Basin mammal species

The GB has long been a region of interest for biogeographic study of plants and animals, especially for the “island” nature of its hundreds of mountain ranges separated by broad, low basins (Brown, Reference Brown1971; Lawlor, Reference Lawlor1998; Grayson and Livingston, Reference Grayson and Livingston1993). Alternating climates of the LP and Holocene triggered dramatic shifts in plant and animal ranges (including pinyon pine), leading to contractions and expansions as well as extinctions and local extirpations (Grayson, Reference Grayson2011). Reconstructing the pre-contact occurrences of GB mammalian species has been challenging, given the complex topography, difficult conditions for survey and preservation, and the limited explorations undertaken (Grayson and Livingston, Reference Grayson and Livingston1993).

Layered on these uncertainties are effects resulting from human activities in the last 15,000 years. Impacts from naturally changing climates, especially on large herbivores, were compounded by stresses of Indigenous hunting (Burney and Flannery, Reference Burney and Flannery2005; Hockett, Reference Hockett2015). Putting aside the megafaunal climate versus overkill discussion (Meltzer, Reference Meltzer2020), the ranges of some large mammals, at least, appear to have been affected by Indigenous activities, especially as climates were changing (e.g., Garfinkel et al., Reference Garfinkel, Young and Yohe2010). The largest anthropogenic effect, however, occurred during the settlement period as a result of over-trapping and overhunting by European-origin pioneers, especially on fur-bearing meso-carnivores and large herbivores (Tappe, Reference Tappe1942; Buechner, Reference Buechner1960; Yoakum, Reference Yoakum, O’Gara and Yoakum2004; Shelton and Weckerly, Reference Shelton and Weckerly2007). During that time many species were extirpated from the GB, or their numbers vastly diminished. Attempts to reconstruct prior ranges of these species have been based on historic narratives of explorers and settlers as well as scant fossil evidence, but these have limited scope and uncertain accuracy.

Methods

TPN versions

We searched the published and gray literature (especially ethnographies and historic documents) for transcribed oral-history narratives relating to pine-nut origins. Search titles were Theft of Pine Nuts, Theft of Fire, and other phrases involving pine-nut origins. Indigenous participants in this study contributed additional versions and interpreted the role of oral-history narratives in GB culture generally and pine-origin narratives specifically.

Evaluating the antiquity of the TPN narrative

The occurrence and prominence of a massive ice barrier (occurring in other GB oral-history narratives also) is described in such detail that it can be analyzed relative to the historic conditions of ice known for the GB. We assessed glacial periods from the LP through to the present and compared known conditions to descriptions in the oral-history narratives.

Physical and ecological information in the TPN narratives

We evaluated the TPN narratives for their natural-history content and compiled lists of mammal, bird, fish, and lizard species. We initially assumed the English names for species in the narratives were correctly translated and referred to known taxa. Indigenous coauthors evaluated these assignments, and we also consulted translation dictionaries. In some cases, we used clues from the description and location of species that were named generically to propose likely taxa. Locations were noted for mammal species as provisional descriptions of historic occurrences.

Pine-nut homelands in the TPN narratives

For each of the variants, we attempted to determine the location of the pine-nut homelands. In most versions, this was where the Animal People lived who hoarded the pine nuts. Place-names, topographic features, and indicator bird and animal species were most useful. For the latter, several species have limited distribution in the GB, and provided helpful georeference, recognizing that historic distributions may have differed. We paid special attention to details describing pine-nut homeland locations that are outside the current pinyon distribution range.

Identifying the pine-nut species in the oral-history narratives was critical, in that we sought to understand pinyon pine’s biogeography. This was especially important when pine-nut homelands were outside the current pinyon range and within the range of other pine species. We evaluated ethnographic and archaeological references on pine-nut usage. Indigenous coauthors provided information on historic tribal use of pine-nut species.

Results

TPN compiled narratives

We compiled 61 versions of TPN and related pine-nut origin narratives (Table 1, Supplementary Material, Supplement 1). In content, they ranged from long, far-reaching epics to a few lines outlining the central plot. Only two versions were written in native languages (with English translations), whereas the rest were transcribed directly into English. The oldest version was recorded by John Wesley Powell in 1873 (Fowler and Fowler, Reference Fowler and Fowler1971); the most recent include a 2014 Wá∙šiw (this spelling is preferred over “Washoe” by tribal members) children’s story and TPN versions presented here by coauthors Misty Benner and Diane Teeman. Written versions of the narrative, thus, have been known for 152 years. The TPN narrative continues to be told; all native coauthors heard the story in their youth.

Table 1. Compiled list of 61 versions of Theft of Pine Nut oral-history narrative analyzed in this study.

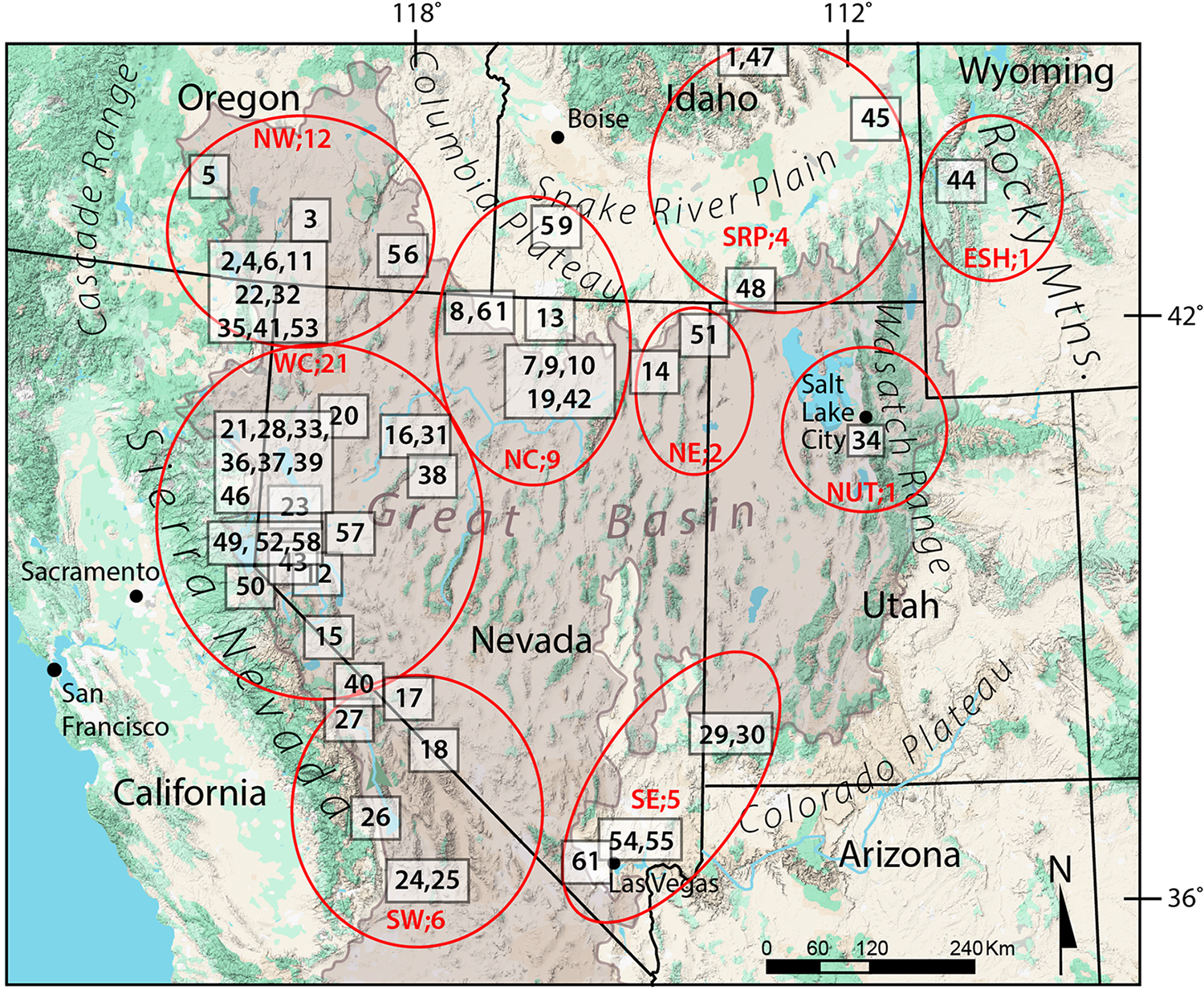

The 61 versions derived from eight of the nine tribal territories mapped by d’Azevedo, (Reference d’Azevedo1986; Fig. 4). We found no versions from Owens Valley Paiute. Northern Paiute territories were most represented and Ute the least.

Figure 4. Tribal territories in the Great Basin and border regions. Modified from d’Azevedo (Reference d’Azevedo1986; permission from National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution).

Stripped to their core, TPN narratives relate how pine nuts initially were absent from the narrator’s (usually Coyote) land. The narrator and his Animal companions smell pine nuts cooking far off, travel to the distant pine-nut land where they steal the nut, and bring it home. The story is illustrated by a Northern Paiute version (Fowler et al., Reference Fowler, Fowler and Powers1970, p. 135):

The Old Wolf and the Coyote made a great fandango or dance, and the coyote was a singer. They wanted something good for their guests to eat. The coyote went away up north, many days journey, and smelled four ways, and found pine-nuts. The Old Crane was ruler of that land in the north. He made some pine-nut mush, and filled the coyote’s mouth with it, and plastered it all over him. Then the coyote went back to his own land in the south, and the wolf smelled him and said it was good. They all started to go north to the pine-nut country. But the Old Crane hid all the pine-nuts. The little mouse found them, and the yellow woodpecker pulled them out with his bill. All the Crane’s sons were asleep, and they slept so soundly that they could not be awakened, though an old woman threw water on them. So they got the nuts, and the wolf’s sons ate them all up. Then they all started to go south. But there was a great wall of ice in the way, which they could not pass. All of them tried to break it, but they could not. But at last the little Crow broke it. The coyote tried to pass through where the little crow broke it, but he could not. The Old Crane came upon them and killed all of them except the crow and the chicken-hawk. The chicken-hawk had a stinking leg, and the crane could not catch him. So he escaped and he flew to the top of a great hill (Dayton Hill, near Virginia City), and there he vomited up all the pine-nuts he had eaten in the crane’s country. These sprang up and grew and thus pine-nuts were brought to the Paiute land.

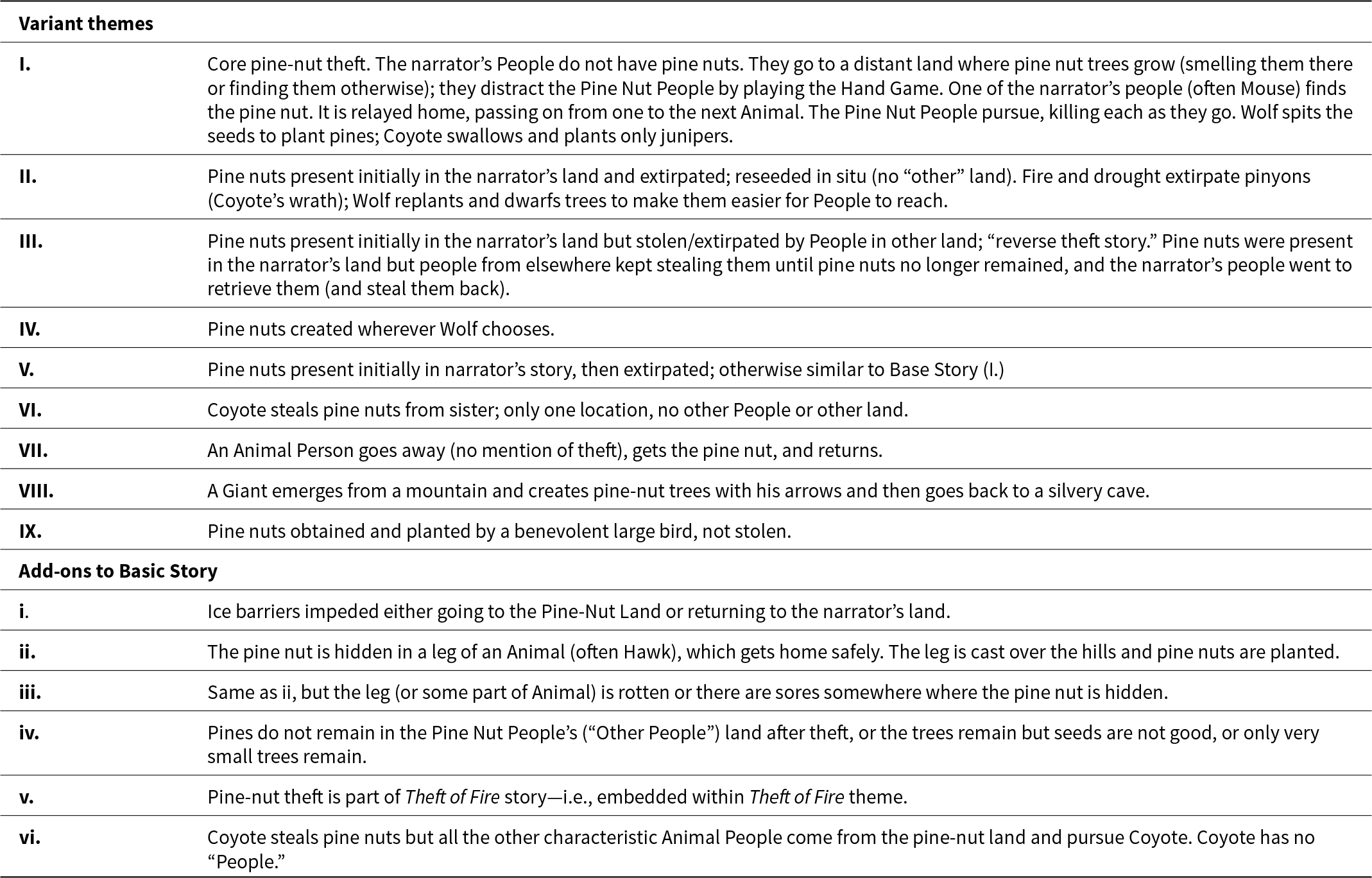

Although the versions are highly consistent, the central plot is modified and embellished in several ways among the narratives. We recognize nine themes as well as additions and deletions (Table 2, Supplementary Material, Supplemental Table 1). In a few versions, the pine-nut theft story is embedded within the widespread Theft of Fire story, which has a narrative similar to TPN but focuses on fire. In other versions the storyline is quite different but nonetheless describes how pine nuts were first brought to the People.

Table 2. Variant themes and add-ons of the Theft of Pine Nuts and related pinyon origin stories (refer to Supplementary Material, Supplement Table 1).

Antiquity of the elements in the TPN narratives: role of the ice barrier

Perhaps the most astonishing element in the TPN tales is the occurrence of an ice barrier: 22 of the 61 variants include this (5 from the NW; 15 from the WC; 1 from the NC; and 1 from the NUT; for codes, see Fig. 5, Supplementary Material, Supplemental Table 1). The ice barrier is portrayed as a towering wall of ice that impedes the Animal people from proceeding toward the pine-nut land and/or in returning home after stealing the pine nuts. The ice barrier is described as formidable (“They travelled until they came to an ice blockade. It stood from sky to earth.” no. 4 (here and throughout “no.” refers to version number in Table 1); in another version, “You’ll never believe what I [Grizzly Bear] found. I went up there to the north and there was a big mountain of ice. Because it was so huge I could not go around the mountain … In awe, they [Coyote’s People] looked up into the sky, and the ice mountain went up into the clouds.” no. 40); and seemingly uncrossable (“They found a blockade of ice just like these mountains; it was all ice … They all stopped there; they couldn’t go across.” no. 2). The Animal People eventually cross the ice barrier, usually with the help of corvid birds that fractured the ice. Importantly, the narratives make clear that this was an ice wall, not winter snow (“All the animals packed up and went to see the mountain of ice. When they were approaching from a distance they could see white, and somebody said, ‘It’s snowing! That’s all it is, it’s just snowing.’ And the Grizzly Bear told them, ‘We still have many more days to go.’ So they went on for many days, until they finally got to the wall of ice. And they looked up and it was true!” no. 40).

Figure 5. Geographic subregions of the Great Basin (GB; gray shading) with locations of pine-nut homelands (position of boxes) as inferred from the Theft of Pine Nut (TPN) variant narratives. Numbers in boxes refer to the TPN versions (Table 1). Regions: NW, northwest; WC, west-central; SW, southwest; NC, north-central; NE, northeast; SRP, Snake River Plains; SE, southeast; NUT, northern Utah; ESH, Eastern Shoshone.

Descriptions of enormous ice barriers appear to indicate glaciers or large permanent ice fields. How did people living in the GB learn about towering ice barriers and write of them in TPN narratives? We consider candidate glacial periods for these descriptions.

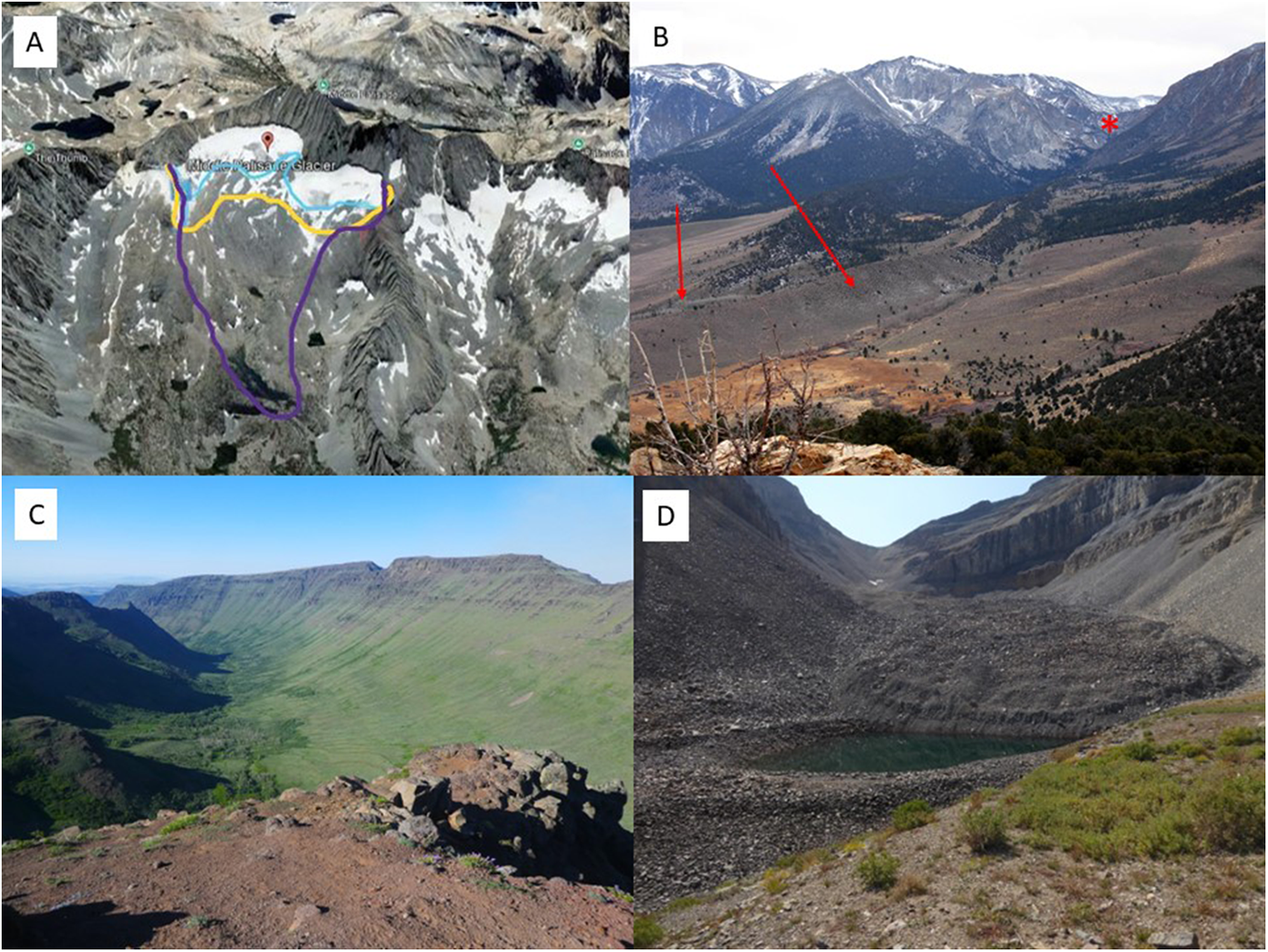

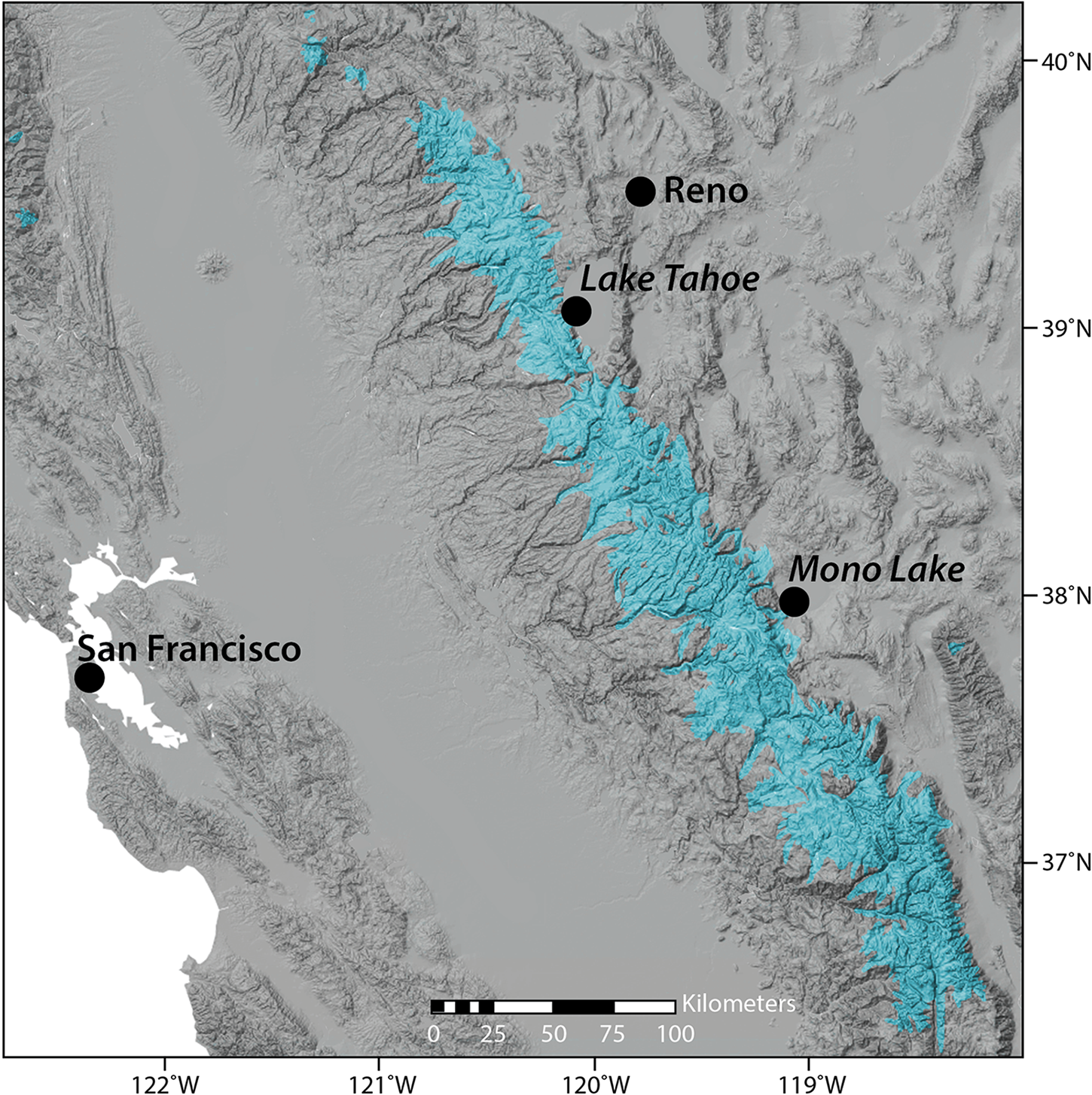

Currently (post-1920 CE) ice glaciers in the GB occur only in the Sierra Nevada, CA (Fig. 6A). Many GB mountain ranges support small rock glaciers (ice-embedded features covered with thick rocky mantles) high in cirques (Millar and Westfall, Reference Millar and Westfall2019). Persistent ice on the headwalls of two GB rock glaciers has been considered glacial (Osborn and Bevis Reference Osborn and Bevis2001), but one in the Wasatch Range, UT, fully melted in the twentieth century (Fig. 6D), and the other, in the Snake Range, NV, melts in warm years and reforms only as a small ice field. The remaining non-glacial ice patches in GB ranges are very small (mean area excluding the Sierra Nevada < 1 ha; Millar and Westfall, Reference Millar and Westfall2019) and are plastered as thin veneers against their cirque headwalls—they are unimposing, hard to see, and present no barrier to passage over or around mountains.

Figure 6. Glaciers of the Great Basin (GB), last glacial maximum (LGM) to present. Ice glaciers exist in the GB currently only as small features in the Sierra Nevada; small ice-embedded rock glaciers also occur currently in several GB ranges. (A) Middle Palisade glacier, Sierra Nevada, CA. Blue line shows extent of the modern glacier, one of the largest in the range. Yellow line shows the extent of the Little Ice Age glacier. Purple line shows the extent of the Recess Peak (late Pleistocene) glacier. (B) Bloody Canyon, Sierra Nevada, CA. The LGM glacier filled the canyon marked by the red asterisk, and extended significantly beyond the range front (red arrows show moraines). (C) Giger Gorge, Steens Mountain, OR. A massive LGM glacier filled the canyon, and an ice cap covered the summit plateau. (D) Timpanogos rock glacier, Wasatch Mountains, UT, typical of features that dominated GB ranges through cold periods of the Holocene. Embedded ice is buried under a thick rock mantle.

During the Little Ice Age (LIA; 1450–1920 CE; Grove, Reference Grove2019) small glaciers advanced in three GB ranges (Sierra Nevada, CA/NV; Wasatch Mountains, UT; Steens Mountain, OR; Osborn and Bevis, Reference Osborn and Bevis2001). All LIA glaciers were small, high in cirques (>3100 m), and did not extend far from the headwalls (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Clark and Gillespie1994; Clark, Reference Clark1995; Millar and Westfall, Reference Millar and Westfall2019; Fig. 6A). These might have been seen by hunters traveling to the alpine zones, but no LIA glacier in the GB would come near descriptions in TPN narratives. The next older, Early Neoglacial, advances (3800–1400 cal yr BP) were almost entirely expressed as rock glaciers in the GB, some of which doubtlessly had thin ice fields adhering to cirque headwalls (Millar and Thomas, Reference Millar and Thomas2024b). These also would not have produced ice barriers fitting the TPN descriptions. No earlier glacial periods are known in the Holocene GB.

We are left considering LP glaciers as models for the TPN ice barrier. The final advances of Pleistocene glaciations in the GB were two brief but distinct glacial intervals: the Recess Peak in the Sierra Nevada (Gillespie and Clark, Reference Gillespie and Clark2011; Fig. 6A) and the Younger Dryas in a few of the high interior ranges (Osborn and Bevis, Reference Osborn and Bevis2001; ∼13–11.7 ka). Ice glaciers of these ages would have been apparent to human observers, as the largest ones extended ∼5 km downvalley, and conceivably could have impeded travel, although ice depths were shallow, moraines low, and canyons narrow. Cross-mountain and trans-canyon mountain travel would have been readily possible despite these glaciers, and they seem unlikely to have made an impression on people as massive or imposing barriers.

During the last glacial maximum (LGM; ∼21–18 ka) massive glaciers formed that filled long U-shaped valleys and left towering moraines in the GB (Fig. 6B and C). In the eastern Sierra Nevada, LGM glaciers extended more than 25 km from summit to terminus (Wahrhaftig et al., Reference Wahrhaftig, Stock, McCracken, Sasnett and Cyr2019a) and had depths to 300 m. In the interior, LGM glaciers extended 10 km, often far beyond the mountain range fronts, and had ice depths > 85 m (Munroe and Laabs, Reference Munroe, Laabs, Lee and Evans2011). Some GB ranges had extensive ice caps that covered the summit plateaus and high slopes of the mountains and fed ice into massive valley glaciers. Ice caps and their derivative valley glaciers are a candidate source for the eyewitness descriptions of ice walls in many of the TPN narratives due to their size, height, and difficulty to cross. If so, these LGM descriptions would have been added to later TPN oral-history narratives.

Biodiversity in the TPN narratives

The animals in the TPN narratives are important characters, playing roles that relate to their natural ecology as well as characteristic, stylized personalities. Coyote, for instance, is commonly present in the pine-nut narratives, reflecting the widespread distribution of coyotes (Canis latrans) across the GB. Coyote is also a trickster, often one who makes mistakes but who, in the end, regularly plays a heroic role that helps other Animal People or restores moral balance (Danberg, Reference Danberg1968).

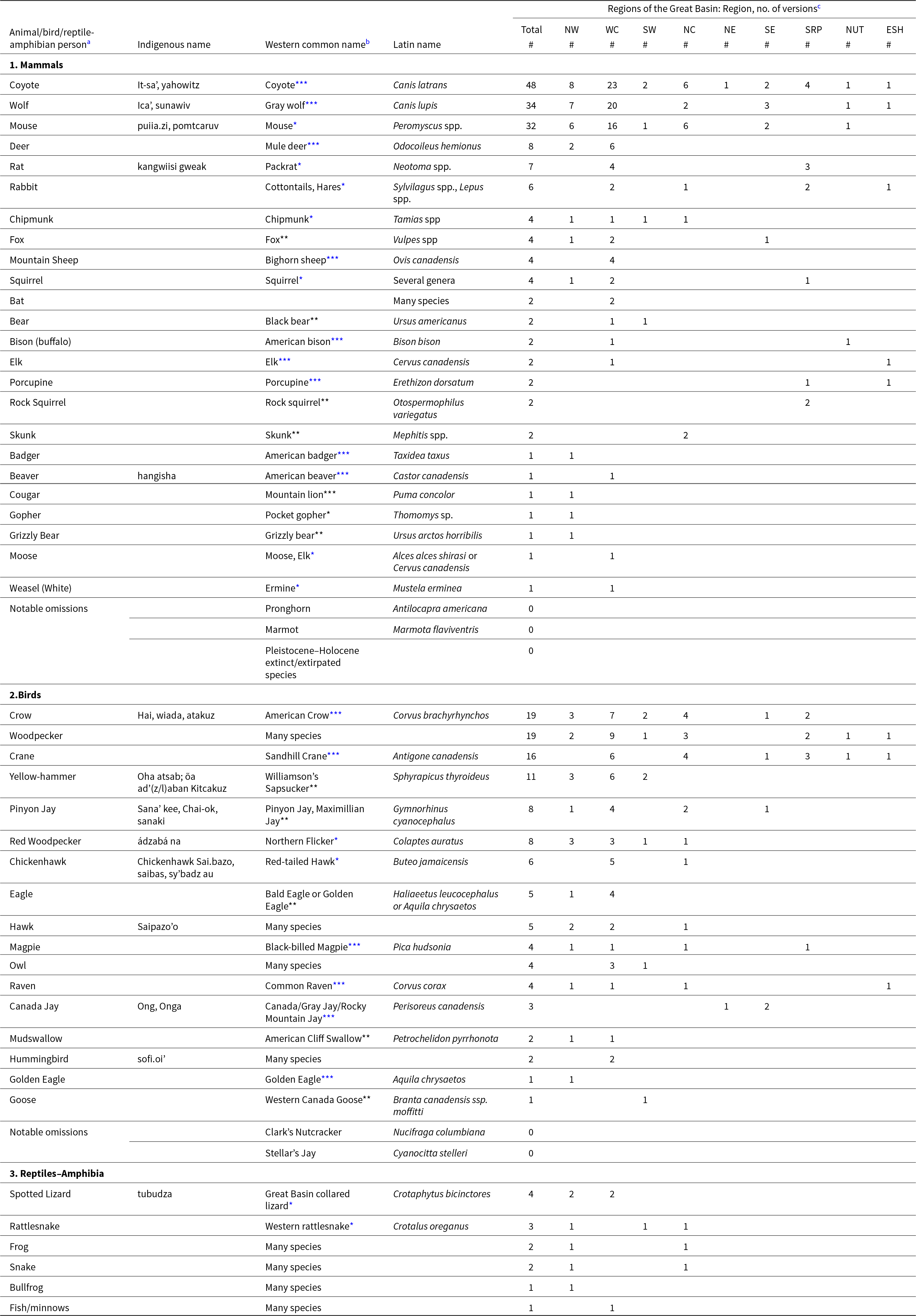

From the TPN versions we compiled 24 mammal taxa, 17 birds, 6 reptiles/amphibia, and 1 fish (Table 3, Supplementary Material, Supplemental Table 1). TPN versions had different numbers and diversities of animals, reflecting the ecology of the narratives’ geographic homelands and the importance of the animals to the plot of the story. The characters Coyote, Wolf, and Mouse had the greatest representation among mammals, occurring in 48, 34, and 32 versions, respectively (Table 3). The remaining mammals occurred in eight or fewer versions, with seven occurring in only one. The latter included taxa likely rarer in Middle–Late Holocene GB landscapes than at present (cougar, Puma concolor), species that became extinct in the GB (grizzly bear, Ursus arctos horribilis), and also common species (gopher, Thomomys spp.; weasel, Mustela spp.) or marginal (moose, Alces alces shirasi). Notable omissions from the narratives were pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) and marmot (Marmota flaviventris). No extinct LP or Holocene species appear to inhabit the narratives.

Table 3. Compilation of mammals, birds, and reptiles in the Theft of Pine Nuts (TPN) oral-history narratives.

a “Animal Person,” Bird Person,” and “Reptile−Amphibian Person” refer to characters in the TPN versions.

b Asterisks indicate level of confidence in species-level identification: *low; ***high.

c NW, Northwest; WC, West Central; SW, Southwest; NC, North Central; NE, North East; SE, South East; SRP, Snake River Plain; NUT, Northern UT; ESH, Eastern Shoshone-Wind River. See Fig. 5 and Supplementary Material, Supplemental Table 1.

Among the geographic indicator species, grizzly bear ranged historically into small regions of southeast Oregon, far northwest Nevada, and central Utah (Mattson and Merrill, Reference Mattson and Merrill2002; Supplementary Material, Supplemental Fig. 1A). Similarly, although black bears (Ursus americanus) occur at present only around the margins of the GB, their historic range is estimated to include some high mountain ranges of central Nevada (Lackey et al., Reference Lackey, Beckmann and Sedinger2013; Supplementary Material, Supplemental Fig. 1B).

Crows, woodpeckers, and cranes are the most common of 17 bird taxa mentioned in the TPN narratives (Table 3). Eleven specified Yellowhammer (woodpeckers) and eight described Pinyon Jay (Gymnorhinus cyanocephalus) and Red Woodpeckers. The remaining taxa are mentioned in six or fewer versions; Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) and Goose (Branta spp.) each are mentioned in only one. Notably, members of the crow family (Corvidae) make up one-third of all bird occurrences. Given the focus on corvids, it is unusual that Clark’s Nutcrackers (Nucifraga columbiana), common in the pinyon woodlands and a primary pinyon-nut disperser, do not appear in any TPN narratives. The hero character in a Wá∙šiw story (no. 52) who brings the pine nut to the People was a “large black and white bird that walked but did not fly.” Clark’s Nutcrackers are black and white and disperse pine nuts, but fly. No extinct birds known from the GB meet this description (Grayson, D.K., personal communication, 2024).

As with mammals, several of the bird taxa are geographic indicators. Crane (Greater Sandhill Crane, Antigone canadensis) is especially useful, because its breeding ranges dip into the GB only in the far northwest corner (Warner Mountains region, CA/OR/NV), the Owyhee region of north-central Nevada, south-central Idaho, and far NE Utah and E Idaho (BirdLife DataZone, 2024–2025; Supplementary Material, Supplemental Fig. 1F). In that the breeding ranges of cranes appear to be similar in the Holocene GB as today (Drewien and Bizeau, Reference Drewien and Bizeau1974), we used these regions to locate pine-nut homelands in the oral narratives. Yellowhammer is also a useful geographic indicator. This most likely refers to Williamson’s Sapsucker (Sphyrapicus thyroideus), as it is the only woodpecker in the region that has yellow plumage. In the GB, Williamson’s Sapsucker occurs year-round along the eastern Sierra Nevada (CA/NV) north to the Warner Mountains, and has only a few breeding locations in NW Nevada and central Utah (BirdLife DataZone, 2024–2025; Supplementary Material, Supplemental Fig. 1G). Canada Jay (Perisoreus canadensis) dips into the GB in a few spots in eastern Utah and the NW GB (BirdLife DataZone, 2024–2025; Supplementary Material, Supplemental Fig. 1H).

Ecological/physical features in the TPN narratives

Topographic features

The most recognizable and useful elements for georeference in the TPN narratives are named topographic features. We assume the place-names given by the translators are generally the same features as those told in the native languages (Supplementary Material, Supplemental Table 1). These include named local hills (e.g., “Chinese Hat, buttes near Owyhee,” no. 7); prominent mountains (“Yamsi Mountain and Gearhart Mountain,” no. 5); lakes (“Pyramid Lake,” told in many versions), hot springs (“From Austin they went on their way north and camped by the hot spring at Beowawe.” no. 9); and rivers (“He chased him north and Lizard jumped in the Reese River.” no. 36).

Although mountain ranges are commonly mentioned, there is almost never definite indication for the location. One exception is narrative no. 39, where the range is clearly identified (“Wolf stood on the Stillwater mountain range”), otherwise, identification to a specific mountain range can only be interpreted by the general region of the narrative. Some topographic features are given that are generic names in the Indigenous language and do not refer to specific (English) place-names, while some names refer to many places with the same modern name, such as the use of “pine nut” for a mountain (“They lived in the eastern Pine-Nut Range.” no. 19; “He made them on the side of Pinenut Mountain.” no. 21; “And this is the origin of piñon trees around Tiva Kaiv, Piñon Nut Mountain.” no. 34). These are useful for georeferencing only when other nearby locations can be identified.

Fire and smoke

Fire and smoke commonly occur in TPN, mostly in reference to detecting pine nuts, either before the theft occurs, giving a clue to where the pine nut trees are located, or after the nuts are brought back, indicating that the theft was successful and pine-nut trees were established. These explicitly or implicitly refer to pine-nut processing over a fire, which was the primary method for preparing pinyon cones and seeds for consumption (Madsen, Reference Madsen, Condie and Fowler1986). Fifteen variants reference smelling pine nuts or fires as they are prepared (Supplementary Material, Supplemental Table 1). These derive from the NC, WC, SW, NW, and ESH subregions. An additional category that may refer to smoke occurs in seven variants, including the NW, SW, NC, ESH, and 4CR subregions (for codes, see Fig. 5). Those involve initial detection of pine nuts by Coyote, who chokes, spits, bleeds, or otherwise is distressed on detecting pine nuts at a distance.

Role of the rotten, stinking, or sore leg

Thirty-two versions, from all GB subregions except the ESH (Fig. 5), include the theme of a bird, usually hawk (rarely Coyote), carrying the pine nut after the theft in a rotten, sore, or stinking leg. The leg is cast off upon reaching the thieves’ homeland, thus planting pine-nut trees. We interpret the role of the rotting leg to suggest mulching of pine nuts, which hastens their germination, as when pine nuts are planted by birds in autumn.

Pine-nut homelands

Cardinal directions of the pine homelands relative to the narrator’s lands are valuable in determining the location of pinyon origins. This information is given in 41 versions; 27 indicate pine homelands north of the narrator’s land, 7 indicate east, 4 indicate west, and 3 indicate south (Table 4). Using all clues available, we propose that 23 versions describe locations where both the pine homelands and the narrators’ or thieves’ locations are within current pinyon distribution ranges (Table 4, Figs. 1 and 5). Twenty-four do the opposite: the pine homelands and the narrator’s land are outside the current pinyon pine ranges. In the remaining 14 variants, there is a mixed condition: the pine homelands or narrator’s land is outside the current pinyon range. Of most interest are the 38 versions that locate the pine-nut homeland outside the current pinyon distribution. These cluster, with exceptions, in three regions: greater Warner Mountains region (11 versions), Owyhee (7 versions), and Pyramid Lake (7 versions). Other pine-nut origin locations beyond the current pinyon range include Lemhi/central Idaho/W Wyoming (four versions), Humboldt Sink/Humboldt Range (three versions), and Santa Rosa Range (two variants). Versions from southern Oregon, Wasatch Range, southern Idaho, and Goose Creek Mountains had one version each. We discuss these further in the following sections.

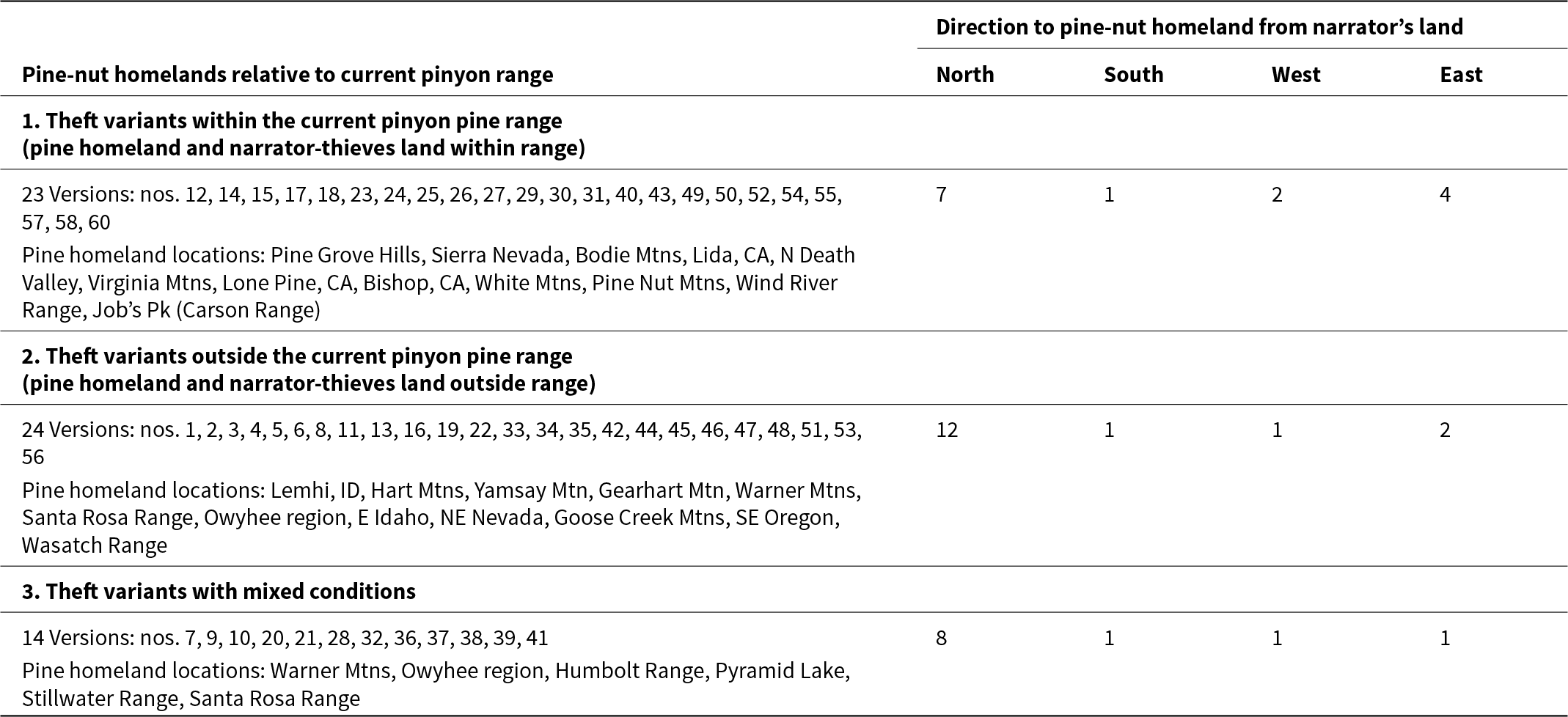

Table 4. Pine-nut origins (homelands) in the Theft of Pine Nuts oral-history narratives and direction to pine-nut homeland.

Warner Mountains region

The Warner Mountains, reaching summits above 3000 m, extend north-to-south for 150 km in NE California and S Oregon. The range is bordered by Warner and Surprise Valleys on the east, and Goose Lake Valley on the west, all of which contain wetlands that are key Sandhill Crane habitat. In the surrounding region are Yamsay and Gearhart Mountains, 95 km and 55 km, respectively, west of the Warner Mountains, and the Hart Mountains, 35 km to the northeast. The nearest pinyon population currently known is ≥200 km south, in the Reno, NV, area.

We determined these locations from direct descriptions, that is, place-names, and from indirect clues. The most important of the latter was the direction the pine-nut smell was coming from relative to the narrator’s homeland and the presence of indicator species, Sandhill Cranes (“Crane People”) and/or Williamson’s Sapsucker (“Yellowhammer”) in the pine-nut homelands (Supplementary Material, Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Fig. 1F and G).

Owyhee region

The Owyhee region comprises rolling desert plains in north-central Nevada and SW Idaho that are cut by tributaries of the Owyhee River and form a vast canyon/plateau landscape. Much of this region lies in the Snake River basin, outside the hydrologic GB. We determined this area from direct place-names, as well as direction of the pine-nut smell, and reference to Crane People. Greater Sandhill Cranes breed in the Owyhee region (Supplementary Material, Supplemental Fig. 1F). The nearest known pinyon pine population is >145 km south.

Pyramid Lake region

Pine-nut homelands are directly named as Pyramid Lake in six TPN narratives and implied in one other. Lying within the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada, the region has a very dry climate, and low elevations induce high summer temperatures. The ranges around the lake are either treeless or dotted with juniper (Charlet, Reference Charlet1996). The northernmost occurrence of pinyon’s primary distribution is in the Virginia Range, >50 km south of Pyramid Lake. A few isolated modern occurrences nearer to Pyramid Lake (University of Nevada, Reno Herbarium voucher) appear to be recent colonists.

Other regions outside the current pinyon range

Several TPN narratives describe pine-nut homelands in other locations outside the current known pinyon distribution. In three TPN narratives (nos. 20, 16, 3) we infer the homelands to be the area of the Humboldt Sink and Humboldt Range, NV. The nearest pinyon population is currently in the Stillwater Range, 55 km east. Two versions (nos. 8, 61) locate the homeland in the Santa Rosa Range. The nearest known population is 150 km south. TPN narrative no. 51 describes both the narrator’s home and the pine-nut homelands as the Goose Creek Range, NV/UT/ID. While pinyon currently grows in the neighboring Grouse Creek and Raft River Mountains, UT, it has not been found in the Goose Creek Range (Charlet, D.A., personal communication, 2011). The nearest pinyon stand is ∼10 km east. One version (no. 34) indicates the pine-nut homeland near Salt Lake City; currently pinyon grows ∼60 km distant. Four TPN variants (nos. 1, 44, 45, 47) refer pine-nut homelands to locations north and northeast of the GB, two in the Snake River Plains, likely around Lemhi, ID, and two (nos. 44, 45) from the northern Rockies, WY (Fig. 5). The closest pinyon stands currently occur 250 km south of the Idaho locations and 235 km southwest of the western Wyoming location. A single version (no. 48) locates the pine homeland in southern Idaho, ∼40 km north of the Albion Mountains’ current populations.

Pinyon pine homelands within the current pinyon range

The remaining versions place pine-nut origins within the current known pinyon distribution range (Table 4, Supplementary Material, Supplemental Fig. 1).

Discussion

Assumptions and biases

As with all paleoecological proxies, Indigenous oral-history narratives have biases in how accurately they reflect histories of interest to Quaternary sciences and in assumptions that underlie their use. We outline key biases and assumptions in our study, recognizing that future work in the fields of pinyon paleoecology, GB archaeology, and Indigenous oral narratives will help to clarify these issues.

Ice barriers

In our analyses of the ice-barrier motif in the TPN narratives, we have assumed the reference is to permanent—glacial—ice, not seasonal snow. As we documented, seasonal snow, although certainly difficult to walk through when deep, is discounted directly in several versions and in other versions the descriptions indicate “ice” that is not possible to cross, high walls and barriers, and descriptions of “formidable” character, which we assume are unlikely to reference seasonal snowpacks.

Indigenous migration into and across the GB

We assume the core plot of the TPN and related narratives (theft/arrival of pine nuts) is ancient, potentially originating at the time when pine nuts first became important to people in the GB (early Middle Holocene; e.g., Rhode and Madsen Reference Rhode and Madsen1998), and that the narrative moved throughout the GB as people migrated. This begs a question about localization of the narrative: Did people accommodate the story to their geography faithfully to where pine nuts grew in their region, or did they adopt local geography to the story randomly with no reference to pine-nuts? While this remains an open question, we assume the former, as outlined below.

Current understanding of people migrating into the GB indicates a genetically unified and geographically coherent path across Beringia and southward into North America and the GB (Moreno-Mayar et al., Reference Moreno-Mayar, Vinner, de Barros Damgaard, De La Fuente, Chan, Spence and Allentoft2018; Willerslev and Meltzer, Reference Willerslev and Meltzer2021; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Cossette, Benner, Camp and Robinson2025). This discredits former hypotheses of immigration into the continent from the west (South Pacific) via the Pacific Ocean or overland from the east (western Europe) via Greenland. The most accepted timeline for entry into the GB is via the northwest part of the region after 15,000 years ago (as outlined in “Antiquity of TPN Narratives”). GB Paleoindians (pre-9000 cal yr BP) settled along marshlands that fringed GB pluvial lakes, where they exploited large game as well as lower-ranking resources that were abundant in the wetlands (Thomas and Millar, Reference Thomas and Millar2024). Desiccating wetlands toward the end of the Early Holocene triggered transition to new subsistence systems, initially focusing on remaining marsh resources as lakes dried (Madsen, Reference Madsen, Hershler, Madsen and Currey2002, Reference Madsen, Graf and Schmitt2007; Zeanah, Reference Zeanah2004). Paleoindian sites in volcanic uplands also were used at this time, indicating fanning-out movements that included forays into the uplands (Smith and Barker, Reference Smith and Barker2017; Puckett, Reference Puckett2023). Thomas and Millar (Reference Thomas and Millar2024) outline the subsequent dispersal of post-Paleoindians through the central, western, and eastern GB. They document that the concomitant migration of pinyon pine in the GB facilitated these movements as people shifted to strong dependence on pine nuts. Thus, the peopling of the GB is a story of movement through the LP and into the Middle Holocene and related to pinyon pine. Increasing stability occurred as groups settled in local areas, becoming the geographically associated communities recognized today.

Given this history, why do we accept the assumption that the TPN narratives faithfully identify pine-nut geographies of their local regions rather than localities unrelated to pines? First and importantly, we base this on the authority of oral-history scholars reflecting the role of geography in oral narratives generally. The Indigenous priority on space and place helps to explain why Indigenous oral history is so closely tied to ancient landscapes, reflecting place-bound interactions with spirits, ancestors, and one another (Deloria, Reference Deloria1973; Van Dyke, Reference Van Dyke, David and Thomas2008; Fixico, Reference Fixico2024). The conviction that “wisdom sits in places” (Basso, Reference Basso1996) runs deep in North American oral history, because “place-making involves multiple acts of remembering and imagining … place-names describe what was seen by those who named the places, and are useful indicators of how the environment of a place has changed over time” (Zedeño et al., Reference Zedeño, Pickering and Lanoë2021, p. 311).

Also critical is the strong dependence that Indigenous people had on pine nuts once they inhabited pinyon pinelands (Steward, Reference Steward1933, Reference Steward1938; Madsen, Reference Madsen, Condie and Fowler1986; Rhode and Madsen, Reference Rhode and Madsen1998; Thomas and Millar, Reference Thomas and Millar2024). Locally, people would have known their pine regions very well, and they would have traveled some distances to procure them. Local names, described in the tribal languages, are indicated in the TPN narratives as well as being translated into English, modern place-names.

More generally, Indigenous oral narratives that have been interpreted as eyewitness accounts, such as catastrophic physical events, are told only within the region of the specific event (eruption, tsunami, megaflood) and do not proliferate outside the region (Budhwa, et al., Reference Budhwa, Mackenthun, Mucher, Mackenthun and Mucher2021). This is true even where volcanic eruptions, for instance, occurred in other regions nearby. Considering the Mazama eruption and the Indigenous oral history describing it, a reasonable assumption might be that people in adjacent regions would adopt a “Mazama story” to their local volcanic eruptions. To the contrary, however, Holocene eruptions occurred in the GB (e.g., Mono-Inyo craters, Modoc volcanic field), yet no Mazama-like narratives were adopted to those local geographies.

Further argument is the persistence of eyewitness-account oral narratives locally long after they occurred. The Mazama eruption, Cascadia megathrust earthquake/tsunami, and Columbia River superflood oral narratives are still told in their local regions despite the fact that they refer to millennia-old events (Budhwa et al., Reference Budhwa, Mackenthun, Mucher, Mackenthun and Mucher2021). Similarly, we document that many TPN narratives are told outside the region of current pinyon pine occurrence, and argue that, as in the Mazama–Cascadia–Columbia cases, the people have deep memory of their local situation (i.e., when pinyon grew there) embedded by stories told in situ. People whose ancestry had no experience with pinyon (e.g., outside the GB) would have no touchstone for surreptitiously adopting TPN stories, and, thus, we find no pine-nut stories in those regions.

Species of pine nuts in the TPN narratives

The presumed species of conifer in the TPN narratives is singleleaf pinyon pine, due to the geographic locality of the narratives. Pinyon produces cones with large, nutritious nuts that were—and remain—singularly important in Indigenous diets (Steward, Reference Steward1933, Reference Steward1938; Madsen, Reference Madsen, Condie and Fowler1986). The priority of pinyon nuts over other species is widely recognized: the Wá∙šiw people assert the value of pinyon pine in linguistic terms. The word for “my pine-nut lands,” referring to pinyon pine, is similar to the word for “my face,” an intentional association according to Wá∙šiw Elders (Fillmore, Reference Fillmore2017). Ethnographer Margaret Wheat wrote, when referring to pinyon pine, “These nuts [were] virtually the only nuts used by Indians of Western Nevada” (Wheat, Reference Wheat1967, p. 30), and GB pioneering ethnologist and archaeologist Julian Steward concluded that pinyon pines were “the most important single food species wherever it occurs” (Steward, Reference Steward1938, p. 27). In an analysis of 556 GB oral-history narratives, Sutton (Reference Sutton1989) found pinyon pine to be the most common species of 46 food plant taxa mentioned, and concluded that among pines, “only pinyon was identified as food” (p. 244). The pinyon species satisfy, if not prove, the identity of pine-nut species in the TPN narratives for variants that derive within the modern range of pinyon pines. The question becomes more challenging for narratives outside the current distribution of pinyon. We consider the possibility that pine nuts referred to species other than pinyons next.

Limber pine (Pinus flexilis; Madsen, Reference Madsen, Condie and Fowler1986; Rhode and Rhode, Reference Rhode and Rhode2015) is the most likely candidate as a food item. It currently grows at subalpine elevations in many GB ranges, including several north of the current pinyon range limit (DataBasin, 2024) in areas of a few TPN versions. Limber pine nuts are not as large, have different nutritional value from the pinyon pine species, and are more difficult to procure than pinyon nuts (USDA, 2024). Cones open at maturity, and most often cones are chewed apart on the tree before maturity by Clark’s Nutcrackers or taken by tree squirrels. Although limber pine nuts clearly were used, pinyon was favored when present (Rhode and Madsen, Reference Rhode and Madsen1998).

Several other pine taxa are mentioned in diets of Indigenous people of the GB. Sugar pine (Pinus lambertiana) has large and nutritious seeds (Farris, Reference Farris1982) that are contained in very large cones and have been documented to have been collected. Sugar pines do not, however, start producing seed cones until trees are ∼150 years old (USDA, 2024), and cones are borne high in the crowns of very tall trees (often >60 m tall), making them difficult to access. Sugar pine grows only in two small areas that overlap some TPN versions, the Wá∙šiw territory of the Tahoe Basin/eastern Carson Range and the far northwest margin of the hydrologic GB (DataBasin, 2024). Sugar pines occur in very low frequency within mixed-conifer forests and would have been unlikely to provide a significant proportion of Indigenous diet.

Whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis) is another candidate species for pine nuts in some TPN versions. Growing at high elevations, whitebark pine ranges along the western fringe of the GB, in the eastern Sierra Nevada, Carson Range, Warner Mountains, Yamsay Mountain, and Gearhart Mountain, where it forms the upper tree line. It also occurs sporadically across the northern tier of GB mountains in Nevada, including the Pine Forest Range, Bruneau Mountains/Jarbidge Range/Copper Mountains, Ruby Mountains, and East Humboldt Range, and also in the Wind River Range, WY, outside the GB (DataBasin, 2024). All but the Ruby and East Humboldt are beyond the known range of pinyon pine.

Whitebark pine is unlikely to have been widely used in the Indigenous GB. Unlike other local pine species, cones of whitebark pines have thick scales in which seeds are embedded. The cones do not fall intact to the ground; rather the scales are disarticulated on the tree by their obligate seed disperser, Clark’s Nutcracker, which pecks the seeds out from the pitch-covered cones high in the crowns (Fig. 7). What remains on the ground after the birds have retrieved the nuts are the nut-less scales and naked cone axes. By the time cones are ripe, birds or tree squirrels have retrieved all or nearly all nuts from cones on the tree (Ward et al., Reference Ward, Shoal and Aubry2006); successful collecting by humans requires obtaining the cones before birds do. This requires climbing the trees, as the cones are high in the crown and not readily knocked out, and postprocessing cones to obtain mature seed. Modern nursery practices attest to the difficulty of collecting and processing whitebark pine seeds (Supplementary Material, Supplement 2).

Figure 7. Whitebark pine cones and seeds. (A) Mature seed cone on tree. (B) Mature seed cones high in tree crowns. All cones have been completely chewed while on the tree by Clark’s Nutcrackers, the obligate seed disperser for whitebark pine seeds. (C) Cone axes and disarticulated scales remain on the ground after Clark’s Nutcrackers have taken seeds while cones are in the crowns. (D) Comparison of seed sizes between pinyon pine (left) and whitebark pine (right).

Ethnographic evidence for whitebark pine is sparse in the GB. Steward (Reference Steward1938, p. 28) noted consultants describing whitebark pine seeds as “too small and too greasy and trees too difficult to climb to make them profitable.” Paiute and Wá∙šiw coauthors do not recognize the species as a food source. Outside the GB, in the region of one of our outlying TPN versions (Eastern Shoshone, no. 45), a complex of high-elevation alpine villages known as High Rise Village occurs at upper tree line in the Wind River Range (Adams, Reference Adams2010). It was long assumed that the people harvested local whitebark pine nuts. A thorough analysis, however, of lipids from grinding stones and ceramic artifacts (Stirn et al., Reference Stirn, Sgouros and Malainey2023) revealed many dietary plants but no evidence for whitebark pine.

Ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) is the final candidate we consider for pine nuts north of the current pinyon range. The species occurs at low- to mid-montane elevation along the far western and northwestern margins of the GB. Small, isolated populations exist in the south-central GB (DataBasin, 2024) that might have been more extensive in the Early Holocene. Cones are produced high in tall trees and open to allow small, winged seeds to disperse. Although ponderosa seeds were used (Couture et al., Reference Couture, Ricks and Housley1986; Kennedy Reference Kennedy2018), their small size and the difficulty of obtaining cones would make ponderosa seeds a lower-value resource (Yanovsky, Reference Yanovsky1936; Farris, Reference Farris1982).

Importantly, of the 38 TPN versions whose pine-nut homelands we interpreted to lie north of the current pinyon range, 18 are in areas where none of the alternative species now grows (Supplementary Material, Supplemental Table 2). Given this and the absence of alternative nut species in many versions within the current pinyon range, we provisionally conclude that, even in regions where pinyon pines do not now grow, the TPN narratives likely refer to pinyon pines.

Antiquity of TPN narratives

Our review of glaciations in the GB from the present to the LP suggests that only during the LP would the amount of ice and glacial distribution approach the descriptions of ice barriers included in many TPN narratives. One pinyon-origin narrative includes an additional clue. A Wá∙šiw story (no. 52) describes the hero bird that brought pine nuts to the People, and begins as follows, “They [the large black-and-white bird, and his companions] were walking along the tops of the mountains, following the ice. It was melting, and they liked it cold, so that’s why they were following the ice.” Assuming the location to be the high mountains around Lake Tahoe (core of the Wá∙šiw homeland), this reference suggests conditions of the LP, given that the Animals were following ice along the tops of mountains. The large Sierra Nevada LGM ice cap extended to the Tahoe Basin area (and northward) west of the hydrologic divide (Gillespie and Clark, Reference Gillespie and Clark2011; Fig. 8). Animal People walking along “mountain tops” following ice could refer to the ice cap margin at the hydrologic divide. Recess Peak glaciers also may have created ice rims along the range crest. Reference to “melting” may indicate deglaciation phases of either glacial interval.

Figure 8. Extent of last glacial maximum ice cap, Sierra Nevada, CA/NV. Modified from Gillespie and Clark (Reference Gillespie and Clark2011, p. 448; with permission from Elsevier).

To consider LGM glaciers as reference for the ice barriers requires that we review dates for the first peopling of the Americas, in particular the GB. Two date ranges are currently debated. Abundant evidence exists for Paleoindians living in the GB by 12–15 ka (reviews in Moreno-Mayar et al., Reference Moreno-Mayar, Vinner, de Barros Damgaard, De La Fuente, Chan, Spence and Allentoft2018; Willerslev and Meltzer, Reference Willerslev and Meltzer2021). A secure ag of 14.1 secure date ka on an anthropogenic locust cache is the oldest for the western GB (Pellegrini et al., Reference Pellegrini, Hattori, Benson, Southon, Song and Woller2022) in the region of many of our TPN versions. But given that LGM deglaciation was complete by 15 ka in GB ranges (Laabs et al., Reference Laabs, Munroe, Best and Caffee2013; Munroe, Reference Munroe2018; Wahrhaftig et al., Reference Wahrhaftig, Stock, McCracken, Sasnett and Cyr2019b), people would not have seen glaciers as they arrived. An earlier arrival of people in North and South America, before and during the LGM, is gaining some acceptance (>20 ka; Becerra-Valdivia and Higham, Reference Becerra-Valdivia and Higham2020; Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Bustos, Pigati, Springer, Urban, Holliday and Reynolds2021; Gruhn, Reference Gruhn2023; Pansani et al., Reference Pansani, Dantas, Asevedo, Cherkinsky, Vialou, Vialou and Pacheco2023; Pigati et al., Reference Pigati, Springer, Honke, Wahl, Champagne, Zimmerman and Gray2023; Stoffle et al., Reference Stoffle, Van Vlack, Lim, Bell and Yarrington2024). While the ages remain debated for many of these sites, if people had been in the GB before ∼17 ka—or recalled massive ice elsewhere (Arctic)—this oral history could have been passed to storytellers relating the TPN narratives.

We tentatively propose that the ice-wall descriptions appearing in many of the TPN narratives derived from eyewitness observations in the LP and persisted through oral transmission more than 17,000 years. Is there precedence for this antiquity in the GB? One of us (HF) knows a GB Wá∙šiw Creation story notable for its apparent LP age. The story relates a great tsunami in ancestral Lake Tahoe that destroyed villages on its east shore and brought water high on the Carson Range, Tahoe’s eastern flank (Danberg, Reference Danberg1968; Fillmore, Reference Fillmore2017). This tsunami is known from geologic analysis to have resulted after earthquakes along the range-front faults of Tahoe’s west side released a massive landslide (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Schweickert and Kitts2014). This gouged away a section of landscape, creating McKinney Bay, and sent 12 km3 of debris into the lake (compare with ∼2.8 km3 for the 1980 Mt. St. Helen’s eruption in Washington State). The tsunami displaced 33% of the volume of Lake Tahoe and sent water 100 m up the east shore (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Schweickert and Kitts2014). The tsunami has a minimum age of 12 ka, derived from lake-bottom piston cores that passed Mazama ash but did not hit landslide debris, and a maximum age of 21 ka from the LGM moraine that the landslide broke through (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Schweickert and Kitts2014). Delta terraces created by the tsunami at Cave Rock were dated at 19.2 ± 1.8 ka (Dingler et al., Reference Dingler, Kent, Driscoll, Babcock, Harding, Seitz, Karlin and Goldman2009), which falls within the minimum/maximum date range.

Others have suggested that Indigenous oral traditions have deep antiquity. One of the first narratives recognized to have high fidelity with Western science was the oral-history narrative detailing the Mt. Mazama eruption, ∼7700 years ago (Budhwa et al., Reference Budhwa, Mackenthun, Mucher, Mackenthun and Mucher2021). Late Pleistocene examples also exist. Fiedel (Reference Fiedel2007) elaborated details of what he interpreted as human travel through LP Beringia, suggesting that ice barriers of GB oral-history narratives derived from observations of those times. Stoffle et al. (Reference Stoffle, Van Vlack, Lim, Bell and Yarrington2024) compiled oral-history narratives and ethnographic interviews with Elders in the Death Valley, CA, region and compared conditions from these with well-dated geologic events that suggest human occupation in the region 40,000 years ago. Angelbeck et al (Reference Angelbeck, Springer, Jones, Williams-Jones and Wilson2024) document traditional oral-history narratives extending back to the “Time of Transformation” in the Gulf of Alaska region, events that date to the LP. Ruuska (Reference Ruuska2026) investigated ice barrier stories from many GB oral-history narratives in addition to TPN and correlated them with various ages of deglaciation in LP Arctic. Hittman (Reference Hittman2013) considered the walls of ice described in the GB “Ice Barrier” story as being a “historic allusion to the last ice age” (pp. 210–211).

Taken together, we entertain the possibility of eyewitness accounts of LP events being passed through Indigenous oral history. The inclusion of ice walls in the TPN oral-history narratives, importantly, does not imply dates for either pinyon origins or mammal species’ locations.

Implications for high-latitude LP pinyon refugia and Holocene expansions

The TPN narratives provide new evidence that pinyon pine may have grown north of its current known range limit in the LP or Holocene, as proposed by Millar and Thomas (Reference Millar, Thomas and Thomas2024a). The oral-history narratives corroborate potential high-latitude refugia or expansions by their consistent indications of northern origins for pine-nut homelands and by specific locations, including Yamsay Mountain, Gearhart Mountain, Hart Mountain; Warner Mountains; Santa Rosa Range; Pyramid Lake, Owyhee region; Goose Creek Range; central Idaho; and western Wyoming. These pine-nut homelands are above 41.5°N and north of the current pinyon distribution range.

Of the northern pine-nut homelands in TPN, the greater Warner Mountains region has several lines of evidence from Western science suggesting that pinyon may have been present historically and may still occur (Millar and Thomas, Reference Millar, Thomas and Thomas2024a). Although the nearest known native pinyon is >200 km south, botanical observations, ethnographic references, and several unconfirmed twentieth-century observations refer to pinyon (Millar and Thomas, Reference Millar, Thomas and Thomas2024a). In particular, a 1948 herbarium voucher of two old-growth Pinus monophylla specimens was recorded by a prominent botanist from the west slope of the north Warner Mountains (USO Herbarium no. 16444); private landowner constraints have limited recent attempts for us to search for these. Ethnographic references report pine nuts and pine-nut collecting and processing on Bidwell Mountain in the north Warner Mountains (Kelly, Reference Kelly1932). Another ethnographic reference was reported for the west slope of Saddleback Mountain (Eagle Peak, 3016 m) in the south Warner Mountains (1977; Ike Leaf, Hammawi, via Richard Hughes, unpublished report). There are several references in Leaf’s report, the most explicit being the following:

In November they went up to the west side of Saddleback to gather pine nuts. 10-15 people involved in pine nut gathering, with a little hunting at this time; men might help in gathering but women knew how to prepare the pine nuts. Pine nuts taken out of cone by roasting in fire; area about 10-12 ft. across (but no pit), used pine nut tree fire wood, manzanita wood to get hot fire for hot coals. Fine cones stirred with stick until cones pop open (stick of chokecherry wood), then taken out of fire and swept onto a tule mat rug. Chokecherry sticks brought up to the site from the village. Fired cones scraped, by hand or with a small stick, and nuts dropped out and put into a deerskin bag. Pine nut operation may have taken about two weeks from start to finish. After the middle of November they stored and organized; small, shallow (ca. 6” deep) storage pit dug into floor of house covered with tule mats to keep dry. The storage pit was about 4 ft. long, about 1 to 1½ ft wide and about 6-8” deep.

Several other northern regions from the TPN stories suggest reasonable historic pinyon occurrence. Pyramid Lake at present lies ∼50 km north of pinyon’s primary distribution. Four isolated pinyon colonists occur at the southwestern margin of Pyramid Lake (two young trees are likely progeny of the adjacent adult) and a small stand (∼10 ha) exists near the very southwestern edge of the lake, suggesting other trees may exist or have existed in the area. Two versions of TPN locate the pine-nut homeland in the greater Bonneville region, UT, a region also proposed as a northern refugium based on old ages of pinyon in middens (Millar and Thomas, Reference Millar, Thomas and Thomas2024a; Fig. 3). Millar and Thomas (Reference Millar, Thomas and Thomas2024a) consider that in addition to LP northern refugia, pinyon may have advanced north of its current range during favorable Holocene conditions and subsequently been extirpated as conditions deteriorated (see also Betancourt, Reference Betancourt and Everett1986; Neilson, Reference Neilson and Everett1986). Taken together, high-latitude areas identified as northern pinyon homelands in the TPN narratives corroborate and expand Western science hypotheses occurrences of pinyon north of its current distribution. These areas warrant further attention for evidence of prior pinyon occurrence, including field surveys for as-yet-undiscovered northern pinyon stands, new midden analyses, reanalyses of existing pollen data for pinyon-type pollen, and starch analyses on grinding stones for evidence of pinyon.

Implications for pre-contact mammal species distribution ranges

The TPN narratives provide insight into past distributions of several mammal species in the GB. Grizzly Bear was an important character in a TPN story from the Walker Lake area. This location for grizzly bears in west-central Nevada places them outside their reconstructed historic range (Mattson and Merrill, Reference Mattson and Merrill2002; Supplementary Material, Supplemental Fig. 1A)

The TPN narratives also corroborate and extend reconstructions of the pre-contact distribution of black bear in the GB. One version (no. 38) involves black bear in the Pyramid Lake–Nixon, NV, area. This area is outside historic bear habitat considered by Hall (Reference Hall1946) but within Lackey et al.’s (Reference Lackey, Beckmann and Sedinger2013) revision of the historic distribution. Another (no. 18) describes black bear in the Panamint Range (Death Valley area), outside both Hall’s (Reference Hall1946) and Lackey et al.’s (Reference Lackey, Beckmann and Sedinger2013) estimates.

Wolves, a key character in many of the TPN narratives, were widespread historically across North America but hunted to near extinction in vast portions of their former range (Shelton and Weckerly, Reference Shelton and Weckerly2007). Shelton and Weckerly canvassed reports of historic wolf observations and produced a map showing areas of increasing confidence for occurrence (Supplementary Material, Supplemental Fig. 1C). The locations of wolves interpreted from the TPN narratives provide new evidence for regions that had low or moderate confidence in Shelton and Weckerly’s (Reference Shelton and Weckerly2007) evaluations, including Pyramid Lake, Hart Mountain, Warner Mountains, Walker Lake, Bodie Mountains, Lovelock, Stillwater Range, Pine Nut Mountains, Carson Range, Owyhee region, northern Utah, and Wind River Range.

Bighorn sheep were widely distributed in GB mountains but were extirpated throughout their range by overhunting and disease during the contact/settlement era (Buechner, Reference Buechner1960; Supplementary Material, Supplemental Fig. 1D). Archaeological evidence for Indigenous bighorn hunting is ubiquitous across high mountain ranges of the GB in the form of hunting blinds, corrals and wing traps, butchered bones, and associated projectile points (Hockett et al., Reference Hockett, Creger, Smith, Young, Carter, Dillingham, Crews and Pellegrini2013; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Bean, Burns, Canaday, Charlet, Colwell and Culleton2020). Although we might expect that bighorn sheep would be common in the TPN narratives, only four versions, all from the west-central GB, mention the species. Those provide new information on the former range of bighorn sheep for the Bridgeport, CA, region, and mountains to the east, likely the Bodie Mountains, as well as the Warner Mountains.

American beavers were widely extirpated throughout their North American range by over-trapping in the settlement period (Baker and Hill, Reference Baker, Hill, Feldhamer, Thompson and Chapman2003; Gibson and Olden, Reference Gibson and Olden2014). Now found sporadically in streams of the GB, most of those are assumed to derive from intentional or accidental introduction. Controversy remains over beavers’ pre-contact native range in the GB, with most accounts describing it as limited, although some suggest extensive distribution (Lanman et al., Reference Lanman, Perryman, Dolman, James and Osborn2012). Beaver occurs in one TPN story, which takes place in the Pyramid Lake–northern Sierra Nevada region, adding evidence for beavers as native to that area.

Although elk have been introduced into many GB ranges and cougars have expanded populations throughout the modern GB, both were rare pre-contact (Grayson, Reference Grayson2011). Elk occur in two (maybe three) TPN narratives, one outside the GB (Wind River Range, WY), where elk are historically native, and one to two in west-central GB. Elk have long been considered absent from the Sierra Nevada region, but recent evidence suggests they may have been native through the Late Holocene into historic times (Lanman et al., Reference Lanman, Batter and Mckee2024). The TPN narratives corroborate this, and also indirectly validate the rarity of elk elsewhere in the GB. Similarly, only one TPN narrative, in the west-central GB, describes cougar, again indirectly corroborating their pre-contact rarity.

Conclusions

While Indigenous oral-history narratives were never intended to chronicle historical detail, and include aspects beyond the scope of Western science, our assessment of 61 versions of the Theft of Pine Nut narratives, told over 152 years and across the GB, leads us to conclude that many elements represent eyewitness observations of value to Quaternary sciences. High consistency among the versions across the breadth of the GB gives us confidence to interpret paleoenvironmental conditions, to compare these with Western science hypotheses, and to propose ages of longevity for these orally transmitted narratives. We outline new information in the narratives on pinyon pine biogeography, with focus on pine-nut homelands interpreted north of the current pinyon range. Several of these co-occur in regions identified by Millar and Thomas (Reference Millar, Thomas and Thomas2024a) as LP refugia or Holocene expansions with subsequent extirpation. Collectively they corroborate alternative hypotheses of pinyon’s former occurrence north of its current range.

The TPN narratives also add useful content about pre-contact distributions of mammals in the GB. Additional evidence is provided, and new locations indicated, for historic occurrences of grizzly bear, black bear, gray wolf, bighorn sheep, beaver, elk, and cougar.

Our assessment of the TPN narratives is, to our knowledge, unique for assessing ecological dynamics. Previous analyses have assumed that singular and catastrophic geologic events such as megathrust earthquakes, eruptions, and tsunamis were the only events significant enough to be retained in oral tradition. We demonstrated that ecological dynamics ensuing over centuries and millennia are also encoded in the narratives, especially when they relate to a subject, such as pine nuts, that has high survival and cultural value.

Whereas dates and age are difficult to assess in oral-history narratives, we propose that the common appearance of a massive ice barrier in the TPN narratives reflects eyewitness accounts of LP (LGM) glaciers and ice caps. Given the current accepted understanding that people did not arrive in the GB until after 15 ka, LGM deglaciation was complete by that time. Although latest Pleistocene advances (∼13–11.7 ka) might have produced adequate ice reference in the narratives, we think it more likely that inclusion of ice barriers in the TPN narratives resulted from observations in the Arctic or elsewhere before 15 ka and were transmitted through oral tradition as people moved south.

Although we do not argue that the age of glacier observations directly implies ages for pine-nut origins or mammal ranges, we do propose that the TPN narratives have deep antiquity. This is suggested by the large number of variants, general consistency among versions, and their widespread representation among tribal groups. (Budhwa et al., Reference Budhwa, Mackenthun, Mucher, Mackenthun and Mucher2021).

In this study, we sought reliable content in the TPN oral-history narratives as a new type of evidence for reconstructing Quaternary history. Previous work has focused on corroborating Indigenous knowledge using Western science as a “control,” (e.g., Franks et al., Reference Franks, Nunn and McCallum2024) rather than considering that new information might be brought to Western science. We share the perspective with an increasing number of environmental scientists that oral-history narratives can introduce reliable new data useful for testing Western scientific hypotheses and for expanding knowledge broadly. In so doing, the narratives provide new avenues for future paleoecological and archaeological research. For pinyon, this includes searching for field, midden, and pollen evidence of historic pinyon pines at high GB latitudes and reassessing pre-contact mammal ranges in the GB. We have already begun field surveys, and encourage other archaeologists and ecologists to do the same.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Charlet (College of Southern Nevada), Robin Tausch (U.S. Forest Service), and Robert Westfall (U.S. Forest Service) for reviews of the draft manuscript. We are indebted to Scotty Strachan (University of Nevada) and Geoffrey Smith (University of Nevada, Reno) for critical comments as journal reviewers. Authors Millar and Thomas thank our Indigenous coauthors who spent many hours explaining natural history and cultural perspectives on oral-history narratives. We thank Catherine Fowler for her input on Indigenous oral history and for generously providing previously unpublished versions of Theft of Pine Nuts. Thanks to Zeese Papanikolas for providing several new versions of TPN, Richard Hughes for sharing unpublished ethnography from the Warner Mountains, Diana Roberson for archival work, and Jenn Steffey for rendering the maps.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/qua.2025.10039.

Data availability statement

Twenty-four complete versions of the Theft of Pine Nuts narrative are included in Supplement 1 in the Supplementary Material. Transcripts of all 61 versions of the TPN oral-history narrative that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (CIM).