8.1 Introduction

The Hungarian political system after the regime change has become extremely polarised and deep political fault lines have developed between the domestic political communities, so much so that these relations can be described in most cases in terms of hate. Reinhart KoselleckFootnote 1 speaks of so-called asymmetric counter concepts, that is, those cases in which the politically different from us is named and its identity is constructed, but the identity thus created is not necessarily in line with reality or with the self-definition of the person (the ‘political otherness’). The two most important components of the political identity are the aforementioned self-definition and the definition by others (i.e., what others, especially political opponents, think of it). In my view, hatred and the resulting violence (verbal and non-verbal) and its post-2010 constitutional representation have become one of the main structuring factors of the domestic political and social space in such a way that asymmetric counter-concepts have become dominant in the identification war between opposing political sides: this means that almost all possibilities for dialogue between opposing positions have been lost, because the definition and domination of the identity of the other has become the main aspect. Similar processes of attribution and identification have been taking place in the refugee crisis since 2015, and this time the hatred has been directed towards the ‘political other’, only to return to the domestic political scene and further deepen the dichotomies that have become familiar since the regime change. The post-2010 constitution-making process elevated this hostility to the level of the Fundamental Law, which entered into force in 2012, and created a system of Constitutionalised Image of Enemy (CIE).Footnote 2

The defining characteristic of the Hungarian Fundamental Law is its strong constitutional identity: the political identity of the supermajority has become constitutionalised. This identity image has a number of positive elements (i.e., elements that have been defined as desirable, a kind of fundamental characteristic of the public law system). These include Christianity, active memory politics, national cohesion and various aspects of sustainability. In this chapter, I argue that, in addition to the explicitly strong positive constitutional identity elements, the constitutional power intended that negative identity elements should be at least as strong as the positive ones (in many ways even stronger and more important in the daily political struggles relying constitutional identity). These are the pillars of constitutional identity that separate us from others in the political theoretical assumption of Gramsci, Koselleck and Schmitt and define boundaries and political fault lines.

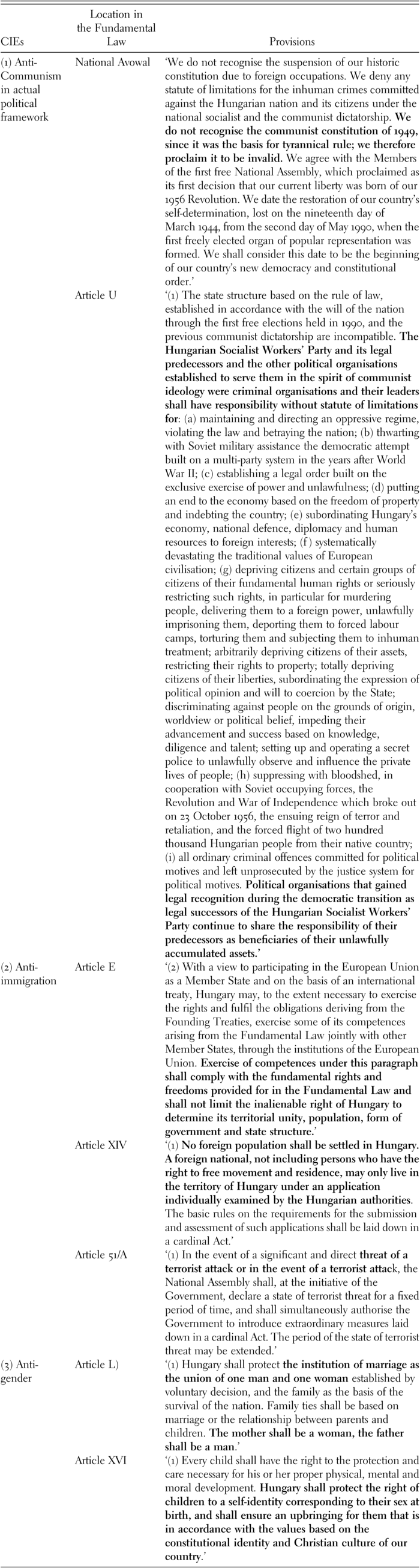

The other main claim of this chapter is that the negative constitutional identity has been presented in the original constitutional conception, which started to unfold in 2010, but also since 2015 (embedded in the amendments to the Fundamental Law) the constitutional enemy formation pervades public law and political debates. Three basic strands of Constitutionalised Image of Enemy (CIE) have emerged (and this reflects the constitution-power’s view of history and the past): (1) anti-Communism framed in actual political framework; (2) anti-immigration; (3) anti-gender as the opposition to non-heterosexual forms of coexistence. I propose that anti-Communism as CIE can be found in the following sections of the Fundamental Law: the ‘Communist Constitution of 1949’ and its declared invalidity; the responsibility of ‘political organisations that gained legal recognition during the democratic transition as legal successors of the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party’. The various aspects of anti-immigration as CIE have been raised to constitutional level (police involvement in preventing illegal immigration; the terrorist threat; the amendment of the constitutional clause on accession to the EU with regard to the inalienable right of disposal of the territorial unit, population, form of government and organisation of the state). The definition of marriage and the constitutionalising of the biological sex of the mother and father represent the anti-gender CIE. I will argue that the mentioned sections are suitable to define the various enemy images for the political community with public law force, and therefore they can be considered as CIE.

The main focus of this chapter is on how the public enemy formation of the mentioned CIEs predominates in Hungarian society, the main political and moral effects and how these may have an impact on the constitutional identity itself, as enshrined in the Fundamental Law.

8.2 Enemy and Identity Construction and the Orbán Regime

8.2.1 Autonomy of the Political Sphere: Friend and Foe Relations

The need to construct the political enemy and the political enemy itself have always been part of politics, with varying degrees of intensity. However, this process intensified with the emergence of modern politics and really began to sprout in the twentieth century. The political sphere became autonomous and emancipated from the state in several ways: the individualist approach of liberalism and the continuing rise of civil rights; the development of capitalism and its globalisation; the transformation of political representation by political parties; and, finally, with the spread of universal suffrage, the emergence of mass politics and mass media. In other words, everything points in the direction of society becoming increasingly detached from the state and, through various forms of regimes (civil rights, consumption, suffrage), essentially becoming the dominant sphere in which political structures can evolve. This process can also be understood as a move away from the elite structures (institutions of public power, rulers, aristocracy) and towards socialisation. It was to describe this new order that Carl Schmitt introduced the concept of the Political (das Politische), reflecting the fact that it is not possible to draw a clear line between the political and the non-political. Schmitt’s concept of the political, however, seeks to provide points of orientation in this new world and sees the essence of the political in the systematic and consistent distinction between friend and foe, which determines political actions and motives. As Schmitt argues:

The political enemy need not be morally evil or aesthetically ugly; he need not appear as an economic competitor, and it may even be advantageous to engage with him in business transactions. But he is, nevertheless, the other, the stranger; and it is sufficient for his nature that he is, in an especially intense way, existentially something different and alien, so that in the extreme case conflicts with him are possible. These can neither be decided by a previously determined general norm nor by the judgment of a disinterested and therefore neutral third party.Footnote 3

He adds to this: ‘… the morally evil, aesthetically ugly or economically damaging need not necessarily be the enemy; the morally good, aesthetically beautiful, and economically profitable need not necessarily become the friend in the specifically political sense of the word’.Footnote 4 According to Schmitt,

the enemy is so basic a category of politics that it is not a metaphor or symbol, but an existential category. In the case of the enemy, a sharp line must be drawn between the private enemy (foe) and the public enemy (enemy): The enemy is solely the public enemy, because everything that has a relationship to such a collectivity of men, particularly to a whole nation, becomes public by virtue of such a relationship.Footnote 5

8.2.2 The Schmittian Concept of RepoliticisationFootnote 6

Carl Schmitt elaborated the dangers of depoliticisation,Footnote 7 the concept of which had a significant impact on the Orbán regime after 2010.Footnote 8 From Schmitt’s perspective, modern politics has become such a complex system that we cannot easily decide what is political and what is non-political. Schmitt aimed to create a very clear boundary to explain what is political and introduced the mentioned category of the Political (das Politische), which is based on separating friends from enemies. Schmitt, summarised by Bellamy and Baehr, ‘blamed the failure of liberalism to appreciate or resist the challenge posed by democracy on its lack of an adequate conception of the political and hence of the state’.Footnote 9 Schmitt’s approach,Footnote 10 elaborated in The Concept of Political, has fundamentally influenced the political advisers around the Orbán’s governments.Footnote 11 According to Schmitt, liberalism is about taking normative decisions and making consensus but, from Schmitt’s approach, there is no consensus in the political sphere or at least it is undesirable. He is convinced that dangers and disputes concerning the political could only be settled through political decision – liberalism denies the relevance of the political. In my point of view this is one of the core elements of current authoritarian populism. After the Hungarian regime change in 1989, the ‘really existing’ liberal democracy has actually shown this anti-political attitude: the political elites and the institutions of liberal democracy weren’t able to build the social and popular base of democracy, moreover no cohesive political community has been created in the decades since the regime change. The liberal democracy established in Hungary has not created and satisfied these popular demands. Orbán promised, on the basis of Schmitt’s perception of politics, to repair this situation, which is why Orbán calls his regime ‘National Cooperation’.Footnote 12

Moreover, as Schmitt stated, liberalism denies the concept of enemy, which is the core element of Schmitt’s theory. This is the reason why liberal democracies hesitate to act as political situations and crises require. According to Schmitt: ‘Liberalism … existed … in that short interim period in which it was possible to answer the question “Christ or Barabbas?” with a proposal to adjourn or appoint a commission of investigation.’Footnote 13 From this point of view, it can be stressed that liberalism tries to depoliticise and neutralise all the political conflicts and turn political battles towards legal and economical fields. Schmitt denied the liberal rationalist’s faith in the ultimate ethical harmony of the world.

Good consequences do not always follow from good acts, or evil from evil ones; similarly, truth, beauty and goodness are not necessarily linked. Most importantly he recognized that we are often faced with difficult or tragic choices between conflicting but equally valuable ends – for no social world can avoid excluding certain fundamental values. In this situation, as Weber insisted, we cannot escape the responsibility of choosing which gods we shall serve and by implication deciding what are to count as demons.Footnote 14

In fact, Weber can be seen in terms of the critique of liberal constitutionalism as a forerunner of Schmitt, even more precisely Weber’s political theory has a significant impact on Schmitt. The main difference between the two is that Weber occupies a position which seeks to incorporate Machiavellian power-politics within a constitutional democratic framework.Footnote 15 For Schmitt, the dilemmas of politics can be solved politically, through political decisions, which take place in the state. Liberalism has no positive and adequate theory concerning the state and that is why liberalism cannot handle pluralism, which is the main source of political conflicts. Schmitt and Max Weber both argued that morals and politics are distinct and problems based on this fact can only be handled in a political way, through political debates and decision, and not from a liberal perspective (metaphysically and through rational discussion).

Schmitt is convinced that the locus of the mentioned political decisions is the sovereign state. The sovereignty of the state is a matter of politics and lies outside of the law. The sovereignty of the state is crucial in understanding why the ‘sovereign is he who decides on the exception’.Footnote 16 The state of exception shows the real nature of politics: ‘The existence of the state is undoubted proof of its superiority over the validity of the legal norm. The decision frees itself from all normative ties and becomes in the true sense absolute’.Footnote 17 According to Schmitt, the legal-based approach of liberalism overlooks that the legal instruments and the rule of law are products of political struggles.Footnote 18 Liberalism is so dangerous for Schmitt because it attempts to deny the need for a sovereign (state) and with this the political basis of law has become questionable.

8.2.3 The Construction of Identities and the Asymmetric Counter Concepts

Koselleck uses historical analysis to shed light on the basic contours of the construction of the identity of the enemy and of one’s own group, since these two processes must take place simultaneously in order to be confronted with politically effective action:

The efficacy of mutual classifications is historically intensified as soon as they are applied to groups. The simple use of ‘we’ and ‘you’ establishes a boundary and is in this respect a condition of possibility determining a capacity to act. But a ‘we’ group can become a politically effective and active unity only through concepts which are more than just simple names or typifications. A political or social agency is first constituted through concepts by means of which it circumscribes itself and hence excludes others; and therefore, by means of which it defines itself.Footnote 19

The construction of identities is, therefore, a very fierce and intense political contest, since self-identification is the very process through which a political community is created. At the same time, the construction of a positive identity of oneself necessarily implies the construction of a perceived identity of the opponent and even more so of the political enemy.

On the basis of all this, we can also say that an integral part of one’s own identity is the definition, and in some cases the domination, of the identity of the opponent/enemy. This is therefore a contest of identity construction, where the identity of the opponent/enemy could of course be defined – by means of counter concepts – in such a way that it fits the self-identification of the given party (symmetry), but the very essence of the contest is to be able to dominate the identity of political opponents/enemies. Analysing the examples of asymmetric counter-concepts across historical periods (Hellenes and Barbarian, Christians and Heathens, Mensch and Unmensch, Ubermensch and Untermensch), Koselleck argues:

… a given group makes an exclusive claim to generality, applying a linguistically universal concept to itself alone and rejecting all comparison. This kind of self-definition provokes counter concepts which discriminate against those who have been defined as the ‘other’. The non-Catholic becomes heathen or traitor; to leave the Communist party does not mean to change party allegiance, but is rather ‘like leaving life, leaving mankind’… not to mention the negative terms that European nations have used for each other in times of conflict and which were transferred from one nation to another according to the changing balance of power.Footnote 20

According to Koselleck, this exclusionary, discriminatory mechanism is realised by means of asymmetrical counter-concepts, since the self-definition of the opponent/enemy certainly does not correspond to the identity elements attributed to him/her:

Thus there are a great number of concepts recorded which function to deny the reciprocity of mutual recognition. From the concept of the one party follows the definition of the alien other, which definition can appear to the latter as a linguistic deprivation, in actuality verging on theft. This involves asymmetrically opposed concepts. The opposite is not equally antithetical. The linguistic usage of politics, like that of everyday life, is permanently based on this fundamental figure of asymmetric opposition.Footnote 21

So, the political enemy is a constructed, created phenomenon – as is self-identity. The most obvious ways of creating the identity of the enemy are to personalise (and through this, character assassination) and criminalise it.

8.3 The Orbán Regime and the Constitutionalised Image of Enemy

In this section, the theoretical framework of the Orbán regime, which has been institutionalised since 2010, will be used to illustrate the tendencies of the Constitutionalised Image of Enemy (CIE). First, the antecedents of the post-2010 CIE-regime and the basic elements of the right-wing’s enemy-constituting identity have been analysed. Reflecting on the 2010 turnaround, the directions in which the Orbán regime has shaped CIEs by the adoption of the new Fundamental Law will be investigated: the constitutional framework of anti-Communism, anti-immigration and anti-gender.

8.3.1 The Roots of Constitutional Enemy Creation before 2010

Among the forces of the political right after the Hungarian regime change, the identity of Fidesz, constructed mainly since the early 2000s, is centred on the previously analysed Carl Schmitt’s conception of politics, moreover it is based on the rehabilitation of the Political (repoliticisation) and unrelenting opposition to liberalism and inferiority complex in relation to liberal (or perceived) academic and political structures. This was accompanied by Koselleck’s thinking in terms of asymmetrical counter-concepts, the main aim of which is the hegemony of one’s own identity and the presentation of the political opponent as an enemy, and in this context the domination of the enemy’s self-identification.

Fidesz has proved to be quite successful in the political identity construction struggle, fuelled by the fact that it has a ‘missionary’ political identity and believes that it is the only party that can and will truly represent national interests. Two things follow from this. Firstly, this has predestined the party, which has been in government again since 2010, to derive its antithesis, the image of the Hungarian left and liberal opposition, from its very strong self-identification. On the other hand, the Fidesz’s linked its self-definition to the question of national identity, and in this way any political identity against Fidesz can be interpreted against the Fidesz-dominated national identity (which is in fact a policy of exclusion from the nation). Another important peculiarity of the identity construction struggle between left and right is that the Fidesz-led right is not only better able to articulate its own identity, but in fact it is itself defining the identity of its opponents at many points.

The emerging Fidesz has linked its identity with the nation, creating an asymmetrical situation in which the left and the liberals can only be identified with the ‘non-national’ character. The right’s thematisation of the national problem dates back to the pre-reform era, and in the case of Fidesz it became a coherent identity element with the beginning of the debates on the settlement of the situation of ethnic Hungarians living in neighbouring countries in 2001. The left criticised the tendency towards ‘national unification’, which from then on was at the centre of the right’s political perception. All this culminated first in the 2002 election campaign and then in the 2004 referendum on the preferential access of the Hungarian citizenship for Hungarians living abroad, where the left and the liberals were seen by the right as having ‘eradicated’ itself from the nation. Gábor Egry aptly describes the technique used by Fidesz:

… a process of self-definition in which the right – In line with its position at the time of regime change – labels itself as anti-communist and labels everyone else as communist, whether they are or not. It is necessarily static, does not allow for nuances and tries to classify everyone and keep everyone in the category it has assigned to them, even if it has nothing to do with the actual situation.Footnote 22

Fidesz has thus begun to define and dominate the communication over the identity of its political opponents.

In essence, Fidesz was able to build on the identity elements and solutions developed here during the 2002–2010 opposition period:

Through symbolic politics and the unity of nation–party–governance, Fidesz tried to get society to accept a new type of cultural nation concept between 1998 and 2002. The downfall of the first Orbán government was also a sign of the forcefulness and majority rejection of this attempt. During its years in opposition, Fidesz successfully developed and established techniques to almost exclusively own the thematization of identity content issues in opposition to the left, liberals and greens. Despite the fact that the debates over the meaningfulness of certain canons and symbols could not be settled in 2002, the Fidesz was able to exploit their positional advantage stemming from the lack of performance of their party political rivals.Footnote 23

After the defeat in 2002, Fidesz interpreted the national aspect of its own identity more and more broadly: this is expressed by the transformation into an alliance and the slogan ‘one camp, one flag’. In other words, it was thinking in terms of a broad identity system that went beyond the previous political camp of the right. The 2006 Fidesz election defeat and the street riots were in fact a dress rehearsal for this identity politics, but they also introduced a new element, namely moral politicisation. According to Márton Szabó, Fidesz then ‘defines the political community as a moral community, i.e., a democratic community whose members are bound together by commonly held moral principles, or at least expelled from the political community by any person or organisation that does not abide by these norms’.Footnote 24

8.3.2 The Emerging Hegemony of the Orbán Regime

The turning point of the right-wing breakthrough in Hungary was believed to have happened in the year 2010, although in reality the process had begun much earlier. Indeed, the Hungarian right spent over a decade (the 2000s) to create a right-wing hegemonic structure in a Gramscian sense. The politics and tactics of Fidesz, the leading right-wing party since 1998, can be analysed from a Gramscian perspective. Fidesz began as a party in government (between 1998 and 2002), and then became the main opposition party (between 2002 and 2010) after a fierce struggle on political, economic and cultural fronts. The party managed to build a complex political and economic network as a historical bloc, which it has used to create a national popular movement (‘civil circles’), thus politicising masses. The right claimed that the successive social-democrat governments (first from 1994 to 1998, then from 2002 to 2010) caused an organic crisis, also in a Gramscian sense, as it was framed within an economic and social crisis, which turned into a crisis of hegemony. This overlapping crisis culminated successively in 2006 (when the right-wing blew out rough street movements because of the moral crisis caused by the scandal surrounding the lies of the incumbent socialist prime minister), in 2009 (when the left-liberal governing coalition collapsed) and in 2010 (when Fidesz reached two-thirds in the parliament for the first time). The left-liberals lost their grip on the superstructures, while the authoritarian right put forward innovative ideas, perspectives and practices. Although the hegemonic project of the right has its roots in nationalism, antagonising rhetoric and xenophobia, it also reflects a Gramscian way of thinking. Fidesz can be seen as a counter-hegemonic project against the left-liberals. This is also true for Jobbik, which is the former leading extreme right-wing opposition party of Hungary.

8.3.3 The Era of Constitutionalised Image of Enemy

After the change of government in 2010, this national and moral identity of the Fidesz was intertwined into a whole and gained public relevance in the Fundamental Law. Fidesz experienced 2010 (hence the winning of the election has been named as a ‘revolution’) as a triumph over the left in both national and moral terms. From 2010, the ‘what is Hungarian’ thinking takes a new turn and aims to create a consistent national identity. The national–moral creed of Fidesz is represented by the much-debated Fundamental Law and its preamble, the National Avowal. The Orbán regime created the asymmetrical counter-concepts based on the identity politics it developed in the opposition period and began to build its own governmental–national identity with a constitutional majority. The Orbán regime’s approach, however, went far beyond the classic Schmittian friend–enemy dichotomy, as the asymmetric counter-concepts developed by the government were incorporated into the Fundamental Law. In this chapter, I therefore refer to the phenomenon of the political identity of the post-2010 Hungarian Orbán regime unfolding within the framework of asymmetric counter-concepts with constitutional binding force as the Constitutionalised Image of Enemy (CIE). The constitutional identity construction of the Orbán regime can thus be considered unprecedented in the history of Hungarian politics after the regime change and at the same time in the history of constitutional identity constructions in that it elevated Koselleckian asymmetrical counter-concepts composed of negative identities excluding others to a constitutional level (Table 8.1). In this section, I will describe the three main nodes of this CIE system: anti-Communism, anti-immigration and anti-gender.

8.3.3.1 Anti-Communism after Twenty Years of the Regime Change

As can be seen on the basis of the above-mentioned parts of the Hungarian Fundamental Law, 2010 brought a new level of enemy thematisation: the category of public enemy. The Fundamental Law’s National Avowal implied an anti-Communist identity, since it declared the 1949 Communist constitution invalid and declared that it denied ‘any statute of limitations for the inhuman crimes committed against the Hungarian nation and its citizens under the national socialist and the Communist dictatorship’.

This was further developed by the Fourth Amendment to the Fundamental Law of 15 March 2013, which introduced into the Fundamental Law Article U Section (1), which declares that the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party (HSWP) and its predecessors and other political organisations established to serve Communist ideology were criminal organisations and lists the crimes for which their leaders are liable. This in itself can be regarded as a public element of identity politics, since the Fundamental Law is attempting to do historical justice and provide a kind of constitutional interpretation of historical issues. The real problem, however, is that the responsibility for these crimes is also imposed on the legal successor of the HSWP: ‘Political organisations that gained legal recognition during the democratic transition as legal successors of the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party continue to share the responsibility of their predecessors as beneficiaries of their unlawfully accumulated assets.’ Thus, there is a new trend of enemy formation: when the negative identity is embedded of the political enemy in the Fundamental Law, although (in principle) the situation is that ‘[w]hen state authorities consider someone an enemy, it is a classic external or internal war situation or action. Moreover, the state organs of democracy tend to refrain from making a hateful enemy out of their weak, small, and abnormal citizens …’.Footnote 25 From this point of view, one could even argue that from now on a kind of internal public war between the left and the right could break out, but this does not happen because the left has not been able to react in any meaningful way to the intervention of public power in its identity. From then on, the CIE has become a permanent tool of the Orbán regime to supposedly solve acute political disputes.

8.3.3.2 Anti-Immigration: The Refugees as the New Enemies

Hungary was hit by the refugee crisis in 2015 (390,000 people crossed the Serbian–Hungarian or Croatian–Hungarian border that year, of whom 177,000 were registered as asylum seekers). One of the main elements of the anti-refugee and anti-immigration campaign that unfolded from the beginning of the year was the presentation of a constructed enemy image. The government has demoralised the Hungarian society by stepping up the hate campaign. Society was almost ‘prepared’ for the ‘enemy’ to appear: between 1 and 5 September 2015, thousands of refugees queued up at Budapest’s Keleti railway station. From the very beginning, the government not only argued at the political level but also involved and reprogrammed the entire Hungarian state apparatus for the war against refugees and immigrants.

By doing so, the Hungarian government took the next step in the domestic identity politics struggle and included the wave of migration triggered by civil wars and humanitarian disasters. Until 2015, Fidesz understood the left within the wider Hungarian political community, even if it excluded it from the nation. This exclusion can certainly be understood in the sense that the left was excluded from the political nation institutionalised by the Fundamental Law and the voting rights of Hungarians living abroad and should still be included in the nation of the state, which functions as a purely technical category. All this would be logical because Fidesz needs a political enemy or, more precisely, it needs to draw the outline of the enemy over and over again. In his speech at the XXVI Bálványos Summer Free University and Student Camp on 25 July 2015, Viktor Orbán stated that the left is interested in the radical loosening of the national framework and that is why immigration is in its interest, and he attributed this to the ‘reasons’ that emerged during the exclusion from the nation, moreover he argued that the left is suspicious of national identity and it incites against Hungarians abroad. As Orbán argued: ‘The European left, dear friends, sees the problem of immigration not as a source of danger but as an opportunity. The left has always been suspicious of nations and national identity … These people, these politicians, simply do not like Hungarians, and they don’t like them because they are Hungarians.’Footnote 26 Viktor Orbán’s speech at the launch of the ‘Signs of the Times’ discussion paper on 30 October 2015 went even further: he named the left as the force behind migration trends.Footnote 27

The Orbán regime has also elevated its anti-immigration approach to a constitutional level. The Sixth Amendment to the Fundamental Law (14 June 2016), openly linking immigration and terrorism, declared by the votes of Fidesz-KDNP and the radical right Jobbik authorisation of the National Assembly that the initiative of the government was a ‘state of terrorist threat’. This new form of state of exception means that, in the event of a significant and direct threat of a terrorist attack or in the event of a terrorist attack, the National Assembly shall, at the initiative of the government, declare a state of terrorist threat for a fixed period of time and shall simultaneously authorise the government to introduce extraordinary measures laid down in a two-thirds act. During this state of exception, the government may, by means of decrees, introduce measures derogating from the acts concerning the organisation, the operation and the performance of activities of public administration, the Hungarian Defence Forces, the law enforcement organs and the national security services, as well as those laid down in a two-thirds act.

The Orbán government adopted the Seventh Amendment to the Fundamental Law during the discussions with the EU on refugee resettlement quotas. The Jobbik supported the Seventh Amendment (28 June 2018) as well, and it can be seen as a new chapter of the CIE against migration and refugees. The Fundamental Law declares that no ‘foreign population’ shall be settled in Hungary. The protection of the constitutional identity and Christian culture of Hungary shall be an obligation of every organ of the state. By this constitutional revision, the following declaration has been added by the Orbán regime to the constitutional accession clause to the EU: ‘Exercise of competences under this paragraph shall comply with the fundamental rights and freedoms provided for in the Fundamental Law and shall not limit the inalienable right of Hungary to determine its territorial unity, population, form of government and state structure’ (Article E).

Since 2015, a new trend of CIEs has been unfolding: the governing right-wing parties identify the left with a political alien, the refugees (who are consistently called migrants in right-wing communication), not independently of the hate campaign that has been unfolding since 2015, and essentially begins to reposition it as an internal enemy, which, because of its political ‘alienation’, is ultimately a proliferator and servant of foreign interests, that is, the category of ‘hostile internal alien’ is only one step away from external enemies.

8.3.3.3 Anti-Gender: Sexual Discrimination by Constitutional Framework

The third CIE used by the Orbán regime was the constitutionalising anti-gender agenda. In 2018, the Orbán regime cancelled the gender studies degree programme at Eötvös Loránd University,Footnote 28 systematically blocked Hungary’s accession to the Istanbul Convention on action against violence against women and domestic violence and, in doing so, essentially declared a cultural war on Hungarian LGBTQ communities and all gender issues.Footnote 29 There is a demonstrable link between CIE in anti-refugee politics and anti-gender campaigns:

In 2015, Orbán’s government started a new communication campaign in order to strengthen the ‘family-friendly thinking’, to promote pro-family world views and to provide ‘information about the positive results of family politics’. As the refugee crisis deepened, the campaign was postponed, but based on the experience of the anti-refugee campaign over the spring and summer 2015 as well as prior to the government-initiated referendum about refugee quotas in October 2016, we assume that this ‘family-friendly’ campaign could become another territory to mobilize afresh the vision of the enemy.Footnote 30

The Ninth Amendment to the Fundamental Law represents an unprecedented intervention into the lives of LGBTQ communities by effectively declaring any gender issues openly. It states unquestionably that ‘the mother shall be a woman, the father shall be a man’, moreover it declares that ‘Hungary shall protect the right of children to a self-identity corresponding to their sex at birth’.

The Hungarian anti-gender tendencies are embedded into the international framework of politicisation of anti-gender, as Pető and Kovács argue: ‘… these movements are rooted in a broader crisis phenomenon and the scale is much larger than specific local or national government or Church interests’.Footnote 31 At the same time, the Hungarian situation can be considered a tipping point in the international anti-gender discourse, as the Hungarian constitution power (i.e. the Hungarian parliament influenced by the executive power) is trying to make the social and family model being considered desirable rather than mandatory through constitutional means, and the constitution-maker has been able to continuously shape the constitutional directions of anti-gender ideology through constitutional amendments, responding to the tensions accumulating in society. The other main threat of this CIE is the improvement and constitutional legitimisation of the anti-gender movement claimed by Pető and Kovács: ‘In the context of (Central and Eastern) European countries Hungary remains a unique case with a rather long history of anti-gender discourse, but without any palpable anti-gender movement. This, however, can easily change, should the Orbán’s government or the NGOs near the government build up the new enemy “gender”.’Footnote 32

8.4 Conclusions: Constitutional Identity based on CIES

We conclude that Hungarian politics has been defined by Constitutionalised Images of Enemy, the Constitutional Court and the Orbán regime have increasingly invoked the concept of constitutional identity. In its decision 22/2016 (XII. 5.) AB,Footnote 33 the Constitutional Court explained that ‘constitutional identity equals with the constitutional (self-) identity of Hungary’. As Gábor Halmai pointed out: ‘The Court holds that the constitutional (self-)identity of Hungary is a fundamental value that has not been created but only recognized by the Fundamental Law and, therefore, it cannot be renounced by an international treaty. The defence of the constitutional (self-)identity of Hungary is the task of the Constitutional Court as long as Hungary has sovereignty.’Footnote 34

At the heart of Hungarian constitutional identity, the Schmittian friend–enemy dichotomy was integrated in the framework of asymmetrical counter-concepts (anti-Communism, anti-immigration, anti-gender) and the significant social impact of which unleashed considerable anger and hatred. The situation is tragic because on the other side of the asymmetrical counter-concepts there are not Communists, not supporters of illegal immigration and not the sexual abusers of children as propagated by the government, but the political opposition, the people who are about to give humanitarian aid to refugees and the supporters of the LGBTQ communities. Relying on the CIEs, the Orbán regime has thus fundamentally reshaped Hungarian political attitudes after the regime change and, to an unprecedented extent, it has intensified the divisive attitudes that had already divided Hungarian society, which was already prone to a significant degree of isolation.

The transformation of the hate-political space indicated here has had a very serious negative impact on an already fragmented Hungarian society, prone to xenophobia and suffering from numerous social, cultural and health problems. Various sociological surveys and public opinion polls confirm that Hungarian society is one of the most closed societies in Europe, and one of the most intolerant towards foreigners. According to the European Social Survey,Footnote 35 among the EU countries, Hungary and the Czech Republic were the countries where people least thought that migration would make their country a better place. The ESS data were collected in 2002 and 2014, and Hungary was massively and consistently ranked as one of the most vulnerable countries in both cases, before and a decade after EU accession. Moreover, it is notable from the ESS data that, when it comes to migration, it is primarily those people who we perceive as closer to our own culture or civilisational approach that we tolerate more: anyone else who is outside our civilisational preferences we want to keep outside our borders. Perhaps it is not surprising that older and less educated people have a higher proportion of people who reject migration from outside Europe. What is more interesting is that, in a European comparison, the gap between the anti-migration attitudes of the elderly/uneducated and the pro-migration attitudes of the young/educated is the smallest: we are facing a systemic problem, since even young people, for whom Europe as a cultural and economic area is open, have reservations about coming from outside Europe.

All these data are supported by Eurobarometer’s research on EU member states for the period 2014–2018.Footnote 36 In 2014, 39 per cent of Hungarians surveyed said that migration from outside the EU was a rather negative phenomenon, while 28 per cent said it was very negative – both figures are roughly in line with the EU average. By 2018, however, 30 per cent of Hungarians surveyed said that migration from outside the EU was a rather negative phenomenon, while 51 per cent said it was very negative. The divergence from the European trend is striking at EU level, only 18 per cent of respondents were very negative. The timing of the trend reversal clearly confirms the above findings on hate politics: in the May 2015 Eurobarometer,Footnote 37 21 per cent of Hungarian respondents thought migration from outside the EU was very negative, rising to 51 per cent by November 2015. Research published in September 2016 by the Pew Research Center (based on data collected in the Spring 2016 Pew Global Attitude Survey)Footnote 38 confirmed these multi-year, decade-long trends. Hungarians think highly above the European average of refugees as a burden, saying they take away jobs and welfare services, and that their presence poses a higher risk of terrorism. Hungarian respondents also think highly above the European average of Jews, Roma, and above all Muslims.

The Orbán regime uses and mixes constitutionally codified asymmetrical counter-concepts as CIEs in parallel and inter-related ways. Éva Fodor points to very similar phenomena:

Instead, ‘gender’ was most prominently used during these three years to weave a story about migration and Hungary’s struggle against the European Union’s migration quota… In 2018 43.6%, in 2019 41.4% and in 2020 47.1% of all articles which contained the term ‘gender’ also mentioned migrations and migrants. For example, Magyar Nemzet expresses concern about what it sees as ‘the aggressive propaganda about gender and migration’ … threatening the integrity of the Hungarian nation in one of its articles during the Christmas period. In a similar vein, an article two weeks later assures the public that ‘Hungary … resists the integration of masses of migrants and the gender craze’ … emanating from the West.Footnote 39

The Hungarian Fundamental Law and its continuous amendments represent such a discursive strategy which has at its core a racist regime of asymmetrical counter-concepts that form a system of inter-related enemies.