Introduction

Aromatic plants contain volatile compounds that produce characteristic aromas. Essential oils (EOs) extracted from these plants are highly concentrated liquids containing bioactive compounds (Bajalan et al. Reference Bajalan, Rouzbahani, Ghasemi Pirbalouti and Maggi2017). They are widely used in aromatherapy, perfumery, medicine, and more due to their therapeutic properties. Aromatic plants and their EOs are versatile and valuable resources across various industries. Their study and utilization offer natural solutions for health and well-being (Ali-Arab et al. Reference Ali-Arab, Bahadori, Mirza, Badi and Kalate-Jari2022). The Lamiaceae is a large family of aromatic plants, with more than 245 genera and 7886 species worldwide (İhsan Çalış and Hüsnü Can Başer Reference İhsan Çalış and Hüsnü Can Başer2021). In Iran, this family comprises 46 genera and approximately 420 species which marks substantial diversity and a large range of distribution (Jamzad et al. Reference Jamzad, Ingrouille and Simmonds2003). The Lamiaceae family is regarded as one of the most important genetic resources of plants, primarily because of its high ecological flexibility to different climates (Cheminal et al. Reference Cheminal, Kokkoris, Strid and Dimopoulos2020). Lamiaceae species are economically valuable because of their medicinal properties, EOs, and other active constituents (Luo et al. Reference Luo, Du, Zheng, Liang, Huang and Zhang2019; İhsan Çalış and Hüsnü Can Başer Reference İhsan Çalış and Hüsnü Can Başer2021). Within Lamiaceae, the genus Phlomis (comprising over 100 species globally including 17 endemic to Iran) is especially relevant; its members are already exploited in folk medicine as respiratory remedies and wound-healing agents, and they accumulate iridoids, flavonoids, and triterpenes with proven anti-inflammatory and antimutagenic activity (Nieto Reference Nieto2017; Mamadalieva et al. Reference Mamadalieva, Youssef, Ashour, Akramov, Sasmakov, Ramazonov and Azimova2021; Zheleva-Dimitrova et al. Reference Zheleva-Dimitrova, Zengin, Bouyahya, Ahmed, Pereira, Sharifi-Rad and Custodio2024).

Phlomis olivieri, Phlomis persica, Phlomis bruguieri and Phlomis anisodonta are endemic to Iran, with P. olivieri being a widely distributed perennial herb (Mohammadifar et al. Reference Mohammadifar, Delnavazi and Yassa2015). These species have traditionally been used as carminatives and painkillers. The EO of P. olivieri contains various compounds – sesquiterpenes, monoterpenes, flavonoids and others – common to many Phlomis species (Sarkhail et al. Reference Sarkhail, Amin, Surmaghi and Shfiee2005; Delnavazi et al. Reference Delnavazi, Mohammadifar, Rustaie, Aghaahmadi and Yassa2016; Tarhan et al. Reference Tarhan, Urek, Oner and Nakiboglu2022). Major EO components include germacrene D and bicyclogermacrene in P. olivieri (Khalilzadeh et al. Reference Khalilzadeh, Rustaiyan, Masoudi and Tajbakhsh2005); germacrene D, α-pinene and bicyclogermacrene in P. persica; γ-elemene, germacrene D/B and bicyclogermacrene in Phlomis bruguieri (Sarkhail et al. Reference Sarkhail, Amin, Surmaghi and Shfiee2005); and germacrene D and β-caryophyllene in P. anisodonta. Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons, particularly germacrene D, are frequently reported as dominant in these species (Mohammadifar et al. Reference Mohammadifar, Delnavazi and Yassa2015; Mamadalieva et al. Reference Mamadalieva, Youssef, Ashour, Akramov, Sasmakov, Ramazonov and Azimova2021).

Given that plant phytochemicals are often influenced by environmental factors such as geography, climate and soil conditions, understanding chemical variability within and among populations becomes critical (Kalogiouri et al. Reference Kalogiouri, Manousi, Rosenberg, Zachariadis, Paraskevopoulou and Samanidou2021). This is where chemometrics – the application of mathematical and statistical tools to chemical data – proves to be highly valuable. Chemometric analysis enables the detection of patterns, relationships and trends within complex datasets, making it an effective approach for characterizing the phytochemical profiles of plants (Ali-Arab et al. Reference Ali-Arab, Bahadori, Mirza, Badi and Kalate-Jari2022; Salehi Vozhdehnazari et al. Reference Salehi Vozhdehnazari, Hejazi, Sefidkon, Ghanbari Jahromi and Mousavi2022).

To achieve this, advanced analytical techniques such as gas chromatography–mass spectrometry or liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry are typically employed to identify and quantify the chemical constituents present in plant samples. Once quantitative chemical profiles are obtained, unsupervised chemometric methods such as principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) become indispensable tools for data interpretation. PCA reduces data dimensionality, highlights influential compounds, and reveals correlations between variables, while HCA clusters samples based on chemical similarity without requiring prior assumptions. Together, these methods objectively quantify variation resulting from geographical, climatic, or genetic differences and can identify outlier populations that may represent novel chemotypes (Dwivedi et al. Reference Dwivedi, Soni, Mishra, Koley and Kumar2024).

It is hypothesized that P. olivieri populations from different ecogeographical zones of Iran will exhibit distinct EO chemotypes due to environmental and possibly genetic influences. Although P. olivieri is widely distributed across Iran’s diverse climates, there is limited information on how its EO composition varies among populations. Previous studies on Phlomis species have primarily focused on identifying EO constituents from single locations or individual plants, without assessing population-level variability or applying multivariate statistical tools. This study addresses that gap by systematically comparing the EO profiles of multiple P. olivieri populations across varied ecogeographical regions using advanced analytical (GC–MS) and chemometric (PCA, HCA) methods. The novelty of this work lies in its comprehensive approach to identifying intraspecific chemical diversity and potential new chemotypes – something not explored in earlier Phlomis research. These findings could offer valuable insights into the ecological and genetic drivers of phytochemical variation and support the selection of elite chemotypes for pharmaceutical or industrial applications.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

This study investigated the diversity of EO components in Phlomis species over two consecutive years (2023 and 2024). Ten wild populations from different regions of Iran were studied (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Material, Table S1). To ensure freshness and quality, seeds were collected annually from their natural habitats in August 2021 and 2022. The collected plants were first identified in the field by Dr Mehregan, and voucher specimens were deposited in the Herbarium of Azad University (Science and Research Branch, IAUH). In order to accelerate germination and relieve dormancy, the seeds were first stored at 4°C for four weeks. Cold-stratified seeds were sown in October in pots. The following year, uniform 1-year-old plants were selected for evaluation of the EO components and cultivated in a completely randomized design (CRD) with five replicates in a greenhouse with a day/night photoperiod of 16/8 h, a temperature range of 15–25°C and 85% humidity. The EO composition of different populations was examined at the flowering stage. The data of this research are the average of two experiments on Phlomis populations.

Figure 1. The sampling locations of Phlomis olivieri populations from their natural habitats in Iran (Iran National Cartographic Centre).

EO extraction

Aerial parts of the plants were collected for EO extraction. Then were air-dried and ground (300 g each), individually subjected to EO extraction for 3.5 h using hydrodistillation by a Clevenger-type apparatus according to a method recommended in the British Pharmacopoeia (Buchbauer and Baser Reference Buchbauer and Baser2010) (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1). The sample oil, which was light yellow, was then dehydrated over anhydrous sodium sulphate and stored at 4°C until further analysis.

GC and GC–MS analysis

EOs of P. olivieri were analysed using a TRACE MS gas chromatograph (MS-HP-5 column with 30 m × 0.25 mm and 0.25 µm film thickness) coupled with a mass detector (HP-6973). The flow rate of carrier gas (Helium) was 1.1 mL min−1. The oven temperature was initiated at 60°C and was then gradually raised at a rate of 5°C per min to 250°C. The injection temperature was 250°C and the EO sample (1 µL) was injected with a split ratio of 1:50. The MS spectra were acquired by electron ionization at 70 eV and a scan mass range of 20–500 amu. The Kovats retention indices (KI) of the compounds were calculated using a homologous series of n-alkanes injected in conditions equal to the samples. Identification of the constituents was based on software that matched the Wiley 7 nL online library. This was also by direct comparison of the retention indices and MS fragmentation patterns with those reported for standard compounds (Adams Reference Adams2007). The EO was also analysed using a TRACE MS gas chromatograph equipped with a FID detector to get relative percentages of the identified compounds. The FID detector temperature was 250°C and the operation was conducted under the same conditions as described for GC-MS analysis. The extraction of EO and its analysis were carried out in Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran.

Identification of components

The components of the oils were identified by their retention time, retention indices relative to C9-C24 n-alkanes, and by comparison of their mass spectra with those of authentic samples or with data already available in the literature. The relative percentage of compounds was calculated from the total chromatogram (Salehi Vozhdehnazari et al. Reference Salehi Vozhdehnazari, Hejazi, Sefidkon, Ghanbari Jahromi and Mousavi2022).

Statistical analysis

The experiment was carried out in a completely randomized design (CRD) with five replicates. For each species, EOs were extracted from five individual plants (biological replicates, n = 5). Each extract was analysed by GC–MS in triplicate, yielding three technical replicates per biological sample. Significant differences between mean values were determined by Duncan’s multiple range tests at a significance level of 0.01, using SPSS program (version 21). Principle component analysis (PCA) was used to evaluate the chemical variability among the P. olivieri EO using the statistical analysis software Minitab version 16. Also, Cluster analysis was performed on the main essential components using Minitab ver. 16 based on the Ward variance method. The Mantel test was used for studying the association between phytochemical traits and geographical distances, molecular and phytochemical, of the studied populations. This analysis was facilitated by the Gen Alex software ver. 6.2. A summary of the experimental design used for evaluation is presented in Supplementary Material, Table S2.

Results

EO composition

The hydrodistillation of P. olivieri Benth. specimens produced light yellowish oils, with GC–MS analysis identifying 20 components representing 85.70% to 99.92% of the total oil profile (Table 1). Significant differences in chemical components were observed among populations, from different geographic origin. The main constituents were sesquiterpenes (65%), followed by monoterpenes (15%) and other compounds (20%).

Table 1. Essential oil profile of Phlomis olivieri populations originated from different habitats in Iran

a Retention index relative to C9-C24 n-alkanes on a HP-5 column.

In this study, despite the abundance and diversity of compounds present in the studied populations, certain compounds were absent in specific populations. α-Thujene was not detected in populations 8 (Afus) and 10 (Kesheh). Additionally, caryophyllene oxide was absent in population 7 (Damavand), while isospathulenol was not found in populations 2 (Taleghan) and 9 (Hamedan).

Furthermore, (2E)-2-dodecen-1-ol and undecanal were identified in the EOs of P. olivieri populations. Population 9 (Hamedan) exhibited a notably high level of (E)-caryophyllene. The results also showed that the EOs from the Afus and Ganjnameh populations are rich in sesquiterpenes and have a high potential for extracting these compounds. The biosynthetic pathways of EOs in P. olivieri populations exhibited significant variability. The Mantel test showed no significant correlation between phytochemical composition and genetic distances (R 2 = 0.404, P = 0.080).

Hierarchical cluster analysis

The HCA classified the 10 populations into two main clusters (A and B), each further divided into two sub-clusters. Sub-cluster A1 included populations 4, 6 and 7, characterized by high levels of germacrene B and caryophyllene oxide. Sub-cluster A2, comprising populations 3, 8 and 10, was distinguished by the highest mean values of germacrene D, spathulenol and δ-cadinene. Notably, populations 8 and 10 originated from the Isfahan region. Population 9 formed a distinct sub-cluster (B1) with the highest (E)-caryophyllene content, while sub-cluster B2 (populations 1, 2 and 5) exhibited the highest levels of bicyclogermacrene and α-pinene (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Average-linkage dendrogram of the 10 Phlomis olivieri populations (pop1–10) resulting from the cluster analysis (based on Euclidean distance) of the oil components. Pop1: Kandovan; pop 2: Taleghan; pop 3: Kojoor; pop 4: Firozkooh; pop 5: Alamot; pop 6: Abali; pop 7: Damavand; pop 8: Afus; pop 9: Ganjnameh; pop 10: Kesheh.

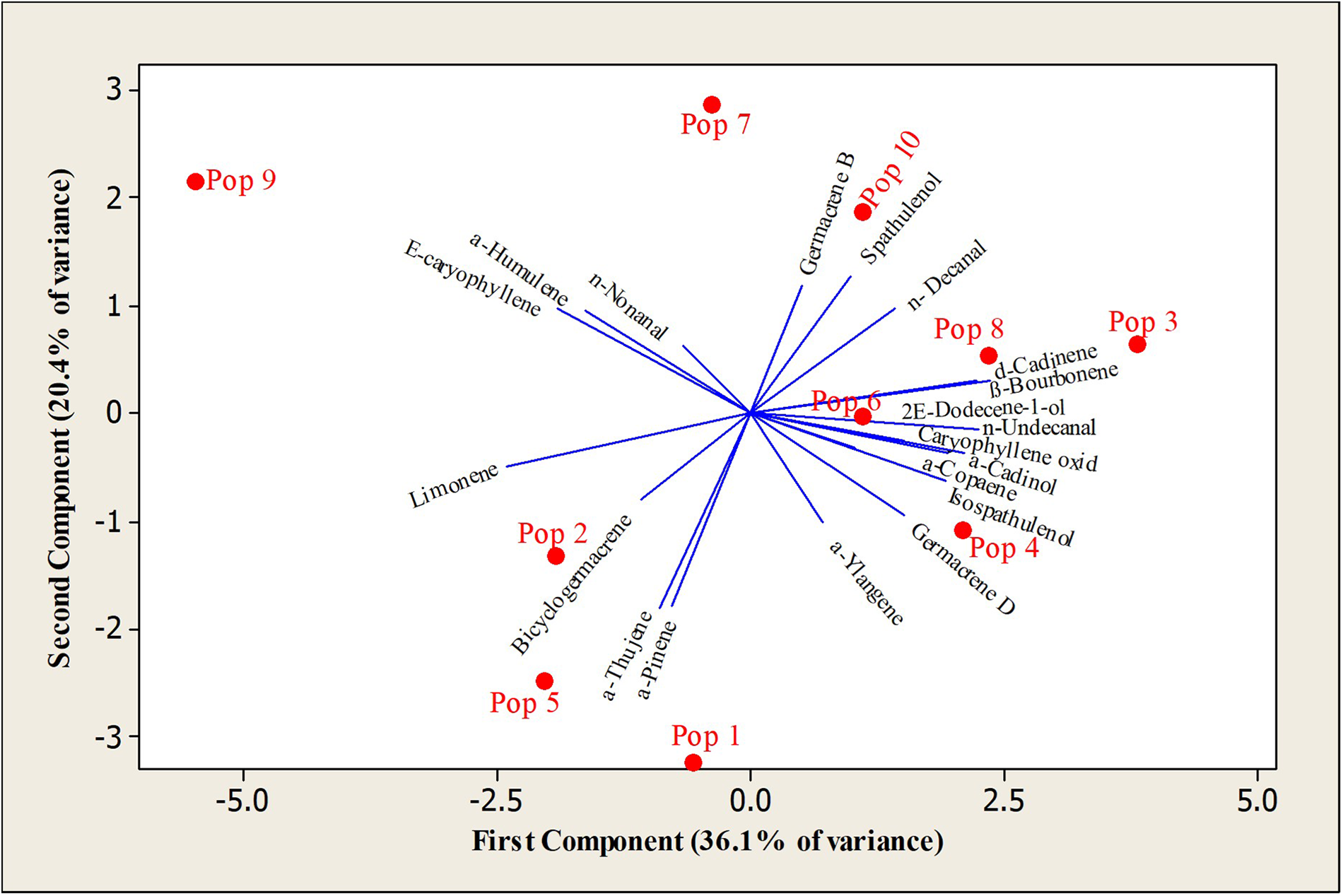

Principal component analysis

PCA further confirmed the diversity of volatile oil composition and phytochemical similarities among populations. The first two principal components accounted for 56.5% of the total variance (PC-1: 36.1%, PC-2: 20.4%), with the third component explaining an additional 14%. The PCA bi-plot revealed that most EO compounds correlated directly with the distribution pattern of the studied populations. Population 9 was distinctly separated due to its high (E)-caryophyllene content. The PCA findings aligned with the results of cluster analysis, showing that geographically similar populations grouped together based on their phytochemical composition (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Biplot of chemical compositions of Phlomis olivieri oils. Distribution of variables and distribution of samples. Pop1: Kandovan; pop 2: Taleghan; pop 3: Kojoor; pop 4: Firozkooh; pop 5: Alamot; pop 6: Abali; pop 7: Damavand; pop 8: Afus; pop 9: Ganjnameh; pop 10: Kesheh.

Discussion

The hydrodistillation of P. olivieri Benth. specimens yielded light yellowish oils, with sesquiterpenes, monoterpenes and other compounds as the main constituents. Previous studies have shown variation in EO compositions based on geographic origin, with sesquiterpenes being the predominant constituents (Göger et al. Reference Göger, Türkyolu, Nur Gürşen, Yur, Karaduman, Göger, Tekin and Özek2021; Ghavam Reference Ghavam2023). In this study, the sesquiterpene content was specifically comprised of (E)-caryophyllene and germacrene D as predominant compounds. Other major compounds included spathulenol, bicyclogermacren, α-pinene, caryophyllene oxide and germacrene B. Compounds present in smaller amounts included δ-cadinene, β-bourbonene, n-nonanal and α-humulene. A literature survey revealed the presence of germacrene D, β-caryophyllene and α-pinene in the EOs of P. olivieri aerial parts from various regions, including Chalus (Mazandaran) (Sarkhail et al. Reference Sarkhail, Amin, Surmaghi and Shfiee2005), Damavand (Tehran) (Mirza and Bahar Nik Reference Mirza and Bahar Nik2003) and Taleghan (Alborz) (Khalilzadeh et al. Reference Khalilzadeh, Rustaiyan, Masoudi and Tajbakhsh2005). Studies by Bajalan et al. (Reference Bajalan, Rouzbahani, Ghasemi Pirbalouti and Maggi2017), Ghavam (Reference Ghavam2023) and Kirimer et al. (Reference Kirimer, Başer and Kürkcüoglu2006) also identified germacrene D as the dominant EO component of P. olivieri, which is consistent with the findings of the present study. Although the same major compounds were found across different regions, their quantities varied. These differences in EO composition can reflect distinct chemotypes within Phlomis populations. Such variations are likely influenced by environmental conditions, genetic factors and ecological interactions (Ghanbari et al. Reference Ghanbari, Salehi and Jowkar2023; Montahae et al. Reference Montahae, Rezaei, Ghanbari, Kalateh and Khiavi2023).

The study found that α-thujene, caryophyllene oxide, isospathulenol and undecanal compounds were present in P. olivieri populations, but not in populations 8 and 10. Population 9 had an unprecedented value of (E)-caryophyllene, despite the rich compounds present. In previous studies, a lower amount of β-caryophyllene was reported (Mohammadifar et al. Reference Mohammadifar, Delnavazi and Yassa2015). Also, (E)-9-epi-caryophyllene (7.7%) was found in this species (Khalilzadeh et al. Reference Khalilzadeh, Rustaiyan, Masoudi and Tajbakhsh2005; Ghorbani et al. Reference Ghorbani, Golkar, Jafari, Ahmadi and Allafchian2023). According to the data obtained in this study, it is plausible to suggest that there are multiple chemotypes present within this plant species. To fully capture the phytochemical diversity, future research should expand sampling to include more specimens across broader geographical ranges. Our findings highlight the Afus and Ganjnameh populations as particularly valuable sources, demonstrating both exceptional sesquiterpene richness and strong potential for targeted compound extraction. Researchers reported that genetic and environmental factors can affect the yield, type and amount of active ingredients in plants (Farhadi et al. Reference Farhadi, Babaei, Farsaraei, Moghaddam and Ghasemi Pirbalouti2020; Montahae et al. Reference Montahae, Rezaei, Ghanbari, Kalateh and Khiavi2023). Our data on the effects of genetics on modifying EO compounds is supported by reports of changes in germacrene D and (E)-caryophyllene in other plant species under genetic and environmental variations (Bakhtiar et al. Reference Bakhtiar, Khaghani, Ghasemi Pirbalouti, Gomarian and Chavoshi2021; Carvalho et al. Reference Carvalho, Oda, Sacramento, Pereira, Crevelin, Crotti and Santos2023).

The biosynthetic routes that plants use to produce EOs can be greatly impacted by genetic and environmental variability. Variations in these factors have the potential to impact the metabolic processes, enzyme activity, and gene expression linked to the synthesis of EOs (Aqeel et al. Reference Aqeel, Aftab, Khan and Naeem2023). Variability in genetics can also have an impact on the density and size of EO glands on plant leaves (Montahae et al. Reference Montahae, Rezaei, Ghanbari, Kalateh and Khiavi2023). The absence of certain compounds like α-thujene or caryophyllene oxide in certain populations may indicate ecological and environmental differences. These compounds are involved in plant defense, stress tolerance and interactions with herbivores and pollinators (Maccioni et al. Reference Maccioni, Macis, Gibernau and Farris2023). Their absence may be due to reduced selective pressure, genetic divergence, local adaptation, or environmental constraints. Additionally, certain terpenes may be suppressed under specific ecological conditions, leading to their absence in the final EO profile (Salehi Vozhdehnazari et al. Reference Salehi Vozhdehnazari, Hejazi, Sefidkon, Ghanbari Jahromi and Mousavi2022; Maccioni et al. Reference Maccioni, Macis, Gibernau and Farris2023).

The Mantel test showed no significant correlation between phytochemical composition and genetic distances in P. olivieri populations. Cluster analysis was performed to explore EO variation, revealing distinct chemical profiles among populations. The biosynthesis of EO compounds is influenced by factors like climate, soil properties, altitude and biotic stresses (Ali-Arab et al. Reference Ali-Arab, Bahadori, Mirza, Badi and Kalate-Jari2022). PCA confirmed the diversity of volatile oil composition and assessed phytochemical similarities among P. olivieri populations. Results showed that 56.5% of the total variation in EO composition was effectively explained by the first three principal components, with PC-1 and PC-2 accounting for 36.1% and 20.4% of the variance, respectively. Populations with similar phytochemical compositions tended to cluster together, suggesting a possible link between EO composition and geographic origin. The PCA findings highlight the potential influence of environmental factors on EO composition, reinforcing the idea that geographically close populations tend to share similar phytochemical profiles (Mollaei et al. Reference Mollaei, Ebadi, Hazrati, Habibi, Gholami and Sourestani2020; Salehi Vozhdehnazari et al. Reference Salehi Vozhdehnazari, Hejazi, Sefidkon, Ghanbari Jahromi and Mousavi2022). Our data refute the presumed single germacrene-D chemotype of P. olivieri by revealing at least three stable chemotypes whose compound absences (e.g., caryophyllene oxide) imply site-specific herbivore pressures rather than simple climatic gradients (Salehi Vozhdehnazari et al. Reference Salehi Vozhdehnazari, Hejazi, Sefidkon, Ghanbari Jahromi and Mousavi2022).

Identifying compounds such as isospathulenol, (2E)-2-dodecen-1-ol and undecanal in P. olivieri for the first time expands its known chemical profile. Additionally, the substantial presence of (E)-caryophyllene and germacrene D in specific populations highlights the significant chemical diversity among these populations. These findings emphasize the complexity of EO composition in P. olivieri and suggest potential chemotypic variations influenced by genetic and geographical origin factors. P. olivieri should be used for commercial or medicinal exploitation based on newly recognized chemotypes, such as Afus and Ganjnameh populations for bulk oil production, Population 9 for anti-inflammatory formulations and sub-cluster A1 and A2 for targeted therapeutic applications. Elite chemotypes should be propagated and cultivated under native habitat conditions, while populations lacking key defense-related terpenes require pest management or avoid large-scale monoculture. Environmental factors outweigh neutral genetic distance in shaping oil composition. This study is the first to map chemotype diversity in P. olivieri, revealing three distinct chemotypes and identifying several previously unreported compounds. It challenges the long-held view of a single germacrene-D profile and highlights new elite populations for targeted applications.

Conclusions

The results of this study confirm that sesquiterpenes – particularly germacrene D and (E)-caryophyllene – are the predominant chemical constituents in P. olivieri populations. Notably, substantial variation in EO profiles was observed among populations, indicating the presence of distinct chemotypes. This intraspecific chemical diversity has both commercial and conservation significance. Populations with desirable EO profiles, such as those from Afus and Ganjnameh (rich in germacrene D and (E)-caryophyllene, respectively), represent valuable genetic resources for targeted breeding, cross-pollination and domestication efforts. Cultivating such populations can enhance the sustainable production of specific bioactive compounds for industrial or medicinal applications. Moreover, domestication and propagation of these chemotypes serve as a strategy for ex situ conservation, helping to preserve genetic and phytochemical diversity in the face of habitat degradation and environmental threats. Based on our findings, we recommend future research to focus on breeding trials, agronomic evaluations, and propagation studies to assess the stability of EO profiles under cultivation and to support the development of chemotype-specific cultivation programs.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at 10.1017/S1479262125100257

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Dr Hooshmand Safari (Research Department of Forests and Rangelands, Kermanshah), for his kind assistance and advice on data analyses. We are also grateful to Dr Syavash Mohamadi and Dr Esmaeil Khosravi, for supporting this project.

Funding statement

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Competing interests

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.