Social enterprises (SEs) are organizations engaging in business to address social issues and fulfill social missions (Mair & Marti, Reference Mair and Marti2006). They may take hybrid forms due to the coexistence of business models and social goals (Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Haugh and Lyon2014). Social entrepreneurship refers to the process of identifying and solving social problems through the application of entrepreneurial principles, strategies, and techniques, and it has been on the rise as a model to solve social issues (Austin et al., Reference Austin, Stevenson and Wei-Skillern2012). While related, these two terms describe distinct phenomena—social enterprises represent the organizational form, while social entrepreneurship captures the underlying process. This paper examines both SEs as organizational entities and social entrepreneurship activities they undertake. As organizations, SEs contribute to local communities (Kerlin et al., Reference Kerlin, Littlepage and Tirmizi2021) and fulfill unmet public goods demands (Chandra & Paras, Reference Chandra and Paras2020). However, SEs are still viewed as somewhat idealistic due to hybrid organizing logics and institutional challenges (Pache & Santos, Reference Pache and Santos2012).

The SE ecosystem includes actors at individual, organizational, and community levels, influencing their innovation and scaling (Roundy, Reference Roundy2017). Some scholars view social entrepreneurship as a collective, participatory organizing process where SEs form partnerships with diverse organizations to engage with stakeholders, engage in collective sensemaking, and structure their governance (Mitzinneck & Besharov, Reference Mitzinneck and Besharov2019). Legitimacy in local communities is key to SE success. However, the blend of social and business goals poses challenges to organizational identity, causing public scrutiny. SEs also face complex stakeholder expectations, leading to conflicting priorities and performance evaluation difficulties. Studies show organizational realities result in ongoing tensions related to SE identity (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Erickson, Potts, Watling and Vázquez2020). SEs’ response strategies to institutional complexity often lead to hybrid forms and mission drift (Litrico & Besharov, Reference Litrico and Besharov2019).

Prior research has primarily focused on the general challenges of hybrid organizing in SEs but has not closely examined how the specific organizational form (nonprofit vs. for-profit) may shape the institutional tensions faced by SEs and the coping strategies they employ. Limited research on coping strategies has mainly advocated for internal best practices without considering engagement with other players in the broader ecosystem (Savarese et al., Reference Savarese, Busch and Steenkamp2021). This study examines how different SE models encounter and manage institutional complexities through the lens of cross-sector collaboration. Exploring how institutional tensions vary based on legal structure and governance is crucial, as the hybrid nature of these organizations can pose unique challenges that require tailored strategies and support systems. Additionally, examining the partnership approaches SEs use to navigate institutional complexities is important, given the relational nature of social entrepreneurship and the need to bridge diverse stakeholder expectations (Montgomery et al., Reference Montgomery, Dacin and Dacin2012). Unpacking how SEs collaborate across sectors can offer guidance on effective approaches to balance competing demands and sustain dual mission.

With qualitative data collected from 15 SEs located in a Southeastern State in the USA, this study demonstrates the importance of cross-sector partnerships in obtaining legitimacy of SEs. A typology of partnerships (community engagement, resource acquisition, and dual-value) was introduced to describe what strategies SEs of different organizational forms can employ to manage institutional tensions. By identifying specific institutional tensions faced by SEs based on their legal structure, as well as the partnership strategies employed navigate these complexities, this study contributes to the growing literature on hybrid organizing and management and institutional complexity in the context of SEs. It also offers practical guidance for SE practitioners on effective collaborative approaches to balance competing social and commercial demands.

Tensions Within SEs Through an Institutional Perspective

SEs leverage commercial activity for social purposes, often focusing on local needs (Mair & Rathert, Reference Mair and Rathert2021). This current study focuses on SEs that take on an organizational form, i.e., the “archetypal configuration of structures and practices” appropriate within an institutional context (Greenwood & Suddaby, Reference Greenwood and Suddaby2006 p. 30). SEs could take on the forms of nonprofits, businesses, B-corporations, or hybridization (Battilana & Lee, Reference Battilana and Lee2014). Organizational forms demonstrate essential differences in funding models, organizational structure, and performance metrics (Berry, Reference Berry2017). Business SEs often have access to a wider range of funding options, while nonprofit SEs may rely more heavily on grants and donations. They also have different governance structures (e.g., influence of shareholders/investors vs. board of directors). Business SEs may place a stronger emphasis on financial metrics, while nonprofit SEs may focus more on social and environmental impact indicators. To summarize, SEs with different organizational forms may face unique challenges related to scaling operations or balancing dual goals.

By definition, SEs face institutional logics which refer to symbolic constructions and material practices that constitute the organizing principles of society (Friedland & Alford., Reference Friedland, Alford, Powell and DiMaggio1991). Institutional logics guide the behavior of actors within an organizational field by providing context-specific practices and symbols regarding what is accepted and legitimate. When facing uncertainties or ambiguity, institutional logics offer organizational actors rules of actions. Organizations routinely adhere to multiple institutional logics, but institutional complexity only rises when confronting a newly salient logic which results in either organizational settlement (i.e., organizations durably incorporating multiple logics) or organizational hybridization (i.e., a change process whereby organizations abandon existing organizational settlement and transition to a new one) (Schildt & Perkman, Reference Schildt and Perkmann2017).

To address how SEs respond to institutional complexity, this study draws from a growing area of the SE literature that unpacks the nature and management of tensions derived from complex and even conflicting institutional logics. Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Gonin and Besharov2013) summarize these tensions into (a) performing tensions that emerge from divergent outcomes, metrics, and stakeholder demands associated with success or performance (e.g., financial sustainability or social impact), (b) organizing tensions that emerge from divergent internal dynamics and day-to-day operations (e.g., challenges related to organizational structure, legal form, cultures, practices, and processes), (c) belonging tensions which emerge from divergent identities among subgroups and between subgroups and the organization (e.g., how to present the organization to diverse stakeholder groups who may have conflicting expectations and perceptions about its true purpose and commitment), and (d) learning tensions that capture tensions of growth, scale, and change from divergent horizons (e.g., how to balance short-term goals focused on financial sustainability and immediate social impact with longer-term objectives around scaling, growth, and achieving more transformative social change). They further argue that these tensions influence how SEs manage divergent stakeholder expectations, operate businesses, define legal designations, and attend to short-term and long-term goals.

Tensions should not only be viewed as conflicts; they could also function as opportunities for innovation, creativity, and change if managed effectively. Organizations can engage in assimilation (i.e., adopting practices from a different institutional logic), blending (i.e., incorporating elements of existing logics into a new and blended one), or compartmentalization (i.e., separating the activities which respond to different logics) to overcome these tensions derived from incompatibility (Skelcher & Smith, Reference Skelcher and Smith2015). Another effective solution is to ensure diverse stakeholders are consulted on and included in decision-making processes (Crucke & Knockaert, Reference Crucke and Knockaert2016). However, existing strategies for SEs to handle tensions have mainly been examined through an internal and organizational perspective, e.g., utilizing human resource management practices (Battilana & Dorado, Reference Battilana and Dorado2010), organizational design (Binder, Reference Binder2007), or social accounting (Ramus & Vaccaro, Reference Ramus and Vaccaro2017). There is a gap at the meso and interorganizational level to investigate how SEs interact with other organizations in their ecological system to manage these tensions (Savarese et al., Reference Savarese, Busch and Steenkamp2021).

Institutional theory examines the relationship between organizations and their ecological environment (AbouAssi et al., Reference AbouAssi, Makhlouf and Whalen2020). To have a comprehensive understanding of SEs’ management of institutional tensions, it is important to investigate strategies beyond the internal and organizational level. For example, when managing performing tensions, SEs often need to balance divergent outcomes. Studying partnerships could reveal how they manage trade-offs and tensions between competing demands. In managing organizing tensions, partnerships can provide insights on how they organize and coordinate resources and activities. For belonging tensions, partnerships could shed light on how the SEs navigate relationships with stakeholders to foster a sense of belonging. Lastly, to manage learning tensions, partnerships could function as a critical source of knowledge and resources.

However, partnerships should not be conceptualized as a panacea for institutional tensions. New tensions may emerge. Hence, SEs are often strategic about whom they form alliances with. Savarese et al. (Reference Savarese, Busch and Steenkamp2021) proposed that the influences of interorganizational partnerships on hybrid organizations such as SEs are contingent upon the types of relationships (e.g., being philanthropic, transactional, or integrative) and the types of partners (e.g., whether they have aligned or alternative logic with the focal organization). Partnership programming also matters when managing institutional tensions to ensure the achievement of organizational missions when multiple identities may create crashes (Ramus & Vaccaro, Reference Ramus and Vaccaro2017).

SE’s Interorganizational Collaboration in Response to Institutional Complexity

Existing literature has focused on the general notion that SEs have complex institutional logics and thus take on a variety of forms which range from nonprofits, for-profits, cooperatives, to hybrid structures that blend elements of both nonprofits and for-profit models. However, it often does not differentiate how SEs of various dominant forms may encounter different tensions. Understanding these tensions could offer insights regarding how to maximize social and economic impacts.

SEs can adopt a particular organizational form based on stakeholder expectations, resource acquisition needs, and governance requirements (Fitzgerald & Shepherd, Reference Fitzgerald and Shepherd2018). To be categorized as a distinct organizational form, organizations need to manifest structural characteristics (e.g., hierarchy, division of labor, formal policies and procedures), practices and routines (e.g., day-to-day operations, decision-making process), and external legitimacy (Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Haugh and Lyon2014; Skelcher & Smith, Reference Skelcher and Smith2015). SEs may also choose a hybrid form. Nevertheless, a dominant organizational form can accentuate the conflicts between conflicting institutional logics. Nonprofit SEs may face challenges in balancing their social mission with the need to generate sufficient revenue. They may encounter pressure to compromise social goals to secure funding or remain financially viable. When SEs adopt a for-profit form, tensions may rise from shareholders’ expectations where economic growth is viewed as the priority.

The literature has yet to investigate how SEs of various organizational forms may experience different types of institutional tensions. Therefore, this study first examines the following research question:

RQ1

How do the institutional tensions experienced by SEs vary based on their organizational form (e.g., nonprofit vs. for-profit)?

Situated at institutional crossroads and pluralist logics, SEs need to develop strategies to attend to competing institutional demands based on resources at hand and whether tensions between these demands involve goals or means (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Gonin and Besharov2013). The key to addressing these tensions lies in obtaining legitimacy. Existing literature on institutional theory and hybrid organizing has emphasized the importance of legitimacy building for SE survival and success (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Cai and Song2023; Yang & Wu, Reference Yang and Wu2016). Scholars have argued for a legitimacy-based SE model which centers on proposition (i.e., what types of legitimacy to build), strategy planning, and strategy implementation (Yang & Wu, Reference Yang and Wu2016).

Three types of legitimacy have been distinguished: pragmatic, moral, and cognitive (Suchman, 1995). Pragmatic legitimacy refers to an organization’s compliance with the expectations of its key stakeholders and regulatory authorities. Moral legitimacy relates to an organization’s adherence to societal norms, values, and beliefs about what is appropriate and desirable. Cognitive legitimacy involves an organization being viewed as comprehensible, taken-for-granted, and meaningful within its institutional context (Zimmerman & Zeitz, Reference Zimmerman and Zeitz2002).

SEs operate at the intersection of multiple institutional logics, and thus, different dimensions of legitimacy are crucial for resource acquisition, complying stakeholder demands, and overcoming institutional challenges (Spanuth & Urbano, Reference Spanuth and Urbano2024). Pragmatic legitimacy is salient for SEs as they must comply with regulations and secure stakeholder support to access necessary resources (Bradford et al., Reference Bradford, Luke and Furneaux2020). Moral legitimacy is particularly important as SEs are driven by social missions and must demonstrate commitment to societal norms and values, which helps garner community and stakeholder support and trust (Dart, Reference Dart2004). Finally, cognitive legitimacy is key as achieving comprehensibility and meaningfulness within an institutional environment can facilitate resource mobilization, stakeholder engagement, and scaling of social impact (Yang & Wu, Reference Yang and Wu2016).

SEs’ partnerships can be viewed as legitimacy-building strategies that address the tensions between social and commercial logics (Battilana & Lee, Reference Battilana and Lee2014; Huybrechts & Nicholls, Reference Huybrechts and Nicholls2013). This current study examines how SEs of different organizational forms strategically leverage interorganizational collaboration with partner organizations to address tensions derived from complex institutional logics. In understanding collaboration among organizations, it is important to distinguish between interorganizational collaboration and cross-sector collaboration. Interorganizational collaboration refers to collaboration between organizations, regardless of sectors, such as partnerships between businesses or between nonprofits (Heath & Isbell, Reference Heath and Isbell2017). Cross-sector collaboration specifically refers to collaboration between organizations from different sectors, such as government–business, business–nonprofit, or government–nonprofit partnerships (Bryson et al., Reference Bryson, Crosby and Stone2015). Cross-sector collaboration is particularly relevant for SEs that often need to engage with and bridge the expectations of stakeholders from different sectors to effectively manage the institutional tensions and achieve dual social and economic objectives (Weber et al., Reference Weber, Haugh, Göbel and Leonardy2022).

Despite extensive literature on network activities of SEs, their partnerships are still sporadic and remain at an early stage (Bacq & Eddleston, Reference Bacq and Eddleston2018). Nevertheless, a variety of SE partnership activities have been described in detail, such as resource acquisition or mobilization, joint delivery of services and goods, and policy or advocacy work (Mitzinneck & Besharov, Reference Mitzinneck and Besharov2019). These network types afford SEs different opportunities to pool resources, share knowledge, access diverse stakeholders, and enhance legitimacy. However, there is a lack of a coherent typology regarding how SEs leverage partnerships to address institutional tensions as hybrid organizations bridging multiple logics and to generate value (Weber et al., Reference Weber, Haugh, Göbel and Leonardy2022).

Cross-sector partnerships may vary by the level of integration between sectors (Wang & O’Connor, Reference Wang and O’Connor2022). Less integrated partnerships may include sponsorship, cause marketing, or employee volunteering, while more integrated partnerships involve complex strategic collaborations that incorporate partners’ mission, people, and activities to co-create values for society (Austin, Reference Austin2010). For SEs, forming cross-sector partnerships requires a clear identity of who they are, and whether the alliance focuses on value capture or value creation (Osterag et al., Reference Ostertag, Hahn and Ince2021; Santos, Reference Santos2012). Measured at the organizational level, value capture happens when SEs appropriate a proportion of the value created (Santos, Reference Santos2012). Focusing on the broader society or community level, value creation refers to a participative process where organizations together generate and develop shared objectives, resources, and measuring societal impact (Ind & Coates, 2013). SEs’ cross-sector partnerships can be implemented to contribute to not only the achievement of business goals (value capture) but also social mission (value creation) (Ostertag et al., Reference Ostertag, Hahn and Ince2021). However, SEs are expected to focus on value creation, rather than just value capture (Santos, Reference Santos2012). We examine the following research question:

RQ2

What strategies do SEs of different organizational forms employ, particularly through cross-sector partnerships, to manage the institutional tensions they face?

Method

Data Collection

After securing IRB approval, in-depth interviews were conducted with 15 social enterprises located in a southeastern state in the USA. A roster was developed based on Social Enterprise Alliance directory and B-Lab directory of all-certified b-corps. The sampled organizations ranged in age, with the oldest founded in 1976 and the newest in 2019 (M = 21.80, S.D. = 19.97). Interview questions included motivations for operating as SEs, partnership activities, data practices, and main challenges. The sampled organizations were based in five counties with various scope of work (9 local, 4 regional, and 2 more than regional). They covered seven main issue areas: Arts, Culture, and Humanities (n = 1), Community Improvement & Capacity Building (n = 1), Education (n = 2), Employment (n = 2), Housing and Shelter (n = 1), Human Services (n = 2), and Food, Agriculture, & Nutrition (n = 6). Interviews were conducted with employees who held a leadership role in an organization (e.g., founder, co-founder, executive director, president, or director of external relationships or Business Support Program). Thirteen of the interviewees identified as white, 1 as African American, and 1 as Asian. In addition, five identified as female and 10 as male. The interviews lasted 30 min to an hour either on zoom (n = 12) or in-person (n = 3) between September 2019 and May 2020.

Sampling was guided by the institutional framework, which describes that institutional patterns are best observed in samples of multiple organizations. Collecting a geographically bounded sample ensured the organizations were embedded in the same institutional environment. This sampling approach captured the notion of an organizational field, referring to a collection of organizations providing similar services and sharing similar approaches to gaining legitimacy (AbouAssi et al., Reference AbouAssi, Makhlouf and Whalen2020).

Coding Procedure

The interview transcripts were analyzed through two rounds of coding. The first step involved attribute coding of organizational characteristics such as age, social issues, and legal registration status. Second, the author developed a codebook with provisional codes based on the literature to identify partnership types and institutional tensions (Saldaña, Reference Saldaña2013). The author then used this codebook as a guide, revising and modifying it as additional codes and themes emerged through the process of focused coding (Saldaña, Reference Saldaña2013).

The following variables were coded in the analysis. Organizational form captures what legal form a SE adopted. Partnership type was identified through deductive coding: identifying and recruiting stakeholders and clients, community engagement, getting funding, creating name recognition, implementing programs, hosting events, and other unspecified activities. Institutional tension was coded as four categorical variables (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Gonin and Besharov2013). Organizations facing performing tensions emphasize challenges in measuring success and performance metrics. Performing tensions could make it difficult for organizations to define and measure success across dual objectives, which can sometimes lead to prioritizing one set of goals over the other. Organizations facing organizing tensions emphasize challenges in obtaining human resources and retaining employees and clients. Organizing tensions arise from conflicting demands, cultures, and practices required to pursue social missions versus business ventures and could be reflected in hiring, training and managing employees of different skill sets and backgrounds, or decisions related to organizational structures and legal forms. Organizations facing belonging tensions encounter challenges such as managing multiple or hybrid identities, managing different expectations from diverse stakeholders, and presenting a consistent identity to employees and external audiences. Last, organizations facing learning tensions mention challenges in scaling up business operation, managing the conflict between increased business and lower social impact, and balancing short-term and long-term goals. These tensions surface in decisions around resource allocation, geographic explanation, and the ability to sustain participatory organizational models as the organization grows.

Results

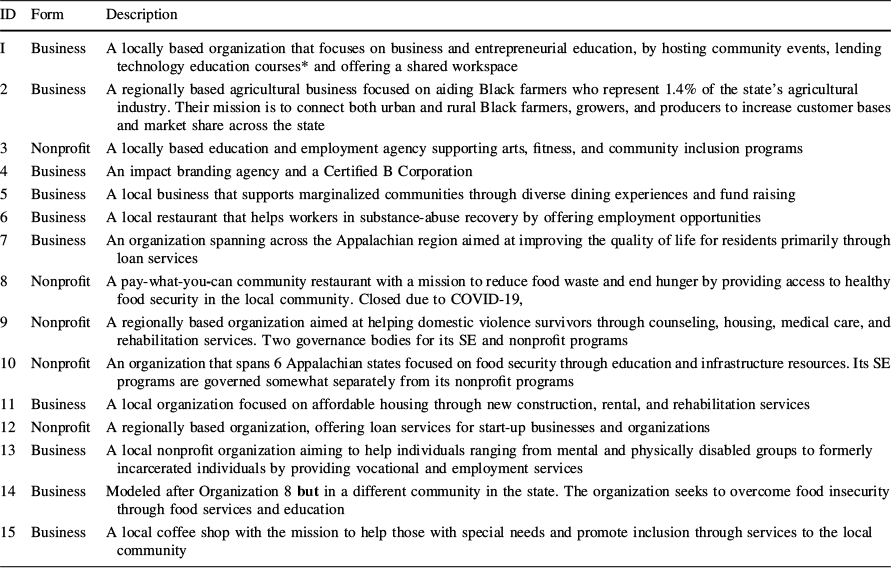

The SEs interviewed were diverse in scope of work and issue areas (Table 1). Among the 9 business entities, these organizations ranged from marketing agencies, restaurants, to loan providers for socially disadvantaged groups. One business was a certified B-corporation. All the other 6 organizations identified as nonprofits. The findings presented below reveal distinct patterns in the types of institutional tensions experienced and the cross-sector partnership strategies employed by organizations with different legal forms. By unpacking these nuanced differences, this study offers important insights into how organizational structure of SEs shapes their management and competing institutional logics and priorities. The subsequent sections will delve into the key differences identified between nonprofit and for-profit SEs regarding the specific tensions they face, and the partnership approaches they leverage to navigate these tensions and sustain their dual mission.

Table 1 List of the sampled SEs for interviews

|

ID |

Form |

Description |

|---|---|---|

|

I |

Business |

A locally based organization that focuses on business and entrepreneurial education, by hosting community events, lending technology education courses* and offering a shared workspace |

|

2 |

Business |

A regionally based agricultural business focused on aiding Black farmers who represent 1.4% of the state’s agricultural industry. Their mission is to connect both urban and rural Black farmers, growers, and producers to increase customer bases and market share across the state |

|

3 |

Nonprofit |

A locally based education and employment agency supporting arts, fitness, and community inclusion programs |

|

4 |

Business |

An impact branding agency and a Certified B Corporation |

|

5 |

Business |

A local business that supports marginalized communities through diverse dining experiences and fund raising |

|

6 |

Business |

A local restaurant that helps workers in substance-abuse recovery by offering employment opportunities |

|

7 |

Business |

An organization spanning across the Appalachian region aimed at improving the quality of life for residents primarily through loan services |

|

8 |

Nonprofit |

A pay-what-you-can community restaurant with a mission to reduce food waste and end hunger by providing access to healthy food security in the local community. Closed due to COVID-19, |

|

9 |

Nonprofit |

A regionally based organization aimed at helping domestic violence survivors through counseling, housing, medical care, and rehabilitation services. Two governance bodies for its SE and nonprofit programs |

|

10 |

Nonprofit |

An organization that spans 6 Appalachian states focused on food security through education and infrastructure resources. Its SE programs are governed somewhat separately from its nonprofit programs |

|

11 |

Business |

A local organization focused on affordable housing through new construction, rental, and rehabilitation services |

|

12 |

Nonprofit |

A regionally based organization, offering loan services for start-up businesses and organizations |

|

13 |

Business |

A local nonprofit organization aiming to help individuals ranging from mental and physically disabled groups to formerly incarcerated individuals by providing vocational and employment services |

|

14 |

Business |

Modeled after Organization 8 but in a different community in the state. The organization seeks to overcome food insecurity through food services and education |

|

15 |

Business |

A local coffee shop with the mission to help those with special needs and promote inclusion through services to the local community |

Performing Tensions: Challenges in Social Impact Measurement and Dual Goal Balance

Three SEs reported experiencing performing tensions. Two business entities shared a common concern—they could well capture indicators for business goals but lacked guidance on measuring social impact. For example, one organization offering coding training admitted no record of job placements after training, lacking a tangible indicator of social mission success. The other business entity facing performing tension stated the tension came from limited time to collect social impact data while keeping the business running. The other organization that reported performing tension was a local nonprofit that helps survivors of intimate partner violence. They tracked how many programs were implemented, products made and sold, and the number of people returning to shelters after attending programs. They also stated frankly that “it is hard to differentiate social and commercial goals.” This nonprofit (ID 9) has two separate governance bodies: one about nonprofit advocacy while the other about social enterprise sales.

Organizing Tensions: Policy Influences, Labor Force Constraints, and Sustained Earned Revenue Models

Eight organizations (four businesses and four nonprofits) reported organizing tensions, including policy influence impacting the labor force, small local labor pools, lack of sustainable earned revenue models, and prioritizing feasible issue areas. The two community pay-what-you-can restaurants, one nonprofit and one business, both faced organizing tensions in attracting customers and recruiting local workers. Multiple organizations reported that the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these organizational tensions, with the nonprofit pay-what-you-can restaurant forced to shut down.

Furthermore, one organization that focused on equitable career training services pointed out the influence of politics on their operation. They stated that:

“Since I joined as the director, our state and federal funds is drying up… You have your highs and lows running a business but politics can make it worse. One hardship that we experienced was just a couple of years ago where Governor XX had cut the budget, and he no longer allowed for categories of individuals with disabilities to be served through the vocational rehabilitation program. And so it cut our budget down for a couple of years now… To me, politically, it’s the biggest challenge.”

Belonging Tensions: Internal and External Pressure on Organizational Identity

Five organizations reported belonging tensions, three nonprofits and two businesses. The lone certified B-corporation explored expanding its business to further social missions through pro bono work and diversity hiring. Belonging tensions arose not just internally but also from external social pressure due to the organizations’ social missions and advocacy for minority groups. A business co-founder admitted facing constant pressure to become a nonprofit, as their organization aimed to support black farmers through cultural tours and farm-to-table events:

“... we were heavily pressured to become a nonprofit. And that cursor is still very, very, very much there, which I’m crumbling and cracking. There is a portion of my business that I will transition into a nonprofit, solely so we can expand our ability to get grants and other engagements. But we are definitely a social enterprise. They are for the profit of our community. And we focus on dining for cause events working with nonprofits to help the socially and financially vulnerable.”

For nonprofit SEs, belonging tensions occurred primarily because the term SE generated confusion and arrived much later than the founding of the organization. One organization that provides vocational and employment services to individuals facing mental and physical disability and formerly incarcerated. They stated that.

“To be honest, we’ve never defined ourselves as a social enterprise. We’ve always talked about ourselves as a nonprofit… I always approach it from the Community Research Project angle, which in and of itself really does constitute being a social enterprise organization. Terminology has never been placed. We’ve never utilized that terminology. We just never get inherently recognized either. For me personally, it was all about working for an organization that didn’t just give people stuff but impacts their future by enhancing and helping them to be more self-sufficient.” The other two nonprofits experiencing belonging tension both had dual governance bodies (one for nonprofit and one for SE sector) (ID9 and ID10).

Learning Tensions: Scaling Up and Balance of Short-Term and Long-Term Goals

Ten organizations reported learning tensions. Six of them were businesses; four were nonprofits. Main concerns included how to scale up business, be more competitive, and be better at advocacy and community outreach. One organization (the B-corporate ID 4) stated that “The more embedded in the process, the more problems you discover… What is also important is how to diversify hiring. Attracting similar-minded people also leads to a lack of diversity in thinking, which causes challenges to our business.”

The balance between short-term and long-term goals is another example of learning tensions constantly referred to by participants. One organization (ID 8) providing the pay-what-you-can meals reported that 55% of its revenue came from the cafe program while the other 45% from fundraising; however, they constantly struggle to convince customers of their mission and to “set clear boundaries so people would not take advantage of the system.” The restaurant’s shutdown during the COVID-19 demonstrated the dire situation of learning tensions.

The Role of Cross-Sector Collaboration of SEs in Sustaining Organizational Forms

The sampled SEs reported prevalent cross-sector collaboration. All organizations reported partnering with other sectors: two (1 nonprofit, 1 business) to identify and recruit stakeholders and clients, four (1 nonprofit, 3 businesses) for community engagement, three (all businesses) for funding, four (1 nonprofit, 3 businesses) to create name recognition, six (2 nonprofits, 4 businesses) to implement programs, four (all businesses) for hosting events, and 5 (3 nonprofits, 2 businesses) for unspecified activities.

Partnerships for Assessing Impact and Building Legitimacy

Organizations emphasized the need for such collaboration and how partners can help assess priority issues to tackle given limited resources. As one organization (ID 12) stated:

“There are so many complex issues and that we can’t do all of it ourselves. So figuring out what we can do, aligning that with what we see are the greatest priorities needed in the region. And then figuring out how we can most effectively work with other organizations and communities to actually help farmers.”

Several organizations pointed out that partnerships help with impact assessment, which addresses performing tensions. One key argument brought up by an organization (ID 10) was that partnerships force organizations to share responsibility and data. Another organization (ID 9) worked with a flagship state university to develop impact indicators (e.g., the effectiveness of healing for their clients who suffered intimate partner violence). At the state or city level, they also benefited from technical assistance and support from a SE alliance.

Collaborations to Address Organizing and Learning Tensions

When addressing organizing tensions, several organizations mentioned leveraging partnerships to build an earned revenue model. For example, a business SE focused on affordable housing (ID11) emphasized forming cross-sector partnerships to identify clients and diversify services. This included working with a local addiction recovery facility to build a customer base and aid client reentry, as well as alliances with tourism organizations and government agencies to secure construction contracts. The SE also partnered with other SEs (e.g., ID7) to create a support network.

Partnerships have also been viewed as a way to gain legitimacy when the general public has confusion about what a SE is, which addresses belonging tensions. One respondent stated that people tended to view her as disqualified due to her background. She shared her experience of working with partners to bring recognition and legitimacy to her work:

“The more and more we’ve worked through this, the more and more people are taking it seriously. As a Black female under 40, living in XX, also an industry outsider… I had to bring up my 20+ years of working experience since I was 13 years old, my track record, to speak for itself. So I have dedicated myself to proven results, getting people in my network results… What really helped to push the business was me always working with groups of people to move them from point A to point B, towards more solvency, more equity, towards more stabilization in their community and their quality of life. We hosted events together, implemented different programs together. It really helped with our branding.”

The most challenging institutional tension faced by most of the organizations was learning tensions. Cross-sector partnerships have been mentioned by multiple interviewees as a strategy to address growth and scalability challenges. The founder of a dining club that provides funding to local nonprofits by hosting cultural events and supporting minority-owned or serving businesses (ID 5) stated:

“When we can support persons of color, through our work, not only from giving money but also getting those people involved in terms of where we get our ingredients for events or who’s actually making the food. That is something that we look to as a fundamental aspect of our partnerships. Without these partnerships, we wouldn’t really make a difference in the community. We were able to assemble our advisory committee by asking community leaders and nonprofit employees. But moving beyond that, we partnered with blacked-owned businesses, local nonprofits that serve refugees, just to name a few examples. We need long-term relationships to make our impact possible.”

A Typology of Partnerships to Manage Institutional Tensions

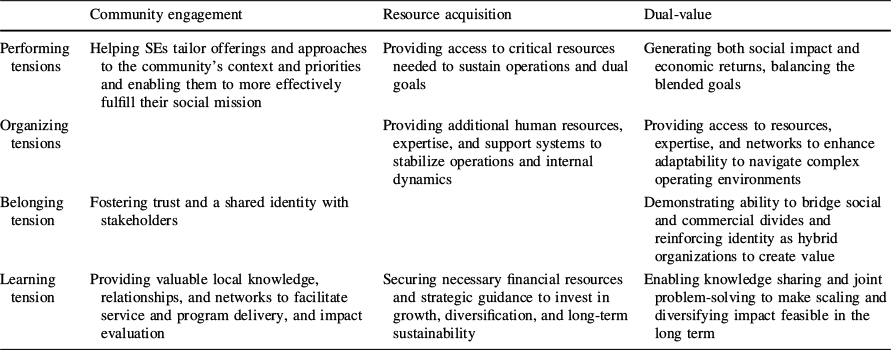

The above-mentioned cross-sector alliance strategies suggest that SEs of various forms may engage in integrated partnerships to manage institutional challenges and gain moral legitimacy, rather than just pursuing pragmatic legitimacy. The variety of cross-sector partnerships reported can be broadly categorized into three types: community engagement partnerships, resource acquisition partnerships, and dual-value partnerships. The specific characteristics and purposes of these partnership types are discussed in more detail below and are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2 Typology of SE cross-sector partnerships in response to institutional tensions

|

Community engagement |

Resource acquisition |

Dual-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Performing tensions |

Helping SEs tailor offerings and approaches to the community’s context and priorities and enabling them to more effectively fulfill their social mission |

Providing access to critical resources needed to sustain operations and dual goals |

Generating both social impact and economic returns, balancing the blended goals |

|

Organizing tensions |

Providing additional human resources, expertise, and support systems to stabilize operations and internal dynamics |

Providing access to resources, expertise, and networks to enhance adaptability to navigate complex operating environments |

|

|

Belonging tension |

Fostering trust and a shared identity with stakeholders |

Demonstrating ability to bridge social and commercial divides and reinforcing identity as hybrid organizations to create value |

|

|

Learning tension |

Providing valuable local knowledge, relationships, and networks to facilitate service and program delivery, and impact evaluation |

Securing necessary financial resources and strategic guidance to invest in growth, diversification, and long-term sustainability |

Enabling knowledge sharing and joint problem-solving to make scaling and diversifying impact feasible in the long term |

First, SEs can leverage community engagement partnerships to address performing, belonging, and learning tensions. These partnerships help SEs understand local needs, establish credibility, and build relationships to effective address community issues. This ensures SEs’ offerings and approaches are tailored to community context and priorities, enabling them to more effectively fulfill social mission and addressing performing tension. Strong community engagement partnerships signal the SE’s commitment to the local community and help build trust, allowing the SE to establish its legitimacy and name recognition, addressing the belonging tension. Furthermore, community partners provide valuable local knowledge, relationships, and networks that can be leveraged to more effectively deliver services and programs. This local embeddedness is crucial for SEs to have a meaningful impact and remain responsive to evolving community needs, addressing the learning tension.

Second, resource acquisition partnerships can be utilized to secure funding, implement programs, and access resources to sustain operations. They help SEs address performing, organizing, and learning tensions. Resource acquisition partnerships can help SEs manage performing tensions by providing funding and other resources to sustain their operations and fulfill dual goals. Through these partnerships (e.g., joint funding application, hosting fund-raising events), SEs can secure the necessary financial resources to invest in measuring and demonstrating social impact, helping balance competing performance demands. Resource acquisition partnerships help SEs manage organizing tensions by providing additional human resources, expertise, and support systems. These partnerships can help stabilize the organization’s operations and enable SEs to better retain and manage their workforce, addressing key aspects of organizing tensions. Resource acquisition partnerships also aid in managing learning tensions by securing the necessary financial resources and strategic guidance for SEs to invest in growth, diversification, and long-term sustainability. For example, interviewees mentioned the launch of innovative programs with a variety of sectors (e.g., partnering with minority-owned businesses to host ticketed cultural events) to establish an earned revenue model.

Third, another type of alliance is dual-value partnerships to purposefully address both social and business goals. The dual-value partnerships help achieve both value capture and creation. They can be helpful for managing all four tensions. SEs can leverage dual-value partnerships to generate both social impact and economic returns, balancing the blended goals and addressing performing tensions. They also provide SEs access to a variety of resources, expertise, and networks that can help overcome organizing challenges and enhance adaptability to navigate complex operating environments. Furthermore, dual-value partnerships help SEs gain greater legitimacy by demonstrating ability to bridge social and commercial divides and reinforcing their identity as hybrid organizations that create value in multiple ways, thus addressing belonging tensions. Finally, knowledge sharing and joint problem-solving inherent in dual-value partnerships can facilitate organizational learning for the SEs. Scaling and diversifying their impact become more feasible by leveraging the complementary capabilities of the partner organizations, with the intention to scale up both social and economic impact in the long term.

Discussion

This study examines the role of cross-sector partnerships in managing institutional tensions derived from SEs’ dual goals. Based on interview data collected from 15 SEs, it unpacks partnership patterns and rationales reported by organizational leaders. In this section, implications are discussed regarding strategies employed by SEs to address issues related to identity, legitimacy, and earned revenue models. The context of diverse issues addressed by the sampled organizations is also provided to interpret the findings. A typology of partnership activities is proposed to offer implications on how SEs of different organizational forms may leverage partnerships to manage institutional tensions.

Institutional Tensions and Opportunities for Moral Legitimacy

To begin with, SEs registered as businesses and nonprofits expressed different concerns related to performing tensions. For business SEs, the challenge lies in assessing the achievement of social mission; while for nonprofit SEs, it is difficult to differentiate the assessment indicators for social and business goals. Several nonprofits had two separate governance structures to address concerns and needs from different stakeholders. These results on performing tensions suggest a lack of synergy between social and business goals.

Another striking difference is with belonging tensions. Business SEs faced pressure from the public and potential funders to be nonprofits due to their social mission, while nonprofit SEs reported confusion over the term “social enterprise” as it was a later addition to their long-standing organizations. The existence of belonging tensions indicates that managing the multiple identities and stakeholder expectations associated with the SE label is challenging.

Organizations reported common concerns related to organizing and learning tensions, regardless of organizational forms or legal status. Many organizations highlighted limited resources for managing labor force and the influence of politics, which captured organizing tensions. The confusion related to what they do as SEs also generated challenges in retaining employees and customers. Learning tensions are about growth and scaling up of impact. SEs taking on either business or nonprofit forms admitted concerns in balancing the dual missions and managing the long-term versus short-term goals. These common challenges regardless of organizational forms further suggest that SEs encounter real and on-going tensions in daily operation but also growth goals (Lewis et al., Reference Lewis, Erickson, Potts, Watling and Vázquez2020).

This study also examined what partnerships were enacted by SEs of varying organizational forms to manage institutional tensions. Results showed that cross-sector partnerships built by SEs often involved a high level of integration. The most frequently mentioned partnerships were implementing programs, hosting events, creating name recognition, and community engagement. These diverse activities showed significant effort to obtain moral legitimacy to comply with norms and values represented by SEs. For example, creating name recognition speaks directly to the reality that the public has confusion about what SE stands for. Whether an organization is registered as a nonprofit or business, the dual focus also triggers the legitimacy question such as why a nonprofit is trying to create an earned revenue model or why a business is trying to achieve social mission.

The results related to partnerships did not suggest a strong connection to pragmatic legitimacy. It is possible that the sampled organizations in this study had established their organizational forms, thus no pressure to fulfill expectations from a regulatory entity. This further suggests that the moral legitimacy attributed to managing multiple institutional identities is more urgent for SEs (Huybrechts & Nicholls, Reference Huybrechts and Nicholls2013).

Furthermore, diverse partnership activities reported by SEs also demonstrated the importance of such alliances in addressing institutional tensions. More integrated partnerships signal strong commitment from the participating organizations and are more sustained in value creation (Austin, Reference Austin2010; Santos, Reference Santos2012). For example, SEs forming partnerships with other sectors to engage in impact assessment, creating a shared responsibility to help manage performing tensions. Partnerships built for name recognition help to brand what SEs stand for and to address belonging tensions. For more demanding tensions such as organizing and learning, sustaining integrated partnerships help with the growth of customer bases but also the co-achievement of business and social goals. This suggests that cross-sector partnerships could help with both value capture and creation (Santos, Reference Santos2012). However, in most of the sampled organizations, this is still more of an aspirational goal.

Another finding worth noticing is that five organizations reported unspecified partnership activities. This indicates that formalizing partnerships with clear goals is not an institutionalized practice among SEs. One explanation is that the organization is still assessing their partnership needs, and the resources required to formalize such alliances.

It is also worth noting that the overarching types of tensions (performing, organizing, belonging, learning) were experienced across the diverse set of social enterprises, regardless of their specific issue focus. Similarly, the three types of cross-sector partnerships (community engagement, resource acquisition, dual-value) were utilized by social enterprises working in different domains. While the specific nature of the tensions and partnership activities may vary to some degree based on the social issue focus, the core findings regarding the prevalence of institutional tensions and the role of cross-sector collaboration in managing these tensions appear to hold true across the wide range of social issues represented in the sample. This indicates that the results and implications of the study are likely applicable to social enterprises addressing a variety of social challenges, rather than being limited to a particular issue area.

Contributions and Limitations

This study makes two contributions. First, it advances institutional theory by demonstrating how SEs of different organizational forms (nonprofit vs. for-profit) leverage cross-sector partnerships as a strategic mechanism to navigate institutional tensions. By applying this theoretical lens, the paper provides a more nuanced understanding of how hybrid organizations use external relationships to manage competing demands and sustain their dual mission. Secondly, the typology of three partnership strategies (i.e., community engagement, resource acquisition, and dual-value) offers practical guidance for practitioners, revealing how organizations can strategically collaborate with diverse stakeholders to balance their social and commercial goals. For instance, the findings suggest nonprofit SEs may prioritize community engagement partnerships to bolster their social legitimacy, while for-profit SEs may focus more on resource acquisition partnerships to secure the necessary funding and support to scale their business model.

Several limitations from this study warrant future research. First, this study was conducted solely within a southeastern U.S. state, which may limit the generalizability of the findings for SEs operating in other regional or national contexts that could face distinct institutional pressures and partnership opportunities. Future studies may draw from a more diverse sample to further explore how organizational forms and partnerships relate to institutional tensions. Second, this study draws from cross-sectional data. Incorporating a longitudinal element could reveal how SEs’ partnership strategies and approaches to managing institutional tensions evolve as they grow and mature. Third, this study is based on qualitative interview data. Incorporating quantitative analysis, such as tracking performance metrics, could provide additional insights into the specific mechanics, dynamics, and outcomes of cross-sector partnerships. Mixed-methods approaches could also strengthen the rigor and generalizability of the study’s conclusions. For example, one potential factor to examine would be organizational age, which may influence the amount and type of collaboration SEs engage in. Future research can investigate how the timing of various tensions identified in this study may be related to an organization’s life cycle and age.

Conclusion

This study investigates how SEs of various forms encounter institutional tensions and leverage interorganizational partnerships in managing specific tensions. Findings from interviews with SE leaders suggest that organizations, especially those registered as businesses, struggled to balance and measure financial versus social goals, suggesting performing tensions. Nonprofit SEs utilized dual governance structures to address performing tensions. Organizing tensions were tied to policy change, small labor pools, and the need to balance earned revenue models, regardless of organizational forms. In addition, the pressure to be a nonprofit or a business and the confusion around the SE identity generated belonging tensions. Furthermore, SEs, both in business and nonprofit forms, grappled with scaling up, diversifying, and balancing short-term and long-term goals as they sought to grow their impact, suggesting learning tensions.

Three types of integrated partnerships emerged as SEs navigated competing demands from diverse stakeholders and complex logics: community engagement, resource acquisition, and dual-value. The typology proposed suggests that SEs can proactively seek out cross-sector collaborations that allow them to more effectively manage the various institutional tensions they face as hybrid organizations. The partnerships serve as a strategic mechanism to balance and align these competing expectations.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all the organizational leaders who participated in the interviews.

Funding

This study was funded by College of Communication and Information at University of Kentucky.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This study involved human participants and was approved by a university ethics committee. The participants received informed consent prior to the interviews.