Introduction

Recent decades have brought about rising immigration, stringent economic constraints and deepening welfare retrenchment. A sizeable literature has explored how ethnic diversity and attitudes to immigration affect popular support for economic redistribution (e.g., Alesina et al., Reference Alesina, Murard and Rapoport2019, Reference Alesina, Miano and Stantcheva2023; Brady & Finnigan, Reference Brady and Finnigan2014; Burgoon & Rooduijn, Reference Burgoon and Rooduijn2021; Eick & Busemeyer, Reference Eick and Busemeyer2023; Finseraas, Reference Finseraas2008; Garand et al., Reference Garand, Xu and Davis2017; Muñoz & Pardos‐Prado, Reference Muñoz and Pardos‐Prado2019).Footnote 1 Considerably fewer analyses have examined the impact of welfare state dynamics on natives' views about immigration. Indeed, while existing work highlights the centrality of economic and cultural considerations for individual immigration attitudes (e.g., Ceobanu & Escandell, Reference Ceobanu and Escandell2010; Hainmueller & Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014; Pardos‐Pardo & Xena, Reference Pardos‐Pardo and Xena2019), relatively few studies investigate how welfare policies shape these attitudes. This is surprising given the politicization of both immigration and welfare state reforms in the aftermath of the Great Recession, the European sovereign debt crisis, and the European refugee crisis of the late 2000s and the mid‐2010s.

Going beyond welfare chauvinism (e.g., Careja & Harris, Reference Careja and Harris2022), this paper adds to the large scholarship on general immigration attitudes by analysing the impact of welfare state dynamics. Drawing on previous research, we focus on two key mechanisms linking the structure of the welfare state to citizens' views about non‐natives. The first centres on the logics of inclusiveness underpinning different institutional designs and their implications for in‐group–out‐group relations (Crepaz & Damron, Reference Crepaz and Damron2009). While restrictive, means‐tested policies create stark divisions between beneficiaries and non‐beneficiaries, universal systems tend to promote solidarity (Titmuss, Reference Titmuss, Pierson and Castles2006). These different principles can in turn activate different value orientations informing individual attitudes towards immigration. The tight eligibility criteria characteristic of weaker welfare states tend to reinforce social categorizations and stigmatize benefit recipients, perpetuating prejudice and selective solidarity at the expense of out‐groups (Magni, Reference Magni2021, Reference Magni2024). Since immigrants are often perceived as disproportionately depending on welfare (Alesina et al., Reference Alesina, Miano and Stantcheva2023; van Oorschot, Reference Oorschot2006), they are likely to face stronger stigmatization and nativist resentment in weaker welfare states. In contrast, more generous welfare states tend to de‐emphasize social categorizations and thus foster more tolerant out‐group attitudes (Crepaz & Damron, Reference Crepaz and Damron2009).

The second mechanism focuses more directly on the instrumental role of the welfare state in protecting individuals from economic risks. Weaker welfare states often prove ineffective at addressing socio‐economic needs, further inflating economic concerns. Perceived economic threat and status decline tend to offer fertile ground for negative reactions to immigration (e.g., Kros & Coenders, Reference Kros and Coenders2019). By contrast, comprehensive welfare states provide more robust safety nets, which can reduce economic and status insecurity (Kirchner et al., Reference Kirchner, Freitag and Rapp2011). In a context of lessened anxiety, out‐group members are no longer perceived as directly threatening.

Our empirical strategy proceeds in two steps. We begin by pooling public opinion data from 16 Western European democracies between 2002 and 2019. We merge the first nine waves of the European Social Survey (ESS) with country‐level data on welfare generosity from the Comparative Welfare Entitlements Project dataset (Scruggs & Tafoya, Reference Scruggs and Tafoya2022; Scruggs, Reference Scruggs2022). Our results indicate that more comprehensive social systems are indeed correlated with more favourable immigration attitudes. This association is driven by differences in welfare generosity across countries rather than over time. This, however, may be because our key predictor exhibits limited temporal variation. Therefore, in the second step, we focus on an instance where policy change is more salient, visible and, therefore, noticeable to voters. Concretely, drawing inspiration from Larsen (Reference Larsen2018), we leverage a natural experiment whereby an educational reform was announced during the fieldwork of the sixth round of the ESS in Denmark. This episode also allows us to causally evaluate how changing welfare policies shape immigration views. Employing a regression discontinuity design (RDD), we find that welfare retrenchment increases hostility towards immigrants.

This paper makes three important contributions. First, we shed new light on the institutional drivers of public anti‐immigrant sentiment, highlighting the effect of welfare state generosity. In doing so, we complement the existing literature on welfare chauvinism (e.g. Careja & Harris, Reference Careja and Harris2022) by examining how welfare state dynamics affect general immigration attitudes. Second, building on prior scholarship, we identify and empirically test two key mechanisms underpinning the impact of welfare generosity on natives' views about immigrants. Specifically, we distinguish between an instrumental explanation that underscores economic anxiety and a value‐based perspective that centres on the logics of inclusiveness and, by extension, social tolerance promoted by different welfare systems. Lastly, we isolate the causal effect of a welfare retrenchment reform that allows us to more carefully evaluate how changes in social policy affect immigration attitudes.

This paper is structured as follows. Drawing on existing work, we begin by developing our expectations about the impact of welfare state arrangements on immigration attitudes. We proceed to outline our empirical strategy. Our findings are largely consistent with our hypotheses, linking positive out‐group sentiment to more generous social policy frameworks. The final section offers reflections on the implications of our results for political conflict in an age of rising immigration and heightened budget constraints.

Theory and expectations

Cultural and economic drivers of immigration attitudes

Broadly speaking, scholarship on the determinants of immigration attitudes falls into two research streams. Building on the political economy tradition, one highlights individual material self‐interest, arguing that natives tend to reject newcomers because the latter intensify competition over scarce resources such as jobs, wages, and social services (e.g., Mayda, Reference Mayda2006; Scheve & Slaughter, Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001; Cavaillé & Ferwerda, Reference Cavaillé and Ferwerda2023) or put a fiscal burden on host societies (Helbling & Kriesi, Reference Helbling and Kriesi2014; Naumann et al., Reference Naumann, Stoetzer and Pietrantuono2018). This literature, therefore, sees individual opposition to immigration as mainly grounded in egotropic concerns linked to one's own economic circumstances.

Rooted in a range of socio‐psychological approaches, the second, more heterogeneous, strand links anti‐immigrant sentiment to mostly cultural, but also economic, concerns about the implications of rising diversity for the national community. In this body of work, views that immigration negatively impacts values, traditions or the national way of life are particularly consequential (for an exhaustive review, see Hainmueller & Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014). Antecedents of such views may be found in a variety of predispositions such as prejudice, ethnocentrism or the salience of national and social identities, among others (Ivarsflaten & Sniderman, Reference Ivarsflaten and Sniderman2022; Kam & Kinder, Reference Kam and Kinder2007; Sniderman et al., Reference Sniderman, Hagendoorn and Prior2004).

While symbolic factors and sociotropic explanations have received solid empirical support (Hainmueller & Hiscox, Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2007; Hainmueller & Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014; Hopkins et al., Reference Hopkins, Margalit and Solodoch2024; Sides & Citrin, Reference Sides and Citrin2007; Valentino, Reference Valentino, Soroka, Iyengar, Aalberg, Duch, Fraile and Kobayashi2019), egotropic perspectives linked, for instance, to labour market competition have exhibited rather limited explanatory power (e.g., Hainmueller & Hiscox, Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2010; Hainmueller & Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014; Helbling & Kriesi, Reference Helbling and Kriesi2014; Hjorth, Reference Hjorth2016; Naumann et al., Reference Naumann, Stoetzer and Pietrantuono2018). Nevertheless, recent scholarship underlines that particular conditions, such as sectoral or fiscal exposure to immigration, may enhance the material self‐interest logic (Dancygier & Walter, Reference Dancygier, Walter, Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015; Gerber et al., Reference Gerber, Huber, Biggers and Hendry2017; Malhotra et al., Reference Malhotra, Margalit and Hyunjung Mo2013; Pardos‐Pardo & Xena, Reference Pardos‐Pardo and Xena2019).

Despite its richness, the existing literature on the determinants of individual attitudes to immigration has paid less attention to institutions. Welfare states are especially theoretically relevant for immigration attitudes because ‘[i]dentifying the state – [and, by extension,] the ‘welfare state’ – inherently requires delineating who is ‘in’ (citizens of the state) and ‘out’ (non‐citizens)’ of the community it creates (Reeskens & Van Oorschot, Reference Reeskens and Van Oorschot2012, p. 122). Conceptions of in‐group boundaries therefore underpin both out‐group hostility in general and ideas about access to social provision in particular.

In an early study on this question, Crepaz and Damron (Reference Crepaz and Damron2009) used cross‐sectional data to show that universal welfare systems tend to be associated with greater attitudinal favourability to immigration. More recent research focuses on specific manifestations of welfare and public goods provision, suggesting that additional factors can complicate this relationship. For instance, Cremaschi et al. (Reference Cremaschi, Rettl, Cappelluti and De Vries2024) find that a reduction in access to public services tends to benefit radical right parties by raising concerns about immigration. Similarly, Cavaillé and Ferwerda (Reference Cavaillé and Ferwerda2023) show that granting immigrants access to already congested public housing programmes in Austria is associated with the rising popularity of far‐right parties.

This paper takes a step back and seeks to understand the direct impact of the structure of the welfare system on voters' general attitudes to immigration. We proceed to develop our theoretical expectations, focusing on two key mechanisms that closely map the material self‐interest and the socio‐psychological approaches outlined above.

Welfare regimes and immigration attitudes

How do welfare regimes affect immigration attitudes, and through what underlying channels? Building on existing scholarship, we focus on two key channels that, without being necessarily exhaustive, are theoretically relevant.

The first mechanism centres on the idea that different welfare regimes promote distinct logics of inclusion, which in turn have diverging consequences for the extent to which individuals draw on in‐group–out‐group thinking (Crepaz & Damron, Reference Crepaz and Damron2009). As a consequence, they are likely to activate different value orientations informing individual attitudes to immigration. More concretely, encompassing welfare systems rest more heavily on the principle of universalism. By limiting natives' propensity to rely on social categorization and decreasing the salience of group boundaries, they tend to induce more favourable views of non‐nationals. As they cover everyone, universal social frameworks can cultivate inclusiveness, which fosters tolerance, reduces prejudice and instils a sense of community. Designed to ‘keep people out’, means‐tested systems, in contrast, reinforce divisions between benefit recipients and non‐recipients (Crepaz & Damron, Reference Crepaz and Damron2009; Titmuss, Reference Titmuss, Pierson and Castles2006, 45). Such divides may engender nativist resentment as they undermine solidarity and identification with out‐groups (Titmuss, Reference Titmuss, Pierson and Castles2006). This mechanism, therefore, places values of inclusiveness and identity considerations surrounding membership in a collective that determines deservingness at the forefront (Koning, Reference Koning2022).

This argument is consistent with a line of theoretical and empirical work that highlights the positive implications of comprehensive welfare systems for pro‐social attitudes and behaviours. In particular, the ‘crowding in’ perspective suggests that more generous welfare regimes are more conducive to social capital (e.g., van Oorschot & Arts, Reference Oorschot and Arts2005). Studies have shown that large welfare states are indeed associated with higher levels of social trust and trust in institutions (Brewer et al., Reference Brewer, Oh and Sharma2014; Kumlin & Rothstein, Reference Kumlin and Rothstein2005; van Oorschot & Arts, Reference Oorschot and Arts2005). Research on immigration attitudes in turn highlights the positive association between political and social trust, on the one hand, and pro‐immigrant sentiment on the other (Herreros & Criado, Reference Herreros and Criado2009; Macdonald & Cornacchione, Reference Macdonald and Cornacchione2023; Macdonald, Reference Macdonald2021; Sides & Citrin, Reference Sides and Citrin2007).

The second mechanism highlights the instrumental role of the welfare state in shielding citizens from socio‐economic risks. Kirchner et al. (Reference Kirchner, Freitag and Rapp2011) posit that institutions that promote inclusiveness act as catalysts for social tolerance primarily because they alleviate economic and status anxiety. Intensifying globalization, which often entails rising international migration, trade competition and accelerating technological change, exposes individuals to heightened risk and may exacerbate feelings of economic vulnerability, labour market insecurity and relative deprivation. These might increase perceptions of ethnic threat and lead natives to blame out‐groups for their (perceived) worsening personal circumstances. Indeed, existing work shows that economic hardship, competition with migrants over scarce resources and perceived job insecurity can trigger anti‐immigrant resentment (Pardos‐Pardo & Xena, Reference Pardos‐Pardo and Xena2019; Scheepers et al., Reference Scheepers, Gijsberts and Coenders2002). Similarly, exposure to imports and accelerated automation has been shown to boost opposition to immigration and support for radical right parties (Colantone & Stanig, Reference Colantone and Stanig2018; Wu, Reference Wu2022).

Welfare arrangements might attenuate such threat perceptions. Generous social policy regimes generally protect citizens from risk and provide access to crucial benefits and services. In the context of lessened economic and occupational status anxiety, individuals may be less responsive to perceived threats. Inclusive and decommodifying welfare states can thus promote more positive immigration attitudes. Less generous systems, in contrast, often prove unable to successfully address socio‐economic needs and mitigate status anxiety (Kirchner et al., Reference Kirchner, Freitag and Rapp2011).Footnote 2 While the empirical evidence is more limited, recent work does reveal a positive correlation between subjective economic risk and perceptions of ethnic threat (Kros & Coenders, Reference Kros and Coenders2019).

The mechanisms outlined above point in a similar direction. Thus,

1 Hypothesis Encompassing welfare systems are associated with more positive immigration attitudes.

Empirically adjudicating between these two mechanisms is challenging, though not impossible. We argue that if welfare arrangements affect out‐group sentiments through the value‐based channel, which captures the value orientations triggered by different logics of inclusiveness corresponding to each type of welfare system, we would expect institutions to have a long‐term effect on individual views. Several studies show that, once shaped, immigration attitudes and preferences may be slow to change (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Hainmueller and Hangartner2023; Kustov et al., Reference Kustov, Laaker and Reller2021; Laaker, Reference Laaker2024). Institutional effects should therefore be visible over the longer term. In other words, past welfare generosity should foster present‐day tolerance as perceptions about out‐groups persist over time. By this logic,

1a Hypothesis Past welfare generosity is associated with more positive current immigration attitudes.

In contrast, if material considerations underlie the relationship between welfare arrangements and immigration attitudes, we would expect the effect to vary across socio‐economic groups and national economic conditions. Low‐income individuals should experience higher levels of economic anxiety, caused, for instance, by competition with migrants, technological change or trade‐induced labour market disruptions.Footnote 3 Furthermore, the welfare state might also be particularly relevant during times of economic hardship. Deteriorating economic conditions often manifest in high unemployment rates, forcing many to rely on social programmes. The resulting economic uncertainty can then exacerbate status anxiety and sharpen perceptions of threats related to immigrant out‐groups. Consequently,

1b Hypothesis Lower welfare state generosity is associated with more negative immigration attitudes among the most economically vulnerable.

1c Hypothesis Lower welfare state generosity is associated with more negative immigration attitudes during times of deteriorating economic conditions.

To test our hypotheses, we employ a two‐step empirical strategy that combines repeated cross‐sectional data analysis with a regression discontinuity design. The former investigates whether welfare generosity is associated with mass favourability to immigration in a variety of contexts. Drawing inspiration from Larsen (Reference Larsen2018), the latter takes advantage of the timing of an educational reform in Denmark to causally assess how policy changes reflecting welfare state retrenchment shape views about immigration. Previous research shows that similar reforms have led to political disaffection and lower support for incumbents (Fetzer, Reference Fetzer2019; Larsen, Reference Larsen2018).

Empirical strategy

Repeated cross‐sectional analysis

Data and methods

We begin by focusing on general attitudes towards immigration. Using nine rounds of the ESSFootnote 4 conducted in 16 Western European countries between 2002 and 2018,Footnote 5 we create an index out of three survey items. These instruments inquire whether respondents think that (1) immigration is good or bad for their country's economy, (2) immigrants undermine or enrich their country's cultural life and (3) immigrants make their country a better or worse place to live. The immigration attitudes index is constructed as the average response to the three questions, with higher values indicating more favourable views.Footnote 6

In the second step, we follow prior research (i.e., Crepaz & Damron, Reference Crepaz and Damron2009) and focus on two alternative dependent variables that in fact capture natives' evaluations of newcomers' impact on the labour market. The first reflects the agreement that ‘[a]verage salaries and wages are generally brought down by people coming to live and work’ in respondents' home country. The second asks whether ‘[i]mmigrants take jobs away or create new jobs’. These items allude to two common economic risks – unemployment and loss of income – that threaten natives' standard of living. They allow us to replicate and extend previous findings.Footnote 7 While the first question was fielded as part of a special thematic module on immigration in the first round of the ESS, the second was included in 2002 and 2014.

Our main independent variable is the aggregate total generosity index from the Comparative Welfare Entitlements Project Data Set (version 2022–12) (Scruggs and Tafoya Reference Scruggs and Tafoya2022, Scruggs, Reference Scruggs2022). Totgen is calculated based on the benefit replacement rates, qualifying conditions and coverage and take‐up rates of the three broadest social protection programmes – unemployment, sickness and pensions. As such, it comes closest to reflecting the extent to which individuals can maintain a livelihood without reliance on the market and are relatively protected from market‐generated economic insecurity (Esping‐Andersen, Reference Esping‐Andersen1990). Consistent with Crepaz and Damron (Reference Crepaz and Damron2009), we prefer this measure to social spending, which is much more sensitive to fluctuations in economic conditions, does not necessarily capture the state's ability to effectively shield citizens from risk, does not reveal how expenditures are allocated, and occasionally responds to immigration flows (Allan & Scruggs, Reference Allan and Scruggs2004; Soroka et al., Reference Soroka, Johnston, Kevins, Banting and Kymlicka2016). Figure A1 in the Online Appendix details cross‐country and over‐time variation in welfare generosity.

Our models include a battery of individual and country‐level characteristics that might affect immigration attitudes (Table A1 in the Online Appendix shows descriptive statistics for all variables included in the repeated cross‐sectional analyses). At the individual level, we control for respondents' age, gender, income, education, employment status, social class, and religiosity.Footnote 8 Additional analyses (Table A3 in the Online Appendix) add trust in people, ideological self‐placement, and progressive values (Crepaz & Damron, Reference Crepaz and Damron2009). At the country level, we account for unemployment and GDP per capita growth rates.Footnote 9 Although the impact of objective indicators of immigration is unclear (e.g., Sides & Citrin, Reference Sides and Citrin2007; Claassen and McLaren, Reference Claassen and McLaren2022), we include the percentage of foreign‐born individuals between the ages of 15 and 64 residing in the host country.Footnote 10 Controlling for exposure to immigration enables us to account for both threats by immigration and contact with immigrants (Andersson & Dehdari, Reference Andersson and Dehdari2021; Dinas et al., Reference Dinas, Matakos, Xefteris and Hangartner2019; Hangartner et al., Reference Hangartner, Dinas, Marbach, Matakos and Xefteris2019; Homola & Tavits, Reference Homola and Tavits2018). Dropping this variable or replacing it with immigration inflows (Margalit & Solodoch, Reference Margalit and Solodoch2022) leaves our results largely unchanged (see Table A8 in the Online Appendix).Footnote 11 All country‐level covariates are measured in the year preceding each respondent's interview.Footnote 12 To account for the layered structure of our dataset – respondents nested in country‐survey rounds nested in countries – we run hierarchical models with random country‐wave and country intercepts.

Results

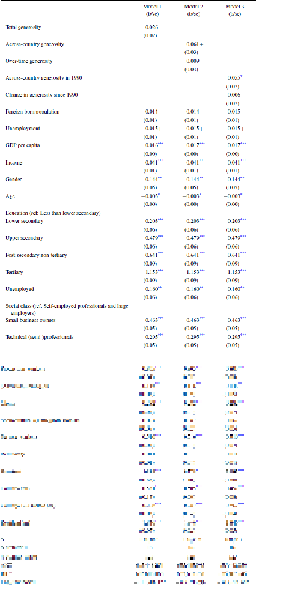

Table 1 presents the results from our analysis based on the general immigration attitudes index. As a reminder, higher values indicate agreement that immigrants have a positive impact on the host country's society, culture and economy. We only include survey participants born in the country.Footnote 13 We pool data from 9 ESS waves, 16 countries and 125 country waves.

Table 1. Effects of welfare state generosity on immigration attitudes

Note: ***![]() , **

, **![]() , *

, *![]() , +

, +![]() .

.

AIC: Akaike's Information Criterion; BIC: Bayesian Information Criterion.

The welfare generosity index does not reach statistical significance in Model 1. Nevertheless, this estimate is not particularly informative because it combines ‘within’ and ‘between’ effects. In other words, it simultaneously captures the impact of welfare generosity both across countries and over time. A more complex story emerges once we distinguish between cross‐sectional and longitudinal dynamics in Model 2. Concretely, we follow Fairbrother (Reference Fairbrother2014) and decompose welfare generosity into country‐specific means and year‐specific deviations from these means. While the former reflects country‐specific latent welfare generosity (‘between’ effects), the latter accounts for short‐term fluctuations in generosity (‘within’ effects). The country‐mean component emerges as a positively signed, statistically significant (at the 10 per cent level) predictor of attitudes (95 per cent confidence intervals: [−0.001; 0.123]). This suggests that citizens of countries with more decommodifying welfare states tend to hold more positive opinions about immigration. In line with Hypothesis 1, this finding supports the idea that generous social policies promote favourability to immigration. In contrast, round‐specific deviations from the country‐mean do not correlate with mass attitudes. This might be because temporal variation in the total generosity index is rather limited (see Figure A1 in the Online Appendix), making it difficult for voters to notice changes and adjust their attitudes accordingly. We will return to this point below.

We conduct robustness checks with several other survey items capturing a range of different immigration attitudes – support for immigrants of the same race/ethnic group as the majority, support for immigrants from a different racial/ethnic group, support for immigrants from poorer countries in or outside Europe, perceptions that immigrants take out more than they put in and beliefs that immigrants fill in jobs in which there is a shortage of workers. Our results remain largely unchanged (see Tables A9–A11 in the Online Appendix). In fact, welfare generosity reaches higher levels of statistical significance (p‐value ![]() 0.05 or 0.01) in all but two of these models (when the dependent variable measures preferences for the admission of migrants of the same racial or ethnic group and migrants from poor European countries).

0.05 or 0.01) in all but two of these models (when the dependent variable measures preferences for the admission of migrants of the same racial or ethnic group and migrants from poor European countries).

How long‐lasting is this association? If the value‐based channel is at play and comprehensive welfare states foster inclusiveness, we would expect that the structure of the welfare state would have an enduring impact on attitudes. Past levels of decommodification would thus shape modern‐day beliefs (Hypothesis 1a). To test this possibility, we look into the level of total generosity in 1990. Many advanced capitalist countries were forced to cut benefits, slash social spending and retrench existing programmes in the 1990s and the 2000s (Huber & Stephens, Reference Huber and Stephens2001). Including the level of decommodification before this process crystallized allows us to check if historic welfare generosity meaningfully predicts modern views even in light of more recent welfare dynamics. Accordingly, Model 3 includes two variables: one capturing welfare generosity in 1990 and one measuring the change in welfare generosity since then. We find that long‐term dynamics are indeed at play: past generosity is associated with more positive attitudes to immigration measured decades later, whereas changes in generosity levels since 1990 do not seem to matter.

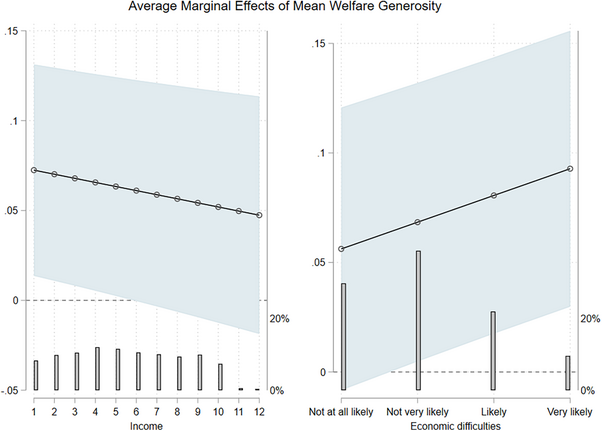

Our work so far indicates that welfare generosity has implications for how natives view non‐native out‐groups. A related question is whether this relationship varies across different socio‐economic groups and economic conditions. Hypotheses 1b and 1c, which build on the instrumental channel, propose that it should. Given the structure of social protection across Europe – most welfare states tend to be oriented towards low‐income households – comprehensive welfare institutions might be particularly effective at reducing economic anxiety and perceptions of threat among those earning lower incomes or facing higher economic insecurity. To test this argument, we interact the cross‐country component of the generosity index with income and a measure of economic hardship.Footnote 14

Figure 1 plots the average marginal effect of (country‐mean) welfare generosity over the range of income and economic hardship (see Table A5 in the Online Appendix for the full regression tables). The right‐hand panel suggests that a one‐unit increase in generosity is associated with greater favourability to immigration among respondents who fall in the bottom 5 deciles of the income distribution.Footnote 15 In contrast, it fails to reach statistical significance for individuals who report high incomes. Similarly, as illustrated by the left‐side panel, the impact of the welfare state is significant for citizens who expect to struggle financially in the near future. It is not different from zero among those who consider future economic difficulties less likely. Consequently, the effect of welfare generosity appears to be noticed mainly among the less fortunate. While this is consistent with the instrumental perspective, according to which comprehensive welfare systems decrease anti‐immigrant sentiments by reducing economic anxiety among vulnerable segments, the effect of welfare generosity is always positive, even among respondents who report higher incomes and a lower likelihood of experiencing economic difficulties. This is in line with the idea that the welfare state also operates through a values‐based channel.

Figure 1. Effect of mean generosity over the range of income and economic hardship (95 per cent confidence intervals).

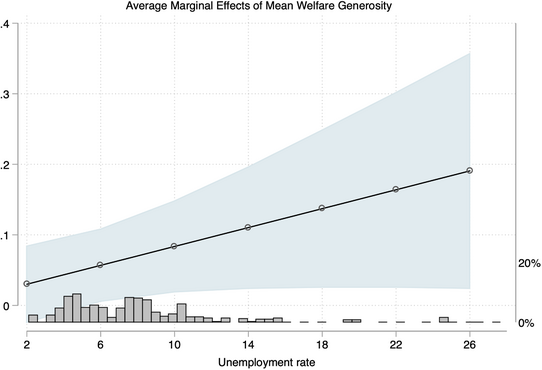

Next, we focus on times of high unemployment, when economic risk is particularly heightened. Figure 2 plots the marginal effect of country‐mean welfare generosity over the range of the unemployment rate (see Table A5 in the Online Appendix for the full regression output). This effect is positive and statistically significant once the national unemployment rate exceeds 5 per cent. This finding offers further evidence that social protection programmes foster more favourable views of immigrants by potentially alleviating underlying feelings of economic anxiety. Again, the coefficient is positively signed even at lower unemployment rates, although it does not reach statistical significance.

Figure 2. Marginal effect of mean welfare generosity by the unemployment rate.

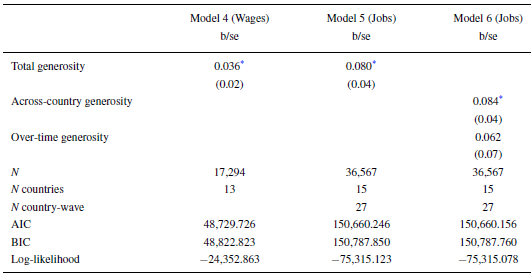

To replicate and extend previous findings, the next stage of our analysis directly zooms in on perceptions of immigrants' impact on wages and jobs. Model 4 in Table 2 (full output in Table A4 in the Online Appendix) uses disagreement that ‘immigrants bring wages down’ as an outcome of interest. Like Crepaz and Damron (Reference Crepaz and Damron2009), it covers 13 countries during the first round of the ESS. Models 5 and 6 instead focus on the disagreement that ‘immigrants take jobs away’. These regressions draw on 15 countries during the 2002 and the 2014 ESS waves, which allows us to estimate the effect of welfare generosity decomposed into country‐means and temporal deviations from these means.

Table 2. Effects of welfare state generosity on immigration attitudes

Note: ***![]() , **

, **![]() , *

, *![]() , +

, +![]() .

.

AIC: Akaike's Information Criterion; BIC: Bayesian Information Criterion.

Mean welfare generosity emerges as a meaningful predictor of immigration attitudes in all three models. This indicates that social regimes with higher replacement rates, laxer eligibility criteria and broader coverage alleviate concerns that immigrants bring wages down or take jobs away from natives. Like before, time‐specific deviations from the country‐mean do not reach statistical significance in Models 5 and 6.

Our results so far suggest that more generous welfare regimes are associated with more positive immigration attitudes. Nevertheless, one might argue that natives' favourability could diminish in contexts of high exposure to immigration if this phenomenon is perceived as fiscally costly and eroding the sustainability of the welfare state (e.g., Naumann et al., Reference Naumann, Stoetzer and Pietrantuono2018; Hanson et al., Reference Hanson, Scheve and Slaughter2007). Such concerns might be especially strong in comprehensive systems, whose maintenance costs depend on broad contributions and might be strongly politicized (Helbling & Kriesi, Reference Helbling and Kriesi2014; Naumann et al., Reference Naumann, Stoetzer and Pietrantuono2018; Burgoon & Schakel, Reference Burgoon and Schakel2022). Observing such dynamics could possibly cast some doubt on our value‐based channel because this mechanism does not pre‐suppose a particular level of exposure to immigration (low or high).

To further explore this possibility, Table A21 in the Online Appendix includes an interaction term between welfare generosity and the foreign‐born population. Since immigrants tend to be less skilled than natives in Europe, the fiscal sustainability argument would expect the effect of welfare generosity to diminish and even become negative as the immigrant stock increases. We do not find a significant interaction between the two contextual variables. Marginal effects plots (Figure A5 in the Online Appendix) indicate that, while the effect of welfare generosity is positive and statistically significant at lower levels of immigrant stocks, it slightly decreases as the foreign‐born population grows. Nevertheless, the coefficient remains positive, albeit not statistically significant, even at high levels of exposure to immigration. Evidence in favour of the fiscal sustainability concerns argument thus appears to be weak, if at all present. Importantly, separate analyses show that the immigrant groups that are most likely to exacerbate concerns about welfare sustainability – poor newcomers from European or non‐European countries – are not viewed more negatively in more generous welfare states (Table A10 in the Online Appendix). Similarly, generous welfare systems are actually associated with more positive assessments of immigrants' contribution to the social policy system and the national labour market (Table A11 in the Online Appendix).Footnote 16

Do the effects vary by income level, instead? Some studies suggest that exposure to immigration in contexts characterized by high fiscal exposure might particularly affect the immigration views of rich individuals who risk experiencing reduced benefits or higher taxes (Hanson et al., Reference Hanson, Scheve and Slaughter2007; Naumann et al., Reference Naumann, Stoetzer and Pietrantuono2018). Whether observing such dynamics would contradict our instrumental channel or not is less clear‐cut, but it remains an interesting matter to explore. To examine this question, we add three‐way interactions between income, welfare generosity and the size of the foreign‐born population (Table A22 in the Online Appendix). We do not find major differences between low‐ and high‐income voter groups. The coefficient for welfare generosity remains positive, albeit not always statistically significant, for both groups, regardless of how strongly the country is exposed to immigration (Figure A6 in the Online Appendix). We tentatively conclude that these additional analyses do not generally disprove our proposed mechanisms.

Our analysis so far has relied on observational data, which limits our ability to draw causal conclusions. Indeed, our results are mainly associational. Although our models control for the most likely confounders, we cannot causally isolate the effect of welfare generosity on immigration attitudes or discard the possibility of omitted variable bias. Furthermore, examining how changes in welfare generosity affect our outcome of interest is challenging because the total generosity index exhibits limited variation over time. This is consistent with the reality of policy‐making, which tends to be strongly path dependent and generally devoid of large sudden fluctuations (Pierson, Reference Pierson2000; Huber & Stephens, Reference Huber and Stephens2001). Small changes might remain unobserved by voters, making them less likely to influence public views. Overall perceptions of the social policy regime's inclusivity and general ability to shield citizens from risk would instead be more consequential. This could explain why the longitudinal component of the welfare generosity index does not reach statistical significance in the hierarchical models reported above.

For these reasons, in the next section, we turn our attention to an instance where individuals were more likely to perceive a clear, discernible change in the structure of the welfare state. Drawing inspiration from Larsen (Reference Larsen2018), we consider a natural experiment surrounding the implementation of a contentious educational reform in Denmark. Apart from giving us additional analytical leverage, this analysis also broadens our focus beyond the unemployment, sickness and healthcare domains of the welfare state.

RDD analysis

In early 2013, the Danish government announced cuts to an educational grants program that provides financial assistance to of‐age individuals enrolled in active studies. At the time of the announcement, Denmark had the most generous educational loan system in the world (Ministry of Research, Innovation, and Higher Education 2013). By Danish law, all students above the age of 18 are entitled to financial support, a comparatively high proportion of which comes in the form of grants. The reform envisioned substantial budget cuts (2.2 billion DKK), lowering benefit levels and introducing stricter eligibility criteria (Larsen, Reference Larsen2018). Designed to improve public finances and shorten completion times, the proposed amendments decreased the period of benefits receipt, reduced monthly payments for students living at home, limited access to a sixth year of support, automatically enrolled students in exams and changed indexing rules. While most students were expected to be only moderately affected, those living at home saw a significant decrease in their monthly payments (Myklebust, Reference Myklebust2013).

Previous work has shown that the proposed measures gained considerable popular attention after they were officially unveiled. Larsen (Reference Larsen2018) highlights that the reform received extensive coverage in mass media, with articles mentioning it spiking after February 19th, when it was publicly announced. Importantly, the amendments were not part of a broader reform package (Larsen, Reference Larsen2018). They were therefore communicated to the public as a clear episode of retrenchment in a state where, according to results from the 2011 Danish National Election Study, a majority of citizens expressed support for higher spending on education. Existing research has revealed that education policies are closer to the median voter and thus enjoy high salience and popular support (Busemeyer et al., Reference Busemeyer, Garritzmann and Neimanns2020; Larsen, Reference Larsen2018).

Coincidentally, the reform was shared with the public during the fieldwork for the sixth round of the ESS. This timing lends itself to a natural experiment (Larsen, Reference Larsen2018), allowing us to explore whether – and how – changes in the design and structure of the welfare state affect immigration attitudes. We can thus compare the group of respondents interviewed right before the announcement on February 19th with the one interviewed right after it.

Denmark is a particularly relevant case for the purpose of our analysis because immigration has become one of the most politically salient issues in recent years (Green‐Pedersen & Otjes, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Otjes2019; Green‐Pedersen & Krogstrup, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Krogstrup2008). This increase in salience has been driven not only by rising immigration but also by the growing popularity of radical right political actors (Green‐Pedersen & Otjes, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Otjes2019). The Danish People's Party (DF) became the third most‐voted party in the 2011 parliamentary elections, winning 12.3 per cent of the popular vote (Kosiara‐Pedersen, Reference Kosiara‐Pedersen2017) and forcing mainstream right‐wing parties to pay more attention to immigration due to coalition building and issue ownership pressures (Bale et al., Reference Bale, Green‐Pedersen, Krouwel, Luther and Sitter2010; Green‐Pedersen & Otjes, Reference Green‐Pedersen and Otjes2019). When it comes to voters, recent research suggests that growing party polarization on immigration has generated increasing polarization among Danish citizens (Arndt, Reference Arndt2016).

Similar to Larsen (Reference Larsen2018), we employ a sharp regression discontinuity design to estimate the effect of the reform announcement on immigration attitudes. We begin by checking for potential discontinuity at the cut‐off date. Following Cattaneo et al. (Reference Cattaneo, Idrobo and Titiunik2019), Figure A11a in the Online Appendix plots the binned outcome means in the raw data against the time distance from the cut‐off date, along with a fourth‐order polynomial regression fit of immigration attitudes on time.Footnote 17 A negative jump at the cut‐off is visible: average immigration attitudes appear less positive immediately following the announcement than right before it. Figure A11 also shows that the bin‐specific mean outcomes are more heavily spread out towards higher values of the outcome variable before the reform was unveiled and that they take on lower values and are less dispersed after that.

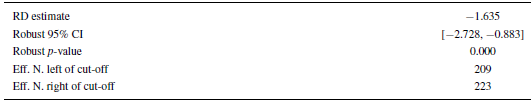

Having identified a jump at the cut‐off, we proceed with a formal test of the treatment effect. We employ a local polynomial point estimation with an MSE (mean squared error)‐optimal bandwidth. More specifically, we use a local linear RD estimator and choose a first‐order polynomial with a triangular kernel function, as recommended by Cattaneo et al. (Reference Cattaneo, Idrobo and Titiunik2019). Table 3 shows the RD treatment effect with the confidence intervals computed using the robust bias correction approach (Cattaneo et al., Reference Cattaneo, Idrobo and Titiunik2019, p. 58). The coefficient for the treatment variable is negative (i.e., −1.63 points), suggesting that the reform announcement negatively affected immigration attitudes. Given the 0–10 range of the dependent variable, this effect is not negligible. Importantly, it appears to be generalized to the entire population, as different analyses conducted both with the pooled sample (see Table 3) and with subsets of respondents affected differently by the reform yield similar results. This finding implies that, over the short term, welfare cuts can increase hostility towards immigrants. It confirms hypothesis H1, as it suggests that policy changes that erode the generosity of social provision decrease mass favourability to immigration.

Table 3. RD estimates

We ran a number of validation and falsification tests to assess the robustness of our results (Cattaneo et al., Reference Cattaneo, Idrobo and Titiunik2019). First, we examined whether there are discontinuities in predetermined covariates – age, gender, education, social class, and region – at the cut‐off point. We do not find evidence of such discontinuities. In other words, treated and control units do not seem to systematically differ on these covariates at the cut‐off (Table A27 in the Online Appendix). Second, we replicated our analysis with a placebo outcome (Valentim et al., Reference Valentim, Núñez and Dinas2021), replacing immigration attitudes with attitudes towards homosexuals. Reassuringly, the treatment variable coefficient fails to reach statistical significance (Table A26 in the Online Appendix). Third, we confirmed the continuity of the score density around the cut‐off (Figure A7 in the Online Appendix). Fourth, we re‐ran the analysis with placebo cut‐offs (10 days before and 10 days after the announcement). We do not find discontinuities at these artificial cut‐offs (Figure A8 in the Online Appendix). Fifth, we dropped observations near the cut‐off (1 and 2 days before and after February 19th). The results are still significant at the 0.05 and 0.1 level, respectively (Figure A9 in the Online Appendix). Lastly, we analysed sensitivity to bandwidth choices; our results remain robust (see Figure A10 in the Online Appendix). These tests inspire confidence in the validity of the design.

We note that the causal effect we capture is local in nature and that it is not representative of treatment effects that would characterize observations further away from the cut‐off (Cattaneo et al., Reference Cattaneo, Idrobo and Titiunik2019).

Our results suggest that the Danish educational reform undermined general favourability to immigration. An open question is whether this episode actually reflects welfare retrenchment, or if it speaks to a different treatment linked more closely to the policy realm of education. Indeed, previous research has shown that schooling reforms can shape immigration attitudes (Cavaillé & Marshall, Reference Cavaillé and Marshall2019). We believe that the policy change we focus on is less related to the ‘education‐as‐character‐shaping’ arguments developed in earlier work on schooling reforms (Cavaillé & Marshall, Reference Cavaillé and Marshall2019). The RD study captures effects that are much more immediate and local in nature. Indeed, we compare individuals interviewed immediately before and after the reform announcement. Given this time horizon, our case differs from the educational reforms considered in existing work. Already identified as an episode of welfare retrenchment in previous research (Larsen, Reference Larsen2018), this policy change mainly limited the amount and duration of financial support provided to young adults (Myklebust, Reference Myklebust2013, Ministry of Research, Innovation, and Higher Education, 2013). It can thus be seen as having a commodifying effect, capturing the same dynamics as the generosity index we use in the repeated cross‐sectional analysis above. Similar to it, the reform affected replacement rates, eligibility criteria and the general ability of the welfare state to protect citizens from socio‐economic risk.

In any case, we also examined if the cross‐sectional patterns uncovered by the analysis based on the generosity index (Table 1) apply to the policy realm of education. To do so, we re‐ran Models 1 and 2 with public education spending as a percent of GDP. Like before, the cross‐sectional component of education spending returns a positively signed statistically significant coefficient. The over‐time element remains insignificant (see Table A14 in the Online Appendix).

Conclusion

Immigration and welfare politics have become increasingly interconnected in European countries (Burgoon & Rooduijn, Reference Burgoon and Rooduijn2021). While existing research sheds light on the impact of immigration on popular support for redistribution, our knowledge of how welfare states affect nativist resentment is more limited.

This paper seeks to improve our understanding of these dynamics. We focus on two potential mechanisms through which welfare arrangements might shape out‐group sentiments – a value‐based perspective, according to which social institutions reinforce divisions or instil tolerance, and an instrumental approach, whereby generous social policies protect people from risk and alleviate perceptions of economic anxiety.

Our results suggest that encompassing welfare states are associated with more positive immigration attitudes. Based on repeated cross‐sectional analyses drawing on public opinion data from 16 countries over almost two decades, we find provisional empirical support for both the values‐based and the instrumental explanations. Past and current levels of welfare generosity have implications for contemporary views. Furthermore, individual financial vulnerability (both objective and subjective) and national deteriorating economic conditions make citizens more sensitive to the effect of welfare systems. This implies that the relationship between social policies and out‐group sentiments is complex and multifaceted.

At the same time, results from a regression discontinuity design indicate that the announcement of a welfare retrenchment reform in February 2013 produced a negative effect on the immigration attitudes of Danish citizens. As we find local average treatment effects in the general population, and not exclusively among particular sub‐groups affected more directly by the reform, these results seem to be more congruent with the value‐based mechanism. The reform might have induced natives to embrace parochial altruism (Kustov, Reference Kustov2021). Our findings imply that the introduction of retrenching social policy reforms has the potential to provoke negative reactions, increasing hostility towards immigrants. Future research should explore whether this reaction persists in time, how long it survives, and how it is used by political elites.

Our conclusions should be interpreted in light of the limitations of our empirical analysis. The hierarchical models allow us to evaluate the extent to which the relationship between immigration attitudes and welfare institutions is generalizable to a variety of contexts. Nevertheless, although views on pension, unemployment and sickness policy should not be heavily influenced by immigration, we cannot fully discard concerns about reverse causation (welfare states responding to, rather than influencing, public opinion). The Danish welfare reform study gives us the opportunity to alleviate these concerns to some extent since the empirical strategy consists of leveraging the quasi‐random nature of the welfare reform announcement. Yet, the focus on a particular policy area (education) raises the question of whether our findings replicate in other policy domains. Future research should explore this issue.

Moreover, one might ask whether our results are driven by the self‐selection of immigrants into more generous welfare systems. If large immigrant stocks provide more opportunities for positive contact and habituation (Claassen & McLaren, Reference Claassen and McLaren2022), we should see a positive correlation between welfare generosity and attitudes towards migrants. This is indeed what we find. Nevertheless, recent causally identified research casts doubt on the welfare magnet hypothesis (Ferwerda et al., Reference Ferwerda, Marbach and Hangartner2024). Furthermore, the foreign‐born population control never returns a statistically significant coefficient in our models, even when we drop our main explanatory variable, nor is it highly correlated with welfare generosity in our data. In any case, even if this argument were true, welfare generosity still precedes and underlies the immigration stock.

Despite these limitations, our findings have important implications for the relationship between immigration and welfare state arrangements. While previous research suggests that immigration erodes support for redistribution, we show that less generous welfare systems undermine pro‐social attitudes such as favourability to immigrant out‐groups. Importantly, our findings highlight new theoretical puzzles that should be pursued in future research.

First, while we try to adjudicate between two mechanisms that might underpin the relationship between welfare state dynamics and immigration attitudes, further research should pay greater attention to the potential role of welfare sustainability concerns in shaping general immigration attitudes. How political elites might alter these dynamics is particularly consequential. Existing work suggests that citizens do react to information about the costs of immigration and the sustainability of the welfare system (Finseraas et al., Reference Finseraas, Haugsgjerd and Kumlin2023; Goerres et al., Reference Goerres, Karlsen and Kumlin2020). As the future of the welfare state has become increasingly politicized by political parties (Burgoon & Schakel, Reference Burgoon and Schakel2022), exploring how the latter affects the ability of welfare regimes to inform mass opinion opens up a new avenue for research.

Second, it is, in our view, an open question whether individual perceptions about migrants' welfare deservingness could potentially mediate the relationship between welfare state generosity and general immigration attitudes. One cannot discard an alternative process whereby welfare systems affect general immigration attitudes through other channels (such as those explored here), which might in turn have spill‐over effects on how people evaluate immigrants' deservingness of welfare and their overall contribution to (or reliance on) the welfare system. For example, important work has established differences in deservingness stereotypes across welfare states, with respondents in Denmark being more inclined to believe that social welfare recipients are unlucky and respondents in the United States being more likely to see them as lazy (Aarøe & Petersen, Reference Aarøe and Petersen2014). Given the endogeneity between these attitudinal variables, shedding further light on these processes might demand nuanced theorizing coupled with careful (quasi‐)experimental designs.

Third, we also encourage further research on whether different types of welfare regimes trigger differences in the strength of national identification, which may in turn shape mass opinion about immigration. Shayo (Reference Shayo2009), for instance, finds a negative correlation between levels of redistribution and the strength of national attachment in the electorate. This reinforces the idea that more redistributive regimes may reduce natives' propensity to rely on social categorizations along nationality criteria, thereby reducing anti‐immigrant sentiment. Some of our robustness checks (Table A18 in the Online Appendix) seem to support this possibility, which represents an important avenue for future research.

Finally, further research should examine the extent to which the effect of welfare generosity on immigration attitudes might be conditioned by sub‐national dynamics, such as contact with immigrants at the local level. In particular, research on how regional distribution of migrants might occur in response to welfare state dynamics appears particularly interesting to illuminate additional mechanisms underpinning the connection between welfare regimes and individual views about immigration.

To conclude, our results suggest that institutions shape how citizens view immigrant‐induced ethnic diversity in advanced European democracies. Periods of austerity, however, can alter this impact in complex ways.

Funding

Alina Vrânceanu acknowledges funding from European Union‐NextGenerationEU, Ministry of Universities and Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan, through a call from Universitat Pompeu Fabra (María Zambrano Grant, 2022–2024). Bilyana Petrova acknowledges funding from the University of Zurich's Research Priority Program (URPP) ‘Equality of Opportunity’.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. We are also grateful to Kaitlin Alper, Frank Thames, Andreas Wiedemann, Gabriele Magni, Rahsaan Maxwell, Kevin Grier, Simone Schneider and participants at the UNC Workshop on Economic Inequality, the 2022 MPSA, EPSA, CES, and Texas Comparative Circle conferences, as well as the 2023 JCPOP meeting, for thoughtful comments. The two co‐authors contributed equally to this article. All remaining errors are ours.

Data Availability Statement

The data and replication files are available through OSF at the following link: https://osf.io/2d39x/.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Online Appendix