1. Introduction

Melting of ice bodies or solid particles plays a central role in diverse natural and industrial contexts, ranging from oceanography and planetary science to astrophysics and metallurgy (Davis Reference Davis2001). When external flows are present, whether driven by buoyancy or imposed by forced convection, the surrounding temperature field is altered, producing complex body interface morphologies during melting. These evolving interfaces, in turn, modify the flow by acting as moving boundaries. Understanding this coupled fluid–thermal–interface dynamics is essential for predicting iceberg ablation (Cenedese & Straneo Reference Cenedese and Straneo2023), interpreting the formation of magma oceans (Ulvrová et al. Reference Ulvrová, Labrosse, Coltice, Råback and Tackley2012), reconstructing the thermal histories of icy moons (Gastine & Favier Reference Gastine and Favier2025) and controlling solidification defects in metallurgical processes (Shevchenko et al. Reference Shevchenko, Boden, Gerbeth and Eckert2013).

Overthe past two decades, significant progress has been achieved through laboratory experiments, numerical simulations and theoretical analyses. Much of this progress has relied on simplified model systems. A canonical configuration is Rayleigh–Bénard convection (Lohse & Shishkina Reference Lohse and Shishkina2024), where buoyancy drives turbulent motion that interacts with a melting boundary. The closed geometry and high experimental controllability of this set-up make it an attractive framework for studying melting dynamics (Du, Calzavarini & Sun Reference Du, Calzavarini and Sun2024). Foundational contributions include the experiments by Davis, Müller & Dietsche (Reference Davis, Müller and Dietsche1984) and the simulations by Ulvrová et al. (Reference Ulvrová, Labrosse, Coltice, Råback and Tackley2012), Rabbanipour Esfahani et al. (Reference Rabbanipour Esfahani, Hirata, Berti and Calzavarini2018) and Favier, Purseed & Duchemin (Reference Favier, Purseed and Duchemin2019), which revealed unsteady processes such as convective roll mergers and shell-like melting fronts. These studies also proposed scaling laws for interface evolution and melting rates derived from energy balances. Recent extensions of this framework have incorporated additional physical complexities to better approximate geophysical and engineering scenarios. Examples include the anomalous temperature dependence of water density (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Calzavarini, Sun and Toschi2021a ), ambient shear and turbulence (Couston et al. Reference Couston, Hester, Favier, Taylor, Holland and Jenkins2021; Ravichandran, Toppaladoddi & Wettlaufer Reference Ravichandran, Toppaladoddi and Wettlaufer2022; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Howland, Liu, Verzicco and Lohse2023) and double-diffusive effects in solute-laden systems (Xue, Zhang & Ni Reference Xue, Zhang and Ni2024; Guo & Yang Reference Guo and Yang2025). Such modifications have been shown to exert profound influence on interface morphology and melting rates. For instance, Couston et al. (Reference Couston, Hester, Favier, Taylor, Holland and Jenkins2021) demonstrated that turbulent kinetic energy promotes ripple- and scallop-like structures, while Xue et al. (Reference Xue, Zhang and Ni2024) showed that solute concentration gradients can suppress convective transport, thereby inhibiting morphological pattern formation.

In contrast to Rayleigh–Bénard convection, where melting typically occurs at extended boundaries, a complementary class of problems involves melting bodies of finite extent immersed in open flows. This scenario is particularly relevant to iceberg ablation, which exhibits nonlinear sensitivity to ocean currents (FitzMaurice, Cenedese & Straneo Reference FitzMaurice, Cenedese and Straneo2017). Both the magnitude and shear of surface flows strongly control melting rates and interface morphology (Wagner et al. Reference Wagner, Wadhams, Bates, Elosegui, Stern, Vella, Abrahamsen, Crawford and Nicholls2014; FitzMaurice & Stern Reference FitzMaurice and Stern2018). A simplified yet fundamental model considers a stationary ice body in a uniform current, isolating the role of forced convection from buoyancy-driven drift. Pioneering experiments by Hao & Tao (Reference Hao and Tao2001, Reference Hao and Tao2002) on ice spheres in horizontal flows demonstrated that melting rates increase with both fluid velocity and temperature, and that enhanced wake circulation downstream promotes heat transfer, leading to flattened rear surfaces. Orientation-dependent melting rates have since been widely reported. For example, Hester et al. (Reference Hester, McConnochie, Cenedese, Couston and Vasil2021) showed that vertical faces melt faster than horizontal ones in saline flows. More recently, numerical studies by Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Howland, Liu, Verzicco and Lohse2024a ,Reference Yang, van den Ham, Verzicco, Lohse and Huisman b ) and Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Yang, Verzicco and Lohse2025) established that melting rate depends non-monotonically on body aspect ratio, and developed scaling arguments based on distinct conductive and convective contributions. Despite such complexities, experiments and simulations consistently indicate that the upstream face of melting spheres converges to a self-similar profile (Hao & Tao Reference Hao and Tao2001; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Howland, Liu, Verzicco and Lohse2024a ). Comparable shape evolution has also been reported for eroding or dissolving bodies in unidirectional flows (Ristroph et al. Reference Ristroph, Moore, Childress, Shelley and Zhang2012; Moore et al. Reference Moore, Ristroph, Childress, Zhang and Shelley2013; Huang et al. Reference Huang, Jinzi, M.Nicholas and Ristroph2015, Reference Huang, Tong, Shelley and Ristroph2020), where boundary-layer models accurately capture the emergence of self-similar forms. In turbulent environments, generated for instance by meltwater plumes or subglacial discharge, local flow intensification can further accelerate melting rates (Machicoane, Bonaventure & Volk Reference Machicoane, Bonaventure and Volk2013; McCutchan, Meyer & Johnson Reference McCutchan, Meyer and Johnson2024).

While recent work has advanced the quantification of melting rates and global heat transfer efficiency, comparatively little is known about the associated flow dynamics and hydrodynamic loading. In particular, detailed information on the time evolution of wake structures and force histories for melting bodies is scarce. Moreover, most numerical studies have focused on two-dimensional (2-D) geometries such as circles and ellipses (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Howland, Liu, Verzicco and Lohse2024a

,Reference Yang, van den Ham, Verzicco, Lohse and Huisman

b

), leaving three-dimensional (3-D) effects largely unexplored. This gap is significant because the wake behind a non-melted rigid sphere undergoes well-documented bifurcations: a steady axisymmetric-to-planar transition near

![]() $\textit{Re}\approx 212$

(Magnaudet & Mougin Reference Magnaudet and Mougin2007), a Hopf bifurcation to periodic vortex shedding near

$\textit{Re}\approx 212$

(Magnaudet & Mougin Reference Magnaudet and Mougin2007), a Hopf bifurcation to periodic vortex shedding near

![]() $\textit{Re}\approx 273$

(Fabre, Auguste & Magnaudet Reference Fabre, Auguste and Magnaudet2008) and ultimately a chaotic 3-D state at higher Reynolds numbers (Ern et al. Reference Ern, Risso, Fabre and Magnaudet2012). How these canonical wake transitions are altered when the sphere is melting and its shape evolves remains poorly understood.

$\textit{Re}\approx 273$

(Fabre, Auguste & Magnaudet Reference Fabre, Auguste and Magnaudet2008) and ultimately a chaotic 3-D state at higher Reynolds numbers (Ern et al. Reference Ern, Risso, Fabre and Magnaudet2012). How these canonical wake transitions are altered when the sphere is melting and its shape evolves remains poorly understood.

Motivated by this question, we present 3-D direct numerical simulations of a melting sphere across the initial Reynolds number range

![]() $25 \leqslant \textit{Re}_0 \leqslant 1000$

. A sharp-interface method (Xue et al. Reference Xue, Zhao, Ni and Zhang2023, Reference Xue, Zhang and Ni2024), based on a hybrid volume-of-fluid (VOF) and embedded-boundary (EB) method, is employed to resolve the flow and temperature fields in both liquid and solid phases separately, with interfacial conditions enforced explicitly. We consider a pure substance without solutal effects to focus on thermal melting under forced and mixed convection. The paper is organised as follows. The governing model and numerical approach are introduced in § 2. Section 3 examines flow patterns and interfacial morphologies across parameter regimes when buoyancy force is excluded. Section 4 quantifies melting rates, comparing with classical scaling laws and incorporating shape effects to improve prediction. Section 5 analyses the time-dependent hydrodynamic forces and torques, while § 6 explores the influence of buoyancy-driven convection. Concluding remarks and perspectives are given in § 7.

$25 \leqslant \textit{Re}_0 \leqslant 1000$

. A sharp-interface method (Xue et al. Reference Xue, Zhao, Ni and Zhang2023, Reference Xue, Zhang and Ni2024), based on a hybrid volume-of-fluid (VOF) and embedded-boundary (EB) method, is employed to resolve the flow and temperature fields in both liquid and solid phases separately, with interfacial conditions enforced explicitly. We consider a pure substance without solutal effects to focus on thermal melting under forced and mixed convection. The paper is organised as follows. The governing model and numerical approach are introduced in § 2. Section 3 examines flow patterns and interfacial morphologies across parameter regimes when buoyancy force is excluded. Section 4 quantifies melting rates, comparing with classical scaling laws and incorporating shape effects to improve prediction. Section 5 analyses the time-dependent hydrodynamic forces and torques, while § 6 explores the influence of buoyancy-driven convection. Concluding remarks and perspectives are given in § 7.

2. Problem statement, governing equations and numerical method

The configuration considered is shown in figure 1. An initially spherical solid particle (

![]() $\varOmega ^s$

) of diameter

$\varOmega ^s$

) of diameter

![]() $D_0$

and uniform temperature

$D_0$

and uniform temperature

![]() $T=T_0$

is fixed at the origin

$T=T_0$

is fixed at the origin

![]() $\boldsymbol{x} = (x,y,z)= (0,0,0)$

and immersed in its warmer liquid phase (

$\boldsymbol{x} = (x,y,z)= (0,0,0)$

and immersed in its warmer liquid phase (

![]() $\varOmega ^\ell$

), representing the translational motion of a melting sphere. The liquid is incompressible and quiescent at

$\varOmega ^\ell$

), representing the translational motion of a melting sphere. The liquid is incompressible and quiescent at

![]() $t=0$

. A Cartesian coordinate system is adopted with the

$t=0$

. A Cartesian coordinate system is adopted with the

![]() $x$

axis aligned with the streamwise direction. At the inflow boundary (

$x$

axis aligned with the streamwise direction. At the inflow boundary (

![]() $x=-4D_0$

), uniform velocity

$x=-4D_0$

), uniform velocity

![]() $\boldsymbol{U} = (U_\infty , 0, 0)$

and temperature

$\boldsymbol{U} = (U_\infty , 0, 0)$

and temperature

![]() $T = T_\infty \gt T_0$

are prescribed, while an outflow condition is applied at

$T = T_\infty \gt T_0$

are prescribed, while an outflow condition is applied at

![]() $x=16D_0$

. Lateral boundaries (

$x=16D_0$

. Lateral boundaries (

![]() $y=\pm 10D_0$

,

$y=\pm 10D_0$

,

![]() $z=\pm 10D_0$

) are treated as adiabatic and free-slip.

$z=\pm 10D_0$

) are treated as adiabatic and free-slip.

Figure 1. Schematic of the numerical set-up (not to scale). A solid sphere composed of a pure substance with initial diameter

![]() $D_0$

, denoted by

$D_0$

, denoted by

![]() $\varOmega ^s$

, with uniform initial temperature

$\varOmega ^s$

, with uniform initial temperature

![]() $T = T_0$

, is immersed in its warmer liquid phase,

$T = T_0$

, is immersed in its warmer liquid phase,

![]() $\varOmega ^\ell$

, driven by an incoming flow. At the inflow boundary, a uniform velocity

$\varOmega ^\ell$

, driven by an incoming flow. At the inflow boundary, a uniform velocity

![]() $\boldsymbol{U} = (U_\infty , 0, 0)$

and temperature

$\boldsymbol{U} = (U_\infty , 0, 0)$

and temperature

![]() $T = T_\infty \gt T_0$

are imposed.

$T = T_\infty \gt T_0$

are imposed.

Using

![]() $D_0$

,

$D_0$

,

![]() $U_\infty$

and

$U_\infty$

and

![]() $\Delta T=T_\infty -T_0$

as characteristic length, velocity and temperature scales, the governing equations for the liquid phase are

$\Delta T=T_\infty -T_0$

as characteristic length, velocity and temperature scales, the governing equations for the liquid phase are

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}=(u_x,u_y,u_z)$

is the dimensionless velocity,

$\boldsymbol{u}=(u_x,u_y,u_z)$

is the dimensionless velocity,

![]() $p$

the kinematic pressure and

$p$

the kinematic pressure and

![]() $\theta =(T-T_0)/\Delta T$

the dimensionless temperature. The initial Reynolds, Prandtl and Richardson numbers are defined as

$\theta =(T-T_0)/\Delta T$

the dimensionless temperature. The initial Reynolds, Prandtl and Richardson numbers are defined as

with

![]() $\nu$

the kinematic viscosity,

$\nu$

the kinematic viscosity,

![]() $\alpha$

the thermal diffusivity,

$\alpha$

the thermal diffusivity,

![]() $\beta$

the thermal expansion coefficient and

$\beta$

the thermal expansion coefficient and

![]() $\boldsymbol{g}$

gravitational acceleration. The subscript ‘

$\boldsymbol{g}$

gravitational acceleration. The subscript ‘

![]() $0$

’ is adopted to distinguish it from a time-dependent effective Reynolds number

$0$

’ is adopted to distinguish it from a time-dependent effective Reynolds number

![]() $\textit{Re}_e$

in the following analysis. For the Richardson number, no such distinction is needed since only the initial value appears in the analysis; hence, we simply write

$\textit{Re}_e$

in the following analysis. For the Richardson number, no such distinction is needed since only the initial value appears in the analysis; hence, we simply write

![]() $\textit{Ri}$

without a subscript. The last term

$\textit{Ri}$

without a subscript. The last term

![]() $-\textit{Ri}\,\theta \,\boldsymbol{e}_i$

in (2.1) represents the thermal buoyancy force under the Boussinesq approximation. The unit vector

$-\textit{Ri}\,\theta \,\boldsymbol{e}_i$

in (2.1) represents the thermal buoyancy force under the Boussinesq approximation. The unit vector

![]() $\boldsymbol{e}_i$

specifies the direction of gravity, either parallel (

$\boldsymbol{e}_i$

specifies the direction of gravity, either parallel (

![]() $i = x$

) or perpendicular (

$i = x$

) or perpendicular (

![]() $i = y$

) to the streamwise direction. A linear dependence of liquid density on temperature is adopted here. The implications of using a more refined quadratic density–temperature relation are discussed in detail in § 6 and Appendix A. In the baseline simulations of the present study, buoyancy is neglected (

$i = y$

) to the streamwise direction. A linear dependence of liquid density on temperature is adopted here. The implications of using a more refined quadratic density–temperature relation are discussed in detail in § 6 and Appendix A. In the baseline simulations of the present study, buoyancy is neglected (

![]() $\textit{Ri} = 0$

), isolating forced convection with which we are mainly concerned. Mixed-convection cases, where buoyancy becomes comparable, are also examined in § 6. Both phases are assumed to have identical constant density, so that volume expansion due to melting is ignored. All other thermophysical properties are constant in the liquid.

$\textit{Ri} = 0$

), isolating forced convection with which we are mainly concerned. Mixed-convection cases, where buoyancy becomes comparable, are also examined in § 6. Both phases are assumed to have identical constant density, so that volume expansion due to melting is ignored. All other thermophysical properties are constant in the liquid.

At the receding interface

![]() $\varGamma$

, the no-slip condition

$\varGamma$

, the no-slip condition

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}=\boldsymbol{0}$

is imposed, consistent with neglecting volume expansion during melting. The Gibbs–Thomson effect, which accounts for curvature- and velocity-dependent interface temperature, is omitted, and the interface temperature is fixed at the melting point,

$\boldsymbol{u}=\boldsymbol{0}$

is imposed, consistent with neglecting volume expansion during melting. The Gibbs–Thomson effect, which accounts for curvature- and velocity-dependent interface temperature, is omitted, and the interface temperature is fixed at the melting point,

![]() $\theta _\varGamma =0$

, following the same principle of previous studies (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Howland, Liu, Verzicco and Lohse2024a

,

Reference Yang, van den Ham, Verzicco, Lohse and Huismanb

; Xue et al. Reference Xue, Zhang and Ni2024). Consequently, the solid remains isothermal at

$\theta _\varGamma =0$

, following the same principle of previous studies (Yang et al. Reference Yang, Howland, Liu, Verzicco and Lohse2024a

,

Reference Yang, van den Ham, Verzicco, Lohse and Huismanb

; Xue et al. Reference Xue, Zhang and Ni2024). Consequently, the solid remains isothermal at

![]() $T^s \equiv T_0$

(

$T^s \equiv T_0$

(

![]() $\theta ^s\equiv 0$

) during melting. The interfacial motion is governed by the Stefan condition, which links the melting rate to the temperature gradient across the interface:

$\theta ^s\equiv 0$

) during melting. The interfacial motion is governed by the Stefan condition, which links the melting rate to the temperature gradient across the interface:

where

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

is the local interface velocity and

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

is the local interface velocity and

![]() $\boldsymbol{n}$

the outward unit normal pointing into the liquid. The Stefan number

$\boldsymbol{n}$

the outward unit normal pointing into the liquid. The Stefan number

![]() $\textit{St} = c_p^\ell (T_\infty - T_0)/\mathcal{L}$

quantifies the ratio of sensible heat to latent heat, where

$\textit{St} = c_p^\ell (T_\infty - T_0)/\mathcal{L}$

quantifies the ratio of sensible heat to latent heat, where

![]() $c_p^\ell$

is the specific heat capacity of the liquid and

$c_p^\ell$

is the specific heat capacity of the liquid and

![]() $\mathcal{L}$

is the latent heat of fusion. Since

$\mathcal{L}$

is the latent heat of fusion. Since

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla }\theta ^s\equiv 0$

, (2.5) reduces to a condition in which the local melting rate depends solely on the temperature gradient on the liquid side.

$\boldsymbol{\nabla }\theta ^s\equiv 0$

, (2.5) reduces to a condition in which the local melting rate depends solely on the temperature gradient on the liquid side.

To illustrate the parameter space in physical terms, consider an ice sphere immersed in water at

![]() $T_\infty =20\,^\circ \textrm{C}$

and translating at

$T_\infty =20\,^\circ \textrm{C}$

and translating at

![]() $U_\infty =0.05\,\,\textrm{m s}^{-1}$

. Varying its diameter from

$U_\infty =0.05\,\,\textrm{m s}^{-1}$

. Varying its diameter from

![]() $0.5\,\textrm{mm}$

to

$0.5\,\textrm{mm}$

to

![]() $2\,\textrm{cm}$

yields

$2\,\textrm{cm}$

yields

![]() $25\leqslant \textit{Re}_0 \leqslant 1000$

, spanning the above regimes shown in figure 2(a). The Prandtl number is fixed at

$25\leqslant \textit{Re}_0 \leqslant 1000$

, spanning the above regimes shown in figure 2(a). The Prandtl number is fixed at

![]() $\textit{Pr}=7$

, representative of water at

$\textit{Pr}=7$

, representative of water at

![]() $20\,^\circ \textrm{C}$

. Additionally, unless otherwise specified, the Stefan number is fixed at

$20\,^\circ \textrm{C}$

. Additionally, unless otherwise specified, the Stefan number is fixed at

![]() $\textit{St}=0.25$

, corresponding to

$\textit{St}=0.25$

, corresponding to

![]() $\Delta T = 20\,^\circ \textrm{C}$

in water, to isolate the effect of

$\Delta T = 20\,^\circ \textrm{C}$

in water, to isolate the effect of

![]() $\textit{Re}_0$

on the melting dynamics. In §§ 4 and 5,

$\textit{Re}_0$

on the melting dynamics. In §§ 4 and 5,

![]() $\textit{St}$

is also varied in

$\textit{St}$

is also varied in

![]() $[0.01,1]$

to quantify its influence on interface evolution and force history. Particularly, only the force convection is investigated in §§ 3–5, while mixed-convection effects are addressed separately in § 6.

$[0.01,1]$

to quantify its influence on interface evolution and force history. Particularly, only the force convection is investigated in §§ 3–5, while mixed-convection effects are addressed separately in § 6.

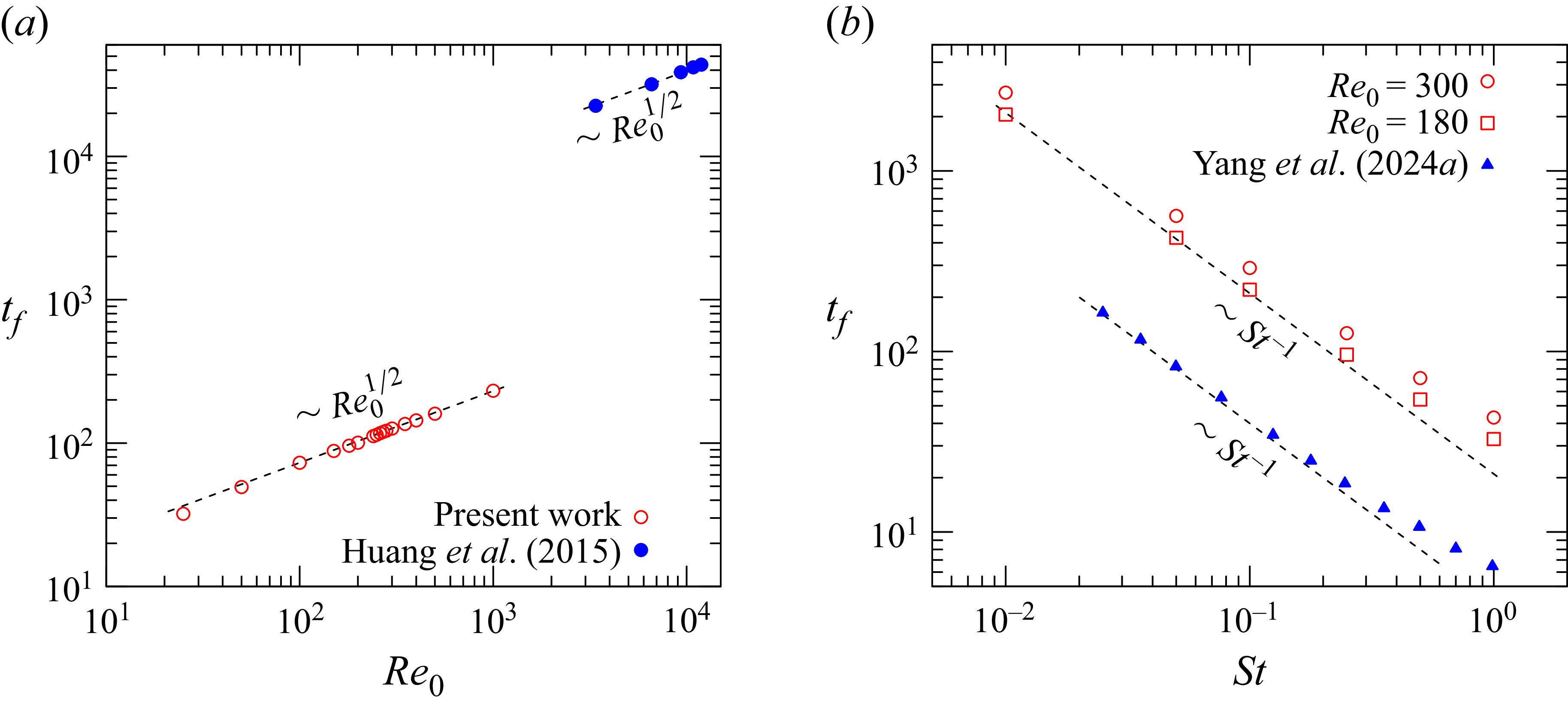

Figure 2. Parameter space

![]() $(\textit{Re}_0, \textit{St})$

explored in this study, with Prandtl number fixed at

$(\textit{Re}_0, \textit{St})$

explored in this study, with Prandtl number fixed at

![]() $Pr= 7$

. (a) Range of initial Reynolds numbers,

$Pr= 7$

. (a) Range of initial Reynolds numbers,

![]() $25\leqslant \textit{Re}_0\leqslant 1000$

, covering the canonical regimes for non-melting spheres: steady axisymmetric (

$25\leqslant \textit{Re}_0\leqslant 1000$

, covering the canonical regimes for non-melting spheres: steady axisymmetric (

![]() $\textit{Re}_0\lt 212$

), steady planar-symmetric (

$\textit{Re}_0\lt 212$

), steady planar-symmetric (

![]() $212\lt \textit{Re}_0\lt 273$

), periodic planar-symmetric (

$212\lt \textit{Re}_0\lt 273$

), periodic planar-symmetric (

![]() $273\lt \textit{Re}_0\lt 355$

) and chaotic (

$273\lt \textit{Re}_0\lt 355$

) and chaotic (

![]() $\textit{Re}_0\gt 355$

), with regime boundaries from Ern et al. (Reference Ern, Risso, Fabre and Magnaudet2012). (b) Representative snapshots of melting spheres and surrounding flow for each regime, coloured by local temperature. The open markers in (a) highlight corresponding visualisations.

$\textit{Re}_0\gt 355$

), with regime boundaries from Ern et al. (Reference Ern, Risso, Fabre and Magnaudet2012). (b) Representative snapshots of melting spheres and surrounding flow for each regime, coloured by local temperature. The open markers in (a) highlight corresponding visualisations.

An important consideration concerns the initial flow development. Viscous and thermal boundary layers require finite time to establish, and wake structures do not appear immediately after flow initiation. Since the present study focuses on the interaction between melting and fully developed wakes, the melting process is initially deactivated and is only activated once the flow field reaches a steady or quasi-steady state, following the approach of Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Howland, Liu, Verzicco and Lohse2024a ). This procedure avoids startup transients that might otherwise obscure the intrinsic coupling between convection and interface dynamics.

Due to the continuously evolving solid phase during melting, an important quantity is the time-dependent effective Reynolds number

![]() $\textit{Re}_e(t)=\textit{Re}_0 D_e(t)$

, defined using an effective diameter

$\textit{Re}_e(t)=\textit{Re}_0 D_e(t)$

, defined using an effective diameter

![]() $D_e(t)=2\sqrt {A_x(t)/\pi }$

calculated from the projected area in the projected cross-sectional area

$D_e(t)=2\sqrt {A_x(t)/\pi }$

calculated from the projected area in the projected cross-sectional area

![]() $A_x(t)$

in the incoming-flow (

$A_x(t)$

in the incoming-flow (

![]() $x$

) direction. This parameter more clearly identifies the dynamical state of the system and facilitates the hydrodynamic analysis presented in § 5.

$x$

) direction. This parameter more clearly identifies the dynamical state of the system and facilitates the hydrodynamic analysis presented in § 5.

The governing equations (2.1)–(2.3), together with the Stefan condition (2.5), are solved using a recently developed VOF–EB-based sharp-interface method (Xue et al. Reference Xue, Zhao, Ni and Zhang2023). The scheme employs an EB framework that resolves the liquid and solid phases separately, with the interface being tracked and reconstructed using a VOF technique, and the interfacial jump conditions imposed sharply at

![]() $\varGamma$

. The implementation is based on the open-source flow solver Basilisk (Popinet & Collaborators Reference Popinet2013–2024). Validation against laboratory measurements of melting ice spheres (Xue et al. Reference Xue, Zhao, Ni and Zhang2023) demonstrated that the method reproduces both melting rates and interfacial evolution with high fidelity.

$\varGamma$

. The implementation is based on the open-source flow solver Basilisk (Popinet & Collaborators Reference Popinet2013–2024). Validation against laboratory measurements of melting ice spheres (Xue et al. Reference Xue, Zhao, Ni and Zhang2023) demonstrated that the method reproduces both melting rates and interfacial evolution with high fidelity.

Computational efficiency is achieved via adaptive mesh refinement, which concentrates resolution near the melting interface, where viscous and thermal boundary layers form, and in regions of strong vorticity in the wake. In the present simulations, the finest mesh size is

![]() $\varDelta _{min }=D_0/204$

, ensuring at least seven grid points across both viscous and thermal boundary layers even at the highest initial Reynolds number (

$\varDelta _{min }=D_0/204$

, ensuring at least seven grid points across both viscous and thermal boundary layers even at the highest initial Reynolds number (

![]() $\textit{Re}_0=1000$

). Figure 3(a) illustrates the resulting grid distribution around the sphere and in the wake. Grid convergence is assessed for the case

$\textit{Re}_0=1000$

). Figure 3(a) illustrates the resulting grid distribution around the sphere and in the wake. Grid convergence is assessed for the case

![]() $(\textit{Re}_0,\textit{St},\textit{Pr},\textit{Ri})=(1000,0.25,7,0)$

. The normalised remaining solid volume

$(\textit{Re}_0,\textit{St},\textit{Pr},\textit{Ri})=(1000,0.25,7,0)$

. The normalised remaining solid volume

![]() $V(t)/V_0$

and solid–liquid interface at

$V(t)/V_0$

and solid–liquid interface at

![]() $t=40$

are compared across multiple resolutions in figure 3(b,c). The results show negligible difference between

$t=40$

are compared across multiple resolutions in figure 3(b,c). The results show negligible difference between

![]() $\varDelta _{min }=D_0/204$

and

$\varDelta _{min }=D_0/204$

and

![]() $D_0/102$

, confirming that the chosen resolution is sufficient to capture both interfacial and flow dynamics.

$D_0/102$

, confirming that the chosen resolution is sufficient to capture both interfacial and flow dynamics.

Figure 3. Grid refinement and numerical convergence for the case

![]() $(\textit{Re}_0,\textit{St},\textit{Pr},\textit{Ri})=(1000,0.25,7,0)$

. (a) Grid distribution on the mid-plane at

$(\textit{Re}_0,\textit{St},\textit{Pr},\textit{Ri})=(1000,0.25,7,0)$

. (a) Grid distribution on the mid-plane at

![]() $z=0$

at

$z=0$

at

![]() $t=30$

with

$t=30$

with

![]() $D_0/\varDelta _{{min}} = 204$

, where

$D_0/\varDelta _{{min}} = 204$

, where

![]() $\varDelta _{{min}}$

denotes the finest mesh size. (b) Time evolution of normalised remaining solid volume

$\varDelta _{{min}}$

denotes the finest mesh size. (b) Time evolution of normalised remaining solid volume

![]() $V(t)/V_0$

for varying spatial resolution

$V(t)/V_0$

for varying spatial resolution

![]() $D_0/\varDelta _{{min}}$

. (c) Solid–liquid interfaces on the mid-plane at

$D_0/\varDelta _{{min}}$

. (c) Solid–liquid interfaces on the mid-plane at

![]() $z=0$

at

$z=0$

at

![]() $t=60$

for varying spatial resolution

$t=60$

for varying spatial resolution

![]() $D_0/\varDelta _{{min}}$

. The legend applies to both panels.

$D_0/\varDelta _{{min}}$

. The legend applies to both panels.

3. Structures of melting interface and fluid flow

3.1. For

$\textit{Re}_0 \lt 212$

: axisymmetric melting regime

$\textit{Re}_0 \lt 212$

: axisymmetric melting regime

In the absence of melting, the wake behind a fixed sphere remains axisymmetric up to the first bifurcation at

![]() $\textit{Re}_{\textit{c1}}\approx 212$

(Johnson & Patel Reference Johnson and Patel1999; Ern et al. Reference Ern, Risso, Fabre and Magnaudet2012). For a melting sphere with

$\textit{Re}_{\textit{c1}}\approx 212$

(Johnson & Patel Reference Johnson and Patel1999; Ern et al. Reference Ern, Risso, Fabre and Magnaudet2012). For a melting sphere with

![]() $\textit{Re}_0\lt 212$

, both the interface and the surrounding flow are therefore expected to preserve axisymmetry throughout the evolution. This is confirmed in figure 4(a) for

$\textit{Re}_0\lt 212$

, both the interface and the surrounding flow are therefore expected to preserve axisymmetry throughout the evolution. This is confirmed in figure 4(a) for

![]() $\textit{Re}_0=180$

, which displays the temperature field, mid-plane streamlines and the 3-D interface coloured by

$\textit{Re}_0=180$

, which displays the temperature field, mid-plane streamlines and the 3-D interface coloured by

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

. At all times shown, i.e.

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

. At all times shown, i.e.

![]() $t/t_{\!f} = 0.010$

,

$t/t_{\!f} = 0.010$

,

![]() $0.412$

, and

$0.412$

, and

![]() $0.722$

with

$0.722$

with

![]() $t_{\!f}$

denoting the moment at which the solid vanishes, the wake exhibits a symmetric recirculation zone and the interfacial shape remains axisymmetric. On the upstream side,

$t_{\!f}$

denoting the moment at which the solid vanishes, the wake exhibits a symmetric recirculation zone and the interfacial shape remains axisymmetric. On the upstream side,

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

decreases monotonically with the polar angle

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

decreases monotonically with the polar angle

![]() $\varphi$

, as quantified in figure 4(b). This trend arises from boundary-layer development: starting from the stagnation point, the thermal boundary layer thickens with increasing arc length, thereby reducing the local heat flux. Since

$\varphi$

, as quantified in figure 4(b). This trend arises from boundary-layer development: starting from the stagnation point, the thermal boundary layer thickens with increasing arc length, thereby reducing the local heat flux. Since

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }} \propto \delta _\theta ^{-1}$

(equation (2.5)), the melting rate correspondingly decays with

$v_{{\varGamma }} \propto \delta _\theta ^{-1}$

(equation (2.5)), the melting rate correspondingly decays with

![]() $\varphi$

. By contrast, on the downstream side, flow separation isolates the rear surface from direct contact with the warmer inflow. The separated recirculation region traps relatively cold fluid, suppressing convective transport into the wake. As a result, the temperature gradient across the rear interface remains weak and

$\varphi$

. By contrast, on the downstream side, flow separation isolates the rear surface from direct contact with the warmer inflow. The separated recirculation region traps relatively cold fluid, suppressing convective transport into the wake. As a result, the temperature gradient across the rear interface remains weak and

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

exhibits an abrupt decline near the separation point, followed by persistently small values further downstream, as evident in figure 4(b).

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

exhibits an abrupt decline near the separation point, followed by persistently small values further downstream, as evident in figure 4(b).

Figure 4. Melting dynamics at

![]() $\textit{Re}_0=180$

. (a) Snapshots of the temperature field

$\textit{Re}_0=180$

. (a) Snapshots of the temperature field

![]() $\theta$

and streamlines on the mid-plane at

$\theta$

and streamlines on the mid-plane at

![]() $z=0$

, together with the 3-D melting interface coloured by the local melting rate

$z=0$

, together with the 3-D melting interface coloured by the local melting rate

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

, shown at

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

, shown at

![]() $t/t_{\!f} = 0.010,0.412,0.722$

(top to bottom). The corresponding effective Reynolds numbers

$t/t_{\!f} = 0.010,0.412,0.722$

(top to bottom). The corresponding effective Reynolds numbers

![]() $\textit{Re}_e(t)$

are indicated in each panel, and the same notation is used in the subsequent figures illustrating the melting process. (b) Angular distribution of

$\textit{Re}_e(t)$

are indicated in each panel, and the same notation is used in the subsequent figures illustrating the melting process. (b) Angular distribution of

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

along the interface as a function of the polar angle

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

along the interface as a function of the polar angle

![]() $\varphi$

, from

$\varphi$

, from

![]() $t/t_{\!f}=0.052$

to

$t/t_{\!f}=0.052$

to

![]() $0.845$

in increments of

$0.845$

in increments of

![]() $\Delta t/t_{\!f}=0.072$

. The inset at the lower left shows the polar angle

$\Delta t/t_{\!f}=0.072$

. The inset at the lower left shows the polar angle

![]() $\varphi$

; the origin is the body’s instantaneous mass centre

$\varphi$

; the origin is the body’s instantaneous mass centre

![]() $(x_c,0,0)$

, and

$(x_c,0,0)$

, and

![]() $\varphi$

is measured from the front stagnation point. The inset at the upper right shows the interface-averaged melting rate

$\varphi$

is measured from the front stagnation point. The inset at the upper right shows the interface-averaged melting rate

![]() $\bar {v}_{\varGamma }(t)$

as a function of the normalised remaining volume

$\bar {v}_{\varGamma }(t)$

as a function of the normalised remaining volume

![]() $V(t)/V_0$

, revealing a clear

$V(t)/V_0$

, revealing a clear

![]() $-1/6$

scaling.

$-1/6$

scaling.

As shown in figure 4(a), the front of the melting sphere approximately retains a spherical arc throughout the process, whereas the rear interface progressively flattens. This behaviour is consistent with previous experimental and numerical observations (Huang et al. Reference Huang, Jinzi, M.Nicholas and Ristroph2015; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Howland, Liu, Verzicco and Lohse2024a

; Hao & Tao Reference Hao and Tao2001), underscoring the close coupling between wake structure and rear-interface evolution. The flattening originates from the recirculating wake, which establishes a secondary stagnation point at the rear centre (

![]() $\varphi = \pi$

). At this location, the recirculating wake produces a local stagnation point where the thermal boundary layer reaches its minimum thickness, yielding the peak melting rate

$\varphi = \pi$

). At this location, the recirculating wake produces a local stagnation point where the thermal boundary layer reaches its minimum thickness, yielding the peak melting rate

![]() $v_{\varGamma }$

. This enhanced recession at

$v_{\varGamma }$

. This enhanced recession at

![]() $\varphi =\pi$

diminishes the rear curvature and drives the interface towards a planar shape. According to classical boundary-layer theory for axisymmetric stagnation-point flow (Schlichting & Gersten Reference Schlichting and Gersten2000, (5.70)), a planar rear interface leads to an almost uniform viscous boundary-layer thickness. At

$\varphi =\pi$

diminishes the rear curvature and drives the interface towards a planar shape. According to classical boundary-layer theory for axisymmetric stagnation-point flow (Schlichting & Gersten Reference Schlichting and Gersten2000, (5.70)), a planar rear interface leads to an almost uniform viscous boundary-layer thickness. At

![]() $\textit{Pr}=7$

, the thermal layer lies within the viscous one and obeys the same scaling, so its thickness is likewise nearly uniform. This, in turn, implies an approximately uniform melting rate along the entire rear surface. Hence, once the interface becomes nearly flat, the boundary-layer structure naturally enforces the spatial uniformity of

$\textit{Pr}=7$

, the thermal layer lies within the viscous one and obeys the same scaling, so its thickness is likewise nearly uniform. This, in turn, implies an approximately uniform melting rate along the entire rear surface. Hence, once the interface becomes nearly flat, the boundary-layer structure naturally enforces the spatial uniformity of

![]() $v_{\varGamma }$

at the rear interface observed later in figure 4(b) at

$v_{\varGamma }$

at the rear interface observed later in figure 4(b) at

![]() $t/t_{\!f}=0.845$

, stabilising the planar configuration. This tendency mirrors the self-similar retreating shapes documented for dissolving or eroding bodies in high-Reynolds-number flows (

$t/t_{\!f}=0.845$

, stabilising the planar configuration. This tendency mirrors the self-similar retreating shapes documented for dissolving or eroding bodies in high-Reynolds-number flows (

![]() $\textit{Re}\sim 10^4$

), where nearly uniform wall shear or solute concentration profiles control the late-stage morphology (Ristroph et al. Reference Ristroph, Moore, Childress, Shelley and Zhang2012; Moore et al. Reference Moore, Ristroph, Childress, Zhang and Shelley2013; Huang et al. Reference Huang, Jinzi, M.Nicholas and Ristroph2015). The present results thus suggest that similar boundary-layer mechanisms operate at the rear interface in the moderate-

$\textit{Re}\sim 10^4$

), where nearly uniform wall shear or solute concentration profiles control the late-stage morphology (Ristroph et al. Reference Ristroph, Moore, Childress, Shelley and Zhang2012; Moore et al. Reference Moore, Ristroph, Childress, Zhang and Shelley2013; Huang et al. Reference Huang, Jinzi, M.Nicholas and Ristroph2015). The present results thus suggest that similar boundary-layer mechanisms operate at the rear interface in the moderate-

![]() $\textit{Re}_0$

regime. Notably, as shown later in § 3.4, analogous uniformity also emerges at the front interface for high Reynolds number of

$\textit{Re}_0$

regime. Notably, as shown later in § 3.4, analogous uniformity also emerges at the front interface for high Reynolds number of

![]() $\textit{Re}_0=1000$

.

$\textit{Re}_0=1000$

.

In addition, figure 4(b) shows that the overall melting rate increases over time. This trend is further illustrated by the upper-right inset, which presents the interface-averaged melting rate as a function of the normalised remaining volume. The observed behaviour can be rationalised using classical boundary-layer scaling arguments (Johnson & Patel Reference Johnson and Patel1999; Schlichting & Gersten Reference Schlichting and Gersten2000; Huang et al. Reference Huang, Jinzi, M.Nicholas and Ristroph2015). For a shrinking body, the viscous boundary-layer thickness satisfies the scaling

![]() $\delta _u / V^{1/3} \sim (V^{1/3})^{-1/2}$

. Consequently, the interface-averaged melting rate scales as

$\delta _u / V^{1/3} \sim (V^{1/3})^{-1/2}$

. Consequently, the interface-averaged melting rate scales as

which agrees with the

![]() $-1/6$

scaling observed in the inset at the upper right of figure 4(b).

$-1/6$

scaling observed in the inset at the upper right of figure 4(b).

The influence of the initial Reynolds number

![]() $\textit{Re}_0$

on melting dynamics within the axisymmetric regime is illustrated in figure 5. For non-melting spheres, increasing

$\textit{Re}_0$

on melting dynamics within the axisymmetric regime is illustrated in figure 5. For non-melting spheres, increasing

![]() $\textit{Re}_0$

reduces the separation angle

$\textit{Re}_0$

reduces the separation angle

![]() $\varphi _s$

and enlarges the toroidal wake vortex (Johnson & Patel Reference Johnson and Patel1999). A comparable trend emerges in the melting problem: larger

$\varphi _s$

and enlarges the toroidal wake vortex (Johnson & Patel Reference Johnson and Patel1999). A comparable trend emerges in the melting problem: larger

![]() $\textit{Re}_0$

produces stronger wake recirculation, which progressively alters the rear-interface morphology. Figure 5(a–d) shows the mid-plane interface (

$\textit{Re}_0$

produces stronger wake recirculation, which progressively alters the rear-interface morphology. Figure 5(a–d) shows the mid-plane interface (

![]() $z=0$

) at successive times for different

$z=0$

) at successive times for different

![]() $\textit{Re}_0$

, with the local melting rate

$\textit{Re}_0$

, with the local melting rate

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

indicated by colour. To enable direct comparison, figure 5(e) superposes the interfaces at the moment when the solid volume has decreased to

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

indicated by colour. To enable direct comparison, figure 5(e) superposes the interfaces at the moment when the solid volume has decreased to

![]() $V(t)/V_0=0.1$

. At moderate Reynolds numbers (

$V(t)/V_0=0.1$

. At moderate Reynolds numbers (

![]() $\textit{Re}_0=25$

and

$\textit{Re}_0=25$

and

![]() $50$

), the bodies preserve an approximately ellipsoidal form throughout melting, and the rear interface remains convex. In contrast, at higher

$50$

), the bodies preserve an approximately ellipsoidal form throughout melting, and the rear interface remains convex. In contrast, at higher

![]() $\textit{Re}_0$

(

$\textit{Re}_0$

(

![]() $100 \lesssim \textit{Re}_0 \leqslant 200$

), the rear interface undergoes marked flattening, induced by stronger and more persistent recirculating wakes. This contrast stems from the reduced extent of separation at low-to-moderate

$100 \lesssim \textit{Re}_0 \leqslant 200$

), the rear interface undergoes marked flattening, induced by stronger and more persistent recirculating wakes. This contrast stems from the reduced extent of separation at low-to-moderate

![]() $\textit{Re}_0$

, where the separation angle remains large (

$\textit{Re}_0$

, where the separation angle remains large (

![]() $\varphi _s \approx 140^\circ$

for

$\varphi _s \approx 140^\circ$

for

![]() $\textit{Re}_0 \leqslant 50$

; Johnson & Patel Reference Johnson and Patel1999), and from the decrease in effective Reynolds number

$\textit{Re}_0 \leqslant 50$

; Johnson & Patel Reference Johnson and Patel1999), and from the decrease in effective Reynolds number

![]() $\textit{Re}_e$

as the body shrinks. A more quantitative description of these shape changes is provided in § 4, where aspect-ratio-based measures are introduced. The implications of interface morphology for global melting rates and hydrodynamic forces are analysed in §§ 4 and 5.

$\textit{Re}_e$

as the body shrinks. A more quantitative description of these shape changes is provided in § 4, where aspect-ratio-based measures are introduced. The implications of interface morphology for global melting rates and hydrodynamic forces are analysed in §§ 4 and 5.

Figure 5. Effect of the initial Reynolds number

![]() $\textit{Re}_0$

on interface evolution in the axisymmetric melting regime. (a–d) Time evolution of the interface on the mid-plane at

$\textit{Re}_0$

on interface evolution in the axisymmetric melting regime. (a–d) Time evolution of the interface on the mid-plane at

![]() $z=0$

for

$z=0$

for

![]() $\textit{Re}_0=25,\ 100,\ 150$

and

$\textit{Re}_0=25,\ 100,\ 150$

and

![]() $200$

, coloured by the local melting rate

$200$

, coloured by the local melting rate

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

. The sequences span nearly the entire melting process, with frames shown at uniform time intervals up to

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

. The sequences span nearly the entire melting process, with frames shown at uniform time intervals up to

![]() $t/t_{\!f} \approx 0.9$

. (e) Comparison of the interfaces on the mid-plane at

$t/t_{\!f} \approx 0.9$

. (e) Comparison of the interfaces on the mid-plane at

![]() $z=0$

when the remaining solid volume reaches

$z=0$

when the remaining solid volume reaches

![]() $V(t)/V_0=0.1$

, highlighting the progressive flattening of the rear surface as

$V(t)/V_0=0.1$

, highlighting the progressive flattening of the rear surface as

![]() $\textit{Re}_0$

increases.

$\textit{Re}_0$

increases.

3.2. For

$212 \lt \textit{Re}_0 \lt 273$

: steady planar-symmetric melting regime

$212 \lt \textit{Re}_0 \lt 273$

: steady planar-symmetric melting regime

For

![]() $\textit{Re}_0 \gt 212$

, the wake behind a translating sphere loses axisymmetry but retains a reflectional symmetry plane, up to the second bifurcation threshold at

$\textit{Re}_0 \gt 212$

, the wake behind a translating sphere loses axisymmetry but retains a reflectional symmetry plane, up to the second bifurcation threshold at

![]() $\textit{Re}_{\textit{c2}} \approx 273$

(Johnson & Patel Reference Johnson and Patel1999; Ern et al. Reference Ern, Risso, Fabre and Magnaudet2012). Within this steady planar-symmetric regime, we examine the case

$\textit{Re}_{\textit{c2}} \approx 273$

(Johnson & Patel Reference Johnson and Patel1999; Ern et al. Reference Ern, Risso, Fabre and Magnaudet2012). Within this steady planar-symmetric regime, we examine the case

![]() $\textit{Re}_0 = 270$

. Since the flow spontaneously selects a symmetry plane, rather than being imposed, we analyse it using a rotated coordinate system

$\textit{Re}_0 = 270$

. Since the flow spontaneously selects a symmetry plane, rather than being imposed, we analyse it using a rotated coordinate system

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $\eta$

–

$\eta$

–

![]() $ \zeta$

, where

$ \zeta$

, where

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $\eta$

defines the symmetry plane and

$\eta$

defines the symmetry plane and

![]() $\zeta$

is the transverse direction. Note that, in the present study, the symmetry plane is entirely determined by numerical noise. As a result, the rotated coordinate system

$\zeta$

is the transverse direction. Note that, in the present study, the symmetry plane is entirely determined by numerical noise. As a result, the rotated coordinate system

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $\eta$

–

$\eta$

–

![]() $\zeta$

used for the symmetry-breaking regimes throughout the paper is

$\zeta$

used for the symmetry-breaking regimes throughout the paper is

![]() $\textit{Re}_0$

–dependent. Figure 6(a) presents the 3-D streamlines in the vicinity of the sphere at

$\textit{Re}_0$

–dependent. Figure 6(a) presents the 3-D streamlines in the vicinity of the sphere at

![]() $t/t_{\!f} = 0.502$

, viewed along the

$t/t_{\!f} = 0.502$

, viewed along the

![]() $\zeta$

direction. The upstream fluid is first entrained by the lower spiral, then transported azimuthally towards the upper spiral and finally guided around the lower spiral before moving downstream. Figure 6(b) shows the 3-D isosurfaces of the streamwise vorticity

$\zeta$

direction. The upstream fluid is first entrained by the lower spiral, then transported azimuthally towards the upper spiral and finally guided around the lower spiral before moving downstream. Figure 6(b) shows the 3-D isosurfaces of the streamwise vorticity

![]() $\omega _x$

at the same instant, with red and blue surfaces representing

$\omega _x$

at the same instant, with red and blue surfaces representing

![]() $\omega _x = \pm 0.25$

. These illustrate the canonical features of the planar-symmetric wake: the recirculating vortex ring behind the sphere becomes tilted, with unequal upper and lower spirals, as illustrated in figure 6(c) where the snapshots of the melting body and wake are presented. The stronger spiral entrains fluid into the weaker one, thereby breaking the closed toroidal bubble of the axisymmetric melting regime. This imbalance generates a pair of counter-rotating streamwise vortices, which induce a transverse lift force in the

$\omega _x = \pm 0.25$

. These illustrate the canonical features of the planar-symmetric wake: the recirculating vortex ring behind the sphere becomes tilted, with unequal upper and lower spirals, as illustrated in figure 6(c) where the snapshots of the melting body and wake are presented. The stronger spiral entrains fluid into the weaker one, thereby breaking the closed toroidal bubble of the axisymmetric melting regime. This imbalance generates a pair of counter-rotating streamwise vortices, which induce a transverse lift force in the

![]() $\eta$

direction. Still in figure 6(c), the front interface remains rounded, while the rear evolves asymmetrically: the lower side melts faster, producing an inclined planar surface that ultimately stabilises at an angle of

$\eta$

direction. Still in figure 6(c), the front interface remains rounded, while the rear evolves asymmetrically: the lower side melts faster, producing an inclined planar surface that ultimately stabilises at an angle of

![]() $-9.2^\circ$

relative to the

$-9.2^\circ$

relative to the

![]() $\eta$

direction. This asymmetry arises because the upper spiral traps colder recirculated fluid, suppressing local melting, whereas the lower spiral is replenished by warmer inflow, enhancing melting. The rear stagnation point (red markers) shifts laterally during the evolution, initially located at negative

$\eta$

direction. This asymmetry arises because the upper spiral traps colder recirculated fluid, suppressing local melting, whereas the lower spiral is replenished by warmer inflow, enhancing melting. The rear stagnation point (red markers) shifts laterally during the evolution, initially located at negative

![]() $\eta$

(

$\eta$

(

![]() $\eta \lt 0$

or

$\eta \lt 0$

or

![]() $\varphi \gt \pi$

) but crossing into positive

$\varphi \gt \pi$

) but crossing into positive

![]() $\eta$

(

$\eta$

(

![]() $\eta \gt 0$

or

$\eta \gt 0$

or

![]() $\varphi \lt \pi$

) at late times of

$\varphi \lt \pi$

) at late times of

![]() $t/t_{\!f} = 0.920$

, accompanied by a reversal of spiral dominance, as highlighted in the magnified view. This reversal can be attributed to the inclination of the melting body: the streamline path connecting the front stagnation point to the rear is shorter in the lower half, resulting in stronger vortex formation on that side. Such a scenario is also consistent with vortex structures observed behind inclined non-melting bodies such as spheroids (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Yang, Andersson, Zhu, Liu, Wang and Lu2021b

) and cylinders (Kharrouba, Pierson & Magnaudet Reference Kharrouba, Pierson and Magnaudet2021). The implications of this spiral reversal for the lift force are examined in § 5.2.

$t/t_{\!f} = 0.920$

, accompanied by a reversal of spiral dominance, as highlighted in the magnified view. This reversal can be attributed to the inclination of the melting body: the streamline path connecting the front stagnation point to the rear is shorter in the lower half, resulting in stronger vortex formation on that side. Such a scenario is also consistent with vortex structures observed behind inclined non-melting bodies such as spheroids (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Yang, Andersson, Zhu, Liu, Wang and Lu2021b

) and cylinders (Kharrouba, Pierson & Magnaudet Reference Kharrouba, Pierson and Magnaudet2021). The implications of this spiral reversal for the lift force are examined in § 5.2.

Figure 6. Melting dynamics at

![]() $\textit{Re}_0=270$

in the steady planar-symmetric regime. (a) Three-dimensional streamlines viewed along the

$\textit{Re}_0=270$

in the steady planar-symmetric regime. (a) Three-dimensional streamlines viewed along the

![]() $\zeta$

direction. (b) Three-dimensional isosurfaces of the streamwise vorticity

$\zeta$

direction. (b) Three-dimensional isosurfaces of the streamwise vorticity

![]() $\omega _x$

viewed along the

$\omega _x$

viewed along the

![]() $\eta$

direction, with red and blue surfaces indicating

$\eta$

direction, with red and blue surfaces indicating

![]() $\omega _x=\pm 0.25$

. The results shown in (a,b) correspond to

$\omega _x=\pm 0.25$

. The results shown in (a,b) correspond to

![]() $t/t_{\!f} = 0.502$

, at which the effective Reynolds number is

$t/t_{\!f} = 0.502$

, at which the effective Reynolds number is

![]() $\textit{Re}_e(t)\approx 199.56$

. (c) Snapshots of the temperature field

$\textit{Re}_e(t)\approx 199.56$

. (c) Snapshots of the temperature field

![]() $\theta$

, streamlines on the symmetry plane (

$\theta$

, streamlines on the symmetry plane (

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $\eta$

) and the 3-D interface coloured by the local melting rate

$\eta$

) and the 3-D interface coloured by the local melting rate

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

, shown at

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

, shown at

![]() $t/t_{\!f}=0.008$

,

$t/t_{\!f}=0.008$

,

![]() $0.335$

,

$0.335$

,

![]() $0.669$

and

$0.669$

and

![]() $0.920$

. Red points mark the rear stagnation position, highlighting its lateral migration along the

$0.920$

. Red points mark the rear stagnation position, highlighting its lateral migration along the

![]() $\eta$

direction and eventual reversal of spiral dominance in the wake.

$\eta$

direction and eventual reversal of spiral dominance in the wake.

Figure 7 examines in detail the melting characteristics at

![]() $t/t_{\!f}=0.335$

for

$t/t_{\!f}=0.335$

for

![]() $\textit{Re}_0=270$

. Figure 7(a) displays the temperature field

$\textit{Re}_0=270$

. Figure 7(a) displays the temperature field

![]() $\theta$

and the local melting rate

$\theta$

and the local melting rate

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

in the reflectional symmetry plane (

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

in the reflectional symmetry plane (

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $\eta$

). A pronounced thermal asymmetry is observed: the lower spiral contains warmer fluid than the upper, consistent with the enhanced melting on the lower rear surface. The strongest melting occurs at the rear stagnation point, where the temperature gradient is steepest. This ‘melting kernel’ is highlighted in all panels by red circles. The rear-view distribution of

$\eta$

). A pronounced thermal asymmetry is observed: the lower spiral contains warmer fluid than the upper, consistent with the enhanced melting on the lower rear surface. The strongest melting occurs at the rear stagnation point, where the temperature gradient is steepest. This ‘melting kernel’ is highlighted in all panels by red circles. The rear-view distribution of

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

, shown in figure 7(b), further emphasises the asymmetry, with the lower hemisphere retreating more rapidly. Figure 7(c) shows the temporal evolution of

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

, shown in figure 7(b), further emphasises the asymmetry, with the lower hemisphere retreating more rapidly. Figure 7(c) shows the temporal evolution of

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

as a function of the polar angle

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

as a function of the polar angle

![]() $\varphi$

(defined in the inset of figure 7

a), from

$\varphi$

(defined in the inset of figure 7

a), from

![]() $t/t_{\!f}=0.084$

to

$t/t_{\!f}=0.084$

to

![]() $0.837$

at intervals of

$0.837$

at intervals of

![]() $\Delta t/t_{\!f}=0.084$

. The peak melting rate consistently coincides with the stagnation point, whose angular location gradually migrates towards larger

$\Delta t/t_{\!f}=0.084$

. The peak melting rate consistently coincides with the stagnation point, whose angular location gradually migrates towards larger

![]() $\eta$

with time, reflecting the evolving wake geometry we described in figure 6(b). In addition, the spatial variation of

$\eta$

with time, reflecting the evolving wake geometry we described in figure 6(b). In addition, the spatial variation of

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

across the rear interface becomes progressively smoother, reminiscent of the trend towards uniform boundary-layer-driven melting observed in the axisymmetric melting regime. This suggests that, even in the presence of reflectional asymmetry, the system dynamically reorganises to reduce rear-interface thermal gradients.

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

across the rear interface becomes progressively smoother, reminiscent of the trend towards uniform boundary-layer-driven melting observed in the axisymmetric melting regime. This suggests that, even in the presence of reflectional asymmetry, the system dynamically reorganises to reduce rear-interface thermal gradients.

Figure 7. Rear-interface melting characteristics at

![]() $\textit{Re}_0=270$

. (a) Temperature field

$\textit{Re}_0=270$

. (a) Temperature field

![]() $\theta$

and local melting rate

$\theta$

and local melting rate

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

on the symmetry plane (

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

on the symmetry plane (

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $\eta$

). (b) Distribution of

$\eta$

). (b) Distribution of

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

viewed from the rear (positive

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

viewed from the rear (positive

![]() $x$

axis). The results shown in (a,b) correspond to

$x$

axis). The results shown in (a,b) correspond to

![]() $t/t_{\!f} = 0.335$

, at which the effective Reynolds number is

$t/t_{\!f} = 0.335$

, at which the effective Reynolds number is

![]() $\textit{Re}_e(t)\approx 220.66$

. (c) Temporal evolution of

$\textit{Re}_e(t)\approx 220.66$

. (c) Temporal evolution of

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

as a function of the polar angle

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

as a function of the polar angle

![]() $\varphi$

, from

$\varphi$

, from

![]() $t/t_{\!f}=0.084$

to

$t/t_{\!f}=0.084$

to

![]() $0.837$

at constant time intervals. Red circles mark the rear stagnation point in all panels.

$0.837$

at constant time intervals. Red circles mark the rear stagnation point in all panels.

Figure 8 summarises the influence of the initial Reynolds number

![]() $\textit{Re}_0$

on the morphological evolution of the rear interface within the steady planar-symmetric melting regime, considering cases with

$\textit{Re}_0$

on the morphological evolution of the rear interface within the steady planar-symmetric melting regime, considering cases with

![]() $\textit{Re}_0 = 240$

,

$\textit{Re}_0 = 240$

,

![]() $250$

,

$250$

,

![]() $260$

and

$260$

and

![]() $270$

. As

$270$

. As

![]() $\textit{Re}_0$

increases, the wake asymmetry intensifies, producing progressively larger inclination angles of the rear interface relative to the

$\textit{Re}_0$

increases, the wake asymmetry intensifies, producing progressively larger inclination angles of the rear interface relative to the

![]() $x$

direction. This trend is illustrated in figure 8(a), which overlays the interfaces at a fixed volume fraction

$x$

direction. This trend is illustrated in figure 8(a), which overlays the interfaces at a fixed volume fraction

![]() $V(t)/V_0=0.1$

. While the front hemispheres collapse onto nearly identical spherical arcs, the diverging rear interfaces clearly demonstrate the increasing anisotropy of wake-induced melting at higher Reynolds numbers. To quantify this inclination, we define the rear-interface angle as

$V(t)/V_0=0.1$

. While the front hemispheres collapse onto nearly identical spherical arcs, the diverging rear interfaces clearly demonstrate the increasing anisotropy of wake-induced melting at higher Reynolds numbers. To quantify this inclination, we define the rear-interface angle as

![]() $\textrm{tan}^{-1}(\textrm{sgn}(\bar {n}_\eta )\sqrt {\bar {n}^2_\eta +\bar {n}^2_\zeta }/|\bar {n}_x|)$

, where

$\textrm{tan}^{-1}(\textrm{sgn}(\bar {n}_\eta )\sqrt {\bar {n}^2_\eta +\bar {n}^2_\zeta }/|\bar {n}_x|)$

, where

![]() $(\bar {n}_x,\bar {n}_\eta ,\bar {n}_\zeta )$

are the components of the area-averaged outward normal vector

$(\bar {n}_x,\bar {n}_\eta ,\bar {n}_\zeta )$

are the components of the area-averaged outward normal vector

![]() $\bar {\boldsymbol{n}}$

on the rear interface. The time evolution of the rear-interface angle, shown in figure 8(b), confirms this trend: the inclination increases from about

$\bar {\boldsymbol{n}}$

on the rear interface. The time evolution of the rear-interface angle, shown in figure 8(b), confirms this trend: the inclination increases from about

![]() $-6.2^\circ$

at

$-6.2^\circ$

at

![]() $\textit{Re}_0=240$

to

$\textit{Re}_0=240$

to

![]() $-9.2^\circ$

at

$-9.2^\circ$

at

![]() $\textit{Re}_0=270$

. At late stages (

$\textit{Re}_0=270$

. At late stages (

![]() $t/t_{\!f} \gt 0.8$

), the inclination saturates, consistent with the nearly uniform rear melting rates observed earlier (see figure 7

c).

$t/t_{\!f} \gt 0.8$

), the inclination saturates, consistent with the nearly uniform rear melting rates observed earlier (see figure 7

c).

Figure 8. Influence of

![]() $\textit{Re}_0$

on rear-interface evolution in the steady planar-symmetric melting regime. (a) Comparison of interfaces on the symmetry plane (

$\textit{Re}_0$

on rear-interface evolution in the steady planar-symmetric melting regime. (a) Comparison of interfaces on the symmetry plane (

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $\eta$

) when the remaining solid volume reaches

$\eta$

) when the remaining solid volume reaches

![]() $V(t)/V_0=0.1$

. (b) Time evolution of the inclination angle of the rear interface relative to the

$V(t)/V_0=0.1$

. (b) Time evolution of the inclination angle of the rear interface relative to the

![]() $x$

axis for different

$x$

axis for different

![]() $\textit{Re}_0$

. Increasing

$\textit{Re}_0$

. Increasing

![]() $\textit{Re}_0$

enhances the inclination of the rear interface.

$\textit{Re}_0$

enhances the inclination of the rear interface.

3.3. For

$273 \lt \textit{Re}_0 \lt 355$

: periodic planar-symmetric melting regime

$273 \lt \textit{Re}_0 \lt 355$

: periodic planar-symmetric melting regime

When the Reynolds number surpasses the second critical threshold,

![]() $\textit{Re}_{\textit{c2}} \approx 273$

, the wake undergoes a Hopf bifurcation, transitioning from steady to unsteady behaviour. The resulting flow exhibits time-periodic vortex shedding while retaining planar reflectional symmetry (Johnson & Patel Reference Johnson and Patel1999). In this regime, the wake generates oscillatory lift forces with a non-zero mean, yet the vortex separation line remains nearly fixed and the rear stagnation point fluctuates only weakly within

$\textit{Re}_{\textit{c2}} \approx 273$

, the wake undergoes a Hopf bifurcation, transitioning from steady to unsteady behaviour. The resulting flow exhibits time-periodic vortex shedding while retaining planar reflectional symmetry (Johnson & Patel Reference Johnson and Patel1999). In this regime, the wake generates oscillatory lift forces with a non-zero mean, yet the vortex separation line remains nearly fixed and the rear stagnation point fluctuates only weakly within

![]() $\pm 9^\circ$

(Johnson & Patel Reference Johnson and Patel1999). Thus, despite the periodic shedding, the rear stagnation point is effectively quasi-stationary.

$\pm 9^\circ$

(Johnson & Patel Reference Johnson and Patel1999). Thus, despite the periodic shedding, the rear stagnation point is effectively quasi-stationary.

Accordingly, we anticipate that once melting commences, the rear interface will continue to evolve into a planar and inclined surface, in close analogy with the behaviour observed in the steady planar-symmetric melting regime (§ 3.2). This expectation is confirmed in figure 9(a), which presents representative snapshots of the streamline topology and temperature field

![]() $\theta$

on the symmetry plane (

$\theta$

on the symmetry plane (

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $\eta$

) for

$\eta$

) for

![]() $\textit{Re}_0 = 300$

, together with the 3-D interface coloured by the local melting rate

$\textit{Re}_0 = 300$

, together with the 3-D interface coloured by the local melting rate

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

, over the interval

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

, over the interval

![]() $0 \lt t/t_{\!f} \lt 0.910$

. Once melting is activated, the rear interface begins to incline, and the wake gradually loses its temporal periodicity, reorganising into a new steady asymmetric configuration. By

$0 \lt t/t_{\!f} \lt 0.910$

. Once melting is activated, the rear interface begins to incline, and the wake gradually loses its temporal periodicity, reorganising into a new steady asymmetric configuration. By

![]() $t/t_{\!f} = 0.910$

, the lower spiral has become larger than the upper, a reversal analogous to that observed in the steady planar-symmetric melting regime (§ 3.2). The temporal development of this melting-induced transition is further illustrated in figure 9(b), which shows that a tilted and nearly planar rear interface persists in the later stage. The dynamical suppression of wake periodicity is quantified in figure 9(c), where the time histories of the polar angle of the rear stagnation point are plotted. These quantities initially exhibit small oscillations, consistent with the underlying unsteady wake. As melting progresses, the effective Reynolds number

$t/t_{\!f} = 0.910$

, the lower spiral has become larger than the upper, a reversal analogous to that observed in the steady planar-symmetric melting regime (§ 3.2). The temporal development of this melting-induced transition is further illustrated in figure 9(b), which shows that a tilted and nearly planar rear interface persists in the later stage. The dynamical suppression of wake periodicity is quantified in figure 9(c), where the time histories of the polar angle of the rear stagnation point are plotted. These quantities initially exhibit small oscillations, consistent with the underlying unsteady wake. As melting progresses, the effective Reynolds number

![]() $\textit{Re}_e(t)$

decreases, leading to a decay of these oscillations and a monotonic shift towards smaller

$\textit{Re}_e(t)$

decreases, leading to a decay of these oscillations and a monotonic shift towards smaller

![]() $\varphi$

values, corresponding to the positive

$\varphi$

values, corresponding to the positive

![]() $\eta$

direction. This behaviour demonstrates that interfacial evolution suppresses vortex shedding and re-establishes a quasi-steady wake morphology.

$\eta$

direction. This behaviour demonstrates that interfacial evolution suppresses vortex shedding and re-establishes a quasi-steady wake morphology.

Figure 9. Melting processes of

![]() $\textit{Re}_0=300$

in the periodic planar-symmetric melting regime. (a) Snapshots of the temperature field

$\textit{Re}_0=300$

in the periodic planar-symmetric melting regime. (a) Snapshots of the temperature field

![]() $\theta$

and streamline at the symmetry plane (

$\theta$

and streamline at the symmetry plane (

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $\eta$

) and 3-D interface coloured by the melting rate

$\eta$

) and 3-D interface coloured by the melting rate

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

at

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

at

![]() $t=1,40,80,115$

(

$t=1,40,80,115$

(

![]() $t/t_{\!f}=0.008,0.317,0.633,0.910$

), from top to bottom. The red points indicate the rear stagnation points at each moment. (b) Time evolution of the interface coloured by the melting rate

$t/t_{\!f}=0.008,0.317,0.633,0.910$

), from top to bottom. The red points indicate the rear stagnation points at each moment. (b) Time evolution of the interface coloured by the melting rate

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

at the reflectional symmetry plane (

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

at the reflectional symmetry plane (

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $\eta$

) from

$\eta$

) from

![]() $t=0$

to

$t=0$

to

![]() $t=110$

(

$t=110$

(

![]() $t/t_{\!f}=0.871$

) with a constant time interval of

$t/t_{\!f}=0.871$

) with a constant time interval of

![]() $\Delta t=10$

(

$\Delta t=10$

(

![]() $\Delta t/t_{\!f}=0.079$

). (c) Time evolution of polar angle of the rear stagnation point, where the dynamical suppression of wake periodicity is observed as the effective Reynolds number

$\Delta t/t_{\!f}=0.079$

). (c) Time evolution of polar angle of the rear stagnation point, where the dynamical suppression of wake periodicity is observed as the effective Reynolds number

![]() $\textit{Re}_e(t)$

decreases.

$\textit{Re}_e(t)$

decreases.

Figure 10 presents a phase-resolved view of the melting dynamics during a single oscillation cycle in the early stage of melting. Four characteristic phases are selected within one shedding period,

![]() $\psi = 0$

,

$\psi = 0$

,

![]() $\pi /2$

,

$\pi /2$

,

![]() $\pi$

and

$\pi$

and

![]() $3\pi /2$

, corresponding to

$3\pi /2$

, corresponding to

![]() $t = 64.1$

,

$t = 64.1$

,

![]() $65.5$

,

$65.5$

,

![]() $66.9$

and

$66.9$

and

![]() $68.3$

(

$68.3$

(

![]() $t/t_{\!f} = 0.507, 0.519, 0.530, 0.540$

). Figure 10(a) shows the temperature field and streamlines on the symmetry plane (

$t/t_{\!f} = 0.507, 0.519, 0.530, 0.540$

). Figure 10(a) shows the temperature field and streamlines on the symmetry plane (

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $\eta$

), together with the interface coloured by

$\eta$

), together with the interface coloured by

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

. While the global wake remains quasi-steady, small periodic modulations are evident, reflecting the influence of vortex shedding on local convective transport. Figure 10(b) illustrates the rear-face distribution of

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

. While the global wake remains quasi-steady, small periodic modulations are evident, reflecting the influence of vortex shedding on local convective transport. Figure 10(b) illustrates the rear-face distribution of

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

, which exhibits clear phase-dependent variations: the peak melting rate oscillates in synchronisation with the shedding cycle. This behaviour arises from periodic changes in the thickness of the thermal boundary layer at the rear stagnation zone, which governs local heat flux. Figure 10(c) confirms this interpretation by showing the polar distribution of

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

, which exhibits clear phase-dependent variations: the peak melting rate oscillates in synchronisation with the shedding cycle. This behaviour arises from periodic changes in the thickness of the thermal boundary layer at the rear stagnation zone, which governs local heat flux. Figure 10(c) confirms this interpretation by showing the polar distribution of

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

on the symmetry plane (

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

on the symmetry plane (

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $\eta$

). At

$\eta$

). At

![]() $\psi = 0$

(

$\psi = 0$

(

![]() $t=64.1$

), the lower spiral is in the process of detachment, which weakens convective transport near the rear surface and reduces the melting rate. In contrast, at

$t=64.1$

), the lower spiral is in the process of detachment, which weakens convective transport near the rear surface and reduces the melting rate. In contrast, at

![]() $\psi = \pi$

(

$\psi = \pi$

(

![]() $t=66.9$

), the lower spiral is replenished by inflow and remains attached to the surface, intensifying local convection and enhancing the melting rate.

$t=66.9$

), the lower spiral is replenished by inflow and remains attached to the surface, intensifying local convection and enhancing the melting rate.

Figure 10. Phase-resolved melting dynamics during one oscillation cycle at

![]() $\textit{Re}_0=300$

. Four phases are shown,

$\textit{Re}_0=300$

. Four phases are shown,

![]() $\psi = 0, \pi /2, \pi , 3\pi /2$

, corresponding to

$\psi = 0, \pi /2, \pi , 3\pi /2$

, corresponding to

![]() $t = 64.1, 65.5, 66.9, 68.3$

(

$t = 64.1, 65.5, 66.9, 68.3$

(

![]() $t/t_{\!f}=0.507, 0.519, 0.530, 0.540$

). During this interval, the effective Reynolds number

$t/t_{\!f}=0.507, 0.519, 0.530, 0.540$

). During this interval, the effective Reynolds number

![]() $\textit{Re}_e(t)$

decreases from about

$\textit{Re}_e(t)$

decreases from about

![]() $194.36$

to

$194.36$

to

![]() $189.02$

. (a) Temperature field

$189.02$

. (a) Temperature field

![]() $\theta$

and streamlines on the symmetry plane (

$\theta$

and streamlines on the symmetry plane (

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $\eta$

), together with the 3-D interface coloured by the local melting rate

$\eta$

), together with the 3-D interface coloured by the local melting rate

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

. (b) Distribution of

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

. (b) Distribution of

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

on the rear face of the solid, viewed from the rear. (c) Polar distribution of

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

on the rear face of the solid, viewed from the rear. (c) Polar distribution of

![]() $v_{{\varGamma }}$

at the symmetry plane (

$v_{{\varGamma }}$

at the symmetry plane (

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $\eta$

) for the four phases, where the inset defines the polar angle

$\eta$

) for the four phases, where the inset defines the polar angle

![]() $\varphi$

for this regime. Red points denote the rear stagnation point in all panels.