Introduction

Once considered too remote and inaccessible, the Arctic Ocean is rapidly emerging as a new frontier for oil extraction. While early development focused on reserves on land and in shallow coastal waters (Casper, Reference Casper2009), the retreat of ice (Figure 1) and the development of new technologies have enabled a shift toward deeper offshore fields (Bock, Reference Bock, Berkman and Vylegzhanin2013). This shift has triggered the emergence of new discourses around oil extraction in the melting Arctic: as we approach a climate tipping point, oil interests are sustained, and the melting itself is reframed through discourse as an economic opportunity.

Figure 1. Elaborated by the authors. Historic Arctic Sea Ice Extent in September, the month of maximum ice melt. The dates correspond to 1997 (Kyoto Protocol), 2015 (Paris Agreement), and 2024 (near present date). The dotted line marks the Arctic Circle at 66°33'N. Variations in the whiteness of the ice layers indicate changes in ice thickness. Prepared using data from NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center (2024).

A discourse is the way a topic or situation is interpreted, expressed, and presented in the public sphere (Jensen, Reference Jensen2007). Discourses shape what questions are asked, what knowledge is produced, and what policies are implemented (O’Brien, Eriksen, Nygaard, & Schjolden, Reference O’Brien, Eriksen, Nygaard and Schjolden2007). In contexts where industrial activities involve both losses and benefits, governments, activists, and communities act strategically, shaping discourses according to their interests (Fraser, Reference Fraser2010; Lakoff, Reference Lakoff2002). This strategic interplay is especially evident in the Arctic waters, where a mix of national and international interests comes into play (Young, Reference Young2024). In this region, oil interests clash with scientific warnings and international demands for climate action, creating a scenario of dispute between discourses. The discourse that comes to dominate—the hegemonic discourse—shapes whether the impact of an industry is perceived as beneficial or harmful in such sensitive regions (Corell, Reference Corell2006). In the case of the Arctic, the absence of societal consensus, the irreconcilability of interests, and the presence of various powerful stakeholders have resulted in an absence of hegemonic discourse. This makes the study of discourses and their supporters still relevant in the Arctic.

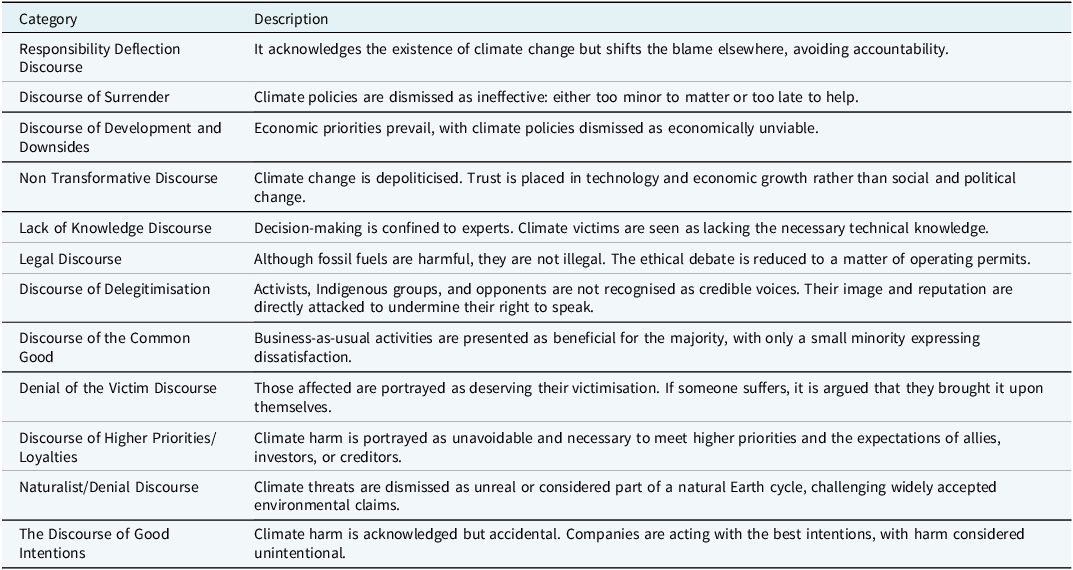

This work studies the Norwegian government’s alignment with discourses that favour the oil industry and its interests. These discourses, known as climate change obstruction (CCO) discourses, prioritise economic ambitions despite climate concerns. Their categories are summarised in Table 1, based on the typologies found in the literature (Bond, Thomas, & Diprose, Reference Bond, Thomas and Diprose2023; Chu, Zhu, & Ji, Reference Chu, Zhu and Ji2023; Lamb et al., Reference Lamb, Mattioli, Levi, Roberts, Capstick, Creutzig, Minx, Müller-Hansen, Culhane and Steinberger2020; McKie, Reference McKie2019). CCO discourses share four primary objectives: (1) ensuring the continued accumulation of capital and maintaining the fossil-fuel economy’s status quo (Newell, Daley, Mikheeva, & Peša, Reference Newell, Daley, Mikheeva and Peša2023); (2) downplaying the scientific consensus on climate change while promoting the supposed benefits of increased CO2 emissions (Ekberg, Forchtner, Hultman, & Jylhä, Reference Ekberg, Forchtner, Hultman and Jylhä2023); (3) hindering the implementation of climate policies by emphasising their perceived negative implications (McKie, Reference McKie2023); and (4) creating a cultural cognition, that is, unconscious ideologies and value systems so deeply ingrained in the population’s identity that they render individuals resistant to scientific reason and evidence (Schmelzer & Büttner, Reference Schmelzer and Büttner2024). The study of CCO discourses helps us understand why populations, politicians, and entire nations can frame oil extraction as a sustainable activity, even when scientific evidence shows that fossil fuel dependence leads humanity to a social, ecological and climate catastrophe. CCO discourses, like any other discourse, are not static but evolve in relation to their circumstances (Machin & Mayr, Reference Machin and Mayr2023; Fairclough, Reference Fairclough1995). Put differently: as science generates new findings, fossil-fuel actors respond with new counter-narratives, creating a dynamic interplay (Herranen, Reference Herranen2023). Scientists can weaken a discourse (e.g., climate denial) but, in response, fossil-fuel actors produce new discourses that combine with pre-existing ones to justify the fossil-fuel status quo (Shrivastava, Kasuga & Grant, Reference Shrivastava, Kasuga and Grant2023). This complex dynamic, together with the fact that not all CCO discourses are explicit (Eaton & Day, Reference Eaton and Day2020), creates the need to study them.

Table 1. Types of climate change obstruction discourses. (Compiled from the works of Bond, Thomas, & Diprose, Reference Bond, Thomas and Diprose2023; Chu, Zhu, & Ji, Reference Chu, Zhu and Ji2023; Lamb et al., Reference Lamb, Mattioli, Levi, Roberts, Capstick, Creutzig, Minx, Müller-Hansen, Culhane and Steinberger2020; McKie, Reference McKie2019)

This analysis focuses on Norway, given its status as the leading oil producer in Europe. Also, Norway is known as the gateway to the Arctic (Leroux & Spiro, Reference Leroux and Spiro2018), given its accessible and less harsh Arctic waters, which provide an ideal testing ground for new fossil fuel extraction technologies. Furthermore, it has recently played a significant role through its position as Chair of the Arctic Council (2023–2025). Previous research has highlighted the alarming prevalence of CCO discourses within the Norwegian oil industry (Ihlen, Reference Ihlen2006; Kangasluoma, Reference Kangasluoma2020). Moreover, within the Norwegian government, there has been frequent use of CCO non-transformative discourses (Eckersley, Reference Eckersley2016; Nordø, Andersen & Merk, Reference Nordø, Andersen and Merk2023) and of Common Good CCO discourses (Eckersley, Reference Eckersley2013; Bang & Lahn, Reference Bang and Lahn2020). The first, are based on a techno-optimistic belief that carbon capture and storage alone can solve the climate crisis without ending oil production; the second, frames oil as welfare (education, pensions, funding etc.) and never frames it as a threat. This study advances the debate by examining the presence of these and other CCO discourses within the Norwegian government. Through an inductive analysis of 653 pages from four official white papers, the study investigates how the Arctic petrostate frames its oil extraction. Accordingly, we ask whether the Norwegian government’s discourse aligns with CCO discourses, and we hypothesise that, despite robust scientific evidence, state authorities frame Arctic oil extraction as sustainable, prioritising economic development over climate urgency.

From denialism to obstruction: post-denial CC discourses

When it comes to climate change, social consensus lags behind scientific findings. This means that scientific statements are not immediately accepted but must instead traverse a long and tortuous path before being heard. Put differently, throughout its history, climate science has faced numerous discourses designed to delegitimise its findings (Farrell, McConnell, & Brulle, Reference Farrell, McConnell and Brulle2019a,b). The classic and perhaps best-known example is the Climate Denial discourse, which frames climate change as a hoax (Malm, Reference Malm2020). This discourse could be seen in the “ExxonKnew” scandal: in 1968, scientists at ExxonMobil accurately and skillfully predicted global warming (Anderson, Kasper, & Pomerantz, Reference Anderson, Kasper and Pomerantz2017); yet, despite possessing such knowledge, the company spent decades denying climate change (Supran, Rahmstorf, Oreskes, Reference Supran, Rahmstorf and Oreskes2023).

Beyond denial, however, climate science faces today a broader set of discourses (See Table 1). Formally, these are known as discourses of CCO, and are defined as ideological, economic, and political arguments produced by structures, institutions, and organisational actors with the purpose of impeding an effective global response to climate change (McKie, Reference McKie2023). CCO discourses include denialism but are not limited to it. CCO discourses pursue four main objectives: preserving the fossil-fuel economy’s status quo (Newell et al., Reference Newell, Daley, Mikheeva and Peša2023); undermining the scientific consensus while reframing global warming as advantageous (Ekberg et al., Reference Ekberg, Forchtner, Hultman and Jylhä2023); obstructing effective climate policies through emphasis on uncertainty (McKie, Reference McKie2023); and shaping ideologies that make societies resistant to scientific reasoning (Schmelzer & Büttner, Reference Schmelzer and Büttner2024).

The origins of CCO discourses as a broader concept can be traced back to 1988, when the scientific community reached a stronger consensus on both the existence of the climate problem and its anthropogenic causes (Ekberg et al., Reference Ekberg, Forchtner, Hultman and Jylhä2023). That year, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was founded (Bolin, Reference Bolin2007), and NASA scientist James Hansen testified before the U.S. Congress that climate change was already measurable (Weart, Reference Weart2011). In response to this consensus, the climate denial discourse evolved into more complex and diversified CCO forms: the use of experts to defend fossil-fuel interests increased, and a new line of argument emerged suggesting that, even if climate change was real, addressing it would be far too costly (Franta, Reference Franta2022). Thus, the late 1980s marked the emergence of a market logic in which experts argued against climate action based on economic priorities (Carton, Reference Carton2019). These years were also shaped by the naturalism discourse: in 1989, the Marshall Institute presented a paper to the White House, which did not deny climate change but attributed it solely to solar variability (Oreskes & Conway, Reference Oreskes and Conway2022; Roberts, Reference Roberts1989). One year later, the IPCC refuted this on its first report, affirming that the main driver was not the sun but the unrestricted use of fossil fuels (IPCC, Reference Houghton, Jenkins and Ephraums1990).

During the rest of the 1990s, a discourse of confusion and uncertainty was also consolidated (Ekberg et al., Reference Ekberg, Forchtner, Hultman and Jylhä2023). Here, scientific gaps were not addressed with a genuine desire to understand but were exploited as convenient excuses to maintain business as usual: this obstruction discourse sought to take advantage of scientific gaps while doing nothing to fill them. Additionally, by the late 1990s, a Consumer-blame discourse was trending. This apolitical strategy reframed the climate problem as a matter of individual consumption choices: “plant a tree, ride a bike, or recycle a jar in the hope of saving the world” (Huber, Reference Huber2012; Maniates, Reference Maniates2001, p.42). Later, the years 2000–2010 saw the rise of techno-optimism (Peeters, Higham, Kutzner, Cohen & Gössling, Reference Peeters, Higham, Kutzner, Cohen and Gössling2016). This CCO discourse placed excessive faith in technology as the solution to the climate problem, while sidelining decisions, funding, and policies. It also portrayed oil as part of the solution, as new technologies promised cleaner fossil fuels and sustainable oil extraction (Kangasluoma, Reference Kangasluoma2020; Sheehan, Reference Sheehan and Rimmer2018).

Between 2010 and 2020, and despite the Paris Agreement entering into force, CCO discourses evolved to exploit legal loopholes and incorporate them into their narrative: fossil-fuel dependence could be harmful but not strictly illegal. (McKie, Reference McKie2019; Rimmer, Reference Rimmer2018). At the same time, following the rise of the far right in the US (Goldman et al., Reference Goldman, Berman, Halpern, Johnson, Kothari, Reed and Rosenberg2017), new variants emerged in the late 2010s based on ad hominem attacks: climate change victims—those on the frontlines—were framed as responsible for their own suffering, and their knowledge was discredited (Bond, Thomas, & Diprose, Reference Bond, Thomas and Diprose2023). From 2020 onwards, all these discourses have become entangled: each of them, as well as their combinations, has created an entire repertoire of counter-narratives against climate science efforts. (Lamb et al., Reference Lamb, Mattioli, Levi, Roberts, Capstick, Creutzig, Minx, Müller-Hansen, Culhane and Steinberger2020). Now, according to the context, the variety of CCO discourses coexist and interact, without one replacing the other.

In sum, CCO discourses are not static but evolve in relation to their circumstances (Machin & Mayr, Reference Machin and Mayr2023; Fairclough, Reference Fairclough1995). Thus, as science generates new findings, fossil-fuel actors respond with new counter-narratives, creating a dynamic interplay (Herranen, Reference Herranen2023). Scientists can weaken a discourse (e.g., climate denial) but, in response, fossil-fuel actors produce new discourses that combine with pre-existing ones to justify the fossil-fuel status quo (Shrivastava, Kasuga & Grant, Reference Shrivastava, Kasuga and Grant2023). This complex dynamic, together with the fact that not all CCO discourses are explicit (Eaton & Day, Reference Eaton and Day2020), creates the need for special methods to study them.

Norway’s petro-climate paradox

Norway stands at a crossroads: the largest oil producer in Europe is, at the same time, a country with one of the most ambitious climate goals in the world (Eckersley, Reference Eckersley2013). This creates a tension where oil is not only portrayed as a threat but also as welfare: “It is not just oil and gas being extracted from the bottom of the sea: it is health care, education, pensions, child care, research funding and jobs.” (Bang & Lahn, Reference Bang and Lahn2020, p.6)

Norway’s response to its petro-climate paradox has drawn the attention of several scholars. Kristoffersen (Reference Kristoffersen, O’Brien and Selboe2015) argues that since 1990, climate agreements have been soft on oil producers, allowing petrostates like Norway to expand oil production while outsourcing emission reductions. Specifically, and since the Kyoto Protocol, there has been an excessive focus on consumption-side responsibility, exempting petrostates from accountability (Ballo, Kristoffersen & Sidortsov, Reference Ballo, Kristoffersen and Sidortsov2024). In the long-term, this blame on consumption creates an “opportunistic adaptation” to the climate issue (Kristoffersen, Reference Kristoffersen, O’Brien and Selboe2015, p.2), where the responsibility for climate change can be reframed to benefit oil producers. This provides countries like Norway with a way to reconcile their paradox: petrostates are held accountable for domestic emissions but not for the millions of barrels they extract and export, making them appear climate-friendly. This also explains how other Arctic nations could claim to be climate leaders while framing ice melting as an opportunity for a more “workable Arctic” (Dale & Kristoffersen, Reference Dale and Kristoffersen2018, p.3). Yet, opportunistic adaptation extends even further, taking advantage not only of climate issues but also of the poverty of other countries, reframing their vulnerabilities in a discourse where oil production in the high north is a benevolent act towards the south: “When the world needs more energy to fight poverty, it is not morally wrong that Norway is helping to supply that energy, that oil and gas.” (Alstadheim, Reference Alstadheim2010, p.71). As if that were not enough, this opportunism can also capitalise on wars. Before the war in Ukraine, Norway justified its oil interests through cooperation with Russia, its good neighbour (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2012). After the war, it reframed its oil interests as necessary for European energy security: an act of liberation from evil Russia (Ballo, Kristoffersen & Sidortsov, Reference Ballo, Kristoffersen and Sidortsov2024).

Such discursive flexibility raises questions about the persistence of Norway’s long-term oil interests in a rapidly changing world. In any case, the opportunistic adaptation remains problematic because, as Finland’s President said, “opportunism will eventually be forced to confront the problems it tried to ignore” (Stubb, Reference Stubb2025, 10:13–10:20).

That said, Norway’s hope of being a “front-runner country” in climate change—as it proposed in 1992—is far from reality. Drawing on official documents, Bang and Lahn (Reference Bang and Lahn2020) demonstrate that Norway has increased oil permits from 2013–2018, resulting in a considerable expansion of the oil industry. Furthermore, there is a strong multipartisan consensus to continue oil expansion (Harrison & Bang, Reference Harrison and Bang2022). Worse still, the resistance to phasing out oil is not limited to political parties: most citizens, bureaucrats, and journalists also support the continuation of oil production, preferring techno-optimistic discourses that promise to solve climate change without significant reforms (Nordø et al., Reference Nordø, Andersen and Merk2023). Consequently, Norwegian policies have positioned the country not as a climate leader but as a helper—specifically, a bridge between major emitters and the most vulnerable nations. (Carvalho & Neumann, Reference Carvalho and Neumann2016). This role—this in between—allows Norway to maintain a climate-friendly face while promoting the idea that its oil equals welfare: one that “can be pursued relatively independent of other states” (Eckersley, Reference Eckersley2016, p.2).

In sum, Norway is self-portrayed as a champion of climate change mitigation (Le Billon & Kristoffersen, Reference Le Billon and Kristoffersen2020), but despite decades of ambitious climate goals, its power relationships, institutional structures, and belief systems remain largely unchanged. Ultimately, this dynamic provides fertile ground for the emergence of CCO, as they seem necessary for Norway to project a climate-friendly image without questioning its oil expansion.

Theoretical framework

This work adopts constructivism as its epistemological foundation. Constructivism suggests that how we interpret scientific findings is as important as the findings themselves (Robbins, Reference Robbins2012). Constructivism holds that science is influenced by social values (Blue & Brierley, Reference Blue and Brierley2016) because science depends on the cultural, historical, and financial support provided by the society in which it exists. Additionally, the existence of a linguistic and social framework is a prerequisite for scientific endeavours (Heidegger, Reference Heidegger, Stambaugh and Schmidt2010), meaning that science emerges from society to influence it and, society, in turn, shapes scientific findings in a continuous dialogue of mutual influence (Figure 2). Based on the above, this study adopts Foucault’s work as a theoretical framework to analyse CCO discourses. According to Foucault, power and knowledge are closely interconnected, and together they shape what society comes to accept as truth (Foucault, Reference Foucault1982). In other words, societal truths are not just discovered but constructed through the interplay of power and knowledge. For instance, scientific findings can be factually correct—such as the urgency of climate change—but fail to be accepted as societal truth if they challenge powerful interests. In such cases, the discourse of science could be overshadowed or replaced by alternative discourses that align better with the existing dynamics of power.

Figure 2. Elaborated by the authors. Simplified representation of the epistemological framework used in this article, emphasising the mutual influence between science and society.

In sum, the choice of constructivism as epistemology and Foucault’s ideas as theoretical framework is based on the fact that, despite overwhelming scientific evidence, parallel discourses on climate change persist: ones shaped by specific social norms and modes of production, that challenge scientific findings, frame oil extraction as sustainable, delay meaningful action, evade accountability, and ultimately undermine the urgency of addressing the climate crisis.

Material and methods

Material

The primary data source consists of four official Arctic white papers published by the Norwegian government, retrieved from their official platform (www.regjeringen.no). The following documents were selected for their relevance to Norway’s Arctic policies:

-

Norway’s Climate Action Plan for 2021–2030 (Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2021)

-

Norway’s Integrated Ocean Management Plans (Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2020)

-

Long-Term Plan for Research and Higher Education 2023–2032 (Ministry of Education and Research, 2022)

-

The High North: Visions and Strategies (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2012).

Methods

This research employs a qualitative approach using inductive data analysis, inspired by the work of Ihlen (Reference Ihlen2006) and that of Glaser and Strauss (Reference Glaser and Strauss1999). In this method, the analyst continuously refines the data to maintain the relevance of the information gathered. The steps are as follows:

Data decomposition

First reading and section extraction: The selected white papers are read in full. Sections relevant to oil extraction or climate change are extracted and compiled into a separate document for a second review.

Second review and unit creation: The new document is thoroughly reviewed, and is segmented into paragraphs or sentences (units). Each unit represents an idea related to oil interests and/or climate change.

Identification of patterns: The units are compared; patterns and recurring concepts are identified. During this phase, the researcher avoids imposing pre-conceived categories, allowing content similarities to guide the analysis.

Data reorganisation

Group into codes: The units are grouped into broader categories (codes) according to the patterns identified between the units.

Refining codes: The codes undergo an iterative refinement process, moving back and forth between the raw data to assess their validity. This ensures they faithfully capture the narratives present in the white papers.

Group into themes: A second round of grouping occurs as the refined codes are organised into broader categories (themes) based on the patterns identified among the codes.

Framing creation: The final themes are analysed, and a corresponding framing is developed for each theme to explain how the issue is being constructed, confirming the narrative construction process.

Findings

Oil-related themes

Theme: The future of oil & gas in Norway

Framing: Norway positions itself as a long-term supplier of oil and gas. Continued fossil fuel production is justified as essential for national economic stability, employment, and the financing of the welfare state. While climate commitments and energy transition are acknowledged, they are framed as not contradictory to ongoing oil exploration and extraction. Oil is framed as necessary until the end of the century. The government is presented as an enabler of profitable production,

Codes // Units within each code:

-

– The Hydrocarbon Industry as a Long-Term Player // 15

Theme: Legitimising mechanisms for future oil and gas extraction.

Framing: Positions oil and gas extraction as a key component of the green transition, framing the petroleum industry expertise as necessary for renewable energy projects. Environmental stewardship is emphasised through strict adherence to safety and ecological standards, presenting fossil fuel activities as compatible with environmental protection. Spill preparedness is framed as Norway’s ability to mitigate risks of oil production in the Arctic. The oil industry is portrayed as a reliable actor in environmental protection

Code // Units within each code:

-

– Expertise of the Petroleum Industry as Necessary for the Green Transition // 13

-

– Petroleum Industry as Harmonisable with Health, Environmental, and Safety // 7

-

– Oil Spill Preparedness as a Legitimator of Oil Production in the Arctic // 2

-

– The Petroleum Industry as Creator of Value, Welfare, and Employment // 1

-

– Value creation as a priority for Norway // 3

Theme: Oil & Gas expansion

Framing: Portrays oil production as an active and ongoing endeavour, with the Norwegian government supporting exploration, development, and production in Arctic waters.

Codes // Units within each code:

-

– Expansion of Oil & Gas Activities as a Government Interest // 6

Theme: Petroleum and Renewables Coexistence

Framing: Frames the petroleum industry as compatible with renewable energy. Green energy is framed harmoniously with continued oil expansion. Renewable energy offshore permits are framed as the responsibility of the Ministry of Petroleum.

Codes // Units within each code:

-

– The Hydrocarbon Industry as Compatible with Renewable Energy // 7

-

– Renewable Energy Licenses as a Responsibility of the Ministry of Petroleum // 1

Theme: Emissions Reduction in the Petroleum Industry

Framing: The reduction of emissions in the oil industry is framed as a critical component of Norway’s broader climate and energy policy, emphasising the electrification of the industry. The framing highlights the role of the oil industry in contributing to emission reductions through government-industry collaboration, policy instruments, and research initiatives. No reduction in oil production is ever proposed, as the focus remains exclusively on minimising emissions from oil production processes rather than limiting oil output.

Codes // Units within each code:

-

– Low-Emission Petroleum Production as a Priority // 17

-

– Energy Efficiency as a Path to Emissions Reduction // 4

-

– Expertise as a Path to Emissions Reduction // 1

-

– Technology Innovation as a Path to Emissions Reduction // 4

Theme: Norway’s Status in the Arctic

Framing: Presents Norway’s Arctic governance as integral to its identity as a polar nation with a strong presence in the region. This framing emphasises the importance of maintaining geopolitical influence and active participation in Arctic resources. Norway frames its oil ambitions as part of its role in regional cooperation and governance, framing Arctic resource exploitation as a strategic and responsible choice.

Codes // Units within each code:

-

– Norway as a country with a Strong presence in the Arctic // 4

-

– Norway as a Polar Nation // 2

Theme: Opportunities due to the Arctic Melting

Framing: Frames the Arctic melting as an economic opportunity. The narrative highlights oil and gas development as the most prominent opportunity, alongside potential benefits from new shipping routes, mining, and expanded fisheries. This framing shifts the focus from environmental loss to economic gain, presenting the Arctic’s transformation as a chance for strategic advantage and resource expansion.

Codes // Units within each code:

-

– Arctic melting as an Opportunity for Oil & gas // 6

-

– Arctic melting as an Opportunity for Shipping routes, Minerals and/or Other resources // 4

-

– Arctic melting as an Overall Economic Opportunity // 6

Theme: Norway’s oil interests and war in Ukraine

Framing: Before the war in Ukraine, oil is framed as a mechanism of cooperation with Russia. Oil production in the Arctic, particularly in the southern Barents Sea, is framed as beneficial for both nations. The collaboration with Russia, grounded in resolving maritime disputes under UNCLOS, is portrayed as a gateway to new opportunities for resource exploration.

Codes // Units within each code:

-

– Russia as an ally for Arctic Resource Exploitation // 7

Theme: The Knowledge Ambivalence

Framing: Presents knowledge and research as dual-purpose tools supporting both petroleum expansion and the green transition. Positioned as essential for hydrocarbon activities, Arctic exploration, and energy shifts, knowledge underpins both agendas without fully aligning with either. It is framed as a cornerstone for addressing climate change while enabling resource extraction, emphasising its shared role rather than favouring one side of the climate–oil dichotomy. Knowledge gaps are also highlighted as key challenges in both oil activities and climate action.

Codes // Units within each code:

-

– Research and knowledge as Essential for both Climate Action and Resource Extraction // 2

-

– Knowledge as Essential for Hydrocarbon Activities // 2

-

– Knowledge as Essential for Energy Transition // 2

Climate-related themes and frames

Theme: Climate Urgency

Framing: Climate change is framed as an urgent and escalating global crisis, with particular emphasis on the Arctic as a highly vulnerable region. The narrative highlights key impacts—such as shrinking snow and ice cover, permafrost thaw, and disruptions to ocean circulation—drawing on scientific research to underscore the severity of these changes. Arctic melting is portrayed not only as rapid but also carrying underestimated global consequences, reinforcing a sense of urgency and intensifying concern over time.

Codes // Units within each code:

-

– Climate Change as an Urgent Problem // 17

-

– The Arctic as Profoundly Affected by Climate Change // 6

-

– Climate Change as a Previously Underestimated Crisis // 2

-

– Climate Change as a Worsening Problem // 3

Theme: Climate Action and Mitigation strategies

Framing: Norway’s climate mitigation strategy emphasises carbon taxation, wind power development, carbon storage, and forest conservation. The framing highlights proactive efforts in these areas while avoiding commitments to reduce oil and gas production. It frames climate action as economically advantageous, emphasising that the benefits of meeting climate targets outweigh the costs of inaction. Delayed adaptation is framed as more costly than taking timely measures.

Codes // Units within each code:

-

– Taxation as a Mechanism for Emissions Reduction // 10

-

– Wind Power as a Mechanism for Emissions Reduction // 9

-

– Implementing climate action as an economic benefit // 3

-

– Wind Power as a Mechanism for Emissions Reduction // 1

-

– Carbon Storage as a Mechanism for Emissions Reduction // 3

-

– Emissions reduction without compromising economic growth // 3

-

– Forest initiatives as a Mitigation Strategy // 3

Theme: Climate Targets and NDC Goals

Framing: Norway frames its climate targets as a demonstration of global leadership, positioning its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) as a key part of its commitment to international climate obligations. The government emphasises its goals of reducing emissions by 55 percent by 2030 and transitioning to a low-emission society by 2050, framing these ambitions as aligned with the global two-degree Celsius target.

Codes // Units within each code:

-

– Emission Reduction Targets as a Priority // 6

-

– The Two Degrees Celsius Target as a Priority // 1

Theme: Causes of Climate Change

Framing: Climate change is framed as a direct consequence of human activity, with overpopulation, overconsumption, and greenhouse gas emissions identified as key drivers. This narrative emphasises the need to confront these root causes in order to effectively address the crisis and reduce its impacts.

Codes // Units within each code:

-

– Greenhouse Gases as Cause of Climate Change // 2

-

– Short-lived Pollutants as Cause of Climate Change // 1

-

– Over Consumption as Cause of Climate Change // 1

-

– Population Growth as Cause of Climate Change // 1

Theme: The Public Sector and Fair Energy Transition

Framing: It frames the public sector as central to advancing green solutions and fulfilling climate objectives, highlighting its active role in driving change. The Norwegian government frames the energy transition as not only green but also fair and democratic, presenting these principles as fundamental to achieving the climate goals.

Codes // Units within each code:

-

– Fairness and Democracy as Part of the Energy Transition // 6

-

– The Public Sector as a Driver of the Energy Transition // 7

Theme: Climate Change Adaptation

Framing: Climate change adaptation is framed as a key priority in Norway’s domestic and international agenda, emphasising proactive measures to address impacts. It links local efforts in energy, agriculture, and land use with Arctic-wide strategies. It frames adaptation as essential for resilience and sustainability, and emphasises the economic benefits of early climate action.

Codes // Units within each code:

-

– Arctic Council and Climate Change adaptation // 3

-

– Strategies for Climate Change Adaptation // 2

Theme: Cooperation and Climate Leadership

Framing: Norway is portrayed as a climate leader through strong governance and international cooperation, leveraging its abundant natural resources to assume a leadership role.

Codes // Units within each code:

-

– Cooperation and Norway’s as leader in climate action // 3

-

– Norway, with its abundant resources, as a global climate leader // 4

Theme: Local vs. External Responsibility for Emissions

Framing: Greenhouse gas emissions are framed through a dual lens, with the Arctic portrayed either as a victim of external emissions or as a contributor of emissions through industrial activities in the zone.

Codes // Units within each code:

-

– Climate Change as a Local Responsibility // 1

-

– Climate Change as an External Responsibility // 1

Discussion

Non-transformative discourse: Norway and the fossil fuel solutionism

Norway’s discourse aligns with a non-transformative CCO discourse. This discourse does not deny the existence of climate change but obstructs meaningful climate action by deferring it (climate delay). The goal of this discourse is to prolong the operational lifespan of the oil industry, thereby hindering the structural transformation of the energy sector that is needed. For instance, Norway never proposes a gradual reduction of oil and gas production and, instead, long-term oil production is consistently highlighted as an objective across its four white papers. The following units from the documents illustrate the pattern:

“The main goal of the Government’s petroleum policy is to facilitate long-term profitable production of oil and gas” (Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2020, p. 96).

“The overall objective of Norway’s petroleum policy is to provide a framework for profitable long-term production of oil and gas” (Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2021, p. 179).

“The Norwegian continental shelf will be a stable long-term supplier of oil and gas to Europe during an extremely demanding time” (Ministry of Education and Research, 2022, p. 11).

“Although achieving rapid reductions in global emissions of greenhouse gases is an overriding goal, fossil fuels will continue to be needed far into this century” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2012, p. 35).

From 2011 to 2022, this discourse was consistently maintained, and the narrative remained unchanged even after the Paris Agreement entered into force in 2016. Moreover, Norway reinforces its non-transformative discourse with a narrative of fossil fuel solutionism: the assertion that the fossil fuel industry is part of the solution to the climate crisis. First, all the examined documents defend a harmonious coexistence between the petroleum industry and the green energy industry. Second, they underscore the role of oil production in supporting the green transition, highlighting that the expertise and knowledge of the oil industry are essential for renewable energy projects. This suggests that such expertise is directly transferable, although there are significant differences between the two sectors.

Despite the fundamental incompatibility between petroleum interests and meaningful climate action, Norway’s non-transformative CCO discourse enables the simultaneous pursuit of both, as if no trade-off were required. In other words, this discourse systematically downplays the profound contradictions inherent in expanding fossil fuel production while claiming to advance climate objectives. It likewise overlooks other structural tensions, such as the conflict between a nation’s right to exploit its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and the rights of future generations to inherit a livable planet. When two legitimate yet opposing rights come into conflict, a power struggle inevitably arises. However, these struggles and contradictions are precisely what Norway’s non-transformative discourse allows to evade, thereby sustaining the illusion that fossil fuel expansion and climate action can coexist without any conflict. This non-transformative CCO discourse becomes very evident when Norway frames the melting of the Arctic as an opportunity for resource exploitation:

“Reduced ice cover will improve conditions for shipping and give easier access to natural resources, which in turn may lay the foundation for new industrial activities.” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2012, p.36)

“The Government will facilitate the sound utilisation of the oil and gas resources in the High North.” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2012, p.27)

“The continental shelves in the Arctic are believed to be the world’s largest unexplored areas with significant petroleum potential.” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2012, p. 118)

“Growing shortages of oil and minerals are resulting in rising prices, and the High North is becoming more accessible as the extent of the sea ice shrinks.” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2012, p.98)

Responsibility deflection discourse: exporting oil as exporting the problem

Norway seeks to reduce domestic emissions from oil extraction while simultaneously expanding oil production. By emphasising emission reductions during oil production, the country justifies its oil expansion without formally breaching its climate commitments. However, this reflects a discourse of responsibility deflection, as Norway accounts only for the emissions generated during extraction, while ignoring those released when the oil is ultimately burned. Exported the oil, exported the problem. Rather than consider oil’s entire life cycle, Norway limits its responsibility to the emissions generated within its territory, conveniently ignoring what happens once the oil is exported. In this approach, most parts of the life cycle of fossil fuels are omitted (see Figure 3). This omission, however, is more than just a technical oversight: it’s a discourse that narrows the focus to the domestic sphere, where the problem appears more manageable and less visible than on the global stage. Domesticating is literally taking something wild (dangerous) and turning it into something domestic (harmless). Thus, domestication of the climate change narrative is what Norway is doing. To support a net-zero oil production, Norway subordinates renewable energy to the oil industry; that is, renewables are deployed not to replace or compete with oil, but to electrify the drilling and thus legitimise the oil industry expansion. In this green oil discourse, renewable technologies are framed as tools to sustain, rather than challenge, fossil fuel interests. For instance, offshore licenses for renewable energy fall under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy:

Figure 3. Elaborated by the authors. The image depicts the oil and gas life cycle, highlighting how Norway focuses exclusively on the domestic segment of the process while overlooking the broader stages of the oil and gas cycle.

“License applications for offshore renewable energy production are dealt with under the Offshore Energy Act, which is the responsibility of the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy.” (Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2020, p. 128)

The nonsense of climate-friendly oil production becomes evident when considering the very purpose of oil production. Crude oil is not extracted to stay in barrels: it’s produced to be burned, that is, to release energy and emissions with it. By focusing exclusively on domestic production emissions, Norway draws an imaginary line that conveniently separates it from its responsibility as Europe’s leading oil exporter. Thus, this narrative ultimately serves as a deflection of responsibility. Yet, once oil is released from its millennia-old underground reservoir, the combustion—and consequent transformation into greenhouse gases—is inevitable. Where it is burned becomes irrelevant, since all countries share the same atmosphere. Placing responsibility on importing countries under the “polluter pays” principle, or attributing an increase in oil production due to global demand, does not constitute meaningful climate action. In sum, renewables are used to power oil drilling, and the resulting green barrels are exported (they, however, remain distinctly Norwegian, much like citizens who retain their nationality regardless of where they go).

The legal discourse and the discourse of good intentions: Norwegian environmental stewardship

In every white paper, the concept of environmental management emerges. At first glance, these measures appear to be climate-friendly, driven by good intentions. However, this façade quickly unravels upon closer examination. The underlying objective of this approach is to create a framework that supports resource exploitation and provides stability for the oil and gas industry. In this context, Norway’s environmental management serves as a mechanism to legitimise the continued extraction of oil—a large-scale greenwashing effort. The nation’s Integrated Ocean Management Plans articulate this goal clearly:

“The management plans provide a good basis for sound resource management and a predictable regulatory framework for the oil and gas industry” (Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2020, p. 145).

The narrative subtly implies that the inherent contradictions between oil expansion and the urgency of climate action can be resolved through robust environmental restrictions and management within the oil industry. This framing shifts the focus away from reducing oil dependency to managing how oil is extracted. For instance, one of the papers highlights:

“The purpose of such restrictions is to avoid the risk of environmental damage (…) while still allowing petroleum activities to be carried out.” (Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2020, p.95)

This example underscores how the environmental management approach seeks to legitimise continued oil production by constructing a narrative in which the climate impacts of fossil fuels remain largely unquestioned. By aligning environmental management with the expansion of petroleum activities, Norway’s strategy does not constitute an effective response to climate change. Instead, it reframes the crisis as an issue of permits and compliance, reflecting elements of a CCO discourse known as the legal discourse. Such discourses are not intended to limit oil production, but to secure its continuation under the guise of environmental permissions and regulations.

However, the so-called Environmental Stewardship presented in these documents reveals a critical flaw: it narrows its focus to domestic strategies and ignores the global implications of the oil cycle. By confining its scope within Norway’s borders, this approach fails again to acknowledge the inherently global nature of climate change, which demands not just localised environmental action but a comprehensive reduction and eventual replacement of fossil fuels. For instance, measures such as Oil Spill Preparedness illustrate a narrow framing of the issue: one that treats oil production as unproblematic as long as spills and local environmental impacts are managed. This logic extends even to one of Norway’s most progressive regulations, which states:

“No new petroleum activities will be initiated in areas where sea ice is found on 15% of the days in April” (Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2020, p. 147)

This regulation appears to signify a strong commitment to protecting the Arctic. However, its effectiveness erodes alongside the retreating ice. As sea ice continues to melt, what initially seems like a protective measure transforms into a flexible restriction, allowing petroleum activities to expand as previously inaccessible areas become viable. Rather than serving as a robust safeguard, this measure functions as an open door: the oil industry just needs to wait patiently to exploit vulnerable regions as the ice disappears. Among other things, there is a question of whether this restriction is simply a way to reduce costs: extracting oil is not very profitable because of the ice, and so the environmental restriction may be just an economic obstacle.

Nevertheless, it is important to emphasise that the issue does not stem from environmental regulations or legal frameworks per se—these are both essential and beneficial. Rather, it lies in the reduction of climate action to compliance with legal requirements. While environmental management may be well-intentioned, it is ultimately insufficient to address the scale and urgency of the climate crisis.

In sum, petroleum activities are framed as environmentally well-intentioned and aligned with health, safety, and environmental standards. This framing constitutes a CCO discourse, as it obscures the broader issue: the focus should not be on improving extraction and management methods, but on reducing—and ultimately eliminating—fossil fuel dependence.

Discourse of the common good and discourse of higher priorities

A cornerstone of the Norwegian government is the Petroleum Fund, established in 1990. Funded by revenues from oil and gas, it has become the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund (Moses, Reference Moses, Pereira, Spencer and Moses2021), stabilising the economy and sustaining Norway’s welfare system through market fluctuations. In essence, the entire Norwegian welfare state is built on petroleum royalties. While this system has undoubtedly benefited its citizens, under the lens of climate change, the Petroleum Fund transforms from an asset to a potential burden. Norway would not only need to adopt new energy technologies but also undertake a profound restructuring of its political and welfare systems. This is no small task, as the state is deeply intertwined with discourses that present fossil fuels as the irreplaceable foundation of well-being and poverty alleviation.

This narrative is evident in the four official documents, where oil is consistently portrayed as a cornerstone of job creation and the common good. There is no indication that Norway plans to shift its welfare model away from oil dependency; on the contrary, all white papers analysed project that oil will continue to play a major role in financing the Norwegian welfare society. Linking oil production to the welfare state constitutes a CCO discourse because extraction activities are framed as beneficial to the majority. Moreover, halting oil production is presented as a threat to fundamental livelihoods and living standards. However, as the other two CCO identified, this narrative only makes sense by narrowing the problem to a domestic perspective: the welfare it promises is meaningful only within Norway’s borders. What constitutes prosperity for Norwegian citizens translates into adversity for other nations. This line of reasoning ultimately backfires. Future generations of Norwegians will also face the escalating impacts of climate change, undermining the very welfare that the white papers claim to protect. This reveals a deep contradiction in the common good discourse, which focuses exclusively on domestic short-term benefits while ignoring global long-term consequences.

Additionally, when it comes to value creation, this is elevated as a primary objective, often overshadowing the urgency of addressing climate change. Thus, climate priorities appear to take a back seat to the economic interests associated with petroleum. This reveals a profound conflict of interest: Norway is caught between its international climate commitments and its identity as a petrostate. In sum, the narrative ties together ideas of efficiency, productivity, growth, and development, which, along with welfare, paint a picture of oil extraction as not only economically necessary but also socially beneficial. The message is straightforward: oil extraction, under the label of value creation, will expand and will be carried out as profitably as possible.

Excluded climate change obstruction discourses

Since Norway acknowledges the climate problem, some CCO discourses are not present in its narrative. Firstly, Norway does not engage in climate change denial. This form of discourse involves rejecting the existence of global warming, its anthropogenic causes, or the severity of its impacts. In contrast, Norway recognises the reality of climate change, its human-driven origins, and the urgency of addressing its impacts. This foundational acknowledgment distances it from denialist discourses and aligns it firmly with the scientific findings.

Furthermore, there is no indication of climate misinformation, which involves the deliberate misrepresentation or omission of scientific data to erode trust in climate science or institutions. Climate misinformation’s common tactics include the selective use of data (cherry-picking) and the promotion of misleading narratives about renewable energy’s feasibility. In contrast, the Norwegian government affirms the scientific legitimacy of the IPCC and demonstrates a detailed understanding of climate change—its causes, effects, and the commitments required to address it. This reflects Norway’s trust in science and its findings, which distances Norway from the misinformation discourses. Norway also promotes mechanisms that safeguard scientific integrity, ensuring that research remains free from external interference. For example, one of the papers showed how the Ministry of Education and Research established an expert committee to protect science integrity (Ministry of Education and Research, 2022). This initiative, known as the Kierulf Committee, underscores the nation’s trust in science.

Norway does not present either a discourse of surrender, which frames climate action as futile, as efforts are too small to make a difference, or that it is already too late to act. Such fatalistic narratives, found in other political and public arenas, paralyse progress by fostering apathy and disengagement. This involves leveraging the overwhelming scale of global climate challenges as justification for inaction. The Norwegian government, by contrast, rejects fatalism and recognises the importance of early climate action.

Similarly, there is no evidence of a lack of knowledge discourse, which portrays stakeholders—whether policymakers, civil society, or activists—as uninformed or incapable of engaging with climate debates. This type of discourse is used to marginalise voices, particularly those of Indigenous communities, by framing their knowledge systems as insufficiently scientific. The Norwegian government takes the opposite stance, explicitly supporting democratic-inclusive participation and recognising the value of collaboration across all societal levels in tackling climate challenges.

On the other hand, Norway does not present a discourse of delegitimisation, where opposing voices are discredited through personal attacks rather than logical arguments. No evidence of such behaviour is found in the evaluated documents, which remain focused on logical, argument-based discussions without resorting to personal attacks.

Finally, the white papers show no characteristics of the denial of the victim discourse, where those affected by climate change are portrayed as deserving their plight. This narrative suggests that victims brought their suffering upon themselves, thereby shifting blame and avoiding accountability. The Norwegian white papers demonstrate no alignment with this form of discourse, and the framings underscore a commitment to equity and justice in addressing climate change.

Conclusion

This study arose from the question of whether the Norwegian government, through its white papers, aligns with CCO discourses. On the one hand, it was shown that the Norwegian Government exhibits affinity with six CCO discourses: 1) Non-Transformative Discourse, 2) Responsibility Deflection Discourse, 3) Discourse of the Common good, 4) Discourse of Higher Priorities or Loyalties, 5) The Legal Discourse, and 6) The Discourse of Good Intentions. On the other hand, it was shown that the Norwegian Government does not present elements of: Climate denial, Misinformation, Surrender, Lack of knowledge, Denial of the victim, or Delegitimisation. These findings are consistent with Norway’s difficult and contradictory position, as the country stands between climate urgency and a welfare model deeply rooted in oil revenues. Yet, instead of acknowledging these contradictions, it has been shown that significant efforts are made to reconcile the urgency of climate change and the expansion of oil production in the Arctic. This forced harmony is crafted through various mechanisms, including the expertise of the oil industry, environmental regulations, and the common good approach. These mechanisms, among others, are presented as evidence of climate leadership; however, they do not address the root cause of climate change—fossil fuel dependence—and instead overfocus on mitigating the immediate effects of oil operations (e.g., preparedness for oil spills). Furthermore, it was demonstrated that the Government promotes the concept of zero-carbon oil extraction, which aims to reduce domestic emissions while simultaneously supporting oil expansion in the Arctic Ocean. This concept is fundamentally flawed, as the emissions saved during extraction are outweighed by those generated through the industry’s expansion and increased oil consumption (see Figure 4). In sum, this approach results in a worse carbon emission than before. The strategy identified in the papers to obscure this and other contradictions was the use of a narrowed scope of accountability, focusing solely on domestic impacts during oil and gas production while ignoring the global effects associated with oil industry expansion and increased oil consumption. Similarly, it was evidenced that the government failed to consider the full life cycle of oil, omitting significant stages from refining to final combustion. This omission downplayed the fossil industry’s impact and allowed Norway to claim climate leadership despite its oil interests. The analysis also found no intention to change existing political structures to reduce oil production; instead, oil expansion remained a long-term government priority throughout all the white papers. No policies were identified to reduce state oil dependency; instead, there is a solid defence of increasing oil production through renewable energies and electrification of the oil industry. As the white papers involve various ministries, it is concluded that petroleum interests influence multiple branches of government, extending beyond the Ministry of Petroleum to encompass the Ministry of Climate and Environment, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Ministry of Education and Research. Similarly, this work demonstrated that the goal of long-term oil production remained constant from 2011 to 2022, showing no shifts despite Norway’s latest climate agreements and escalating scientific warnings.

Figure 4. Elaborated by the authors. The image illustrates the Norwegian ‘green oil’ strategy, which appears sustainable when focusing solely on the production phase but ultimately is a climate backfire when considering the overall emissions produced.

In sum, this study showed that Norway adopts a role of a passive respondent to external market forces, rather than positioning itself as an active leader in climate policy. Taken together, these findings suggest that Norway maintains a business-as-usual approach, in which renewable energy serves more as a complement to oil extraction than as a genuine step toward a fossil fuel phase-out.

This analysis predicts that, due to their official nature, the evaluated white papers are likely to influence future policies favouring oil expansion in the Arctic Ocean. Consequently, while acknowledging climate urgency, the current narratives (and the decisions that stem from them) are expected to fail in addressing oil dependency, favouring an expansion of oil extraction in the Arctic. Moving beyond this impasse will require acknowledging the contradictions and conflicts of interest. Transparency on this will be essential for ensuring that the country can reshape its policies and overcome its oil dependence. Finally, this study raises urgent questions about climate accountability for petrostates: if their climate responsibility does not go beyond domestic emissions, the green oil narrative—the use of renewable energy to power and thereby expand oil production—will remain a major obstacle to meaningful climate action.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S003224742510017X

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to Professor James Renwick who, despite his demanding schedule and numerous responsibilities, always makes time to offer kind guidance and support.

Financial support

The authors did not receive any financial support for this work.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interests.