The connection between deliberative theory and the literature on political rights and immigration is understudied. To start, we do know that many deliberative exercises transform participant opinions in more universalist, cosmopolitan and progressive directions (see also Gastil et al., Reference Gastil, Bacci and Dollinger2010). As such, the practice of deliberation – minimally defined as reason‐giving as well as engaging with and reflecting on counterarguments – might constitute a mechanism that not only sensitises participants for the frequent problématique of absent political rights of non‐citizen residents but also aligns them with the (progressive) argument that affectedness creates rights for political participation. However, a previous deliberative experiment on non‐citizens’ political rights involving university students found that deliberation does not make participants more favourable of foreigner voting rights (see below).

In this article, we provide, on the one hand, a theoretical framework for analysing and understanding deliberatively induced opinion formation (with a specific eye on directional changes in progressive or conservative directions); on the other hand, we conduct a larger‐scale deliberative experiment on foreigner voting rights in Germany with a design focused primarily on engagement with substantive arguments. Theoretically, we show that while there is a variant in deliberative theory that sees deliberative processes as an emancipatory project mainly tracking leftist political concerns (Neblo, Reference Neblo2007a), deliberative theory in general does not see the practice of deliberation as pre‐destined to liberal or progressive thinking. Rather, it is equally plausible that the better argument reflects communitarian notions and mirrors local and temporal circumstances (see Forst, Reference Forst2001). Transferred to the non‐citizen problématique, it is an open question whether deliberation aligns participants with the affectedness‐argument that grants unconditional political rights to foreigners, or whether it conduces participants to emphasise the requirement for strong ties and obligations towards a specific community for granting political rights. In this article, we pursue an exploratory approach that combines quantitative tests with analyses of substantive arguments to investigate these two options empirically.

Our empirical investigation sets up a virtual deliberative space geared towards short engagement with diverse arguments among almost 300 German citizens. Germany represents a particularly interesting case in this regard since it has a non‐citizen population of about 12.5 per cent (Bundesinstitut für Bevölkerungsforschung, 2021), and foreigners have limited access to political rights while being subject to a very restrictive citizenship regime from a comparative perspective (Howard, Reference Howard2009; Vink & Bauböck, Reference Vink and Bauböck2013). The question of non‐citizen voting rights is gaining increasing traction in the German public debate: in the run up to the German federal election in 2021, several news outlets published articles discussing the problem of disenfranchised residents. Our short virtual deliberative experiment put participants into an online deliberation space and asked them to engage with arguments in favour and against foreigner voting rights. It shows that compared to a pure control group, participants of the deliberation group were slightly less supportive of foreigner voting rights after the treatment, a potentially surprising result for those who assume that deliberation will tend to strengthen more liberal, universalist or inclusive outcomes. By the same token, participants in the deliberation treatment exhibited higher levels of argument repertoire and integrative complexity (especially compared to the pure control group) indicating that opinion formation was associated with more broad‐based and complex thinking (and not a product of gut reactions or poor reasoning). Finally, an in‐depth, qualitative analysis of participants’ rationales unravels that German citizens think that political rights must be attached to the obligations of citizenship.

This article has major ramifications for research on deliberation, citizenship studies and practical politics. For deliberative theory, the article distinguishes between a liberal and communitarian conception of deliberation (see also Forst, Reference Forst2001) and makes clear that a deliberative exercise does not quasi‐automatically produce progressive outcomes (as implied by the liberal variant). It even suggests that more deliberation might in fact lead to more exclusionary and group‐based perceptions. For the field of citizenship studies, the article reveals the deep connection that participants feel to civic obligations and joint commitment. With an eye on practical implications and the ongoing debate about political rights of foreigners, progressive reformers proposing the separation of citizenship and political rights (Song, Reference Song2009, Reference Song, Fine and Ypi2016) might not find much hope in (structured and short‐term) deliberative exercises.

Deliberating and reflecting about the boundaries of the demos

To date, very few explicit theoretical connections have been created between the political rights literature and deliberative theories. The added value of combing the two research strands lies in ‘proceduralising’ citizenship conceptions via deliberation, that is, putting the diverse arguments on the question of political rights on the table and asking citizens to reflect on them. In short, a deliberative exercise captures citizens’ complex thinking about political rights and citizenship when they have had the possibility to engage with arguments and reflect on the issue. This is especially productive for citizenship‐related issues since they entail ambiguity and ‘mixed feelings’ (Dempster & Hargrave, Reference Dempster and Hargarve2017; Duchesne & Frognier, Reference Duchesne and Frognier2008). Before we formulate concrete expectations on how a deliberative exercise might affect opinions on political rights, we first need to take a stab at the ongoing debate in the normative analysis of political rights.

On the question of constituting the demos, there is a growing debate on how to reconcile the basic right to democratic participation with an increasingly mobile population. Migration leads to the emergence of what Bauböck calls ‘quasi‐citizenship’ (Bauböck, Reference Bauböck2010). The past 30 years have seen an increase in the rights and possibilities for non‐resident citizens to vote, while the reverse, namely the rights of non‐citizen residents, has received much less political attention (Arrighi, Reference Arrighi, Giugni and Grasso2021). Many rights previously reserved for citizens have already been made available to immigrants (Howard, Reference Howard2009). The question is whether voting rights should become accessible to residents in the same way, or whether they are a special right that must be tied to citizenship. A core challenge around the debate on constituting the demos is rooted in the democratic principle that all those subjected to the coercive power of a state should be able to control its laws and institutions. In this article, our focus is on the dilemma of people in situations of ‘quasi‐citizenship’ who are not citizens of the states in which they permanently reside. There are two contravening positions on this dilemma: The first proposes to decouple voting rights from citizenship and to attach it to residence instead; the second proposes to maintain the connection between voting rights and citizenship.

For theorists who decouple political rights from the legal status of citizenship, the demos should be constituted either on the basis of the ‘all affected interests’ principle (Dahl, Reference Dahl and Fox1970; Goodin, Reference Goodin2007; Koenig‐Archibugi, Reference Koenig‐Archibugi2011; Song, Reference Song2009) – ‘everyone who is affected by the decisions of a government should have the right to participate in that government’ (Goodin, Reference Goodin2007, p. 51) – or on the basis of the more restrictive principle of non‐coercion (Beckman, Reference Beckman2009; Dahl, Reference Dahl1989; López‐Guerra, Reference López‐Guerra2005): ‘everyone subject to law has a categorical right to participate in the process of making laws’ (Dahl, Reference Dahl1989, p. 126). Many thinkers in this camp argue this holds in particular for long‐term residents who are permanently subject to laws of an entity they cannot determine (Smith, Reference Smith2008; Theuns, Reference Theuns2021). Even in liberal democracies which might protect some rights of residents, republican thought sees non‐citizen residents as subject to unjustified domination: whether or not their rights are protected or their wishes taken into account will depend on the benevolence of those others who have the power to vote (Abizadeh, Reference Abizadeh2012; Benton, Reference Benton2010). In addition, those who live in a country have what Rubio‐Marín calls ‘deep affectedness’. Through interpersonal, professional and territorial relationships, they have a stake in the present and future of the place (Rubio‐Marín, Reference Rubio‐Marín2000). This entitles them to political claim‐making (Smith, Reference Smith2008), especially given that due to their economic and social contributions, resident immigrants already fulfil many ‘civic’ obligations (Carens, Reference Carens and Brubaker1989, Reference Carens2005). These points could be addressed by disconnecting voting rights from the status of citizenship.

On the other hand, there are a number of theorists who propose to maintain the connection between voting rights and citizenship. Walzer, for example, forcefully defends the right of states to make selective admission decisions in order to preserve their integrity as ‘communities of character’ (Walzer, Reference Walzer1983, p. 62). Bauböck stipulates that ‘membership in a democratic polity must have a sticky quality’ (Bauböck, Reference Bauböck2009, p. 20). First, granting voting rights without full citizenship involves the danger of establishing second‐class citizenship, which means that foreigners may be entitled to vote without fully belonging to a specific community (Celikates, Reference Celikates, Cassee and Goppel2012). Second, connecting voting rights to citizenship is seen as important for social cohesion within democratic communities. Cohesion is said to contribute to social trust (Miller, Reference Miller2008) and enable people to become active in participating in politics and society (Theuns, Reference Theuns2021). Carens goes one step further by advocating that the naturalisation of long‐term residents is not only a right but an obligation, both for the host country and the immigrant (Carens, Reference Carens and Brubaker1989, Reference Carens2005). Obligations are also the focus of de Schutter and Ypi in their conception of ‘mandatory citizenship’, which sees political membership not only as an entitlement but also as a burden (De Schutter & Ypi, Reference De Schutter and Ypi2015). They see citizenship as including both legal and normative obligations, the full fulfilment of which requires the association only connected with the status of citizenship (see also Miller, Reference Miller2008). Granting access to rights without obligations has the problematic implication that some resident citizens hold the full scope of both rights and obligations, whereas other resident non‐citizens enjoy rights without being tied to the full range of obligations (De Schutter & Ypi, Reference De Schutter and Ypi2015).

What then is the role of deliberation in this debate? Would deliberation give priority to one of two contravening positions? To shed light on this question we build on a useful but rarely used distinction between two variants of deliberation, a liberal and a communitarian one (Forst, Reference Forst2001). Regarding the liberal variant, Neblo (Reference Neblo2007b: p. 548) holds: ‘On this understanding [which he dubs “progressive vanguardism”], deliberative democracy is intrinsically and primarily an emancipatory project with strong substantive content, more or less tracking leftist political concerns’.Footnote 1 Other deliberative scholars are less explicit about the substantive content of opinion change, but rather understand deliberation as a mechanism through which actors are expected to step out of their everyday reasoning and adopt a hypothetical and impartial attitude towards the topic under discussion. Given the dedicated focus of deliberative theory on impartiality, generalizability and inclusion, this tends to privilege positions appealing to the equality of human rights and universal principles of justice (Deitelhoff, Reference Deitelhoff2006; Habermas, Reference Habermas1991, Reference Habermas1999; Neblo, Reference Neblo2007b). Gutmann and Thompson argue that deliberative democracy is based on principles such as reciprocity and mutual respect, especially towards minority concerns (Gutmann & Thompson, Reference Gutmann and Thompson2000). Englund (Reference Englund2022) has recently described the ‘deliberative citizen’ as someone being open to cosmopolitan thinking, particularly in the context of migration and ethnicity (Englund, Reference Englund2022). Gastil et al. (Reference Gastil, Bacci and Dollinger2010) put it as follows: ‘Given deliberative theory's emphasis on hearing different points of view and considering the experiences of all, it is plausible that in the aggregate [it] could tend to promote cosmopolitanism’. Or, as Chambers (Reference Chambers2003: p. 318) notes, deliberation tends to promote toleration and understanding ‘all of which would tend to yield a more cosmopolitan viewpoint’. In sum, prominent deliberative theorists tend to assume that deliberative outcomes will be other regarding, inclusive and even cosmopolitan.

Empirically, opinion shifts in the direction of progressive positions are a frequent finding of deliberative events: after deliberation, participants have become more open to women's rights, measures against climate change or less punitive measures against crime (Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Suiter, Cunningham and Harris2023; Luskin et al., Reference Luskin, Fishkin and Jowell2002; see also Sanders, Reference Sanders2012, p. 24; for exceptions see Wojcieszak & Price, Reference Wojcieszak and Price2010). This is also true for immigration‐related topics: both in the US and the Finish context, deliberating citizens who were initially sceptical about immigration became more permissive and depolarized their prior opinions (Fishkin et al., Reference Fishkin, Siu, Diamond and Bradburn2021; Grönlund et al., Reference Grönlund, Herne and Setälä2015).

By contrast, Forst (Reference Forst2001) suggests that another deliberative conception exists, namely a communitarian variant claiming that deliberations mirror local and temporal circumstances. On this account, good reasons are identified on the basis of existing communal values and self‐understandings: ‘The criterion for what makes a political reason a good reason is not understood as conformity to general principles but as conformity to particular values’. (Forst, Reference Forst2001) Some associate communitarianism with conservative preferences for national sovereignty (see, e.g., Koopmans & Zürn, Reference Koopmans, Zürn, Koopmans, de Wilde, Merkel, Strijbis and Zürn2019), which would be conducive to negative opinions (and opinion shifts) vis‐à‐vis foreigner political rights. We adopt a more generic position of communitarianism, claiming that what matters are existing communal values, irrespective of their conservative or progressive orientation. As such, the communitarian variant is open both to conservative and progressive opinion trends and rather depends on existing attitudes and opinions before deliberation. The communitarian variant – as we define it – is in line with deliberative theorists arguing that the direction of opinion change cannot be predicted but is an open‐ended product of the deliberative process itself. The purpose of deliberation here is to reflect on and clarify community values (Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge1983), making deliberative outcomes context‐dependent. Empirically, few studies explore whether and how deliberation activates communal values. Nonetheless, some results point in this direction: increased scepticism for minority rights was detected in a previous deliberative experiment on same‐sex marriage in the United States and Poland (Wojcieszak, Reference Wojcieszak2011; Wojcieszak & Price, Reference Wojcieszak and Price2010); the authors associate this with pre‐existing public opinion as well as a polarized public debate on the issue. In this light, the issue of non‐citizen voting rights which relates closely to minority rights and the polarized issues of immigration and national identity is particularly well‐suited to explore whether communitarian deliberation is activated.

If we assume that communitarian deliberation activates predominant communal values, it is important to consider the debate on non‐citizen voting rights in the context of our country case, Germany. Germany was long designated a country where nationhood was viewed as ‘particularist, organic, differentialist and Volk‐centred’ (Brubaker, Reference Brubaker1992 p. 386). After highly politicized discussions, a large‐scale citizenship reform facilitated access to German citizenship in 2000. Many observers saw this as a move towards a more civic implementation of German citizenship (Howard, Reference Howard2009), even though full‐scale dual citizenship was prevented by political opposition (Hoffmann, Reference Hoffmann2004). Reservations towards liberalising citizenship are still strong in Germany, exemplified by the so‐called ‘lead culture’ debate which makes cultural commonality a requirement for citizenship (Pautz, Reference Pautz2005). Consequently, public opinion on political rights for foreigners may still be tilted towards the immigration‐restrictive pole which would be activated should a communitarian variant of deliberation hold.

In the following, we explore which version of deliberation applies when ordinary citizens are exposed to a (minimal) deliberative treatment (see next section) about granting political rights to foreigners. We also investigate the exact drivers behind opinion formation by analysing outset positions, argument quality and substantive reasons. This allows opening the black box of deliberative opinion change. Concretely, we proceed as follows:

First, we assess the direction of opinion change. If the liberal variant applies, then we should see opinion shifts towards more political rights of foreigners. If the communitarian variant applies, we should see a clarification effect, that is, no opinion change or even a reinforcement of prior opinions. Hereby, we also draw on psychological research and predict that participants with strong prior attitudes might polarize their opinions, especially when they engage with information (see Hart & Nisbet, Reference Hart and Nisbet2012). Due to the exploratory nature of this step, our design cannot make a final assessment of whether liberal or communitarian deliberation prevails. It can nonetheless provide indications of how such variants can be captured in practice.

Second, we analyse whether and how a deliberative treatment affects participants’ own reasoning. For the deliberative outcomes to have deliberative value we expect higher levels of deliberative quality (measured as argument repertoire and integrative complexity (see below)) compared to a pure control and information‐only group. As such, argumentative quality is on the one hand an indicator for depth of opinions, and on the other hand a measure of success of the deliberative design. Note that this investigation is confirmatory, as previous research finds that deliberation increases argument quality (see e.g., Jennstål, Reference Jennstål2019), though few designs have tested this connection in a design as minimal as ours.

Third, we focus on the substantive content of the discussion. While deliberative experiments usually concentrate on opinion change and occasionally check for deliberative quality, they have often failed to take a closer look at the rationales provided by participants. Analysing the content of arguments will help us better understand opinion formation. The goal of this analysis is an exploratory study of emerging argument categories (see e.g., Burnett & Badzinski, Reference Burnett and Badzinski2000). Depending on which variant applies (liberal or communitarian), we expect that participants of the deliberating group will find more arguments that speak for or against foreigner voting rights.

The experiment

We conducted an online survey experiment with 286 German citizens in fall 2020. Based on power calculationsFootnote 2, we estimated that 300 persons (and 100 per treatment) are sufficient to detect meaningful opinion changes (should they occur). The survey company recruited about 450 participants; of which 286 could be used for the analysisFootnote 3. The dropout rate is indicative of the relatively high demands that even a fairly minimal deliberative research design places on survey participants.

The sociodemographic composition of the sample matches large‐scale population samples in Germany on most relevant accounts such as age, gender, migration background and political identity (on a right‐to‐left scale). However, there are slight imbalances, with participants of the survey experiment having slightly more interest in politics and higher political trust, being better educated and living more frequently in East Germany (see Supporting Information Appendix 1). Those willing to participate were assigned randomly to three groups, an information‐deliberation group, an information‐only group and a true control group. This setup also allows disentangling information from deliberation effects (Esterling et al., Reference Esterling, Neblo and Lazer2011). Overall, randomisation into the three groups worked well, despite some small biases for gender, age and university degree (see Supporting Information Appendix 2).

In the first stage of the experiment, the information‐deliberation and the information‐only groups were asked to read three arguments in favour of and three arguments against introducing foreigner voting rights. The true control group, by contrast, received a placebo treatment in the form of a general information text on voting rights in Germany.Footnote 4 For the information and deliberation treatment, arguments in favour and against were based on a set of statements on citizenship. These statements were formulated and selected through a so‐called concourse on citizenship, a procedure that collects a broad set of discursively constructed perspectives on a topic (see Supporting Information Appendix 3). This means that the arguments reflect diverse views on political rights for foreigners that echo public discourse. Arguments in favour reflected three aspects of the debate: (1) democratic societies require equal rights for all based on residence; (2) long‐term residents are already part of societies regardless of their citizenship status; and (3) European integration will be facilitated by access to national voting rights based on residence. Arguments against foreigner political rights also reflected three aspects: (1) citizens entitled to vote would safeguard democracy; (2) those participating in national elections should share common values and culture; and (3) voting should be attached to a full range of (informal) civic responsibilities.

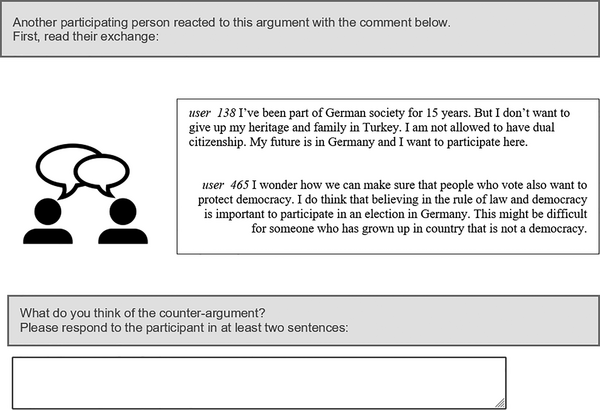

For the information‐only group, the treatment ended after viewing these arguments. Participants in the short virtual deliberative treatment group were put into an online deliberation space and asked to more deeply engage with two of the arguments, one in favour of and the other against foreigner voting rights. The basic idea is to create an environment where participants engage with the substantive arguments and are not influenced by social dynamics, a point to which we return below. To achieve this, participants were presented with an argumentative exchange on foreigner voting rights in written form and were asked to formulate their response in writing (see Figure 1). Arguments in favour and against were randomised and presented as if they were made by other participants. In concrete terms, the pro and con arguments presented in the forum were put into colloquial form. We took care not to add additional information to this exchange, but to only re‐iterate notions from the six original arguments. This avoided that the information‐deliberation group would receive more factual information than the information‐only group. However, an argument in favour of political rights of foreigners was made by a mock participant with migrant background in order to stimulate thinking about affectedness.

Figure 1. Extract from the deliberative treatment

This minimal and virtual deliberative setup has two advantages and one drawback. By keeping our deliberation treatment minimal – with participants only being asked to reflect on and react to pre‐scripted comments – we are in a position to test the effects of short virtual deliberation in a clean design. In standard deliberative settings, the iterated nature of the communication process may produce dynamics that violate the stable unit treatment value assumption (SUTVA) and impair our ability to draw causal inferences (see Esterling, Reference Esterling, Bächtiger, Dryzek, Mansbridge and Warren2018). By the same token, our fixed setup (involving full balance of pro and con arguments) also suppresses undesired group dynamics, a problem that can occur in some deliberative formats (such as free discussion with no facilitation and no deliberative norms (Baccaro et al., Reference Baccaro, Bächtiger and Deville2014)). Anonymity, furthermore, has the advantage that social dynamics and cue‐taking are suppressed (Esterling, Reference Esterling, Bächtiger, Dryzek, Mansbridge and Warren2018).

The drawback is, of course, that the virtual setup does not represent a fully‐fledged deliberative setting where participants engage in an extended and dynamic process of a ‘give‐and‐take’ of reasons (Tanasoca, Reference Tanasoca2020), and social effects of deliberation such as empathy‐building are restricted (see e.g., Grönlund et al., Reference Grönlund, Herne and Setälä2017, Muradova, Reference Muradova2021). Nonetheless, our setup fulfils minimal deliberative requirements (Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge, Heller and Rao2015) in that participants had to read and engage with diverse arguments and give reasons for their positions. Consequently, we call the treatment a short virtual deliberative treatment. We acknowledge that a deliberative process might involve personal stories and emotions, but in this design, we prime on substantive arguments. As such our design realises a process of ‘individuals revising and developing their own views as they debate and engage with others and “think out loud” in public. This form of socially mediated yet individual deliberation is insufficiently explored in contemporary political science’, (Stoker et al., Reference Stoker, Hay and Barr2016 p. 18).

In a second stage, all participants – including those in the information‐only and the true control group – listed their own arguments first in favour of and second against foreigner voting rights. This allows measuring whether the three groups have different levels of argument repertoire and integrative complexity after the treatment (see below). Moreover, participants’ statements also provided substantive rationales for rejecting or accepting foreigner voting rights, a dimension frequently neglected in deliberative research (see Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge, Schwartzberg and Viehoff2020).

Operationalisation

We focus on three dependent variables: opinion change, argumentative quality and argumentative substance. We measure opinion change as the difference in positions on foreigner voting rights before and after the treatment. Positions on foreigner voting rights were measured on a 0–100 scale, where 0 indicates strong rejection and 100 indicates strong approval of granting voting rights to non‐citizen residents of at least 5 years. Regarding argumentative quality, we employ two measures: argument repertoire and integrative complexity. Argument repertoire captures the range of arguments people hold both in favour and against their own viewpoint. It is frequently seen as a measure of opinion quality (Capella et al., Reference Capella, Price and Nir2002), and measured based on a question asking participants to list arguments in favour of and against foreigner voting rights separately. We counted how many arguments each participant made. Integrative complexity, in turn, is a psychological construct and captures ‘differentiation’ of viewpoints (i.e., the extent to which participants take a multitude of perspectives into account) and the ‘integration’ of viewpoints (i.e., the degree to which participants account for complexities in their reasoning). Integrative complexity is measured on the basis of an automated LIWC (Linguistic Inquiry & Word Count) dictionary‐based approach (Brundidge et al., Reference Brundidge, Reid, Choi and Muddiman2014; Wyss et al., Reference Wyss, Beste and Bächtiger2015). Finally, we explore participants’ substantive rationales in favour of or against foreigner voting rights to better understand the drivers behind opinion change (or stability).

Results

We start with opinion change (and stability). Before the experiment, participants reported a mean response of 41.2 points (out of 100 points), which is indicative of a sceptical position towards the political rights of foreigners. In the following, we focus on individual‐level opinion change. We employ OLS regression analysis to estimate the treatment effect. To avoid ‘ceiling effects’, post‐treatment opinions are regressed on pre‐treatment opinions (Luskin, Reference Luskin2002; see also Luskin et al., Reference Luskin, Fishkin and Jowell2002). We also include a model with pre‐treatment control variables to control for slight imbalances across the three treatment groups (see above) as well as to reduce noise and increase power in the experiment (Broockman et al., Reference Broockman, Kalla and Sekhon2017).Footnote 5 The pre‐treatment controls are: gender, age, university degree, migration background and opinions on ethnic and civic national identity as well as on citizenship (all of which are deeply interlinked with preferences on foreigner voting rights). Their operationalisations can be found in the Supporting Information (Appendix 5). These models should be seen as a first exploratory test of whether a communitarian variant of deliberation is worth further investigationFootnote 6. This statistical test should be interpreted in combination with the qualitative results we derive from substantive arguments below.

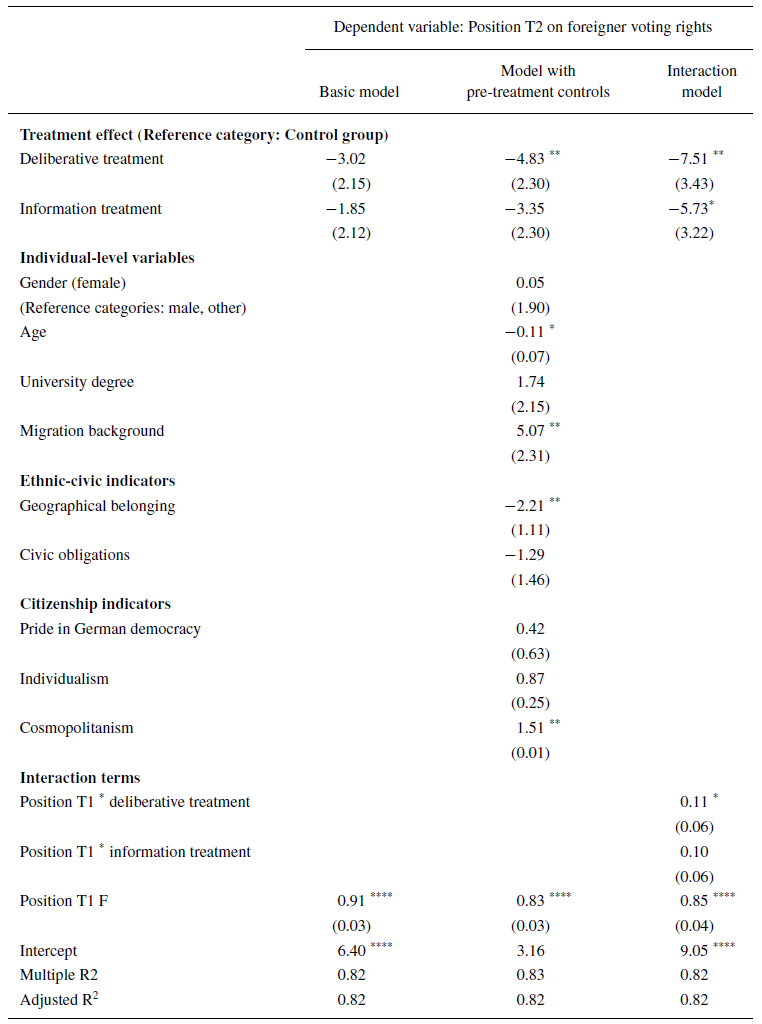

We calculate three models to explore communitarian and liberal variants of deliberation in this experiment (see Table 1). First, a first‐difference modelFootnote 7 without pre‐treatment controls yields only small effects with large standard errors (without statistical significance) across the three groups. Second, adding the pre‐treatment controls to the model, we find that the deliberation group is less positive toward voting rights for foreigners after the treatment compared to the control group, even though the substantive effect is small (about 5 points on a 100‐point‐scale). Third, more substantive differences emerge when we interact the initial positions on foreigner voting rights with the treatment conditions. The deliberation group now scores more than 7 points lower than the control group, while there is also a statistically significant difference between the information‐only and the control group (with the former scoring lower on foreigner voting rights after the treatment than the latter). The interaction term between initial position on foreigner voting rights and the deliberation treatment indicates that the effect of deliberation is contingent on the position of participants at the outset: while we observe a slight positive (and marginally significant) trend for those who had positive positions initially (in comparison to the control group), we find a negative trend for those who were sceptical of foreigner voting rights. Upon closer inspection, we see that this holds especially for those situated at the extremes: we observe a slight positive trend for those who had very positive positions initially (i.e., rated acceptance of foreigner voting rights with at least 90 points), and a negative trend of those who were sceptical of foreigner voting rights initially. This negative trend can be observed for nearly all those who rated foreigner voting rights negatively at the outset (i.e., 50 points or lower) but again is the strongest for those at the extremes (i.e., who accepted foreigner voting rights with 10 points and less)). This is indicative of a clarification effect of deliberation, where participants find out where they really stand and therefore become firmer in their positions after the deliberative treatment. The clarification effect is further supported through an analysis of individual‐level changes, especially for those participants with already negative views (i.e., a position <50). Among those with already negative views, the proportion of those with opinion polarization is highest for the deliberation group (36.7 per cent of those with negative views polarized their view, compared to only 24.1 per cent in the pure control group). Only 8.4 per cent of participants switched sides (i.e., moved from <50 to >50 on the scale).

Table 1. Opinion change

Note: N = 286 for all models; Standard Errors in parentheses; where

*p < 0.1;

**p < 0.05;

***p < 0.00.

Overall, we do not find any indication that deliberating participants more strongly support political rights of foreigners in the aggregate, as predicted by the liberal variant of deliberation. This difference even holds if we run the models only with those participants in the sample who have migration background (and thus have potentially greater personal affectedness regarding foreigner political rights [see Supporting Information Appendix 6]). These results are indicative that the communitarian variant of deliberation may be at play.

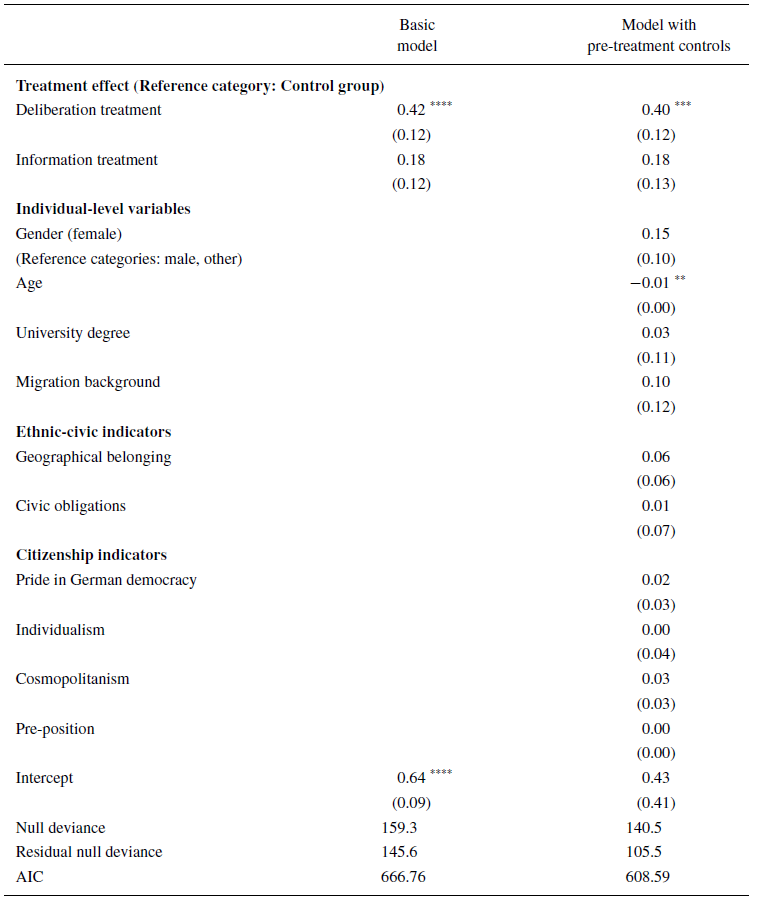

Next, we focus on argument repertoire and integrative complexity. Since the variable argument repertoire is highly skewed, we employed a Poisson regressionFootnote 8, again with and without pre‐treatment covariates. We find that the deliberation group has a higher argument repertoire compared to the information‐only and especially the control group (see Table 2). Being part of the deliberation group increases argument repertoire by about half an argument on average. An analysis of the raw figures indicates that participants of the control group produced between one and six arguments (about 36 per cent producing only one argument), whereas participants in the information‐only and the deliberation groups produce between one and eight arguments. In the deliberation group, almost 25 per cent produced two arguments while 22 per cent produced four arguments or more.

Table 2. Treatments and argument repertoire

Note: N = 286 for all models; Standard Errors in parentheses; where

*p < 0.1

**p < 0.05;

***p < 0.00

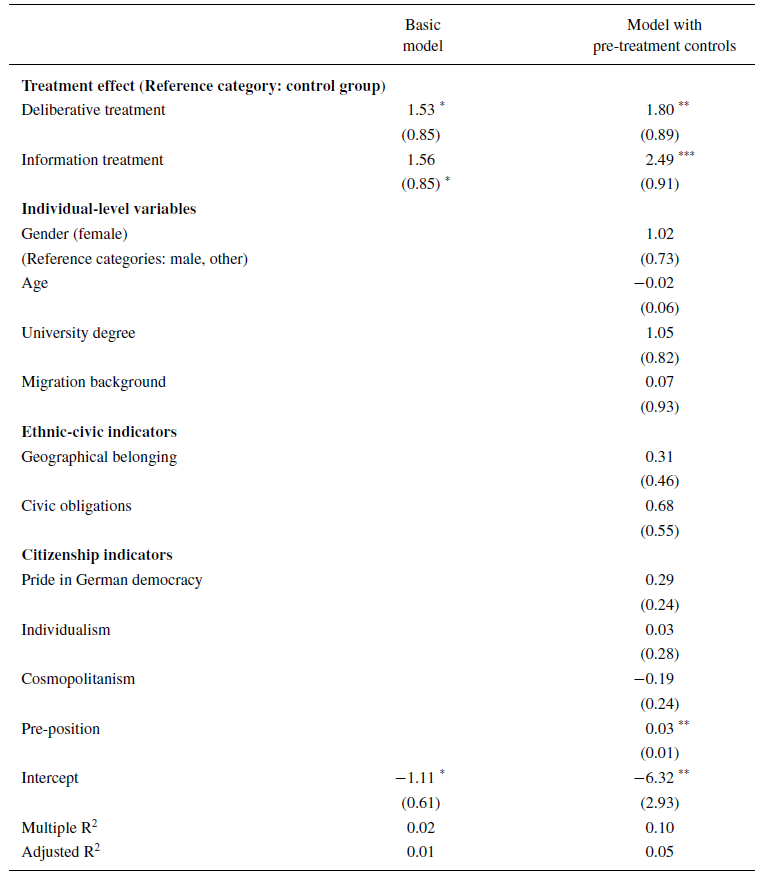

While this indicates that opinion stability (or partial opinion polarization) in the deliberation group was associated with more reasons than in the information and control group, we now check whether those reasons were also more sophisticated. We do so by focusing on integrative complexity measures, which are analysed for both pro and con arguments listed by the participants. An OLS regression (see Table 3) shows that both the deliberation and information treatment groups have higher levels of integrative complexity compared to the control group (the slight differences in integrative complexity between the deliberation and information‐only group are not statistically significant; see Appendix 7). The results on argument repertoire and integrative complexity underline that our virtual deliberative treatment produced deliberative value by enhancing participants’ breadth and depth of argumentation.

Table 3. Treatments and integrative complexity

Note: N = 286 for all models; Standard Errors in parentheses; where

*p < 0.1

**p < 0.05;

***p < 0.00.

This, however, does not imply a causal relationship between argument repertoire, integrative complexity and opinion change. To establish such a relationship, we would need to experimentally induce higher levels of argument repertoire and integrative complexity and test respective effects via a parallel or crossover design (Imai & Yamamoto, Reference Imai and Yamamoto2013). But what stands out is the fact that, in the deliberative treatment group, participants – especially those with negative pre‐dispositions on political rights of foreigners – considered a larger pool of substantive arguments and underlying rationales than participants in the information‐only and control groups. It demonstrates that a short virtual deliberative treatment led to clarification and consolidation of opinions on the complex issue of access to political rights.

Therefore, in a final step, we focus on the substantive rationales behind opinion formation, unravelling those consolidated opinions and explaining why participants in the deliberation group did not endorse political rights of foreigners. Our qualitative analysis of substantive rationales is again based on the list of arguments made in favour of and against foreigner voting rights. All arguments were collected and categorised in several rounds of in‐depth reviewing. This entails reading each individual statement (i.e., argument) in the first round, exploring the context (i.e., all arguments given by one person altogether) in the second round, and finally making sense of arguments in a broader context (i.e., the discussion around foreigners’ political rights [Gerbaudo, Reference Gerbaudo2016; Saldaña, Reference Saldaña2015]). The arguments were coded, and codes revised accordingly after each round. At the end, arguments were summarised under seven broad themes: geographical factors and common life, economic factors, democracy, obligation, commonality, legal concerns and conditionality. Sub‐aspects were defined for each category to make the coding more specific (see Supporting Information Appendix 8). In the coding process, each argument was counted as belonging to one specific code; this was nearly always unambiguous because arguments were mostly formulated in a very straightforward way.

Arguments produced by participants in favour of foreigner voting rights mainly fall in the democracy category and revolve around three themes: First, many arguments acknowledge that it is not fair or democratic for people whose life is in a place to not hold a vote there. Second, arguments understand voting rights as a path to citizenship. They see partaking in an election as an opportunity for non‐citizens to learn about the political system and important developments in the country. Third, arguments see voting rights as a logical consequence of an interconnected world: as people become mobile, we cannot expect them to be tied to one place in the long term and should be more flexible about our ideas of belonging.

Arguments produced by participants against foreigner voting rights frequently propose that non‐citizens should naturalise instead. Overall, many participants demonstrate in their reasoning that they are willing to accept foreigner voting rights under conditions that are similar to the conditions tied to naturalisation, such as length of residence, knowledge about the political system and history, language skills and acceptance of the basic premises of the constitution. These arguments acknowledge that many foreigner residents already fulfil these obligations (and many participants do say that foreigners should be given the vote so long as they fulfil these criteria).

Many arguments against foreigner voting rights also target obligation more specifically, albeit in different ways. Some arguments use the terminology of obligation directly to ask for commitment to Germany, responsibilities tied to voting, or loyalty to the German constitution and democracy. Arguments made on obligations connected to democratic participation do not want people to vote without considering their choice, or without being informed about the past and present of the country. Other arguments cast obligation as mainly economic and propose that those allowed to vote should have a workplace, pay taxes or be financially independent. Many arguments emphasise geographical belonging: if foreigners obtain voting rights, then they must be committed to stay in the long‐term. This commitment should go beyond simple residence: foreigners should also be committed to the country, to share basic democratic principles or to contribute to the economy and society. As a minimum, foreigners should see their lives rotating primarily around the place of residence. A final group of arguments rejecting foreigner voting rights stresses the importance of common culture or common values. Those who partake in democratic decisions must share a common conviction to certain values or norms – ranging from a commitment to liberal democracy to a shared way of life, tradition or religion. Some arguments also view this as a way to safeguard a ‘German way of life’.

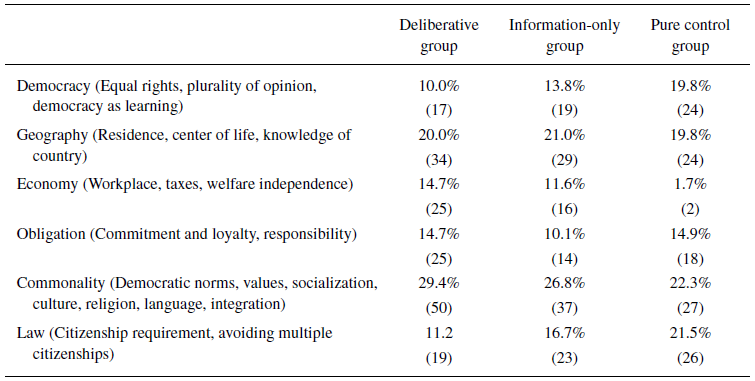

Table 4 displays how often each theme was invoked by participants of the deliberative and the pure control groups respectively. As can be gleaned from Table 4, the majority of arguments fall in the categories of obligation, commonality, geography, economy and law which tend to imply restrictive versions of granting voting rights to foreigners; by contrast, the democracy category which entails ideas about enfranchising foreigners is only mentioned in about 10–20 per cent of the arguments. Moreover, we see that there are differences across the groups: the democracy arguments are least mentioned in the deliberation group and most mentioned in the control group; the other themes are invoked in relatively equal parts by each group except for economic factors (which the control group hardly refers to). These results show that the deliberation group invoked arguments connected to obligations and commonality more frequently, and arguments favouring foreigner voting rights (which fall in the democracy category) less frequently. This indicates that communitarian deliberation also seems to be driven by a different weighting of substantive arguments.

Table 4. Treatments and substantive arguments

Note: Relative (and absolute) number of themes invoked in pro and con arguments on foreigner voting rights

Overall, our analysis of substantive rationales reveals that participants echo many of the arguments put forward by de Schutter and Ypi (Reference De Schutter and Ypi2015) in their proposal for mandatory citizenship. Sceptics of foreigner voting rights usually do not take issue with the fact that foreigners vote but with the fact that they would be granted an important citizenship right without necessarily bearing corresponding obligations. The condition to share in a common centre of life is strongly mirrored in participants’ arguments demanding long‐term attachment to geographical place, a concrete commitment to economy or society, or a feeling of connectedness and primary loyalty. De Schutter and Ypi also dub these as ‘informal obligations’, that is, civic obligations that are not predetermined by law but by informal practice. While some participants argue that political rights should be granted to immigrants who already fulfil these obligations, others feel that citizenship adds a layer of obligation and commitment that long‐term residency fails to deliver. In short, long‐term residents must be more than ‘permanent guests’ (De Schutter & Ypi, Reference De Schutter and Ypi2015, p. 241) if they are granted voting rights. Notice that De Schutter and Ypi argue that ‘mandatory citizenship simultaneously implies that the state is obliged to grant citizenship to foreigners automatically and facilitate full belonging for new citizens’ (De Schutter & Ypi, Reference De Schutter and Ypi2015). It is questionable, however, whether such automatic naturalisation would find support among those demanding assimilation in exchange for citizenship. In sum, while ‘informal obligations’ strongly matter for the participants of our experiment, their exact shape and implications remain contested. These findings may explain the above puzzle of why our deliberative treatment leads to negative positions despite its increase of argument quality: it may not be the quality of arguments alone that matter, but also the type of arguments participants find most valuable or relevant in their analysis of the issue.

Discussion

Although deliberation is often said to conduce to progressive outcomes (and also does so in many deliberative events), our deliberative experiment on foreigner voting rights tells a different story: participants of the deliberating group did not move towards a more progressive standpoint of granting non‐citizen residents the right to vote. While previous deliberative experiments on immigration indicate a depolarizing effect (Grönlund et al., Reference Grönlund, Herne and Setälä2015), our analyses point to a clarification effect, whereby especially those with already negative views at the outset increased their disapproval (compared to the control group).

Surely, our deliberative treatment was minimal (targeted at the cognitive and epistemic functions of deliberation) and one might claim such minimal and asynchronous forms of deliberation do not produce major opinion changes. But higher levels of argument repertoire and integrative complexity clearly show that our deliberative treatment produced deliberatively desired effects. And since the treatment concentrated on argumentation and avoided non‐deliberative dynamics – such as social cues – it may also be true that well‐organised deliberations produce far less opinion change than commonly assumed.Footnote 9 Our deliberative experiment also relies heavily on the arguments presented to participants within our design. Notice that these are based on a concourse on citizenship and are reflective of arguments voiced by citizens in the real world (Maier, Reference Maier2021).

Notice further that a similar result was obtained in an in‐person two‐hour deliberation on foreigner voting rights. This experiment was applied to university students – a demographic that tends to be more progressive and leftist than the average population (Baccaro et al., Reference Baccaro, Bächtiger and Deville2014). This suggests that our results are not a product of our minimal deliberative treatment, but represent a more general effect of considered opinions on this topic.

Our results may seem puzzling for some deliberative enthusiasts with a liberal orientation. The analysis of substantive reasons shows that participants particularly value arguments that relate to obligations and commitments to a political community. Hence, a deliberative process is not quasi‐automatically programmed towards progressive outcomes (as the liberal variant of deliberation suggests and as some have speculated on the basis of empirical findings) but may also trigger (or reinforce existing) conservative tendencies if these are prominent in public discourse or prior opinions (as proposed by the communitarian variant). Since this study is one of the first to explore the distinction between liberal and communitarian deliberation empirically, it cannot provide a final assessment of the existence and activation of these variants. Nonetheless, our empirical results strongly suggest that in the context of non‐citizen voting rights, communitarian forms of deliberation were prevalent, with German participants making frequent references to so‐called ‘lead culture’ debate which makes cultural commonality a requirement for citizenship (Pautz, Reference Pautz2005).

In the future, it would be interesting to find more evidence for liberal and communitarian variants, respectively. In this regard, it would be helpful to explore the drivers behind the communitarian tendencies found in our deliberation group as well as disentangle the impacts of pre‐existing opinions, prominent public discourses and individual identities. As mentioned above, German immigration policies and public discourse in the last 15 years have emphasised restrictive positions on naturalisation and immigration, which participants might draw on in their reasoning. Deliberatively engaging with non‐citizen voting rights could have made citizenship identity salient and emphasised its individual significance to participants. It might also have led participants to reckon with the more general meaning and implementation of rights and their costs, as the proposal for mandatory citizenship suggests (De Schutter & Ypi, Reference De Schutter and Ypi2015). Future research will need to zoom in on the exact rationales that undergird opinion formation on citizenship issues. While our study is one of the first to investigate deliberative opinion change in combination with a qualitative analysis of substantive reasons, future investigations could benefit from further mixed‐methods approaches, for example, by conducting in‐depth interviews with participants on why they changed their minds (or stuck with their initial opinions).

We acknowledge that our results are limited to the specific context of Germany. It is possible that more inclusive and liberal citizenship regimes entail more progressive discourses, conducing citizens to put a stronger emphasis on the democratic aspects of foreigner voting rights. An analysis of further country contexts seems promising based on a range of existing results. For example, a 2015 referendum on introducing foreigner voting rights in Luxemburg failed with a strong opposition of 78 per cent (Government of Luxembourg, 2015). Ahead of the referendum, public opinion polls actually showed a 60 per cent support for introducing foreigner voting rights (Finck, Reference Grönlund, Herne and Setälä2015), a tendency that seems to have reversed during the campaign. Though the dynamics of opinion transformations may differ from our experiment, it nonetheless underlines that non‐citizen voting rights are contentious and potentially polarizing in public debate. Moreover, our findings underline the challenge of law‐making in the context of minority rights, and immigrant rights in particular. Promoting the rights of immigrants via participatory practices – such as direct democratic voting – is often unsuccessful (Veri, Reference Veri2019, Arrighi, Reference Arrighi, Giugni and Grasso2021), a result supported by cross‐country investigations (Bochsler & Hug, Reference Bochsler and Hug2015). Citizenship policies are highly politicized and often mobilized by political parties for vote gains (Vink & Bauböck, Reference Vink and Bauböck2013). Our analysis shows that deliberation does not necessarily fare better in this regard. Even though many progressive reformers have a soft spot for participatory tools, they may need to re‐think the pathways to realising their goals. Veri, for example, makes the provocative recommendation that in order to succeed, the expansion of citizen rights ‘must be hidden from public scrutiny and embedded in a general constitutional reform,’ (Veri, Reference Veri2019, p. 419).

Concluding remarks

This article is one of the first to bring together the fields of deliberative theory and citizenship studies. Drawing from a short virtual deliberative experiment with almost 300 German citizens, we find that compared to a control group, participants in the deliberative group mainly experienced a clarification effect rather than increasing their support of foreigner voting rights. By the same token, participants in our deliberative treatment displayed higher levels of argument repertoire and integrative complexity (especially in comparison with the control group), underlining that the process of opinion formation was not irrational. Finally, a qualitative analysis of participants’ substantive reasons unravels traces of what De Schutter and Ypi (Reference De Schutter and Ypi2015) dub ‘mandatory citizenship’, implying that political rights must be attached to obligations, commitment and belonging to a community wherein rights are exercised. Even though participants acknowledge that many non‐citizens already fulfil these obligations, they are not willing to grant rights without any conditionality. To conclude, the practice of deliberation is not quasi‐automatically programmed to progressive outcomes but can have communitarian dimensions, unravelling deep‐seated existing discourses. Advocates and activists for foreigner voting rights can learn from our study that democratic innovations in the form of deliberation may not advance – and perhaps even subvert ‐ their ambitions. Put differently, political rights and citizenship are deeply contested issues, and citizens’ opinions not easily changed in progressive directions.

Acknowledgements

This project owes a lot to Lucio Baccaro who was the first to empirically find that deliberation may not ‘warm up’ citizens with non‐citizen voting rights (a knee‐jerk reaction by many who are asked to hypothesize about the relationship between deliberation and enfranchisement; see Baccaro et al., Reference Baccaro, Bächtiger and Deville2014); he was also one of the first to come up with the idea that deliberation may also activate communal values, not just liberal and progressive ones. We also thank Mark Warren, Ana Tanasoca, Marco Steenbergen, Lidia Valera‐Ordaz, Uwe Remer, Michael Saward and all participants of the Joint Sessions 2021 workshop organised by Toni Rodon and Marc Guinjoan and APSA 2022 section organised by Edana Beauvais.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Appendix 1: Comparison of Samples.

Appendix 2: Randomisation of Treatment Groups.

Appendix 3: Concourse on Citizenship in Germany.

Appendix 4: Full list of forum arguments on foreigner voting rights presented to the information‐only and deliberation groups (in randomized order).

Appendix 5: Operationalisation of control variables for the covariate model.

Appendix 6: Opinion change for participants with migration background.

Appendix 7: Integrative complexity model using deliberation treatment as reference category.

Appendix 8: Detailed categories of substantive arguments made by participants.