Introduction

The aim of the present study is to investigate the potential link between religious participation and civic engagement in Sweden. Sweden is considered a secularized country, meaning that religion is generally considered a private matter (von Essen & Grosse, Reference Von Essen and Grosse2019). Religious participation likely plays a different role in the secular context compared to a context where religion and politics are intertwined. Therefore, the link between religious participation and action in the wider community, such as charitable giving, volunteering, or participating in politics, may be less straightforward (von Essen & Grosse, Reference Von Essen and Grosse2019). Previous studies, such as Lam (Reference Lam2002), have argued that religiosity contains participatory, devotional, affiliative, and theological dimensions. In the present study, the empirical focus is on the participatory aspect of religiosity, as this study investigates the correlation between religious services attendance and other forms of civic engagement.

Recently, scholars (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart2021) argued that religiosity has declined rapidly and globally. Sweden may be considered a case of declining public religiosity within the specific context of a state church that turned into a civil society organization, in combination with an ample welfare state (Henriksen et al., Reference Henriksen, Strømsnes, Svedberg, Henriksen and Svedberg2019). Therefore, it is important to explore the links between religious participation and civic engagement to gain a better understanding of the social fabric surrounding those who attend religious services in secularized contexts. Whether the religiously active group is civically engaged or not may also have implications for which perspectives are represented in political debates. Connections between religious participation and other forms of engagement, such as charitable giving, volunteering, and participating in politics, have been found in several previous studies (e.g., de Hart et al., Reference De Hart, Dekker and Halman2013; Grizzle & Yusuf, Reference Grizzle and Yusuf2015; Halman & Luijkx, Reference Halman, Luijkx, Esmer, Klingemann and Puranen2009; Proteau & Sardinha, Reference Prouteau and Sardinha2015; Putnam & Campbell, Reference Putnam and Campbell2010; Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). However, the empirical results have been mixed, with scholars arguing for no link or a negative relationship between religious participation and civic engagement (Park & Smith, Reference Park and Smith2000; Proteau & Sardinha, Reference Prouteau and Sardinha2015; von Essen & Grosse, Reference Von Essen and Grosse2019; Yeung, Reference Yeung2017). Scholars have questioned whether religiosity actually promotes civic engagement beyond the religious community or whether religiosity facilitates engagement in activities connected to the religious congregation first (Proteau & Sardinha, Reference Prouteau and Sardinha2015; Uslaner, Reference Uslaner2002). The religious context may also have a significant impact on how religious participation affects other forms of civic engagement, as ties between religions and society at large may be constrained by legal and normative institutions (Grizzle & Yusuf, Reference Grizzle and Yusuf2015). Many influential previous studies on the relationship between religious participation and civic engagement have been conducted in the USA (Traunmüller, Reference Traunmüller2010). The US context has levels of religiosity that are higher than in most other Western democracies, albeit the number of declared unaffiliated citizens is increasing (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart2021). Studies have also found that those without religious affiliation are less likely to volunteer and to make charitable donations (Berger, Reference Berger2006). Therefore, there are lingering questions regarding whether religious participation is connected to civic engagement, operationalized as charitable giving, volunteering, and political participation, in secularized contexts as well. Thus, it is important to investigate the impact of participation in religious services on other forms of civic engagement in other contexts where religion often plays a less prominent role in public life, such as in Sweden (Meiβner & Traunmüller, Reference Meißner and Traunmüller2010). The Swedish case remains interesting also as a case of a former Lutheran state church as many of the previous studies on the link between religious attendance and civic engagement are from contexts without this experience.

Three main questions guided this study: First, do those who regularly attend religious services in Sweden volunteer and participate in charitable giving more often compared with those who do not? Second, are those who regularly attend religious services more, or less, politically active between elections compared with those who do not in Sweden? Third, do those who regularly attend religious services in Sweden receive more requests to volunteer than those who do not? Survey data on volunteering from two different cross-sectional countrywide representative random samples of individuals in Sweden were used. A theoretical overview and a short description of religion in the Swedish context follow. Then, the dataset, the results, and a concluding discussion of the results are presented.

Religion as a Motivating Force for Civic Engagement

Religion often comes with a special set of norms and values, and with prescriptive rules, intended to guide the behavior of the devout. Two often-used theoretical mechanisms that explain the link between religious participation and civic engagement focus on how religion influences values, norms, and behavior (i.e., socialization) or how religious participation is tied to other social networks that increase the probability of being asked or required to participate elsewhere by someone else (Berger, Reference Berger2006; Halman & Luijkx, Reference Halman, Luijkx, Esmer, Klingemann and Puranen2009; Inglehart & Welzel, Reference Inglehart and Welzel2005; Putnam & Campbell, Reference Putnam and Campbell2010; Traunmüller, Reference Traunmüller2010; Vermeer & Scheepers, Reference Vermeer and Scheepers2012; Wuthnow, Reference Wuthnow1999). These two sets of explanations can be seen as complementary rather than opposing (Berger, Reference Berger2006). As argued by Dekker and Halman (Reference Dekker, Halman, Dekker and Halman2003), the link between values and behavior does not entail a perfect correlation, as values are guidelines and constitute possible, but not the only, determinants of behaviors. Moreover, broader societal values, such as individualism and focus on self-realization, can increase the likelihood of volunteering as a way of self-fulfillment (Dekker & Halman, Reference Dekker, Halman, Dekker and Halman2003). The literature on philanthropy has pointed to the fact that most religions, and especially Judeo-Christian religions, contain norms that promote altruistic behavior, such as the valuing of the metaphor of the good Samaritan (Bekkers, Reference Bekkers2016; Wuthnow, Reference Wuthnow1999). Being an active participant in religious congregations through attending religious services can also be seen as participating actively in processes of socialization that ought to increase civic engagement such as volunteering (Yeung, Reference Yeung2004, p. 415; Putnam, Reference Putnam1993).

However, other explanations focus on the circumstances of how someone became civically engaged and, thus, receive requests to volunteer or to donate which are important for decisions to become engaged or to donate (Dekker & Halman, Reference Dekker, Halman, Dekker and Halman2003). As described by Teorell (Reference Teorell2003), those who are active participants in an organization, such as those who attend religious services, are exposed to different sorts of mechanisms that may elicit civic engagement. First, the organizations in which individuals participate may convey values and norms that encourage or entail an expectation of civic engagement. Civic engagement, such as participation in politics and charitable giving, may be directly encouraged either to achieve the organization’s goals or through more indirect processes of socialization where the organization’s values enhance civic engagement. Other scholars have argued that certain religious groups encourage and facilitate volunteering and charitable giving (Berger, Reference Berger2006). Second, those who participate in organized activities may receive requests to participate elsewhere as well and therefore be civically engaged (Teorell, Reference Teorell2003). Third, Teorell (Reference Teorell2003) proposed that those who participate in organizations may be associated with having certain characteristics that are appealing to those who recruit others, for example, being trustworthy or having skills and, thus, receive more requests from others to participate elsewhere.

Although most religions tend to promote altruistic and prosocial behavior, studies have also shown that volunteer rates and willingness to contribute to charitable giving seem to vary across religious affiliations (Bekkers, Reference Bekkers2016; Wilson & Janoski, Reference Wilson and Janoski1995). Protestants, for instance, tend to volunteer more often and donate more to charity than some other groups, such as Catholics (Bekkers, Reference Bekkers2016; Lam, Reference Lam2002; Wilson & Janoski, Reference Wilson and Janoski1995). Wuthnow (Reference Wuthnow1999) also found a difference between Mainline Protestant congregations (such as Lutheran churches) and Evangelical Protestant congregations in how often they volunteer. Wuthnow (Reference Wuthnow1999) found that religious groups with a more Manichean world view such as Evangelicals in the USA tended to be less civically engaged, and if they are civically engaged, the engagement most often is limited to their religious congregation. Wuthnow (Reference Wuthnow1999) pointed to the fact that Evangelical congregations mostly encouraged their members to volunteer for activities related to their congregations. Similarly, Vermeer and Scheepers (Reference Vermeer and Scheepers2012) using Dutch panel data found that a strict practice of religion within a family (labelled as religious orthodoxy) during upbringing was negatively correlated with volunteering for secular organizations later in life. A very strong commitment toward the own religious congregation seemed to constrict the likelihood of volunteering for a secular organization (Vermeer & Scheepers, Reference Vermeer and Scheepers2012). A more fundamentalist view on religion does also correspond with less prosocial values, such as social trust, that are correlated with volunteering also within the Swedish context (Wallman Lundåsen & Trägårdh, Reference Wallman Lundåsen, Trägårdh, De Hart, Dekker and Halman2013), while on the other hand, a less dogmatic view on religion may better function as a bridge between the religious community and the secular organizational life (Wallman Lundåsen & Trägårdh, Reference Wallman Lundåsen, Trägårdh, De Hart, Dekker and Halman2013).

Previous studies of Nordic countries have found a positive correlation between religious services attendance and volunteering (Grizzle & Yusuf, Reference Grizzle and Yusuf2015). These findings have been interpreted as religion promoting prosocial values and being an incubator of civic skills that also promote participation in politics (Grizzle & Yusuf, Reference Grizzle and Yusuf2015). Sweden has a strong Protestant heritage; the Lutheran Christian Church of Sweden historically played the role of state church and still occupies a dominant position in comparison with other religious congregations in Sweden (Klingenberg, Reference Klingenberg2019). Therefore, values associated with Lutheranism should be briefly discussed. An important aspect is the Lutheran idea of two kingdoms, the secular and the divine, as it asks the devout to be engaged in the betterment of their society (Deifelt, Reference Deifelt2010). A core Lutheran value is that belief is supposed to manifest in action (von Essen & Grosse, Reference Von Essen and Grosse2019; Rasmusson, Reference Rasmusson2007). The devout should facilitate their neighbors’ well-being and therefore engage in volunteering and political advocacy, especially on behalf of disadvantaged groups (Deifelt, Reference Deifelt2010). Moreover, studies have argued that the ideas of Lutheranism especially promote forms of giving that help the poor to become independent through work or ensure that those unable to work have a minimum standard of living (Nelson, Reference Nelson2017).

Berger (Reference Berger2006) argued that certain groups experience social barriers that make volunteering and charitable giving more difficult, and that religious involvement may lower these barriers. Knowledge about whether someone was actively recruited is also needed to have a fuller picture of why certain groups are more or less civically engaged than others (Dekker & Halman, Reference Dekker, Halman, Dekker and Halman2003).

Religious Participation, Social Networks, and Civic Engagement

As described above, the religious participation–civic engagement link could also be driven by the fact that those who actively participate in religious services belong to social networks (Teorell, Reference Teorell2003), and these social networks could be tied to secular forms of involvement. Studies have also consistently found that those who volunteer, in general, participate in politics more frequently (Verba et al. Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). This finding was confirmed by studies using Swedish data that showed a correlation between volunteering and participation in politics (von Essen & Wallman Lundåsen, Reference Von Essen and Wallman Lundåsen2015). Outside the USA, studies (e.g., Strømsnes, Reference Strømsnes2008) have found that those who often attend religious services and are members of a religious congregation in Norway also tend to be slightly more politically active. Forms of political participation preferred by those who often attend religious services include engaging in political parties, donating money to organizations and causes, and various forms of activism, such as signing petitions and participating in political activist groups (Strømsnes, Reference Strømsnes2008). Studies of Swedish youth showed that those who consider themselves religiously devout are more likely to be civically engaged (Poljarevic et al., Reference Poljarevic, Karlsson Minganti and Klingenberg2019). The devout is more likely to be involved in volunteer organizations than others and ranks their personal political efficacy higher compared to others (Poljarevic et al., Reference Poljarevic, Karlsson Minganti and Klingenberg2019).

Returning to the role played by social networks, scholars have argued the importance of religious congregations having either mostly close ties within the group (bonding) or connections through social networks to the broader community (bridging) (Putnam, Reference Putnam2000; Wuthnow, Reference Wuthnow1999; Yeung, Reference Yeung2004). The still-most-dominant congregation, the Church of Sweden, like other Protestant churches (see, e.g., Wuthnow, Reference Wuthnow1999), has had, and continues to have, ties with the local communities in which the church operates also through its organizational structure (described in the next section).

The social networks that form during religious services attendance can then also function as sources of recruitment and encouragement of other forms of engagement (Teorell, Reference Teorell2003; Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). According to Schlozman et al. (Reference Schlozman, Verba, Brady, Skocpol and Fiorina1999) and Brady et al. (Reference Brady, Schlozman and Verba1999), it is reasonable to assume that those who attempt to recruit others to participate in forms of civic engagement likely operate within a rational framework, in which they try to maximize the likelihood of a positive response when asking others to join. Therefore, the connection between religious involvement and participation in politics could also be driven by the likelihood of receiving requests for other forms of participation through social networks linked to religious participation (cf. Teorell, Reference Teorell2003; Brady et al., Reference Brady, Schlozman and Verba1999).

In line with Teorell’s (Reference Teorell2003) proposed mechanism, those who often attend religious services could be regarded by others as having qualities that make them more attractive to recruit as volunteers, such as dependability and loyalty. In sum, we can expect from previous research on the role of values and social networks that those who attend religious services are more civically engaged, while the scope of the civic engagement remains uncertain.

Religious Involvement in the Case of Sweden

Analyzing the role of religious participation in the Nordic context is not without difficulty. Sweden ranks among the most secularized countries in the world (de Hart et al., Reference De Hart, Dekker and Halman2013; Delhey & Newton, Reference Delhey and Newton2005), and in 2000, the Church of Sweden was formally separated from the central state, ending a nearly 500-year union. Historically, the Church of Sweden cared for the poor before the expansion of the welfare state but also carried out bureaucratic tasks, such as maintaining the population register until the early 1990s. Mostly due to the church’s history as a state church, the Church of Sweden boasts about 6.1 million members (in a population of about 10 million) due to membership being automatic when it was a state church. Studies have indicated that secularization continues in Sweden at the societal, organizational, and individual levels (Hagevi, Reference Hagevi2012). These processes are visible, such as the decreased role of the Lutheran Christian faith in school curricula; lower shares of the population choosing religious rites of passage for themselves or their children, such as christenings and church weddings; and lower shares of the population who declare themselves religious (Klingenberg, Reference Klingenberg2019). Finding a correlation between religious attendance and civic engagement in Sweden can be considered a tough empirical test, as the overall levels of civic engagement in Sweden, as in the other Scandinavian countries even alongside with an extensive welfare state, remain high in comparison with those of other countries (Henriksen et al., Reference Henriksen, Strømsnes, Svedberg, Henriksen and Svedberg2019).

Data from the European Values Study (2017) show that a clear majority (more than 65%) of those who report being members of the Church of Sweden consider religion either not important or not at all important in their lives. Previous studies show that church attendance in general declined from the mid-1950 to 2000s (Granberg & Persson, Reference Granberg and Persson2013). However, the share of the population that reports religious services attendance has been stable from the 1990s and onwards (Klingenberg, Reference Klingenberg2019). Studies have found that those who attend church with some frequency are more likely to vote than those who report that they never attend church (Granberg & Persson, Reference Granberg and Persson2013). In general, religious issues are part of the private sphere and not part of the daily political debate in Sweden (Hagevi, Reference Hagevi2012).

The organization of the Church of Sweden is governed by political parties as a result of an organizational reform in 1930 (Claesson, 2004). In practice, the “secular” day-to-day operations within the parishes were separated from religious ceremonies operated by the clergy. This reform enabled democratic governing of parishes by their members through the introduction of a mandatory elected parish council. The list of candidates for the parish council typically comprises members of political parties. It remains, however, an open question whether religious participation in the Swedish context can be considered a mostly private matter, with few links to other forms of civic engagement, or whether it is linked to other forms of civic engagement (Poljarevic et al. Reference Poljarevic, Karlsson Minganti and Klingenberg2019; von Essen & Grosse, Reference Von Essen and Grosse2019; Yeung, Reference Yeung2004).

Data and Methods

This study uses data from the 2014 and 2019 Swedish national surveys on volunteering. The survey was conducted by phone among a national random sample of inhabitants of Sweden. The survey targeted persons in the 16- to 84-year-old age range. In total, 2366 individuals participated in the surveys, with a response rate of about 56% in 2014 and 56% in 2019. The 2014 and 2019 surveys were the fifth and sixth waves of the national survey of volunteering that was carried out since 1992 on behalf of Ersta Sköndal Bräcke University College and administered by the companies Markör (in the year 2014) and Origo (in the year 2019).

The dependent variables that operationalized civic engagement in the analyses are volunteering, charitable giving, and political participation. The concept of volunteering in the surveys includes a broad spectrum of tasks performed on a voluntary basis (unpaid or paid only a token amount) for a civil society organization at least once during the previous 12 months. The types of activities listed are administrative duties, including small practical tasks; leading an activity (e.g., a sports coach, leader of a Scout group, or other similar role); public relations and communication; helping others (e.g., through home visits, counseling, or other related activities); fundraising; education; serving as a member of the board of administrators of the organization; and other (unspecified) activities. Given the wide range of activities included, the intensity of the level of activity may vary a great deal among respondents. The dependent variable volunteering was operationalized as having volunteered during the past 12 months (1 = yes and no = 0) for a civil society organization irrespective of the type of organization. Volunteering was asked about for a wide range of civil society organizations.

Volunteering for religious organizations listed five different types of religious organizations and an “other” category that covered religious organizations that were not mentioned. These items included volunteering for organizations related to the following religions: the Lutheran Church of Sweden, non-conformist/Evangelical, Roman Catholicism/Catholic Orthodox, Islam, and other religions. However, the sample was heavily skewed toward volunteering for Christian religious organizations. Only two and three respondents reported volunteering for a non-Christian religious organization on the 2014 and 2019 surveys, respectively. In practice, volunteering for a religious organization means volunteering for a Christian organization. In addition, charitable giving during the previous 12 months was included as a dependent variable (1 = donated and 0 = did not donate).

The other dependent variable, political participation, was measured as having performed (yes = 1 and no = 0) one of the following types of activities during the previous 12 months: signing a petition, participating in a boycott, participating in a peaceful demonstration, contacting a civil servant to influence him or her on a societal issue, contacting a politician to influence him or her on a societal issue, and volunteering for a political party (Teorell et al., Reference Teorell, Torcal, Montero, van Deth, Montero and Westholm2007).

The key independent variable, religious participation, was measured as religious services attendance using the question: “Independent of whether you are affiliated with a particular religion, how often do you attend religious services? Please exclude attending religious ceremonies during christenings, weddings, funerals, and similar.” The question had four response options: “weekly or more often,” “at least monthly,” “several times a year,” and “seldom or never.” In the following analyses, the response “weekly or more often” is combined with “at least monthly” and coded as 1, and “several times a year” and “seldom or never” are coded as 0.

In these multivariate analyses, several control variables were introduced based on previous studies that alluded to the importance of demographic and socioeconomic factors and values such as social trust regarding volunteering (Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995; Wollebæk & Selle, Reference Wollebaek and Selle2002; Wollebæk & Selle, Reference Wollebæk and Selle2007; von Essen et al., Reference von Essen, Jegermalm and Svedberg2015). These variables included the following: (1) demographic variables, such as gender (male = 1), age (in years), and location of residence (metropolitan area or rural/small community coded as 1), having children living at home (having children living at home with the respondent coded as 1); (2) socioeconomic variables such as income (income above 375,000 SEK/year coded as 1; all other levels below coded as 0), education (post-secondary studies coded as 1; all other levels of education coded as 0), a homeowner, including owning a condominium (coded as 1; not owning a home coded as 0), and employed or a student (being employed or being a student coded as 1; unemployed or not a student coded as 0); and (3) values regarding volunteering tapped through two different survey items (“Everybody has a duty to volunteer at least once,” scale: 1 (disagrees completely) to 4 (agrees completely), “Volunteering helps people to have an active role in democracy,” scale: 1 (disagrees completely) to 4 (agrees completely)). The broad value of social trust is tapped through a standard survey item (“most people who can be trusted” coded as 1; “one cannot be too careful when dealing with others” coded as 0).

Requests to participate was the sum of every time a respondent answered that they became volunteers because of requests to volunteer. This question was asked as a follow-up question for every organization for which the respondent had volunteered. (The sum varies between 0 and 6, with a mean value of 0.5.) Data regarding the summed requests to volunteer were only available in the 2014 survey.

The data were pooled and analyzed with multivariate logistic regression that controlled for years and used clustered standard errors for the years in the regression models, thus controlling for autocorrelation. The coefficients in the regression models are presented as odds ratios. As the magnitude of coefficients varies with the number of variables in logistic regression models, all the models contain the same number of variables. To facilitate the interpretations of results, marginal probabilities of interest are presented graphically.

Results

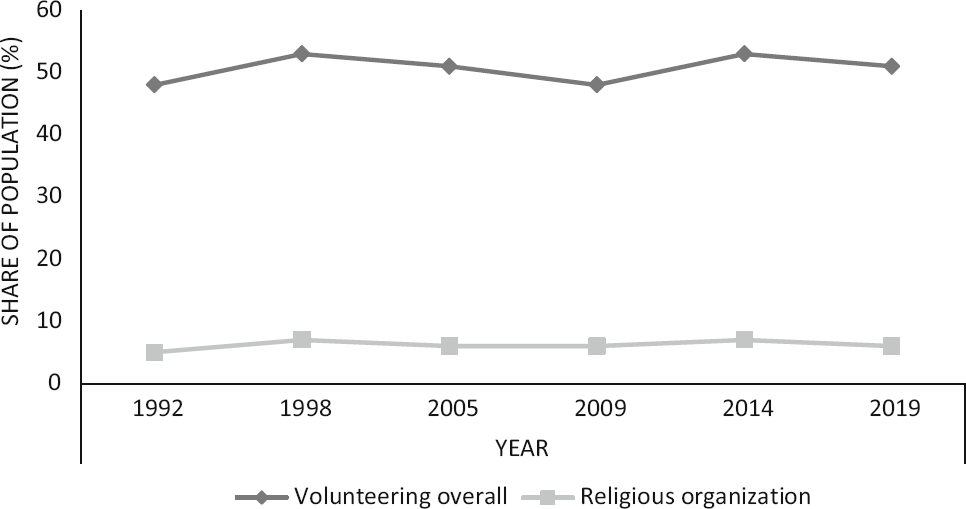

First, volunteering, as a phenomenon, must be put into a broader empirical context. A substantial share of the academic debate about contemporary civil society and volunteering in Western democracies has dealt with the notion of decreasing levels of volunteering (most notably Putnam, Reference Putnam2000). The argument regarding lower levels of citizen participation, however, found little empirical support in the Swedish data. The share of citizens age 16–85 years who were involved in volunteering connected to civil society organizations remained stable, at around an average of 50%, from 1992 to 2014 (see also Qvisth et al., Reference Qvisth, Folkestad, Fridberg, Wallman Lundåsen, Henriksen and Svedberg2019). This level of stability is remarkable considering that Sweden underwent several important political and economic changes during this time period such as the separation between the Lutheran Church of Sweden and the state. An important explanation for the stability in the overall volunteering rates is the increasing share of the population with higher levels of education, as those with higher levels of education, in general, are more likely to volunteer (Qvisth et al., Reference Qvisth, Folkestad, Fridberg, Wallman Lundåsen, Henriksen and Svedberg2019). Over the years, the share who volunteers for religious organizations, with the exception of small shifts in 1992 and 2014, has remained stable, even though the dominant Lutheran Church since the year 2000 no longer is a state church.

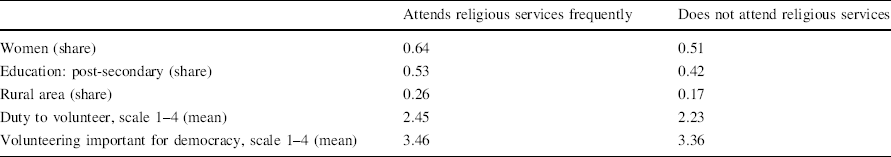

The characteristics of the respondents who attended religious services frequently compared to those who did not are shown in Table 1. In sum, this group resembles those who tend to be religiously more active in other countries (DeHart et al., Reference De Hart, Dekker and Halman2013); that is, they are more often female, are a bit older, and more often live in rural areas. In the Swedish case, this group also, on average, has slightly higher levels of education. This group also more often agrees that everybody has a duty to volunteer at least once and slightly more often agrees that volunteering plays an important role in providing citizens an active role in a democratic society. All in all, those who participate in religious services share some characteristics (e.g., education, living in rural areas) that enhance the likelihood of volunteering, while other aspects such as gender (being more female) would decrease the likelihood to volunteer (Fig. 1).

Table 1 Descriptive statistics according to religious attendance, t tests

Attends religious services frequently |

Does not attend religious services |

|

|---|---|---|

Women (share) |

0.64 |

0.51 |

Education: post-secondary (share) |

0.53 |

0.42 |

Rural area (share) |

0.26 |

0.17 |

Duty to volunteer, scale 1–4 (mean) |

2.45 |

2.23 |

Volunteering important for democracy, scale 1–4 (mean) |

3.46 |

3.36 |

All differences are statistically significant, p < 0.05, t test

Fig. 1 Volunteering overall and volunteering for religious organizations (1992–2019).

The first research question enquired whether people actively practiced religion through participation in religious ceremonies and whether they were more likely to volunteer. The question also enquired whether those who were religiously active volunteered for other than religious organizations. As shown in Table 1, those who are religiously active lean toward having more of the characteristics previously known to increase the likelihood of volunteering (e.g., education, age, and living in a rural area; Qvisth et al., Reference Qvisth, Folkestad, Fridberg, Wallman Lundåsen, Henriksen and Svedberg2019).

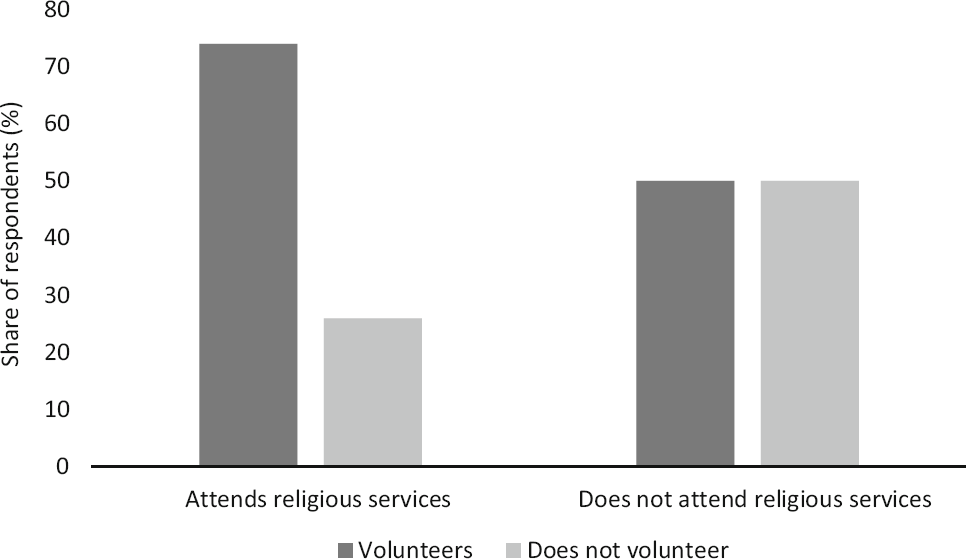

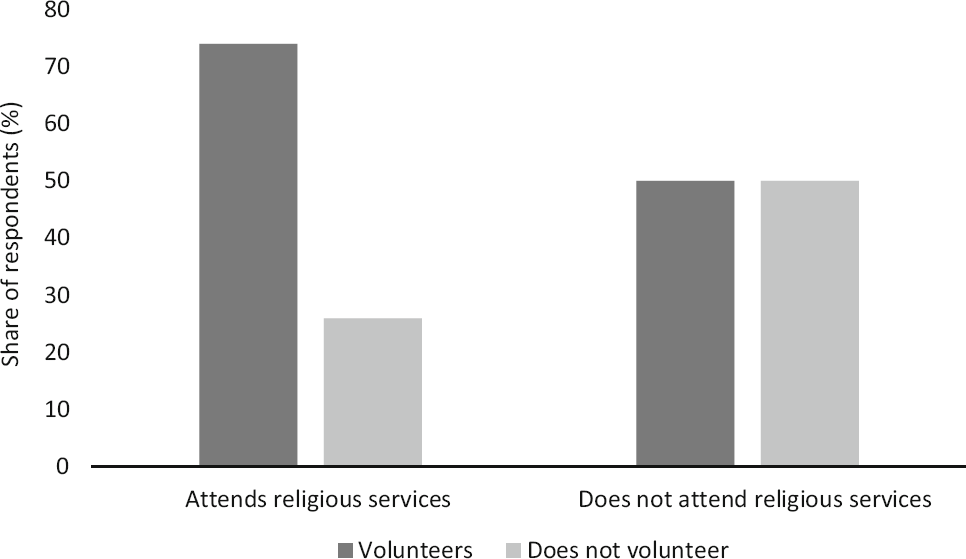

Figure 2 shows the statistically significantly higher likelihood of volunteering among those who attend religious services with some frequency and compared to those who seldom or never attend. Volunteering occurs statistically significantly less frequently among those who never attend religious services (50% compared to 74% among those who often attend religious services, p < 0.00, χ 2 = 40.31, N = 2,146). This result is in line with several other studies of various contexts that found a similar pattern (de Hart et al., Reference De Hart, Dekker and Halman2013; Grizzle & Yusuf, Reference Grizzle and Yusuf2015).

Fig. 2 Attending religious services and volunteering (survey 2014 and 2019).

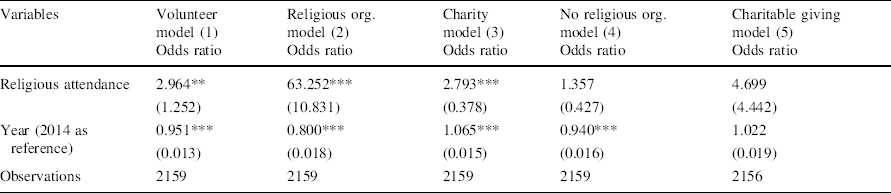

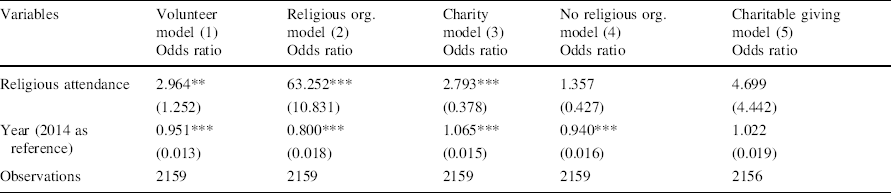

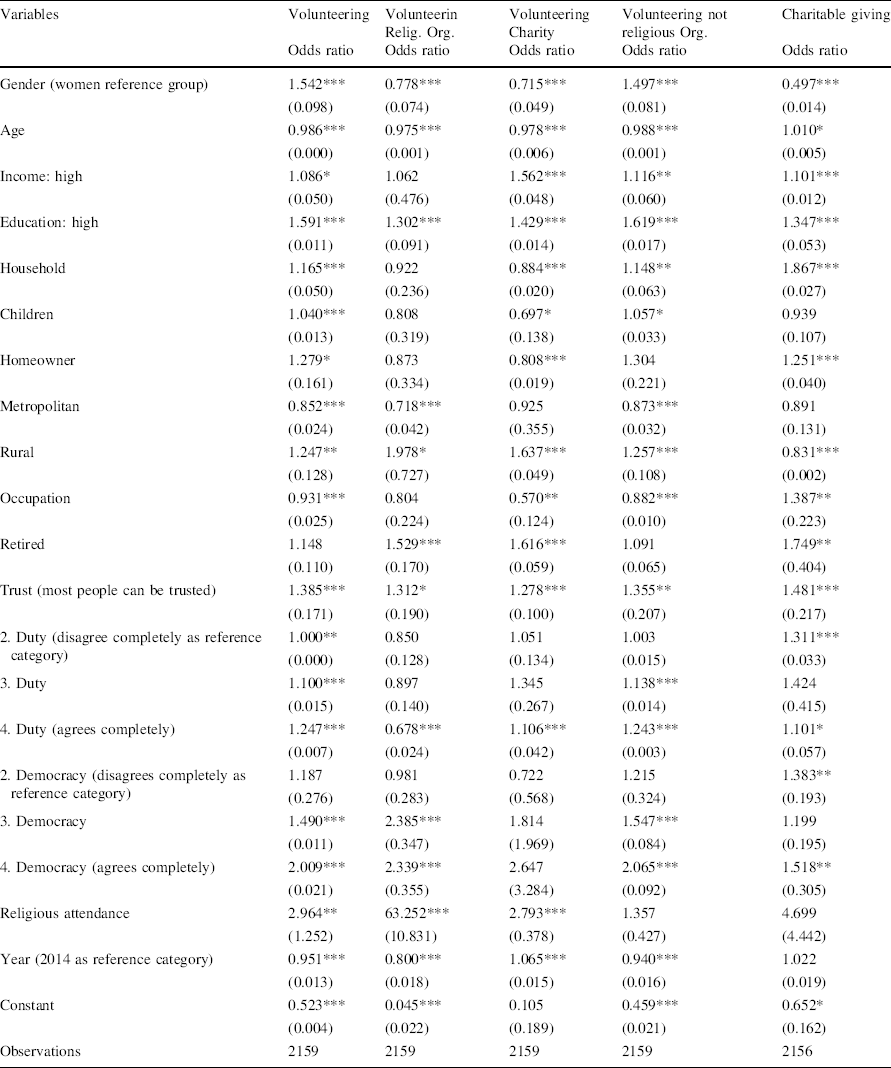

When other variables are controlled for, the multivariate logistic regression results in Table 2 show that those who attend religious services frequently tend to volunteer more frequently compared to those who do not. The table shows that those who attend religious services frequently have an increased likelihood of volunteering that corresponds to more than twice than the odds ratio of those who do not attend religious services regularly. It also shows that attending religious services is the single most important factor in Model 1 that increases the odds ratio for volunteering.

Table 2 Religious attendance and civic engagement, logistic regression analysis, odds ratios with robust standard errors in parentheses

Variables |

Volunteer model (1) |

Religious org. model (2) |

Charity model (3) |

No religious org. model (4) |

Charitable giving model (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Odds ratio |

Odds ratio |

Odds ratio |

Odds ratio |

Odds ratio |

|

Religious attendance |

2.964** |

63.252*** |

2.793*** |

1.357 |

4.699 |

(1.252) |

(10.831) |

(0.378) |

(0.427) |

(4.442) |

|

Year (2014 as reference) |

0.951*** |

0.800*** |

1.065*** |

0.940*** |

1.022 |

(0.013) |

(0.018) |

(0.015) |

(0.016) |

(0.019) |

|

Observations |

2159 |

2159 |

2159 |

2159 |

2156 |

Robust standard errors in parentheses, ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05

Socioeconomic, demographic, and values are controlled for, and coefficients are not displayed for reasons of space. Models with all the coefficients in “Appendix”

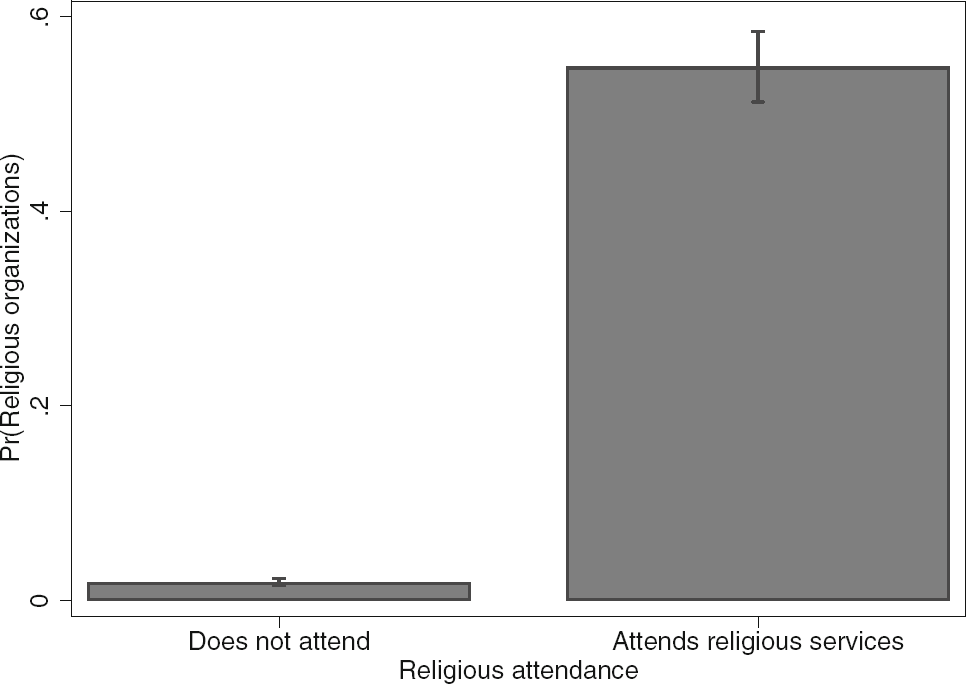

Of those who reported regular religious services attendance, about 56% also reported that they volunteered for a religious organization or congregation. As Table 2 shows, those who are religiously active are likely to volunteer for religious congregations or other religiously affiliated organizations. The likelihood of volunteering for a religious organization increased 63-fold among those who attended religious services (Table 2, Model 3).

Figure 3 shows that the marginal likelihood of volunteering for a religious organization is close to zero among those who did not attend religious services with some frequency.

Fig. 3 Predicted marginal probability of volunteering for a religious organization, 95% confidence intervals. Model as in Table 2. Keeping all of the variables at their mean values

The survey maps volunteering activity for more than 30 categories of organizations, covering a very broad spectrum of civil society organizations in Sweden. In Table 2, another category, other than religious organizations, stands out, namely charities and antidrug or temperance organizations. The odds ratio of volunteering for a charity organization is slightly less than threefold among those who often attend religious services compared to those who did not (Model 3). However, the general relationship between religious attendance and volunteering outside religious organizations (Model 4) is not statistically significant. This result indicates that much of the volunteering done by this group is tied to religious organizations. Moreover, the results show that those who attend religious services frequently have a higher likelihood of also doing some form of charitable giving, but the difference is not statistically significant. The marginal predicted likelihood is around 0.95 among those who attend religious services, meaning that only around 5% in this group, all other things being equal, are predicted to not having done any charitable giving.

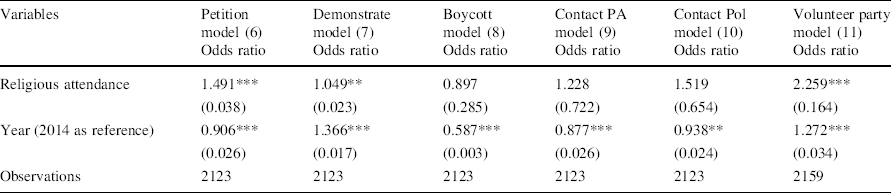

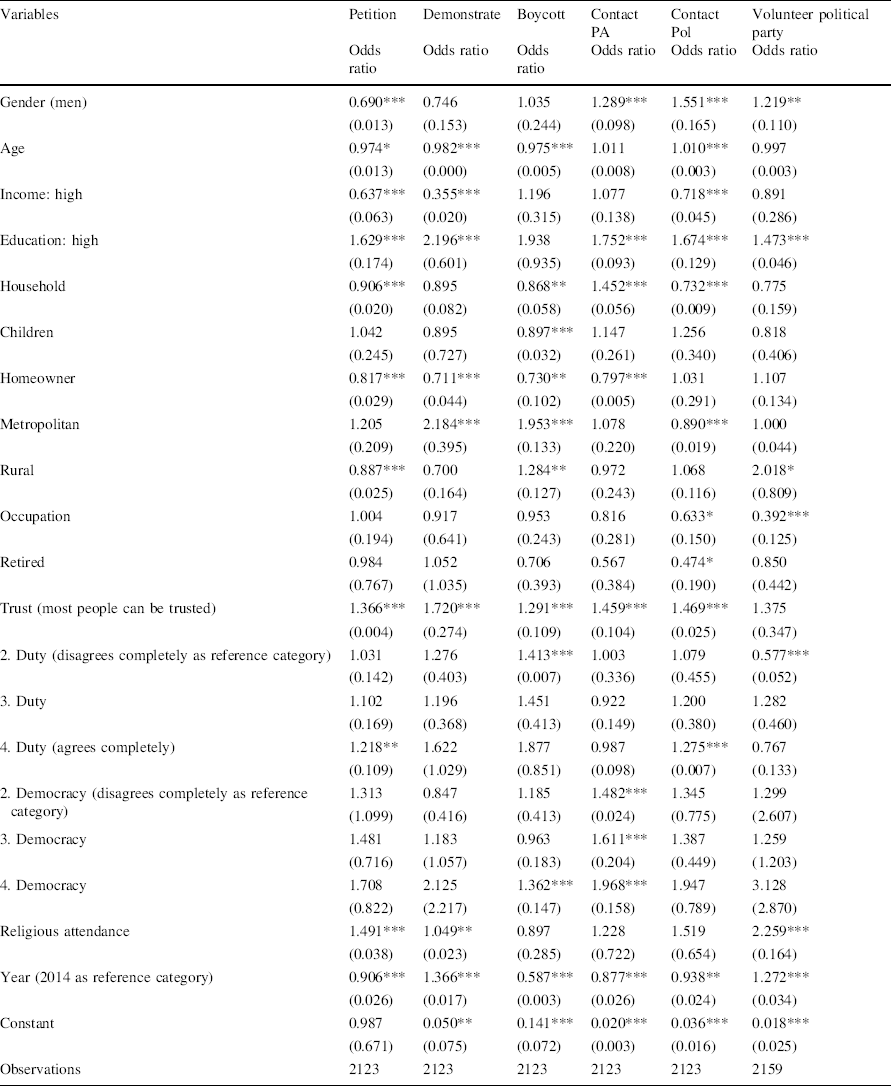

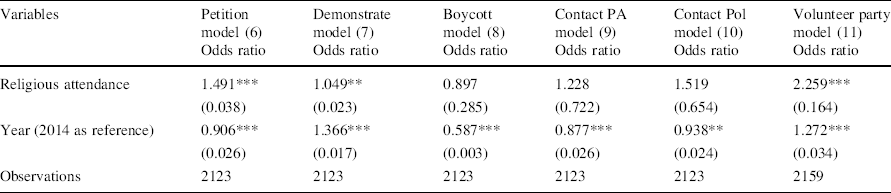

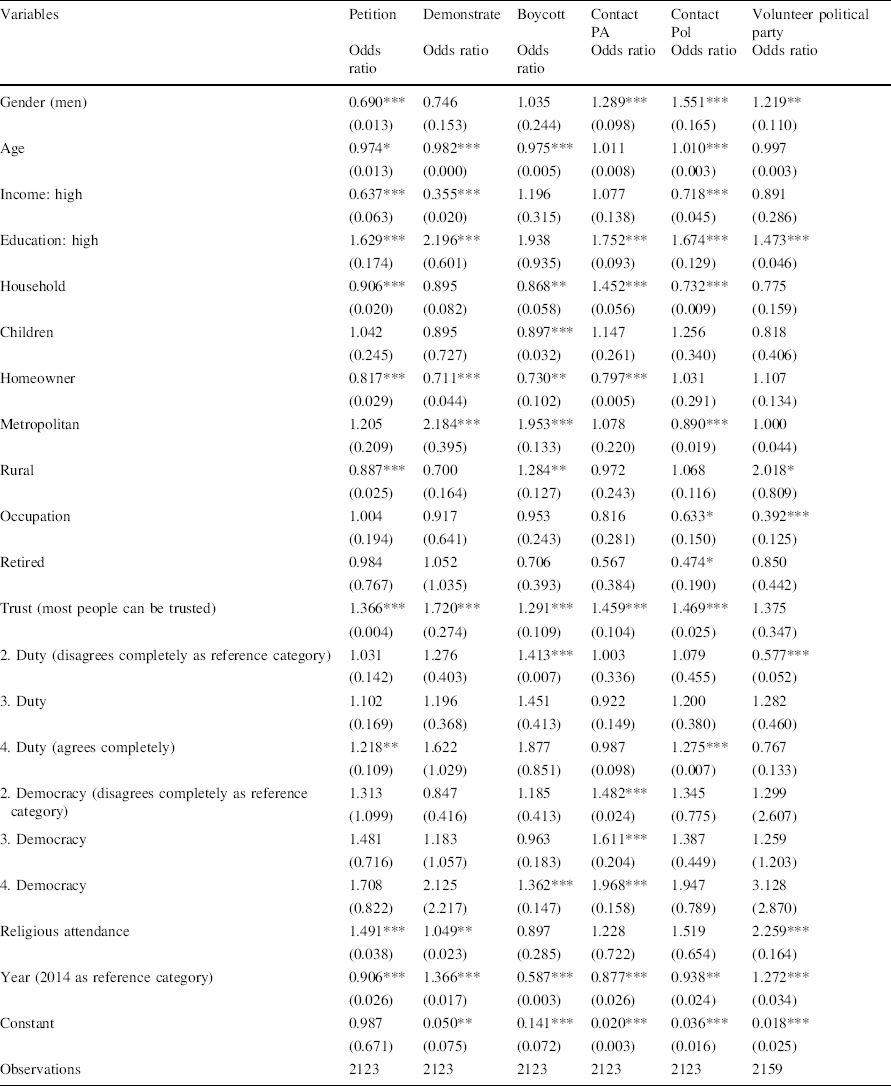

The second research question concerned the extent to which those who were religiously active in Sweden participated in politics outside elections. Table 3 illustrates the relationship between religious participation and various forms of participation in politics, including volunteering for a political party.

Table 3 Religious attendance and political participation, logistic regression, odds ratios with robust standard errors in parentheses

Variables |

Petition model (6) |

Demonstrate model (7) |

Boycott model (8) |

Contact PA model (9) |

Contact Pol model (10) |

Volunteer party model (11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Odds ratio |

Odds ratio |

Odds ratio |

Odds ratio |

Odds ratio |

Odds ratio |

|

Religious attendance |

1.491*** |

1.049** |

0.897 |

1.228 |

1.519 |

2.259*** |

(0.038) |

(0.023) |

(0.285) |

(0.722) |

(0.654) |

(0.164) |

|

Year (2014 as reference) |

0.906*** |

1.366*** |

0.587*** |

0.877*** |

0.938** |

1.272*** |

(0.026) |

(0.017) |

(0.003) |

(0.026) |

(0.024) |

(0.034) |

|

Observations |

2123 |

2123 |

2123 |

2123 |

2123 |

2159 |

Robust standard errors in parentheses, ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05

Socioeconomic, demographic, and values are controlled for, and coefficients are not displayed for reasons of space. Models with all the coefficients in “Appendix”

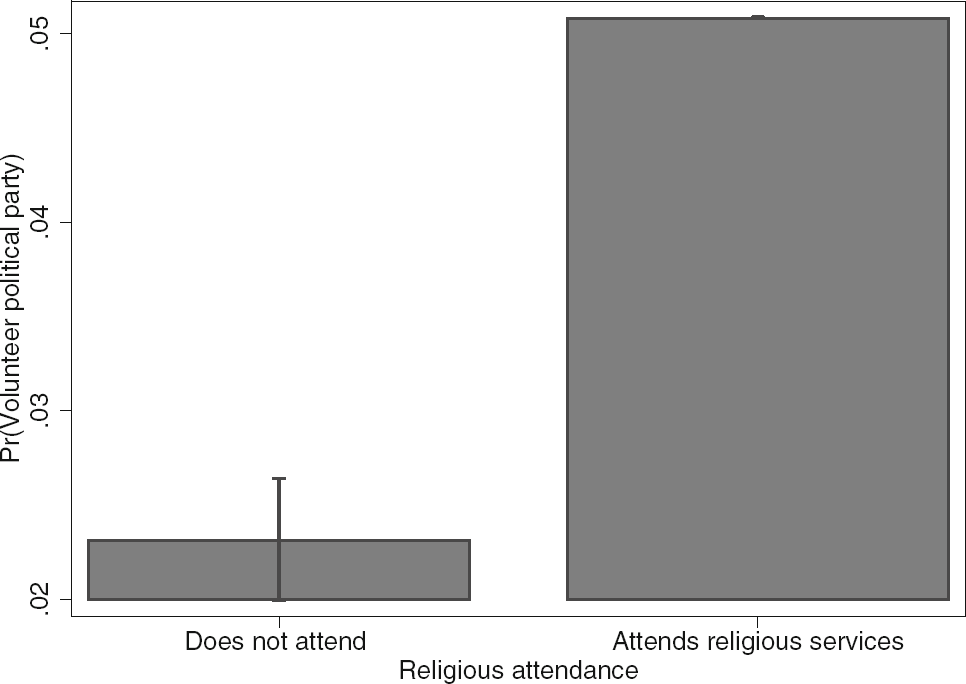

Table 3 shows that religious participation is significantly correlated with three different forms of participation in politics: petitioning, demonstrating, and volunteering for a political party. The largest odds ratio among those who attended religious services frequently is found on the variable volunteering for a political party. The group who frequently attended religious services was more than twice as likely to become volunteers for a political party than those who seldom attend religious services (Table 3, Model 11). Figure 4 shows the marginal likelihood of volunteering for a political party between those who regularly or seldom or never attend religious services.

Fig. 4 Predicted marginal probability of volunteering for a political party, 95% confidence intervals. Model as in Table 3. Keeping all of the variables at their mean values

The predicted likelihood of signing a petition was around 0.36 among those who attended religious services frequently, but it is 0.27 among those who did not; this difference is statistically significant. The correlation between religious services attendance and participation in political demonstrations is statistically significant, but the difference in the marginal likelihood of participating in political demonstrations between those who were religiously active and those who were not is close to zero. The relatively strong overrepresentation of those who attended religious services within political parties is in line with similar findings regarding the patterns of involvement of those who are active within older Protestant congregations, where these groups do not seem to be particularly mobilized politically, other than a higher propensity to work for political parties and political candidates (Wuthnow, Reference Wuthnow1999).

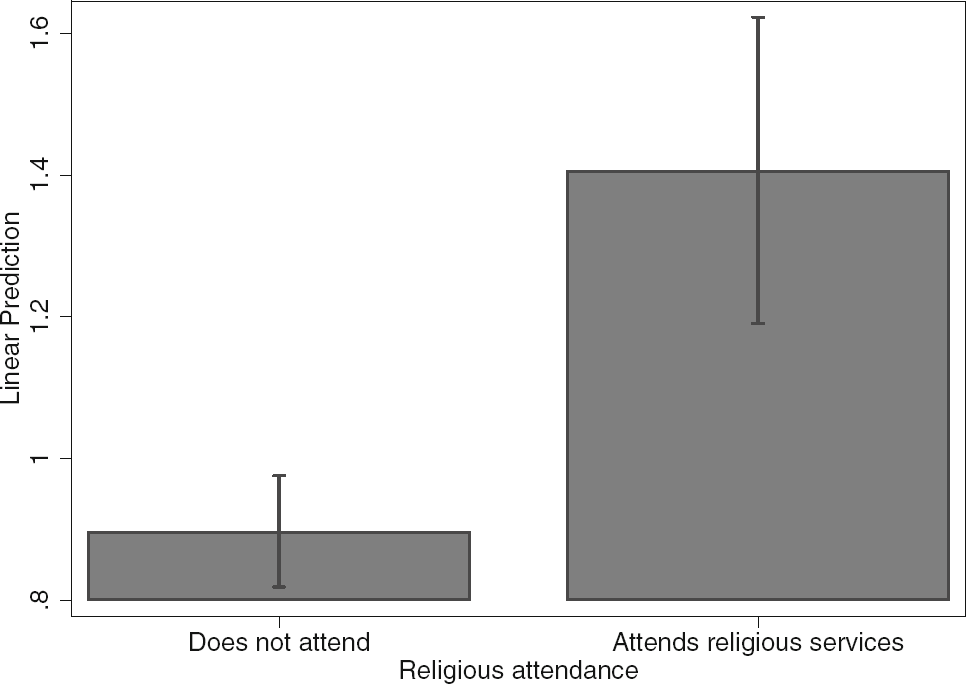

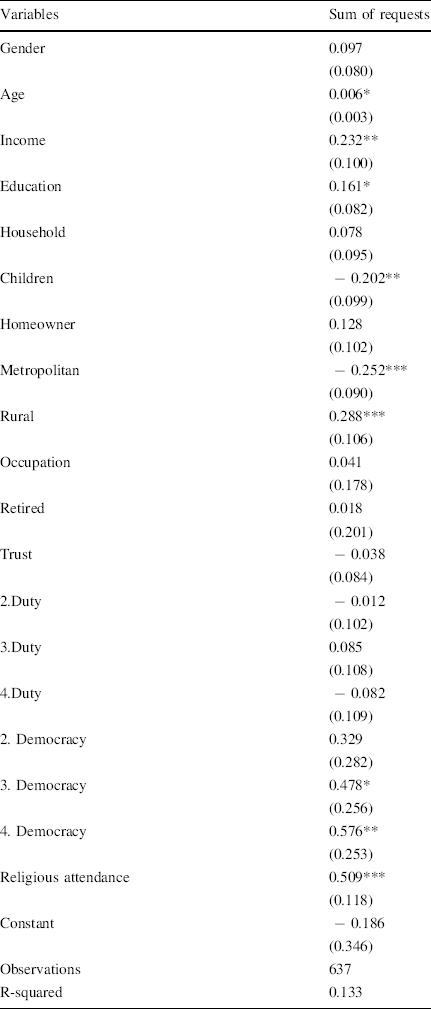

The third research question asked whether those who attended religious services regularly received more requests to volunteer elsewhere. Only data from 2014 could be used due to changes in the questionnaires between the two rounds of data collection. Regarding the propensity of receiving requests to volunteer in general, the results show that, on average, about 48% of those who regularly attended religious services received at least one request to volunteer for a civil society organization, and 28% received requests to volunteer for two or more different civil society organizations. Conversely, among those who did not regularly attend religious services, about 33% received at least one request to volunteer, but only 8% received requests to volunteer for two or more different civil society organizations. The difference between those who frequently participated in religious services and others is statistically significant (χ 2 = 53.76, p < 0.000). Figure 5 shows the predicted margins of receiving requests to volunteer while controlling for socioeconomic and demographic variables, and values. Those who frequently attended religious services were estimated to receive 1.41 requests to volunteer, while those who did not attend religious services frequently were predicted to receive 0.90 requests to volunteer (full model in “Appendix”).

Fig. 5 Predicted linear marginal probability of receiving requests to volunteer, 95% confidence intervals. Model in “Appendix”

These results show that social networks are important for receiving requests to participate in other groups (Brady et al., Reference Brady, Schlozman and Verba1999; Teorell, Reference Teorell2003). By participating in religious services, individuals belong to social networks that likely expose the individuals to requests to volunteer; moreover, being religiously active may make them more attractive among those who seek to recruit others (Strømsnes, Reference Strømsnes2008; Teorell, Reference Teorell2003; Yeung, Reference Yeung2004). However, it may be difficult to distinguish the impact of values from the impact of social networks (i.e., receiving requests to volunteer). There is an overlap between attending religious services frequently and a higher tendency to agree with it being a duty to volunteer at least once, and to agree that volunteering contributes to having an active role in a democratic society. Notwithstanding, in the analysis above receiving requests to volunteer seemed to outweigh the importance of values in the regression analysis among those who volunteered for political parties.

Conclusions

The present study aimed to investigate the link between religious services attendance and civic engagement within the Swedish context. As asserted by others (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart2021), inhabitants of many countries are becoming less religious. The present study results may be relevant for other countries that are moving in a similar direction, although the role played by religious congregations may vary across cultural contexts. The Church of Sweden carries the heritage of being a former state church and its Lutheran theology promoting the idea that religious belief ought to manifest itself in action. An important limitation of this study is that Sweden has, during the previous decades, become more religiously diverse (Klingenberg, Reference Klingenberg2019), mostly through immigration, but the results relate to Protestant Christian forms of religious participation. In line with previous studies (Poljarevic et al., Reference Poljarevic, Karlsson Minganti and Klingenberg2019), the analyses showed that religious services attendance is positively correlated with the propensity to volunteer for a civil society organization in Sweden. Religious participation matters, even if the average share of the population who volunteers in Sweden is high (Qvisth et al., Reference Qvisth, Folkestad, Fridberg, Wallman Lundåsen, Henriksen and Svedberg2019). Therefore, religious services attendance withstood a tough empirical test.

However, volunteering among those who regularly attended religious services was, in general, limited to a small group of organizations. Religious and charitable organizations are where those who more frequently attend religious services most often volunteer, in line with previous studies of Protestant denominations (Yeung, Reference Yeung2017). Although the link between religious participation and volunteering for a religious organization was expected, the link between religious services attendance and volunteering for charitable organizations could be found in the theological interpretation that emphasizes the importance of religion as doing good for others (Deifelt, Reference Deifelt2010), and in the historical ties between the Church of Sweden and charitable organizations (Lundkvist, Reference Lundkvist1977). The findings indicate that these ties exist at the individual level, even within a highly developed welfare state and a secular context. Those who attend religious services frequently were not statistically significantly more likely to make charitable donations compared to those who did not attend religious services frequently. This could be explained by that fact that the general level of charitable giving in the data set was very high (around 80%). Overall, attending religious services in a country like Sweden, where religion is mostly regarded as a private matter (Hagevi, Reference Hagevi2012), seems to include the participants in a social fabric that extends to, albeit limited in type, civil society organizations. In the Swedish context, the choice of civil society organizations where the religiously active volunteer stands out, as it differs from the type of organizations that usually attract the largest share of volunteers such as leisure organizations like sports and hobby organizations (Qvisth et al., Reference Qvisth, Folkestad, Fridberg, Wallman Lundåsen, Henriksen and Svedberg2019).

The second research question investigated the extent to which those who reported regular attendance at religious services more or less participated in politics compared with others. What stands out especially is the higher propensity among those who regularly attend religious services to volunteer more often for political parties. One possible interpretation could be the logical consequence of the organizational structure of the Church of Sweden, with its democratically elected councils, in which political parties are traditionally represented. However, active engagement in a political party is likely to extend beyond church-related contexts, as the political parties often rely on their volunteers to help with campaigning in, for example, national and local elections. Given that those who regularly attend religious services are a minority of the population in Sweden, they are overrepresented among those who volunteer for political parties. This finding replicates the pattern found in studies showing that political representatives in the national parliament are more religiously active than the population in general (Granberg & Persson, Reference Granberg and Persson2013). This result poses questions regarding social representation, even at the grassroots level within Swedish political parties, where religiously active citizens are more likely to be engaged as volunteers for political parties in this secular context. Moreover, those who attended religious services regularly also more often signed petitions than others. Although the regression analysis results indicate that those who regularly attended religious services also more often participated in demonstrations, the difference was hardly substantial. Country comparative empirical studies are needed to fully grasp the role of country-level institutions, such as the heritage of a state church.

The empirical results presented above indicate that in Sweden, the religiously active seems to demonstrate several similarities with those who are active in Protestant churches in other European contexts (Strømsnes, Reference Strømsnes2008; Vermeer & Scheepers, Reference Vermeer and Scheepers2012). This may be interpreted as supporting a cultural reading of the importance of religious attendance, in which those who are religiously involved in similar religions tend to share some views on how civically engaged they are supposed to be in their communities.

The third question concerned whether those who attended religious services regularly received more requests to volunteer than others. Given that the survey also asked how the respondents became involved as volunteers, this question offered the opportunity to open slightly the black box of the link between attending religious services and volunteering. When asked how they started to volunteer for a specific organization, those who frequently attended church responded, statistically significantly more often than those who attended religious services seldom or never, that it was because they were asked or invited to volunteer by someone else. Thus, the results can be interpreted as substantiating theories that emphasize the importance of receiving requests, or being asked, to volunteer (Brady et al., Reference Brady, Schlozman and Verba1999; Strømsnes, Reference Strømsnes2008; Teorell, Reference Teorell2003; Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995; Yeung, Reference Yeung2004). By attending religious services, participants are more exposed to being asked or invited to participate as volunteers. Although those who regularly attended religious services tended to volunteer for a limited group of civil society organizations, it seems likely that by attending religious services, they were exposed to more frequent requests to volunteer than those who did not. As noted by other scholars, it is difficult to disentangle the importance of networks from values (Teorell, Reference Teorell2003). Those who are religiously active tend to be more willing to agree that everybody has a duty to volunteer, and that volunteering makes citizens have an active role in a democracy. These values coupled with receiving requests to volunteer could explain the higher propensity to volunteer among those who are religiously active. At the same time, the presence of these values may also make this group more attractive among those who recruit volunteers, thus indicating a possible mutual and reinforcing relationship between values and requests (Teorell, Reference Teorell2003). However, this interpretation must be further tested with other types of data.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Linköping University.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no project funding and no conflicts of interest.

Informed Consent

The respondents in the data gave their informed consent to participate in the survey for the purpose of research. All the data are stored without any information that makes it possible to identify the respondents according to Swedish and European Union regulations of data protection and privacy. Due to regulations of data protection, it is not possible to store the data publicly.

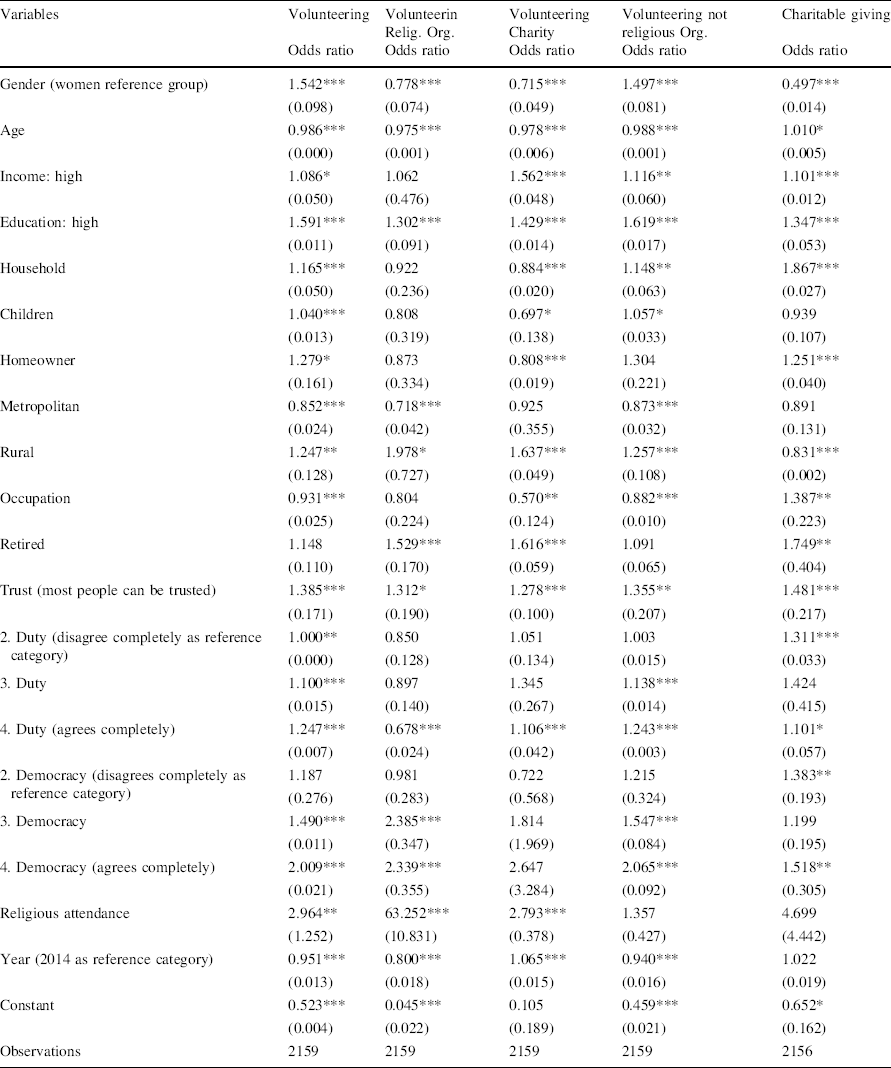

Appendix

Table 4 Religious attendance, different forms of volunteering and charitable giving as dependent variables (full models), logistic regression, odds ratios with robust standard errors in parentheses

Variables |

Volunteering |

Volunteerin Relig. Org. |

Volunteering Charity |

Volunteering not religious Org. |

Charitable giving |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Odds ratio |

Odds ratio |

Odds ratio |

Odds ratio |

Odds ratio |

|

Gender (women reference group) |

1.542*** |

0.778*** |

0.715*** |

1.497*** |

0.497*** |

(0.098) |

(0.074) |

(0.049) |

(0.081) |

(0.014) |

|

Age |

0.986*** |

0.975*** |

0.978*** |

0.988*** |

1.010* |

(0.000) |

(0.001) |

(0.006) |

(0.001) |

(0.005) |

|

Income: high |

1.086* |

1.062 |

1.562*** |

1.116** |

1.101*** |

(0.050) |

(0.476) |

(0.048) |

(0.060) |

(0.012) |

|

Education: high |

1.591*** |

1.302*** |

1.429*** |

1.619*** |

1.347*** |

(0.011) |

(0.091) |

(0.014) |

(0.017) |

(0.053) |

|

Household |

1.165*** |

0.922 |

0.884*** |

1.148** |

1.867*** |

(0.050) |

(0.236) |

(0.020) |

(0.063) |

(0.027) |

|

Children |

1.040*** |

0.808 |

0.697* |

1.057* |

0.939 |

(0.013) |

(0.319) |

(0.138) |

(0.033) |

(0.107) |

|

Homeowner |

1.279* |

0.873 |

0.808*** |

1.304 |

1.251*** |

(0.161) |

(0.334) |

(0.019) |

(0.221) |

(0.040) |

|

Metropolitan |

0.852*** |

0.718*** |

0.925 |

0.873*** |

0.891 |

(0.024) |

(0.042) |

(0.355) |

(0.032) |

(0.131) |

|

Rural |

1.247** |

1.978* |

1.637*** |

1.257*** |

0.831*** |

(0.128) |

(0.727) |

(0.049) |

(0.108) |

(0.002) |

|

Occupation |

0.931*** |

0.804 |

0.570** |

0.882*** |

1.387** |

(0.025) |

(0.224) |

(0.124) |

(0.010) |

(0.223) |

|

Retired |

1.148 |

1.529*** |

1.616*** |

1.091 |

1.749** |

(0.110) |

(0.170) |

(0.059) |

(0.065) |

(0.404) |

|

Trust (most people can be trusted) |

1.385*** |

1.312* |

1.278*** |

1.355** |

1.481*** |

(0.171) |

(0.190) |

(0.100) |

(0.207) |

(0.217) |

|

2. Duty (disagree completely as reference category) |

1.000** |

0.850 |

1.051 |

1.003 |

1.311*** |

(0.000) |

(0.128) |

(0.134) |

(0.015) |

(0.033) |

|

3. Duty |

1.100*** |

0.897 |

1.345 |

1.138*** |

1.424 |

(0.015) |

(0.140) |

(0.267) |

(0.014) |

(0.415) |

|

4. Duty (agrees completely) |

1.247*** |

0.678*** |

1.106*** |

1.243*** |

1.101* |

(0.007) |

(0.024) |

(0.042) |

(0.003) |

(0.057) |

|

2. Democracy (disagrees completely as reference category) |

1.187 |

0.981 |

0.722 |

1.215 |

1.383** |

(0.276) |

(0.283) |

(0.568) |

(0.324) |

(0.193) |

|

3. Democracy |

1.490*** |

2.385*** |

1.814 |

1.547*** |

1.199 |

(0.011) |

(0.347) |

(1.969) |

(0.084) |

(0.195) |

|

4. Democracy (agrees completely) |

2.009*** |

2.339*** |

2.647 |

2.065*** |

1.518** |

(0.021) |

(0.355) |

(3.284) |

(0.092) |

(0.305) |

|

Religious attendance |

2.964** |

63.252*** |

2.793*** |

1.357 |

4.699 |

(1.252) |

(10.831) |

(0.378) |

(0.427) |

(4.442) |

|

Year (2014 as reference category) |

0.951*** |

0.800*** |

1.065*** |

0.940*** |

1.022 |

(0.013) |

(0.018) |

(0.015) |

(0.016) |

(0.019) |

|

Constant |

0.523*** |

0.045*** |

0.105 |

0.459*** |

0.652* |

(0.004) |

(0.022) |

(0.189) |

(0.021) |

(0.162) |

|

Observations |

2159 |

2159 |

2159 |

2159 |

2156 |

*p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01

Table 5 Religious attendance and different forms of political participation (full models), logistic regression, odds ratios with robust standard errors in parentheses

Variables |

Petition |

Demonstrate |

Boycott |

Contact PA |

Contact Pol |

Volunteer political party |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Odds ratio |

Odds ratio |

Odds ratio |

Odds ratio |

Odds ratio |

Odds ratio |

|

Gender (men) |

0.690*** |

0.746 |

1.035 |

1.289*** |

1.551*** |

1.219** |

(0.013) |

(0.153) |

(0.244) |

(0.098) |

(0.165) |

(0.110) |

|

Age |

0.974* |

0.982*** |

0.975*** |

1.011 |

1.010*** |

0.997 |

(0.013) |

(0.000) |

(0.005) |

(0.008) |

(0.003) |

(0.003) |

|

Income: high |

0.637*** |

0.355*** |

1.196 |

1.077 |

0.718*** |

0.891 |

(0.063) |

(0.020) |

(0.315) |

(0.138) |

(0.045) |

(0.286) |

|

Education: high |

1.629*** |

2.196*** |

1.938 |

1.752*** |

1.674*** |

1.473*** |

(0.174) |

(0.601) |

(0.935) |

(0.093) |

(0.129) |

(0.046) |

|

Household |

0.906*** |

0.895 |

0.868** |

1.452*** |

0.732*** |

0.775 |

(0.020) |

(0.082) |

(0.058) |

(0.056) |

(0.009) |

(0.159) |

|

Children |

1.042 |

0.895 |

0.897*** |

1.147 |

1.256 |

0.818 |

(0.245) |

(0.727) |

(0.032) |

(0.261) |

(0.340) |

(0.406) |

|

Homeowner |

0.817*** |

0.711*** |

0.730** |

0.797*** |

1.031 |

1.107 |

(0.029) |

(0.044) |

(0.102) |

(0.005) |

(0.291) |

(0.134) |

|

Metropolitan |

1.205 |

2.184*** |

1.953*** |

1.078 |

0.890*** |

1.000 |

(0.209) |

(0.395) |

(0.133) |

(0.220) |

(0.019) |

(0.044) |

|

Rural |

0.887*** |

0.700 |

1.284** |

0.972 |

1.068 |

2.018* |

(0.025) |

(0.164) |

(0.127) |

(0.243) |

(0.116) |

(0.809) |

|

Occupation |

1.004 |

0.917 |

0.953 |

0.816 |

0.633* |

0.392*** |

(0.194) |

(0.641) |

(0.243) |

(0.281) |

(0.150) |

(0.125) |

|

Retired |

0.984 |

1.052 |

0.706 |

0.567 |

0.474* |

0.850 |

(0.767) |

(1.035) |

(0.393) |

(0.384) |

(0.190) |

(0.442) |

|

Trust (most people can be trusted) |

1.366*** |

1.720*** |

1.291*** |

1.459*** |

1.469*** |

1.375 |

(0.004) |

(0.274) |

(0.109) |

(0.104) |

(0.025) |

(0.347) |

|

2. Duty (disagrees completely as reference category) |

1.031 |

1.276 |

1.413*** |

1.003 |

1.079 |

0.577*** |

(0.142) |

(0.403) |

(0.007) |

(0.336) |

(0.455) |

(0.052) |

|

3. Duty |

1.102 |

1.196 |

1.451 |

0.922 |

1.200 |

1.282 |

(0.169) |

(0.368) |

(0.413) |

(0.149) |

(0.380) |

(0.460) |

|

4. Duty (agrees completely) |

1.218** |

1.622 |

1.877 |

0.987 |

1.275*** |

0.767 |

(0.109) |

(1.029) |

(0.851) |

(0.098) |

(0.007) |

(0.133) |

|

2. Democracy (disagrees completely as reference category) |

1.313 |

0.847 |

1.185 |

1.482*** |

1.345 |

1.299 |

(1.099) |

(0.416) |

(0.413) |

(0.024) |

(0.775) |

(2.607) |

|

3. Democracy |

1.481 |

1.183 |

0.963 |

1.611*** |

1.387 |

1.259 |

(0.716) |

(1.057) |

(0.183) |

(0.204) |

(0.449) |

(1.203) |

|

4. Democracy |

1.708 |

2.125 |

1.362*** |

1.968*** |

1.947 |

3.128 |

(0.822) |

(2.217) |

(0.147) |

(0.158) |

(0.789) |

(2.870) |

|

Religious attendance |

1.491*** |

1.049** |

0.897 |

1.228 |

1.519 |

2.259*** |

(0.038) |

(0.023) |

(0.285) |

(0.722) |

(0.654) |

(0.164) |

|

Year (2014 as reference category) |

0.906*** |

1.366*** |

0.587*** |

0.877*** |

0.938** |

1.272*** |

(0.026) |

(0.017) |

(0.003) |

(0.026) |

(0.024) |

(0.034) |

|

Constant |

0.987 |

0.050** |

0.141*** |

0.020*** |

0.036*** |

0.018*** |

(0.671) |

(0.075) |

(0.072) |

(0.003) |

(0.016) |

(0.025) |

|

Observations |

2123 |

2123 |

2123 |

2123 |

2123 |

2159 |

*p < 0.10; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01

Table 6 Number of received requests to volunteer among volunteers as dependent variable, OLS regression

Variables |

Sum of requests |

|---|---|

Gender |

0.097 |

(0.080) |

|

Age |

0.006* |

(0.003) |

|

Income |

0.232** |

(0.100) |

|

Education |

0.161* |

(0.082) |

|

Household |

0.078 |

(0.095) |

|

Children |

− 0.202** |

(0.099) |

|

Homeowner |

0.128 |

(0.102) |

|

Metropolitan |

− 0.252*** |

(0.090) |

|

Rural |

0.288*** |

(0.106) |

|

Occupation |

0.041 |

(0.178) |

|

Retired |

0.018 |

(0.201) |

|

Trust |

− 0.038 |

(0.084) |

|

2.Duty |

− 0.012 |

(0.102) |

|

3.Duty |

0.085 |

(0.108) |

|

4.Duty |

− 0.082 |

(0.109) |

|

2. Democracy |

0.329 |

(0.282) |

|

3. Democracy |

0.478* |

(0.256) |

|

4. Democracy |

0.576** |

(0.253) |

|

Religious attendance |

0.509*** |

(0.118) |

|

Constant |

− 0.186 |

(0.346) |

|

Observations |

637 |

R-squared |

0.133 |

Standard errors in parentheses

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1