Introduction

Allocapnia pygmaea (Burmeister) is a winter stonefly (Plecoptera: Capniidae) distributed in North America and is notable for its winter-active adult stage (Hilsenhoff Reference Hilsenhoff, Thorph and Covich2001). Little is documented about its life as it transitions from an aquatic nymph to a terrestrial adult in winter and early spring, other than its ability to crawl through ice crevices and walk on top of snow (Moore and Lee Reference Moore and Lee1991). Although the effect of low temperature on survival has been partially characterised in adult A. pygmaea in Minnesota, United States of America (Bouchard et al. Reference Bouchard, Schuetz, Ferrington and Kells2009), the limits to their activity at low temperatures and the mechanisms underlying their cold tolerance have not been studied.

Low temperatures (e.g., near or below 0 °C) impair the activity and survival of insects in multiple ways. As environmental temperature decreases, insects will first lose neuromuscular function (ability to move) at a species-specific critical thermal minimum (CTmin) temperature (Overgaard and MacMillan Reference Overgaard and MacMillan2017). Their internal fluids will then freeze at the supercooling point temperature (Sinclair et al. Reference Sinclair, Alvarado and Ferguson2015), which may be equal to (e.g., Schoville et al. Reference Schoville, Slatyer, Bergdahl and Valdez2015; Toxopeus et al. Reference Toxopeus, Lebenzon, McKinnon and Sinclair2016) or below (e.g., Clarke et al. Reference Clarke, Thompson and Sinclair2013) the CTmin. Although freeze-tolerant insects survive internal freezing (e.g., Ramløv et al. Reference Ramløv, Bedford and Leader1992), freeze-avoidant species do not (e.g., Schoville et al. Reference Schoville, Slatyer, Bergdahl and Valdez2015; Golding et al. Reference Golding, Rupp, Sustar, Pratt and Tuthill2023). The lowest temperature an insect can survive (i.e., its lower lethal temperature) is equal to the supercooling point for freeze-avoidant insects, below the supercooling point for freeze-tolerant insects, and above the supercooling point for chill-susceptible insects (Sinclair et al. Reference Sinclair, Alvarado and Ferguson2015).

Low-molecular-weight cryoprotectants are important for both freeze avoidance and freeze tolerance and can fulfil different functions (Overgaard and MacMillan Reference Overgaard and MacMillan2017; Toxopeus and Sinclair Reference Toxopeus and Sinclair2018). Insects may accumulate cryoprotectants either before or in response to cold stress. Increased concentrations of cryoprotectants depress the insect’s supercooling point, which is a key mechanism for freeze-avoidant insects to prevent internal ice formation (Feng et al. Reference Feng, Xu, Li, Xu, Cao and Wang2016; Toxopeus and Sinclair Reference Toxopeus and Sinclair2018). Cryoprotectants may also directly protect cells and their macromolecules from challenges associated with low temperatures and freezing (Teets and Denlinger Reference Teets and Denlinger2013; Toxopeus et al. Reference Toxopeus, Koštál and Sinclair2019). During its nymph stage, a freeze-tolerant stonefly, Nemoura arctica Esben-Petersen (Plecoptera: Nemouridae), continuously produces glycerol while frozen (Walters et al. Reference Walters, Sformo, Barnes and Duman2009). Many cryoprotectants (trehalose, glucose, proline, and glycerol) are also metabolites that can be broken down to facilitate ATP production (Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Borchardt and Wang2003; Toxopeus et al. Reference Toxopeus, Koštál and Sinclair2019; Jørgensen et al. Reference Jørgensen, Hansen, Willot and Overgaard2023). To our knowledge, the cryoprotective biochemistry of A. pygmaea has not previously been described.

In the present study, we characterise the activity and survival of field-collected A. pygmaea at subzero temperatures and report concentrations of common insect cryoprotectants, improving our understanding of how an adult winter-emerging stonefly survives Nova Scotian winters.

Methods

We collected adult A. pygmaea from Antigonish, Nova Scotia, Canada (45.62 °N, – 62.00 °W) in the spring (March to April) of 2023 and 2024 from the walls of a residence near Brierly Brook, a mid-sized stream. Using a paintbrush, we gently transferred insects into 50-mL Falcon tubes containing moist paper towels, transported them inside a cooler with ice packs to St. Francis Xavier University (Antigonish, Nova Scotia), and housed them in a 4-°C refrigerator within an hour of collection. Allocapnia pygmaea destined for cryoprotectant assays were flash-frozen and stored in a –80-°C freezer, whereas A. pygmaea destined for whole-animal experiments remained in the 4-°C fridge for 3–7 days. We weighed stoneflies with an XPR2 microbalance (Mettler Toledo, Columbus, Ohio, United States of America) before the manipulations described below.

To determine CTmin of A. pygmaea, we cooled eight stoneflies (2024 collection) from 4 °C at –0.25 °C/minute to –12 °C in individual transparent chambers and classified stonefly activity every five minutes using the same equipment described for measuring CTmin in Adams et al. (Reference Adams, Chettiar, Clow, Gendron, Gough and Stewart2025a). Stoneflies were classified as active if they were clearly motile or maintaining an upright position on the wall of the observation chamber. They were classified as inactive if they had fallen to the bottom of the observation chamber. Two stoneflies never fell to the bottom of the chamber but remained in the same position on the tube wall for more than 100 minutes (appeared “stuck”) and therefore were excluded. We defined CTmin as the temperature at which each stonefly first became inactive and remained so for at least three observation periods. We tested whether CTmin varied as a function of stonefly mass using a linear regression in R, version 4.2.2 (R Project; available at https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/old/4.4.2/).

To determine the supercooling point, cold tolerance strategy, and survival following acute cold shock, we exposed stoneflies to low temperatures in individual containers using the same equipment described in Adams et al. (Reference Adams, van Oirschot and Toxopeus2025b). To measure the supercooling point, 28 stoneflies (2023 collection) were cooled from 4 °C to –20 °C at –0.25 °C/minute. We then tested whether the supercooling point varied as a function of stonefly mass using a linear regression in R, version 4.2.2. To determine the cold tolerance strategy, stoneflies (2023 collection) were cooled from 4 °C at –0.25 °C/minute to a temperature (approximately –11.5 °C) at which half of them (7 of 16) had frozen and the remaining stoneflies were unfrozen. We inferred a cold tolerance strategy based on the survival of these two groups after 24 hours at 4 °C (Sinclair et al. Reference Sinclair, Alvarado and Ferguson2015). To determine their ability to survive acute cold shocks and further verify the cold tolerance strategy, we exposed groups of seven or eight stoneflies (2024 collection) for 60 minutes to one of five temperatures ranging from approximately –5 °C to –11.5 °C (encompassing 0 to 100% mortality) and then assessed survival after 24 hours at 4 °C. Stoneflies were classified as alive if they could move or respond to a gentle physical stimulus (touching with a paintbrush) when returned to room temperature.

We determined the concentrations of five putative cryoprotectants in whole-body homogenates of A. pygmaea (2024 collection) via spectrophotometric assays. Each stonefly was homogenised individually with a plastic pestle in 100 µL of Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 5 mM Tris; 137 mM NaCl; 2.7 mM KCl, pH 6.6). We centrifuged homogenates for five minutes at 3000× g and 4 °C. We then centrifuged 100 µL of supernatant for 30 minutes at 3000× g and 4 °C. Supernatants were aliquoted into 1.7-mL tubes for subsequent cryoprotectant assays. We began proline assays immediately after centrifugation, following Carillo and Gibon (Reference Carillo and Gibon2011). The remaining heat-treated (70 °C for 10 minutes) aliquots were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80 °C for up to three weeks before processing. We used the K-INOSL and K-GCROLGK kits (Megazyme, Bray, Ireland) to assay myo-inositol and glycerol, respectively, following the manufacturer’s instructions. For trehalose and glucose, we followed Tennesen et al. (Reference Tennesen, Barry, Cox and Thummel2014), using porcine trehalase and glucose assay reagent (Sigma Aldrich, Toronto, Ontario, Canada). For all assays, we performed a twofold dilution series to produce a standard curve. To read absorbances, we used a SpectraMax iD3 (Molecular Devices, San Jose, California, United States of America) spectrophotometer. We compared cryoprotectant concentrations in 16 field-collected stoneflies and in eight that were cold-shocked at –4.9 °C for one hour, using analysis of covariance tests, with mass as a covariate, in R, version 4.2.2.

Results and discussion

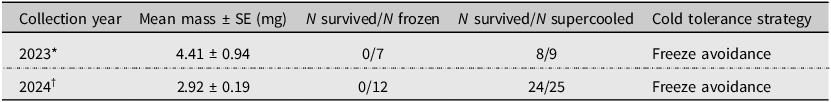

We showed that A. pygmaea were active at subzero temperatures but did not survive freezing, demonstrating freeze avoidance. Six stoneflies remained active until they froze, with a CTmin between –7.3 and –10.2 °C (Fig. 1A). This is similar to some other winter-active insects that also retain neuromuscular function until they freeze (e.g., Schoville et al. Reference Schoville, Slatyer, Bergdahl and Valdez2015; Toxopeus et al. Reference Toxopeus, Lebenzon, McKinnon and Sinclair2016). In a separate trial, we found that the supercooling point of the stoneflies ranged from –6.0 °C to –15.0 °C (Fig. 1A), with a mean (–11.9 °C) similar to that of the same species studied in Minnesota, United States of America (Bouchard et al. Reference Bouchard, Schuetz, Ferrington and Kells2009). Neither CTmin (F 1,4 = 0.002, P = 0.967) nor supercooling point (F 1,24 = 0.18, P = 0.673) correlated with mass. Although the Minnesota study suggested A. pygmaea may be chill-susceptible (Bouchard et al. Reference Bouchard, Schuetz, Ferrington and Kells2009), our work indicates that they are cold-tolerant and can survive temperatures near their supercooling point as long as internal freezing does not occur (Table 1). When we gradually cooled stoneflies to a temperature at which half froze and half remained unfrozen, all frozen individuals died, whereas all unfrozen individuals survived (Table 1). When stoneflies were exposed to subzero temperatures for longer (one hour), all frozen individuals died, and almost all (96%) unfrozen individuals survived, regardless of the specific temperature (Fig. 1B). These cold tolerance parameters suggest A. pygmaea are freeze-avoidant and can remain active and survive at temperatures they are likely to experience in their environment. For example, in March 2024, air temperatures in Antigonish ranged between –12.8 °C and 8.4 °C (Environment Canada 2024), and the lowest temperatures could be avoided by moving to warmer microenvironments (closer to 0 °C) under snow. Future research may address whether males and females exhibit differences in cold tolerance parameters, as Bouchard et al. (Reference Bouchard, Schuetz, Ferrington and Kells2009) observed minor sex-based differences in supercooling point.

Figure 1. Cold tolerance of Allocapnia pygmaea collected in Antigonish, Nova Scotia, Canada, in spring 2023 and 2024: A, critical thermal minimum (CTmin) and supercooling point (SCP) – for each interquartile range, the middle line indicates the median, the top represents the first quartile, the bottom represents the third quartile, and X indicates the mean; B, proportion of stoneflies alive or dead following a one-hour exposure to one of five low temperatures. Each stonefly was categorised based on whether it remained supercooled (unfrozen) or froze during the temperature treatment and whether it survived or died within 24 hours following the treatment.

Table 1. Cold tolerance strategy of Allocapnia pygmaea from Antigonish, Nova Scotia, Canada, after cooling (2023 collection) or cold shock (2024 collection). N, number of stoneflies; SE, standard error

* All stoneflies were cooled to –11.5 °C.

† Data were summarised from multiple temperatures (see Fig. 1B).

Other insects that are winter-active or survive in low-temperature environments demonstrate diverse cold tolerance strategies. Similar to A. pygmaea, insects of the genera Chionea Dalman (Diptera: Tipulidae) and Grylloblatta Walker (Grylloblattodea: Grylloblattidae) are winter-active and freeze-avoidant (Schoville et al. Reference Schoville, Slatyer, Bergdahl and Valdez2015; Golding et al. Reference Golding, Rupp, Sustar, Pratt and Tuthill2023). They inhabit alpine environments with variable temperature ranges but seek out microclimates as low as –3 °C. Snow flies (Chionea) continue to move at temperatures as low as –10 °C and may even resort to self-amputation of limbs to avoid lethal freezing (Golding et al. Reference Golding, Rupp, Sustar, Pratt and Tuthill2023). Other winter-active insects are freeze-tolerant, including Hemideina maori Pictet et Saussure (Orthoptera: Stenopelmatidae) of New Zealand’s mountain habitats (Ramløv et al. Reference Ramløv, Bedford and Leader1992; Sinclair et al. Reference Sinclair, Worland and Wharton1999) and nymphs of the Arctic stonefly, Nemoura arctica (Plecoptera: Nemouridae) (Walters et al. Reference Walters, Sformo, Barnes and Duman2009). Although cold tolerance has not yet been investigated in A. pygmaea’s nymph stage, it may differ from the adult’s freeze avoidance.

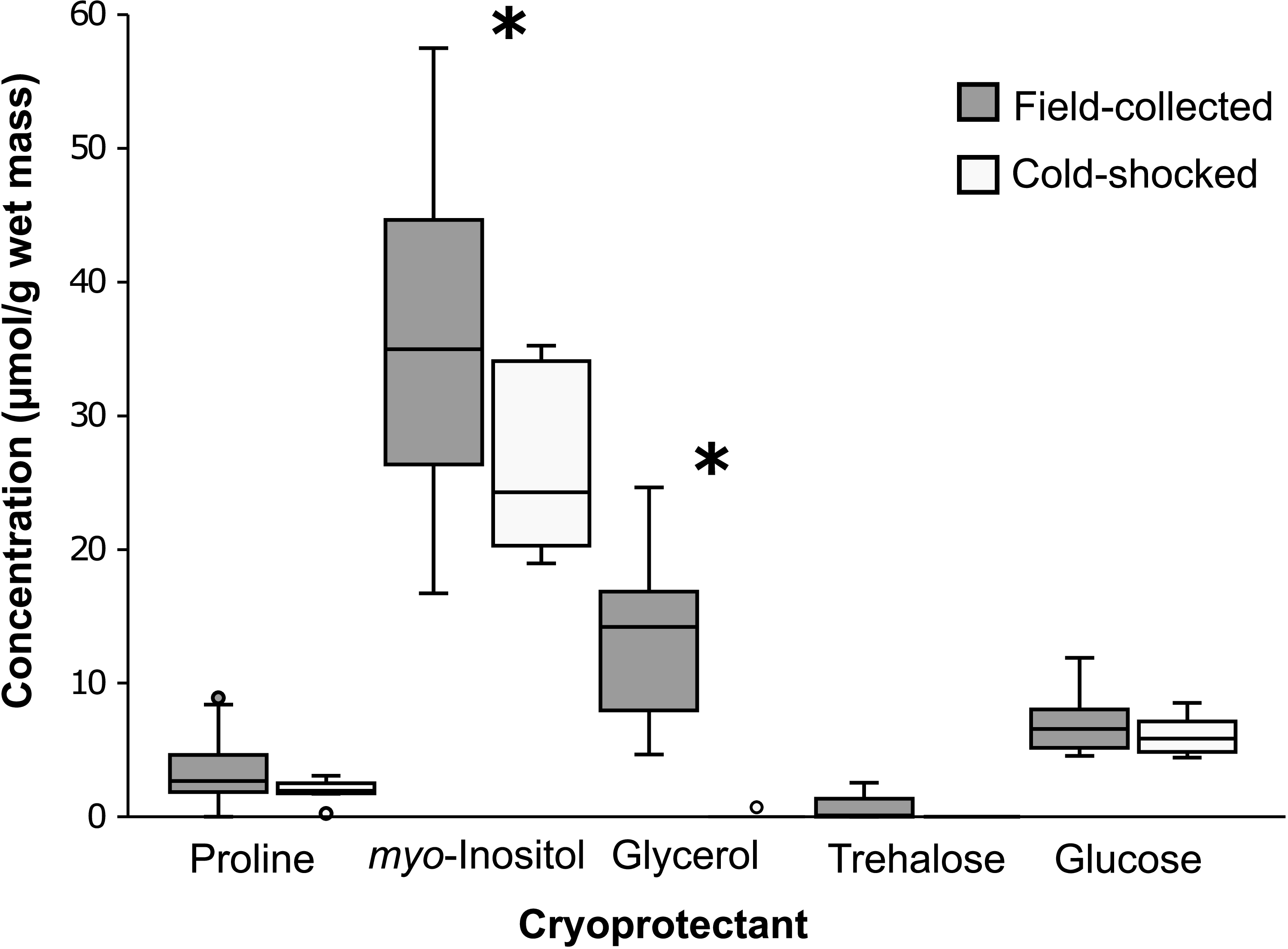

In our assessment of putative cryoprotectants, the most abundant cryoprotectant in field-collected stoneflies was myo-inositol, followed by glycerol, sugars, and proline (Fig. 2). The concentration of myo-inositol (∼40 µmol/g) was at least threefold higher than any other metabolite we measured. myo-Inositol is a less commonly reported cryoprotectant in insect cold tolerance literature, with some exceptions (e.g., Vesala et al. Reference Vesala, Salminen, Koštál, Zahradníčková and Hoikkala2012; Toxopeus et al. Reference Toxopeus, Koštál and Sinclair2019; Štětina et al. Reference Štětina, Kučera, Moos, Rozsypal and Koštál2025). Glycerol (∼15 µmol/g) was the second-most abundant cryoprotectant in our tested samples. This differs from Walters et al.’s (Reference Walters, Sformo, Barnes and Duman2009) findings for freeze-tolerant Arctic stonefly nymphs, whose primary cryoprotectant is glycerol, which accumulates when the insects are frozen. Trehalose, glucose, and proline had the lowest concentrations (< 10 µmol/g) in our tested A. pygmaea, which is congruent with work on N. arctica nymphs showing that they have detectable but not high concentrations of proline and trehalose (Walters et al. Reference Walters, Sformo, Barnes and Duman2009). In general, our cryoprotectant concentrations were probably too low to have considerable effects on supercooling point depression via colligative means. Other polyols – such as threitol, sorbitol, and ribitol – also serve a cryoprotective role in cold-tolerant insects (e.g., Miller and Smith Reference Miller and Smith1975; Hamilton et al. Reference Hamilton, Mullins and Orcutt1985), and it would be worth investigating additional cryoprotectants via metabolomics in future analyses of stoneflies. Cryoprotectant abundance also often declines in spring (e.g., Vesala et al. Reference Vesala, Salminen, Koštál, Zahradníčková and Hoikkala2012; Feng et al. Reference Feng, Xu, Li, Xu, Cao and Wang2016), and measurements of cryoprotectants in A. pygmaea collected earlier in the year than in the present study could show different trends.

Figure 2. Concentrations (µmol/g wet mass) of putative cryoprotectants in whole-body homogenates of Allocapnia pygmaea collected in Antigonish, Nova Scotia, Canada, in March 2024. For each interquartile range, the middle line indicates the median, the top represents the first quartile, and the bottom represents the third quartile. Outlier points are represented by dots. An asterisk indicates a significant decrease between field-collected and cold-shocked stoneflies, as determined by an analysis of covariance test (Table 2).

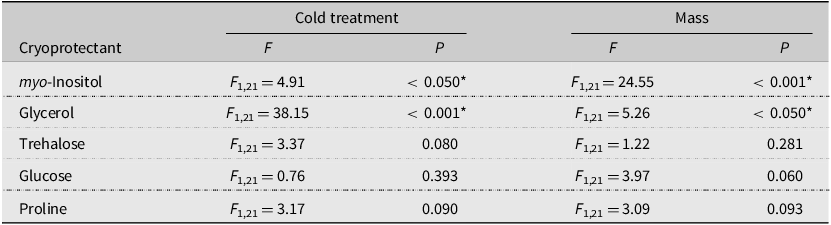

Although short, nonlethal temperature exposures often cause insects to accumulate cryoprotectants as part of a “rapid cold hardening” response, the stoneflies in our study seemed to deplete putative cryoprotectant reserves following a cold shock. When stoneflies were cold-shocked at –4.9 °C and allowed to recover for 24 hours at 4 °C, we observed a trend of decreased concentration for all putative metabolites, which was statistically significant for glycerol and myo-inositol (Table 2; Fig. 2). As a short-lived, nonfeeding adult (Hilsenhoff Reference Hilsenhoff, Thorph and Covich2001), A. pygmaea may adaptively use glycerol as a source of ATP (e.g., via pathways described in Thompson et al. Reference Thompson, Borchardt and Wang2003 and Jørgensen et al. Reference Jørgensen, Hansen, Willot and Overgaard2023) to recover from injury or move towards a warmer microclimate following exposure to subzero temperatures. The exact role of cryoprotectants across A. pygmaea’s life stages is something future studies may tackle, expanding our knowledge on an understudied but bioindicative and climate-sensitive species (Agouridis et al. Reference Agouridis, Wesley, Sanderson and Newton2015).

Table 2. Effect of treatment (field-collected or cold-shocked) on cryoprotectant concentrations in Allocapnia pygmaea collected in Antigonish, Nova Scotia, Canada, in March 2024. Asterisks indicate a significant P-value result from the analysis of covariance test with mass as a covariate

Data availability statement

All data and analysis code used for this study are available at https://github.com/jtoxopeus/stoneflies.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank S.E. Rokosh for assistance with field collections. J.L.P. and L.S.B. were each supported by a Nova Scotia Graduate Scholarship, and the research was supported by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant to J.T.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.