1. Introduction

Glaciers have been retreating and will continue to retreat in high mountain regions worldwide (Rounce and others, Reference Rounce2023; The GlaMBIE Team, 2025). This has created an unexpected boon for archaeology in some locations. Well-preserved artefacts made from organic materials are being released as the ice retreats (Andrews and MacKay, Reference Andrews and MacKay2012; Reckin, Reference Reckin2013; Dixon and others, Reference Dixon, Callanan, Hafner and Hare2014). At some sites, the preservation of the ice finds is so exceptional, that the objects appear frozen in time. The artefacts and animal bones emerging from snow and ice are a poignant reminder that glaciers and ice patches were also important to humans and animals in the past.

This paper explores the field of glacial archaeology and the role of climate change in its development. When and where did the first discoveries emerge, and how has the release of archaeological ice finds progressed in relation to ice retreat? How do ice dynamics influence the preservation of artefacts within the ice? And what can these finds reveal about palaeoclimate? Finally, we consider the future of glacial archaeology as glaciers and ice patches experience ice mass loss at an accelerated pace.

2. Historical background

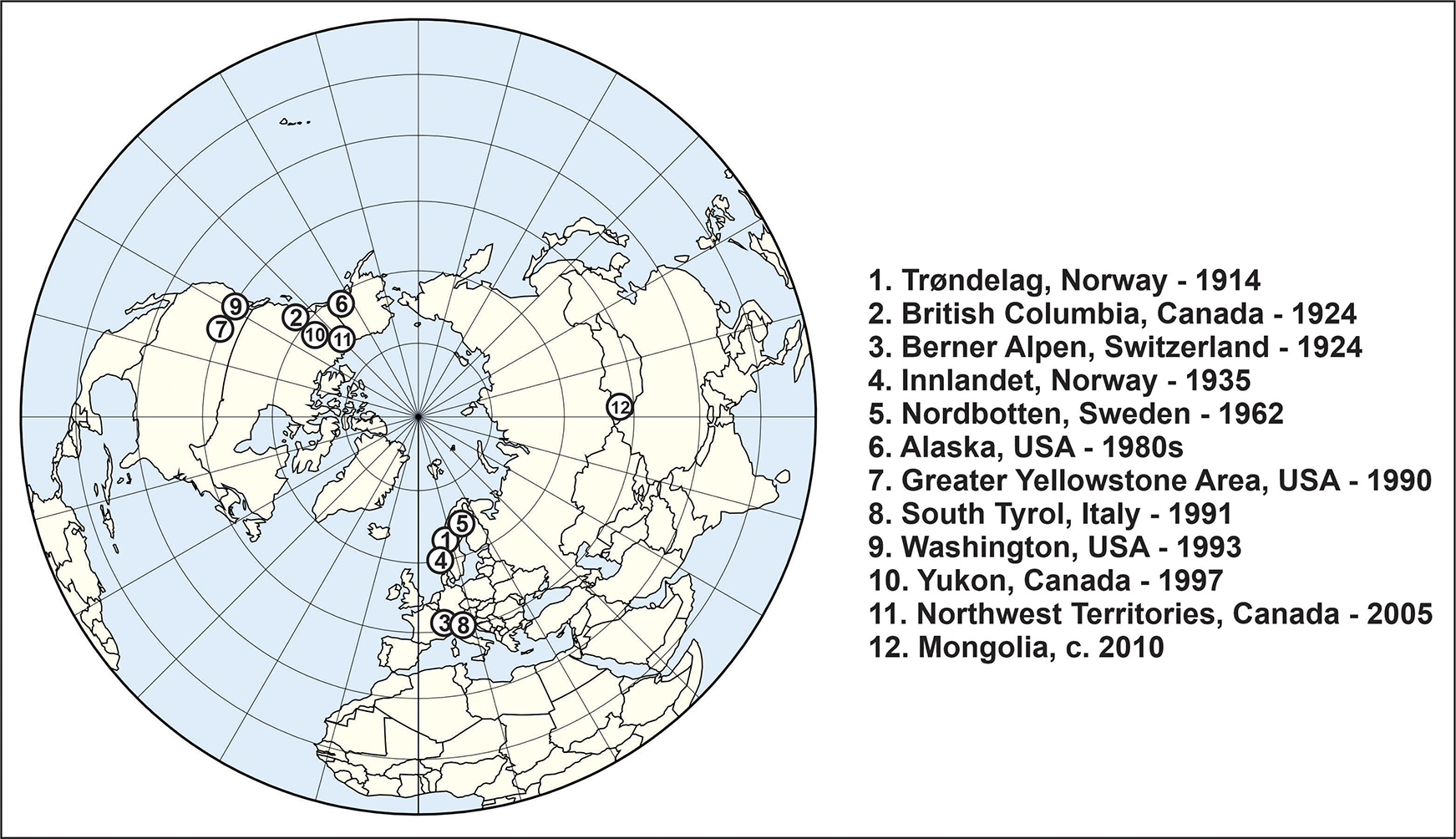

The discovery of Ötzi, the Iceman, as he emerged from the ice in the mountains of South Tyrol in 1991, was the first archaeological find from ice to gain worldwide attention (Spindler, Reference Spindler1993; see Pilø and others, Reference Pilø, Reitmaier, Fischer, Barrett and Nesje2022 for a new understanding of the find). However, he was not the first archaeological discovery from glaciers or ice patches (Fig. 1). The earliest recorded find is an arrow recovered from an ice patch in Oppdal municipality, Trøndelag County, Norway, in 1914 (Callanan, Reference Callanan2012). Another arrow was found on a glacier in British Columbia in 1924 (Keddie and Nelson, Reference Keddie and Nelson2005). That same year, finds also melted out in the Lötschenpass in the Berner Alpen, Switzerland (Hafner, Reference Hafner2015). Further ice finds emerged in Trøndelag and Innlandet Counties, Norway during a period of warmer than average summers in the 1930s (Hougen, Reference Hougen1937; Farbregd, Reference Farbregd1972; Callanan, Reference Callanan2012). Finds were still occasionally reported in subsequent decades, including two arrows found in the Torneträsk Mountains, Sweden, in 1962 (Lundholm, Reference Lundholm1976) and a Viking spear found at the Lendbreen ice patch, Innlandet County, in 1974 (Pilø, Reference Pilø2017). An antler projectile point from melting ice was identified in Alaska, USA, in the 1980s (Dixon, Manley and Lee Reference Dixon, Manley and Lee2005). A leather artefact was recovered from the ice in the Greater Yellowstone Area, USA in 1990 (Lee, Reference Lee2012).

Figure 1. Timeline of the first glacial archaeological finds and location of the regions with finds. Map of the Northern Hemisphere. Map based on a public domain image by BMacZero (CC0 1.0), via Wikimedia Commons.

The discovery of Ötzi in 1991 marked the beginning of a new phase of glacial archaeology, with a sharp increase in the number of ice finds. In 1993, a pack basket melted out of the ice in Olympic National Park, Washington, USA (NPS, 1999). In 1997, artefacts and biological material were recovered from ice patches in Yukon, Canada (Farnell and others, Reference Farnell2004). Soon afterwards, archaeological discoveries from ice were made elsewhere in western Canada (Andrews and others, Reference Andrews, MacKay and Andrew2012; Hebda and others, Reference Hebda, Greer and Mackie2017), as well as Alaska (Dixon and others, Reference Dixon, Manley and Lee2005; VanderHoek and others, Reference VanderHoek, Dixon, Jarman and Tedor2012) and the greater Yellowstone area (Lee, Reference Lee2012). Finds were also reported from the Alps, especially from the Schnidejoch site in Switzerland (Hafner, Reference Hafner2015). Finds have also been recovered from the mountain ice in Mongolia (Taylor and others, Reference Taylor2021).

A few ice finds were reported from Innlandet County, Norway, from 2002 onwards. In 2006, a high-melt episode affected the glaciers and ice patches in southern Norway, leading to the emergence of hundreds of artefacts. Among them was a rawhide shoe from the Langfonne ice patch in Innlandet, radiocarbon-dated to ∼1300 cal BCE (Before Common Era), corresponding to the Early Bronze Age (Finstad and Vedeler, Reference Finstad and Vedeler2008). Since then, a long-term Glacier Archaeology Program to locate and recover ice finds has increased the Innlandet total to 4500 artefacts from 70 sites.

Other parts of the world have also seen increases in the number of ice finds and sites, though not as markedly as in Innlandet County.

The exposure of archaeological finds due to ice mass loss is part of a broader threat to frozen cultural heritage generally, caused by rising temperatures (Hollesen and others, Reference Hollesen2018; Clark and others, Reference Clark2021; Reitmaier, Reference Reitmaier2021).

3. How glaciers and ice patches preserve cultural heritage

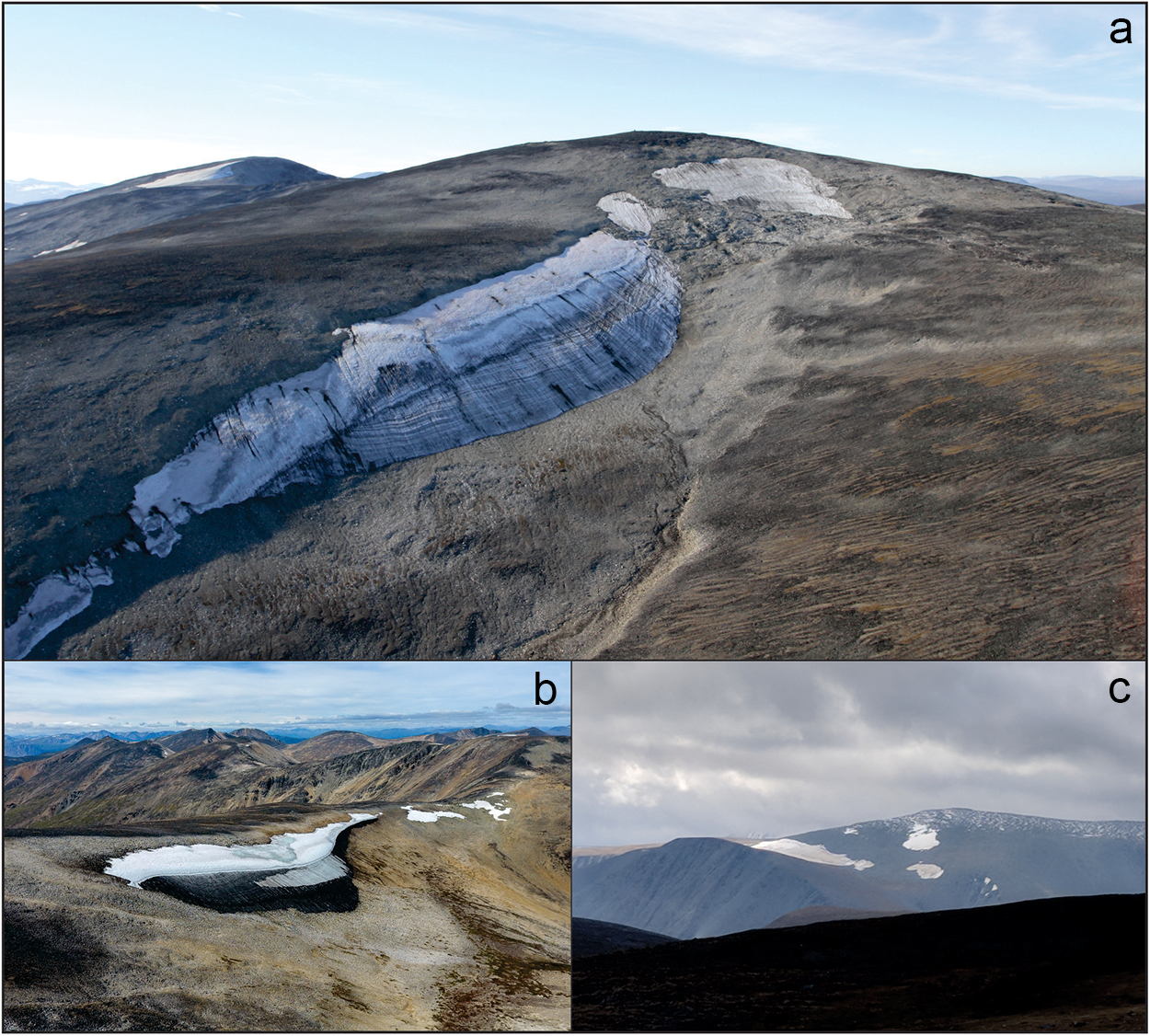

When glacial archaeology emerged as a distinct discipline, the preservation of artefacts was often explained in simple terms: stationary ice patches preserved material (Fig. 2), while moving glaciers destroyed it. Fieldwork has since shown that this view is too narrow. A more useful way of thinking is as a ladder of snow and ice forms, where each step has different implications for preservation (Pilø and others, Reference Pilø2021a).

Figure 2. Examples of ice patches with archaeological finds. (a) Langfonne, Innlandet County, Norway. The reindeer hunting site has yielded 68 arrows, dating back to 4100 BCE. Photo: Lars Pilø, Innlandet County Council. (b) Ice Patch JcUu-1 in the overlapping traditional territories of the Carcross/Tagish First Nation and the Kwanlin Dün First Nation near Alligator Lake, Yukon. This ice patch has yielded 80 hunting weapons, 450 palaeontological collections spanning 6400 years before present, and is surrounded by a complex of 72 stone hunting lookouts (Christian Thomas, pers. comm., May 7, 2025). Photo: Yukon Government. (c) Khultsuut Ice Patch 3 at Tsengel Khairkhan in western Mongolia. The earliest find at this ice patch dates to ∼1600 BCE (Taylor and others, Reference Taylor2021). Photo: William Taylor, University of Colorado—Boulder.

At the lowest step are intermittent snow patches that lack a permanent ice core. They sometimes preserve organic material, though usually in poor condition (VanderHoek and others, Reference VanderHoek, Wygal, Tedor and Holmes2007, Reference VanderHoek, Dixon, Jarman and Tedor2012). When such snow patches persist and accumulate mass, they develop into bed-frozen ice patches with a permanent ice core. Such ice patches can provide excellent preservation conditions, and finds can survive for millennia in excellent condition.

Larger ice patches represent the next step. Still frozen to the ground, they may begin to deform internally. Preservation is then more variable, depending on how much the artefacts have been affected by the slow ice movement (Pilø and others, Reference Pilø2021a).

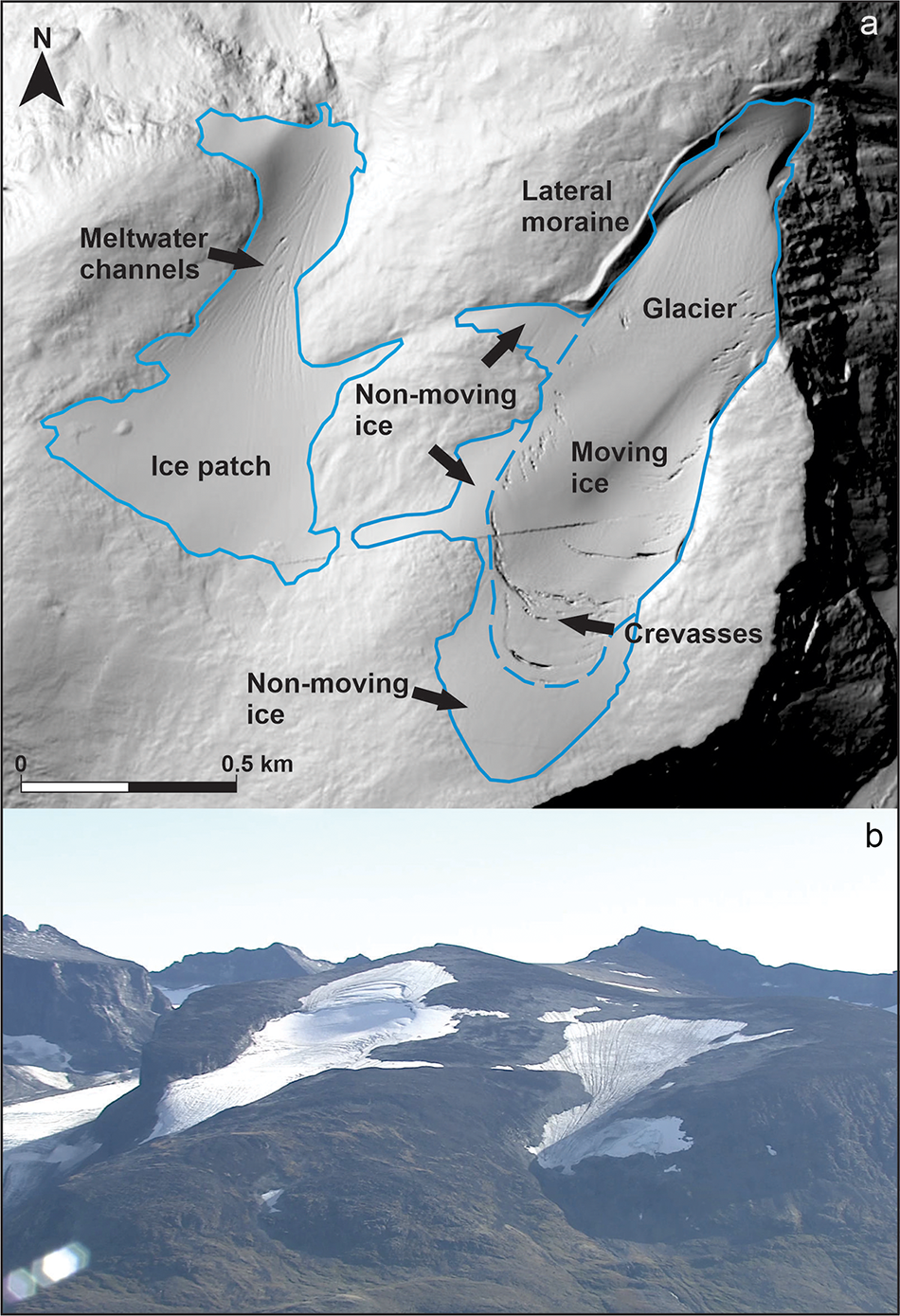

At the top of the ladder are dynamic glaciers. Constant ice renewal and deformation usually prevent survival of ice finds older than about 500 years, though crevasses enhance the possibility of trapping bodies of humans and animals (Alterauge and others, Reference Alterauge, Providoli, Moghaddam and Lösch2015; Providoli and others, Reference Providoli, Curdy and Elsig2016). However, such glaciers may be bordered by stationary ice fields at their tops or margins, which can preserve artefacts of much greater antiquity (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Storgrovbrean—a large double ice mass in Lom municipality, Innlandet County, Norway. a) Digital terrain model showing a warm-based, temperate glacier to the east with crevasses and a lateral moraine in the lower part showing the moving ice, but with nonmoving ice at the top and along the upper western edge. Cold-based ice patch to the west with meltwater channels and no crevasses. b) Photo of Storgrovbrean, taken from the north. Glacier to the left, ice patch to the right. Map: Lars Pilø, background map from https://hoydedata.no/LaserInnsyn/.

Because the nature of the ice changes over time, an ice patch today may once have been a glacier, or an ice patch may melt away and be substituted by an intermittent snow patch. Only detailed studies of the ice, its surrounding periglacial environment and the preservation state of the artefacts can reveal past ice dynamics and their implications for cultural heritage.

The age of the ice determines the maximum age of any organic material contained within it. In mainland Norway (excluding Svalbard), the earliest radiocarbon-date of the ice is found at the bottom of the Juvfonne ice patch, dating to ∼5600 BCE (Ødegård and others, Reference Ødegård2017). In North America, even older ice has been dated (Farnell and others, Reference Farnell2004; Chellman and others, Reference Chellman2021), with corresponding early archaeological finds up to 10 000 years old (Hare and others, Reference Hare, Thomas, Topper and Gotthardt2012; Lee, Reference Lee2012).

To date, no ice patches have yielded radiocarbon dates from the Pleistocene, likely due to the early- and mid-Holocene warming (Marcott and others, Reference Marcott, Shakun, Clark and Mix2013) that caused extensive ice loss in Norway and elsewhere (for Norway: Nesje and others, Reference Nesje, Bakke, Dahl, Lie and Matthews2008). However, it is possible that such ice patches dating back to the Pleistocene exist, most likely in the high Arctic or Antarctica.

4. Methodological challenges

Glaciers and ice patches can preserve artefacts in a pristine condition, effectively freezing them in time. However, once they melt out and are exposed to the elements, natural taphonomic processes resume, leading to a loss of valuable information. It is therefore crucial to recover these artefacts as soon as possible.

In large mountainous regions with numerous ice patches and glaciers, and limited funding for fieldwork, a strategic approach is necessary to identify and prioritize the most promising sites. It is thus important to think of a multi-disciplinary approach, with collaboration of scientists from various fields to aim for productive research projects. Below, I outline the methodological framework applied in Innlandet County, Norway, as described in more detail in Pilø and others (Reference Pilø2021a).

Survey preparations begin with the analysis of aerial photos and digital terrain models to identify ice masses with minimal or no movement. These stable ice masses are then targeted by exploratory surveys under optimal conditions (in average to high melt years), typically during the period mid-August to mid-September, when seasonal snow cover is at its lowest.

If a site yields a significant number of ice finds, it subsequently becomes the object of a large systematic survey. The vegetation-free areas surrounding the ice, known as the lichen-free zone (LFZ) will be combed over by a survey team, and all archaeological and biological finds are recorded and collected. During periods of intense melting, artefacts may also emerge on the ice surface. In such cases, survey effort extends onto the ice, requiring the use of crampons and ropes for safety. Objects do not stay for long on the surface of ice patches, as meltwater quickly flushes them downslope to the ground in front of the ice.

Once the LFZ has been thoroughly surveyed, the site is added to a monitoring list and is visited only when further ice retreat occurs.

To optimize field efforts, summer melt patterns are monitored using satellite imagery, supplemented by local ground observations. This helps prioritize resources effectively. Given that snowfall during the field season is not uncommon, field operations must remain flexible, with the ability to adapt, postpone or shift focus to alternative sites on short notice.

So far, the primary focus has been on finding and recovering the artefacts and biological materials from the ice before they are lost to decay. However, dating the ice and recovering ice cores should also be an integral part of glacial archaeological fieldwork. These data provide critical insights into ice dynamics and site formation processes, as well as the broader archaeological and environmental record (Pilø, Reference Pilø2025).

More generally, the archaeology of glaciers and ice patches is best approached as a multidisciplinary field. Archaeologists document and recover artefacts, while glaciologists contribute knowledge of ice formation, ice motion, internal structure and melt dynamics through methods such as coring and ground-penetrating radar. Palaeobiologists and environmental scientists add insights from pollen, animal bones and dung, ancient DNA, and isotopes preserved in the ice, which provide records of past environments and climates. By combining these perspectives, researchers can link human activity with environmental change, better understand site formation processes and preserve both artefacts and fragile palaeo-environmental archives before they are lost to decay after the ice has melted away (Pilø, Reference Pilø2025).

5. Glacial archaeology and palaeoclimate

The artefacts and biological materials emerging from glaciers and ice patches provide tangible visual evidence of ongoing global warming and ice retreat. But can these ice finds also serve as palaeoclimatic indicators?

Early studies suggested that radiocarbon-dated artefacts indicated a link between the presence of glacial archaeological finds and periods of extensive glaciation (Nesje and others, Reference Nesje2012). The hypothesis was that artefacts lost during glacier advance were more likely to be preserved than those deposited during periods of glacier retreat. However, more recent studies from Innlandet, from a single site with numerous ice finds representing a long chronological sequence and from the county’s ice finds as a whole, suggest there is little evidence of a causal relationship between the number of preserved finds and past fluctuations in glacier extent (Pilø and others, Reference Pilø2018; Pilø and others, Reference Pilø2021b).

This pattern likely reflects the physical dynamics of the ice in which such finds are preserved. Small ice patches respond rapidly to changes in weather and climate, expanding and contracting faster than large glaciers. As a result, most artefacts lost on ice patches have melted out on one or more occasions in the past. New research also shows that artefacts outside an ice patch do not deteriorate as quickly as previously assumed. At Langfonne, for instance, a ∼1500-year-old Iron Age arrow was found at a distance of 100 m from the present ice edge, indicating that it had been exposed for a considerable period (Pilø and others, Reference Pilø2021b). Only the wooden shaft remained, but it was sufficient for a radiocarbon dating.

A notable exception is the glaciated mountain pass site of Lenk, Schnidejoch, in the Swiss Alps, where a large number of ice finds provide direct evidence of past ice extent. The pass was difficult to access during periods of extensive glaciation, which is reflected in the age of the recovered artefacts, as finds are more numerous during periods when the ice was comparatively small (Hafner, Reference Hafner2015).

The preservation of Ötzi, the ice mummy, and his associated artefacts was believed to be caused by the immediate and permanent burial in ice, as his death was supposed to have occurred at the sudden onset of a cold climatic period (Baroni and Orombelli, Reference Baroni and Orombelli1996). However, this interpretation arose from a lack of comparative evidence when the find was made in 1991 and does not align with current understanding of glacial archaeological site formation (Pilø and others, Reference Pilø, Reitmaier, Fischer, Barrett and Nesje2022).

6. Important archaeological finds from glaciers and ice patches

Archaeological finds primarily end up in glaciers and ice patches because of hunting on the ice or transport routes crossing the ice. Hunting sites are common in North America, Norway and Sweden, while transport sites are more frequent in the Alps, with a few examples also known from Innlandet, Norway (e.g. Hare and others, Reference Hare, Thomas, Topper and Gotthardt2012; Hafner, Reference Hafner2015; Pilø and others, Reference Pilø2018; Pilø and others, Reference Pilø, Finstad and Barrett2020).

Reindeer/caribou go on to ice patches on hot days in the summer to avoid pestering insects. Reindeer hunting on ice patches was widespread in Yukon and Scandinavia, and hunting tools were lost or discarded during such activities. Atlatl darts (found only in North America) and arrows are among the most common finds recovered from the ice patches. These are particularly significant, as such objects are rarely preserved elsewhere, except for the nonorganic projectile points. When minimal ice movement is present, arrows can be preserved with all their components intact: arrowhead, sinew lashings, pitch, wooden shaft and fletching, offering unique insights into prehistoric technology (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Examples of glacial archaeological finds. (a) A 1500-year-old arrow with preserved fletching, with the front end still inside the ice. Trollsteinhøe, Innlandet, Norway. Photo: Andreas Nilsson, Innlandet County Council. (b) A copper tipped arrowhead recovered from the traditional territories of the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations, Yukon, Canada. This piece was likely lost during a caribou hunt 5 or 6 hundred years ago. The copper blade was considered a sign of wealth in pre-colonial times. This arrowhead was recovered from a now extinct ice patch near Gladstone Lakes, an area that has produced artefacts relating to 9300 years of continuous indigenous hunting (information from Christian Thomas, pers. comm., May 7, 2025). Photo: Yukon Government. (c) Horse mandible, found at Munkhkhairkhan in Khovd, western Mongolia. Photo: William Taylor, University of Colorado—Boulder.

Transport sites provide a wider insight into material culture. These sites are often glacierized mountain passes. A key example is the Lendbreen ice patch in Innlandet, Norway. Historical sources do not mention that Lendbreen had served as a mountain pass, but in 2011, a pass area melted out at the summit of the ice patch. Since then, more than a thousand finds have been recovered, including clothing, household items, remains of sleds, packhorse bones, horseshoes and horse dung. Radiocarbon dates of the finds indicate that the pass was in use from ∼200 CE to 1500 CE (Pilø and others, Reference Pilø, Finstad and Barrett2020).

In addition to artefacts, glaciers and ice patches also preserve zoological materials such as bones and antlers, which can be used for ancient DNA studies. Most of this material is naturally deposited and provides an important reference for understanding when the ice has preserved natural materials, as opposed to the cultural materials left by humans. Langfonne ice patch in Innlandet, Norway, provides an example of this. During the 8th century CE reindeer bones nearly disappear from the site, while the number of arrows peaks at the same time, suggesting an intense but ultimately unsustainable phase of hunting (Pilø and others, Reference Pilø2021b).

The large number of archaeological finds from glaciers and ice patches demonstrate that human activity in the high mountains was far more extensive than previously thought, even during winter, as evidenced by finds of skis and sleds. Innlandet County, Norway, has an exceptional high number of ice finds and sites, likely due to the short distance between the valley farmsteads and the glaciers and ice patches in the surrounding mountains, in combination with social and historical factors, such as the development of a market for reindeer products outside the region during the Late Iron Age. The long-term efforts of the Glacier Archaeology Program to locate and recover these finds have also played a role in producing the high number of finds.

7. The future of the archaeology of glaciers and ice patches

The archaeology of glaciers and ice patches is now in an intensive field phase, with a strong focus on recovering artefacts and biological materials emerging from the retreating ice. This phase will continue as long as remains of glaciers and ice patches exist. The archaeological finds are getting steadily older as the mountain ice retreats.

At present, only Yukon and Innlandet have permanently funded programs dedicated to recovering finds and documenting the archaeology of glaciers and ice patches. These regions also contain the highest concentrations of finds and sites on their respective continents, demonstrating that sustained, systematic efforts are essential for significant discoveries. In other regions, short-term, targeted efforts have produced ice finds as well, such as recent work in Mongolia (Taylor and others, Reference Taylor2021). However, additional dedicated programs are needed, particularly in areas that have seen little or no glacial archaeological fieldwork so far, with the Himalayas and the Andes being obvious examples.

In the future, there is hope that glacial archaeology will become more closely integrated with palaeoclimate research, with closer collaboration during field investigations.

8. Conclusion

The archaeology of glaciers and ice patches has emerged as a distinct field, in response to the melt-out of artefacts from retreating ice, driven by anthropogenic climate change. Ice finds have been recorded in North America, the Alps, Scandinavia, and more recently, Mongolia. The artefacts date back up to 10 000 years.

The preservation of these artefacts can be exceptional, especially in ice patches. The ice finds offer unique insights into technology, subsistence strategies and mobility, often not available from traditional lowland archaeological contexts.

This unprecedented wave of discoveries presents an unexpected possibility for archaeology, but also a crisis. The exposed artefacts deteriorate rapidly once out of the ice. Without targeted recovery efforts, both the archaeological finds and the historical information they hold will be lost.

Further integration of glacial archaeology with palaeoclimate research, particularly through the study of the ice at ice patches with archaeological finds, could deepen our understanding of past climate fluctuations and human responses to environmental change.

At the same time, the visibility of these discoveries offers an additional dimension: objects preserved in glaciers and ice patches can illustrate the consequences of anthropogenic climate change in ways that resonate beyond the academic community, thereby enhancing the societal relevance of glacial archaeology.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Liss M. Andreassen and Espen Finstad for valuable comments to a previous version of the paper. Thanks to Christian Thomas and William Taylor for graciously providing photos and information from Yukon and Mongolia. The Glacier Archaeology Program in Innlandet, Norway is a cooperation between Innlandet County Council and the Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo. The glacial archaeological work in Innlandet can be followed at https://secretsoftheice.com/.