Introduction

Wielkopolska was the ideological and political centre of the Piast dynasty dominion, emerging in the second half of the tenth century AD). The dynasty probably originated from, or had close ties with, the stronghold at Giecz, established as early as the 860s. In addition to Grzybowo, Poznań, Gniezno and Ostrów Lednicki are considered exceptional or ‘central’ strongholds of Wielkopolska (Figure 1). The distinction of Giecz, Poznań, Gniezno and Ostrów Lednicki from other sites of this type in Wielkopolska, and the Piast dominion in general, is determined from written sources, the remains of sacral and residential stone architecture discovered in these locations and the size and form of the strongholds, as well as numerous traces of elite culture (Kurnatowska Reference Kurnatowska2002: 191–202; Kurnatowska & Kara Reference Kurnatowska and Kara2010: 41–45). New research, launched in 2018 as part of project “The stronghold in Grzybowo and its supply base in the context of in-depth interdisciplinary research”, now allows us to include Grzybowo in this group of central strongholds.

Figure 1. Map showing the location of Grzybowo and the other central strongholds mentioned in the text (figure by M. Bucka, M. Danielewski, A. Głód & M. Stelmasiak-Majorek).

The spatial and functional layout of the stronghold

Currently, the Grzybowo hillfort (site 1) covers 4.4ha, although originally there were two strongholds operating as a single settlement complex, and the contours of the ramparts indicate a perimeter of up to 680m (Figure 2). Grzybowo was therefore second only to Poznań in size in the mid- to late tenth century, and later to Gniezno, which occupied an area of around 4.6ha in the early eleventh century (Danielewski Reference Danielewski2021: 52). At an early stage, Grzybowo was distinguished as a bipartite establishment; testifying to the site’s elite intent. First, a smaller stronghold was built, probably an elite structure with ramparts reaching a width of about 25m and an oval-shaped main square enclosing an area between 52.6m and 41m. The two-part site also enjoyed a good location on the east bank of the Struga, a river with several beds forming seasonal floodplains to the west. The watercourse was probably important for defending the outer settlement (site 6) and meant that the most convenient approach to the stronghold was from the east, where a dry moat about 13–14m wide (and occasionally wider) was constructed 60–120m beyond the ramparts. There may have been a second ditch at a distance of about 40–45m from the eastern base of the ramparts, but this has not yet been verified by excavations. The entire complex was complemented by an outer settlement located to the south and south-east of the stronghold (Figure 3), occupying approximately 6.4ha.

Figure 2. Contour plan with archaeological excavations of the small and large Grzybowo strongholds and the outer settlement (figure by A. Głód, W. Małkowski & M. Stelmasiak-Majorek).

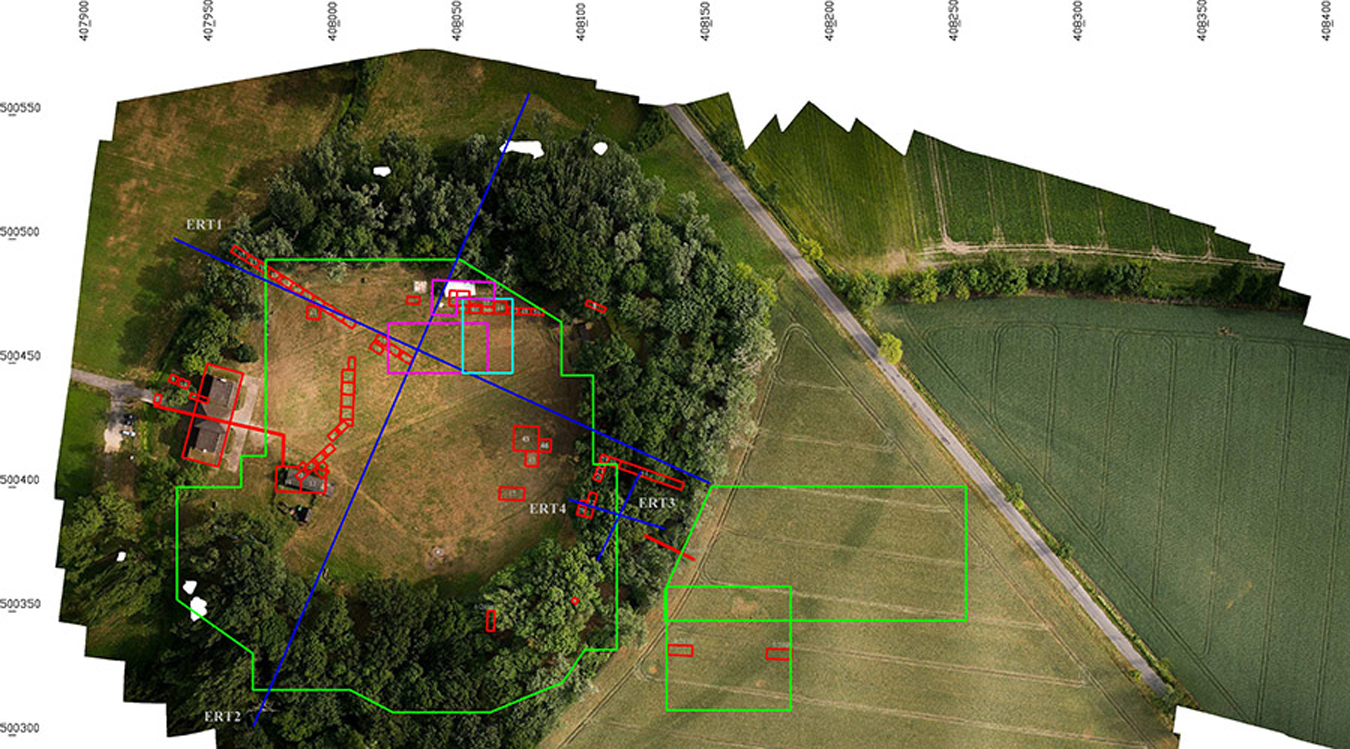

Figure 3. Orthophoto of the hillfort and outer settlement with marked archaeological trenches and non-invasive surveys (figure by A. Głód, W. Małkowski & M. Stelmasiak-Majorek).

The chronology

Dendrochronology of the wooden stronghold structures proved crucial in determining a time frame for the construction and use of the Grzybowo stronghold. According to tree-ring dating, the first phase of the structure (i.e. the small stronghold) dates back to AD 919–923. These fortifications were made of oak wood, including oak trees that were more than 400 years old. Investment in the site continued between 929 and 935, and into the early 940s, when the large stronghold was erected. Therefore, this was an almost contemporaneous investment, while both establishments operated simultaneously (Figure 2). During studies carried out at site 1, more than 280 samples were collected from decommissioned elements of wooden structures for dendrochronological analyses. Of these, 246 were suitable for dendrochronology, permitting the dating of structures with a high degree of accuracy (Figures 2 & 4). These abundant data on the chronology of the site are supplemented by analysis of the ceramic material, which indicates intensive use of the Grzybowo settlement by the mid-eleventh century (Danielewski Reference Danielewski2021: 12). Establishment of this chronology makes the Grzybowo stronghold one of the best dendrochronologically dated medieval stronghold remains from Central Europe.

Figure 4. Dendrochronologically dated annual increments of oak wood samples recorded during excavations at Grzybowo. The sapwood is marked in orange, the heartwood zone in green (figure by M. Krąpiec).

The political, military and economic context

It remains crucial to determine the political and military role of the Grzybowo stronghold. This task is difficult as the site operated for only a short time: until the mid-eleventh century. Yet, the area covered, the length of the ramparts, the complex settlement structure (Figure 5) and the depth of cultural stratification in the areas around the ramparts of the small stronghold (up to several metres) signal the site’s importance. Various hypotheses have been proposed for the operations of such a large structure. Assumptions that it was built to prepare for the occupation of Gniezno, the later seat of the archbishopric (since 1000) and the place where the first rulers of the Piast dynasty were crowned (since 1025), have proved unfounded. Similarly, the view that the foundation was built as a place of temporary detention for captives resettled from conquered territories before they were sold into slavery does not fit with the results of new research and the artefacts excavated from the site (for criticism of the slave trade, see Danielewski 2023: 373–77). The elite nature of the (bipartite) site and some of the portable artefacts contradict this latter hypothesis, as do the complex sedimentary layers from the main squares, which have a maximum depth of 2.8m. That Grzybowo was also home to the military elite and members of the princely retinue is evidenced by the presence of horse remains, equestrian equipment (horseshoes, leather strap separators) and rings from chain mail (Figure 6).

Figure 5. A numeric terrain lidar model with the location of archaeological sites along the Struga Valley and the hillfort (figure by A. Głód, W. Małkowski & M. Stelmasiak-Majorek).

Figure 6. Location of selected artefacts discovered at the hillfort, and in the outer settlement (figure by A. Głód, W. Małkowski & M. Stelmasiak-Majorek).

As a large settlement, Grzybowo must have played an important role in the early medieval economic structure of eastern Wielkopolska. Tributes were likely paid to the stronghold, and the discovery of numismatic items, lead weights and the beam from a set of scales in the stronghold and the outer settlement (Figure 6) indicate that the site was a place of thriving trade. Ten archaeological sites have been recorded along the Struga River in the immediate vicinity of the stronghold and its associated settlement. The Grzybowo stronghold was therefore the focal point for this settlement, where population density in the micro-region around Grzybowo was probably very high, ranging from about 22 to even 29 people per square kilometre.

In the historiography of the strongholds of Wielkopolska, the assignment of strongholds to individual members of the ruling family has not been explored. However, strongholds in Eastern and Central Europe, including Ruthenia and Bohemia, were often entrusted to the management, care or possession of particular family members. If, in the 960s and early 970s, the power of the Piasts was based on relatives participating in the governance, and the position of the family was determined by the control of the main Wielkopolska strongholds, the central strongholds should be viewed as the property of respective members of the dynasty. Grzybowo could therefore have been a stronghold of a member of the ruling family, relatives of Mieszko I or his predecessors, who shared power. This seems all the more plausible given the large size of the site, the massive ramparts, the separation of the smaller stronghold (potentially as an elite area), the exceptional nature of some of the finds and the compact outer settlement.

Funding statement

Scientific work sponsored by the Faculty of Archaeology of Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, on the basis of decision DEC-46/WArch/2024.