Introduction

One of the most crucial responsibilities undertaken by pre-hospital care emergency medical services (EMS) personnel actively involved in organizing health care services during disasters is the implementation of triage. Triage or sorting is performed in a dynamic environment involving transport vehicles and definitive treatment sites, where the injured are classified at the scene to maximize life-saving efforts and make the most efficient use of limited resources during mass casualty events.Reference Landis, Benson and Whitley1–Reference Eksi3 The primary goal of triage is to minimize the number of fatalities that may occur in a community due to a disaster.Reference Hasmiller, Staphone, Lancaste and Thomas4 Emergency procedures are key to focusing on this goal.5 The Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment (START) color codes used by the personnel participating in the study, which are accepted in the literature and are among the most frequently used triage methods in disasters, are shown in Table 1.Reference Iserson and Moskop6–9

Table 1. The START triage system’s color-coded category table for prioritizing medical intervention

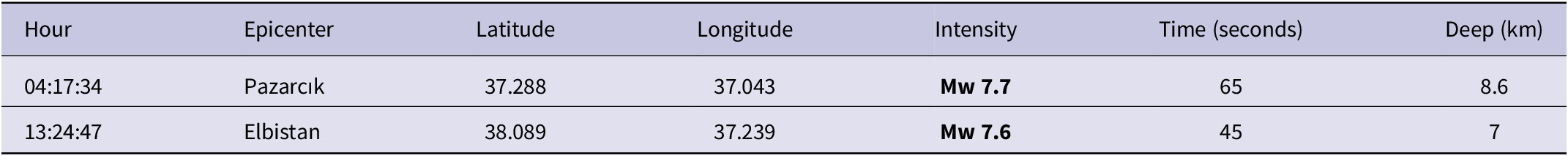

Ethics, as an internal control mechanism that regulates accountability, shapes behaviors by recommending what individuals should or should not do. Internal control, ensured through adherence to ethical principles, becomes particularly crucial in the extraordinary conditions of disasters, where external oversight may be insufficient. However, in some instances, the magnitude of damage caused by disasters and inadequacies in intervention capacity leads to ethical dilemmas in the decisions made by EMS personnel.Reference Eksi, Sen and ve Celikli10 Ethical principles and dilemmas in triage applications have emerged as a frequently discussed topic in the literature in recent years, aiming to enhance the effectiveness of disaster intervention. According to official data, 50,783 people lost their lives and 107,204 were injured in the Türkiye Kahramanmaraş Earthquake, which occurred on February 6, 2023, and consisted of 2 devastating earthquakes. Detailed data are included in Table 2.11

Table 2. Official data table for the February 6, 2023 Türkiye/Kahramanmaraş earthquakes

The purpose of this study is to elucidate the ethical dilemmas faced by EMS personnel during disaster triage, explicitly focusing on the Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes, and to document their experiences. The experiences derived from the Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes, which have taken a unique place in the world’s disaster history due to their formation and the extent of damage they caused, may provide opportunities for improving intervention organizations for future disasters by elucidating their occurrence and the magnitude of damage.

Methods

Research Design

In this study, a phenomenological design was utilized within the scope of qualitative research. Qualitative research aims to understand the meaning of events, situations, and experiences, comprehend the process in which events and actions occur, and identify unexpected events and effects. Phenomenological research is an exemplary science that focuses on lived experiences. Examples are a methodologically important part of phenomenological research. Researchers identify the aspects of events that serve as examples.Reference Van Manen12 This study has 2 main research questions:

-

• What ethical dilemmas did EMS personnel experience when conducting disaster triage during the first 72 hours of the Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes?

-

• What factors contribute to the occurrence of ethical dilemmas experienced by EMS personnel in disaster triage?

Semi-structured interviews, which included more detailed questions, were conducted to address these research questions.

Participants

A purposive sampling method, utilizing a snowball sampling technique, was employed as the sampling strategy. This method was used to select individuals who could provide the most valuable information, thereby gaining a deep understanding of the topic.Reference Van Manen12, Reference Merriam and Tisdell13

The study included volunteer paramedics and EMS personnel from ambulance teams assigned to the earthquake zone, who participated in emergency medical services during the first 72 hours of the 2023 Kahramanmaraş earthquake. These personnel performed triage in the area and were members of a professional association.

Personnel arriving at the scene after 72 hours, those who performed second transport, personnel returning to the disaster area before the interview, and non-volunteer personnel were excluded from the study.

The official task order document was visually confirmed during the interviews. As shown in Table 3, to ensure confidentiality, the participants’ names were not disclosed but were represented by numbers. The participants consisted of 19 Paramedics and 10 emergency medical technicians (EMTs).

Table 3. Descriptive characteristics of the participants

Data Collection

Data were collected between April 15, 2023 and August 15, 2023, through semi-structured interviews in the participants’ native language (Turkish). To assess the functionality and applicability of the semi-structured interview form used in the study for EMS personnel, preliminary interviews were conducted with paramedics who had previously performed triage in disaster areas. The research interviews were conducted with the interview questions reorganized based on the results of the preliminary interviews. The responses provided by participants in the initial study group were not included in the research. In-depth interviews were conducted by recording audio via online applications and reminding participants of the data recorded during previous contacts. Each interview was transcribed within 24 hours and read back to the participant using the same online applications, and their approval was obtained. Interviews continued until data saturation was reached, meaning that no new insights or information emerged from additional interviews.Reference Saunders, Sim and Kingstone14

Data Analysis

In this study, the transcribed interviews were imported into the MAXQDA program and analyzed using content analysis by a paramedic who had actively participated in the Kahramanmaraş Earthquake, an academic who had actively participated in the Emergency Management System, and a professor of disaster medicine. In content analysis, frequently repeated statements, facts, or events in the data set are coded.Reference Krippendorff15, Reference Mayring16 The coding technique used in this study is “coding within a general framework.”Reference Forman and Damschroder17 Significant words and phrases were marked in each participant’s response, and ethical and triage filtering was performed. The process involved moving from codes to categories, and then from categories to themes, to complete the analysis.

The process for ensuring reliability and accurate analysis of the data proceeded as follows:

-

• Reading the transcripts of the interviews

-

• Noting the opinions of the interviewees regarding ethical dilemmas in disaster triage

-

• Theme formation: systematically organizing recurring ideas with text excerpts

-

• Reviewing the themes: checking whether the themes are meaningful and relevant to the research

-

• Identifying and naming the themes: summarizing the narrative with clear definitions

-

• Analyzing the themes using the descriptive analysis method and generating the reportReference Eysenbach and Köhler18–Reference Denzin and Lincoln20

After examining the codes, the researchers reached a consensus and identified 3 main themes, 8 categories, and 19 codes.

Reliability

In qualitative research, credibility, accuracy, consistency of results, and competence of the research are critical factors for ensuring validity and reliability. Researchers can employ various methods such as long-term engagement, expert review, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and triangulation to ensure validity and reliability in qualitative research.Reference Creswell21, Reference Good22 In this study, inclusion criteria and limitations were specified, task forms were examined and verified, and expert opinions and long-term interaction techniques were employed to ensure validity and reliability.

Ethical Considerations

The study has been approved by the Ege University Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Committee and is registered under number 23-5T/13, dated May 11, 2023. Participants in the study have completed informed consent forms and provided verbal consent.

Results

Three main themes were identified in the examination of the ethical dilemmas experienced by EMS employees who performed triage in the February 6 Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes, as shown in Table 4. These themes are disaster management organization, environmental factors, and individual factors.

Table 4. According to the program analysis of the study conducted in MAXQDA; Themes, categories, codes, and word cloud

Disaster Management Organization

According to the responses provided, it has been determined that EMS workers experienced ethical dilemmas primarily due to coordination deficiencies, authority confusion, and communication issues within the disaster management organization during disaster triage. Some of the experiences and opinions expressed by the participants are as follows:

“Those assigned a black code had to be transferred to hospital emergency departments because there was no space to transport them” (P1).

“We were uncertain about which injured person to transport with the limited medical supplies we had” (P17).

Environmental Factors

According to the responses provided, environmental factors are another reason why EMS employees experience ethical dilemmas, and weather conditions, security concerns, and transportation problems are identified as effective factors. Some of the experiences and opinions expressed by the participants are as follows:

“While we were carrying a seriously injured patient with a code red, our path was blocked and we had to perform resuscitation on a dead patient with a code black” (P14).

“Due to the chaos at the scene, we were forced to enter debris that lacked structural security. There may have been instances where I under- or over-triaged” (P27).

Individual Factors

According to the responses provided, another factor contributing to EMS employees’ experience of ethical dilemmas is individual factors. Among individual factors, issues related to education/experience and sensitivity have been identified as the most influential factors. Some of the experiences and opinions expressed by the participants are as follows:

“I received adequate training in disaster triage. However, there were times when I felt very morally uneasy” (P19).

“It was cold, and I had difficulty distinguishing between code black and red because the children had hypothermia. I couldn’t give them a code black, even if they were dead. I thought of my own children” (P29).

“The damage my city suffered and not being able to hear from most of my family affected me. I do not think I was able to fulfil my duties properly” (P17).

Limitations

This study may have some potential limitations. Volunteers who entered the area unverified within the first 72 hours, those who could not present their assignment documents, personnel who did not perform triage, and those who refused to participate emotionally due to their recollection of the event created constraints in our sampling method. The small sample size is a significant limitation of this study. This situation may have led to an exaggeration of the effect. Future research should confirm these findings through larger-scale studies.

Despite these limitations, this study has demonstrated that EMS workers struggle with effective triage in pediatric cases, and those who continue to work despite being victims themselves face increased ethical dilemmas.

Discussion

Ethical dilemmas arising from triage practices in disaster relief efforts complicate the effective management of medical resources and can lead to fatal outcomes due to resource insufficiency. Therefore, it is crucial to implement the necessary legal regulations in this area.Reference Ashton23 Despite the frequent occurrence of disasters in Turkey, there are insufficient regulations regarding the application of triage in disasters. Restrictions on critical health interventions, such as resuscitation practices, may become a necessity during disasters.Reference Eksi, Sen and ve Celikli10, Reference Khan24 Defining these restrictions, which are directly related to the right to life, in legislation relieves intervention workers from administrative and legal problems that may arise later and plays a role in reducing ethical dilemmas.Reference Sen25–Reference Lucas da Silva, Kostako and Matsumoto27 In the early days of the disasters, administrative units informed health care workers affected by the disasters through various communication channels that they would be considered to have resigned and dismissed from public service if they did not report for duty.28 This study has shown that the lack of a clear definition of roles and responsibilities in disaster triage and the resulting authority confusion among EMS personnel increase ethical dilemmas.

EMS workers may face dilemmas in making decisions in unsafe incident scenes,Reference Pozner, Zane and Nelson29 and may struggle to make correct decisions that are beneficial to the affected individuals.Reference Klein and Tadi30, Reference Dincer and Kumru31 The extensive geographical coverage of the affected area by the disaster made it challenging to ensure the safety of intervention workers, and numerous incidents of robbery and threats were encountered. In the Kahramanmaraş Earthquake, the inadequacy of rescue and EMS teams, particularly in the early hours of the disaster, created problems with on-scene management organization. Some relatives of victims pressured emergency response teams to prioritize their own loved ones, contrary to triage protocols. All these factors led EMS workers to face a dilemma between ensuring their personal safety and adhering to triage protocols.11, Reference Başaran, Çol and Köse32–Reference Mavroulis, Mavrouli and Vassilakis34 The data from this study are evaluated, and they show that EMS workers experiencing safety issues are partially caught in an ethical dilemma when making intervention decisions.

In disasters affecting children, it is recommended to apply different procedures and protocols during triage compared to those for adults.Reference Limoncu and Atmaca35 Different injury and death causes in children and adolescents highlight the necessity of implementing a triage system specific to children.Reference El Tawil, Bergeron and Khalil36 Lack of familiarity with pediatric physiology and emotional sensitivities leads EMS workers to experience difficulties in classifying children during disaster triage. EMS workers tend to over-triage pediatric patients during disaster triage.Reference Gilchrist and Simpson37 Consistent with the literature, this study identified significant ethical and emotional challenges in pediatric cases. Participants reported being hesitant to issue code blacks and frequently over-triaged in settings with a high number of pediatric cases. These findings underscore the need for child-specific triage training and demonstrate that emotional sensitivity can exacerbate ethical dilemmas in disaster triage.

Several studies have demonstrated the significant impact of education and experience on the success of disaster triage implementation among EMS personnel.Reference Cicero, Whitfill and Overly38, Reference Sevimli, Dursun and Karadas39 The effect of education and experience on successful disaster triage also facilitates intervention workers in making ethical decisions during triage applications.Reference Khan24, Reference Sen25 However, studies and experiences indicate that EMS workers’ education focuses more on theoretical and practical knowledge, with insufficient emphasis on ethical issues, especially in areas such as disaster triage.Reference Cairo, Fisher and Clemency40, Reference Reeves41 The magnitude of the damage caused by the Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes necessitated the involvement of EMS workers who lacked sufficient education and experience in disasters. Participants with prior disaster experience and triage training were found to be more confident in their triage practices. However, this did not eliminate emotional impact. Findings suggest that training and experience support decision-making but only partially alleviate the ethical and psychological burden of disaster triage.

In situations with many casualties, such as Hurricane Katrina, it has been observed that health care workers tend to prioritize helping their own relatives.Reference Pou42 The magnitude of the Kahramanmaraş Earthquake created a significant shortage of health care workers in the first hours of the disaster. In response to this shortage, local officials asked health care workers who were also disaster victims to assist in the response efforts. The affected health care workers encountered frightening scenes and witnessed numerous deaths and serious injuries. This situation exposed health care workers to high levels of stress from the outset, making it difficult for them to perform their duties effectively.Reference Gökçek, Gökçek and Toker43, Reference Aksoy, Gumustakim and Kus44 According to the report of the Turkish Emergency Medicine Specialists, during the early stages of the Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes, doctors serving in emergency departments had difficulty categorizing triage codes, particularly in assigning “black codes.”45 In the study, both disaster victims and EMS personnel who were forced to continue their duties reported experiencing emotional burnout and difficulty maintaining objectivity in triage decisions. These narratives suggest that the overlapping roles of victimhood and professional responsibility can intensify ethical dilemmas.

Conclusion

This study examined the ethical dilemmas faced by EMS workers during disaster triage. Three main themes emerged: “disaster management organization, environmental factors, and individual factors.” These themes were further divided into 8 sub-themes: “lack of coordination, confusion of authority, communication problems, safety, seasonal conditions, transportation, training/experience, and sensitivity.”

In the Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes, insufficient resources for disaster coordination, unclear legal regulations regarding authority and responsibility in disasters, and coordination problems among intervention teams increased ethical dilemmas. Factors such as the fact that some EMS employees were disaster victims themselves, the lack of experience of personnel who had never been involved in disaster response before, and the presence of a large number of child victims affected EMS employees emotionally and led to more ethical dilemmas, particularly in making black code decisions during triage. EMS personnel experienced in disasters demonstrated less emotional impact from this major tragedy, and those who received proper training were more effective at triage.

In preparing for large-scale disaster response, it is essential to enhance the training and experience of EMS personnel. This can be accomplished by organizing training sessions that integrate disaster triage protocols, along with regular drills. Additionally, it is essential to bolster health care workers’ understanding of ethical issues and to develop guidelines with clear, concise definitions to assist in navigating ethical dilemmas in disaster triage, all of which are supported by relevant legal regulations.

Author contribution

KÇ: Conceptualization, data collection, analysis, manuscript drafting.

AE: Study supervision, methodological design, critical revision of the manuscript.

Funding statement

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

None.