Introduction

As most advanced democracies have witnessed significant increases in inequality over the last decades (Atkinson, Reference Atkinson2015; Piketty, Reference Piketty2017), the question of whether and how economic inequality affects trust in democratic institutions has become more salient. And indeed, several scholars have documented a negative relationship between economic inequality and political trust for a wide range of countries (e.g., Anderson & Singer, Reference Anderson and Singer2008; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Chang and Hur2020; Zmerli & Castillo, Reference Zmerli and Castillo2015). If inequality and trust move together (albeit in opposite directions), an overall increase in inequality should entail a decline in trust. Nevertheless, research on inequality's effects on attitudes towards democracy remains inconclusive. Some scholars either see no overall decrease in trust (or closely related concepts like satisfaction with democracy) or find no clear relation with inequality (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Sommet, Na and Spini2022; Magalhães, Reference Magalhães2014; Martini & Quaranta, Reference Martini and Quaranta2020; Norris, Reference Norris and Norris1999; van Beek et al., Reference van Beek, Fuchs, Klingemann and van Beek2019). To help advance the literature and possibly reconcile these contradictory findings, this article provides further empirical evidence and investigates the mechanisms underlying a potential relationship between inequality and citizens’ democratic orientations.

In what follows, our focus will be on political trust, and thus on, in Easton's (Reference Easton1975) famous words, citizens’ ‘reservoir of goodwill’ towards the actors and institutions of democratic governance, and on European democracies. Concerning the study of the political implications of inequality, we aim for a threefold contribution. First, we contribute new empirical estimates for the effect of inequality on political trust. We specifically aim to improve on the existing literature by isolating an over‐time effect of rising inequality on changes in citizens’ trust. Most of the existing literature is based on cross‐sectional designs and has therefore been unable to identify whether (recent) changes in economic inequality are contributing to what has been described as the ‘democratic malaise’ (e.g., Foa et al., Reference Foa, Klassen, Slade, Rand and Collins2020) of declining support for democracy in the Western world. Drawing on time‐series cross‐sectional survey data from the European Social Survey (ESS), we provide firm evidence that changes in inequality are indeed negatively correlated with changes in political trust. Given extensive controls for observables and country‐specific unobservables as afforded within the context of a fixed effects (FE) regression specification and given an extensive set of further robustness checks, our estimates substantiate a causal role of inequality for political trust. Inevitably, however, any such causal claim carries a degree of uncertainty, and we will therefore discuss the relevant methodological issues and limitations of our research throughout the paper.

In addition, we seek to expand on earlier research by testing the full causal chain between inequality and citizens’ trust in democratic institutions when taking external efficacy as an important, but so far also largely overlooked mediator. When reflecting on why inequality (or other aspects of macroeconomic performance) should matter for political trust, the currently dominant theoretical perspective suggests to regard trust in institutions as the consequence of a conscious evaluation process on the citizens’ side. This ‘trust‐as‐evaluation’ approach (see van der Meer, Reference van der Meer and Uslaner2018) sees income inequality as one output of democratic governance, which citizens then evaluate in view of their political preferences, and trust is extended when citizens conclude that the political system is meeting their demands.

Yet we argue that this type of substantive and output‐based evaluation is not necessarily the only mechanism through which inequality may affect citizens’ trust in democratic institutions, but that a second, more process‐based type of evaluation needs to feature more prominently. In making this argument, we build on a tradition in political science which has long argued that inequality in economic resources translates into inequality in political resources and consequently into unequal political representation and responsiveness (Dahl, Reference Dahl1971, Reference Dahl2006; Goodin & Dryzek, Reference Goodin and Dryzek1980; Schattschneider, Reference Schattschneider1960; see also Polacko, Reference Polacko2022). Rising inequality may be presumed to affect how citizens perceive the distribution of political power and how they see their capabilities to influence the political process. With this type of mechanism in operation, inequality would erode political trust by depressing citizens’ evaluations of the fairness of democratic processes but not because of citizens’ concern about inequality as a political problem.

Our study is the first to confirm the existence of this second transmission channel from empirical data. Our analysis shows that rising income inequality depresses citizens’ perceptions of external efficacy and that lower degrees of efficacy are a determinant of lower trust in institutions. Importantly, these findings are not meant to deny the relevance of output‐based performance evaluations. Instead, our results suggest that output‐ and process‐based mechanisms are complementary. We find that efficacy is an important mediator for the relationship between inequality and political trust. However, a direct effect of inequality remains that cannot be explained via efficacy. In addition, and in line with earlier findings (e.g., Anderson & Singer, Reference Anderson and Singer2008), we see that the direct effect of inequality is moderated by respondents’ political ideology, as predicted from the assumption that left‐leaning citizens react more sensitively to economic inequality because it is a politically salient issue for them. However, the same type of ideological moderation is not visible in the efficacy channel, where left‐ and right‐leaning citizens alike show a declining sense of external efficacy when economic inequality is rising, and where similar declines in efficacy perceptions generate similar responses for political trust.

We believe that placing a perspective on citizens’ evaluation of political power and fair democratic processes alongside the standard perspective of output‐based evaluations enriches the argument that democratic stability may be undermined when economic inequality is translated into political inequality. In addition, drawing attention to the largely non‐partisan transmission channel of citizens’ efficacy perceptions may resolve the empirical puzzle of why inequality also depresses political trust among right‐leaning citizens, for whom (rising) inequality would presumably not be an important political problem in the first place.

Before coming back to the implications of our work, in what follows we first provide further theoretical background to our study and then discuss our data, methodology and empirical findings.

Theory and previous research

Economic inequality has risen in many Western democracies over the last decades (see Atkinson, Reference Atkinson2015; Piketty, Reference Piketty2017, and the online Supporting Information for descriptives for the countries in this study). At the same time, observers and political scientists alike are asserting a ‘democratic malaise’ (e.g., Foa et al., Reference Foa, Klassen, Slade, Rand and Collins2020), which is mirrored in gloomy titles such as ‘The People vs. Democracy’ (Mounk, Reference Mounk2018), ‘How Democracies Die’ (Ziblatt & Levitsky, Reference Ziblatt and Levitsky2018) or ‘How Democracy Ends’ (Runciman, Reference Runciman2018). This malaise is seen as consisting of a longstanding decline in citizens’ support for the processes and institutions of democratic governance (Dalton, Reference Dalton1998; Foa et al., Reference Foa, Klassen, Slade, Rand and Collins2020; Hetherington, Reference Hetherington1998) and thus threatening the functioning of democracy itself (Lipset, Reference Lipset1963; Easton, Reference Easton1975). As a central indicator of political support, citizens’ trust in the institutions of representative democracy has repeatedly been shown to be negatively related to inequality (Anderson & Singer, Reference Anderson and Singer2008; Goubin & Hooghe, Reference Goubin and Hooghe2020; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Chang and Hur2020). Studies on satisfaction with democracy and on other related indicators of political support have likewise reported negative associations with income inequality (Andersen, Reference Andersen2012; Christmann, Reference Christmann2018; Donovan & Karp, Reference Donovan and Karp2017; Krieckhaus et al., Reference Krieckhaus, Son, Bellinger and Wells2014; Schäfer, Reference Schäfer, Keil and Gabriel2013). Other scholars remain more sceptical as to whether democratic attitudes may be affected by income inequality in particular, or macroeconomic performance in general (e.g., McAllister, Reference McAllister and Norris1999; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Sommet, Na and Spini2022; see van der Meer, Reference van der Meer and Uslaner2018, for a recent review of the literature)

As pointed out by van der Meer (Reference van der Meer, Zmerli and Van der Meer2017, Reference van der Meer and Uslaner2018), one likely reason for the inconclusive state of evidence is that most studies have been based on cross‐sectional data. This evidently makes drawing inferences about how changes in inequality may lead to changes in trust questionable, not the least because of the problem of omitted variables and unobserved heterogeneity between countries. For example, countries may be more or less equal, but they also may exhibit a more or less longstanding cultural tradition of democratic governance. To approach the question on the democratic consequences of rising inequality, longitudinal designs are thus clearly preferable (van de Werfhorst & Salverda, Reference Van de Werfhorst and Salverda2012). However, few large surveys exist that include questions about political trust for a broad range of countries with diverging levels and trajectories of inequality over many years.

Still, research that has been able to draw on longitudinal data corroborates the idea that inequality affects democratic orientations. In particular, rising inequality was found to lower political trust (Goubin & Hooghe, Reference Goubin and Hooghe2020) and satisfaction with democracy (Christmann, Reference Christmann2018). Closely related studies show that over‐time changes in inequality are associated with populist party support (Engler & Weisstanner, Reference Engler and Weisstanner2021), and this has partly been attributed to decreasing levels of political trust (Stoetzer et al., Reference Stoetzer, Giesecke and Klüver2021). Other research shows that political trust dipped during the financial crisis in Europe – a time when unemployment and inequality increased in many European countries (Gangl & Giustozzi, Reference Gangl and Giustozzi2021; Hooghe & Okolikj, Reference Hooghe and Okolikj2020).

Why would inequality affect trust in the first place? A prominent argument in the sociological literature holds that inequality creates social dysfunctions because increased social distances come with increased status anxiety and declining social trust (Buttrick & Oishi, Reference Buttrick and Oishi2017; Delhey & Steckermeier, Reference Delhey and Steckermeier2020; Wilkinson & Pickett, Reference Wilkinson and Pickett2010). Although rarely invoked as an explanation for political effects of inequality, studies on populist voting have recently argued that rising inequality has spurred status fears and thereby the likelihood of voting for populist parties (Gidron & Hall, Reference Gidron and Hall2017; Engler & Weisstanner, Reference Engler and Weisstanner2021). Regarding social trust, it could furthermore be argued that if inequality decreases generalized trust, it should indirectly also depress trust in democratic institutions, given that social and political trust have often been argued to be strongly related (Newton et al., Reference Newton, Stolle, Zmerli and Uslaner2018; Zmerli & Newton, Reference Zmerli and Newton2008).

In political science, the currently most influential perspective is the ‘trust‐as‐evaluation’ approach (see van der Meer, Reference van der Meer and Uslaner2018, for a review) that regards citizens’ trust in democratic institutions as the outcome of a substantive evaluation of democratic performance. Citizens extend trust if they perceive political outcomes and processes to meet their expectations, and inequality is regularly seen as one relevant dimension of macroeconomic performance that citizens consider in their evaluation (e.g., Martini & Quaranta, Reference Martini and Quaranta2020). The study by Anderson and Singer (Reference Anderson and Singer2008) provides support for this view, as it has shown that inequality depresses trust and satisfaction with democracy primarily among left‐wing respondents. This fits with an understanding that citizens with egalitarian preferences will expect inequality to be tackled politically and will, therefore, also evaluate the political system on the basis of their substantive policy preferences.

Yet, substantive evaluation may not be the only mechanism to link economic inequality to institutional trust. Anderson and Singer (Reference Anderson and Singer2008) did not only find striking partisan differences in the democratic relevance of inequality, but they also observed that inequality nevertheless depresses trust among right‐leaning respondents – even when economic inequality is not likely to constitute a politically salient outcome to these citizens. This observation clearly is a puzzle to the standard trust‐as‐evaluation perspective (see also Kumlin et al., Reference Kumlin, Stadelmann‐Steffen, Haugsgjerd and Uslaner2018), but the puzzle may be resolved when we broaden our perspective and consider an additional mechanism that operates via citizens’ perceptions of efficacy. More specifically, our key argument here is that citizens may evaluate the democratic process just as much as democratic output. If so, then inequality will be relevant, too, because rising economic inequality is likely to translate into political inequality, which in turn is likely to have consequences for how citizens perceive the responsiveness of the political system and their own capabilities to influence the political process. Against the strong democratic norms of political equality and equity, deteriorating perceptions of the fairness of democratic processes clearly have the potential to depress the level of trust that citizens are placing in the actors and institutions of democratic governance.

The argument that we are making here is in fact far from being novel but is one with a long tradition in political science. According to Dahl (Reference Dahl1971), democracy rests on the premise of intrinsic equality – the idea that every human being is fundamentally equal and that, therefore, the interests of members of a democracy are of equal importance. The democratic norm of political equality does not imply that everyone's demands must be met all the time, but it does mean that in principle, everyone must be able to participate in the political process to make her or his interests heard. In the words of Pitkin, ‘in a representative government the governed must be capable of action and judgment, capable of initiating government activity, so that the government may be conceived as responding to them’ (Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967, p. 232).

The degree to which political systems operate in accord with this requirement is captured by the two interrelated concepts of responsiveness and efficacy. Responsiveness captures how well political actors take citizen sentiment into account and adapt policy decisions accordingly, with responsiveness perceptions referring to the concomitant subjective beliefs (Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Kölln and Turper2015). Political efficacy in turn is capturing citizens’ beliefs that (their) individual action can influence the political process (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Gurin and Miller1954, p. 187). Whereas internal efficacy refers to the belief in one's own capacity to understand and participate in politics, external efficacy is the belief in the potential of ordinary citizens to influence the political process, ‘with an emphasis more on the ultimate fairness of both procedures and outcomes’ (Craig et al., Reference Craig, Niemi and Silver1990, p. 299).

Furthermore, efficacy and responsiveness are intricately linked to inequality. Research on external efficacy and responsiveness perceptions points to the fact that some groups are regularly underrepresented in political debates and outcomes (Goodin & Dryzek, Reference Goodin and Dryzek1980; Goubin, Reference Goubin2020; Norris, Reference Norris2015). Indeed, the unequal responsiveness literature has shown for different contexts that the higher ranks of society find their policy preferences more often mirrored by political decisions than their fellow citizens from modest backgrounds (Elsässer et al., Reference Elsässer, Hense and Schäfer2021; Gilens, Reference Gilens2012; Schakel, Reference Schakel2021; Oser et al., Reference Oser, Feitosa and Dassonneville2023). One way to explain these findings is that those with more economic resources are able to promote policies in their interest and inhibit those policy proposals that would primarily benefit the middle and lower classes (Hacker & Pierson, Reference Hacker and Pierson2010). Another is that political participation requires resources and is therefore skewed towards the better‐off (Brady et al., Reference Brady, Verba and Schlozman1995; Schäfer & Schwander, Reference Schäfer and Schwander2019). Parties have therefore incentives to design policies that cater to the demands of those segments of society that turn out to vote (Schakel & Burgoon, Reference Schakel and Burgoon2022), and unequal responsiveness then is the result of inequality in economic resources translating into inequality in political power (Dahl Reference Dahl2006; Goodin & Dryzek, Reference Goodin and Dryzek1980).

Against this background, it should come as no surprise that rising economic inequality has long been considered to exacerbate the problem of unequal responsiveness. Seminal in this regard was Schattschneider (Reference Schattschneider1960), who first proposed that growing inequality changes the agenda of political conflict and thereby increases the bias in electoral participation, which in turn affects whose interests are represented in political outcomes. Political participation is indeed lower and more skewed in more unequal countries (Schäfer & Schwander, Reference Schäfer and Schwander2019), and other studies have shown that this problem became more severe due to increasing income inequality (Lancee & van de Werfhorst, Reference Lancee and Van de Werfhorst2012; Solt, Reference Solt2008). Also, when rising economic inequality increases the relative power of those with more resources, the repeated experience that certain groups in society get their way more often than others is likely to invoke the perception of a political elite that is disconnected from ordinary citizens, and of a system that is ‘rigged’. That inequality may lead to negative assessments of democratic responsiveness as well as to the diffusion of feelings of powerlessness and cynicism is reflected in empirical research that suggests that both objective economic inequality and subjective perceptions of inequality depress citizens’ perceptions of external efficacy (Loveless Reference Loveless2013; Norris Reference Norris2015).

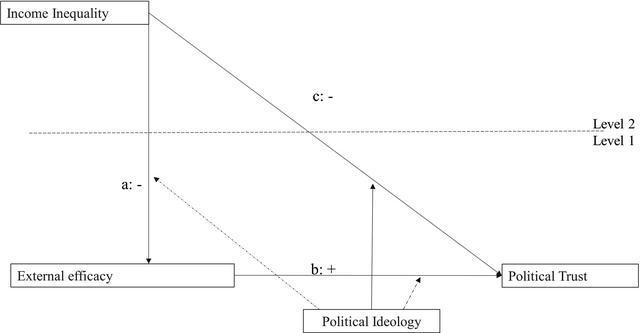

Considering these findings as well as the long‐standing theoretical arguments, it seems plausible to assume that there is a negative effect of income inequality on external efficacy and that declines in efficacy then translate into lower levels of trust. Nevertheless, Goubin (Reference Goubin2020) is, to the best of our knowledge, the only study that empirically examined the whole chain of inequality, efficacy and trust, but her research question and design differ from ours. More specifically, Goubin (Reference Goubin2020) shows that external efficacy is positively related to trust in a cross section of countries, but she examines the role of economic inequality as a moderator for the relationship between efficacy and trust and documents that the positive effect of perceived responsiveness on citizens’ trust is smaller in countries with higher levels of income inequality. The account we seek to advance here, instead, views economic inequality as a macrostructural cause of citizens’ trust in institutions and sees the relationship between inequality and trust to be partly mediated by citizens’ efficacy perceptions. Our theoretical argument is summarized graphically in the path model of Figure 1 or, alternatively, in the following hypotheses:

H1: When income inequality increases over time, political trust declines (total effect = direct effect c + indirect effect ab).

H2: When income inequality increases over time, external efficacy declines (path a).

H3: External efficacy has a positive effect on citizens’ political trust (path b).

H4: By implication of H2 and H3, external efficacy partly mediates the negative effect of income inequality on political trust (path ab, indirect effect).

Figure 1. Multilevel path model of political trust.

Notably, our emphasis on the relevance of an efficacy‐based mechanism does not contradict the trust‐as‐evaluation perspective. Citizens surely have views on desirable macroeconomic conditions on the one hand, but it is likewise plausible that their evaluations of democratic realities depend on the perceived fairness of the democratic process and on whether, or how strongly, the norm and expectation of political equality are being violated. Existing studies clearly relate political trust to perceptions of responsiveness and efficacy (Goubin, Reference Goubin2020; Torcal, Reference Torcal2014), and several scholars have argued that process evaluations may be more important for political support than outcome evaluations in the longer run (Norris, Reference Norris2011; van der Meer & Hakhverdian, Reference van der Meer and Hakhverdian2017).

The difference between output and process evaluation might be important for theorizing the role of political ideology. The standard trust‐as‐evaluation perspective implies the expectation that political ideology will moderate the relationship between inequality and trust in democratic institutions. When political trust is a function of citizens’ evaluations of the outputs of the political system against their expectations (van der Meer, Reference van der Meer and Uslaner2018), left‐leaning citizens should be more negatively affected by high levels of inequality because they value equality as a political goal (cf. Alesina et al., Reference Alesina, Di Tella and MacCulloch2004). In line with this reasoning, Anderson and Singer (Reference Anderson and Singer2008) indeed find that the effect is much more pronounced among left‐wingers. However, the same partisan stratification is not likely to be relevant when the standard of evaluation is one of democratic process rather than democratic output. When manifest inequality leads to unequal responsiveness and depresses citizens’ perceptions of external efficacy, this may affect left‐ and right‐leaning citizens alike, irrespective of whether they consider questions of income inequality as an important political goal. In line with this view, Norris (Reference Norris2015) finds that inequality is a strong depressor of external efficacy in the general population, not just among left‐leaning citizens. Accordingly, we expect a difference between process‐ and performance‐based evaluations with respect to the moderating role of political ideology (also see Figure 1):

-

H5: While political ideology moderates the direct effect between inequality and trust, the indirect effect via efficacy perceptions is non‐partisan and therefore holds uniformly in the citizenry.

Data and methodology

To test these hypotheses, we use individual‐level survey data from rounds 7 to 9 of the ESS (2014, 2016, 2018) to which we merge macroeconomic data from different sources (see below). The ESS has been fielded every other year with newly selected probability samples of the population in participating countries since 2002. By combining the three rounds of the ESS that contain questions on efficacy, we obtain a repeated cross‐sectional dataset for those 22 countries that participated in the ESS at least twice in the period from 2014 to 2018 (see Table A1 in the online Appendix). In conjunction with a model that incorporates the two‐way FE estimator at the aggregate level of the data, this allows us to conduct a longitudinal analysis in a panel‐of‐countries design on the question of how changes in inequality have been affecting changes in political trust in European democracies during the second half of the 2010s.

Operationalization

Dependent variable

The ESS asks respondents to indicate how much trust they have in several of the institutions of democratic governance and measures each item on an 11‐point scale (0 = no trust at all, 10 = complete trust). We construct a political trust index for each respondent based on the sum of their scores for trust in parliament, trust in politicians, and trust in parties, divided by the number of valid responses (Cronbach's α = 0.91). We also perform robustness checks with each item separately.

Independent variables

External efficacy is measured by two questions that ask respondents ‘How much would you say the political system in [country] allows people like you to have a say in what the government does?’ and ‘And how much would you say that the political system in [country] allows people like you to have an influence on politics?’ These are very similar to the items Craig et al. (Reference Craig, Niemi and Silver1990) have shown to be valid and distinct measures of external efficacy. In 2014, answers were recorded on an 11‐point scale. From 2016 onward, the response categories include 1 = ‘Not at all’, 2 = ‘Very little’, 3 = ‘Some’, 4 = ‘A lot’, 5 = ‘A great deal’. We harmonize these variables by normalizing them to range from 0 to 10. The respondents’ average score on the two questions provides us with a continuous measure of their level of perceived external efficacy, also ranging from 0 to 10.

As for income inequality, we use the S80/S20 income share ratio of household disposable income from Eurostat (2022a). The measure reflects the ratio between the share of total income that is accruing to the top 20 per cent of the income distribution and the income share of the bottom 20 per cent. As a robustness test, however, we also replicate our main analyses with the Gini coefficient of household disposable income as obtained from the Standardized World Inequality Database (Solt, Reference Solt2020).

For the moderator variable of political ideology, we follow Anderson and Singer (Reference Anderson and Singer2008) and dichotomize the 11‐point left‐right scale to distinguish left‐leaning respondents (0–2) from centre/right‐leaning respondents (3–10).Footnote 1

Control variables

As individual‐level covariates, we include educational level, household income, social class as well as gender and age. We use a five‐category measure distinguishing between respondents who completed less than secondary education, lower secondary, upper secondary, post‐secondary non‐tertiary education, and tertiary education. We also include a relative measure of household income (country‐specific income quintiles + ‘Missing’). Social class is measured with the five‐class scheme by Oesch (Reference Oesch2006), distinguishing unskilled workers, skilled workers, small business owners, lower service class and upper service class.

We also account for the macro‐economic development of the sampled countries by including the economic performance index (EPI; see Khramov & Lee, Reference Khramov and Lee2013). The EPI summarizes information on economic growth, inflation, unemployment (WDI, 2022) and the budget deficit (IMF, 2022). Further information on the EPI, as well as a list of survey items used in the analysis can be obtained from the online Supporting Information. Descriptive statistics for all variables are included in Table A2 in the online Appendix.

Analytical strategy

The pooled ESS data consist of three hierarchical levels, with individual respondents, nested in country years and countries. We account for this setup by estimating a series of FE regression models that permit us to evaluate the micro‐ and macro‐level correlates of citizens’ political trust while providing adequately clustered standard errors for hypothesis testing. Employing country‐ and survey‐wave FE incorporates the feature of a static panel data model at the aggregate level of countries. Country FEs serve the twin purpose of properly isolating the longitudinal (within‐unit) from the cross‐sectional (between‐unit) effects of any macro‐level covariate while simultaneously controlling for any observed or unobserved confounders that are time constant at the country level (see Gangl, Reference Gangl2010; Greene, Reference Greene2018; Woolridge, Reference Woolridge2010). Country FEs afford this by removing all between‐country variation from the analysis. As a result, the country FEs control for any time‐invariant and possibly idiosyncratic country characteristics that create whatever is temporally persistent in a country's democratic culture throughout our study.

In addition, adopting a FE specification implies that longitudinal, within‐unit variation over time is the sole informational basis for estimating a regression coefficient to describe the association between a covariate and the outcome variable of interest. FE models effectively de‐mean all the variables in the regression model, thus providing estimates of the correlation between (over time) within‐unit changes in the dependent variable and (over‐time) within‐unit changes in the independent variable. An FE model, therefore, is the equivalent of adopting a longitudinal research design that allows us to estimate the effect of observable changes in inequality on changes in political trust in a before‐and‐after comparison within units, that is, at the aggregate level of countries in our case. In the context of a multilevel model for repeated cross‐sectional data, where controls for individual‐level covariates also amount to an implicit control for compositional changes in the citizenry, we in fact specifically estimate the contextual (or sociotropic) effect of income inequality on political trust, net of citizens’ SES or other demographic characteristics and any egocentric political motivations that may come with them.

Within this broad approach, our analytical strategy then is twofold: We first show a series of regression models to evaluate each hypothesized path of our theoretical model. In a second step, we test the mediation channel via efficacy perceptions by applying a causal mediation analysis that uses the mediate package in R (Imai et al., Reference Imai, Keele and Tingley2010; Tingley et al., Reference Tingley, Yamamoto, Hirose, Keele and Imai2014). Specifically, we simulate the model parameters (the direct effect of inequality on trust and the indirect effect via efficacy perceptions) from the regression models for the outcome and mediator based on their sampling distribution. In total, we obtain a sample of 1000 of these parameters. For each of these draws and each unit in the dataset, we simulate the potential mediator values and the potential outcomes (based on the simulated mediator values) and calculate the average causal mediation effect across the predictions for all respondents. This estimate is one of 1000 Monte Carlo draws so that we obtain a distribution of 1000 mediation effects from which we then calculate point estimates and confidence intervals (the mean and percentiles of that distribution) of the mediation effect (see Imai et al., Reference Imai, Keele and Tingley2010, p. 328, for details on the algorithm).

With this setup, our estimates become a practically useful and informative approximation of the likely range of the causal effect of income inequality on external efficacy and trust. Our two‐way FE design and further controls should help isolate our inferences against many obvious confounders, even as some inferential threats inevitably remain. The two most important assumptions we need to retain to give our estimates a causal interpretation are that there are no omitted time‐varying confounders and that reverse causation is absent. Concerning the former, concomitant political events would seem the primary candidate factor. We thus provide a range of additional analyses to explore the robustness of our findings when considering other time‐varying covariates or when conducting jackknife estimation to test against the presence of influential single‐country cases. For reverse causality, we must acknowledge the principal possibility that changes in trust may (also) precede changes in inequality, for example, when high levels of trust enable democratic governments to implement far‐reaching political interventions to combat inequality. While theoretically possible, reverse causation seems not likely to be a dominant factor in our study. The short (4‐year) observation window of our data should render it much more likely that we see associations because citizens react to changes in inequality (which they can do without much delay) rather than the other way. That principle optimism notwithstanding, we do not wish to claim a similar level of confidence about strictly causal conclusions from our mediation analysis. Among the necessary assumptions of causal mediation analysis, data limitations prevent us from employing a full set of candidate mediators (see Cunningham, Reference Cunningham2021; Imai et al., Reference Imai, Keele and Tingley2010). Accordingly, we will more cautiously propose a traditional reading of ‘indirect effects’ (see Kline, Reference Kline2015) for this part of our analysis. However, as with the other elements of our analyses, a range of robustness checks will be applied to help corroborate our main reading of the evidence.

Results

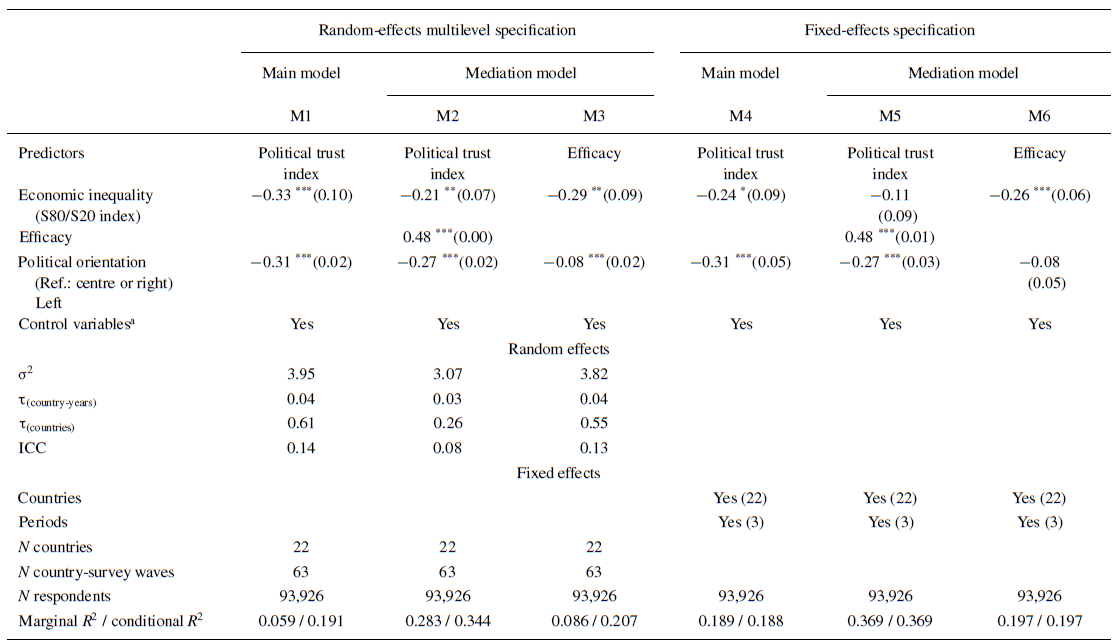

We begin with a series of models to obtain estimates of the individual path coefficients in our hypothesized mediation (Table 1 shows the relevant coefficients; full results are shown in Table A3). We do so first with a standard random effects (i.e., multilevel, RE) specification to provide a baseline, which we then compare to our preferred specification of the more stringent FE regressions.

Table 1. A mediation model for inequality, efficacy and political trust in 22 European democracies.

Models control for economic performance, gender, age, level of education, household income, social class. Full results in Table A3.

* p < 0.05;

** p < 0.01;

*** p < 0.001.

The total effect of income inequality on trust, as obtained from the RE model (Model 1), is −0.326 (

![]() $p\hspace*{0.28em}<$ 0.001). Model 2 includes external efficacy in the trust model, which yields an estimate of the direct effect of inequality on trust (

$p\hspace*{0.28em}<$ 0.001). Model 2 includes external efficacy in the trust model, which yields an estimate of the direct effect of inequality on trust (

![]() $\beta \; = $ −0.209,

$\beta \; = $ −0.209,

![]() $p\; = $ 0.006). The results also show that efficacy has a strong positive effect on trust (

$p\; = $ 0.006). The results also show that efficacy has a strong positive effect on trust (

![]() $\beta \; = $ 0.48,

$\beta \; = $ 0.48,

![]() $p<$ 0.001). The regression of external efficacy on income inequality (Model 3) indicates a negative and significant effect of income inequality (

$p<$ 0.001). The regression of external efficacy on income inequality (Model 3) indicates a negative and significant effect of income inequality (

![]() $\beta \; = $ −0.287,

$\beta \; = $ −0.287,

![]() $p\; = $ 0.003). In sum, the multilevel models presented so far support the hypotheses that inequality negatively affects external efficacy and trust and that efficacy positively affects political trust. It is important to note that these estimates are net of the demographic and socioeconomic control variables included. That is, compositional differences are accounted for, and the effects of inequality can be considered genuine contextual (i.e., sociotropic) effects.

$p\; = $ 0.003). In sum, the multilevel models presented so far support the hypotheses that inequality negatively affects external efficacy and trust and that efficacy positively affects political trust. It is important to note that these estimates are net of the demographic and socioeconomic control variables included. That is, compositional differences are accounted for, and the effects of inequality can be considered genuine contextual (i.e., sociotropic) effects.

Nonetheless, the estimates of the contextual effects obtained through this random‐effects specification are a mixture of within and between effects (Fairbrother, Reference Fairbrother2014). As such, it remains unclear whether the effect of inequality is due mainly to different levels of inequality between countries or to changes in inequality over time. The next step in our analysis requires properly isolating the longitudinal component of the effect of inequality by including country and wave FE. As described in more detail in the methodological section, we consequently estimate the average effect of a change in inequality within a country on political trust over time.

As shown in Models 4–6 in Table 1, the FE models confirm the results of the random effects specification. As the estimates are now based on variation within countries over time only, the contextual effects are considerably smaller. It should be noted that variance decomposition through a random intercept‐only model indicates that variation within countries over time accounts for only 1.6 per cent of the overall variance in political trust, whereas between country variance accounts for 17.7 per cent.

The total effect of inequality on trust, for example, is reduced from −0.326 (

![]() $p\hspace*{0.28em}<$ 0.001) in Model 2 to −0.237 (

$p\hspace*{0.28em}<$ 0.001) in Model 2 to −0.237 (

![]() $p\; = $ 0.012 in Model 5). To illustrate the substantive meaning of this effect, the model predicts that an increase of 0.99 on the S80/S20 (as in Lithuania in the period covered by our data, i.e., 2014–2018) would decrease average trust by −0.23 points on the 10‐point index, or about 2.3 percentage points. Conversely, for Estonia, where inequality declined from 6.48 to 5.07 between 2014 and 2018, the model predicts an increase in trust by about 3.3 percentage points.

$p\; = $ 0.012 in Model 5). To illustrate the substantive meaning of this effect, the model predicts that an increase of 0.99 on the S80/S20 (as in Lithuania in the period covered by our data, i.e., 2014–2018) would decrease average trust by −0.23 points on the 10‐point index, or about 2.3 percentage points. Conversely, for Estonia, where inequality declined from 6.48 to 5.07 between 2014 and 2018, the model predicts an increase in trust by about 3.3 percentage points.

When responsiveness perceptions are included in Model 5, the direct effect of income inequality turns insignificant (

![]() $\beta \; = $ −0.112,

$\beta \; = $ −0.112,

![]() $p\; = $ 0.205). In Model 6, we regress external efficacy on income inequality and find a negative and significant effect (

$p\; = $ 0.205). In Model 6, we regress external efficacy on income inequality and find a negative and significant effect (

![]() $\beta \; = $ −0.261,

$\beta \; = $ −0.261,

![]() $p\hspace*{0.28em}<$ 0.001). Considering that these estimates are based on a rigid model specification and only within variation in a relatively short period of time (2014–2018), the results so far support our theoretical expectations: There is a negative effect of inequality on trust and external efficacy, as well as a positive effect of efficacy on trust (

$p\hspace*{0.28em}<$ 0.001). Considering that these estimates are based on a rigid model specification and only within variation in a relatively short period of time (2014–2018), the results so far support our theoretical expectations: There is a negative effect of inequality on trust and external efficacy, as well as a positive effect of efficacy on trust (

![]() $\beta \; = $ 0.48,

$\beta \; = $ 0.48,

![]() $p<$ 0.001). Moreover, the estimate for the direct effect of income inequality on trust is almost half that of the total effect, thus indicating that external efficacy provides a channel through which some of the inequality effect is transmitted. In order to formally estimate and test this indirect effect, we now turn to the mediation analysis based on the FE models.

$p<$ 0.001). Moreover, the estimate for the direct effect of income inequality on trust is almost half that of the total effect, thus indicating that external efficacy provides a channel through which some of the inequality effect is transmitted. In order to formally estimate and test this indirect effect, we now turn to the mediation analysis based on the FE models.

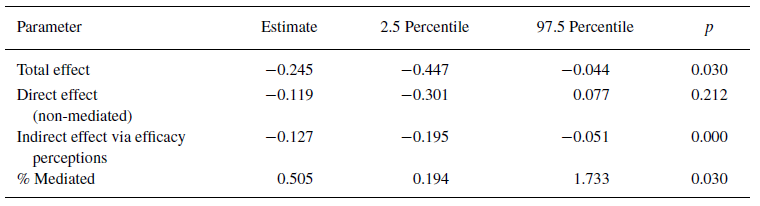

Table 2 shows the results of the mediation analysis. The simulation‐based results differ only minimally from the results in Table 1. The total effect is negative and remains significant

![]() $(\beta = $ −0.245,

$(\beta = $ −0.245,

![]() $p<$ 0.001). The estimated mediation or indirect effect is

$p<$ 0.001). The estimated mediation or indirect effect is

![]() $\beta \; = $ −0.127 (

$\beta \; = $ −0.127 (

![]() $p<$ 0.001), corresponding to about 51 per cent of the effect of inequality on political trust being attributable to external efficacy. Accordingly, the estimated direct effect of inequality on trust is reduced to

$p<$ 0.001), corresponding to about 51 per cent of the effect of inequality on political trust being attributable to external efficacy. Accordingly, the estimated direct effect of inequality on trust is reduced to

![]() $\beta \; = $ −0.119, turning it insignificant (

$\beta \; = $ −0.119, turning it insignificant (

![]() $p\; = $ 0.212). To investigate whether political ideology moderates the relationship between inequality, trust and efficacy, we next fit the same set of models separately for left‐wing respondents and all others.

$p\; = $ 0.212). To investigate whether political ideology moderates the relationship between inequality, trust and efficacy, we next fit the same set of models separately for left‐wing respondents and all others.

Table 2. Inequality, efficacy and political trust: A causal mediation analysis (based on N = 1000 simulations).

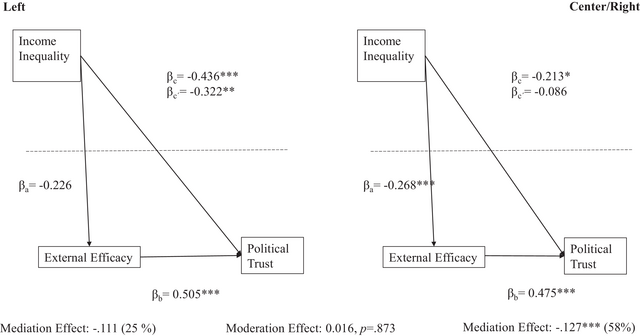

Figure 2 summarizes the main results from the FE models through path coefficients (complete results shown in Tables A4 and A5). Among respondents who identify as left (left panel), the total effect of income inequality is

![]() $\beta \; = $ −0.436 (

$\beta \; = $ −0.436 (

![]() $p<$ 0.001). Accounting for external efficacy reduces this effect to

$p<$ 0.001). Accounting for external efficacy reduces this effect to

![]() $\beta \; = $ −0.322 (

$\beta \; = $ −0.322 (

![]() $p\hspace*{0.28em}=\hspace*{0.28em}$0.005). Again, we find that efficacy strongly affects political trust

$p\hspace*{0.28em}=\hspace*{0.28em}$0.005). Again, we find that efficacy strongly affects political trust

![]() $\beta \; = {\mathrm{\;}}$0.505 (

$\beta \; = {\mathrm{\;}}$0.505 (

![]() $p\hspace*{0.28em}<$ 0.001). The effect of inequality on efficacy is negative but statistically insignificant (

$p\hspace*{0.28em}<$ 0.001). The effect of inequality on efficacy is negative but statistically insignificant (

![]() $\beta \; = $ −0.226,

$\beta \; = $ −0.226,

![]() $p\; = $ 0.108). For the indirect effect, the causal mediation analysis yields an estimate of

$p\; = $ 0.108). For the indirect effect, the causal mediation analysis yields an estimate of

![]() $\beta \; = $ −0.111 (

$\beta \; = $ −0.111 (

![]() $p\; = $ 0.236). Here, about 25 per cent of the total effect of inequality on trust are mediated through external efficacy. To anticipate the results from further analyses and the discussion below, the mediation effect is significant once Lithuania is excluded (

$p\; = $ 0.236). Here, about 25 per cent of the total effect of inequality on trust are mediated through external efficacy. To anticipate the results from further analyses and the discussion below, the mediation effect is significant once Lithuania is excluded (

![]() $\beta \; = $ −0.227,

$\beta \; = $ −0.227,

![]() $p < $ 0.001; see Section 4 in the online Supporting Information).

$p < $ 0.001; see Section 4 in the online Supporting Information).

Figure 2. Partisan differences in the relationships between inequality, efficacy and political trust: path model representations.

Among non‐left respondents, the total effect of income inequality on trust is much weaker (

![]() $\beta \; = $ −0.213;

$\beta \; = $ −0.213;

![]() $p\; = $ 0.033) and its direct effect is insignificant (

$p\; = $ 0.033) and its direct effect is insignificant (

![]() $\beta \; = $ −0.086;

$\beta \; = $ −0.086;

![]() $p\; = $ 0.346). There is a clear negative effect of inequality on external efficacy (

$p\; = $ 0.346). There is a clear negative effect of inequality on external efficacy (

![]() $\beta \; = $ −0.261,

$\beta \; = $ −0.261,

![]() $p < $ 0.001). The mediation or indirect effect among right‐wing respondents is estimated to be −0.127 (

$p < $ 0.001). The mediation or indirect effect among right‐wing respondents is estimated to be −0.127 (

![]() $p < $ 0.001), with 58 per cent of the effect of inequality on trust being mediated through external efficacy. It is mainly due to the smaller total effect of inequality on trust that the proportion mediated by external efficacy is larger among centre and right‐wing respondents. However, the coefficients of the indirect effects are similar among the two groups.

$p < $ 0.001), with 58 per cent of the effect of inequality on trust being mediated through external efficacy. It is mainly due to the smaller total effect of inequality on trust that the proportion mediated by external efficacy is larger among centre and right‐wing respondents. However, the coefficients of the indirect effects are similar among the two groups.

A formal z‐test of the moderation effect of political orientation shows the difference in indirect effects to be statistically insignificant (

![]() $\beta \; = $ 0.016,

$\beta \; = $ 0.016,

![]() $p\; = $ 0.873; see Fairchild & MacKinnon Reference Fairchild and MacKinnon2009). Based on both the small size of the moderation effect and the formal test, we thus conclude that the indirect effect of inequality on trust does not depend on political ideology.

$p\; = $ 0.873; see Fairchild & MacKinnon Reference Fairchild and MacKinnon2009). Based on both the small size of the moderation effect and the formal test, we thus conclude that the indirect effect of inequality on trust does not depend on political ideology.

Robustness checks

To summarize, our results suggest that rising income inequality reduces trust in democratic institutions and that this effect is, to a large part, explained by inequality's indirect effect via external efficacy. Importantly, this indirect effect is independent of ideology, whereas a direct effect is observable predominantly among left‐wing respondents.

These findings replicate across a range of model specifications (see Table A6 in the online Appendix): We repeated the analysis with the Gini coefficient of disposable income and the p90p10 income ratio (Eurostat, 2022b) as alternative indicators for income inequality. We further conducted the analyses for the three trust items separately and tested different cutoff points for the left‐right orientation. In addition, we fitted models with different control variables: We substituted the EPI with the unemployment rate and GDP growth. To test whether our results were driven by changes in the quality of democratic institutions, we included the V‐Dem's (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Grahn, Hicken, Kinzelbach, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Neundorf, Paxton, Pemstein, Rydén, vonRömer, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Sundström, Tzelgov, Uberti, Wang, Wig and Ziblatt2022) liberal democracy index as a time‐varying control. A different way to account for this is to exclude countries that experienced a decline in their Freedom House status, which is commonly used to classify liberal democracies (Norris, Reference Norris2011). We thus refit our models while excluding Hungary, for which the status changed in 2018. As a further robustness test, we included the annual number of first‐time asylum applicants per 1 million inhabitants (standardized) as a time‐varying control variable. The reason is that from 2015 onward, several European countries were subject to a sudden increase in immigration rates, potentially leading to increases in the Gini coefficient and, particularly among non‐left citizens, decreased political trust. Except for small changes in the parameter estimates, the above specifications all replicate our main analysis.

To further test the sensitivity of our results to potentially influential cases, we refitted the causal mediation analysis while excluding one country at a time (‘leave‐one‐out jackknife’). The results for each of the 22 models can be found in the online Supporting Information. The only notable change is that the coefficient for the indirect effect among left‐wing respondents doubles in size and becomes significant once Lithuania is excluded. In conjunction with the small and insignificant moderation effect, this reinforces the conclusion that the efficacy‐based mechanism is indeed non‐partisan.

To rule out alternative explanations, we tested whether the social‐psychological mechanism could account for the effects of inequality on trust. As described in the theory section, the influential ‘spirit‐level thesis’ states that inequality leads to ‘social dysfunction’ because it increases the distances between social groups, which increases status anxiety and reduces social trust (Wilkinson & Pickett, Reference Wilkinson and Pickett2010; see also van de Werfhorst & Salverda, Reference Van de Werfhorst and Salverda2012). Models with the status‐seeking index (cf. Paskov et al., Reference Paskov, Gërxhani and van de Werfhorst2017) and social trust index as mediators indicate, however, that this mechanism cannot explain the relationship between inequality and trust: The proportion mediated amounts to 0 per cent and 4 per cent, respectively.

We further tested the alternative hypothesis that the mechanism via efficacy is affected by economic performance more generally. We did this by using the unemployment rate and GDP growth as treatment variables in a mediation model. We do not find significant associations with political trust in either model, but efficacy does significantly reduce the effect of GDP growth (55 per cent mediated). This does not, in fact, question our results since we do not claim that inequality is a panacea that fully accounts for efficacy or trust. Because our models show that economic inequality significantly affects trust via efficacy even after controlling for (different indicators of) economic performance, our conclusions remain the same.

Lastly, we reiterate that our main argument states that economic inequality reduces trust because it affects individual perceptions of ordinary citizens' potential influence on political decisions and thus perceptions of the fairness of the democratic process. As a final test, we aimed to replicate the proposed causal chain at the aggregate level. The V‐dem dataset contains expert evaluations of the degree to which political power in a country depends on socioeconomic position (v2pepwrses; for more information, see Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, Fish, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Grahn, Hicken, Kinzelbach, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Neundorf, Paxton, Pemstein, Rydén, vonRömer, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Sundström, Tzelgov, Uberti, Wang, Wig and Ziblatt2022). If our theoretical argument is correct, we should see that income inequality increases political inequality and that this, in turn, decreases political trust. Table A7 in the online Appendix shows the results from an aggregate mediation model for the period from 2004 to 2018. The model controls for GDP per capita and period effects. The results indicate that income inequality has a significant total effect on political trust (

![]() $\beta \; = $ −0.179,

$\beta \; = $ −0.179,

![]() $p<$ 0.05) and that it also strongly affects the indicator measuring political inequality (

$p<$ 0.05) and that it also strongly affects the indicator measuring political inequality (

![]() $\beta \; = $ −0.121,

$\beta \; = $ −0.121,

![]() $p<$ 0.001). When political inequality is introduced in the model for political trust, the effect of inequality is reduced to

$p<$ 0.001). When political inequality is introduced in the model for political trust, the effect of inequality is reduced to

![]() $\beta \; = $ −0.128 (

$\beta \; = $ −0.128 (

![]() $p=$ 0.12). The indirect effect of inequality on political trust, via inequality in political power, is

$p=$ 0.12). The indirect effect of inequality on political trust, via inequality in political power, is

![]() $\beta \; = $ −0.05 (

$\beta \; = $ −0.05 (

![]() $p<$ 0.01), or 27 per cent. While pointing out that this model uses a sparse set of controls and that aggregate analyses do not permit inferences about individual‐level processes, we see these results as further support for our main argument.

$p<$ 0.01), or 27 per cent. While pointing out that this model uses a sparse set of controls and that aggregate analyses do not permit inferences about individual‐level processes, we see these results as further support for our main argument.

Discussion and conclusions

It has long been theorized that democratic legitimacy and stability may be threatened if economic inequality translates into political inequality. By now, several empirical studies indicate a negative relationship between income inequality and indicators of political support. In this article, we re‐examined this relationship by focusing on political trust and found a robust negative effect of changes in inequality on changes in political trust. We further contributed to the literature by bringing in efficacy as a critical mediator in the causal chain from macroeconomic inequality to citizen trust. In doing so, we have advanced a theoretical argument to complement the currently dominant perspective that views trust in institutions as the result of a rational evaluation of output performance based on political preferences.

We have argued that this type of substantial output‐based evaluation is not the only mechanism through which inequality may affect citizens’ trust in democratic institutions. Instead, we emphasized the importance of considering efficacy – understood as a more process‐based evaluation – to advance our understanding of this relationship. In doing so, we have drawn on a strand of literature that regards economic inequality as potentially threatening democratic fundamentals by translating into unequal resources and consequently into unequal political influence and representation. From this perspective, economic inequality may affect citizens’ perceptions of the responsiveness of the political system and of their own potential to influence political processes. As captured by measures of external efficacy, inequality would thus erode political trust by depressing citizens’ evaluations of the fairness of the democratic process.

We drew on time‐series cross‐sectional data from the ESS to test these hypotheses. FE regression models confirmed that inequality has a negative effect on both trust and efficacy over time, while efficacy has a positive effect on trust. A causal mediation analysis showed a significant indirect effect of inequality on trust via efficacy perceptions. Separate analyses for left‐wing and centre/right‐wing respondents revealed that inequality's indirect effect via efficacy does not depend on political orientation, while a direct effect remains only for those on the left.

These findings contribute to contemporary debates in three important ways. First, our results corroborate previous findings that objective income inequality depresses trust in political institutions and expand on these by implementing a rigorous longitudinal design. Given the extensive controls for observables and country‐specific unobservables as afforded within the context of a FE regression specification, this substantiates a causal role of inequality for trust. We consider this causal interpretation to be credible insofar as our short observation window makes reverse causation (from trust to inequality) unlikely and given the extensive robustness tests against other potential time‐varying confounders and the presence of influential cases.

Second, these results are the first to empirically confirm the existence of an efficacy‐based transmission channel from inequality to trust. In doing so, we complement existing accounts of trust by showing that process and output evaluations co‐occur.

Third, we can show that the efficacy‐based mechanism is independent of political orientation. Drawing attention to the largely non‐partisan transmission channel of citizens’ efficacy perceptions may provide a resolution for the empirical puzzle why inequality also depresses political trust among right‐leaning citizens, for whom (rising) inequality would presumably not be an important political problem in the first place (see Kumlin et al., Reference Kumlin, Stadelmann‐Steffen, Haugsgjerd and Uslaner2018). Even among those distant from egalitarian ideology, our results show that objective inequality undermines trust, albeit more indirectly. These findings align with recent criticism of the ‘emerging consensus’ on the superiority of subjective perceptions over objective inequality (Weisstanner & Armingeon, Reference Weisstanner and Armingeon2022). By contrast, our results show that neither a correct perception of the degree of economic inequality nor a political preference for economic equality are strictly necessary for objective inequality to affect democratic attitudes. As objective economic inequality affects external efficacy, it indirectly affects political trust even among those for whom inequality is, for ideological reasons, not a major concern.

While we believe these contributions to be important, our study faces certain limitations. First, unlike for the effect of inequality on trust, we cannot draw strictly causal conclusions from the mediation analysis as data limitations prevent us from employing a full set of candidate mediators. Relatedly, contrary to our assumptions, trust may precede efficacy. For example, when a change in government happens and the party a respondent voted for takes the lead after having been in opposition before, citizens may adapt their feelings of external efficacy to their increased trust in political institutions. We consider this causal direction less likely, yet we cannot rule it out entirely.

Finally, our data consist of a limited number of European countries and a short period of time. Levels of income inequality in Europe are comparatively low and the more drastic changes in inequality occurred prior to the period under investigation. Yet, even in this setting, which can be considered a least‐likely design, our findings are in line with our theoretical propositions and highly robust. Nevertheless, future studies should test whether the proposed mechanism holds in different contexts and periods.

Despite these limitations, we believe that this paper makes an important contribution by providing new evidence showing that objective economic inequality has the potential to erode democratic support and that external efficacy plays a key role therein. This is practically relevant, as the impact of rising income inequality may be cushioned through interventions that raise perceptions of efficacy. Recognizing this efficacy‐based transmission channel can also contribute to political sociology more generally. Placing a perspective on citizens’ evaluation of political power and fair democratic processes alongside the perspective of output‐based evaluations may enrich the argument that democratic stability may be undermined when economic inequality is getting translated into political power and inequality of representation.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this research have been presented at the AS Conference ‘Cohesive Societies?’ in 2021 and the ‘Workshop on Perceptions and Policy Preferences’ at the University of Hamburg in 2021. We thank all participants, Carlotta Giustozzi, Claudia Traini, and the three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. We also thank Elisa Ebertz, Clara Eul and Emir Zecovic for valuable research assistance in the project.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The data and syntax are available on OSF (DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/F4NUA).

Funding Information

This study is part of the project POLAR: Polarization and its discontents: does rising economic inequality undermine the foundations of liberal societies? that has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (Grant agreement No. 833196).

Ethics approval statement

Ethical approval is not applicable to this article.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supplementary information