Introduction

Depression is a major source of morbidity affecting daily functioning and quality of life in the general (i.e., nononcology) population. An estimated 8.4% of U.S. adults suffer from depression, and only 28.7% of this population receive treatment for it, indicating a substantial gap in care (Olfson et al. Reference Olfson, Blanco and Marcus2016). The prevalence of depression is even higher among patients with cancer. For example, a meta-analysis of 66 studies revealed a 16.3% depression rate across all cancers (Mitchell et al. Reference Mitchell, Chan and Bhatti2011), with higher rates of depression found in patients with certain cancer types, such as lung, brain, and genitourinary tract (Zeilinger et al. Reference Zeilinger, Oppenauer and Knefel2022). Depression is associated with decreased adherence to cancer treatment, increased lengths of medical hospital stays, and increased risk of suicide (Smith Reference Smith2015). Furthermore, depression is associated with worse survival outcomes for all cancers (Walker et al. Reference Walker, Mulick and Magill2021).

In 2012, the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer established psychosocial distress screening as a standard. As cancer programs became more effective in identifying patients in psychosocial distress, the challenges of providing comprehensive psychosocial care to a large population of these patients have become more apparent, with more patients than resources available (Zebrack et al. Reference Zebrack, Kayser and Padgett2016; Kayser et al. Reference Kayser, Brydon and Moon2020).

The Collaborative Care Model (CoCM), a specific type of integrated care that was first developed in the 1990s as a way to increase access to behavioral health care in primary care settings, presents a systematic approach to delivering evidence-based psychosocial care in oncology (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Fann and Nelson2023). Extensive empirical research has shown the model to be effective in treating several mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD in various medical settings (Archer et al. Reference Archer, Bower and Gilbody2012; Thota et al. Reference Thota, Sipe and Byard2012; van et al. Reference van, van der Sluijs and Castelijns2018). Moreover, six randomized clinical trials (RCTs) to date have demonstrated the model’s effectiveness in treating symptoms of depression for oncology patients (Ell et al. Reference Ell, Xie and Quon2008; Strong et al. Reference Strong, Waters and Hibberd2008; Fann et al. Reference Fann, Fan and Unützer2009; Kroenke et al. Reference Kroenke, Theobald and Wu2010; Sharpe et al. Reference Sharpe, Walker and Holm Hansen2014; Walker et al. Reference Walker, Hansen and Martin2014). In these RCTs, collaborative care had a depression response rate of 35–53% compared to 15–35% at 3 months for usual care (Fann et al. Reference Fann, Fan and Unützer2009; Strong et al. Reference Strong, Waters and Hibberd2008; Kroenke et al. Reference Kroenke, Theobald and Wu2010; Walker et al. Reference Walker, Hansen and Martin2014), and a depression response rate of 42–62% compared to 17–41% at 6 months for usual care (Ell et al. Reference Ell, Xie and Quon2008; Fann et al. Reference Fann, Fan and Unützer2009; Kroenke et al. Reference Kroenke, Theobald and Wu2010; Sharpe et al. Reference Sharpe, Walker and Holm Hansen2014). As a result, the American Psychosocial Oncology Society task force determined that the Collaborative Care Model has the strongest evidence for providing care efficiently for a large population of patients (Pirl et al. Reference Pirl, Greer and Gregorio2020). Additionally, American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines for managing depression and anxiety in patients with cancer recommends the implementation of a stepped-care approach (Pirl et al. Reference Pirl, Nekhlyudov and Rowland2023), which is consistent with how Collaborative Care Models function and deliver care.

Despite this evidence, few cancer centers have implemented collaborative care to deliver psychosocial oncology services. As a shared care model involving multiple clinical services, implementation of collaborative care requires clear delineation of which service “owns” the program and how it will be financed. Additionally, the relative unfamiliarity of collaborative care in the cancer setting necessitates substantial training (Walker et al. Reference Walker, Hobbs and Wanat2022). As a result, there is limited data on real-world outcomes for depression in collaborative care in oncology.

To address current mental health care gaps in oncology, collaborative care was implemented at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI), incorporating palliative care into the team and creating the Supportive Oncology Collaborative (SOC). The SOC builds on the collaborative care framework by including palliative care and psychology consultants to the weekly case review meetings, allowing for a more comprehensive supportive care approach that addresses the full spectrum of social, emotional, and physical problems. Of note, the SOC increased access to supportive care at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute for historically underserved areas (Lally et al. Reference Lally, Macip-Rodriquez and Wu2024). To assess the effectiveness of this collaborative care program, we aimed to benchmark the rate of depression responses associated with the SOC, a real-world collaborative care model in oncology, against those reported in RCTs. We chose to focus on depression because it is by far the most studied outcome measure in literature on collaborative care in oncology (Ell et al. Reference Ell, Xie and Quon2008; Strong et al. Reference Strong, Waters and Hibberd2008; Fann et al. Reference Fann, Fan and Unützer2009; Kroenke et al. Reference Kroenke, Theobald and Wu2010; Sharpe et al. Reference Sharpe, Walker and Holm Hansen2014; Walker et al. Reference Walker, Hansen and Martin2014).

Methods

The SOC was developed with the four fundamental components of collaborative care including: (1) a care manager, served by an oncology social worker, who provides behavioral health interventions and facilitates communication among team members and patients; (2) population-based care through the use of a dashboard connected to the electronic medical record, which acts as the registry to systematically track and monitor patient progress; (3) measurement-based care utilizing validated patient-reported outcome measures including the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) to guide clinical decision-making (Kroenke et al. Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001; Spitzer et al. Reference Spitzer, Kroenke and Williams2006); and (4) regular case review meetings between the care manager and consulting specialists, including psychiatry, to discuss patient treatment plans.

This study was conducted at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Merrimack Valley regional campus site, 1 of 6 regional campus sites. The study was reviewed by the Office of Human Research Studies (OHRS) and was exempted from full Institutional Review Board review as it involved the retrospective analysis of de-identified data collected from electronic medical records. Therefore, requirement for informed consent was waived.

Merrimack Valley was chosen for this study because it was the first SOC location established at DFCI when the program first begun as a pilot in 2020. Patients are initially identified either by universal distress screening or by referral from the oncology team. From there, the SOC care manager, an oncology social worker, conducts a comprehensive psychosocial assessment which includes the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 and provides counseling as needed (Kroenke et al. Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001). Patients continue to be monitored with PHQ-9 and GAD-7 assigned to their social work visits. The questionnaires are assigned at a frequency of no more than every 2 weeks.

To identify patients who were depressed and for whom data was available to track their depression response, an initial report was generated for all patients seen at Merrimack Valley with 2 or more PHQ-9 scores on file within a 12-month period between January 1, 2022 and December 31, 2023, including only those with an initial PHQ-9 score of 10 or above, corresponding to at least moderate depression (Hinz et al. Reference Hinz, Mehnert and Kocalevent2016; Grapp et al. Reference Grapp, Terhoeven and Nikendei2019). Patient data were eligible for analyses if they were adults aged 18 years and over, if their initial PHQ-9 score was collected within 2 weeks (i.e., before or after) of their psychosocial assessment with the oncology social worker, and if they had at least two encounters with a member of the oncology, radiation oncology, or surgical oncology team within 6 months of meeting with a member of the SOC team (as the scope of this study is on patients undergoing active cancer treatment). Patient data were screened chronologically based on the timing of their first PHQ-9 score. Sixty-seven patients were screened until the data of 50 patients were eligible for analysis.

The primary outcome was the depression response rate, defined as the percentage of patients with 50% reduction in depressive symptoms as indicated by PHQ-9 score at 12 weeks and 24 weeks following the initial PHQ-9 score. Since this study relied on retrospective chart review of real-world clinical data, the PHQ-9 scores available were not obtained at standardized time points. Therefore, the last observation carried forward (LOCF) method was utilized to assign PHQ-9 to either the 12-week or 24-week time points (Shao and Zhong Reference Shao and Zhong2003; Streiner Reference Streiner2014). The depression response rates were then compared against the depression response rates in the “intervention” arm of RCTs on collaborative care in oncology settings, when available (Ell et al. Reference Ell, Xie and Quon2008; Strong et al. Reference Strong, Waters and Hibberd2008; Fann et al. Reference Fann, Fan and Unützer2009; Kroenke et al. Reference Kroenke, Theobald and Wu2010; Sharpe et al. Reference Sharpe, Walker and Holm Hansen2014; Walker et al. Reference Walker, Hansen and Martin2014).

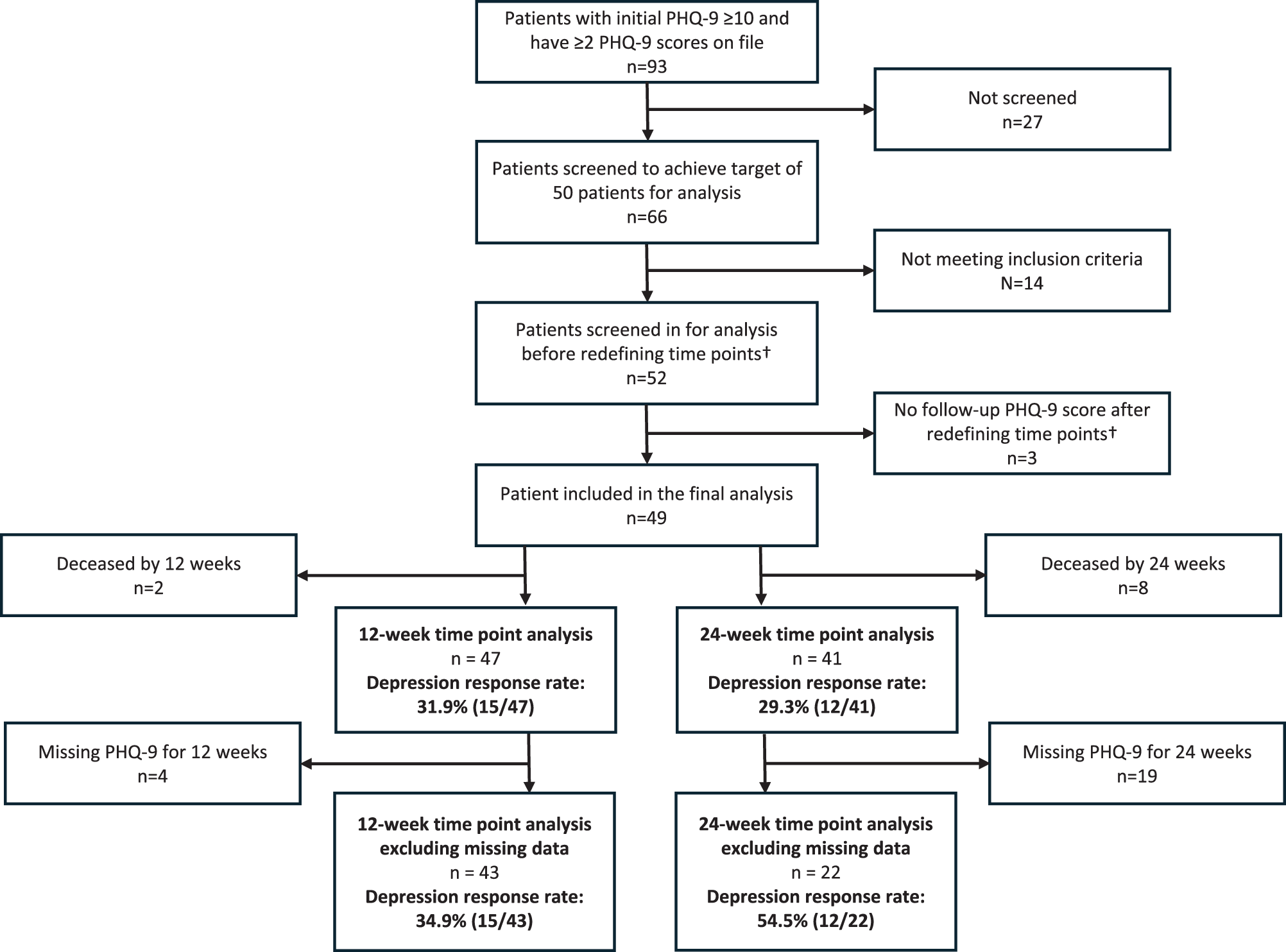

Among the 49 patients ultimately included for final analysis, 2 out of 49 patients were deceased by 12 weeks, and 8 out of 49 patients were deceased by 24 weeks (Fig. 1). These patients were excluded from analysis at each of the time points so that the analysis represented the population who were able to engage with psychosocial care at each time point.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of patient data screened and analyzed. Data report of all patients who had encounter data with a member of the SOC team at Merrimack Valley from January 2022 to December 2023, with ≥ 2 PHQ-9 scores within a 12-month period. †Initial screening was based on timepoint of 3 months and 6 months, which we later redefined as 12 weeks and 24 weeks to maintain consistency in the number of days between time points.

There were also 4 out of 47 patients missing PHQ-9 scores at 12 weeks and 19 out of 41 patients missing PHQ-9 scores at 24 weeks. Given the substantial proportion of PHQ-9 scores missing, we conducted the analysis both with and without the missing data for transparency.

Secondary outcomes included the rate of reduction in PHQ-9 score to less than 10 (reflecting moderate depression) at 12 and 24 weeks, and the absolute reduction in PHQ-9 score at 12 and 24 weeks.

Results

A total of 49 patients’ data were eligible for analysis. However, we excluded patients who were deceased at 12 weeks or 24 weeks from the primary analysis at each respective time point (see Methods section for rationale). Among the 47 patients who were ultimately included for primary analysis, the mean age was 63.4 years, 66% female, 78% White, 23.4% Hispanic, with a range of both solid cancers and hematological disorders at the time of referral to the SOC (Table 1).

Table 1. Sample demographics

Changes at 12 weeks

The mean initial PHQ-9 score was 17.3 (reflecting moderately severe depression) (Kroenke et al. Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001), with a mean reduction to 11.1 (moderate depression) at 12 weeks and 10.0 at 24 weeks (Table 2). Of the 47 patients included for analysis at the 12-week time point, 4 were missing PHQ-9 data and 15 showed a response in depressive symptoms, defined as a 50% reduction in PHQ-9 score. The depression response rate at 12 weeks was 31.9% including patients with missing data, or 34.9% excluding patients with missing data. The depression response rate of 34.9% at 12 weeks (excluding missing data) is comparable to the depression response rate of 35% in a clinical trial on collaborative care in oncology by Fann (Fann et al. Reference Fann, Fan and Unützer2009) but is lower compared with the response rates ranging from 45% to 53% in other trials (Fig. 2) (Strong et al. Reference Strong, Waters and Hibberd2008; Kroenke et al. Reference Kroenke, Theobald and Wu2010; Walker et al. Reference Walker, Hansen and Martin2014).

Table 2. Mean PHQ-9 and absolute change in PHQ-9 at 12 weeks and 24 weeks

Changes at 24 weeks

Among the 41 patients included for analysis at the 24-week time point, 19 were missing PHQ-9 data and 12 showed a response in depressive symptoms, defined as a 50% reduction in PHQ-9 score. The depression response rate at 24 weeks was 29.3% including missing data, or 54.5% excluding missing data. The depression response rate of 54.5% at 24 weeks (excluding missing data) is comparable to the response rates ranging from 42% to 62% in clinical trials (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Response rate benchmark comparison at 12 and 24 weeks. Comparison of the depression response rate (defined as 50% reduction in PHQ-9 or SCL-20) at 12 weeks (or 3 months) and 24 weeks (or 6 months) between the current study with data from the DFCI Merrimack Valley SOC and data from randomized control trials of collaborative care in oncology. The graph includes response rates for the current study excluding missing data.

For patients with data available, 20 out of 43 patients (46.5%) demonstrated a reduction of PHQ-9 score to < 10 (reflecting mild depression or less) at 12 weeks, and 13 out of 22 patients (59.1%) demonstrated a reduction of PHQ-9 score to < 10 at 24 weeks. The absolute reduction of the PHQ-9 score was − 5.9 at 12 weeks and − 7.5 at 24 weeks among patients with available data.

Discussion

The present study examined depression outcomes in a real-world collaborative care program implemented at an academic cancer center. Furthermore, we benchmarked the results against those of randomized clinical trials of collaborative care in oncology settings (Ell et al. Reference Ell, Xie and Quon2008; Strong et al. Reference Strong, Waters and Hibberd2008; Fann et al. Reference Fann, Fan and Unützer2009; Kroenke et al. Reference Kroenke, Theobald and Wu2010; Sharpe et al. Reference Sharpe, Walker and Holm Hansen2014; Walker et al. Reference Walker, Hansen and Martin2014). These results suggest that the SOC generates the intended outcomes and is likely effective. Using retrospective analysis of data gathered from the electronic medical record, among patients who had completed PHQ-9 measurement tools, the depression outcomes were comparable to those found in clinical trials.

Retrospective studies of real-world clinical models come with advantages and disadvantages. An advantage of the present study is that we evaluated a clinical system as it exists in practice, designed to meet the needs of patients. However, there was a lack of research infrastructure, such as research assistants to recruit participants, call with reminders, or ensure that outcome measures such as the PHQ-9 were completed. This reflects real-world care but also creates limitations from a research methodology and data quality standpoint, as it becomes more difficult to capture data consistently or completely.

As a result, there was substantial missing data: 4 out of 47 patients (8.5%) at 12 weeks, and 19 out of 41 patients (46.3%) at 24 weeks. The sheer volume of missing data, particularly at 24 weeks, made it challenging to calculate and interpret the observed depression response rates. With the most conservative interpretation, where all missing data were assumed to reflect non-response, the 12-week response rate was still comparable to that of the Fann et al. study (Fann et al. Reference Fann, Fan and Unützer2009), while the 24-week rate would fall well below benchmark values. With the most optimistic interpretation, where all missing data was assumed to reflect a response to depression (40.0% at 12-weeks and 75.6% at 24-weeks), the response rates would be comparable to those in clinical trials at 12-weeks, and greater than those in clinical trials at 24-weeks. In a more balanced scenario, where missing data was not systematically related to outcome and simply excluded, the response rates seen in this study appear comparable to those seen in multiple clinical trials.

There are several considerations that likely impacted these study response rates compared with clinical trials. First, the use of LOCF, which was applied for the 12-week and 24-week analyses, may have affected the observed response rates. In practice, the PHQ-9 used for each time point often did not fall exactly at the target window (i.e., 12 weeks and 24 weeks). For example, some PHQ-9 scores analyzed as the 12-week time point were completed much earlier, including one patient whose 12-week score was recorded seven days after the initial PHQ-9. Further, some PHQ-9 scores at the 24-week time point were filled out shortly after the 12-week time point. This likely contributed to the more modest response rate at 12 weeks, as some patients may not have had adequate time to receive and respond to treatment. Conversely, the 24-week timepoint may have better captured treatment effects, potentially explaining the stronger response rate at that time.

Second, it is important to consider the intervention offered by each of the clinical trials compared with the SOC model. Some clinical trials offered structured intensive behavioral therapies, including both the Strong and Walker studies, which offered 10 one-to-one manualized sessions over 3 or 4 months, respectively, often at the patient’s home (Strong et al. Reference Strong, Waters and Hibberd2008; Walker et al. Reference Walker, Hansen and Martin2014). In the SOC model, the type and frequency of behavioral interventions varied based on clinical assessment. The oncology social worker, as the care manager, was able to provide a range of behavioral interventions including supportive counseling, behavioral activation, mindfulness, motivational interviewing, and techniques drawn from cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). Complex patients requiring structured CBT, dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), or acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) could be referred to a specialized psychologist for that work. Thus, the interventions delivered as part of this clinical care model were more heterogeneous than those delivered in the RCTs that we benchmarked against. This model also does not specifically focus on identifying and treating depression; it employs collaborative care to address all supportive care needs.

Finally, a major difference between this study and the other RCTs is the exclusion criteria. Other RCTs (Strong et al. Reference Strong, Waters and Hibberd2008; Sharpe et al. Reference Sharpe, Walker and Holm Hansen2014; Walker et al. Reference Walker, Hansen and Martin2014) excluded patients who had continuous depression for > 2 years, those who were already seeing a mental health specialist (Fann et al. Reference Fann, Fan and Unützer2009; Sharpe et al. Reference Sharpe, Walker and Holm Hansen2014; Walker et al. Reference Walker, Hansen and Martin2014), those with known cerebral metastases (Sharpe et al. Reference Sharpe, Walker and Holm Hansen2014; Walker et al. Reference Walker, Hansen and Martin2014), or those with severe mental illness or suicidality (Ell et al. Reference Ell, Xie and Quon2008; Strong et al. Reference Strong, Waters and Hibberd2008; Fann et al. Reference Fann, Fan and Unützer2009; Kroenke et al. Reference Kroenke, Theobald and Wu2010). The justification supplied by Strong for these exclusions was that the goal of the collaborative care program was to supplement depression care rather than treat problems requiring specialist psychiatric care. This study, in contrast, was inclusive of patients across the psychiatric illness severity spectrum. Therefore, our depression response rate may be reflective of a psychiatrically sicker population, that is also somewhat heterogeneous with respect to severity, compared to those of other RCTs.

Clinically, this study suggests that a real-world collaborative care model in an oncology setting performs well among patients with available data, when benchmarked against RCTs of similar interventions (Ell et al. Reference Ell, Xie and Quon2008; Strong et al. Reference Strong, Waters and Hibberd2008; Fann et al. Reference Fann, Fan and Unützer2009; Kroenke et al. Reference Kroenke, Theobald and Wu2010; Sharpe et al. Reference Sharpe, Walker and Holm Hansen2014; Walker et al. Reference Walker, Hansen and Martin2014), even lacking resources and ideal research conditions, such as control groups, stricter administration of patient-reported outcomes, and other methodological advantages, as well as evaluating a population that included psychiatrically sicker patients. However, when substantial missing data were included and assumed to represent non-responders, as in the 24-week analysis, the observed depression response rate dropped markedly. This discrepancy highlights the need to examine the experiences and outcomes of patients who do not have ongoing PHQ-9 completion. Thus, future research efforts may focus on manual chart review of electronic medical records for patients who are missing PHQ-9 scores, as it may provide insights into their clinical outcomes and help guide future improvements to care. There are several hypotheses for patients missing PHQ-9 scores. Some patients may have completed active cancer treatment and transitioned much of their care outside of the cancer center setting. Some patients who experienced improvement in symptoms may have simply ceased to follow-up with the SOC team upon feeling better. There may also be patients who still require active cancer treatment or are still experiencing persistent or worsening depressive symptoms, but are not completing the PHQ-9 due to their illness, operational inefficiencies, or the burden of completing questionnaires. Data quality improvement efforts to increase assessment completion or the use of alternative patient-reported outcome measures would help elucidate the types of patients comprising this population.

A novel feature of the SOC model is the integration of palliative and behavioral health care with oncology care. Compared to prior RCTs in oncology, the addition of the palliative care service does not appear to worsen depression outcomes. Further research should explore whether the inclusion of palliative care enhances behavioral health outcomes and assess the model’s impact on other key domains such as pain, fatigue, and quality of life.

This study has several limitations. The timing and availability of PHQ-9 scores posed a significant challenge, as scores were often collected outside the targeted 12- and 24-week windows. This complicates comparison with existing RCTs and may have introduced variability in the observed treatment response (Ell et al. Reference Ell, Xie and Quon2008; Strong et al. Reference Strong, Waters and Hibberd2008; Fann et al. Reference Fann, Fan and Unützer2009; Kroenke et al. Reference Kroenke, Theobald and Wu2010; Sharpe et al. Reference Sharpe, Walker and Holm Hansen2014; Walker et al. Reference Walker, Hansen and Martin2014). In addition, the study is limited by its retrospective design and relatively small sample size, and was conducted at a single regional site within a single academic medical center, which may limit generalizability. Finally, the high proportion of missing outcome data, particularly at 24 weeks, limits confidence in point estimates and underscores the need for improved follow-up mechanisms in clinical implementation.

Despite its limitations, the present study has numerous strengths. First, it is an evaluation of a real-world collaborative care model in a cancer setting that is suggestive of effectiveness even under non-research conditions. Second, the observed response rates were comparable to those observed in RCTs of oncology populations. Finally, this study does not exclude patients based on chronic or severe psychiatric conditions and likely encompasses a psychiatrically sicker population compared with the populations studied in RCTs.

Overall, this study suggests that among patients seen at a cancer center for whom depression outcomes data are available, the collaborative care model performs well, with depression response rates comparable to those observed in RCTs of oncology populations. However, the high rates of missing data highlight the importance of further research and data quality improvement efforts to ensure that the impact of such models is fully understood, especially among patients who may be less engaged or harder to follow over time.

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge the Bruce Gilboard Philanthropic Fund for supporting the publication of this manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

W.F.P. serves as a consultant for Juxtapose. M.Y. serves as consultant to One Huddle and is a company shareholder. Authors C.C.W., A.K., K.L., and C.C. declare no competing interests.