Introduction

The consequences inflicted upon the world by wars, diseases, and natural disasters underscore the criticality of individual donations. Despite this urgency, numerous organizations reported a downward trend in donations in 2022 (e.g., Charities Aid Foundation, n.d.; Giving USA, n.d.). As a result, donations cannot keep up with the nonprofit sector’s financial demands (Peng et al., Reference Peng, Kim and Deat2019), and a pressing necessity exists to identify innovative fundraising strategies (Gugenishvili, Reference Gugenishvili2022b). One such strategy could involve using virtual reality (VR). In VR, individuals, henceforth referred to as users, employ various gadgets to navigate a virtual environment while remaining in their own physical space (Cowan et al., Reference Cowan, Ketron and Kostyk2023; Van Kerrebroeck et al., Reference Van Kerrebroeck, Brengman and Willems2017). Acknowledging its persuasive power, nonprofit organizations, including Charity Water, UNICEF, and Oxfam International, have started using VR storytelling to raise financial support in the battle against social issues encompassing poverty, hunger, and inequality (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Anggraini and Schlüter2020).

The advantage of VR is its ability to completely isolate users, immersing them within the scenario and creating a sense of being part of the story (Hou & Chen, Reference Hou and Chen2021). This technology could instill empathy for disadvantaged groups, including racial and ethnic minorities, refugees, and those with disabilities (Milk, Reference Milk2015; Shin, Reference Shin2018), and motivate donations. However, despite the scholarly interest, there is conflicting evidence of empathy and behavior in VR (Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Matson-Barkat, Pallamin and Jegou2019; Martingano et al., Reference Martingano, Konrath, Henritze and Brown2022). Thus, we do not know whether VR is more powerful than desktop computers in increasing empathy and charitable donations.

While certain previous studies corroborate the idea that users experience an increased presence when watching the content using VR as compared to desktop computers (e.g., Ma et al., Reference Ma, Huang and Yao2021), others argue that feeling present depends on individual characteristics and intentions (e.g., Kober & Neuper, Reference Kober and Neuper2013; Shin, Reference Shin2018). Moreover, even though Wirth et al. (Reference Wirth, Hartmann, Böcking, Vorderer, Klimmt, Schramm, Saari, Laarni, Ravaja and Gouveia2007) suggest spatial presence is the outcome of paying attention and spatial situational modeling, the research on these concepts is limited and inconclusive. For instance, Li et al. (Reference Li, Anguera, Javed, Khan, Wang and Gazzaley2020) found that VR increases attention allocation, while Barbosa et al. (Reference Barbosa, Pasion, Silvério, Coelho, Marques-Teixeira and Monteiro2019) concluded it does not. In addition, there is little understanding of how people react to VR (Cowan et al., Reference Cowan, Spielmann, Horn and Griffart2021) and of the persuasive advantage VR has in comparison to conventional media (Kristofferson et al., Reference Kristofferson, Daniels and Morales2022). For example, it is still uncertain whether the presence leads to positive social outcomes, such as empathy and donations (Kahn & Cargile, Reference Kahn and Cargile2021) as studies show inconsistent results (e.g., Sundar et al., Reference Sundar, Kang and Oprean2017; Tong et al., Reference Tong, Ulas, Jin, Gromala and Shaw2017). Given the current state of somewhat limited and inconclusive literature on this topic, our assertion remains speculative until a substantial body of scholarly evidence can provide robust support.

This study seeks to fill some gaps in the literature by comparing the presence and prosocial outcomes in a controlled experiment. One hundred participants were split into two groups, of which one group was asked to view the content using VR and the other group using a desktop computer. Our results showed that users feel more empathetic toward the protagonist in a story (in our case, a victim of war) when viewing the content in VR compared to a desktop computer. However, our study did not show that VR content motivates users to donate more effectively than content on a desktop computer. The paper is structured as follows. First, the theoretical background is elaborated, based on which we develop hypotheses. Second, we describe how the experiment, data collection, and data analysis were conducted. Finally, general discussion, contributions and limitations, and future research suggestions are provided.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

Interest in VR’s impact on donations and prosocial behavior rises as nonprofits increasingly use it to raise awareness of social issues. With wearable devices, VR obscures sensory input and locks the users out of the physical environment (Bogicevic et al., Reference Bogicevic, Seo, Kandampully, Liu and Rudd2019), consequently immersing them in a virtual world (Hou & Chen, Reference Hou and Chen2021). Immersion is deep engagement in the present moment. Achieving such a state requires three conditions; first, content must provide a near real-time connection between users’ actions and their sensations; second, visuals and audio in VR must be realistic; third, elements of the virtual environment should be responsive (Putra et al., Reference Putra, Lee and Kemper2023). The experimental counterpart of immersion is spatial presence (Wirth et al., Reference Wirth, Hartmann, Böcking, Vorderer, Klimmt, Schramm, Saari, Laarni, Ravaja and Gouveia2007), which refers to being present or “being there” in a technology-facilitated environment (Bogicevic et al., Reference Bogicevic, Seo, Kandampully, Liu and Rudd2019; Hsiao & Lin, n.d.; Sagnier et al., Reference Sagnier, Loup-Escande, Lourdeaux, Thouvenin and Valléry2020). Presence and immersion share similarities. However, they have a causal relationship where presence is the mental, sensory, and cognitive result of immersion, whereas immersion is a feature of technology (Cummings & Bailenson, Reference Cummings and Bailenson2016; Slater & Wilbur, Reference Slater and Wilbur1997). Thus, both of these terms describe a situation in which the boundaries between real and imagined environments are fuzzy (Shin, Reference Shin2018).

In VR, users are isolated from the outside world and perceive their environment solely through the headset as they move. Contrarily, visual and audio cues in books and films continuously assure individuals that they remain in actual reality, not the narrative (Slater & Sanchez-Vives, Reference Slater and Sanchez-Vives2016; Studt, Reference Studt2021). A study of nursing students by Ma et al. (Reference Ma, Huang and Yao2021), for instance, showed that playing in VR enhances presence perceptions compared to other technology. Immersion and spatial presence in VR also depend on individual characteristics and intentions, not just the technology itself. Kober and Neuper (Reference Kober and Neuper2013) found that presence correlates with mental imagination and immersive tendencies. Shin (Reference Shin2018) also concluded that VR immersion depends on users’ intentions of immersing in it, rather than on technological features. Still VR, unlike other mediums, can meet all the conditions for immersion and simultaneously address several sensory channels (Wirth et al., Reference Wirth, Hartmann, Böcking, Vorderer, Klimmt, Schramm, Saari, Laarni, Ravaja and Gouveia2007). Therefore, we hypothesize that VR produces a more profound spatial presence than other mediums, like a desktop computer in this study.

H1

Participants exposed to content via VR are more likely to perceive the spatial presence within the virtual realm than the ones exposed to the same content via desktop computer.

If VR facilitates spatial presence, understanding its potential antecedents and consequences is crucial. This knowledge will aid researchers and marketers in effectively boosting spatial presence as needed. In their framework of spatial presence, Wirth et al. (2007b) proposed attention allocation as a pivotal facilitator of presence. Attention allocation involves dedicating cognitive resources to media, either voluntarily when users find the media engaging, or involuntarily when it aligns with their needs or interests. Attention allocation can be brief or prolonged, influenced by factors within the media. Which factors play a role in the VR context is yet to be determined, but the underlying premise is that attention allocation is proportional to the number of sensory channels the technology can activate, which is high in VR (Wirth et al., Reference Wirth, Hartmann, Böcking, Vorderer, Klimmt, Schramm, Saari, Laarni, Ravaja and Gouveia2007). To test the phenomenon in empirical settings, Barbosa et al. (Reference Barbosa, Pasion, Silvério, Coelho, Marques-Teixeira and Monteiro2019) administered pleasant, unpleasant, and neutral visual-emotional stimuli to 31 participants via a computer screen as opposed to VR. The findings revealed that the computer screen was as successful in grabbing attention toward stimuli as VR. This influence remained consistent across emotional contexts. Contrarily, Li et al. (Reference Li, Anguera, Javed, Khan, Wang and Gazzaley2020) concluded that VR might be more efficient in claiming attention than 2D screens, such as desktops, laptops, and tablets. When attention allocation persists for an extended duration, users start constructing a spatial situation model. This model, or visualization of the space within the virtual world (Coxon et al., Reference Coxon, Kelly and Page2016), serves as the second crucial component in the formation of spatial presence. Even though the spatial situation model is a crucial part of evaluating media efficacy (Klippel et al., Reference Klippel, Zhao, Oprean, Wallgrün and Chang2019), not many studies in the VR context have been conducted on it. Thus, our H3 mainly relies on the idea that attention allocation and spatial situation models positively correlate with each other.

H2

Participants exposed to content via VR will exhibit higher attention allocation to the virtual realm than the ones exposed to the same content via desktop computer.

H3

Participants exposed to content via VR are more successful in forming the spatial situation model of the virtual realm than the ones exposed to the same content via desktop computer.

Considering the heightened presence in VR compared to desktop use, the application of the Construal Level Theory (CLT) of the psychological distance (Trope & Liberman, Reference Trope and Liberman2010) supports the idea of increased empathy. Empathy represents an emotion triggered by and consistent with the well-being of a perceived underdog (Batson, Reference Batson2011; Gugenishvili, Reference Gugenishvili2022b). The literature distinguishes between dispositional and situational empathy, where dispositional empathy is the individual characteristic, and situational empathy is a situational condition (Muller et al., Reference Muller, Van Kessel and Janssen2017). Additionally, empathy is categorized as emotional and cognitive, with cognitive involving perspective-taking without necessarily sharing emotions, and emotional involving feeling for others (Ventura, Reference Ventura2023). This study specifically examines situational and emotional empathy.

Drawing upon the fundamental tenets of CLT, we assert that VR has the potential to diminish the perceived psychological distance towards the object or situation that elicits an emotional response. In particular, VR should reduce perceived distance, and cause the object or situation to be mentally construed in a less abstract, more concrete, and contextualized manner (Wiesenfeld et al., Reference Wiesenfeld, Reyt, Brockner and Trope2017). When this occurs it diminishes the mental separation between oneself and others, consequently allowing individuals to take others’ perspectives (Behm-Morawitz et al., Reference Behm-Morawitz, Pennell and Speno2016). In such conditions, and based on previous studies, we believe, that feeling for others increases. For instance, Penn et al. (Reference Penn, Ivory and Judge2010) and Formosa et al. (Reference Formosa, Morrison, Hill and Stone2018) found VR to be successful in increasing empathetic responses toward individuals with schizophrenia. Similar findings were reached by Sundar et al., (Reference Sundar, Kang and Oprean2017), and Schutte and Stilinović (Reference Schutte and Stilinović2017), who concluded that experiencing the content in VR as opposed to other media leads to greater empathy.

While the above-mentioned studies suggest VR has the potential to enhance emotional empathy, other research has yielded conflicting results. These studies report that beneficial outcomes brought by VR exposure do not outweigh more conventional and affordable interventions, including having participants role-play in the actual world (Hargrove et al., Reference Hargrove, Sommer and Jones2020) or being asked to picture themselves in someone else’s shoes (Jones & Sommer, Reference Jones and Sommer2018). Oh et al. (Reference Oh, Bailenson, Weisz and Zaki2016) and Tong et al. (Reference Tong, Ulas, Jin, Gromala and Shaw2017) demonstrated that VR was unsuccessful in enhancing empathetic concerns toward the elderly or people with chronic pain. A meta-analysis of seven articles by Ventura et al. (Reference Ventura, Badenes-Ribera, Herrero, Cebolla, Galiana and Baños2020) shows that VR exposure leads to increased perspective-taking but not empathy. Martingano et al. (Reference Martingano, Hererra and Konrath2021) and Martingano et al., (Reference Martingano, Konrath, Henritze and Brown2022), further suggest that VR can arouse emotional empathy (feeling for others), but not cognitive empathy (understanding feelings without responding emotionally). Additionally, after 10 days, any gains in empathetic abilities were mostly lost. Furthermore, Ventura and Martingano (Reference Ventura, Martingano and Ventura2023) suggest that storytelling encourages emotional empathy, and embodiment and perspective-taking lead to cognitive empathy. Subsequently, studies looking at VR and empathy interaction are inconclusive. Nevertheless, based on CLT of psychological distance, we hypothesize:

H4

Participants exposed to content via VR will exhibit higher empathy towards victims than the ones exposed to the same content via desktop computer.

Regarding the actual behavior as a result of being exposed to VR storytelling, there exists robust theoretical backing that establishes a connection between empathy and prosocial behavior, such as helping, sharing, and cooperating (e.g., Davidov et al., Reference Davidov, Vaish, Knafo-Noam and Hastings2016; Decety & Jackson, Reference Decety and Jackson2004). This holds for both emotional and cognitive empathies as well (Decety & Svetlova, Reference Decety and Svetlova2012). However, empirical research in this domain remains inconclusive. Some scholars argue that individual differences in empathy translate into a variation in donations (e.g., Sze et al., Reference Sze, Gyurak, Goodkind and Levenson2012; Verhaert & Van den Poel, Reference Verhaert and Van den Poel2011). Others point out that the connection between empathy and charitable donations depends on various factors, including guilt and gender (e.g., Mesch et al., Reference Mesch, Brown, Moore and Hayat2011; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Strayer and Denham2014). In the field of VR, several real-world examples show promising results. For instance, charity initiatives such as Charity Water’s The Source and UNICEF’s Clouds over Sidra have both generated substantial donations (Swant, Reference Swant2016). However, research-based perspectives are scarce and often yield inconclusive results. The topic lacks thorough scholarly examination, and positive industry outcomes may be influenced by factors like self-selection bias, the absence of a control group, or the placebo effect (Martingano et al., Reference Martingano, Konrath, Henritze and Brown2022). For instance, some studies suggest that some VR content can alter behavioral intentions (e.g., Alberghini, Reference Alberghini2020; Yoo & Drumwright, Reference Yoo and Drumwright2018) or hypothetical behaviors (e.g., Kandaurova & Lee, Reference Kandaurova and Lee2019). Moreover, Nelson et al. (Reference Nelson, Anggraini and Schlüter2020) discovered that, in contrast to a written appeal for donations, VR content about the significance of coral reef preservation generated higher donations to a local charity. Similarly, when comparing VR and 360-degree 2D video, Kristofferson et al. (Reference Kristofferson, Daniels and Morales2022) found that VR can reap increased donations. Similarly, in their quasi-experiment, Radu et al. (Reference Radu, Dede, Seyam, Feng and Chung2021) concluded that VR exposure enhanced empathy and charitable behavior to help children experiencing issues in early literacy. Nevertheless, this effect was not universally applicable, as individuals with teaching backgrounds or lower initial levels of empathy were less susceptible to the influence of the VR content. Furthermore, when comparing VR to low-tech solutions, Gürerk and Kasulke (Reference Gürerk and Kasulke2022) VR proved more effective than written materials in boosting donations. However, the effectiveness of VR in this regard did not surpass that of an ordinary computer screen. In a more recent study, Martingano et al. (Reference Martingano, Konrath, Henritze and Brown2022) did not find any influence of VR on donations. Even so, considering the CLT of psychological distance, we believe the power of VR, as opposed to desktop computers, is stronger in increasing empathy and prosocial behavior, in this case, donation. Thus, we hypothesize:

H5

Participants exposed to content via VR will exhibit higher donation behavior towards victims than the ones exposed to the same content via desktop computer.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Procedure

The study took place at a university in Southwest Finland in 2022. The sample primarily included students and employees. of 100 individuals participated in the study. The sample size was determined based on practical considerations, resource constraints, and the available participant pool. Additionally, to detect a small-to-medium effect size of 0.33 with an alpha of 0.05, a minimum sample size of 89 is necessary to achieve a power of 0.8. The estimated effect size is consistent with previous research findings (e.g., Martingano et al., Reference Martingano, Hererra and Konrath2021, Reference Martingano, Konrath, Henritze and Brown2022).

The established protocol was followed, giving participants standardized instructions to maintain the study’s confidentiality. The participants were randomly assigned to one of the two experimental groups. For group 1, VR glasses (Oculus Quest 2) were calibrated after instructions. The experimental manipulation involved watching the documentary “The Displaced” in either VR or 2D (27″ Lenovo Desktop PC screen). The documentary narrated the real experiences of displaced children from South Sudan, Ukraine, and Lebanon due to war in a way that grounds users in the specific situation of these children’s lives. After viewing, participants filled out a SurveyMonkey questionnaire. Study objectives were disclosed at the end, allowing participants to withdraw.

Measures and Variables’ Operationalization

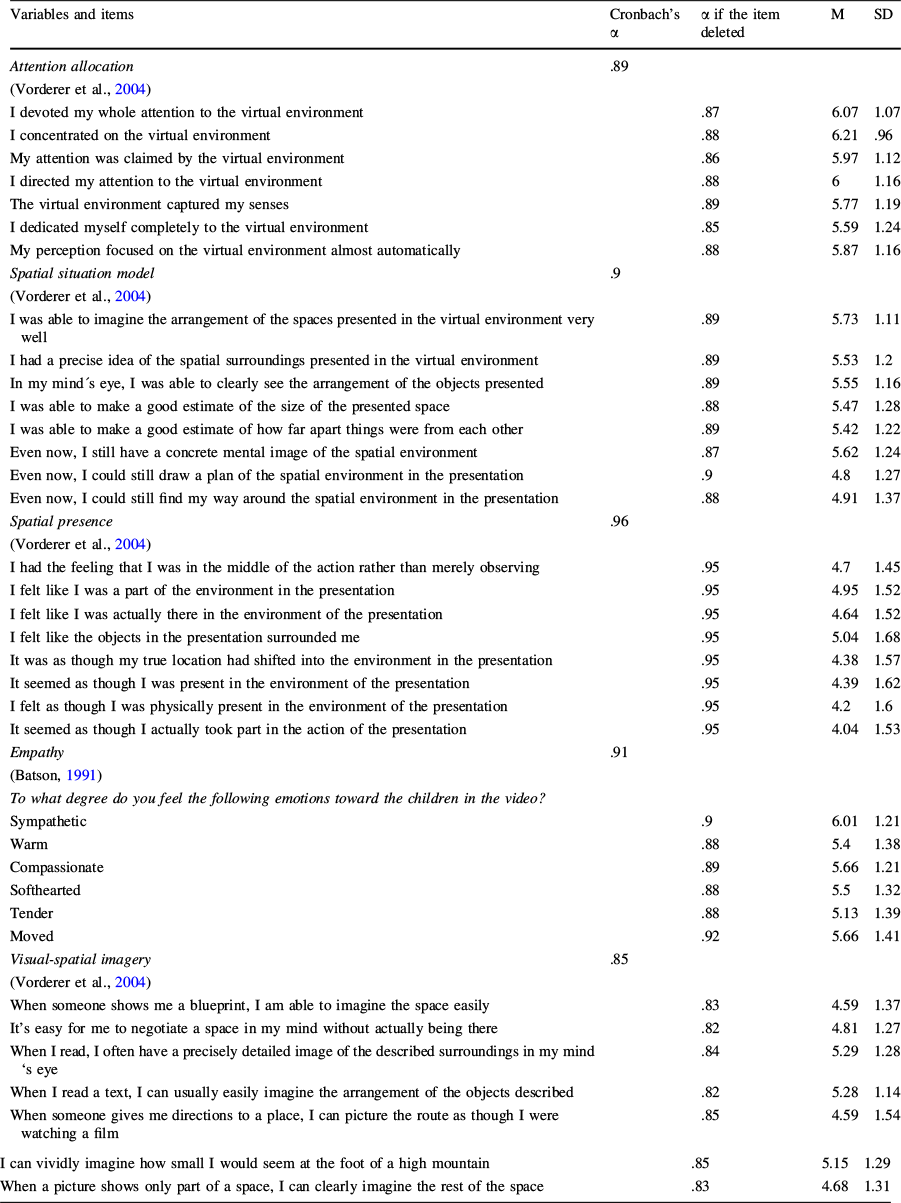

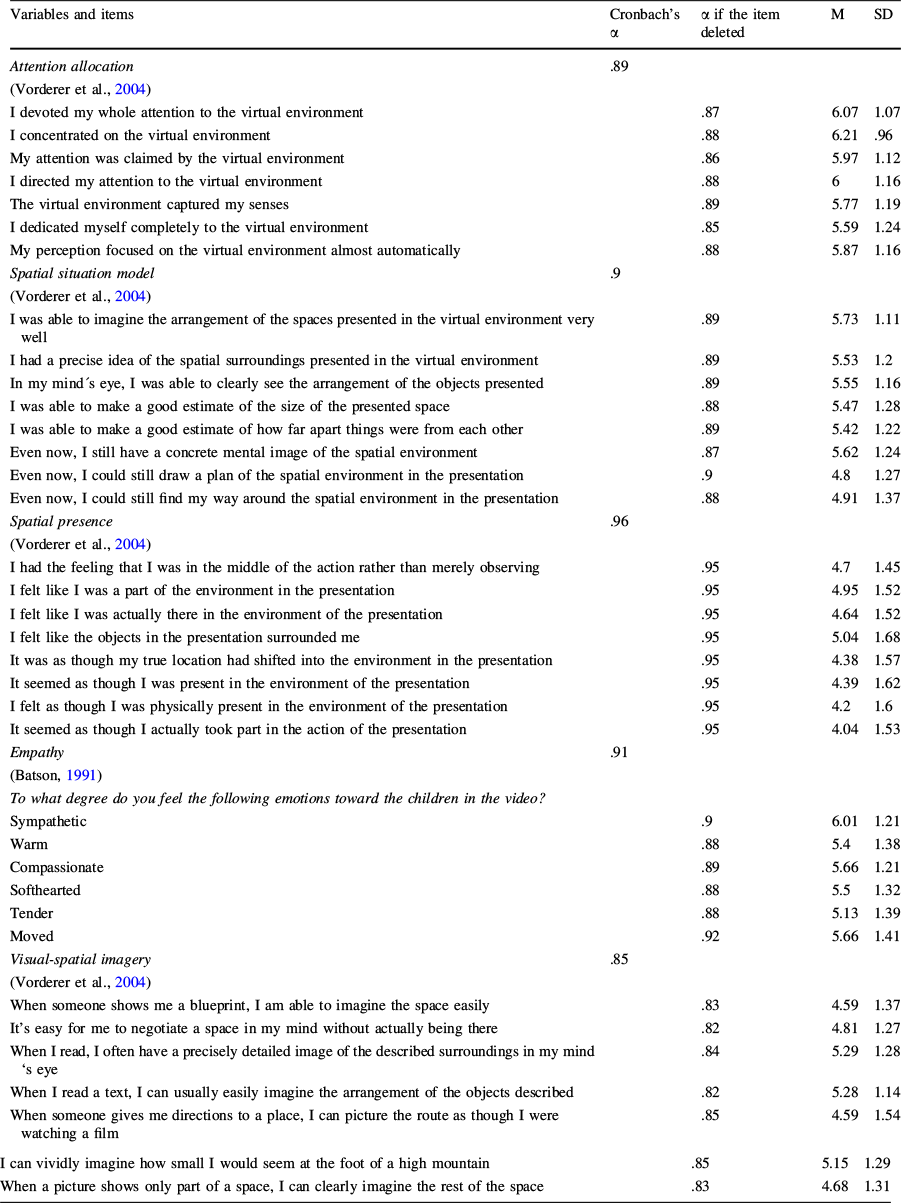

Adapting from existing literature, measurement item language was adjusted for relevance to this study’s context: spatial presence (Vorderer et al., Reference Vorderer, Wirth, Gouveia, Biocca, Saari, Jäncke, Böcking, Schramm, Gysbers and Hartmann2004), attention allocation, spatial situation model, and empathy (Batson, Reference Batson1991). We gathered data on visual-spatial imagery, the ability to process visual cues and create mental representations of space. Strong spatial imagery correlates with better manipulation of objects and shapes (Vorderer et al., Reference Vorderer, Wirth, Gouveia, Biocca, Saari, Jäncke, Böcking, Schramm, Gysbers and Hartmann2004). This covariate was considered as a potential factor that might influence the participants’ spatial situation model-building, spatial presence, and consequently empathy and donation behavior. Items of the variables are listed in Table 1. A 7-point Likert scale assessed all statements, and composite scores were obtained by averaging the values of multi-item constructs. Participants were informed that five randomly selected individuals could win a voucher. They were then asked to choose between keeping the entire amount, donating a portion, or donating the full sum to a charity of their choice:

Table 1 Items Measuring Key Constructs

Variables and items |

Cronbach's α |

α if the item deleted |

M |

SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Attention allocation (Vorderer et al., Reference Vorderer, Wirth, Gouveia, Biocca, Saari, Jäncke, Böcking, Schramm, Gysbers and Hartmann2004) |

.89 |

|||

I devoted my whole attention to the virtual environment |

.87 |

6.07 |

1.07 |

|

I concentrated on the virtual environment |

.88 |

6.21 |

.96 |

|

My attention was claimed by the virtual environment |

.86 |

5.97 |

1.12 |

|

I directed my attention to the virtual environment |

.88 |

6 |

1.16 |

|

The virtual environment captured my senses |

.89 |

5.77 |

1.19 |

|

I dedicated myself completely to the virtual environment |

.85 |

5.59 |

1.24 |

|

My perception focused on the virtual environment almost automatically |

.88 |

5.87 |

1.16 |

|

Spatial situation model (Vorderer et al., Reference Vorderer, Wirth, Gouveia, Biocca, Saari, Jäncke, Böcking, Schramm, Gysbers and Hartmann2004) |

.9 |

|||

I was able to imagine the arrangement of the spaces presented in the virtual environment very well |

.89 |

5.73 |

1.11 |

|

I had a precise idea of the spatial surroundings presented in the virtual environment |

.89 |

5.53 |

1.2 |

|

In my mind´s eye, I was able to clearly see the arrangement of the objects presented |

.89 |

5.55 |

1.16 |

|

I was able to make a good estimate of the size of the presented space |

.88 |

5.47 |

1.28 |

|

I was able to make a good estimate of how far apart things were from each other |

.89 |

5.42 |

1.22 |

|

Even now, I still have a concrete mental image of the spatial environment |

.87 |

5.62 |

1.24 |

|

Even now, I could still draw a plan of the spatial environment in the presentation |

.9 |

4.8 |

1.27 |

|

Even now, I could still find my way around the spatial environment in the presentation |

.88 |

4.91 |

1.37 |

|

Spatial presence (Vorderer et al., Reference Vorderer, Wirth, Gouveia, Biocca, Saari, Jäncke, Böcking, Schramm, Gysbers and Hartmann2004) |

.96 |

|||

I had the feeling that I was in the middle of the action rather than merely observing |

.95 |

4.7 |

1.45 |

|

I felt like I was a part of the environment in the presentation |

.95 |

4.95 |

1.52 |

|

I felt like I was actually there in the environment of the presentation |

.95 |

4.64 |

1.52 |

|

I felt like the objects in the presentation surrounded me |

.95 |

5.04 |

1.68 |

|

It was as though my true location had shifted into the environment in the presentation |

.95 |

4.38 |

1.57 |

|

It seemed as though I was present in the environment of the presentation |

.95 |

4.39 |

1.62 |

|

I felt as though I was physically present in the environment of the presentation |

.95 |

4.2 |

1.6 |

|

It seemed as though I actually took part in the action of the presentation |

.95 |

4.04 |

1.53 |

|

Empathy (Batson, Reference Batson1991) |

.91 |

|||

To what degree do you feel the following emotions toward the children in the video? |

||||

Sympathetic |

.9 |

6.01 |

1.21 |

|

Warm |

.88 |

5.4 |

1.38 |

|

Compassionate |

.89 |

5.66 |

1.21 |

|

Softhearted |

.88 |

5.5 |

1.32 |

|

Tender |

.88 |

5.13 |

1.39 |

|

Moved |

.92 |

5.66 |

1.41 |

|

Visual-spatial imagery (Vorderer et al., Reference Vorderer, Wirth, Gouveia, Biocca, Saari, Jäncke, Böcking, Schramm, Gysbers and Hartmann2004) |

.85 |

|||

When someone shows me a blueprint, I am able to imagine the space easily |

.83 |

4.59 |

1.37 |

|

It’s easy for me to negotiate a space in my mind without actually being there |

.82 |

4.81 |

1.27 |

|

When I read, I often have a precisely detailed image of the described surroundings in my mind ‘s eye |

.84 |

5.29 |

1.28 |

|

When I read a text, I can usually easily imagine the arrangement of the objects described |

.82 |

5.28 |

1.14 |

|

When someone gives me directions to a place, I can picture the route as though I were watching a film |

.85 |

4.59 |

1.54 |

|

I can vividly imagine how small I would seem at the foot of a high mountain |

.85 |

5.15 |

1.29 |

|

When a picture shows only part of a space, I can clearly imagine the rest of the space |

.83 |

4.68 |

1.31 |

You are now done with the first part of this study. Thank you for your participation!

As a ‘Thank You’ we will give a bonus voucher of €50 to five randomly chosen participants. Each participant regardless of their answers has an equal chance of winning the bonus.

You can keep the voucher for yourself or donate all or part of it to one of our partner child protection charitable organizations or an organization of your own choice. If you were to win, would you like to donate?

Please specify your preferences regarding the amount and/ or charitable organization below.

This method was adopted from Gugenishvili (Reference Gugenishvili2022a) and Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Rodas and Torelli2020). Finally, participants were asked to share their thoughts and emotions during the video through an open-ended question (“Tell us about your feelings while watching the video”).

Results

Data Screening and Assumptions Testing

Assumptions testing began by evaluating the study design: (a) five continuous dependent variables were used (empathy, donation behavior, attention allocation, spatial situation model, and spatial presence); (b) the independent variable used was categorical (group 1: VR; group 2: 2D); and (c) observations were independent of each other. The remaining assumptions were tested using IBM SPSS Statistics 27. Seven outliers had been discovered, as determined by looking at a boxplot for values more than 1.5 box lengths from the box’ edge. Close inspection of the respondents and their responses identified no errors related to data entry or measurement. Therefore, we deemed these points as natural variations and they were thus kept for further analysis. Some of the residuals were not normally distributed according to Shapiro–Wilk’s test (empathy p < 0.001; attention allocation p < 0.001). Due to the roughly equal sample sizes and the independent-sample t-test’s robustness to departures from the normality (see Glass et al., Reference Glass, Peckham and Sanders1972; Mardia, Reference Mardia1971), we proceeded with the analysis. Levene’s test for equality of variances revealed that the variances for empathy for both groups were homogeneous (95% CI [0.001, 0.91], t (98) = 1.9, p = 0.55), and correspondingly for attention allocation (95% CI [0.25, 0.91], t (98) = 3.49, p = 0.08), spatial situation model (95% CI [0.16, 0.83], t (98) = 2.57, p = 0.92), and spatial presence (95% CI [0.76, 1.72], t (98) = 5.14, p = 0.5). The assumption was however violated for donation behavior (95% CI [−0.1, 0.6], t (98) = 1.43, p = 0.02), which is taken into consideration when reporting the significance of the group differences on this variable.

The results of the Kruskal–Wallis and Chi-square tests revealed no differences between the two experimental groups in terms of age (p = 0.433) and gender (p = 0.841). Independent-sample t-test results reveal no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of their visual-spatial imagery abilities (MVR = 5 0.06, MCOMPUTER = 4.8, MD = 0.3, 95% CI [−0.1, 0.66], t (102) = 0.48, p = 0.14, d = 0.98).

Reliability of Scales

Cronbach’s alphas ranged from 0.86 to 0.96 for all scales, revealing good validity for all constructs. Table 1 provides detailed information about the measuring items.

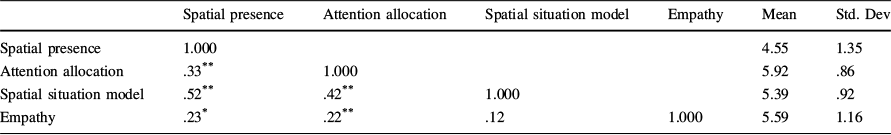

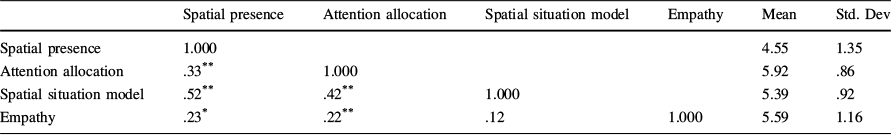

Descriptive Statistics

The sample comprised 100 individuals: 54% of whom were female, and the mean age of the respondents was 26 (min. = 20; max. = 54; mode = 22; std. dev. = 6.546). Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics.

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics of Measured Constructs

Spatial presence |

Attention allocation |

Spatial situation model |

Empathy |

Mean |

Std. Dev |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Spatial presence |

1.000 |

4.55 |

1.35 |

|||

Attention allocation |

.33** |

1.000 |

5.92 |

.86 |

||

Spatial situation model |

.52** |

.42** |

1.000 |

5.39 |

.92 |

|

Empathy |

.23* |

.22** |

.12 |

1.000 |

5.59 |

1.16 |

The coefficient is significant at the 2-tailed .01 level, as denoted by the **

The coefficient is significant at the 2-tailed .05 level, as denoted by the *

Hypotheses Testing

Significant differences between the two experimental groups were observed in terms of spatial presence scores, with participants who watched the content in VR scoring higher than the ones who watched it on a computer, MVR = 5.18, MCOMPUTER = 3.94, MD = 1 0.24, 95% CI [0.76, 1.72], t (98) = 5.14, p < 0.001, d = 1.2. Thus, we accept the alternative H1.

The group differences were also statistically significant in terms of attention allocation and spatial situation model, p = 0.012, and d = 0.91, respectively. Thus, we accept the H2 and H3.

Empathy differed between the two experimental groups, with participants who watched the content in VR scoring higher than the ones who watched it on a desktop computer, MVR = 5.78, MCOMPUTER = 5.32, MD = 0.46, 95% CI [0.00, 0.91], t (98) = 1.99, p = 0.049, d = 1.14. Based on this we accept the alternative H4. Figure 1 below illustrates the findings of the first four hypotheses of this study.

Fig. 1 Visual Illustration of the results

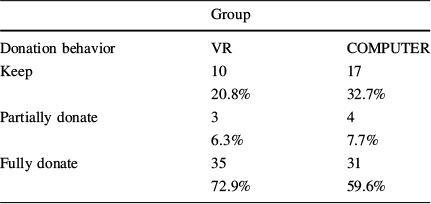

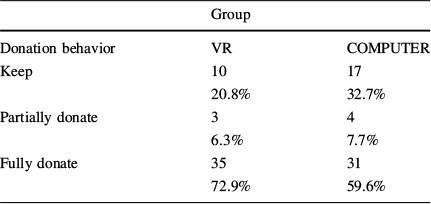

Finally, the difference in terms of donation behavior between the two experimental groups was assessed using the Chi-square test of homogeneity. Table 3 presents donation behaviors.

Table 3 Crosstabulation of Groups and Donation Behavior

Group |

||

|---|---|---|

Donation behavior |

VR |

COMPUTER |

Keep |

10 |

17 |

20.8% |

32.7% |

|

Partially donate |

3 |

4 |

6.3% |

7.7% |

|

Fully donate |

35 |

31 |

72.9% |

59.6% |

There was no statistically significant difference in the multinomial probability distributions of the two groups (p = 0.36). As a result, alternative H5 cannot be accepted.

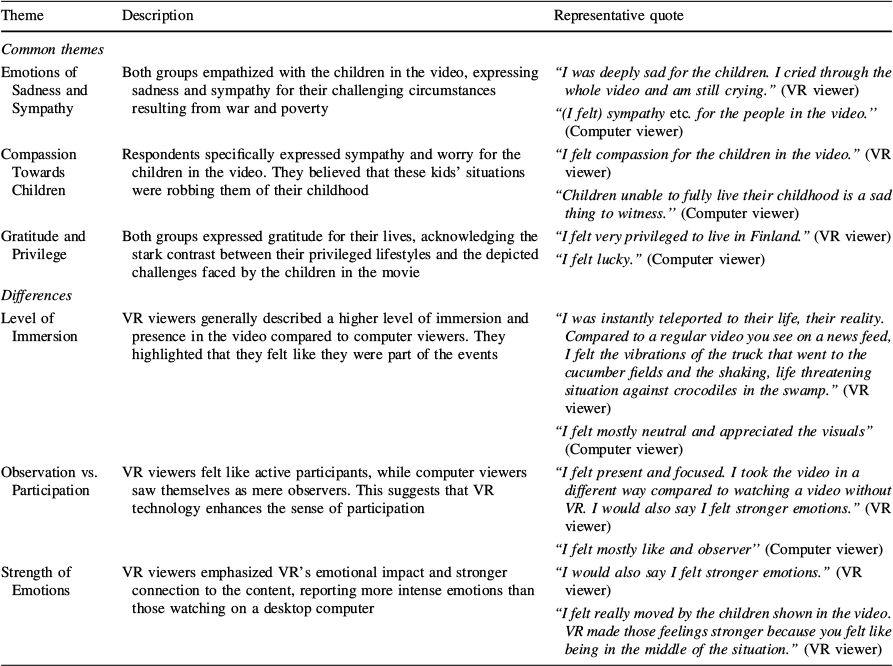

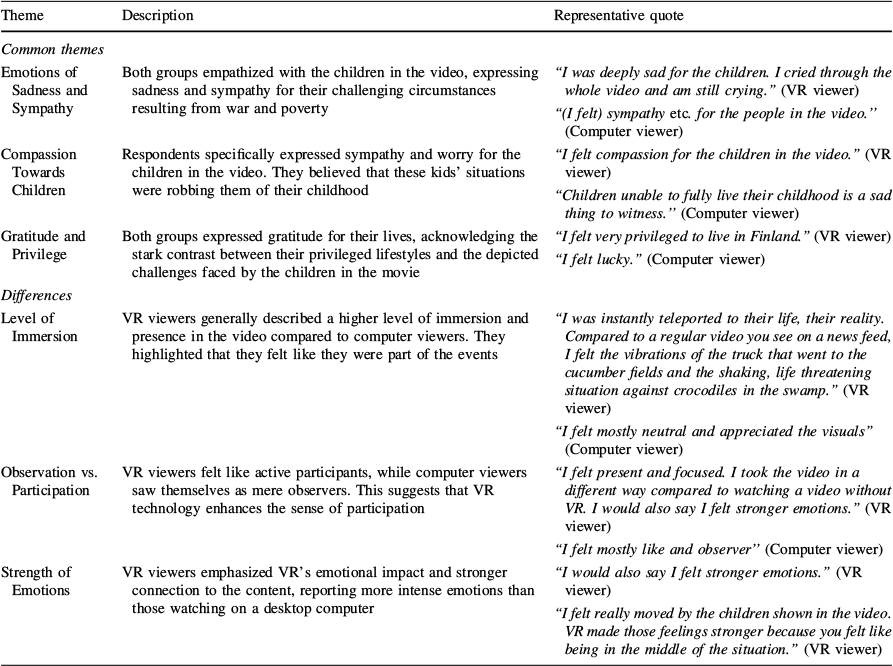

Qualitative Content Analysis

NVivo, a qualitative data analysis software, was used to code open-ended question responses. Seventy-one respondents answered. The length of these answers ranged from one to 110 words. We aimed to identify commonalities and differences between the two groups. This data-driven technique was used due to the lack of applicable taxonomies or frameworks for use with this dataset (see Jin et al., Reference Jin, Liu, Yarosh, Han and Qian2022). Results show that both groups had similar feelings of sadness, pity, thankfulness, and concern for the children in the video. They differed in terms of degree of immersion, feeling of participation, and perceptions of the effectiveness of VR technology. Group 1 (VR) indicates a more emotionally impactful and engaging experience. Table 4 summarizes the qualitative content analysis findings.

Table 4 Qualitative Content Analysis Findings

Theme |

Description |

Representative quote |

|---|---|---|

Common themes |

||

Emotions of Sadness and Sympathy |

Both groups empathized with the children in the video, expressing sadness and sympathy for their challenging circumstances resulting from war and poverty |

“I was deeply sad for the children. I cried through the whole video and am still crying.” (VR viewer) “(I felt) sympathy etc. for the people in the video.” (Computer viewer) |

Compassion Towards Children |

Respondents specifically expressed sympathy and worry for the children in the video. They believed that these kids' situations were robbing them of their childhood |

“I felt compassion for the children in the video.” (VR viewer) “Children unable to fully live their childhood is a sad thing to witness.” (Computer viewer) |

Gratitude and Privilege |

Both groups expressed gratitude for their lives, acknowledging the stark contrast between their privileged lifestyles and the depicted challenges faced by the children in the movie |

“I felt very privileged to live in Finland.” (VR viewer) “I felt lucky.” (Computer viewer) |

Differences |

||

Level of Immersion |

VR viewers generally described a higher level of immersion and presence in the video compared to computer viewers. They highlighted that they felt like they were part of the events |

“I was instantly teleported to their life, their reality. Compared to a regular video you see on a news feed, I felt the vibrations of the truck that went to the cucumber fields and the shaking, life threatening situation against crocodiles in the swamp.” (VR viewer) “I felt mostly neutral and appreciated the visuals” (Computer viewer) |

Observation vs. Participation |

VR viewers felt like active participants, while computer viewers saw themselves as mere observers. This suggests that VR technology enhances the sense of participation |

“I felt present and focused. I took the video in a different way compared to watching a video without VR. I would also say I felt stronger emotions.” (VR viewer) “I felt mostly like and observer” (Computer viewer) |

Strength of Emotions |

VR viewers emphasized VR’s emotional impact and stronger connection to the content, reporting more intense emotions than those watching on a desktop computer |

“I would also say I felt stronger emotions.” (VR viewer) “I felt really moved by the children shown in the video. VR made those feelings stronger because you felt like being in the middle of the situation.” (VR viewer) |

Discussion

Does VR storytelling prove more effective in eliciting empathy and motivating donations compared to desktop computers? Previous literature is inconclusive (Kober & Neuper, Reference Kober and Neuper2013; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Huang and Yao2021; Shin, Reference Shin2018). As VR becomes increasingly popular for raising awareness and collecting donations, understanding its potential impact on fostering prosocial behavior is crucial. In this study, we compared the effects of VR and desktop computer stimuli, hypothesizing that VR would result in higher spatial presence, attention allocation, spatial situation model, empathy, and donations. The between-subject experiment ensured groups were matched in virtual spatial imagery abilities.

Our research highlights a distinct phenomenological difference between VR and desktop computer experiences. The VR group reported higher spatial presence, attention allocation, and spatial situation model-building. It contributes to a further understanding of how users experience VR content and how it influences their virtual environment presence perceptions. Quantitative findings have been further reinforced by the comments we received through the open-ended question. In their comments, several respondents suggested they felt “instantly teleported” and “fully surrounded by the environments.” These results align with some previous studies (e.g., Li et al., Reference Li, Anguera, Javed, Khan, Wang and Gazzaley2020; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Huang and Yao2021) but contradict others (e.g., Barbosa et al., Reference Barbosa, Pasion, Silvério, Coelho, Marques-Teixeira and Monteiro2019). This variation may be due to differences in sample and experimental settings. Barbosa et al. (Reference Barbosa, Pasion, Silvério, Coelho, Marques-Teixeira and Monteiro2019) determined that both VR and desktop computers were equally successful in capturing attention; however, their study, unlike ours, only encompassed male respondents. Males and females differ significantly in attention to cues. Females show heightened responsiveness in visual-spatial attention tasks, leading to increased attention toward task completion (Feng et al., Reference Feng, Zheng, Zhang, Song, Luo, Li and Talhelm2011).

Our findings show that in VR, users feel more empathetic towards the narrative's protagonist than when using a desktop computer. In their open-ended question responses, VR viewers used phrases, such as “really moved”, “emotionally overwhelmed”, and “heartbroken” when describing their emotions. These results parallel the findings of several studies (e.g., Martingano et al., Reference Martingano, Hererra and Konrath2021, Reference Martingano, Konrath, Henritze and Brown2022), thus further supporting the application of the CLT of psychological distance to the domain of VR. VR likely reduces distance, ultimately triggering an emotional response to the context. An alternative explanation may be that VR, as suggested by this study, more effectively captures attention than desktop computers. Given the established correlation between attention allocation and empathy (r = 0.218, p < 0.01), one could argue that by engaging more attentively with the content, individuals are more inclined to comprehend and empathize with the experiences of victims, in contrast to inattentively and superficially watching the video. Still, some researchers, such as Oh et al. (Reference Oh, Bailenson, Weisz and Zaki2016) and Tong et al. (Reference Tong, Ulas, Jin, Gromala and Shaw2017), did not find that VR experiences increased empathetic concerns toward the elderly or people with chronic pain. According to these authors, the short length of the intervention may have caused this lack of an effect.

Even though participants empathized more when watching the content in VR versus desktop computers, no statistically significant difference in donations was observed between the two groups. Thus, our findings, similar to Radu et al. (Reference Radu, Dede, Seyam, Feng and Chung2021), Gürerk and Kasulke (Reference Gürerk and Kasulke2022), and Martingano et al. (Reference Martingano, Konrath, Henritze and Brown2022), do not support the idea that VR would be more useful than desktop computers to motivate individuals to make actual donations in experimental settings. This finding challenges the prevailing industry perception that VR is inherently effective in generating monetary donations. It is plausible that the industry exemplars suffer from the self-selection bias.Footnote 1 For example, the well-known case of Charity Water involved screening the movie “The Source” to 400 individuals during a charitable event, leading to an accumulation of $4.4 million in donations in a single night (Prois, Reference Prois2013). Similarly, in cases where charitable organizations use VR displays in malls or offices, individuals engaging with the VR content are more likely to donate than those who do not. Finally, insignificant results in donations could be caused by a small sample size; our sample included only 100 respondents and Radu et al.'s (Reference Radu, Dede, Seyam, Feng and Chung2021) the sample included 27. Our findings contradict the ones made by Kristofferson et al. (Reference Kristofferson, Daniels and Morales2022), those who found that VR viewers were more likely to donate than computer viewers. Differences between the sample characteristics (Finnish vs. Canadian) or experimental setup could be the reason for this discrepancy. For example, Nordic countries, including Finland, are characterized by a strong public sector, active labor market policies, high taxes, and substantial costs for social welfare (Lyttkens et al., Reference Lyttkens, Christiansen, Hâkkinen, Kaarboe, Sutton and Welander2016). Additionally, these countries exhibit lower inequalities (Huijts & Eikemo, Reference Huijts and Eikemo2009), with a prevailing belief that the government bears the responsibility for welfare programs. Consequently, individuals in Nordic countries might be less inclined to donate compared to their counterparts in the United States, who may hold different beliefs regarding civic responsibility. Furthermore, in Kristofferson et al.'s (Reference Kristofferson, Daniels and Morales2022) study, each participant was asked to contribute $5 as a donation. In contrast, our study presented the participants with the possibility of receiving a €50 prize and inquired about their willingness to donate. The substantial disparity in the amounts involved could have impacted the perceived stakes for the participants—€50 offers greater utility than $5, potentially influencing their decision-making. The difference in the monetary value might have played a significant role, considering the varied implications and purchasing power associated with these amounts.

Conclusion

This study has implications for nonprofit fundraising marketing, as VR notably enhances empathy through increased spatial presence, which is crucial since empathy frequently drives prosocial behavior (e.g., Davidov et al., Reference Davidov, Vaish, Knafo-Noam and Hastings2016; Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Eggum and Di Giunta2010). However, our study indicates that empathy alone does not automatically lead to donations. Fundraising strategies using VR should incorporate additional variables and features (e.g., embodiment) to enhance the likelihood of donations. This is vital as individual donations represent a big share of charitable organizations’ incomes (Gugenishvili et al., Reference Gugenishvili, Francu and Koporcic2022). From a broader perspective, the study contributes to understanding behavior in VR. This is particularly important now that the pandemic has brought the metaverse to the fore, with Microsoft, Meta, and Apple all actively working on its development (Giacomo, Reference Giacomo2021).

The study’s small sample size limits our ability to establish causation or attribute empathy variations to spatial presence. Additionally, we did not explore the differences between voluntary and involuntary attention allocation, which could shed light on what aspects of VR are most effective. Future research will also benefit from incorporating physiological data, such as pulse, brain activity, and sweating, for a more comprehensive understanding. Furthermore, our study did not distinguish between victim groups, neglecting to measure participants’ perceptions of children as ingroup or outgroup strangers. Even though Tassinari et al. (Reference Tassinari, Aulbach and Jasinskaja-Lahti2022) suggests that users feel equally empathetic toward ingroup and outgroup, occasionally this is not true (Gugenishvili, Reference Gugenishvili2022b). Also, to evaluate the participants’ propensity for donations, we inquired if they would contribute in the event of winning the prize. This measure aligns with previous findings (refer to Gugenishvili, Reference Gugenishvili2022a; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Rodas and Torelli2020). It could be argued that participants might not see the funds as their own, possibly affecting their donation choices. Future research should consider using actual donations from participants’ personal funds for more accurate results. Despite some overlap with prior studies, this is the first to explore spatial presence, attention allocation, spatial situation modeling, empathy, and donation behavior together, enhancing our understanding of VR and prosocial behavior.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Åbo Akademi University. Open access funding provided by Åbo Akademi University.

Data Availability

Data available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11366581.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.