Learning objectives after reading this chapter:

After reading this chapter you will have a historical overview of CBT and begin to appreciate how elements of this therapy developed over time. You will be able explain CBT to clients in a more enriched way as you appreciate the fundamental principles of this approach. You will be better able to appreciate the uniqueness of CBT as a psychotherapy and differentiate it from other structured evidence-based therapies. You will have a better knowledge about how behavioural and cognitive elements of CBT interact to enhance treatment.

Introduction

The Spanish Philosopher, George Santayana [Reference Santayana1], reflected, ‘Those who ignore history are doomed to repeat it’ (p. 45). This should contain particular resonance for therapists as we witness clients recount episodes of past and present events that appear to resonate with other episodes of imagined failings. One may also reflect that an understanding of how CBT developed, and an appreciation of historical antecedents and milestones in establishing the fundamental principles of CBT, provide a greater appreciation of how to make therapy sessions bespoke but within guidelines. A firm understanding of how CBT developed and the important principles that helped set it apart from other therapies available at the time allows one an insight into what are the important theoretical elements and how the concepts of cognitive change allied to behavioural change has been so crucial to the creation of a mainstream standard psychological treatment – forget that and perhaps we forget the heart of what we do. This chapter allows you some insights that may enhance your theoretical and conceptual coherence as a CBT therapist.

Landmark Developments for CBT: Cognitive Therapy

In the form most commonly applied in the UK, CBT arose out of the work of Aaron T. Beck in the late 1950s and early 1960s when he developed Cognitive Therapy (CT), now more commonly known as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy or CBT. The first and arguably most important landmark development in the founding of CT is the explicit commitment to psychotherapy as science [Reference Clark and Beck6]. The adherence to an evidence-based approach is fundamentally important and should remain so to any practitioner of CBT. Beck drew heavily on the scientific orientation of behavioural approaches and was also appreciative of the cognitive orientation of peers such as Albert Ellis, but differences in philosophy and adherence to protocol-driven approaches resulted in CBT and rational-emotive behaviour therapy (REBT) sharing some roots but taking different paths [Reference Padesky2,Reference Ruggiero, Spada, Caselli and Sassaroli3]. Without question Beck was also heavily influenced by his original training as a psychoanalyst. Initially as a young man, Beck was more interested in neurology as a medical intern and as this specialism required a rotation in psychiatry he was, reluctantly, introduced to the area that would quickly become his life’s passion and work. In 1954, Beck joined the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania (PENN) in Philadelphia and he started to conduct research seeking to prove the efficacy of psychoanalytic psychotherapy. Beck noticed, and was intrigued by, the importance thoughts appeared to play in the maintenance of depression in his clients. As he sought to find more effective methods to help his clients overcome their problems he moved further away from the theory and practice of psychoanalysis (for an excellent first-hand account see [Reference Beck4]).

From the beginning, Beck sketched out the nature of negative cognitive distortions as being spontaneous, requiring little effort to generate, plausible, mood congruent, idiosyncratic and self-perpetuating [Reference Beck5,Reference Beck and Ward7]. Cognitions were to be tested and evaluated rather than simply disputed providing a strong collaborative approach to CBT from the outset. As Beck developed his model of psychopathology he explored and described the impact of cognitive distortions identified as self-generating and punitive reflecting negative themes such as failure, inadequacy and so on [see Reference Beck and Ward7,Reference Beck4]. Beck set out to chart a coherent intervention for psychotherapy to systematically challenge distortions by differentiating the theme of cognitions in the content-specificity hypothesis where for example anxiety generating cognitions revolve around themes of threat while depression generates cognitions revolving around themes of failure and rejection [Reference Beck8].

To Beck, it was evident in depression and the anxiety disorders that there were mood-congruent biases in recall and general memory biases for negative events [see 9 for review] that maintained these conditions. The Beck model proposed a stress-diathesis as helpful for understanding idiosyncratic predispositions for the development of common mental health conditions [Reference Clark and Beck6]. Simply put the diathesis reflects predisposing, underlying (and usually latent – i.e. not yet activated) vulnerabilities that when activated by a matching, or congruent stressor, leads to activation of a depression or anxiety disorder. Beck noted ‘Early adverse events foster negative attitudes and biases about the self, which are integrated into the cognitive organization in the form of schemas; the schemas become activated by later adverse events impinging on the specific cognitive vulnerability and lead to the systematic negative bias at the core of depression’ [Reference Beck10, p. 970]. Thus, latent diatheses (vulnerabilities) when activated facilitate the core beliefs, or schemata, through which individuals process their experiences and which determine emotional and behavioural responses to situations and stimuli. To simplify, Beck’s approach to CBT has three main elements:

Cognitive processing errors

Errors in cognitive content

Beliefs and idiosyncratic appraisals/pre-existing vulnerabilities (schema activation in a stress-diathesis)

As Beck’s approach developed apace his theoretical, conceptual and intervention approach so deviated from psychoanalytic and psychodynamic principles that his approach was rejected by his psychoanalyst peers [Reference Beck and Fleming11]. By helping his clients recognise the interactions of thoughts, feelings, behaviours and physical sensations a method of treatment was developed that alleviated distress and promoted active and positive behavioural and cognitive change. At this point in the development of CBT, Beck was influenced by the cognitive approach to depression pioneered by Albert Ellis [Reference David, Cotet, Matu, Mogoase and Stefan12,Reference Ellis13] and he was also influenced by behavioural theories of depression [Reference Lewinsohn, Freedman and Katz14] developing behavioural activation (BA) and Seligman’s theories of learned helplessness [Reference Seligman15]. Around this time Beck [Reference Beck16,Reference Beck17] created an elegantly simple formulation for the development of depression or anxiety symptoms that was easily grasped and understood by clients especially as the linked strategies to deal with negative affect and cognition were so elegantly and simply connected and easily implemented in daily life as homework strategies. For example when a client says ‘I see myself as weak now, I just keep expecting things to go wrong for me and I suppose I give up when I hit a hurdle.’ The CBT therapist is able to help a client reflect not just on what is said but on the impact of these if they were to act as if the thoughts were 100% valid. Being able to introduce clients to thought monitoring and challenging while introducing related behaviour change via behavioural experiments (e.g. homework, pleasant event scheduling, etc.) is a very powerful set of interventions. To the extent that this can seem such a simple technique one must bear in mind the warning by Beck [Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery18], ‘Cognitive and behavioural techniques often seem deceptively simple’ (p. 46). Something so apparently simple but so powerful is unlikely to work without the professional skills, experience and humanity of therapists. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy is not delivered by technicians but by knowledgeable, compassionate and competent therapists.

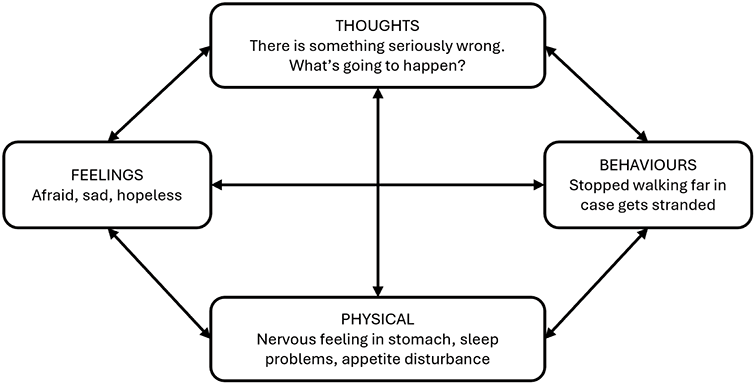

The simplest four components model of CBT, where thoughts (cognitions) are seen to create negative affect (feelings such as sadness or fear) with behavioural consequences (self-isolation, avoidance), and consequent physical sensations (fatigue/sleep disturbance, butterflies in the stomach) is commonly known as the hot cross bun model. The example here is of a man who has developed health-related anxiety linked to sensations in his legs when he goes out for a walk (Figure 1.1). He becomes concerned that he may become stranded and unable to seek help with catastrophic consequences imagined.

Figure 1.1 The four central components of CBT.

Figure 1.1Long description

At the top, a box labeled Thoughts includes the text There is something seriously wrong, What’s going to happen. To the left, a box labeled Feelings includes Afraid, sad, hopeless. At the bottom, a box labeled Physical includes Nervous feeling in stomach, sleep problems, appetite disturbance. To the right, a box labeled Behaviours includes Stopped walking far in case gets stranded. Arrows point in both directions between each box.

We are aware that when we change one element of this model we change all elements. It may be hard to recognise how revolutionary this approach was to managing common mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety when it was first proposed. What was also revolutionary at the time was the collaborative nature of the therapeutic relationship with the client. The therapist was not seen as the omniscient expert sagely directing the client to make changes in their life but takes the role more of the equivalent to a sports coach empowering the client to take control of their thoughts, feelings and behaviour. In doing so, Beck accepted Carl Rogers’ tenets of warmth, genuineness, unconditional acceptance and empathy (congruence) and these bedrock elements of CBT have remained key to good effective CBT ever since [Reference Nienhuis, Owen, Valentine, Winkeljohn Black, Halford and Parazak19]. Beck outlined his approach into a systematic format for psychotherapy that he called CT, that emphasised a scientific, evidence-based, open, transparent, collaborative psychotherapy where clients were empowered to help themselves in the here and now. Hammen [Reference Hammen20, p. 1067], a significant researcher into CBT, wrote her reflections on the change that CBT brought about as follows:

The cognitive revolution that had enormous impact throughout psychology during the late 1960s and 1970s, took the form of a virtual tidal wave in clinical psychology. Increasing numbers of investigators – now armed with a major theoretical perspective as well as new research diagnostic criteria with high reliability – applied Beck’s model to the measurement and study of cognitive processes as they contributed to depression and to the treatment of depressed individuals.

While recognising similarities in approach between CT and BT [Reference Beck5], Beck [Reference Beck16,Reference Beck17] differentiated CT from Behavioural Therapy for depression and emphasised the importance of cognitive restructuring for symptom relief. These historical antecedents remain fundamental for a good outcome to this day. They also emphasise that CBT therapists ought to have a strong appreciation of the strengths and values of other forms of psychotherapy that demonstrate a methodological approach to scientific evaluation [Reference Beck16,Reference Beck17,Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery18].

In the UK, pioneering work by David Clark and Paul Salkovskis, amongst others at Oxford in the 1980s, took the fundamentals of Beck’s model of psychopathology and developed elegant condition-specific models for the anxiety disorders guiding treatment interventions [Reference Ruggiero, Spada, Caselli and Sassaroli3]. Empirical research demonstrated the power of CBT to help people overcome a range of anxiety disorders and CBT is now recognised as a frontline treatment for many common anxiety conditions. A number of concepts around emotional regulation, attention deployment and so on, became useful in other clinical presentations besides anxiety disorders, with the result that CBT has become a more complete treatment approach for common mental health conditions and as such is National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommended for a number of these conditions.

Landmark Developments for CBT: Scientific Evaluation of Cognitive Therapy

By the 1970s Beck had published some key scientific treatises on the models for CT but he provided evidence for the efficacy of CBT as a treatment for depression in a landmark paper in 1977 [Reference Rush, Beck, Kovacs and Hollon21] and a bestselling treatment handbook [Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery18] and as CT became extensively evaluated across the world, for a range of psychological conditions, CT became more commonly known as CBT in the process.

Beck continued to refine the approach and philosophical orientation of CBT and set in stone an emphasis on the importance of scientific validation of CBT as a treatment intervention. Beck conducted the first randomised controlled trial (RCT) of CBT for depression in 1977 [Reference Rush, Beck, Kovacs and Hollon21]. This seminal paper was amongst the first to demonstrate that a psychological treatment could be more efficacious than a physical treatment (antidepressant medication) for depression. As Beck and colleagues compared CBT to tricyclic antidepressant medication at the correct dosage this test was a very robust one for any type of psychotherapy and helped establish the empirical nature of CBT as an evidence-based protocol driven therapy.

In 1977, Beck and research colleagues [Reference Rush, Beck, Kovacs and Hollon21] proved for the first time that a psychotherapy (talking cure) such as CBT could perform better than medication in the treatment of depression. This amazing finding was quickly replicated by Ivy-Marie Blackburn and colleagues in Edinburgh in 1981 [Reference Blackburn, Bishop, Glen, Whalley and Christie22]. By 1982 CBT was shown to help older people manage depression too and by the mid 1980s David Clark and Paul Salkovskis were leading the way in showing that CBT was the first-line treatment for anxiety disorders. Consequently, interest in CBT as an efficacious treatment took off where nowadays CBT is seen as a mainstream treatment for common mental health conditions.

The principles of CBT and the structured nature of this approach specified by Beck ensured it was more amenable than other forms of psychotherapy for evaluation in scientific studies such as RCTs and ensured its wider evaluation across a range of mental health conditions and with a range of clinical populations. The paper by Rush and colleagues [Reference Rush, Beck, Kovacs and Hollon21] also helped launch a new journal, Cognitive Therapy and Research. The treatment manual for this study was published in 1979 as the highly influential book by Beck and colleagues called Cognitive Therapy of Depression [Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery18]. At this time the early pioneers of CBT were seen as being part of an innovative and radical approach to mental health treatment.

The Importance of the Behavioural Model of Depression and Behavioural Activation for CBT

The behavioural model for depression has a simple but effective approach to understanding and treating depression where a substantial portion of the most salient positive reinforcers in an individual’s life are considered to be interpersonal in nature. Lewinsohn was the early pioneer of behavioural treatments for depression and his influence is still very evident in contemporary protocols for BA [Reference Dimidjian, Barrera, Martell, Muniz and Lewinsohn24,Reference Kanter, Puspitasari, Santos and Nagy25].

Lewinsohn’s behavioural model of depression [Reference Dimidjian, Barrera, Martell, Muniz and Lewinsohn24,Reference Kanter, Puspitasari, Santos and Nagy25,Reference Lewinsohn, Munoz, Youngren and Zeiss26] is very simple, suggesting that when depressed individuals engage in less social interaction and less positive social interactions, this results in an increased frequency of negative events and a reduction in positive events that in turns acts as the antecedent condition with depression as the outcome. Behavioural activation constructed collaboratively with clients is the key component of any behavioural intervention, and many CBT interventions, for depression and anxiety.

Reduction in engagement in valued roles and goals in a person’s life is a key antecedent to the development of depression.

A landmark paper by Jacobson and colleagues [Reference Jacobson, Dobson, Truax, Addis, Koerner, Gollan and Gortner27] ignited a debate about the key treatment elements of structured psychological therapies. This intriguing study addressed the question as to what are the effective treatment ingredients of CBT for depression. The study compared 152 people who met criteria for major depressive disorder who were randomly allocated to receive either BA alone, or BA with activation and challenging dysfunctional thoughts (Automatic Thoughts (AT) condition) or full CBT that included challenging core beliefs delivered by four experienced CBT therapists. Contrary to expectations, BA performed as well as full CBT at the end of treatment and at six-month follow up. Gortner and colleagues did a longer follow up in 1998 and demonstrated no differences between treatment conditions in terms of relapse prevention. Behavioural activation, AT or CBT were all equally effective as a treatment for depression. What was intriguing about this study was that all three conditions produced equal amounts of change in activity, dysfunctional cognitions and reductions in attribution of negative events due to core beliefs. The main effect of this paper was to provide an impetus to the development of BA as a standalone treatment and provoke further examination of necessary theoretical components of CBT.

Due to the nature of BA strategies this treatment can be learned relatively quickly and can be effectively delivered by people with less psychotherapy training [Reference Richards, Ekers, McMillan, Taylor, Byford and Warren28] which has led to its wider adoption with a range of clinical populations.

While earlier models largely ignored cognitions more modern BA protocols recognise their importance [Reference Dimidjian, Barrera, Martell, Muniz and Lewinsohn24,Reference Kanter, Puspitasari, Santos and Nagy25]. Lejeuz and colleagues [Reference Lejuez, Hopko, Acierno, Daughters and Pagoto23] developed the behavioural activation treatment manual for depression which emphasised focus on values, roles and goals and also emphasised the therapeutic alliance by focussing on meaningful treatment rationales linked to an individual’s problems. Martell and colleagues [Reference Martell, Dimidjian and Herman-Dunn29] incorporated a more formulation-like approach (Trigger, Response, Avoidance Pattern – TRAP), into BA models via functional analysis focussing on understanding context, the role and function of avoidance behaviours and translating negative consequences of behaviour into powerfully reinforcing positive actions. The ‘cognitive’ type approach adopted in the Martell model of BA sees the interaction of cognition and behaviour as follows, ‘The behavioral activation therapist accepts her client’s thinking, but encourages clients to look at the context of thinking rather than at the content of thoughts’ [Reference Martell, Dimidjian and Herman-Dunn29, p. 64]. Meaningful behavioural engagement with a more context-dependent understanding of reinforcement contingencies, and sophisticated cognitive behavioural interdependencies in contemporary accounts of BA, provide for a more sophisticated articulation of the behavioural model for depression.

Beck [Reference Beck5] noted CT and BT share common elements as they are much more structured, are symptom focussed, with an emphasis on the ‘here and now’, use direct reports from clients without need for interpretation and distress is a result of maladaptive reaction patterns with a focus on maintaining factors rather than on origins of symptoms.

Behavioural Activation on its own appears to be efficacious [Reference Dimidjian, Barrera, Martell, Muniz and Lewinsohn24,Reference Richards, Ekers, McMillan, Taylor, Byford and Warren28] and as an intervention has a number of effective ingredients (mediators of effect) but this can be more complex to quantify [Reference Janssen30, p. 27]. Nevertheless, having a client become more engaged in activities that may provide a tangible sense of achievement and noticeable positive impacts on affect directly challenges an individual’s negative appraisals and can act as a motivator to engage in more pleasurable activities. Once ‘activated’ a person may notice that their self-esteem improves, their relationships improve and a more positive self-sustaining cycle starts. Behavioural Activation and CT are complementary processes and BA is an essential effective ingredient of any treatment plan within CBT.

Lewinsohn’s behavioural model for depression [Reference Lewinsohn, Freedman and Katz14,Reference Lewinsohn, Munoz, Youngren and Zeiss26] suggests a vicious cycle develops as a person becomes depressed. As a person’s mood becomes lower, reduced engagement in activities and hobbies that previously were experienced as pleasurable and enjoyable results in further reduction in activity overall and the increased opportunities for rumination. As depression becomes more established the potential availability of reinforcers becomes reduced for the person as they can become increasingly aversive for others to interact with them, and as a consequence. the depressed person becomes more isolated and alone. This can result in more time dwelling on negative thoughts and a consequent impact on mood and behaviour.

Concluding Remarks

All formats of CBT therapies share a rich history with a common thread of being scientific, evidence-based and collaborative, problem focussed and structured. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy has never stopped developing since its inception in the 1960s and over that time a more sophisticated understanding of mechanisms of change has seen new variants of CBT emerge. Since the first paper demonstrated efficacy for CBT there has been an explosion in publications demonstrating evidence across settings, across the lifespan, range of clinical conditions and across all common mental health conditions. So much has been done but much more remains to be done and each generation of CBT therapists will add to the strength of this community. As CBT is increasingly more widely applied with more clinical populations than ever before CBT increasingly is recognised as a frontline mainstream treatment approach for common mental health conditions.