Introduction

Ex situ conservation of crop genetic resources is recognized as a key aspect of ensuring the future of sustainable food production systems (Schmitz et al. Reference Schmitz, Barrios, Dempewolf, Guarino, Lusty, Muir, von Braun, Afsana, Fresco and Hassan2023). Saving seeds, tissues, and plants to replant preferred crops has been an important part of agricultural systems since early farmers began domesticating and migrating crop plants (Labeyrie et al. Reference Labeyrie, Deu, Barnaud, Calatayud, Buiron, Wambugu, Manel, Glaszmann and Leclerc2014). This has impacted the distribution and degree of local plant diversity, which are important resources for the future but are now at risk of genetic erosion.

Gepts (Reference Gepts2006) explains that the recognition of the value of crop diversity – and the threats to its conservation from changes in farming, improved crop varieties, land use, climate and other challenges – led to the establishment of ex situ collections. Hufford et al. (Reference Hufford, Berny Mier Y Teran and Gepts2019) demonstrate the critical need for conservation as an insurance policy for the adaptability and resilience of agriculture and managed ecosystems.

There are many challenges to ensuring secure, sustainable, rational and efficient long-term conservation of genetic resources ex situ (Gepts Reference Gepts2006; Fu Reference Fu2017; Hay Reference Hay2019; Engels and Ebert Reference Engels and Ebert2021). The long-term conservation and use of seeds, tissue and plants require complex routine operations to maintain the genetic integrity of the original sample of diversity and make it available to users. Most of the major crops in ex situ collections are orthodox seeds that can be stored in seed banks. Panis et al. (Reference Panis, Nagel and Van Den Houwe2020) discuss the complexity and cost for the conservation of recalcitrant seeds or other species that are clonally propagated and require conservation in field, in vitro or cryopreservation. Thus, the cost, efficiency and long-term sustainability of the collections’ conservation are related to composition in terms of the strategic representation of genetic diversity of species and accessions within species, breeding system, biological type and the orthodox or recalcitrant nature of the seed in relation to the long-term storage required. Fu (Reference Fu2017) concludes that collection size and composition are key vulnerabilities, which influence cost and sustainability. Mitigating this vulnerability requires careful consideration of the value and future use for individual accessions, crop, genera or species.

There is a need to characterize the composition of collections as an important criterion for improved efficiency and securing long-term conservation of priority genetic resources. The FAO Genebank Standards (FAO 2014) do not have a specific standard or indicator related to the level of diversity conserved by collections individually or within the global system. There is only a recognition that these accessions should be unique with minimal duplication, and the genetic integrity of the original sample should be maintained through all the genebank operations. Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Indicator 2.5.1a ‘Number of plant genetic resources for food and agriculture secured in either medium- or long-term conservation facilities’ is reported as the number of accessions in a conservation facility, either medium- or long-term that is maintained by the genebank. United Nations Statistics Division (2024) discusses issues of concern in the use of the ‘number of accessions’ as an indicator of diversity in ex situ collections due to undetected redundancy that could increase or decrease the number of accessions within genebanks or in the global system. This indicator is also inadequate for quantifying and monitoring the conservation of genetic diversity within individual accessions. Thus, relying on the total number of accessions or genera conserved as an indicator of collection diversity may not be adequate. More informative indicators that better assess the degree and distribution of diversity may be needed to manage the composition for the future, both for individual genebanks and across the global system.

History of ex situ conservation of crop genetic resources

Pretorius (Reference Pretorius1997), Gepts (Reference Gepts2006), Engels and Ebert (Reference Engels and Ebert2024) and Hay (Reference Hay2019) have reviewed the long history of ex situ conservation of crop genetic resources. Fu (Reference Fu2017), Díez et al. (Reference Díez, De La Rosa, Martín, Guasch, Cartea, Mallor, Casals, Simó, Rivera, Anastasio, Prohens, Soler, Blanca, Valcárcel and Casañas2018) and Begemann et al. (Reference Begemann, Thormann, Sensen and Klein2021) describe the history of the national systems in the United States, Spain and Germany, respectively. Hanson et al. (Reference Hanson, Williams and Freund1984) described the operation of the International Board for Plant Genetic Resources (IBPGR) global network of base collections and the institutes involved. Engels and Ebert (Reference Engels and Ebert2021) attribute the development of the global ex situ conservation system to the IBPGR base collections and the international undertaking that established international, regional, and national collections for the conservation of base collections. This system for collecting, characterizing, and conserving crop genetic resources for the long term was incorporated into the International Treaty for Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA). Engels and Ebert (Reference Engels and Ebert2021) provide a working definition of the global conservation system as:

A long-term global plant agrobiodiversity conservation system of well-defined national and international ex situ seed, tissue and plant collections that is managed under agreed genebank quality management standards and in harmony with the prevailing political framework regarding access and benefit sharing, and that aims at safe, effective, efficient and rational long-term conservation and facilitating use by making high-quality accession-level information available.

Pretorius (Reference Pretorius1997), Gepts (Reference Gepts2006), Engels and Ebert (Reference Engels and Ebert2021), Engels and Ebert (Reference Engels and Ebert2024), Hay (Reference Hay2019), Fu (Reference Fu2017), Díez et al. (Reference Díez, De La Rosa, Martín, Guasch, Cartea, Mallor, Casals, Simó, Rivera, Anastasio, Prohens, Soler, Blanca, Valcárcel and Casañas2018) and Begemann et al. (Reference Begemann, Thormann, Sensen and Klein2021) conclude that the process of collecting, exchanging and conserving has not necessarily been efficient nor rational. This has resulted in a global ex situ conservation system that consists of international, regional and national collections that conserve a set of crops, crop wild relatives, traditional cultivars/landraces and breeding materials with varying degrees of redundancy. Many of these accessions are poorly conserved, poorly documented, not easily accessible and are at risk of loss.

Van Treuren et al. (Reference Van Treuren, Engels, Hoekstra and Van Hintum Th2009) also conclude that in the past, collections were developed without a clearly defined conservation goal or mandate, taking a more opportunistic approach to acquire a broad diversity of priority crops, such as acquiring any material that could be accessed from other researchers in the institute or targeted collecting missions to address the needs of specific projects or users. This has resulted in collections that are now large and complex with a potentially high degree of duplication.

Engels and Ebert (Reference Engels and Ebert2021) discuss two issues with current base collections since many collections were based on initial accessions transferred from breeding programmes that were then stored for long-term conservation. They concluded that there are weaknesses in existing base collections, such as poor representation of wild species and traditional cultivars/landraces and duplication of accessions and that rationalization needed to focus on the most original accessions.

Van Treuren et al. (Reference Van Treuren, Engels, Hoekstra and Van Hintum Th2009) review methods that have been suggested for rationalization. These include the approach that Sackville Hamilton et al. (Reference Sackville Hamilton, Engels, Van Hintum Th, Koo and Smale2002) describe to set sub-groups, either within crops or across crops, and assign accessions to these groups. The current allocation to the sub-groups is compared with the optimal allocation to quantify the imbalance in representation. Van Treuren et al. (Reference Van Treuren, Coquin and Lohwasser2012) use this approach to assess composition at the genepool level for a set of leafy vegetables. They concluded that there were challenges in using global databases, including data availability, data sharing, data quality and alignment between databases. They identified imbalances in composition at the species level that coincided with expert knowledge of known gaps.

Carvajal-Yepes et al. (Reference Carvajal-Yepes, Ospina, Aranzales, Velez-Tobon, Correa Abondano, Manrique-Carpintero and Wenzl2024) conclude that culling two accessions as identical is a challenge when considering redundancy due to the difficulty of defining an appropriate genetic distance threshold. Their approach integrated molecular data to identify potential duplicates or groups of duplicates, with passport and characterization data then used to confirm authenticity and duplication. Anglin et al. (Reference Anglin, Wenzl, Azevedo, Lusty, Ellis and Gao2025) reviewed the use of genotyping to address issues in collection management related to the identification and rationalization of accessions conserved as seed or as in vitro or field plant collections. Anglin et al. (Reference Anglin, Wenzl, Azevedo, Lusty, Ellis and Gao2025) concluded that there is a need to establish global networks for genotyping all of the individual crop collections of the major crops that could be used in the global system for identifying redundancies and gaps within and amongst individual collection holders.

Sackville Hamilton et al. (Reference Sackville Hamilton, Engels, Van Hintum Th, Koo and Smale2002), Engels and Visser (Reference Engels and Visser2003) and Hanson et al. (Reference Hanson, Lusty, Furman, Ellis, Payne and Halewood2024) describe curation options to manage duplicates in collection management. Stratified curation is a dynamic process for managing collection composition, involving decision-making at the time of acquisition and throughout subsequent stages, as priorities for accessions and crops evolve. It recognizes that managing collection composition would benefit from sharing long-term conservation responsibilities with other conservers across the global system.

Ramirez‐Villegas et al. (Reference Ramirez‐Villegas, Khoury, Achicanoy, Mendez, Diaz, Sosa, Debouck, Kehel and Guarino2020) describe and use a process to identify and prioritize gaps in collection composition in relation to traditional cultivars/landraces. This gap analysis is an opportunity to improve the composition of a collection by identifying taxon or accessions that are also over-represented. It could also be used to identify areas where past collections have been made, but where changes in variety composition, seed management practises, substantial environmental or land use changes may have driven new adaptations in the local landraces or wild populations, such as changes in maturity or water use efficiency (Thormann et al. Reference Thormann, Reeves, Thumm, Reilly, Engels, Biradar, Lohwasser, Rner, Pillen and Richards2018) may require recollection. Ramirez‐Villegas et al. (Reference Ramirez‐Villegas, Khoury, Achicanoy, Mendez, Diaz, Sosa, Debouck, Kehel and Guarino2020) discussed some key challenges to gap analysis, particularly the limitations to landrace distribution modelling arising from the lack of national collection data in global databases, including incomplete passport and coordinate information.

Singh et al. (Reference Singh, Wu, Raupp, Sehgal, Arora, Tiwari, Vikram, Singh, Chhuneja, Gill and Poland2019) and Engels and Thormann (Reference Engels and Thormann2020) recommend actions needed to address gaps and challenges in ex situ conservation of wild species. Korpelainen (Reference Korpelainen2023) discusses the importance of conservation and use of genetic resources found in home gardens. Casañas et al. (Reference Casañas, Simó, Casals and Prohens2017) recognize the dynamic nature of traditional cultivars/landraces and concluded that traditional cultivars/landraces are evolving entities that have direct use by farmers, not just a reserve of genes for breeders, that influences their collecting and conservation approaches.

There are still significant needs to expand ex situ conservation. The development of a curation policy that describes a clear process and decision framework to rationalize the collection is an important first step in the management of redundancies, gaps and new acquisitions. Engels and Ebert (Reference Engels and Ebert2021) describe the criteria that should be used when deciding to add a new accession. One key action is to determine if collections have been made in the past and if these are safely conserved and available in the global system in other institutions. If not, then they might need to recollect or acquire through exchange with other institutions. A curation policy could be extended to include multiple collection holders who agree to collectively rationalize and manage a crop composition, such as the virtual European collection conserved by AEGIS Associate members (https://www.ecpgr.org/aegis/european-collection/european-collection).

There have been substantial achievements in building a global system to safeguard crop genetic diversity, but also long-standing inefficiencies in how collections were assembled and managed. While genebanks now hold extensive material, many collections remain duplicated, unevenly documented, and incomplete. Emerging tools in genomics and data sharing, continued coordination, clear curation policies, and shared responsibility across institutions will be key to ensuring these conserved resources remain both secure and useful for future agricultural needs. In this context, the objectives of this study are to characterize the composition of the holdings of 20 national genebanks, to describe the degree and distribution of diversity within the global ex situ conservation system for accessions originating from the 20 selected countries, and to assess potential duplication or significant gaps in representation in the global ex situ conservation system.

Materials and methods

This study included 20 genebanks that participated in the Seeds for Resilience (SFR) (https://www.croptrust.org/work/projects/seeds-for-resilience/) and the Biodiversity for Opportunities, Livelihoods and Development (BOLD) (https://bold.croptrust.org/) projects, implemented by the Crop Trust. The genebanks, along with their corresponding World Information and Early Warning System on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (WIEWS) institute codes, were from Ethiopia (ETH085), Ghana (GHA091), Kenya (KEN212), Nigeria (NGA010) and Zambia (ZMB048) from the SFR project and Azerbaijan (AZE015), Bhutan (BTN026), Cuba (CUB014), Ecuador (ECU023), Egypt (EGY087), Laos (LAO018), Lebanon (LBN020), Morocco (MAR088), Pakistan (PAK034), Peru (PER773), Sudan (SDN002), Tanzania (TZA016), Uganda (UGA528), Vietnam (VNM049) and Yemen (YEM061) from the BOLD project.

Jamora et al. (Reference Jamora, Bramel, Hanson, Guarino, Kilian, Krishnan, Bolton, Castañeda-Álvarez, Heaton, Amri, Dulloo, Nagel, Borja, Adkins, Pritchard, Popova, Shahid, van Hintum, Norton, Vu, Fernández Granda, Vilaheuang, Breidy, Sahri, Tapia, Monteros-Altamirano, Javaid, Kabululu, Akparov, Abbasov, Babiker, Phuntso, Sherab, Hassan, Zaake, Aladele, Nwosu, Kotey and Salamo2025) describe the use of external reviews as a key component of the Crop Trust monitoring and evaluation framework for its partner international and national genebanks. Within this framework, external reviews were conducted for 5 national genebanks through the SFR project and 15 national genebanks through the BOLD project. The 20 genebanks selected for the projects were based on geographical location and spread in the Global South, the importance and level of risk associated with the loss of their collections (Engels and Thormann Reference Engels and Thormann2017), and their prior involvement in the Crop Wild Relative (CWR) project (https://cwr.croptrust.org/).

The areas for review in relation to the composition of the collection included assessing if the genebank conserves unique and valuable crop collections of importance to national and global conservation. The reviewers were asked to identify unique and valuable crop collections that are at risk, check for redundancies or gaps, and determine if particular crops or gaps should be prioritized. These aspects were assessed from the responses to the baseline questionnaire, the onsite validation process, the background document reviews and global accession-level information available on Genesys and/or FAO WIEWS. The assessment was linked to the key performance indicator (KPI) on collection size: The genebank has information/trends on the size and composition of its collection.

The SFR and BOLD projects collected baseline data from each genebank via a structured questionnaire and accompanying data tables. The baseline survey requested information on the number of accessions conserved by crops or taxonomic classification, by biological status and by storage type (seed, in vitro and in the field). It also sought an inventory of accessions, where available. In addition, the baseline requested information on the establishment date of the genebank, the number of accessions when established, history of its establishment and development, the mandate or objectives of the genebank, history of collecting and acquisition, and any known gaps in the composition of the collection.

The information provided in the questionnaires was verified during the site visits. This process included a validation of the inventory database, a verification of the inventory information within the various storage units, and a discussion of priorities for crop conservation and significant gaps in collection. The adequacy of the genebank information system was also reviewed (Jamora et al. Reference Jamora, Bramel, Hanson, Guarino, Kilian, Krishnan, Bolton, Castañeda-Álvarez, Heaton, Amri, Dulloo, Nagel, Borja, Adkins, Pritchard, Popova, Shahid, van Hintum, Norton, Vu, Fernández Granda, Vilaheuang, Breidy, Sahri, Tapia, Monteros-Altamirano, Javaid, Kabululu, Akparov, Abbasov, Babiker, Phuntso, Sherab, Hassan, Zaake, Aladele, Nwosu, Kotey and Salamo2025), so the gaps assessed included gaps in the inventory data as well as in the collection composition.

For the study, we collated accession-level information for each of the 20 genebanks, extracted from the baseline and/or accession-level information on each collection as reported through WIEWS (https://www.fao.org/wiews/en/) and/or Genesys (https://www.genesys-pgr.org/). Accession-level data on Genesys and WIEWS are curated, validated, and updated by the national genebanks. Five of the genebanks only had an inventory from the baseline to share (YEM061, LAO018, CUB014, PER012 and VNM048). We extracted the 2024 data from Genesys for six of the genebanks (AZE015, GHA091, KEN212, NGA010, SDN002 and ZMB048) that had updated the accession-level information as part of the Crop Trust SFR and BOLD projects. For the other genebanks, we extracted the 2024 data from WIEWS. Thus, for each national genebank, there was a database that included the holding institute code, accession number, accepted genus name, accepted species name, acquisition year/month, country of origin and biological status, except when the baseline was used. In those cases, the database included only holding institute code, accession number, genus and species name, and country of origin. In the baseline, the genebanks also reported on the number of accessions within each biological type. The biological status was more than 90% complete for 13 of the national genebanks. For four of the genebanks, more than half of the accessions did not have any data for biological status and this limited the number of accessions that could be used for the assessment of this trait.

WIEWS data from 2024 was the source for all accession-level information at the global level for all other institutes that conserved accessions that had an origin in each of the 20 selected countries. For the study of composition, we combined the data for inventory within each country with that for all accessions originating from that country that were conserved by other institutions. The characteristics of interest included holding institute code, accession number, accepted genus, accepted species, acquisition year/month, country of origin and biological status. The characterization of the distribution of diversity for the 20 selected national genebanks was based upon the number of genera, collection size for accessions of national origin, age of accessions, and biological status using this accession-level information in the individual and combined global datasets.

The distribution of diversity for genera with total accessions conserved within and across the various institutions in the global system of ex situ conservation was assessed. The global status of each genus across institutions was classified as national (solely conserved in the 20 selected national genebanks), global (solely conserved in other institutions in the global system), or both (conserved in national and global). Each genus was then classified for its degree of representation in the global system based on the number of accessions conserved. The classes were low (1–10 accessions), moderate (11–100 accessions), high (101–1000 accessions) and very high (more than 1000 accessions). In addition, each genus within national, global or both types of institutions was then classified for degree of institutional representation in the global system based upon the classification of the genera for the number of institutions (1, 2–5, 6–10, 11–100, 101–200 and more than 200 institutions) where conserved.

The distribution of diversity for the number of genera, the number of accessions conserved globally and in the 20 selected national genebanks was assessed by crop group. The top 269 genera that had more than 50 accessions conserved were identified. Each of these genera was classified into 11 crop types. These were cereals, food legumes, vegetables, forage/fodder/pasture, cash commodities, root crops, oil crops, fruits, herb/spices, medicinal and ornamental. The distribution of diversity amongst the top 48 other institutions in the global system that conserve the highest number of accessions that originated from the 20 countries was assessed. In addition, the top 32 genera were assessed separately. These were selected to ensure that all 11 crop groups were represented. The proportion of the total number of accessions originating from the 20 countries conserved by the 48 institutions that conserve more than 1,000 accessions was determined for each of the top genera and compared with the number of accessions conserved by the 20 national genebanks for each of the top genera. The 48 top institutions were also assessed for the number of genera conserved.

Results

The national genebanks that partner with the Crop Trust in the BOLD and SFR projects are significant contributors to the global conservation system. The 20 partner genebanks conserve 338,228 accessions from 1,829 genera that were national in origin (Table S1). Globally, there are 358 institutes that conserve 722,246 accessions of 2,368 genera that originate from the 20 countries. Based on the total number of accessions, genera and institutes in the global system from FAO WIEWS, 12% of the total number of accessions globally have originated from the 20 countries and these accessions are collectively conserved by 32% of the institutions.

Distribution of diversity by genera and collection size

The 20 genebanks have diverse and complex compositions, based on both the number of genera and accessions per genera. The size of the ex situ collections ranges from 2,351 accessions for LBN020 to 71,447 accessions for ETH085. The majority of the genebanks conserved more than 10,000 accessions. The largest collections were in national genebanks in Ecuador, Ethiopia, Kenya and Pakistan. The number of genera conserved in the 20 genebanks ranged from 23 in LAO018 to 897 in KEN212. Four genebanks conserved more than 300 genera, while 7 genebanks conserved fewer than 55 genera.

The total number of accessions conserved in the global system for each of the 20 countries ranges from less than 4,500 for Bhutan to nearly 140,000 for Ethiopia (Table S1). Accessions originating from Ethiopia accounted for about 20% of the total number of accessions conserved from the 20 countries. Sixteen countries had from 10,000 to 50,000 accessions conserved in the global system. The national genebanks in Bhutan, Ghana and Kenya conserved more than 70% of the national accessions in the global system. Overall, the proportion of the total number of accessions conserved globally that was conserved by the 20 national genebanks in this study was about 46%.

The number of genera conserved globally from the 20 countries ranges from 60 genera for Bhutan to 936 genera for Kenya. For those accessions that originate nationally, the 20 national genebanks conserved 77% of the genera that are conserved globally. More than 400 genera were conserved globally for Azerbaijan, Ecuador, Ghana, Kenya, Lebanon and Tanzania. For these five countries, the proportion of the globally conserved genera that are conserved nationally ranged from 15% for TZA016 to 96% for KEN212. In contrast, two countries – Bhutan and Laos – only had about 60 genera conserved in the global system. BTN026 conserved 77% of these, while LAO018 conserved 34% of the genera conserved globally.

Overall, for these 20 national genebanks and countries, there was no clear relationship between the number of genera and the number of accessions at the genebank or global system level. The Spearman’s correlation was conducted to quantify the relationship between the rank of genera and accession number conserved from each country nationally with the rank for total plant biodiversity (https://worldrainforests.com/03plants.htm) or the rank for total land area (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_and_dependencies_by_area). The correlation coefficient between the number of genera and total plant biodiversity (r = 0.50) was significant at the p < 0.05 level. The correlation coefficient between the number of genera and the total land area was not statistically significant. Generally, the difference in the genera and total number of accessions conserved nationally for these 20 countries was not highly related to the total land area of the country and the total plant biodiversity nationally.

Distribution of diversity by biological status

Biological status is considered a measure of diversity within and amongst accessions. We determined the proportion of the accessions in each country for wild/weedy or traditional cultivar/landrace (Fig. 1). There was no data available for PER012 on biological status. In four of the countries (CUB014, ECU023, KEN212 and UGA132), more than 50% of the accessions did not have data for biological status. The limited data indicated that CUB014 had no wild/weedy type accessions and a very low percentage of traditional cultivars/landraces and mainly conserved breeding material. There were two national genebanks, LBN020 and MAR088, that conserved a high proportion of wild/weedy accessions. Eleven national genebanks had none to less than 10% of the accessions with status wild/weedy. Across all the genebanks, only 9% of the accessions were wild/weedy.

Figure 1. The proportion of total accessions in each national genebank that have a wild/weedy or a traditional cultivar/landrace biological status.

National genebanks generally conserve a high proportion of local traditional cultivars/landraces (Fig. 1). In eight of the national genebanks, 75–100% of all the accessions are traditional cultivars/landraces. In contrast, three national genebanks – CUB014, AZE015 and LBN020 – have less than 15% of the accessions that are classified as traditional cultivars/landraces. ECU023, MAR088, UGA132 and KEN212 have less than 40% traditional cultivars/landraces.

Distribution of diversity within the global system

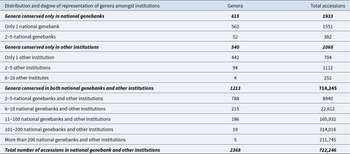

We assessed the distribution of diversity amongst genera across the various institutions in the global system of ex situ conservation. Table 1 gives the distribution of the number of genera with the number of accessions that are conserved in the national genebanks only, in other institutions in the global system only, or in both. The national genebanks solely conserved 25% or less of the genera in the global system in their collections. ECU023, GHA091 and KEN212 conserve 83% of the genera that were solely conserved by the national genebanks. Only two genera with more than 100 accessions were solely conserved by national genebanks: Lallemantia in VNM049 and Alpinia in PAK001. A similar proportion (23%) of the genera were only conserved in other institutions in the global system. Two genera are only conserved globally. Uapaca accessions that originated from Tanzania and Zambia are only conserved by ICRAF (KEN023). Arabidopsis accessions that originated from Azerbaijan, Lebanon, Morocco, Pakistan and Tanzania are conserved by FRA065 (14 accessions) and GBR140 (136 accessions).

Table 1. The total number of genera with total number of accessions that are conserved in the global system by only in the 20 selected national genebanks, only in global institutions, or in both subdivided further for the degree of genera representation in the global system based upon the classification for the number of accessions into low (1–10 accessions), moderate (11–100 accessions), high (101–1000 accessions) and very high (more than 1000 accessions) for the selected national genebanks only, the other global institutions only, and both

In general, 75% of the genera had a low number of accessions represented by only 1–10 accessions conserved nationally, globally and both. Conversely, 159 genera with more than 100 accessions account for 96% of the accessions conserved in the global system. A high degree of concentration of conservation in the global system is evident, given that 50 genera with more than 1,000 accessions accounted for 86% of all accessions conserved by both national and global institutions.

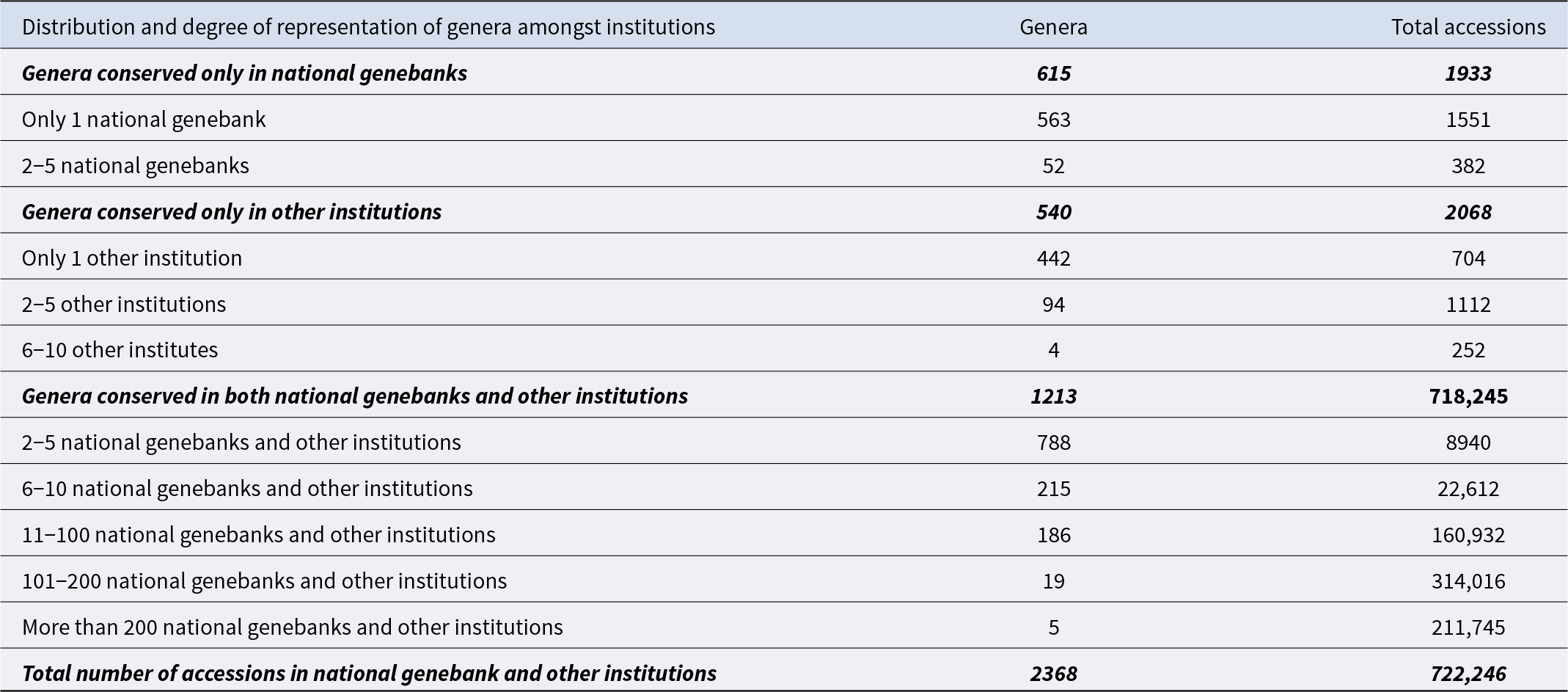

The distribution of the genera amongst the institutions in the global system was analysed further. We classified each genus for the number of institutions and type of institute (national genebank, global or both) where conserved. Table 2 gives the distribution of genera and accessions amongst the six classes for the degree of genera representation amongst institutions (number of genera and accessions conserved in 1, 2–5, 6–10, 11–100, 101–200 and more than 200 institutions) within solely national genebanks, solely other global institutions and both types of institutions within the global conservation system. Overall, 42% of the genera were only conserved in one national genebank or one other global institution. The number of genera conserved in two to five institutions was much higher amongst those managed by both types of collection holders. Specifically, 65% of the genera conserved in both types of institutes were conserved in two to five institutions. Overall, 95% of the genera in the global system were conserved by one to five institutions (national genebank, other institution and both), but these were represented by less than 2% of the total number of accessions. While there are 358 institutions within the global system that conserve accessions originating from the 20 countries, 73% of the total number of accessions conserved are from only 24 genera that were conserved in more than 100 institutions, ranging from 102 to 324 institutions.

Table 2. The degree of genera representation amongst institutions in the global system based upon the number of genera and total number of accessions conserved in 1, 2–5, 6–10, 11–100, 101–200 and more than 200 institutions only in the 20 selected national genebanks, only in global institutions, or in both

For the 24 genera that are conserved by more than 100 institutions in the global system, LAO018 conserved 10 of these that accounted for 95% of the accessions, while PER012 conserved 11 of the genera but this only accounted for 41% of the total number of accessions. Conversely, 75% of the genera conserved by KEN212 were only conserved in the national genebank and in two to five institutions in the global system but this only accounted for 9% of the accessions. Also, 56% of the genera conserved by GHA091 were only conserved in the national genebank and in two to five institutions in the global system but this accounted for only 4% of the accessions. For LBN020, 63% of the genera were only conserved in the national genebank and in two to five institutions in the global system but this accounted for 30% of the accessions.

Distribution of diversity by crop group

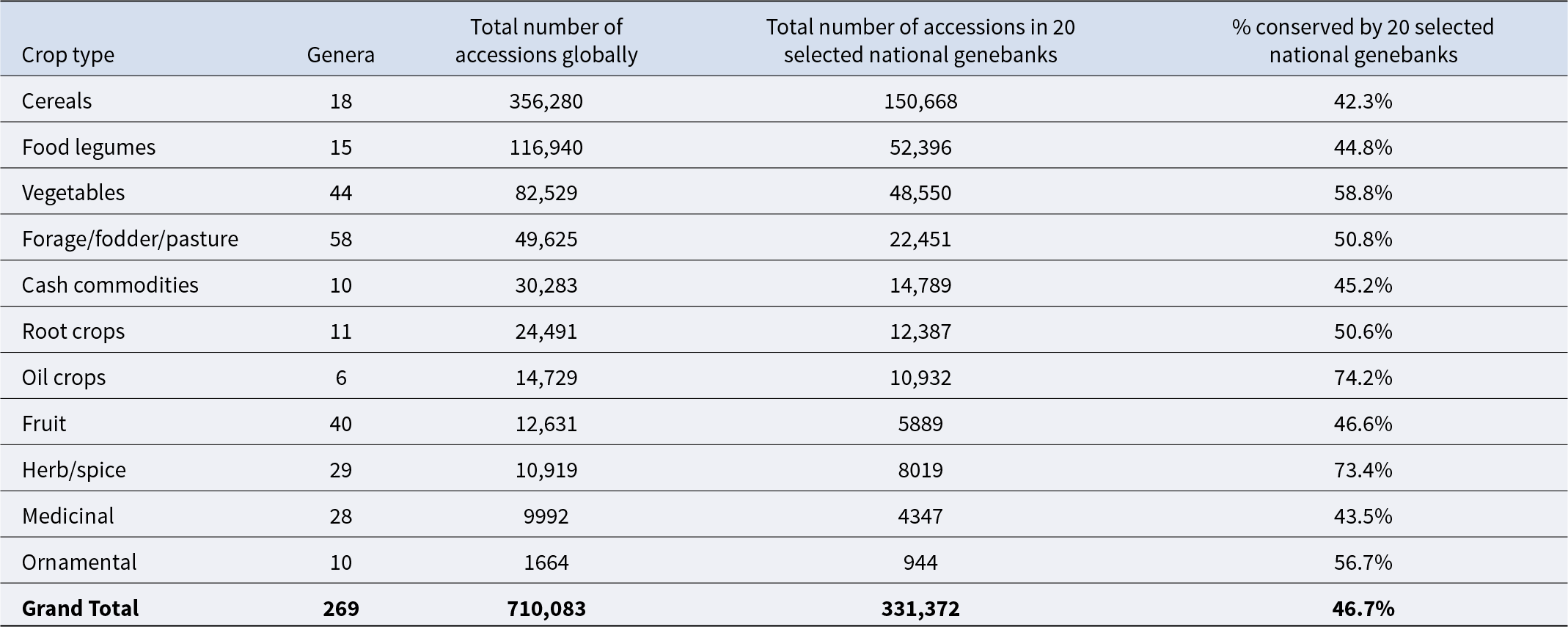

There were 269 genera that had more than 50 accessions conserved. These 269 genera account for 98.3% of the total accessions originating from the 20 countries that are conserved in the global system and 97.9% of the accessions conserved by the 20 selected national genebanks. We classified each of these genera into 11 crop types (Table 3). The number of genera in each crop type varied from 6 for oil crops to 58 for forage/fodder/pasture crops. About 50% of the top genera were forage/fodder/pasture, vegetables and fruit crops. Three-quarters of accessions conserved in the selected national genebanks and globally were cereals, food legumes and vegetables. For oil crops and herb/spice genera, about 75% of the accessions were conserved by the selected national genebanks. For the other crop types, the proportion conserved by the national genebanks ranged from 42 to 58%.

Table 3. The number of genera, the total number of accessions conserved globally, the number of accessions in the 20 selected national genebanks and the proportion of the global accessions that are conserved in the national genebanks for the top 269 genera classified into the 11 crop types for accessions that originated from the 20 countries

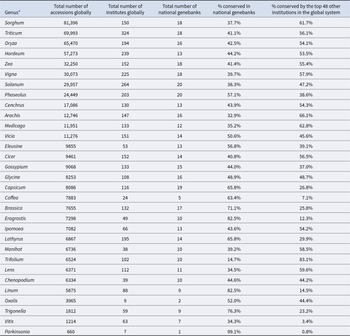

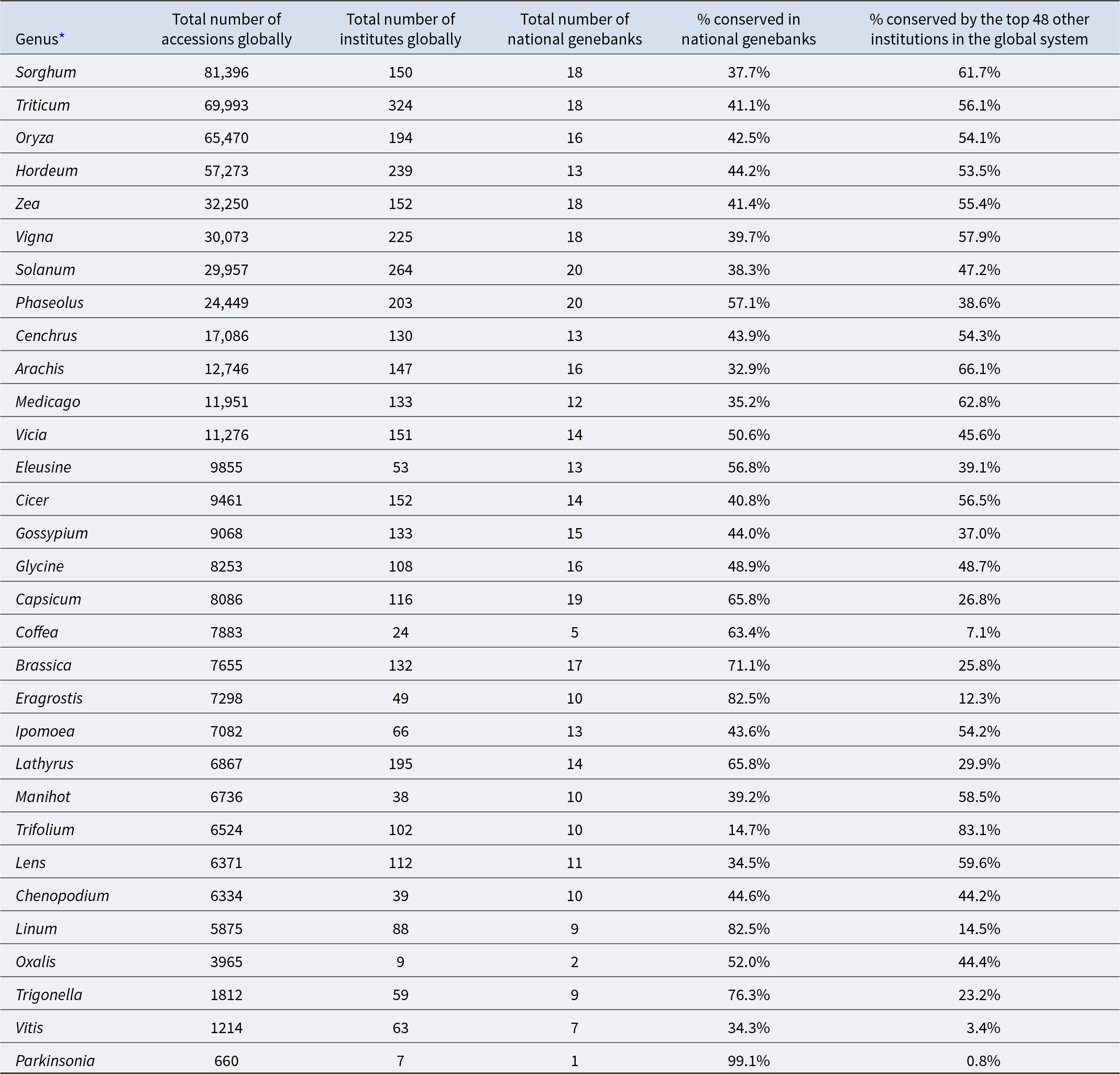

We identified the top 32 genera for the global total number of accessions originating from the 20 countries and classified these into 1 of the 11 crop types (Table 4). Twenty-six of the 32 genera are conserved in more than half of the selected national genebanks (Table 4). Parkinsonia, an ornamental crop, was conserved in only seven global institutions, including just one national genebank (YEM053). Oxalis, a medicinal crop, was conserved in nine global institutions with only two national genebanks (PER012 and ECU023). For 20 of the top genera, the number of institutions in the global system ranged from 102 to 324. Triticum was conserved by 324 genebanks in the global system while Hordeum, Solanum and Phaseolus were conserved in 225–264 institutions. The proportion of the accessions that were conserved by the selected national genebanks ranged from about 40% to 66% for the majority of the genera, except Sorghum, Solanum, Arachis, Medicago, Trifolium, Lens and Vitis. Four genera had more than 75% of the accessions conserved by the selected national genebanks: Parkinsonia, Linum, Eragrostis and Trigonella.

Table 4. The number of accessions conserved globally, the number of institutes where conserved globally, number of national genebanks where conserved, the percent of accessions conserved in the 20 national genebanks, and the percent of accessions conserved by the top 48 other institutions globally for the top 32 genera with accessions that originated from the 20 countries

* Ordered by the total number of accessions globally from largest to smallest.

Distribution by institutions in the global system

We also assessed the importance of the 48 other institutions in the global system that conserve the highest number of accessions that originated from the 20 countries. Table 4 presents the proportion of the total global accessions conserved by the 48 other institutions for each of the top genus. For most of the genera, the national genebanks and the top 48 institutions accounted for 90% or more of the global accessions. Twenty-two of the top institutions included 11 international genebanks and 1 regional genebank (ICRISAT [13 genera], ICARDA [64 genera], IRRI [3 genera], IITA [17 genera], CIMMYT [6 genera], CIP [11 genera], CIAT [77 genera], WorldVeg [47 genera], ICRAF [81 genera], ILRI [180 genera], AfricaRice [1 genus], and SPGRC in Zambia [31 genera]), 4 genebanks in the United States (USA016 [105 genera], USA029 [7 genera], USA022 [82 genera], and USA020 [87 genera]), 2 genebanks in Australia (AUS165 [60 genera] and AUS167 [101 genera]), 1 genebank in Germany (DEU146 [106 genera]), 1 genebank in Russia (RUS001 [59 genera]), 1 genebank in the United Kingdom (GBR004 [1237 genera]) and 1 genebank in India [IND001 25 genera]). These 22 institutions conserve 75% of the accessions that have originated from the 20 countries that are conserved by other institutions in the global system.

For three of the genera – Sorghum, Arachis and Medicago – the 48 other institutions in the global system conserved more than 60% of the accessions. ICRISAT conserves 21% of the total accessions for Sorghum and 34% of the total accessions for Arachis. For Coffea and Vitis, the global system includes a high proportion of institutions that do not conserve other genera or accessions from the 20 countries. For example, 19 other institutes conserve accessions of Coffea in the global system but only ECU330 is included in the top 48 institutes. For Trifolium, the top 48 institutions conserved more than five times as many accessions as the selected national genebanks. AUS167 and ILRI conserve about 42% of the total number of accessions.

Discussion

The 20 selected national genebanks are significant collection holders for the plant genetic resources originating from their respective countries, each of which is an important source of diversity globally. These genebanks conserve nearly half of the total number of accessions for three-quarters of the total genera. Although the degree and distribution of diversity differ amongst the national genebanks, each conserves only a portion of the accessions from its own country that exist in the global system, with representation ranging from less than one-quarter to nearly 90%.

Three national genebanks conserve less than 25% of the global accessions originating from their respective countries (NGA010, LBN020 and PER012). These three countries are hosts for three international genebanks (IITA in Nigeria, ICARDA in Lebanon, and CIP in Peru). In Nigeria and Lebanon, IITA and ICARDA conserve a higher proportion of the total global accession from those two countries than NGA01 or LBN020. This could account for the low proportion of the global accessions conserved by these two genebanks. This was not the case for PER012 where institutions outside CIP conserve a high proportion of the accessions that have originated from Peru.

The number of genera conserved ranged from 23 to 897 for the 20 selected national genebanks. These differences in the diversity of genera and number of accessions were expected given the differences in mandate, institutional arrangement and the history of acquisition. The 20 national genebanks were established from 1964 (GHA091) to 2013 (LBN010). Thirteen of the genebanks were established prior to 1996, while seven were established in the 2000s. A very small proportion of the accessions (less than 1%) from these 20 countries were collected prior to 1952 and only 538 of the oldest accessions (out of a global total of 7621 oldest accessions) were conserved by the 20 national genebanks. About 30% of the national accessions conserved globally were collected prior to 1995 and just over a third of these are conserved by the national genebanks. Thus, most of the accessions that originated from these 20 countries that are conserved nationally and globally are 30 years old or less.

The national genebanks conserve mainly wild/weedy species and traditional cultivars/landrace accessions but the proportions conserved by the individual collections in the global system differ across the collection holders. Conserving a high proportion of wild species or traditional landraces could be considered as an indicator for a genetically diverse collection, but there are no clear criteria to judge the ‘adequacy’ of conservation of the various biological types for collection holders. While it is possible to assess the proportion of wild/weedy accessions conserved, it is difficult to assess the degree of genetic diversity that is conserved within each of these wild/weedy accessions, given the unknown approach taken to sampling the populations during collecting and during any regeneration. Limited regeneration of the wild species could also result in limited opportunities to assess the within accession diversity. The low number of accessions conserved and the unknown nature of the within-accession diversity could indicate a gap in conservation of local wild or weedy species by most of these national genebanks but could also be due to a gap in data for at least four of the genebanks.

The difference found in this study of the 20 national genebanks could be influenced by the specific mandate or objective for conservation for the institute, or it could be the result of the opportunities the institution had in the past to collect or acquire certain biological types, such as sampling from populations of the wild species from natural areas or traditional landrace varieties from remote rural areas. One assumption could be that institutions with a clear mandate for conservation of agricultural crop genetic resources conserve a collection with a narrow focus on fewer genera and fewer wild/weedy or landrace accessions. This was not evident from the national genebanks in the study.

Four of the 20 national genebanks are institutes or programmes within institutes that have a broad mandate for biodiversity conservation and are not necessarily part of the national agricultural research organizations. For example, ETH015 and BTN026 were initiated with legal acts or laws that recognized the need to protect biodiversity in the country. NGA010 is part of the Ministry of Science. TNZ016 is a programme in the Tanzania Plant Health and Pesticide Authority. Overall, the status of the institution within national agricultural research institutions or its conservation mandate did not influence the number of genera conserved nor the proportion of the accessions conserved that are classified as wild/weedy or traditional cultivars/landraces. It was clear that there were significant gaps in relation to the representation of the wild and weedy species across all the national genebanks and, in some of the countries, for traditional cultivars/landraces.

The study found that the selected national genebanks and the other institutions in the global system conserve a large number of genera, but only a limited number of these genera have a high degree of representation based on the number of accessions conserved. It was not possible in this study to further analyse the relationship between specific accessions within genera that are conserved by multiple institutions. It is likely that some of these accessions are highly duplicated across institutes, while others are unique, but this cannot be determined without further study. Notably, many of the genera most widely conserved across multiple genebanks correspond to the crops listed in Annex I of the ITPGRFA, which have been identified for their global importance for food and agriculture. This alignment helps explain why certain major food-crop genera appear across numerous institutions, reflecting their prioritization in global conservation efforts.

This study at the genus level does not differentiate the number of accessions within species separately, but it can be assumed that for the majority of genera with a small number of accessions from numerous species, the differentiation of accessions to species would not impact the results. For the genera with more than 100 accessions, the differentiation to the species-level could reduce the number of genera with a higher degree of representation. To explore this further, an assessment was done of the species-level differences in Sorghum, Triticum, Vigna, Solanum, Medicago, Coffea, Manihot, Linum and Parkinsonia. The number of species ranged from 1 for Parkinsonia, 3 for Manihot, 7 for Sorghum and Coffea, 9 for Linum, 34 for Triticum, 48 for Vigna, 55 for Medicago and 265 for Solanum. For four of the genera, one species accounts for 99% of the accessions (Sorghum bicolor, Linum usitatissimum, Manihot esculenta and Parkinsonia aculeata). For Coffea, two species accounted for 99% of the accessions (C. arabica [92%] and C. canephora [7%]). Within the Triticum genus, 3 species out of the 34 account for 96% of the accessions (T. aestivum [56%], T. turgidum [32%] and T. aethiopicum [8%]). For Vigna, there were 5 species out of the 48 that had more than 500 accessions originating from the 20 countries that are conserved globally and accounts for 93% of the accessions (V. unguiculata [59%], V. radiata [15%], V. subterranea (11%), V. mungo [4%] and V. umbellata [4%]). For Medicago, 4 species out of 55 have more than 1,000 accessions but only account for 59% of the total accessions in the genus (M. truncatula [20%], M. polymorpha [15%], M. sativa [13%] and M. doliata [11%]). Solanum had 3 species out of 265 that accounted for 58% of the total accessions that originated from the 20 countries (S. tuberosum [30%], S. lycopersicum [20%] and S. melongena [8%]). Within Solanum, there were only 47 species with more than 50 accessions while 158 species had less than 10 accessions. From the example of these nine genera, it is clear that the differentiation of genus to species level results in the identification of a much higher proportion (77%) of crops or wild species that originated from the 20 countries that are underrepresented across the institutions in the global system. Despite this limitation, the results indicate that many of the national and locally important genera, species and populations for local grains, legumes, oil crops, vegetables, fruits, herbs, spices, medicinal plants, crop wild relatives or wild species are poorly represented in the selected national genebanks or in the global system.

While there are almost 50 other institutions that conserve significant number of accessions overall from the 20 countries, the distribution of accessions across genera in the top institutions is very specific, depending upon the history of acquisition and objectives for the institute. Thirteen of the cereal crop genera and 11 of the food legume genera are a focus for conservation for 6 of the international genebanks. Given the history of collecting by these international genebanks in these countries, this could have resulted in more comprehensive collections for these genera at these institutions rather than in the national genebanks. There does not seem to be any clear evidence of this. For example, with Sorghum, ICRISAT conserves 20.1% of the accession originating from the 20 countries, while two other institutions (USA016 and IND001) conserve 25% of the accessions. For Triticum, ICARDA and CIMMYT conserve 23.7% of the accessions, while two other institutions (USA029 and AUS165) conserve another 20%. A similar situation was found for an oil crop genus that is not conserved by an international genebank, Linum, where three other institutions conserve 12.2% of all the accessions. Thus, for many of the top genera, the national genebanks, international genebanks and a few other institutions conserved most of the accessions.

The distribution of the genera amongst and within the global system demonstrated that assessing the total number of accessions or genera conserved globally does not necessarily indicate the degree of diversity being conserved. Further characterization of the diversity conserved in relation to the number of accessions per genus, the number of crop types conserved and the degree of alignment of the composition with the crop, genus or species level priorities for conservation and use in the country could better describe the adequacy of ex situ collections to meet the future challenges for users. This study was not able to clearly identify alternative indicators for representation or diversity that could be used to monitor the adequacy of ex situ conservation for the longer term but this needs to be considered for the future.

In the past, acquisition for most genebanks has been opportunistic rather than strategic or driven by clearly identified priorities. There are clear gaps in the collections in relation to underrepresented crops, forages, fruit trees, vegetables, medicinal plants and wild species. Many genebanks plan collecting missions each year when funds are available but not always based on strategic longer-term assessments of the gaps in the current crop collections, nor considering duplication in the global system. Many genebanks identify gaps based more on expert advice rather than a formal gap analysis. While some of the genebanks in the study have also used local consultative processes to identify crops and varieties for collections, their assessments have primarily relied on the local knowledge of diversity and threats to the diversity still maintained in the field. It should also consider the diversity extant in the on-farm versus the sample of diversity conserved in the genebank. However, applying a more formal gap analysis offers an opportunity to use data compiled from all national and global sources of genebank collections, flora and herbarium, PGR distribution data, environmental data, climate change projections and other data to identify the priority crops and target areas for future collection.

The importance of collections held by national genebanks and by the global system will increase but genebanks will need to ensure the composition of the collections meets future demands by users. The development of a clear, prioritized acquisition strategy for the next 10–20 years should be done for each crop in consultation with representatives of the key users for the future, including researchers, the private sector, NGOs, local communities and smallholder farmers from the various agricultural environments. It should consider the important role a collection will need to take in the future development of agriculture and in the reduction of the risk of loss from climate change. It should consider the value of an increased sampling of within-species diversity. It should consider future needs to conserve native wild species, including crop wild relatives, in ex situ conservation as safety duplications for the populations that are being conserved in secure in situ protected sites. Finally, it should consider the key role of other institutions in the global ex situ conservation system to ensure the long-term conservation and use of genetic resources of national origin. This will require greater assessment of duplication, gaps, and priorities for the future in close collaboration with others. The study reported here did not assess the collaboration of the 20 selected national genebanks with others in the global system, but this is an important area for further study to determine the effective functioning of the global system.

Conclusion

This study assessed the distribution and degree of representation of crop diversity originating from the 20 countries, evaluating the genera and accessions conserved nationally and globally, the relative importance of the crops, and the extent to which other institutions also conserve this material. Generally, we found evidence of an insecure national and global conservation system with three quarters of genera represented by fewer than 10 accessions conserved in only one to five institutions. The diversity represented in the global system that have originated from the 20 countries mainly consist of accessions from 159 genera (out of total of 2368 genera) conserved by the 20 selected national genebanks and 48 other institutions globally. These 159 genera account for 96% of the accessions conserved in the global system.

The focus for conservation in the global system is a limited number of global cereals, food legumes, vegetables and forage/fodder/pasture crops. There is very limited representation of the genetic diversity for crops that have more national or local importance, even within the selected national genebanks. There is also limited representation amongst multiple institutions for most of these genera. This indicates significant gaps in the collective composition of the global system for the majority of genera with unique diversity at the national and local levels in the 20 countries.

The study highlights the need to carefully reconsider the composition of collections by collection holders in the global system, individually and collectively, especially given the significant costs and limited resources available for long-term ex situ conservation. The initial focus for rationalization should be the small number of genera with large number of accessions conserved globally. The focus for gap filling needs to be on the wild species and traditional cultivars/landraces of crops that are of significance locally and nationally. The BOLD and SFR projects have utilized the recommendations from the genebank reviews of the 20 national genebanks to allocate resources to enhance the composition of their collections. These efforts have included targeted capacity building in gap analysis and related areas of collection management to strengthen capacity and support more strategic curation, but sustained commitment to coordinated, evidence-based collection management will be essential to ensure that ex situ conservation systems remain resilient, efficient, and fit for future needs. A follow-up study to assess the collaboration of the 20 selected national genebanks with others in the global system could offer evidence for an effective model for collaboration focused on collection composition management within the global system.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1479262125100464.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the staff of partner genebanks for providing the background data used in this study and for their support during the review process. The authors also thank the Crop Trust for supporting this work through the BOLD project (https://bold.croptrust.org/), funded by the Government of Norway (grant number: QZA-20/0154), as well as the SFR project (https://www.croptrust.org/work/projects/seeds-for-resilience/), funded by the German Development Bank (KfW). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Crop Trust.