Introduction

Russia's invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, had a marked impact on the way European countries and their allies approach international security. In the immediate aftermath of the invasion, a new, shared sense of the Russian threat led to prospects unimaginable just a few months earlier – including Finland's and Sweden's applications to join NATO, Denmark joining the European Union's (EU) Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), the first ever EU funding of lethal weapons, the prospect of a modernized, more assertive German army and the EU's rapid agreement on tough sanctions against Russia. Similarly, polls showed that European publics responded with greater perceptions of the Russian threat, greater determination to abide by alliances and a greater willingness to consider even radical policy proposals such as the introduction of a European army (Smith, Reference Smith2022aReference Smith, b).

These responses are broadly consistent with the predictions of the external threat hypothesis, according to which threat from outside a given group increases unity and cooperation within this group (Holsti et al., Reference Holsti, Hopmann and Sullivan1973; Kaplan, Reference Kaplan1957; Myrick, Reference Myrick2021). But they also raise questions about the relationship between threat perceptions and international cooperation in general. Given the largely unified US and EU response to the extraordinary event of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, we must not forget that even immediately prior to the invasion, even within Western Europe, there were quite fundamental differences in preferred policies toward Russia (e.g., Wintour, Reference Wintour2022). Beyond the specific problem of agreeing on a joint Russia policy, there had been persistent fundamental disagreements on European security and defence integration more generally (Hofmann, Reference Hofmann2013), and political entrepreneurs had begun to politicize the issue (Angelucci & Isernia, Reference Angelucci and Isernia2020; De Vries et al., Reference De Vries, Hobolt and Walter2021). In such a context, are threat perceptions a force for unity?

This paper contributes to answering this question by analysing whether perceptions of international threats to national security are associated with support for further EU security and defence integration. Against the background of the external threat hypothesis, such an association seems extremely plausible, but at second glance things turn out to be more complicated. We suggest that at least two different competing mechanisms are important to consider. First, a variant of the external threat hypothesis could play a role. Citizens might come to believe that threats that exist beyond the EU's borders necessitate the expansion of European defence policy because their own country is not capable of countering these threats on its own. Many experts see precisely this as a way to increase the old continent's influence in the world (e.g., Howorth, Reference Howorth2017). Second, in line with post‐functionalism (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009), it could also be that threat perceptions increase the importance of social identities for opinion formation and lead to a polarising effect. It is well established that external threat increases ingroup cooperation (Schaub, Reference Schaub2017; Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979), and that Europeans identify with different territorially defined (in‐)groups (e.g., Bergbauer, Reference Bergbauer2018; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009). Increased threat perceptions could therefore (further) increase support for European security and defence integration among citizens who identify with Europe, whereas individuals who identify exclusively with the nation might become (even) less inclined to support the delegation of core powers from their ingroup to an outgroup.

Given these competing theoretical accounts of how threat perceptions are associated with support for European integration, we use survey data collected in October 2020 from 25 countries (n = 40,500) to ascertain whether either claim has stronger empirical support. Given that our evidence stems from cross‐sectional data analysis, the usual caveats regarding causal interpretation apply. Nonetheless, our results allow some tentative conclusions about the nature of this association and whether perceptions of threat polarise or unite public opinion in this particular policy domain at the public level.

Our main finding is that perception of greater international threat is associated with an increased willingness for European‐level cooperation in the security and defence domain. This association is present in virtually all countries and, importantly, just as pronounced among citizens with an exclusive national identity as among those with inclusive identities. Further analyses show that this also applies more generally to EU opponents and EU supporters. While Eurosceptics are generally opposed to EU agency, they become increasingly favourable of more integration as their level of perceived threat increases. In contrast, Europhiles are supportive of such a policy irrespective of their threat perception. This pattern fits with an interpretation of attitude formation where citizens react to perceived problem pressures with an increased taste for European integration. In other words, security concerns can trump a post‐functionalist logic of attitude formation – at least temporarily. This insight also shows that general Euroscepticism might not necessarily be an obstacle to support specific steps towards integration.

Threat perception and public support for European security and defence integration – Functionalist versus post‐functionalist perspectives

Crises and uncertainties are recurring phenomena both on the international and domestic levels. They can impact people's threat perception which, in turn, may influence their preferred level of international cooperation. Brexit, COVID‐19 and most recently, Russia's invasion of Ukraine are just a few examples that have led scholars and pundits to increase their analytical attention to international organisations and the EU's (dis)integration (Jones, Reference Jones2018; Zielonka, Reference Zielonka2014).

We understand threat perception broadly as the belief that something, someone or some group challenges national goal attainment or well‐being, that is, as the psychological state of anticipating harm (Baldwin, Reference Baldwin1971; Riek et al., Reference Riek, Mania and Gaertner2006). Only a few studies have addressed the implications of perceptions of external threat on public opinion in the context of European integration (Graf, Reference Graf2020; Gehring Reference Gehring2022), but several relevant strands of literature examine the relationship between external threat perceptions and support for cooperation. A widely discussed idea is the external threat hypothesis, which posits that external threat increases cooperation within groups of individuals and states (Holsti et al., Reference Holsti, Hopmann and Sullivan1973; Kaplan, Reference Kaplan1957; Myrick, Reference Myrick2021). There are different potential mechanisms that could drive such an effect, and we argue that in the context of European integration, they imply opposing expectations.

One perspective, which we will call ‘functionalist’, posits that international threats create (perceived) integration pressures. With this theoretical lens, perceptions of international threat should be associated with support for integration. Importantly, this relationship should hold regardless of one's attitudes towards the EU. An opposing perspective, which we call ‘post‐functionalist’, argues that the perception of threat activates group orientations and attitudes that colour citizens’ evaluations of the more specific question of security and defence integration. According to this perspective, threat perceptions should lead to a differential pattern, namely a positive association between the level of perceived threat and support for integration among those with positive views towards the EU and a negative association among those with negative opinions towards the EU.

Before describing these two theoretical perspectives, we note that the relationship between threat perceptions and cooperation preferences can be affected by other factors. General value orientations may shape both what people perceive as threatening (for desired end states) and their support for policies (because they may or may not be deemed instrumental to realising these end states). To rationalise their policy preferences, individuals may choose to perceive a matching level of international threat. Building on previous research, however, we do not expect such endogeneity problems to be particularly relevant in this case. Existing research on attitudes toward European security and defence integration (Brummer, Reference Brummer2007; Peters, Reference Peters2014; Sinnott, Reference Sinnott2000) shows that they typically occupy a rather marginal position in mass belief systems. It seems unlikely that notable segments of the population have such strong attitudes toward this issue that they would be motivated to rationalize them with corresponding assessments of the international threat situation.

The functionalist perspective

International relations and EU integration scholars have made the argument that more cooperation and integration occur when internal and external pressures make it more efficient and/or effective. All ‘grand theories’ of European integration (neofunctionalism, intergovernmentalism, post‐functionalism) share the idea that a mismatch between efficiency and the existing structure of authority triggers regional integration (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009, 2). Accordingly, the process of European integration can be interpreted as driven by functional pressures arising from the devastating experiences of World War II, threats to national security and economic interdependence that have overridden barriers of cooperation (Haas, Reference Haas1975; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009; Lindberg & Scheingold Reference Lindberg and Scheingold1970; Moravcsik, Reference Moravcsik1993).

Granted, states have been anxious to lose control over the ‘high politics’ of security and defence (Hoffmann, Reference Hoffmann1966), making this domain one of the least integrated policy areas of the EU (Börzel, Reference Börzel2005; Hofmann, Reference Hofmann2013; Rittberger et al., Reference Rittberger, Leuffen, Schimmelfennig, Genschel and Jachtenfuchs2013). The general logic of functional pressures, however, should apply to the security and defence domain as well – in particular in times when the United States is increasingly unwilling and unable to provide for Europe's security (Jones, Reference Jones2007; Rosato, Reference Rosato2010). Accordingly, when there is sufficient concern about European security, there should be concomitant demand for EU integration in security and defence matters. This argument aligns with many rational choice and realist security studies scholars, who argue that external threats push states to build and sustain military alliances (Johnson, Reference Johnson2017; Walt, Reference Walt1987).

On the individual level, an extensive psychological literature views threat perceptions as a causal stimulus that influences human emotion, thought and action (e.g., Blanchard et al., Reference Blanchard, Griebel, Pobbe and Blanchard2011; Donahue, Reference Donahue, Zeigler‐Hill and Shackelford2020; Marcus et al., Reference Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2000). The functionalist perspective implies that threat perceptions create the motivation to remove the threat. Accordingly, when threat is present, people will evaluate the usefulness of available measures to remove that threat; following subjective utility maximisation, people should favour measures they deem useful and reject those that are not useful (Brandt & Bakker, Reference Brandt and Bakker2022). The crucial question for the present research is whether people consider European integration in the security and defence domain to be an effective tool against international threats. Many scholars working on European security and defence policy integration (implicitly) argue that more integration would increase the capability of the continent to address large‐scale international challenges (e.g., Howorth, Reference Howorth2017; Jones, Reference Jones2007; Smith, Reference Smith2017) and move Europe towards realising its ‘potential superpower’ status (Meunier & Vachudova, Reference Meunier and Vachudova2018). In the face of external threat, citizen thinking might run along these lines. Citizens may perceive a mismatch between the scale of the security challenges and the political authority structures in place to address them, and come to the conclusion that more collective defence is needed to handle the threat.

There are several complementing arguments that make the functionalist perspective psychologically plausible, even taking into account low levels of detailed knowledge the public may have in this domain. High‐cost situations (defined by high threat) induce ‘System 2’ reasoning (Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2011) that privileges accuracy goals and systematic reasoning. In contrast, low‐cost situations (defined by low threat) induce ‘System 1’ reasoning that relies on directional goals and speedy heuristic reasoning.Footnote 1 Similarly, the affective intelligence literature (Marcus et al., Reference Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2000) argues that perceived threat may increase attention and trigger more careful, instrumental reasoning. Other research shows that threat perceptions may activate accuracy goals in information processing and reasoning (Huddy et al., Reference Huddy, Feldman, Taber and Lahav2005; Lodge & Taber, Reference Lodge, Taber, Lupia, McCubbins and Popkin2000), and the perceptions that the stakes are high increase the relevance of instrumental considerations (Diekmann & Preisendörfer, Reference Diekmann and Preisendörfer2003; Lodge & Taber, Reference Lodge, Taber, Lupia, McCubbins and Popkin2000). In sum, these findings suggest that perceiving high levels of international threat may induce a form of effortful processing that leads to seeing European security and defence integration as valuable – even among those who are not favourably disposed to the EU.

Functionalist hypothesis (H1): Individuals who perceive higher levels of threat will be more likely to support European defence and security integration, regardless of whether they are Europhiles or Eurosceptics.

The post‐functionalist perspective

According to the post‐functionalist perspective, preferences about regional integration are not only the product of cost‐benefit reasoning but also hinge on the exclusiveness of territorial identities and their contestation (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009). Accordingly, (politicised) group identifications may disrupt functional pressures towards integration. Eurosceptic parties have increasingly portrayed European integration as undermining or threatening national identity, turning it into a highly symbolic issue (De Vries, Reference De Vries2018). As a result, ‘citizens who conceive of their national identity as exclusive of other territorial identities are likely to be considerably more Eurosceptical than those who conceive of their national identity in inclusive terms’ (Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2004, 416). Empirical studies indeed show that individuals who identify exclusively with the nation tend to be Eurosceptic, while support for European integration is higher among those who identify with both the nation and Europe or Europe only (e.g., Clark & Rohrschneider, Reference Clark and Rohrschneider2019; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2004; McLaren, Reference McLaren2007; Risse, Reference Risse2010).Footnote 2

Psychological research on intergroup relations suggests that external threat may exacerbate these tendencies. Perceived threats lead to feelings of distrust, hostility and intolerance towards the outgroup's members (Conrad et al., Reference Conrad, Croco, Gomez and Moore2018; Merolla & Zechmeister, Reference Merolla and Zechmeister2009; Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Piereson and Marcus1982), favouritism towards the ingroup (Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979) and an increased willingness to cooperate with ingroup members (Schaub, Reference Schaub2017) – though these effects may be conditional on individual‐level characteristics including personality, values and political attitudes (Hetherington & Suhay, Reference Hetherington and Suhay2011; Marcus et al., Reference Marcus, Theiss‐Morse, Sullivan and Wood1995).

By way of theoretical synthesis, we advance on prior work by examining how threat perceptions are linked to the willingness to cooperate in the multilevel system of the EU. As discussed above, prior work stresses that external threat increases ingroup cooperation. Due to the multilevel system of the EU, people may view different groups as the relevant ingroup. People who identify with both nation and Europe may desire increased EU cooperation because European institutions are squarely in their ingroup. People with an exclusive national identity, in contrast, may show an increased opposition to integration because they believe that increased cooperation with European outgroups – which might necessitate compromises and induce costs – is counterproductive to increased defence efforts at the national level. This expectation is consistent with terror management theory (Pyszczynski et al., Reference Pyszczynski, Solomon and Greenberg2015), which posits that people cope with existential threat by adhering to worldviews set by larger cultural structures (e.g., one's nation or religion) to restore a sense of security and boost self‐esteem. In this account, the importance of territorial identities in guiding citizens’ reasoning about European defence integration should increase the more they see the international environment as threatening.

Post‐functionalist hypothesis (H2): Individuals who perceive higher levels of threat are more likely to support European defence and security integration if they identify with Europe and less likely if they identify exclusively with their nation.

The role of political sophistication

We also examine the extent to which political sophistication moderates the effect of threat perceptions on support for European security and defence integration. The functionalist perspective puts high expectations on the cognitive capabilities of average citizens to evaluate the usefulness of the EU's security and defence policy. Even if the perception of threat motivates people to think about the issue in an impartial way, they may be incapable of thinking through the implications of global and regional security challenges. Indeed, dual‐process models of attitude formation and decision‐making point out that both motivation and capabilities are necessary to employ systematic processing (e.g., Fazio, Reference Fazio1990). Other studies suggest that partisan disagreement over policy‐relevant facts is often greatest among opposing partisans who are the most cognitively sophisticated (e.g., Drummond & Fischhoff, Reference Drummond and Fischhoff2017; Malka et al., Reference Malka, Krosnick and Langer2009).

Existing theoretical perspectives hence imply rivalling expectations about the impact of political sophistication. People who perceive high levels of international threat but lack sufficient knowledge may not be able to evaluate whether European integration in the security and defence domain would be effective in addressing such challenges. Positive associations between threat perceptions and support for integration would then only be present among citizens with high levels of political sophistication. This would limit the pattern implied by the functionalist view (H1) to political sophisticates. Citizens with low levels of political sophistication, in contrast, could (be forced to) rely exclusively on political predispositions to evaluate this policy, generating the polarisation implied by the post‐functionalist view (H2) in this subgroup. Alternatively, political sophistication could amplify polarisation effects triggered by the post‐functionalist logic described above. This would create a pattern corresponding to the post‐functionalist view only among political sophisticates. Low sophisticates, in this reading, might lack the ability of reasoning along ideological lines. Since we have no way of empirically isolating these different underlying mechanisms, we refrain from posing formal hypotheses on this secondary issue. It is nonetheless important to empirically explore the extent to which the association between threat perceptions and support for European security and defence integration varies with political sophistication because it speaks to the question of how widespread the patterns implied by the functionalist and post‐functionalist perspectives are, respectively. We hence propose the following research question:

Sophistication research question: How does political sophistication influence the association between threat perceptions and the preference for increased European defence and security integration?

Data, measures and methods

To test our hypotheses and answer the research question, we analyse data from an October 2020 online survey conducted in 24 EU member states and the UK (n = 40,500).Footnote 3 It was fielded by the survey firm IPSOS using nation‐specific online panels with representative quotas set for gender, age, education and region. Our primary outcome measure asks, ‘how integrated would you like countries in the EU to be when it comes to defence and security matters?’ with responses on a six‐point scale ranging from ‘Not at all integrated’ to ‘Extremely integrated’ as well as a ‘Don't know’ option. Only nine per cent of respondents chose the ‘Don't know’ option when answering this item, suggesting that after several decades of European integration the public is sufficiently familiar with the concept of integration to have a view on the matter.

Other items asking about similarly complex policy issues show comparable levels of ‘Don't know’ responses. For example, the question about whether the EU should acquire ‘joint military equipment such as transport or fighter aircraft’ also received nine per cent ‘Don't know’ responses.

Our primary explanatory variable is an additive scale from a five‐item battery asking respondents the level of threat that comes from five different sources: ‘terrorist attacks in [country]’, ‘cyber‐attacks on [country]’s computer networks’, ‘hostile states influencing [country]’s elections’, ‘Russia's territorial ambitions’ and ‘China turning into a world power’. Respondents answered on a 7‐point scale ranging from ‘No threat at all’ to ‘Critical threat’. These items were chosen as core threats facing Europe today that feature prominently in security and defence discourses (Dennison et al., Reference Dennison, Franke and Zerka2020). They were asked before the dependent variable to minimize the risk that the answers are rationalisations of the position on European security and defence integration. Our choice of an additive scale – which does not differentiate between types of threats – is theoretically appropriate given our focus on the degree that citizens perceive international threat generally. We examined whether results using this broad index are driven by individual types of threats. Factor analyses of the threat items reveal that threat perceptions in most countries form two highly correlated subdimensions, one capturing classic, state‐related threats (Russia, China), the other new, asymmetric threats (terrorist attacks, cyber‐attacks, election meddling). As detailed below, we replicated the analysis of the link between threat perceptions and support for European security and defence integration using the two subdimensions. The results are substantively the same for all threat measures.

To test the post‐functionalist hypothesis, we follow prior research and construct a measure of respondents’ identity configurations. It contrasts respondents who conceive of their national identity as exclusive of other territorial identities with those whose identity is more inclusive because they also identify with Europe (e.g., Clark & Rohrschneider, Reference Clark and Rohrschneider2019; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2004; Sinnott, Reference Sinnott2006). We use items asking respondents to indicate their attachment to the nation and Europe on a 7‐point scale (1 ‘Not at all attached’ – 7 ‘Extremely attached’) to construct these two identity configurations. Responses were dichotomized above the scale midpoint and respondents were classified as having an exclusive national identity if they felt attached to the nation but not to Europe, and as having an inclusive identity if they scored above the scale midpoint on the item measuring attachment to Europe. The latter category therefore includes both ‘inclusive nationalists’ and ‘Europeanists’ (Risse, Reference Risse2010).Footnote 4 The remaining respondents score at or below the mean of the two affiliation scales and are coded into an additional category that is included in the analysis but not interpreted because it is not relevant to our hypotheses and research question.Footnote 5

Political sophistication is measured using the answers to four factual political knowledge questions about the EU. Previous research has shown that effects of general value orientations and other basic dispositions on more concrete political perceptions and attitudes are mediated via domain‐specific postures (Goren et al., Reference Goren, Schoen, Reifler, Scotto and Chittick2016; Hurwitz & Peffley, Reference Hurwitz and Peffley1987; Rathbun et al., Reference Rathbun, Kertzer, Reifler, Goren and Scotto2016). Additional controls include three core foreign attitude postures (cf. Gravelle et al., Reference Gravelle, Reifler and Scotto2017; Rathbun et al., Reference Rathbun, Kertzer, Reifler, Goren and Scotto2016) that broadly capture militant internationalism, cooperative internationalism and isolationism. We also include controls for age, gender and education. Full wording is available in the Supporting Information Appendix A1. To facilitate the interpretation of the results of the regression analysis, all variables were rescaled to range from 0 to 1.

Analytic strategy

The core of the following empirical analysis is a series of regression models. Model 1 establishes prima facie evidence whether threat perception and support for integration are related. Correspondingly, the model includes threat perceptions as the main independent variable of interest and relevant controls, including the exclusive/inclusive identity measure. Model 2 adds an interaction term between threat perceptions and identity which allows us to adjudicate between the competing functionalist and post‐functionalist hypotheses.

The strongest support for the functionalist hypothesis would be if the marginal effect of the Threat variable was positive (and statistically significant) irrespective of respondents’ identity configurations (capturing whether they have an Exclusive national identity or one of the two Inclusive identities). Given potential ceiling effects on the level of support for European defence that individuals with inclusive identities can report, one might also expect a pattern where the effect of the Threat variable is larger among those with Exclusive national identity than those with an Inclusive identity. In this scenario, opponents converge on supporters ‘from below’ as perceived threat increases.

The strongest support for the post‐functionalist hypothesis would be if the coefficient of the Threat variable differed depending on whether individuals have an Exclusive national identity or an Inclusive identity. Specifically, it would be positive (and statistically significant) among the latter and either zero (and non‐significant) or negative (and statistically significant) among the former. With respect to the research question about the role of political sophistication, we estimate Model 3, which includes a three‐way interaction between the Threat, EU attitude, and Political sophistication variables. Calculating conditional effects of the Threat variable for different subgroups, we explore for example whether political sophistication is a prerequisite for the realisation that increased European defence might be a good idea in the face of international threats – that is, whether only respondents (irrespective of identity configuration) scoring high on the Political sophistication variable exhibit increasing support for European defence as they perceive higher threat. The pattern to look for in this case would be positive (and statistically significant) estimated effects of the Threat variable among respondents with high Political sophistication scores (irrespective of identity configuration), whereas such positive effects of the threat variable would be absent among those with low Political sophistication scores (irrespective of identity configuration).

To address the rivalling functionalist and post‐functionalist hypotheses, we estimate Models 1 and 2 at the pooled, European level as well as at the country level. Doing so, accounts for our main interest in inter‐individual patterns of association but at the same time is maximally transparent about potential inter‐country variation in association patterns. We refrain from reporting country‐by‐country results for the role of political sophistication (Model 3) here as the high sample‐size requirements for estimating three‐way interaction effects reliably (Dawson & Richter, Reference Dawson and Richter2006) are not met in this case.

Note that we have not proposed hypotheses with respect to country differences in attitude patterns. It would not be surprising to find contextual variation in the way people think about EU integration and the degree to which threat perceptions matter in this process.Footnote 6 But comparative theories, applicable across the 25 countries we examine, are weak at best, and more importantly, the characterisation of the boundary conditions difficult. Instead, we treat the fact that we have data from a wide‐array of countries as an opportunity to explore how robust individual‐level patterns are across contexts. The more consistent they are, the more relevant these findings and the less pressing the exploration of potential macro‐micro interactions.

Results

Descriptive statistics

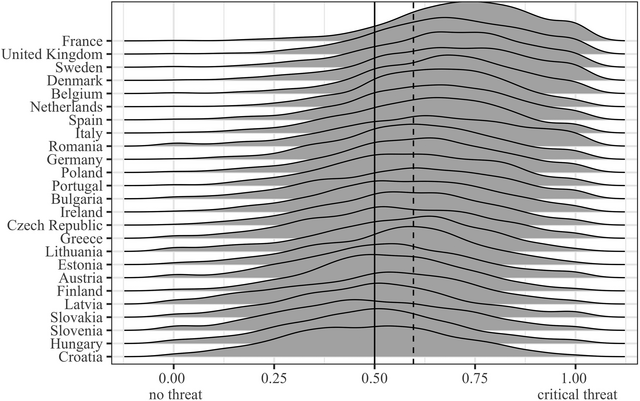

Figure 1 shows there is considerable individual‐level variation in perceived international threat in the 25 countries of our study. Of course, the cross‐sectional nature of the data means we cannot make comparisons over time. An implication of this limitation is that cross‐national comparisons may be influenced by local influences that are potentially ephemeral. For example, our French sample has the highest perceived threat average. Our data cannot separate whether perceived threat in France is always higher, or whether terrorist attacks in France that occurred slightly before fielding (Willsher, Reference Willsher2020) caused a short‐term boost in threat perceptions or some combination of both. Importantly, if such potentially short‐term forces do have an effect on threat perceptions, it suggests early support for the ‘functionalist’ position. Increases in (perceived) threat may reduce differences in support for European integration between EU supporters and opponents, in a depolarising manner similar to that found by Hetherington and Weiler (Reference Hetherington and Weiler2009).

Figure 1. Distribution of perceived international threats. Note: Reported are univariate frequencies from the additive threat index. Coding is 0–1 with higher values indicating higher threat perception. Dashed line indicates the European mean.

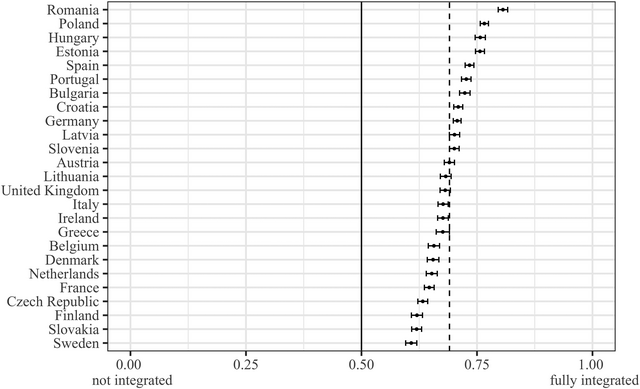

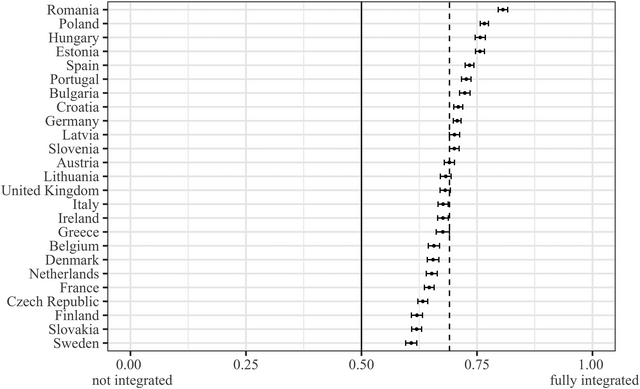

Figure 2 presents the mean level of support for European security and defence integration for each country, with the countries now ranked from highest to lowest in terms of integration support. In central, eastern and southern Europe, we find the highest levels of support for security and defence integration. In Western Europe, the countries that were neutral at the time (Ireland, Austria, Finland and Sweden), Denmark (not yet part of the CSDP) and Great Britain show on average slightly lower support for CSDP, yet still view this policy positively on average. The public appears open to further integration in this domain, which is consistent with prior findings (e.g., Mader et al., Reference Mader, Olmastroni and Isernia2020).

Figure 2. Distribution of attitudes towards European security and defence integration. Note: Reported are univariate frequencies. Coding is 0–1 with higher values indicating higher support for European security and defence integration. Countries are ordered by level of support. Dashed line indicates the European mean.

Regression analysis

Pooled European analysis

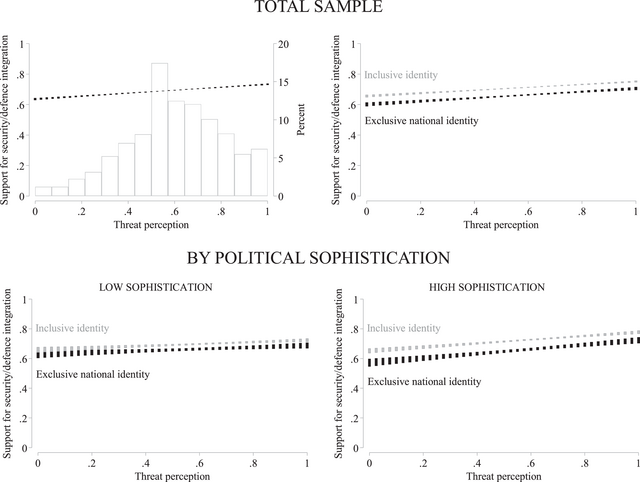

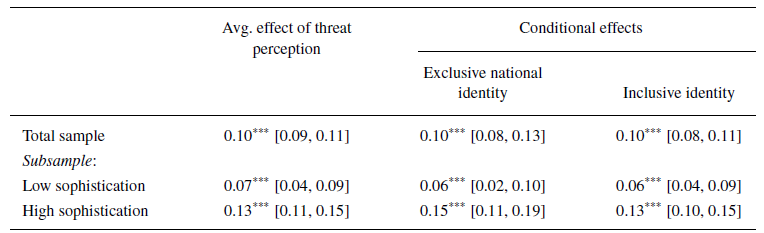

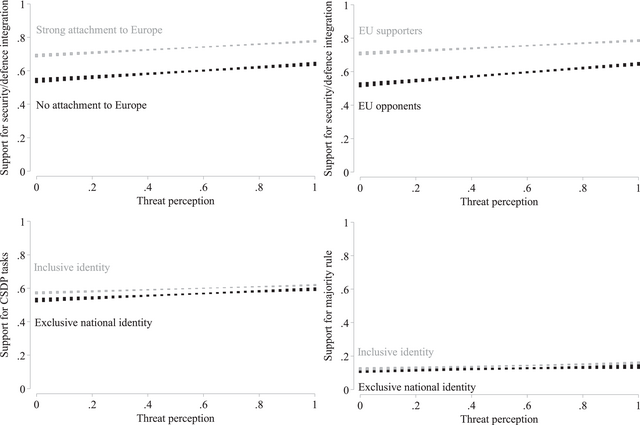

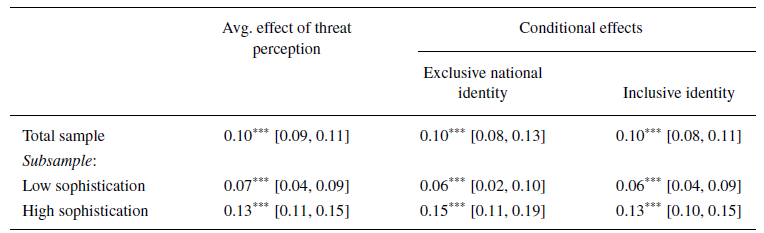

We begin with the pooled analysis, where the data from all countries are analysed simultaneously. Figure 3 shows the relationship between threat perception and support for security and defence integration (top left panel, based on Model 1 described above) as well as these effects conditioned on the two relevant identity configurations – exclusive national identity and inclusive identities (top right, based on Model 2). The lower two panels are based on Model 3 and show the effects of threat perception conditional on political sophistication and identity configuration. Table 1 reports the corresponding average and conditional effect estimates of perceived threat in numerical fashion. Full regression tables, including control and country indicator variables, are available in Supporting Information Appendix A4.

Figure 3. Pooled average and conditional effect of perceived threat. Note: Shown are estimates of support for security and defence integration from linear regressions with 95 per cent confidence intervals. The histogram in the top‐left panel reports the distribution of the threat perception index. High/low sophistication estimates based on extreme (max/min) values.

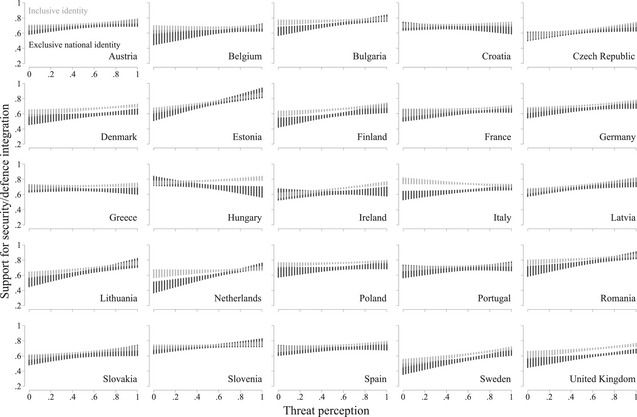

Figure 4. Country‐by‐country support for European defence and security integration, by threat perception and identity type. Note: Shown are estimates of support for security and defence integration from linear regressions with 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Table 1. Pooled average and conditional effects of perceived threat

Note: Entries are unstandardized marginal effects with 95% confidence intervals in parentheses. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

The first main finding is that higher perceptions of international threat are associated with more support for European security and defence integration (b = 0.10, p < 0.001). In terms of relative effect size, the point estimate of the threat perception effect is the third largest behind the willingness to compromise in international affairs (b = 0.24) and isolationism (b = –0.14). Standardized (beta) coefficients are 0.09 (threat perception), 0.20 (willingness to compromise) and –0.14 (isolationism). See Supporting Information Appendix A4 for full regression tables.

Second, interacting perception of threat with identity configuration shows that the pattern holds for citizens with exclusive national identity as well as inclusive identities: irrespective of identity configuration, we find a positive association of b = 0.10 between threat perception and support for European security and defence integration. Hence, as threat perceptions increase, both groups become more favourable toward this policy, but the average gap in support remains constant. Overall, these findings favour the functionalist view over the post‐functionalist view.

We also articulated a research question about the role of political sophistication. To see if the association of interest differs between politically sophisticated and unsophisticated citizens, the bottom row of Figure 4 reports marginal effects calculated from Model 3, that includes a three‐way interaction between the Threat, identity configuration and Political sophistication variables (also see Table 1). Based on this model, we can first calculate differences based on political sophistication irrespective of identity configuration. As reported in Table 1, the effect of threat perception is stronger at high levels of political sophistication (b = 0.13) than at low levels (0.07), which is consistent with the idea that reasoning about the merits of security and defence integration requires some level of expertise. At the same time, we do find a positive effect at low levels of political sophistication as well. Differentiating further, the results for the three‐way interaction confirm the conclusion above, that threat perceptions are positively associated with security and defence integration preference both among citizens with exclusive national identity and inclusive identities.

In sum, what emerges from this exploratory analysis of political sophistication most clearly is that sophistication seems to increase the strength of association on average, and that we find this general pattern irrespective of identity configuration. These findings are more in line with the functionalist than the post‐functionalist account reviewed above.

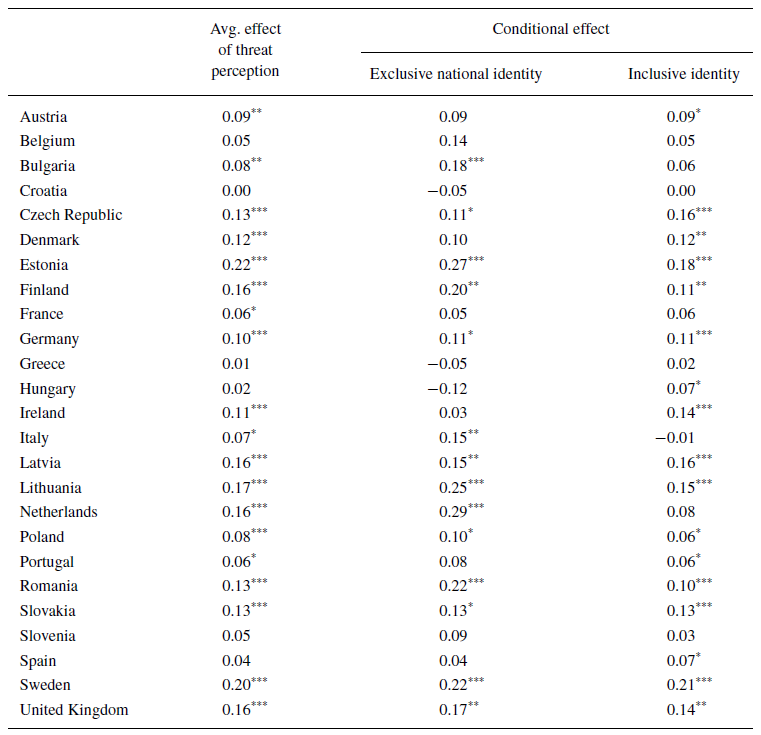

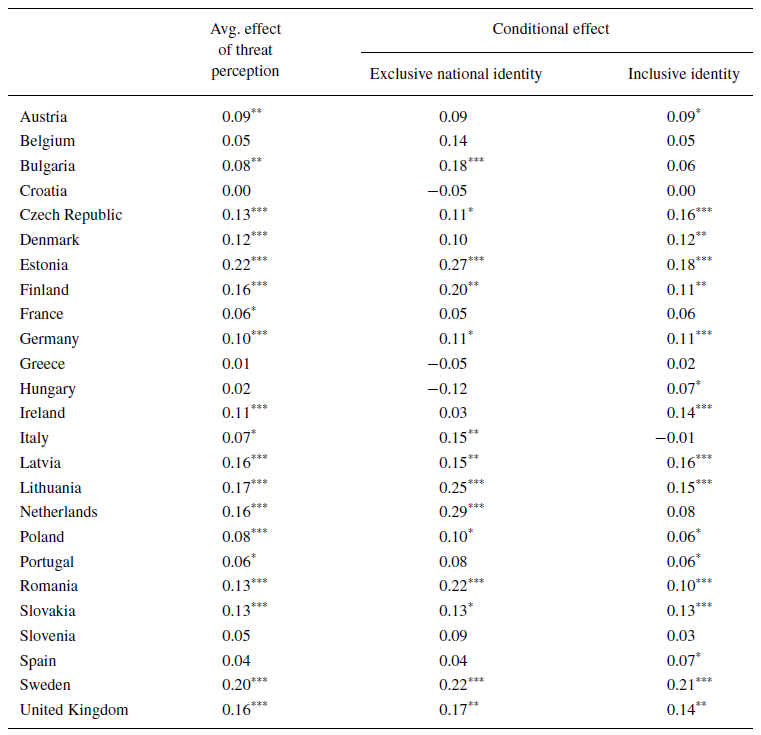

Country‐by‐country analysis

To help demonstrate the robustness of these findings, we replicate Models 1 and 2 separately for each of the 25 countries in our sample. As shown in Table 2 (column 1), we find reliable evidence of a positive association between threat perception and support for defence integration in 19 of the 25 countries, while there is no evidence of an average negative association in any of the samples. Whether variation in the effects for any specific country is due to random factors (e.g., sampling error) or systematic factors (e.g., country specific aspects) is not something we can establish with the current data. Anecdotally, we notice that Baltic and (at the time) non‐NATO Scandinavian countries exhibit some of the strongest relationships between threat perception and support for European defence and security integration, suggesting there may be some systematic national‐level factors. At the other end of the spectrum, we note that some of the smallest effects occur in countries that have a complicated (and at times contentious) relationship with the EU, namely Greece and Hungary, again suggesting the possibility of some national level effects. Analysing this cross‐country variation in more depth is an important task for future research.

Table 2. Average and conditional effects of perceived threat, country‐by‐country results

Note: Entries are unstandardized marginal effects from linear regressions. Subgroup effects calculated based on identity constellation (exclusive national identity vs. inclusive identity). # Technically, we report coefficients of the interaction term threat*inclusive identity, with exclusive national identity as reference category.

* p < 0.05;

** p < 0.01;

*** p < 0.001.

The second and third columns of Table 2 show the effect of threat perception separately for citizens with exclusive national identity and inclusive identity. The findings again mostly mirror those of the pooled analysis. The associations between threat perceptions and support for European security and defence policy integration are positive in both groups in the overwhelming majority of countries. However, they often differ in size between the subgroups and/or fail to reach conventional levels of statistical significance.

This might be merely the result of the smaller observation counts (that come with subsamples), which are bound to result in a wider distribution of point estimates and fewer significant coefficients. At the same time, we cannot rule out that these are genuine differences. This possibility should be taken all the more seriously because the deviant cases partly show coefficient patterns that can be taken as evidence for the post‐functionalist narrative of attitude formation. Hungary and, to a lesser extent, Greece are cases where the pattern of coefficients resembles that predicted in the post‐functionalist hypothesis (H2). While threat perceptions tend to be associated with lower support for security and defence integration among citizens with exclusive national identity in these countries, these effects are neither substantial nor statistically significant. We may nonetheless count this as weak evidence in favour of H2 – in 2 out of 25 cases. Given the overall pattern of coefficients, it seems fair to describe the results of the country‐specific analysis as largely consistent with the functionalist account of attitude formation, while there is little to be said for the post‐functionalist account.

Robustness and expansions

We carried out an extensive set of robustness tests. First, we added additional control variables, and results remain the same.Footnote 7 Second, we varied the operationalisation of the threat measure. Factor analysis of our five threat perception items indicated that these items constitute two distinct subdimensions of international threat perception in many countries. We hence computed two indexes capturing these subdimensions: one consisting of traditional, country‐related perceptions (Russia's territorial ambitions and the rise of China), and the other consisting of new, and often asymmetrical, threats (terrorist attacks, cyberattacks, and election mingling). Results are robust to using either subdimension (which are correlated with r = 0.50).Footnote 8

Fourth, we used an alternate measure of identity, namely the degree to which respondents feel attached to Europe (i.e., strength of European identity) as the interaction variable. The categorical measure of identity constellation used above levels differences in the strength of attachment to Europe and the nation within classes; furthermore, respondents right above and below the cut‐off values are actually quite similar in terms of their levels of attachment but coded into different groups. The results may hence underestimate the relevance of identity, at least for people with starkly different levels of attachments. Replicating the analyses with a quasi‐metric measure of attachment to Europe yields largely consistent findings. Only the relative importance of threat perception appears somewhat lower there, as it now has only the fourth strongest association in the model (b = 0.10), behind willingness to compromise (b = 0.22), attachment to Europe (b = 0.15) and isolationism (b = 0.13). The top left panel of Figure 5 reports the results of the key analysis regarding the effect of threat perception conditional on the level of attachment.Footnote 9

Figure 5. Robustness and expansions of pooled analysis. regression) with 95% confidence intervals. For details, see Supporting Information Appendices A7–A10.

In addition to these robustness checks, we explored four substantive expansions. First, we replicated the subgroup analysis using general EU attitude as the interaction variable. This measure is conceptually more distant to the arguments forwarded in the post‐functionalist perspective, as individuals can have positive or negative feelings towards the EU for different reasons. Perhaps post‐functionalist considerations related to identity are the most important, but the role of economic self‐interest and socio‐tropic concerns cannot be discarded. Worries about the effectiveness of European‐level solution making may feed into EU attitudes as well. Hence, using EU attitudes as the interaction variable, we explore the extent to which perceptions of international threat override general concerns about the effectiveness of addressing important problems at the EU level. The results are virtually the same as those reported above: we find a positive association between threat perception and support for European security and defence integration even among radical EU opponents. The top right panel of Figure 5 displays these results.Footnote 10

Second, we checked whether accounting for individuals’ views on NATO changes the results. The relationship between the EU's CSDP and NATO remains contested among decisionmakers (Hofmann, Reference Hofmann2013; Howorth, Reference Howorth2017), and citizens too might have distinct preferences with respect to these collective security institutions. We are particularly interested in those who support NATO but generally oppose EU (security and defence) integration – do these people also exhibit increased support for EU integration as their level of threat perception rises? Our data say they do. Even Eurosceptics who support NATO – and hence have an alternative ‘outside option’ to European security and defence – become more supportive of European defence integration as their perceived level of threat increases.Footnote 11

Third, we replicated the analyses with different outcome variables. Instead of general preferences for the level of security and defence integration we analyse more specific preferences regarding (1) the range of activities and (2) the decision rule that should occur in the security and defence domain. The first were measured using an index of responses to a battery of items in which respondents were asked to state their support for the EU being engaged in a range of security and defence activities. The second were measured with an item asking about how large a majority should be required when the Council makes decisions about EU security and defence issues. Against the backdrop of multidimensional conceptualisations of integration (e.g., Börzel, Reference Börzel2005), the activities variable captures the functional scope of European security defence integration, while the decision rule variable captures the preferred level of centralisation. For these attitudes, too, we find that the perception of international threat is associated with more favourable views on integration, and that this is true independent of identity configuration. The bottom half of Figure 5 displays these results.Footnote 12

Fourth, we probed the causal assumptions. As discussed previously, the statistical effects presented above are not causally identified, which raises concerns about endogeneity and omitted variable bias. Ardent supporters of European security and defence integration might rationalize their preference by perceiving international threats as particularly critical, and value orientations might shape both perceptions and attitudes. This constitutes a limitation of our research design and future experimental work will have to address these concerns more systematically. The theoretical specification of the relationship between heightened threat perception and enhanced desire for security and defence integration has, however, been rather vividly illustrated in the natural experiment of sorts provided by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The invasion represents an unforeseen, external shock that raised threat perceptions of Russia throughout Europe (Mader, Reference Mader2022). In line with the causal story told here, Europeans showed not only increased commitment to NATO (Smith, Reference Smith2022a, Reference Smithb), but also increased support for prioritizing European efforts to address security and defence issues (Eurobarometer, 2022), including the creation of an integrated European army (Smith, Reference Smith2022a).

Discussion and conclusion

This paper examines two competing mechanisms – functionalist and post‐functionalist – that lead to different expectations for how perceptions of threat relate to preferences for European integration in security and defence. A functionalist perspective suggests that heightened perceptions of international threats translate into more support view of defence for integration in this domain. In contrast, a post‐functionalist perspective assumes that threats activate group orientations that colour citizens’ evaluations of the more specific issue of security and defence integration. This leads to citizens who identify with Europe being more supportive of integration, whereas citizens who identify exclusively with the nation being less supportive of integration as threat levels increase.

Our analyses present evidence that strongly favours the functionalist view. We find a robust, albeit moderate, positive association between the perception of international threat and support for European security and defence integration. Importantly, this association does not vary as a function of citizens’ configuration of identities. This suggests a type of rally‐around‐the‐flag effect that is not based on identity or emotion activation (Feinstein, Reference Feinstein2020; Kam & Ramos, Reference Kam and Ramos2008) but is driven by effectiveness considerations. Importantly, we do not argue that these other types of rally effects are irrelevant – see Gehring (Reference Gehring2022) and Steiner et al. (Reference Steiner, Berlinschi, Farvaque, Fidrmuc, Harms, Mihailov, Neugart and Stanek2023) for evidence of an identity‐based European rally effect in the context of Russia's aggression against Ukraine. Rather, in addition to such effects, even citizens who generally are and remain Europhobes might see the merits of European integration in this policy area because they understand, perhaps reluctantly, that it is an effective policy.

Before discussing broader implications, we must be clear about limitations of the present research. While our interest lies in a causal question and we, accordingly, use language that comports with a causal account (e.g., ‘effects’), the cross‐sectional nature of the data cannot demonstrate causality. Potential threats to inference include endogeneity (support for security and defence integration causes perception of threat) and spuriousness (both support for integration and threat perceptions are explained by a third variable). While we think these two possibilities are unlikely, they cannot be ruled out. A second limitation is that while we have sketched two distinct psychological explanations, we do not directly test the implied mechanisms. For example, we have not presented evidence about how people with higher threat perceptions evaluate the effectiveness of international cooperation in general and European integration in particular. Future research may wish to focus more directly on testing such mechanisms. Against this backdrop, the evidence presented here can tell us whether one view/mechanism predominates, but cannot exclude the possibility that the other is not also present. Third, our treatment of identity has been limited to the dimension of attachment. Considering identity content – for example, how exclusively citizens define the boundaries of the nation and Europe (Aichholzer et al., Reference Aichholzer, Kritzinger and Plescia2021; Bruter, Reference Bruter, Herrmann, Risse and &Brewer2004; Mader & Schoen, Reference Mader and Schoen2023a) – might yield evidence consistent with the post‐functionalist view.

Setting aside these opportunities for improvement and differentiation, our results have two general policy implications. First and foremost, international organisations like the EU, who believe it beneficial to pool resources in order to increase the security of member states, should tailor communication efforts to better inform populations about (shared) international threats – without sensationalizing them. This applies to traditional country‐specific threats such as Russian territorial ambitions or China's increased importance on the world stage, as well as to newer/asymmetrical threats such as cyberattacks, terrorism and election meddling.

Second, countries with heightened opposition to general purpose international organisations like the EU can identify areas such as security and defence where public opinion tends to be less polarised, and target communication efforts about the benefits of increased integration in these areas. Hooghe's and Marks’ (Reference Hooghe and Marks2009) post‐functionalist ideas rest on the notion of politicisation of European integration. The functionalist explanation may hold sway in the security and defence arena at the moment because the issue is not yet sufficiently politicised and salient for people to take more nuanced stances. Targeted highlighting of integration and cooperation in such less politicised dimensions could potentially increase support (or at least decrease opposition) among sectors of the population less inclined to favour supra‐national integration elsewhere. Yet, it needs to be considered that the functionalist explanation is conditional on the current perception of threats. When threats are not being considered critical any longer, support for integration might plummet among Eurosceptics. Furthermore, our data already suggest that the condition of low politicisation might no longer exist in all countries. As our country‐by‐country analysis shows, in a few countries, citizens with an exclusive national identity – and EU opponents more generally – show decreased support for security and defence integration as perceived threat increases, that is, there we find the pattern that is predicted by the post‐functionalist view. Future research should examine how contextual conditions influence how people link threats and European security and defence integration in these countries. Of particular interest would be a close examination of whether Eurosceptic political entrepreneurs managed to successfully “flip the script” and politicise security and defence (De Vries & Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2020).

Applying these insights to the period after Russia's invasion of Ukraine, one of the crucial questions will be how permanent the increase in the perceived threat from Russia will be. Available evidence suggests that deeper underlying postures toward foreign and security policy may not have been significantly affected by Russia's invasion of Ukraine (Mader & Schoen, Reference Mader and Schoen2023b), raising the possibility that the shifts in public opinion that polls showed immediately after the invasion began (Mader, Reference Mader2022; Steiner et al., Reference Steiner, Berlinschi, Farvaque, Fidrmuc, Harms, Mihailov, Neugart and Stanek2023) will return to their pre‐invasion baselines. As other issues (re)claim the attention of policymakers and the public, will the perceived threat also decline? If so, our research suggests that the surge in support for European defence integration found in polls immediately after the invasion will be replaced by an opposite trend.

Our work suggests several avenues for future research. A deeper analysis of how threat perceptions relate to attitudes towards the other major ‘outside option’, that is, NATO, might be particularly productive. Here, we only showed that the same positive effect of threat perceptions on European defence holds among EU‐sceptic NATO supporters. An in‐depth analysis should go beyond this, however, and increase our knowledge of who prefers which institution if they had to choose – or show that citizens prefer more collective defence in general when they feel threatened, and do not care about the specific institution in which this is realized. Additionally, future research could consider whether support for integration is maintained in the face of trade‐offs, whether in monetary or sovereignty terms. While support for integrating policies is routinely high (Eichenberg, Reference Eichenberg2003; Mader et al., Reference Mader, Olmastroni and Isernia2020), such support may wilt as people learn about the policy area and trade‐offs (Carrubba & Singh, Reference Carrubba and Singh2004; Peters, Reference Peters2014).

Overall, our results paint a counter‐intuitive picture: opponents of the EU are more supportive of policy‐specific integration when perceiving critical security threats. In such instances, they act ‘against type’ and become more supportive of integration. This finding has major implications for the study of Euroscepticism and differentiated European integration. It suggests that Euroscepticism is potentially malleable when existential threats not internal but external to EU member states emerge.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the VW Foundation, Grant No. 94760.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data Availability Statement

Reproduction materials for this article are available at Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/7OY1CI.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: