Introduction

Populism has moved to the centre of public and scholarly attention in recent years. However, it is contested in the academic literature how the rise of populist forces to public office affects the quality of democratic regimes (see, among others, Canovan, Reference Canovan1999, Reference Canovan, Mény and Surel2002; Mény & Surel, Reference Mény, Surel, Mény and Surel2002; Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Rovira Kaltwasser2012). For one, scholars often point out that populism undermines core liberal democratic institutions, most importantly the rule of law (e.g., Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde, Rovira Kaltwasser, Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2012; Plattner, Reference Plattner2010). Other researchers ascribe to populism the potential to strengthen institutions of political participation and to improve the representative link between politicians and citizens due to its emphasis on vertical mechanisms of democratic accountability such as elections and direct democratic mechanisms (e.g., Canovan, Reference Canovan1999; Laclau, Reference Laclau2005; Mény & Surel, Reference Mény, Surel, Mény and Surel2002).

Researchers have also started to test these arguments about the relationship between populism and democracy empirically. In doing so, scholars focused their attention on specific norms and institutions of democracy and either concluded that populism is a threat or holds a corrective potential for democratic institutions and procedures (e.g., Houle & Kenny, Reference Houle and Kenny2018; Huber & Schimpf, Reference Huber and Schimpf2016; Kenny, Reference Kenny2019). Other scholars have investigated if populism in government or opposition poses a threat or corrective to the quality of liberal democracy (see Juon & Bochsler, Reference Juon and Bochsler2020; Vittori, Reference Vittori2021). However, beyond the focus on specific institutions or the liberal model of democracy, what is missing is a synthesis and systematic comparison of the ambivalent relationship between populism and different models of democracy based on its ideational foundations. This is highly relevant since both populism, as well as different models of democracy, trace their affinity towards specific combinations of institutions back to a set of norms and ideas. Hence, shifting our attention towards the underlying set of ideas in both concepts, allows us to move beyond the predominant focus on specific liberal‐democratic institutions and towards a more variegated assessment of populism's impact on different conceptions of democracy. Furthermore, to overcome the regional segmentation within the field of populism studies, we provide a cross‐regional comparative analysis of the relationship between populism in power (i.e., in government) and different models of democracy.Footnote 1 We include two regions which have been particularly affected by the rise of populism to power: Europe and Latin America.Footnote 2 To identify populist governments we build on three data‐sets; two on European cabinets (Huber & Schimpf, Reference Huber and Schimpf2016, Reference Huber and Schimpf2017) and parties (Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, Van Kessel, Frioio, Pirro, De Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde and Taggart2019) and one on Latin American presidential terms (Ruth, Reference Ruth2018). We combine these cross‐regional datasets with the expert‐coded data from the Varieties of Democracy Project (V‐Dem, Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Skaaning et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Skaaning, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Fish, Glynn, Hicken, Lührmann, Marquardt, McMann, Paxton, Pemstein, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning and Ziblatt2019) to capture five different models of democracy: electoral, liberal, deliberative, participatory and egalitarian. Our empirical analyses confirm the erosive potential of populist rule, in particular on the electoral, liberal and deliberative models of democracy. In addition, we find that this corrosive effect of populism decreases with the prior strength of democratic institutions and practices in each model of democracy. We were not able to corroborate any of the theoretically expected corrective potentials of populism, with respect to the participatory or egalitarian aspects of democracy. These findings hold even when controlling for extreme left or right ideology.

The paper is structured as follows: we first provide a short synthesis of populism studies as well as democratic theory. We proceed with a discussion on different models of democracy and connect them to several populist ideas emphasized in the literature to derive a set of testable hypotheses. Second, we introduce the data and methods and the methodological considerations behind our estimation procedures. In the final sections, we discuss our findings, present several robustness checks, and provide concluding remarks.

Towards an ideational theory of populism and democracy

For a long time, disagreement over conceptualization hampered the accumulation of knowledge about the causes and consequences of populism. Recently, however, a tentative consensus around an ideational definition of populism emerged in the field of political science (e.g., Hawkins & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Hawkins and Rovira Kaltwasser2017; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2018). In line with the ideational approach, we define populism as a set of ideas ‘that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volontée génrale (general will) of the people’ (Mudde, Reference Mudde2004, p. 543, italics original). Researchers adhering to the ideational approach usually agree on three core ideas that form the necessary defining characteristics of populism: people‐centrism, anti‐elitism, and an antagonistic relationship between the ‘virtuous people’ and the ‘corrupt elite’ (e.g., Hawkins, Reference Hawkins2010; Mudde, Reference Mudde2004; Rooduijn, Reference Rooduijn2014a). First, as part of the people‐centrism component, populists emphasise popular sovereignty as a core democratic idea, implying that citizens should authorize major political decisions (e.g., Canovan, Reference Canovan, Mény and Surel2002; Ochoa Espejo, Reference Ochoa Espejo2012). Relatedly, populists also refer to the will of the people, suggesting that a unified will of the people exists, which negates that citizens may have divergent interests and views, as well as challenges the representation of those interests. Second, the anti‐elitist notion of populism leads to a general distrust of elites, which results in a rejection of elite‐dominated political institutions, like parliaments or courts (e.g., Stanley, Reference Stanley2008). Finally, the idea of an antagonistic, Manichean worldview entails a moralistic and simplistic contrast of politics as ‘us’ (good) versus ‘them’ (bad), which justifies the vilification of opponents (Hawkins, Reference Hawkins2010), and stands in juxtaposition to basic principles of pluralism or consensus‐seeking institutions. We expect these populist core ideas to have divergent effects on different models of democracy.

This ideational definition is particularly well equipped for the comparative analysis of populism across time and space (Hawkins, Reference Hawkins2010; Hawkins, Aguilar et al., Reference Hawkins, Aguilar, Silva, Jenne, Kocijan and Kaltwasser2019; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde, Rovira Kaltwasser, Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2012). Furthermore, it does not preclude the specification of subtypes of populism through the combination of populist ideas with other ideological, organizational or personalistic elements (March, Reference March2007; Mudde, Reference Mudde2007; Roberts, Reference Roberts and de la Torre2018; Weyland, Reference Weyland, Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy2017). Most importantly, the ideational approach lends itself well to measure populism in systematic (both qualitative and quantitative) ways allowing researchers to test causal arguments (Aslanidis, Reference Aslanidis2018; De Cleen & Stavrakakis, Reference De Cleen and Stavrakakis2017; Hawkins, Carlin et al., Reference Hawkins, Carlin, Littvay and Rovira Kaltwasser2019).

Democracy is an even more contested concept than populism. Even today, there is no consensus on what democracy means other than the vague idea of ‘rule by the people’ (Collier & Levitsky, Reference Collier and Levitsky1997; Munck, Reference Munck2016). However, there are many different ways in which ‘rule by the people’ can be institutionalized, depending on which democratic ideas are emphasized, for example, equality or freedom. A simultaneous maximization of all desirable democratic ideas is impossible (see Giebler & Merkel, Reference Giebler and Merkel2016). Therefore, democratic theorists and empirical democracy scholars alike usually refer to different patterns, models or varieties of democracy, dependent on the ideas they consider most desirable and the institutional trade‐offs resulting from them (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Altman, Bernhard, Fish, Hicken, Kroenig, Lindberg, McMann, Paxton, Semetko, Skaaning, Staton and Teorell2011; Held, Reference Held2006; Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1999; Lucardie, Reference Lucardie2014). The liberal model of democracy, for example, champions the idea that citizens need to be free from intrusive political authority, that is, negative freedom. Representative government, constitutional checks, and the rule of law are all institutional expressions of the liberal model aiming to protect citizens from the dangers of despotic power (see Held, Reference Held2006, pp. 78–79). Hence, we argue that a focus on the ideational foundations of both populism and democracy enables us to carve out the potential frictions between or complementarity of populism and democracy more clearly. In line with other ideational scholars, we do not assume that ideas themselves translate into institutional change, but that political actors supporting these ideas may act on them (Hawkins & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Hawkins, Rovira Kaltwasser, Hawkins, Carlin, Littvay and Rovira Kaltwasser2019, p. 5).Footnote 3

Thus, populist forces often come to political power with an agenda of institutional change to better approximate their idea about democracy, and thereby reform representative democracy (Decker, Reference Decker, Wielenga and Hartleb2011; Dubiel, Reference Dubiel1986; Levitsky & Loxton, Reference Levitsky and Loxton2013). For instance, the former Peruvian president Alberto Fujimori proclaimed himself as the ‘architect of modern democracy’.Footnote 4 In 2017, decades after his autogolpe in 1992, he justified his move to dissolve parliament as a step to ‘safeguard democracy’.Footnote 5 The Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez portrayed himself as a fighter for ‘revolutionary democracy’ and human rights.Footnote 6 In Hungary, Victor Orbán propagates that ‘a democracy does not necessarily have to be liberal’.Footnote 7

It is no surprise that researchers have also debated the affinity between populism and authoritarianism (Norris & Inglehart, Reference Norris and Inglehart2019; Levitsky & Loxton, Reference Levitsky and Loxton2013; Müller, Reference Müller2016). Among European scholars it is mainly the populist radical right which is associated with authoritarian tendencies (on a critical review see Bonikowski, Reference Bonikowski2017; Mudde, Reference Mudde2007; Rooduijn, Reference Rooduijn2014b), while Latin American scholars associate leftist populists with the rise of competitive authoritarianism (Levitsky & Loxton, Reference Levitsky and Loxton2013). We argue here, that to study the consequences of populism on different democratic models it is important to distinguish different phases of populist success. While populists often gain public office with a promise of reforming, improving, and deepening democracy, once in power, the same populists may erode core democratic institutions to maintain power over time (Chesterley & Roberti, Reference Chesterley and Roberti2018; de la Torre, Reference de la Torre2000). Hence, although (core) populist ideas per se are not undemocratic, they may be used to undermine democracy and enable the election of authoritarian‐leaning leaders into public office (Bonikowski, Reference Bonikowski2017, pp. 189–191; Hawkins, Reference Hawkins2010, pp. 29–33).

A clash of ideas: The ambiguous relationship between populism and democracy

The normative theoretical debate on populism has been intimately connected to the study of democracy (e.g., Canovan, Reference Canovan1982; Laclau & Mouffe, Reference Laclau and Mouffe1985; Urbinati, Reference Urbinati1998). Several arguments in the literature refer to the ambiguous relationship between these two concepts (e.g., Mény & Surel, Reference Mény, Surel, Mény and Surel2002; Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Rovira Kaltwasser2012). This ambiguity can be traced back to tensions between core ideas of populism and different models of democracy, such as ‘the will of the people’ and representative government (see Mair, Reference Mair2009; Urbinati, Reference Urbinati1998). In this section we will disentangle the connections between these two ideational concepts. Focusing on the ideas central to the populist appeal enables us to theorize on and later test the relationship between populism and democracy (see Hawkins, Carlin et al., Reference Hawkins, Carlin, Littvay and Rovira Kaltwasser2019).

With respect to different models of democracy, we follow the V‐Dem approach of distinguishing between electoral, liberal, participatory, deliberative and egalitarian models of democracy (Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge, Lindberg, Skaaning and Teorell2016), and discuss each of them in turn.

Electoral democracy

The most fundamental conception of democracy is the model of electoral democracy. In its minimalist expression, it refers to the procedures of repeated competition between political elites for votes, which traces back to the idea of political equality, that is, one person one vote (Møller & Skaaning, Reference Møller and Skaaning2010; Munck & Verkuilen, Reference Munck and Verkuilen2002; Schumpeter, Reference Schumpeter1950). Conceptualizations that are more extensive add factors that ensure the meaningfulness of elections as instruments of democracy, like the protection of freedom of expression and association, the availability of alternative sources of information and the freedom of the press (e.g., Dahl, Reference Dahl1956, Reference Dahl1971). This more ambitious notion of electoral democracy, which Robert Dahl has labelled ‘polyarchy’, is our focus here.

The association between populist ideas and electoral democracy is somewhat ambiguous: The people‐centrism of the populist appeal – with its focus on popular sovereignty – puts an emphasis on vertical mechanisms of accountability, most importantly, elections (Canovan, Reference Canovan1999; Ochoa Espejo, Reference Ochoa Espejo and De la Torre2015). Hence, we do expect populists in power to value elections as a viable tool to make the will of the people known and to legitimize their leaders. However, people‐centrism also builds on the idea of the homogeneity of the people, which clashes with several of the preconditions of polyarchy, such as the freedom of expression, the freedom of association or media pluralism (see Juon & Bochsler, Reference Juon and Bochsler2020; Kenny, Reference Kenny2019; Vittori, Reference Vittori2021). Moreover, due to their inclination towards vilifying opponents and portraying themselves as the only legitimate interpreter of the will of the people, populists may also justify hollowing out electoral procedures and skewing the playing field, thereby threatening one of the core ideas of electoral democracy, that is, the fairness of elections (Hawkins, Reference Hawkins2010; Levitsky & Loxton, Reference Levitsky and Loxton2010). In sum, we argue that populist ideas indicate considerable friction with the ideas on which polyarchy builds, and hence, hypothesize the following negative relationship between the two concepts:

Hypothesis 1: Populists in power are likely to have a negative effect on the electoral model of democracy.

Liberal democracy

The most prominent model is probably the model of liberal democracy. In addition to meaningful elections, liberal democracies are characterized by the rule of law, understood as the constitutional protection of civil liberties, an independent judiciary, as well as the separation of power through institutional checks on the government (see Møller & Skaaning, Reference Møller and Skaaning2010; O'Donnell, Reference O'Donnell, Mainwaring and Welna2003; Plattner, Reference Plattner1999). The liberal model takes a critical view on majority rule and highlights the need to safeguard social and organizational pluralism as well as individual liberties and rights from infringement by ruling elites, that is, the protection against a potential tyranny of the majority (Dahl, Reference Dahl1989; Zakaria, Reference Zakaria1997).

Based on the literature, a more clear‐cut negative relationship can be argued for with respect to the liberal model of democracy. Theoretically, due to their focus on the sovereignty of the people (people‐centrism), populists value vertical accountability overall and at the same time – in line with their anti‐elitism – advocate to mistrust political elites, which are the core actors within horizontal accountability mechanisms (see Stanley, Reference Stanley2008). Several studies showed that populist governments have engaged in the erosion of horizontal accountability mechanisms, especially if traditional elites played a central role in them (Juon & Bochsler, Reference Juon and Bochsler2020, Houle & Kenny, Reference Houle and Kenny2018; Ruth, Reference Ruth2018, Vittori, Reference Vittori2021). Moreover, while liberalism's biggest fear is the tyranny of the majority, which threatens its pluralist core, populism favours majoritarianism as a means to identify the will of the people (Grofman & Feld, Reference Grofman and Feld2013; Plattner, Reference Plattner1999). The friction of populism's ideas of popular sovereignty and the homogeneity of the people (people‐centrism) along with the ideas of societal pluralism and its protection through the rule of law at the core of liberal democracy, leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Populists in power are likely to have a negative effect on the liberal model of democracy.

Deliberative democracy

While the electoral and liberal models emphasize the input legitimacy of democratic systems, the deliberative model of democracy shifts its attention towards the throughput side of the democratic process (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1999; Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2013). Deliberative democracy focuses on the pursuit of the public good through respectful dialogue and public reasoning (e.g., Dryzek, Reference Dryzek2010; Fishkin, Reference Fishkin1991; Habermas, Reference Habermas1992). Citizens and elites need to be open‐minded and take informed decisions after exchanging arguments and discussing different views on the issue at hand (see Saward, Reference Saward2000).

This stands in clear juxtaposition to the so‐called radical democratic ideas associated with populism. Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser (Reference Mudde, Rovira Kaltwasser, Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2012) even argue that the normative theoretical framework surrounding populism, originally designed by Laclau and Mouffe (Reference Laclau and Mouffe1985), is a reaction ‘to the models of deliberative democracy of Jürgen Habermas and the “Third Way” of Anthony Giddens’ (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde, Rovira Kaltwasser, Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2012, p. 15). We argue here that the antagonistic relationship between ‘the corrupt elite’ and ‘the good people’, as well as the homogenous and anti‐pluralist view of ‘the people’, both inherent components of populism, stand in sharp juxtaposition to the logic of deliberation, which builds on reasoned disagreement among people and is geared towards compromise (Hawkins, Reference Hawkins2010; Laclau, Reference Laclau2005; Taggart, Reference Taggart, Mény and Surel2002). These arguments lead us to expect a negative relationship between populism and deliberative democracy.

Hypothesis 3: Populists in power are likely to have a negative effect on the deliberative model of democracy.

Participatory democracy

The participatory model of democracy, on the other hand, is far less concerned with majority rule as a means to identify the will of the people as long as citizens participate actively in the political process (Grofman & Feld, Reference Grofman and Feld2013; Pateman, Reference Pateman2012). It emphasizes the value of self‐government and citizen participation beyond elections (Fung & Wright, Reference Fung and Wright2003; Pateman, Reference Pateman1976). In addition to civil society participation, it focuses on instruments of direct as well as local and regional democracy. Populism has often been associated with a radical democratic model based on a plebiscitary style of participation (Laclau & Mouffe, Reference Laclau and Mouffe1985; Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Rovira Kaltwasser2012, Reference Rovira Kaltwasser2014). In particular, their affinity towards direct democratic mechanisms has frequently been highlighted in the literature (e.g., Bowler et al., Reference Bowler, Donovan and Karp2007; Canovan, Reference Canovan1999; Gherghina & Pilet, Reference Gherghina and Pilet2021; Jacobs et al., Reference Jacobs, Zaslove and Akkerman2018; Mény & Surel, Reference Mény, Surel, Mény and Surel2002; Rhodes‐Purdy, Reference Rhodes‐Purdy2015; Ruth & Welp, Reference Ruth and Welp2018). Populist ideas resonate well with the divisiveness and alleged simplicity of the majoritarian logic of direct democratic mechanisms, that is, they divide political decisions into (binary) yes or no questions. Hence, we expect populism to be positively associated with participatory democracy.

Hypothesis 4: Populists in power are likely to have a positive effect on the participatory model of democracy.

Egalitarian democracy

Finally, the model of egalitarian democracy combines the ideas of both political and social equality and that all citizens need to have the same opportunities to participate in the democratic process to make themselves heard (Dahl, Reference Dahl1989). Hence, the model emphasizes the preconditions of political participation as well as the capability of all citizens to participate meaningfully in political decision making. Egalitarianism also considers an active role of the state in the economy, combating the unequal distribution of resources which may lead to unequal political power (see Saward, Reference Saward1998; Shefner, Reference Shefner and Hilgers2013).

Populism resonates well with these ideas. For one, populists paint a positive view of ‘the people’ and their capability of participating in political decision making (see Canovan, Reference Canovan1999). Moreover, populist actors often highlight that economic inequalities translate into political inequalities, emphasizing the unequal power distribution between the ‘ordinary people’ and powerful elites (see Foweraker, Reference Foweraker2018, Cerovac, Reference Cerovac2014). These arguments lead us to expect a rather positive relationship between populism and egalitarian democracy.

Hypothesis 5: Populists in power are likely to have a positive effect on the egalitarian model of democracy.

However, to study the association between populism and egalitarian democracy, in particular, we also need to disentangle these core populist ideas from the ideological leanings of populist actors. Although all populist forces portray ‘the people’ as a homogeneous group, some populists on the right side of the ideological spectrum exclude large parts of the population from the demos, while inclusionary populists on the left tend to include larger segments of the population (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2013; Ochoa Espejo, Reference Ochoa Espejo and De la Torre2015). Hence, it has often been argued that left‐leaning populists are associated with inclusive, redistributive welfare policies, while right‐leaning populists have been associated with exclusionary, redistributive welfare policies, for example, welfare chauvinism (see Abts et al., Reference Abts, Dalle Mulle and Michel van Kessel2021; Derks, Reference Derks2006; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2013). Hence, to study the effect of populism, we need to rule out this confounding factor and control for the ideology of (populist or non‐populist) governments.

Strong versus weak democracy

In their seminal contribution on populism and (liberal) democracy, Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser highlight that ‘populists will be more effective when democracy is weak; or to put it in another way, the strength of democracy influences the depth of the populism's impact on democracy’ (Reference Mudde, Rovira Kaltwasser, Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser2012, pp. 22–23). Following this framework, we hypothesize that an important moderating factor that can safeguard democracy against erosive as well as corrective tendencies of populist governments, is the ex‐ante degree of democratic quality (see also Schedler, Reference Schedler1998, and more recently, Weyland, Reference Weyland2020). In general, well‐developed democratic institutions and norms constrain the ability of governments to erode them (Keane, Reference Keane2009; Levitsky & Murillo, Reference Levitsky and Murillo2013; O'Donnell, Reference O'Donnell1996). For example, Boese et al. (Reference Boese, Edgell, Hellmeier, Maerz and Lindberg2020) have shown that well‐developed judicial institutions may help to safeguard democracies against breakdown. Hence, we assume that the impact of populist governments on each democratic model is moderated by its initial quality.Footnote 8

Hypothesis 6: The lower the quality of a specific model of democracy is, the stronger the hypothesized effect of populists in power is on the respective model of democracy.

Data and methods

Empirical studies testing the relationship between populism and democracy have been dominated by an exclusive focus on the partial effect of populism on different democratic principles or functions, a nearly perfect regional segmentation of the field and a focus on region‐specific subtypes of populism (Aslanidis, Reference Aslanidis2017; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2018). To foster the integration of the field and the accumulation of knowledge on the topic, this paper relies on a cross‐regional research design, comparing 18 democracies in Latin America to 29 democracies in Western and Eastern Europe.Footnote 9 We focus on these regions for three reasons: first, they have a prolonged experience with democratic rule, at least since the 1990s. Second, several countries within each region experienced the rise of populists to political power within the studied time frame. Finally, extensive research from populism scholars led to better data availability to empirically test our arguments, compared to other regions, like Africa or Asia. Moreover, we will leverage the cross‐regional variation in our sample to gauge if our hypothesized relationships hold universally across different regions.

Operationalization

Quality of different models of democracy: In order to assess the relationship of populism with different democratic models, we use the expert‐coded data from the Varieties of Democracy Project (V‐Dem, Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Skaaning et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Skaaning, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Fish, Glynn, Hicken, Lührmann, Marquardt, McMann, Paxton, Pemstein, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning and Ziblatt2019) to capture our dependent variables. V‐Dem provides more than 350 indicators on various aspects of democracy for 182 countries from 1900 to 2018. A sophisticated protocol for the recruitment of typically five experts per data point, and the aggregation of their responses, enhances the reliability of the expert‐coded data (see Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell et al., Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Marquardt, Medzihorsky, Pemstein, Pernes, von Römer, Stepanova, Tzelgov, Wang and Wilson2019; Pemstein et al., Reference Pemstein, Marquardt, Tzelgov, Wang, Krusell and Miri2018). V‐Dem constructs so‐called high‐level indices (HLIs) based on its indicators in order to capture the level of electoral, liberal, participatory, egalitarian and deliberative democracy. Coppedge et al. (Reference Coppedge, Lindberg, Skaaning and Teorell2016) introduce and validate this conceptual and measurement scheme.Footnote 10 All indices range from 0 (not at all democratic) to 1 (fully democratic).

-

• The V‐Dem electoral democracy index (EDI) captures key electoral institutions of democracy for leaders to be held accountable and responsive towards the people, and achieving a fundamental principle of democracy: the sovereignty of the people. The EDI comprises six components that together cover the central electoral aspects of democracy: the clean elections index, the freedom of association index, the freedom of expression and alternative sources of information index, the suffrage indicator and the elected officials’ index.

-

• The V‐Dem liberal component index (LCI) captures the central liberal aspect of democracy that ensures citizens’ and minority groups’ protection from the tyranny of the state and of the majority. It includes equality before the law and individual liberty as well as judicial and legislative constraints on the executive.

-

• The V‐Dem participatory component index (PCI) captures additional mechanisms (beyond elections) through which citizen can input their preferences into democratic processes. It is based on four sub‐indices on civil society participation, direct popular vote, local and regional government.

-

• The V‐Dem deliberative component index (DCI) is based on five indicators on the behaviour of political elites capturing reasoned justification, common good orientation, respect for counterarguments, the range of consultation, and lastly, engagement of society. This index reflects that democratic decision making should demonstrate public reasoning by motivating policy decisions with a focus on the larger common good rather than through emotional appeals, coercion or solidarity attachments.

-

• Egalitarian notions of democracy emphasize that an unequal society obstructs democratic mechanisms such as participation and representation by failing to achieve an equal distribution of protection and resources. The V‐Dem egalitarian component index (ECI) capture this dimension of democracy by including indices on equal protection of rights and freedoms, equal access to power and equal distribution of resources.

We include the level of each of these indices at t0 as the dependent variables in our models below.

Measuring populism: Since our arguments trace back to the underlying ideas of populism, our measure builds on the ideational approach to distinguish populist from non‐populist governments as well. Systematic data on populist governments is scarce. However, we build on three datasets that have recently become available, each capturing populism as a dichotomous variable. First, for Latin America, we rely on the presidential terms dataset from Ruth (Reference Ruth2018) which follows a two‐step procedure to identify populist governments based on a combination of both a qualitative literature review and expert validation. This dataset covers 18 countries from 1980–2018.

Second, for the coding of populist governments in Europe we combine two data sources. To identify which European party qualifies as populist, we utilize Rooduijn et al.’s (Reference Rooduijn, Van Kessel, Frioio, Pirro, De Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde and Taggart2019) recent comprehensive account, which is based on expert assessments of all political parties which gained at least 2 per cent of the vote share in 30 European countries from 1995–2018. We combine this data with data provided by Huber and Schimpf (Reference Huber and Schimpf2016, Reference Huber and Schimpf2017) to identify when prime ministers affiliated with these parties held office.Footnote 11

Merging these datasets leaves us with a cross‐regional coverage of 24 years (1995–2018), including 289 consecutive tenures in 47 countries. Overall, our sample includes 30 populist and 259 non‐populist presidents or prime ministers ruling for on average 4 years (ranging from one to 18 years in office).Footnote 12 Based on this information, we construct a dummy variable which captures the presence (1) or absence (0) of a populist chief executive in each year (at t‐1) as the main independent variable in our models below.

Moderating factor: To account for the potential moderating effect of the quality of each democratic model (H6) we include a lagged (dependent) variable of the level of each model of democracy (at t‐1) in our estimations. We discuss the methodological implications of the inclusion of a lagged dependent variable in more detail below.

Control variables: We include several covariates to control for potential other effects on the level of democracy. In particular, both extreme left and extreme right ideologies might influence the propensity of chief executives to both use populist rhetoric and erode democracy. Hence, to account for extreme ideologies of chief executives in Europe, we rely on the coding from Rooduijn et al. (Reference Rooduijn, Van Kessel, Frioio, Pirro, De Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde and Taggart2019) which groups political parties into radical left, radical right or centrist on a classical left‐to‐right spectrum. The category ‘centrist’ is very broad and includes moderately ideological parties on both sides of the spectrum, genuinely centrist parties and non‐ideological parties. To mirror this coding logic for Latin America, we use data from Murillo et al. (Reference Murillo, Oliveros and Vaishnav2010) which measure the political ideology of presidents and parties on a five‐point scale from left‐to‐right, which we recode into three categories (collapsing centre‐left, centre, and centre‐right cases). We expand the coding until 2018. This leaves us with a three‐categorical variable, which allows us to best approximate the extremeness of ideologies of political actors.

As most researchers believe economic variables are connected to autocratization (Haggard & Kaufman, Reference Haggard and Kaufman2016), GDP per capita and GDP per capita growth are included. The data on GDP per capita levels and growth (measured in 2011 USD and corrected for inflation) were collected from the Maddison Project Database (Bolt et al., Reference Bolt, Inklaar, de Jong and Luiten van Zanden2018). We use the logged version of both GDP per capita measures to account for an exponential effect. Furthermore, we include a variable on economic gains from oil production, accounting for arguments concerning a negative relationship between an oil‐based economy and democracy (Ross, Reference Ross2001; World Bank, 2019). We also account for the length of each chief executive's tenure, as leaders who stay in office longer are more likely to engage in erosive behaviour such as attempting to perpetuate their hold on power even beyond legal terms (e.g., Corrales, Reference Corrales2016; Vencovsky, Reference Vencovsky2007). Moreover, several studies suggest a relationship between economic inequality and democratic backsliding due to a translation of individual economic anxiety into politics followed by demands for a ‘strong’ leader (Galston, Reference Galston2019; Haggard & Kaufman, Reference Haggard and Kaufman2016; Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2018). To control for economic inequality we use Gini data on disposable income from the standardized world income inequality database (SWIID; Solt, Reference Solt2016), which runs from 0 to 100, with high values indicating more inequality. All of these control variables enter our models as a one‐year lagged version (t‐1).

Methods

Our estimations are based on time‐series cross‐sectional data, covering 47 European and Latin American countries from 1995–2018 (n = 1115). We estimate fixed‐effects models with both country‐ and time‐fixed effects to gauge the yearly impact of populist governments on the level of different models of democracy. While country‐fixed effects allow us to account for unobserved heterogeneity between countries in our sample, we include time‐fixed effects to account for unobserved shocks that hit all our countries equally (see Allison, Reference Allison2009). Moreover, we estimate cluster‐robust standard errors to account for within group correlation of the error term (see Cameron & Miller, Reference Cameron and Miller2015).Footnote 13

Since we assume that the impact of populist governments on different models of democracy depends on previous levels of democracy, we include a lagged dependent variable in our models (at t‐1) (Keele & Kelly, Reference Keele and Kelly2006). We opt for this dynamic model specification for substantive reasons, since H6 leads us to expect that the impact of populism in power is conditional on previous levels of each democratic model.

Results and discussion

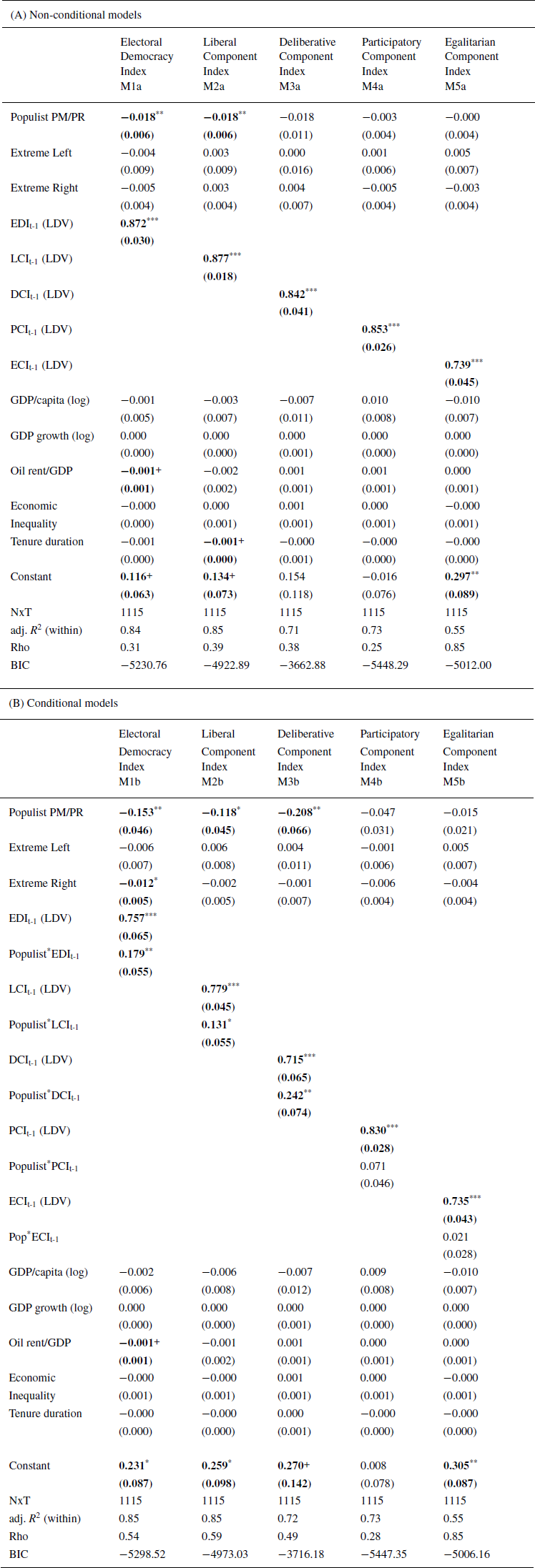

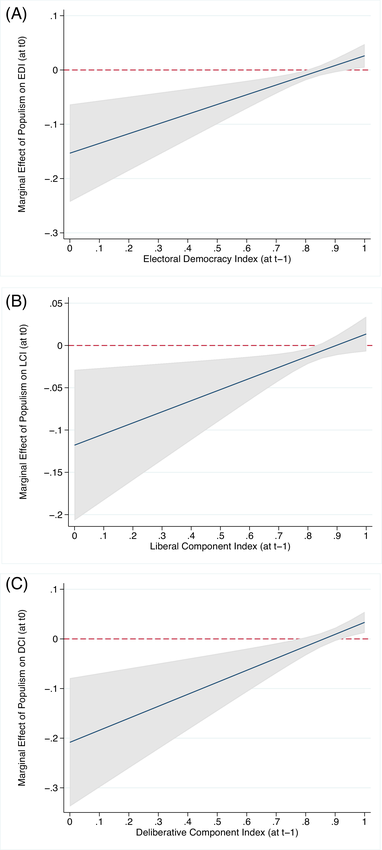

This paper studies to what extent populist‐led governments alter the quality of democracy during their rule in different ways. According to our theoretical expectations, we hypothesize that the impact of populism may be moderated by the previous strength of democracy. Therefore, in Table 1(A) we report the non‐conditional model, and in Table 1(B) the conditional model for each of our dependent variables (i.e., V‐Dem indices). The former aims at gauging the direct partial effect of populism (testing H1‐H5), while the latter aims at capturing the moderating influence on this effect by previous levels of democracy (testing H6). In addition, Figure 1 shows the average marginal effect of populism on different democratic models across varying levels of democracy (Brambor et al., Reference Brambor, Clark and Golder2006).

Table 1. Populism and democracy in 47 countries (1995‐2018)

Note: Fixed‐effects models with clustered standard errors in parentheses. Reference category for extreme left/right is centrist/non‐ideological. Time‐fixed effects included but not reported.

Abbreviations: PM, prime minister; PR, president; LDV, lagged‐dependent variable; EDI, electoral democracy index; LCI, liberal component index; DCI, deliberative component index; PCI, participatory component index; ECI, egalitarian component index.

+ p < 0.10;

* p < 0.05;

** p < 0.01;

*** p < 0.001.

Figure 1. Marginal effect of populism conditioned by strength of democracy [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Overall, despite mixed‐theoretical expectations, our results suggest a rather negative impact of populism on several models of democracy. Concerning the results from the non‐conditional models (see Table 1A), the correlates of change in V‐Dem's Electoral Democracy Index (EDI), Model 1a in Table 1(A), indicate that a populist‐led government is associated with a statistically significant (p < 0.05) average decrease of the EDI of 0.018 points per year (se = 0.006) or 13 per cent of its standard deviation (0.14 points) in our sample. This is equivalent to a yearly 1.8 per cent decrease of the index, which runs on a 0–1 scale. This implies that during a 5‐year term of populist rule the level of electoral democracy is predicted to decrease by 9 per cent. Thus, the predicted negative effect is substantially meaningful, and our results suggest a clearly negative effect, as expected (H1).

The picture is similarly dire, when looking at the predicted effect of a year of populist rule on the Liberal Component Index (Model 2a). Again, we estimate an average annual decline of 1.6 per cent on the V‐Dem index, which is in line with our expectations (H2).Footnote 14 In contrast, at least in our non‐conditional models, we cannot support the expected negative effect on the quality of public debate and deliberation (Model 3a, H3), nor the expected positive association between populism and the models of participatory (Model 4a, H4) or egalitarian democracy (Model 5a, H5). While the coefficient in Model 3a – capturing the effect of populism on the V‐Dem deliberative component index – points in the expected direction, it does not reach conventional significance levels. Contrary to our expectations, Model 4a estimates a negative, although statistically insignificant, relationship between populism and the participatory component index (PCI). Finally, Model 5a suggests that populism does not have the expected relationship to the egalitarian aspects of democracy either, as indicated by the negative sign of the coefficient.Footnote 15

Testing the role of democratic strength

While these average effects are substantial and relevant, the question remains if a populist's effect on democracy is conditional on the prior strength of the respective model of democracy (H6). Therefore, we ran conditional models including interaction terms (see Table 1B). Results in Table 1(B) confirm our expectation at least for three models of democracy, as we find statistically significant conditional effects with respect to the electoral, liberal, and deliberative models of democracy (Models 1b, 2b and 3b), substantiated by different goodness of fit measures (i.e., adj. R2 as well as BIC, see Table 1B).Footnote 16 The size of these conditional effects – which is strongest for the deliberative model, followed by the electoral model, and finally, the liberal model of democracy – alludes to the greater vulnerability of electoral and deliberative democracy to implicit norm violations by populist actors, as opposed to the more formally often constitutionally anchored institutions of liberal democracy, which are more difficult to change (see also Levitsky & Ziblatt, Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018; Habermas, Reference Habermas1992). We do not find any conditional effect for the participative or egalitarian models of democracy.

To ease the interpretation of these results, Figure 1 reports the average marginal effect of populist‐led governments at different prior levels of the respective model of democracy. The figures illustrate that the effect of populist‐led governments becomes less severe with increasing levels of democracy and turns statistically insignificant above an EDI of about 0.85, a LCI of about 0.85 or a DCI level of about 0.80.Footnote 17

Robustness checks

In order to check the robustness of the findings, we carry out a range of additional tests. To account for the potential bias resulting from the inclusion of a lagged dependent variable in fixed‐effect models (Nickell, Reference Nickell1981), we provide alternative model specifications with panel‐corrected standard errors (see Beck & Katz, Reference Beck and Katz1995, Reference Beck and Katz1996) and different lag‐structures, using a 2‐year lag as well as a 5 year lagged average of the dependent variable instead (see Plümper & Troeger, Reference Plümper and Troeger2019). The results are exceptionally robust with respect to our main findings (see Tables S3 and S4b in the Supporting Information). Moreover, we reran our non‐conditional models using the change from t‐1 to t0 in each democratic model as the dependent variable and as an alternative specification to test H1‐H5. Results remain remarkably robust and are reported in Table S5 in the Supporting Information.

Moreover, to account for regional differences, we split our sample into two regional ones (Western and Eastern Europe as well as Latin America) – and re‐ran the same models (see Tables S6a and 6b in the supplement). Results indicate that the effect on the electoral model is most consistently relevant in both regions, both in the non‐conditional and conditional models (supporting H1 and H6 for this particular model of democracy). Moreover, in both regions, populism has a negative, significant association with the liberal model of democracy (supporting H2). However, some findings differ by region. For one, the effect of populism on liberal democracy is conditional on previous levels of democracy in Latin America, but non‐conditional in Europe (only partially supporting H6). Moreover, in the European sample we cannot confirm any impact of populism on either the deliberative, participatory or egalitarian models of democracy. Instead, we find a fairly consistent and significant negative effect of extreme right ideology on the electoral, liberal, deliberative and participatory models of democracy. In the Latin American sample, the impact of populism is significant and negative with respect to the deliberative model of democracy in both the conditional and unconditional models (supporting H3 and H6). Additionally, we find a statistically significant conditional effect of populism on participatory and egalitarian democracy in Latin America, but in the negative direction (partially supporting H6, but not H4 and H5).

Conclusion and way forward

The seemingly ambiguous relationship between populism and democracy has puzzled researchers for decades. With this article we investigate the relationship between populism and democracy within an integrated framework across two world regions particularly affected by populism in government – Europe and Latin America. Moreover, responding to Wolff's (Reference Wolff2018) plea that research on the patterns of backsliding and autocratization should not only focus on electoral and liberal aspects of democracy, we also explicitly consider potentially positive developments in terms of egalitarianism and participation.

Our results indicate that, on average, populist governments tend to erode the levels of electoral, liberal and deliberative democracy. However, we were not able to corroborate any of the theoretically expected corrective of populism with respect to egalitarian or participatory democracy. Our empirical analysis provides clear evidence that under populist governments – on average – liberalism, deliberation as well as the electoral core of democracy erode. At the same time, populist governments do not live up to their promise of substantially improving and rejuvenating egalitarian and participatory aspects of democracy. On the contrary, the assumed negative association between populism and both the electoral and liberal models of democracy holds across and within the two regions under study, in line with previous findings (e.g., Juon & Bochsler, Reference Juon and Bochsler2020; Vittori, Reference Vittori2021). Our results indicate that the erosive potential of populist rule holds even when controlling for extreme left or right ideology. On a more optimistic note, our results indicate that more mature democracies are less prone to these deteriorating effects of populist rule. The negative consequences of populism are moderated by previously higher levels of electoral, liberal and partially, also deliberative democratic institutions.

Disaggregated results by region, furthermore show a particularly negative association between populism in power and participatory and egalitarian democracy in Latin America. While prominent populist presidents, like Hugo Chávez in Venezuela or Rafael Correa in Ecuador, have been associated with an increase in both the legal provision as well as use of direct democratic mechanisms, we need to be careful with generalizing these case patterns to the overall region. Region specific differences also arise with respect to far‐right extremism. In Europe, we find democratic regressions in all but the egalitarian model of democracy to be negatively affected by far‐right governments (irrespective of their populist or non‐populist nature), while the negative effect of populism in government only holds for the electoral and liberal models of democracy in this region. These findings, in particular, highlight the need to pay attention to and empirically disentangle the implications of both the ‘thin’ populist ideas and the ‘thick’ right‐wing ideology of governments in the region (see Mudde, Reference Mudde2004 and more recently Neuner & Wratil, Reference Neuner and Wratil2022).

While our analyses provide first insights into the multi‐dimensional effects of populism on different facets of democracy, both across regions and time, much more remains to be done. Future research needs to dig deeper into which aspects of the respective models of democracy are affected the most under populist rule. Moreover, while our categorical coding of extreme ideologies precludes us from running more sophisticated models based on our data, a more fine‐grained coding of the ideological leaning of populist and non‐populist governments could yield further insight into the role of ideology as a moderating factor. Finally, while our focus was on chief executives, future research needs to factor in the impact of populism in opposition as well.

Acknowledgements

We particularly thank Anna Lührmann for her contributions to an earlier version of this article. We are also grateful to the three anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and the editors of EJPR for their support throughout the process. We thank participants of the 2018 DVPW congress, the 2019 Annual V‐Dem Conference, the 2019 EUROLAB Authors’ Conference, and the 2019 Team Populism Conference, for their valuable feedback to earlier versions of this article. We thank Lena Günther for her skilful research assistance. This research was supported by Vetenskapsradet [grant number 2018‐016114], PI: Anna Lührmann and European Research Council, Grant 724191, PI: Staffan I. Lindberg, V‐Dem Institute, University of Gothenburg, Sweden as well as by internal grants from the Vice‐Chancellor's office, the Dean of the College of Social Sciences, and the Department of Political Science at University of Gothenburg.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table S1. List of Populist Chief Executives in Europe and Latin America.

Table S2. Descriptive statistics.

Table S3: Populism and Democracy in 47 Countries (1995–2018) – PCSE Models.

Table S4a: Populism and Democracy in 47 Countries (1995–2018) – Models with Alternative 2 Year Lag Structures.

Table S4b: Populism and Democracy in 47 Countries (1995–2018) – Models with Alternative 5‐year Lagged Average.

Table S5: Populism and Democracy in 47 Countries (1995–2018) – Models with Alternative Dependent Variable (Change in Democratic Model).

Table S6a: Populism and Democracy in 29 Western and Central Eastern European Countries (1995–2018) – Fixed Effects Models.

Table S6b: Populism and Democracy in 18 Latin American Countries (1995–2018) – Fixed Effects Models.

Table S7: Populism and Democracy in 47 Countries (1995–2018) – Models with Alternative Dependent Variables (Polity IV & Freedom House).

Table S8: Populism and Democracy in 47 Countries (1995–2018) – Models with Alternative Measure of Populism.

Table S9a: Populism and Democracy in 47 Countries (1995–2018) – Models with V‐Dem model controls.

Table S9b: Populism and Democracy in 47 Countries (1995–2018) – Models with V‐Dem model controls.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information