Introduction

This article investigates a potential manifestation of language contact between Canada’s two official languages, French and English. Our investigation is based on the variety of English spoken in a predominantly French-speaking community, Kapuskasing, situated in a predominantly English-speaking province, Ontario. Recent studies have uncovered noteworthy similarities in the linguistic patterns among Anglophones and Francophones in Kapuskasing when they speak English. Anglophones have high rates of unambiguous there for discourse-pragmatic deixis, which aligns with French discourse particle là (Tagliamonte & Jankowski, Reference Tagliamonte and Jankowski2020). Subject dislocation, which is vigorous in Laurentian FrenchFootnote 1, is rare in English (Auger, Reference Auger1998; Nadasdi, Reference Nadasdi1995; Southard & Muller, Reference Southard, Muller and Oaks1998), but it is a notable feature of the Anglophones in Kapuskasing (Tagliamonte & Jankowski, Reference Tagliamonte and Jankowski2019, Reference Tagliamonte and Jankowski2023). In this article, we build on the findings of these studies by examining the future temporal reference (FTR) system of Francophones and Anglophones speaking English and comparing their variable systems. This area of grammar presents a notable “conflict site” between the two languages, that is, a form or class of forms that differ functionally and/or structurally and/or quantitatively across languages or varieties of a language (Poplack & Meechan, Reference Poplack and Meechan1998:132).

The guiding questions for our study are as follows: What are the characteristics of the FTR system of Anglophones and Francophones in Kapuskasing? Given that earlier research has shown alignments for other variable phenomena in this community, what will the FTR system, with its complex array of constraints, reveal?

Future temporal reference patterns in Laurentian French and Canadian English

Both French and English share a periphrastic future (PF) variant using the verb go (Examples 1a-b) and robust use of one other variant. French uses the inflected future, often abbreviated as “IF” (Example 1c) (e.g., Comeau & Villeneuve, Reference Comeau and Villeneuve2016; Poplack & Dion, Reference Poplack and Dion2009; Wagner & Sankoff, Reference Wagner and Sankoff2011). English uses the modal will Footnote 2 (Example 1d) (e.g., Denis & Tagliamonte, Reference Denis and Tagliamonte2017; Poplack & Tagliamonte, Reference Poplack and Tagliamonte2000; Torres Cacoullos et al., Reference Torres Cacoullos and Walker2009).

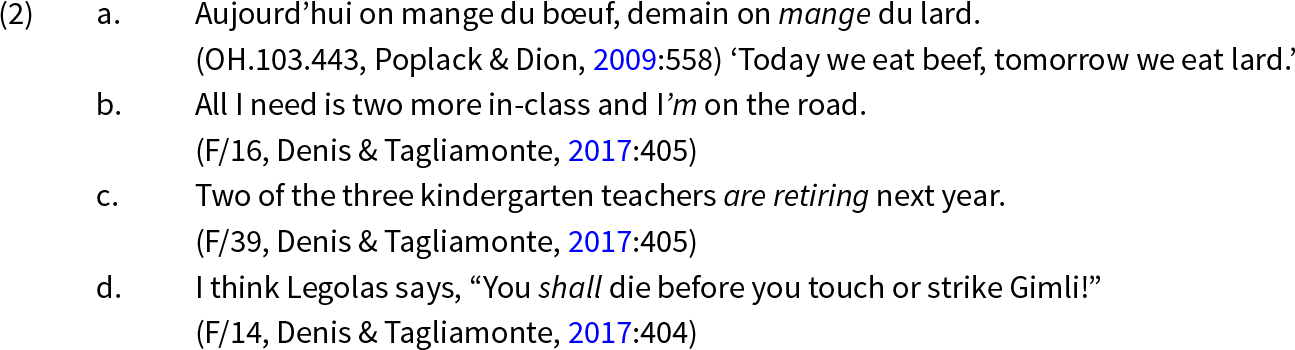

Other FTR variants include a bare present form with no future morphology (Examples 2a-b), a progressive form (Example 2c), and the modal shall (Example 2d) in English, which are also used to express the future, although they generally represent only a small proportion of FTR forms (e.g., Poplack & Dion, Reference Poplack and Dion2009:572; Poplack & Tagliamonte, Reference Poplack and Tagliamonte2000:318).

A systematic review of findings from quantitative studies of FTR in Laurentian French and Canadian varieties of English reveals divergent patterns of variation between the major variants used for FTR. In what follows, we will use the labels “go future” and “will future.”

Rates of usage

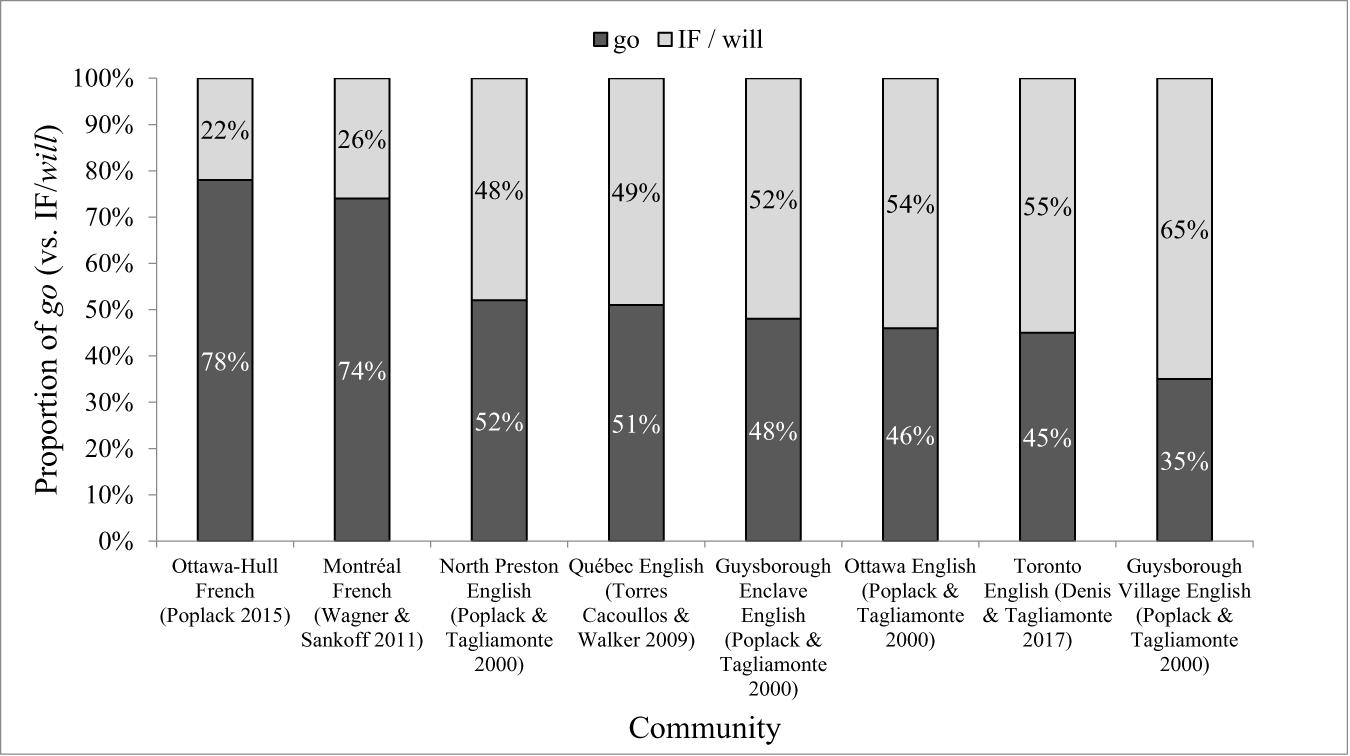

Figure 1 shows the overall rate of go future in French- and English-speaking communities in Nova Scotia, Québec, and Ontario.

Figure 1. Rate of go and IF/will across studiesFootnote 4.

Figure 1 confirms that the rate of FTR variants distinguishes French and English. In Laurentian French, the go future is dominant, used more than three-quarters of the time. Moreover, the preponderance of this variant in French has increased over time; it represented less than two-thirds of the contexts in 19th-century Laurentian French (61%) (Poplack & Dion, Reference Poplack and Dion2009:572)Footnote 5. In contrast, in Canadian English, go and will are used at a similar rate.

Constraints on usage

There are key contrasts among the constraints on variation in the FTR system between French and English. In Laurentian French, the most important constraint on variant choice is whether the future event or state is negative or affirmative: negated future events are almost categorically expressed by the IF. Example (3) from the corpus of French spoken in the Ottawa-Hull area of Ontario (Poplack, Reference Poplack, Fasold and Schiffrin1989) is an explicit demonstration of this pattern: the go future is mainly used, but when the sentence is negative (represented here by the negation adverb pas), IF is used (Poplack & Dion, Reference Poplack and Dion2009:574).

The near categorical effect of negative contexts has been operating since the 19th century in Laurentian French (Poplack & Dion, Reference Poplack and Dion2009). It is also attested among Anglophones speaking French and in close contact with Francophones. Blondeau et al.’s (Reference Blondeau, Dion and Ziliak Michel2014) study, based on the speech of Montreal Anglophones speaking in English (L1) and French (L2), showed distinct underlying systems. When speaking in French, they exhibited the French pattern, where IF tends to be favored in negative contexts. The effect of polarity is also sensitive to competencies in French used in everyday life. Grimm’s (Reference Grimm2015) research on spoken French in Ontario examined the influence of linguistic restriction on the underlying structure of spoken French. His analysis of variation in FTR variants detected a decrease in the effect of polarity as the level of language restriction increased: the less individuals used French in everyday life and the less they used French vernacular forms, the less polarity influenced their choice of FTR variants. Grimm’s results echo what Blondeau and her colleagues have shown: the acquisition of the polarity constraint seems to require that (1) French is spoken in several communicative situations (i.e., not only in school), and (2) vernacular French is predominant.

In Canadian English, studies of FTR report multiple factors operating on variant selection, including sentence type (interrogative sentences favor the go future), clause type (go is favored in subordinate clauses and will is favored in apodosis clauses), and animacy of the subject (will is favored for first-person subjects) (Denis & Tagliamonte, Reference Denis and Tagliamonte2017; Poplack & Tagliamonte, Reference Poplack and Tagliamonte2000; Torres Cacoullos & Walker, Reference Torres Cacoullos and Walker2009). However, there is no difference between affirmative and negative contexts. Thus, the polarity contrast is a key site of conflict between French and English in the marking of FTR.

To summarize, Laurentian French and Canadian varieties of English diverge in patterning with respect to FTR variants in two main ways: (1) the rate of go; and (2) the polarity contrast. Importantly, the French contrast between the IF for negative and the go future for affirmative is apparently easily acquired. Anglophones learning French largely acquire the contrast when learning French. Even among Francophones, the polarity contrast is dependent on French language input. The question is, what do Francophones speaking English do?

Our study is founded in the methodology for establishing the existence and development of linguistic features in language contact by Poplack and Levey (Reference Poplack, Levey, Auer and Schmidt2010). Several studies have already demonstrated that similar structural features between two languages or varieties in contact cannot indicate change without a systematic comparison between the language in contact and the presumed source (Poplack, Reference Poplack and Preston1993; Poplack et al., Reference Poplack, Zentz and Dion2012). They argue that the comparison must consider not only the alternating variants, but also the “linguistic conditioning” present in each of the source languages.

To fulfill this methodological imperative, we employ three data sets. The first is a corpus of the Kapuskasing population: Anglophones and Francophones speaking English, collected in community-based fieldwork. For the comparison with French, we use two different corpora. The first comes from collaboration with a sociolinguistic research project from the same region, the PFC Northeastern Ontario Corpus (Tennant, Reference Tennant2017). The second comes from an informal local podcast. The comparative sociolinguistic analyses of the FTR system compare systematically across these data sets (see Poplack & Tagliamonte, Reference Poplack and Tagliamonte2000).

Methodology

Community and data

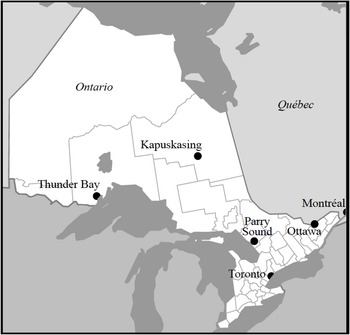

The key body of data consists of informal conversations collected as part of the Ontario Dialects Project, a large-scale documentation project of English dialects in Ontario (e.g., Tagliamonte, 2013-Reference Tagliamonte2013-2018). Kapuskasing, one of the communities in the archive, offers a singular case where both Anglophones and Francophones were interviewed in English, creating a parallel dataset that can probe contrasts between the two heritage groups.Footnote 6 Kapuskasing is situated in northeastern Ontario, approximately 850 km north of Toronto (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Map of Ontario and Québec showing Kapuskasing (adapted from: https://commons.Wikimedia.Org/wiki/File:Ontario_Locator_Map.svg).

Kapuskasing is a majority French-speaking town in a province where French is spoken by only 4% of the overall population. According to the 2016 Canadian census, more than two-thirds of Kapuskasing residents (65%) report French as their mother tongue in addition to having a very good knowledge of English (Statistics Canada, 2017).

Recent research conducted in other northeastern Ontario communities with significant proportions of Francophones has pointed to French influence on English. A study of discourse-pragmatic deixis in Temiskaming Shores and South Porcupine, both with substantial proportions of Francophones, reveals high rates of unambiguous there (e.g., I bought a new guitar there), which is deployed like the French discourse particle là (Tagliamonte & Jankowski, Reference Tagliamonte and Jankowski2020). A study of subject dislocation in the Kapuskasing data (e.g., my dad, he is here) offered further support of French influence on English (Tagliamonte & Jankowski, Reference Tagliamonte and Jankowski2019, Reference Tagliamonte and Jankowski2023). Although subject dislocation is very frequent in Laurentian French (Auger, Reference Auger1998; Nadasdi, Reference Nadasdi1995; Southard & Muller, Reference Southard, Muller and Oaks1998), it is uncommon in Canadian English, presenting an ideal test site to probe English versus French patterns. Findings revealed that when Francophones in Kapuskasing speak English, not only do they employ subject dislocation, but they also exhibit a tendency to use it with human subjects (such as proper nouns) regardless of age. Anglophones in Kapuskasing also use subject dislocation; however, they do not exhibit the same patterns of use as the Francophones except among the youngest individuals (aged 29 and under). Tagliamonte and Jankowski (Reference Tagliamonte and Jankowski2023) argued that this developmental rapprochement is the result of ongoing alignment between Anglophones and Francophones, due to the increasingly high degree of bilingualism in the community, as well as the positive affect ascribed to the French language in the local milieu.

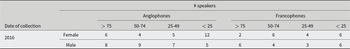

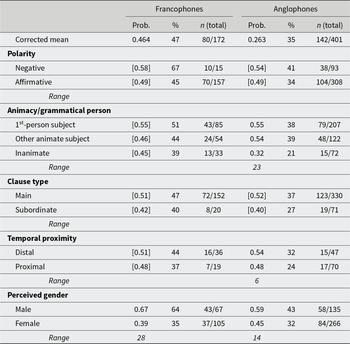

Table 1 shows the Kapuskasing corpus: 93 individuals (56 Anglophones and 37 Francophones) born between 1925 and 2001. All the conversations were conducted using the sociolinguistic interview (Labov, Reference Labov1972).

Table 1. Kapuskasing English sample

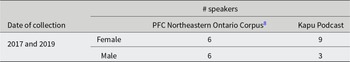

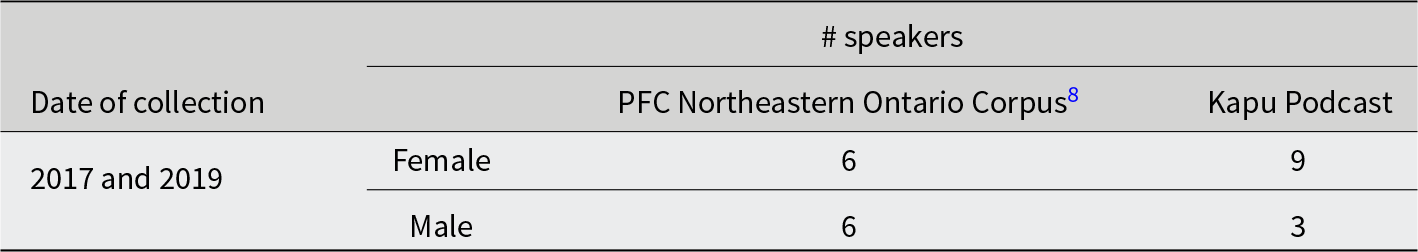

Poplack and Levey (Reference Poplack, Levey, Auer and Schmidt2010) argued that the ideal guideline for systematic comparison with a source language is to have a sample of the comparison variety. To fulfill this criterion, we sought out and gained access to two samples of the French language spoken in Kapuskasing. The first corpus consists of interviews in French collected in 2017 as part of the PFC Northeastern Ontario Corpus, which aimed to document prosodic features of the variety (Tennant, Reference Tennant2017). A total of 12 speakers (six women, six men) born between 1941 and 1997 were recorded in sociolinguistic interviews with a person the speaker knew.Footnote 7 The second corpus consists of interviews from a podcast in French from the Kapuskasing community archives entitled the Kapu Podcast that was broadcast online on YouTube in 2019. The data sample is shown in Table 2. To the best of our knowledge, these two data sets are the only available materials of Kapuskasing French to compare with our Kapuskasing English materials.

Table 2. Kapuskasing French sample

Variationist method

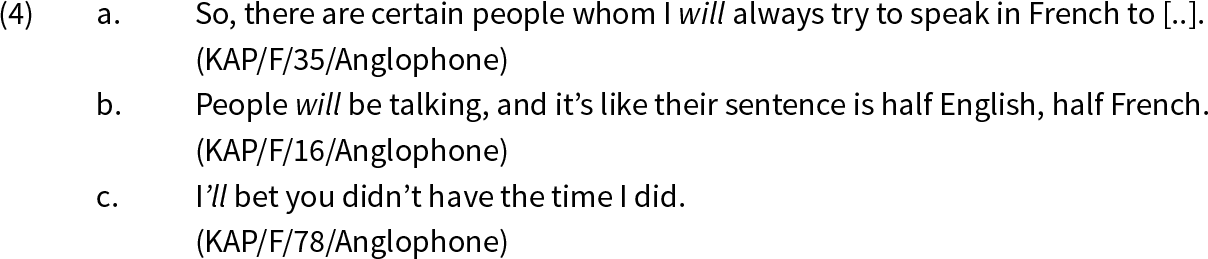

This study draws on the methods and practices of variationist sociolinguistics (Labov, Reference Labov1972; Poplack & Tagliamonte, Reference Poplack and Tagliamonte2001). Consistent with the principle of accountability (Labov, Reference Labov1972:72), we replicated the method developed by Poplack and Turpin (Reference Poplack and Turpin1999:142-146) and Poplack and Tagliamonte (Reference Poplack and Tagliamonte2000:325-326) for the study of FTR. We set aside occurrences that were not part of the variable context, such as habitual actions (Example 4a), gnomic or generic situations (Example 4b), and fixed expressions. Following Denis and Tagliamonte (Reference Denis and Tagliamonte2017), our study specifically looks at variation between go future and will.

Identification and extraction of all variable contexts where there was a choice between go and the modal will to express FTR produced 1,870 contexts.

We tested five linguistic constraints attested in the literature: sentential polarity; subject animacy; grammatical person; sentence type; and temporal proximity. In addition to these constraints, we also considered (perceived) gender and age of the individuals. Each of these constraints is explained in detail in the next section. As mentioned earlier, our focus is on the site of structural conflict between Laurentian French and Canadian varieties of English in the FTR system—the “sentential polarity constraint” (Comeau & Villeneuve, Reference Comeau and Villeneuve2016:235).

Results

In this section, we present a series of analyses aimed at understanding the underlying mechanisms producing FTR variants. We begin with empirical distributions of the variants by context and focus on their use in apparent time. Subsequently, we turn to statistical modeling using the logistic regression in GoldVarb (Rand & Sankoff, Reference Rand and Sankoff1990; Sankoff, Reference Sankoff, Ammon, Dittmar and Mattheier1988) to gain deeper insights into the patterns governing the variation.Footnote 9 We also confirm the results with a mixed effects linear regression (glmer) (Bates, Reference Bates2005) configured to mirror the GoldVarb model. The results confirm the generalized linear model but offer additional evidence by demonstrating that the relevant constraints remain statistically significant when the individual is treated as a random effect.

Distributional analysis

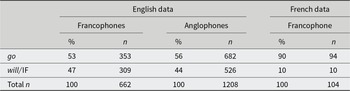

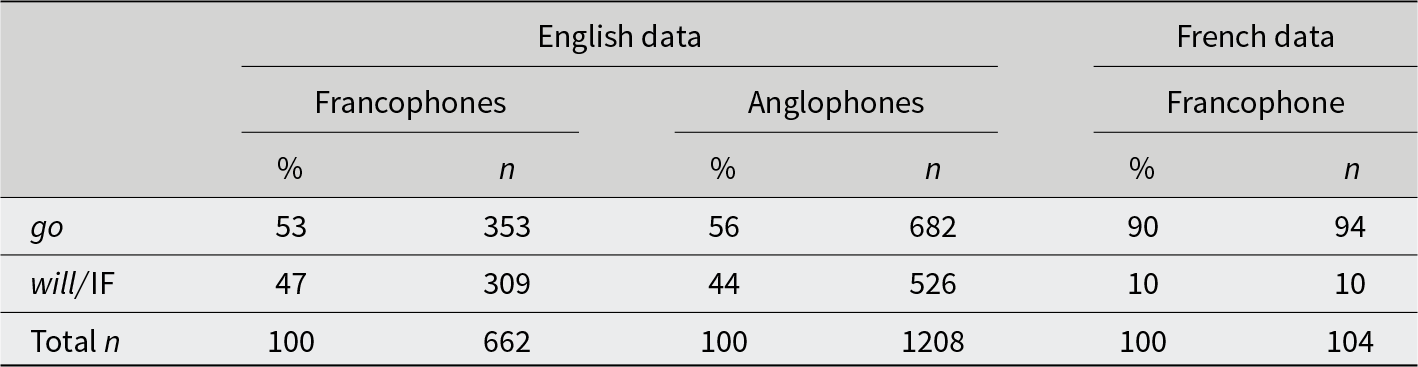

Table 3 presents the overall rate of variants among Francophones and Anglophones in Kapuskasing for the English and French data.

Table 3. Overall rate of variants

In the English data, the FTR variants have the same rate for both heritage language groups, with the go variant being the slightly more common variant. These rates match those reported for other varieties of English (see Fig. 1). In the French data, there is a strong preference for go, exactly what has already been demonstrated in Laurentian French. In the next sections, we consider each of the constraints in turn.

Sentential polarity

As previously mentioned, the polarity of the sentence as negative or affirmative is a significant constraining factor in quantitative studies focusing on FTR. In Laurentian French, this constraint exerts a highly marked effect such that negative sentences are overwhelmingly marked with the IF, while the go future is rare (Poplack & Dion, Reference Poplack and Dion2009; see discussion in Comeau & Villeneuve, Reference Comeau and Villeneuve2016). To operationalize this constraint, all occurrences were coded based on whether they appeared in an affirmative or negative context (Examples 5a-b).

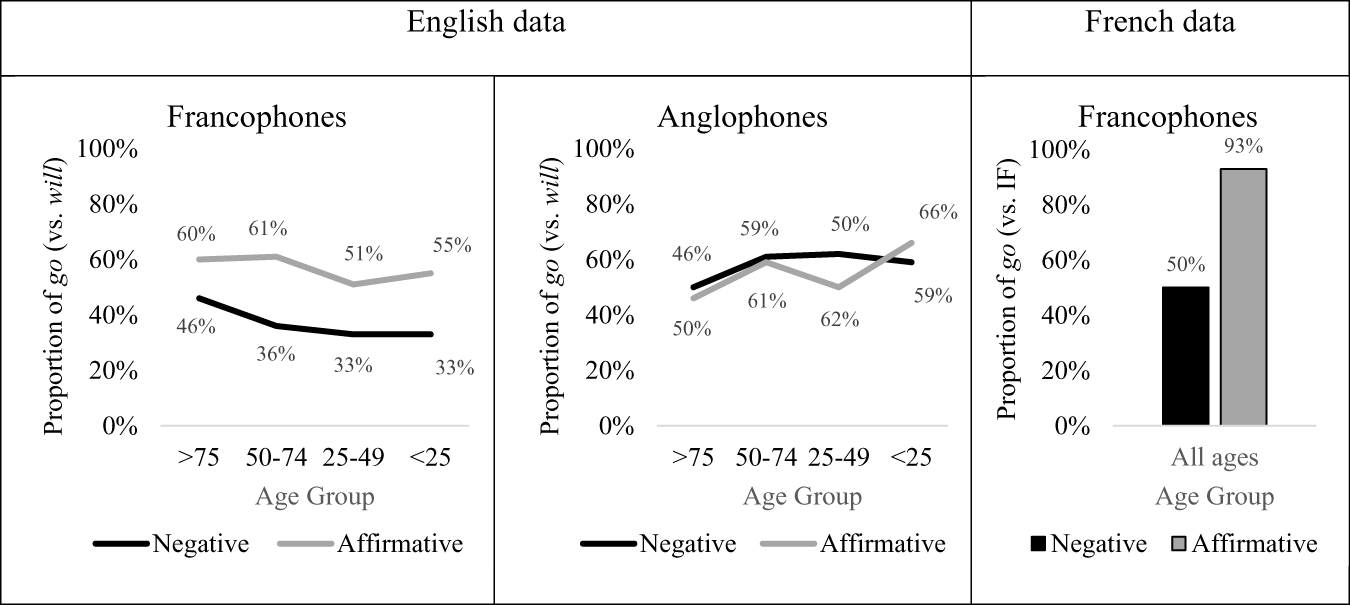

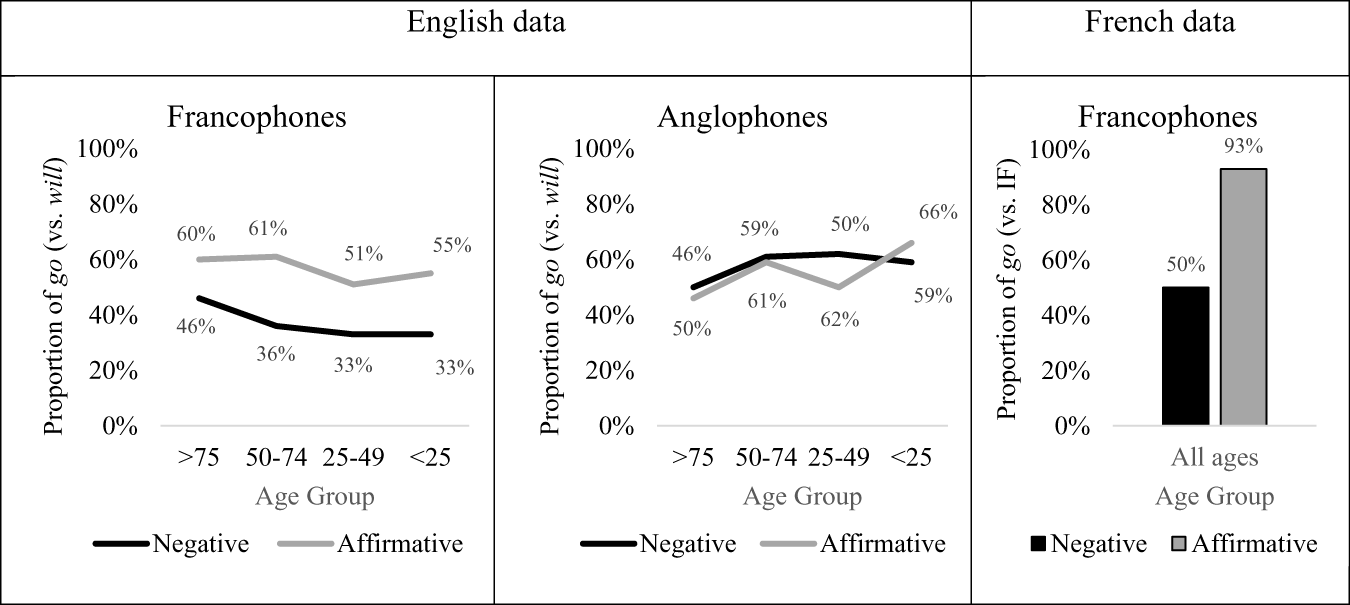

Figure 3 depicts the apparent-time trajectory of go future by polarity.

Figure 3. Rate of go future by sentential polarity.

Figure 3 shows that among the Francophones speaking English, there is a consistent and parallel contrast across all age groups: negative contexts rarely occur with the go future (Example 6), whereas will is the most frequent form in negative contexts.

Among the Kapuskasing Francophones speaking French, the polarity effect is even more strongly present. In contrast, the Anglophones speaking English make no distinction between affirmative and negative, except in the youngest generation. To our knowledge, this is one of the rare demonstrations of the operation of the polarity constraint for FTR among any French population speaking English. Recall that the polarity constraint operated among Anglophones speaking French as an L2, especially those with more exposure to French individuals (see above for references). Thus, the compelling result here is that in Kapuskasing, Francophones, regardless of their age, continue to deploy this well-known constraint of French when speaking in English. In contrast, among the Anglophones, negative contexts are not consistently differentiated from affirmative contexts, and indeed, among older individuals, there is little effect. This result is fully consistent with every analysis that has been conducted on FTR in Canadian English. Moreover, it follows up on the remark made by Torres Cacoullos and Walker (Reference Torres Cacoullos and Walker2009:347) about negative contexts in English, namely that “both [go and will] are viable, as indicated by the lack of a general polarity effect (unlike French, in which the go-future is clearly the default and the synthetic Futur is restricted to negative contexts).” However, there is an intriguing pattern among the younger Anglophones: while those aged 26-49 have fewer go futures in affirmative contexts than negative contexts, those under 25 exhibit the opposite trend. The youngest group has a contrast between negative contexts (59%, n = 55/93) versus affirmative (66%, n = 204/308) contexts that is parallel in direction of effect to the Francophones in the same age group, albeit to a lesser degree. Example (7) illustrates young Anglophones using the future will, that is, won’t, in negative contexts.

In summary, the effect of polarity for FTR variants is consistent across all Francophones when speaking English, regardless of their age. Notably, they are speaking English, but they reproduce the pattern observed among the Francophones speaking French. Among the Anglophones generally, there is no consistent pattern in apparent time for polarity, as would be predicted given all the findings reported for Canadian English. However, the youngest Anglophones mirror the trend visible among all the Francophones: a contrast between negative contexts and affirmative contexts.

Clause type

Clause type has been shown to have a significant effect on the selection of FTR variants in both French (Poplack & Turpin, Reference Poplack and Turpin1999) and English (Denis & Tagliamonte, Reference Denis and Tagliamonte2017; Torres Cacoullos et al., Reference Torres Cacoullos and Walker2009). In French, the go future is less frequent in contexts where the future event contains a hypothetical and unassumed value (i.e., contingent) (see Poplack & Turpin, Reference Poplack and Turpin1999:153 for a discussion of this concept). The same observation has been made in English, albeit to a slightly greater extent than in French, where apodosis clauses of conditionals are not conducive to the selection of the go future. Rather, this variant is favored within subordinate clauses. Researchers have related this observation to the modal origin of will, such that it is favored in contexts that indicate uncertainty, while the association of go with subordinate clauses is due to this context being less volitional and therefore more propitious to go in grammaticalization (Royster & Steadman, 1923/Reference Royster and Steadman1923/1968:400). In parallel with previous studies, we have operationalized this constraint by considering four constructions: main clauses; apodosis clauses; protasis clauses; and subordinate clauses (Examples 8a-d).

Since the apodosis clauses express the consequence of the hypothetical sentence and begin with if, the variants only appear in the following clause. This distinguishes them from protasis clauses, where the variant appears directly after if. As was the case in previous studies, the number of protasis tokens is very low (n = 4), and these contexts are only marked with the go future. We have therefore excluded them from our analysis.

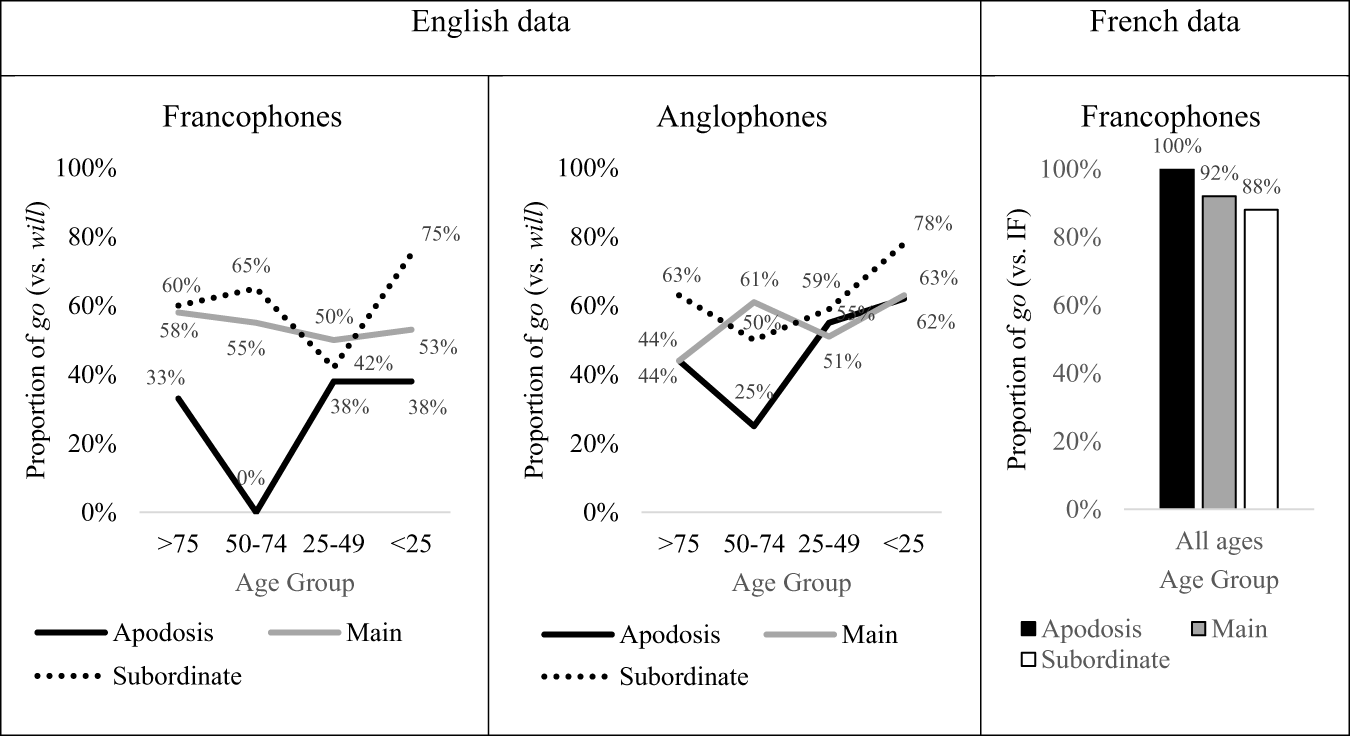

Figure 4 shows the apparent-time trajectory of will by clause type.

Figure 4. Rate of go future by clause type.

Figure 4 shows that there is a recognizable pattern in both heritage languages for most age groups: the go future usually occurs more often in subordinate clauses. The contexts that stand apart are the apodosis clauses, which are mostly marked with will. This result is parallel to what has already been attested in Canadian English. However, the results do not correspond to the French data, where each type of clause constitutes a context conducive to the selection of go.Footnote 10

Although this constraint is not operative in Laurentian French, Denis and Tagliamonte (Reference Denis and Tagliamonte2017) found a pattern contrary to the hypothesis formulated by Torres Cacoullos et al. (Reference Torres Cacoullos and Walker2009), namely that 1PL and other animate subjects rather favor will. They interpreted this pattern as the result of an ongoing encroachment of go future into animate subjects in ongoing grammaticalization.

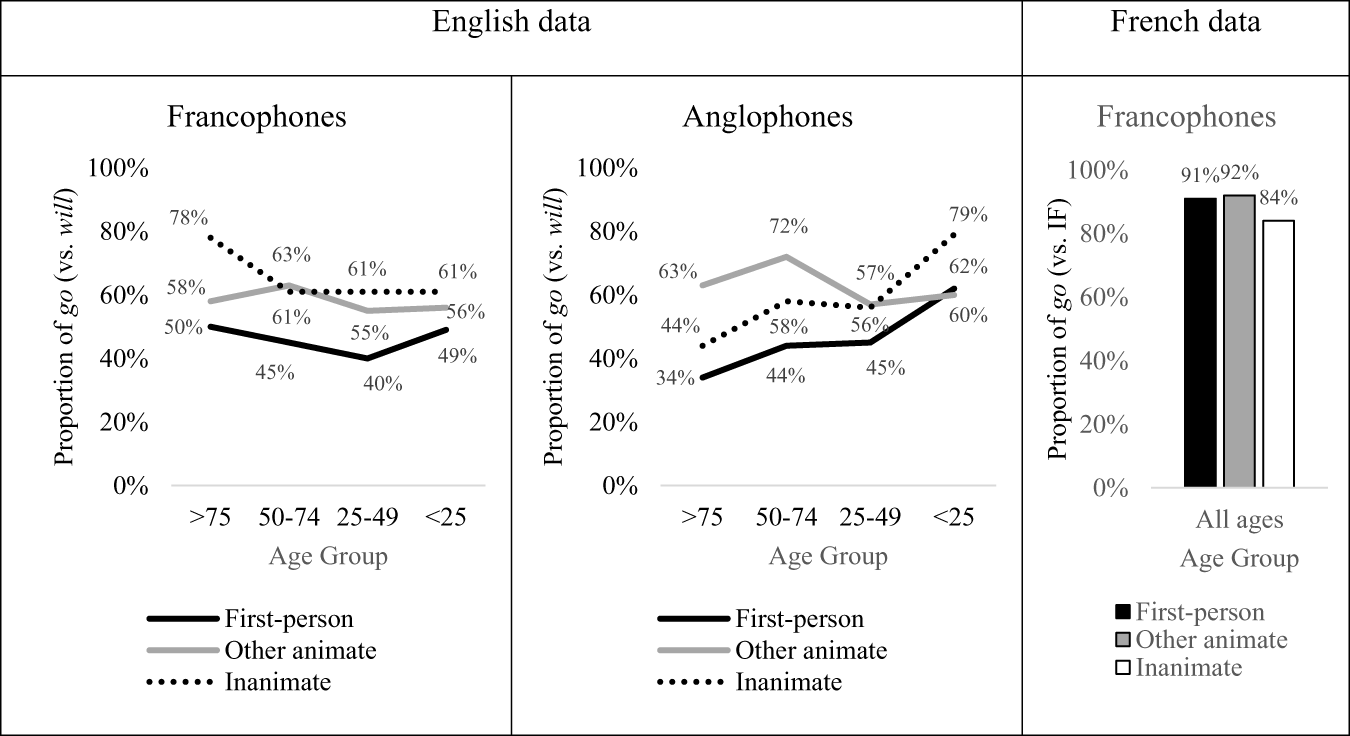

Figure 5 shows the apparent-time trajectory of will by animacy, grammatical person, and the individual’s age.

Figure 5. Rate of go future by animacy/grammatical person.

Animacy and grammatical person

Combining animacy and grammatical person permits testing the effects of volition and intention. For instance, the prior association of the go future with the notion of an “agent on a path toward a goal” predicts that animate subjects would favor the go future (see Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:255, 268; Torres Cacoullos et al., Reference Torres Cacoullos and Walker2009:331) and the hierarchy “first person > second/third person animates > inanimates.” However, as already noted by Denis and Tagliamonte (Reference Denis and Tagliamonte2017) and Torres Cacoullos et al. (Reference Torres Cacoullos and Walker2009), there is an overlap between this constraint and grammatical person, as the first- and second-person plural (1PL and 2PL) are always animate, whereas this is not always the case for the third-person singular (3SG) or plural (3PL) (see Poplack & Turpin, Reference Poplack and Turpin1999). Consequently, we have categorized the data according to three factors: first-person subjects (singular or plural); other animate subjects; and inanimate subjects (Examples 9a-c).

Unlike the two constraints analyzed thus far, there is a parallel pattern across age groups and the two heritage language groups in the English data in Figure 5. The hypothesis that first-person subjects favor will is supported by the results. All age groups for both Francophones and Anglophones, with few exceptions, exhibit the same pattern: first-person has a higher rate of will, that is, I’ll. Anglophones in Kapuskasing replicate a pattern already observed in other varieties of English. However, the trend is reversed in the French data, where all grammatical persons disfavor the selection of will and there is little to distinguish the categories, except that inanimates have the most go.

Temporal proximity

The last linguistic constraint tests for whether temporal proximity in the future plays a role in the selection of FTR variants. As previously mentioned, this constraint has been mentioned for centuries in normative grammars of French and English. It is also often cited in the literature on grammaticalization, where the notion of “purposive movement” is associated with the go future (see Hopper & Traugott, Reference Hopper and Traugott2003:89). Further, what is usually described as the “futur proche” in French is commonly linked to the go future. This constraint is not consistent across varieties of French. It is attested in Acadian French (Comeau, Reference Comeau2015; Comeau et al., Reference Comeau, King, LeBlanc and Jeoung2016; King & Nadasdi, Reference King and Nadasdi2003); however, it does not play a significant role in Laurentian French (Poplack & Dion, Reference Poplack and Dion2009; see discussion in Comeau & Villeneuve, Reference Comeau and Villeneuve2016). In contrast, in Canadian English, the association between the go future and proximate reference in the future is consistently reported as nonsignificant or weaker in influencing variant use.

To test this constraint, we replicated the method developed by Torres Cacoullos et al. (Reference Torres Cacoullos and Walker2009) and coded for eight temporal categories ranging from within a minute (Example 10a) to beyond a year (Example 10b).

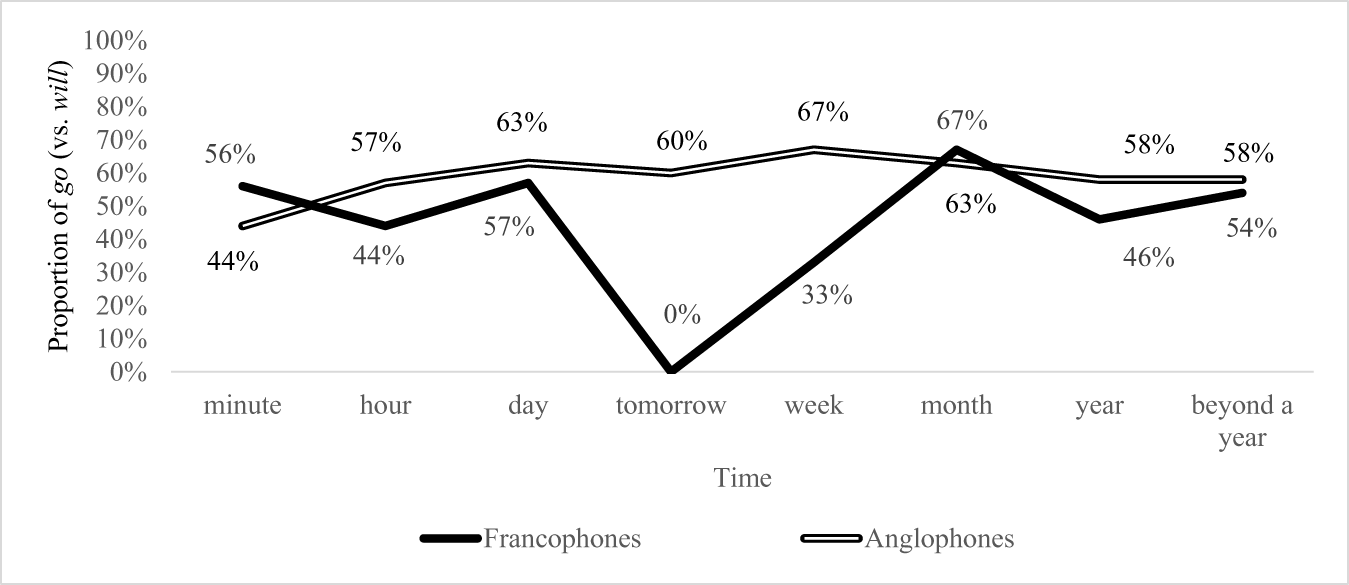

Figure 6 shows the rate of FTR variants by temporal proximity. Note that much of the French data did not have a temporal cue to indicate temporality. As a result, the results presented below relate only to the English data. The Appendix (following the main text) provides token counts for all temporal categories.

Figure 6. Rate of go future by temporal proximity (English data).

The results are once again consistent with what has been reported in Laurentian French and Canadian English: there is no correlation between the selection of variants and the different temporal categories. Francophones and Anglophones in Kapuskasing are in sync.Footnote 11

In addition to the linguistic constraints, we also considered two social factors: (1) age group; and (2) perceived gender.

Age group

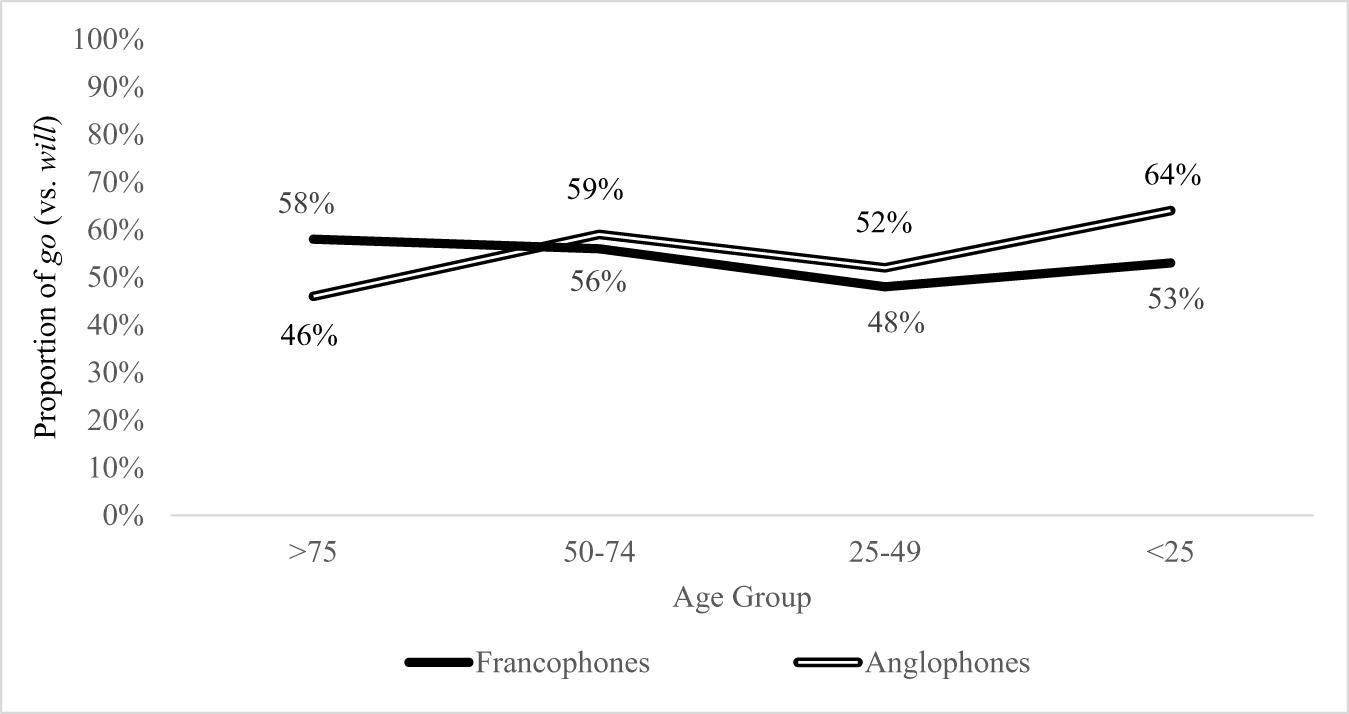

Figure 7 shows the rate of variants in apparent time in each of the heritage language groups. Note that in Laurentian French, the go future has increased in rate in the FTR system over the past century. In the early 21st century, it occurs in nearly three-quarters of the contexts expressing FTR (see above for references). Similarly, in Canadian English, the go future is frequent, at approximately 50% of the FTR sector. Therefore, based on the frequency of usage in both languages, it can be expected that younger Francophones and Anglophones would make more frequent use of this variant, with the possible nuance that Francophones use it more when speaking in English, consistent with its higher level of usage in French. To investigate this, we divided each heritage group into four age groups.Footnote 12

Figure 7. Rate of go future by age group (English data).

Figure 7 shows stability in the go future in apparent time among Francophones, contrary to the trend for the go future in FTR in Laurentian French. In Kapuskasing English, the go future appears to be gaining ground among Anglophones; younger individuals use it more in nearly two-thirds of contexts, unlike what is observed among older individuals—compare 64% to 46%. We will revisit the differences between the two heritage language groups in the section entitled Statistical modeling while placing greater emphasis on comparisons within those four age groups.

Gender

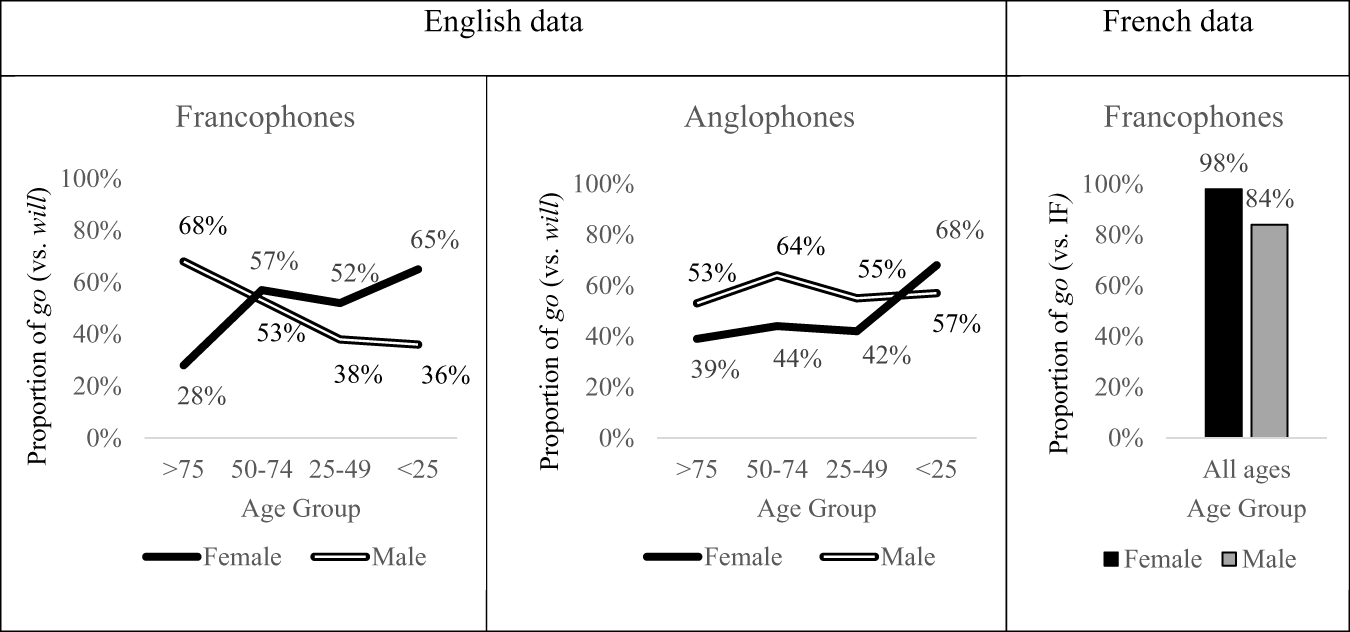

Consideration of gender in earlier studies of Laurentian French and Canadian varieties of English did not reveal a significant effect on the selection of FTR variants. Gender was not significant for French in Ottawa-Hull (Poplack & Turpin, Reference Poplack and Turpin1999) or for the Ontario communities considered by Grimm (Reference Grimm2015). Since one of the objectives of this study was to determine if there is an ongoing change in FTR variants, we considered this constraint based on the consistent finding that women tend to lead ongoing linguistic changes (Labov, Reference Labov1990, Reference Labov2001; see also Tagliamonte & D’Arcy, Reference Tagliamonte and D’Arcy2009). The results are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Rate of go future by perceived gender.

Among Anglophones, Figure 8 shows that there is an ongoing shift toward the go future among younger women. The same trend is visible in the French data: women use the go future more and more. Younger Francophone women are therefore in line with the pattern observed in their mother tongue (see Poplack & Dion, Reference Poplack and Dion2009).

Statistical modeling

Now we proceed with statistical modeling using GoldVarb (Rand & Sankoff, Reference Rand and Sankoff1990), a tool that offers statistical significance (at the 0.05 level) of each constraint in the model, the constraint hierarchy of the factors within each factor group, and a nonstatistical gauge of the importance of these factors or the extent of their influence. Using GoldVarb rather than SPSS or R permits us to make point-by-point comparisons with earlier studies.

Several adjustments to the data were required. We grouped the temporal distance factor group into two categories (distant and proximate) because the number of tokens per temporal category was too low to retain as separate categories in the model. In accordance with previous studies of the FTR in Laurentian French (see references above), the variant we will use as the application value (i.e., the predicted variant) will be future will.

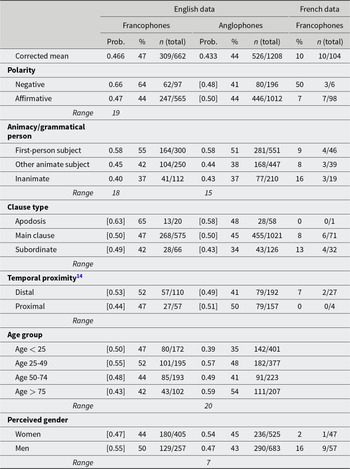

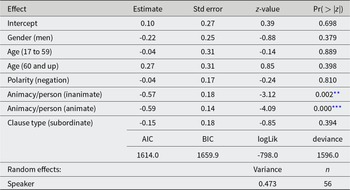

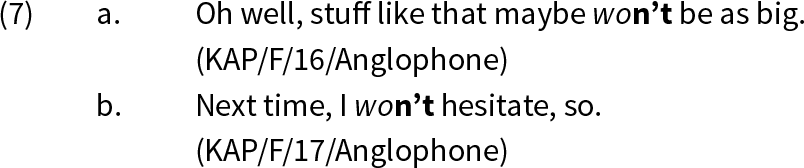

Table 4 shows the comparison between Francophones and Anglophones when all the data for each heritage language are combined.Footnote 13

Table 4. Factors contributing to the use of will/IF

Table 4 shows both contrasts and similarities across the three lines of evidence available in a linear regression model. Among the Francophones speaking English, polarity is significant; among the Anglophones, it is not significant. Moreover, the factor weights show that the effect hovers at the midpoint. The results for the French data, shown on the right of Table 4, display the same trend already observed in Laurentian French, where IF is strongly associated with negative contexts, confirming that among Francophones speaking French in Kapuskasing, there is a strong and parallel effect of polarity.

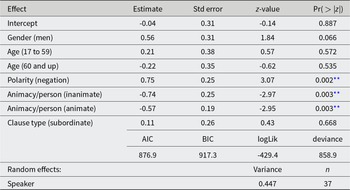

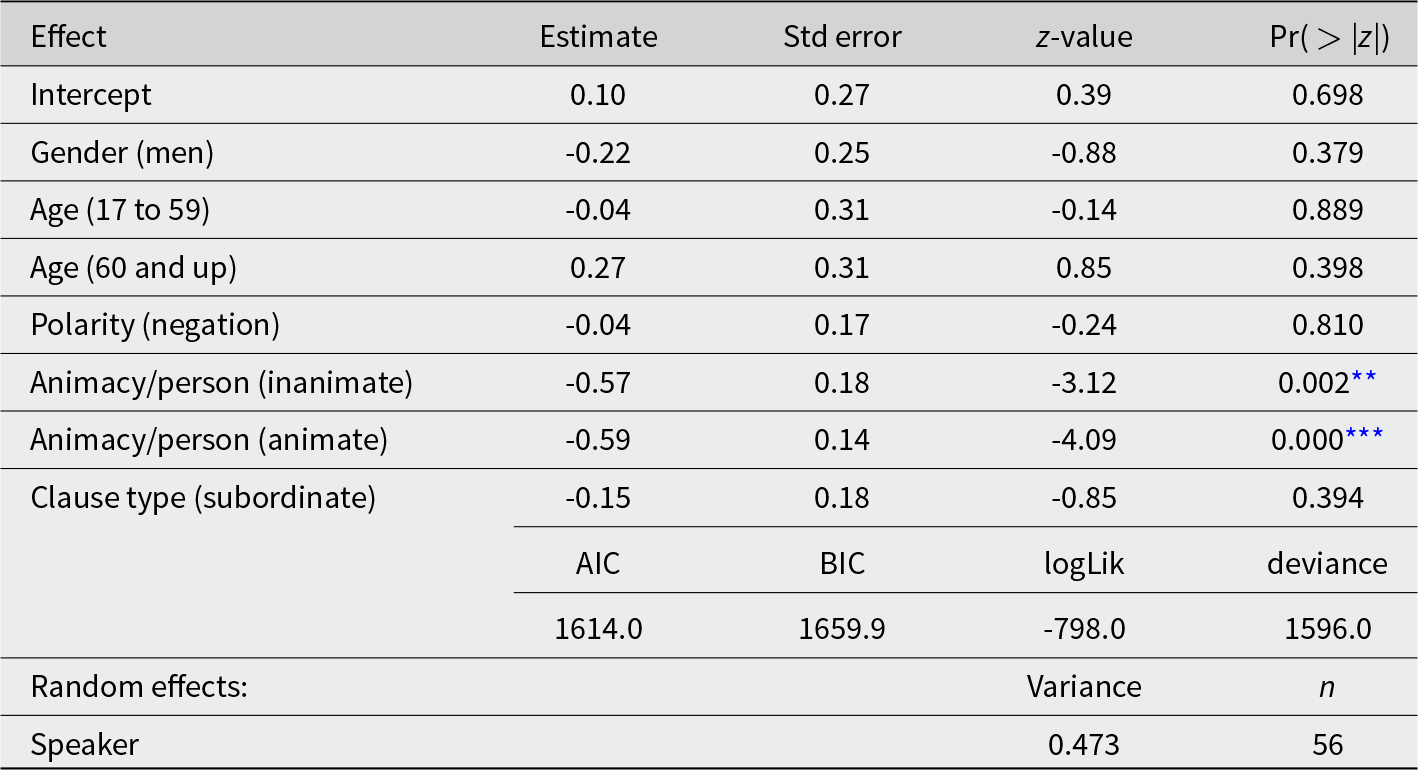

Tables 5a and 5b replicate the same model using a generalized mixed-effects model (glmer) in R (R Core Team, Reference Computing2022). The numbers and rates by cell can be found in Table 4. Tables 5a and 5b indicate the predicted categories with the predicted variables. The reference levels for each factor group are as follows: women; age under 17; first-person; and main clause. In some cases, the categorization of the variables has been modified.

Table 5a. Factors contributing to the selection of will/IF, Anglophones (English data)

Significance codes: 0

“***” 0.001 “**” 0.01 “*” 0.05 “.” 0.1 “.” 1

Table 5b. Factors contributing to the selection of will/IF, Francophones (English data)

Significance codes: 0

“***” 0.001 “**” 0.01 “*” 0.05 “.” 0.1 “.” 1

These analyses add to the building picture by providing a confirmation of the key results for our argumentation—the fact that the polarity effect is not significant for the Anglophones overall, but it is for the Francophones, even when the individual is taken into account as a random effect in the analysis. Moreover, the significant effect of first-person subjects favoring the go future is parallel in both groups.

Francophones speaking English

Recall that in the distributional analysis of the rate of variants in apparent time (Fig. 3), the prevalence of will in negative contexts dominated in each age group for Francophones. The statistical model in Table 4 confirms these empirical results; the effect of polarity is significant at the 0.05 level: will is favored in negative contexts with a factor weight of 0.66 versus 0.47. Polarity is also the strongest constraint among Francophones. The range value is 19, whereas most of the other constraints are not even significant. Animacy/grammatical person is a close second in strength.

Anglophones speaking English

Consistent with the distributional results (Fig. 3), the polarity constraint is not significant among Anglophones. Instead, the age group exerts the strongest effect. While older individuals and those aged between 25 and 49 favor will, the low factor weight, that is, 0.39, for the youngest age group indicates Anglophone youth favor go. Perceived gender is also significant: women favor go; however, the range value for gender is very small, that is, 7. Recall that the difference in rates between men and women was overall very close (45% versus 43%), and Table 4 showed varying trends.

Next, we turn to a comparison across heritage groups for the other factor groups.

Francophones and Anglophones speaking English

The animacy/grammatical person constraint is highly significant in both groups. Moreover, there is a notable parallelism in the constraint ranking. In each group, first-person subjects favor will while the other categories disfavor it. This is the same pattern reported for Canadian English in Toronto (Denis & Tagliamonte, Reference Denis and Tagliamonte2017). In fact, the hierarchy proposed in the literature (“first-person > second/third-person animates > inanimates”) is associated with the choice of variants in the FTR system. In most accounts, will is thought to retain nuances of volition and intention and is predicted to occur more in the first-person; however, in other accounts, the go future is considered the incoming form and thus can be expected to encroach into the semantic territory once held by will. The results in Table 3 support the former prediction: in both heritage groups, will is favored in first-person while other animate and inanimate subjects disfavor it. This contrasts with the findings in Denis and Tagliamonte (Reference Denis and Tagliamonte2017:419, Figure 9), where go is indeed encroaching on first-person contexts. They interpreted this result as being due to ongoing semantic bleaching in Toronto, whereby the go future is increasingly infiltrating animate first-person contexts.

The other two constraints, clause type and temporal proximity (see also Figs. 4 and 6), had no statistically significant influence on variation in either heritage language group. Still, the constraint ranking for clause type is the same between the two groups. Note that although the apodosis context highly favors will, the number of tokens is very low in both groups. Focusing on the two categories with substantial data, there is a notable parallelism between groups. In this case, the direction of effect aligns with what has been demonstrated in Canadian English, where the go future is less propitious in contexts where the future event contains a hypothetical and unassumed value (Denis & Tagliamonte, Reference Denis and Tagliamonte2017; Torres Cacoullos et al., Reference Torres Cacoullos and Walker2009).

Summarizing the results in Table 4, the most important difference between Francophones and Anglophones when speaking English lies in the effect exerted by polarity and age group. Thus, Table 4 suggests that when Kapuskasing Francophones speak English, they not only reproduce the robust pattern for animacy/grammatical person in English grammar, but also show the same hierarchy of constraints for the other internal linguistic factors, as well. The exception is polarity. In this case, the Francophones follow the pattern of their heritage language. The critical result is that this effect is not observed among Anglophones overall in Table 4, but it is visible in Figure 3 among the individuals in the younger age groups, with a key contrast among those under 25 years of age.

Contextualising the results

The English spoken by Anglophones and Francophones in Kapuskasing is distinct in a pointed and circumscribed way. While the Francophones are highly bilingual, and their English is very accomplished, detailed analysis reveals characteristic and unexpected patterns of variation. The two heritage language groups do not treat polarity the same way. Among the Francophones, there is a strong tendency for will in negative contexts. At first glance, this is an important result that aligns well with what we observed with the IF variant in the French data we analyzed, reproducing what has already been attested for Laurentian French (Poplack & Dion, Reference Poplack and Dion2009) and for speakers learning French in a predominantly Francophone context (Blondeau et al., Reference Blondeau, Dion and Ziliak Michel2014; see also Grimm, Reference Grimm2015). In all these studies, the Francophones exhibit a statistically significant contrast that does not exist in English. However, in this study, the Francophones are speaking English. The fact that they alternate between will and go in their English is not remarkable because both are grammatically correct in English. Only the details of the constraints reveal their divergence from Anglophones.

It is especially telling that age group and gender are so divergent in Table 4, pointing to a socially driven reorganization of the FTR system in this community. At the same time, the structural correspondences regarding well-known typological divides—such as animacy, grammatical person, and clause type—are stable among both groups (Comrie, Reference Comrie1981:187-190). The effect of polarity stands out because it is such an important constraint for this comparison. A second important finding is that Table 4 shows a nonsignificant, indeed neutral, effect of polarity among the Anglophones, yet there was a difference found among young Anglophones (Fig. 3). The headline result comes from the fact that this cohort exhibits a notably French pattern: more will in negative contexts in contrast to all the other Anglophones where there is minimal contrast in the other direction, suggesting a change in the constraint ranking in apparent time.

Let us now step out of the ecology of Kapuskasing in northeastern Ontario and contextualize these findings in a social context (e.g., Heine & Kuteva, Reference Heine and Kuteva2005; Poplack & Levey, Reference Poplack, Levey, Auer and Schmidt2010; Poplack et al., Reference Poplack, Zentz and Dion2012; Sankoff, Reference Sankoff, Chambers, Trudgill and Schilling-Estes2002). A consistent finding of all these studies is that morphological and syntactic properties are comparatively resistant to contact-induced change, whereas lexis and phonetics/phonology “constitute the major ‘gateways’ to all the other aspects of contact-influenced change” (Sankoff, Reference Sankoff, Chambers, Trudgill and Schilling-Estes2002:643). In this case, however, we are dealing with morphology and possibly syntax in the comparison, raising the question of how such a pattern could have been transferred.

The comparison in Table 6 partitions the data to include only the under-25-year-olds to build on the findings that younger Anglophones adopt patterns similar to those of younger Francophones in Kapuskasing in earlier studies of discourse pragmatics, specifically, there and subject dislocation (Tagliamonte & Jankowski, Reference Tagliamonte and Jankowski2020, Reference Tagliamonte and Jankowski2023). Given the much-reduced numbers per cell, we made one adjustment to the configuration of the factor groups: apodosis contexts were merged with subordinate clauses to form a binary contrast for clause type.

Table 6. Factors contributing to the use of will (individuals age < 25) (English data)

The results in Table 6 can now be compared across the three measures: (1) statistical significance; (2) constraint ranking; and (3) relative strength of factor groups.

On the measure of significance, Table 6 reveals that there is one parallel factor group, perceived gender. Moreover, there is no parallelism regarding the relative strength of factor groups, either. For Anglophones, the ranking is: animacy/grammatical person > perceived gender > temporal proximity. For Francophones, there is no relative ranking because only perceived gender is significant. This leaves the measure of constraints. Remarkably, every factor group has the same hierarchy of constraints. On this measure, there is consistent parallelism between the two heritage groups in the youngest generation. Yet these factor groups are not significant, so what can be made of the findings?

The models in Table 6 are compromised by low numbers, particularly in the Francophone group. In this unavoidable circumstance, analysts face the reality that a dataset with many tokens will return more significant factor groups than those with fewer tokens. In fact, comparing the results of parallel analyses based on significance alone may simply not be advisable in this situation (see Poplack & Tagliamonte, Reference Poplack and Tagliamonte2001:93). Considering this unsolvable methodological situation, we rely on the empirical distributions and the direction of effect of the factor weights, as well as the findings emerging from triangulating across the various analyses from regression modeling in Tables 4 and 5 and the shared constraint rankings in Table 6.

Synthesizing across the results in Table 6, we suggest that our findings do not indicate a change due to transfer or convergence or even calquing between Francophones and Anglophones in Kapuskasing, but rather, they reflect a trend of “sociolinguistic alignment” between them, consistent with earlier research on this community in other areas of grammar. As argued in this earlier work, the concept of social alignment comes from Goffman (Reference Goffman1967) and accounts for influences that come from interactions between individuals in the social milieu (see also Cheshire, Reference Cheshire, Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Tottie and van der Wurff1998). In the case of Kapuskasing, Tagliamonte and Jankowski (Reference Tagliamonte and Jankowski2019, Reference Tagliamonte and Jankowski2023) have shown that Anglophones in Kapuskasing use forms and patterns akin to French when speaking English. They concluded that the observed patterns of alignment are driven by increasing linguistic, social, and cultural symmetry between Anglophones and Francophones in the speech community, which is reflected in the frequency and patterns of linguistic constraints. Differential sensitivity of individuals to social and cultural aspects of the situation and interlocutor has been reported in other contexts. Of key relevance to Kapuskasing, Weatherholtz et al. (Reference Weatherholtz, Campbell-Kibler and Jaeger2014) showed that individuals adapt syntactic structures to their interlocutors based on shared political ideology, while Kim and Chamorro (Reference Kim and Chamorro2025) demonstrated phonetic accommodation based on social proximity to the interlocutor. These findings, together with the earlier results reported from Kapuasking, lead us to a plausible explanation for the pattern of polarity as relating to the dense, nose-to-nose interaction in the community. We suggest that the local situation allows for a confluence between groups; in this case, a strong categorical pattern in French—a polarity contrast between form and meaning—emerges in English. Whether this is the beginning of an alignment trajectory that could become increasingly pronounced or shift in character in the future remains a question for ongoing research.

For now, we propose that the Kapuskasing community is a singular case that unpacks the forces that drive language trends and social patterns in a unique contact situation. Notably, at the beginning of the 20th century, French was excluded from the public domain. Regulation 17, enacted in 1912, prohibited French in Ontario schools, and this regulation was not repealed until 1944. This led to the mobilization of Francophones in the province to assert their rights and the Ontario government to pass laws guaranteeing services in French in some 20 regions, including Kapuskasing. Since then, French has become much more prevalent in many areas of society, particularly in northeastern Ontario, where Francophones are often the majority population of a community. Taken together, these external developments have had a significant impact on language policy in Ontario in the latter half of the century, which we see here mirrored in usage.

While the FTR system is not a salient nonstandard variable of Canadian French, it is a phenomenon deeply embedded in the Laurentian French grammar with a complex set of internal constraints. Francophones acquire the full spectrum of these patterns, including the polarity effect. Similarly, Blondeau et al. (Reference Blondeau, Dion and Ziliak Michel2014) studied the FTR system among Anglophones in Montreal, a highly Francophone community, and in this case, the Anglophones acquired the polarity effect, and the system faithfully mirrors the French system when they speak French.

A question that arises is why a categorical contrast between negative and affirmative would affect the FTR system of English when, by all accounts, it is not present in the extant system. It might be argued that there is no reason to expect polarity to be concordant across French and English, especially when the variants themselves have no parallelism; in French, the contrast is between an inflection and a periphrastic verb construction, go, while in English it is between a modal, will, and go. However, we know from other studies that the polarity contrast has characteristics of a universal. For example, in comparative studies of default agreement in English, the contrast between affirmative and negative is found to operate in virtually every place where the variation exists even if it does not pivot in the same way (Tagliamonte, Reference Tagliamonte and Siemund2011:20). Across varieties of English, negative contexts are marked by nonstandard default agreement (e.g., there was no boys, the boys wasn’t bad), while standard forms occur in the affirmative (e.g., there were boys, the boys were bad). In fact, research studies are beginning to recognize that variable contexts in one language may well be reflected in variable or categorical contrasts in other, often related, languages (e.g., Bresnan et al., Reference Bresnan, Dingare and Manning2001). Whether these trends can be co-opted from one language to another in language contact situations requires further study, leaving this suggestion speculative; however, it presents a tantalizing hypothesis for future investigation.

We maintain that positive affect and the intense, densely networked interaction with French in Kapuskasing, together with the increasing, positive engagement of young people across the barriers that the French versus English language imposed earlier in the century, have been key factors underlying the linguistic patterns observed in our study.

Conclusion

This research has documented a unique situation of language contact in northeastern Ontario, Canada, and has argued for an explanation of social alignment. Kapuskasing has provided a veritable gold mine for observing how Anglophones and Francophones speak English in an increasingly French-dominant and Francophone-friendly town. Drawing on a unique body of data from a balanced sample of Anglophones and Francophones speaking English, we conducted a systematic comparison with the source language, a benchmark represented by two local representations of French. We examined a grammatical variable with a complex set of system internal constraints—the FTR system—and discovered that on a key point of contrast in variant choice—polarity—Francophones speaking English and French in Kapuskasing consistently employ the polarity effect of French. We also observed the polarity contrast among young Anglophones speaking English in Kapuskasing.

Further studies in communities like Kapuskasing and on other systems of grammar will augment these findings and add to the types of phenomena involved in language contact in similar situations. Another avenue of research would be to seek out other conflict sites where the essential difference in the comparison is a contrast between a (near) categorical constraint and a robust variable one. All in all, we hope that the type of comparable research we have conducted here will serve as a catalyst not only for furthering the understanding of coexisting languages in contexts of bilingualism, but also a harbinger of more positive attitudes toward bilingualism in Ontario and Canada more generally.

Acknowledgements

The second author gratefully acknowledges the support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada for research grants (2001-present), particularly Tagliamonte (Reference Tagliamonte2013-2018), which enabled the data to be collected and archived. We thank the fieldwork team that collected the data in 2016; Julie Latimer, curator of the Kapuskasing Museum; the research assistants of the UofT Variationist Sociolinguistics Lab who collected and transcribed the data; and most importantly, the people of Kapuskasing who agreed to share their stories. We are also very grateful to Jeff Tennant for providing access to the PFC Northeastern Ontario Corpus, Andréanne Joly for her support in helping us gain access to the Kapu Podcast, and Michaël Friesner and Chloe Nguyen for support with the data extraction and coding of these materials. Finally, we thank the two anonymous reviewers and the audiences at ADS, LSRL 52, and SECOL 89 for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Appendix. Rate of go future by temporal proximity (English data)