Introduction

Economic sociology and comparative political economy increasingly focus on the lived everyday experiences of social class and economic change. As part of this broader intellectual movement, many emphasize the link between economic production and social reproduction. This strand of analysis, usually referred to as social reproduction theory has integrated the study of capitalism, class, gender, and care [Bhattacharya Reference Bhattacharya2017; Fraser Reference Fraser2013; Orloff Reference Orloff1996]. This approach highlights how unpaid care and domestic labor are integral to capitalist accumulation yet remain systematically undervalued, thereby reproducing gendered and class inequalities well beyond the sphere of production. These advances have significantly extended the prior scholarship on welfare and care, foregrounding the intersecting hierarchies of class and gender and the ambivalent relationship between markets and reproduction.

Among sociologists and demographers, the wave of “lowest-low” fertility in Southern Europe and East Asia has prompted debates over whether cultural or institutional factors matter most, with many sociologists emphasizing the role of gender equity and supportive social policies. Sociologists argue that fertility stalls when public-sphere gains for women outpace changes in private-sphere caregiving [Goldscheider, Bernhardt and Lappegård Reference Goldscheider, Bernhardt and Lappegård2015; McDonald Reference Mcdonald2000]. Cross-national welfare-state research finds that states offering robust work–family reconciliation measures maintain higher fertility [Esping-Andersen and Billari Reference Esping-Andersen and Billari2015; Oláh Reference Oláh2003]. A parallel line of scholarship links precarious employment and economic uncertainty to delayed or forgone childbearing [Alderotti et al. Reference Alderotti, Vignoli, Baccini and Matysiak2021; Kreyenfeld Reference Kreyenfeld2010].

Building on this budding scholarship, we analyze the unprecedented fertility decline in postsocialist Eastern Europe. We foster a closer dialogue between feminist sociology/political economy and social demography to advance scholarly understanding of the role of commodification in social reproduction. By spotlighting the privatization of once state-owned firms as a catalyst that dismantled company-based care supports, our study illuminates an overlooked way in which broad economic reforms can undermine these institutional bases of social reproduction, thereby potentially contributing to fertility decline.

Postsocialist Eastern Europe offers a uniquely powerful vantage point for analysis. It is home to 15 of the world’s 20 fastest-declining populations [United Nations 2022]. Factors like high mortality, emigration, and low fertility drive this decline. The shift from socialism to capitalism significantly impacted family structures and birth rates. Fertility rates in Eastern Europe hit their lowest in the 1990s and 2000s, falling below 1.3 in many countries [Kohler, Billari and Ortega Reference Kohler, Billari and Ortega2002], a rapid decrease that had been hitherto unseen in peacetime in industrial societies. Figure 1 illustrates this sharp fertility decline in the 1990s, which starkly contrasts with the pre-transition trend. Previously, the fertility rate in the 29 postsocialist countries had been declining gradually and moderately. In Hungary, for instance, fertility remained stable in the 1980s, even rising in the late 1980s, before plummeting in the 1990s [Aassve, Billari and Spéder Reference Aassve, Billari and Spéder2006].

Figure 1 Long-term fertility trends

Notes: The group of postsocialist countries includes all 29 former socialist countries in Europe and Asia (for a complete list of countries, consult Table A4 in the online supplement). Latin America is based on the World Bank’s definition. EU15 is based on the EU’s definition.

The postsocialist fertility decline is contentious [Billingsley and Duntava Reference Billingsley and Duntava2017]. Supporters of the “second demographic transition” hypothesis attribute it to the rise of individualism and the spread of postmodern values [Lesthaeghe and Surkyn Reference Lesthaeghe and Surkyn2002]. The “economic opportunity” perspective suggests that increased employment, education, and consumption opportunities for women raise the “opportunity cost” of childbearing [Perelli-Harris Reference Perelli-Harris2008; Spéder and Bartus Reference Spéder and Bartus2017]. A third viewpoint emphasizes the economic crisis linked to the transition, including income loss, unemployment, and cuts in welfare and family subsidies [Aassve, Billari and Spéder Reference Aassve, Billari and Spéder2006; Billingsley Reference Billingsley2010; Gerber and Perelli-Harris Reference Gerber and Perelli-Harris2012]. Despite extensive research identifying key trends and causes, there is still significant debate over the social factors and mechanisms connecting socioeconomic changes to the decline in fertility [Billingsley and Duntava Reference Billingsley and Duntava2017].

Another influential perspective is gender revolution theory [Goldscheider, Bernhardt and Lappegård Reference Goldscheider, Bernhardt and Lappegård2015], which sees long-term fertility change as a two-stage process: first, rising female participation in education and paid work; second, increased male involvement in domestic and care work. Fertility may dip during the disequilibrium between these stages as care burdens shift without adequate support from institutions or male partners. While this framework helps explain gender-role tensions in advanced economies, it fits less well in the postsocialist context, where abrupt neoliberal restructuring and not gradual norm shifts shaped gender relations [Fodor Reference Fodor2003]. Our paper both builds on and departs from gender revolution theory by showing how care commodification disrupted social reproduction and contributed to fertility decline in Eastern Europe.

Closer to this paper’s argument, several scholars have highlighted the impact of economic uncertainty on fertility decline [Billingsley Reference Billingsley2010; Kohler and Kohler Reference Kohler and Kohler2002; Kreyenfeld Reference Kreyenfeld2010; Kreyenfeld et al. Reference Kreyenfeld, Konietzka, Lambert and Ramos2023]. Qualitative interviews have revealed that Hungarian women were likelier to have children pre-transition, aided by company welfare [Fodor Reference Fodor2003; Tímár Reference Tímár, Rainnie, Smith and Swain2005]. Some evidence suggests that privatization-driven job insecurity might explain the fertility advantage of state-owned firms in Russia [Philipov, Spéder and Billari Reference Philipov, Spéder and Billari2006]. Additionally, strong evidence connects privatization to the postsocialist mortality crisis [King, Stuckler and Hamm Reference King, Stuckler and Hamm2006; Scheiring et al. Reference Scheiring, Stefler, Irdam, Fazekas, Azarova, Kolesnikova, Köllö, Popov, Szelényi, Marmot, Murphy, McKee, Bobak and King2018].

Researchers agree that privatization without solid institutional support leads to various economic and social problems (for an extensive review, see Ghodsee and Orenstein Reference Ghodsee and Orenstein2021]. As Jens Beckert [Reference Beckert2020: 323] summed up, “Privatization has often failed to generate the expected improvements in efficiency, led to significant job losses, and often jacked up costs for customers,” all of which have played a crucial role in neoliberalism losing its “promissory legitimacy.” However, the impact of privatization on childbearing remains unexplored. Many aspects are still unclear, particularly the broader economic factors behind the postsocialist fertility drop. The experience of privatization was a defining feature of the 1990s and 2000s, and thus it is surprising that it has been overlooked in fertility studies.

Indeed, as Figure 2 shows, a negative correlation (r = –0.42) appears between mean privatization and mean fertility rates across 29 postsocialist countries in the period 1989–2012, hinting at a region-wide phenomenon. Yet the mechanisms behind this association remain poorly understood. This study aims to fill this gap by examining how privatization commodified care and social reproduction, thereby potentially contributing to lower fertility rates.

Figure 2 Privatization and fertility 1989–2012, country averages

Notes: Unadjusted correlation between privatization and fertility in postsocialist countries (N = 29). Average privatization measures the mean of the EBRD privatization index for each of the 29 postsocialist countries across the years. Average fertility is the mean of the total fertility rate for each country across the years.

Understanding the relationship between privatization, commodification, and childbearing is vital for at least three reasons. First, at the time of writing, more than 30 years after the collapse of socialism, there is renewed interest in evaluating the overall social balance of the economic transition [Ghodsee and Orenstein Reference Ghodsee and Orenstein2021]. Our study directly contributes to this discussion by providing a novel account of the lived experience of privatization. Second, below-reproduction fertility has emerged as a central political topic. Right-wing populists frequently exploit fears of population decline to gain an electoral advantage [Franklin and Ginsburg Reference Franklin and Ginsburg2019; Melegh Reference Melegh2016], often even supported by some women’s organizations [Molnár Reference Molnár2016]. Third, studying the privatization-commodification-fertility mechanism offers new insights into the limitations of voluntary corporate social responsibility (CSR) to improve work–life balance [Sánchez-Hernández et al. Reference Sánchez-Hernández, González-López, Buenadicha-Mateos and Tato-Jiménez2019]. State-socialist companies were legally obliged to provide welfare functions, which might be a more effective means of socializing the costs of social reproduction than voluntary CSR.

This study contributes to the political economy of social reproduction by introducing a new theoretical model and mixed-method evidence linking privatization to fertility trends. We contribute to social reproduction theory in two ways. First, integrating different bodies of literature across disciplinary boundaries, we develop a mid-range theoretical framework, thereby addressing the issue of high abstraction common in social reproduction theorizing. Second, we shift the focus from the usual Western contexts to Eastern Europe. Although the scale of privatization in Eastern Europe in the period under study was unique, it offers valuable theoretical insights into commodification’s role in fertility decline and how company-level policies can mitigate this. This is crucial for postindustrial societies facing public-sector cuts and the inadequacy of CSR and private care services in helping citizens to balance work and family life.

We proceed as follows. Relying on social reproduction theory, we argue that privatization catalyzes commodification, which increases work intensity and uncertainty and erodes collective resources for social reproduction, thereby impacting childbearing. We explore this privatization–childbearing mechanism quantitatively by employing four distinct definitions of privatization across two datasets. First, we analyze the association in 52 Hungarian towns (1989–2006). Next, we explore the details of the mechanism through a qualitative analysis of 82 life-history interviews surveying the lived experience of privatization, which were conducted in four Hungarian towns. Third, we test the generalizability of the Hungarian results by analyzing the privatization–fertility association in 29 postsocialist countries (1989–2012). Finally, we conclude by pointing out the study’s limitations and contributions.

Historical Context and Theory

Decommodification: From the state to companies

Using social reproduction theory, we demonstrate that company-level decommodification can impact on fertility outcomes [Bhattacharya Reference Bhattacharya2017; Fraser Reference Fraser2013; Orloff Reference Orloff1996] by highlighting how state-socialist companies helped decommodify social relations, thereby contributing to easing the costs of childbearing [Ghodsee Reference Ghodsee2018]. Social reproduction theory is situated in the tradition of economic sociology and political economy. According to this tradition, economic interactions can only be explained by analyzing the “institutional structures, social networks, and horizons of meaning within which market actors meet” [Beckert Reference Beckert2009: 247]. Intimate relationships and the family are crucial sources of these meanings and institutions. Social reproduction involves regenerating “capacities to create and maintain social bonds, including socializing the young, building communities, and reproducing shared meanings and values” [Fraser Reference Fraser2014: 542]. This “relational work” connects intimate and economic realms through establishing, maintaining, reshaping, and sometimes ending differentiated social ties [Zelizer Reference Zelizer2005: 35].

Capitalism tends to “expand into, impose itself on and consume its non-economic and non-capitalist social and institutional context, unless contained by political resistance and regulation” [Streeck Reference Streeck2012: 1]. However, markets alone cannot “produce” workers. Without families and communities, people would struggle to survive, let alone reproduce in sufficient “quantity and quality” to sustain a labor force. As Streeck [Reference Streeck2012: 9] notes, “the marketization of human labor power has reached a point where the physical reproduction of rich societies had to become a public concern.” There is a fundamental tension between the logic of markets and the logic of sustaining the labor force on which markets depend. Social reproduction—largely carried out by families, especially women—generates “free” public goods that are essential to production. Yet capitalist societies undervalue this work, recognizing its importance only when it is commodified.

The commodification of care is inherently contradictory. Commodified care services may lessen the double burden of care and work for affluent women, but this is not feasible for the majority, who lack the resources to outsource care [Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen2009]. Moreover, the private care market often employs precarious workers, like migrants or minorities, who are burdened with the double role of caregiving both outside and within their families. Formal and informal care work in Western Europe is a widespread survival strategy among precariously employed Eastern European women. Thus, at best, commodified care only partially addresses social reproduction challenges.

The inadequacy of market-based care makes decommodification vital for social reproduction [Streeck Reference Streeck, Coulmas and Lützeler2011]. Socializing care work, creating institutions fostering gender-equal caregiving, and ensuring that workplaces are family-friendly can help balance economic production with social reproduction. This reduction in role conflict alleviates the financial and logistical burdens of childrearing, potentially increasing fertility [Esping-Andersen and Billari Reference Esping-Andersen and Billari2015; Oláh Reference Oláh2003]. For instance, Denmark’s universal childcare provision raised its fertility rate from 1.5 to 1.8, a notable impact [Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen2009: 87].

Research indicates that public-sector employment in postindustrial nations positively influences childbearing. Women in public-sector roles are likelier both to have children [Sinyavskaya and Billingsley Reference Sinyavskaya and Billingsley2015] and to return to work post-birth than their private-sector counterparts [Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen, Esping-Andersen, Gallie, Hemerijk and Myers2002; Okun, Oliver and Khait-Marelly Reference Okun, Oliver and Khait-Marelly2007]. Scholars suggest public employment boosts fertility by reducing economic insecurity and offering more family-friendly workplaces. Scandinavia’s fertility rise from the 1970s to the 2000s aligned with public-sector growth [Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen, Esping-Andersen, Gallie, Hemerijk and Myers2002: 75]. These findings inform our theory on the links between privatization, commodification, and fertility decline.

Decommodification as a critical aspect of social provisioning gained prominence with Esping-Andersen’s work on the worlds of welfare capitalism [Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990], and was a crucial aspect of state socialism [Hann Reference Hann2018; Szelényi Reference Szelényi1989; Szelényi Reference Szelényi, Mendell and Salée1991; Ziółkowski et al. Reference Ziółkowski, Drozdowski, Baranowski and rae2022]. Until 1989, despite some market-oriented reforms, the market remained secondary in the socialist bloc. State socialism did not abolish markets but significantly limited their role. State-provided public goods and employment guarantees were crucial in decommodifying social relations. State-socialist companies further supported decommodification by offering less intense work environments, reduced uncertainty, and more collective resources than capitalist firms.

Eastern Europe’s economies were initially agrarian capitalist economies with emerging industrial sectors. By the late nineteenth century, free wage labor prevailed, even in agriculture, with labor, capital, goods, and services primarily market-allocated. This shifted under state socialism, which made market allocation secondary. Additionally, state-run companies shielded domestic social relations from the capitalist world economy’s market pressures. While state-socialist economies engaged in global capitalist markets through trade and financial interactions and exporting goods to Western markets, they largely prevented these external market forces from impacting domestic social relations.

Across socialist Eastern Europe, companies had multiple welfare functions [Schmidt and Ritter Reference Schmidt and Ritter2013: 47–50], acting as “micro-welfare states” [Teplova Reference Teplova2007: 289]. For instance, a 1977 Hungarian law outlined that socialist enterprises should foster workers’ socialist lifestyles, literacy, and professional and political knowledge and cater to their welfare and cultural needs [Sárközy Reference Sárközy1981: 36]. Similar regulations were in effect in all socialist countries. Soviet companies allocated about 3–5% of GDP to social provisions. Firms in Eastern Europe outside the Soviet Union spent roughly half that amount, but this was still considerable and was on a par with the Hungarian government’s family policy spending in the 1990s [Cook Reference Cook2007: 39–40].

Most decommodifying functions in state-socialist companies were either universally mandated or informally adopted to support women’s labor-market integration. Socialist states emphasized gender equality and women’s employment [Einhorn Reference Einhorn1993; Teplova Reference Teplova2007], achieving higher female employment rates than Scandinavia at that time. State-socialist companies were instrumental in this, with laws protecting pregnant workers from dismissal and ensuring their job security post-maternity leave. Working mothers with more than two children received salary supplements. For example, in Bulgaria and Czechoslovakia, this amounted to 40% of the minimum wage [Metcalfe and Afanassieva Reference Metcalfe and Afanassieva2005: 399]. Additionally, many state-socialist companies informally provided young mothers with flexible work options.

To boost women’s employment, the Soviet Union rapidly expanded childcare facilities, primarily managed by factories, collective farms, and cooperatives, starting in the 1920s. Kindergarten numbers soared twelvefold, from 2,100 in 1928 to 25,700 by 1935 [Teplova Reference Teplova2007: 287], at which point they were catering to around 1.2 million children. By the late Soviet era, about 84% of children over three attended these company-organized childcare institutions [Teplova Reference Teplova2007: 293]. These centers often operated for 12–14 hours daily and were vital in arranging summer camps and daycare services.

In the Soviet Union, companies were key in welfare provision, while in other regions, like Hungary, they played a lesser though still important role. The 153rd decree of the People’s Economic Council, passed in 1950, mandated companies with over 250 female employees to create kindergartens for their workers’ children [Aczél Reference Aczél2012: 41–42]. These facilities served as vital social policy tools, providing nourishment and early education and supporting women’s employment. Anna Ratkó, the first minister responsible for social policy and health in Hungary and the country’s first female minister, encapsulated the socialist government’s approach in the following statement:Footnote 1

We, working mothers, understand the importance of nurseries and daycare centers. In 1938, I had to leave my daughter at home, relying on the neighbors’ benevolence. As she began walking, my challenges grew. I worried constantly at work, fearing for her safety. This was our common problem, the problem of every working mother. Our people’s democracy aims to free working mothers from this worry, enabling their full participation in productive employment [quoted in Aczél Reference Aczél2012: 42–43].

During the 1960s in Hungary, local councils assumed control of most company-run kindergartens and their social services. Nevertheless, around 400 company-based kindergartens were still operating in the 1970s [Aczél Reference Aczél2012: 43], a notable figure given that Hungary had 277 towns with populations over 5,000 in 2010. These company kindergartens accounted for approximately 10% of all such facilities in the country during the 1970s [Inglot, Szikra and Raț Reference Inglot, Szikra and Raț2022]. Even after the local councils had taken charge, state-socialist companies continued to support these kindergartens as “patrons.”Footnote 2

While state-socialist countries made important strides in decommodification, they were far from a paradise for female workers due to persistent patriarchal norms and inequalities. Decommodification alone is insufficient for women’s emancipation without defamilization—reducing dependence on the family for social reproduction [Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1999; Lohmann and Zagel Reference Lohmann and Zagel2016]. Nevertheless, market reforms exacerbated these issues [Ghodsee Reference Ghodsee2019: 520]. As privatization elevated the market’s role, companies’ welfare functions became unsustainable. Some were absorbed by state and local government or maintained through CSR, but most disappeared. This retreat contributed to Eastern Europe’s drop in human development rankings [Meurs and Ranasinghe Reference Meurs and Ranasinghe2003], with fertility decline as a key marker of this “de-development.”

Privatization, commodification, and fertility decline

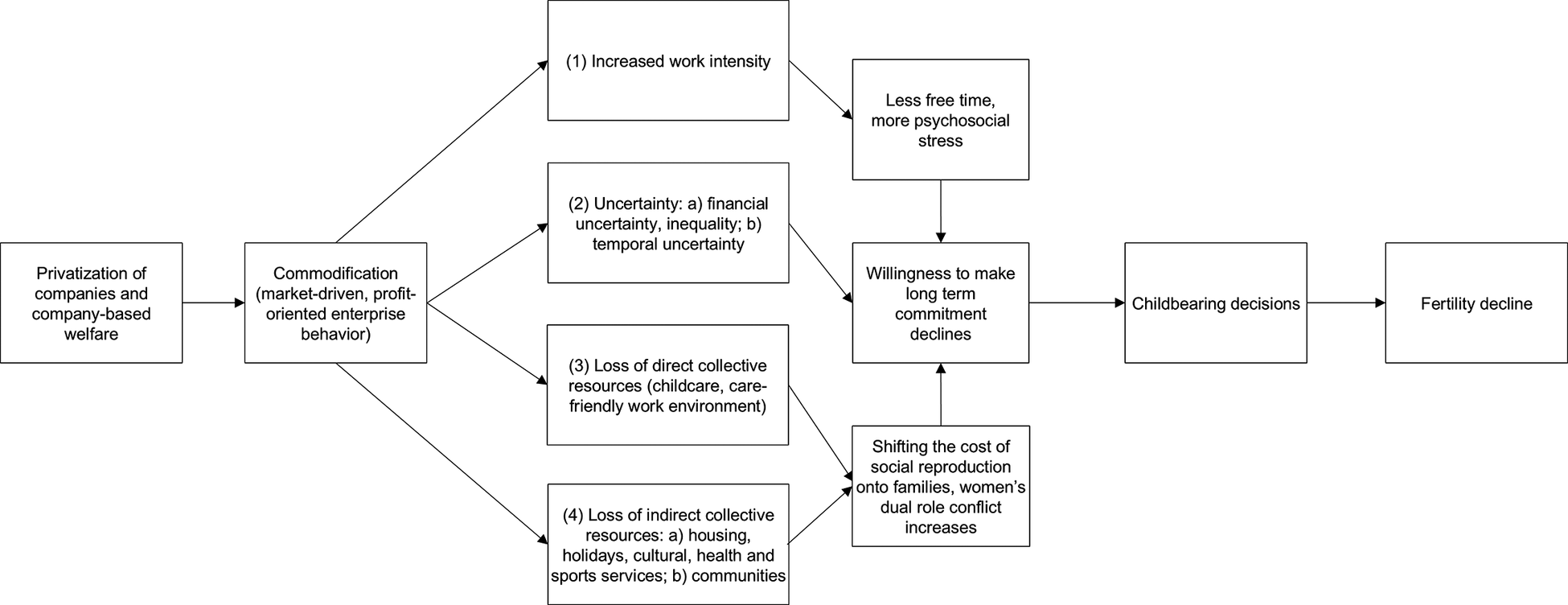

Our theory posits that the privatization of socialist companies results in a fertility decline by commodifying the company functions that had previously balanced economic production and social reproduction. Following Marx, Polanyi, and Esping-Andersen, we view commodification as transforming nonmarket entities into marketable commodities, thereby drawing them into the logic of cost-effectiveness. Figure 3 provides an overview of the mechanism.

Figure 3 The commodification of social reproduction and childbearing

Based on existing research, we propose four pathways connecting privatization to childbearing. First, the primary rationale for privatization is to enhance company efficiency, often by reducing overstaffing [Savas Reference Savas2000]. This leads to employees taking on more roles, which increases job strain, reduces free time, and elevates psychosocial stress. The evidence suggests higher levels of job satisfaction in Ukraine’s state-owned companies than in privatized ones, which might be related to increased stress and workload in the latter [Danzer Reference Danzer2019]. Such stress impacts childbearing decisions. Heightened time pressure lowers childbearing intentions, especially when childcare is scarce [Begall and Mills Reference Begall and Mills2011]. Psychosocial stress has also been linked to male infertility [Nargund Reference Nargund2015].

Second, privatization might increase job instability and income inequality, heightening financial and temporal uncertainties that influence long-term family planning. Privatization correlates with growing income disparity [Bandelj and Mahutga Reference Bandelj and Mahutga2010; Beckert Reference Beckert2020], making incomes less predictable, which leads to lower fertility [Cherlin, Ribar and Yasutake Reference Cherlin, Ribar and Yasutake2016]. Although it may eventually lower unemployment [Brown, Earle and Telegdy Reference Brown, Earle and Telegdy2009; Cuadrado-Ballesteros and Peña-Miguel Reference Cuadrado-Ballesteros and Peña-miguel2018], privatization initially causes job uncertainty and losses [Stošić, Redžepagić and Brnjas Reference Stošić, Redžepagić, Brnjas, Zubović and Domazet2012]. Evidence suggests that private-sector employees in postsocialist Russia have greater perceptions of job insecurity than public-sector employees, particularly women [Linz and Semykina Reference Linz and Semykina2008]. Such uncertainties delay family planning, as educated women postpone parenthood due to employment instability [Kreyenfeld Reference Kreyenfeld2010]. A recent meta-analysis confirmed insecurity’s negative impact on childbearing rates [Alderotti et al. Reference Alderotti, Vignoli, Baccini and Matysiak2021]. Privatization also often results in irregular work schedules, which complicate care arrangements and thus affect childbearing intentions [Harknett, Schneider and Luhr Reference Harknett, Schneider and Luhr2022]. In contrast, the availability of stable public-sector jobs boosts fertility by providing working conditions and support that incentivize childbearing [Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen, Esping-Andersen, Gallie, Hemerijk and Myers2002].

Third, privatization leads to a loss of direct collective resources like childcare and care-friendly work environments, shifting these responsibilities onto families. We label these collective resources “direct” because they are directly related to childcare. All the countries in the Soviet bloc we studied maintained an extensive network of public services that socialized the burden of care. These institutions became unsustainable after privatization. For example, in Russia, the number of childcare institutions fell from 87,900 in 1990 to 53,300 in 2000, with child attendance dropping from 84% in the late socialist period to 47% by the mid-1990s [Teplova Reference Teplova2007: 292–93]. While East-Central European countries managed childcare transitions better, partly due to the earlier nationalization of company-based facilities, they still saw a significant decline in nursery coverage [Saxonberg and Sirovátka Reference Saxonberg and Sirovátka2006]. The municipalities that took over welfare services from state companies faced fiscal challenges. This often led to a decline in service quality, including insufficient infrastructure investment, elimination of free school meals, and shortages of basic supplies [Meurs and Giddings Reference Meurs and Giddings2006]. These changes amplified women’s informal care burden (for example, by requiring them to spend more time on preparing meals).

Although privatized companies discontinued care services, state-owned, nonprivatized enterprises were more likely to offer childcare [Teplova and Woolley Reference Teplova and Woolley2005]. Privatization also led to less support and flexibility for working mothers, hindering their return to work after maternity leave [Glass and Fodor Reference Glass and Fodor2011]. Although Hungarian law protects the right to return to work, this has become a subjective, unequal negotiation between employers and working mothers in privatized companies [Fodor and Glass Reference Fodor and Glass2018]. Women in public-sector companies are more likely to resume work after childbirth than those in private firms [Okun, Oliver and Khait-Marelly Reference Okun, Oliver and Khait-Marelly2007], which indicates that public-sector employers provide a more supportive environment for balancing work and family life.

Fourth, privatization erodes the indirect collective resources vital for social reproduction, including housing, holidays, and cultural, health, and sports services. We label these resources “indirect” because they are not directly related to childcare but are nevertheless crucial to managing the burden of social reproduction. After privatization, families bore the burden of housing costs, which often led them into significant debt. During the period of China’s economic reforms in the 2000s, cities with more affordable housing showed higher fertility [Pan and Xu Reference Pan and Xu2012].

State-run companies also facilitated the emergence of a special kind of informal collective resource: communities and the social capital embedded in them. Services provided by companies, like organizing local theaters or sporting activities, not only helped workers unwind and manage stress but also facilitated the emergence of company-related communities. The socialist brigade movement, a centralized form of volunteerism, also helped nurture social capital. While this social capital was strongly apolitical, it was a vital collective means of coping with the challenges of everyday life, from mutual self-help to caregiving. Privatization fragmented these social structures, disrupting lives and communities, fostering hostility and alienation, and diminishing collective action for decommodification [Burawoy and Verdery Reference Burawoy and Verdery1999; Scheiring and King Reference Scheiring and King2023]. Evidence shows that privatizing company-based communal services like recreation can limit social capital [Swain Reference Swain2003], reducing willingness to cooperate [Champlin Reference Champlin1999]. Researchers have linked this decrease in social capital to Eastern Europe’s fertility decline [Philipov, Spéder and Billari Reference Philipov, Spéder and Billari2006].

By eroding public support systems, privatization also reinforces gendered expectations around caregiving, placing an additional burden on women, which can deter them from having children. This shift in social structures postprivatization reinforces traditional gender norms, impeding women’s dual roles in society and discouraging fertility. Women were often the first to be laid off in privatized industries, and this, together with the loss of collective resources, pushed women back into traditional domestic roles as caregivers. Researchers have documented a widespread re-traditionalization of gender roles in postsocialist Eastern Europe [Fodor and Balogh Reference Fodor and Balogh2010; Gal and Kligman Reference Gal and Kligman2000; Pascall and Manning Reference Pascall and Manning2000]. With reduced access to collective support, women dedicated more time to childcare. In Hungary, the daily childcare time for employed women rose from 70 to 88 minutes between 1986 and 2000, alongside an increase in unpaid work [HCSO 2021]. In Russia, among working mothers with children under seven, the proportion working over 30 hours weekly grew from 65% in 1994 to 72% in 2000 [Teplova Reference Teplova2007: 305]. This surge in unpaid care duties in the 1990s and 2000s heightened the clash between paid and unpaid work across Eastern Europe, which negatively impacted fertility rates [Erikson Reference Erikson2005; Gregor and Kováts Reference Gregor and Kováts2019].

The four pathways discussed—increased work intensity, inequality and uncertainty, and the loss of direct and indirect collective resources—all contributed to processes that directly influenced childbearing decisions and thus fertility. With less free time and more psychosocial stress, couples’ willingness to make long-term commitments decreases. The shifting of the costs of social reproduction onto families increases women’s dual role conflict between family and work, which also reduces their willingness to make long-term commitments. These processes act as disincentives to childbearing and thereby contribute to fertility decline.

Once privatization stabilizes and commodification peaks, its impact on decreasing fertility ceases to intensify. It is not the presence of private markets per se, but the shift toward more commodified company functions that leads to the decline in fertility. Therefore, the fertility recovery in the late 2000s and 2010s does not contradict our theory, as the process of privatization had largely concluded by then. Women and families had begun developing informal strategies to cope with their increased care burden. Additionally, Eastern Europe’s population decline led to the emergence of “demographic nationalism” and new pronatalist policies [Melegh Reference Melegh2016]. Countries like Poland and Hungary implemented “carefare regimes” to encourage higher fertility rates [Fodor Reference Fodor2022].

Despite some differences, ultimately all the ex-socialist states shifted to predominantly private ownership. Central European nations often favored foreign strategic investors; instead, Russia opted for rapid mass privatization, leading to a breakdown of public institutions and state capacity [King Reference King2000]. Regardless of the modalities, privatization was a crucial step in creating capitalism, as it commodified social relations and intensified the tension between economic production and social reproduction. Despite these differences, ex-socialist countries shared commonalities in the 1990s: the transition from state to market, a decline in global economic standing, and deteriorating social metrics [Burawoy and Verdery Reference Burawoy and Verdery1999; Ghodsee and Orenstein Reference Ghodsee and Orenstein2021]. This consistent move from decommodification to commodification suggests that the privatization–childbearing mechanism holds across various privatization models, highlighting its generalizability in the postsocialist context.

Methods

Our study employed a mixed-methods approach, blending different analytical strategies for a comprehensive empirical contribution. Our first empirical strategy relied on statistical methods, analyzing data from Hungarian towns and a broader range of postsocialist countries. Second, we conducted a qualitative thematic analysis of interviews with 82 workers, exploring their personal experiences of privatization. The qualitative analysis concentrated on the “upstream” segment of the causal mechanism depicted in Figure 3. While both qualitative and quantitative methods have their limitations, their combination represents an integrative approach providing unique, substantiated findings, validating our theoretical framework.

Combining town-level and cross-country analyses allowed us to capture both detailed local dynamics and the broader generalizability of the privatization–fertility relationship. The town-level analysis as valuable because it measured privatization closer to where people actually lived and made decisions about whether or not to have children. This brought us closer to the lived experience of individuals. It also helped isolate the role of privatization by holding constant many country-level factors—such as national policies, institutions, and cultural norms—that can vary widely across countries. The cross-country analysis, in turn, enabled us to test the broader applicability of these findings across diverse institutional and demographic contexts. Together, they offered complementary leverage: the former uncovered how privatization plays out in concrete communities, and the latter situated these dynamics within a comparative, systemic perspective. Each level of analysis provided access to unique variables that enrich the study. This combination enhanced both the depth and breadth of our findings.

The qualitative fieldwork added another essential layer by helping us understand how privatization has reshaped everyday life in ways that can plausibly influence childbearing rates. While the interviews did not directly address fertility intentions, for reasons explained below, they shed light on the political-economic pressures that shape such decisions, including increased stress, job insecurity, financial instability, and the erosion of collective resources. This lived-experience perspective aids interpretation of the patterns observed in the quantitative analysis and grounds the broader correlations in concrete social realities.

Hungarian town-level data

Our first empirical strategy relied on quantitative modeling using multiple samples. Analyses relying solely on individual-level data cannot account for contextual factors, such as privatization, which are measurable at enterprise, town, or country levels. Thus, we started with town-level models and then extended this by analyzing cross-country data covering 29 postsocialist countries. We built on the Privatization and Mortality (PrivMort) project, the most extensive effort to study the demographic consequences of postsocialist privatization. The Hungarian data covers the years 1990–2006, during which governments conducted major reforms related to the transition from socialism to capitalism, including privatization. The fully balanced dataset has almost no missing data (<1%).

We collected economic, social, demographic, and health data on 52 randomly selected medium-sized Hungarian towns outside Budapest from the Hungarian Central Statistical Office. We concentrated on medium-sized towns with inhabitants numbering between 5,000 and 100,000 and industrial employment (as a share of total employment) in 1989 exceeding 30% to better isolate the privatization effect. In 2001, 40% of Hungarians lived in such medium-sized towns, so their experience was highly relevant. There are many potential privatized companies in large cities, making data collection difficult. This dataset does not cover all types of settlements, but it represents the most viable empirical strategy that was possible to adopt without sacrificing much external validity. Supplemental Table A1 presents town-level descriptive statistics. To control for common time-varying macro-shocks across towns, we used national-level socioeconomic data from the World Bank and Varieties of Democracy Institute’s V-Dem database. See Table A2 for descriptors.

We linked the town-level data to company-level information from public and private registries. Since digitalized ownership data was unavailable for the early transition years, we obtained this from nondigital archives at local registry courts. To make data collection feasible within the project’s time and financial constraints, we identified the five largest state-socialist companies in the sampled towns in 1989 and collected ownership records for the period 1989–2006. Overall, we analyzed ownership history data from 260 companies, which yielded 550 companies when successor and parent companies were counted separately. From 1989 to 2006, the total number of employees of the five largest companies in each town represented 57.9% of the town-level industrial employment in 1989 on average.

The companies included in our analysis span a range of sectors typical of the state-socialist economy, including heavy industry, energy, chemicals, electronics, and food processing. These firms were often the primary employers in their towns and were embedded in national holding structures that coordinated production and investment across regions. In addition to their economic role, these firms played a critical part in the social organization of life under socialism. Importantly, many of them employed large numbers of women. In fact, it was common for factories in feminized sectors such as food processing or textiles to be situated near male-dominated heavy or manufacturing industry plants. This spatial and organizational arrangement supported dual-earner households and contributed to relatively high female employment rates, especially by international standards at the time.

Even smaller towns often hosted sizable industrial employers, many integrated into national holding companies. For instance, Berhida, with around 5,300 residents in 1990, was home to the Peremarton Chemical Works. Kisvárda, a town of 18,000, had a plant operated by Tungsram, Hungary’s major electronics manufacturer. Martfü, with 7,500 inhabitants, housed the Tisza Shoe Company, and Tab (5,100) had a facility run by Videoton, a leading electronics conglomerate. These were not isolated cases but part of a deliberate socialist strategy to modernize and industrialize small provincial towns. While not every town had a major conglomerate, most featured industrial employers, especially in textiles and food processing, that provided some decommodifying social services.

We created a privatization measure, the primary independent variable, as follows. First, we calculated state and private ownership portions annually for each company. Then, we aggregated company-level data to the town level by calculating average ownership shares across five companies in each town annually. This created annual town-level state and private ownership variables. Our primary independent variable was town-level privatization, measured as private ownership share (0–100%).

Cross-country data

Next, we created a separate cross-country dataset with country-level time-series data. We collected data on 29 postsocialist countries in Europe and Asia, including 15 former Soviet Union members and six Asian countries, while the rest were located in geographical Europe (see supplemental Table A3 for a complete list). We did not include countries that remained formally socialist (China, Vietnam). We focused on 1989–2012 to cover the range of privatization strategies and capture how fertility levels changed over time in different countries. Privatization had run its course by around 2010; therefore, including the years after 2012 would not have added to the analysis.

We obtained data on fertility rates, population, economics, modernization, demographic trends, health, and female opportunities from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators database. We used the country-level fertility rate as the dependent variable. We extended the data with privatization information from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development’s (EBRD) Transition Indicators database, and obtained other control variables from the Varieties of Democracy Institute’s V-Dem database. We assessed the privatization–childbearing mechanism data on tempo-adjusted fertility and mean age of mothers at birth from the Human Fertility Database.

The EBRD has developed small-scale and large-scale privatization indices. The value is one if there is little private ownership and privatization has not yet been implemented. The value is four if 50% of state-owned enterprises are privately owned and if there have been significant corporate governance reforms. Anything above four implies standards of advanced economies: over 75% of formerly state-owned enterprises are privately owned, with effective corporate governance in place. Since what constitutes large, medium, and slight differs across countries and the two indices correlate above 0.9, we calculated their mean as the primary independent variable. Supplemental Table A4 presents country-level descriptive statistics. Major variables have few missing data. However, tempo-related data availability is limited both in time scope (early years are not available) and country coverage (12 countries total).

Modeling and variables

In the Hungarian models, the unit of analysis is the town-year, spanning from 1989 to 2006. We included cases with complete variable information to facilitate cross-model comparisons, yielding 822 town-years clustered in 52 towns. Town-level privatization is the primary independent variable, and town-level fertility rate is the dependent variable. It is reasonable to assume privatization affects birth rates with at least a nine-month lag. Therefore, we lagged privatization by one year.

We included several controls for potential confounding factors and alternative explanations based on the literature. We used population size as the primary control in every model. For the Hungarian analysis, the first fixed-effects model is the baseline, which only includes population size. The second adds economic controls (unemployment, income). The third controls for demographics (migration, infant mortality). The fourth includes public services (kindergarten places, hospital beds, teachers). The fifth model includes all controls.

The final model addresses the influence of exogenous time trends and autocorrelation by additionally controlling for a nonlinear cubic time trend and a lagged dependent variable. We estimated this model using the Arellano–Bond Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) estimator [Arellano and Bond Reference Arellano and Bond1991]. This estimator can mitigate bias that may arise when estimating fixed-effect models with lagged dependent variables using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS), especially in cases where the number of groups is large and the time range relatively short [Nickell Reference Nickell1981].

For cross-country analysis, we fitted seven models. The unadjusted model covered 1989–2012, with 660 country-years nested in 29 countries. We did not exclude cases with missing information due to the high covariate number. We used the annual fertility rate as the dependent variable and the EBRD privatization index as the primary independent variable. Each model was controlled for population size. Model 1 includes dependent, independent, and population variables. Model 2 adds economic variables (unemployment, GDP per capita, consumer price index, inequality). Model 3 contains variables related to modernization (urbanization, industry/service employment). Model 4 controls for demographic factors (infant mortality, homicides, life expectancy). Model 5 adds public services (government consumption, hospital beds, physicians). Model 6 includes women’s opportunities (female education, labor measures). Model 7 includes significant covariates from all previous models. Model 8 accounts for time-related dynamics by including a cubic spline and one lagged dependent variable, estimated using GMM.

To account for the interdependence of repeated observations over time, we clustered standard errors at the town level in the models on Hungary and at the country level in the cross-country regressions. This approach allowed for arbitrary correlation of errors within towns or countries while maintaining independence across them, providing more conservative estimates of statistical significance that were robust to potential serial correlation in our panel data.

The data structure posed modeling challenges for capturing time change. Country-fixed effects filter time-invariant heterogeneity but leave models sensitive to unmeasured time-variant factors. A straightforward difference-in-differences approach with year-fixed effects was not feasible here because privatization reached all localities at varying rates in a highly time-driven pattern, leaving no stable untreated group and with privatization climbing from ~0 to ~90% across the towns. Including year-fixed effects is problematic for variables like privatization, which identify moderate variation by time across units. As shown in Supplemental Table A1, only 11% of the privatization variable’s variation is between Hungarian towns (rho=0.112). Privatization and year variables indicate high collinearity, with a Variance Inflation Factor of 3.67 (Hungary) and 3.76 (cross-country). Thus, including year-fixed effects effectively absorbs almost all of the temporal variation in privatization, leaving minimal degrees of freedom to estimate the privatization effect.

We tackled the bias that might emerge from unmeasured time-variant confounders in four ways. We opted to (a) either include linear time trends, piecewise time trends, or nonlinear local cubic splines (allowing for partial correction of secular shifts); (b) incorporate period dummies keyed to four-year electoral cycles; (c) conduct a separate robustness test with a lagged dependent variable to address potential concerns about dynamic time trends and serial correlation; and (d) explicitly test for most theoretically identified time-varying potential confounders. We acknowledge this as a limitation, though the universal nature of privatization ultimately precludes a textbook pre-post difference-in-differences comparison. A fuller discussion of these methodological issues appears in the online supplement.

Qualitative data and analysis

Our second empirical strategy involved a systematic qualitative thematic analysis of interviews surveying the lived experiences behind the theoretical mechanisms. We relied on semi-structured interviews with 82 workers in four medium-sized industrial towns in provincial Hungary, selected from 52 towns in the quantitative analysis. Data collection took place as part of a project exploring the social consequences of privatization, including its impact on labor-market precarity, communities, health, and identity. This dataset provides the most comprehensive insights into the lived experience of privatization. While this allows us to explore privatization’s upstream implications for work intensity, inequality, financial and temporal uncertainty, loss of collective resources, increased stress, and domestic care work, the interviews did not explicitly cover questions related to childbearing and fertility intentions.

Hungary implemented a complex privatization strategy. Some companies were privatized rapidly. Others underwent restructuring to make them attractive to foreign investors. Yet others ended up in domestic private hands. This diversity of privatization strategies makes the lived experience of privatization there more generalizable across other socialist countries than in cases that relied on only one of these methods. We identified four industrial towns—Ajka, Dunaújváros, Salgótarján, and Szerencs—based on their varied privatization strategies: dominant foreign, dominant domestic, and prolonged state ownership.

These four towns not only capture major variations in the independent variable but also cover the country’s different geographical regions and differ in population size, ranging from 10,000 (Szerencs) to 62,000 (Dunaújváros). We see little theoretical reason to expect that privatization had markedly different effects across towns of varying sizes within our sample. Socialist regimes in Eastern Europe aimed to reduce regional inequalities by deliberately locating industrial enterprises in underdeveloped or rural areas. This was part of a broader effort to integrate peripheral regions into the national economy and socialist state structure. Large, state-owned companies were often placed in provincial small towns to bring jobs, infrastructure, and social services to previously marginalized areas. These enterprises functioned not just as economic units but as social institutions, providing cradle-to-grave support for workers and their families. The supplement offers further detail on the towns, including descriptive statistics (Table A5) and a brief narrative summary of their economic profiles.

We conducted life-history interviews with workers between September 2016 and January 2017. These 90–120-minute interviews generated 816,118 words across 2,000 typed pages. Table A6 presents descriptive statistics for the interviewees. We selected participants who could reflect on their experiences before and after privatization, primarily individuals who had started working before 1989 and were in their twenties, thirties, or forties during the 1990s. Interviewees were chosen for their ability to speak to workplace changes, workloads, company-provided resources, community dynamics, and experiences as working mothers in socialist companies. This approach involved a trade-off: we prioritized those with substantial pre-1989 work experience over younger respondents of childbearing age. The interview length also limited our ability to include an additional thematic block specifically on fertility. While this is a clear limitation, the interviews offer valuable insights into upstream factors influencing childbearing intentions. Prior research confirms that such factors linked to privatization negatively affect fertility [see the review by Ghodsee and Orenstein Reference Ghodsee and Orenstein2021).

Results

Hungarian town-level results

We first examine how privatization relates to fertility at the local level in Hungary. This serves as our central case study, offering granular insights into how market reforms played out in the everyday lives of families. In what follows, we trace privatization trends in these 52 towns and present models linking ownership changes to local fertility rates.

Figure 4 presents fertility and privatization trends in the 52 Hungarian towns, which closely tracked one another—rapid early privatization before 1996 aligned with the steepest fertility drops, while slower late-1990s privatization coincided with slower fertility decline. As privatization halted in the 2000s, fertility stopped declining.

Figure 4 Privatization and fertility 1989–2006, annual means across towns, Hungary

Table 1 overviews the main results. The privatization variable is consistently negative and significant. Model 1 shows the transition from 0 to 100% private ownership as associated with 0.7 fewer children per woman (b = -0.007, p < 0.001), which holds in Model 2 after controlling for income and unemployment. In line with evidence from Western Europe [Andersen and Özcan Reference Andersen and Özcan2021), we find that unemployment positively correlates with fertility. Demographic factors in Model 3 do not predict fertility, while Model 4 shows that more hospital beds are associated with higher fertility. Privatization’s effect attenuates slightly in the full Model 5, but remains (b = -0.0042, p < 0.001). Model 6, which accounts for a nonlinear time trend and one lagged dependent variable, slightly attenuates the coefficient estimate again, but it remains similar in size and statistical significance (b = -0.0037, p < 0.001). The Arellano–Bond test for zero autocorrelation, reported in the table notes, suggests autocorrelation is not present with one lag.

Table 1 Privatization and fertility in Hungarian towns, 1989–2006

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

Notes: Privatization is lagged one year. All models are adjusted for annual population size. Lagged terms and time trends are omitted from the table. Arellano–Bond test p-value for zero autocorrelation for Model 6 is 0.12. Cluster-robust standard errors are in parentheses for Models 1–5. Arellano–Bond robust standard errors are in parentheses for Model 6. No. of observations refers to country-years.

The positive link between registered unemployment and fertility likely reflects the cushioning effect of unemployment benefits in Hungary, which offered up to 24 months of support at 70% of previous earnings from 1989 to 1993 [Vodopivec, Wörgötter and Raju Reference Vodopivec, Wörgötter and Raju2005]. This supports our qualitative findings—discussed below—that privatization’s impact extends beyond job loss. This correlation aligns with recent evidence on unemployment benefits mitigating the effects of deindustrialization in Hungary in the early 1990s [Scheiring et al. Reference Scheiring, Azarova, Irdam, Doniec, McKee, Stuckler and King2023]. Andersen and Özcan [Reference Andersen and Özcan2021] similarly argued that social policies reduced childrearing costs for unemployed women, potentially explaining transitions to motherhood after company closures.

For perspective, town fertility declined 0.68 points from 1.98 in 1990 to 1.30 in 2006 in the sampled towns. Median private ownership was zero in 1989 and 98.2% in 2006; the 2006 mean was 90%. Observed privatization corresponds to 54.3% of the average decline (0.37 fewer children per woman), filtering out economic, demographic, health, infrastructure, and other time-invariant characteristics. However, a conservative interpretation is warranted, as unobserved trends could cause bias in our noncausal models.

Supplemental Table A7 summarizes the robustness checks. Hungary’s privatization strategy allows the data to be decomposed into domestic and foreign acquisitions. Models 1–2 show a negative correlation between privatization and fertility, with minor coefficient differences, suggesting domestic privatization is particularly detrimental, perhaps due to more limited resources for restructuring and asset-stripping tendencies. Model 3 shows privatization remains significant when controlling for deindustrialization, though the large privatization coefficient drop indicates a potential mediation channel. Significance holds when controlling for general practitioner coverage (Model 4), age structure (Model 5), and deep poverty measured by the share of people receiving food assistance.

Autocorrelation could exist in the fertility time series if previous years determine subsequent values. We control for this using a lagged dependent variable, a widely accepted autocorrelation test despite issues when estimating with OLS [Keele and Kelly Reference Keele and Kelly2006]. Model 7 shows privatization remains highly significant after including lagged fertility when estimating using OLS. Model 8 specifies a four-year period of fixed effects to filter election cycle government changes and gradual cultural shifts—privatization retains significance. With an annual trend variable in Model 9, the privatization effect also remains.

We separately assessed theoretically relevant national-level impacts. Models 10–18 retain a significant privatization variable. Income inequality in Model 12 reduces the privatization effect size most, suggesting potential mediation, as inequality correlates with privatization [Bandelj and Mahutga Reference Bandelj and Mahutga2010] and also with lower fertility [Cherlin, Ribar and Yasutake Reference Cherlin, Ribar and Yasutake2016]. Finally, one could argue that the privatization variable picks up the effect of democratization and the expansion of free speech and postmodern values. However, Model 16 shows robustness to liberal democracy controls, Model 17 to free speech, and Model 18 to equal access to public services, suggesting national service changes do not fully explain fertility drops.

Model 20 estimates the model including only the nonlinear cubic spline and covariates, Model 22 estimates the GMM model with one lag omitting the spline, and results remain robust. Despite evidence that one lag is sufficient, Models 21–23 include an additional lag with and without the spline. Again results remain similar in size and are statistically significant.

The lived experience of privatization

Next, we turn to qualitative evidence that sheds light on how privatization produced the mechanisms detected in our quantitative analysis. By examining personal experiences of increased job strain, financial precarity, and the erosion of decommodifying supports, these life-history interviews illustrate the everyday realities behind the patterns observed at the town level.

Our interview analysis revealed themes aligning with our theoretical framework. We present these topics following the four mechanisms outlined in Figure 3. Interviewees generally viewed socialism’s economic and social aspects favorably, albeit sometimes inaccurately. However, they expressed skepticism toward intrusive, top-down political management, consistent with other research findings [Hilmar Reference Hilmar2023]. Initially, many welcomed the regime change and privatization. However, as challenges arose, disillusionment set in, marking the starting point of our analysis.

One frequently mentioned problem is that privatization led to increased workload (Finding 1). Interviewees reported significantly increased workloads during the 1990s connected to privatization:

Before privatization, I didn’t have to work as much and did what I was good at. After privatization, this changed. If you wanted to keep your job, you had to do things you didn’t like. You had to think twice because the alternative was becoming unemployed or finding a new job 50–60 kilometers away. (Skilled worker, Salgótarján Steelworks)

Interviewees mentioned increased workload as a reason for family tensions, which sometimes led to a breakup or divorce. Family destabilization might have negatively affected childbearing rates:

In the 1990s, we lived at my mother’s place, with one room and two children, because we were building our own house. I had to work more and took on too much, and then, you know, our private life got neglected. And then, you know, he found another woman. (Clerk, OTP Bank, Szerencs)

Interviews also confirmed that financial and temporal uncertainty increased during the 1990s (Finding 2). Socialist companies provided lifetime jobs; in some cases, companies would employ several generations of workers from the same family. However, this changed with privatization:

Here in Salgótarján, everything slowly disappeared with privatization. If you want to work here, you have the local government, health care, and retail businesses. That’s how people make a living here. But a lot of them just leave. (Clerk, Salgótarján County Food Cooperative)

Fear of unemployment became a mental burden and increased psychosocial stress. Uncertainty about the future was at least as burdensome as financial insecurity. Talking about the prospect of potential job loss, a skilled manual worker at the telecommunications company in Salgótarján recalled how privatization-related uncertainty “tormented us mentally, [because] we could not know who is going to be the next, tomorrow it’s you, then the day after tomorrow it’s me.”

Respondents described their future as unpredictable and reported feeling at the whim of forces beyond their control. Regardless of their age or education, respondents reported a sense of vulnerability and insecurity in every town. The most vivid reactions came from low-skilled workers, such as miners:

Insecurity is the worst thing. Because when you face a specific bad thing that’s different, I know what to expect. But that’s the worst when you don’t know what’s coming next. You’re vulnerable, helpless. (Unskilled worker, Ajka Coal Mine)

These financial and temporal uncertainties were also accompanied by new forms of deprivation, such as homelessness and malnutrition, which had been rare under state socialism. Growing income inequality intensified the sense of insecurity. With increased uncertainty, couples became less willing to make long-term commitments such as having children.

Alcoholism is another channel through which uncertainties negatively affect childbearing rates. The loss of their jobs drove some men toward hazardous drinking to deal with the shame and stress of unemployment:

You know, this came with the regime change. Many families experienced the same story as us. My man was good at his job. Then he was fired. When he lost his career, he could not handle it. He was beaten mentally. He drove himself to the ground. He drank, and then his ulcer perforated. (Middle manager, Szerencs State Food Cooperative)

These alcohol problems often destabilized families. However, financial issues generated tensions within families even without alcohol:

We had a perfect marriage, indeed. And when one tries to give the same as they were used to and cannot manage, people start having disagreements. Then, one only sees from the inside that this must end because otherwise, it will not end well. (Skilled worker, Ajka Coal Mine)

Prolonged state ownership mitigated uncertainties. While some described privatization as chaotic and mismanaged, state-owned company employees had more positive recollections. For example, a Dunaújváros ironworks clerk explained how the company had established a foundation offering temporary, part-time employment to workers at risk of redundancy. Others reported that state-owned companies helped internally transfer workers when branches closed. These companies also tried to protect workers by channeling them into retirement or putting them on sick leave instead of resorting to layoffs:

They were not ill, but they were escaping toward sick pay or disability retirement. [These were] … people who would not have been considered ill under normal circumstances. They tried to seize the opportunities and win some time through sick pay or disability pension. (Middle manager, Salgótarján Hospital)

The third interview theme is the loss of direct collective resources like nurseries, kindergartens, and care arrangements (Finding 3), and the effect this had on mothers’ ability to return to their jobs post-birth. Pre-privatization, interviewees could stay home with their children without the risk of losing their jobs: some could do this for several years with a guaranteed right to return to the same state-socialist company. Larger plants operated nurseries and kindergartens for working mothers:

There were four years between the birth of my two children, ’76 and ’80. My daughter was born in ’80, and I stayed home for two years. The steelworks here had a nursery, so she went there. I took her there each day. There were many nurseries back then in this town. Most bigger companies had their own nursery, even kindergartens. (Skilled worker, Salgótarján Steelworks)

State companies also reduced work–family conflicts through making informal arrangements for working mothers, which were not legally mandated but were allowed for by managers who flexibly interpreted governmental female employment policies. Young mothers often received company social policy funds and could stay at home with sick children:

Before privatization, you know, when there was something with the kid, I could take some time off, and they would allow me to go home. They allowed me to work the morning shift so that I could be at home in the afternoon after school. But then, later, they wouldn’t let you do this anymore. I couldn’t just work in the mornings when he went to school. I had to stay there in the afternoon too. (Unskilled worker, Szerencs Chocolate Factory)

In contrast to privatized companies, interviewees reported that state-owned companies continued some of their not-for-profit practices and often considered their employees’ family backgrounds during the reorganization process. For instance, before the Salgótarján Power Plant was privatized in the 1990s, its managers tried to retain employees with young children, at least temporarily, to save them from immediate unemployment:

When they started to fire people, they found these positions so that I could stay, you know. They knew I had young children. They preferred to retire those close to the retirement age and then tried to keep those with children. (Unskilled worker, Salgótarján Power Plant)

The final theory-relevant theme emerging from the interviews is Finding 4, the loss of collective resources indirectly related to childbearing, such as housing support, subsidized holidays, healthcare, and cultural and sports services, as well as the disintegration of communities the companies had nurtured. Several interviewees said workers in state-socialist companies had been allocated housing shortly after taking up their jobs. Some had had to wait longer. Some also mentioned having received a larger house with an extra room when a new child was born:

Then, in the 1970s, we got another flat allocated in this 10-story socialist prefab panel block. That was something, you know. We got a bigger apartment with one more room when the first child came. (Unskilled worker, Ajka Coal Mine)

We also need to take into account that miners and mining towns received special attention under socialism. Generous allowances such as that mentioned in the quote above were rare. There were significant differences in access to state housing which favored certain cadres and the intellectuals associated with them [Szelényi Reference Szelényi1989], as well as in other areas of state welfare policy [Szalai Reference Szalai1986]. However, most interviewees clearly perceived housing as easier to access under state socialism than afterward. Direct provision of housing was not the only way in which the state and companies intervened in housing; subsidized loans were also frequent.

After privatization, younger interviewees had to take costly home loans, often with parental support, to secure housing. Some interviewees talked about feeling ashamed of this: “My mother has a good pension; however, it is a shame that my retired mother supports me financially. What kind of future is that?” (office assistant, Szerencs School). The difficulties of securing a roof over one’s head may have been among the principal factors behind the postponement of the first birth.

Subsidized holidays represented another form of indirect family support that pre-privatization socialist companies provided their workers with:

Here in Salgótarján, skiing was a big thing. Up at the Galyatetö [a popular tourist resort], there is the ski slope, and the ironworks school had this mountain retreat there for around 25 people. And the kids could go there in the winter. (Skilled worker, Salgótarján Mining Equipment Factory)

As companies were privatized, they discontinued these holiday services. Some sold their holiday facilities to secure funds with which to survive the turbulent 1990s. Others kept some of their facilities but ended the practice of subsidized holidays, so workers had to pay the full price. Even the better-off workers suffered from the loss of these company-based services. As a freelance entrepreneur recollected in Ajka: “I haven’t had a break since the regime change in 1989. Before that, we went on a holiday each year to Lake Balaton; the company had a holiday resort there.”

Interviewees highlighted the importance of the company-based medical services available to employees of state companies, which were often more comprehensive than those offered by privatized firms. Some reported having worked without documentation or insurance in the new private sector. These changes may potentially have contributed to fertility decline, either through direct health impacts or by increasing childcare burdens for young couples who also had sick parents. The closure of clinics, reduction of hospital bed numbers, and increase in home convalescence further exacerbated the situation. Women, often forced out of employment, frequently took on additional care work at home when family members fell ill. Consequently, the postsocialist health crisis represented an extra care burden for women [Ghodsee Reference Ghodsee2019].

State companies had operated theaters, cultural centers, and sports facilities that were now discontinued or handed to local government control. However, local governments had previously also received company funding, a mechanism that was broken with privatization. According to the interviewees, the loss of this funding led municipalities to close services like recreational theme parks, complicating the logistics of spending free time with children:

Back then, when we might have an idea, like, OK, let’s go to the theme park. And then we went with the family. Then we met this couple on the street whom we knew. They joined us. But we can’t do this anymore. What should I do with my grandchildren? There is no place to take them anymore. (Clerk, Dunaújváros Ironworks)

A large share of interviewees reported positive associations regarding communities at the companies they used to work for. Interviewees often described the companies or their smaller collectives as families whose members could trust and count on each other. These communities were not only relevant to social cohesion; people had also helped each other out more frequently than they did after 1990, including by helping with household chores, childcare, or taking children on holiday or weekend outings. Many interviewees fondly remembered the communities at their former companies, which they sometimes described as “trusting, supportive families.”

Back then, we knew each other. We relied on each other’s help, even with the kids. We trusted each other much more back then, that’s for sure. But social life completely changed here in the 1990s. (Skilled worker, Salgótarján Steelworks)

Privatization, downsizing, and fierce labor-market competition weakened workplace communities by increasing conflicts:

These conflicts had an impact on people. This turned people against each other. The thing that you should get fired, I don’t want to get fired. I don’t want my family to be insecure. It’s your family that should be insecure, not mine. So, in a sense, this was a fight for survival. (Middle manager, Szerencs Sugar Factory)

The interviews revealed that privatization’s impact extends beyond unemployment and financial hardship. It encompasses increased workload and stress, heightened uncertainty, community fragmentation, and the loss of the collective resources that previously supported social reproduction. For precariously employed women in postsocialist states, privatization emerges as a multifaceted shock with significant implications for childbearing decisions. While our interviews focused on the lived experience of privatization, they provide unique insights into the causal mechanisms directly influencing such decisions. Existing research corroborates these findings, offering both qualitative and quantitative evidence linking these privatization experiences to decisions about having children [Billingsley Reference Billingsley2010; Fodor Reference Fodor2003; Gregor and Kováts Reference Gregor and Kováts2019; Kohler and Kohler Reference Kohler and Kohler2002; Kreyenfeld Reference Kreyenfeld2010; Tímár Reference Tímár, Rainnie, Smith and Swain2005].

As people died and migrated and new births plummeted, the studied towns shrank. Those who remained increasingly felt left behind. The lack of children playing on the streets emerged as a metaphor for abandonment, encapsulating the totality of privatization’s lived experience:

Children were playing here; kids used to play football or hide and seek. You could hear the children playing. Now, there is only silence. (Skilled worker, Salgótarján Steelworks)

Cross-country models

To assess the generalizability of our Hungarian findings, we next analyze a larger dataset spanning 29 postsocialist countries. This broader vantage point helps clarify whether the mechanisms we identified—such as the erosion of decommodifying supports—are specific to Hungary or reflect a more universal regional pattern. It also offers a glimpse into how different privatization strategies and time periods could shape childbearing patterns, setting the stage for future research on the evolving interplay between market reforms and fertility in other contexts.

Table 2 presents cross-country findings. Privatization consistently shows a negative correlation with fertility in every model, especially in Model 7, including all significant covariates. A 1-point rise in the EBRD privatization index corresponds to a minimum 0.18-point fall in fertility, accounting for other factors. Public services spending (government consumption, physician numbers) positively correlates with fertility. Model 6 indicates a positive association between higher female employment and fertility but a negative one for the female-to-male employment ratio. It also reveals a positive association between female tertiary education and fertility, implying that women’s economic opportunities may not adversely affect fertility, which aligns with the gender equality literature. Model 8 estimates the relationship using the same set of covariates as Model 7, including a cubic spline time trend and one lagged dependent variable. The coefficient estimate attenuates considerably, but remains statistically significant at the 10% level.

Table 2 Privatization and fertility in postsocialist countries, 1989–2012

+p<0.10, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

Notes: Privatization is lagged one year. Lagged terms and time trends are omitted from the table. All models are adjusted for countries’ annual population size. Arellano–Bond test p-value for zero autocorrelation for Model 6 is 0.48. Cluster-robust standard errors are in parentheses for Models 1-7. Arellano–Bond robust standard errors are in parentheses for Model 8. No. of observations refers to country-years.

The average privatization level accounts for 49.75% of the fertility decline (0.37 fewer children per woman), similar to the Hungarian results. In 29 postsocialist countries, fertility dropped by 0.68, from 2.58 in 1989 to 1.84 in 2012, while the privatization index rose from 1.23 to 3.54. The fact that unemployment is insignificant in this sample aligns with our argument that the positive correlation in Hungary between registered unemployment and fertility likely reflects the cushioning effect of unemployment benefits. However, caution is needed, as our models do not prove causality.

Again, we conducted multiple robustness checks, summarized in Table A8 of the online supplement. Model 1 shows that we retained a significant association after controlling for migration, with a sample size of only 101 country-years. Next, we repeated our test concerning deindustrialization. The closure of industrial plants could represent economic shocks unrelated to privatization, such as import exposure, the collapse of the internal socialist market (Comecon), or the phasing out of company subsidies. Model 2 shows that we retained a significant privatization–fertility association when controlling for deindustrialization.