Impact statement

This paper presents a detailed overview of existing mental health chatbots and their technical specifications, introduces a novel synthesis of their strengths and limitations and offers fresh implications for clinical applications and developers of mental health chatbots.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, mental health is defined as a state of well-being in which an individual can realize their own potential, manage the normal stresses of life, work productively and fruitfully and make a positive contribution to their community. This definition emphasizes the importance of an individual’s ability to function effectively in society and to lead a fulfilling life. Mental health is not just the absence of mental illness, but a state of overall well-being (Organisation, 2014). Mental disorders are a global concern, affecting 29% of individuals and causing disability. The economic burden is projected to cost the global economy US $16 trillion between 2011 and 2030 (Steel et al., Reference Steel, Marnane, Iranpour, Chey, Jackson, Patel and Silove2014; Whiteford et al., Reference Whiteford, Ferrari, Degenhardt, Feigin and Vos2015). In this regard, notably depression and anxiety are highly prevalent across the globe and underscore the need for robust and effective therapeutic strategies (Khosravi and Azar, Reference Khosravi and Azar2024a).

Globally, 70% of people with mental illness receive no formal treatment due to low perceived need, perceived stigma or a shortage of mental health professionals, particularly in rural and low-income areas (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Angermeyer, Borges, Bromet, Bruffaerts, de Girolamo, de Graaf, Gureje, Haro, Karam, Kessler, Kovess, Lane, Lee, Levinson, Ono, Petukhova, Posada-Villa, Seedat and Wells2007; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Ellis, Konrad, Holzer and Morrissey2009; Conner et al., Reference Conner, Copeland, Grote, Koeske, Rosen, Reynolds and Brown2010; Mojtabai et al., Reference Mojtabai, Olfson, Sampson, Jin, Druss, Wang, Wells, Pincus and Kessler2011). There is a shortage of mental health resources, funding and literacy (Vaidyam et al., Reference Vaidyam, Wisniewski, Halamka, Kashavan and Torous2019). This is particularly pronounced in low- and middle-income countries, where there are only 0.1 psychiatrists per 1,000,000 people, compared to 90 in high-income countries (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Vos, Lozano, Naghavi, Flaxman, Michaud, Ezzati, Shibuya, Salomon, Abdalla, Aboyans, Abraham, Ackerman, Aggarwal, Ahn, Ali, Alvarado, Anderson, Anderson, Andrews, Atkinson, Baddour, Bahalim, Barker-Collo, Barrero, Bartels, Basáñez, Baxter, Bell, Benjamin, Bennett, Bernabé, Bhalla, Bhandari, Bikbov, Bin Abdulhak, Birbeck, Black, Blencowe, Blore, Blyth, Bolliger, Bonaventure, Boufous, Bourne, Boussinesq, Braithwaite, Brayne, Bridgett, Brooker, Brooks, Brugha, Bryan-Hancock, Bucello, Buchbinder, Buckle, Budke, Burch, Burney, Burstein, Calabria, Campbell, Canter, Carabin, Carapetis, Carmona, Cella, Charlson, Chen, Cheng, Chou, Chugh, Coffeng, Colan, Colquhoun, Colson, Condon, Connor, Cooper, Corriere, Cortinovis, de Vaccaro, Couser, Cowie, Criqui, Cross, Dabhadkar, Dahiya, Dahodwala, Damsere-Derry, Danaei, Davis, De Leo, Degenhardt, Dellavalle, Delossantos, Denenberg, Derrett, Des Jarlais, Dharmaratne, Dherani, Diaz-Torne, Dolk, Dorsey, Driscoll, Duber, Ebel, Edmond, Elbaz, Ali, Erskine, Erwin, Espindola, Ewoigbokhan, Farzadfar, Feigin, Felson, Ferrari, Ferri, Fèvre, Finucane, Flaxman, Flood, Foreman, Forouzanfar, Fowkes, Fransen, Freeman, Gabbe, Gabriel, Gakidou, Ganatra, Garcia, Gaspari, Gillum, Gmel, Gonzalez-Medina, Gosselin, Grainger, Grant, Groeger, Guillemin, Gunnell, Gupta, Haagsma, Hagan, Halasa, Hall, Haring, Haro, Harrison, Havmoeller, Hay, Higashi, Hill, Hoen, Hoffman, Hotez, Hoy, Huang, Ibeanusi, Jacobsen, James, Jarvis, Jasrasaria, Jayaraman, Johns, Jonas, Karthikeyan, Kassebaum, Kawakami, Keren, Khoo, King, Knowlton, Kobusingye, Koranteng, Krishnamurthi, Laden, Lalloo, Laslett, Lathlean, Leasher, Lee, Leigh, Levinson, Lim, Limb, Lin, Lipnick, Lipshultz, Liu, Loane, Ohno, Lyons, Mabweijano, MacIntyre, Malekzadeh, Mallinger, Manivannan, Marcenes, March, Margolis, Marks, Marks, Matsumori, Matzopoulos, Mayosi, McAnulty, McDermott, McGill, McGrath, Medina-Mora, Meltzer, Mensah, Merriman, Meyer, Miglioli, Miller, Miller, Mitchell, Mock, Mocumbi, Moffitt, Mokdad, Monasta, Montico, Moradi-Lakeh, Moran, Morawska, Mori, Murdoch, Mwaniki, Naidoo, Nair, Naldi, Narayan, Nelson, Nelson, Nevitt, Newton, Nolte, Norman, Norman, O’Donnell, O’Hanlon, Olives, Omer, Ortblad, Osborne, Ozgediz, Page, Pahari, Pandian, Rivero, Patten, Pearce, Padilla, Perez-Ruiz, Perico, Pesudovs, Phillips, Phillips, Pierce, Pion, Polanczyk, Polinder, Pope, Popova, Porrini, Pourmalek, Prince, Pullan, Ramaiah, Ranganathan, Razavi, Regan, Rehm, Rein, Remuzzi, Richardson, Rivara, Roberts, Robinson, De Leòn, Ronfani, Room, Rosenfeld, Rushton, Sacco, Saha, Sampson, Sanchez-Riera, Sanman, Schwebel, Scott, Segui-Gomez, Shahraz, Shepard, Shin, Shivakoti, Singh, Singh, Singh, Singleton, Sleet, Sliwa, Smith, Smith, Stapelberg, Steer, Steiner, Stolk, Stovner, Sudfeld, Syed, Tamburlini, Tavakkoli, Taylor, Taylor, Taylor, Thomas, Thomson, Thurston, Tleyjeh, Tonelli, Towbin, Truelsen, Tsilimbaris, Ubeda, Undurraga, van der Werf, van Os, Vavilala, Venketasubramanian, Wang, Wang, Watt, Weatherall, Weinstock, Weintraub, Weisskopf, Weissman, White, Whiteford, Wiebe, Wiersma, Wilkinson, Williams, Williams, Witt, Wolfe, Woolf, Wulf, Yeh, Zaidi, Zheng, Zonies, Lopez, AlMazroa and Memish2012; Oladeji and Gureje, Reference Oladeji and Gureje2016). Furthermore, mental health services reach only 15% and 45% of those in need in developing and developed countries, respectively (Hester, Reference Hester2017).

The need for improved mental health services has grown, but fulfilling these needs has become challenging and expensive due to a scarcity of resources (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Patel, Saxena, Radcliffe, Ali Al-Marri and Darzi2014). Therefore, innovative solutions are required to address the resource shortage and encourage self-care among patients. In this regard, mobile applications present a partial solution to the global mental health issues (Chandrashekar, Reference Chandrashekar2018; Khosravi and Azar, Reference Khosravi and Azar2024b).

Chatbots, in particular, are one of the primary mobile applications utilized for mental health purposes (Abd-Alrazaq et al., Reference Abd-Alrazaq, Alajlani, Alalwan, Bewick, Gardner and Househ2019; Khosravi et al., Reference Khosravi, Azar and Izadi2024a). Chatbots are software applications that can mimic human behavior and perform specific tasks by engaging in intelligent conversations with users (Adamopoulou and Moussiades, Reference Adamopoulou, Moussiades, Maglogiannis, Iliadis and Pimenidis2020). These conversational agents utilize text and speech recognition to interact with users (Nadarzynski et al., Reference Nadarzynski, Miles, Cowie and Ridge2019).

Chatbots employ various forms of communication, including spoken, written and visual languages (Valliammai, Reference Valliammai2017). Over the past decade, the use of chatbots has increased significantly and has become widespread in areas such as mental health (Abd-Alrazaq et al., Reference Abd-Alrazaq, Alajlani, Alalwan, Bewick, Gardner and Househ2019). It is anticipated that chatbots will play a crucial role in addressing the shortage of mental health care (Palanica et al., Reference Palanica, Flaschner, Thommandram, Li and Fossat2019). Chatbots can facilitate interactions with individuals who may be hesitant to seek mental health advice due to stigmatization and provide greater conversational flexibility (Radziwill and Benton, Reference Radziwill and Benton2017). Moreover, chatbots have demonstrated considerable promise in the delivery of healthcare services, particularly for individuals who are inclined to avoid specific services due to cultural or religious values, or personal factors such as fear or stigma (Khosravi et al., Reference Khosravi, Mojtabaeian and Aghamaleki Sarvestani2024b).

Due to the innovative technical features of chatbot platforms, there is a substantial need to investigate and gather data on the characteristics of chatbots. This information is crucial for researchers, producers, administrators and policymakers in this field. Researchers may draw on these data to generate in-depth, evidence-based evaluations of chatbot performance and to elaborate on their functional attributes. Producers can use the information on the technical strengths and weaknesses of different chatbots to benchmark their products and to plan targeted enhancements. Policymakers and service managers can also employ these findings to design and implement strategies for integrating chatbots into mental health service provision within their respective organizations.

To the best of our knowledge, no systematic review of reviews has been conducted with the aim of examining the technical features and characteristics of chatbots in mental health. Such an approach would yield a comprehensive catalog of chatbots and their technical characteristics as reported in previous reviews. Therefore, this paper presents a valuable and innovative approach to fill the existing gap in the literature through the provision of a thematic analysis on the existing chatbots and their technical features within mental health services.

Methods

This paper adopted a qualitative approach and conducted a systematic review of the current review studies within the literature published from 2000 to 2023. The main objective of this study was to identify the existing chatbots and their technical features in the field of mental health services. A systematic review of reviews, or umbrella review, is generally described in methodological guidance as addressing a well-defined yet relatively broad field of research or overarching theme. The topic is expected to be sufficiently expansive to encompass multiple existing systematic reviews (Belbasis et al., Reference Belbasis, Bellou and Ioannidis2022; Abdellatif et al., Reference Abdellatif, Dadam, Vu, Nam, Hoan, Taoube, Tran and Huy2025).

Data collection and search strategy

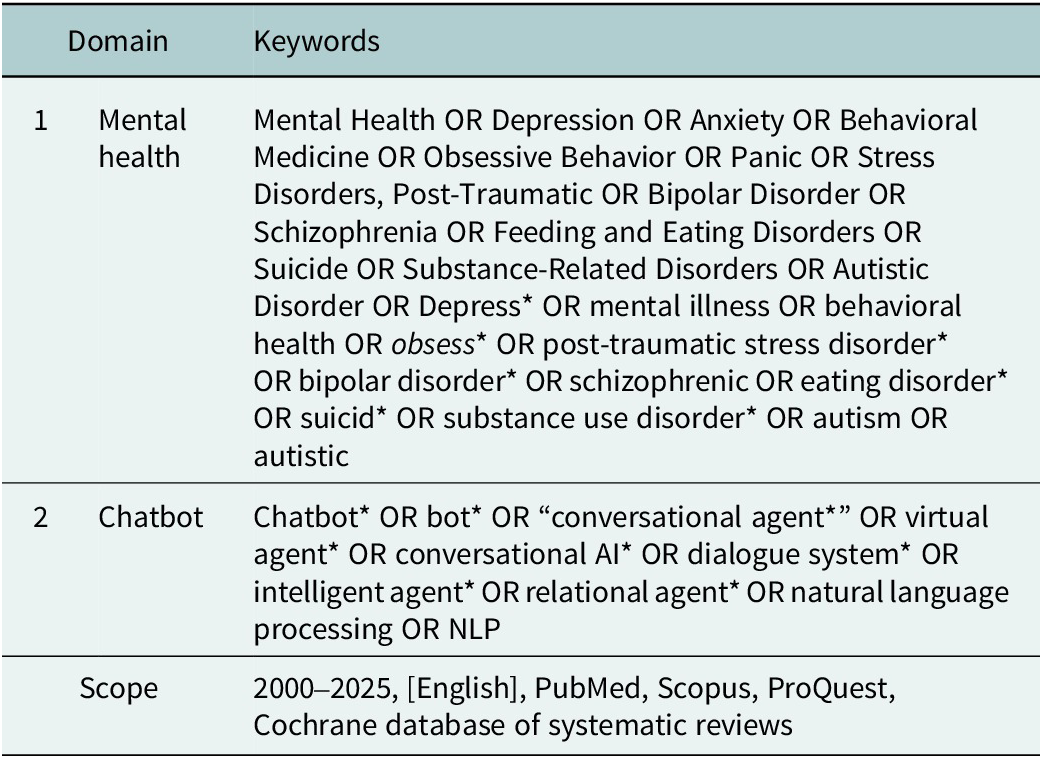

A systematic search was conducted across several databases, including PubMed, Scopus, ProQuest and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, to identify existing literature on the topic. The search terms were categorized into two domains: Mental health and Chatbot. Broad terms were initially used to enhance sensitivity, and synonyms were incorporated using the “OR” operator. The “AND” operator was used to ensure specificity and minimize irrelevant studies. The search was conducted on December 13, 2025, and the search strategy is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. The search strategy utilized to conduct the systematic review

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This study selected review articles published in English from 2000 to 2025 that focused on mental health chatbots and their technical features as the inclusion criteria. The exclusion criteria were articles that did not discuss a relevant chatbot in the mental health domain, had no title, abstract or full text that referred to a chatbot intervention in mental health services or had an inaccessible full text. Moreover, any other types of publications, except for journal articles, were also excluded from the study.

Selection and extraction of data

The systematic review was carried out in several stages. In the first stage, the authors independently reviewed all articles retrieved from the databases multiple times. In the second stage, the authors examined the abstracts of the selected articles and then evaluated the full text of the chosen articles in depth. To ensure the comprehensiveness of the review, the authors also checked the references cited in the articles. In the final stage, the authors selected the articles that met the quality criteria for inclusion in the study. Moreover, the authors used a form to extract relevant information from the selected articles, such as the authors’ details, journal’s name, methodology, aim, results and the mentioned mental health chatbots. The extracted information was then summarized and synthesized using MAXQDA 12 software. The authors independently verified the results at each stage to ensure reliability and minimize bias.

Quality appraisal of final articles using the CASP checklist

The CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme) appraisal checklist, which encompasses various study designs, was used to assess the quality of the selected studies. The checklist assists in evaluating the validity, relevance, bias and applicability of research studies. The checklist consists of 10 questions that assess articles based on various criteria, such as validity of results, quality of study and applicability of results (Programme, 2018).

We applied a scoring system where each question received 2 points for yes, 1 point for cannot tell and 0 points for no. The highest score was 16, which corresponded to three quality levels: low, medium and high. We only included articles with an average score of 9 or more. We calculated the total score for each study and presented the score for each study type in the results section. After selecting and appraising the quality of articles using the CASP checklist, we only included the final articles in our review.

Data analysis

In this phase of the research, we applied Braun and Clarke’s method for thematic analysis, which consists of six steps: familiarization, coding, generating themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes and writing up (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2023). The objective of this phase was to discover the existing chatbots and their technical features in the mental health domain.

First, we followed a series of steps to familiarize ourselves with the topic and the context of the research by reading the content about mental health chatbots and their technical features within the final articles. Second, we then coded them based on their technical features mentioned within the data of the final articles. Third, we also generated subthemes and themes from the coded data by categorizing and grouping the codes. Fourth, we reviewed the generated themes multiple times to ensure the validity and reliability of the process. Fifth, we then defined and named the themes and their subthemes based on their essence and existential characteristics. Finally, we combined and accumulated the generated themes, subthemes and their codes in a single sheet. This process of qualitative thematic analysis was adhered to Lincoln and Guba’s criteria for qualitative research to validate and verify the findings. The criteria include four key aspects: credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability of the qualitative content analysis process (Lincoln and G, Reference Lincoln and G1985).

Findings

The study involved three key steps: conducting a systematic review, evaluating the quality of the chosen articles and performing a thematic analysis of the obtained data. The outcomes of the study are organized into three sections, each reflecting one of the steps.

Systematic review

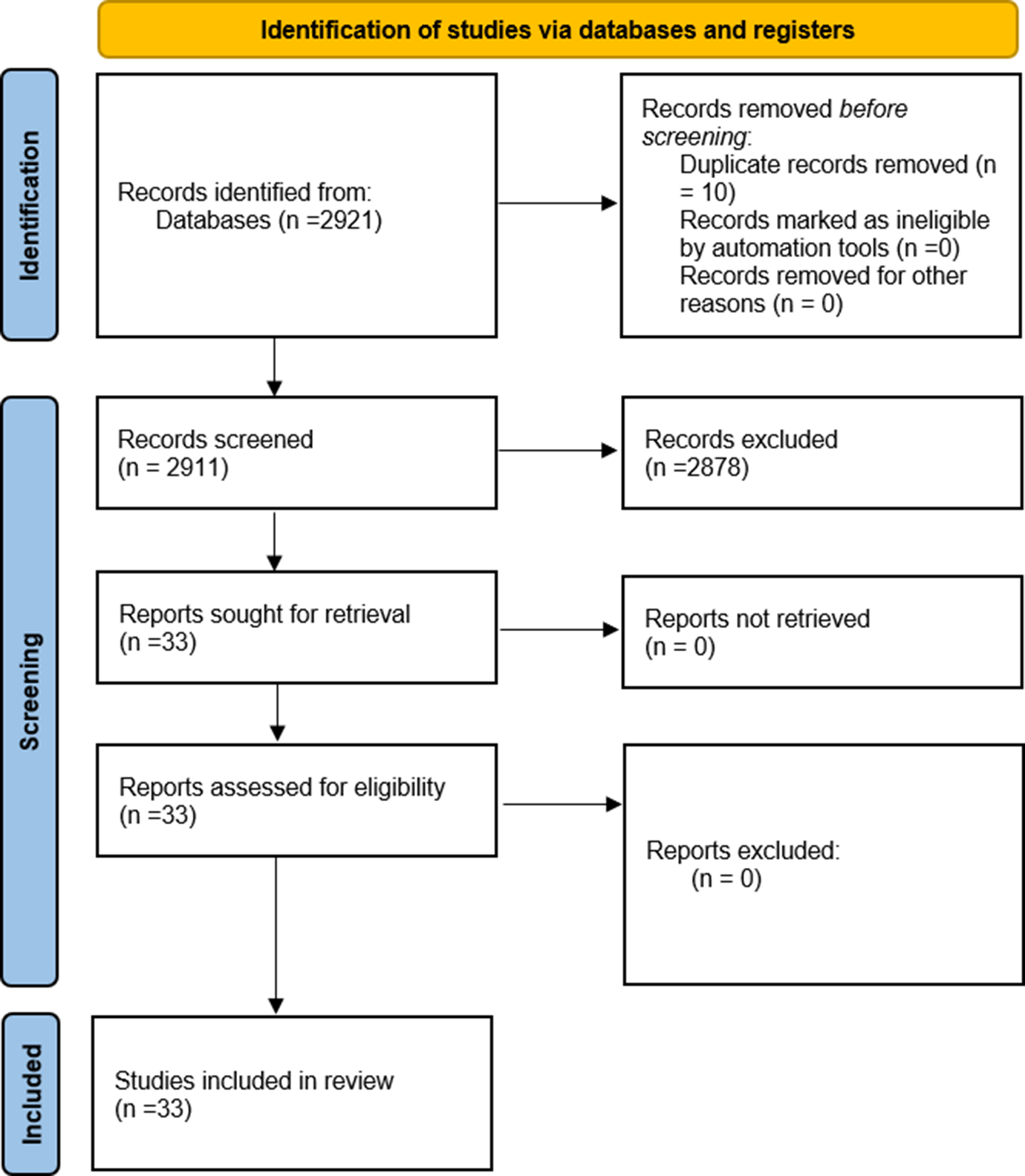

The search yielded 2,921 records, of which 10 were duplicates and were removed. The remaining records were screened by title and abstract for relevance and eligibility. The screening process excluded 2,878 records that did not meet the inclusion criteria or met the exclusion criteria. The full texts of the 33 remaining records were retrieved and assessed for quality and suitability. The final selection consisted of 33 papers that met all the requirements (Figure 1). The mean year of publication of the included studies was 2023 (standard deviation [SD] = 2.00). Among the included studies, systematic reviews constituted 48.5%, scoping reviews 27.3%, systematic reviews with meta-analyses 18.2% and narrative reviews 6% of the total. Supplementary Appendix 1 (Bibliography) contains the details regarding the final articles that were selected for the literature review.

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram of the systematic review.

Quality assessment of final articles

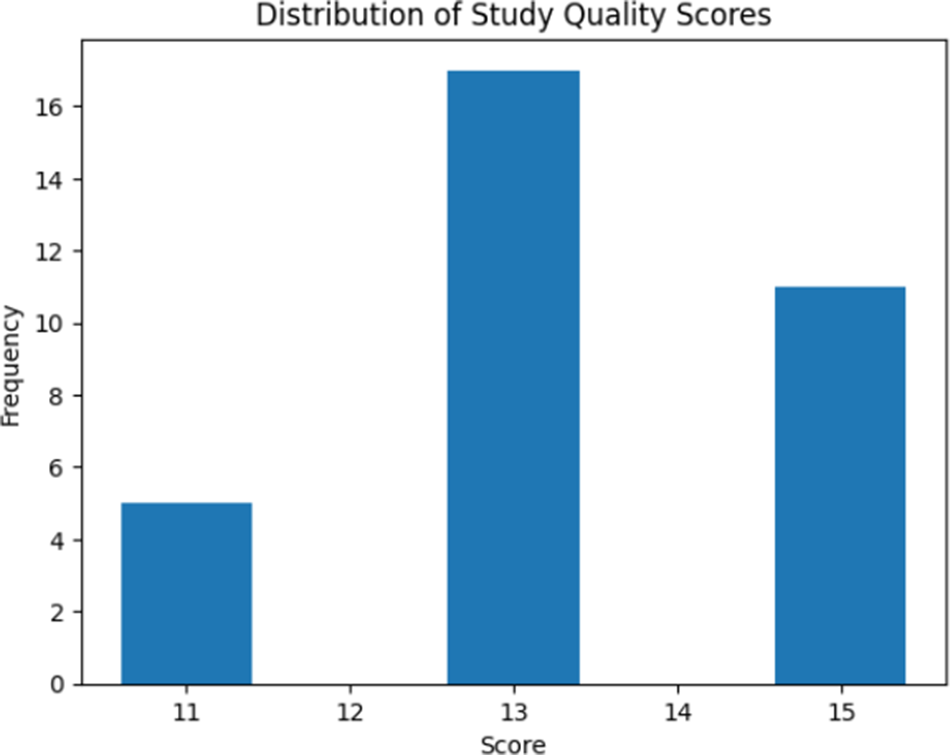

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of quality assessment scores across the included studies based on the CASP checklist. The mean quality score of the studies was 13.36 (SD = 1.36). All 33 articles had a clearly focused question and searched for the appropriate type of papers, indicating their reasonable validity. However, not all articles included all relevant studies or adequately assessed their quality, although their data were still worth considering. All articles combined the results of the review appropriately, indicating their correct methodology. The results of the review were precise, but their applicability to the local population was unclear. Moreover, all articles considered all important outcomes and showed that the benefits outweighed the harms and costs, indicating their high efficiency. The final scores ranged from 11 to 15, indicating an acceptable quality of the included papers. The risk of bias within the studies was moderate, as they mostly had a clear question, searched for the right type of papers, included all relevant papers and reported the results precisely. The details of the quality assessment of the final papers are shown in Supplementary Appendix 2 (Quality Assessment).

Figure 2. Results of the quality assessment of the final papers.

Thematic analysis

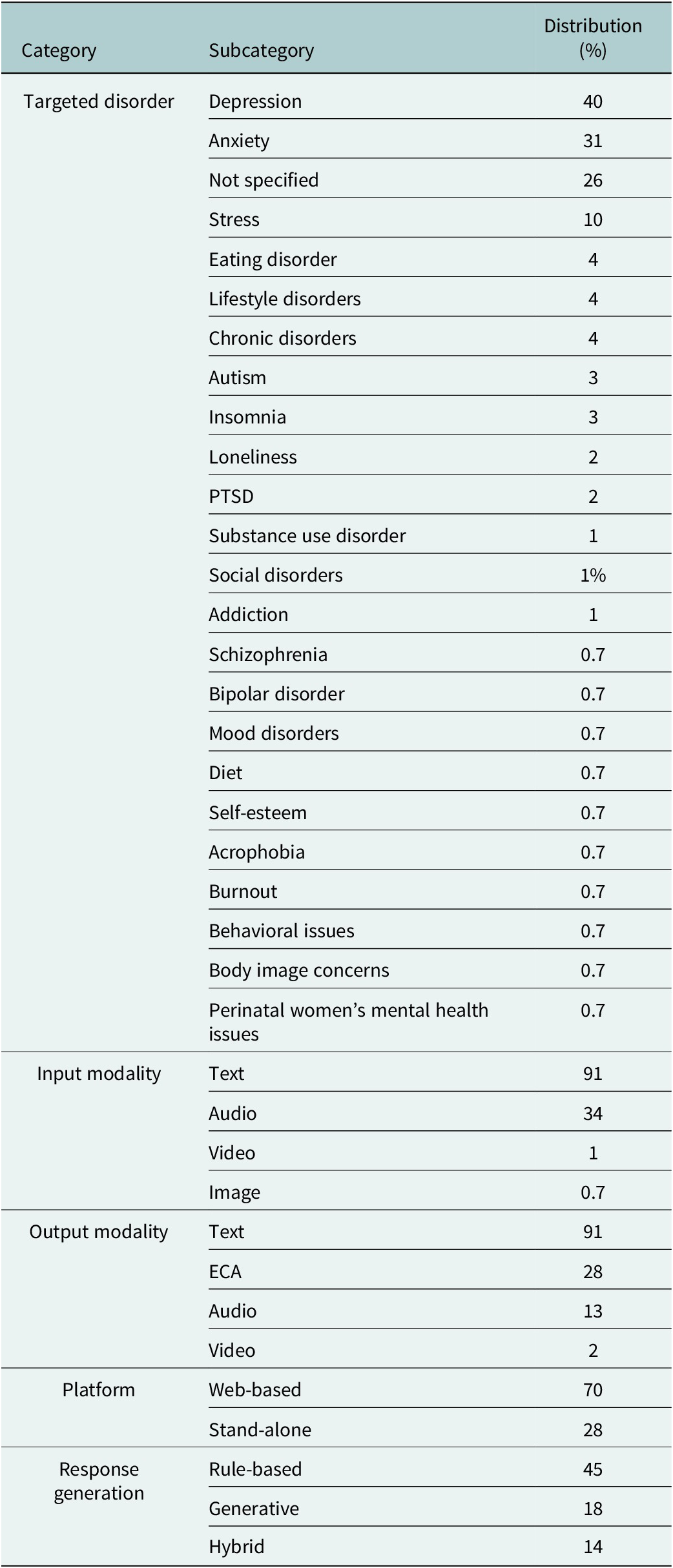

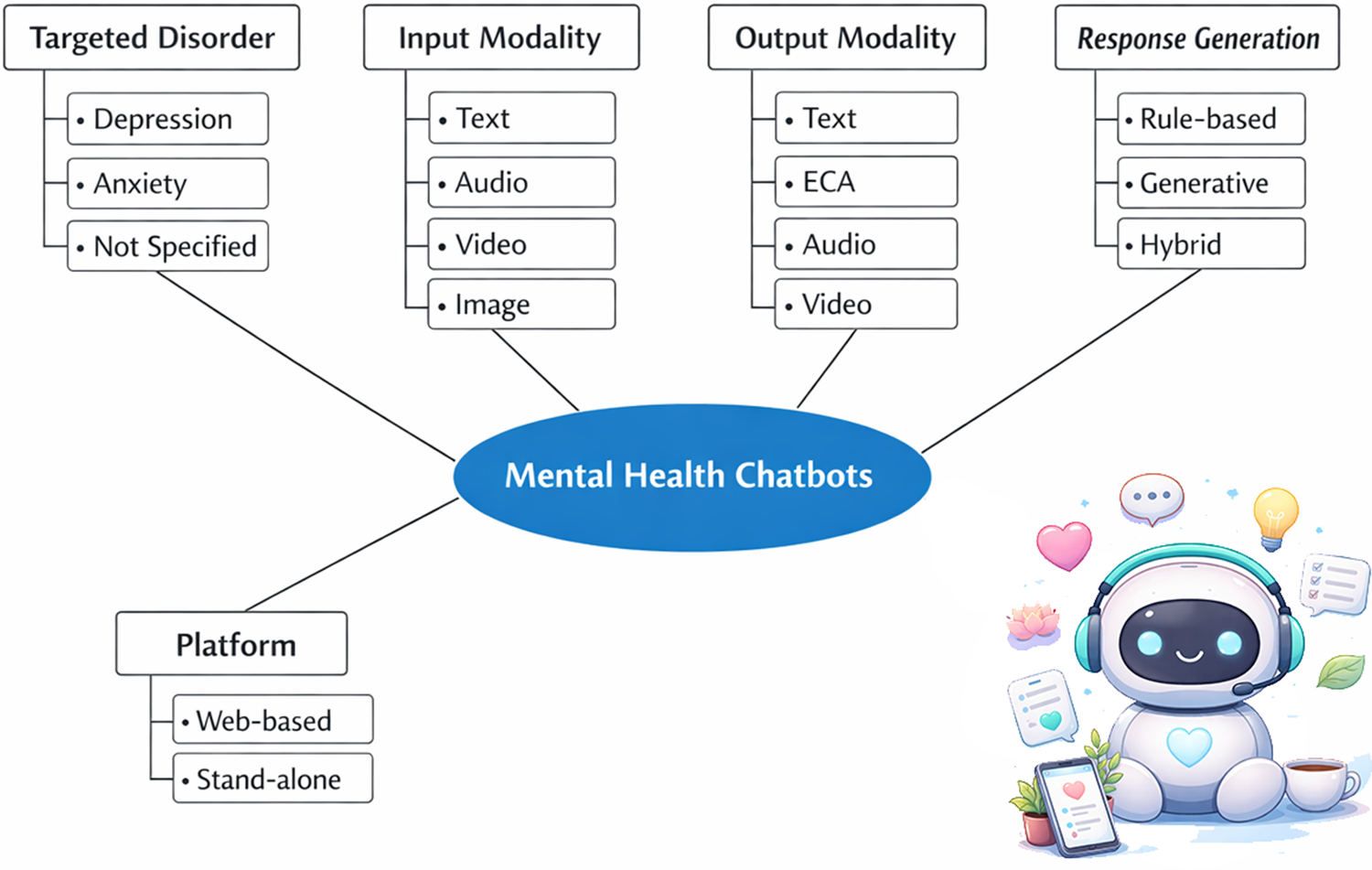

Table 2 presents the findings of the thematic analysis that explored and described the characteristics of 138 chatbots for mental health mentioned within the reviewed studies in this paper, based on five categories: targeted disorder, input modality, output modality, platform and response generation. These categories represent the key aspects of chatbot design and functionality that are relevant to mental health interventions. Figure 3 presents the overall features of the mental health chatbots. Supplementary Appendix 3 (Study Chatbots) contains the detailed information about the chatbots (Abd-Alrazaq et al., Reference Abd-Alrazaq, Alajlani, Alalwan, Bewick, Gardner and Househ2019; Abd-Alrazaq et al., Reference Abd-Alrazaq, Rababeh, Alajlani, Bewick and Househ2020; Abd-Alrazaq et al., Reference Abd-Alrazaq, MBMMBAP, Ali, KDrn, BMBAMAP and Househ2021; Ahmed et al., Reference Ahmed, Hassan, Aziz, Abd-Alrazaq, Ali, Alzubaidi, Al-Thani, Elhusein, Siddig, Ahmed and Househ2023; Anaduaka et al., Reference Anaduaka, Oladosu, Katsande, Frempong and Awuku-Amador2025; Baek et al., Reference Baek, Cha and Han2025; Balan et al., Reference Balan, Dobrean and Poetar2024; Bérubé et al., Reference Bérubé, Schachner, Keller, Fleisch, F, Barata and Kowatsch2021; Bragazzi et al., Reference Bragazzi, Crapanzano, Converti, Zerbetto and Khamisy-Farah2023; Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Lee, Lin and Cheng2024; Dehbozorgi et al., Reference Dehbozorgi, Zangeneh, Khooshab, Nia, Hanif, Samian, Yousefi, Hashemi, Vakili, Jamalimoghadam and Lohrasebi2025; Du et al., Reference Du, Ren, Meng, He and Meng2025; Farzan et al., Reference Farzan, Ebrahimi, Pourali and Sabeti2025; X Feng et al., Reference Feng, Tian, Ho, Yorke and Hui2025; Y Feng et al., Reference Feng, Hang, Wu, Song, Xiao, Dong and Qiao2025; Gaffney et al., Reference Gaffney, Mansell and Tai2019; Hawke et al., Reference Hawke, Hou, Nguyen, Phi, Gibson, Ritchie, Strudwick, Rodak and Gallagher2025; He et al., Reference He, Yang, Qian, Li, Su, Zhang and Hou2023; Im and Woo, Reference Im and Woo2025; Jabir et al., Reference Jabir, Martinengo, Lin, Torous, Subramaniam and Tudor Car2023; Joshi et al., Reference Joshi, Ghogare and Madavi2025; Kim, Reference Kim2024; Li et al., Reference Li, Zhang, Lee, Kraut and Mohr2023; Li et al., Reference Li, Li, Hu, Ma, Chan and Yorke2025; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Martinengo, Jabir, Ho, Car, Atun and Tudor Car2023; Mansoor et al., Reference Mansoor, Hamide and Tran2025; Martinengo et al., Reference Martinengo, Jabir, Goh, Lo, Ho, Kowatsch, Atun, Michie and Tudor Car2022; Nyakhar and Wang, Reference Nyakhar and Wang2025; Ogilvie et al., Reference Ogilvie, Prescott and Carson2022; Otero-González et al., Reference Otero-González, Pacheco-Lorenzo, Fernández-Iglesias and Anido-Rifón2024; Vaidyam et al., Reference Vaidyam, Linggonegoro and Torous2021; Vaidyam et al., Reference Vaidyam, Wisniewski, Halamka, Kashavan and Torous2019; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Cheung, Zhang, Zhang, Qin and Xie2025).

Table 2. Findings from the thematic analysis

Figure 3. Overall features of mental health chatbots.

Targeted disorder

This category refers to the specific mental health conditions that the chatbots were designed to address or prevent. The targeted disorders mentioned in the included studies spanned a wide range of mental health and well-being conditions, including depression, anxiety and stress, often appearing alone or in combination with loneliness, burnout, sleep problems or self-esteem issues. In this regard, depression was the target disorder for ~40% of the chatbots, anxiety for 31% and stress for nearly 10% of the chatbots included in the study. The data also included broader mood disorders, such as major depression and bipolar disorder, alongside trauma- and fear-related conditions like posttraumatic stress disorder and acrophobia. Several neurodevelopmental and social conditions were addressed, including autism, social communication disorders, social disorders and behavioral issues. Sleep-related disorders, particularly insomnia, appeared both independently and in combination with mood disorders. The dataset further covered substance use-related conditions, such as substance use disorder, addiction and cigarette smoking cessation, as well as eating- and body-related issues, including eating disorders, eating/feeding disorders, body image concerns and diet-related problems. In addition, there were categories related to chronic and physical health-associated mental health concerns, such as chronic disorders, lifestyle disorders, mental health issues of cancer patients and perinatal women’s mental health issues, while a substantial number of chatbots were labeled with “not specified,” indicating a general or nondiagnosis-specific mental health focus.

Input modality

This category refers to the way that the user provided information or feedback to the chatbot, such as text, audio, image or video. In this regard, text was used as the input modality in 91% of the chatbots, audio in 34%, video in 1% chatbots and image in merely 0.7% of the chatbots.

Output modality

This category refers to the way that the chatbot delivered information or feedback to the user, such as text, audio, video or an embodied conversational agent (ECA). An ECA is a graphical representation of a human or an animal that could interact with the user through speech and gestures. In this regard, text served as the output modality for 91% of the study chatbots, audio for 13%, video for 2% and ECA for 28% of the chatbots.

Platform

This category refers to the type of device or software that the chatbot runs on or requires to function. The data could be classified into two main types of platforms: web-based and stand-alone. Web-based platforms are those that require an internet connection and a web browser to access the chatbot. Stand-alone platforms are those that do not require an internet connection or a web browser and can be installed or downloaded on a device. In this regard, ~70% of the chatbots were web-based, while 28% operated as stand-alone systems.

Response generation

This category refers to how the chatbot produced its responses to the user’s inputs. The data could be classified into three main types of response generation: rule-based, generative and hybrid. Rule-based response generation is when the chatbot follows a set of predefined rules or scripts to select or construct its responses from a fixed pool of options. Generative response generation is when the chatbot uses natural language processing techniques to generate its responses from scratch based on the user’s inputs and context. Hybrid response generation is when the chatbot combines both rule-based and generative methods to produce its responses. In this regard, ~45% of the study chatbots employed rule-based, 18% utilized generative and 14% implemented hybrid models.

Discussion

In this section, the characteristics of the chatbots, as mentioned in the results section, are examined. The analysis encompasses various aspects, such as the chatbot’s targeted disorder, input modality, output modality, platform and response generation.

Targeted disorder

According to the study findings, the primary target disorders of the chatbots examined in the included studies were depression (40%) and anxiety (31%). In this regard, it is understandable that most of the mental health chatbots are related to depression, anxiety and stress disorders, since it has been shown that depression, anxiety and stress are associated with social isolation and loneliness (Hidaka, Reference Hidaka2012; Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Danese, Wertz, Odgers, Ambler, Moffitt and Arseneault2016; Ratnani et al., Reference Ratnani, Vala, Panchal, Tiwari, Karambelkar, Sojitra and Nagori2017); and that chatbots can provide services without requiring any physical presence of the patient in the clinic or in society (Parviainen and Rantala, Reference Parviainen and Rantala2022). In this regard, an understanding of the impact of such technologies on the quality and outcomes of care delivery has been shown to be a key determinant of their utilization (Izadi et al., Reference Izadi, Bahrami, Khosravi and Delavari2023).

Individuals diagnosed with autism have been observed to develop severe and persistent impairments in social, communication and repetitive/stereotyped behaviors, which may make remote healthcare services, especially mental health chatbots, a preferable option for them to access their desired medical care (Parr et al., Reference Parr, Dale, Shaffer and Salt2010). Moreover, as misconceptions regarding specific diseases and treatments perpetuate stigma within certain societies, mobile health (mHealth) applications have emerged as a viable solution (Khosravi et al., Reference Khosravi, Azar and Izadi2024a).

Although chatbots yield positive mental health outcomes, evidence indicates potential harms. Interactions may reinforce delusions or trigger psychosis in vulnerable individuals with genetic or stress-related predispositions, exacerbate bipolar mania by validating elevated moods or collude with psychotic fantasies. Generative artificial intelligence (AI) risks hallucinations, biases and harmful advice, worsening conditions via misdiagnosis or unsafe encouragement (AlMaskari et al., Reference AlMaskari, Al-Mahrouqi, Al Lawati, Al Aufi, Al Riyami and Al-Sinawi2025; Hipgrave et al., Reference Hipgrave, Goldie, Dennis and Coleman2025; Hua et al., Reference Hua, Siddals, Ma, Galatzer-Levy, Xia, Hau, Na, Flathers, Linardon, Ayubcha and Torous2025). Hence, a situation analysis is required before designing and financing the production of chatbots for mental health disorders, in order to investigate and identify the most in need groups of patients who can benefit from chatbots and to adjust the quantity and diversity of chatbots according to the needs of these groups.

Input modality

As indicated by the study findings, the input modalities of the chatbots were classified into several categories, including text, audio, image and video. In this regard, the primary input modality of the chatbots was text, with ~91% of the chatbots utilizing text as their input method. In this regard, evidence indicates that text-based interfaces can be readily integrated with portals, messaging platforms and electronic health records, while facilitating data capture, auditing and algorithm development (Hindelang et al., Reference Hindelang, Sitaru and Zink2024; Barreda et al., Reference Barreda, Cantarero-Prieto, Coca, Delgado, Lanza-León, Lera, Montalbán and Pérez2025; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Ellis, Dellavalle, Akerson, Andazola, Campbell and DeCamp2025). Text-based chatbots are consistent with existing patient behaviors, as many individuals are already accustomed to interacting with healthcare services through secure messaging and portals (Bai et al., Reference Bai, Wang, Zhao, Feng, Ma and Liu2025; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Ellis, Dellavalle, Akerson, Andazola, Campbell and DeCamp2025). Furthermore, text interfaces are more easily standardized and processed using current natural language processing techniques and large language models (Singh et al., Reference Singh, Sillerud and Singh2023; Barreda et al., Reference Barreda, Cantarero-Prieto, Coca, Delgado, Lanza-León, Lera, Montalbán and Pérez2025; Loftus et al., Reference Loftus, Haider and Upchurch2025).

However, one study showed that voice-based interactions improved social bonding and did not raise discomfort, unlike text-based interactions. Even though this phenomenon is related to the input modality as well as the output modality, wrong expectations about discomfort or bonding could cause suboptimal choices for a text-based platform. Misjudging the outcomes of using different communication platforms could lead to preferences for platforms that do not enhance either one’s own or others’ well-being (Kumar and Epley, Reference Kumar and Epley2021). Therefore, the preferences and needs of the patients should be the basis for the design and production of chatbots for mental health services, as some groups of mental health patients may face difficulties in using chatbots that only accept written text as input and output.

Output modality

The study findings indicated that text (91%) was the primary output modality employed by the chatbots reported in the literature. Meanwhile, only 28% of the chatbots were ECAs. In this regard, several healthcare contexts have demonstrated the effectiveness of ECAs in improving disorders, such as stress management and mental health (Gardiner et al., Reference Gardiner, McCue, Negash, Cheng, White, Yinusa-Nyahkoon, Jack and Bickmore2017; Provoost et al., Reference Provoost, Lau, Ruwaard and Riper2017). Additionally, ECAs have been found to create a sense of companionship with patients and reduce loneliness, which is a risk factor for various mental health disorders (Hawkley and Cacioppo, Reference Hawkley and Cacioppo2010). Furthermore, applying patient-centered communication features within ECAs can enhance user satisfaction and engagement with healthcare services (Borghi et al., Reference Borghi, Leone, Poli, Becattini, Chelo, Costa, De Lauretis, Ferraretti, Filippini, Giuffrida, Livi, Luehwink, Palermo, Revelli, Tomasi, Tomei and Vegni2019; Kwame and Petrucka, Reference Kwame and Petrucka2021). Since several articles have indicated that the user’s perception of healthcare services is influenced by the behavior, language, emotional expression, virtual environment and embodiment of ECAs (Qiu and Benbasat, Reference Qiu and Benbasat2009; Kulms et al., Reference Kulms, Kopp, Krämer, Bickmore, Marsella and Sidner2014; Cerekovic et al., Reference Cerekovic, Aran and Gatica-Perez2016; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Phan, Bolas and Krum2016; Hoegen et al., Reference Hoegen, van der Schalk, Lucas and Gratch2018).

Several aspects are related to patient-centered communication: (1) exploring and comprehending patient perspectives, such as concerns, ideas, expectations, needs, feelings and functioning; (2) understanding the patient within his or her specific psychosocial and cultural contexts; and (3) achieving a common understanding of patient problems and the treatments that are consistent with patient values (Epstein and Street, Reference Epstein and Street2007).

The input and output modalities of chatbots should be designed according to the preferences and needs of the patients, especially for mental health patients, as some of them may have challenges with certain modalities of chatbots. Moreover, as discussed before, this phenomenon can potentially improve patient-centered communication in mental health services.

Platform

The study findings indicated that the majority of chatbots reported in the literature were web-based (70%). In this regard, there are significant and enduring gaps in the access and usage of digital technologies among different regions and communities, which are exacerbated by the increasing complexity and functionality of devices and connectivity. This leads to a situation where those groups that can leverage the full potential of digital technologies have a relative advantage over others. This phenomenon results in unequal access to digital technologies among different societies with diverse socioeconomic backgrounds (Selwyn, Reference Selwyn2004). Therefore, chatbots that have their own platforms seem to be more advantageous than chatbots that depend on web-based platforms in such settings. The term “Digital divide” is used for such a phenomenon of inequality among different societies with diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. The term connotes different access and use of digital tech by different groups. It is not a simple gap, rather a complex range of users who change over time based on infrastructure, environment and personal factors (Selwyn, Reference Selwyn2004; Fox, Reference Fox2016).

The manufacturers and designers of chatbots should consider the digital divide within societies, as it is a critical factor that can enhance the equality and accessibility of services, especially in the mental health domain. As mentioned earlier, providing chatbots that operate on stand-alone platforms can be a major strategy to achieve this vision.

Response generation

The study findings indicated that the majority of chatbots reported in the literature employed rule-based systems (45%). In this regard, rule-based chatbots may appeal to autistic individuals, as such chatbots operate in a consistent and predictable manner. Since autistic individuals may experience discomfort when they encounter new and unfamiliar situations that are not repetitive (American Psychiatric Association and Association, 2013). On the other hand, other types of patients may prefer chatbots that are generative or hybrid, as these chatbots emulate human behavior and emotions, which have been shown to enhance rapport, motivation and engagement (Giger et al., Reference Giger, Piçarra, Alves-Oliveira, Oliveira and Arriaga2019).

As mentioned earlier, the needs and preferences of each group of patients should be considered in the design and production of chatbots for mental health services, as this is a key strategy to improve the quality and satisfaction of the services. As discussed earlier, different forms of response generation of mental health chatbots may have varying and contrasting effects on different groups of patients, depending on their preferences for the type of care they receive. Some patients may favor chatbots that are rule-based, precise and repetitive, while others may favor chatbots that are innovative, emotionally responsive and motivating. Therefore, it is essential to understand the needs and expectations of the target users before developing chatbots for mental health services.

Overall, evidence indicates greater utilization of mental health chatbots among underserved populations relative to others. These tools address access barriers via cost-effectiveness, round-the-clock availability and stigma mitigation, particularly in low-resource settings and among refugees (Haque and Rubya, Reference Haque and Rubya2023; Khosravi et al., Reference Khosravi, Azar and Izadi2024a; Coelho et al., Reference Coelho, Pécune, Micoulaud-Franchi, Bioulac and Philip2025; Han and Zhao, Reference Han and Zhao2025; Pozzi and De Proost, Reference Pozzi and De Proost2025). However, ethical considerations must be addressed before deploying chatbots, particularly within the critical domain of mental health. In this regard, ethical considerations play a crucial role in the adoption of electronic mental health technologies, including chatbots. In this context, critical issues such as informed consent and the protection of privacy must not be overlooked (Khosravi et al., Reference Khosravi, Izadi and Azar2025). Moreover, algorithmic biases, stemming from training data that mirrors societal prejudices, result in discriminatory advice, stigmatization of conditions such as schizophrenia and diminished empathy toward ethnic minorities and marginalized groups. These biases exacerbate mental health disparities through inaccurate responses and potentially harmful recommendations (Khawaja and Bélisle-Pipon, Reference Khawaja and Bélisle-Pipon2023). Another critical concern is the risk of substitution, which warrants careful attention. AI-driven chatbots must not replace human professionals in delivering health services (Altamimi et al., Reference Altamimi, Altamimi, Alhumimidi, Altamimi and Temsah2023; Khawaja and Bélisle-Pipon, Reference Khawaja and Bélisle-Pipon2023; Greš and Staver, Reference Greš and Staver2025). In such a context, developers must deliver clear disclosures on data collection, storage, usage and sharing before interactions, ensuring comprehension by vulnerable mental health users. Continuous consent via opt-in prompts for sensitive data and deletion options upholds autonomy and other ethical standards (Coghlan et al., Reference Coghlan, Leins, Sheldrick, Cheong, Gooding and D’Alfonso2023; Talebi Azadboni et al., Reference Talebi Azadboni, Solat, Hematti and Rahmani2025). Moreover, anonymization through data masking, encryption (e.g., secure enclaves) and blockchain identity management mitigates breaches and re-identification. Meanwhile, regular audits, minimal sharing, transparency reports and automated privacy prompts foster trust and user control (Iwaya et al., Reference Iwaya, Babar, Rashid and Wijayarathna2023; Talebi Azadboni et al., Reference Talebi Azadboni, Solat, Hematti and Rahmani2025). Finally, chatbots should be considered supplementary tools to support, rather than replace, human professionals in mental health services (Khawaja and Bélisle-Pipon, Reference Khawaja and Bélisle-Pipon2023).

Implications and limitations

This study had some implications for mental health chatbot manufacturers, policymakers and future researchers. First, this paper emphasized the need to design and produce chatbots for mental health services that suit the preferences and needs of the patients. This involves considering the specific disorder, the input and output modalities, the platform and the response generation of the chatbots. Second, the research also suggested that chatbots can be beneficial for individuals who suffer from social isolation and loneliness due to mental health disorders, such as depression, anxiety and stress, as well as for individuals with autism who have impairments in social, communication and repetitive/stereotyped behaviors. Furthermore, the research indicated that the digital divide within societies should be taken into account when designing and producing chatbots for mental health services, and that providing chatbots that work on independent platforms (stand-alone chatbots) can be a key strategy to improve the equality and accessibility of the services. The study also examined ethical challenges in mental health chatbot deployment and proposed strategies to address them. These insights offer valuable guidance for health policymakers, managers implementing chatbots in healthcare services and manufacturers seeking to strengthen ethical standards for improved system integration.

This study had some limitations. First, it provided a limited overview of the current state of mental health chatbots and did not assess their effectiveness or impact on patient outcomes. Second, it also did not examine the cost-effectiveness or feasibility of implementing chatbots for mental health services in various settings. Moreover, it did not investigate the potential risks or negative consequences of using chatbots for mental health services due to the limited scope, data and time at hand of the researchers. Future researchers can address these issues.

Conclusion

This study conducted a thematic analysis on the existing data on mental health chatbots and provided some insights into the technical features of mental health chatbots, such as their targeted disorders, input and output modalities, platform and response generation. The research emphasized the need to design and produce chatbots for mental health services that suit the preferences and needs of the patients. Chatbots can be beneficial for individuals who suffer from social isolation and loneliness due to mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety and stress. Chatbots may also be an alternative option for individuals with autism who have impairments in social, communication and repetitive/stereotyped behaviors. The research also indicated that the digital divide within societies should be taken into account when designing and producing chatbots for mental health services, and that providing chatbots that work on independent platforms can be a key strategy to improve the equality and accessibility of the services. The study also addressed ethical concerns regarding the use of chatbots in mental health services, while proposing solutions and highlighting their high utility for underserved populations. However, the research also had some limitations, such as the lack of information on the effectiveness or impact of chatbots on patient outcomes, their cost-effectiveness or feasibility in different contexts and potential risks or negative consequences of using chatbots for mental health services.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2026.10144.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2026.10144.

Data availability statement

The research data can be accessed by contacting the corresponding author of the paper.

Author contribution

MK conducted the search within the databases, extracted the data and conducted the analysis. MK wrote the introduction, methods, results and discussion sections. RI validated the data collection process and revised the text of the manuscript. The final version of the manuscript was approved by all of the authors.

Financial support

There is no funding regarding this research.

Competing interests

The author declares none.