Introduction

Ischaemic heart disease (IHD) is a leading global cause of illness and death (Benjamin et al., Reference Benjamin, Muntner, Alonso, Bittencourt, Callaway, Carson, Chamberlain, Chang, Cheng, Das, Delling, Djousse, Elkind, Ferguson, Fornage, Jordan, Khan, Kissela, Knutson, Kwan, Lackland, Lewis, Lichtman, Longenecker, Loop, Lutsey, Martin, Matsushita, Moran, Mussolino, O’flaherty, Pandey, Perak, Rosamond, Roth, Sampson, Satou, Schroeder, Shah, Spartano, Stokes, Tirschwell, Tsao, Turakhia, Vanwagner, Wilkins, Wong and Virani2019). While IHD incidence has declined in high-income countries, it remains high in middle- and low-income nations, including India, which faces an IHD epidemic (Roth et al., Reference Roth, Johnson, Abajobir, Abd-Allah, Abera, Abyu, Ahmed, Aksut, Alam, Alam, Alla, Alvis-Guzman, Amrock, Ansari, Ärnlöv, Asayesh, Atey, Avila-Burgos, Awasthi and Murray2017; Kalra et al., Reference Kalra, Jose, Prabhakaran, Kumar, Agrawal, Roy, Bhargava, Tandon and Prabhakaran2023). Indian people bear the highest burden of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and myocardial infarction, with cases increasing 1.4 times from 1990 to 2018 (Sreeniwas Kumar and Sinha, Reference Sreeniwas Kumar and Sinha2020). A number of studies have shown that individuals of Indian descent are at greater risk of developing IHD at a younger age and tend to have worse long-term outcomes compared to other ethnic groups (Kalra et al., Reference Kalra, Jose, Prabhakaran, Kumar, Agrawal, Roy, Bhargava, Tandon and Prabhakaran2023, Sreeniwas Kumar and Sinha, Reference Sreeniwas Kumar and Sinha2020). Indians develop IHD about a decade earlier than others, with 52% of IHD deaths occurring before age 70, compared to 23% in Western populations (Harikrishnan et al., Reference Harikrishnan, Leeder, Huffman, Jeemon and Prabhakaran2014). Early-onset IHD, traditionally seen after age 45, is increasingly observed in Indian people under 35 (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Mp, Kategari, Batra, Gupta, Bansal, Yusuf, Goswami, Das, Saijpaul, Mahajan, Mukhopadhyay, Trehan and Tyagi2020). This high prevalence also persists in Indian migrant populations, as has been widely documented in Canada, the USA, and various European countries (Iyer et al., Reference Iyer, Shah, Hastings, Hu, Rodriguez, Boothroyd, Krishnan, Falasinnu and Palaniappan2019, Saeed et al., Reference Saeed, Kanaya, Bennet and Nilsson2020).

Managing modifiable risk factors for IHD, can reduce risk by up to 44% (Dimovski et al., Reference Dimovski, Orho-Melander and Drake2019), highlighting the importance of population-wide prevention strategies (Howse et al., Reference Howse, Crosland, Rychetnik and Wilson2021). However, motivating asymptomatic individuals to adopt lifestyle changes is challenging without a clear sense of urgency (Ramôa Castro et al., Reference Ramôa Castro, Oliveira, Ribeiro and Oliveira2017). Perceived personal risk plays a crucial role, as those who see themselves as vulnerable are more likely to seek healthcare and screening (Sheeran et al., Reference Sheeran, Harris and Epton2014, Stol et al., Reference Stol, Hollander, Damman, Nielen, Badenbroek, Schellevis and De Wit2020). Effective prevention requires integrating knowledge of risk factors with an understanding of perceived risk, as misjudging it can hinder early detection and management (Saeidi and Komasi, Reference Saeidi and Komasi2018). Behavioural change, therefore, depends on individual awareness, risk perception, and proactive health-seeking behaviour (Saeidi and Komasi, Reference Saeidi and Komasi2018).

These considerations are particularly relevant in diverse nations like Australia, where 30% of its 26 million people in 2019 were immigrants (United Nations, 2015; Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020b; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Ghisi, Shi, Pakosh, Main and Gallagher2025). Understanding how migrants perceive their risk of IHD is essential to informing equitable healthcare and culturally responsive interventions. The health implications of migration are increasingly recognized in global public health policies. Migration is a significant determinant of health, but its complex interplay with factors such as cultural shifts, economic pressures, reasons for migration, and forced displacement remains poorly understood, particularly in the context of chronic diseases like cardiovascular conditions (Wickramage et al., Reference Wickramage, Vearey, Zwi, Robinson and Knipper2018; Orcutt et al., Reference Orcutt, Spiegel, Kumar, Abubakar, Clark and Horton2020). Social inequalities further weaken migrants’ psychosocial and mental well-being, increasing their vulnerability to chronic illness (Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Torres, Zwi, Khalema and Palaganas2019).

The focus of this study is on Indian migrants as a key subgroup within Australia’s diverse migrant population. For the purposes of this study, Indian migrants are defined as individuals of Indian origin who were born in India and later migrated to Australia. Indian migrants represent 10.4% of the total migrant population in Australia and they face a disproportionate burden of IHD. By 2031, Indian migrant population is projected to reach 1.4 million in Australia, reinforcing their substantial presence (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2018). These trends highlight the need to address their unique health challenges, particularly regarding IHD.

Research on how Indian people perceive IHD risk is limited. Most studies are quantitative, relying on perception scales, or small-scale qualitative studies (Kaur et al., Reference Kaur, Abu-Qamar, Rashidi, Mckay and Saunders2025). Only one study addresses personal susceptibility to IHD in this population (Dayal and Singh, Reference Dayal and Singh2017); however, its findings are limited to individuals residing in India and therefore may not be generalizable to migrant populations. This highlights the need for more research to explore IHD risk perception in this group and this study reports a qualitative exploration of the issue from an individual perspective.

Aim

The aim of this study is to understand how Indian migrants in metropolitan Melbourne perceive their personal IHD risk and the factors shaping these perceptions.

Methods

Study design and ethics approval

A qualitative descriptive study design was implemented for this study. This approach is widely used in qualitative research, as it is not constrained by a predefined theoretical framework, thereby allowing participants’ perspectives to be authentically represented and facilitating the generation of rich, comprehensive data. (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Sefcik and Bradway2017; Furidha, Reference Furidha2023). This approach enables the phenomenon to be observed in its natural state, as it would occur without the influence of research intervention (Sandelowski, Reference Sandelowski2000). Consequently, no theoretical framework was employed in this study, as the researcher aimed to explore the perceptions of the target population without constraining them within predefined frameworks or theories. However, the study findings have been discussed in the context of COM-B (Michie et al., Reference Michie, Van Stralen and West2011). Ethics approval was granted by the university’s Human Research Ethics Committee on 23 July 2021 as a low-risk study (REMS NO: 2021-02449-KAUR).

Setting and sample

The target population for this study was first-generation Indian migrants living in Australia. There are 721,000 Indians living in Australia, with an average age of 34 years (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020a). Victoria is home to the largest number of Indian migrants (170,000), with an average age of 31 years. The demographics of Victorian Indians are comparable to the rest of Australia in terms of education, professions and socioeconomic status (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020c).

A convenience sampling approach was employed to recruit to recruit first-generation Indian migrants living in Australia. Convenience sampling is a commonly employed technique in non-experimental research due to its cost-effectiveness and ease of implementation (Golzar et al., Reference Golzar, Noor and Tajik2022). It is particularly advantageous in studies targeting hard-to-reach populations, such as minority groups or migrants, where traditional sampling methods may be impractical or resource-intensive (Setia, Reference Setia2016, Wang and Cheng, Reference Wang and Cheng2020).

Therefore, a Community Advisory Board (CAB) was formed as part of consumer involvement to enhance community engagement and provide cultural insights, reflecting the diversity of the target population (Kubicek and Robles, Reference Kubicek and Robles2016). To ensure a broader representation of the Indian community in Victoria (Mlambo et al., Reference Mlambo, Vernooij, Geut, Vrolings, Shongwe, Jiwan, Fleming and Khumalo2019), the opportunity to be part of the CAB was extended to all community members. Four members representing each major Indian religion (Hindu, Sikh, Muslim and Christian) participated in the CAB. Members of the CAB reviewed study materials, consent forms, and recruitment posters and supported recruitment. They were also consulted during the data analysis and the interview translation process. Despite COVID-19 lockdowns preventing direct meetings, the CAB played a crucial role in ensuring community engagement and cultural sensitivity.

Recruitment

The study included first-generation adult Indian migrants aged 31 or over residing in the metropolitan Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Individuals aged 31 years or older were selected as the inclusion criterion for this study for several reasons. Firstly, the average age of Indian residents in Victoria at the time of data collection was 31 years and the median age of Indian-born migrants in Australia is approximately 35.9 years (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020c). Establishing 31 years as the minimum age ensured that the study sample aligned closely with the demographic profile of the Indian migrant community. Additionally, this age group represents a critical period for early intervention strategies targeting populations at higher risk of developing ischaemic heart disease, thereby enhancing the study’s relevance and potential impact (Heart Foundation, 2023). Other epidemiological studies on cardiovascular health have also adopted this approach to recruiting individuals within similar age groups (Liang et al., Reference Liang, Wells, Jackson, Choi, Mehta, Chung, Gao and Poppe2024, Wu et al., Reference Wu, Wang, Wang, Feng, Li, Lin, Ruan, Nie, Tian and Jin2025).

Migrants with a prior diagnosis of IHD, diabetes, hypertension, or hypercholesterolaemia were excluded, as were those unable to communicate in English, Punjabi, Hindi, or Urdu. Although a substantial proportion of the Australian population may have undiagnosed hypercholesterolaemia, the rationale for excluding individuals with diagnosed conditions was to avoid potential bias, as they may have previously received education regarding IHD, which could influence their perceptions. Participants who spoke other major Indian languages commonly represented in Australia, such as Gujarati, Malayalam, Tamil, and Telugu, were not included in this study. This decision was based on the linguistic limitations of the researcher, who did not speak these languages.

This study forms part of a larger mixed methods investigation and the qualitative data were collected concurrently with the quantitative data for the overarching study. The posters with QR codes were displayed in public places and shared on social media. The researcher participated in a live interview with one radio station to promote the study. The same radio station also had announcements about the study every day three weeks. Another radio station promoted the study by publishing an article in both English and Punjabi on its social media platform, accompanied by a recorded interview with the researcher. The CAB supported recruitment by sharing survey links and promotional materials, while community members spread posts to friends and family. Individuals who completed the online survey were invited at the conclusion of the survey to contact the researcher if they wished to participate in the qualitative component. Participants contacted the first author via telephone or email to arrange an interview, which was conducted at a public location convenient to the participant. All interviews were conducted by the first author, a woman of Indian origin who is a cardiac nurse and doctoral student. Participants received detailed study information prior to participation and provided written informed consent.

Data collection

Data was collected from August 2021 to May 2022. Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted using an interview guide. An interview guide comprising six open-ended questions, that explored participants’ perceptions, general IHD knowledge, personal risk factors, and perceived likelihood of developing IHD, was developed by the first author in alignment with the research questions and with consideration of the study population (see supplementary file A). The guide was refined in consultation with the co-authors and the CAB. To establish feasibility of using this tool and quality assurance of the collected data, it was pilot-tested with members of the advisory board and three individuals from the Indian community who were not part of the study. This process ensured clarity, cultural appropriateness, and relevance of the questions. (Creswell and Poth, Reference Creswell and Poth2016, Kallio et al., Reference Kallio, Pietilä, Johnson and Kangasniemi2016).

Interviews were conducted in person or via Microsoft Teams, with most being face-to-face and three online due to COVID-19 restrictions. Each interview was conducted for a minimum duration of one hour in a quiet setting, such as a park, café, or place of worship. To ensure privacy and minimize external influence, only the participant and the researcher were present during each session. Participants spoke Punjabi, Hindi, or English, often mixing languages for comfort. All interviews were audio recorded electronically and afterward, the researcher verified recordings, added observations in the filed notes, and clarified topics as needed.

Data collection and analysis were conducted concurrently, with interview transcripts transcribed and coded iteratively. The first author reviewed coded data throughout the process to monitor the emergence of new concepts and themes. By the 16th interview, no new themes were identified, suggesting that saturation had been reached. Following discussion between the research team, data collection was extended to 19 interviews to ensure robustness, at which point thematic saturation was formally declared (Rahimi and khatooni, Reference Rahimi and Khatooni2024). One additional interview was conducted as a precautionary measure, which confirmed that no further themes emerged.

Data analysis methods

Qualitative content analysis (QCA) following Kuckartz (Reference Kuckartz2014) approach was applied manage textual data. The researcher manually transcribed interviews to retain cultural context across multiple languages. Participants reviewed transcripts via email and confirmed accuracy via text or call.

A hybrid coding technique was applied, combining data-driven and concept-driven categories for a comprehensive view (Kaur et al., Reference Kaur, Abu-Qamar, Rashidi, McKay and Saunders2025, Shreier, Reference Shreier, Atkinson, Delamont, Cernat, Sakshaug and Williams2019). Main categories were mostly deductive, with additional ones added inductively. Most subcategories were inductive, some further subdivided. NVivo was used to organize categories and themes were derived with direct quotes included. Analysis was conducted in original languages, with findings reported in English for broader reach. The first author, a native speaker of the study languages, carried out the analysis and translated the findings into English for reporting. To ensure accuracy and preserve the intended meaning, bilingual members of the CAB were consulted in instances where cultural context or direct translation was ambiguous. Any discrepancies were resolved through collaborative discussion to maintain cultural and contextual integrity (van Nes et al., Reference Van Nes, Abma, Jonsson and Deeg2010).

Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness was established with reference to credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability, the established ‘gold standard’ in qualitative research (Lincoln and Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985, Tashakkori and Teddlie, Reference Tashakkori and Teddlie2010). These principles were applied throughout the study. Furthermore, reflexivity was maintained throughout all stages of the study, given the researcher’s close relationship with the cultural background of the study participants (Olmos-Vega et al., Reference Olmos-Vega, Stalmeijer, Varpio and Kahlke2023). Semi-structured interviews were designed and conducted in line with these criteria to support robustness. Credibility was maintained by using a pilot tested interview guide and allowing sufficient interview time, using a standard transcription protocol to reduce bias (Nascimento and Steinbruch, Reference Nascimento and Steinbruch2019), and securely storing transcripts, field notes, journals, and meeting records. Transferability was supported through detailed descriptions of the study setting and participants, while dependability was enhanced by providing a transparent account of the methodology (Moon et al., Reference Moon, Brewer, Januchowski-Hartley, Adams and Blackman2016). In this study, confirmability was ensured through an audit trail documenting the data collection and analysis process, including observation notes, reflective journals, interview records, coding drafts, and interpretation logs.

Given the researcher’s shared cultural background with participants, reflexivity was addressed by maintaining a reflective journal and actively bracketing personal beliefs to minimize bias, particularly when interviewing participants from the same native state (Korstjens and Moser, Reference Korstjens and Moser2018; Kaur et al., Reference Kaur, Abu-Qamar, Rashidi, McKay and Saunders2025). As part of reflexivity, the researcher acknowledges that her own language background shaped the inclusion criteria and may have influenced the cultural perspectives represented in the study.

NVivo software (Lumivero, 2023) was employed for data management and analysis, enhancing rigour (Maher et al., Reference Maher, Hadfield, Hutchings and De Eyto2018). Data were carefully cleaned and de-identified prior to analysis to reduce bias. Finally, rigour was further strengthened through member checking with participants (Carlson, Reference Carlson2010; Thomas, Reference Thomas2017; Candela, Reference Candela2019). All participants were given the opportunity to review and verify their interview transcripts prior to the commencement of data analysis, as part of a member-checking strategy aimed at enhancing the credibility of the findings. Transcripts were distributed via email and participants were notified of their delivery through a follow-up phone call. While most participants responded by phone to confirm receipt and provide feedback, the researcher initiated follow up calls for those who did not respond within a week.

Results

Participant profile

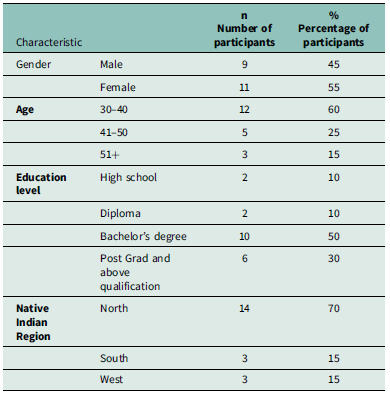

Twenty interviews were conducted with first-generation Indian migrants living in various parts of Melbourne. The main languages spoken by the interviewees were Punjabi, Hindi and English. Most participants were natives of the Punjab state in India (n = 9). The rest came from Kerala (n = 3), Maharashtra (n = 3), Haryana (n = 3), Uttar Pradesh (n = 1), and Delhi (n = 1). The participants ranged in age from 32 to 70 years-, with an average age of 42.1 years. More than half participants were females (n = 11). The length of stay in Australia ranged from 2 to 26 years (average 11.5 years). The level of education ranged from high school to PhD with most participants holding a bachelor’s degree. Table 1 presents a demographic summary of the study participants.

Table 1. Participants demographics

Perceptions of personal risk of developing IHD

The QCA identified four main themes and related sub-themes, which are described in detail below and supported by exemplars. The main themes were developed from sub-themes as described below.

Figure 1 presents the themes and sub-themes.

Figure 1. Themes and sub-themes.

Awareness of IHD and associated risk factors

Participants shared their knowledge and understanding of heart diseases, three sub-themes were identified: understanding of IHD; the risk of IHD due to genetics and aging; and the risk of IHD due to lifestyle factors.

i) Understanding of IHD

When asked about their understanding of heart-related ailments, many participants initially identified a ‘heart attack’ as their primary association with the disease. The participants viewed chest pain and heart attack as the same concept.

For most participants, their perceptions were shaped by personal experiences involving family members or close acquaintances who had heart attacks, undergone cardiac surgery, or had coronary artery interventions.

‘I think obvious one is stroke and heart attack I know because our father had arteries blocked and he needed stents, in general I think this is the only heart disease that I know about’. Participant 8 (male)

Several participants indicated that heart disease was perceived as a prevalent health concern, describing it colloquially as a ‘normal disease’. Notably, some participants also challenged the conventional notion that heart disease primarily afflicts the elderly. Instead, they acknowledged its potential to affect individuals across all age groups.

Participants expressed diverse viewpoints on the prognosis of heart disease, ranging from seeing it as curable to believing it is only preventable. Many narratives were drawn from family experiences, which shaped the understanding of prevention and treatment strategies for study participants.

‘if they are detected on time you can live with them too like my grandfather had three heart attacks and then he lived up to 90 and he managed it well’. Participant 11 (male)

ii) The risk of developing IHD due to genetics and aging

Most participants viewed genetics as the primary determinant, regardless of lifestyle choices. Participants also drew from personal experiences and anecdotes within their social circles to validate their beliefs regarding the hereditary nature of heart disease. The cultural context also shaped perceptions, with one participant shedding light on the prevalence of consanguineous marriages in their state. They believed that such unions led to a concentration of genetic factors, amplifying the risk of heart disease within families.

‘In our family heart diseases are quite prominent and we are quite susceptible to it too I believe….’ Participant 9 (female)

Opinions about old age as a risk factor were quite diverse. While some participants acknowledged their limited understanding of heart disease risk factors and leaned towards the notion of heart disease being primarily associated with advanced age, others challenged this conventional belief, recognizing the potential impact on younger individuals.

‘I don’t really know much; I only know that it’s an age factor perhaps people say it happens to people in the old age but these days it’s also happening to younger people. But I don’t really know any other cause.’ Participant 15 (female)

iii) The risk of IHD due to lifestyle factors

Participants emphasized that lifestyle choices play a major role in shaping both heart health and overall health, regardless of age. They also highlighted that the food habits were more suitable to the lifestyle of the past where people worked on farms. They further shared that the cultural expectation to look a certain way also leads to unhealthy eating habits.

‘Our food habits, generally I think our food habits were very good when we worked in the farms. But now our professions have changed … but we didn’t change our food habits…. The other thing in our community is that you should look like that you come from home where there is a lot of food.’ Participant 5 (female)

Further, some participants felt strongly that eating healthy foods and leading active lifestyle reduced their IHD risk completely. Conversely, one participant reflected on their risk of IHD given their lifestyle behaviours after witnessing others’ experiences with the disease. However, they confessed to subsequently forgetting about it. Many acknowledged lack of exercise as a major issue, discussing their own inactivity.

Participants highlighted using smartwatches to track fitness and support exercise routines as a motivator. Some found fitness knowledge encouraged participation in appropriate activities. However, one participant criticized over-reliance on technology, advocating for a holistic health approach beyond digital tracking.

‘Some people rely on technology too much…. They have made it a box and they don’t think outside of this box’. Participant 4 (female)

Further, a stressful lifestyle was also reported as a contributing factor to the development of heart disease. While some participants shared coping mechanisms, they acknowledged the challenges of managing stress and recognized that some level of stress is inevitable.

On the contrary, some participants shared they did not know what role lifestyle behaviours play in developing heart disease.

Perceptions of own risk of IHD

Participants were asked if they believed they were at risk of heart disease, to assess their personal risk and to compare it with that of their peers. The responses were classified into two sub-themes: Perceived risk related to modifiable and non-modifiable factors; and Perceived relative risk of IHD.

i) Perceived risk related to modifiable and non-modifiable factors

Participants widely acknowledged genetic predisposition as a key factor in heart disease risk. Many shared family histories of heart issues spanning generations, often feeling a sense of inevitability or helplessness. However, those with a lineage of good health and longevity largely perceived themselves at lower risk due to the absence of heart disease among relatives.

‘If I look at my family history then I shouldn’t be at risk because I have a strong family history, I mean everyone lived a really good and long life’. Participant 1 (female)

Other participants acknowledged the challenges of maintaining a healthy diet within the confines of their lifestyle, often opting for convenience over health. Factors such as insufficient exercise and reliance on fast food emerged as key concerns. Participant also identified stress as a significant cause of heart disease. One participant also pointed out that sleep is often overlooked compared to diet, lifestyle, and physical activity.

On the other hand, some participants felt protected from heart disease due to healthy habits like regular exercise and mindful eating. They cited lifestyle changes as proof of their commitment. One participant’s perspective veered towards faith as a higher power, viewing health outcomes as ultimately governed by forces beyond human control.

‘Not really, I mean because I don’t think I’ll ever have a heart attack like I told you before that I eat healthy’. Participant 15 (female)

Meanwhile, some participants expressed that their proactive measures, such as dietary adjustments and exercise, reduced their risk, yet remained cognizant of the unpredictability of future health outcomes.

ii) Perceived Comparative Risk of IHD

Participants were asked to predict their risk of developing heart disease in the next decade compared to their peers. Many (who initially believed they were at risk) experienced a shift by comparing their risk with their peers where they often viewed themselves as being at lower or similar risk. The shift in perception was influenced by several factors including lifestyle choices. Other participants pointed out the absence of family history or comorbidities as factors that lowered their risk.

Participants shared beliefs about their risk factors and acknowledged that their actions can have an impact on their heart health. Two of participants showed concerns about their unhealthy lifestyle and perceived their relative risk higher than their peers.

‘I think I am at risk because I am a little obese…my BMI is higher so I think I might be at risk… I think overall my risk will be same as my peers. … some are really into health and fitness …. So, they are extreme … but if I compare myself with other people, I believe my risk is lower than them because I go for walks and try to eat healthy’. Participant 16 (female)

In contrast, some participants expressed confidence in their ability to prevent developing heart disease through healthy lifestyle choices. Other participants believed that their genetic makeup conferred them with a lower susceptibility to heart disease. However, some participants believed that a healthy lifestyle played a greater role in reducing their IHD risk, despite a strong genetic predisposition to the condition.

Some participants held the belief that regardless of individual circumstances, everyone faces a uniform risk of heart disease. They acknowledged their own genetic predisposition, recognizing it might slightly elevate their risk compared to others. However, they emphasized that stress, a known contributor to heart disease, affects everyone, albeit in different forms and intensities. This led them to conclude that, fundamentally, everyone shares an equal level of risk.

‘So far I think my risk is less than others as I think genetically, I am lucky and my body weight is not that much and my body fat is not high, that’s why I think I am at a lower risk.’ Participant 19 (male)

Meanwhile, some participants found it challenging to gauge their comparative risk of developing IHD. They cited various factors, such as lifestyle choices, genetics, and family history, that influence one’s risk. However, they admitted uncertainty about accurately predicting others’ risk, as they lacked comprehensive knowledge of their peers’ backgrounds and health histories. Participants also acknowledged the complexity of the human body, expressing uncertainty about understanding its workings fully.

Perceived barriers to IHD prevention

The participants identified several factors as influencing their ability to make healthy lifestyle choices. These responses were combined into three sub-themes: Individual and environmental factors; Socio-cultural factors and Insufficient guidance from healthcare providers.

i) Individual and environmental factors

The obstacles ranged from external factors such as cold weather through to time constraints thereby hindering their ability to prioritize a healthy lifestyle. Many participants shared that their ability to exercise depended on the weather conditions in Melbourne Some participants further linked the colder weather to their unhealthy eating habits.

Participants expressed that being immigrants added extra stress to their lives, resulting in psychological strain and limiting the time available to engage in healthy activities like exercise. Time constraints were also discussed in other contexts, such as managing a young family or working full-time hours. The participants also added that the full-time job and COVID lockdown factors hindered their exercise practises. However, for Participant 10 heart disease cannot be prevented.

‘Our life has become so busy and stressful here… I am not sure if it is because of competition with others or merely for survival’. Participant 5 (female)

ii) Socio-cultural factors

As first-generation migrants, participants acknowledged that their focus often lies elsewhere, with pressing priorities overshadowing considerations of well-being. Participants voiced the struggles of their journey such as navigating visa issues and experiencing limited social support due to the absence of extended family. They shared that the stress of being a first-generation immigrant acts as a contributing factor in not maintaining healthy habits.

‘I used to stress a lot about PR, it affected me a lot…. it affected my sleep’ Participant 4 (female).

The overall culture of not participating in exercise was discussed. Participants believed that the only type of exercise Indian people engage in is walking and even that is not a priority. However, they further shared that younger migrants may be more interested in fitness because of their awareness. On the contrary, some participants observed that the younger generation migrating from India these days is driven by the pursuit of financial stability and may not prioritize their health as much.

Participants highlighted a cultural mindset that prioritizes food-related social activities over physically active pursuits. This tendency leads to limited exposure to alternative recreational practises such as group- based physical activities. Further, a focus on financial security for future generations was identified as a contributing factor, with Indian migrants often prioritizing work and savings over personal wellbeing and investment in their own health. One noted that some Indian migrants’ lack of practical skills reflects this perspective. This sentiment resonated with others, who noted a striking difference between their leisure activities and those of their white colleagues.

‘We don’t know how to do anything “extra”… when we come to another country, we don’t know anything DIY, in India we call someone to even change our tube lights but when you do things yourselves it gives you a kind of booster and helps in relieving stress and anxiety too’. Participant 16 (female)

iii) Insufficient guidance from health care providers

A prevalent challenge identified by participants was the practicality of implementing healthier behaviours within their cultural and personal contexts. They expressed frustration that the healthy food options advocated by healthcare professionals often clashed with their cultural dietary preferences and traditional food preparation methods. Consequently, participants perceived this incongruence as a significant barrier to behaviour change. Participants added that practical recommendations for healthier behaviours, when integrated into existing lifestyles may be more effective in promoting behaviour change.

Participants stressed that multilingual health information enhances literacy and access to healthcare services for individuals and their families. They highlighted the misconception that all individuals from India speak Hindi, when in fact there are many different languages spoken throughout the country. Participants They noted the absence of health promotion materials in their languages, except during COVID.

‘They think if someone is from India they should know Hindi, but that is not true…each state has its own language…’ Participant 2 (female)

Most participants had never discussed IHD risk or prevention with healthcare providers. Only two reported having heart- disease-related conversations, which occurred after they experienced symptoms that were later determined to be non-cardiac in origin. Gaps in healthcare screening were also pointed out by the participants. Participants expressed dissatisfaction with healthcare providers’ approach to heart disease screening, perceiving a lack of proactive efforts, particularly among those at high risk. Healthcare providers often priortizeaddressing patient’s immediate concerns over the prevention of broader health risks.

‘They know I have a strong family history… they did all the tests when I had a caesarean but never screened for heart disease…. They focus on only one issue that you present with for example fever… they don’t offer you anything extra’ Participant 9 (female)

Participants felt heart disease prevention lacks focus compared to other conditions. While they received reminders for pap smears and gestational diabetes screenings, no similar system exists for heart disease.

Motivators to modify IHD risks

The study participants shared the factors that motivated them to adopt healthier lifestyle choices. These motivators included peer support, a sense of responsibility toward their families and experiences of false alarms related to IHD. Several sub-themes emerged from the interview data regarding motivating factors for behaviour change. These are categorized into two main sub-themes: (1) family and friends’ support and (2) illness beliefs and experiences.

i) Family and friends’ support

Social support served as a motivating factor. Participants shared that they were more likely to engage in physical exercise when they were part of a group. They recognized the interconnectedness of their own health with the health of their loved ones. The sense of responsibility towards their family was a strong motivating factor for the participants to prioritize their own health and well-being. The participants shared that their health status can have an emotional impact on their family and cause them to worry or feel sad.

‘Plus, what I feel with the family you know, because if I am unhealthy, it will affect my family, especially when your parents are there in India, not my father he has passed away, but mum is still there it will bring a lot of sadness to them’. Participant 13 (male)

For other participants, financial considerations and retirement benefits served as motivating factors to maintain good health to continue working and earning a living. Further, the desire to live longer and healthier lives was also used as a motivating factor among the participants. ‘People retire early in India but here the retirement is 65… when I saw people working at that age….I wanted to be like them too…’. Participant 16 (female)

Further, one of the participants was motivated by their religious philosophy, which emphasizes living within limits, including controlling food intake and stress levels. They reflected on the influence of Sikhism on their perspective on health and well-being. Although only one participant made this comment, it highlights an important aspect of the cultural influence on lifestyle behaviours.

ii) Illness beliefs and lived experiences

The study participants reported changes in their lifestyles and identified the factors that motivated them to make these changes. Some participants cited a false alarm as a catalyst for their lifestyle changes, while others mentioned losing a close friend as a motivating factor.

‘I had a friend who was only two years older than me… he was a bit overweight as he used to eat a lot of junk food… he had a heart attack and passed away… that incident kicked all of us very hard… I became a lot more conscious of my health… for example I didn’t have any sugar for nine months… no alcohol from last 12 months’. Participant 17 (male)

One participant re-evaluated their lifestyle after experiencing left arm pain, though it was linked to physical exertion. Another was driven to change by their daughter’s type 1 diabetes diagnosis and their participation in community events. Managing the condition fostered family health awareness. Simultaneously, their involvement in community activities, such as volunteering with the State Emergency Services and participating in running groups, provided a supportive network and a platform for physical activity.

A summary table containing themes, sub-themes and representative quotes is provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Themes and sub-themes with exemplar quotes

Discussion

The study findings are discussed within the framework of the COM-B model of behaviour change. This model comprises three key domains that influence behaviour: Capability (both physical and psychological), Opportunity (external factors that facilitate or impede the occurrence of behaviour), and Motivation (the cognitive processes that initiate and direct behavioural actions) (Michie et al., Reference Michie, Van Stralen and West2011). This model acknowledges that behaviour is subject to multiple influences and emphasizes that modifications in at least one of these components can lead to behaviour change. The COM-B model is particularly crucial in the context of intervention strategies, as those facilitating change must ensure the enduring nature of newly acquired behaviours. It has predominantly found application in the field of public health (Willmott et al., Reference Willmott, Pang and Rundle-Thiele2021). By aligning the study findings with this model, it becomes possible to identify avenues for effectively supporting Indian migrants in adopting healthier behaviours related to IHD prevention.

Capability

In terms of the psychological capability, participants focused more on non-modifiable factors, particularly family history, reinforcing a sense of inevitability about IHD aligning with Topçu and Ardahan (Reference Topçu and Ardahan2023), who found higher risk perception among individuals with familial histories of heart disease. Grauman et al. (Reference Grauman, Viberg Johansson, Falahee and Veldwijk2022) Some participants in our study highlighted the impact of stress and anxiety on their risk and attempted to address these factors. While stress and anxiety contribute to the risk of IHD and managing these factors is crucial for overall health. However, the participants’ focus only on non-behavioural risk factors is worrisome, as it may lead to an underestimation of their actual risk based on these factors, potentially hindering them from taking preventive measures. This emphasis on non-behavioural causes may result from gaps in knowledge about IHD risk factors or a denial of being at risk. Previous research in this domain has similarly noted that stress and anxiety are perceived as significant contributors to the development of heart disease, particularly among women (Al-Smadi et al., Reference Al-Smadi, Ashour, Hweidi, Gharaibeh and Fitzsimons2016; Grauman et al., Reference Grauman, Viberg Johansson, Falahee and Veldwijk2022). These insights highlight the need for prevention strategies that educate Indian migrants on risk factors and empower them to adopt long-term health promoting behaviours.

Opportunity

Most participants viewed their IHD risk as equal to or lower than their peers, even when acknowledging higher personal risk. This tendency to underestimate IHD risk is well-documented among high-risk individuals (Sali and Haribhakt, Reference Sali and Haribhakt2019). Such underestimation can affect treatment choices, with those perceiving themselves as low risk likely neglecting to seek treatment or adhere to long-term lifestyle changes after a heart disease diagnosis (Navar et al., Reference Navar, Wang, Li, Mi, Li, Robinson, Virani and Peterson2021).

High-risk individuals, including those with family history, reported never being screened or discussing risk factors. Participants also noted neglect in secondary prevention for family members, despite Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) and Heart Foundation guidelines recommending screening based on individual risk. (The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, 2023, Heart Foundation, 2023). Recent data aligns with these findings, indicating that only 50% of the population aged between 45 and 74 undergo screening for IHD risk factors and the screening process for high-risk individuals is inconsistent (Paige et al., Reference Paige, Raffoul, Lonsdale and Banks2023). This is a noteworthy finding, as the progression of IHD is not an abrupt occurrence; it is a continuous process that begins years before the actual diagnosis. Hence, these findings serve as a significant practise point for all healthcare professionals; every healthcare encounter should be leveraged as an opportunity for health promotion activities.

Migration is a key barrier to behaviour change, with first-generation migrants prioritizing other concerns such as visa status and settlement in a new country over health-related behaviours The process of migration introduces substantial challenges to health, altering daily life and requiring tailored health promotion initiatives. Rustage et al. (Reference Rustage, Crawshaw, Majeed-Hajaj, Deal, Nellums, Ciftci, Fuller, Goldsmith, Friedland and Hargreaves2021) reported that health promotion interventions often lack meaningful involvement from migrants. The inclusion of migrants in all stages of developing a health promotion strategy may enhance migrant participation. Castañeda et al. (Reference Castañeda, Holmes, Madrigal, Young, Beyeler and Quesada2015) argue that for meaningful improvements in health outcomes to occur, it is essential to view immigration as a determinant of health. The status of being an immigrant not only constrains behavioural options but also often directly affects and modifies the consequences of other social factors like race/ethnicity, gender, or socioeconomic status. This is primarily because immigrants find themselves in uncertain and sometimes complex relationships with the state and its institutions, including healthcare services. Thus, the recommendations from the international literature must be followed while developing health promotion activities for migrant populations (World Health Organization, 2018). Understanding these factors is crucial for nurses in primary healthcare settings, as it guides culturally competent care planning, facilitates effective communication, fosters trust-building, and supports advocacy for migrant health (Bempong et al., Reference Bempong, Sheath, Seybold, Flahault, Depoux and Saso2019).

The overarching cultural influence, which places a strong emphasis on food and maintaining a certain financial image acts as an obstacle to behaviour change. Studies by Gupta et al. (Reference Gupta, Aroni and Teede2016) and Fernandes et al. (Reference Fernandes, Caperchione, Thornton and Timperio2021) confirm cultural perspectives shape physical activity uptake among Indian and Southeast Asian migrants in Australia. However, attributing unhealthy lifestyles solely to culture oversimplifies the issue, as social, economic, and environmental factors also play a role. This perspective was reinforced by some participants who believed that their unhealthy lifestyle was a result of life struggles and environmental factors in general. Similar trends have been reported in the literature previously for example Gupta et al. (Reference Gupta, Aroni and Teede2016) reported that Indian migrants labelled their own racial groups as lazy and believed that free time is for family rather than for exercise or other lifestyle activities. In this context, nurses can play a pivotal role in delivering health literacy that is tailored to an individual’s personal beliefs. This approach fosters better understanding and adherence to preventive measures (Oster et al., Reference Oster, Wiking, Nilsson and Olsson2024).

It is important to recognize the diversity within Indian culture, as subcultures vary widely. The cultural context for someone from the north of India, for example, may differ significantly from that of someone from the south of India (Ganpule et al., Reference Ganpule, Dubey, Pandey, Green, Brown, Srinivasapura Venkateshmurthy, Jarhyan, Maddury, Khatkar, Prabhakaran and Mohan2023). For instance, the dietary habits described were mainly from Punjabi participants (northern India), whose cuisine is typically high in fat and dairy. In contrast, South Indian diets are generally lower in saturated fats and higher in carbohydrates, often featuring rice-based dishes and lentil preparations (Kumbla et al., Reference Kumbla, Dharmalingam, Dalvi, Ray, Shah, Gupta, Sadhanandham, Ajmani, Nag, Murthy, Murugan, Trailokya and Fegade2016).

Participants highlighted the need for health information that aligns with their cultural and linguistic backgrounds and is applicable to healthier living. Similar gaps have been noted in refugee health in Australia (Peprah et al., Reference Peprah, Lloyd and Harris2023). Culturally responsive health promotion activities have been proven to be more effective in international indigenous populations (Look et al., Reference Look, Maskarinec, De Silva, Werner, Mabellos, Palakiko, Haumea, Gonsalves, Seabury, Vegas, Solatorio and Kaholokula2023). Further, it was learned During COVID-19, simply translating information wasn’t enough; engaging community leaders and media was key to behaviour change (Wild et al., Reference Wild, Kunstler, Goodwin, Onyala, Zhang, Kufi, Salim, Musse, Mohideen, Asthana, Al-Khafaji, Geronimo, Coase, Chew, Micallef and Skouteris2021). Identifying such barriers to behaviour change is key for targeted health promotion. Further, participants felt heart disease prevention is overlooked in migrant populations. Migrants’ perceptions of being a lower health priority have been documented in the literature, where they expressed that their health needs were considered secondary to broader policy goals (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023, Peprah et al., Reference Peprah, Lloyd and Harris2023). Further, other research shows migrants can have complex views of the healthcare system. (White et al., Reference White, Levin and Rispel2020). While the principle of equal healthcare for all exists in theory, disparities in access to healthcare persist among migrant populations globally (Jong, Reference Jong2018, World Health Organization, 2022). This is a global challenge, and worldwide efforts are needed to develop healthcare systems that cater to everyone, including migrants.

Motivation

Religious philosophy, particularly Sikhism’s emphasis on physical and mental health, motivated some participants to prioritize their well-being. While no comparable studies on lifestyle were found, spirituality has been linked to psychological well-being (Bożek et al., Reference Bożek, Nowak and Blukacz2020). Healthier lifestyles were also triggered by health scares, false alarms, a family member’s heart disease diagnosis, or the loss of someone to heart disease. These factors have also been identified in previous literature (Baber et al., Reference Baber, Cooke, Kusev, Martin and Nouri-Aria2017). These findings hold significant importance for healthcare professionals working in primary healthcare settings. Approaching care in a culturally sensitive manner is essential, as it can enhance patient trust and improve communication (Saadi et al., Reference Saadi, Platt, Danaher and Zhen-Duan2024).

The study also highlighted that illness perception was influenced by life experiences, particularly observing heart disease in others, consistent with findings of Grauman et al. (Reference Grauman, Viberg Johansson, Falahee and Veldwijk2022) study. Research indicates that individuals who feel little control over risk factors are less likely to engage in preventive health measures (Grauman et al., Reference Grauman, Viberg Johansson, Falahee and Veldwijk2022)

This study’s findings are crucial for policy development, highlighting the need to consider knowledge of risk factors, personal risk perceptions, and behaviour change barriers and motivators in primary and secondary prevention policies for this population. While general guidelines exist, specific guidelines for IHD prevention in ethnic groups are lacking (Reynolds and Childers, Reference Reynolds and Childers2019). The findings from this study lay a solid foundation for incorporating the perspectives of this population into IHD prevention strategies. Further, integrating these findings into prevention strategies for migrant populations supports the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, specifically those promoting good health and well-being and reduced inequalities (United Nations, 2024).

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study was its community-cantered approach, including the use of a CAB and Indian languages in data collection and analysis, which allowed broader participation and preserved cultural context. While participants were diverse, covering regions from North, South, and West of India, it is acknowledged that not all Indian states were represented.

The researcher’s insider status as a first-generation migrant fostered trust but also introduced potential bias. The researcher used various strategies to overcome the bias as described above in the methods section. Selection bias is another limitation, as participants with strong opinions may have been more motivated to join, and self-reporting bias could have affected their perceptions. Due to linguistic constraints within the research team, several major language groups among Indian migrants in Australia were excluded from this study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the study highlights the need for culturally tailored and accessible health education programmes to promote heart health and prevent heart disease within the Indian Australian community. The research highlights the complex interplay between migration, cultural adaptation, and structural inequities in shaping health outcomes. These findings potentially apply to Australian Indians nationwide, given similar demographics across states and diverse participant backgrounds. Although the study primarily examines the experiences of Indian migrants, its findings offer insights that may be applicable to other racial and ethnic minority populations. However, further research is recommended to strengthen these insights.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423626100930

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, KK, upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

All listed authors meet the authorship criteria and contribute as below:

KK - Conceptualization, data collection, data analysis and writing original draught,

MAQ – Supervision, writing – review and editing,

AR – Supervision, writing – review and editing,

NM – Supervision, writing – review and editing,

RS – Supervision, writing – review and editing,

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

Ethics approval was obtained from Edith Cowan University’s human research ethics committee (REMS NO: 2021-02449-KAUR).

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publish

A consent to publish was received from all study participants.