1. Introduction

1.1. Cases of Non-material Environmental Harm

In 1947, Esso and Shell established the company Nederlandse Aardolie Maatschappij (NAM) to conduct gas extraction activities in Groningen (The Netherlands).Footnote 1 These activities have accrued tremendous wealth over the years for the NAM, as well as for the Dutch state.Footnote 2 In 1986, however, the gas drilling caused its first earthquake, after which further earthquakes increased in both number and intensity. Aside from the countless instances of property damage resulting from the earthquakes, many neighbouring inhabitants lost a sense of security and comfort tied to their home. They now live in an area where an earthquake could strike at any time, anywhere. Even after the company ceased its activities in April 2024,Footnote 3 the risk of earthquakes will persist throughout the foreseeable decades and only slowly diminish over the years.Footnote 4 The Dutch courts recognized both the inhabitants’ property damage as well as their non-material suffering as compensable harm.Footnote 5

In 1971, 3M opened a factory in Zwijndrecht, a residential municipality in Antwerp (Belgium).Footnote 6 The factory contributed to the Belgian and local economy, but its activities had detrimental side effects. In 2021, during works on a large-scale road infrastructure project around Antwerp, it came to light that 3M’s emissions had heavily polluted Zwijndrecht. Extensive research revealed that levels of the toxic ‘forever chemical’ perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) in blood samples of inhabitants neighbouring the factory exceeded the health norms imposed by the European Union (EU) in 90% of cases, and even exceeded additional alarm norms in 59% of cases.Footnote 7 A judgment by the Vrederechter (Justice of the Peace) in Antwerp – a Belgian court competent to adjudicate legal disputes about neighbouring properties – awarded €2,000 compensation, which included compensation for the non-material harm suffered by the plaintiff.Footnote 8 The court ruled that the relationship between the inhabitants of Zwijndrecht and their homes has substantially changed, as they now have to abide by ‘no-regret measures’ to ensure their own good health.Footnote 9 Those measures include paying attention to food produced in their own backyard, such as eggs and vegetables, and avoiding contact with the soil in dry weather.Footnote 10

1.2. Problem Statement

In both examples, the Dutch and Belgian courts have recognized that environmental degradation can result in serious non-material harm. However, when examining this type of harm more closely, difficult questions arise concerning its nature and its valuation in court proceedings. Firstly, the absence of a fundamental understanding of the type of harm in question paints a picture of non-material harm as a vague, highly subjective and unintelligible form of harm in legal literature.Footnote 11 Should every form of worry, sadness or dismay in the face of various ecological crises elicit extracontractual liability? It is clear that a certain delineation is needed. Such a delineation should be informed by a profound insight into the psychological reality of the harm. Secondly, this non-material harm consists of non-economic loss, that is a loss of value that does not represent a market value. Yet, extracontractual liability law has a tendency to award monetary remedies for harm suffered. Awarding financial compensation for non-material harm is always a symbolic task. The monetary sum is aimed at recognizing the harm suffered without presuming that it is possible to offer full reparation.Footnote 12 However, the symbolic nature of the task does not mean that the process should be totally arbitrary;Footnote 13 the compensation should still increase in cases where the harm is more serious.

An interdisciplinary approach to environmental non-material harm is needed to address these questions. The existing legal frameworks available to recognize non-material harm in general should be used as a starting point. Psychological research can further supplement, inform, and perhaps even lay a basis for critique. Combining the two will bring about an interdisciplinary approach to recognizing, assessing, and measuring environmental non-material harm. Conveniently, the field of environmental psychology is rife with research on how the environment has an impact on our mental health. More specifically, in this article I focus on a relatively new concept, namely solastalgia, often defined as the lived experience of negatively perceived changes to a familiar environment (Section 3.2). The current solastalgia literature can provide a solid conceptual basis for understanding environmental non-material harm and provide empirical insights. Solastalgia describes a specific form of harm with a certain level of seriousness that occurs in situations of actual environmental loss. Additionally, empirical research on solastalgia reveals certain insights that can assist judges in quantifying the amount of compensation. The research question that guides this article is to ask in which ways can psychological research on solastalgia help Belgian and Dutch extracontractual liability law in understanding and assessing non-material harm in environmental cases. A scoping review was used to survey the literature on solastalgia.Footnote 14 In total, I included 150 articles, 83 of which included empirical findingsFootnote 15 on solastalgia; the remaining 67 were included because of their theoretical relevance.

1.3. Structure

To answer the research question, I start by summarizing briefly the state of the art in law and legal literature and briefly elaborate on the method used to conduct the interdisciplinary analysis (Section 2). Secondly, I present the results gathered from studying the solastalgia literature (Section 3). I then discuss the interaction between solastalgia in psychological research and non-material environmental harm in legal research (Section 4). I conclude (in Section 5) that solastalgia constitutes a valid and highly relevant type of harm for modern environmental liability law, and I suggest further pathways for embedding the notion in other fields of law.

2. Belgian and Dutch Law: The Legal Perspective

2.1. The Choice for Belgian and Dutch Law

To understand whether tort law is receptive to solastalgia, I must first introduce the Belgian and Dutch tort law frameworks, focusing on their conception of (non-material) harm. I chose these legal systems because of their fundamentally different starting points. While the Belgian legal system is open to all forms of harm,Footnote 16 Dutch tort law uses a closed system for non-material harm.Footnote 17 In practice, however, both tort law systems have produced environmental case law in which compensation is awarded for non-material harm. Therefore, the Belgian and the Dutch tort law systems, in principle, are a good starting point for studying solastalgia. Further research investigating solastalgia in other (common law) legal systems would greatly benefit the current state of the art.

2.2. Belgian Law

Belgian law uses an open system for recognizing (non-material) harm, but uses criteria to limit it. Harm should be lawful,Footnote 18 certain,Footnote 19 and – most importantly in cases of environmental liability – harm should be personal.Footnote 20 The latter requirement principally rules out the compensation of collective forms of harm. Plaintiffs cannot receive compensation for losses suffered by humanity as a whole, such as deforestation in the Amazon or the rapid loss of permafrost worldwide. Plaintiffs need to prove that they are affected by environmental degradation in a personal manner. This means that the plaintiff should be affected in a specific way, a way that can be distinguished from the ways in which the many, or everyone in society are affected.Footnote 21 To that end, case law and legal doctrine in Belgium require a close connection between the environmental elements and the plaintiff.Footnote 22 Plaintiffs cannot claim personal harm for just any form of harm resulting from environmental degradation, but must prove that they have close ties to the environmental elements that have been degraded. Such a connection is assumed in cases where the plaintiff is the owner of the environmental elements in question.Footnote 23 Forms of economic dependence on nature, such as hunting or fishing, can also create a personal connection.Footnote 24 Moreover, Belgian courts accept a close connection based on emotional ties to a certain place,Footnote 25 such as ties to one’s home environmentFootnote 26 or recreational environments.Footnote 27

2.3. Dutch Law

Dutch tort law is traditionally more hesitant in recognizing non-material harm. The closed system of the Dutch Civil Code lists exhaustively categories of non-material harm that are compensable in Dutch tort law. For the purposes of this article, I focus on Article 6:106, more specifically section (b), which contains the residual category of ‘deterioration of a person in some other way’. The case law of the Hoge Raad (Dutch Supreme Court), the highest civil court in the Netherlands, shows that this category can be applied in two types of case. The first type requires proof of a psychological injury, which implies emotional harm that exceeds a certain minimum threshold of seriousness.Footnote 28 For some time, this psychological injury was required to be substantiated by medical proof that the plaintiff was suffering from a psychiatric illness.Footnote 29 However, the Hoge Raad abandoned this clinical approach in 2021. The Court now requires only that the harm should be proven with objective standards and emphasizes that mere feelings of unpleasantness do not suffice.Footnote 30

In the second type of case, the Hoge Raad recognizes an alternative legal basis for the requirement of a psychological injury if it is justified by the nature, gravity, and consequences of the wrongdoing in question.Footnote 31 The claimant is still required to substantiate the deterioration of their person with concrete evidence, although the bar of proof is lower than proof of a psychological injury.Footnote 32 As an exception to this principle, deterioration of the person can be presumed if the wrongdoing is so serious that negative consequences are obvious.Footnote 33 This new route towards compensation for non-material harm, often referred to as the EBI-route, was well received by the literature and praised for introducing flexibility while still remaining faithful to the requirement of harm.Footnote 34 In the Dutch earthquake case, the Hoge Raad confirmed that non-material harm can be presumed on the basis of the seriousness of the wrongdoing as well as its consequences. The Hoge Raad stated, as a general rule of thumb, that non-material harm can be inferred from the fact that the claimant suffered physical damage to their house on two occasions.Footnote 35

3. Solastalgia: The Psychological Perspective

3.1. Delineation of the Interdisciplinary Research

Solastalgia is only one of many concepts used in environmental psychology to describe negative impacts of environmental change on our mental health. Before delving into solastalgia, I would like to introduce the reader to a small selection of these notions. Doing so allows me, firstly, to further clarify and substantiate my choice of solastalgia as an object of study and, secondly, to introduce the reader to two notions that bear some significance throughout the following analysis: eco-anxiety and ecological grief.

Firstly, ‘eco-anxiety’ describes a non-specific anxiety relating to a changing and uncertain environmentFootnote 36 and the sheer scale, complexity, and ‘wickedness’ of the environmental problems we are facing.Footnote 37 This anxiety pertains to all types of general ecological crisis, including climate change, biodiversity loss, and mass pollution.Footnote 38 In that sense, it is a collective form of anxiety, widely and globally shared.Footnote 39 Although it certainly merits attention by researchers and policymakers, it is doubtful that all forms of eco-anxiety constitute a compensable harm under current tort law regimes. In Belgium, arguably, eco-anxiety fails to qualify as a personal form of harm, because it does not imply a close connection with a specific environment. In other words, eco-anxiety is best understood as a collective form of harm, as it describes how we suffer collectively from global environmental problems, such as climate change. In the Netherlands, it is uncertain whether eco-anxiety could consistently exceed the required level of seriousness, even within the EBI-route. The fact that eco-anxiety is so widely shared throughout our contemporary society indicates that it has become a normalized feeling, part of our daily lives. Only in exceptional cases, where eco-anxiety has led to severe and demonstrable suffering, could judges consider compensation.

Secondly, the psychological literature studies ‘ecological grief’, which serves as a general term ‘for sadness, feelings of loss and processes of grief in relation to the ecological crisis. People may grieve both particular losses and the general, global ecological damage’.Footnote 40 Cunsolo and Ellis discern three types of ecological grief.

Firstly, this grief can be associated with the loss of environmental knowledge.Footnote 41 For example, climate change drastically changes weather patterns. As a result, many lose a form of traditional or scientific knowledge of how to predict weather, a loss that can lead to grief. Similarly, the loss of biodiversity comes with a loss of knowledge about certain species.Footnote 42 Indeed, biologists and other environmental scientists are likely to grieve over the loss of the object of their studies.Footnote 43 For the purposes of this article, however, this form of harm is too specific and still too understudied to meaningfully inform the broader legal debate at present.

Secondly, ecological grief can be associated with anticipated future losses. Indeed, as also recognized in court cases, the looming threat of serious environmental change can already cause some form of present non-material harm.Footnote 44 However, a separate study is required to uncover this particular form of harm.

Thirdly, ecological grief can be associated with concrete physical ecological loss in a direct environment.Footnote 45 This third type of ecological grief bears significant resemblance to solastalgia, considered below, so much so that many researchers regard this subcategory of ecological grief as synonymous with solastalgia.Footnote 46 While ecological grief would undoubtedly provide a more comprehensive account of different types of non-material harm related to the environment, the focus on solastalgia, the third subcategory, is justified by a need to delineate the research. Unlike the other forms of ecological grief, solastalgia is sustained by a wide body of psychological literature. In what follows, it will become clear that solastalgia describes a specific and serious form of environmental harm, capable of qualifying as compensable harm under Belgian and Dutch tort law.

3.2. A Brief History of Solastalgia

Solastalgia was first introduced in May 2003 at the Ecohealth Conference in Montreal (Canada), by Glenn Albrecht.Footnote 47 He first published his ideas on solastalgia in 2005 in the journal Philosophy, Activism and Nature.Footnote 48 Albrecht derived the neologism ‘solastalgia’ from nostalgia, formerly considered a medically diagnosable illness that describes homesickness or the distress caused by a burning desire to go home.Footnote 49 Nostalgia often occurred in Indigenous communities who were dispossessed of their native lands,Footnote 50 or among soldiers fighting a war in a foreign territory.Footnote 51

During fieldwork in the Upper Hunter Region (Australia), a landscape rapidly transformed by expanding open-pit mining activities, Albrecht and his colleagues discovered a similar condition.Footnote 52 The inhabitants he interviewed had complaints similar to those associated with nostalgia. In this case, however, the inhabitants had not left their home environment. Instead, their home environment itself was changing into a grim and inhospitable landscape right before their eyes.Footnote 53 It was as if they experienced a ‘homesickness without leaving home’.Footnote 54 Based on these findings, Albrecht coined the term ‘solastalgia’, derived from two words in classical Greek and Latin. On the one hand, ‘solari’ and ‘solacium’ refer to the comfort and familiarity associated with being home.Footnote 55 In English, the word ‘solace’ (‘soelaas’ in Dutch) still refers to a feeling of deep comfort. ‘Algos’ refers to pain and suffering. Thus, Albrecht describes solastalgia as the ‘lived experience of negatively perceived changes to one’s home environment’.Footnote 56

With this concept of solastalgia, Albrecht identified a form of loss that was not yet captured by any word in the English language and often overlooked in Western culture.Footnote 57 It gained traction in the media and in some psychological scholarship.Footnote 58 In 2019, the literature on solastalgia had grown sufficiently to warrant an extensive literature review. Galway and co-authors identify nearly 50 studies on the concept of solastalgia.Footnote 59 The literature has increased exponentially since 2019Footnote 60 in the field of psychology as well as in other fields, such as geography, literature studies, migration studies, religious studies, architecture, and law.Footnote 61

3.3. Interpreting Solastalgia

While the proliferation of literature undoubtedly increases the scientific credibility and relevance of solastalgia, it has also led to the attribution of different meanings and conceptualizations, making the notion somewhat harder to understand. The definition given by Albrecht leaves much room for clarification. The main source of this lack of clarity lurks in considering solastalgia as a subjective problem: that is, a problem experienced by the victim in Cartesian isolation. Such an interpretation surfaces in two discussions.

An initial discussion concerns the question of whether solastalgia should be considered as a new psychiatric illness. This question is tied to a broader philosophical debate on what a psychiatric illness is.Footnote 62 More importantly for the purposes of this analysis, Askland and Bunn have posed that qualifying solastalgia as a psychiatric illness overlooks the core of the issue.Footnote 63 Solastalgia should be understood as a deeper ontological phenomenon, a condition of existence.Footnote 64 In other words, the problem of solastalgia does not lie purely within the victims themselves; it does not consist of a bad wiring within the subject’s brain. Solastalgia describes a phenomenological disturbance in the way in which the victim inhabits their home environment.Footnote 65 In later work, Albrecht clarifies that solastalgia was never intended to constitute a medically diagnosable psychiatric illness;Footnote 66 it should instead, as indicated above (Section 3.1), be seen as a form of grief. People can be related to a place in a way that is similar to being related to close friends and relatives.Footnote 67 Grief is a natural state of being after being confronted with loss, and not an illness per se.Footnote 68

A similar misunderstanding can arise when describing solastalgia as an emotion. While most authors agrees that it is an emotion, there is a lack of clarity about what this term ‘emotion’ means. Sometimes, it is portrayed as a highly subjective, human-centred form of pain.Footnote 69 However, Albrecht reminds his readers that emotions – derived from ‘movere’ in Latin, meaning ‘to move’ and ‘emovere’ meaning ‘to agitate or disturb’ – are always defined by ‘that what moves us or affects us’.Footnote 70 Instead of focusing solely on the subjective experience of the victim, emotion in a phenomenological sense consists of the aggregate of the subject’s relation with a certain object, a certain environment in this case. Solastalgia targets the embeddedness of beings in their environment and the existential loss that occurs when that embeddedness is drastically altered.Footnote 71

Indeed, solastalgia is not a mysterious subjective feeling; nor is it a psychiatrically problematic way of reacting to ecological loss. Rather, it describes an understandable state of being in relation to actual loss that springs from the deterioration of a familiar place. That notion, ‘place’, is central to the solastalgia discourse.Footnote 72 In the psychological literature, ‘place’ is understood as a socio-ecological concept, where humans are seen as an integrated part of the environment.Footnote 73 It encompasses more than just the biophysical attributes of a certain location. It encompasses the meanings, values, familiarity, and predictability attached to it.Footnote 74 The most prominent example of such a place in the solastalgia literature is ‘home’.Footnote 75 Humans have a profound connection with their home environment, in the sense that it provides comfort and relief from the struggles and burdens of the world at large and also in the sense that it drastically shapes their everyday life and, by extension, who they are. If that place changes for the worse, our everyday life and our identity changes with it.

3.4. The Different Contexts of Solastalgia Research

Now that I have given a basic understanding of what solastalgia is, I will give a brief overview of the contexts in which solastalgia has already been investigated by the literature. Albrecht distinguishes between two types of solastalgia: (i) that caused by natural causes, and (ii) that relating to artificial causes.Footnote 76 With regard to natural causes, a large portion of the relevant studies pertain to wildfires,Footnote 77 which has also been picked up by the broader literature on wildfires.Footnote 78 A single other study pertains to solastalgia after windstorms.Footnote 79 Both of these sudden natural phenomena can cause a pervasive change in a particular place, which in turn gives rise to solastalgia. However, some natural disasters do not cause a fundamental change in people’s sense of place. For instance, research conducted on volcanic eruptions suggests that some inhabitants of volcanic areas accept the risk of eruption as part of their home and appreciate the benefits that an eruption can yield.Footnote 80

Most solastalgia studies focus on the second type of solastalgia, namely that relating to artificial, man-made changes to our environment. Mining activities, the context in which the term ‘solastalgia’ was coined,Footnote 81 remain an important field of study in later research.Footnote 82 A small-scale qualitative study suggests that solastalgia also can arise when closing a mine, if that mine has become an intrinsic part of the inhabitants’ environment.Footnote 83

Solastalgia can also apply in the context of other invasive means of energy production, such as hydro power,Footnote 84 geothermal power plants,Footnote 85 and petroleum development.Footnote 86 The process of urban development in a broad sense has also been scrutinized in solastalgia research. Changes in rural landscape, agricultural activities, and loss of green spaces can evoke feelings of solastalgia.Footnote 87 Drastic changes resulting from tourism can cause solastalgia in ruralFootnote 88 as well as in urban environments.Footnote 89 Solastalgia can surface in a political context, such as political violence against Palestine,Footnote 90 mass immigration from Syria to Lebanon,Footnote 91 and the forced eviction of Batwa people in Uganda.Footnote 92 Landscapes that lose biodiversity as a result of human activities and pollution,Footnote 93 as well as more invisible changes to the environment (such as the knowledge of present dangerous toxins or menacing smells), can also evoke feelings of solastalgia.Footnote 94

Albrecht predicts that solastalgia will become a more widespread emotion as climate change continues to harm our environment.Footnote 95 A large portion of solastalgia research focuses on climate change,Footnote 96 so much so that solastalgia is now consistently picked up in literature reviews on the mental health effects of climate change in general.Footnote 97 It should be noted, however, that solastalgia research always focuses on specific tangible outcomes of climate change, never on anger or anxiety about the abstract concept of climate change itself.Footnote 98 Solastalgia stems from specific environmental losses, and has less to do with the mental health consequences of climate change in general.Footnote 99 Researchers study climate-vulnerable communities, where climate change is actively degrading soil fertility,Footnote 100 eroding coastlines,Footnote 101 changing the affective bonds between locals and the beauty of their homeFootnote 102 and changing the nature from which Indigenous communities derive their personal and cultural identity.Footnote 103 Vulnerable communities also experience a form of anticipated solastalgia when their bond with the environment negatively changes because of anticipated environmental losses.Footnote 104 Some researchers investigate how solastalgia influences decisions to migrate from climate-vulnerable areas.Footnote 105

3.5. Empirical Research on Solastalgia

In 2019, Galway and co-authors indicated a lack of quantitative empirical research on solastalgia,Footnote 106 and at present there are still too few quantitative studies (30) from which to draw generalizable conclusions. In this subsection, I touch briefly upon the quantitative methodology that is used in most research. I then identify certain characteristics and impact factors that are linked to solastalgia in quantitative research, in combination with qualitative research. The testimony of people confronted with severe environmental destruction found in qualitative research helps to understand solastalgia.

The most commonly used tool to gather data is the Environmental Distress Scale (EDS). This tool was developed and tested by Higginbotham and co-authors in 2007 to provide an index of bio-psychosocial costs of environmental degradation.Footnote 107 It is a survey that assesses six environmental distress components: (i) frequency of hazard events; (ii) observation of hazards; (iii) threat to self and family; (iv) felt impact of environmental change (physical/psychological, social and economic); (v) feelings of solastalgia (sadness, worry, and so on); and (vi) performance of environmental actions.Footnote 108 In a test study, Higginbotham found that the EDS is a valid and reliable measure for the bio-psychosocial experience of environmental disturbance.Footnote 109 Many of the following quantitative studies use this scale, or at least its solastalgia subscale.Footnote 110 Christensen and co-authors propose a variant of the EDS to ensure more consistency in its wording across different studies.Footnote 111 A study by Cáceres and co-authors offers a viable alternative to the EDS, namely the Scale of Solastalgia.Footnote 112

I discern, in the quantitative literature, a few factors that statistically increase the risk and impact of incurring solastalgia. The most significant impact factor is ‘place attachment’, defined as the ‘level of connection to or love of one’s home environment or the meaningful bond between people and environments’.Footnote 113 Empirical analysis consistently shows the closer that bond, the more disruptive the effect of environmental degradation, and the more serious is the experience of solastalgia.Footnote 114 For example, three studies find that the longer that someone resides in a certain place, the more attachment they create and the higher they score on solastalgia scales.Footnote 115 Qualitative research often deliberately focuses on long-term residents.Footnote 116 The emphasis on this factor in empirical data reinforces the conceptualization of solastalgia as a place-related phenomenon.

Place attachment can be understood as having two interrelated dimensions: place dependence and place identity. Place dependence, on the one hand, denotes the functional (materialistic) bonds between people and a place. For instance, people in rural environments sustained by small-scale farming rely heavily on their environment.Footnote 117 Professions such as hunting, environmental research or social work could also increase place dependence.Footnote 118 Additionally, Eisenman and co-authors suggest that vulnerable populations, often people from lower socio-economic backgrounds, tend to depend more heavily on the local economy and may not have the resources to move.Footnote 119 Indeed, two quantitative analyses provide modest empirical support for that hypothesis.Footnote 120 Place dependence intensifies the solastalgic experience when confronted with environmental loss.

Place identity, on the other hand, signifies symbolic, emotional and social meanings embedded in a certain place.Footnote 121 It is usually predicated by high levels of place dependence, but is not restricted to materialistic bonds with the environment. Some authors contend that place identity is generally higher in rural areas, where individuals are attached to their native places for cultural, social, and religious fulfilment.Footnote 122 Indeed, research by Elser and co-authors suggests increased solastalgia levels among respondents in rural counties compared to respondents in urbanized counties.Footnote 123 People in communities that care for certain nature parks, such as the Ahwerase community in Ghana, generally derive a form of personal and cultural identity and community attachment from that park. Such attachment leads to increased levels of solastalgia.Footnote 124 Qualitative research also suggests that farmers have an increased sense of place identity:Footnote 125 because their farmland is such an important part of their daily lives, they derive a certain pride and identity from it.Footnote 126

Another impact factor concerns the actual felt impact of environmental change.Footnote 127 The more invasive the impact of environmental change is, the more it increases the solastalgic experience.Footnote 128 For instance, Phillips and Murphy find that people who self-reported that their lives have been affected by coastal erosion experience solastalgia significantly more strongly than those who did not.Footnote 129 Similarly, the felt impact of bushfires was significantly related to solastalgia, as well as to mental health outcomes in research conducted by Leviston and co-authors.Footnote 130

There is some debate over whether social demographics like gender and age influence the experience of solastalgia.Footnote 131 Certain studies suggest that female respondents are more vulnerable to solastalgia than male,Footnote 132 although other research does not find such an effect.Footnote 133 Certain studies suggest a link between old age and higher levels of solastalgia,Footnote 134 whereas other researchers do not find this effect.Footnote 135 Benham and Hoerst state correctly that more research on these factors is needed, and suggest looking at the intersection of these demographics to uncover hidden effects.Footnote 136

The literature also heavily debates the occurrence of solastalgia in Indigenous communities,Footnote 137 with many authors arguing that solastalgia cannot appropriately describe the non-material loss suffered by Indigenous people. In their view, the Indigenous experience is fundamentally different. Solastalgia does not sufficiently take into account the societal inequities at play. It does not capture the traditional knowledge, the way of life, and the cultural identity that is inherent in their home environment.Footnote 138 Two thorough scoping reviews on solastalgia in Indigenous communities in Oceania conclude that the current state of the art contains insufficient evidence to suggest that Aboriginal peoples in a general sense suffer from solastalgia.Footnote 139 They contend that more research is needed from a decolonized, Indigenous perspective.Footnote 140 Other authors suggest that solastalgia is a fitting notion in the Indigenous context.Footnote 141 Notably, via quantitative data, Apiti and co-authors find an indirect link between cultural identification as ‘Māori’ and solastalgia, through the mediating factor of environmental identity. The argument is that being Indigenous enhances place attachment, which in turn is a strong predictor for solastalgia.Footnote 142

3.6. Main Critiques of Solastalgia

My review of the literature revealed some critical reflections on solastalgia. Firstly, some authors criticize Albrecht for his activistic alignments,Footnote 143 although there are no indications that these alignments distorted the integrity of Albrecht’s scientific work. If it did, the critique could now be considered redundant in the light of the numerous peer-reviewed studies that have shown empirically the existence and relevance of solastalgia. A second, more fundamental critique pertains to the limits of solastalgia in describing non-material harm in the face of environmental degradation. Environmental and climate injustice have roots in deeper sociological problems. For instance, a recurring theme throughout the qualitative solastalgia research is the historical power imbalances that precede and sustain many cases of environmental degradation.Footnote 144 For these reasons and more, solastalgia does not offer a full account of the inequality and turmoil experienced collectively by a community subject to environmental loss; solastalgia still takes the perspective of individual loss. While such critiques certainly merit further research, it suits the purposes of this legal analysis nicely, as I show in Section 4.1.

4. Bridging the Gap between Law and Psychology

With this clear understanding of solastalgia, its context and its components, the psychological validity and relevance of solastalgia is beyond doubt; however, its validity and relevance in legal science is yet to be established. In this part, I argue that solastalgia should be incorporated in the legal discourse as a type of harm. Firstly, I establish the validity of this claim, showing that solastalgia fits within the existing legal frameworks in Belgium as well as in the Netherlands; there is no need for additional legislative intervention. Secondly, I establish the relevance of solastalgia as a tool to develop our legal understanding of non-material environmental harm and to guide the judge in the measurement of harm.

4.1. Solastalgia as a Valid Type of Harm

As noted in Section 2.1, the Belgian tort law system requires harm to be personal. This means, in the environmental context, that the victim must be personally affected in a way that is different from how environmental degradation affects us all. Solastalgia fills this bill. Unlike eco-anxiety, solastalgia is not a collective feeling of distress, anger, and dismay about the current state of affairs vis-à-vis climate, war or other contemporary problems. Instead, it describes the loss of an individual’s private relationship with an environment in which they are embedded. That psychological limitation of this notion becomes a strength in the legal context. Belgian law requires a personal close connection with the environment (Section 2.2). In this sense, solastalgia conforms with Belgian law. In both the legal and psychological literature, connectedness with the environment, or place attachment, plays a decisive role.

In Dutch law, the fact that solastalgia does not constitute a psychiatric illness does not a priori hinder its legal qualification as a mental injury. Whether, and under what conditions, solastalgia can qualify as sufficiently serious is for judges to decide, assisted by medical professionals on a case-by-case basis. Arguably, the EBI-route offers a better approach to solastalgia, because it does not focus solely on the subjective impact of environmental loss; rather, it takes into account the nature, the gravity, and the consequences of the wrongdoing. Focusing especially on the consequences of the wrongdoing, I believe that the felt impact of the environmental degradation and place attachment with that environment could play a role. While solastalgia should always be subject to the legal tests to qualify as compensable harm, it can be argued that the EBI-route constitutes a strong legal basis to allow solastalgia.

Additionally, solastalgia is conceptually comparable with the non-material harm suffered after the loss of a loved one. In the Belgian tort law tradition, non-material loss arising from the death of a loved one has long been a compensable form of harm.Footnote 145 This practice was encapsulated in the Belgian Indicatieve Tabel (Indicative Table), a document that provides an overview of indicative fixed sums that apply to a certain type of harm.Footnote 146 Since 2019, Dutch tort law has also embraced affectieschade, the non-material loss from the death or serious permanent injury of a loved one.Footnote 147 Research shows that this development has rapidly gained footing in Dutch case law.Footnote 148 Solastalgia, a form of ecological grief, also pertains to the loss of a meaningful relationship, but with a cherished environment rather than a person. Although the solastalgia literature never claims that it is equivalent to grief over human loss, it does show that environmental loss can lead to a comparable type of grief, which is often disenfranchised in modern society.Footnote 149 Given that Belgian tort law also compensates for grief over the loss of cherished pets,Footnote 150 and that several cases in Belgian as well as Dutch tort law have already compensated for non-material loss after environmental degradation (Section 1.1), I argue that recognizing solastalgia as a separate type of harm is in line with current trends in both tort law systems.

4.2. Solastalgia as a Legally Relevant Type of Harm

In addition to its validity as a type of harm, solastalgia is also a relevant addition to the legal vocabulary around environmental harm. Firstly, solastalgia provides clear terminology for a psychological reality that thus far has been absent from most legal and public debates. The symbolic impact of adopting such a term should not be understated. It offers recognition for those suffering from a specific type of harm, which is essential for the symbolic task of awarding monetary relief for non-material harm (Section 1.2). Moreover, by drawing attention to the very real and objectively verifiable nature of environmental non-material harm, solastalgia increases the likelihood that this harm will be given due importance, and not undervalued relative to forms of material harm. For example, traditional fishermen not only have an important economic interest in the environmental welfare of a certain lake or river; they also have non-material interests in the ecological qualities of that lake. If the fish population in their home area dwindles, they lose their way of life, and possibly their identity as ‘fishermen’. The only difference between the material and non-material interests at stake here is that the former has a clear monetary value, and the latter does not. Solastalgia could help in breaking with the materialistic tradition of giving preference to the first type of harm and undervaluing the latter.Footnote 151

In practice, the solastalgia literature provides impact factors that could help judges in valuing the non-material harm more accurately. Based on these factors, I propose a method of valuation inspired by the method that is currently used in cases of loss of a cherished person. As established before, solastalgia bears conceptual similarities to grief; it should come as no surprise that these similarities extend to the phase of harm measurement.

Both Belgian and Dutch tort law have developed systems with fixed sums for specific types of grief. The Indicative Table in Belgium provides a comprehensive overview of sums per type of loss. The sums are non-binding for a judge, but carry strong authority in practice.Footnote 152 The Belgian Hof van Cassatie, the highest Belgian civil court, accepts a simple reference to the Indicative Table as a sufficient legal basis for harm measurement if the plaintiff does not invoke special circumstances.Footnote 153 The Dutch government later implemented a similar table, specifically for cases of affectieschade.Footnote 154 The Belgian and Dutch tables each contain a dual system for assessing non-material harm after the loss of a loved one.Footnote 155 On the one hand, they set out a closed list of interpersonal relationships for which compensable loss up to a specific amount is presumed; these lists of specific lump sums aim to avoid long and emotional debates in court.Footnote 156 On the other hand, the tables set out a residual possibility of obtaining compensation for the loss of close personal relationships outside that closed list.Footnote 157 For this option, the Belgian table requires the plaintiff to prove ‘a specific affective and durable bond with the victim’.Footnote 158

A similar method can be found for cases of solastalgia. Firstly, the residuary category could be applied to solastalgia. A plaintiff can claim compensation for solastalgia if they prove a specific affective and durable bond with the degraded environment. This essentially boils down to a more specific way of phrasing the requirement of a close connection expressed by Belgian legal literature or place attachment in the psychological literature. With that formula as a starting point, the judge should take into account (a) the place dependence (the economic dependence on the natural landscape), (b) place identity of the plaintiff (the ways in which the landscape has become a meaningful part of who the victim is), and (c) the felt impact of the environmental degradation. Additionally, judges should take into account that duration of residence plays an important role in place attachment.

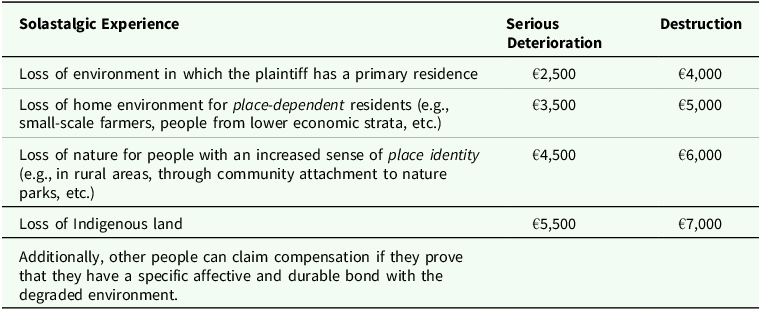

Secondly, to facilitate judgments and legal debates, a solastalgia table could be formulated. This would represent a closed list of environmental relations for which the occurrence of solastalgia is presumed. However, whereas such legal lists are based traditionally on extensive case law analysis,Footnote 159 the solastalgia table is based purely on psychological research, as the body of case law in Belgium and the Netherlands is still limited. For that reason, the following analysis is a mere simulation, in broad strokes, of what such a table could potentially look like. It should be used only as a guideline for actual judgments and as the basis for a future list, based on a more extensive case law analysis (see Table 1).

Table 1. Solastalgia Table

In the absence of a thorough case law review, I take €2,500 as a starting point, based on the lump sum determined by the Dutch Hoge Raad for residents of Groningen who have experienced at least two instances of property harm as a result of industrially induced earthquakes.Footnote 160 In the two columns, I created room for judges to distinguish between levels of impact experienced. The question of how pervasive the deterioration in the environment is should play a role in the measurement of harm. If it comes down to total destruction of the home environment, the victim should be awarded greater compensation.

I have created categories in the rows that deserve an increase based on the insights gathered in the psychological literature. With each category, I increase the amount by a symbolic €1,000 to recognize the increased level of solastalgia. The base category describes the most commonly investigated form of solastalgia, namely the deterioration of one’s home environment. The first increment is warranted for place-dependent residents: farmers, hunters, environmental researchers, social workers, people from lower socio-economic strata, and so on, all of whom are susceptible to increased levels of solastalgia. When these residents additionally develop a strong sense of place identity, by engaging with nature in an active way and attaching intense existential and cultural meanings to their environment, an additional increment in the table is warranted. In the last category, I retain a special place for Indigenous communities. The underlying assumption behind this last increment is that Indigenous people fulfil all the requirements of the solastalgia table, but the table does not suffice to capture the whole Indigenous experience of environmental degradation. This separate category serves only as an incentive for further research and to consider this significant form of grief from an Indigenous perspective. As neither Belgium nor the Netherlands is home to any Indigenous communities, this recommendation pertains mainly to future research in other legal systems.

4.3. Other Interdisciplinary Avenues

Tort law constitutes just one of the many avenues through which solastalgia can have an impact on legal decision-making. In this short paragraph, I give a brief overview of how solastalgia has already been picked up in legal literature and legal practice on several occasions. Firstly, solastalgia has already made its way into the legal literature on climate justice.Footnote 161 Secondly, from a human rights perspective, Townsend refers briefly to solastalgia to show how environmental change can be a threat to human dignity.Footnote 162 Indeed, in several cases, the European Court of Human Rights has taken into account non-material harm to decide on a treaty violation in cases of environmental degradation.Footnote 163 Thirdly, in cases of environmental permits, solastalgia can signify the non-material costs of expanding industrialization to counterbalance the focus on economic benefits. Kennedy reports on an Australian case in which a permit to expand a mine was denied because the court held that it would have significant negative impacts on the community that were not outweighed by the economic benefits. Solastalgia played a prominent role in this trial, with Albrecht himself as an expert witness.Footnote 164 The concept has been mentioned in numerous subsequent court cases in Australia.Footnote 165 Lastly, solastalgia can inform debates on migration law, as several studies establish a link between solastalgia and decisions to migrate.Footnote 166 A study by Adams and Ghanem in the Lebanese context shows how solastalgia also highlights the non-economic burdens of mass immigration.Footnote 167 Climate-induced and environmental migration will become a major societal challenge in the coming decades, for which the law should be prepared.Footnote 168 In short, there is further room to explore the relevance of solastalgia in the law in general.

5. Conclusion

As supported by the findings of this article, I propose the adoption of a new type of harm in Dutch and Belgian tort law: solastalgia. In doing so, tort law systems gain a tool for consistently acknowledging, assessing, and quantifying non-material environmental harm. Firstly, solastalgia gives a more prominent place to non-material harm stemming from environmental degradation. As shown in the interdisciplinary analysis, it is compatible with the current legal state of the art in both Belgium as well as in the Netherlands. Secondly, solastalgia is a specific, well-studied and clearly defined form of harm, with place attachment as a clear criterion to separate serious from trivial forms of environmental harm. These factors can allay the fear of non-material harm functioning as a Pandora’s Box. Thirdly, research on solastalgia has identified impact factors which lend themselves for creating a standardized way of measuring environmental non-material harm. The potential relevance of solastalgia in a liability context cannot be overstated.

As a pathway for future research, I hypothesize that adopting solastalgia as a type of harm could more broadly benefit environmental law and policy-making in general. In order to create just and inclusive environmental law and policies, the law should supersede the materialistic reflexes of contemporary society and pay closer attention to non-material forms of harm, even if they are more difficult to monetize. Shedding light on these forms of harm increases the possibilities for victims to claim their environmental rights and scrutinize environmentally destructive behaviour.

Acknowledgements

I thank my supervisors, Ilse Samoy and Ivo Giesen, for engaging with my research process as much as they did and for providing thorough feedback on the article. I also thank my dear friends, Elias Kruithof and Robin Michiels, for thoroughly proofreading the article and exchanging their views from a sociological and a psychological perspective. Lastly, I thank my father, Geert Van Eekert, for providing additional encouraging feedback on the last draft.

Funding statement

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declares none.