As early as the 1790s, sugar boycotts – a concrete effect of antislavery culture on British hearths and teatimes – were enthusiastically noted by reformists and publicly celebrated as part of the abolitionist campaign itself. With time, during the Victorian period, the remarkable story of antislavery’s public impact in Britain was only further enshrined as a cherished national narrative – not least to serve the domestic, nakedly capitalist purposes of high imperialism (Huzzey Reference Huzzey2012). Historians, then, have an abundance of leads to begin to unravel (and to demystify) how memories of antislavery, both personal and cultural, influenced British mores, customs, and discourse. When it comes to antislavery’s impact on the transnational culture of reform, though, which developed during the long nineteenth century and became so characteristic of the age, the sources are much more disparate. Nevertheless, it is not hard to find indications that memories of antislavery, as practised by British and American reformers, engrossed and influenced idealists across the world.Footnote 1

Writing in Pune in 1873, anti-caste and educational reformer Jyotirao Phule dedicated his pamphlet of revisionist history, Gulamgiri (Slavery), to

The good people of the United States,

As a token of admiration for their sublime disinterested and self-sacrificing devotion in the cause of Negro Slavery; and with an earnest desire, that my countrymen may take their noble example as their guide in the emancipation of their Sudra Brethren from the trammels of Brahmin thraldom.

With this dedication in English, Phule indicated an ardent personal admiration for abolitionism. With his wife Savitribai, Phule devoted himself to the fight against untouchability and the oppression of women, founding the first Indian girls’ school in 1848. The ‘truth-seeking’ strategy of their movement, Satyashodhak Samaj, was explicitly egalitarian, disregarding differences of caste, status, and gender, and mirrored American Garrisonianism, despite its critical orientation towards Marathi history, tradition, and language (Omvedt Reference Omvedt, Somanaboina and Ramagoud2022, 41–43; Salunke Reference Salunke, Somanaboina and Ramagoud2022).

Phule’s preface also contained a powerful directive to his readers regarding the shape the Dalit emancipation movement should take. The lack of mention of the Civil War betrays an eccentric view, even for the times, of how abolition in the United States came to pass. Taking into account Phule’s surprising choice to focus on American, rather than British, abolition, key to this dedication is the analogy between America and India as settler-colonial, multiracial states. The preface, also written in English, explained that the casteless suffered as much as the formerly enslaved and, using rhetoric hardly distinguishable from Garrisonian abolitionists’ invectives on national sin, directed readers to ‘attribute the stagnation and all the evils under which India has been groaning for many centuries past’ to this ‘system of selfish superstition and bigotry’ (Phule Reference Phule1873, 19). Phule’s movement was not to be one of restitution or of amelioration, but one of national transformation.Footnote 2

Memories of antislavery also spoke to the imagination of idealist denizens of Imperial China. In the Anhui Province, at the turn of the twentieth century, women’s advocate Jin Tianhe wrote:

Alas! My heart is filled with the desire to save Chinese women from the world of slavery, to issue an Emancipation proclamation. As a man, today let me take up the role of Garrison; if tomorrow I were to change into a woman, I would swear to become Beecher [Stowe]; in the next day, if I were to be made emperor, then I would take Lincoln as my model. What is the method for liberating slaves? Only education.

Often considered the first Chinese feminist pamphlet, Jin’s ‘The Women’s Bell’ wove together a close reading of European and American Enlightenment and humanitarian canons with a critical grounding in Chinese social thought. It appeared in multiple editions in China and Japan, broadcasting its influence during the first quarter of the twentieth century. By alluding to recent American history, Jin made the point that emancipation could be a rapid process of enlightenment, since ‘the slavelike nature of women in eighteenth-century England was no less strong than that in China’ (Jin 2013 [1903], 241). The reference also served to illustrate Jin’s passionate zeal, a match for that of sanctified leaders of the movement for abolition. Notably he did not reference any black leaders – even when analogical reasoning might lead one to expect this, Jin’s imagination went to Harriet Beecher Stowe.

Memories of antislavery had become global by the second half of the nineteenth century. This chapter discusses what these memories were and how they came to be so widespread. Offering a global typology of dominant motifs and models, it lays the groundwork to better understand the roots and strategic implications of women’s advocates’ discussions later on. Though key events, like those of the American Civil War, became global news in a world under the sway of the ‘new international information system’ (Britton Reference Britton2013), this chapter will suggest that antislavery’s impressive footprint was in large part down to the movement’s ambition. As historical research continues to uncover, the movement of organised abolitionism was transnational in its very fibres. This chapter complements the account of English and American organised abolitionism with its counterparts in France, the Low Countries, and the German states. Major English and American figures were in close communication with European allies, sharing materials, information, funds, and personal resources in hopes of rallying increased European support. In their classic account, Activist beyond Borders, Margaret Keck and Kathryn Sikkink designate antislavery a forerunner of the modern transnational advocacy network and offer a typology of tactics in which ‘information politics’ and ‘symbolic politics’ play a major role (Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998, 16). What follows is an examination of how the tactical activities of circulating information, symbols, and stories nurtured long-lasting and emotive memories of antislavery. These spoke to women reformers in special ways, regardless of whether they had seen the movement up close or not.

Antislavery and Organised Abolitionism: A Transnational Movement

The complex, gradual victories won against chattel slavery during the ‘century of progress’ have powered many commanding tomes (Davis 1984, 274).Footnote 3 The chequered history of organised abolitionism is, however, only one facet of this global political development, which started with the resistance of enslaved persons themselves and involved a variety of historical agents across the world (Mulligan Reference Mulligan, Mulligan and Bric2013; 2023; Suzuki Reference Suzuki and Suzuki2016). As the passages quoted indicate, however, for a long time, the self-appointed ‘abolitionist’ flank of the movement reigned supreme in the public imagination. In order to grasp the role antislavery played in the culture of reform in Western Europe, then, a sketch of the movement and its cultural impact is in order. Readers already familiar with the activities of the antislavery campaigns in the first half of the nineteenth century may wish to skip over the following historical background and move directly to the discussion of the movement’s cultural production.

Turning to the narrower institutional history of the antislavery movement, it quickly becomes clear that while it had an intrinsically transnational character, Anglo-American initiatives provided crucial encouragement as well as ideological leadership. Although Enlightenment thinkers formulated a variety of critiques of slavery (Hunt Reference Hunt2008, 160ff.; Ehrard Reference Ehrard2008), organised antislavery is usually traced back to particular Protestant dissenting sects. Foremost among them were the Quakers, a denomination whose adherents predominantly resided in Britain and the East Coast of the United States (Davis Reference Davis1999; Carey Reference Carey2005; Clapp Reference Clapp, Clapp and Jeffrey2011). The Quaker faith, with its religious tenets of spiritual equality and universal salvation, brought forth a correspondence network in which arguments against slavery slowly began to turn into a coherent antislavery discourse (Carey Reference Carey2005; 2012). From these Quaker beginnings, antislavery developed into an ecumenical movement in which other Christian denominations became important players. An antislavery petition signed by a number of German Quakers and published in Germantown, Pennsylvania, in 1688 arguably constituted the first act of public protest in the movement against the enslavement of Africans in America or Europe.

Sustained discussion on the evils of slavery did not equal abolitionism. By the 1830s, many people in Europe and the Northern US would have professed themselves to be against slavery, but few would have envisioned or favoured the institution’s outright abolition. Antislavery covers a wide swath of popular cultural production that was critical of slavery but did not necessarily oppose racism or agitate for the institution’s unconditional and rapid end. While influential criticisms like those by Alexis de Tocqueville, Gustave de Beaumont, and Harriet Martineau brought sophisticated, first-hand accounts of the realities of chattel slavery to broad European audiences, antislavery cultural production also included Romantic poetry, which might have commiserated with the black slave’s lot but still portrayed the enslaved as, at best, the exotic other; or which lamented enslavement only as an immutable part of the human condition (Hoffman Reference Hoffman1973; Wood Reference Wood2003; McGill Reference McGill and Tawil2016). The motif of the continued, voluntary service of new emancipates, for instance, was ubiquitous.

Abolitionists, on the other hand, actively strove for the institution’s end. They brought to the established cultural awareness of the suffering perpetuated by the slave system a reformist sense of individual responsibility to be part of world-historical change. Some of the most radical among them were those associated with William Lloyd Garrison, a New England editor whose reputation quickly spread in Europe (McDaniel Reference McDaniel2013; Morgan Reference Morgan, Mulligan and Bric2013). Garrison advocated the immediate and unconditional abolition of slavery, without either ‘repatriation’ of emancipates or indemnities for slaveholders, and he promoted the absolute equality between individuals, irrespective of racial, religious, and even sexual difference. He also assumed a radical, no-government pacifism under the nomer of ‘non-resistance’, which included a principled refusal to participate in the electoral process and a rejection of the American Constitution, which he considered just another two of the many institutions complicit with ‘slave power’. The radicality of Garrison’s positions was matched by his rhetoric, which denounced slavery as a ‘national sin’ that would incur bloody retribution.

The Quaker origins of organised antislavery go some way in explaining the unprecedented openness of organised antislavery to female participation. In Quaker religious practice, both women and men could be vehicles for divine wisdom, and both could therefore be involved in decision-making and leadership. This made American Quaker circles a fertile ground for women taking on more public roles. Antislavery’s deep ties to Quakerism and links with other traditions of religious dissent, particularly Unitarianism, also facilitated its associations with other radical social debates, where the position of women was being questioned. Unitarian circles, such as the South Place Chapel Circle, with which Harriet Taylor, John Stuart Mill, Sophia Dobson Collet, and several Chartists were affiliated, functioned as important meeting points for radical reformers and freethinkers in Britain (Clapp and Jeffrey Reference Clapp, Clapp and Jeffrey2011; Gleadle Reference Gleadle1995).

Antislavery arguments circulated in transatlantic familial and religious networks that spanned both England and the East Coast of the US (Carey Reference Carey2012). Eventually, a strategy of targeted agitation developed, by way of rallies, through an extensive alternative press, and was iconised in consumer artefacts (Risley Reference Risley2008, x; Goddu Reference Goddu2020). The cosmopolitan dimension of the reform impulse became codified as key abolitionists such as Garrison, Maria Chapman, and Frederick Douglass made the fostering of a transnational community and consensus the ‘bedrock’ of their campaign (Oldfield Reference Oldfield2020, 77; Taylor Reference Taylor1994; David Reference David2007; Midgley Reference Midgley2007; Sklar et al. Reference Anderson, Sklar and Stewart2007; McDaniel Reference McDaniel2013; Salenius Reference Salenius2016). The transnational communication networks they maintained contributed to Anglo-American antislavery discourses and reform culture, which took philosophical principles and practical examples from both sides of the Atlantic in the pursuit of an ‘Anglo-American Commons’ (Wright Reference Wright2017; see also Claybaugh Reference Claybaugh2007; Tamarkin Reference Tamarkin2008; Ahern Reference Ahern2013; McDaniel Reference McDaniel2013).

Britain and America

During the 1740s and 1750s, prominent Quakers began to advocate for the complete disassociation of their community from the slave trade and pioneered the British movement with their address to parliament in 1783 (Drescher Reference Drescher1987, 62; Davis Reference Davis1999, 218ff.). In 1787, a number of British Quakers formed a non-denominational group, the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, in which William Wilberforce, Granville Sharp, and Thomas Clarkson – Anglicans all – became the most prominent members. They launched both grassroots and elite campaigns and were heavily involved in effecting acts relating to the prohibition of the trading of Africans, which the UK and the US passed in 1807. Under British pressure, the slave trade was officially condemned at the Congress of Vienna in 1815. After the abolition of the slave trade, British abolitionists turned their attention to the abolition of slavery itself, founding the Anti-Slavery Society in 1823. From 1825 onwards, the Anti-Slavery Reporter published detailed reports about the realities of plantation life and the activities of the Society for a wide audience, and, by the early 1830s, the abundance and efficacy of propaganda meant that planter lobbyists faced an overwhelming tide of ‘lectures, sermons, public meetings, tract warfare, [and] newspaper coverage’ (Walvin Reference Walvin, Bolt and Drescher1980, 158).

British antislavery campaigners relied heavily on the mobilisation of public opinion, and their efforts at this tactic, honed across both the campaign against the trade and against the institution, proved enormously successful (Walvin Reference Walvin, Bolt and Drescher1980; 1982; Drescher Reference Drescher and Walvin1982). Convincing not just lawmakers but the public that the slave trade was an ‘enormous evil’ which they had a moral duty to resist took both fact-finding and explicitly emotive means (Wilberforce Reference Wilberforce1789). Powerful affective visuals, such as the diagram of the Brooke’s slave ship (1787), which showed the conditions kidnapped Africans had to endure in the Middle Passage, and Josiah Wedgewood’s medallion ‘Am I Not a Man and a Brother?’ (1787), which became the logo of the campaign, were widely circulated among British audiences and beyond (Lentz Reference Lentz, Brahm and Rosenhaft2016, 187; Wood Reference Wood2010, 19; Cutter Reference Cutter2017, 29ff.; Yellin Reference Yellin1989). Literary production was also effectively employed to promote the cause. Thousands of copies of William Cowper’s popular The Negro’s Complaint (1788) were circulated by the Anti-Slavery Society under the title ‘A Subject for Conversation at the Tea-Table’, while the publication of The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave in 1831 attests to the topic’s sustained popular appeal (Wood Reference Wood2003, 82).

Until 1831, most antislavery advocates argued for a gradual process of abolition. Notably, the first claims for immediate, rather than gradual, abolition originated with a splinter group of British abolitionist women, with the publication of Elizabeth Heyrick’s pamphlet ‘Immediate not Gradual Abolition’ in Birmingham (1824). As Clare Midgley (Reference Midgley2004) has documented, women played an unprecedentedly active part in antislavery agitation. Individuals such as Heyrick and Anne Knight were prominent voices for ‘moral radicalism’ within the movement, while middle-class women participated in large numbers in pressure-group politics (Gleadle Reference Gleadle2001, 73). In the 1790s, women were the driving factor behind West Indies sugar boycotts, blurring the boundaries between domestic consumption and the public good (Sussman Reference Sussman1994; Midgley Reference Midgley1996; Holcomb Reference Holcomb2014). In the 1820s and 30s, they were closely involved in raising funds, spreading information, and organising meetings. Women’s involvement, including from the working class, was pivotal for the flourishing of petitioning, that innovative signature move of British popular abolitionism. Through this activity they were, in fact, the organisers and signatories of the two largest national public expressions against colonial slavery (Midgley Reference Midgley2004, 62–71, 83–86).

The extent of women’s autonomous political action for this cause has led commentators to suggest that their activity can be seen as proto-feminist (Midgley Reference Midgley2004, 115; see also Ferguson Reference Ferguson1992, 3). Even though only a vanishingly small minority of antislavery women voiced any support for legislative change in the relations between the sexes, as Clare Midgley explains, their ‘outspoken criticisms of the male leadership of the campaign, and quarrels over matters of antislavery principle with their brother societies [involved a] public questioning of male authority, an assertion of independence, and a recognition that their views were not adequately represented by men’, which was ‘a necessary precursor to any formulation of demands for women’s independent legal and democratic rights’ (Midgley Reference Midgley2004, 115).

With the abolition of the ‘apprenticeship’ system of indentured labour in 1838, the Anti-Slavery Society transformed into the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society (BFASS).Footnote 4 They made efforts to create an international network of antislavery societies, with agents regularly travelling across Europe to find allies (Janse Reference Janse2015, 128–129). To this end, leaders of the BFASS organised the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in June 1840. The event united over 400 delegates, including around 40 Americans and a handful of Frenchmen, as well as thousands of casual visitors at the Freemasons Hall in London (Maynard Reference Maynard1960, 456). Though this event was meant to constitute a historic advance in organised antislavery, from the first day it was rife with disagreement and disorder, as the broadly conservative attitudes of the BFASS and the progressivism of the American Garrisonians led to clashes (McDaniel Reference McDaniel2013, 684ff.; Maynard Reference Maynard1960; Bric Reference Bric, Mulligan and Bric2013). One of the major schisms in which the attitudinal, tactical, and theological differences between members came to the fore was the controversy over women’s active participation in antislavery agitation. Despite repeated, vocal protests from BFASS, the Garrisonian delegations from Pennsylvania and Massachusetts included women. After fierce debates on the opening day of the conference, women were ultimately admitted only as spectators. This controversy ultimately ensured that the Convention would be remembered primarily as the foundational event of the international women’s movement, rather than as a milestone in transnational antislavery (Sklar Reference Sklar1990; Kennon Reference Kennon1984).

By 1840, women’s oratory and their equal participation in antislavery proceedings had also become a major bone of contention within American organised antislavery. Not least because slavery was a profitable domestic issue rather than a foreign one, and because the Constitution had left its regulation up to individual states, antislavery agitation in the US took a different course than it did in Britain. The American debate often turned violent, as slave insurgencies and escapes were brutally punished and antislavery advocates were threatened, or even attacked, as in the case of the murder of abolitionist printer Elijah Parish Lovejoy in 1837. John Brown’s failed attempt at instigating violent insurrection among the Southern black population and his hanging in 1859 further dialled up the level of tension and mistrust between the North and the South. When, in reaction to the election of Abraham Lincoln, seven Southern states seceded from the Union, these tensions flared up into the American Civil War (1861–1865). These events were followed by the Emancipation Proclamation (1863) and then the Thirteenth Amendment (1865), which abolished chattel slavery throughout the US. The Fourteenth Amendment (1868) affirmed the principle of birthright citizenship in the Constitution and prohibited any state within the United States from denying any person life, liberty, or property without due process of law, or denying any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. The framers of the Amendment wanted to insure that the newly emancipated former slaves had basic rights, but they also understood that the Amendment protected all ‘persons’ within the states. That said, the Amendment also first introduced the word ‘male’ into the Constitution – an innovation to which some feminist abolitionists strenuously objected, with a bitterness that inflected their later commemoration of this moment.

Organised antislavery is often dated to 1 January 1831, when Garrison first published his weekly newspaper, The Liberator (Kraditor, Reference Kraditor1989, 3). That year also saw a major rebellion led by the enslaved African American preacher Nat Turner, which resulted in more brutal popular and legislative repression of the enslaved community in the South. In 1833, reformers from ten states founded the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS), presided over by Garrison. The Liberator continued to operate without interruption until abolition in 1865, maintaining its editorial independence from any specific antislavery organisation. By the late 1830s, the distinct antislavery theology associated with The Liberator, which stressed abolitionists’ spiritual and physical suffering and adopted a Christian vocabulary of martyrdom and prophecy, had become widely shorthanded as ‘Garrisonism’ (Santana Reference Santana2016, ch. 1). Garrisonians translated their Quaker-inflected conviction of a higher authority based on the principles rather than the letter of the Bible into uncompromising prose (Kraditor Reference Kraditor1989, 91ff.; Bormann Reference Bormann1971; Perry Reference Perry1973; Boocker Reference Boocker1999; and McDaniel Reference McDaniel2013, 35ff., on the mobilisation of shame). Seeking to achieve abolition and the end of racial prejudice through ‘moral suasion’ of the public, they invested in a firebrand agitational style, which condemned slavery as a sin and a shameful blot on the nation. This register met with significant resistance and mockery, further alienating moderate antislavery allies (Boocker Reference Boocker1999; Lamb-Books Reference Lamb-Books2016, 107ff.).

The radicalism of Garrison and his allies, and their reluctance to compromise, led to deep rifts within the AASS, with splinter groups breaking off in 1839 (the Liberty Party) and 1840 (the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society). Prominent Garrisonians were not just antislavery, but also anticlerical, anti-institutional, and anti-sabbatarian; non-resistant, non-voting, and non-discriminatory. Garrisonians saw themselves as fighting the overwhelming tide of ‘might against right, policy against justice, armed usurpation against lawful authority, the rich and powerful against the poor and unprotected, class domination against the will of the people legally and constitutionally declared’ (Garrison Reference Garrison, Merrill and Ruchames1981 [1877], 470). These ‘radicals’, or ‘ultraists’, connected their antislavery to other causes that were unacceptable to the moderate and religious common denominator, including women’s equal rights – beginning with the right of female antislavery orators such as the Grimké sisters to address assemblies. Garrisonians eventually explicitly welcomed women’s rights claims under the banner of an oecumenical, non-doctrinal abolitionism centred on universal principles and human rights (Kraditor Reference Kraditor1989, 58–61; DuBois Reference DuBois1998 [1979], 245). In 1837, Garrison explained that their chosen motto of ‘universal emancipation’ included women: ‘As our object is universal emancipation – to redeem woman as well as man from a servile to an equal condition – we shall go for the RIGHTS OF WOMAN to their utmost extent’ (‘Prospectus’ 1837; see also Hogan Reference Hogan2008, 67).Footnote 5

The Garrisonian rejection of the authority of national institutions was also reflected in supporters’ fundamental cosmopolitanism. The Liberator’s masthead proclaimed ‘Our Country is the World – Our Countrymen are All Mankind’, and Garrison further specified the meaning of this cry in his address to the Boston Peace Conference in 1838: ‘We love the land of our nativity, only as we love all other lands. The interests, rights, and liberties of American citizens are no more dear to us than are those of the whole human race. Hence we can allow no appeal to patriotism, to revenge any national insult or injury’ (‘Declaration’ 1838, 3). As W. Caleb McDaniel (Reference McDaniel2013) has traced in detail, Garrisonians communicated with other emancipation movements in extensive transnational networks. Their philosophical principles, including their radical formulation of cosmopolitanism, circulated in these networks and served as a source of inspiration for women’s advocates for decades to come.

Although Garrisonian abolitionists intrigued American and European audiences, they were only a minority voice. Most antislavery politicians rejected the call for immediate abolition as unfeasible and destabilising. Moreover, the extent to which abolitionists in fact swayed public antislavery sentiment in the North is subject to debate. Rather, it saw an upsurge after the passing of the Fugitive Slave Act (1850), which stipulated that enslaved persons who managed to escape to the North must be captured and returned. The intensified media coverage of escapes and of the instances of civil disobedience that ensued, combined with the publication of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), which was framed as a direct response to the Act, did much to mobilise public opinion in the North (Gara Reference Gara1996, 131–140; Rochon Reference Rochon2000, 226–229; Davis Reference Davis2014, 233–234). With the formation of the Republican Party in 1854, abolition, though not immediatism, became part of a national political programme.

By the late nineteenth century, many European commentators would seek to claim the mantle of opposition to slavery as an important justification for imperialism (Midgley Reference Midgley and Midgley1998; Huzzey Reference Huzzey2012; Forclaz Reference Forclaz2015; Stornig Reference Stornig2017). However, it was only in America and Britain that the antislavery movement had in fact been a significant shaping force in politics and culture. The antislavery campaign had successfully called into being a diverse coalition of men and women across religions and social classes and had pioneered new mass agitational techniques such as boycotts and petitions, making it a crucible for the development of modern organised protest (Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998; Zaeske Reference Zaeske2003; Janse Reference Janse2007; Drescher Reference Drescher2009, ch. 8; Stamatov Reference Stamatov2010). In Britain, antislavery became an unprecedentedly popular movement. At the high point of British abolitionism in the early 1830s, abolitionist meetings drew thousands of attendees and local abolitionist groups dotted the countryside. By 1830, the Anti-Slavery Society had published over half a million tracts, contributing to the staggering scope of antislavery petitions: in 1831–1832 around 1.5 million names graced abolitionist petitions (Walvin Reference Walvin, Bolt and Drescher1980, 159–160; Drescher Reference Drescher2009, 229). In the US, where major abolitionists were allied with other radical causes, and where the institution of slavery lay at the heart of the political union, many viewed the abolitionists as dangerous subversives. Nevertheless, the rapid growth of organised abolitionism in the 1830s, which built on British agitational techniques, brought such a flood of antislavery petitions to Congress that a ‘gag rule’ prohibiting any discussion of the issue was put in place (Drescher Reference Drescher2009, ch. 11).Footnote 6 These mass stirrings were not matched in Continental Europe. Despite this, antislavery arguments did penetrate cultural and intellectual circles which were crucial to the development of women’s rights advocacy.

France

Although France was the first Continental stage for antislavery mobilisation, the cause never became broadly popular. In 1788, a small coterie of prominent philanthropists and Republicans, including the Abbé Grégoire, the Marquis de Condorcet, Olympe de Gouges, and Mirabeau founded the Société des amis des Noirs, which credited, and was closely dependent on, the London Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade (Daget Reference Daget, Bolt and Drescher1980; Jennings Reference Jennings1992). The Amis des Noirs, however, remained an elite group with limited political influence (Daget Reference Daget1971; Jennings Reference Jennings1992; Peabody Reference Peabody and Suzuki2016). As Doris Kadish and Françoise Massardier-Kenney have explored, slavery did draw significant cultural commentary, with a noticeably large share produced by women (2008; 2010; 2012).

In 1791, a major revolt broke out on Saint-Domingue, which eventually turned into the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804). In an effort to quell the storm of revolutionary emancipationism and maintain their weakening control over the colonies (Drescher Reference Drescher2009, 162; Blackburn Reference Blackburn2013, 197), the Constituent Assembly eventually proclaimed general emancipation on 4 February 1794. In 1802, however, before the decree had even been properly implemented, Napoleon reinstated slavery throughout the colonies. Only Saint-Domingue, which became the independent nation of Haiti in 1804, escaped this fate. The ‘spectre’ of the violence and destruction witnessed in Saint-Domingue weakened French sympathy for all antislavery efforts (Geggus Reference Geggus and Richardson1985, 129ff.; Drescher Reference Drescher2009, 178; Popkin Reference Popkin2010, 290; Davis Reference Davis2014, 50–51). Colonial lobbyists and opponents blamed abolitionists for slave insurrections in the West Indies and further undermined them with accusations of clandestine support for British interests (Drescher Reference Drescher1991; 2009, 155).

In 1822, French organised antislavery was renewed when the ecumenical charitable Société de la morale chrétienne created a subcommittee devoted to the abolition of the slave trade. Encouraged by the British Slavery Abolition Act, this society was succeeded by the Société française pour l’abolition de l’esclavage in 1834 (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2000, 213; Drescher Reference Drescher2009, 281). Again, French organisers worked closely together with their English counterparts, on whom they drew for information and material support (Daget Reference Daget, Bolt and Drescher1980, 71; Schmidt Reference Schmidt2000, 213ff.). For instance, the BFASS supported the viability of the bimonthly review L’Abolitioniste français by regularly purchasing 110 copies, 100 of which were to be distributed in France (Jennings Reference Jennings2000, 194). Though French organisers also circulated petitions in the 1840s, the thousands of signatures they could muster were a modest result compared to the numbers collected in England (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2000, 237; Drescher Reference Drescher, Sklar and Stewart2007, 106). These petitions also included female signatories, but to antislavery leaders’ regret, in contrast to England, French women were often afraid to compromise themselves through this ‘eccentric’ act (Drescher Reference Drescher, Sklar and Stewart2007, 107).

While the Société de la morale chrétienne may have been a ‘Who’s Who of the leaders of the liberal opposition’, it had no legislative sway despite its predominantly parliamentary strategy (Jennings Reference Jennings2000, 10). The mostly Paris-based Société lacked the dynamism and diversity to set up a broad-based movement that could engage in pressure politics. More strident parties, such as the free planter of colour Cyrille Bissette, whose Revue des colonies was an important conduit for information about the French Antilles and antislavery arguments, accused their efforts of being ‘timid and insufficient’ (quoted in Jennings Reference Jennings2000, 72). Naomi Andrews has recently contributed to a fuller picture of the spectrum of French antislavery with her explorations of ‘romantic socialist humanitarianism’ (2020; 2013). Basing themselves on models of solidarity and associationism that ran directly counter to liberal antislavery and its laissez-faire assumptions, these reformists responded to liberal efforts with overt hostility, denouncing their proponents, as prominent socialist Charles Fourier did, as ‘Anglomaniacs’ (Andrews Reference Andrews2013, 512). They also tended to support French colonial efforts in the Atlantic and Algeria as an extension of the social revolution they proposed. As addressed in Chapters 2 and 3, this intellectual tradition fed the thinking of French women’s rights advocates of the period. However, up until 1848, the French general public outside of Paris generally thought of antislavery as an English cause (Drescher Reference Drescher2009, 281).

In the months leading up to the February Revolution of 1848, French organised antislavery had been at its most productive; over two hundred pamphlets and brochures denouncing slavery appeared, as well as numerous journal articles (Jennings Reference Jennings1969, 376). The overthrow of the July Monarchy suddenly brought temporary ministerial posts to several prominent abolitionist Republicans – among them Victor Schœlcher – who were determined to make immediate emancipation one of the first acts of the young republic. Abolition was formally proclaimed on 27 April 1848 and enshrined in the new constitution, less than a week after the new Assemblée constituante had been sworn in. In testament to the symbolic importance of emancipation to the new Republican government, alongside the abolition decree the provisional government decreed that abolition should be celebrated annually by a ‘fête de travail’ presided over by the highest officers of the colonial government.Footnote 7

The Low Countries

Compared to British and even French mobilisation, the limited nature of Dutch antislavery engagement has posed a challenge for historical commentators (Kuitenbrouwer Reference Kuitenbrouwer1978; Emmer Reference Emmer, Bolt and Drescher1980; Drescher Reference Drescher1994; Oostindie Reference Oostindie1996; Janse Reference Janse2015). In the words of David Brion Davis, ‘despite repeated prodding from British abolitionists, the Dutch remained stolidly indifferent to the whole abolitionist campaign’ (1987, 811; see also Emmer Reference Emmer, Bolt and Drescher1980; Stipriaan Reference Stipriaan2005). The Netherlands was a powerful colonial player, economically liberal and under the sway of the international Protestant revival movement – so a popular campaign similar to the one in Britain might have been expected.Footnote 8 As Maartje Janse has meticulously traced, however, there were several factors that dampened the success of Dutch efforts. Among these were the disagreements between liberal and Protestant abolitionist organisers, resulting in a failure to launch an ecumenical movement; royal efforts to discourage the movement; a disheartening preoccupation with the lack of funds considered necessary to compensate slaveholders; and counterproductive British efforts to import their model (Janse Reference Janse2007; 2015).

As in France, British efforts were a crucial factor in the development of organised antislavery (Emmer Reference Emmer, Bolt and Drescher1980; Janse Reference Janse2015). British antislavery agents organised at least eight visits to the Netherlands between 1840 and 1858 (Janse Reference Janse2015, 128) and faithfully kept up correspondence. They first made inroads in Rotterdam, which was home to a sizeable British community (Janse Reference Janse2007, 56; Van Stipriaan Reference van Stipriaan2020, 219–326). Quaker minister and reformer Elizabeth Fry’s visit to the Netherlands in 1840, part of an international philanthropic tour by key figures of the BFASS, made a special impression, particularly on women (Drenth and De Haan Reference Drenth and de Haan1999; Janse Reference Janse2007, 55–56). Soon after this visit, Rotterdam saw the founding of both a men’s and a women’s organisation, which published several pamphlets. The English name of the Ladies Anti-Slavery Committee is a testament to its international orientation.

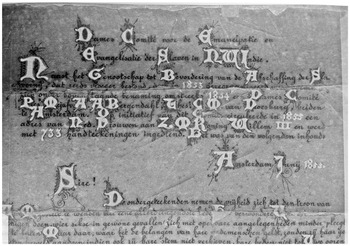

Signatories to antislavery petitions numbered in the hundreds. There were two women’s petitions among the number King Willem III received. The Ladies Anti-Slavery Committee collected 128 signatures in 1842, predominantly from the Rotterdam urban elite, including about 30 with British backgrounds (Van Stipriaan Reference van Stipriaan2020, 324). In 1855, 733 women from Amsterdam signed an address which explained that though they did not want ‘to intervene in matters of political economy’ [treden niet op het gebied van staatshuishoudkunde], they felt duty-bound to ‘issue a cry’ for enslaved women, who could not represent themselves (quoted in Janse Reference Janse2007, 109–110). Antislavery petitions were a noteworthy development in Dutch political culture (Janse Reference Janse2019), but their political impact was negligible.

Initially, Dutch antislavery organisers tried to avoid being associated with British tactics, which suffered from a reputation for radicalism (Janse Reference Janse2015, 142–143). However, this changed after the publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, when Dutch antislavery underwent a revival (Stipriaan Reference Stipriaan2005, 51–52; Janse Reference Janse2007, 91ff.). During this period, the tone of antislavery agitation began to reflect the anglophone emphasis on sentimental appeal, also felt in the wording of the 1855 petition (Janse Reference Janse2007, 91ff.; Huisman Reference Huisman2015, 60ff.). Sentimental antislavery motifs, and particularly Uncle Tom’s Cabin, also exerted their cultural influence in mid-nineteenth-century Belgium (Absilis 2022, 155–164).

In the 1850s, many of the original organisers renewed their efforts and the movement finally gained some popular appeal. In 1853, members of the Protestant Réveil founded the Society for the Advancement of the Abolition of Slavery, which published its own journal. Membership of this organisation peaked at 630 in the mid-1850s, when women and adolescents, too, started to form groups of their own (Janse Reference Janse2007, 103ff.). These women were not as outspoken as their British counterparts. The most high-profile female antislavery advocate was Anna Amalia Bergendahl, who, inspired by Fry and with the advice of key BFASS figures, ran a fundraising association oriented primarily towards the manumission of enslaved individuals (Janse Reference Janse2007, 103–104, 111; 2020).

Even during this height, however, antislavery did not root very deeply in the Netherlands. The revived interest in antislavery would prove short-lived; the Society had mostly ceased operations by the time slavery was finally abolished in the West Indies in 1863 (Janse Reference Janse2007, 122). Notably, Dutch organised efforts focused on slavery in the West Indies, with little to no attention paid to the widespread practice in its East Indies territories or slaveholding among the Boers in South Africa.Footnote 9 This selective lens was at least partly influenced by the transnational cultural fascination with plantation life in the Americas and by the structure and preoccupations of the English and American campaigns. Réveil circles, however, kept the memory alive, and the 1855 ladies’ petition would be commemorated by way of an ornate reproduction at the 1898 Dutch National Exhibition of Women’s Labour (Figure 1.1; Van den Elzen Reference van den Elzen, Paijmans and Fatah-Black2025).

Figure 1.1 Detail of an embellished reproduction of a Dutch ladies’ antislavery petition (1855), produced for the 1898 National Exhibition of Women’s Labour. The figure of ‘733’ signatures is proudly illuminated on the left.

Belgium gained independence from the Northern Netherlands in 1830, during a time when powerful industrial development was ramping up. Officials were soon on the lookout to make colonial acquisitions for the new nation, and after various attempts, ranging from the unsuccessful to the catastrophic, Leopold II assumed personal control over the Congo Free State in the 1880s. Abolition, then, was not on the Belgian political agenda until the wave of imperialist European antislavery zeal of the later nineteenth century. Antislavery and other philanthropic promises had been part of Leopold’s bid for control over the Congo at the Berlin West Africa Conference of 1884–1885, and the Catholic Société antiesclavagiste de Belgique, founded in 1888 to combat Arabic slavery in Africa, organised military expeditions in eastern Congo.

German States

Scholarship on German and Central European involvement in colonialism, slavery, and the slave trade has accelerated over the last decade.Footnote 10 For a long time, their role was assumed to be marginal, and, accordingly, their abolitionism of little significance. However, with the intellectual retreat of methodological nationalism, more awareness has developed of alternative, broader European implication patterns in colonialism, for instance through consumption, missionary work, the arms trade, and emigration (Wimmer and Glick Schiller Reference Wimmer and Schiller2002, 301). Research in this vein has brought to light countless other European actors.

Despite a long ‘colonial cult’ (Zantop Reference Zantop1997, 2), the fact that the German national colonial project only began after unification in 1871, and that the Austrian and Prussian governments had signed the declaration condemning the slave trade at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, meant that Germans felt soothed by a false sense that they had played no part in slavery. During the Enlightenment, this sense became an important and lasting part of German self-image (Koch Reference Koch1976, 533; Lentz Reference Lentz2020, 366–367; Honeck Reference Honeck2011; Garrison Reference Garrison2019; Köstlbauer Reference Köstlbauer, Pargas and Schiel2023). An ‘important source of moral capital in the German discourse’, it further developed in a transatlantic diasporic conversation (Lentz Reference Lentz, von Mallinckrodt, Köstlbauer and Lentz2021, 302). As Germans moved to the United States, particularly after 1848, the issue of slavery became part of the negotiation of their Americanisation, which played out on both sides of the Atlantic (Wiegmink Reference Wiegmink2017; Garrison Reference Garrison2019). German-American abolitionism became especially pronounced after the arrival of a new wave of refugees after the revolutions of 1848, many of whom opposed slavery ‘with a ferocity rarely seen among immigrants’ (Honeck Reference Honeck2011, 3; Brancaforte Reference Brancaforte1989).

Up until the 1840s, German antislavery remained the province of individuals in liberal intellectual networks (Lentz Reference Lentz2020, 231–232). Possibly the most influential among these was the explorer naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, whose criticisms of slavery circulated among German, American, Spanish, and French audiences.Footnote 11 These antislavery liberals also included women, such as Ottilie Assing, the close friend of Frederick Douglass, who translated his My Bondage and My Freedom into German; Göttingen-based belletrist Therese Huber (Diedrich Reference Diedrich1999; Lentz Reference Lentz, Brahm and Rosenhaft2016); and Forty-Eighter Mathilde Franziska Anneke, who became a notable author of German-language antislavery fiction after her migration to the US (Wiegmink Reference Wiegmink2022, 224–225).

The BFASS maintained a network in Germany and made several attempts to invigorate German abolitionism, sending out at least eight emissaries between 1839 and 1856 (Lentz Reference Lentz2020, 245). Their main point of contact was the liberal philosopher Friedrich Wilhelm Carové, a passionate abolitionist who supported the aims of the BFASS in a range of ways, besides regular publications. He played a key role in the conferral of a Heidelberg University honorary doctorate for the black historian and abolitionist James Pennington in 1849 (Lentz Reference Lentz2020, 265). In March 1848, Carové and several colleagues announced a national German antislavery society aimed, like the BFASS, towards a broad general public (Rodriguez Reference Rodriguez2015, 763; on the British network’s influence, Schüller Reference Schüller and Grunwald2004; Lentz Reference Lentz, Brahm and Rosenhaft2016; 2020). They printed at least 1,000 copies of their call, indicating their ambitions for a British-style, popular movement (Lentz Reference Lentz2020, 332–333). Little was heard from the association, however, after its first announcement. The 1848 Revolution aborted the attempt, but the striking lack of traction may also have had to do with the German self-image, as comments such as this Bavarian newspaper’s in 1847 suggest: ‘[Carové’s] admonition [to fight slavery] is superfluous; most Germans have already made efforts for abolition and did not first await Herr Carové’s sermon.’Footnote 12

German states did not have organised abolitionism even to the extent that the lukewarm Dutch mustered. However, as Sarah Lentz has recently demonstrated, despite the lack of broader organisations, the 1840s and 1850s saw a range of small-scale pressure tactics, such as spreading consumer awareness, and support for Anglo-American actors, including African American advocates and, particularly, the BFASS (Lentz Reference Lentz2020, 367–368). Culturally, moreover, antislavery was a significant sentiment. Liberal, radical, and Protestant networks strongly identified with the principle and, as in the Netherlands, Uncle Tom’s Cabin proved a broad cultural touchstone in the second half of the nineteenth century, to which antislavery philanthropists were happy to refer (Stornig Reference Stornig2017, 530; Lentz Reference Lentz2020, 234–242).

A Tally

This comparative look at the development of abolitionist organising in different contexts raises several important points for any consideration of the impact of antislavery on nineteenth-century reform culture. First, despite the emphasis in historical commemorative practices on abolition as a series of national achievements – a characteristic holdover of late imperial chauvinism – antislavery organising and rhetoric has always operated in and been oriented towards a transnational sphere. As Brycchan Carey has extensively documented, from its Quaker origins, antislavery rhetoric developed in a transatlantic conversation between dissenting communities (2012). Even when the emphasis on the national frame was of the utmost rhetorical importance, such as the Garrisonian denunciations of slavery as a national sin and of the Constitution as a pro-slavery document, transnational networking was a key and sustained part of the abolitionist agenda (McDaniel Reference McDaniel2013; Wiegmink Reference Wiegmink2022). This orientation was not just felt in the actions of reformers, but also influenced their store of arguments, language, and iconography.Footnote 13 Secondly, Anglo-American efforts were vital to organised abolitionism in Western Europe. The BFASS supplied materials, information, expertise, encouragement, and, at crucial moments, funds to their contacts on the mainland. Meanwhile, the celebrity of American figures like Garrison and Stowe increased the public profile of the cause well beyond the often institutionally oriented activities of local abolitionist circles. A side effect of this publicity was that in the early decades, efforts to set up a mass campaign to end chattel slavery raised eyebrows as a peculiar British phenomenon, while, in 1850s and 1860s, slavery was seen primarily as an American cause. This displacement had a profound and pernicious effect on the collective memory of slavery and abolition for decades to come. It allowed European audiences to forget (for lack of a better word) their own communities’ involvement, past and ongoing. Thirdly, across the board, abolitionism proved among the earliest humanitarian causes hospitable to women’s contributions and political opinion. Several factors played a role in this, among which were: the openness to women of one of the dominant linguistic modes of antislavery protest, sentimentalism; the invention of characteristically domestic forms of activism, such as consumer activism and fundraising by means of fairs; and the trailblazing, publicised willingness of some Quaker and Unitarian women to step into the public sphere.Footnote 14 Unlike the UK and the US, however, there was no clear overlap between organised abolitionism and later women’s rights movements. Fourthly, in all European contexts, the cultural impact of antislavery rhetoric far outstripped its limited local organisational efforts. To understand how the abolition movement came to be part of the imaginative horizon of reformers around the world, and why it became especially associated with women, it is important to acknowledge that it was not primarily the history of the movement, but its adept myth-making and innovative strategies of cultural production, which provide crucial insight.

Cultural Production and Memories of Antislavery

After 1852, for many, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin became the urtext of slavery and abolition (Meer Reference Meer2005; Kohn et al. Reference Kohn2006; Parfait Reference Parfait2010; Davis and Mihaylova Reference Davis and Mihaylova2018). Part of the success of Stowe’s explosive novel in Europe, however, was due to the fact that the novel and its many retellings cemented and narrated afresh motifs, stories, and emancipation plots that were known to audiences already. The baying bloodhounds of brutish planters; pious Tom’s upcast eyes; light-skinned Eliza’s despair; the moral improvement of young Topsy, ‘one of the blackest of her race’, under the tutelage of white Eva, with her ‘visionary golden head’; a lackadaisical Southerner planter’s reference to an inevitable and imminent ‘dies irae’ – these were reformulations of familiar themes, and they were not necessarily taken as fiction (Stowe Reference Stowe2006, 309, 192). Memories of antislavery in the broad sense, of a shared repertoire of representations of colonial slavery, and in the narrow sense, of shared conceptions of the history of the antislavery movement, had been widely adopted into Continental reform culture and, more specifically, into the usable past of networks of reformists, by the 1830s.

The translation and circulation of information about the realities of plantation life and of the slave trade were key activities of organised abolitionism, through tireless correspondence as well as print. Authoritative and much-translated accounts included the writings of Thomas Clarkson (Debbasch Reference Debbasch1991; Schmidt Reference Schmidt2000), especially the diagram of the ‘Brooke’s’ slave ship (1787) included in his History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade (1808), and Henri Grégoire’s De la littérature des nègres (1808), which became a ‘standard among abolitionists in the Atlantic world’ (Lentz Reference Lentz2020, 14).Footnote 15 In addition to these information politics, abolitionists also saw the strategic value of emotive and stylised depictions, and they welcomed the artistic treatment of slavery if it supported their cause (e.g., ‘Extrait du règlement’ 1826; see also Bric Reference Bric, Mulligan and Bric2013, 66–67). As John Oldfield has remarked, many leaders of the antislavery movement did not in fact travel much (2020, 9) and they were attuned to the emotive power of artistic representation. Abolitionists were often happy to recruit earlier depictions for their cause, modifying them as needed. This contributed to the curious amalgamate of fact and fiction, of powerful observation and facile stereotype, and of crowd-pleasing and stern reform-oriented appeal, that nineteenth-century transnational antislavery literature developed into.

Motifs of Antislavery: The Slave’s Lot

From Aphra Behn’s novella Oroonoko, or the Royal Slave onwards (1688), antislavery literary motifs slowly pervaded Western popular culture (Seeber Reference Seeber1936; Sypher Reference Sypher1942; Ferguson Reference Ferguson1992). The reasons for their popularity were manifold. Léon-François Hoffman, in his pathbreaking critical study of the literary figure of the ‘nègre romantique’, has explained the theme’s popularity through its wide potential for different significations: stories of slavery appealed to the sentimental because of their tragic accounts of victimisation and injustice, to the dreamers because of their exotic locale, and to the romantic because of the characters’ racialised association with extreme pathos (1973, 218–219; see also Chalaye et al. Reference Chalaye2012). Colonial slavery was made to serve as a metaphor for various Enlightenment anxieties, ranging from the nature of personal freedom and the threat of revolution, to the bewildering power of global commerce.Footnote 16 The subject also held particular charm for the literature of sensibility and for the gothic penchant of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.Footnote 17 One factor in this was that, particularly after the Saint-Domingue revolt, the theme lent itself to depictions of grotesque physical and psychological violence, as in Johann Gottfried Herder’s ‘Neger-Idyllen’ (1797) and William Blake’s illustrations for John Gabriel Stedman’s The Narrative of a Five Years Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Suriname (1796).Footnote 18

Some plots, particularly those of Oroonoko’s and Ziméo’s (1769) slave revolts, and the tragic love story of Inkle and Yarico (first printed in 1658), were recycled and adapted across poetic, prose, and theatrical works, ultimately becoming ‘founding legends of anti-slavery’ (Waters Reference Waters2007, 33; Absilis 2022, 116–117). Theatre was a powerful populariser, as plays such as Thomas Southerne’s Oroonoko (1695; French trans. 1745; German 1786), George Colman’s Inkle and Yarico (1787; German 1788; Dutch 1792), and August von Kotzebue’s Die Negersklaven (1796; English trans. 1796; Dutch 1796), found international audiences (see Sutherland Reference Sutherland2017; Adams Reference Adams2020; 2023; Oduro-Opuni Reference Oduro-Opuni2020). In the words of Sarah Adams, Jenna Gibbs, and Wendy Sutherland, however, this ‘ludic site of debate’ was equal parts the ‘arena of protest’ and the ‘venue for racist and imperialist exploitations’ (Adams, Gibbs, and Sutherland Reference Adams, Gibbs and Sutherland2023, 4).

Narrative prose often professed the facticity of the abject scenes described as much as their entertainment value, as signalled by the title of Johann Ernst Kolb’s collection Erzählungen von den Sitten und Schicksalen der Negersklaven, eine rührende Lentür Menschen guter Art (Narratives of the Customs and Fates of the Negro Slaves: Touching Reading for Kind-Hearted People, 1789), which included, for instance, a German version of Ziméo (Zantop Reference Zantop1997, 149–150). As in the case of Joseph La Vallée’s popular novel Un nègre comme il y a peu de blancs (1789), stories could quickly appear in multiple translations (Seeber Reference Seeber1936). Christopher Miller has suggested that, at least in France, in the early stages of the vogue for antislavery motifs, women dominated the market, while male writers like Victor Hugo, Prosper Mérimée, and Eugène Sue later came to replace them, marking a broad genre shift from the sentimental with abolitionist overtones to the adventure tale (Miller Reference Miller2008, 175).

A preferred mode of antislavery protest was poetry. Especially notable was the fecund, continuous production of abolitionist verse to fill Anglo-American antislavery periodicals like Garrison’s Liberator and Maria Chapman’s Liberty Bell (Carey Reference Carey2005, 73ff.; Pelaez Reference Pelaez2018). This medium was generally highly gendered in its subject matter and modes of address. Monica Pelaez estimates, for instance, that enslaved mothers were the most frequent subject of antebellum American antislavery verse (Pelaez Reference Pelaez2018, 156). Women’s prolific engagement in writing antislavery poetry, as well as short fiction, has been well established, and the specific sentimental appeals to feelings of sisterhood between writer, reader, and victim have drawn much critical commentary (e.g., Ferguson Reference Ferguson1992; Kadish Reference Kadish2012, Wiegmink Reference Wiegmink2022, 128ff.). The productivity of this mode of female authorship has led Karen Sánchez-Eppler to categorise it as part of the ‘female handiwork, refashioned for political, didactic, and pecuniary purposes’, along with women’s sewing and embroidering for antislavery bazaars (Sánchez-Eppler Reference Sánchez-Eppler1993, 24). The genre found lasting transnational popularity. In 1823, both the Société de la morale chrétienne and the Académie française held literary competitions for contributions around the theme of the abolition of the slave trade, suggesting the genre’s simultaneous popular, artistic, and reform interest (Daget Reference Daget1971, 44; Debbasch Reference Debbasch1991, Hoffman 2013 [1973], 222; McKelvey Reference McKelvey2021). It was also quite formalised, as indicated by the fact that the vast majority of poetic depictions of slavery were critical of the institution – pro-slavery poetry is scarce, despite the vehement propagandistic efforts of planters.Footnote 19

Arguably the most impactful and well-travelled antislavery materials were visual. Iconic images like the diagram and the Wedgewood medallion, ‘Am I Not a Man and a Brother’, or portraits of Frederick Douglass, who was acutely sensitive to the power of photography, produced startling effects on disparate readers, etching themselves into personal and collective memory (Trodd Reference Trodd2013; Brahm and Rosenhaft Reference Brahm, Rosenhaft, Brahm and Rosenhaft2016, 1–3; Köhler Reference Köhler2019, 49). A testament to the agency of these travelling images is the effect of a version of the Wedgewood medallion on early German abolitionist Therese Huber. It is not clear how the object reached her, but years later, in a letter to Henri Grégoire, she vividly described laying eyes on it, calling it the moment ‘the idea of the injustices which the black peoples were suffering struck me for the first time’ (Lentz Reference Lentz, Brahm and Rosenhaft2016, 187). This iconic image, too, reworked classical models to heighten its effect (Hamilton Reference Hamilton2013).

Across the various media, the boundaries between factual and fictional treatments of slavery were structurally blurred, contributing to the mutual inflection of sentimental antislavery literature and political discourse (Carey Reference Carey2005, 144ff.). Stressing the veracity of the depictions, as seen, for instance, in the poetry submissions to the Académie in 1823 (Debbasch Reference Debbasch1991, 335), became a commonplace of antislavery literature. The conflation between general antislavery literature and abolitionist argument can in part be attributed to the popular sentimental Anglo-American model of abolition, which conceptualised raising awareness as its main component, rather than successful organisation or parliamentary action. As George Boulukos explains, this model had the fuzzying effect of ‘rendering insignificant the difference between official abolitionism […] and emancipationist or even ameliorationist views, by defining any text that reveals the truth of slaves suffering as drawing attention to slavery and thus contributing to the humane cause of abolitionism’ (1999, 29).

Authors also frequently incorporated intertextual references to prove their assertions but also to invite readers to continue their reading and consider the ethical ramifications of their literary consumption. This characteristic was present from the start. Thomas Day’s The Dying Negro (1773), considered the ‘first significant piece of verse propaganda directed explicitly against the English slave systems’ (Wood Reference Wood2003, 36), contained several footnotes referencing well-known travel writing on West Africa – and in turn, the poem was cited in The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano (1794). Sophie Doin’s fictional antislavery novel La famille noire (1825), to give a Continental example, included a series of notes assuring readers of the factuality of her descriptions and directing them to further reading, such as the French translation of Thomas Clarkson’s The Cries of Africa (1822). August von Kotzebue’s play referred audiences to William Wilberforce (Oduro-Opuni Reference Oduro-Opuni2019, 244ff.). In the foreword to her poetry collection, Schaduwbeelden uit Suriname (Shadow Play from Suriname), Dutch poet Anna Ampt mentioned that she was inspired by the influential Dutch treatise Slaven en vrijen onder de Nederlandsche wet (Slaves and Freemen under Dutch Law, 1854) – providing readers with more material, but also making sure to exempt her work from any accusations of ‘Uncle Tom Mania’.

The blurring of boundaries also happened in the other direction. Grégoire’s study of black achievement, De la littérature des nègres, is a case in point. The chapter on the moral qualities of Africans takes Oroonoko as a case study, expressing regrets that Aphra Behn had chosen to tell the story of this ‘new Spartacus’ in a novelistic format.Footnote 20 In the same vein, Thomas Clarkson’s history of the abolition movement counted many literary voices among precursors of organised abolitionism (Boulukos Reference Boulukos and Ahern2013, 23ff.).

This blurring of fact and fiction lent the broad spectrum of antislavery discourse special affective impact. It also very successfully promoted a set of stereotypes about Africans and the enslaved which scholars have amply documented. Building on the work of Wylie Sypher (Reference Sypher1942) and Leo d’Anjou (Reference D’Anjou1996), Srividya Swaminathan suggests two dominant central figures of antislavery literature: the noble resistant slave, who would die rather than submit and thus meets a tragic end; and the helpless creature crushed under the weight of enslavement (2009, 105). Both figures recurred across sentimental antislavery poetry, fiction, and abolitionist image production (Wood Reference Wood2000; Boulukos Reference Boulukos2008; Libby Reference Libby, Childs and Libby2014; Cutter Reference Cutter2017). The powerless, pleading slave became a key motif of popular sentimental antislavery production following the Saint-Domingue uprising, as it was a palliative for fears of slave insurrection or even retaliation, which news coverage of the event had spread among wide audiences (Wood Reference Wood2003, xivff.; Boulukos Reference Boulukos2008; Little Reference Little2008). Highlighting the innocence and helplessness of its subjects, sentimental antislavery works tapped into religious narratives of the virtue of benevolence towards the meek and steered away from the story of ‘Black Jacobins’ (James Reference James1938; Drescher Reference Drescher2009, 120ff.; Wood Reference Wood2010, 51ff.). It was also one of the motifs through which sentimental literature, as Ellis puts it, was able to avoid implications too radical, and could let its argument ‘run aground on the shoals of the pathetic and little; that category of the sentimentally apotropaic which voyeuristically focuses on the powerless resigned to powerlessness’ (2004, 128).Footnote 21 In this frame, emancipation was graciously bestowed, rather than boldly taken (Davis Reference Davis1984; Yellin Reference Yellin1989; Wood Reference Wood2010).

Besides purveying specific behavioural scripts for the enslaved, abolitionist materials also consistently orbited the scenes of abject violence that the slave trade and colonial slavery produced. Slave markets, the Middle Passage, dog chases, separations of women and children, corporal punishment, and, in hushed formulations, the sexual abuse of enslaved women were frequent topics of antislavery discourse.Footnote 22 These scenes were designed to appeal to sympathy, but also often to showcase the corrupting influence of the institution, seducing slave owners to act sadistically and allowing onlookers to stand idly by, dulling their sense of morality. The proliferation of ‘scenes of subjection’ in antislavery discourse was a double-edged sword, as, in their cultivation of public antipathy to slavery, they patronised, dehumanised, and could even perpetuate the terrorisation of the enslaved (Hartman Reference Hartman1997; Wood Reference Wood2002; 2010). The popularisation and new coinage in European languages of terms like slave-driver, Sklavenhalter, and slavenhouder during the long nineteenth century suggests that the representation of the many forms of violence enslaved persons were subjected to in a limited set of melodramatic cultural scripts also sedimented widely in language.Footnote 23

It is important to note that the nineteenth-century genre of slave narratives, written or dictated by formerly enslaved people themselves, had the potential to disrupt these overpowering narratives. Frederick Douglass’ first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1851 [1845]; Dutch trans. 1846; French 1848), for instance, was not only a testament to his own active resistance, but also contained powerful critiques of nineteenth-century lay conceptions of the psychology of the enslaved. Examples of this resistance are found in his analysis of what to many of his contemporaries seemed to be the ‘rude and apparently incoherent’ singing of the enslaved, which he presented as a moving and meaningful expression of suffering and resistance against slavery (Douglass 1851, 19ff.); and his analysis of the slaveholders’ practice of ‘keeping down the spirit of insurrection’ by encouraging the drunkenness of the workers on their plantations on holidays, making ‘the holidays […] part and parcel of the gross fraud, wrong and inhumanity of slavery’ (Douglass 1851, 69ff.). Though some slave narratives were translated into European languages, their circulation remained limited and their reception was coloured by the cultural preconceptions which attended their status as ‘foreign’ objects (Huisman Reference Huisman2015; ‘Frederick Douglass Translations’ 2019; Roy Reference Roy2019). A case in point is the fact that even though Frederick Douglass was the most well-known African American orator, the most popular slave narrative in Europe was The Life of Josiah Henson (Swedish: 1877, 1877; Danish 1877; Welsh 1877; Dutch 1878; French 1878; German 1878). Henson’s narrative had special appeal for European publishers because of its religious thematic of providential deliverance, and because of his association with Stowe’s Uncle Tom (Huisman Reference Huisman2015, 86ff.; ‘Frederick Douglass Translations’ 2019). There are no known nineteenth-century translations of women’s narratives such as The History of Mary Prince: A West Indian Slave (1831), which raised considerable discussion in Britain, or Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861).Footnote 24

Memories of Antislavery: A Model Movement

As the reception of slave narratives indicates, antislavery culture in Continental Europe was on the whole more monolithic than in the Anglo-American sphere. The highly stylised, limited repertoire of black characters was designed to elicit particular affective responses and to make the idea of abolition palatable and non-threatening. Over time, stereotyped depictions of the enslaved worked in tandem with the logic of the dominant understanding of the abolition movement itself, which, despite its limited footprint, came to be remembered with similar verve as in the UK and the US. As the examples of Phule and Jin indicate, abolition came to be internationally venerated as, for nineteenth-century reformists, that most eminently usable of pasts: a first major moral achievement driven by public action. Abolition became a precedent for revolution driven by sentiment, and even by feminine intervention. These latter aspects were, naturally, particularly salient for later women’s rights advocates. The triumphalist narrative of the course of antislavery was at odds with history – major setbacks to the movement, such as the backlash against the Saint-Domingue uprising; bitter internal strife over the role played by women or what relationship to maintain to national politics; and key ideological differences, such as those between gradualists and immediatists, seemed by and large forgotten overnight.

The moral significance of abolition was exultantly asserted soon after the successes of antislavery in the nineteenth century (Davis Reference Davis1984, 107ff.; Schmidt Reference Schmidt1999; 2006; Wood Reference Wood2010; see also Chapter 2). After 1833, the ‘deceptive model’ of British abolition came to be internationally celebrated by reformers as a moral victory of global significance (Davis Reference Davis1984, 168). An impression of the tone with which prominent liberals welcomed the development is this comment by Alexis de Tocqueville, who hailed it as a victory of Christian faith:

We have seen something absolutely without precedent in history – servitude abolished, not by the desperate effort of the slave, but by the enlightened will of the master; not gradually, slowly, through successive transformations which by means of serfdom led insensibly towards liberty; not by successive changes of mores modified by beliefs, but completely and instantly, more than a million men simultaneously passed from the extremity of servitude to complete independence, or better said, from death to life. What Christianity itself did over a number of centuries has been accomplished in a few years. If you pore over the histories of all peoples, I doubt that you will find anything more extraordinary or more beautiful.

In addition to the appeal of Christian eschatological readings, for nineteenth-century liberals the success particularly of the British abolition movement seemed to prove the power of public opinion, or, even more reassuringly, that the evolution of ‘public virtue and enlightenment could keep pace with material advance’ (Davis Reference Davis1984, 109).

This dominant narrative of moral victory was closely connected to the veneration of the model of a lone, uncompromising, but ultimately visionary antislavery hero, epitomised by American figures like Garrison and John Brown. Andrew Delbanco has termed this vision of social reform the ‘abolitionist imagination’, identifying an influential broader understanding of the figure of the abolitionist as ‘not a member of this or that party but […] someone who identifies a heinous evil and wants to eradicate it – not tomorrow, not next year, but now’ (Delbanco Reference Delbanco2012, 23). The charismatic leadership and rhetoric of the contentious American abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison impressed reformers across the anglophone world and Europe from the 1830s onwards (Blackett Reference Blackett and Stewart2008; Morgan Reference Morgan, Mulligan and Bric2013; McDaniel Reference McDaniel2013). Harriet Martineau’s influential appraisal identified him as the ‘master-mind’ of abolitionism, who inaugurated a ‘martyr age’ in the United States when he transformed the antislavery movement from its dubious origins in the Colonization Society into ‘a body of persons who are living by faith’ – different in kind from any ‘party of Reformers contending against a particular social abuse’ (1839; see also Mayer Reference Mayer2008, 209). Garrison’s moral suasion proved an enduring paradigm for reform characterised by independence, moral perfectionism, self-sacrifice, consistency, and uncompromising, relentless outspokenness (Delbanco Reference Delbanco2012, 23; Harrold Reference Harrold2004; Blight Reference Blight and Stewart2008; Santana Reference Santana2016). Even the fact that Garrison was lampooned and vilified by the general public could take on positive significance for similarly beleaguered groups, such as certain former Saint-Simonians in Paris (as Chapter 3 will discuss). Jin’s quote at the opening of this chapter particularly attests to the wide reach of this imaginative figure, who serves as the ultimate model of the vindication of conscience.

The conception of antislavery as a victory of public moral conscience depended on the structural forgetting of the insurrectionist emancipationism of the enslaved themselves, which antislavery literature encouraged.Footnote 25 Instead of this history, the story of the surge of public sentiment under the spirited leadership of white abolitionists was remembered – as the present study affirms time and time again (Schmidt Reference Schmidt1999; 2006; Wood Reference Wood2010). As a socialist French journal summarised, ‘The English people, religious societies, women, carried away by a generous and truly Christian spirit, wanted the emancipation of black slaves. The leaders of the aristocracy, in this question, had their hand forced.’Footnote 26

The symbolic importance of slavery and its abolition retroactively imbued the cultural materials of the antislavery campaign with a halo of the progress of justice and possibility of social change. Chapman’s discussion of Harriet Martineau’s authorship lays bare the process of canon formation of antislavery texts that took place among reformers, even decades later:

I did not build so much as others upon her having written the best anti-slavery tale. It would not follow because Mrs. Behn and Steele and the Duchess de Duras were equal to the conception of ‘Orinoko’, ‘Inkle and Yarico’, and ‘Ourika’, that they could be true to human nature, under the severest ordeal […] But the writer of ‘the Scott papers’, the true painter of woman, the exalter and consoler of poverty, – no, I never could doubt that she must eventually see things as they really were.

Chapman’s reflections on what was the ‘best’ antislavery tale point to the prevalent remembrance of what Carey has identified as the ‘rhetoric of sensibility’ (2005, 18ff.) in antislavery argument. As Carey points out, as part of the late eighteenth-century campaign, traditionally different genres, from parliamentary speeches to first-hand testimonies and poetry, made recourse to the same set of tropes, appeals, and motifs, such as sentimental antislavery parables and heroes (see also Sypher Reference Sypher1942; Boulukos Reference Boulukos1999; Carey et al. Reference Carey2004). The frequent transgressions of traditional genre boundaries left its mark on the nineteenth-century memory of the campaign. The power of sentimental appeal was continuously underscored, and it was broadly understood as a combination of effective persuasion to what contemporaries called ‘metempsychosis’, the committed imaginative engagement with the suffering of the enslaved, and calling attention to the infinite regress of ironic counterpoints in antislavery literature, accusing the slaveholders themselves of debasement, ferocity, sinfulness, and criminality rather than, as slave interests were wont to do, the enslaved (Cima Reference Cima2017, 40ff.; Stevenson Reference Stevenson2020, 43ff.).

Chapman’s remarks also betray a retroactive feminisation, particularly among women’s reform circles, of the movement against slavery. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the figure of Harriet Beecher Stowe became the focal point for arguments about the importance of women’s influence in the movement and, more generally, for the importance of women’s voices for the national conscience. As this overview has shown, however, the association of antislavery fiction with female authorship went further back. Antislavery writing was an early medium for women’s discussion of political affairs and expressions of dissent. This was especially pronounced in French, American, and English literature, but Dutch and German examples also show this connection.Footnote 27 As the works discussed in the next chapter indicate, this literary genre also came to be remembered as an archive of a quiet but insistent questioning of the limits of women’s social role. Combined with the model of the lone, prophetic antislavery hero, memories of women’s antislavery yielded imaginings of proto-feminist antislavery heroines in the 1830s and 1840s, as Chapter 2 discusses in detail.

***