Introduction

On 25–26 June 1906, Duanfang, grand minister of Qing China and one of five delegates sent to Europe and the USA to study constitutional government, purchased 51 Egyptian antiquities. He thus created the first Egyptian collection in China and one of the earliest in East Asia, acquiring it just before the 1907 allocation of Egyptian antiquities to the University of Tokyo by the Egypt Exploration Fund (Stevenson Reference Stevenson2019: 134, fig. 3.5).

This pioneering act notwithstanding, Duanfang’s collection has received little attention in anglophone academia. Although Chinese scholars have translated some of the hieroglyphic inscriptions and explored their reception within Chinese society (Yan Reference Yan2006, Reference Yan2008, Reference Yan2021; Xue Reference Xue2023), these studies do not answer some vital questions: under what circumstance did Duanfang make his purchases? Were all the artefacts authentic? What roles did they play in Chinese perception of the ancient world and China’s own cultural practices? Recent scholarship manifests a growing interest in Chinese archaeological practices (e.g. Chang Reference Chang2001; Hein Reference Hein2016; Liu Reference Liu, Habu, Lape and Olsen2017; Storozum & Li Reference Storozum and Li2020) and in Chinese studies of ancient Egypt (Tian Reference Tian2021; Langer Reference Langer, Chan, Hui, Hui and Vafadari2023; Langer & Zhao Reference Langer and Zhao2025). This article contributes to the existing research, providing a synthesis of available literature and historical sources—including Duanfang’s Egyptian rubbings, published posthumously and now housed in the Princeton University Library, New Jersey, USA—to analyse the evolving understanding of Duanfang’s groundbreaking collection.

Late Qing antiquarianism

The motivation to purchase Egyptian antiquities, and Duanfang’s understanding of them, was rooted in Late Qing (1840–1912) antiquarianism. This intellectual trend originated in a shift from introspective Neo-Confucianism of the sixteenth century to a source-based philology in the eighteenth century. Verification of historical accounts and the study of ancient scripts were prioritised, and inscribed objects were venerated as vital materials and evidence. This was collectively known as kaozheng (search for evidence) scholarship (Elman Reference Elman2001: 90–93). The research of ancient inscriptions became an intellectual hobby and in the nineteenth century gave rise to collecting, connoisseurship and antiquarianism (Brown Reference Brown2011: 63). This shift to philology and textual studies also created a peak in jinshixue (the study of ancient bronze and stone), a discipline connected to the interpretations of ancient scripts and objects, and it is regarded as the precursor of Chinese archaeology (Trigger Reference Trigger2006: 74).

Many ancient Chinese inscriptions are not portable, so rubbings became the ideal method for recording them and facilitating discussions (Wu Reference Wu, Zeitlin, Liu and Widmer2003: 56). Rubbings were also collectable objects, with related connoisseurship developing over time. Hence, it is not surprising that when Chinese people encountered ancient Egyptian monuments in the late nineteenth century, they aspired to generating rubbings from them (Wang Reference Wang1982: 86; Zou Reference Zou1897: vol. 4, 17). Authentic Egyptian inscriptions and large objects, such as those purchased by Duanfang, and the rubbings produced from them remained rare (Ye Reference Ye1995: vol. 6, 14), and Duanfang was proud of the fact that the rubbings in his collection all corresponded to an original, authentic object (Duanfang Reference Duanfang1982: 1).

Duanfang’s purchases in Cairo

Objects in Duanfang’s Egyptian collection were likely purchased in Cairo, one of two main antiquities markets in early-1900s Egypt (the other being Luxor). The most dynamic markets of antiquity dealers were found north of the Ezbekiya Gardens and at Kafr El Haram (The Village of the Pyramid) close to the Great Pyramid, where some local villagers sold illegal finds (Hagen & Ryholt Reference Hagen and Ryholt2016: 65–76). In March 1905, the German Egyptologist Wilhelm Spiegelberg took a photograph of a stela at the shop of Michel Casira on the Haret el-Zahar, north of Ezbekiya Gardens (Spiegelberg Reference Spiegelberg1913: 79, 81). It depicted Emperor Tiberius making offerings to Horus and Isis, and the demotic inscription mentioned the name Parthenios (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Photograph of the Stela of Parthenios in 1905 (above; Spiegelberg Reference Spiegelberg1913: 81) and the photograph of its rubbings from Duanfang’s collection (below; Duanfang Reference Duanfang1912: 24). Height 564mm, width 386mm (figure courtesy of Princeton University Library PJ1521.A43).

Rubbings of this stela were identified among Duanfang’s collection, now in the National Library of China (Yan & Clarysse Reference Yan and Clarysse2006: 3, 7), as were rubbings of stela of KA-wD-anx, noted in the same shop in 1902 by Egyptologist Percy Newberry (Figure 2; Newberry Reference Newberry1912: 79, note 2). The inscription from a door jamb in Duanfang’s collection was published by French Egyptologist Émile Chassinat four years before it was purchased by Duanfang—it originated in Qau El Kabir, reaching Cairo around 1899 (Figure 3; Chassinat Reference Chassinat1901).

Figure 2. Photograph of the rubbing of the stela of KA-wD-anx (Duanfang Reference Duanfang1912: 2). Height 1175mm, width 531mm (figure courtesy of Princeton University Library PJ1521.A43).

Figure 3. Photograph of the rubbing of the jamb from El-Kabir (Duanfang Reference Duanfang1912: 9). Height 1433mm, width 322mm (figure courtesy of Princeton University Library PJ1521.A43).

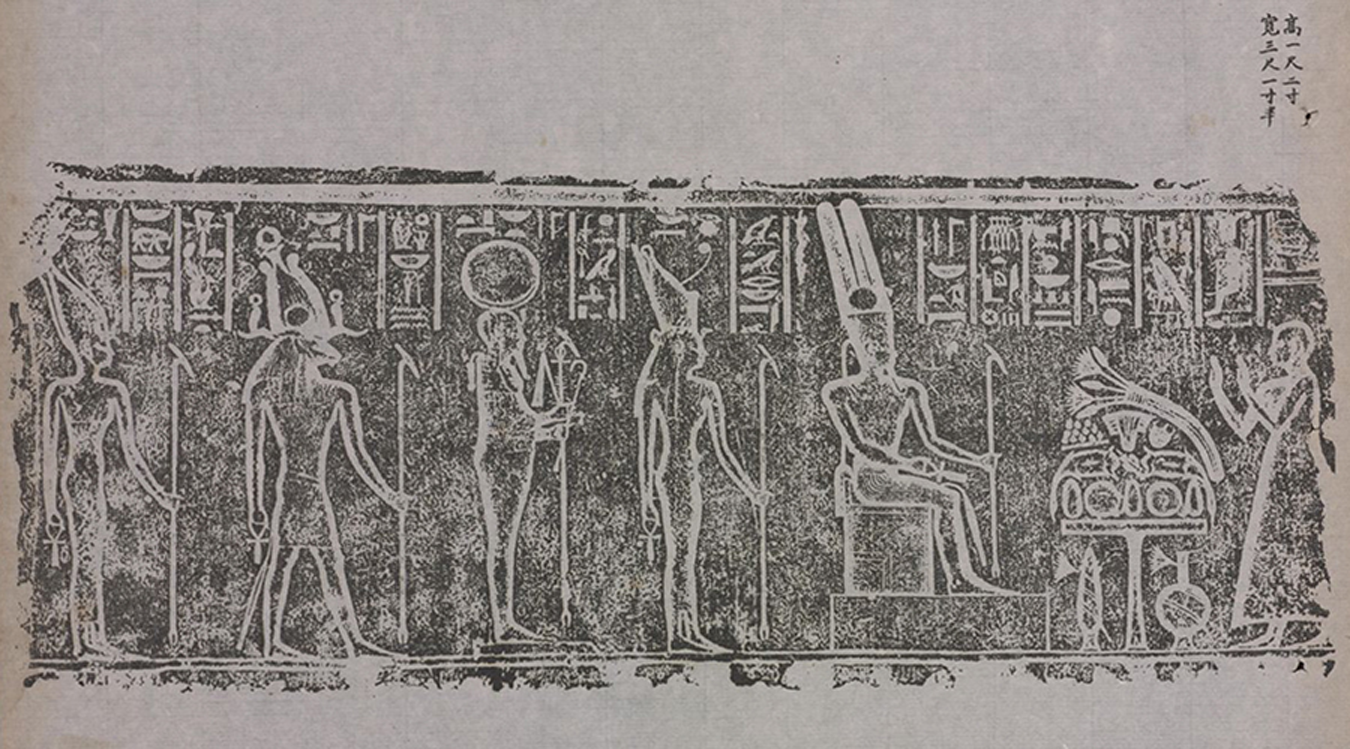

Some artefacts reveal a provenance from archaeological sites close to Cairo, such as Giza and Saqqara (see online supplementary material (OSM) Appendix 2), and may have been illicit finds. Artefacts from sites in Lower Egypt, such as Kafr Al Meqdam (Clarysse & Yan Reference Clarysse and Yan2006: 834; Reference Clarysse and Yan2007) and Qantir (Habachi Reference Habachi1969: 41) are also presented. Thus far, only one block that depicts Peteharpokrates (pAdi-Hr-pA-Xrd) worshipping Min and Khnum (Figure 4; Yan Reference Yan2006: 38) shows a clear southern connection to Luxor and Aswan, yet the exact provenance is unknown. A wooden coffin from Duanfang’s collection mentioned Thenu (tA-Hnw), daughter of Peteharpokrates, “chantress of Min of Akhmin” (Clarysse & Yan Reference Clarysse and Yan2006: 835; Yan & Clarysse Reference Yan and Clarysse2006: 4). If the father of Thenu was the same Peteharpokrates on the aforementioned block, then the provenance of the block could also be Akhmin. One stela of Inaroys was from Thebes (Yan & Clarysse Reference Yan and Clarysse2006: 6). As Luxor dealers sent their goods to Cairo for sale, Duanfang could have procured objects from Upper Egypt.

Figure 4. Photograph of the rubbing of the block depicting Peteharpokrates (Duanfang Reference Duanfang1912: 8). Height 1014mm, width 386mm (figure courtesy of Princeton University Library PJ1521.A43).

While most shops in Cairo were open for business during the daytime, the epigraph by Deng Bangshu, another member of the delegation, about one rubbing from the National Library of China implies that Duanfang also made purchases at night: “I visited … Cairo, and read stelae by the candlelight” (Yan Reference Yan2006: 39). In 1900, Egyptologists Hans Langer and Valdemar Schmidt also visited the storeroom of the dealer Soliman Abd es-Samad, located just a few minutes’ walk from Casira’s shop, at night and read inscriptions by candlelight (Hagen & Ryholt Reference Hagen and Ryholt2016: 53, 264).

Problems of ‘forgeries’

An intensive shopping trip in the dark left little time for careful examination, and it is likely that Duanfang purchased forgeries. But, for Duanfang’s collection, ‘forgery’ refers to both forgeries made for profit, and replicas made not for sale but for study. Forgeries were common in antique markets in early-twentieth-century Egypt; portable objects such as scarab seals and shabtis were newly made (Potter Reference Potter2022), while ancient statues were augmented with new inscriptions to raise their price (Dunham Reference Dunham1933; Cooney Reference Cooney1950: 11–13). Duanfang also made concrete replicas of his collection after returning to China and produced rubbings from these replicas. Such duplication was not malicious, but a practice deeply rooted in Chinese antiquarianism; yet Duanfang’s Egyptian rubbings became targets of forgery. Due to their popularity, dealers produced fake stelae and made rubbings from them for sale and, as the authenticity of Egyptian hieroglyphs was difficult to discern, these forgeries could easily fool buyers (Wang Reference Wang1934).

Although some unpublished, authentic inscriptions have been translated, the authenticity of at least 18 rubbings from Duanfang’s collection remains unexamined. Two inscriptions are unusual, indicating that either the inscribed objects or the inscriptions were forgeries. One is from a fragment of a lintel (Figure 5; Duanfang Reference Duanfang1912: 21). Inclusion of the title “Wab Priest (Pure one) in the Nekhen” refers to members of temple staff responsible for the upkeep of the temple’s daily activities. The title suggests a date in the early Fifth Dynasty (2494–2345 BC) (Nuzzolo Reference Nuzzolo2010: 309), yet the representation of ‘Nekhen’, the Sun Temple built by Userkaf, the first pharaoh of the Fifth Dynasty (reigned from 2494–2487 BC), is exceptional. Determinative signs depicting the temple are usually included in the name (Figure 6a; Jones Reference Jones2000: 127, 375, 528, 534–35, 841, 921; Bolshakov Reference Bolshakov2005: 214–17; van de Walle Reference van de Walle1977: 22) but are not present here. The epithet “who is in his mummy wrapping” for Anubis was from the Fourth (2613–2494 BC) to Fifth dynasties, but, unlike in this case, does not appear directly after the name ‘Anubis’ in the inscriptions from the burials of temple staff of Nekhen (Roeder Reference Roeder1913: 44–45, 60; Borchardt Reference Borchardt1937: 150–51; James Reference James1961: pl. XXII). Thus, the lintel was either an exceptional case or of doubtful authenticity.

Figure 5. Photograph of the original rubbing of the lintel of the Wab Priest of Ra in the Nekhen (above; Duanfang Reference Duanfang1912: 21) with a modern rendering of the hieroglyphs (below); the translation reads “an offering of the King gives, and an offering of Anubis, who is in [his (mummy) wrapping] … the Wab priest (the Pure one) of Ra, in the Nekhen, [priest] of Hathor”. Height 322mm, width 499mm (figure courtesy of Princeton University Library PJ1521.A43).

Figure 6. Hieroglyphic words and signs mentioned in this article: a) various forms of the term Nekhen in hieroglyphic writing (Jones Reference Jones2000: 127, 375); b) the vertical platform (variant of the Gardiner Sign List Aa11); c) the eye (Gardiner Sign List D4) (figure by author).

A lid of a cylindrical stone vase bears an incomplete inscription (Figure 7; Duanfang Reference Duanfang1912: 22; Wang Reference Wang1936: 518–19; Tian Reference Tian and Langer2017: 177, fig. 1). The final six signs form an unsuccessful attempt to write an epithet, such as “one who praised his father” or “whom his lord favours” (Jones Reference Jones2000: 658–60). The inscription also lacks the owner’s name, and the vertical ‘platform’ sign (Figure 6b) inserted after the title “the acquaintance of the king” is clumsy and arguably unnecessary.

Figure 7. Photograph of rubbing of the flat lid (above; Duanfang Reference Duanfang1912: 22) with a modern rendering of the hieroglyphs (below); the translation reads “the acquaintance of the king, beloved of his lord”. Height 129mm, width 129mm (figure courtesy of Princeton University Library PJ1521.A43).

Unlike these potential forgeries for sale, Duanfang’s replicas were created to facilitate the production of rubbings without damaging the originals because the pounding involved during the process was destructive. Chinese rubbing production is a multi-step process. First, the surface of the inscription is cleaned. A thin sheet of paper is then affixed to it using a water-based adhesive. The damp paper is gently pounded so that it conforms to the depressions. An ink pad is then used to apply pigment to the surface—also by repeated pounding. Finally, the paper is peeled off, leaving a high-contrast impression of the carved text (Wu Reference Wu, Zeitlin, Liu and Widmer2003: 46–47). This practice was common in Chinese antiquarianism, where replication was a form of reincarnation. For example, the Stela of Mount Hua (Shaanxi, north-west China) was erected in 165 BC but destroyed in an earthquake in AD 1555. Rubbings had been collected from the stela for generations, and the scholar Ruan Yuan fashioned replicas from these rubbings in 1811. A replica stela was erected in the original location and was venerated as the original (Wu Reference Wu, Zeitlin, Liu and Widmer2003: 41–45). Hence, artefacts could be reincarnated in generations of rubbings and replicas, long after the original had vanished. It is difficult to assign the labels ‘authentic’ and ‘forgery’ to Ruan’s replicas; Chinese antiquarianism’s approach to ‘cultural authenticity’ is different from that of European culture (Scott Reference Scott, Hein and Foster2023: 23).

The Chinese acceptance of rubbings as authentic inscriptions aligns with previous findings that authenticity was created and renegotiated by different groups (Holtorf & Schadla-Hall Reference Holtorf and Schadla-Hall1999: 238). Moreover, it was considered that rubbings were able to capture the aura of the original, thereby validating their authenticity. The example of the Mount Hua stela illustrates the extended agency of original artefacts through replication (Foster & Curtis Reference Foster and Curtis2016: 129–31; Foster & Jones Reference Foster and Jones2019: 13). That Duanfang’s replicas were produced solely to facilitate the rubbing-making—rather than for display or commercial sale (Brulotte Reference Brulotte2012: 85)— also underscores cultural variation in the use and purpose of replicas. Finally, the practice of producing rubbings out of a replica presents a unique case of replicas as “copies of copies” (Foster & Curtis Reference Foster and Curtis2016: 132).

The blurred line between original and replica made Duanfang’s replicas intellectually and culturally acceptable. Duanfang also followed a recent precedent. In 1889, Zhang Yinhuan, the ambassador to the USA, sent a gypsum replica of the Canopus Decree to Pan Zuyin, the grand councillor and collector. The original was a decree of Ptolemy III in 238 BC, inscribed on multiple stelae, but Pan’s replica was made from an 1876 cast of the original, now in the Smithsonian Museum (USNM Number A24300-0). Zhang warned Pan to be gentle with the fragile gypsum when producing rubbings (Pan Reference Pan2019: 33; Tian Reference Tian2021: 71–72). And the gypsum was initially mistaken for ‘cement’ (Ye Reference Ye1979: 11 897). The warning and misidentification may have influenced Duanfang’s unusual choice of concrete as the, much more durable, material for replicas. The choice of concrete also reflects profound differences between perceptions of replicas in China and the West. Concrete replicas prioritise durability at the expense of faithfulness to the original in colour and material. Moreover, a comparison of the rubbings made from the original sarcophagus of Esnehemaoui from Qau El Kabir and rubbings made from Sarcophagus’ concrete replica reveals that the latter omits a substantial number of cracks on the original (Xue Reference Xue2023: fig. 1b & c). The concrete replicas of the St John’s Cross at Iona suffer from the same limitations, lacking traces of ageing or patina (Foster & Jones Reference Foster and Jones2019: 10). However, none of these limitations elicited complaints from Chinese collectors, for whom the material was of lesser importance than the presence of the artefact and inscriptions. For Duanfang, the replicas were not intended for display but for producing rubbings, meaning their colour was of minimal concern.

Using concrete also impaired the faithfulness of replica inscriptions, which was interpreted by later collectors as a loss of the original’s aura (Wang Reference Wang2005: 1889). The concrete replica of Esnehemaoui’s sarcophagus presented many cracks as hieroglyphic signs, while all the eye signs lost their pupils (Figure 6c). No information survives about how Duanfang’s replicas were produced, but they were probably cast from master models imitating the originals, in a method similar to the production of the concrete replicas of the St John’s Cross (Foster & Jones Reference Foster and Jones2020: 122). Thus, unlike plaster casts or squeezes, which were cast directly from the originals, these replicas were cast from an intermediate replica.

Duanfang’s rubbing practices

Duanfang’s replications, despite being called ‘replica’, do not always record the originals faithfully. His rubbings prioritised objects’ inscriptions over the shape. This modus operandi manifests itself in three rubbings of the sarcophagus of Esnehemaoui now in the National Library of China. One includes the entire sarcophagus while the other two present only the inscriptions—one taken from the original and the other from a replica (Li Reference Li2004: 118; Xue Reference Xue2023: fig. 1a–c). Moreover, later collectors spotted the differences between the original and Duanfang’s replica complaining about the clumsiness of its makers (Wang Reference Wang2005: 1889). Yet, sometimes Duanfang endeavoured to present a holistic image of the artefacts. The rubbings of the statue of Jbttj include the back pillar and a full three-dimensional image, known as a composite rubbing (Xue Reference Xue2023: 33, fig. 7). Traditional rubbing presented distorted images. To remedy this, in the early nineteenth-century artisans painstakingly produced rubbings from different parts of objects and assembled them into one (Brown Reference Brown2011: 65–66; Starr Reference Starr2018: 128–44). Thus, Duanfang must have commissioned skilled artisans to depict the statue as faithfully as possible.

Duanfang’s preference for inscriptions reflects the persistent focus on texts among the kaozheng scholars and it shaped interest in Egyptian writings in late-nineteenth-century China (see also Monteith et al. Reference Monteith, Tang, Chen, Tang, Liu, He and Yu2025). This tendency continues to influence Chinese Egyptology and Egyptian archaeology. Furthermore, rubbings influenced Duanfang’s visual understanding of Egyptian antiquity; by translating Egyptian antiquities into black-and-white images, Duanfang achieved a visual affinity between Egyptian imagery and reliefs from the burial chambers of Han Dynasty China. Thus, the unfamiliar Egyptian antiquity could be appreciated within the Chinese contexts. Han reliefs had been captured as rubbings for centuries, and were also collected by Duanfang. In colophons (added to margins of the rubbings to give information about them) of Egyptian rubbings, he commented that they are similar to rubbings of a Han dynasty shitang (食堂), a term which was previously translated as ‘canteen’ or ‘feast’ (Yan & Clarysse Reference Yan and Clarysse2006: 6; Dong Reference Dong2015: 73, fig. 1). This translation follows the modern Chinese usage of the term, overlooking its architectural and ritual connotations in a historical context. Drawing on study of Han ritual architecture (Jiang Reference Jiang1983: 746), I propose that ‘Offering Hall’ more accurately reflects the term’s original function. Art historians also noticed that rubbings transformed the once refined and vivacious Han style into something austere, thus heightening the antiquity of the images (Figure 8; Ling & Zhu Reference Ling and Zhu2013: 14). Similarly, Duanfang stated that Egyptian inscriptions were “five thousand years old” (Figure 9; Xue Reference Xue2023: fig. 1 b & c); hence, rubbings—by visually conveying age through their aesthetic qualities and connection to Han images—were the most suitable media to reproduce such antiquity.

Figure 8. Photograph of the rubbing of “Wu Family Shrines” pictorial stones depicting mythological and historical figures, Shandong Province, China, mid-second century (stone); the rubbing was produced during the late nineteenth–early twentieth century (figure courtesy of Princeton University Art Museum y1957-140 e).

Figure 9. Photograph of the cover of Duanfang’s rubbing collection. The Chinese title on the right says “5000-year-old ancient Egyptian inscriptions”. The rubbing on the left is the stela of Anx-bA-Dd.t (?), depicting him and his family making offering to Osiris and Isis. Height 1030mm, width 515mm (figure courtesy of Princeton University Library PJ1521.A43).

Duanfang’s collection after Qing

Duanfang’s sudden death and the chaos after the fall of the Qing Empire in 1911 saw his Egyptian collection dispersed, leaving little trace in the written record. Some rubbings were reprinted by Youzheng Publish house in Shanghai around 1912 (Xue Reference Xue2023: 24, note 1), and this volume was later auctioned and, without detailed record, reached Princeton University Library. In 1914, Duangfang’s son Jixian offered more than 1300 pieces of Duanfang’s collection, including Egyptian antiquities, to the newly founded Republic of China for 2 000 000 silver yuan, thus converting this private collection to a public one. By 1916, a presidential decree approved this purchase. But later, Jixian nullified the purchase (Second Historical Archives of China 1995: 3–5). Duanfang’s rubbings were still available in markets because he had gifted many to friends and guests. These were sought after by the celebrated painter Li Kuchan and the scholar Wang Xiang. After acquiring the list of Duanfang’s Egyptian artefacts proposed to be nationalised, Li searched for rubbings and antiquities within it (Li Reference Li1994: 25; see OSM Appendix 1). Wang frequented the Liulichang market, the centre of Beijing antique dealing, in search of these rubbings (see OSM Appendix 2) and composed poems about them in the 1930s (Wang Reference Wang2005: 2517–18). Some rubbings went abroad: one was purchased by Korean artist Li Hanbok in Beijing in 1938 and is now in the Boston Museum of Fine Art, another two were gifted by Duanfang in 1906 to Arthur Moore, Commander-in-Chief of China Station, and are now in Maidstone Museum, England (see OSM Appendix 1). The Qau El-Kabir jamb was acquired by the secretary at the German Legation in Beijing, Mu Xuexun, who agreed to display it at the Meridian Gate outside the Forbidden City for nine days in May 1926 (see OSM Appendix 2).

The early twentieth century also saw the arrival of modern archaeology in China; for example, Johan Gunnar Andersson’s excavation of Yangshao sites in northern China in 1921. But China’s early archaeologists paid little attention to Duanfang’s Egyptian collection as their work focused on prehistoric and early China. Collectors were not satisfied with owning Egyptian texts without translation. In the same year that Andersson started his excavation, Mu Xuexun mistaking the Qau El-Kabir jamb for a sarcophagus lid, asked Barry O’Toole from the Catholic University of Peking for a translation. O’Toole contacted Egyptologist Georges Daressy for a translation from hieroglyphs to French, then translated it into English himself (Mu et al. Reference Mu, Li and O’Toole1922).

As an eminent collector and important historical figure (see Figure 10), Duanfang and his Egyptian collections were immortalised in popular narratives. The carvings of “an Egyptian king and queen” became a significant curio (Xu Reference Xu1917: vol. 34, 343); while his rubbings became show-pieces for good taste among the literati (Chen Reference Chen1922: 58).

Figure 10. Photograph (date unknown) of Duanfang (seventh from the left) and colleagues, with an Altar Set from the late eleventh century BC (formally Duanfang’s collection, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art 24.72.1–.14) (figure courtesy of National Museum of Asian Art Archives, Smithsonian Institution, FSA_A2004.03. Photograph by Laurence Sickman).

The 1920s and 1930s witnessed the rise of Chinese urban culture. In port cities such as Shanghai, magazines catered for the urban appetite for the latest cultural topics (Lee Reference Lee1999: 67; Bevan Reference Bevan2020: 202). In 1930, Shanghai Cartoon published a rubbing of a statue from Duanfang’s collection; just a page away, there were Chinese men in tuxedos (Shanghai Sketch Society 1930). In 1934, Nanking Daily published an article by Wang Xiu, who regretted not having purchased a hieroglyphic dictionary for translating the Egyptian inscription of the collection (Wang Reference Wang1934). On the Lunar New Year’s Eve of 1938, Wang Xiang hung four rubbings over flowers, praising this exotic mix “enriched the joyful atmosphere” (Wang Reference Wang2005: 1921). These practices gave Duanfang’s rubbings new meanings. They are no longer records of a collection but part of a bricolage of modern and traditional lifestyles.

Duanfang’s rubbings gained political meaning after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949. In 1956, the Nasser government of Egypt recognised the PRC and, in response, PRC sent Chinese books from the National Library of China to Al-Azhar University, along with 12 Egyptian rubbings from Duanfang’s collection (People’s Daily 1956). Fifty-one years after Duanfang’s visit, the rubbings of some of his purchases returned home as a symbol of friendship (Qian Reference Qian1981). The cultural exchange also brought the Egyptologist Mustafa El-Amir to China in 1956. During his stay, he examined Duanfang’s eight shabtis in Peking University (El-Amir Reference El-Amir1958). But the turmoil of subsequent political movements meant many of the rubbings were either lost or destroyed (Li Reference Li1994: 26). Replicas survived in the storeroom of the Forbidden City, National Museum and Peking University, and were rediscovered in the early 2000s (Yan Reference Yan2006: 35). The sarcophagus of Thenu, its replica and the surviving replicas of Egyptian inscriptions were displayed in rooms outside the Gate of Uprightness, south of the Forbidden City, from 2005 to 2011, managed by private companies.

Conclusion

Although Duanfang’s Egyptian collection was dispersed more than a century ago, this study offers a holistic view of its background by examining historical materials from China and abroad. The artefacts were almost exclusively purchased in Cairo through an extensive network of antiquity markets and, within just 24 hours, an impressive quantity was acquired but some pieces might be forgeries. Once in China, the artefacts were reproduced as concrete replicas and rubbings were taken. In the twentieth century, these rubbings outlasted the originals, influencing Chinese perceptions of ancient Egypt and relations with modern Egypt. This study enhances our understanding of Duanfang’s collection by situating it within the broader archaeological and heritage contexts, presenting a new perspective on the current state and international impact of the collection. By tracking Duanfang’s rubbings globally, museums can better contextualise them and identify the original artefacts. For the first time, problematic inscriptions are re-evaluated, suggesting possible forgeries, a matter that has not been thoroughly investigated before. This study also highlights previously overlooked materials and offers a different translation of shitang—proposing ‘Offering Hall’ rather than earlier renderings such as ‘canteen’—by situating the term within its historical and architectural context, rather than its modern usage.

By incorporating non-Western perspectives on Egyptian artefacts, this study contributes towards decentralising the Eurocentrism in archaeological theory. Duanfang’s collections demonstrate that historical interest in ancient Egypt was not confined to Europe; the value and interpretation of Egyptian artefacts have also been influenced by non-European traditions. Yet this interest remained peripheral even after the emergence of modern Chinese archaeology. The study of Egyptian artefacts differed from early-twentieth-century scientific Egyptian archaeology: replicas were considered valid study materials (unlike the European concept of authenticity) and interpretations were framed within Chinese art history.

This study provides a case for the growing interest in replicas of archaeological artefacts. It illustrates several key insights from previous studies. Authenticity is socially constructed and continually negotiated (Holtorf & Schadla-Hall Reference Holtorf and Schadla-Hall1999: 238), while the agency of objects can be extended across time through replication (Foster & Curtis Reference Foster and Curtis2016: 129–31; Foster & Jones Reference Foster and Jones2019: 13). Moreover, the meaning of artefacts shifts across regions, with Egyptian objects evolving from exotic curiosities to cultural capital and symbols of national friendship.

Acknowledgement

I am grateful to Professor Julia Lovell (School of Historical Studies, Birkbeck, University of London) for her invaluable assistance in proofreading this manuscript.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or from commercial and not-for-profit sectors.

Online supplementary material (OSM)

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.10098 and select the supplementary materials tab.