Introduction

The way political parties change their positions – and, in doing so, attract voters and shape policy debates – has been a central concern in political science. Scholars have not only tested various theories but also measured party positions in different ways. To date, however, few approaches have taken into serious consideration that parties campaign on multiple issues simultaneously that are of different importance to them. While concepts like issue ownership and the distinction between pragmatic and principled policy issues have been explored, they are based on prescriptions external to the party. Instead, we differentiate between parties’ ideological cores and their policy peripheries, examining how parties strategically use these areas when designing their campaigns. Thus, this article asks: How do parties adjust their positions and the distinctiveness of their policy stances across their ideological core and periphery?

This paper focuses on party positions and positional changes measured based on parties’ electoral programmes. We follow this tradition as these programmes, also called manifestos, are produced by political parties themselves at regular intervals and with relatively clear functions: communication to voters, competitors, and potential coalition partners, as well as to their own members and supporters (Budge et al. Reference Budge, Klingemann, Volkens, Bara and Tanenbaum2001; Volkens et al. Reference Volkens, Bara, Budge, McDonald and Klingemann2013). For our empirical analysis, we draw on the textual data provided by the Manifesto Project Corpus (Lehmann et al. Reference Lehmann, Franzmann, Al-Gaddooa, Burst, Ivanusch, Lewandowski, Regel, Riethmüller and Zehnter2024). Crucially, however, we depart from the common assumption that one manifesto is only one data point.

We build on the idea that parties’ manifestos are not homogeneous documents where all sentences have principally the same function. Instead, manifestos contain text that speaks to a party’s ideological core and text that is at their ideological periphery (Habersack Reference Habersack2025; Habersack and Werner Reference Habersack and Werner2023). The core defines the party’s fundamental identity and has particular importance for the party members’ identification with the organisation as well as the issue ownership and competence that voters ascribe to the party. Thus, the core contains the policies and positions that the party stands for and is, therefore, closely related to the party’s family denotation as Social Democratic, Conservative, Green, or Radical Right. At the same time, manifestos include text that is about policies at the party’s ideological periphery, which are policies not intricately linked to the party’s identity but that need covering because they are relevant for the specific society and state at the time.

Our main argument regarding the importance of distinguishing parties’ cores and peripheries builds on two seemingly contradictory arguments in the literature. On the one hand, parties need to update their policy positions in response to changing voter demands to remain relevant and maximise their electoral appeal (Downs Reference Downs1957). On the other hand, such change risks undermining the loyalty of their members and core supporters. Thus, it has been argued that parties need to change, albeit in a confined space (Budge et al. Reference Budge, Ezrow and McDonald2010). Building on this theory, we posit that parties can more flexibly adapt their ideological peripheries that are less central to their voter mobilisation, while they need to maintain a stable ideological core.

Building on this argument, we investigate how parties balance ideological stability and change across their core and periphery. Are parties more or less likely to shift their core positions compared to their periphery? Do certain types of parties respond differently, and under what conditions do they alter their profiles? Thus, beyond examining how parties distinguish themselves through their ideological core and periphery, we also analyse whether change is more likely to occur in one area than the other. We thereby aim to advance our understanding of what ‘party change’ actually entails and how it unfolds in electoral competition.

To empirically assess our theory, we analyse party manifestos from seventeen Western European countries (1946–2022) using the textual data provided by the Manifesto Project Corpus (Lehmann et al. Reference Lehmann, Franzmann, Al-Gaddooa, Burst, Ivanusch, Lewandowski, Regel, Riethmüller and Zehnter2024) with at least three time points. Drawing on the party family literature, we split each manifesto into its ideological core and periphery, treating them as separate documents. We then employ an XLM-RoBERTa-based language model (Burst et al. Reference Burst, Lehmann, Franzmann, Al-Gaddooa, Ivanusch, Regel, Riethmüller, Weßels and Zehnter2023) to retrieve the predicted probability of each quasi-sentence within these documents to be coded as each of the fifty-six Manifesto Project’s coding categories. For each manifesto section, we then derive its mean position in the policy space along the economic and cultural dimensions, which allows us to also determine its ideological extremity from the centre and positional changes between elections.

Our findings are threefold: first, parties take more extreme positions in their core compared to their periphery, a pattern that especially applies to niche parties. This confirms that cores function as ideological anchors that differentiate parties from their competitors. Second, parties are significantly more likely to change their positions in their periphery than in their core. This suggests that adaptation occurs primarily in non-core policy areas, where the risk of voter alienation is low. Third, electoral setbacks prompt parties to adopt more extreme peripheral positions but leave core positions largely unchanged. However, electoral fortunes, in general, do not lead to larger or smaller position shifts. This indicates that while electoral losses create some incentives for party policy shifts, parties remain reluctant to alter their core policy commitments altogether. Thus, our findings demonstrate that core and peripheral policy positions follow distinct political logics, challenging the notion that party platforms shift as a whole.

This novel distinction – and our finding that parties systematically differentiate between their ideological core and policy periphery – carries significant implications for the study of political parties and representation. It calls into question the validity of interpreting party shifts along a unified left–right dimension, suggests distinct causal mechanisms for changes in specific policy areas and for patterns of party–citizen congruence, and may help explain discrepancies among manifesto-based, expert-based, and citizen-based measures of party positions. Thus, incorporating the core–periphery distinction can enhance explanatory models across a range of research programmes central to the functioning of representative democracy.

The article proceeds as follows: in the next section, we review the literature on party change, expand on the idea that parties have different incentives to adapt with respect to their cores and their peripheries, and develop our hypotheses. We then outline our research design and empirical strategy before presenting our findings and testing our hypotheses. We conclude with broader implications for the study of party representation and future avenues of research.

Theory: The Strategic Role of the Ideological Core

The study of political parties’ position change has a long and extensive tradition (Downs Reference Downs1957). This interest in party positions is based on parties’ core function within modern representative democracies as they establish the link between citizens and the political decision-making process via elections (see, for example, Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1942). Parties’ programmatic offerings are thus central to the representative process given that they structure the policy choices for citizens and are the basis of parliamentary and governmental policy output. When parties change their programmatic offerings, they influence all parts of the representative chain.

Thus, theories on party competition and party behaviour often focus on where parties position themselves in the policy space and what factors encourage them to change these positions (Budge Reference Budge1994; Merrill and Grofman Reference Merrill and Grofman1999). Crucially, much of this literature draws on spatial theories of voting embedded in a rational choice framework. Accordingly, a voter supports a given party based on the perceived ‘proximity’ of their policy preferences to a party’s platform. Parties therefore position themselves in the policy space so as to minimise the distance to their voters and maximise their electoral appeal (Downs Reference Downs1957).

Building on this framework, research has explored the conditions under which mainstream actors respond to public opinion and shifts in voter preferences (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2004; Adams et al. Reference Adams, Haupt and Stoll2009; Romeijn Reference Romeijn2020). Existing empirical studies emphasise the influence of electoral competition (Abou-Chadi Reference Abou-Chadi2018; Abou-Chadi and Orlowski Reference Abou-Chadi and Orlowski2016) and volatility (Dassonneville Reference Dassonneville2018) on the need for parties to adjust their platforms to attract new voters. Observations of these adaptions reveal connections to broader trends in political competition, including the ‘rise of challenger parties’ (De Vries and Hobolt Reference De Vries and Sara2020). Notably, the emergence of green and radical right challenger parties has introduced a new socio-cultural dimension to political competition (Dassonneville et al. Reference Dassonneville, Hooghe and Marks2024; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006), prompting mainstream parties to revise their programmatic strategies. It appears that parties are willing to modify their policy profiles as circumstances evolve.

However, changing their programmatic offering also comes with a plethora of risks for parties. In particular, frequent adaptation of policy profiles risks undermining a party’s identity and credibility with voters (Downs Reference Downs1957, p. 122). Where radical shifts do occur, this often threatens to divide parties internally (Bardi et al. Reference Bardi, Bartolini and Trechsel2015; Mair Reference Mair, Goetz, Mair and Smith2013) and risks voter alienation (Adams and Somer-Topcu Reference Adams and Somer-Topcu2009; Van Spanje Reference Van Spanje2018). This is because parties are limited in their programmatic decisions by their activists, their established voter bases, and their target voters (Basu Reference Basu2020). Policy adaptation can therefore be regarded as a ‘desperate deed’ of parties from a position of electoral weakness (Schumacher and Van Kersbergen Reference Schumacher and Kersbergen2016; Van deWardt Reference van de Wardt2015), because it is inherently uncertain how well positional shifts will resonate. Hence, especially where the core of a party family is concerned (Mair and Mudde Reference Mair and Mudde1998), parties more likely opt for continuity over frequent adaptation.

Therefore, parties need to strike a fine balance between stability and change. To tackle this problem, it has been suggested that parties do not treat all of their positions the same when deciding on whether or not to change. This research has highlighted the roles of positional as well as salience shifts (Carmines and Stimson Reference Carmines, Stimson and Riker1993; Meguid Reference Meguid2008) and argues that parties face a constant choice between emphasising their ‘core’ policy issues and broadening their appeal by focusing on ‘peripheral’ ones, or in other words: ‘riding the wave’ (Wagner and Meyer Reference Wagner and Meyer2014). Instead, we propose that parties can keep stable ideological cores while adapting their peripheries at the same time.

Parties’ ideological cores, their backgrounds – such as conservatism, liberalism, or socialism – are the distinguishing feature of party families (Beyme Reference Beyme1985; Ware Reference Ware1996) and directly inform how freely a party can move in the policy space. In the words of Mair and Mudde, the ideological core is ‘a belief system that goes right to the heart of a party’s identity and […] address[es] the question of what parties are’ (1998, 220). Often grounded in traditional cleavages or more recent changes in value patterns in Western societies (Inglehart Reference Inglehart1977), these ideological cores are crucial for parties’ positions in the party spectrum, connection to voters, and role in government. This centrality of the ideological core is why policy change tends to be incremental and why parties have been characterised as ‘conservative organisations’ (Dalton and McAllister Reference Dalton and McAllister2015; Meyer Reference Meyer2013).

Here, it is important to note that the concept of the ideological ‘core’, which parties in the same party families share, differs fundamentally from ‘issue ownership’ (Petrocik Reference Petrocik1996), which ceases to exist once it is contested, that is, once more than one party credibly lays claim to a given issue. For instance, as Abou-Chadi (Reference Abou-Chadi2016) states, ‘green parties’ ownership […] of the environment issue is much higher than radical right parties’ issue ownership of immigration’ (2016, 421). However, even though radical right parties may not own the issue, immigration is still inextricably linked to their ideological identity.

Furthermore, the idea of the ideological core is different from the idea of principled versus pragmatic policies (Tavits Reference Tavits2007; see also Pattie and Johnston Reference Pattie and Johnston2001). While the theoretical idea is related, in that parties would expect higher voter risk when changing principled positions and should be rewarded for adaptability in pragmatic policies, the empirical implications are markedly different. Tavits (Reference Tavits2007) argues that voters have principled preferences on social issues that are value-based, including societal and individual principles (153), and that voters would punish parties for perceived lack of credibility (154). Pragmatic preferences, on the other hand, are located in the economic policy space, where ‘given that economic conditions themselves are subject to change, viable economic policies are not likely to be constant across time’ (154). Thus, voters would welcome the adaption of policy positions to new economic circumstances and ‘may perceive ideological dogmatism about policy alternatives as a sign of unresponsiveness, and they may reject stability and tenacity’ (155).Footnote 1

Instead of this static policy-based distinction, we build on the idea that parties’ programmes contain text that speaks to a party’s ideological core and text that is at the ideological periphery (Habersack Reference Habersack2025; Habersack and Werner Reference Habersack and Werner2023; see also Koedam Reference Koedam2022). The core defines the party’s identity and has particular importance for the party members’ identification with the organisation as well as the issue ownership and competence that voters assign to the party. Thus, the core contains the policies and positions that the party stands for, and is closely related to the party’s family denotation as Social Democratic, Conservative, Green, Radical Right, and so forth. At the same time, manifestos include text that is about policies at the party’s ideological periphery, which are policies not intricately linked to the party’s ideology and identity but that need covering because they are relevant for the specific society and state at the time.

We investigate changes in the core and periphery separately as these changes have different meanings. In a nutshell, a change in the core indicates a committed shift in the party’s identity, while a peripheral change does not have such a fundamental connotation and is less likely to have far-reaching consequences. A change in the core is a departure from the party’s ideological identity and means updating or even abandoning central policy positions. Changes in the periphery, on the other hand, are an adaption of solutions to general problems that members, supporters, and voters will not attribute to the party’s main competencies and values.

We connect our concept of the ideological core with the party family as these define the original ideological clusters of parties. There are approaches to establish groups of parties with common ideologies empirically (see, for example, De La Cerda and Gunderson Reference De La Cerda and Gunderson2024) but these make individual parties’ cores dependent on party competition as well as other contextual factors. As Mair and Mudde (Reference Mair and Mudde1998, p. 218) note, this method therefore often results in classifications that reflect national contexts more than party ideologies. Furthermore, we do not follow the approach by Koedam (Reference Koedam2022), who distinguishes parties’ primary and secondary dimensions of contestation based on the empirical salience of the cultural and economic dimensions within their manifestos. While this approach manages to distinguish parties based on economic or cultural cleavages, it loses a lot of information to differentiate the parties as, for instance, the cultural issues of the Greens and the Radical Right are markedly different.

Given the centrality of the ideological core to parties’ identities, it encompasses the policy positions on which parties distinguish themselves from one another. Within a party programme, the core should be where parties make claims that clearly signal to voters their fundamental policy principles. The periphery, by contrast, is the part of the programme that contains positions for policies that are necessary in any modern state but with which parties and their voters do not have any particularly strong connection. As a result, the core and periphery serve distinct functions within party programmes, which is reflected in our first hypothesis.

HYPOTHESIS 1 Parties take more extreme positions in their core compared to their periphery.

While salience theory and the notion of issue ownership hold that parties should emphasise issues that are at the ‘core’ of their ideological identity and de-emphasise other, ‘peripheral’ ones, another strategy is possible. Instead of emphasising or de-emphasising core and peripheral issues, parties can also treat them differently in terms of change. Since the risks of policy change causing rifts within the party, alienating voters, and losing the party’s identity are particularly connected to changes in the party’s ideological core, parties should be much more inclined to change their peripheral positions. As these are not connected to the identity of the party, the risks are lower while the potential to win new voters for whom these policies are salient is still given. Thus, our second hypothesis is as follows.

HYPOTHESIS 2 Parties are more likely to change their positions on peripheral issues than on core issues.

The next set of hypotheses focuses on differences between party types and how these distinctions influence their behaviour regarding core and peripheral policy positions. Party types, such as niche and mainstream parties, vary in their ideological focus, voter base, and strategies for maintaining relevance. These differences shape their tendencies towards ideological extremity, stability, and clarity in their core and peripheral policy positions.

Niche parties, such as green, radical right, and liberal parties, are typically defined by their concentrated focus on a narrow set of policy issues that are central to their identity and voter appeal (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2006; Wagner Reference Wagner2012). These parties often adopt more extreme positions to maintain their distinctiveness and reinforce issue ownership, signalling commitment to their key policy domains. For instance, green parties’ focus on environmental protection and radical right parties’ emphasis on immigration demonstrate their reliance on extremity to mobilise their core constituencies. Such positioning is critical to their survival, as moderation risks diluting their ideological brand. Thus, we hypothesise the following.

HYPOTHESIS 3 Parties belonging to niche party families are more likely to take more extreme positions in their core than mainstream parties. This distinction does not carry over to the periphery.

The stability of core positions is another defining characteristic of party types. For niche parties, whose existence depends on the salience and consistency of their core policies, any deviation risks alienating their base and undermining their credibility (Beyme Reference Beyme1985; Wagner Reference Wagner2012). For example, a Green party weakening their stance on environmental protection would jeopardise its defining identity. Mainstream parties, by contrast, rely on a broader ideological appeal and are therefore more flexible in adjusting core positions. Their adaptability often reflects a strategic focus on electoral pragmatism and coalition-building rather than ideological consistency. Adams et al. (Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2006) find that niche parties are therefore less likely to change their policy positions in response to shifts in public opinion than mainstream parties, which are more inclined to signal responsiveness on a broader array of salient issues. Consequently, we hypothesise the following.

HYPOTHESIS 4 Parties belonging to niche party families are less likely to change their positions on core issues compared to mainstream parties. This distinction does not carry over to the periphery.

Finally, previous research has shown that parties respond to electoral signals from voters and tend to adjust their strategies after losing elections (Somer-Topcu Reference Somer-Topcu2009).Footnote 2 Specifically, a key question in party competition concerns whether electoral performance influences the extremity of party positions. Budge et al. (Reference Budge, Ezrow and McDonald2010) argue in their integrated theory of party behaviour that parties are constrained by their ideological foundations when reacting to electoral signals. They note that ‘any Socialist party that totally abandons its concern about welfare imperils its own existence. […] Uninhibited free movement, as implied by office-seeking or vote-seeking assumptions, is just not an option’ (Budge et al. Reference Budge, Ezrow and McDonald2010, p. 792). This suggests that parties have fixed ideological cores with which they distinguish themselves from their competitors. However, the extent to which parties adopt more extreme or more moderate positions in their programmatic periphery may still fluctuate in response to electoral success or defeat.

We argue that parties strategically adjust the extremity of their peripheral positions to consolidate their voter base. When a party experiences electoral loss, it faces pressure to rally its core supporters. Thus, they will adopt overall more radical positions, reinforcing their position in the policy space. This is particularly relevant in times of electoral downturn, when parties seek to strengthen their identity rather than broaden their appeal (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2004). Conversely, when a party wins votes, it has incentives to moderate its periphery, appealing to a wider electorate. At the same time, their core policy positions will remain distant from the centre, given their importance to a party’s base and activists. This means that moderation primarily occurs in the periphery.

HYPOTHESIS 5 Electoral loss leads to more extreme positions in the periphery, whereas electoral gain leads to moderation. Changes in electoral performance do not affect parties’ cores.

Beyond extremity, electoral performance may also influence the degree to which parties change their positions altogether. While the causal chain between changes in the political environment, in voter preferences, and in party positions is still under investigation (Seeberg and Adams Reference Seeberg and Adams2025), research like Adams et al. (Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2004) has shown that parties move as a reaction to public opinion, of which elections are a very clear expression. Budge et al. (Reference Budge, Ezrow and McDonald2010) show in their simulation that while parties respond to electoral defeat with adjustments in their programmatic focus, these changes remain constrained by their ideological identity. Following this logic, we assume that parties change their core to a much lesser degree (if at all) than their periphery. Further, we argue that while electorally successful parties face altogether little pressure to adapt and alter their course, electorally struggling parties should feel compelled to introduce broader programmatic shifts in their periphery as they search for ways to regain competitiveness.

HYPOTHESIS 6 Electoral gain leads to stability in core and peripheral issues, while electoral loss leads to changes in peripheral issues, leaving the core unaffected.

A major consideration in these theoretical mechanisms is timing. The standard account of representation assumes that first, parties present their programmes, and second, voters choose the party best fitting their preferences. Parties change their programme based on their electoral outcomes and with the purpose of attracting new voters (see, for example, Adams and Somer-Topcu Reference Adams and Somer-Topcu2009; Downs Reference Downs1957; Dalton and McAllister Reference Dalton and McAllister2015). However, other accounts argue that parties posses information about their likely electoral fortunes before the election and, therefore, adapt their programme at this time (Adams and Ezrow Reference Adams and Ezrow2009; Habersack Reference Habersack2025; Panebianco Reference Panebianco1988; Schumacher and Öhberg Reference Schumacher and Öhberg2020). Similarly, experience gives parties a relatively good grasp of whether they might be in the position of negotiating government participation and need to take potential coalition partners’ positions into account. This distinction has an impact on when we assume the hypothesised effects of H5 and H6 take place. Thus, we will run our tests of H5 and H6 with and without a temporal lag.

Empirical Strategy

Methodological discussions related to party change often focus on the best ways to measure party positions and the nature and dimensionality of the policy space (Ezrow et al. Reference Ezrow, De Vries, Steenbergen and Edwards2011; Flentje et al. Reference Flentje, König and Marbach2017; König et al. Reference König, Marbach and Osnabrügge2017b; Lowe et al. Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhayliv and Laver2011). We follow the tradition of basing our analysis on party manifestos. While other approaches exist, including experts placing parties on scales (Jolly et al. Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022), party perceptions by citizens (Nyhuis and Stoetzer Reference Nyhuis and Stoetzer2021), and election-specific party self-positioning collected for voting advice applications (see, for example, Garzia and Marshall Reference Garzia and Stefan2014), party programmes remain the only source of their positions that originate from the parties themselves and that are stable and easily comparable cross-sectionally and longitudinally (Budge et al. Reference Budge, Klingemann, Volkens, Bara and Tanenbaum2001). Although different measurement approaches capture varying aspects of party positions (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Bernardi, Ezrow, Gordon, Liu and Phillips2019) and we do not claim that manifesto-based positions represent the ‘true’ party stances, they offer crucial insights into how parties seek to present themselves to the public and are thus central to our study.

Regarding our text analysis, we employ both manual and automated methods. The previous dominant approach by the Manifesto Project (Budge et al. Reference Budge, Klingemann, Volkens, Bara and Tanenbaum2001) measures party positions on the basis of policy statements being attributed one of fifty-six policy categories by human coders. Another strand of methods has used computerised attribution of, in particular, left–right positions to text and different scaling approaches (see, for example, Elff Reference Elff2013; Lowe et al. Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhayliv and Laver2011). Our approach retains the Manifesto Coding Scheme but uses an Large Language Model (LLM)-based approach to assign policy categories probabilistically. Rather than attributing each statement to a single category, we consider the ten most likely policy categories predicted by the LLM (Burst et al. Reference Burst, Lehmann, Franzmann, Al-Gaddooa, Ivanusch, Regel, Riethmüller, Weßels and Zehnter2023), acknowledging that a single policy statement can convey multiple policy messages at once. The model provides a probability distribution over potential categories (the Manifesto Project’s fifty-six policy issues), which we use as weighted inputs instead of relying solely on the highest-probability classification. This approach preserves more information from the text and allows for a more fine-grained measurement of parties’ issue focus. We then aggregate these weighted classifications to measure parties’ positions in the policy space. Additionally, we use the Manifesto Project’s human-coded policy categories (see below) to identify a party’s core and peripheral manifesto sections.

Data and Case Selection

For this analysis, we include parties from all Western European countries that are included with at least three elections since 1945 in the Manifesto Corpus (Lehmann et al. Reference Lehmann, Franzmann, Al-Gaddooa, Burst, Ivanusch, Lewandowski, Regel, Riethmüller and Zehnter2024) to have a sufficient timeline for measuring party position change. This means that our dataset includes parties from seventeen countries in a span from 1946 to 2022. These countries are Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

We exclude all parties that only appeared in one parliamentary election, as they do not allow us sufficient prediction of change, and parties with less than 2 per cent vote share for their relatively low relevance. Reducing the number of parties in the dataset increases the modelling speed and our ability to assess face validity. This means that we can analyse the changing positions of 137 parties, which are listed in Table A.1 of the Appendix.

Methods and Measurement

To execute our analysis, we use the Manifesto Project Corpus (Lehmann et al. Reference Lehmann, Franzmann, Al-Gaddooa, Burst, Ivanusch, Lewandowski, Regel, Riethmüller and Zehnter2024) as the textual basis. The Manifesto Corpus includes the text of parties’ electoral programmes, unitised into quasi-sentences that have a maximal length of one grammatical sentence (Werner et al. Reference Werner, Lacewell, Volkens, Matthieß, Zehnter and van Rinsum2021). In the Manifesto Dataset, each quasi-sentence is further categorised into one of fifty-six main policy areas by a human coder. As we use automated sentence-based classification of the same quasi-sentences, the human coding serves as a yardstick to evaluate the accuracy of these policy classifications. Our analysis operates in the following sequence of steps.

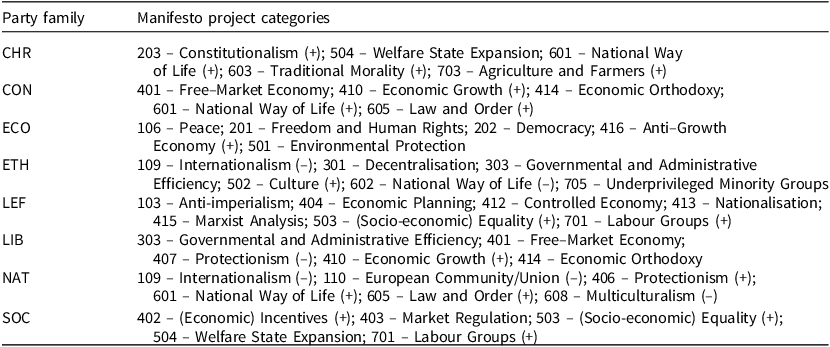

First, based on the Manifesto Project’s policy codes, we attribute each quasi-sentence as belonging to the core or periphery of the respective party’s ideology. We determine the policies at the core of a party’s ideology by their party family (see Table 1), considering Christian Democrats (CHR), Conservatives (CON), Green parties (ECO), Ethnic and Regional parties (ETH), Radical Left parties (LEF), Liberals (LIB), Radical Right parties (NAT) and Social Democrats (SOC). We draw on the operationalisation of party families’ cores developed by Habersack and Werner (Reference Habersack and Werner2023, p. 871) and extend this scheme to the radical right party family as policies pertaining to nationalism, authoritarianism, and conservatism (Mudde Reference Mudde2007). All quasi-sentences that do not fall within a party family’s core are defined as that party family’s ideological periphery.Footnote 3 Based on this categorisation, every manifesto in our corpus is split into two sections: the core document and the periphery document. Figures B.4 and B.5 in the Appendix show descriptive statistics for the empirical distribution of these two documents. Additionally, we derive a binary ‘niche party’ indicator from this classification, coding green, ethnic and regional, radical left, liberal, and radical right parties as niche (1), and Christian Democrats, Conservatives, and Social Democrats – consequently – as mainstream (0). This distinction follows the literature identifying niche parties as those with narrow programmatic appeals (Meguid Reference Meguid2008).

Table 1. Operationalisation of party families’ ideological cores

Note: ± indicates directional policy codes and refers to a party’s negative (–) and positive (+) positions on the respective policy issue.

Second, we then use the manifestoberta model to retrieve the predicted probability of each quasi-sentence to be classified as each of the fifty-six Manifesto Project coding categories (Burst et al. Reference Burst, Lehmann, Franzmann, Al-Gaddooa, Ivanusch, Regel, Riethmüller, Weßels and Zehnter2023). manifestoberta is a fine-tuned multilingual XLM-RoBERTa model that is trained on the existing Manifesto Project annotations and takes a quasi-sentence’s context into account when predicting the probability of a coding category being applied. Burst et al. (Reference Burst, Lehmann, Franzmann, Al-Gaddooa, Ivanusch, Regel, Riethmüller, Weßels and Zehnter2023) have trained and tested this model and shown that in 81 per cent of the cases, the human-coded category is among the top three most confident predictions. They also show that the model does not perform so well for very rare categories (for example federalism and niche economic positions) and for non-European countries. We take these limitations into account through our measurement strategy and case selection.Footnote 4

Applying this model to our corpus results in a data frame that includes the predicted probabilities for all fifty-six coding categories for each quasi-sentence. For each quasi-sentence, we retain the ten highest predicted categories, and thus the ten most likely categories, along with their probability score. Our validity check (Table A.2, Appendix) shows that the hand-coded Manifesto coding category that was assigned by the Manifesto Project coder appears among these ten highest probability categories with a likelihood between 94 per cent and 98 per cent. We interpret this result as a strong indication of the validity of the model’s classifications.

Compared to traditional approaches like resource-intensive human annotation, manifestoberta thus offers a distinct advantage: instead of assigning a single classification per quasi-sentence, it frequently identifies two, three, or even four policy areas with roughly equal probability. This better reflects the reality that parties often address multiple policy issues simultaneously through particular statements – either due to internal dissent, which necessitates ambiguity in positioning (Koedam Reference Koedam2021; Rovny Reference Rovny2012), or as part of a strategic framing effort, such as the radical right’s rhetorical linkage of immigration and security policies (Helbling Reference Helbling2014; Zaslove Reference Zaslove2004). For instance, consider the following sentence from Fianna Fáil’s 2020 manifesto: ‘The existential challenge of climate change heightens the pressing need to develop our public transport infrastructure, which is vital to curbing emissions and placing our future development on a sustainable path’. While manifestoberta correctly classifies this quasi-sentence as ‘416 – Anti-Growth Economy: Positive’ (41 per cent), it also suggests ‘501 – Environmental Protection’ (38 per cent) and ‘411 – Technology and Infrastructure: Positive’ (21 per cent). This multilabel classification provides a more comprehensive assessment of the policy areas addressed than any single label.Footnote 5

As a third step, we aggregate the predicted categories for all quasi-sentences contained in each core and periphery document, creating an economic and a cultural left–right score for each. We proceed in two steps. First, for each coding category we calculate their overall predicted share in each ‘manifesto section’ (the core or periphery of a given document). We do this by summing up the predicted probabilities for each category in all quasi-sentences that are predicted to contain this category. Any quasi-sentences that are not predicted to include the specific category are logically included as zero. Second, we divide this score by the number of quasi-sentences in this specific document section.Footnote 6 This procedure yields information on parties’ core and peripheral documents on a total of fifty-six policy codes in the same format as the Manifesto Project’s main dataset (that is, for each document section, the labels add up to 100 per cent).

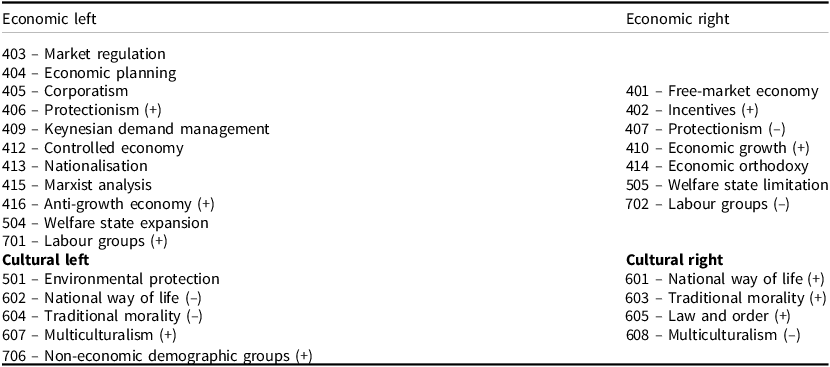

Then we use these predicted shares to calculate party positions along the two left–right dimensions by subtracting left category shares from right category shares, normalising by their sum. This means positive values denote right-wing positions while negative values denote left-wing positions. To identify the economic and cultural left and right Manifesto Project categories, we compared our own judgement with the approaches by Krause (Reference Krause2020) and the Manifesto Project in 2022,Footnote 7 and removed any ambiguous allocation. Table 2 shows our attributions. The details of the two alternatives can be found in the Online Appendix, Table B.3, and the respective replications of the analyses in Tables C.6 and C.7.Footnote 8

Table 2. Manifesto project left and right categories on two dimensions

Note: Authors’ own operationalisation.

To operationalise ideological extremity, we measure the deviation of each party’s economic and cultural position from the ideological centre on both dimensions. Specifically, we construct the Euclidean distance between a party’s position (x,y) and the neutral midpoint (0,0). This measure accounts for both dimensions simultaneously and provides an indicator of how far a party’s stance diverges from the ideological centre:

This approach captures the overall ideological distance while maintaining sensitivity to shifts along either dimension. Parties positioned farther from the centre are considered more ideologically extreme, irrespective of direction. Importantly, this indicator of extremity reflects the extent of a party’s policy divergence in a two-dimensional policy space, not ‘extremism’ in the sense of its commitment to democratic norms or its level of authoritarianism (for a similar approach, see Dow Reference Dow2011; Ezrow Reference Ezrow2008). As in related work, we adopt a spatial modelling perspective, using Euclidean distance to locate parties and their programmes within a multidimensional ideological space (see, for example, Rosset and Kurella Reference Rosset and Kurella2021). Accordingly, ideological extremity is understood as the degree to which a party’s positions deviate from the theoretical centre, regardless of the content of those positions.

To measure positional change over time, we assess the movement of each party’s core and periphery in the two-dimensional ideological space – comprising the economic (x) and the cultural (y) dimension – between successive elections. For each party, we compute the absolute change in position as the Euclidean distance between its locations in consecutive elections.Footnote 9 This is given by:

Given the highly skewed nature of our change variables – where most values are close to zero due to the often incremental nature of party position shifts – we log-transform these variables. The transformation is applied to each positional change measure, adding a small constant to handle zero values:

Figure B.2 in the Appendix displays the log-transformed density distributions of positional shifts along the cultural and economic dimensions, as well as combined positional change. The figure shows that positional change is skewed towards smaller values, consistent with the notion of parties favouring small adjustments from one election to the next over dramatic realignment.

While our approach focuses on positional shifts, it is important to note that changes in salience may influence the underlying left–right scores. For instance, a reduction in the emphasis placed on economic issues could affect a party’s overall position, even if its stance on those issues remains constant. While some argue that salience changes are conceptually identical to positional shifts (see, for example, Budge Reference Budge1994), other literature shows that position and salience can be changed independently (Meyer Reference Meyer2013; Neundorf and Adams Reference Neundorf and Adams2018; Spoon et al. Reference Spoon, Hobolt and De Vries2014). To account for the potential influence of salience on positional measures, we include controls for the salience of economic and cultural dimensions in each manifesto section. Specifically, we calculate the proportion of quasi-sentences dedicated to economic and cultural policy areas, as derived from the predicted shares of the manifestoberta model. These proportions allow us to investigate whether observed changes in positions might stem from shifts in the salience of specific policy areas rather than genuine ideological movement.Footnote 10

Results

To test our hypotheses, we first compare the extremity of parties’ core and peripheral positions before assessing the hypothesised effects on extremity using linear regression models with clustered standard errors at the election level. In the second step, we analyse the position change variables using the same modelling approach. All models include fixed effects for country and election date to account for the election-based nature of the data. To examine the impact of electoral performance on both extremity and position change, we construct two variables, capturing a party’s vote share change from t −1 to t 0 and from t −2 to t −1, respectively. Additionally, we control for government participation and whether the party held the Prime Minister (or equivalent) position at time t 0, as we expect these roles to limit parties’ focus on their core issues, temper policy extremity, and constrain parties’ ability to shift their positions.

Analysing Ideological Extremity

To show the empirical results of our first dependent variable, Figure 1 graphs the density distribution of ideological extremity (that is, parties’ combined distance from the centre on the cultural and economic dimension).Footnote 11 The figure clearly illustrates that parties tend to take more extreme and thus distinguishable, positions in their cores compared to their peripheries. This is confirmed by parties’ economic cores being 14 percentage points more distant and parties’ cultural cores being on average 22 percentage points further removed from the centre than their respective peripheries. Furthermore, we find that parties’ peripheries are somewhat more variable, as evidenced by a coefficient of variation of 47 per cent to 38 per cent on the economic dimension and 68 per cent to 56 per cent on the cultural. These descriptive patterns conform to our hypotheses 1 and 2 and our general argument that parties treat their ideological cores and peripheries differently.Footnote 12

Figure 1. Combined cultural and economic extremity by manifesto section.

Note: Dashed line denotes the overall density across the entire manifesto.

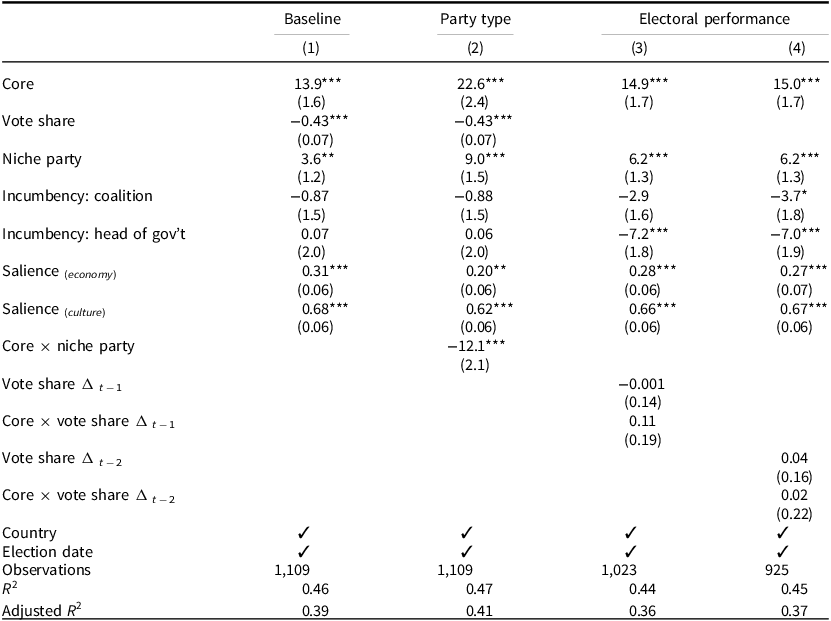

To test our hypotheses about the extremity of parties’ cores and peripheries, we run a series of regression models that are summarised in Table 3. The result for the core versus periphery variable further supports our hypothesis 1. The coefficients for ‘Core’ are positive and statistically significant (p < 0.001) across all models, confirming that ideological extremity is systematically higher in the core sections of parties’ manifestos. This result holds even after controlling for party type, electoral performance, and other contextual factors. It indicates that parties are committed to maintaining distinct ideological stances in their cores, which serve as the foundation of their political identity.

Table 3. Regression results for combined ideological extremity

Note: data from MARPOR; cluster-robust standard errors at the country × election level; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

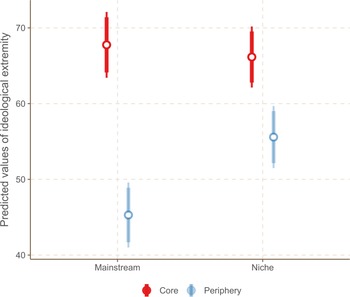

Hypothesis 3 suggests that niche parties are more likely to adopt more extreme positions in their core compared to mainstream parties. The interaction term in model 2 (Table 3) shows a negative and statistically significant (p < 0.001) effect. However, Figure 2 shows that this interaction effect is not based on mainstream and niche parties differing in their cores, but niche parties showing more extreme peripheries than mainstream parties.Footnote 13 While not hypothesised, this likely reflects their reliance on a narrower and more coherent set of policy issues (for example, the environment and related peripheral policies in foreign policy for Green parties or immigration and related peripheral policies in education for radical right parties) to mobilise specific voter segments. In contrast, mainstream parties maintain somewhat more moderate peripheral positions.

Figure 2. Predicted ideological extremity based on Euclidean distance by manifesto section and party type, 95 per cent and 99 per cent CI.

Regarding hypothesis 5, which posits that while electoral fortunes do not affect change in a party’s core, electoral loss leads to more extreme positions in the periphery, and electoral gain fosters more moderate peripheries, Table 3 shows no effect. This holds independent of whether we consider combined ideological extremity or break it down to only the cultural or economic dimension, as evidenced by the results presented in Table C.4 in the Appendix.

Figure 3 illustrates how parties adjust their ideological extremity in response to electoral performance, distinguishing between core and peripheral manifesto sections. The figure confirms that parties show little reaction to electoral fortunes. We find no reaction in their periphery and only a small and statistically non-significant increase in the extremity of parties’ cores with electoral success. The main effect we see is that electoral loss leads to a greater spread and thus variety in the extremity of parties’ cores and peripheries. This might point to a lack of coherence in strategic reactions to electoral losses, with some parties opting to adopt more extreme cores and peripheries while others moderate.

Figure 3. Predicted ideological extremity based on Euclidean distance by manifesto section and vote share change, 95% CI.

Thus, while leadership changes and contextual stimuli may at times prompt parties to adopt more or less extreme positions, electoral gains and losses do not generally and automatically lead parties to reconsider their ideological stances. This cautious approach to position-taking aligns well with prior research on party behaviour, which emphasises the importance of a consistent policy profile and of maintaining ideological credibility (Downs Reference Downs1957, p. 122).

Analysing Position Change

Building on these insights into the strategic role of parties’ cores for distinguishing themselves from competition through more extreme stances, we now shift our focus to how parties adjust their core and peripheral positions over time. Our theoretical argument posits that the magnitude of these shifts is, similarly, influenced by the distinction between core and peripheral issues, as well as by factors related to party type and electoral performance.

Figure 4 plots the density functions of positional changes distinguishing parties’ core and periphery. It shows that, in general, parties only change their positions in small increments and, specifically, that parties change their cores less than their peripheries. This result lends descriptive support to our hypothesis 2, which suggests that parties are more likely to change their positions on peripheral issues than on core issues.

Figure 4. Logged combined cultural and economic position change by manifesto section.

Note: Dashed line denotes the overall density across the entire manifesto.

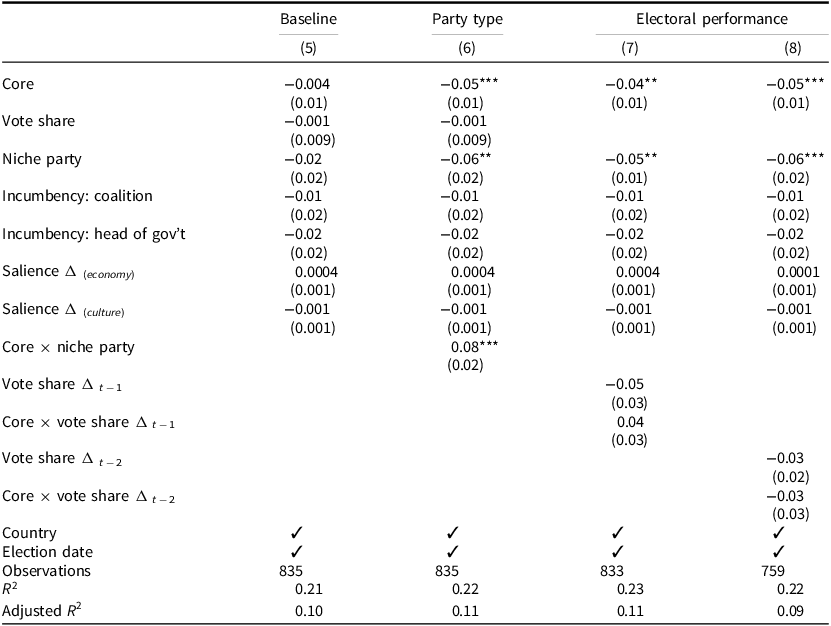

The regression models presented in Table 4 also provide strong empirical support for hypothesis 2. The coefficients for ‘Core’ are negative and statistically significant (p < 0.01) across all but one model, indicating that position changes are systematically lower in parties’ cores compared to their peripheries. This aligns with the expectation that parties exhibit greater flexibility in adjusting their peripheral issue positions while remaining steadfast when it comes to their core policies. These are central for their voter mobilisation and their party identity.

Table 4. Regression results for combined position change

Note: data from MARPOR; cluster-robust standard errors at the country × election level; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Hypothesis 4 predicted that niche parties would be more resistant to change in their core positions compared to mainstream parties. Model 6 supports this notion on first glance, indicating that niche parties are more reluctant to update their positions in matters that are of fundamental importance to them and their constituents. This effect is statistically significant at p < 0.001. However, Figure 5 sheds further light on the mechanism underlying this interaction term. It illustrates that niche parties are altogether more careful, while mainstream parties exhibit greater flexibility in adapting their peripheral policy positions. In other words, holding other factors constant, the interaction of the two factors leads to significantly greater ideological shifts – about 8.3 per cent more – compared to what we would predict if these two factors operated independently. This aligns with the notion that mainstream parties, which more often find themselves in office, need to cater to a wider audience, demanding more flexibility in peripheral areas, yet not in core policy areas.

Figure 5. Predicted ideological change between elections by manifesto section and party type, 95 per cent and 99 per cent CI.

A key question in our analysis is how electoral performance shapes shifts in core and periphery positions. Hypothesis 6 anticipated that electoral gain leads to stability in core and peripheral issues, while electoral loss leads to changes in peripheral issues, leaving the core unaffected. However, changes in parties’ vote shares, whether considering immediate or lagged policy responses to changes in performance, do not show a direct and automatic influence on their willingness to shift positions. The results in Table 4 and graphing the interaction term in Figure 6 show that neither vote share change by itself or its interaction with core and periphery have any effect.Footnote 14 Thus, parties do not change their positions more or less depending on their electoral fortunes and do not distinguish between their ideological core and periphery in this decision.

Figure 6. Predicted ideological change between elections by manifesto section and vote share change, 95 per cent CI.

Discussion

Previous research has examined how parties navigate between emphasising their core issues and ‘riding the wave’, strategically focusing on issues that are temporarily salient in the electorate (Carmines and Stimson Reference Carmines, Stimson and Riker1993; Meguid Reference Meguid2008; Wagner and Meyer Reference Wagner and Meyer2014). While this literature has illuminated how parties respond to shifting political environments, it tends to distinguish party behaviour among specific ideological or topic dimensions. At the same time, it often treats party platforms as uniform. This neglects the critical distinction between parties’ ideological core and peripheral policy issues, which we argue parties should adapt differently when strategically taking positions. In this article, we therefore focus on how political parties adapt to changing conditions both within the core of their manifestos and with respect to those issues that are typically farther removed from their party identity.

To answer this question, we utilise data from the Manifesto Project Corpus (Lehmann et al. Reference Lehmann, Franzmann, Al-Gaddooa, Burst, Ivanusch, Lewandowski, Regel, Riethmüller and Zehnter2024) and use the large language model manifestoberta for content classification (Burst et al. Reference Burst, Lehmann, Franzmann, Al-Gaddooa, Ivanusch, Regel, Riethmüller, Weßels and Zehnter2023). Crucially, we divide the manifestos into parties’ ideological core and periphery instead of following the common practice to treat each party programme as one coherent document. Thus, we depart from identifying parties’ positions on the basis of one single document, analysing their salience and change patterns. We take the argument seriously that parties are constrained in their ideological position-taking by concerns about their identity, members, and core voters (Budge et al. Reference Budge, Ezrow and McDonald2010). Assuming that parties are aware of these constraints, we posit that parties are more extreme and stable in their ideological cores. At the same time, parties need to be able to change positions to attract new voters. We argue that they do so in their ideological periphery, which is the policy space that is not directly connected to their identity. This periphery allows parties to manoeuvre without risking their identity and core support.

Our findings underscore the importance of this distinction. Parties consistently adopt more extreme positions within their ideological cores compared to their periphery, a pattern evident across various party families and political systems. This finding holds consistently for both mainstream and niche parties, meaning that at the aggregate level, for instance, Social Democratic parties have as distinct ideological cores as Green parties. In addition, ideological cores tend to demonstrate greater stability over time than parties’ ideological peripheries. Ideological cores act as stabilising anchors, limiting the scope for significant shifts and reinforcing a coherent ideological narrative that parties rely on to maintain voter trust and internal cohesion. In contrast, ideological peripheries provide strategic flexibility, allowing parties to adapt to changing political contexts without fundamentally altering their core policy agenda. This asymmetry in how parties handle core versus peripheral issues highlights the important role of the core–periphery distinction as a framework for understanding party behaviour and parties’ ideological positioning.

In terms of party type, our results reveal that niche parties generally maintain more extreme positions in their periphery while mainstream parties adopt more moderate peripheries. Thus, niche parties seem to adopt a strategy of greater coherence between core and periphery while mainstream parties use peripheries to attract distant voters. Furthermore, niche parties are overall less likely to fundamentally shift their policy stances, while mainstream parties demonstrate greater flexibility in adapting their ideological peripheries. This is consistent with the logic that niche parties rely on a loyal voter base with strong attachments to specific issues, making shifts in their cores particularly costly.

Regarding parties’ responses to changing electoral fortunes, the findings are less clear-cut. While decreasing vote shares seems to induce moderation and better results induce more bold and extreme positions, parties do not uniformly respond to electoral gains or losses by adjusting their policy stances, suggesting that factors beyond immediate electoral feedback play a role. Internal party dynamics, leadership stability, and strategic considerations related to long-term party branding likely moderate the relationship between electoral outcomes and programmatic change. While some studies have found that parties frequently update their positions in response to shifts in the voter market (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2004; Downs Reference Downs1957; Habersack Reference Habersack2025; Somer-Topcu Reference Somer-Topcu2009), our findings align more closely with a large body of literature rooted in the Rokkanian tradition, which portrays parties as conservative organisations, reluctant to fundamentally shift their policy stances between elections.

In sum, this article shows that the distinction between parties’ ideological cores and peripheries matters and is empirically observable. We show that parties do not only own specific issues and compete differently on specific ideological dimensions, they also vary their strategic decisions in different parts of their electoral documents. One conceptual issue we were not able to solve, however, is that the positional changes we measure might be based in salience changes of specific policies. While we control for the salience of the economic and cultural dimensions, we cannot rule out effects of salience changes within these dimensions. However, this is a general issue among the salience-based approach to measuring party positions (Budge et al. Reference Budge, Klingemann, Volkens, Bara and Tanenbaum2001; Lowe et al. Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhayliv and Laver2011) and its resolution is outside the scope of this article. Our contribution here is the theoretical and empirical distinction between parties’ ideological core and positional periphery.

This distinction has implications for the literature on party responsiveness and competition writ large. So far, these topics have mainly been analysed in terms of general left–right positions or specific policy areas. Both would benefit from taking the core versus periphery distinction into account. General studies about changes in parties’ left–right positions should distinguish where exactly these changes originate, as changes in the core or periphery have very different meanings. Likewise, studies of individual policy issues and strategic behaviour like blurring should account for whether a policy field belongs to a party’s core or periphery, as this shapes not just how parties engage with it, but also whether they prioritise it as a defining stance or relegate it to the margins of their programme.

Furthermore, the distinction between ideological core and policy periphery may help account for some of the discrepancies observed across party position measures. While it remains unclear which types of information expert respondents rely on when evaluating party positions – such as in the CHES (Jolly et al. Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2022) or similar surveys – it is plausible that they implicitly weigh changes in a party’s ideological core more heavily than shifts in peripheral policy areas. If so, expert-coded positions may systematically align more closely with core programmatic commitments than with peripheral policy adjustments. Investigating this possibility could improve the interpretation of expert survey data and clarify how such measures relate to manifestos or voter perceptions. More broadly, incorporating the core–periphery distinction may enhance the construct validity of expert-based estimates of party positions.

Finally, research on political representation and citizen–party linkages may also benefit from incorporating the core–periphery distinction. Studies have shown that citizens rarely update their perceptions of party positions in response to actual programmatic change (Plescia and Staniek Reference Plescia and Staniek2017; Wagner and Meyer Reference Wagner and Meyer2023), and work on positional congruence often finds limited alignment between parties and their electorates (Golder and Stramski Reference Golder and Stramski2010; Werner Reference Werner2020). Distinguishing between core and peripheral policy change could help identify mechanisms underlying these findings: citizens may be more likely to perceive and respond to shifts in a party’s ideological core than to adjustments in its policy periphery. As a result, congruence may be systematically higher – and more normatively meaningful – on core dimensions. Incorporating this distinction could thus sharpen theories of political representation by clarifying when and how voters perceive party change, and what kind of programmatic alignment they expect or prioritise.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123425101154.

Data Availability statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/C3NMA7. Replication materials are also available on GitHub at: https://github.com/FabianHabersack/parties_ideological_cores_vs_peripheries.

Acknowledgements

The computational results presented here have been achieved (in part) using the LEO HPC infrastructure of the University of Innsbruck. We thank Werner Krause, Simon Franzmann as well as the reviewers and editors of BJPS for their helpful and productive comments and suggestions. Fabian Habersack thanks the Research School of Social Sciences at the Australian National University for their support through the RSSS Fellowship, which enabled work for this research.

Financial support

This research did not receive additional funding.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical standards

The research meets all ethical guidelines, including adherence to the legal requirements of the study country.