Introduction

This article will examine the role played by the imperial household in shaping the chronic fiscal crisis faced by the Qing regime in the last half a century of dynastic rule. For this study, a crisis is a surge in expenses beyond both available income and the capability to obtain additional financing. The Taiping Rebellion’s 1853 seizure of the Yangtze River Delta precipitated a dual fiscal catastrophe for the Qing regime: While triggering a dramatic surge in military expenditures that strained the state treasury, it simultaneously crippled revenue collection from regional salt monopolies and customary taxes – critical revenue streams that had traditionally sustained imperial household finances.Footnote 1 Confronted with catastrophic revenue shortfalls, the Imperial Household Department (neiwufu 内務府) resorted to requisitioning funds from the Board of Revenue (hubu 戶部) in 1857 – initiating fiscal transfers unseen since the mid-1700s and establishing a precedent that persisted until the final years of the dynastic rule.Footnote 2

This study will demonstrate how the Imperial Household Department’s systematic fiscal extraction from the Board of Revenue operated as an institutional mechanism – simultaneously mirroring the deepening fiscal crisis of the late Qing state while actively compounding its financial disintegration throughout its final six decades. On the one hand, the Board of Revenue’s intensified efforts to meet the imperial household’s incessant fiscal demands exerted great pressure on the scarce fiscal resources that were otherwise earmarked for the Qing state’s public-oriented expenditures. On the other hand, the deteriorating fiscal conditions precipitated a paradigm shift in imperial expenditure patterns. Faced with contracting revenue streams and escalating court expenditures, the Imperial Household Department systematically abandoned its traditional adherence to pre-established fiscal quotas. Instead, it adopted an opportunistic approach to resource extraction, routinely bypassing budgetary constraints to secure discretionary funding through ad hoc requests to the Board of Revenue.

Studies of late-Qing fiscal governance have predominantly focused on intergovernmental dynamics between central and provincial authorities.Footnote 3 Yet this analytical framework rests upon an undertheorized conceptualization of “central power” (zhongyang 中央)Footnote 4 that obscures a critical institutional reality increasingly recognized in recent historiography: the Qing state’s dual patrimonial-bureaucratic governance structure.Footnote 5 Emerging scholarship on the imperial household apparatus has fundamentally reconfigured our understanding of Qing state formation by revealing how patrimonial authority operated through parallel administrative institutionalization.Footnote 6 Particularly noteworthy is the imperial household’s deployment of its ultra-bureaucratic prerogatives to structurally reconfigure state institutions.Footnote 7 Recent studies have demonstrated that during the High Qing period, the Imperial Household Department systematically deployed personal agents to collaborate with merchant consortia,Footnote 8 thereby dramatically expanding its fiscal dominion through semi-privatized revenue channels.Footnote 9 By integrating the imperial household’s political economy into analyses of late-Qing fiscal administration, this study reveals two critical phenomena: first, the destabilization of the historic equilibrium between patrimonial and bureaucratic fiscal systems – a crucial yet previously neglected dimension of late imperial political economy; second, the accelerated institutional dysfunction manifested through systemic rent-seeking and regulatory arbitrage that characterized the fiscal relationship between the imperial household and the bureaucratic sector in dynasty’s final decades.

This study contends that the Taiping Rebellion (1851–1864) functioned as an institutional inflection point through its catastrophic disruption of the salt tax administration and customary fiscal networks – the imperial household’s principal revenue arteries. The resultant fiscal hemorrhage fundamentally eroded the operational autonomy of the Imperial Household Department. This, in turn, brought an end the century-old fiscal segregation system institutionalized since the mid-eighteenth century that had maintained parallel budgetary spheres for patrimonial and bureaucratic administrations. This fiscal shock precipitated a pathological dependency cycle. Deprived of its customary income streams while constrained by path-dependent institutional rigidities – notably the inability to rationalize its bloated bureaus or reduce hereditary stipendiaries – the imperial household increasingly had to rely on coercive fiscal transfers from the Board of Revenue. Crucially, in contrast to representative governments,Footnote 10 the autocratic framework of the Qing rule lacked institutional safeguards – neither statutory fiscal allocations nor accountability mechanisms existed to check the throne’s extractive demands. The imperial household’s breakthrough fund request from the Board of Revenue in 1857 gradually became the norm, persisting until the final years of the dynasty’s rule. This development further intensified the implosion of the dynasty’s core governance dialectic – the delicate balance between bureaucratic rationalization and patrimonial prerogative. Rather than attributing the late-Qing fiscal collapse solely to rebellion-induced resource depletion, this study recontextualizes it through the disintegration of the regime’s fundamental governance dialectic – the historically maintained equilibrium between bureaucratic systematization and imperial patrimonialism. It posits that the imperial household’s unfettered access to state funds through semi-privatized channels not only amplified systemic irregularities and fiscal fragility, but crucially stifled institutional innovation. By circumventing the need for experimental fiscal mechanisms that might have addressed imperial liquidity constraints through revenue expansion, Qing rulers inadvertently accelerated their regime’s fiscal disintegration through path-dependent governance.

The body of this article is divided into three sections. The first section provides introductory background regarding how Emperors Yongzheng and Qianlong established and institutionalized a separation between the imperial Privy Purse management and the bureaucratic state finance. While regularizing the imperial household’s revenues and expenses and reducing its interference in the fiscal resources of the governmental sector, this institutional arrangement also established separate revenue streams for the imperial household and provided it financial flexibility to wield ultra-bureaucratic control. The second section examines the increasingly severe payment default problems faced by the Imperial Household Department during the Taiping Rebellion, after a certain portion of the Canton customary taxes and Lianghuai salt taxes, which were earmarked for the imperial household’s coffers, failed to be remitted as scheduled. This laid the very backdrop of the Imperial Household Department’s breakthrough demand for direct subsidies from state coffers in 1857 – the first breach over a century of the maintained fiscal separation between imperial and state finances. The third section analyzes the post-Taiping normalization of imperial fiscal extraction (1864–1908), demonstrating how routinized transfers from bureaucratic to patrimonial accounts fundamentally destabilized the Qing’s core governance dialectic. It will show how imperial consumption patterns – prioritizing court spectacle over state functionality – accelerated fiscal fragmentation while constraining modernization efforts. This article will conclude by situating its findings within comparative framework of divergent courtly expenditure patterns between representative governments and autocratic regimes. It will expose the deep irony inherent in an autocratic regime’s self-regulatory arrangements when divorced from institutionalized accountability frameworks. It will argue that by normalizing fiscal breaches as entitlements during crises, the regime perpetuated institutional rigidity that prioritized survival over systemic reform.

The emperor’s ledger: crafting fiscal autonomy in Qing China

Scholars have long noted the absence of effective constitutional checks in Qing governance.Footnote 11 However, this observation does not imply that emperors exercised unrestrained autocratic power.Footnote 12 In fiscal administration specifically, Qing rulers institutionalized a clear separation between the Privy Purse and state treasury.Footnote 13 The imperial household was mandated to maintain financial independence from bureaucratic institutions, as exemplified by the principle that “the imperial household shall not depend on the Board of Revenue for its maintenance.”Footnote 14 This institutional dichotomy persisted even during periods of fiscal strain, as demonstrated by the 1873 remonstrance from the Minister of Revenue against the Imperial Household Department’s encroachment on state funds:

By dynastic precedent, the Board of Revenue administers all revenues under Heaven while the Imperial Household Department provisions the Inner Court. Regular taxes – land-poll levies, customs duties, and principal salt taxes – flow to the Board of Revenue. Only “extra-budgetary surpluses” (ewai yingyu 額外盈餘) are allocated to the Imperial Household. Thus, the Board funds capital administration and provincial military expenditures, while the Household sustains the Forbidden City’s guards and staff. These constitute distinct fiscal systems with separate revenue streams and expenditure mandates – a separation that must remain inviolate.Footnote 15

This principle of imperial fiscal separation emerged as a response to escalating court expenditures, leading the Qing imperial household to institutionalize revenue extraction through commercial monopolies and “surplus” funds while strategically avoiding direct appropriation of the state’s principal tax revenues. During the early Qing period, the imperial household sustained itself through diversified income streams: rents from imperial estates, tributary gifts from domestic and foreign envoys, profits from the ginseng and fur monopolies, interest from imperial pawnshops, and confiscated properties.Footnote 16 With a modest court size and relatively simple administrative needs,Footnote 17 early emperors consciously restrained palace expenditures, frequently contrasting their fiscal prudence favorably against the perceived extravagance of the preceding Ming dynasty.Footnote 18 This system remained sustainable until the mid-eighteenth century, with Imperial Household Department’s expenditures rarely exceeding regular revenues and only occasional transfers requested from the Board of Revenue.Footnote 19 The Qianlong reign (1736–1795) marked a turning point as escalating court costs necessitated frequent fiscal interventions. In response, the Board institutionalized the “reserve silver for Inner Court expenditures” (kuchu neifu beiyong yinliang 庫儲內府備用銀兩), establishing de facto spending ceilings while accommodating imperial demands.Footnote 20 Recent scholarship reveals that the imperial household’s solvency during this period stemmed less from fiscal restraint than from systemic exploitation of Qing China’s expanding commercial economy. The throne strategically deployed booi bondservants – hereditary imperial agents – to control lucrative salt administration and customs offices. This mechanism enabled the diversion of “surplus” revenues (yingyu 盈餘) from local administrative funds to the Privy Purse, circumventing constitutional prohibitions by technically avoiding appropriation of “principal taxes” (zhengxiang 正項) earmarked for the Board of Revenue. Through such institutional innovations, the imperial household secured autonomous revenue streams while maintaining the formal separation between state and imperial finances.Footnote 21

The fiscal duality of the Qing imperial system manifested a paradoxical governance mechanism: While the Privy Purse’s financial autonomy ostensibly protected state revenues from arbitrary imperial appropriation, it concurrently empowered monarchs to bypass bureaucratic constraints through discretionary fiscal instruments. By the middle of the Qianlong period, this dual structure had been institutionalized through two principal mechanisms. First, the imperial household strategically deployed booi bondservants – the emperor’s personal agents – to supervise lucrative salt administration and customs offices, thereby establishing direct control over key revenue streams.Footnote 22 Second, the court developed an institutionalized “surplus” taxation framework through systematic management of such distinct fiscal categories as “idle” funds (xiankuan 閑款), “unexpended fiscal reserves” (jiesheng yin 節省銀), and “surplus” taxes, which were collected by the imperial salt and customs officials and retained under the rubric of the “public-expense funds” (gongfei 公費).Footnote 23 Annually predetermined allocations from these gongfei reserves were systematically transferred to imperial coffers, while specific portions were earmarked for special discretionary funds.Footnote 24 The gongfei system’s administration through the deployment of bondservants in salt and customs offices thus facilitated the emergence of a parallel “surplus” taxation apparatus that effectively functioned as an imperial slush fund, exclusively catering to the monarchy’s discretionary financial requirements. These institutional innovations proved particularly consequential to the fiscal expansion of the imperial household. By latest 1768, this parallel financial system had not only eliminated the Privy Purse’s chronic deficits but generated substantial surpluses.Footnote 25

Between 1768 and 1857, the Imperial Household Department not only abstained from requesting funds from the Board of Revenue but frequently reversed the fiscal flow: During crises such as wars, floods, or droughts – or even when the Privy Purse held excess reserves – the throne systematically reallocated silver from the imperial coffers to the state treasury.Footnote 26 This pattern underscores a critical dimension of imperial fiscal ideology: Emperor’s adherence to the separation principle was most evident during periods of revenue contraction rather than abundance. When the Imperial Household Department faced severe budgetary constraints, the throne compelled the Department to rely on its diminished resources rather than seek state support. A striking illustration of this dynamic occurred in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, when declining commercial activity in the Lower Yangtze Delta – the Imperial Household Department’s primary revenue base – precipitated acute financial strain. In response, the Emperor Jiaqing (r. 1796–1820) mandated the transfer of residual Privy Purse reserves to the state treasury, prioritizing fiscal orthodoxy over institutional self-interest. The Emperor Daoguang (r. 1820–1850) intensified this austerity, slashing court expenditures to unprecedented levels, including personal imperial expenses, while continuing the practice of replenishing state coffers with Imperial Household Department’s funds.Footnote 27 By 1851, fiscal exigencies reached a climax under the Emperor Xianfeng (r. 1850–1861), who ordered the complete liquidation of the Privy Purse’s silver reserves to fund counterinsurgency efforts against the Taiping Rebellion in Guangxi.Footnote 28 It was against this century-long backdrop of rigorous fiscal compartmentalization – marked by the Imperial Household Department’s operational self-sufficiency and the throne’s unwavering enforcement of the separation doctrine – that the Department’s request for state funds in 1857 emerged as a significant anomaly. This deviation not only highlighted the systemic pressures of late Qing crises but also underscored the erosion of a foundational fiscal principle that had long defined Qing governance.

The financial insolvency of the imperial household department, 1851–1864

The Taiping capture of the Lower Yangtze in 1853 precipitated an unprecedented fiscal mobilization by the Qing Board of Revenue to meet escalating military expenditures. Between 1851 and 1853, the central government deployed a multi-pronged strategy: interprovincial aid (xiexiang 協餉), expanded sale of official titles (juanshu 捐輸), wasteland reclamation projects, official salary reductions, and experimental currency issuance.Footnote 29 Yet the Taiping’s territorial expansion into core revenue-generating provinces – particularly the Lower Yangtze economic heartland, catastrophically eroded the efficacy of these measures. On the one hand, provinces previously functioning as net contributors to the xiexiang system increasingly became aid recipients themselves, collapsing the interregional fiscal redistribution mechanism that had sustained Qing military logistics for centuries.Footnote 30 On the other hand, the government’s deteriorating political legitimacy undermined both the market for purchased offices – a hallmark of late imperial crisis financing – and public confidence in its hastily issued fiduciary currencies.Footnote 31 By mid-1853, with conventional revenue channels exhausted, the court reluctantly sanctioned two transformative policies: Provincial commanders were authorized to raise personal militias (yongying 勇營), while ad hoc transit taxes (lijin 厘金) on commercial goods were legalized. These concessions marked a pivotal decentralization of fiscal-military authority, effectively outsourcing revenue extraction and military organization to provincial actors. Though initially framed as wartime exigencies, these measures fundamentally reconfigured the Qing state’s extractive capacities, trading centralized control for short-term survival.Footnote 32

As the Board of Revenue grappled with wartime fiscal demands, the Imperial Household Department faced unprecedented fiscal strain. Following two major allocations to Guangxi military campaigns in 1851, the Privy Purse’s reserves dwindled to levels insufficient for basic operational needs. By 1852, the Imperial Household Department initiated drastic austerity measures: streamlining administrative units, halting imperial construction projects, and pursuing extraordinary revenue-generating schemes. These included liquidating treasures from the Six Storehouses (liuku 六庫), discounting prices for Imperial Household Department’s office sales, and auctioning confiscated properties.Footnote 33 The crisis escalated in 1853 with the Imperial Household Department resorting to emergency metallurgical measures – melting three ceremonial golden bells into 8,503 golden bars totaling 27,030 taels – to offset military expenditures.Footnote 34 By September 1853, the Department’s fiscal collapse became institutionalized: It defaulted on its first Board of Revenue requestFootnote 35 and failed to meet salary obligations, compensating officials through a haphazard mix of silver, Board-issued paper notes (worth 100,000 taels), and overvalued copper coins amounting to 20,000 strings.Footnote 36 By year’s end, the Bullion Vaults of the Grand Storage Office (guangchusi yinku 廣儲司銀庫) held a mere 1,500 taels – a symbolic nadir reflecting the total erosion of the Qing imperial fisc.Footnote 37

The insolvency crisis of the Qing Imperial Household Department first emerged in 1853, when the Taiping Rebellion’s expansion into Yangzhou and Nanjing severely disrupted salt tax revenues from the Lianghuai region. Historically, this area had been pivotal to imperial finances: Between 1821 and 1851, the Lianghuai salt zone – spanning parts of Jiangsu, Anhui, Hubei, Hunan, Henan, and Jiangxi provinces – contributed annually between 400,000 and 500,000 taels through its “interest payments on imperial loans” (tangli yin 帑利銀), constituting the single largest revenue stream for the Imperial Household Department.Footnote 38 Originating during the Kangxi reign, the tangli yin system operated through Lianghuai salt commissioners loaning imperial silver to merchants, with the accrued interest funding administrative expenses of the imperial household. By 1748, these loans carried exorbitant monthly interest rates of 1.5% per tael of principal silver.Footnote 39 While the Lianghuai interest payments accounted for 20% of the imperial household’s revenue during the Qianlong period, their share surged to 50% under the Emperor Jiaqing. This over-reliance proved precarious as salt market volatility directly impacted imperial household finances. Declining merchant profits during the Jiaqing and Daoguang reigns led to systemic failures in meeting tax quotas.Footnote 40 The Lianghuai salt administration accumulated arrears of 1.84 million taels by 1850.Footnote 41 By 1857, annual revenues of Lianghuai had plummeted to about 200,000 taels – a mere 3.3% of the pre-1800 peak of 6 million taels.Footnote 42 The abrupt suspension of salt tax collection from this region – which had accounted for over 60% of the Privy Purse’s income – plunged imperial finances into immediate crisis.Footnote 43

The structural decline of Lianghuai salt revenue during this period derived not merely from the Taiping Rebellion’s disruption of Yangtze Delta distribution channels, but more fundamentally from the institutional expansion of lijin transit taxation – a fiscal mechanism that precipitated the systemic fragmentation of central salt monopoly revenues through provincial fiscal diversion and tax authority devolution. As documented by Zeng Guofan (曾國藩, 1811–1872) – the architect of Hunan Army’s victory over the Taiping and pioneer of the Self-Strengthening Movement – salt tax revenues from the Huai River basin had plunged to under 10% of pre-1850 baselines, a collapse he attributed to the “over-proliferation of lijin tax stations.”Footnote 44 The decentralized nature of lijin collection – varying widely by region – enabled local authorities to prioritize transit taxes over principal salt levies. North of the Huai River in 1864, for instance, salt lijin collections reached 4,725,195.723 taels, dwarfing the salt principal tax of 371,524.482 taels by a factor of twelve.Footnote 45 This fiscal predation transformed salt taxation from a centralized revenue stream into a fragmented system where auxiliary surcharges overwhelmed core imperial obligations.

As the second-largest revenue contributor to the Imperial Household Department, the Canton Customs Office was mandated to remit an annual quota of 300,000 taels to the Department’s administrative funds beginning in 1830. This fiscal arrangement, instituted by the Emperor Daoguang, aimed to offset chronic shortfalls in salt tax revenues from the Lianghuai region, which had suffered decades of delays and arrears. By contrast, Canton’s maritime tariff income remained comparatively stable, positioning it as a critical fiscal pillar for the imperial court.Footnote 46 However, systemic financial pressures escalated after 1853. The outbreak of the Taiping Rebellion forced the Canton Customs Office to prioritize emergency tax transfers to conflict-affected provinces, severely compromising its ability to fulfill obligations to the Privy Purse.Footnote 47 In March 1854, facing mounting arrears, the Imperial Household Department implemented quarterly installments of 75,000 taels to assert payment priority over other fiscal obligations.Footnote 48 This measure proved ineffective: Between February 1854 and February 1856, only 75,000 taels were delivered – a mere 12.5% of the adjusted quota – leaving a deficit of 525,000 taels.Footnote 49 The situation deteriorated further. By August 1858, cumulative remittances totaled just 180,000 taels.Footnote 50 Most alarmingly, unpaid obligations snowballed to 2.34 million taels by the end of 1863.Footnote 51 Between 1862 and 1865, Canton remitted a paltry 30,000 taels – a mere 10% of its mandated quota – forcing the Imperial Household Department to request an emergency 100,000-tael loan from the Board of Revenue in September 1865 alone.Footnote 52

Two systemic factors explain Canton’s fiscal failure. First, revenue diversion became endemic. In 1853 alone, Canton’s assigned fiscal obligations (1.08 million taels) already exceeded its annual income, with neighboring provinces intercepting funds en route to Beijing for military priorities.Footnote 53 Even the limited sums dispatched were frequently appropriated by transit provinces.Footnote 54 Second, the post-Opium War Treaty Ports System shattered Canton’s monopoly on foreign trade. The rise of the so-called “barbarian tax” (yishui 夷稅) – a transitional customs duty imposed by the Qing government on Western trade at treaty ports (1843–1854) – crowded out traditional customs revenues.Footnote 55 By the 1860s, chronic arrears in regular tariffs at the five treaty ports compelled the Board of Revenue to first relax repayment rules, then fully exempt delinquent payments – a de facto admission of institutional collapse.Footnote 56

The fiscal crisis of the Imperial Household Department extended beyond Lianghuai and Canton. Among its revenue streams, the Changlu salt administration was obligated to deliver an annual 140,000 taels. However, chronic defaults emerged: Arrears from Changlu totaled 800,000 taels between 1848 and 1858, escalating to one million taels by 1864. Similarly, Shandong Province accumulated tax arrears of 1.26 million taels by 1855.Footnote 57 Compounding these losses, the Taiping Rebellion disrupted the centuries-old ginseng trade. Prior to 1855, twenty-one Imperial Customs stations had contributed 120,000 to 130,000 taels annually through sales of surplus ginseng reserves from the Tea Store (chaku 茶庫) of the Imperial Household Department. With wartime disruptions terminating this revenue, the Imperial Household Department mandated the same offices to remit equivalent sums under newly devised “ginseng debt reparation” (tanhuan shenjin yin 攤還參斤銀) scheme.Footnote 58 Yet compliance proved dismal. By January 1859, only six stations – Kuiguan, Minhaiguan, Linqingguan, Huai’anguan, Hushuguan, and Tianjinguan – had fulfilled their obligations. Actual collections fell drastically short of the projected 160,000 taels, further destabilizing the Department’s finances.Footnote 59

The defaults by Lianghuai and Canton in remitting taxes to the Privy Purse triggered an immediate liquidity crisis for the Imperial Household Department. By January 1857, arrears had ballooned to 10 million taels, while the Department’s operational reserves stood at a precarious 1,800 taels in silver and 2,600 strings of copper coins. This dire shortfall forced the Imperial Household Department to secure an emergency loan of 500,000 strings of copper coins from the Board of Revenue to meet basic stipend obligations.Footnote 60 The fiscal collapse deepened throughout 1857. Annual expenditure requirements – 300,000 taels in silver and 500,000 strings of copper coins – stood in stark contrast to actual revenues of merely 70,000 to 80,000 taels. By December 1857, with reserves dwindling to 3,000–4,000 taels, the Imperial Household Department resorted to borrowing an additional 100,000 taels from the Board of Revenue, pledging repayment upon receipt of Canton’s overdue customs payments – a promise contingent on funds that never materialized.Footnote 61

Wartime fiscal constraints forced the Imperial Household Department to suspend critical imperial tribute systems. In May 1854, Taiping forces seized Jiujiang, paralyzing the Jiujiang Customs Office and halting its centuries-old duty of shipping royal porcelain to the court.Footnote 62 Simultaneously, the financing mechanism for Hangzhou’s silk tributes – traditionally subsidized by land-tax and salt revenues held in Zhejiang’s provincial treasury – collapsed when these funds were redirected to meet military expenditures in June 1854.Footnote 63 The crisis spread to Suzhou’s silk production. Facing depleted reserves, in June 1856, the throne authorized the unprecedented diversion of all 1856 customs revenues from Hushuguan Customs – a key Jiangnan tax node – to fund Suzhou’s silk tributes.Footnote 64

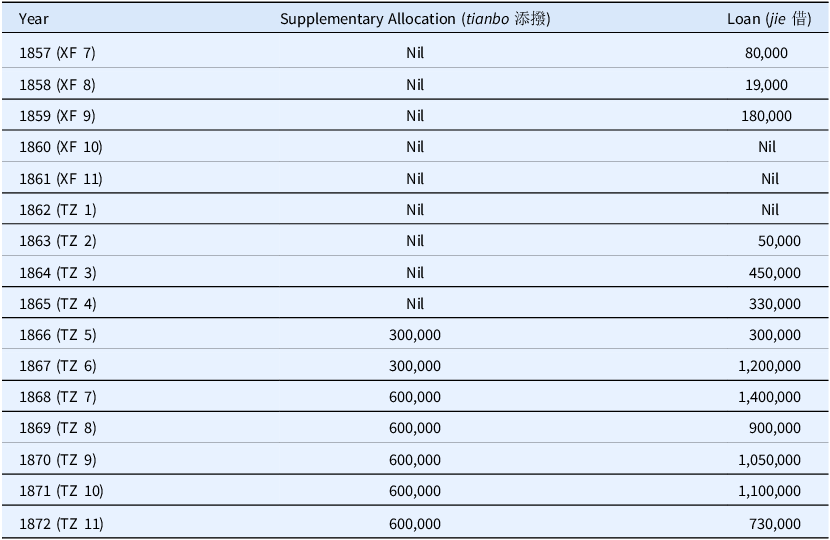

The fiscal collapse of 1857 compelled the Imperial Household Department to initiate unprecedented borrowing from the Board of Revenue (see Table 1), establishing a pattern of financial dependency that persisted until the dynasty’s final years. Although the Emperor Xianfeng authorized the initial 1857 loan as an “extraordinary measure” explicitly barred from serving as a precedent, post-Taiping fiscal realities rendered such restrictions moot. Chronic provincial tax defaults – particularly the diversion of land taxes and customs revenues by regional governors – forced the Imperial Household Department into recurring deficits, transforming emergency borrowing into systemic reliance.

Table 1. The imperial household department’s funding requests to the board of revenue, 1857–1872 (taels)

Source: QNDWH, pp. 241–42.

The post-taiping normalization of imperial fiscal extraction, 1864–1908

During the fiscal crisis precipitated by Canton Customs Office’s tax arrears in 1858, the Imperial Household Department petitioned the throne to institutionalize an annual 300,000-tael subsidy from the Board of Revenue as a permanent administrative fund. While the Board granted an emergency allocation of 100,000 taels to meet Imperial Household Department’s Mooncake Festival obligations, it deliberately deferred action on establishing the proposed recurring fund.Footnote 65 Subsequent fiscal maneuvers between 1858 and 1859 revealed systemic vulnerabilities: The Imperial Household Department repeatedly petitioned for supplementary disbursements before major festivals (Dragon Boat, Mooncake, and year-end), citing insufficient treasury reserves to cover ceremonial stipends.Footnote 66 Notably, a temporary respite occurred during 1861–1862 when the Department abstained from requesting funds. However, this fiscal reprieve proved illusory as structural liquidity deficiencies persisted. The crisis resurged dramatically with the Imperial Household Department demanding 50,000 taels in 1863 and escalating to 450,000 taels in 1864.Footnote 67 In 1865, the Department not only secured 330,000 taels directly from the Board but also unilaterally diverted 75,000 taels from Canton Customs Office’s revenues earmarked for the state treasury.Footnote 68

The chronic fiscal dependency exhibited by the Imperial Household Department between 1863 and 1864 culminated in a pivotal December 1865 conference with the Board of Revenue.Footnote 69 Negotiations yielded a landmark agreement: The Board authorized an annual 300,000-tael allocation from ten designated salt administrations and customs offices to establish a permanent operational fund for the Imperial Household Department, effective from 1866.Footnote 70 This institutionalized dependency, however, immediately exposed systemic revenue collection failures. By September 1866, the Canton Customs Office had remitted a mere 95,000 taels,Footnote 71 while other obligated salt and regional customs offices engaged in chronic noncompliance, either defaulting entirely or submitting partial payments.Footnote 72

Consequently, the designated local salt administrations and customs offices responsible for administering this levy – themselves operating under fiscal deficits – proved incapable of fulfilling the intended revenue targets. This systemic shortfall rendered the 300,000-tael special appropriation for the Imperial Household Department largely ineffectual. The fiscal crisis culminated in 1867 when the Department made an unprecedented demand for 1.2 million taels. This precipitated another inter-ministerial conference between the Board of Revenue and the Imperial Household Department, resulting in a landmark agreement to double the annual allocation to 600,000 taels. Significantly, an additional 300,000 taels were diverted from the “metropolitan remittance” (jingxiang 京餉) funds – fiscal resources that had been institutionally designated for central bureaucratic salaries through the Board of Revenue’s channels.Footnote 73

Between 1869 and 1873, the expenditure of the Imperial Household Department also witnessed a significant increase. In June 1869, the Imperial Household Department petitioned the Board of Revenue for 200,000 taels of silver to cover the costs of Emperor Tongzhi’s wedding ceremony.Footnote 74 Impatient with the intricate bureaucratic procedures that every formal fund requisition from the Board of Revenue entailed, in September 1872, Empress Dowager Cixi began issuing oral and informal decrees to the Board of Revenue through eunuchs to obtain additional funds.Footnote 75 From then on, apart from the fixed 600,000 taels and the regular additional fund requests before the Dragon Boat, Mooncake, and year-end festivals, the Board of Revenue was also compelled to submit silver taels for imperial construction projects via oral decrees conveyed by eunuchs.Footnote 76 Between 1857 and 1883, the total amount of silver taels transferred from the state treasury to the Privy Purse through these informal or oral requests by eunuchs reached 740,000 taels.Footnote 77

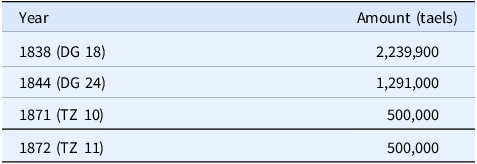

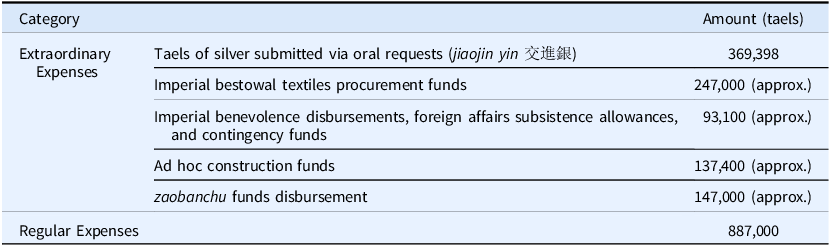

Confronted by mounting fiscal deficits and repeated funding demands from the Imperial Household Department, the Board of Revenue formally petitioned the throne in February 1873. In this memorial, the Board urged strict adherence to the principle of fiscal separation between imperial and state finances, demanding that the Imperial Household Department implement rigorous budgetary controls and expedite the collection of tax arrears.Footnote 78 The Emperor Tongzhi endorsed the Board’s position, particularly regarding the protection of the “four-tenths maritime customs surcharge” (sicheng yangshui 四成洋稅) – a dedicated fund established in 1860 for treaty indemnities and coastal defense. The throne explicitly prohibited any unauthorized diversion of this reserve by government agencies. However, the imperial rescript provided no substantive guidance on resolving the Imperial Household Department’s structural deficits.Footnote 79 In March 1873, the Department issued a rebuttal attributing its financial strain to systemic challenges: chronic tax collection failures on the part of the salt administration, customs offices, and imperial estates (see Table 2), as well as escalating court expenditures driven by ceremonial obligations (see Table 3). Notably absent was any acknowledgement of administrative inefficiencies within its own bureaucracy. The Department instead proposed inter-ministerial negotiations with the Board of Revenue to devise a revised fiscal framework.Footnote 80

Table 2. The bullion vaults of the grand storage office revenue comparison, Daoguang vs. Tongzhi Eras

Source: NWFZXD no. 748-071(TZ 12/2/23); QNDWH, pp. 263–64.

Table 3. 1871 imperial household department expenditures: a budgetary breakdown by category

Source: NWFZXD no. 748-071(TZ 12/2/23).

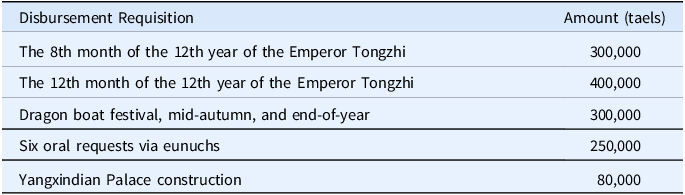

The following sequence of events between 1873 and 1874 underscores that imperial needs, whether for celebratory or funerary purposes, often took precedence, disrupting normal fiscal plans and the disbursement of funds to other state sectors. In February 1873, the Board of Revenue was still at a loss as to how to raise the funds demanded by the Imperial Household Department. Before they could find a solution, in April, the Emperor Tongzhi instructed the Board of Revenue to loan an additional 200,000 taels to the Imperial Household Department.Footnote 81 The Board of Revenue had no choice but to comply and provide the designated amount. Nevertheless, they seriously cautioned that imperial construction projects should be restricted. They proposed that the financial support for these imperial construction endeavors should be sourced from the Imperial Workshops (zaobanchu 造辦處) under the Imperial Household Department, instead of relying on the Board of Revenue.Footnote 82 Despite the Board of Revenue’s all-out efforts to resist the additional fund requests from the Imperial Household Department, it invariably had to meet most of these demands. This was achieved by reallocating funds originally earmarked for official salaries and military stipends. In 1873, apart from the regular annual quota of 600,000 taels, the Board of Revenue ended up transferring 1.33 million taels to the Imperial Household Department (see Table 4).

Table 4. Fiscal provisions from the imperial household department to the board of revenue: 1873 allocation records

Source: QNDWH, pp. 255–56.

The extensive renovation projects preceding Empress Dowager Cixi’s birthday celebration triggered a sharp escalation in court expenditures during 1874, prompting the Imperial Household Department to invoke historical precedents from established regulations to legitimize extraordinary funding requests. In February 1874, the Imperial Household Department submitted a request to withdraw 500,000 taels from the state treasury for palace construction projects, which received immediate imperial approval.Footnote 83 However, this routine transaction ignited a bureaucratic confrontation. In March 1874, the Board of Revenue presented an unprecedented memorial to the throne, identifying indiscriminate borrowing by the Imperial Household Department as the cause of the treasury’s chronic deficit. The Board formally requested imperial intervention to prevent further inter-departmental conflicts. The Emperor Tongzhi’s vermilion rescript dismissed these concerns with a terse directive: “No deliberation required. Expedite reimbursement immediately (wu yong hui yi, jin li su bo毋庸會議,謹力速撥).”Footnote 84 The dispute escalated in July when the Board of Revenue petitioned to abolish the controversial practice of oral fund requests transmitted through eunuch intermediaries. While acknowledging this informal system had historically operated within the Imperial Household Department’s internal affairs, the Board emphasized it constituted an unauthorized breach of statutory treasury procedures when applied to state finances. This memorial received no imperial endorsement, being returned without comment – a tacit rejection that underscored the throne’s prioritization of imperial prerogatives over fiscal governance.Footnote 85

A critical juncture occurred in August 1874 with the Imperial Household Department’s demand for 300,000 taels to finance Empress Dowager Cixi’s upcoming birthday celebration. The Emperor Tongzhi issued a special edict designating this expenditure as “urgent ceremonial preparations for the Imperial Dowager’s grand birthday celebration” (wanshou qingdian jixu banli zhi gong 萬壽慶典急需辦理之工), “incomparable to ordinary construction works” (fei xunchang gongzuo kebi 非尋常工作可比), mandating prioritized funding. The Board of Revenue hereby is commanded to expedite the allocation of 300,000 taels of silver without delay.Footnote 86 Faced with depleted reserves of mere 100,000 taels, the Board of Revenue was compelled to comply against its financial judgment by resorting to reallocating military stipends to fulfill this financial demand.Footnote 87

Between June and October 1874, a bureaucratic confrontation unfolded as the Board of Revenue and the Imperial Household Department engaged in protracted negotiations over the allocation of financial responsibility for palace construction costs. Under Qing fiscal protocols, construction expenses verified by the Board of Works (gongbu 工部) were routinely covered by the Board of Revenue, whereas projects directly supervised and audited by the Imperial Household Department fell under its own budgetary purview.Footnote 88 This established framework was challenged in May 1874 when the Imperial Household Department petitioned the Board of Revenue to assume responsibility for the Tuanhe Palace renovations, despite having conducted the project audit internally. Remarkably, the request received imperial endorsement through the emperor’s rescript approval.Footnote 89 The Board of Revenue mounted formal objections by reaffirming statutory auditing procedures for imperial constructions. This principled stance was nevertheless overruled by the throne.Footnote 90 The fiscal conflict culminated in October 1874 when the Board of Revenue’s renewed protest against funding allocations for the Old Palace restoration similarly failed, reaffirming imperial support for the Imperial Household Department’s fiscal claims.Footnote 91

The Emperor Tongzhi’s arbitrary support for the Imperial Household Department’s insatiable demands for funds drew severe censures from government officials. In 1873, Li Zongyi (李宗義, 1818–1884), the Governor-General of Liangjiang, counseled the imperial court to halt the restoration project of the Old Summer Palace, aiming to show respect for and heed the will of the people.Footnote 92 In January 1874, Bayang’a (巴揚阿, 1810–1876), then serving Jingzhou garrison commander, tried to persuade the emperor to defer the Old Summer Palace construction. He emphasized the critical fiscal circumstances, which were the result of escalating military expenses in the Southwest and the Northeast, combined with the flood in Zhili, and the draught in the Lower Yangtze region.Footnote 93 Despite the vehement opposition voiced by governmental officials, the Imperial Household Department remained undeterred in its pursuit of the required funds. Instead, these remonstrances only spurred the Department to resort to an ever-increasing array of justifications to rationalize its actions.

Scholars examining late-Qing fiscal centralization during early years of Emperor Guangxu’s reign (1875–1908) have observed more restrained imperial household spending behaviors.Footnote 94 However, due to chronic revenue shortfalls, the Imperial Household Department remained structurally dependent on extraordinary transfers from the Board of Revenue. Provincial tax arrears and systemic defaults by imperial monopolies – particularly salt administrations, customs offices, and textile bureaus – compelled the Imperial Household Department to employ three recurring fiscal strategies: 1) securing emergency loans from the Board of Revenue under the pretext of delayed tribute payments, 2) requesting discretionary write-offs of statutory Imperial Household Department obligations through accounting maneuvers, and 3) deferring debt repayments by citing external revenue deficiencies.

This dependency manifested through escalating operational crises. In September 1875, the Imperial Household Department borrowed 400,000 taels from the Board of Revenue to finance the ceremonial transfer of the Emperor Tongzhi’s coffin to Dongling Mausoleum, justifying the emergency allocation through outstanding tangli yin defaults by Zhili and Shandong provinces.Footnote 95 In October 1876, it shifted procurement burdens to the Board of Revenue when the imperial textile bureaus in Hangzhou and Suzhou failed to deliver court-mandated silk filaments.Footnote 96 By May 1892, the Department’s financial instruments had degenerated into cyclical accounting fictions. It formally petitioned for an indefinite suspension of deductions from its 600,000-tael fixed operating fund, thereby perpetuating a 209,297.56-tael debt obligation to the Board of Revenue through procedural deferral.Footnote 97

The dual ceremonial events of Emperor Guangxu’s 1889 wedding and Empress Dowager Cixi’s sixtieth birthday celebration in 1894 precipitated extraordinary financial burdens on the Qing imperial treasury. To finance Emperor Guangxu’s nuptials, the Imperial Household Department implemented an unprecedented three-pronged fiscal strategy. 1) Extraordinary appropriations: Repeated requisitions were made from the Board of Revenue, totaling millions of taels in special allocations.Footnote 98 Notably, between 1887 and 1889 alone, 5.5 million taels were diverted from the “metropolitan remittance” funds designated for capital expenditures.Footnote 99 2) Administrative cost-shifting: The Department systematically transferred ceremonial preparation costs to provincial authorities. A striking example occurred in September 1889 when the Canton Customs Office was mandated to procure ceremonial gold.Footnote 100 3) Decentralized procurement: Rather than utilizing established palace supply channels, provincial governments were compelled to provide specialized ceremonial provisions through ad hoc tributary demands. The 1894 sexagenary celebrations for Empress Dowager Cixi followed this financial pattern, with recorded expenditures reaching 5,308,834 taels.Footnote 101

During the late Qing period, the profligate expenditures of the imperial household systematically diverted state fiscal resources. To satisfy the Imperial Household Department’s perpetual funding demands, the Board of Revenue implemented supplementary taxation mandates that burdened provincial administrations while redirecting revenues from salt administrations and customs offices. In 1893 alone, the Department’s relentless requisitions compelled the Board of Revenue to establish a dedicated imperial fund of 500,000 taels – supplementing the existing 600,000 taels annual allocation established in 1868.Footnote 102 This systemic financial predation intensified through specific fiscal instruments. In May 1905, the Board of Revenue authorized an interest-free loan of 59,544.76 taels to cover ceremonial expenses and personnel allowances for Zhongzhengdian Buddhist Chapel staff and Imperial Guards, secured against future Taipingguan Customs Office’s receipts due by June 1906.Footnote 103 Furthermore, from 1891 to 1906, the Taipingguan Customs Office was mandated to remit 100,000 taels annually directly to the Imperial Household Department’s coffers – effectively converting maritime trade revenues into perpetual imperial subsidies.Footnote 104

During the final years of the Qing dynasty, the Imperial Household Department faced chronic fiscal deficits as the mandated annual transfer of 1.1 million taels from state coffers consistently failed to materialize in full or on time. This systemic shortfall compelled the Department to increasingly rely on high-interest loans from private remittance firms (yinhao 銀號) in Beijing. By 1892, accumulated principal and interest payments to these financiers had reached 250,000 taels, nearly exhausting the Department’s regular operating funds.Footnote 105 The situation deteriorated further in 1895 when the Department secured emergency loans totaling 1.039 million taels – 885,000 taels from the Hengli remittance firm and 154,000 taels from the Taiyuan remittance firm.Footnote 106 Such borrowing came at exorbitant rates averaging 7.4%. By 1897, nearly 90% of the Department’s expenditure depended on these usurious loans, marking a decisive shift in imperial financing mechanisms.Footnote 107 This desperate reliance on private capital markets brought an ironic resolution to the half-century power struggle between the Imperial Household Department and the Board of Revenue over fiscal allocations. Where once inter-ministerial battles had characterized imperial financial management, the Qing’s twilight years saw private bankers emerge as the monarchy’s de facto financiers – a dramatic paradigm shift underscoring the dynasty’s institutional decay.Footnote 108

Conclusion

The Taiping Rebellion’s catastrophic disruption of the Qing fiscal order exposed more than temporary resource depletion; it laid bare the inherent fragility of an imperial governance dialectic painstakingly calibrated over centuries. By obliterating the salt tax networks and customary fiscal channels that had sustained the imperial household’s financial autonomy, the rebellion precipitated systemic disintegration. The collapse of the Yongzheng-Qianlong era’s segregation between patrimonial and bureaucratic finances compelled the imperial household into parasitic reliance on coercive transfers from the Board of Revenue––a dependency that metastasized into institutional norm after 1857. Crucially, this fiscal symbiosis did not merely drain state coffers; it corroded the operational logic of Qing governance. The throne’s unfettered extraction through quasi-privatized mechanisms stifled adaptive fiscal innovation, entrenched patrimonial interests over bureaucratic efficiency, and locked the regime into a self-reinforcing cycle of institutional decay.

The fiscal crisis precipitated by the Taiping Rebellion did not generate institutional reforms under the Qing conducive to forming a modern fiscal state, but exacerbated liquidity constraints and entrenched premodern fiscal structures – consequences that I argue, partly stemmed from the regime’s lack of institutionalized checks on its monarchical expenditures. Comparative scholarship of state building in the early modern period reveals that European monarchs faced nearly permanent demand for fund to meet war expenditures and their inability to levy land taxes compelled them to negotiate power-sharing arrangements with elites through fiscal bargains.Footnote 109 For China, however, imperial regimes’ established capacity for land taxation insulated them from such fiscal pressures faced by European monarchs. This divergence proved institutionally formative. While European representative regimes subjected royal expenditures to public scrutiny – a process that gradually institutionalized fiscal accountability of the governments and redirected monarchical expenditures toward public-legitimated ends, the autocrats’ capacity to secure funds from state treasuries without requiring elite consensus deprived them of the necessary motivation to try various new institutional arrangements that would undermine their political powers but would potentially lead their regimes toward modern fiscal statehoods.Footnote 110

This study of the demise of imperial fiscal segregation system meticulously institutionalized during the Yongzheng-Qianlong era further exposes the deep irony inherent in an autocratic regime’s self-regulatory arrangements when divorced from institutionalized accountability frameworks. Facing severe liquidity crisis, the fiscal segregation arrangement proved utterly ineffective to curb monarchical expenditures. The Imperial Household Department’s post-1857 requisitions – framed not as temporary exigencies but as institutional entitlements, epitomized the Qing rulers’ capacity to unilaterally alter the fiscal segregation arrangements. Through systematic normalization of fiscal diversions of state funds to imperial coffers, the throne conflated imperial interests with state imperatives, thereby eroding the very possibility of a depersonalized, rule-bound fiscal regime. Thus, bereft of the institutions that could subject monarchical demands for funds under the public scrutiny, the systematic fiscal collapse precipitated by the Taiping-induced governance crisis failed to catalyze institutional reforms, but rather entrenched the prioritization of dynastic survival over the public good, leading to self-reinforcing institutional lock-in effects that further impeded China’s transition toward modern fiscal statehood.

Acknowledgments

I thank two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments. All mistakes are all mine alone.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant No. 20CZS036).

Competing interests

The author declares none.