Introduction

In building the now extensive body of scholarship on deliberative democracy, democratic theorists seem to have taken quite seriously Jürgen Habermas’ claim that ‘the central element of the democratic process resides in the procedure of deliberative politics’ (Habermas Reference Habermas1996: 296). In recent years, research on democratic innovations, the new institutions ‘specifically designed to increase and deepen citizen participation in the political decision‐making process’ (Smith Reference Smith2009: 1), has consolidated in an academic field of its own. Considerable scholarly attention has focused on the notion of the mini‐public; institutions ‘small enough to be genuinely deliberative, and representative enough to be genuinely democratic’ (Goodin & Dryzek Reference Goodin and Dryzek2006: 220). In the search for the ideal conditions to ensure the equality of participation or maximise the quality of deliberation, scholars have paid less attention to the outcomes of institutional innovations, without which no procedure can really be claimed to improve democracy. In this article, by uncovering alternative conjunctions of factors that link innovative institutional design and lawmaking, we hope to recall that Habermas’ search for the ideal procedure aimed at ‘the production of legitimate law through deliberative politics’ (Habermas Reference Habermas1996: 318).

Deliberative theory has its foundations in Habermas’ procedural concept of democracy, therefore assuming that legitimate decisions are the outcomes of the public deliberation of citizens. However, the presumption that quality of deliberation yields more democratic outcomes may be as misleading as the belief that democratic innovations, simply because they involve more citizens participating as equals, produce legitimate decisions. Normatively, good deliberation and equal participation may be necessary institutional design features to bring about more legitimacy in a world of increasing public distrust and political disaffection. But, empirically, this is not sufficient if democratic innovations are expected to solve the crisis of representation. In order to tackle democratic deficits, democratic innovations must also be effective.

Despite considerable research on the institutional design of democratic innovations, there are few studies on the outcomes engendered by the different designs, and almost no evidence of how institutional conditions constrain or enable those outcomes. Most research on the institutional design of democratic innovations has been concerned with issues related to the equality of participation and the quality of deliberation. The question as to when either or both are conducive to effective democratic outcomes has been almost neglected.

We test how different institutional design options may lead (or not) to effectiveness, measured by policy responsiveness (translation of citizens’ preferences into policy making). In order to do so, we will look into one of the purported most effective democratic innovations known to date: the National Public Policy Conferences (NPPCs) in Brazil. NPPCs stand out among democratic innovations in their claim to have impacted on the macro‐democracy level (Pogrebinschi & Samuels Reference Pogrebinschi and Samuels2014). Employing qualitative comparative analysis (QCA), we explore how various combinations of NPPCs’ institutional design features associate with agenda‐setting and the decision making of Brazil's legislature, resulting (or not) in lawmaking.

Our findings suggest that institutional design features such as high or low volumes of participation, high or low dispersion of deliberative fora, institutionalisation, the policy area at stake and strong or weak civil society influence can be related in different ways to NPPC's outputs and outcomes. In particular, we show that, contrary to what some critics of participatory democracy suppose, mass participation can indeed yield laws at the macro‐democracy level. A second relevant finding is that a low number of instances within a deliberative process is a necessary institutional design feature for effectiveness in certain circumstances, confirming expectations of deliberative democrats regarding restrictive requirements of good quality deliberation. We also found that the policy area that democratic innovations concern themselves with contributes to explaining their effectiveness. If decisions authored by citizens ensure democratic legitimacy, only their transformation into actual policy and law can ensure effectiveness. Without effectiveness citizens cannot be subject to the decisions they have authored, and democracy would remain a normative ideal.

Procedure x outcomes: The limits of democratic theory and case studies

With notable exceptions (Fung Reference Fung2006; Papadopoulos & Warin Reference Papadopoulos and Warin2007; Smith Reference Smith2009), few scholars have seriously considered how effectiveness should be taken into account in the institutional engineering of democratic innovations. Fung's (Reference Fung2006) ‘democracy cube’, for instance, is a geometrical illustration of how different institutional design options are more or less suited to produce particular outcomes. Drawing on case studies, Fung (Reference Fung2006: 73) claims that democratic innovations seeking to enhance effectiveness are likely to involve a small number of citizens, who would be willing to engage intensively due to a deep interest in the problems at hand. These mini‐publics would also suggest that the subject of deliberation, recurrence and monitoring are other institutional design features that may generate more information to officials, and therefore increase public action (Fung Reference Fung2003: 349).

Scholarship recognises that mini‐publics tend to be unable to impact the macro political system, and therefore rarely determine public policy. Goodin and Dryzek (Reference Goodin and Dryzek2006) surveyed diverse mini‐publics to ascertain how they may affect political decision making through the public sphere and representative institutions. They point to the British Columbia Citizen's Assembly as a case of a mini‐public ‘actually making policy’, although rejection of its recommendations by referendum implied no eventual policy change at all. The Danish Consensus Conferences and Texan Deliberative Polls are given as examples of mini‐publics’ recommendations ‘taken up in the policy process’, although this presumption relies on secondary reporting and not on direct congruence analysis of policy or legislation. Almost no information is given on exactly how institutional design features relate to policy outcomes, when they do exist.

With few exceptions, studies on democratic innovations focus on outcomes internal to the procedure and participants, and not on policy responsiveness. Many case studies have provided valuable qualitative evidence on how innovations have effects on matters like citizens’ empowerment (Baiocchi Reference Baiocchi2001), personal skills and civic competences (Grönlund et al. Reference Grönlund, Setälä and Herne2010) or better‐informed decisions (Fishkin Reference Fishkin2009). These works contribute enormously to empirical knowledge of how institutional innovations produce desirable consequences associated with a deepening of democracy. But epistemic and ethical outputs internal to innovations say nothing about their real outcomes and impacts on policy making.

Studies that do address political outputs are usually circumscribed to policy impact at the local level. For the most part these studies seek to assess effectiveness by measuring whether innovations have solved specific local problems, such as water pollution (Geissel Reference Geissel2009) or the delivery of community policing (Fung Reference Fung2006). Touchton and Wampler (Reference Touchton and Wampler2014) show how participatory budgets increase health care spending and decrease infant mortality rates in Brazilian municipalities. However, studies that aim at a more systemic approach, such as Parkinson's (Reference Parkinson2006) analysis of citizens’ juries’ involvement in health policy making in the United Kingdom, do not yet contain any substantive comparative assessment of effectiveness.

Comparing institutional designs is crucial to assessing their effectiveness. Ryan and Smith (Reference Ryan and Smith2012) call for a systematic comparative turn in the study of democratic innovations. A sub‐field that is constituted by ‘innovation’ suffers more than most from a methodological bias to favour case studies. We should necessarily compare institutions that appear innovative both with one another and with more traditional institutions of governance in order to understand their effect within political systems.

Deliberative democrats have rightly focused on how legitimacy can be drawn from procedurally correct decisions, but have failed to grasp that ‘government by the people’ (input legitimacy) is only meaningful as a ‘government for the people’ (output legitimacy), one which makes sure that ‘the policies adopted will generally represent effective solutions to common problems of the governed’ (Scharpf Reference Scharpf2003). Participatory democrats for their part have focused their concern on how failing representative institutions can be bypassed by innovative institutional designs to the detriment of considering their complementarity. If designs that achieve equal participation and good deliberation cannot ever engender effectiveness, there is little point in calling such innovations democratic.

Designing effectiveness: Institutional variation and outcomes

The few attempts to deal with the relation between institutional design and effectiveness of democratic innovations seem to suffer three main limits. First, they rely on secondary narrative accounts and do not directly and systematically investigate relations between process’ characteristics and outcomes achieved. Second, they are mostly restricted to case studies at the local level, lacking wider systematic comparisons. Third, they focus on outputs that take place within the process neglecting political outputs and outcomes at the macro‐level.

We show how different combinations of institutional design features (or their absence) may lead to more (or less) effectiveness, measured by responsive policy making. Our assumption is that an effective democratic innovation is one that will impact on policy either directly (when authorised by delegation or devolution) or indirectly through the activity of authorised institutions like the legislature or the public administration. Such impact can be gauged at different stages of the policy cycle. We assume that to be considered effective, a democratic innovation must directly or indirectly affect at least one of these stages. We expect that effectiveness is determined by different combinations of institutional design features (or their absence) and that relationships between input conditions and outcomes are likely to be multiple and conjunctural with a variety of designs having alternative effects in different circumstances.

We test this general expectation by looking at the NPPCs and their impact on the Brazilian legislature. The NPPCs consist of a series of simultaneous and subsequent instances of deliberative mini‐publics that link the local, the state and the national levels through chains of delegation involving civil society organisations (CSOs) and government representatives, as well as ordinary citizens and private stakeholders (Avritzer & Souza Reference Avritzer and Souza2013). Although they may not offer the cocooned spaces envisaged by some mini‐publics such as citizen's juries, typically NPPCs will alternate facilitated deliberation in small working groups where recommendations are prioritised, with larger plenary discussions that take place at the closure of each round. The policy impact of NPPCs has been maintained in several studies (Pogrebinschi Reference Pogrebinschi2013; Souza & Pires Reference Souza, Pires, Avritzer and Souza2013; Pogrebinschi & Samuels Reference Pogrebinschi and Samuels2014), but none have engaged in systematic comparative tests. Given that NPPCs are innovations specifically designed to provide inputs to policy making, we examine whether their purported outcomes can be explained by their institutional design features.

NPPCs are a national‐level democratic innovation. Their impact is expected mostly at this level, either in the shape of policies formulated and enacted by the national legislature or designed and implemented by the federal public administration. The federal executive implements the NPPCs, and thus some direct impact is expected in the federal administration. As we want to test whether deliberation is translated into lawmaking both at the agenda‐setting and decision‐making stages, we assume that effectiveness is indicated when policies drafted as bills or enacted as laws by the national legislature are congruent with, and therefore responsive to, NPPCs’ recommendations.

We look at how NPPCs influence both problem definition and policy formulation in the legislature, assessing how proposed and enacted legislation responds to the NPPC's recommendations. We will therefore consider the diverse political outputs and outcomes of the NPPCs. In order to systematically compare NPPCs and evaluate and elucidate the diverse conjunctions of the presence and absence of key conditions that link procedure to outcomes, we undertake a qualitative comparative analysis (QCA).

Fuzzy‐set QCA, as introduced by Ragin (Reference Ragin2000), provides a structured method for conducting set‐theoretic analysis in the social sciences, particularly where researchers are dealing with more than a handful of cases. While social scientists should be interested in correlation coefficients, they are also interested in necessity and sufficiency. Much of the causal interpretation and theorising that is traditional to arguments proffered by scholars of democratic institutional design has been instinctively set‐theoretic, underpinned by implication rather than covariation hypotheses (see Thiem et al. Reference Thiem, Baumgartner and Bol2016a). Hypotheses often consider conditions like mass participation, deliberation or civil society demand to be required or almost always required in order to produce or negate a given democratic outcome; and/or combinations of these conditions that always or almost always suffice to produce an outcome. Necessity and sufficiency are logical properties of set relations.

QCA has only recently been introduced to the subfield of democratic innovations research in the work of Ryan and Smith (Reference Ryan and Smith2012). While QCA requires good theory and case‐knowledge on the part of users to reduce risks of measurement error and model misspecification (see Thiem et al. Reference Thiem, Spöhel and Dusa2016b for a review of debates), QCA tools like truth tables and Boolean reduction are extremely useful for identifying parsimonious descriptions of combinatorial set‐relations across cases (Berg‐Schlosser & Cronqvist Reference Berg‐Schlosser and Cronqvist2005). The method holds particular promise for research in this field then, as it matures beyond small populations of distinct innovative case studies to cumulating knowledge across multiple comparable cases.

How outcomes relate to procedure: A qualitative comparative analysis of the NPPCs

Although the NPPCs have taken place under a variety of governments, they evolved after Brazil's re‐democratisation and significantly under the Workers’ Party's (Partido dos Trabalhadores, PT) many years in office. The election of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in 2003 prompted a vivid shift in the frequency and breadth of NPPCs. Lula introduced 28 new policy areas, raising the total number of issues deliberated through NPPCs to 40. Lula's eight years in office also sees a palpable increase in the number of policy recommendations arising from NPPCs (Pogrebinschi & Samuels Reference Pogrebinschi and Samuels2014).

With this intensification and variance in impact of policy recommendations, an opportunity for systematic comparison and a robust contribution to the general study of democratic institutional innovation presents itself. We aim at demonstrating that certain institutional design features of the NPPCs are necessary or sufficient for policy making in the legislature. We discuss our cases in the light of cross‐case findings in the final sections. Before moving to the analysis, the following sections make transparent the decisions involved in constructing a comparison of cases of NPPCs.

Cases and data

Our analysis focuses on the NPPCs that have occurred between 2003 and 2010, which is the period corresponding to Lula's two terms in office. As we are interested in the institutional design features that led NPPC's recommendations to be taken up by federal legislators, it is useful to hold the political environment relatively constant in the first instance.Footnote 1

Our data have been compiled using two distinct datasets. For constructing the influencing conditions, we obtained most data from figures compiled by the Institute for Applied Economic Research in Brazil (IPEA).Footnote 2 Despite our numerous efforts to improve the IPEA dataset on institutional design features of NPPCs, data on the five conditions of interest that we test in the models presented in this article remained missing in some of the 60 cases that take place in this time period. List‐wise deletion of cases with missing data has produced a final population of cases for analysis of 31. Errors leading to missing data records do not appear to be systematic (see Online Appendix B for analysis).

For constructing the outcomes, we have used Pogrebinschi's (Reference Pogrebinschi2010) dataset, which comprises the final recommendations from all NPPCs held between 1988 and 2010, as well as all legislative acts (bills introduced, laws and constitutional amendments enacted by the legislature) congruent with recommendations. A congruent legislative act is one that matches the preferences contained in the NPPCs’ final recommendations. For example, when the first NPPC on Youth, held in 2008, recommended that the youth be considered a subject entitled to rights, in 2010 the legislature enacted a constitutional amendment stating precisely that – this legislative act is considered to be congruent.Footnote 3 By counting congruent legislative acts, the dataset provides a proxy for policy responsiveness. Our data includes the congruent legislative acts from between January 2003 and October 2010. We note that this leaves less than 200 days for responses for some NPPCs that finished in early 2010. The dataset also leaves aside bills proposed and laws passed between October and December 2010. To accommodate this and ensure comparability, we exclude from our analysis cases whose final recommendations were produced after October 2009.

In the next section, we introduce our explanatory conditions and some relevant expectations. We then present two models investigating relations between conditions based on two separate outcome sets calibrated from the data on legislative responses to NPPC policy recommendations. In Online Appendix A we explain in detail how we calibrated our variables to represent sets of the hypothesised conditions as we understand them.

Outcome conditions

The two outcome conditions we analyse refer to different stages of the policy cycle, as well as to two moments of the legislative process.

Policy outputs

The first outcome condition seeks to explain when democratic innovations are effective in influencing the definition of policy in the legislature. If democratic innovations cannot yield authoritative final decisions, they can at least begin to sway the legislative process in the first instance by influencing agendas. We assume here that the NPPCs have an impact on the agenda‐setting stage of policy making. We calculated legislative bills that are congruent with recommendations of a given NPPC as a proportion of the total number of recommendations made by that NPPC. We then make a qualitative distinction between proportions of response that signify policy output and those that do not, as explained in Online Appendix A.

Policy outcomes

The second outcome of interest is the set of NPPCs that informed the formulation of policy in the legislature. Our assumption is that the impact of some NPPCs goes beyond agenda‐setting, and reaches the decision making stage of policy making. We aim to verify under what conditions NPPCs’ recommendations are enacted as laws and constitutional amendments, providing not only policy outputs, but also concrete outcomes.

Influencing conditions

Institutionalisation

We expect that NPPCs institutionalised over time may build networks and path dependence in channels of communication with the legislature. Policy makers may place greater trust in processes that have witnessed repeated incidence and built up learning and familiarity. Therefore, we expect that when the kinds of legitimacy afforded by mass participation of citizens and strong roles for civil society are combined with a build‐up of bureaucratic know‐how and trust in the process over time, this allows legislators the confidence to propose laws that were conceived in democratic innovations (E2).

However, NPPCs that have taken place a number of times may present a lower demand for new legislation in their specific policy area, and aim more at monitoring already enacted legislation. In addition, NPPCs that take place for the first or second time may deal with a relatively new policy area (like environment and minority rights), and therefore present more opportunities and demand for legislative action. We have to investigate alternate causation here. In particular, when NPPCs are supported by civil society actors to motivate large numbers of participants in newly opened policy areas that focus on redistribution and recognition we expect to see large numbers of recommendations passed into law by legislators (E3).

Redistributive issue

This set comprises NPPCs that are organised toward a policy area that deals with redistributive and recognition issues. We assume that variance in the subjects and stakes on which participation takes place may play a role in the policy process (Fung Reference Fung2003). We also know that different democratic innovations are seen to be more or less relevant and/or authoritative with regard to social redistribution or more thematic policy concerns (Smith Reference Smith2009). Following this literature, we expect that designs with high numbers of participants that focus on redistributive policies will be associated with both outputs and outcomes to an extent that other conditions lose their explanatory relevance (E4). We also expect that designs that focus on broader thematic policy areas that employ a small number of deliberative instances are associated with policy outputs and outcomes in a similar way (E5).

Civil society control of organising committee

This set comprises NPPCs where members of civil society make up the organising committee. The committee plays an important role in making decisions concerning the NPPC's rules and procedures, and can therefore significantly influence its process. We are particularly interested to ascertain if the presence or absence of a meaningful majority of civil society actors in the organisation of an NPPC is an INUSFootnote 4 condition in different paths to effecting legislative activity that is congruent with policy recommendations. It is possible that, depending on the degree to which other factors like high citizen participation or a high number of deliberative instances are present or absent, legislators are determined (or not) to act given the strong presence of civil society in the organising commission.

Mass participation

This set contains NPPCs that involve a critical mass of participants in deliberations across all levels of the process. In our dataset, the numbers of those who participate in an NPPC ranges from 10,000 to 524,461. Many theorists have argued that the combination of mass participation and deliberation is unfeasible (Fishkin Reference Fishkin2009; Przeworski Reference Przeworski2010), while others have argued that it may be sequenced in a democratic process in useful ways (Smith Reference Smith2009). Mass participation can signal to the legislature that there is a tangible constituency of support for change in a policy area. We have a strong expectation that high levels of participation may lend legitimacy to the democratic process and make it harder to ignore NPPC policy recommendations. In other words, there may be certain quantities of participation that when reached, influence decision making and therefore increase its democratic quality. This quality of mass participation may be necessary or sufficient to effect policy action.

Decentralised institutional design

This set represents the degree to which municipalities and other subsidiaries are involved in the first stage of the process. While each NPPC should involve a sequence of deliberations scaling up from local, to state, and then to national level, NPPCs are different in the extent to which this is mandated or encouraged in the organisational rules. Some policy areas have geographic/thematic niches. The sample comprises an NPPC on indigenous people's health, for example, which, due to the nature of the policy it addresses, does not have its first stages held in the municipalities, but rather within each of the different indigenous groups existent in Brazil. We have therefore used this number of ‘subsidiaries’ to measure the extent of participation in the first stage of the NPPC process. We aim at investigating whether a large spread of municipal/subsidiary first stages can signal more support for certain policies and therefore prompt higher legislative response. Similarly NPPCs can be designed with less spread to leverage more concentrated deliberation among affected populations.

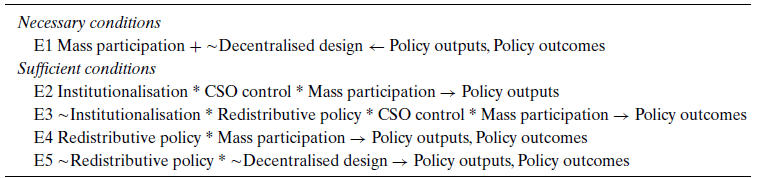

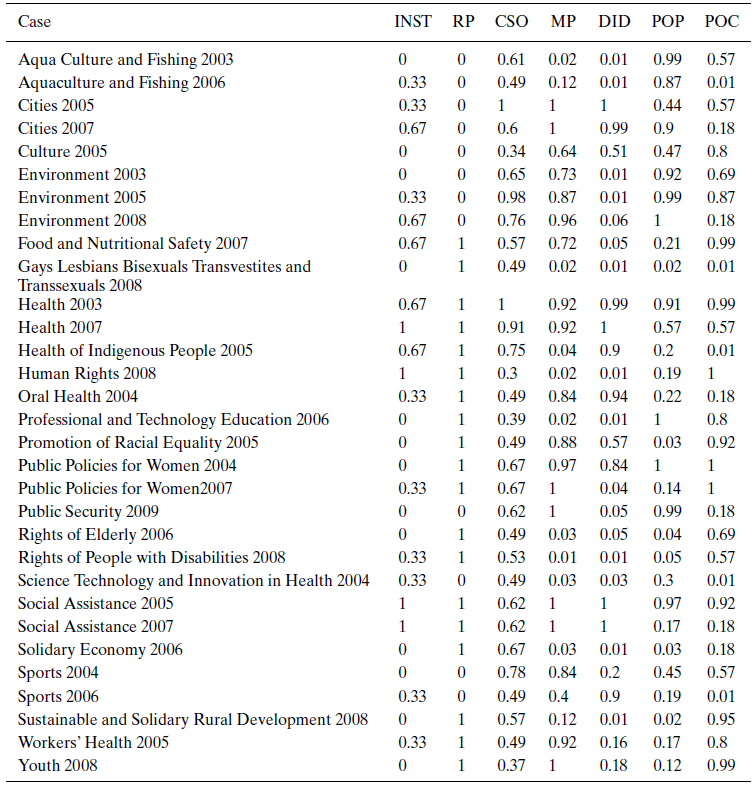

Table 1 summarises our expectations regarding set‐relations among conditions, while Table 2 provides the fuzzy‐set membership scores in each condition (set) for each case. Cases ascribed a score of ‘0’ have no membership in a set (did not display the condition). Cases with a score of ‘1’ have full membership (condition observed). Values between ‘1’ and ‘0’ represent various partial memberships in the set (condition is present to a degree).

Table 1 Summary of expectations

Notes: + refers to disjunction (read logical ‘OR’); * refers to conjunction (read logical ‘AND’); ∼ refers to negation (read logical ‘NOT’); ← may be read as ‘is necessary for’; and → may be read as ‘is sufficient for’.

Table 2 Fuzzy data matrix

Notes: Table 2 shows a fuzzy‐set data matrix of membership scores of cases for each condition used in our analysis based on the calibration procedure outlined in Online Appendix A as applied to the data presented in Online Appendix D. INST = Institutionalised policy conference; RP = Redistributive policy; CSO = Civil society control of organisation; MP = Mass participation; DID = Decentralised institutional design; POP = Policy output; POC = Policy outcome.

Analysis of necessary conditions

We first tested for necessary conditions using the inclusion algorithm as developed in the work of Bol and Luppi (Reference Bol and Luppi2013) and using the QCA package for R (Thiem & Dusa Reference Thiem and Dusa2014), taking a consistency/inclusion cut‐off of 0.95 and coverage cut off of 0.5. Necessary conditions point to a very high standard for causation in social research, and therefore it is conventional to ignore any findings that are not at least 90 per cent consistent or ideally 95 per cent consistent with a necessity superset/subset relation.Footnote 5 We find no single necessary conditions for either of our outcome measures. This first general finding seems consistent with the complex nature of the democratic innovation under analysis. Some NPPCs display enormous variation concerning the institutional design features investigated, so it seems plausible that no single condition can so regularly account for effectiveness.

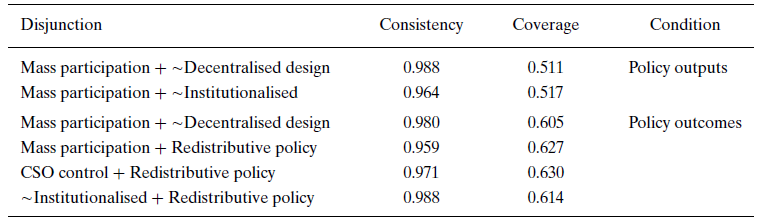

We find that some disjunctions (sometimes called ‘substitutable necessary conditions’ or SUINFootnote 6 conditions) are consistent at the 95 per cent level. Table 3 reports all disjunctions of two conditions that satisfy this criterion. We see that either mass participation OR a centralised institutional design is necessary for a NPPC to elicit responses from the legislature to a high proportion of its recommendations (consistency 0.988/coverage 0.511). This subset/superset relationship of necessity also seems to be confirmed for NPPCs to be authoritative in having their recommendations passed into legislation (consistency 0.980/coverage 0.605). When one of these conditions is absent, the other is almost always present in order for the outcomes to be achieved. In other words, there may be several different combinations of institutional design features that engender responsive policy making, but in all of them we will necessarily have either a high number of participants or a low number of deliberative instances. Where the NPPC is designed to have a greater number and spread of deliberative instances, there must be a high number of participants involved to engender policy making. Likewise, where there is absence of a high number of participants, there must be a small number of deliberative instances in order to achieve effectiveness.

Table 3 Necessary conditions for policy outputs and policy outcomes

Notes: Consistency threshold = 0.95; coverage cut off = 0.4. ‘+’ denotes logical OR.

This finding supports E1 in Table 1 and makes a lot of sense vis‐à‐vis debates in democratic theory. Either mass participation provides the strong support and legitimacy required for NPPCs to be effective (prompting policy making) or a more streamlined deliberation can be substituted in its place. The finding might prompt a rebuttal of any dogmatic insistence that mass participation cannot be effective or that deliberation of small groups is easy to ignore. In fact one or the other is almost always a necessary part of the explanation of the effectiveness of such democratic innovations.

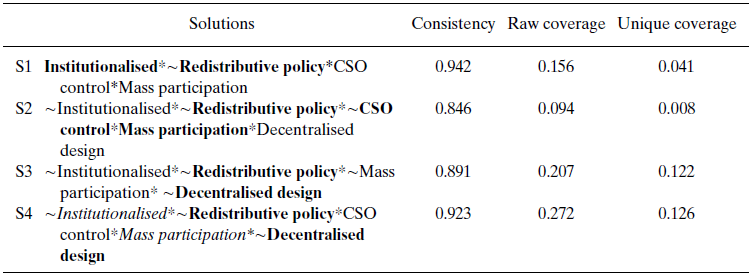

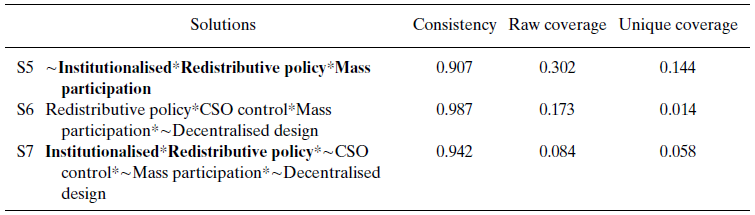

Analysis of sufficient conditions

As single necessary conditions are extremely hard to unearth in social research it is the sufficiency analysis that often provides the most interesting findings in QCA. In particular, sufficiency analysis provides alternative conjunctions of conditions associated with the outcome. Using Boolean minimisation, columns in Tables 4 and 5 show seven solutions, respectively, which are sufficient (or more precisely, almost always sufficient) for NPPCs to be effective (consistency threshold = 0.8/coverage threshold = 0.5). We present all solutions in the tables and discuss some of the key findings in detail. We organise the discussion by first considering if and how our remaining expectations for set‐relations in Table 1 are confirmed across the cases. We then move on to discuss the uncovering of other sufficient set‐relations that may help to explain effectiveness. We illustrate findings with case‐knowledge.

E2: [Institutionalisation*CSO control*Mass participation → Policy outputs]

Table 4 Sufficient solutions for policy output (policy definition, agenda‐setting)

Notes: Bold represents ‘core’ condition. Italics represent a substitutable condition due to multiple inessential prime implicants. In the latter case, consistency/coverage scores are shown for the model with the highest overall consistency and coverage which excludes ‘∼Institutionalised’ from solution 4. Non‐appearance of a condition from a solution implies irrelevance to the solution. Overall solution consistency = 0.879; coverage = 0.473.

Table 5 Sufficient solutions for policy outcome (policy formulation, decision making)

Note: Overall solution consistency = 0.916; coverage = 0.374.

We look first at Table 4, the NPPCs for whom a large proportion of their recommendations set the agenda of legislators, engendering what we call ‘policy outputs’. NPPCs take four alternative paths to this outcome. We compare E2 with S1: [Institutionalised*∼Redistributive policy*CSO control*Mass participation → Policy outputs]. E2 expected when NPPCs become institutionalised that they require a combination of high overall participation with strong civil society influence in order for a large number of their recommendations to be responded to in the legislature. S1 confirms this expectation, but adds nuance by confirming it only within the scope of non‐redistributive policy areas.

One illustrative case here is the third National Conference on Cities held in 2007. By the very nature of the policy under deliberation, this NPPC mobilised CSOs active in 3,277 municipalities and interested in setting the agenda of a much‐desired National Policy on Urban Development. Moreover, this NPPC was supported by the Council on Cities (ConCidades), a permanent national body connected to the Ministry of Cities, mostly composed of CSO representatives, which was created in 2004 with the aim of deliberating urban policy. The strong presence of CSO leaders at ConCidades has been reflected in the 2007 Cities NPPC's organisation. And most important to the outcome, the ConCidades played a strong role also after the NPPC, making sure its recommendations reached the legislature. During the NPPC, the organising committee collected and approved all recommendations of a legislative nature yielded by the 27 state‐level deliberations, separating them from those of an executive nature, such that they were sent directly to the appropriate branch of the government with the capacity to expedite effect (i.e., the legislature). The lesson here is that agendas on non‐redistributive issues are affected in line with strong sustained engagement and mobilisation.

E3: [∼Institutionalisation*Redistributive policy*CSO control*Mass participation → Policy outcomes]

Moving now to the NPPCs for whom multiple recommendations were converted into enacted legislation and engendered into what we call policy outcomes (Table 5), we can start to confirm our expectation that redistributive NPPCs which are not yet quite institutionalised require mass participation in order to have their recommendations enacted as legislation (S5; S6). But again these solutions add nuance to earlier expectations (E3). In the first instance, S5: [∼Institutionalised*Redistributive policy*Mass participation] suggests that civil society's role on the organising committee is less relevant than expected for this sufficient conjunction. When one examines the NPPCs that fit this solution well, it becomes clear how the absence of institutionalisation and the presence of mass participation can render civil society control redundant in the process. The first and second NPPCs on Policies for Women, the first NPPC on Promotion of Racial Equality and the first NPPC on Youth Policy all have in common the relative novelty of the policies issues that were dealt with, and a strong social mobilisation in support of the participatory process. These policies remained relatively under‐treated by Brazilian legislation before the respective NPPCs took place. The novelty of spaces where minority groups could express their preferences made room for an enormous, and previously repressed social demand. Voluminous engagement with diverse CSOs coming together meant that having a majority of seats in the NPPC's organising committees was not so relevant to the persuasion of legislators. The ‘Maria da Penha Law’ (Law 11.340/06), which turned domestic violence into a punishable crime, is congruent with many recommendations of the first NPPC on Policies for Women. The ‘Statute of Racial Equality’ (Law 12.288/10) transformed into law dozens of recommendations made by several racial minorities in the first NPPC on Racial Equality. The ‘Amendment of Youth’, inserted into the constitution clear recommendations of the first Youth Policy NPPC, including the demand for legislating a ‘Statute of Youth’, which was enacted in 2013 (Law 12.852) and comprises dozens of other recommendations of NPPCs on Youth Policy. The finding provides evidence that when the participatory process opens up democratic spaces through which large mobilisation takes place, citizens become the authors of significant numbers of laws.

E4: [Redistributive policy*Mass participation → Policy outputs, Policy outcomes]

In E4 and E5 we offered two more parsimonious expectations. Evidence for E4 is particularly inconclusive. The alternate conjunction S6: [Redistributive policy*CSO control*Mass participation*∼Decentralised design] indicates that the degree of institutionalisation of redistributive policy NPPCs is sometimes irrelevant to explaining policy outcomes in this context. However, this is only the case when civil society influence over the organisation of the conference is combined with mass participation in a low number of fora.

One case that illustrates these conditions is the third NPPC on Food and Nutritional Security. Nutritional and food security policies are a matter of clear national relevance in a country with high historical levels of poverty and hunger. This backdrop may reduce the need for many, dispersed local venues for deliberation. On complex redistributive issues it seems mass participation alone is not enough to effect legislative response. Yet, when such mobilisation occurs in a more condensed process ensuring CSOs will be allowed to set the rules, it may persuade the legislature to enact laws. Such persuasion has been indeed effective, as the legislature enacted an amendment inserting in the constitution the ‘right to nourishment’ among social rights (EC 64/10), in addition to several other congruent laws.

E5: [∼Redistributive policy* ∼Decentralised design → Policy outputs, Policy outcomes]

Some good evidence to support E5 is available for policy outputs, but not policy outcomes. The conjunction is core Footnote 7 to S3 and S4. Where recommendations come from a less diverse range of municipal and other subsidiary stages (∼Decentralisation), non‐redistributive NPPCs that combine being among first editions in that policy area with either the absence of mass participation (S3) or with strong civil society influence (S4) are sufficient for large proportions of their recommendations to reach legislative agendas. This was the case of the first and second NPPCs on Fishing and Aquaculture Policy in 2003 and 2006, respectively. Given the very specific nature of the policy under discussion, deliberations were not held at the municipal level, but only at the state and national levels. These NPPCs had only 27 instances of deliberation, which were organised around the discussion of a few well‐defined and circumscribed, less controversial topics. NPPCs on non‐redistributive issues can be effective in agenda‐setting where they have more streamlined designs, perhaps allowing more coherent formulations of policy proposals.

The QCA produces multiple conjunctions on which we might further remark, but we feel two particular findings are worth further exploration, to which we now turn.

Further findings: Policy issues

The absence of redistributive policies is an INUS condition, present in all sufficient conjunctions for policy outputs. There are two possible explanations. One is that redistributive NPPCs yield a much larger number of recommendations than NPPCs that deal with non‐redistributive issues. Redistributive policies are particularly salient for CSOs and their varied demands are usually reflected in long lists of policy recommendations. The average number of recommendations produced by redistributive NPPCs from our population is 58.3, while non‐redistributive NPPCs average 32. Redistributive NPPCs, in some cases, have a lower congruence rate because of their high number of recommendations, which facilitates cherry‐picking by politicians introducing recommendations to the legislature.

A second explanation is that redistributive/recognition policies tend to be prioritised by a limited number of parties, located closer to the left of the ideological spectrum. Policy recommendations on those issues may require the accompaniment of other circumstances in order to persuade legislators to propose bills supporting a large number of them.

The first NPPC on Public Policies for Women that took place in 2004 is an example of a NPPC focused on redistributive policies having been successful in setting the agenda of the legislature. This NPPC was organised with the aim of gathering inputs to the formulation of the ‘I National Plan of Women Policy’. Policy makers were already primed to consider many recommendations. This may explain why, when we compare cases, we find that all other cases with similar characteristics failed in setting the agenda of the legislature.

NPPCs on redistributive policy areas are an INUS condition for all causal paths explaining effects at the decision stage. While non‐redistributive policy conferences effectively set the agenda with a high number of congruent bills, they are unable to significantly impact the decision‐making stage and engender enacted legislation. The fact that redistributive policy issues are more easily converted into law may possibly be explained by the preferences of PT‐led coalitions in the Lula era to focus more on social policy (Samuels Reference Samuels, Domínguez and Shifter2013).

Further findings: Institutionalisation

Among alternative circumstances when NPPCs see laws passed congruent with their recommendations, one type of case is peculiar. Where there is a low number of participants, a highly centralised institutional design, and civil society is not influential in the organising committee, NPPCs on redistributive policy areas still impact political decision making when they are well institutionalised (S7). This solution has low coverage (raw = 0.84, unique = 0.058). The one good example we have of this type of case is the eleventh edition of the NPPC on Human Rights held in 2008. This is a particular case, because after many controversial and conflictual previous editions, this NPPC aimed specifically at revising the existing national policy on human rights. The National Policy on Human Rights 3, enacted by the executive, was the main result of the NPPC, almost paraphrasing many of its recommendations. As several recommendations explicitly demanded supporting legislative activity for implementation, the legislature was pressed into action. Given its specific aim of drafting the new human rights plan, this NPPC had no municipal stages, explaining its low decentralisation. The legislature (the Human Rights Commission of the Chamber of Deputies) organised this NPPC together with the federal executive, which may have reduced the influence of civil society in the organising committee, but, on the other hand, may have reduced barriers to the support needed for recommendations to become legislation. This case shows how participatory processes held repeatedly over time may experience institutionalisation within the representative policy‐making routines themselves, and therefore dispense with massive numbers of participants and civil society control of a process as legitimisers, as well as no longer requiring a largely decentralised deliberative process in order to be effective.

Conclusion

The search for the normative legitimacy promised by deliberative democracy has led democratic theorists to produce a considerable amount of work with the intention of designing a procedure that could reproduce, as close as possible, Habermas’ ideal speech situation. The belief that equal participation and good deliberation would ensure more legitimate and therefore more democratic decisions seem to have obfuscated an essential part of this equation: policy outcomes. While in the normative world of democratic theory a well‐designed procedure is sufficient to provide legitimacy to decisions, in the empirical world of real existing – and representative – democracies, an ideal institutional design would not bring much democratic quality if it were not to have an effect on legislation or legislative agendas.

This study is very much among the first of its kind in that it tries to associate the consequences of the institutional and environmental circumstances of democratic innovations with their effect on legislative activity. One important limitation of this study is we cannot, at the same moment, assess to what extent the legislative agendas we discuss may have been shaped by circumstances external to the NPPCs. With the available data we cannot give surety across cases as to whether participatory processes are only used to legitimate decisions made elsewhere. We hope that our findings can inspire research strategies that, for example, seek testimonies from legislators as to what motivated their responses. However, the level of congruence between recommendations of NPPCs and legislative actions, at the very least, suggests that this is less the zero‐sum game it is sometimes made out to be by radical participatory democrats. We also think that this research provides an important bridge between the work on how democratic innovations aim to achieve outcomes and the wider literature covering what conditions affect agendas and decisions in public policy. In other words, our work would be complemented nicely by further research that was able to compare relevant legislative effects among democratic innovations and other institutions/phenomena which are known to achieve such effects.

Despite these limitations, the work contains a number of important findings. The results show that, contrary to what critics of participatory democracy suppose, mass participation designs can indeed yield lawmaking at the macro‐democracy level. In addition to that, we showed that a compacted deliberative process is also an institutional design feature that can lead to effectiveness in certain circumstances, confirming deliberative democrats’ expectations regarding the restrictive requirements of a good quality deliberation.

We have also found that NPPCs that open up new non‐redistributive policy areas to participation can be effective in agenda‐setting when civil society takes a back seat in process organisation and there is mass participation in a decentralised institutional design. Non‐redistributive NPPCs are also effective where they have more streamlined designs, but once institutionalised, may require a significant participatory mandate to achieve high levels of legislative response.

On the other hand, we found that democratic innovations concerned with redistributive policies very often affect political decisions and see their recommendations passed into law. This happens when mass participation is combined with CSO support in less expansive designs. Nevertheless, the latter two conditions are irrelevant when innovations are a trailblazer in the policy area. Finally, institutionalised NPPCs rely on a great number of participants and dispersed local instances of deliberation for legitimacy in the eyes of legislators.

When it comes to designing democratic institutions, effectiveness should be as important as legitimacy. Otherwise the potential to solve democratic deficits and offer a way out of the crisis of representation is very limited.

Acknowledgements

We are greatly indebted to Tiago Ventura, who worked uncountable hours on the preparation of the raw data we use in this article, and also provided us with good insights in the process of data calibration and missing data analysis. We also thank Talita Tanscheit and Alessandro Amorim for helping us to complete the missing data searches. An earlier version of this article was presented at the American Political Science Association Annual Meeting, the European Consortium for Political Research General Conference and the Political Studies Association Annual Conference. We are grateful to the discussants and audiences for their comments. We also thank David Samuels, Graham Smith, Brian Wampler and the anonymous reviewers of this journal for their valuable criticism.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site:

Appendix A: Calibration of set membership values from raw data

Appendix B: Analysis of missing cases

Appendix C: Truth Tables

Appendix D: Raw Data Matrix (60 cases including those with missing values)

Appendix E: Replication code for R (also available as .R file)

Appendix F: Raw_data_file (31 cases following listwise deletion)