Introduction

Astrobiology is the study of the past, present and future of life on Earth or beyond Earth (Chyba and Hand, Reference Chyba and Hand2005). The origin and evolution of life, biosignature molecules and extraterrestrial life are the main subjects of astrobiology (Chyba and Hand, Reference Chyba and Hand2005). Extremophiles serve as model organisms for this research field and thrive in extreme habitats such as high or low temperatures, acid or alkaline media, high-salt concentration and high pressures (Duarte et al., Reference Duarte, Nobrega, Nakayama and Pellizari2012; DasSarma et al., Reference DasSarma, DasSarma, Laye and Schwieterman2020; Wu et al., Reference Wu, McGenity, Rettberg, Simoes, Li and Antunes2022). The ability of these microorganisms to adapt to extreme conditions makes them unique for astrobiology (Di Donato et al., Reference Di Donato, Poli, Nicolaus and Romano2018). Biosignature molecules are like the footprint of life in the extraterrestrial environment and can provide us with clues about the possibility of life. Scytonemin is one of the biosignature molecule and a notable biomolecule because of its unique ultraviolet (UV)-protective properties produced by extremophilic cyanobacteria. It may offer insights for the study of early life on Earth, especially in conditions mimicking early Earth or extraterrestrial environments (Varnali et al., Reference Varnali, Edwards and Hargreaves2009; Varnali and Edwards, Reference Varnali and Edwards2014a). Planets such as Mars and Venus are important candidates in astrobiology for studying the potential for extraterrestrial life. Both planets are of great interest because of their proximity to Earth and their intriguing environmental histories (Limaye et al., Reference Limaye, Mogul, Baines, Bullock, Cockell, Cutts, Gentry, Grinspoon, Head, Jessup, Kompanichenko, Lee, Mathies, Milojevic, Pertzborn, Rothschild, Sasaki, Schulze-Makuch, Smith and Way2021). Mars offers clues about life in a colder, drier environment, while Venus provides insight into how extreme environmental conditions might evolve on Earth-like planets. These studies help shape our understanding of planetary habitability and the search for life beyond Earth.

The scope of this study focuses on conducting a bibliometric analysis to explore research trends, collaborations and emerging themes in the fields of extremophiles and astrobiology. The analysis examines 309 research papers to identify key areas of scientific interest, research gaps and potential directions for future exploration. This analysis will provide a quick glimpse into extremophiles and astrobiology research in terms of gaps and trends of the field.

Methodology

Data were collected in November 2024 from Web of Science Core Collection (WOSCC) database with the keywords; ‘extremophile*’ OR ‘extreme microorganism*’ OR ‘extremophilic’ and ‘astrobiology’. These key words were selected since the research was based on the extremophile studies of astrobiology. The bibliometric analysis was carried out for the years between 2000 and 2024. This time period was chosen since most of the studies accumulated in this timeframe, and there were only 3 papers before 2000 starting from 1998. Notably, the term astrobiology became widely recognized during this period, particularly following the establishment of the NASA Astrobiology Institute at NASA Ames Research Center in 1998. This marked the formalization of astrobiology as a distinct interdisciplinary field, which likely contributed to the increase in related publications. Additionally, the limited number of studies prior to 2000 (only three papers between 1998 and 2000) highlights that substantial research activity began after the term’s adoption and institutional support for the field emerged.

Research papers, reviews and book chapters published in English, which is associated with review, were collected and examined to reveal interconnectedness of research topics, recent trends, timescale of the research area, relevant countries. The analysis was conducted using VOSviewer version 1.6.20 (https://www.vosviewer.com/) and RStudio version 2024.09.0. RStudio bibliometrix library (https://www.bibliometrix.org/home/) and Biblioshiny (https://www.bibliometrix.org/home/index.php/layout/biblioshiny) were used to visualize data (Aria and Cuccurullo, Reference Aria and Cuccurullo2017). Basically, the default parameters on the web interface were used for biblioshiny. However, the ‘Walktrap’ clustering algorithm was used for all clustering analyzes. The author’s keywords and five clusters were selected for keyword clusters. The edge size was two for countries’ collaboration. Web of Science Core Collection databaseFootnote 1 (Science Citation Index Expanded, Book Citation Index – Science, Emerging Sources Citation Index) resulted with 407 papers between 2000 and 2024. When review and book chapter were selected the number decreased to 311 article and by selecting only in English option 309 paper finally selected for analysis. According to the main information of analysis, annual growth rate of papers 12.16%, international co-authorships is 44.98%, author’s key word numbers are 969.

Results and discussion

Bibliometric analysis of extremophile research in astrobiology

Bibliometric analysis is a quantitative method used to assess the impact, development and trends of published academic literature. Bibliometric analysis provides insights into the interconnectedness of research topics, institutions, countries or individual researchers by examining various metrics associated with publications (Aria and Cuccurullo, Reference Aria and Cuccurullo2017). The research highlights the importance of extremophiles in understanding life in extreme conditions on Earth and the potential for life in space. Emerging technologies such as Raman spectroscopy and omics approaches are driving new insights. The evolving interest in topics such as biosignatures, planetary protection and Mars analogs emphasizes the central role of extremophiles in astrobiology and space exploration.

Annual scientific and citation production

Figure 1a shows scientific publication production by year, with the y-axis (vertical axis) representing the number of publications and the x-axis (horizontal axis) representing the years. The graph covers the period from approximately 2000 to 2024 and shows the change in the annual number of publications over time. After 2016, a steady upward trend starts, and this trend continues until 2024. 2024 seems to be the year when the highest number of publications was reached with 28 publications.

Figure 1. Annual scientific productivity (a) and citations per year (b).

Figure 1b shows the average number of article citations by year. The y-axis (vertical axis) represents the average number of citations, while the x-axis (horizontal axis) shows the years. The graph covers the period from the 2000s to 2024 and tracks the average number of times articles published each year are cited. Around 2009 and 2019, there are remarkable increases in the average number of citations, but these peaks were short-lived. For instance, the most cited paper ‘Living at the Extremes: Extremophiles and the Limits of Life in a Planetary Context’ garnered 313 citations was in 2019, similarly, ‘The Exiguobacterium genus: biodiversity and biogeography’ published in 2009 revived 166 citations, and ‘Diverse styles of submarine venting on the ultraslow spreading Mid-Cayman Rise’ with 129 citations was published in 2010. After 2020, there is a marked decline in the average number of citations, especially until 2023. 2023–2034 seems to be the year with the lowest average number of citations in the recent period. This is probably because publications are relatively new and have not yet had sufficient impact on citations.

Country collaboration

Figure 2a indicates collaboration of countries in the research field with the timeline. The size of circle indicates dominancy in the field. USA, England, Germany, Canada, the Netherlands and Spain nodes stand out as large-sized nodes with a high concentration of connections. These countries have connections with many other countries. However, countries such as Saudi Arabia, India, Russia and Poland seem to have contributed to this field recently, as can be seen from the color of the node. Türkiye has collaboration with only England.

Figure 2. Country collaboration (a) and map (b).

Figure 2b shows these relations on the world map and it provides a broad range of web observation. In this figure, some countries are colored in dark blue and some in light blue. This coloring indicates the intensity of cooperation and the leadership of a country in the field. In addition, the links between countries are shown with red lines and the length and thickness of the lines provide information about the strength of cooperation. The USA is shown in the darkest color, which means that it has the highest level of cooperation on the map. The USA has established links with many countries. This shows that the US plays a leading role in research projects and has extensive cooperation with different countries. Indeed, the USA has taken a pioneering role in the field of astrobiology and is recognized as the founding country of this field. By establishing the Astrobiology Institute in the late 1990s, NASA, especially, Ames Research Center increased interest in this field and directed research (Blumberg, Reference Blumberg2003; Race et al., Reference Race, Denning, Bertka, Dick, Harrison, Impey and Mancinelli2012). This leadership has placed the USA at the center of many international cooperation networks in the field of astrobiology and has enabled strong links to be established with other countries. This map clearly reflects the founding role of the USA in this field and its central position in global cooperation. There is a close network of cooperation within the European continent, especially among the countries of Western Europe. There are clear links between countries such as Germany, the UK, France, Italy and the Netherlands. This shows that European countries are tightly networked in their research projects and that cooperation takes place mostly at the regional level. On the map, South American and Asian countries are also linked to the USA and some European countries. For example, countries such as Brazil, India and China also contribute to research.

However, these countries do not have as intensive cooperation as the USA or European countries and are represented with fewer links. This may indicate that these countries play more of a secondary or supportive role in research.

Author’s keywords and research connections

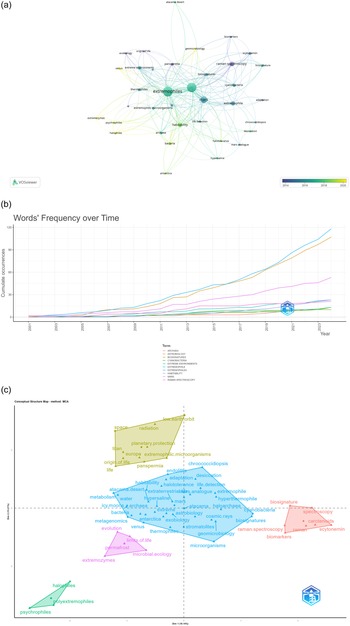

Figure 3a shows a keyword co-occurrence network map and node sizes and links represent the frequency with which the terms occur together in scientific literature. Node size indicates the frequency of use of a keyword. For example, large nodes such as ‘extremophiles’ and ‘mars’ are terms that occur more frequently in the dataset. Lines connecting nodes indicate the co-occurrence of terms. Thicker or more links indicate stronger or frequent co-occurrence of terms. The colors represent years of publication. As the largest node, the most used keyword is related to extremophiles. Mars has shown an increase as it is often associated with extremophile habitability studies. Habitability is another term frequently used in studies focusing on the potential for life under extreme conditions. Raman Spectroscopy stands out as a technique used in the study of extremophiles and biosignature molecules. According to timeline, Venus has recently begun to be studied. Likewise, geomicrobiology and extremozymes are the terms studied recently. According to map, the genus Chroococcidiopsis has been used as keyword frequently. Because, this group of cyanobacteria recognized for their ability to survive in extreme conditions (Baque et al., Reference Baque, de Vera, Rettberg and Billi2013; Fais et al., Reference Fais, Casula, Sidorowicz, Manca, Margarita, Fiori, Pantaleo, Caboni, Cao and Concas2024). These bacteria, which live in extreme environments such as deserts and poles, are characterized by their resistance to radiation, drought, high salinity and extreme temperatures (Cockell et al., Reference Cockell, Brown, Landenmark, Samuels, Siddall and Wadsworth2017). These abilities of Chroococcidiopsis have made it an important model organism in the field of astrobiology to investigate the limits of life and to study potential signs of life on Mars or other planets (Baque et al., Reference Baque, Verseux, Boettger, Rabbow, de Vera and Billi2016; Garcia-Gomez et al., Reference Garcia-Gomez, Delgado, Fortes, Del Rosal, Linan, Fernandez, Cabalin and Laserna2023; Fais et al., Reference Fais, Casula, Sidorowicz, Manca, Margarita, Fiori, Pantaleo, Caboni, Cao and Concas2024). These bacteria protect themselves from extreme environmental conditions by living just below the soil surface or in the cracks of rocks (Stivaletta et al., Reference Stivaletta, Barbieri and Billi2012; Cockell et al., Reference Cockell, Brown, Landenmark, Samuels, Siddall and Wadsworth2017). Thus, they constitute an interesting example for ‘extremophile’ studies, especially in biological trace research (Billi, Reference Billi2019).

Figure 3. Author’s keyword web (a), frequency over time (b) and keyword clusters (c).

Figure 3b shows key word frequency over time. Like co-occurrence network map, the term Extremophiles with the highest increase, reaches a cumulative frequency by 2023. As the second most frequently used term, Astrobiology is a trend topic. The term ‘habitability’ is another popular keyword that has increased over the years. Mars is frequently associated with extremophile habitability studies. The term ‘Biological Signatures’ is also on the rise.

Figure 3c shows factorial map (multiple correspondence analysis) of author’s keywords. This map visualizes relationships by grouping conceptual constructs or research topics in each field. The clusters shown in different colors on the map represent various sub-topics in the research field of astrobiology and extremophiles.

In the figure, five clusters have been revealed. Key Concepts of yellow cluster are ‘space’, ‘radiation’, ‘planetary protection’, ‘origin of life’, ‘Europa’, ‘Titan’ and ‘panspermia’ represents space and origin of life. This group focuses on concepts such as the origin of life, planetary protection and panspermia. These themes relate to studies that investigate how life originated in space or whether there is life on other planets as well as the philosophical and theoretical aspects of astrobiology. The exploration of icy moons such as Titan and Europa are important contributors to these topics (Tang, Reference Tang2005; Jehlicka et al., Reference Jehlicka, Edwards and Culka2010; Preston and Dartnell, Reference Preston and Dartnell2014). Dim 2 represents the vertical axis of the map and usually reflects more technical or specific topics. The yellow region located upwards in Dim 2 deals with the biological effects of the space environment. Concepts such as ‘radiation’, ‘low earth orbit’ and ‘extremophilic microorganisms’ represent research areas in astrobiology that express the biological effects of space and the need for protection. The upward trend in this axis draws attention to issues such as how to sustain life in space conditions and how factors such as radiation affect biological structures. For example, in a study, protective structures such as cortex and photo-protective pigments was tested on the resistance of the photobiont to UV-C (Javier Sanchez et al., Reference Javier Sanchez, Meessen, del Carmen Ruiz, Ga Sancho, Ott, Vilchez, Horneck, Sadowsky and de la Torre2014). In another study, black fungus Cryomyces antarcticus was subjected to simulated Mars and space conditions, including ultraviolet radiation (Pacelli et al., Reference Pacelli, Selbmann, Zucconi, Coleine, de Vera, Rabbow, Boettger, Dadachova and Onofri2019).

Key concepts of blue cluster (center) are ‘astrobiology’, ‘exobiology’, ‘exobiology’, ‘extremophile’, ‘habitability’, ‘cosmic rays’, ‘stromatolites’, ‘cyanobacteria’ and ‘biosignatures’. This cluster includes astrobiological research interested in extremophiles and their potential for habitability. For example, the adaptation of extremophile microorganisms to extreme conditions could be instructive in the search for the potential for life on planets such as Mars or Venus (Javaux and Dehant, Reference Javaux and Dehant2010; Preston and Dartnell, Reference Preston and Dartnell2014; Limaye et al., Reference Limaye, Mogul, Baines, Bullock, Cockell, Cutts, Gentry, Grinspoon, Head, Jessup, Kompanichenko, Lee, Mathies, Milojevic, Pertzborn, Rothschild, Sasaki, Schulze-Makuch, Smith and Way2021). In addition, the identification of biological signatures such as ‘biosignatures’ and ‘geomicrobiology’ (geomicrobiology) plays an important role in this research (Chacon-Baca et al., Reference Chacon-Baca, Santos, Miguel Sarmiento, Luis, Santisteban, Fortes, Davila, Diaz-Curiel and Grande2021; Maldanis et al., Reference Maldanis, Fernandez-Remolar, Lemelle, Knoll, Guizar-Sicairos, Holler, da Silva, Magnin, Mermoux and Simionovici2024). The blue cluster combines both theoretical (life detection, habitability) and applied (Mars-like environments, microbial diversity) aspects of extremophiles and astrobiology. Also, the blue cluster is at the center of the map, representing a conceptual cluster focusing on the fields of extremophiles and astrobiology. Dim 1 covers a wide range of research related to the survival of life in extreme conditions. Terms such as ‘habitability’, ‘life detection’, ‘extreme environments’ and ‘mars analogue’ raise questions about the sustainability of life on different planets. The central position of the blue region on the horizontal axis indicates that these topics are strongly related to other themes in astrobiology. Upward or downward placements on Dim 2 may reflect whether the topics are applied or theoretical. The blue cluster is located in the middle of Dim 2, indicating that it contains a balanced mix of both theoretical and applied aspects of the study of extremophiles and astrobiology. Concepts such as ‘Antarctica’, ‘hypersaline’ and ‘halotolerance’ indicate that extremophiles are studied in harsh environments on Earth and that these studies have direct application to astrobiology research (Musilova et al., Reference Musilova, Wright, Ward and Dartnell2015; Karan et al., Reference Karan, Mathew, Muhammad, Bautista, Vogler, Eppinger, Oliva, Cavallo, Arold and Rueping2020).

Key Concepts of Red cluster are ‘spectroscopy’, ‘biosignature’, ‘biomarkers’, ‘biomarkers’, ‘carotenoids’, ‘scytonemin’ and ‘raman spectroscopy’. This area deals with spectroscopy techniques for the identification of biomarkers and biological traces. Raman spectroscopy and the analysis of other biochemical components are particularly used in the identification of biomarkers and are of great importance in astrobiology. Biochemical compounds such as carotenoids and scytonemin can be used as biomarkers and are frequently analyzed in studies looking for traces of life on the planetary surface or in the atmosphere. The position of the red region on the right-hand side of Dim 1 may indicate that spectral analyses and biosignature detection constitute a more independent area than other themes of astrobiology. The position on this axis may indicate that the study of biosignatures requires a more technical investigation process than other thematic areas such as extremophiles or the origin of life. The upper positions of the red cluster along Dimension 2 indicate that this area is high-tech in terms of scientific research and observation techniques. This position reflects the fact that the detection of biosignals is done directly and with high-resolution spectroscopic techniques. It implies that complex techniques such as spectroscopy involve practical applications in addition to theoretical knowledge, and that this is addressed at advanced levels of astrobiological research. The terms ‘Raman spectroscopy’ and ‘spectroscopy’ refer to important methods used in astrobiology to identify chemical signatures of life (Edwards, Reference Edwards2007; Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Hutchinson and Ingley2012; Varnali and Goren, Reference Varnali and Goren2018). Raman spectroscopy is particularly suitable for identifying molecular structures and compositions and plays a critical role in the identification of biosignatures (Villar and Edwards, Reference Villar and Edwards2006). Terms such as ‘biosignature’, ‘biomarkers’ and ‘carotenoids’ (carotenoids) refer to chemical compounds that signal the presence of life or biological activities (Baque et al., Reference Baque, Hanke, Boettger, Leya, Moeller and de Vera2018). In particular, carotenoids are considered as biomolecules that can be used in remote sensing of traces of life (Rodriguez et al., Reference Rodriguez, Weber and Barge2024; Vitek et al., Reference Vitek, Ascaso, Artieda and Wierzchos2024). Terms such as ‘scytonemin’ refer to protective pigments produced by organisms living in extreme conditions (Varnali et al., Reference Varnali, Edwards and Hargreaves2009). Scytonemin protects against ultraviolet radiation and spectroscopic traces of such pigments are valuable as biomarkers (Varnali et al., Reference Varnali, Edwards and Hargreaves2009; Varnali and Edwards, Reference Varnali and Edwards2014b; Storme et al., Reference Storme, Golubic, Wilmotte, Kleinteich, Velazquez and Javaux2015). Thanks to spectroscopic techniques, potential traces of life have become remotely detectable on planetary surfaces or in atmospheres. This is considered an important step in the search for life on other planets. The terms in this region reflect the work being done to explore biosignatures, particularly on Mars and planets beyond.

Key concepts of green cluster are ‘halophiles’, ‘polyextremophiles’ and ‘psychrophiles’. This group includes studies that examine microorganisms that can survive in multiple extreme conditions. Polyextremophiles refer to organisms that can survive in more than one extreme condition (e.g., both cold and saline environments) (Bashir et al., Reference Bashir, Wink, Duller, Schwendner, Cockell, Rettberg, Mahnert, Beblo-Vranesevic, Bohmeier, Rabbow, Gaboyer, Westall, Walter, Cabezas, Garcia-Descalzo, Gomez, Malki, Amils, Ehrenfreund, Monaghan, Vannier, Marteinsson, Erlacher, Tanski, Strauss, Bashir, Riedo and Moissl-Eichinger2021). Psychrophiles are microorganisms that can survive at low temperatures and are important for research examining the possibility of life on cold planets such as Mars (Alcazar et al., Cid, Reference Alcazar, Garcia-Descalzo and Cid2010; Bendia et al., Reference Bendia, Araujo, Pulschen, Contro, Duarte, Rodrigues, Galante and Pellizari2018; Mosquera et al., Reference Mosquera, Ivey and Chevrier2023). The green cluster is in the lower left of the map and represents organisms adapted to the most extreme conditions of life, such as polyextremophiles and psychrophiles. This is a region where the most resilient groups among extremophiles have been studied and is critical in astrobiology research to understand extreme environments that could potentially harbor life beyond Earth. The left-hand side of Dim 1 indicates that these species can be considered a more independent area of research due to their unique adaptations to extreme environmental conditions. Polyextremophiles and psychrophiles form a focal point for studying survival strategies at the extreme limits of life. Their placement in the lower left region on the horizontal axis indicates that these species, with their resilience and specific adaptations, occupy a more extreme position than other research subjects.

Placement at the bottom of Dim 2 indicates that polyextremophiles and psychrophiles are investigated based on more applied and experimental studies. Polyextremophiles and psychrophiles provide a model for understanding potential life in harsh environments on other planets. These investigations are critical for exploring the potential for life on ice-covered planets or in extremely cold environments.

Key concepts of purple cluster are ‘limits of life’, ‘permafrost’, ‘extremozyme’ and ‘microbial ecology’. The limits of life and how microorganisms adapt to extreme conditions are the focus of the cluster. Permanent frost events such as permafrost are used as a model to investigate the limits of life on Earth and are important for understanding the potential for life in frozen areas such as the surface of Mars (Cockell et al., Reference Cockell, Schwendner, Perras, Rettberg, Beblo-Vranesevic, Bohmeier, Rabbow, Moissl-Eichinger, Wink, Marteinsson, Vannier, Gomez, Garcia-Descalzo, Ehrenfreund, Monaghan, Westall, Gaboyer, Amils, Malki, Pukall, Cabezas and Walter2018; Aszalos et al., Reference Aszalos, Szabo, Felfoldi, Jurecska, Nagy and Borsodi2020; Bashir et al., Reference Bashir, Wink, Duller, Schwendner, Cockell, Rettberg, Mahnert, Beblo-Vranesevic, Bohmeier, Rabbow, Gaboyer, Westall, Walter, Cabezas, Garcia-Descalzo, Gomez, Malki, Amils, Ehrenfreund, Monaghan, Vannier, Marteinsson, Erlacher, Tanski, Strauss, Bashir, Riedo and Moissl-Eichinger2021). Extremozymes refer to enzymes that can function in extreme conditions, and knowledge of how these enzymes work contributes to understanding the survival strategies of extremophiles (Karan et al., Reference Karan, Mathew, Muhammad, Bautista, Vogler, Eppinger, Oliva, Cavallo, Arold and Rueping2020; Gallo and Aulitto, Reference Gallo and Aulitto2024). Studies of organisms that can survive in extreme cold environments such as permafrost and adaptation mechanisms such as extremozymes that can function in these environments stand out. These enzymes function even at extreme temperatures, pressures or pH values and may be potential biomarkers in the search for extraterrestrial life.

The placement of the purple cluster further to the left on the horizontal axis (Dim1) indicates that research on the limits of life focuses on more fundamental biological or ecological adaptations than other areas of astrobiological study. These topics are considered in a context closer to the biological limits that support life in extreme conditions. The fact that it is located at the bottom of Dim 2 indicates that this research on the limits of life is based more on experimental and practical work. Laboratory and field studies to understand how microorganisms survive in extreme environments provide an important method for exploring the limits of life. This research contributes to the study of habitability on other planets through the discovery of biological limits that support life in the most extreme conditions on Earth.

The relevant sources

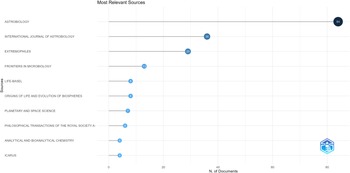

Figure 4 ranks the academic journals that have published the most articles on extremophiles and astrobiology. The sources with the most cited and relevant publications are shown on the bar chart on the right. Astrobiology has the highest number indicating that it is at the center of astrobiology research. International Journal of Astrobiology is ranking second in astrobiology-related studies. Extremophiles is the third at the study of life in extreme conditions. This list highlights the most important resources for researchers in the field of astrobiology and extremophiles, showing the journals that provide the bulk of the knowledge in the literature.

Figure 4. Relevant journal sources.

Thematic map and trend topics

Figure 5a is a map providing information about the place of subareas of research. Niche themes, motor themes, basic themes and emerging themes represent various aspects of extremophiles and astrobiology research and reflect the role of each area in scientific research and applications.

Figure 5. Thematic map (a) and trend topics (b).

Niche themes are topics with a high degree of development (intensity) but low degree of centrality (importance). They stand out as a highly specialized and narrow area of interest within extremophiles and astrobiology but have limited contribution to the wider research field. They usually involve topics that are intensively studied by a small or emerging community of researchers. Topics in this area of the map include specific microorganisms or physical processes such as growth, temperature, exiguobacterium and metabolism. Such topics contribute to the understanding of life in extreme conditions in specific environments, but they do not have a wide field of application. However, terms such as extremozymes and biomining have moderate intensity and centrality and are mostly applied in the fields of biotechnology and environmental engineering. It is concerned with how extremophiles can be used to extract metals from minerals. Although it is seen as a niche area next to astrobiology and general research on extremophiles, it could potentially play a role in future applications, especially in space mining.

Motor themes are topics with a high degree of both development and centrality. These themes have an important place in the research field and drive innovations and developments in extremophiles and astrobiology. These topics play a central role in scientific research and have a wide sphere of influence. Topics in this area on the map include extremophilic microorganisms, biosignatures, halotolerance, Europe (satellite) and Raman spectroscopy. These topics are important for investigating both extreme environments on Earth and potential habitable zones in space. In particular, the life strategies of extremophiles and the discovery of biological signatures are critical for astrobiology. Also, Atacama and lipid biomarkers are motor themes. The Atacama Desert is considered to be one of the most Mars-like places on Earth (Aszalos et al., Reference Aszalos, Szabo, Felfoldi, Jurecska, Nagy and Borsodi2020; Nagy et al., Reference Nagy, Kovacs, Igneczi, Beleznai, Mari, Kereszturi and Szalai2020; Preston et al., Reference Preston, Barcenilla, Dartnell, Kucukkilic-Stephens and Olsson-Francis2020). Due to its extreme aridity, high UV radiation and mineral-rich environment, it is of great importance as a potential analog site for astrobiology research.

Emerging or declining themes are topics with a low degree of both development and centrality. These areas include research topics that are either emerging or of declining interest. Such themes may gain popularity in the future or lose importance over time. This area of the map includes topics such as taxonomy, hot spring and fumaroles. While these topics provide important information in the field of basic science, they are less prominent in the exploration of extremophiles or the search for life in space. Developing technologies and research may make these topics interesting again.

Core/Basic themes are topics with a high degree of centrality but a low degree of development. These themes are fundamental and widely recognized topics that support a broad area of research in extremophiles and astrobiology. Although not of high interest, these topics provide a foundation for further research. Some of the topics in this area of the chart are planetary protection, radiation, Mars, astrobiology, stromatolites and microbial ecology. These topics form the cornerstones of astrobiology and are used in wide-ranging research such as space exploration, the origin of life and extraterrestrial habitable zones. Planets such as Mars and extreme conditions such as radiation play an important role in the search for extraterrestrial habitable environments.

Consequently, the study of extremophiles is important for understanding the possibility of life beyond Earth. In particular, studies investigating the potential for life to survive on planets such as Mars and Europa are intensifying. Technologies such as Raman spectroscopy are emerging as a critical tool for studying the chemical structure of extremophiles. This technology is used to identify biosignals and biomolecular signatures. The ability of extremophile microorganisms to survive in challenging conditions such as high temperature, acidic environments, salt water and radiation are the core studies of Astrobiology.

Figure 5b shows the visual summary of trends in the research area based on years. These trend topics can be useful for identifying shifts in research focus, especially for topics that bridge microbiology, environmental sciences and astrobiology.

Between 2004 and 2010, key terms in the field such as extraterrestrial life, origin of life, extremophiles and exobiology emerged (Rabbow et al., Reference Rabbow, Rettberg, Panitz, Drescher, Horneck, Reitz, Bernstein, Navarro Gonzalez and Raulin2005; Cuntz and Guinan, Reference Cuntz and Guinan2016). Between 2011 and 2015, terms such as biomarkers, panspermia, Raman spectroscopy, biosignaling, planetary protection, scytonemin, thermophiles, M

Mars analog started to increase (Edwards and Hargreaves, Reference Edwards and Hargreaves2010). In this era, with the increase in exploration missions to Mars, research on Mars analog sites and planetary protection measures have come to the fore. In the field of astrobiology, the potential of extremophiles to survive in extraterrestrial conditions was analyzed. In particular, studies on thermophiles and psychrophiles have increased. Studies on the detection of biosignals or biomarkers on Mars and other planets accelerated during this period (Baque et al., Reference Baque, Hanke, Boettger, Leya, Moeller and de Vera2018; Pacelli et al., Reference Pacelli, Selbmann, Zucconi, Coleine, de Vera, Rabbow, Boettger, Dadachova and Onofri2019).

Between 2016 and 2018, with the development of high-resolution sequencing technologies, more detailed and large-scale analyses of microbial communities have become possible. Extreme environments such as hydrothermal vents and high-salt lakes were studied to understand the adaptation mechanisms of these microorganisms. Planetary protection has gained importance in space exploration and the issue of the transport of life in space has become more discussed.

Between 2019 and 2021, especially with the increase in Mars exploration missions, astrobiology has become more popular and research to find life on Mars has become a priority. In environmental microbiology, the roles and biogeography of microbial communities in ecosystems have been further studied. This was especially studies aimed at understanding how biological cycles are regulated by microorganisms. Extremozymes began to be used in industrial processes and the applicability of these enzymes in biotechnology, pharmaceuticals and environmental sciences was further investigated (Kochhar et al., Reference Kochhar, Ibullet, Shrivastava, Ghosh, Rawat, Sodhi and Kumar2022).

Between 2022 and 2024, microbial Ecology and functional metagenomics, so, functional analyses of microbial ecosystems have gained importance in environmental microbiology. These studies have provided new perspectives on understanding the ecological roles of microbial communities and their adaptation to the environment. In the light of new data provided by Perseverance and other Mars missions, research on biosignaling and biomarker detection on Mars has increased. The biological safety of space samples, the development of planetary protection procedures, and the analysis of biomarkers for astrobiology are of great interest in the scientific community. The genetic structures and adaptation mechanisms of microorganisms that can survive in extreme conditions are being studied in more detail, which offers new opportunities for both basic biology and applied sciences. The discovery of phosphine in the atmosphere of Venus in 2020 sparked debate about possible signs of biological life in the planet’s cloud layers (Schulze-Makuch et al., Reference Schulze-Makuch, Irwin and Irwin2024). Therefore, Venus and biosignaling research has become a center of interest in both astrobiology and planetary science (Zorzano et al., Reference Zorzano, Olsson-Francis, Doran, Rettberg, Coustenis, Ilyin, Raulin, Al Shehhi, Groen, Grasset, Nakamura, Ballesteros, Sinibaldi, Suzuki, Kumar, Kminek, Hedman, Fujimoto, Zaitsev, Hayes, Peng, Ammannito, Mustin and Xu2023). This interest, which has changed over the years, emphasizes that Venus should be studied not only for its geological features, but also potentially from a biological point of view (Izenberg et al., Reference Izenberg, Gentry, Smith, Gilmore, Grinspoon, Bullock, Boston and Slowik2021; Kotsyurbenko et al., Reference Kotsyurbenko, Cordova, Belov, Cheptsov, Kolbl, Khrunyk, Kryuchkova, Milojevic, Mogul, Sasaki, Slowik, Snytnikov and Vorobyova2021; Limaye et al., Reference Limaye, Mogul, Baines, Bullock, Cockell, Cutts, Gentry, Grinspoon, Head, Jessup, Kompanichenko, Lee, Mathies, Milojevic, Pertzborn, Rothschild, Sasaki, Schulze-Makuch, Smith and Way2021; Kotsyurbenko, Reference Kotsyurbenko2023).

The development of omics technologies seems to contribute to the research field. Especially, shotgun metagenomics is the promising approach to reveal microbial dynamics as well as unclassified ones, gene pools of extreme environments.

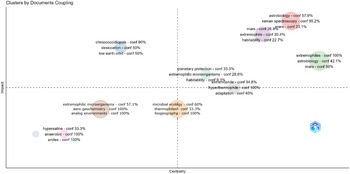

Figure 6 is a coupling map that shows clusters of topics based on document coupling. X-Axis (Centrality), represents the centrality or connectedness of each topic within the field, suggesting how core or peripheral these topics are. Y-Axis (Impact), likely represents the academic or research impact, possibly measured by citations or other metrics indicating influence. In such a coupling map, the percentage values (conf – confidence) indicate how strongly each topic or theme is related to the cluster to which it relates. Green Cluster with tags; ‘astrobiology – conf 57.9%’ and ‘extremophiles – conf 100%’ have high confidence percentages. The top right position shows that this cluster is quite centralized and has a high influence. This cluster covers mainstream topics related to space biology, life in extreme conditions (especially on planets like Mars) and astrobiology. These themes represent a popular area of research and are frequently linked to other topics. ‘The potential for life on Mars and research on organisms resistant to extreme conditions are the focus of this cluster. Red Cluster with tags; Raman spectroscopy - conf 95.2%’ has a very high confidence percentage. The location of the cluster is near the center and in a high-impact location. This cluster represents studies investigating the use of Raman spectroscopy to detect signs of life on the surface of Mars or in extreme environments. Raman spectroscopy has a close relationship with Mars exploration, as it is a common method for searching for signs of life, especially in minerals. This cluster emphasizes the importance of spectroscopic techniques as a powerful tool for the search for life on Mars. Pink Cluster with tags, anaerobic – conf 100%’ and ‘andes – conf 100%’ have very high confidence percentages. This cluster represents research on hypersaline (high salinity) and anaerobic (no oxygen) environments. It focuses on microorganisms living in such saline environments in specific geographical areas such as the Andes (Helena Albarracin et al., Reference Helena Albarracin, Pathak, Douki, Cadet, Dario Borsarelli, Gaertner and Eugenia Farias2012; Albarracin et al., Reference Albarracin, Kurth, Ordonez, Belfiore, Luccini, Salum, Piacentini and Farias2015). The lower left position indicates that these topics are more specific niche and therefore have a less broad impact and center. That is, this research is slightly outside of the main currents of the field but examines specific mechanisms of environmental adaptation. Blue cluster with terms desiccation and low earth orbit appear on the map near the top left corner. This cluster represents research on drought-resistant microorganisms, particularly Chroococcidiopsis. Such microorganisms have attracted research attention due to their ability to resist both harsh environmental conditions such as desiccation and the low gravity and high radiation conditions of the space environment. In this context, experiments in low Earth orbit provide important data to understand the resilience of these organisms (Billi, Reference Billi2019). The low centrality and impact of these terms suggests that desiccation and low Earth orbit studies are considered a more specific and niche area than other astrobiological and extremophilic research (Bryce et al., Reference Bryce, Horneck, Rabbow, Edwards and Cockell2015; Baque et al., Reference Baque, Verseux, Boettger, Rabbow, de Vera and Billi2016). Navy Blue Cluster with terms ‘planetary protection – conf 33.3%’ with relatively low confidence percentages. This cluster includes topics such as planetary protection (e.g., preventing accidental contamination by extraterrestrial life forms) and the ability to adapt to extreme conditions. The adaptation mechanisms of extreme life forms, such as hyperthermophiles (high-temperature-loving organisms) also feature here. The location close to the center means that these topics are relatively well connected to general literature and are often referenced in research.

Figure 6. Clusters by document coupling.

Conclusion

Astrobiology is a promising multidisciplinary research field focusing on understanding the origins, adaptations and potential existence of life on Earth and beyond. This dynamic field integrates biology, chemistry, geology, astronomy and planetary science to answer fundamental questions about life in the universe. One of the central areas of research involves extremophiles, which are capable of living in extreme conditions such as high salinity, extreme temperatures and acidic or alkaline environments, provided gaining insights into whether life could adapt to extraterrestrial habitats. Extremophiles not only serve as model organisms for potential extraterrestrial life on other planets but also help identify biosignature molecules such as scytonemin, which are chemical or physical indicators of life, and a UV-protective pigment produced by certain microorganisms. By studying these molecules, scientists can refine their search for life on other planets and moons, using both remote sensing technologies and in-situ exploration. Planetary habitability studies focusing on key celestial bodies such as Mars and Venus will deepen our understanding and offer a unique perspectives on life’s potential beyond Earth. Mars, often referred to as the ‘Red Planet’, is a primary target due to evidence of past liquid water, its currently arid and cold environment and its potential for hosting microbial life beneath its surface. Ongoing missions aim to uncover signs of ancient life and assess the planet’s habitability. Venus, on the other hand, provides a window into understanding the dynamics of extreme planetary environments. Despite its inhospitable surface conditions, with temperatures exceeding 450°C and a dense, carbon dioxide-rich atmosphere, recent studies suggest the possibility of microbial life in its temperate cloud layers. Investigating Venus not only enhances our knowledge of planetary evolution but also informs our understanding of Earth-like planets and their potential transformations under extreme conditions. As astrobiology continues to evolve, advancements in technology, including next-generation telescopes and robotic exploration, will further expand our ability to detect and study potential life in the universe. This interdisciplinary field holds the promise of answering one of humanity’s most profound questions: Are we alone in the cosmos?

Funding statement

This research received no external funding.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.