Introduction

Due to the rapid pace of market evolution, innovation plays a crucial role in firms’ operations (Santos-Vijande & Álvarez-González, Reference Santos-Vijande and Álvarez-González2007). Currently, organizational innovation culture represents a synthesis of the values, attitudes, beliefs, and ideas within an organization that rewards innovation (Dobni, Reference Dobni2008). A firm with a strong, innovative culture is likely to stimulate more innovative behaviours and facilitate radical innovation (McLaughlin, Bessant, & Smart, Reference McLaughlin, Bessant and Smart2008; Škerlavaj, Song, & Lee, Reference Škerlavaj, Song and Lee2010). Although there are studies on firms’ innovation behaviours and new product performance (Baker, Sinkula, Grinstein, & Rosenzweig, Reference Baker, Sinkula, Grinstein and Rosenzweig2014), as well as on organizational cultural factors and firm performance (e.g., Dobni, Reference Dobni2008), few studies explore the relationship between organizational innovation culture and new product performance from the perspective of emerging markets. Organizational innovation cultures in emerging markets, such as those in China and Vietnam, which exhibit high uncertainty and rapid change, may be different from those of developed countries (Wei, Samiee, & Lee, Reference Wei, Samiee and Lee2014). Thus, further investigation is needed with regard to the ways in which organizational innovation culture affects firms’ new product performance in these types of emerging markets.

In general, much less research has examined how organizational innovation culture interacts with other factors in firms’ product innovation. In this context, institutional environments and organizational cohesion constitute two main factors (Odom, Boxx, & Dunn, Reference Odom, Boxx and Dunn1990; Lu, Xu, & Liu, Reference Lu, Xu and Liu2009). First, institutional environments, such as the rules and requirements to which individual organizations must conform if they are to receive support and legitimacy (Scott, Reference Scott1995: 132), affect firms’ operations and innovation (Lu, Xu, & Liu, Reference Lu, Xu and Liu2009). Here, it is important to note that institutional environments in emerging markets are different from those in developed countries (Marquis & Raynard, Reference Marquis and Raynard2015). Second, organizational cohesion, which is defined as the strength of members’ desire to participate and remain in an organization in order to pursue common goals, plays a significant role in improving firm performance (Huang, Wang, & Lin, Reference Huang, Wang and Lin2011). Nevertheless, few studies examine the roles of institutional environments and organizational cohesion in the relationship between organizational innovation culture and firms’ new product performance.

Based on the gaps in the existing literature, this study examines the impact of organizational innovation culture on new product performance, which further enriches the organizational culture research by providing a multidimensional theoretical framework. Second, this study examines the moderating effect of institutional environments on the specific relationship between organizational innovation culture and firms’ new product performance in China and Vietnam, thereby extending institutional theory in the context of emerging markets. Third, this study investigates the moderating effect of organizational cohesion on the relationship between organizational innovation culture and new product performance, which thus extends organization theory in innovation management research.

Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

Organizational culture is defined as ‘the pattern of shared values and beliefs that help individuals understand organizational functioning and thus provide them norms for behaviour in the organization’ (Deshpande & Webster, Reference Deshpande and Webster1989: 4). Previous research highlights organizational culture as a vital driver of organizational innovation (e.g., Stock, Six, & Zacharias, Reference Stock, Six and Zacharias2013; Naranjo-Valencia, Jimenez-Jimenez, & Sanz-Valle, Reference Naranjo-Valencia, Jimenez-Jimenez and Sanz-Valle2017). Organizational innovation culture represents an environment, a culture, or a spiritual force that drives value creation (Buckler, Reference Buckler1997), thereby exerting an influence on firms’ new product performance (McLaughlin, Bessant, & Smart, Reference McLaughlin, Bessant and Smart2008). Moreover, an organizational culture that is supportive of innovation represents flexible values, which may affect firm performance by increasing product innovation (Lægreid, Roness, & Verhoest, Reference Lægreid, Roness and Verhoest2011; Stock, Six, & Zacharias, Reference Stock, Six and Zacharias2013). Overall, organizational innovation culture is important for firms with regard to gaining superior new product performance.

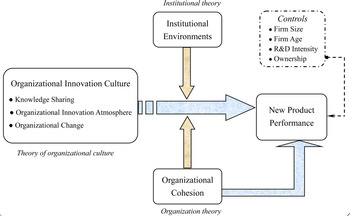

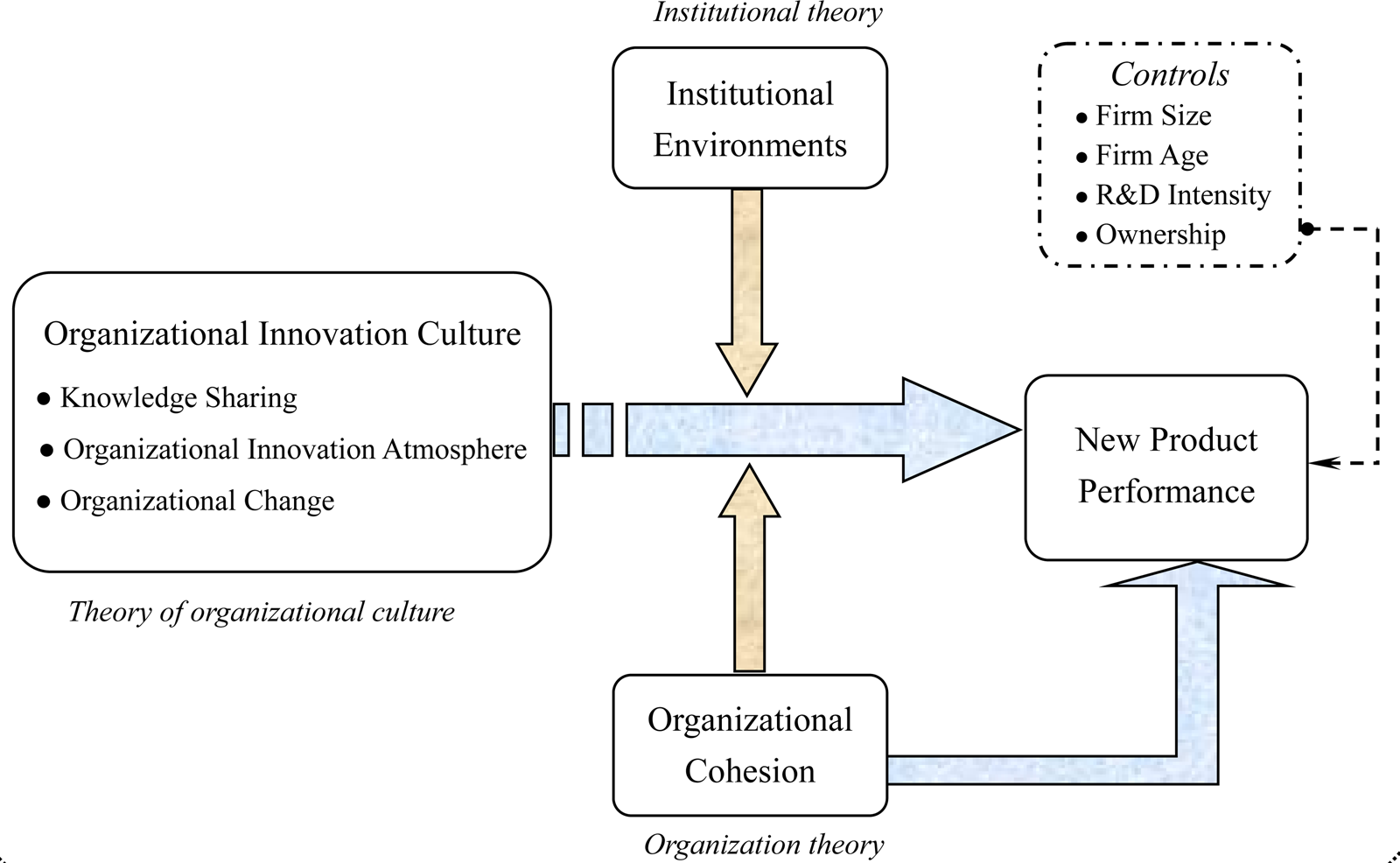

Manufacturing firms in emerging markets face complicated and dynamic environments (Lau, Yiu, Yeung, & Lu, Reference Lau, Yiu, Yeung and Lu2008). A good institutional environment, an innovative culture involving sharing and cooperation, and high cohesion provide substantial benefits for firms (Spencer, Reference Spencer2003; Lu, Xu, & Liu, Reference Lu, Xu and Liu2009; Salas, Reference Salas2015). Based on the close links between organizational innovation culture, institutional environments, organizational cohesion, and new product innovation (Odom, Boxx, & Dunn, Reference Odom, Boxx and Dunn1990; Lu, Xu, & Liu, Reference Lu, Xu and Liu2009), and building on the recognition that firms in emerging markets face a unique culture and set of circumstances (Wei, Samiee, & Lee, Reference Wei, Samiee and Lee2014), we aim to integrate organization theory and institutional theory to explain how institutional environments and organizational cohesion affect firms’ organizational innovation culture and, consequently, their innovation output. Thus, we propose the model in Figure 1 as a way for firms to achieve superior new product performance.

Figure 1. Theoretical framework

Organizational innovation culture

There are some studies examining the characteristics or dimensions of innovation culture within organizations (Dobni Reference Dobni2008; Stock, Six, & Zacharias, Reference Stock, Six and Zacharias2013). Lemon and Sahota (Reference Lemon and Sahota2004) argue that organizational culture includes a firm's general atmosphere, values, knowledge structures, organizational structure, and so on. Dobni (Reference Dobni2008) argues that an innovative culture is seen as a multidimensional context, including the intention to be innovative, the infrastructure to support innovation, and the environment to implement innovation. Ali and Park (Reference Ali and Park2016) indicate that innovative culture refers to ‘a set of shared assumptions, values, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours of organizational members that could facilitate the creation and development of new product, services, or process innovation’ (p. 1671). Regardless of the different emphases placed on the various definitions by scholars, the core concept can be summarized as a synthesis of values and ideas within a firm that aims to reward innovation, encourage risk-taking, engage flexibility and change, inspire innovative climate, and promote knowledge sharing. Thus, according to previous studies (Lemon & Sahota, Reference Lemon and Sahota2004; Dobni, Reference Dobni2008; Ali & Park, Reference Ali and Park2016), and considering the special traits of emerging economies in which the characteristics of industries are different from those in the developed countries (Lau et al., Reference Lau, Yiu, Yeung and Lu2008), we examine three elements of organizational innovation culture: knowledge sharing, the organizational innovation atmosphere, and organizational change.

The first dimension, knowledge sharing, denotes the willingness of individuals to share their knowledge with others within the organization (Grant, Reference Grant1996; Gibbert & Krause, Reference Gibbert and Krause2002). Knowledge sharing, as a means of effective access to knowledge acquisition, is critical to knowledge creation and to improving an organization's innovation performance (Vaccaro, Parente, & Veloso, Reference Vaccaro, Parente and Veloso2010; Bhatti, Zaheer, & Rehman, Reference Bhatti, Zaheer and Rehman2011; Estrada, Faems, & de Faria, Reference Estrada, Faems and de Faria2016). The second dimension, the organizational innovation atmosphere, refers to the shared perceptions among members with regard to their work environment, including policies, procedures, and practices that support innovation (Wallace, Edwards, Paul, Burke, Christian, & Eissa, Reference Wallace, Edwards, Paul, Burke, Christian and Eissa2016). A supportive atmosphere can affect individuals’ knowledge-sharing attitudes and behaviours (Matić., Cabrilo, Grubić-Nešić, & Milić, Reference Matić, Cabrilo, Grubić-Nešić and Milić2017), thus contributing to stimulating employees’ innovation thinking and improving firms’ competitive advantages and innovation capacities (Amabile, Conti, Coon, Lazenby, & Herron, Reference Amabile, Conti, Coon, Lazenby and Herron1996; Arnetz, Lucas, & Arnetz, Reference Arnetz, Lucas and Arnetz2011; Fainshmidt & Frazier, Reference Fainshmidt and Frazier2017). The third dimension, organizational change, refers to organizational members’ shared resolve to implement change and their shared belief in their collective capability to do so (Weiner, Reference Weiner2009). Changes should be anchored in the organizational culture (Oakland & Tanner, Reference Oakland and Tanner2007). An organizational culture that is proactive about change can help the firm understand market dynamics and make internal adjustments in order to improve organizational innovation and gain remarkable competitive advantages (Tey & Idris, Reference Tey and Idris2012; Zhu, Wittmann, & Peng, Reference Zhu, Wittmann and Peng2012; May & Stahl, Reference May and Stahl2017).

Organizational innovation culture may strengthen a firm's ability to produce more innovative products (Khazanchi, Lewis, & Boyer, Reference Khazanchi, Lewis and Boyer2007; Stock, Six, & Zacharias, Reference Stock, Six and Zacharias2013). This is especially important in emerging markets, where firms face complicated and dynamic environments that are more turbulent than those in the developed economies (Lau et al., Reference Lau, Yiu, Yeung and Lu2008). Typically, firms with good organizational innovation culture – including knowledge sharing, organizational innovation atmosphere, and organizational change – perform better (Arnetz, Lucas, & Arnetz, Reference Arnetz, Lucas and Arnetz2011; Bhatti, Zaheer, & Rehman, Reference Bhatti, Zaheer and Rehman2011; May & Stahl, Reference May and Stahl2017). Initially, firms can enhance their innovation performance by creating a knowledge-sharing culture (Spencer, Reference Spencer2003). Following this, an organizational innovation atmosphere can significantly affect firms’ new product performance (Arnetz, Lucas, & Arnetz, Reference Arnetz, Lucas and Arnetz2011). To capture more market opportunities, employees in firms with an innovative atmosphere share what they know and make reforms to adapt to the market or to lead by innovation (Škerlavaj, Song, & Lee, Reference Škerlavaj, Song and Lee2010). Furthermore, by implementing organizational change, firms can move from their current state to a desired, future state to increase their effectiveness and sustainable competitiveness (Deshpande, Reference Deshpande2012; May & Stahl, Reference May and Stahl2017).

Overall, a company's innovation-oriented culture can provide a competitive advantage by increasing the emphasis on innovation, fostering receptiveness to new ideas, and promoting product innovation, thus positively affecting firm performance (Kleinschmidt, De Brentani, & Salomo, Reference Kleinschmidt, De Brentani and Salomo2007; Stock, Six, & Zacharias, Reference Stock, Six and Zacharias2013). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1

The organizational innovation culture of a firm is positively related to its new product performance.

Institutional environments

As institutions are defined as the regulative, normative, and cognitive structures that regulate and constrain human activities in order to provide stability and meaning for social behaviour, an ‘institutional environment’ relates to the levels of an institution's development and stability (Wu & Chen, Reference Wu and Chen2014). Institutional environments play important roles in supporting the effective functioning of the market mechanism (Meyer, Estrin, Bhaumik, & Peng, Reference Meyer, Estrin, Bhaumik and Peng2009). In particular, as emerging markets are often characterized by high levels of government intervention, lack of legal protections of property rights, and underdeveloped markets (Peng, Reference Peng2003; Wu & Chen, Reference Wu and Chen2014), good institutional environments can provide well-developed institutional contexts with more transparency and less asymmetry with regard to information (Lu, Xu, & Liu, Reference Lu, Xu and Liu2009), thereby allowing organizational innovation cultures to function effectively. Therefore, the institutional environment may affect a firm's new product performance by moderating the effectiveness of the organizational innovation culture.

Although both China and Vietnam increasingly moved from central economic planning to a market-oriented approach during the 1990s, there are some differences in the two countries’ institutional environments (e.g., their political environments and government policies) (Islam, Reference Islam2008; Fforde, Reference Fforde2009). Consequently, under different institutional contexts, we may find that the relationships between organizational innovation culture and new product performance are different between the two countries. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2

The relationship between organizational innovation culture and new product performance is moderated by institutional environments, and this relationship is stronger for firms in China than for firms in Vietnam.

Organizational cohesion

The level of organizational cohesion refers to the degree of trust, cooperation, and friendship within an organization (Andrew, Kacmar, Blakely, & Bucklew Reference Andrew, Kacmar, Blakely and Bucklew2008). Generally, interrelated activities based on collective consciousness result in organizational effectiveness (Man & Lam, Reference Man and Lam2003). Given that strong cohesion creates a sense of groupness and increases members’ loyalty and identification with the organization (Friedkin, Reference Friedkin2004; Zahra, Reference Zahra2012), a high level of cohesion can help firms perform significantly better (Salas, Reference Salas2015).

Firms can also benefit in other ways from high cohesion (Hirunyawipada, Paswan, & Blankson, Reference Hirunyawipada, Paswan and Blankson2015). For example, the shared cognition and understanding may enhance the organizational innovation culture among employees (Odom, Boxx, & Dunn, Reference Odom, Boxx and Dunn1990). Second, a high level of cohesion can promote organizational learning, which, in turn, encourages technical and administrative innovation (Montes, Moreno, & Morales, Reference Montes, Moreno and Morales2005). Third, high cohesion can improve a firm's new product performance by enabling members to achieve a sense of mutual commitment to the new product idea, thereby developing a strong feeling of belonging to the firm (Hirunyawipada, Paswan, & Blankson, Reference Hirunyawipada, Paswan and Blankson2015), which may moderate the impact of organizational innovation culture by either reinforcing or contradicting its role (Mach, Dolan, & Tzafrir, Reference Mach, Dolan and Tzafrir2010). Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3a

The level of organizational cohesion is positively related to a firm's new product performance.

Hypothesis 3b

The relationship between organizational innovation culture and new product performance is moderated by the level of organizational cohesion, such that the relationship is stronger for those with higher organizational cohesion.

Methods

Sample

The data were collected via a survey with the sampling process as follows. The questionnaires were administered in Chinese and Vietnamese and then translated into English by scholars competent in these languages and with relevant research experience in this subject area in these two countries. To avoid cultural bias, we attempted to detect any misunderstandings that might have arisen from the translation work. Moreover, before the formal investigation, 30 firms were selected to participate in a pretest. Based on the results of the pretest, we improved the questionnaire. In addition, we carried out rigorous training for the investigators participating in this survey to ensure that they had a clear understanding of the purpose and the processes of this study. For the research pool, we considered the study population to be all large, medium, and small firms selected from manufacturing industries. We pulled the sample frame from a list of manufacturing firms taken from two science parks in Shanghai and a Vietnamese economic portal in Ho Chi Minh City, which share some common features, including similar industries (e.g., food manufacturing, textile and garments, chemical products, and electronic and telecommunications), company sizes, and government support. Shanghai and Ho Chi Minh City are two important cities for their respective countries, which can be considered representative of each nation's economy. In addition, the sampled firms are representative of the companies that are formally registered in each respective country. Using a stratified random sample method based on the size (four size types) and industry category (manufacturing sectors), a total of 1,000 questionnaires were provided to manufacturing firms located in China and Vietnam by field survey and email (700 Chinese firms and 300 Vietnamese firms). To improve the validity, all respondents were either senior managers (e.g., managing directors or chief executive officers) or middle managers (e.g., business managers or product managers). Of the 1,000 questionnaires that were distributed, we received 433 valid responses, including 331 from Chinese firms (47.29% response rate) and 102 from Vietnamese firms (34.00% response rate), for a total response rate of 43.30%.

Since the samples were drawn from two countries, it was necessary to test the differences between the two sources to determine whether the subsamples could be merged. An independent sample t-test for the two sources revealed that there was no significant difference between the two subsamples (p > .05), and thus we could merge them for the analysis. Moreover, given that the use of self-assessments for variables in the survey might raise concerns regarding common method bias (CMB), particular methods were used to reduce CMB. First, in the survey process, the respondents were told that the questionnaire was anonymous. Second, we located questions concerning the independent variables and dependent variables in different areas of the survey instrument. Third, Harman's single-factor test was used to test for CMB. The results showed that the first cumulative explanatory factor was 42%, thereby revealing that CMB was not a concern. Furthermore, a t-test of the valid and invalid questionnaires indicated that none of the t-values were significant, so we determined that non-response bias was also not a concern.

Measures

Independent variables

Organizational innovation culture, which is defined as a synthesis of values, attitudes, beliefs, and ideas that reward innovation within an organization, is operationalized at the levels of knowledge sharing, organizational innovation atmosphere, and organizational change, all of which are beneficial to firm innovation. Based on prior studies (Hu, Horng, & Sun, Reference Hu, Horng and Sun2009; Vaccaro, Parente, & Veloso, Reference Vaccaro, Parente and Veloso2010; Liu, Keller, & Shih, Reference Liu, Keller and Shih2011) and interviews with managers, knowledge sharing is measured by four items: (a) the level of information exchange between employees, (b) the level of emphasis placed by managers on employees’ knowledge-sharing behaviours, (c) the level of willingness to share new ideas with others, and (d) the level of channels available to facilitate employee communication. Additionally, based on prior research (Gray, Reference Gray2001; Hunter, Bedell, & Mumford, Reference Hunter, Bedell and Mumford2005; Arnetz, Lucas, & Arnetz, Reference Arnetz, Lucas and Arnetz2011) and interviews with managers, organizational innovation atmosphere is typically measured by four items: (a) the level of spirit of adventure shown by an organization's members, (b) the level of freedom afforded to an organization's members when they are working, (c) the level of emphasis on innovation in members’ daily work, and (d) the level of innovation that is regarded as an important element of a firm's strategy. Further, based on earlier work (Weiner, Reference Weiner2009; Deshpande, Reference Deshpande2012; Heyden, Fourné, Koene, Werkman, & Ansari, Reference Heyden, Fourné, Koene, Werkman and Ansari2017) and interviews with managers, organizational change can be measured by four items: (a) the degree and duration of change in organizational structure or processes, (b) the degree of employees’ willingness to effectuate change, (c) the degree of employees’ shared belief to implement change, and (d) the degree of employees’ enthusiasm for change. Respondents in this survey were asked to indicate the importance of these indicators to their firms in terms of innovation on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘1 = very low’ to ‘5 = very high’.

Organizational cohesion is operationalized as the degree to which information sharing and cooperation occur among departments and employees (Carron & Brawley, Reference Carron and Brawley2000; Mach, Dolan, & Tzafrir, Reference Mach, Dolan and Tzafrir2010). Based on the similarities of cohesion at different levels (e.g., at the team, group, or organization level) (Huang, Wang, & Lin, Reference Huang, Wang and Lin2011) and drawing on the findings of previous studies (Carron & Brawley, Reference Carron and Brawley2000; Man & Lam, Reference Man and Lam2003; Mach, Dolan, & Tzafrir, Reference Mach, Dolan and Tzafrir2010), we measured organizational cohesion using five indicators: (a) the level of information sharing among different departments, (b) the level of mutual support and cooperation between an organization's members, (c) the level of the innovative environment, (d) the degree to which employees are respected by senior managers, and (e) the degree to which failure is tolerated within an organization. Respondents were asked to indicate the importance of the five indicators to their firms in terms of innovation on a 5-point Likert scale from ‘1 = very low’ to ‘5 = very high’.

Institutional environments, defined as the levels of institutions’ development and stability (Wu & Chen, Reference Wu and Chen2014), are operationalized at the levels of the political environment, government policy, and market and legal environments (Lu, Xu, & Liu, Reference Lu, Xu and Liu2009; Zeng, Xie, & Tam, Reference Zeng, Xie and Tam2010). In recent years, both China and Vietnam have experienced rapid political, economic, and institutional changes, which have been accompanied by relatively underdeveloped product markets. Thus, China and Vietnam represent both emerging and transition economies, thereby providing a suitable context for exploring the role of institutional environments. Based on the characteristics of emerging markets and drawing on the findings of previous studies (Lu, Xu, & Liu, Reference Lu, Xu and Liu2009; Zeng, Xie, & Tam, Reference Zeng, Xie and Tam2010), an institutional environment is measured through three indicators, which are seen as common features of the institutional environment of emerging economies: (a) the stability of the political environment and political reforms, (b) the incentives offered through government policies for firm innovation, and (c) the effectiveness of market and legal environments with regard to firm innovation. Each indicator was measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘1 = very bad’ to ‘5 = very good’. A higher score indicated a better institutional environment. As the use of these items to measure institutional environments is consistent with previous studies on institutional environments in the context of emerging and transition economies (e.g., Zeng, Xie, & Tam, Reference Zeng, Xie and Tam2010; Qian, Cao, & Takeuchi, Reference Qian, Cao and Takeuchi2013), these subjective measures are likely to capture the institutional environments in emerging economies.

Dependent variables

Numerous studies have examined the choice of new product performance measures. Following Fischer, Diez, and Snickars (Reference Fischer, Diez and Snickars2001), Romijn and Albaladejo (Reference Romijn and Albaladejo2002), and Zeng, Xie, and Tam (Reference Zeng, Xie and Tam2010), new product performance was measured using three indicators: (a) the proportion of sales represented by new products, (b) the new product index, and (c) the modified product index. To provide an anchor for the respondents to answer the questions, they were asked to indicate the extent to which their firms had changed over the past 3 years. The items were assessed using the following 5-point Likert scale: (1) ‘<0%’, (2) ‘0–15%’, (3) ‘15–30%’, (4) ‘30–50%’, and (5) ‘>50%’.

Control variables

Firm size, firm age, research and development (R&D) intensity, and ownership were used as controls: (1) firm size was measured by the number of employees (1 = ‘<50’, 2 = ‘50–300’, 3 = ‘301–2000’, and 4 = ‘>2000’) and turnover (1 = ‘<10 million’, 2 = ‘10–30 million’, 3 = ‘30–300 million’, and 4 = ‘>300 million’); (2) firm age was measured by the number of years that a company had been listed with the local Industrial Bureau at the end of the reporting year; (3) R&D intensity – including the intensity of R&D personnel and R&D expenditures – was measured using the number of R&D employees divided by the total number of employees, and the annual R&D expenditures divided by total sales, respectively; and (4) the type of ownership was measured by respondents choosing one of four choices: private enterprises (PEs), state-owned enterprises (SOEs), foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs), or collectively run enterprises (CREs).

Results

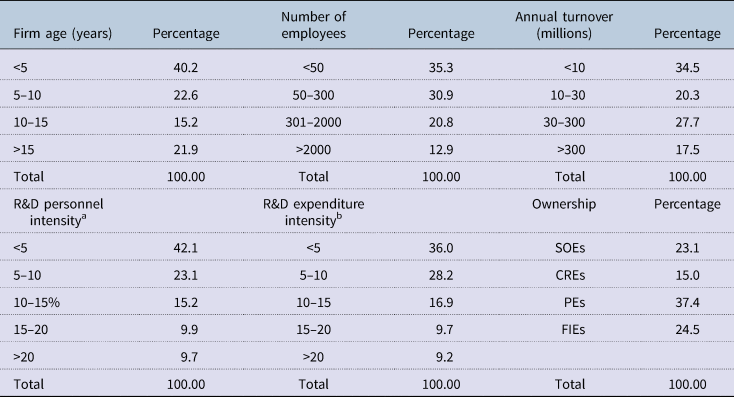

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the sample. It shows that 59.7% of the firms have existed for more than 5 years, 30.9% have between 50 and 300 employees, 27.7% have an annual turnover ranging from 3 to 30 million RMB yuan, and 37.4% are PEs. Moreover, the ratio of R&D personnel to total employees is above 5% for 57.9% of the firms, and the ratio of R&D expenditures to total sales is above 5% for 64.0% of the firms.

Table 1. Characteristics of the sample

a Number of R&D employees/total number of employees.

b Annual R&D expenditures/total sales.

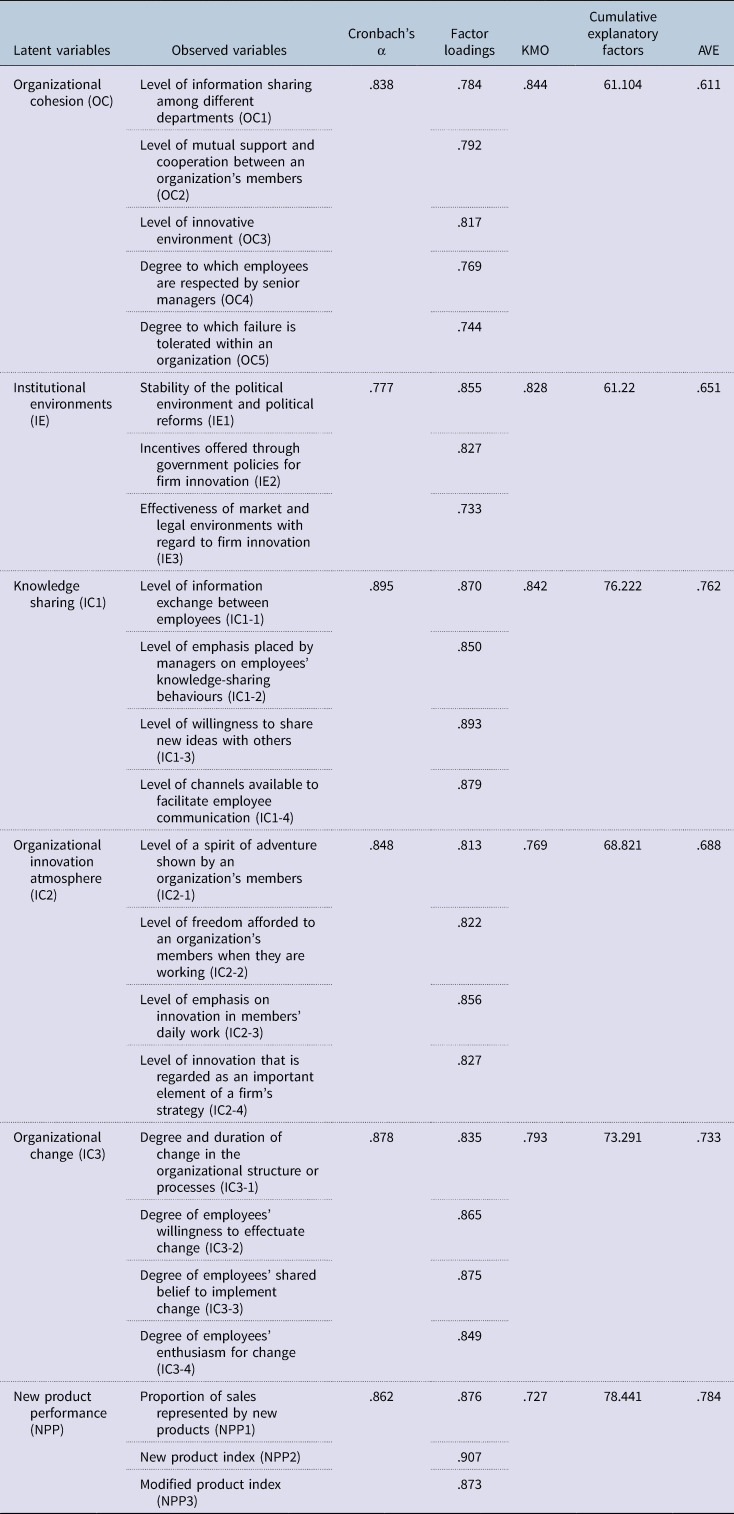

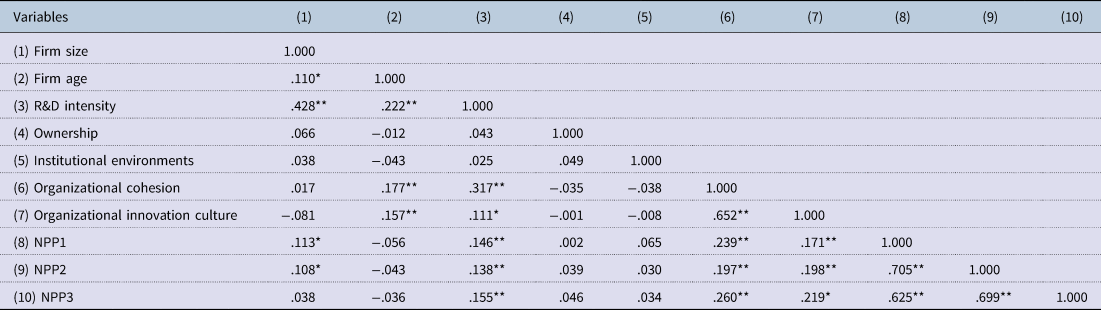

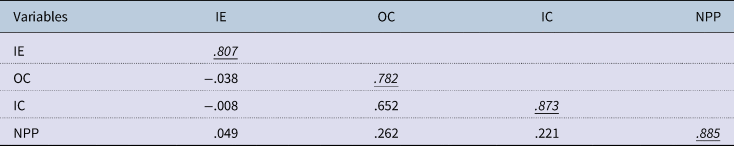

Table 2 shows the statistics for the measurement scales, including their internal consistencies, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test, their cumulative explanatory factors, and their average variances extracted (AVEs). The results of the correlation analysis shown in Table 3 reveal that both organizational innovation culture and organizational cohesion are significantly correlated with new product performance. Moreover, the results shown in Table 4 show that all the diagonal elements of the correlation matrix are greater than the off-diagonal elements, thus revealing acceptable discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, Reference Fornell and Larcker1981).

Table 2. Internal consistencies of scale constructs

Table 3. Results of the Pearson correlation matrix

**p < .01 level; *p < .05 level (two-tailed).

Table 4. Discriminant validity

Note: The values of the diagonal (in italics) are the square root of average variance extracted values.

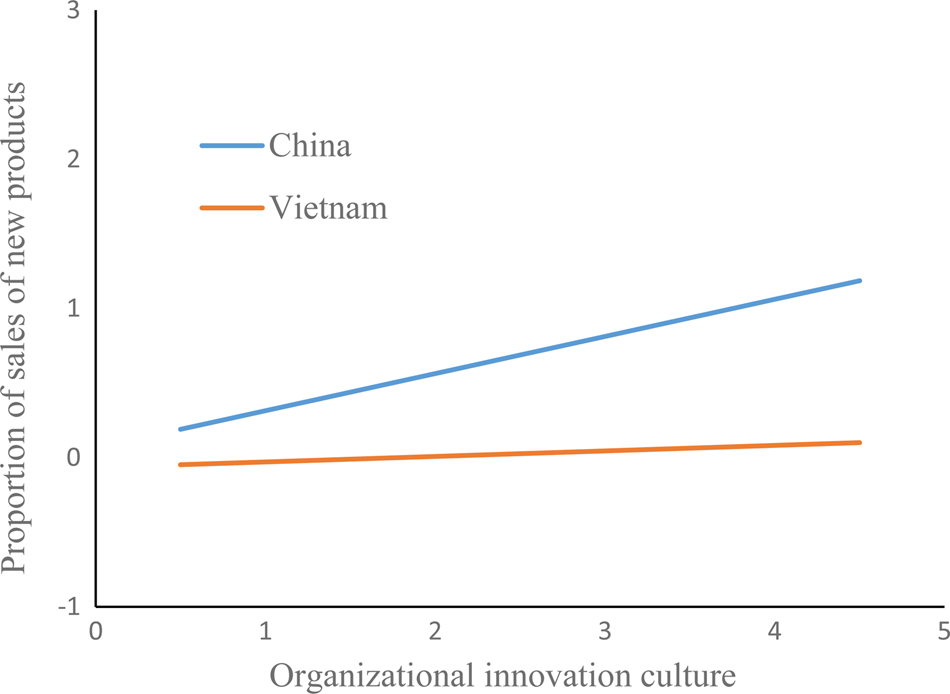

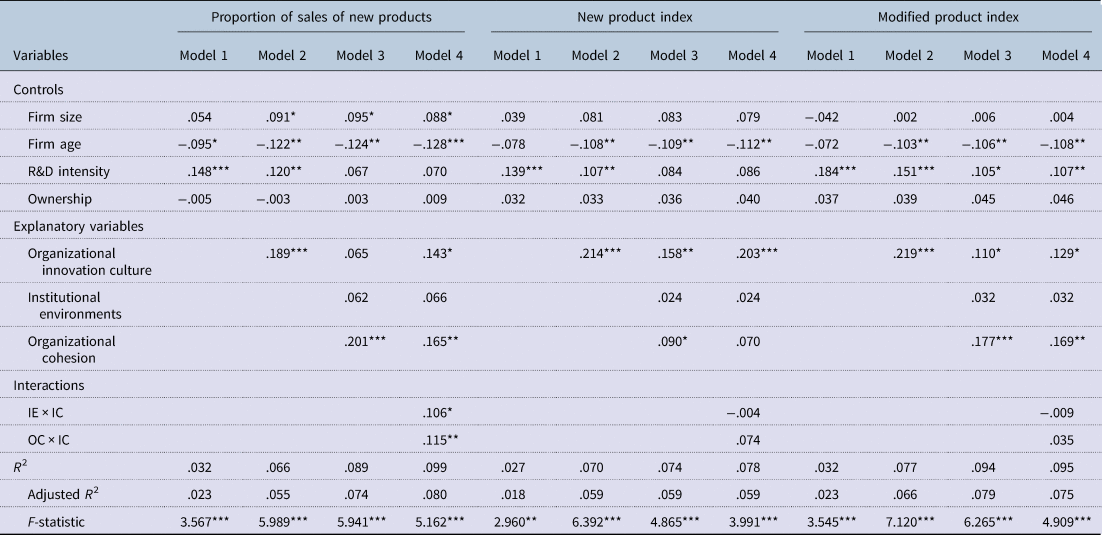

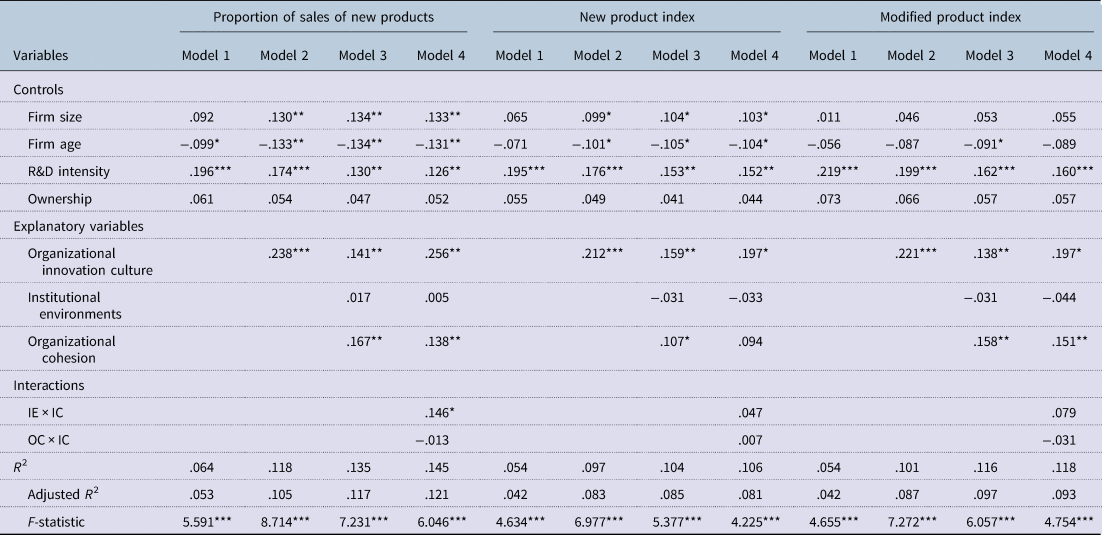

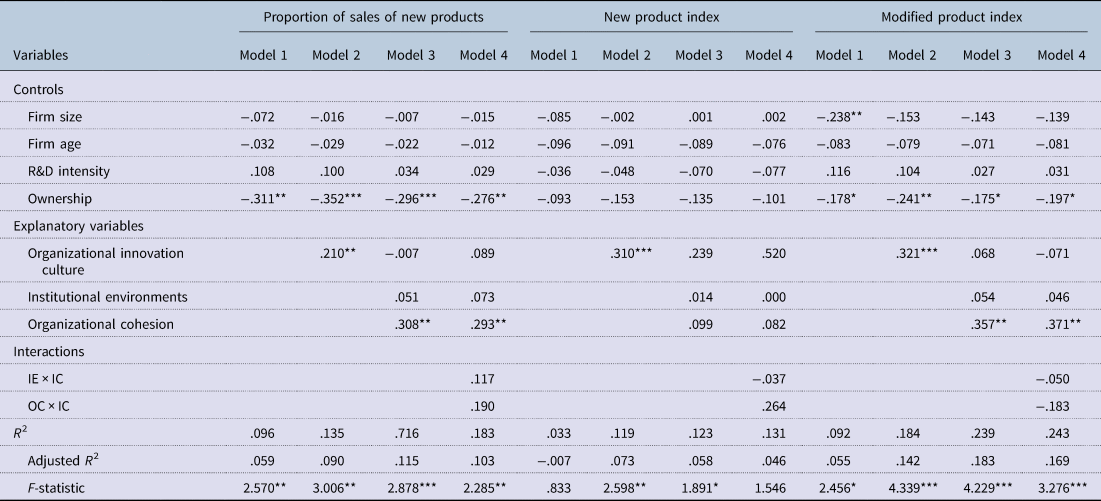

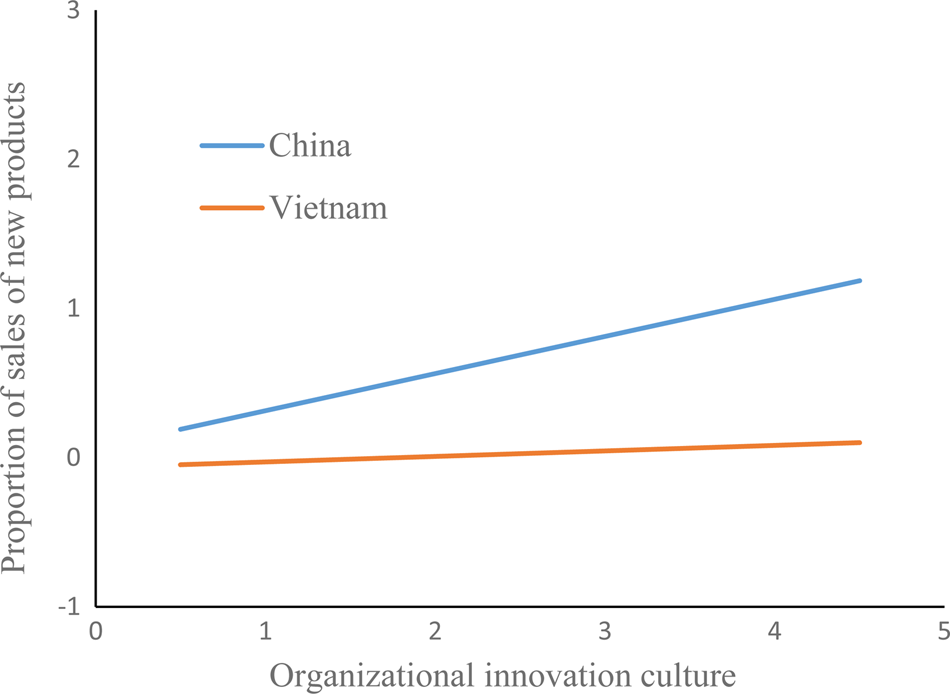

Table 5 shows the results of regression analysis, which was controlled by firm size, firm age, R&D intensity, and ownership. The results in model 2 reveal that organizational innovation culture has positive effects on all three performance measures. Thus, H1 is supported. Moreover, to test the moderating effect of the institutional environment, we used hierarchical regression modelling and the centring method to decrease the potential threat of multicollinearity on our findings. The results in model 4 show that the interaction term ‘IE × IC’ has a positive effect on the proportion of sales of new products. Thus, H2 is partially supported. Figure 2 illustrates the moderating effect of institutional environments on the relationship between organizational innovation culture and the proportion of sales of new products. The results show that the effect of organizational innovation culture on new product performance is stronger in China than in Vietnam.

Figure 2. The moderated role of institutional environments in the relationship between organizational innovation culture and the proportion of sales of new products

Table 5. Results of the regression analysis

Note: ***p < .01 level; **p < .05 level; *p < .1 level.

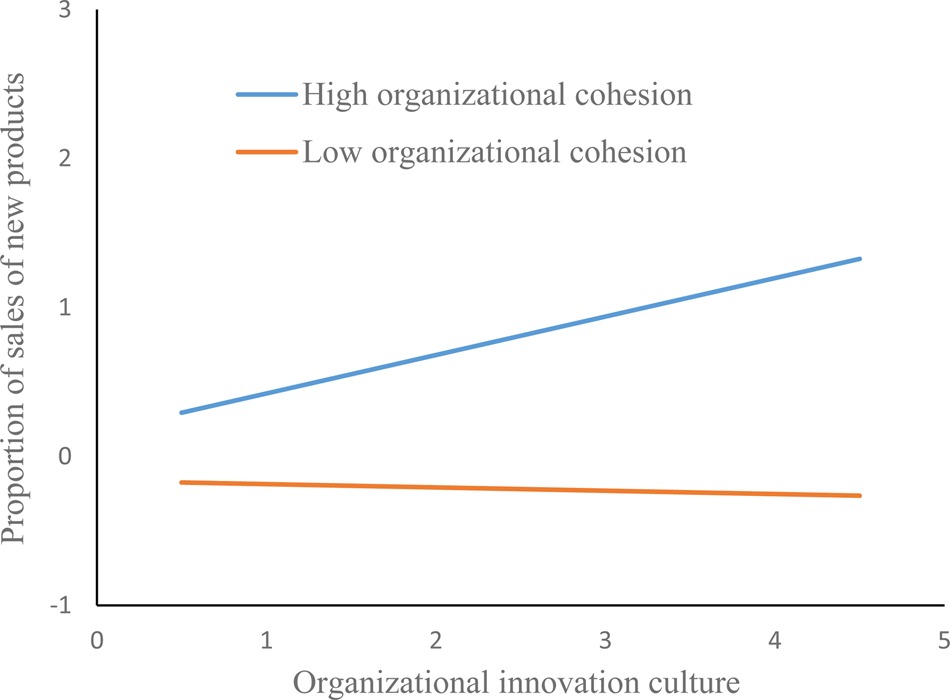

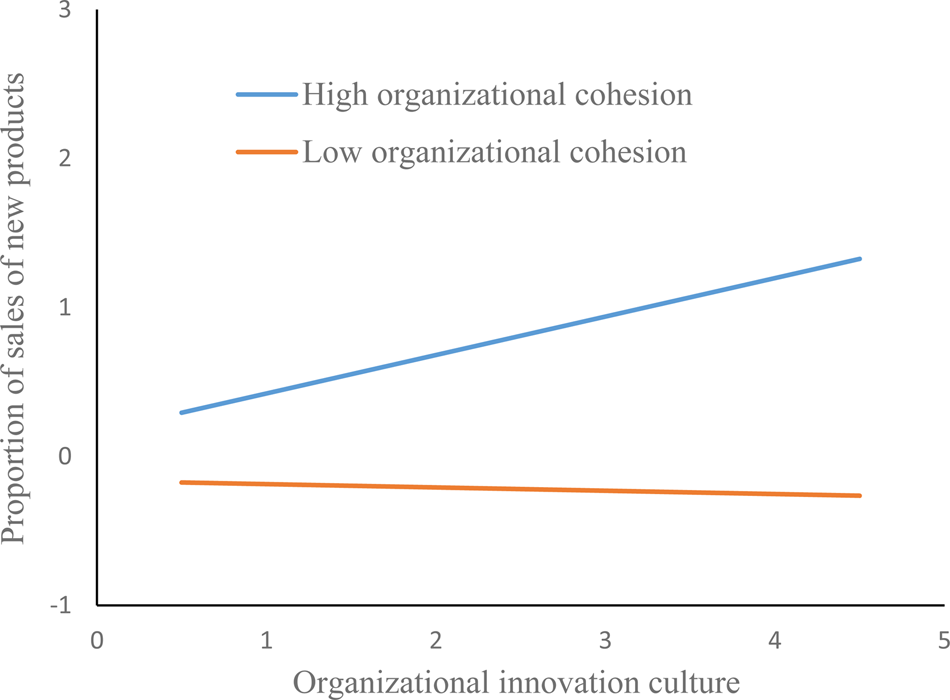

The results shown in Table 5 also demonstrate that there is a positive relationship between organizational cohesion and new product performance. Thus, H3a is supported. Moreover, the results in model 4 show that the interaction term ‘OC × IC’ has a positive effect on the proportion of sales of new products. Therefore, H3b is partially supported. Figure 3 illustrates the moderating effect of organizational cohesion on the relationship between organizational innovation culture and the proportion of sales of new products – namely, the higher the organizational cohesion is, the stronger the effect of organizational innovation culture on new product performance. However, some of the interaction terms are not significant. One possible reason for these results is that the dependent variable has three dimensions, which may decrease the possibility of significance for some variables.

Figure 3. The moderated role of organizational cohesion in the relationship between organizational innovation culture and the proportion of sales of new products

Considering that firms’ new product performance levels may be affected by institutional environments, we performed the same analytical procedure on two subsamples. Tables 6 and 7 report the results for the Chinese and Vietnamese manufacturing firms, respectively.

Table 6. Regression analysis of Chinese firms

Note: ***p < .01 level; **p < .05 level; *p < .1 level; N = 331.

Table 7. Regression analysis of Vietnamese firms

Note: ***p < .01 level; **p < .05 level; *p < .1 level; N = 102.

In the Chinese sample, we find that there is a positive relationship between organizational innovation culture and new product performance, thus supporting H1. Additionally, organizational cohesion is positively related to new product performance, thus supporting H3a. Additionally, the interaction term ‘IE × IC’ has a significantly positive effect on the proportion of sales of new products, which partially supports H2. In the Vietnamese sample, the results in Table 7 show that organizational innovation culture has a positive effect on new product performance, thus supporting H1. Further, organizational cohesion is positively related to new product performance in two cases, which partially supports H3a. However, the findings also show that the moderating effects of the institutional environment and organizational cohesion are not statistically significant. Thus, neither H2 nor H3b are supported for the Vietnamese sample.

The results indicate that there are both similarities and differences regarding the impacts of organizational innovation culture, institutional environment, and organizational cohesion on firm innovation in China and Vietnam. Both are developing and socialist Asian countries that have expanded their market economies following the premises of the socialist system. Thus, the firms in the two countries share common national conditions, cultures, and central planning backgrounds, which lead to many similarities. It is thus understandable that innovation culture plays an important role in promoting firm innovation performance in both countries. However, it is also worth noting that the institutional environments of China and Vietnam are different, and this affects how various firms develop their organizational innovation culture and create cohesion, which consequently affects their new product performance.

Generally, the different institutional environments refer to different paths of development, political systems, market environments, legal frameworks, and levels of policy support in the two countries. First, Vietnam's economic reforms started slightly later than China's, and its market system is still in its initial stage (Szalontai & Choi, Reference Szalontai and Choi2012). For this reason, it has been challenging to achieve organizational change, as it entails thorough systemic reforms throughout a firm to adapt to changes in various internal and external environments. Thus, this has led to the two different situations of the Chinese and Vietnamese firms. Second, Vietnam has had difficulties in balancing the relationship between central political control and the operation of the market mechanism. On the other hand, the Chinese government's implementation ability and its strong government policy support ensure the stability of economic development and innovation growth. Third, to some extent, organizational cohesion may differ between the two countries because of differences in political, legal, and market environments, as well as socio cultural and ethical factors, among others. These aspects may also explain some of the differences in the results of the two countries.

Discussion and Conclusions

Organizational innovation culture has become an increasingly important means of improving a firm's new product performance. Through an analysis of data from 433 manufacturing firms, this study examined the relationships between organizational innovation culture, institutional environments, organizational cohesion, and new product performance in the emerging markets of China and Vietnam. The results revealed that organizational innovation culture has a positive impact on firms’ new product performance. Moreover, the findings showed that organizational cohesion has both a direct and an indirect impact on firms’ new product performance. This is in line with the findings of Man and Lam (Reference Man and Lam2003), who noted that cohesion affects firms’ innovation performance. Accordingly, a high level of organizational cohesion is more likely to promote a firm's new product performance by helping to establish an innovative culture.

The results also revealed that institutional environments partially moderate the impact of organizational innovation culture on firms’ new product performance. It is worth noting that the institutional environments of China and Vietnam are different in regard to firms’ organizational innovation culture, and thus, those institutional environments have different impacts on new product performance. There are several possible reasons for this. First, China has instituted a series of strong central policies and maintained strong political control (Islam, Reference Islam2008), which has provided the relative permanence of personnel in positions of economic power and authority (Fforde, Reference Fforde2009). Thus, the stronger support for government policies in China has been more beneficial for firm innovation (Islam, Reference Islam2008). For example, since China has established its national policy of working towards being ‘innovation-driven’, innovation has become a nationwide phenomenon, leading firms to grow rapidly in recent years. According to the Global Innovation Index published by World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), China is now ranked among the top 25 most innovative countries. However, as discussed, Vietnam's market economy started somewhat later than China's (Szalontai & Choi, Reference Szalontai and Choi2012), and it was not particularly urbanized or industrialized (Islam, Reference Islam2008). Second, the national cultures between the two countries are different, which may have also influenced their respective organizational cultures.

Contributions

This paper offers theoretical insights in four areas. First, our findings contribute to the organizational culture literature by extending it to examine the impact of innovation culture on firms’ new product performance, which stands in contrast to other studies in both emerging markets (e.g., Wei, Samiee, & Lee, Reference Wei, Samiee and Lee2014) and in developed countries (e.g., Khazanchi, Lewis, & Boyer, Reference Khazanchi, Lewis and Boyer2007; Stock, Six, & Zacharias, Reference Stock, Six and Zacharias2013) that mainly analysed firms’ organizational culture or innovation.

Second, this work also contributes to the literature by providing a multidimensional framework of organizational innovation cultures. These drivers have rarely been examined jointly in prior studies. Previous research has focused on the constructs of firm environments (e.g., Dobni, Reference Dobni2008) or communications (e.g., Arnetz, Lucas, & Arnetz, Reference Arnetz, Lucas and Arnetz2011), while others have only investigated the context of developed countries (e.g., Stock, Six, & Zacharias, Reference Stock, Six and Zacharias2013). Our study extends the established framework of organizational innovation culture in three dimensions, including knowledge sharing, organizational innovation atmosphere, and organizational change, to incorporate a single dimension limit. Moreover, according to the knowledge-based view (Zander & Kogut, Reference Zander and Kogut1995), knowledge sharing and transfer within a firm are particularly critical to facilitating new knowledge creation and organizational learning (Bhatti, Zaheer, & Rehman, Reference Bhatti, Zaheer and Rehman2011; Uygur, Reference Uygur2013). However, the most strategically important knowledge is usually complex, tacit, and causally ambiguous, which makes it difficult to transfer it within a particular firm (Jensen & Szulanski, Reference Jensen and Szulanski2007; Uygur, Reference Uygur2013). In this vein, we extend the literature on knowledge sharing and transfer within firms (e.g., Héliot & Riley, Reference Héliot and Riley2010; Uygur, Reference Uygur2013) by identifying organizational innovation culture from the perspective of knowledge sharing.

Third, organizational cohesion plays an important role in improving firms’ new product performance. A focus on both organizational innovation culture and organizational cohesion allows us to better examine the antecedents of new product performance in emerging markets. This study enriches prior research (e.g., Hirunyawipada, Paswan, & Blankson, Reference Hirunyawipada, Paswan and Blankson2015) by considering organizational cohesion as both a direct and an indirect (moderating) variable between organizational innovation culture and firms’ new product performance.

Fourth, differences in the institutional environments of two emerging markets affect how firms develop their innovation culture and implement innovation behaviours. Our findings extend previous work on innovation culture and firm performances in the developed countries (e.g., Stock, Six, & Zacharias, Reference Stock, Six and Zacharias2013) by exploring the moderating effect of the institutional environment on the relationships between organizational innovation cultures and new product performance in Chinese and Vietnamese firms and by sharing new findings for emerging markets.

Managerial implications

Our results provide significant implications for practitioners concerned with the management of organizational culture and organizational cohesion. From a managerial viewpoint, the findings of this study suggest that top managers should consider linking the establishment of organizational innovative culture to product innovation by creating high levels of organizational cohesion.

Managers should create more innovative cultures within their firms. First, they should establish a communication platform for the exchange of new ideas among employees. Second, given that an innovative organizational culture requires finding ways to share and transfer tacit knowledge and skills, firm managers should establish a collaborative culture by encouraging more cooperation among departments and knowledge sharing and transfer among employees. Third, they should cultivate a culture of change in order to enable their firm to detect the appropriate time for organizational change.

Managers should create greater levels of cohesion. First, they should do so by creating a positive atmosphere to enable support and cooperation between employees and by cultivating senior managers’ respect for their employees. Second, they should broaden their firm's ability to tolerate failure. Third, they should eliminate the idea that ‘information is power’ by establishing various channels of information within their firm.

Lastly, it has been suggested that an institutional environment is an important factor affecting firm innovation. Thus, government policy initiatives should focus on the needs of the different cultural contexts of firms. Moreover, governments should improve institutional environments and create more incentive policies to encourage firms’ innovation practices.

Limitations and directions for future research

This study has certain limitations. The first limitation is that the findings are derived from a sample of manufacturing sectors in two emerging markets with both similarities and differences between their national cultures, which may have affected the likelihood of measurement invariance with regard to organizational innovation culture. Thus, the expansion of our findings to other emerging markets would be a fruitful direction for future studies. Second, we only focused on three different dimensions of organizational innovation culture. Future research could use other dimensions, such as ethical or psychological factors, to define organizational innovation culture. Third, the survey data for this study were based on the perceptions of the respondents and their self-assessment of the items, which may have been affected by measurement flaws or inherent deficiencies of the survey method. Thus, using other data sources would be useful in future studies. Fourth, although organizational cohesion and organizational culture are different concepts, in practice, a cohesive organization may coexist with a strong culture. Thus, future research should more clearly identify the essential similarities and differences between the two concepts.

Author ORCIDs

Xuemei Xie, 0000-0002-1855-8091.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 71472118 and 71772118), Shanghai Pujiang Program (Grant number 18PJC056), and Program for Professor of Special Appointment (Eastern Scholar) at Shanghai Institutions of Higher Learning.

Xuemei Xie is a professor of Innovation Management at the School of Management, Shanghai University, China. Her main research interests include collaborative innovation. She has managed more than 10 research projects funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, ministries and government agencies. She has published more than 30 publications in international journals such as Journal of Business Ethics, Technovation, Journal of Business Research, Psychology & Marketing, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Business and Society, Business Strategy and the Environment, Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, Journal of Cleaner Production, and Total Quality Management & Business Excellence.

Yonghui Wu is Ph.D candidate at School of Management, Shanghai University, China. Her main research interests include innovation management and entrepreneurship management. She has published in major refereed journals such as Asian Journal of Technology Innovation, and Chinese Management Studies.

Peihong Xie is a professor at School of Management, Shanghai University of International Business and Economics, China. He has published in major refereed journals in International Journal of Retail and Distribution, Nankai Business Review International, Frontiers of Business Research in China, Journal of Chinese Human Resource Management and so on.

Xiaoyu Yu is a Professor of Innovation and Entrepreneurship at School of Management, Shanghai University, China. He serves as editorial board members of academic journals such as Academy of Management Perspectives. His current research interests include entrepreneurship and innovation management.

Hongwei Wang is Ph.D candidate at School of Management, Shanghai University, China. Her main research interests include collaborative innovation and innovation ecosystem.