The branch of psychology that is concerned with the nature of thought, cognitive psychology, suffers from at least two fundamental problems. One problem is that nobody knows what a mind is. The second is that, even with the certain knowledge that minds exist, there is no principled theoretical framework that informs on how they might be studied. And then there is the oddity that the idea that the mind might be systemically studied is a very recent invention. Although people, philosophers and poets mostly, have been describing mind from the point of view of what they intuit, the idea that data might be informative apparently did not occur to anyone until the late nineteenth century. This situation creates a certain informality where the few people who are interested in the systematic study of mind are basically left to their own devices. When people are left to their own devices, the science that evolves will be guided in the first place by what people notice and then by what they deem to be important. The issue of what comes to be observed is especially relevant to this inquiry into human temporality as it begins with the proposition that the field of cognitive psychology has, for the most part, been valuing the wrong things.

The circumstances that flow from the informality of noticing and the vagaries of valuation have led to a perspective on temporality where a single phenomenon has come to be prized in importance. That phenomenon is that humans and other animals can, with some accuracy, judge the duration of time passage. This phenomenon might not have arisen as something to be noticed and valued were there not a pre-existent interest in processes of judgment. Psychology has its own peculiar history, and it happens to be the case that the earliest psychological investigations were often focused on processes of judgment, and particularly on judgments of sensory qualities such as brightness and loudness. Although temporal duration is not associated with a sensory quality (there are no receptors in the body for time), the experience of temporal duration came to be understood as belonging in the mix with brightness or loudness when it came to judgment. Nevertheless, this book will proceed by noticing and valuing other things, things that do not involve judgement, which will make it clear that the experience of time passage is not at all like the experience of light and sound, and that presuming that it is leads to nonexplanatory theories of our time sense, and to incorrect interpretations of otherwise legitimately conducted experiments. Mostly it leads to an understanding of temporality that is in error.

These statements are not simple matters of fact, and they need to be justified. It is important to understand why an interval of time cannot be treated as offering a sensory quality and why the psychology that flows from that treatment is misleading. To properly motivate the Gestalt perspective on time taken here, it is necessary to first understand what it is replacing. There are specific structural assumptions that must be made about the experience of temporal duration for it to be treated as a sensory experience that might be judged, independent of whether those judgments are accurate or not. Our point of departure is an examination of these assumptions. Once we have clarified what it means to be an object of judgment, an illustrative example of a judgment experiment will be offered. This is a field that is driven by empirical inquiry and some specific knowledge about methodology and technique will be invaluable for appreciating what kinds of things are learned in judgment experiments. There are, in addition, theories and computational models that have been constructed to explain how it is that animals are able to judge durations in the first place. The most influential of these are pacemaker-accumulator models. These models deserve particular focus as they are quite transparent both about their psychophysical roots and the way in which time is conceptualized as a psychological quantity. Having waded through some representative methodology and some of the theory, the sensory perspective on temporal duration will be interrogated by returning to the core assumptions about time that launched this field. At this point the foundational theme of this book will be introduced; that the experience of time is unique by virtue of having a phase transition. Experimental paradigms and theories of duration judgment that fail to recognize that there is a phase transition are missing the single most important fact about the experience of time. It is this circumstance that opens the field of human temporality to an inquiry based in Gestalt psychology.

The Psychophysical Perspective on Time

Psychology, as a unified and coherent discipline, began within an intellectual movement that from about 1890 on had been developing rigorous techniques for the study of mind. This movement, known as sensory psychophysics, was principally concerned with the most primitive of psychological experiences, with the experience of sensation. One of the issues dealt with in this field was how energy impinging on a sense was experienced as sensation. A prototypical inquiry in this field might establish the relationship between perceived brightness and light intensity or between perceived loudness and sound intensity. Time passage might seem an unlikely candidate to be swept up by sensory psychophysics insofar as time does not impinge on the senses like, for example, light or sound. Nevertheless, temporal duration does have a critical property in common with sound and light intensity that made it susceptible to psychophysical investigation. This property is that light intensity, sound intensity, and the durations of time intervals all have magnitude. Even though temporal duration is not strictly an intensity, because it has magnitude it inherits the mathematical properties of magnitude. One key property that magnitudes have is that they can be graded in terms of size and so can be ranked and sorted. The sorting property is so fundamental to the theory of measurement that it defines a class: continua that can be ordered based on magnitude form the class of prothetic continua. So, although the body receives time passage in a way that is quite different from the way it receives light and sound, the things being received all belong to the same measurement class. It is with this single observation that the study of timing in humans and other animals was set in stone.

The observation that durations have magnitudes, that they can be long or short, is not particularly trenchant and the class of prothetic continua is hardly exclusive. Most things that arise in everyday experience are characterized by magnitude and can be meaningfully compared in terms of size. Physical intensities obviously have this property but so do mathematical continua such as riskiness and likelihood. In fact, the few things that do not have magnitude are worth pointing out – they belong to the class of metathetic continua. Direction does not have magnitude, and east is not more or less than north. Different tastes do not have magnitude in the sense that nutmeg is not more or less than basil. A given taste can be faint or strong and, in this sense, given tastes are on prothetic continua. The same applies to color. Blue is not more or less than red insofar as the perception of color is organized on a color wheel. Anything arrayed on a circle cannot be greater or less than other things on the circle. But colors can be more or less saturated, so in terms of saturation a given hue generates a prothetic continuum.

Sensory psychophysics began with the recognition that subjective experiences also had magnitudes. Although this may be obvious, it is after all the basis of the pain scale and all Likert scales (typically 4- to 7-point scales on which just about everything is rated), it is nevertheless quite amazing. That subjective experience could have magnitudes that are coordinate with objective magnitudes is one of the more interesting outcomes of adaptive evolution. That we would have an abstract sense of magnitude is not something to be taken for granted and should be appreciated for its weirdness. In the objective world, the world of physical matter, the magnitudes that form prothetic continua have dimensions such as inches, seconds, liters, and so on. But in the mind, there are no dimensioned quantities, there is just thought. Nevertheless, people can assign magnitudes to their private and subjective experiences and can meaningfully compare them. Consequently, there are two places under heaven where there are prothetic continua: in the physical world of matter where continua are dimensioned, and in the mind where the experience of physical continua is dimensionless. It is here that sensory psychophysics becomes a science. If there is a prothetic continuum of magnitudes in the world that creates a prothetic continuum of magnitudes in the mind, then there might be lawful relationships between these two continua. The originality and profundity of this idea cannot be overstated. Humans had for millennia the self-reflection to ponder subjective experience as well as the mathematics to collect such reflections into laws. But the notion that there might be laws of thought is a very recent development, dating back no further than the birth of modern psychology around 1900. A law of thought with the world on one side, the mind on the other, and an equal sign between them is a heady thing to contemplate, but this is exactly what sensory psychophysics was built for.

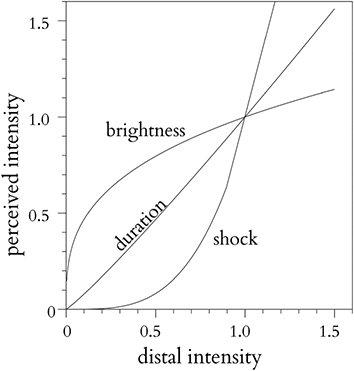

Stevens’ (Reference Stevens1957) enduring contribution to sensory psychophysics is an eponymic law that relates stimulus intensity to perceived magnitude. This law is powerful in two senses. First it is powerful in that it was intended to be applied to the gamut of human experience, and its scope is, in fact, breathtaking. The second sense is that this law is literally a power law, a type of mathematical function that makes intermittent appearances throughout the history of psychology and which will reappear in this book in discussions of both memory and animal body size. Stevens’ power law is a piece of mathematics that specifies how subjective experiential states are produced by objective states of the world. It has the form:

In this equation ψ is the perceived magnitude, a purely mental quantity that must be discovered through experiments in magnitude estimation, and I is a stimulus intensity that is obtained through a physical measurement; k is a constant that plays the important role of making the equation dimensionally correct – both sides must be dimensionless as mental states such as ψ(I) do not have dimensions. The exponent α is the key variable in this equation in that different sources of stimulation will have different exponents. The exponent informs on whether the experience of a source is magnified (α > 1), minimized (α < 1), or veridical (α = 1). It should be pointed out here, perhaps unnecessarily, that Stevens’ law is an enormously impressive achievement. It essentially collects the totality of world experience, at least that part that can be attributed to a source intensity, into a single law with a single parameter.

Although Stevens’ law certainly looks like a law of nature, it is not a law of nature in any usual sense. First there is the issue of how the intensity, I, is interpreted. To appreciate how I operates in Stevens’ law it will help to look at a physical law. Consider Newton’s 2nd law of motion, F = ma, force equals mass times acceleration. The three terms in Newton’s law have a set meaning; what they are does not depend upon context. Forces, masses, and accelerations refer to the same quantities regardless of what is accelerating, what type of force is acting, and what has mass. Acceleration, for example, the a in F = ma, refers to a particular quantity and it will always have the dimensions of length per time squared. This is not true of the intensity in Stevens’ law. Intensity is not a particular quantity, and its dimensions will vary depending on the physical source. The intensity of light is measured in lumens or lux and is a different kind of thing than the intensity of sound, which is measured in terms of watts per square meter. So, although the I in Stevens’ equation looks like it refers to a property of things called intensity, it requires quite of bit of interpretation to understand how it functions.

Even more unusual, from a mathematical point of view, is the ψ(I) on the left-hand side of Stevens’ law. It is intended to be read as “the magnitude of the subjective experience of intensity,” but subjective experiences are not just one thing. The subjective experience of light magnitude is different from the subjective experience of sound magnitude; brightness is plainly different from loudness. Yet despite the manifest differences that exist between the different dimensions of experience, there is an abstract sense of magnitude that cuts across them all. This abstract sense of magnitude is friendly to quantitation. So even though a bright light could not be more different than a loud sound, somehow people are able to create something like a 7-point Likert scale for both and report that this brightness is, say, a 3 out of 7, and that loudness is, say, a 6 out of 7. It is this abstract sense of quantitative magnitude that is intended by the notation ψ(I).

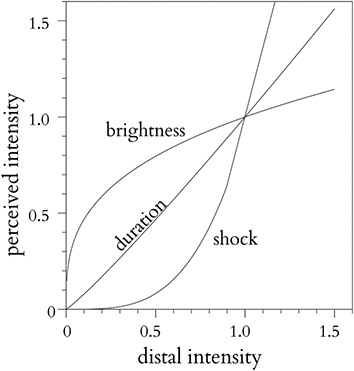

Figure 1.1 illustrates three examples of Stevens’ law and shows how three different types of intensity are experienced. More importantly, it implicitly illustrates how temporal duration has been historically conceptualized. As the experience of duration lies on a prothetic continuum alongside the myriad forms of sensory experience, duration can share space with the dimensions of shock and brightness in a plot of perceived intensity. The only way in which duration, brightness, and shock are individuated is through α, the power law exponent. In this regard duration is quite unusual. Shock, for example, with α = 3.5, is experienced in a rapidly accelerating way (the absolute numbers are not meaningful here, but ratios and percentages are). A doubling of shock intensity is experienced as an 11-fold increase in the feeling of shock. In contrast, brightness with α = 0.33 is experienced in a decelerating way. A 100% increase in light intensity is experienced as only a 25% increase in brightness. The duration curve is unusual because it is roughly linear. The duration exponent α = 1.1, implying that a doubling of a duration in the world is experienced as a doubling of the subjective experience of duration. This might seem to imply that people experience the passage of time veridically.

Figure 1.1 tells the story of how the experience of time passage found a home within the discipline of sensory psychophysics. This homecoming had far-reaching consequences. Psychophysics is a powerful tool and here we should acknowledge what powerful tools can do. Once the passage of time was put into the mix with light and sound (and shock and many other sensory experiences), the die was cast for the unfolding of timing theory and for the conduct of experiments in human and animal timing.

The Peak Interval Procedure and Weber’s Law

At this juncture it might be instructive to consider a concrete and productive psychophysical paradigm for the study of timing in animals. There are many paradigms that might be considered for inclusion, but the peak interval procedure is relatively straightforward and illustrates well how animals express their understandings of time passage. As the procedure involves a bit of unsubtle trickery, it would not work as well with human participants as it does with rats and pigeons. Nevertheless, the nature of the data produced is universal and would capture that nature of duration judgment in any animal that was capable of learning to respond to a given interval of time.

In this procedure animals are removed from their cages and placed into a conditioning chamber. At some point an environmental event is introduced that acts to signal the beginning of the time interval. Appreciating the environmental meaning of the signal and that a time interval is involved is something the animal learns over many episodes of being put in the conditioning chamber. The quality and type of the signal is subject to the whim of the experimenter and consists typically of the onset of a sound or light that clearly marks the beginning of an epoch. It is not a trivial observation that animals, people included, can appreciate that lights and sounds might signify – have meaning beyond their physical characteristics. In this paradigm, duration is measured as elapsed time following the orienting signal.

Duration is introduced as something that is environmentally relevant by training the animals on a fixed interval (FI) schedule. In FI training animals learn that after FI seconds have passed, a response will be followed by a food or juice reward. Typical FI values are in the tens of seconds, presumably because such times permit good resolution of response rate – the dependent variable (the thing measured) in these studies. Different animals respond differently, rats press bars and pigeons peck, but both bar presses and pecks are discrete events. As discrete events, they can be counted and so lend themselves to rate measurement. Various types of laboratory animals, it turns out, can learn the relation between reward expectancy and FI duration, and they communicate this through their response rates (bar presses per minute or pecks per minute). As the FI duration approaches there is an increasing amount of bar pressing or pecking. The trickery is that on some trials, referred to as probe trials, no reinforcement is given. The animal is basically stood up, but they do not stop responding after the FI has passed. In this paradigm the shape of the response curve tells the story of what animals understand about quantities of time passage.

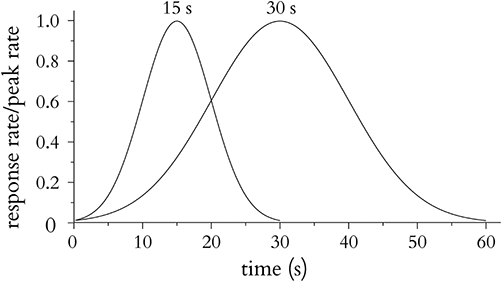

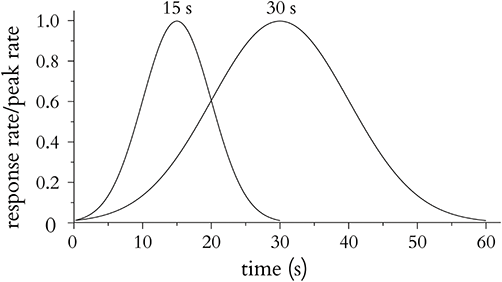

Figure 1.2 illustrates idealized rate curves on probe trials for an animal that has been trained on two fixed intervals, 15 s and 30 s. In practice the way data such as these would arise is that the onset of a light, say, would signal that a reward would be available after an FI of 15 s, whereas the onset of a sound (white noise burst typically) would signal that a reward would be available after an FI of 30 s. The x-axis then is the amount of time that has passed since the presentation of one of these signals. The y-axis is the rate at which the animal is responding using whatever body part is relevant – rats push bars and pigeons peck plates. This animal demonstrates its ability to learn the fixed intervals by generating a peak response rate at 15 s when a light turns on and a peak response rate at 30 s when a sound commences.

The response rates in both conditions follow what appears to be bell-shaped curves. To be sure, bell-shaped curves are not always observed on probe trials, but they are typical. It may be necessary to clarify that the appearance of a bell-shaped curve in response rate has nothing to do with the normal (or Gaussian) distribution that is a fixture in the analysis of data. The response rate curve is not a distribution, it is just a graph of response rate. To the extent that the response curve is bell-shaped, it illustrates that the growing excitement engendered by an approaching FI duration is mirrored by a growing disappointment that the time for reward delivery has passed.

The response rate curves tell a more nuanced story than just that this animal can learn fixed time intervals. The width of the response rate curve, however it is defined, provides a measure of uncertainty. That there is uncertainty is evident from the fact that there is quite a bit of bar pressing or pecking both before and after the FI. The range of times when the response rate is relatively high defines an acceptance zone, essentially a measure of FI-ish, close to but not quite the FI. What it means for a response rate to be “relatively high” is typically defined by rates that are higher than half of the peak rate. The acceptance zone would then be the full width at half maximum (FWHM). The FWHM provides a quantitative estimate of timing uncertainty in each FI condition.

Where the peak interval procedure makes deep contact with the psychophysics of judgment is in the way the magnitude of timing uncertainty scales with the magnitude of the FI. In these idealized data the FWHM at an FI of 30 s is about twice that of the FWHM at an FI of 15 s. That is, 30 s-ish is about twice that of 15 s-ish. This kind of scaling is our first encounter with Weber’s Law. There are several ways of expressing Weber’s law and here the appropriate formulation is:

the uncertainty of experience ~ the magnitude of experience.

There are innumerable instances of this general law and several different ways in which uncertainty is expressed and experienced. In the context of duration estimation, it leads to the width of acceptance zone, the width of what is “ish,” being proportional to the size of the time interval that has been trained.

The proportionality in Weber’s law is both a profound and completely common aspect of human experience. It is profound in that it speaks to the fundamental nature of experienced magnitude. Even though it is not a physical law, it has the character of a physical law – almost like an uncertainty principle. It is common in that the proportionality is found in all sensory systems and in magnitude judgment generally. To get a sense of its generality, consider how an inch might be demonstrated with the thumb and index finger. No one’s inch will be an inch – it will be a little too big or a little too small. This is the acceptance zone, the inherent uncertainty, of an inch. When the hands are placed apart to indicate the size of 12 inches or a foot there will again be error. But the error is now much larger. When we indicate how big an inch is, we will not be off by an inch, but we can easily be off by an inch when we show how big a foot is. The error always grows with the size of the thing that is judged, estimated, or felt. If the error grows proportionally with the size of the thing judged, then the system of judgment is said to satisfy Weber’s Law or be Weberian.

That animals can accurately judge time passage and respond appropriately to an FI is certainly evidence that animals can encode, store, and retrieve the durations of time intervals. That the process of time judgment has the Weberian property is evidence that time judgment is not materially different than the judgment of sensations generally. Both conclusions will be challenged shortly where it will become clear that although the data in the peak interval procedure may be unimpeachable, the interpretation given to the data is not. There are good reasons to suspect that it is not time itself that animals are judging when they reach maximum pecking and/or pressing after 15 or 30 s has elapsed.

Pacemaker Theory of Timing

When an animal starts pressing a bar or pecking on a plate as a fixed interval of time approaches, it is doing something quite remarkable. Duration does not have a sensory quality. There is no energy associated with duration and there is no sensory organ that allows animals to perceive time. Yet the animal is aware of temporal displacement, that time is passing. Logically, the animal must have some form of memory that allows different moments of time to be differentiated. The question that arises then is what kind of memory allows humans and other animals to mark specific intervals of time passage. Scalar expectancy theory (SET) is one highly influential attempt at constructing a memory system that can measure the passage of time (Gibbon, Reference Gibbon1977; Gibbon, Church, & Meck, Reference Gibbon, Church and Meck1984).

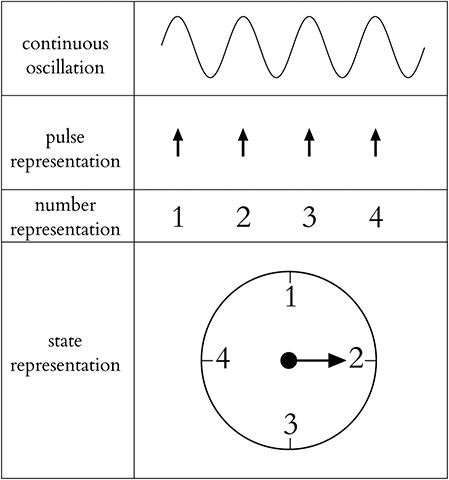

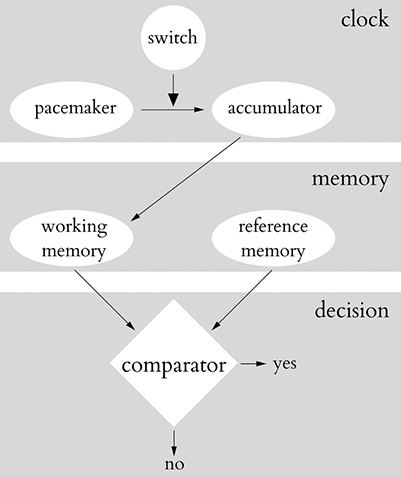

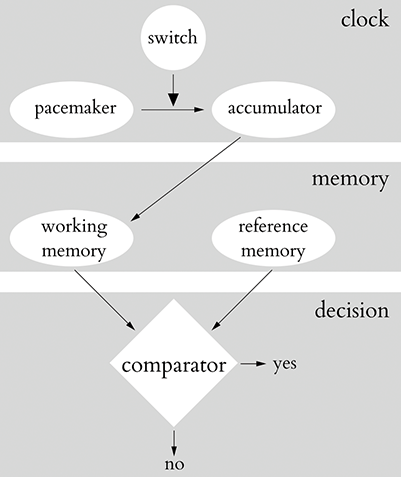

In the most elementary terms, SET is a scheme for making ψ(I) out of I for the kind of intensity that is temporal duration. It achieves this through the artifice of constructing a brain-based clocking mechanism (Gibbon, Church, & Meck, Reference Gibbon, Church and Meck1984). The logic of the SET clock is illustrated in Figure 1.3.

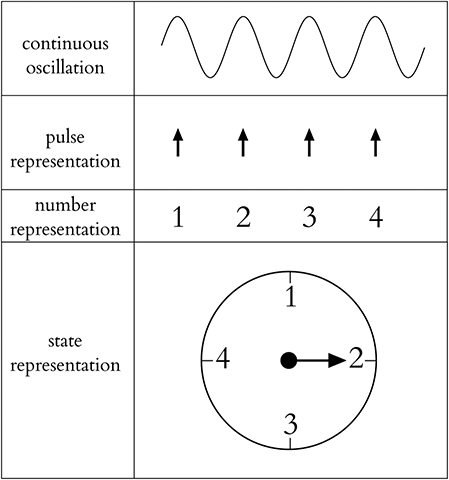

SET begins by presuming that there is a source of continuous oscillation in the brain that may be harnessed to produce a sense of time passage. Oscillations in physics are generally sine waves and that is what is depicted here. The details are in the harnessing mechanisms insofar as brain oscillations, brain waves, do not communicate the duration of time intervals. To transform oscillations into something that has magnitude, SET makes a second presumption – that there is a mechanism that can pick out phases of the oscillation to create a train of pulses. Any point in the repeating cycle will serve this purpose, and in the second panel of Figure 1.3 crests (wave maxima) are used to create a pulse train. The pulse train is illustrated as a set of separated arrows to highlight that a pulse is a discrete thing. What a pulse train has that a continuous wave does not is numerosity; because pulses are discrete, they may be counted. So, in the third panel of Figure 1.3 the pulses are counted, and the four arrows are now replaced by the numerals 1 through 4. It is unclear how pulses might be counted in a biological system, but presumably it is accomplished through a state representation where pulse arrivals are attended by transitions of state. The fourth panel is an idealization of how states embody number. In this idealization there is a pointer that moves one step clockwise with the reception of each pulse. The position of the pointer is the embodiment of duration magnitude. Regardless of whether any of this has biological plausibility, this picture has for many years been influential in theories of interval timing.

SET supplements the scheme for turning oscillations into magnitudes with a switch and a set of buffers that allow humans and other animals to behave in ways that are meaningfully related to time passage. The full theory is illustrated in Figure 1.4 as a kind of flow chart that is intended to indicate the process in which counts are prepared, accumulated, and then compared to environmentally relevant counts that have been learned in the past. The switch is of special interest because it is the locus where the internal clock meets the world. Logically, for this scheme to operate as a counter that can accomplish duration estimation, there must be a zero count when the interval of interest to the animal begins. Beginnings and zero counts are negotiated in SET through switches. The switch is assumed to have two states. In the open state the oscillator is running but it does not pass pulses to the accumulator. When something in the environment tells the human or other animal that an interval of interest is beginning, the switch moves to the closed state and pulses are accumulated.

The remainder of SET is concerned with how meaningful behavior might be produced by counting pulses. Meaningful behavior is conceptualized as being produced when the count arrives at some target. SET requires the existence of target counts to operate as a timing mechanism and so there is the supposition of a buffer, referred to as the reference memory, that holds special counts that the animal has learned through prior experience. For example, if a rat is being assessed in a peak interval procedure, it may have learned that after 20 s has passed a bar press will lead to a food reward. The rat does not know anything about seconds, but 20 s corresponds to some count, a count that presumably reflects the frequency of the oscillator and the rate at which pulses are produced. As an example, a 40 Hertz (Hz) oscillator produces 40 pulses per second and 800 pulses in 20 s. In this example, reference memory would contain a state corresponding to 800 pulses.

The final steps of SET describe a scheme for how the progressing count might be acted upon. Another buffer will be required to store the ever-increasing counts that correspond to the ever-increasing passage of world time. The accumulator might be conceptualized as a working memory (it is in some depictions of SET), but here it is regarded as just being a counter. It passes count states to a working memory that is not regarded as a counter but as a repository for whatever the accumulator passes to it. Finally, the state of the reference memory and the state of working memory are continuously compared, and when there is some degree of equality between the reference and working memory states, the relevant duration is deemed to have passed, and an action is invited. The invitation is denoted by the “yes” in the figure.

Digital and Analog Clocks

Scalar expectancy theory is an explicit computational theory of the timekeeping sense in humans and other animals. To this end it succeeds in providing an account of how, say, a rat, person, or pigeon could learn to track and respond to the passage of an interval of time. Its principal virtues, that it is explicit and computational, are also potential faults. It is also, oddly, a close representation of how quartz clocks keep time. Perhaps it is merely a coincidence that SET and its associated timing model (Figure 1.4) followed soon after Casio introduced the first mass-produced quartz wristwatch. Placing the inner workings of a quartz clock into the head does succeed in creating a head that can keep time, but it also suggests that timing theory might benefit from a larger perspective.

That the pacemaker-accumulator component of SET chops a continuous analog signal into pulses for the purpose of counting might create the impression that continuous analog signals are not appropriate for timekeeping. This is not true; counting is not required for timekeeping. Putting aside the difficult question that SET was designed to solve, how humans and other animals can accurately judge the durations of time intervals, it is important and necessary to point out that there are many expressions of timekeeping that are analog in nature. Here a single example will make the point that analog timing mechanisms proliferate through animal bodies and through nature generally.

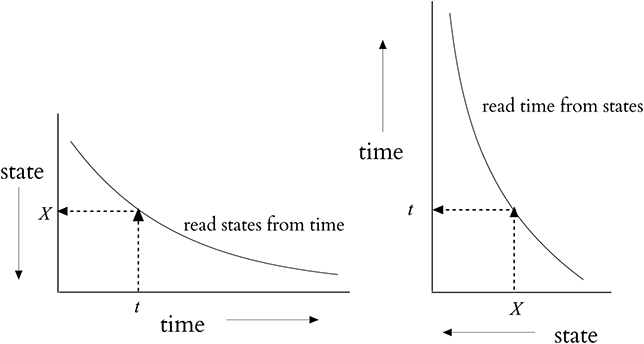

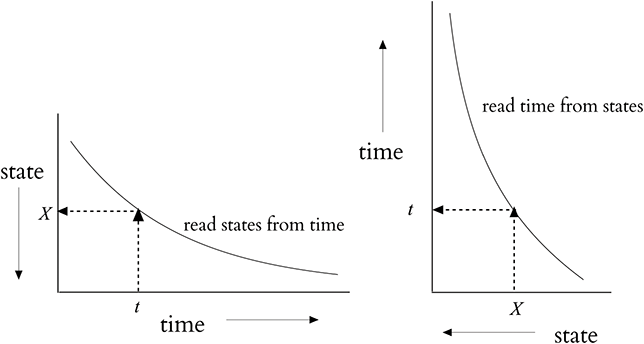

The example that will be considered here is the decay process. Arguably, decay is the most generic process in nature as every perturbation away from a state of equilibrium will involve a decay process as the equilibrium state is restored. Normally decay is not considered to be a mechanism of timekeeping, but that is only because physical processes are typically conceptualized as functions of time. In this conception the evolution of time produces system evolution. But turning this perspective on its side will create a clock. How this works is illustrated in Figure 1.5. On the left a decay process is illustrated in the way that decay is usually pictured. Time is on the x-axis and system states are on the y-axis. This plot gives the strong visual impression that as time flows, system states change. In this orientation, the interpretation is that system states are inferred from time. Given a measurement of time, t, the system state, x, is read out.

Now the plot will be transformed to a less familiar orientation, shown on the right-hand side of Figure 1.5. In this orientation the system states are on the x-axis and time is on the y-axis, giving the impression that time is inferred from system states. In this way of conceptualizing the decay process, we are not given time, but instead we are given a state of the system, and the state specifies the time. Although the physical process of decay will be less familiar than a clock face, they do operate in the same way. Reading a clock involves looking at the hand states and inferring the time. And to be clear, everybody is also quite familiar with inferring time from physical states: If you are hungry your body may be telling you that it has been a while since it was fed. If you are tired, consider that your body has been clocking your time awake and building sleep pressure.

The general situation with decay processes is that they can be construed as clocks only up to a point where the system closes in on its final resting state. There will always be a point at which time moves forward, but the decaying system does not make noticeable progress in producing new lower states. Eventually the process asymptotes to what mathematicians call an accumulation point. As decay proceeds, states become increasingly close to each other and therefore become increasingly less useful for the purpose of reading time. This behavior can be visualized in the right-hand side of Figure 1.5 where the curve becomes essentially vertical – change in time without change in state. Because decay processes inevitably asymptote, a decay clock does not have the range of SET. Scalar expectancy theory can provide a pulse count for any interval of time so long as the oscillator churns out pulses. A decay process is clocklike only for the early period when states are not piling on each other. The infinite range of SET might be viewed as a virtue, a good thing, if we think that the scope of animal timekeeping is unbounded. If, on the other hand, animal timekeeping turns out to be bounded, then SET is supplying animals with a clock that they cannot use.

The Deep Structure of the Duration Continuum

The idea that the durations of events are plausible things for humans and other animals to judge is supported by the fact that humans and other animals manifestly do succeed in doing just that. It follows that it is meaningful to inquire as to how judgment is accomplished (say, through pacemaker-accumulator models), and it is meaningful to examine the psychophysical properties of the judgment process (like in the peak interval procedure). This fact structure makes a strong case that asking humans and other animals to judge event durations leads to productive and transparent science. The truth is, however, that this issue is far from settled, and it only appears to be so because the perspective that judgment offers is apparently not capable of recognizing that humans and other animals are uniquely ill-suited for judging the duration of events. A slight change in perspective will create an entirely different story. In that story the perception of time fails to form the kind of experiences that would allow durations beyond a couple of seconds to be apprehended as objects of judgment. This will, of course, necessitate a reevaluation of what was hitherto taken to be as obvious and manifest.

To understand what it means to experience a temporal duration it will be helpful to go back to Stevens’s law and examine what the law assumes about the nature of sensory experience. Recall that Stevens’ law is a relation between two things – between intensities, I, in the world and the subjective experience, ψ(I), of those intensities. More fundamentally, Stevens’ law articulates a kind of commonsense assumption about how mind is situated in the world. If a tree falls in the woods and there is an animal there also, does it make a sound? Of course it does. For every sound produced in the world in the presence of an animal with ears, there is an experience of that sound. The same comment applies to all sensory experience. The world impinges on the senses and experiences of the world ensue. That experiences attend sensory stimulation is practically what is meant by the “equal” sign that connects I to ψ(I) in Stevens’ law. This is what it means to have sensory experience, that for every I there is a ψ(I). It is the handshake between intensities and the experience of intensities that allows Stevens’ law to be written and for it to make sense. All of this is obvious, and that is the problem because there is one application of Stevens’ law where this handshake fails.

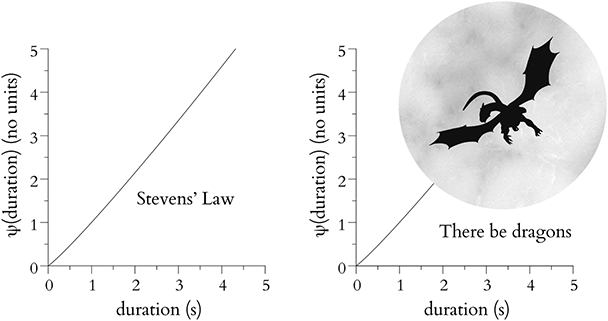

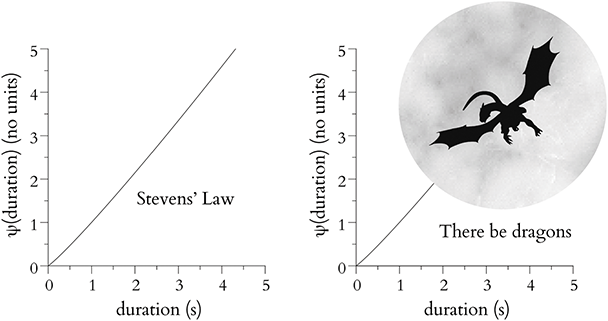

Let’s now apply Stevens’ law to the durations of events with a bit more care than was given in constructing Figure 1.1. It is important to be as clear as possible here. The “equal” sign in Stevens’ law entails that for every interval of world time there is a corresponding experience of the duration of that time interval. This statement seems so straightforward that it seems impossible that it could not be true. If that statement is acceptable, then so is the Stevens’ law plot of experienced duration shown on the left-hand side of Figure 1.6 (replotted from Figure 1.1). The plot does nothing more than give shape to the idea that the passage of time in the world is experienced. This is what allows a line to be drawn that connects world time to experienced time.

The point of departure of this book is that the left-hand side of Figure 1.6 does not paint a true picture of the experience of time passage. The true picture is depicted on the right-hand side. On the right-hand side, the Stevens’ law plot is interrupted by a dragon, marking the end of the known world. Dragons are appropriate here because it is not true that for every world duration there is an experience of that duration. Although it is true that there is no end to what duration an event might occupy, there are definite limits to what durations may be experienced. The y-axis, the axis of ψ(I) in fact ends after a few seconds. Beyond a few seconds there is a phase transition where the experience of duration essentially ends; there is no ψ(I) for durations, I, greater than a few seconds. In early cartography dragons were placed at the edge of the known world, and here dragons replace Stevens’ law at a couple of seconds. This is what a phase transition in time means: In the first few seconds of time passage there is a rich experience of time, so rich that it is felt. But beyond a few seconds, the passage of time becomes uncharted territory.

The perspective that leads to dragons flying into Stevens’ law is radically different from the judgment-driven perspective that regards time passage as just one more prothetic continuum, just one more dimension of experience. The perspective that sees dragons is known as Gestalt psychology. Gestalt is, to put it mildly and without prejudice, a very different kind of psychology than sensory psychophysics. Whereas sensory psychophysics is quite sophisticated and lives at the intersection of physics, biology, and mathematics, Gestalt, in contrast, is quite unsophisticated and lives at the intersection of philosophy, dialectic, and ecology. Nevertheless, Gestalt provides a conceptual framework for understanding the nature of human experience, and it provides the framework for understanding what is really going on with the experience of time passage.

The road to seeing dragons will not be long. In the next chapter the basic ideas that flow from Gestalt psychology will be introduced. Then in the chapter following, the phase transition in temporal experience will be introduced. The rest of the book will be about why there is a phase transition in human (and presumably mammalian) temporality and what the implications are for human temporality.

Perspective on the Psychophysics of Duration Judgment

There is undeniable evidence that humans and other animals can accurately judge the durations of time intervals. This evidence does not seem to be consistent with the Gestalt perspective on time, which insists that beyond durations of a few seconds there is no coherent or sensible experience of time. Evidently there is a distinction to be made here. It may not seem to be an important distinction, but it is central to understanding temporality. The distinction is between time passage, the t in the physical description of the world, and the history of events that occurs in consequence of time passage. Time and history are not the same thing, and they must be distinguished.

In psychology experiments that have to do with the judgment of time intervals there is the belief that it is time, physical time, that is being judged. This belief is explicitly reflected in the structure of SET. The core feature of SET is a pacemaker that is responding to the passage of physical time. The counts that are sent to the accumulator are a record of the passage of physical time and the counts that are stored in reference memory are records of previous passages of physical time. Literally every component of SET is based on physical time and just physical time. Put most simply, SET operates in terms of the time, t, that appears in physical descriptions of the world. Now, there is no question that animals may behave as if they are judging durations based on physical time, but if we deny that it is physical time that is being tracked, the need for SET and all similar theories of timing disappears. To be clear, duration judgment does require some form of memory. The proposition here is simply that a clock-based memory that stores physical time is not the right kind of memory.

History runs on a parallel track with time. On one track are moments, the stuff that makes time flow. On the other track are the things that happened at those moments. An animal that is aware of time passage may be tracking moments, perhaps by counting them in a clock manner as conceptualized by SET. Or the animal may just be aware of the flow of events that occurred before, say, a food pellet rolled out toward it. It happens that people and laboratory animals such as rats and pigeons do have memory for events, and this second track is always available. The two tracks are distinguished by their range: The existence of a phase transition in time does not affect the history track, it only affects the time track. So, although there may be no Stevens’ law, no ψ(I), for interval durations exceeding a few seconds, there is a continuous and virtually unlimited process of memory formation. Regardless of how time flows in experience and regardless of how that experience is structured by a phase transition, animals have a sense of their personal history, what is called their autobiographical or episodic memory. The proposition here is that episodic memory provides a continuum that can support duration judgment. Does not the narrative of our personal history keep us informed about interval durations – how long we have been looking for our keys, how long we have been waiting in line, how long it has been since we arrived at this stop light? In this view, experiments on duration judgment are not so much about the experience of time passage as they are about the experience of personal history. That leaves open the question of how time is, in fact, experienced. Answering that question is what this book is about. The point of departure is Gestalt.