1. Introduction

Wall-bounded turbulence is fundamental to a wide range of engineering and natural systems, governing critical processes such as skin-friction drag, heat and mass transfer and the onset of flow instabilities. The near-wall region, including the viscous sublayer, buffer layer and lower logarithmic layer, plays a dominant role in the dynamics of wall-bounded flows, as this is where turbulent kinetic energy is both generated and dissipated at the highest rates (Townsend Reference Townsend1961; Pope Reference Pope2001). Coherent structures in these regions, such as streamwise streaks and quasi-streamwise vortices, are known to mediate the transfer of momentum and energy across scales, and their spatiotemporal organisation governs the emergence of larger-scale turbulent motions farther from the wall (Adrian Reference Adrian2007; Hwang et al. Reference Hwang, Lee, Sung and Zaki2016). Therefore, near-wall turbulence has long been the focus of flow-control strategies aimed at reducing drag, delaying transition or enhancing mixing (Kim Reference Kim2007). However, implementing such strategies in practice demands high-fidelity instantaneous flow-field information, which remains challenging due to small spatial scales, high temporal variability and limited accessibility of measurements in this region.

Wall-mounted sensors, such as those measuring pressure or wall shear stress, are relatively easy to deploy, offering time-resolved, scalable and non-disruptive access to the surface signatures of near-wall turbulence (Löfdahl & Gad-el Hak Reference Löfdahl and Gad-el Hak1999; Choi, Moin & Kim Reference Choi, Moin and Kim1994). This practical advantage has naturally led to the question of whether it is possible to reconstruct the full, off-wall velocity field using only wall-based measurements. If successful, such reconstructions would enable closed-loop control, real-time flow monitoring and improved wall models for large-eddy simulations (LES) without requiring full-field sensing. The feasibility of this task is supported by the bidirectional coupling between near-wall and outer-layer structures (Zaki Reference Zaki2024). Large-scale motions in the logarithmic and outer regions of wall-bounded flows modulate the near-wall turbulence, leaving observable imprints on wall quantities (Abe, Kawamura & Choi Reference Abe, Kawamura and Choi2004; Mathis, Hutchins & Marusic Reference Mathis, Hutchins and Marusic2009; Hwang et al. Reference Hwang, Lee, Sung and Zaki2016). Conversely, energetic near-wall events can propagate their influence outward and modulate the coherence of large-scale motions in the outer layer (Adrian Reference Adrian2007; Lozano-Durán & Jiménez Reference Lozano-Durán and Jiménez2014). These bidirectional interactions have inspired extensive efforts to infer inner velocity fields from wall measurements. Physics-based strategies often leverage data assimilation techniques to integrate wall observations into high-fidelity simulations such as direct numerical simulations (DNS) or LES, thereby reconstructing the full flow state (Colburn, Cessna & Bewley Reference Colburn, Cessna and Bewley2011; Suzuki & Hasegawa Reference Suzuki and Hasegawa2017; Wang & Zaki Reference Wang and Zaki2025). While these methods benefit from governing equations that enforce physical consistency, they remain computationally prohibitive for most practical settings. Alternatively, resolvent analysis provides a linearised, reduced-order mapping between wall forcing and flow response (Amaral et al. Reference Amaral, Cavalieri, Martini, Jordan and Towne2021). While insightful, these models rely on simplifying assumptions (e.g. linearisation around a mean flow) and cannot fully capture the nonlinear and intermittent nature of near-wall turbulence.

On the other hand, data-driven methods offer an attractive alternative for flow estimation and reconstruction, particularly in scenarios where repeated measurements are available, and the underlying physics are too complex to be modelled directly. Early work using linear stochastic estimation (LSE) (Adrian & Moin Reference Adrian and Moin1988; Marusic, Mathis & Hutchins Reference Marusic, Mathis and Hutchins2010; Baars, Hutchins & Marusic Reference Baars, Hutchins and Marusic2016; Encinar & Jiménez Reference Encinar and Jiménez2019) and proper orthogonal decomposition (Towne, Schmidt & Colonius Reference Towne, Schmidt and Colonius2018) laid the foundation by extracting statistically dominant flow features and their correlations with wall signals. These techniques, however, are constrained by their linearity, and often fail to resolve the complex, multiscale turbulence structures. With the advent of deep learning, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and their variants have emerged as powerful tools for nonlinear flow estimation from wall data (Güemes et al. Reference Güemes, Discetti and Ianiro2019; Guastoni et al. Reference Guastoni, Güemes, Ianiro, Discetti, Schlatter, Azizpour and Vinuesa2021; Balasubramanian et al. Reference Balasubramanian, Guastoni, Schlatter, Azizpour and Vinuesa2023; Cuéllar et al. Reference Cuéllar, Güemes, Ianiro, Flores, Vinuesa and Discetti2024a ; Yousif et al. Reference Yousif, Yu, Hoyas, Vinuesa and Lim2023; Hora et al. Reference Hora, Gentine, Momen and Giometto2024). These models have demonstrated promising results in reconstructing velocity fields at various wall-normal locations using wall shear stress or pressure as input. Despite these advances, most of the existing approaches remain fundamentally deterministic and do not account for the inherent uncertainty of the reconstruction task, which arises from spatially heterogeneous correlations and variability in wall measurement quality, such as practical imperfections, induced sensor noise, limited spatial resolution and intrusive measurement effects. In regions where wall-flow coherence is strong (e.g. within the viscous sublayer), deterministic models may perform well. However, as the correlation decays with wall-normal distance, especially across the buffer and logarithmic layers (Wang, Wang & Zaki Reference Wang, Wang and Zaki2022; Arranz & Lozano-Durán Reference Arranz and Lozano-Durán2024), these models often fail to recover energetic but weakly observable flow features. Furthermore, practical limitations such as sensor sparsity, measurement noise and resolution constraints exacerbate this challenge, making the reconstruction problem increasingly ill-posed (Güemes et al. Reference Güemes, Discetti, Ianiro, Sirmacek, Azizpour and Vinuesa2021; Cuéllar et al. Reference Cuéllar, Ianiro and Discetti2024b ). As a result, deterministic models tend to produce overly smooth or biased estimates that suppress physically realistic variability. These limitations highlight the need for probabilistic modelling frameworks that not only generate physically consistent velocity features that are weakly correlated to wall quantities, but also quantify predictive uncertainty, enabling robust inference under imperfect or incomplete wall data.

Generative modelling, particularly when combined with Bayesian learning, offers a promising solution to these challenges. Rather than producing a single estimate, generative models learn the conditional distribution of turbulent velocity fields given wall measurements, enabling the synthesis of multiple physically plausible flow realisations that reflect both the informative and non-informative components of the flow with respect to wall data. Recent advances in generative AI, particularly diffusion-based models, have demonstrated impressive capabilities in synthesising high-fidelity flow realisations with accurate statistics (Rühling Cachay et al. Reference Rühling Cachay, Zhao, Joren and Yu2023; Kohl, Chen & Thuerey Reference Kohl, Chen and Thuerey2023; Li et al. Reference Li, Buzzicotti, Biferale, Bonaccorso, Chen and Wan2023; Shu, Li & Farimani Reference Shu, Li and Farimani2023; Dong, Chen & Wu Reference Dong, Chen and Wu2024; Du et al. Reference Du, Parikh, Fan, Liu and Wang2024; Gao et al. Reference Gao, Han, Fan, Sun, Liu, Duan and Wang2024a , Reference Gao, Kaltenbach and Koumoutsakosb ; Molinaro et al. Reference Molinaro2024; Fan, Akhare & Wang Reference Fan, Akhare and Wang2025; Gao, Kaltenbach & Koumoutsakos Reference Gao, Kaltenbach and Koumoutsakos2025; Shehata, Holzschuh & Thuerey Reference Shehata, Holzschuh and Thuerey2025; Zhuang, Cheng & Duraisamy Reference Zhuang, Cheng and Duraisamy2025). Specifically, Wang and co-workers have developed a conditional neural field-based latent diffusion model, which has been successfully demonstrated in generating spatiotemporal wall-bounded turbulence in three dimensions that is both inhomogeneous and anisotropic, enabling applications such as synthetic inflow turbulence generation and zero-shot spatiotemporal flow reconstruction (Du et al. Reference Du, Parikh, Fan, Liu and Wang2024; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Parikh, Fan, Du, Wang, Chen and Wang2025). However, diffusion-based sampling remains computationally expensive due to its iterative nature and is sensitive to posterior conditioning. Recently, flow matching has emerged as a scalable alternative to diffusion, offering fast and stable sampling by learning continuous-time transport maps between simple base distributions and complex data distributions through direct supervision (Lipman et al. Reference Lipman, Chen, Ben-Hamu, Nickel and Le2022).

In this work, we propose a novel generative learning framework for reconstructing near-wall turbulent velocity fields from wall-based measurements with quantified uncertainty. Specifically, we develop a conditional generative model that integrates conditional flow matching (Lipman et al. Reference Lipman, Chen, Ben-Hamu, Nickel and Le2022) with Bayesian neural operators trained using stochastic weight-averaging Gaussian (SWAG) (Maddox et al. Reference Maddox, Izmailov, Garipov, Vetrov and Wilson2019). The conditional-flow-matching-based model enables efficient generation of diverse, physically consistent instantaneous velocity fluctuation fields across multiple wall-normal locations, while the SWAG-based operator serves as a probabilistic forward model that maps velocity fields to wall measurements with quantified epistemic uncertainty. At inference time, our framework performs zero-shot conditional generation by iteratively refining sampled velocity fields to satisfy wall measurements – whether sparse, noisy or partial – without requiring re-training, transfer learning or fine-tuning.

To the best of our knowledge, this work presents the first attempt to leverage flow matching to reconstruct inhomogeneous and anisotropic turbulent velocity fluctuations at pre-defined wall-normal locations. Moreover, it is the first to demonstrate zero-shot conditional flow generation with uncertainty quantification in this context. By explicitly modelling both flow variability and predictive uncertainty, our framework addresses the ill-posed nature of near-wall turbulence reconstruction and enables robust, data-consistent inference under realistic sensing conditions. The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 details the methodology of the proposed generative modelling framework. Section 3 presents reconstruction results under varying sensor conditions, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed methods. Section 4 compares the performance of the proposed model against the state-of-the-art baseline methods and discusses each individual component of the proposed framework. Finally, § 5 summarises the key findings and outlines directions for future research.

2. Methodology

2.1. Problem formulation and analysis

This study tackles the challenge of reconstructing instantaneous velocity fluctuations at various wall-normal locations using only measurements acquired at the wall. The complexity of this task varies significantly across the near-wall region due to spatially heterogeneous correlations between wall measurements (e.g. wall shear stress) and turbulent structures in wall-bounded flows. Rather than focusing on a specific off-wall plane, our goal is to develop a general-purpose generative learning framework capable of synthesising physically realistic velocity fields throughout the entire near-wall region. Critically, the proposed framework explicitly quantifies predictive uncertainty, especially in regions where the coherence between wall signals and turbulent fluctuations is weak, or where wall measurements are sparse and contaminated by noise.

To better understand the inherent challenges associated with this reconstruction task, we first analyse the correlation between wall shear stress and velocity fluctuations across different wall-normal positions. As illustrated in figures 1(a) and 1(b), the correlation strength between wall shear stress and velocity fluctuations decreases sharply as the wall-normal distance (

![]() $y^+$

) increases. We note that this drop in correlation is slightly faster than that reported by Alfredsson et al. (Reference Alfredsson, Johansson, Haritonidis and Eckelmann1988) for two main reasons. First, our correlations are computed without incorporating any time lag, which is consistent with our entire framework. In contrast, Alfredsson et al. (Reference Alfredsson, Johansson, Haritonidis and Eckelmann1988) introduced a downstream displacement of approximately

$y^+$

) increases. We note that this drop in correlation is slightly faster than that reported by Alfredsson et al. (Reference Alfredsson, Johansson, Haritonidis and Eckelmann1988) for two main reasons. First, our correlations are computed without incorporating any time lag, which is consistent with our entire framework. In contrast, Alfredsson et al. (Reference Alfredsson, Johansson, Haritonidis and Eckelmann1988) introduced a downstream displacement of approximately

![]() $50l^*$

(where

$50l^*$

(where

![]() $l^*$

is the viscous length scale) between the wall shear stress probe and the velocity measurement, thereby accounting for the convective delay of coherent structures. Recent work by Arranz & Lozano-Durán (Reference Arranz and Lozano-Durán2024) shows that including such a lag typically increases the measured correlations. Second, the relatively low Reynolds number (

$l^*$

is the viscous length scale) between the wall shear stress probe and the velocity measurement, thereby accounting for the convective delay of coherent structures. Recent work by Arranz & Lozano-Durán (Reference Arranz and Lozano-Durán2024) shows that including such a lag typically increases the measured correlations. Second, the relatively low Reynolds number (

![]() $\textit{Re}_\tau =180$

) considered in our study contributes to the more rapid decay. As seen in figure 1(b), at

$\textit{Re}_\tau =180$

) considered in our study contributes to the more rapid decay. As seen in figure 1(b), at

![]() $y^+=100$

, the measurement point is already near the channel centre, where the influence of wall dynamics is weak and the correlation with wall shear stress naturally approaches zero. This reduction significantly limits the feasibility of accurately reconstructing instantaneous turbulent structures in outer regions using solely wall-based measurements (Suzuki & Hasegawa Reference Suzuki and Hasegawa2017; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wang and Zaki2022). Nonetheless, large-scale flow structures in the outer region leave subtle yet detectable imprints on the wall through amplitude and wavelength modulation effects, indirectly encoding useful information within wall shear stress fluctuations (Arranz & Lozano-Durán Reference Arranz and Lozano-Durán2024; Mathis et al. Reference Mathis, Hutchins and Marusic2009). Recognising this indirect yet informative coupling motivates our generative model, which aims to reconstruct instantaneous velocity fluctuations at various off-wall locations, incorporating uncertainty quantification that reflects the progressive weakening of coherence, measurement sparsity and observational noise.

$y^+=100$

, the measurement point is already near the channel centre, where the influence of wall dynamics is weak and the correlation with wall shear stress naturally approaches zero. This reduction significantly limits the feasibility of accurately reconstructing instantaneous turbulent structures in outer regions using solely wall-based measurements (Suzuki & Hasegawa Reference Suzuki and Hasegawa2017; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wang and Zaki2022). Nonetheless, large-scale flow structures in the outer region leave subtle yet detectable imprints on the wall through amplitude and wavelength modulation effects, indirectly encoding useful information within wall shear stress fluctuations (Arranz & Lozano-Durán Reference Arranz and Lozano-Durán2024; Mathis et al. Reference Mathis, Hutchins and Marusic2009). Recognising this indirect yet informative coupling motivates our generative model, which aims to reconstruct instantaneous velocity fluctuations at various off-wall locations, incorporating uncertainty quantification that reflects the progressive weakening of coherence, measurement sparsity and observational noise.

Figure 1. (a) Instantaneous streamwise velocity fluctuations

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}'$

of the turbulent channel flow (

$\boldsymbol{u}'$

of the turbulent channel flow (

![]() $\textit{Re}_\tau = 180$

) at three wall-normal locations (

$\textit{Re}_\tau = 180$

) at three wall-normal locations (

![]() $y^+ = 5, 20, 40$

) alongside the corresponding wall shear stress field

$y^+ = 5, 20, 40$

) alongside the corresponding wall shear stress field

![]() $\tau _{u}$

. (b) Correlation coefficients

$\tau _{u}$

. (b) Correlation coefficients

![]() $C_{\tau _u, {u}'}$

between wall shear stress and velocity fluctuations as a function of

$C_{\tau _u, {u}'}$

between wall shear stress and velocity fluctuations as a function of

![]() $y^+$

. (c) Reconstruction concept: given wall input

$y^+$

. (c) Reconstruction concept: given wall input

![]() ${\boldsymbol{\varPhi }}_{w\textit{all}}$

, the model (parametrised by

${\boldsymbol{\varPhi }}_{w\textit{all}}$

, the model (parametrised by

![]() $\boldsymbol{\theta }$

) predicts

$\boldsymbol{\theta }$

) predicts

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}'$

at different off-wall planes, with increasing uncertainty illustrated by blurred regions at higher

$\boldsymbol{u}'$

at different off-wall planes, with increasing uncertainty illustrated by blurred regions at higher

![]() $y^+$

.

$y^+$

.

Specifically, within the viscous sublayer, velocity fluctuations exhibit a nearly linear and direct relationship with wall measurements, characterised by a high correlation coefficient (

![]() $C_{\tau _{u} u'} \approx 1$

) (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wang and Zaki2022). Due to this strong coupling, velocity fields in this region can be reconstructed accurately with minimal uncertainty, as illustrated conceptually in figure 1(c). Moving outward into the buffer layer, however, this direct coherence rapidly decays (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wang and Zaki2022), even though this region is critical for turbulent kinetic energy production and hosts energetic coherent structures, such as streamwise streaks and hairpin vortices (Adrian Reference Adrian2007; Bae & Lee Reference Bae and Lee2021). These dynamically important structures are only indirectly captured by wall signals due to modulation effects, significantly complicating their instantaneous reconstruction. Thus, while the deterministic models can perform well in terms of mean prediction accuracy, they cannot capture the variability and provide predictive uncertainty that are particularly important in the buffer layer. This limitation underscores the need for probabilistic modelling approaches that explicitly quantify the uncertainty arising from weakened correlations and indirect observability. Further away from the wall (logarithmic layer and beyond), large-scale turbulent motions, particularly low-speed streaks, persist and can extend significantly into the outer layer, sometimes reaching the boundary-layer edge (Adrian Reference Adrian2007; Encinar & Jiménez Reference Encinar and Jiménez2019). Although their instantaneous correlation with wall signals is generally low, these large-scale structures indirectly influence near-wall dynamics through modulation effects, leaving distinguishable but indirect signatures on wall quantities (Arranz & Lozano-Durán Reference Arranz and Lozano-Durán2024; Mathis et al. Reference Mathis, Hutchins and Marusic2009). Despite being less dominant energetically compared with smaller-scale structures nearer to the wall, accurately capturing their statistical features remains essential to realistically reconstruct turbulence characteristics. Deterministic methods relying solely on wall measurements often significantly underestimate fluctuations in this region, as they only recover weakly correlated, low-energy large-scale motions (Guastoni et al. Reference Guastoni, Güemes, Ianiro, Discetti, Schlatter, Azizpour and Vinuesa2021). Recognising this limitation, our framework not only predicts informative components directly from wall data, but also leverages generative learning to synthesise non-informative yet energetically crucial turbulence structures, thereby ensuring accurate statistical reconstructions.

$C_{\tau _{u} u'} \approx 1$

) (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wang and Zaki2022). Due to this strong coupling, velocity fields in this region can be reconstructed accurately with minimal uncertainty, as illustrated conceptually in figure 1(c). Moving outward into the buffer layer, however, this direct coherence rapidly decays (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Wang and Zaki2022), even though this region is critical for turbulent kinetic energy production and hosts energetic coherent structures, such as streamwise streaks and hairpin vortices (Adrian Reference Adrian2007; Bae & Lee Reference Bae and Lee2021). These dynamically important structures are only indirectly captured by wall signals due to modulation effects, significantly complicating their instantaneous reconstruction. Thus, while the deterministic models can perform well in terms of mean prediction accuracy, they cannot capture the variability and provide predictive uncertainty that are particularly important in the buffer layer. This limitation underscores the need for probabilistic modelling approaches that explicitly quantify the uncertainty arising from weakened correlations and indirect observability. Further away from the wall (logarithmic layer and beyond), large-scale turbulent motions, particularly low-speed streaks, persist and can extend significantly into the outer layer, sometimes reaching the boundary-layer edge (Adrian Reference Adrian2007; Encinar & Jiménez Reference Encinar and Jiménez2019). Although their instantaneous correlation with wall signals is generally low, these large-scale structures indirectly influence near-wall dynamics through modulation effects, leaving distinguishable but indirect signatures on wall quantities (Arranz & Lozano-Durán Reference Arranz and Lozano-Durán2024; Mathis et al. Reference Mathis, Hutchins and Marusic2009). Despite being less dominant energetically compared with smaller-scale structures nearer to the wall, accurately capturing their statistical features remains essential to realistically reconstruct turbulence characteristics. Deterministic methods relying solely on wall measurements often significantly underestimate fluctuations in this region, as they only recover weakly correlated, low-energy large-scale motions (Guastoni et al. Reference Guastoni, Güemes, Ianiro, Discetti, Schlatter, Azizpour and Vinuesa2021). Recognising this limitation, our framework not only predicts informative components directly from wall data, but also leverages generative learning to synthesise non-informative yet energetically crucial turbulence structures, thereby ensuring accurate statistical reconstructions.

Figure 2. (a) Flow-matching-based generative model

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nu }_{\boldsymbol{\theta }}$

for synthesising novel instances of velocity fluctuations

$\boldsymbol{\nu }_{\boldsymbol{\theta }}$

for synthesising novel instances of velocity fluctuations

![]() $(u',\ v',\ w')$

. (b) Forward operator with SWAG

$(u',\ v',\ w')$

. (b) Forward operator with SWAG

![]() $\mathcal{F}_{\boldsymbol{\phi }}$

to quantify the epistemic uncertainty between velocity fluctuations

$\mathcal{F}_{\boldsymbol{\phi }}$

to quantify the epistemic uncertainty between velocity fluctuations

![]() $(u',\ v',\ w')$

and wall quantities

$(u',\ v',\ w')$

and wall quantities

![]() $(p',\ \tau _u,\ \tau _w)$

. (c) Training-free conditional generation based on the predictor–corrector FM inference algorithm using conditional information

$(p',\ \tau _u,\ \tau _w)$

. (c) Training-free conditional generation based on the predictor–corrector FM inference algorithm using conditional information

![]() $\boldsymbol{y}$

.

$\boldsymbol{y}$

.

2.2. Overview of proposed generative modelling framework for near-wall turbulence

Building upon our analysis of spatially heterogeneous correlations between wall measurements and turbulent structures, we propose a generative modelling framework explicitly designed to reconstruct instantaneous velocity fluctuations across multiple wall-normal locations. Specifically, a representative wall-normal location from each of the viscous sublayer, buffer and logarithmic layers is chosen to systematically evaluate the data assimilation and uncertainty quantification capabilities of the proposed generative framework. The comprehensiveness of this test stems from assessing the framework’s performance in three distinct regimes based on the classification introduced in Arranz & Lozano-Durán (Reference Arranz and Lozano-Durán2024): the highly informative viscous sublayer (

![]() $y^+=5$

), the partially informative buffer layer (

$y^+=5$

), the partially informative buffer layer (

![]() $y^+=20$

) and the almost non-informative logarithmic layer (

$y^+=20$

) and the almost non-informative logarithmic layer (

![]() $y^+=40$

). This approach provides a thorough analysis of the proposed framework across different operating conditions. The core idea of the framework leverages generative learning combined with probabilistic neural operators within a Bayesian framework to effectively handle the inherent uncertainties and indirect observability in wall-bounded turbulence. Figure 2 illustrates the three key components of our framework.

$y^+=40$

). This approach provides a thorough analysis of the proposed framework across different operating conditions. The core idea of the framework leverages generative learning combined with probabilistic neural operators within a Bayesian framework to effectively handle the inherent uncertainties and indirect observability in wall-bounded turbulence. Figure 2 illustrates the three key components of our framework.

In the training phase (figure 2

a), a generative model based on flow matching (Lipman et al. Reference Lipman, Chen, Ben-Hamu, Nickel and Le2022) is built to generate instantaneous full-field velocity fluctuation samples at pre-defined wall-normal positions (

![]() $y^+ = 5, 20, 40$

) by sampling from a standard Gaussian distribution,

$y^+ = 5, 20, 40$

) by sampling from a standard Gaussian distribution,

![]() $\mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{0}, \boldsymbol{I})$

. The trained model is able to randomly synthesise novel, physically plausible instantaneous velocity fluctuation fields consistent with the statistical features observed in turbulent channel flows. The details of the flow-matching training are further elaborated in § 2.3. Concurrently, as depicted in figure 2(b), a probabilistic neural operator is designed to predict wall quantities (e.g. wall shear stresses and pressures) from the velocity fluctuations with quantified uncertainties. This U-Net-based neural operator is trained probabilistically using SWAG (Maddox et al. Reference Maddox, Izmailov, Garipov, Vetrov and Wilson2019), a Bayesian learning technique enabling the quantification of epistemic uncertainty inherent in neural network predictions. The incorporation of the SWAG operator is critical as it allows our framework to explicitly learn the uncertainty arising from weak correlations, measurement sparsity and noise. As the generative model and the SWAG neural operator utilised in this work are based on CNNs, the current formulation requires access to the entire field of velocity fluctuations and wall measurements on a uniform grid during the training process.

$\mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{0}, \boldsymbol{I})$

. The trained model is able to randomly synthesise novel, physically plausible instantaneous velocity fluctuation fields consistent with the statistical features observed in turbulent channel flows. The details of the flow-matching training are further elaborated in § 2.3. Concurrently, as depicted in figure 2(b), a probabilistic neural operator is designed to predict wall quantities (e.g. wall shear stresses and pressures) from the velocity fluctuations with quantified uncertainties. This U-Net-based neural operator is trained probabilistically using SWAG (Maddox et al. Reference Maddox, Izmailov, Garipov, Vetrov and Wilson2019), a Bayesian learning technique enabling the quantification of epistemic uncertainty inherent in neural network predictions. The incorporation of the SWAG operator is critical as it allows our framework to explicitly learn the uncertainty arising from weak correlations, measurement sparsity and noise. As the generative model and the SWAG neural operator utilised in this work are based on CNNs, the current formulation requires access to the entire field of velocity fluctuations and wall measurements on a uniform grid during the training process.

In the inference stage, depicted in figure 2(c), our framework is able to perform conditional generation in a zero-shot manner (i.e. without re-training) using a predictor–corrector sampling approach. Specifically, given instantaneous wall measurements, the pre-trained generative model synthesises instantaneous velocity fluctuation fields that are consistent with these sensor data. This is accomplished through iterative refinement, where an initial prediction from the generative model is progressively updated using gradient-based corrections derived from discrepancies between predicted and actual wall data. The gradients are computed via the differentiable forward measurement model integrated with the probabilistic SWAG operator, thereby ensuring that the synthesised velocity fluctuations realistically reflect measurement uncertainties and the physical constraints imposed by available wall information. Further details are provided in § 2.4.

In summary, our proposed generative modelling framework uniquely integrates generative learning and scalable uncertainty quantification techniques, providing robust and physically consistent reconstructions of turbulent velocity fluctuations from limited wall-based measurements.

2.3. Flow matching for generative modelling of instantaneous velocity fluctuations

To model the complex, high-dimensional distribution of instantaneous velocity fluctuations in near-wall turbulence, we adopt the recently proposed flow matching (FM) framework (Lipman et al. Reference Lipman, Chen, Ben-Hamu, Nickel and Le2022), which enables tractable and scalable training of continuous normalising flows by directly learning the velocity fields that transport probability mass from a simple base distribution to the target data distribution. Unlike conventional continuous normalising flows, which require density estimation via the change-of-variables formula and involve solving ordinary differential equations (ODEs) during training, FM bypasses these limitations by re-framing the generative modelling as a regression task over velocity fields that define transport paths between distributions. This makes FM particularly suitable for large-scale, high-dimensional turbulent flow data. In this work, we present the first use of FM to generate inhomogeneous, anisotropic turbulence by reconstructing the three velocity fluctuation components at the chosen wall-normal positions (

![]() $y^+ = 5, 20, 40$

).

$y^+ = 5, 20, 40$

).

Let

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}_1 \sim P_1(\boldsymbol{x})$

denote a sample drawn from the target data distribution, where each sample represents a snapshot of the instantaneous three-component velocity fluctuation field at a specified wall-normal location

$\boldsymbol{x}_1 \sim P_1(\boldsymbol{x})$

denote a sample drawn from the target data distribution, where each sample represents a snapshot of the instantaneous three-component velocity fluctuation field at a specified wall-normal location

![]() $y^+$

. Specifically,

$y^+$

. Specifically,

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}_1 = [u'(x, z, t), v'(x, z, t), w'(x, z, t)]$

are defined on a discrete

$\boldsymbol{x}_1 = [u'(x, z, t), v'(x, z, t), w'(x, z, t)]$

are defined on a discrete

![]() $(x, z)$

grid, where

$(x, z)$

grid, where

![]() $x, z$

are wall-parallel coordinates and

$x, z$

are wall-parallel coordinates and

![]() $t$

denotes physical time. We define the base distribution

$t$

denotes physical time. We define the base distribution

![]() $P_0(\boldsymbol{x}) = \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{0}, \boldsymbol{I})$

as a standard multivariate Gaussian in the same space as the target data. Our goal is to learn a transport neural velocity field

$P_0(\boldsymbol{x}) = \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{0}, \boldsymbol{I})$

as a standard multivariate Gaussian in the same space as the target data. Our goal is to learn a transport neural velocity field

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nu }_{\boldsymbol{\theta }}(\tau , \boldsymbol{x}_\tau )$

, parametrised by neural network weights

$\boldsymbol{\nu }_{\boldsymbol{\theta }}(\tau , \boldsymbol{x}_\tau )$

, parametrised by neural network weights

![]() $\boldsymbol{\theta }$

, that smoothly transforms samples from

$\boldsymbol{\theta }$

, that smoothly transforms samples from

![]() $P_0$

into samples from

$P_0$

into samples from

![]() $P_1$

along a continuous path indexed by a fictitious time variable

$P_1$

along a continuous path indexed by a fictitious time variable

![]() $\tau \in [0, 1]$

. The generative process is defined by the flow ODE

$\tau \in [0, 1]$

. The generative process is defined by the flow ODE

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}_\tau$

denotes the sample at intermediate time

$\boldsymbol{x}_\tau$

denotes the sample at intermediate time

![]() $\tau$

along the transport trajectory from

$\tau$

along the transport trajectory from

![]() $P_0$

to

$P_0$

to

![]() $P_1$

.

$P_1$

.

To ensure probability conservation along the flow, the transport velocity field

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nu }(\tau , \boldsymbol{x}_\tau )$

must satisfy the continuity equation

$\boldsymbol{\nu }(\tau , \boldsymbol{x}_\tau )$

must satisfy the continuity equation

where

![]() $P_\tau (\boldsymbol{x})$

denotes the intermediate distribution at time

$P_\tau (\boldsymbol{x})$

denotes the intermediate distribution at time

![]() $\tau$

. If the true velocity field

$\tau$

. If the true velocity field

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nu }(\tau , \boldsymbol{x}_\tau )$

is known, we can directly minimise the following loss:

$\boldsymbol{\nu }(\tau , \boldsymbol{x}_\tau )$

is known, we can directly minimise the following loss:

In practice, however, directly evaluating the true velocity

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nu }(\tau , \boldsymbol{x}_\tau )$

and sampling from

$\boldsymbol{\nu }(\tau , \boldsymbol{x}_\tau )$

and sampling from

![]() $P_\tau (\boldsymbol{x}_\tau )$

is intractable. To address this, FM introduces a conditional formulation by introducing a latent variable

$P_\tau (\boldsymbol{x}_\tau )$

is intractable. To address this, FM introduces a conditional formulation by introducing a latent variable

![]() $\boldsymbol{z} \sim q(\boldsymbol{z})$

that leads to conditional intermediate distributions

$\boldsymbol{z} \sim q(\boldsymbol{z})$

that leads to conditional intermediate distributions

![]() $P_\tau (\boldsymbol{x}|\boldsymbol{z})$

and velocities

$P_\tau (\boldsymbol{x}|\boldsymbol{z})$

and velocities

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nu }(\boldsymbol{x}_\tau |\boldsymbol{z})$

, such that

$\boldsymbol{\nu }(\boldsymbol{x}_\tau |\boldsymbol{z})$

, such that

Substituting (2.3) into the FM loss and swapping the gradient and expectation under suitable regularity conditions leads to the modified loss:

Under certain assumptions on

![]() $q(\boldsymbol{z})$

and

$q(\boldsymbol{z})$

and

![]() $P_\tau (\boldsymbol{x}_\tau |\boldsymbol{z})$

(Lipman et al. Reference Lipman, Chen, Ben-Hamu, Nickel and Le2022), it can be proved that the gradient of the modified loss yields the same optimisation objective as the original FM loss, i.e.

$P_\tau (\boldsymbol{x}_\tau |\boldsymbol{z})$

(Lipman et al. Reference Lipman, Chen, Ben-Hamu, Nickel and Le2022), it can be proved that the gradient of the modified loss yields the same optimisation objective as the original FM loss, i.e.

Therefore, the neural velocity field can be trained based on the conditional formulation of the loss function, where both the conditional intermediate distributions and velocities are available. In practice, we use empirical samples from the data distribution as conditioning variables. Specifically, we let

![]() $q(\boldsymbol{z}) = (1/N) \sum _{i=1}^{N} \delta (\boldsymbol{z} - \boldsymbol{x}_1^{(i)})$

, where

$q(\boldsymbol{z}) = (1/N) \sum _{i=1}^{N} \delta (\boldsymbol{z} - \boldsymbol{x}_1^{(i)})$

, where

![]() $\{\boldsymbol{x}_1^{(i)}\}_{i=1}^N$

are training velocity fluctuation data. Then we have the following tractable definitions for the conditional intermediate distribution and velocity:

$\{\boldsymbol{x}_1^{(i)}\}_{i=1}^N$

are training velocity fluctuation data. Then we have the following tractable definitions for the conditional intermediate distribution and velocity:

which corresponds to an isotropic Gaussian interpolation with linearly evolving mean and covariance from

![]() $\mathcal{N}(0, \boldsymbol{I})$

to

$\mathcal{N}(0, \boldsymbol{I})$

to

![]() $\mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{x}_1, \sigma _{\textit{min}}^2 \boldsymbol{I})$

. Here, the mean interpolates linearly from

$\mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{x}_1, \sigma _{\textit{min}}^2 \boldsymbol{I})$

. Here, the mean interpolates linearly from

![]() $\boldsymbol{0}$

to

$\boldsymbol{0}$

to

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}_1$

, while the covariance linearly decays from

$\boldsymbol{x}_1$

, while the covariance linearly decays from

![]() $\boldsymbol{I}$

to

$\boldsymbol{I}$

to

![]() $\sigma _{\textit{min}}^2 \boldsymbol{I}$

. This results in a simple and tractable sampling scheme, where both the intermediate samples

$\sigma _{\textit{min}}^2 \boldsymbol{I}$

. This results in a simple and tractable sampling scheme, where both the intermediate samples

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}_\tau$

and their associated transport velocities

$\boldsymbol{x}_\tau$

and their associated transport velocities

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nu }(\tau , \boldsymbol{x}_\tau | \boldsymbol{x}_1)$

are available in closed form for supervised training. Additionally, the neural velocity field

$\boldsymbol{\nu }(\tau , \boldsymbol{x}_\tau | \boldsymbol{x}_1)$

are available in closed form for supervised training. Additionally, the neural velocity field

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nu }_{\boldsymbol{\theta }}(\tau , \boldsymbol{x}_\tau )$

is trained in a class-conditional way for the different wall-normal distances of

$\boldsymbol{\nu }_{\boldsymbol{\theta }}(\tau , \boldsymbol{x}_\tau )$

is trained in a class-conditional way for the different wall-normal distances of

![]() $y^+=\{5,\, 20,\, 40\}$

considered in this study. The model learns a trainable neural embedding corresponding to each wall-normal distance. The details of network architectures are provided in Appendix A.

$y^+=\{5,\, 20,\, 40\}$

considered in this study. The model learns a trainable neural embedding corresponding to each wall-normal distance. The details of network architectures are provided in Appendix A.

Once the FM model

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nu }_{\boldsymbol{\theta }}$

is trained, novel samples of the velocity fluctuations are generated by sampling from

$\boldsymbol{\nu }_{\boldsymbol{\theta }}$

is trained, novel samples of the velocity fluctuations are generated by sampling from

![]() $P_0(\boldsymbol{x}_0)$

and solving the ODE in (2.1) by integrating

$P_0(\boldsymbol{x}_0)$

and solving the ODE in (2.1) by integrating

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nu }_{\boldsymbol{\theta }}(\tau , \boldsymbol{x}_\tau )$

over the fictitious time interval

$\boldsymbol{\nu }_{\boldsymbol{\theta }}(\tau , \boldsymbol{x}_\tau )$

over the fictitious time interval

![]() $\tau \in [0,1]$

. In this work, we employ a forward Euler scheme, and discretise the fictitious time domain into

$\tau \in [0,1]$

. In this work, we employ a forward Euler scheme, and discretise the fictitious time domain into

![]() $250$

uniform steps.

$250$

uniform steps.

2.4. Training-free conditional generation guided by wall measurements

The generative model described in § 2.3 enables efficient sampling of instantaneous velocity fluctuation fields from the learned distribution at specified wall-normal locations. While this unconditional generation captures the statistical structure of turbulent fluctuations, it does not incorporate any instance-specific observations. In practical settings, however, partial information about a specific turbulent flow realisation is often available, either in the form of direct but sparse velocity measurements within the domain or, more commonly, through indirect wall-based observations such as wall shear stress or pressure signals. These measurements

![]() $\boldsymbol{y}$

encode valuable information about the underlying flow state and can be leveraged during inference. This motivates the need for conditional generative inference that can synthesise velocity fields consistent with available observations, while retaining uncertainty quantification over unobserved regions.

$\boldsymbol{y}$

encode valuable information about the underlying flow state and can be leveraged during inference. This motivates the need for conditional generative inference that can synthesise velocity fields consistent with available observations, while retaining uncertainty quantification over unobserved regions.

A common strategy to condition generative models is to incorporate the observation vector

![]() $\boldsymbol{y}$

, whether wall measurements, sparse velocity probes, or both, into the sampling process. This is typically achieved by modifying the training objective to explicitly encode

$\boldsymbol{y}$

, whether wall measurements, sparse velocity probes, or both, into the sampling process. This is typically achieved by modifying the training objective to explicitly encode

![]() $\boldsymbol{y}$

as input, for example through input concatenation, modulation via feature-wise affine transformations, or injection via a hypernetwork

$\boldsymbol{y}$

as input, for example through input concatenation, modulation via feature-wise affine transformations, or injection via a hypernetwork

![]() $F_\phi (\boldsymbol{y})$

(Dhariwal & Nichol Reference Dhariwal and Nichol2021; Fu et al. Reference Fu, Yang, Wang and Chen2024; Jacobsen, Zhuang & Duraisamy Reference Jacobsen, Zhuang and Duraisamy2025; Zhuang et al. Reference Zhuang, Cheng and Duraisamy2025). However, these approaches require re-training the generative model for each new type of conditioning input and often scale poorly when the structure, modality or spatial extent of

$F_\phi (\boldsymbol{y})$

(Dhariwal & Nichol Reference Dhariwal and Nichol2021; Fu et al. Reference Fu, Yang, Wang and Chen2024; Jacobsen, Zhuang & Duraisamy Reference Jacobsen, Zhuang and Duraisamy2025; Zhuang et al. Reference Zhuang, Cheng and Duraisamy2025). However, these approaches require re-training the generative model for each new type of conditioning input and often scale poorly when the structure, modality or spatial extent of

![]() $\boldsymbol{y}$

varies across instances, as is the case in sensor-limited turbulence set-ups.

$\boldsymbol{y}$

varies across instances, as is the case in sensor-limited turbulence set-ups.

To overcome these limitations, we introduce a training-free conditional inference strategy that augments the unconditional FM model with a correction term derived from the conditioning measurements. Inspired by training-free conditional methods in diffusion models such as diffusion posterior sampling (Chung et al. Reference Chung, Kim, Mccann, Klasky and Ye2022; Du et al. Reference Du, Parikh, Fan, Liu and Wang2024) and Bayesian classifier guidance (Dhariwal & Nichol Reference Dhariwal and Nichol2021; Gao et al. Reference Gao, Han, Fan, Sun, Liu, Duan and Wang2024a

), our approach adapts these ideas to the FM paradigm. Specifically, we define a guided sampling procedure in which the learned transport velocity

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nu }_{\boldsymbol{\theta }}(\tau , \boldsymbol{x}_\tau )$

is augmented during inference by a correction term

$\boldsymbol{\nu }_{\boldsymbol{\theta }}(\tau , \boldsymbol{x}_\tau )$

is augmented during inference by a correction term

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nu }'(\tau , \boldsymbol{x}_\tau , \boldsymbol{y})$

that nudges the generative trajectory towards compatibility with the measurements:

$\boldsymbol{\nu }'(\tau , \boldsymbol{x}_\tau , \boldsymbol{y})$

that nudges the generative trajectory towards compatibility with the measurements:

To derive this correction term, we first assess the discrepancy between the observations

![]() $\boldsymbol{y}$

and the predicted measurements

$\boldsymbol{y}$

and the predicted measurements

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol{y}}$

derived from the current state

$\hat {\boldsymbol{y}}$

derived from the current state

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}_\tau$

, and then propagate this discrepancy back to

$\boldsymbol{x}_\tau$

, and then propagate this discrepancy back to

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}_\tau$

. This process involves three components: (i) an efficient approximation of the terminal state

$\boldsymbol{x}_\tau$

. This process involves three components: (i) an efficient approximation of the terminal state

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol{x}}_1$

from intermediate states

$\hat {\boldsymbol{x}}_1$

from intermediate states

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}_\tau$

, (ii) a forward state-to-observable operator that maps the generated state to measurement space and (iii) a differentiable loss to quantify mismatch between predicted and observed measurements. In the first step, the target guidance field (2.7

b) defines a straight interpolation in data space between the noise sample and the data sample. Accordingly, we employ a one-step linear approximation of the terminal state (Lipman et al. Reference Lipman, Chen, Ben-Hamu, Nickel and Le2022):

$\boldsymbol{x}_\tau$

, (ii) a forward state-to-observable operator that maps the generated state to measurement space and (iii) a differentiable loss to quantify mismatch between predicted and observed measurements. In the first step, the target guidance field (2.7

b) defines a straight interpolation in data space between the noise sample and the data sample. Accordingly, we employ a one-step linear approximation of the terminal state (Lipman et al. Reference Lipman, Chen, Ben-Hamu, Nickel and Le2022):

which estimates the endpoint of the flow by extrapolating along the learned transport velocity. This is computationally efficient and justified by the nearly linear nature of the flow trajectory learned through conditional flow matching (§ 2.3). Next, we define the forward operator

![]() $\mathcal{F}$

that maps the predicted state

$\mathcal{F}$

that maps the predicted state

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol{x}}_{1|\tau }$

to the observable domain. Depending on the context,

$\hat {\boldsymbol{x}}_{1|\tau }$

to the observable domain. Depending on the context,

![]() $\mathcal{F}$

may represent a fixed linear mapping (e.g. extracting velocity values at sensor locations) or a learned neural operator that maps the off-wall flow states to indirect measurements (e.g. wall measurements). Considering measurement noises

$\mathcal{F}$

may represent a fixed linear mapping (e.g. extracting velocity values at sensor locations) or a learned neural operator that maps the off-wall flow states to indirect measurements (e.g. wall measurements). Considering measurement noises

![]() $\boldsymbol{\epsilon }$

, this operator is defined as

$\boldsymbol{\epsilon }$

, this operator is defined as

where

![]() $\varSigma _e = \sigma _e^2 \boldsymbol{I}$

captures the assumed level of aleatoric uncertainty. The aleatoric uncertainty is assumed to be a Gaussian distribution to model the measurement error of the sensors that commonly arises from the thermal or electronic noise.

$\varSigma _e = \sigma _e^2 \boldsymbol{I}$

captures the assumed level of aleatoric uncertainty. The aleatoric uncertainty is assumed to be a Gaussian distribution to model the measurement error of the sensors that commonly arises from the thermal or electronic noise.

The discrepancy

![]() $\mathscr{D}(\hat {\boldsymbol{y}}, \boldsymbol{y})$

between predicted and observed measurements is quantified via a loss function, typically the mean squared error. This loss is then differentiated with respect to

$\mathscr{D}(\hat {\boldsymbol{y}}, \boldsymbol{y})$

between predicted and observed measurements is quantified via a loss function, typically the mean squared error. This loss is then differentiated with respect to

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}_\tau$

, yielding a gradient that points in the direction of greater alignment between the generated sample and the observations. We define the correction term as

$\boldsymbol{x}_\tau$

, yielding a gradient that points in the direction of greater alignment between the generated sample and the observations. We define the correction term as

where

![]() $b$

is a scalar that controls the guidance strength, and is set to

$b$

is a scalar that controls the guidance strength, and is set to

![]() $1$

for all the experiments considered in this study. The correction direction is aligned with the normalised loss gradient, while the magnitude is scaled to match the norm of the current transport velocity, ensuring that the guidance term and learned flow are balanced in strength.

$1$

for all the experiments considered in this study. The correction direction is aligned with the normalised loss gradient, while the magnitude is scaled to match the norm of the current transport velocity, ensuring that the guidance term and learned flow are balanced in strength.

Importantly, this conditional sampling strategy is agnostic to the nature and modality of the measurement vector

![]() $\boldsymbol{y}$

. While in this paper we focus on wall-based observations, the framework can also accommodate sparse velocity probes, inpainting of partially known flow fields or any other differentiable observation models. In fact, the proposed corrector can be viewed as a variational approximation to the gradient of the log-posterior distribution

$\boldsymbol{y}$

. While in this paper we focus on wall-based observations, the framework can also accommodate sparse velocity probes, inpainting of partially known flow fields or any other differentiable observation models. In fact, the proposed corrector can be viewed as a variational approximation to the gradient of the log-posterior distribution

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\boldsymbol{x}} \log P(\boldsymbol{y} | \boldsymbol{x})$

, and thus relates conceptually to likelihood-based guidance in diffusion posterior sampling (Chung et al. Reference Chung, Kim, Mccann, Klasky and Ye2022; Du et al. Reference Du, Parikh, Fan, Liu and Wang2024; Gao et al. Reference Gao, Han, Fan, Sun, Liu, Duan and Wang2024a

). We demonstrate the flexibility and effectiveness of this approach through reconstruction experiments with wall-based and in-domain conditional signals in § 3, and further illustrate its applicability to sparse inpainting tasks in § 4.4.

$\boldsymbol{\nabla} _{\boldsymbol{x}} \log P(\boldsymbol{y} | \boldsymbol{x})$

, and thus relates conceptually to likelihood-based guidance in diffusion posterior sampling (Chung et al. Reference Chung, Kim, Mccann, Klasky and Ye2022; Du et al. Reference Du, Parikh, Fan, Liu and Wang2024; Gao et al. Reference Gao, Han, Fan, Sun, Liu, Duan and Wang2024a

). We demonstrate the flexibility and effectiveness of this approach through reconstruction experiments with wall-based and in-domain conditional signals in § 3, and further illustrate its applicability to sparse inpainting tasks in § 4.4.

2.5. Learning forward operators from velocity fields to wall measurements with uncertainty

As established in § 2.4, our conditional generation framework requires evaluating the discrepancy between synthesised velocity fields and observed flow measurements, which depends on a forward operator

![]() $\mathcal{F}$

that maps the generated velocity fluctuation field

$\mathcal{F}$

that maps the generated velocity fluctuation field

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}'$

to predicted measurements

$\boldsymbol{u}'$

to predicted measurements

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol{y}} = \mathcal{F}(\boldsymbol{u}')$

. In general,

$\hat {\boldsymbol{y}} = \mathcal{F}(\boldsymbol{u}')$

. In general,

![]() $\boldsymbol{y}$

may consist of direct velocity samples at sparse spatial locations or, more commonly, wall-based signals such as pressure or shear stress, which are nonlinearly related to the off-wall velocity field. While mapping from velocity to sparse velocity measurements can often be expressed as a linear masking operation, the velocity-to-wall mapping is inherently nonlinear and spatially non-local, reflecting the complex modulation mechanisms by which outer-layer motions influence near-wall quantities (Mathis et al. Reference Mathis, Hutchins and Marusic2009; Arranz & Lozano-Durán Reference Arranz and Lozano-Durán2024).

$\boldsymbol{y}$

may consist of direct velocity samples at sparse spatial locations or, more commonly, wall-based signals such as pressure or shear stress, which are nonlinearly related to the off-wall velocity field. While mapping from velocity to sparse velocity measurements can often be expressed as a linear masking operation, the velocity-to-wall mapping is inherently nonlinear and spatially non-local, reflecting the complex modulation mechanisms by which outer-layer motions influence near-wall quantities (Mathis et al. Reference Mathis, Hutchins and Marusic2009; Arranz & Lozano-Durán Reference Arranz and Lozano-Durán2024).

To enable training-free conditional inference using wall measurements, we need a forward observation operator, which should be differentiable and capable of quantifying predictive uncertainty, especially where the velocity–wall correlation is weak. This is particularly important because in regions such as the logarithmic layer, wall signals encode only indirect and noisy information about the flow. The forward operator must therefore propagate not only observations but also their epistemic confidence into the sampling process. To this end, we design a probabilistic forward operator

![]() $\mathcal{F}_{\boldsymbol{\phi }}$

, built as a convolutional U-Net, that learns to predict wall measurements

$\mathcal{F}_{\boldsymbol{\phi }}$

, built as a convolutional U-Net, that learns to predict wall measurements

![]() $\boldsymbol{\varPhi }_{w\textit{all}} = [p, \tau _u, \tau _w]$

from input three-dimensional velocity fluctuations

$\boldsymbol{\varPhi }_{w\textit{all}} = [p, \tau _u, \tau _w]$

from input three-dimensional velocity fluctuations

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}' = [u', v', w']$

. A different forward operator is trained for each wall-normal distance. Crucially, to enable robust uncertainty-aware conditioning during inference, we train

$\boldsymbol{u}' = [u', v', w']$

. A different forward operator is trained for each wall-normal distance. Crucially, to enable robust uncertainty-aware conditioning during inference, we train

![]() $\mathcal{F}_{\boldsymbol{\phi }}$

using the SWAG framework (Maddox et al. Reference Maddox, Izmailov, Garipov, Vetrov and Wilson2019), which approximates the posterior distribution over the network parameters and propagates uncertainty through the prediction. Specifically, we treat the operator’s parameters

$\mathcal{F}_{\boldsymbol{\phi }}$

using the SWAG framework (Maddox et al. Reference Maddox, Izmailov, Garipov, Vetrov and Wilson2019), which approximates the posterior distribution over the network parameters and propagates uncertainty through the prediction. Specifically, we treat the operator’s parameters

![]() $\boldsymbol{\phi }$

as a distribution rather than a point estimate, modelling their posterior as a multivariate Gaussian with a diagonal plus low-rank covariance structure:

$\boldsymbol{\phi }$

as a distribution rather than a point estimate, modelling their posterior as a multivariate Gaussian with a diagonal plus low-rank covariance structure:

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{\phi }_{\textit{SWA}}$

is the running average of network weights collected over stochastic gradient descent trajectories after a burn-in period. The covariance matrices are computed as

$\boldsymbol{\phi }_{\textit{SWA}}$

is the running average of network weights collected over stochastic gradient descent trajectories after a burn-in period. The covariance matrices are computed as

where

![]() $\varSigma _{\textit{low}\text{-}\textit{rank}}$

is a low-rank approximation of the covariance using the last

$\varSigma _{\textit{low}\text{-}\textit{rank}}$

is a low-rank approximation of the covariance using the last

![]() $K$

epochs, with

$K$

epochs, with

![]() $\hat {H} = [\boldsymbol{\phi }_{N-K+1} - \boldsymbol{\phi }_{\textit{SWA}}, \ldots , \boldsymbol{\phi }_N - \boldsymbol{\phi }_{\textit{SWA}}]$

.

$\hat {H} = [\boldsymbol{\phi }_{N-K+1} - \boldsymbol{\phi }_{\textit{SWA}}, \ldots , \boldsymbol{\phi }_N - \boldsymbol{\phi }_{\textit{SWA}}]$

.

During inference, the weights of the trained function

![]() $\mathcal{F}_{\boldsymbol{\phi }^*}$

are sampled from this posterior:

$\mathcal{F}_{\boldsymbol{\phi }^*}$

are sampled from this posterior:

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{z}_1$

and

$\boldsymbol{z}_1$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{z}_2$

are independently sampled from a multivariate standard normal distribution

$\boldsymbol{z}_2$

are independently sampled from a multivariate standard normal distribution

![]() $\mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{0}, \boldsymbol{I})$

. With the weight ensemble of size

$\mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{0}, \boldsymbol{I})$

. With the weight ensemble of size

![]() $m$

, the mean and epistemic uncertainty of wall quantity predictions are computed as

$m$

, the mean and epistemic uncertainty of wall quantity predictions are computed as

\begin{align} \overline {\boldsymbol{\varPhi }}_{w\textit{all}} &= \frac {1}{m}\sum _{i=1}^m \mathcal{F}_{\boldsymbol{\phi }^*_i}(\boldsymbol{u}'_i), \\[-12pt]\nonumber \end{align}

\begin{align} \overline {\boldsymbol{\varPhi }}_{w\textit{all}} &= \frac {1}{m}\sum _{i=1}^m \mathcal{F}_{\boldsymbol{\phi }^*_i}(\boldsymbol{u}'_i), \\[-12pt]\nonumber \end{align}

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{\sigma }_{\boldsymbol{\varPhi }_{w\textit{all}}} &= \sqrt {\frac {1}{m}\sum _{i=1}^m \big ( \mathcal{F}_{\boldsymbol{\phi }^*_i}(\boldsymbol{u}'_i) - \overline {\boldsymbol{\varPhi }}_{w\textit{all}}\big )^2}. \end{align}

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{\sigma }_{\boldsymbol{\varPhi }_{w\textit{all}}} &= \sqrt {\frac {1}{m}\sum _{i=1}^m \big ( \mathcal{F}_{\boldsymbol{\phi }^*_i}(\boldsymbol{u}'_i) - \overline {\boldsymbol{\varPhi }}_{w\textit{all}}\big )^2}. \end{align}

Moreover, we adopt a patchwise training strategy: the operator is trained on small spatial subdomains of size

![]() $n_x \times n_z = 32$

, much smaller than the full domain size

$n_x \times n_z = 32$

, much smaller than the full domain size

![]() $N_x \times N_z$

. This localised learning strategy is inspired by the inherently local structure of near-wall turbulence, which increases the diversity of training examples, reduces memory usage and improves generalisation to unseen realisations of the flow at the trained wall-normal locations. An analysis of the effect of dataset size on the convergence of the SWAG operator is presented in Appendix D. The results confirm that the patchwise training strategy is essential for achieving convergence when learning this operator. Importantly, due to the fully convolutional nature of the U-Net, the trained model can be applied to full-domain velocity inputs during inference, leveraging translation invariance of convolution operations.

$N_x \times N_z$

. This localised learning strategy is inspired by the inherently local structure of near-wall turbulence, which increases the diversity of training examples, reduces memory usage and improves generalisation to unseen realisations of the flow at the trained wall-normal locations. An analysis of the effect of dataset size on the convergence of the SWAG operator is presented in Appendix D. The results confirm that the patchwise training strategy is essential for achieving convergence when learning this operator. Importantly, due to the fully convolutional nature of the U-Net, the trained model can be applied to full-domain velocity inputs during inference, leveraging translation invariance of convolution operations.

In summary, our patch-trained, SWAG-based forward operator

![]() $\mathcal{F}_{\boldsymbol{\phi }}$

provides a scalable, interpretable and uncertainty-aware mechanism to connect full-field turbulence predictions to surface measurements, and is essential to enabling flexible and rigorous conditional flow reconstruction in the proposed generative framework.

$\mathcal{F}_{\boldsymbol{\phi }}$

provides a scalable, interpretable and uncertainty-aware mechanism to connect full-field turbulence predictions to surface measurements, and is essential to enabling flexible and rigorous conditional flow reconstruction in the proposed generative framework.

3. Results

In this section, we evaluate the performance of the proposed FM framework on reconstructing instantaneous velocity fluctuation fields from wall-based measurements in wall-bounded turbulent flow. The primary goal is to assess how well the model can synthesise physically realistic velocity fluctuations under varying wall measurement conditions, and to quantify the associated predictive uncertainty. The framework is tested on canonical turbulent channel flow at a friction Reynolds number of

![]() $\textit{Re}_\tau = 180$

. During training, the generative model is exposed to unconditional samples at wall-normal positions

$\textit{Re}_\tau = 180$

. During training, the generative model is exposed to unconditional samples at wall-normal positions

![]() $y^+ = {5, 20, 40}$

, without access to any measurement-based conditioning information. Conditional inference is performed entirely at test time using the training-free guidance strategy described in § 2.4, which allows flexible assimilation of wall-based measurements across different levels of sparsity and noise.

$y^+ = {5, 20, 40}$

, without access to any measurement-based conditioning information. Conditional inference is performed entirely at test time using the training-free guidance strategy described in § 2.4, which allows flexible assimilation of wall-based measurements across different levels of sparsity and noise.

3.1. The DNS case set-up, data generation and evaluation metrics

The dataset used for training and evaluation is generated via DNS of incompressible channel flow at

![]() $\textit{Re}_\tau = 180$

. The computational domain is defined as

$\textit{Re}_\tau = 180$

. The computational domain is defined as

![]() $[L_x, L_y, L_z] = [4\pi , 2, 2\pi ]$

in the streamwise (

$[L_x, L_y, L_z] = [4\pi , 2, 2\pi ]$

in the streamwise (

![]() $x$

), wall-normal (

$x$

), wall-normal (

![]() $y$

) and spanwise (

$y$

) and spanwise (

![]() $z$

) directions, respectively. The simulation employs a uniform grid resolution of

$z$

) directions, respectively. The simulation employs a uniform grid resolution of

![]() $[N_x, N_y, N_z] = [320, 400, 200]$

with periodic boundary conditions in

$[N_x, N_y, N_z] = [320, 400, 200]$

with periodic boundary conditions in

![]() $x$

and

$x$

and

![]() $z$

, and no-slip boundary conditions at the walls. The flow is driven by a constant mean pressure gradient in the streamwise direction. Snapshots of both the velocity field and wall quantities are recorded at intervals of

$z$

, and no-slip boundary conditions at the walls. The flow is driven by a constant mean pressure gradient in the streamwise direction. Snapshots of both the velocity field and wall quantities are recorded at intervals of

![]() $\Delta T^+ = 0.4$

in viscous time units.

$\Delta T^+ = 0.4$

in viscous time units.

To construct the dataset, statistical symmetry about the channel centreline is exploited by reflecting samples from the upper and lower halves of the domain, yielding a total of

![]() $43.8k$

snapshots. These snapshots span approximately 60 flow-through times. Each data sample comprises the velocity fluctuations

$43.8k$

snapshots. These snapshots span approximately 60 flow-through times. Each data sample comprises the velocity fluctuations

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}'_i = [u', v', w']$

at a given wall-normal location

$\boldsymbol{u}'_i = [u', v', w']$

at a given wall-normal location

![]() $y^+$

and the corresponding wall quantities

$y^+$

and the corresponding wall quantities

![]() $\boldsymbol{\varPhi }_{w\textit{all}} = [p, \tau _u, \tau _w]$

. The dataset is denoted as

$\boldsymbol{\varPhi }_{w\textit{all}} = [p, \tau _u, \tau _w]$

. The dataset is denoted as

![]() $\mathcal{D} = { (\boldsymbol{\varPhi }_{w\textit{all}}, \boldsymbol{u}'_i)}_{{y^+}}$

, where

$\mathcal{D} = { (\boldsymbol{\varPhi }_{w\textit{all}}, \boldsymbol{u}'_i)}_{{y^+}}$

, where

![]() $y^+$

indexes the wall-normal planes and

$y^+$

indexes the wall-normal planes and

![]() $i$

indexes the velocity fluctuation components.

$i$

indexes the velocity fluctuation components.

For training the generative FM model, we use the full

![]() $\mathcal{D}$

but only the velocity fluctuation fields

$\mathcal{D}$

but only the velocity fluctuation fields

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}'_i$

, since the training is entirely unsupervised. The forward operator

$\boldsymbol{u}'_i$

, since the training is entirely unsupervised. The forward operator

![]() $\mathcal{F}_{\boldsymbol{\phi }}$

, which maps

$\mathcal{F}_{\boldsymbol{\phi }}$

, which maps

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}'_i$

to

$\boldsymbol{u}'_i$

to

![]() $\boldsymbol{\varPhi }_{w\textit{all}}$

with uncertainty quantification, is trained using approximately

$\boldsymbol{\varPhi }_{w\textit{all}}$

with uncertainty quantification, is trained using approximately

![]() $9000$

velocity–wall data pairs randomly drawn from

$9000$

velocity–wall data pairs randomly drawn from

![]() $\mathcal{D}$

. The training of the generative model and the forward operator is carried out with full-observability conditions of the velocity fluctuation fields and wall measurements. For evaluation, an entirely separate set of

$\mathcal{D}$

. The training of the generative model and the forward operator is carried out with full-observability conditions of the velocity fluctuation fields and wall measurements. For evaluation, an entirely separate set of

![]() $500$

uncorrelated samples is generated with a larger sampling interval to ensure statistical independence from the training data. This evaluation set corresponds to approximately

$500$

uncorrelated samples is generated with a larger sampling interval to ensure statistical independence from the training data. This evaluation set corresponds to approximately

![]() $7$

flow-through times. Such strict separation allows us to benchmark generalisation performance in fully unseen flow states. Thus, the training dataset enables the generative model to accurately learn the distribution of turbulent velocity fluctuations. A completely temporally independent testing set is then used for a robust statistical evaluation of the proposed framework. This robust evaluation is necessary due to the stochastic nature of generative models; in the current work, we assess performance by computing converged turbulent statistics. Additional details about the training and testing split are provided in Appendix E. A summary of the simulation set-up and dataset statistics is provided in table 1.

$7$

flow-through times. Such strict separation allows us to benchmark generalisation performance in fully unseen flow states. Thus, the training dataset enables the generative model to accurately learn the distribution of turbulent velocity fluctuations. A completely temporally independent testing set is then used for a robust statistical evaluation of the proposed framework. This robust evaluation is necessary due to the stochastic nature of generative models; in the current work, we assess performance by computing converged turbulent statistics. Additional details about the training and testing split are provided in Appendix E. A summary of the simulation set-up and dataset statistics is provided in table 1.

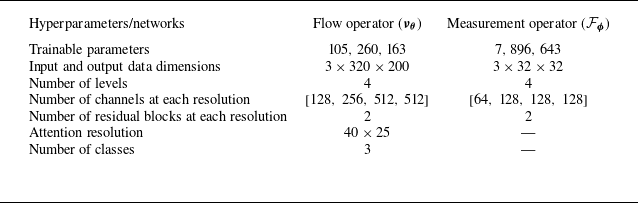

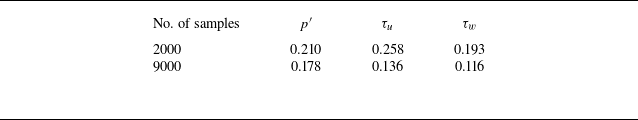

Table 1. Dataset of channel flow for training and testing the model.

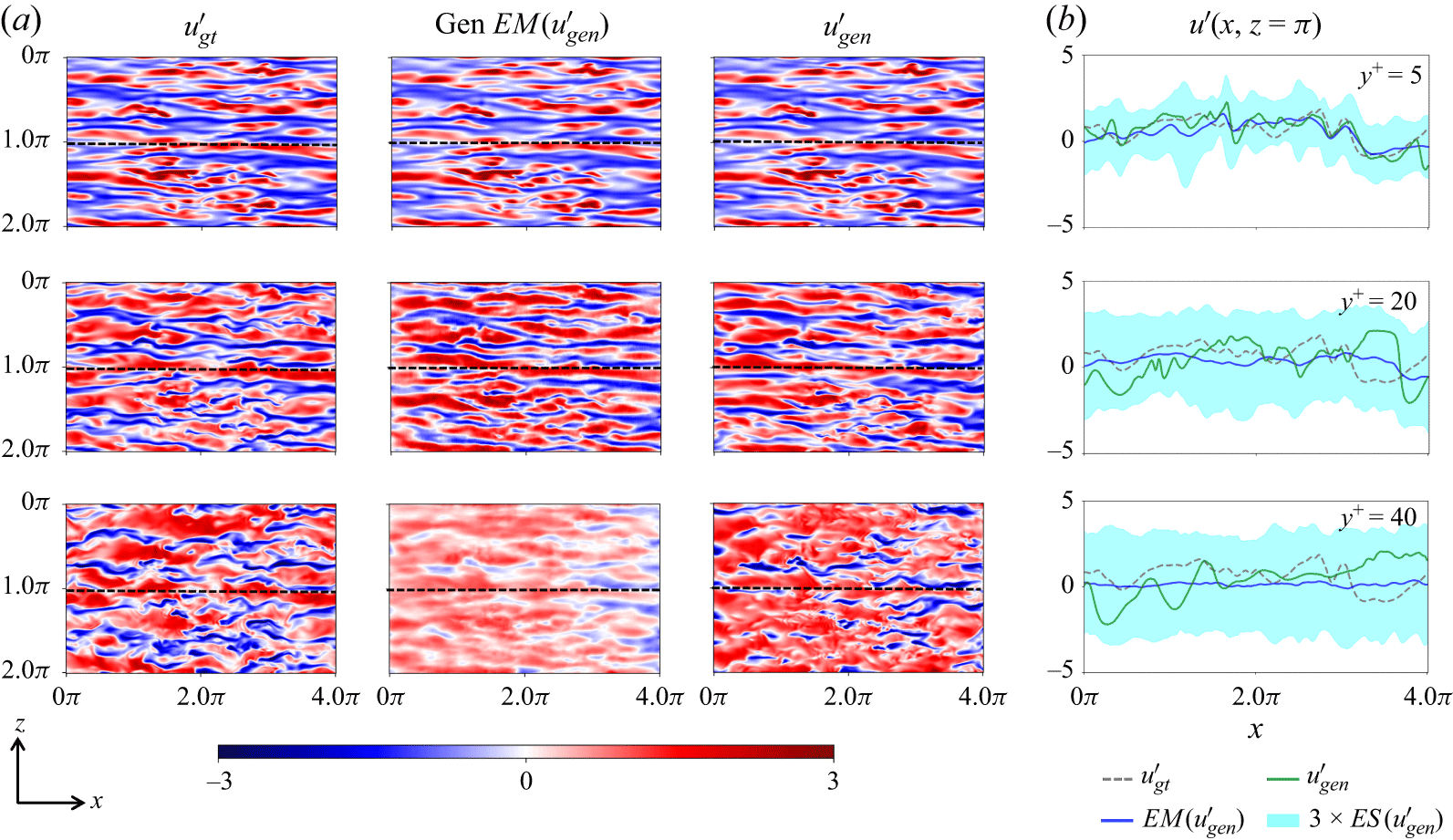

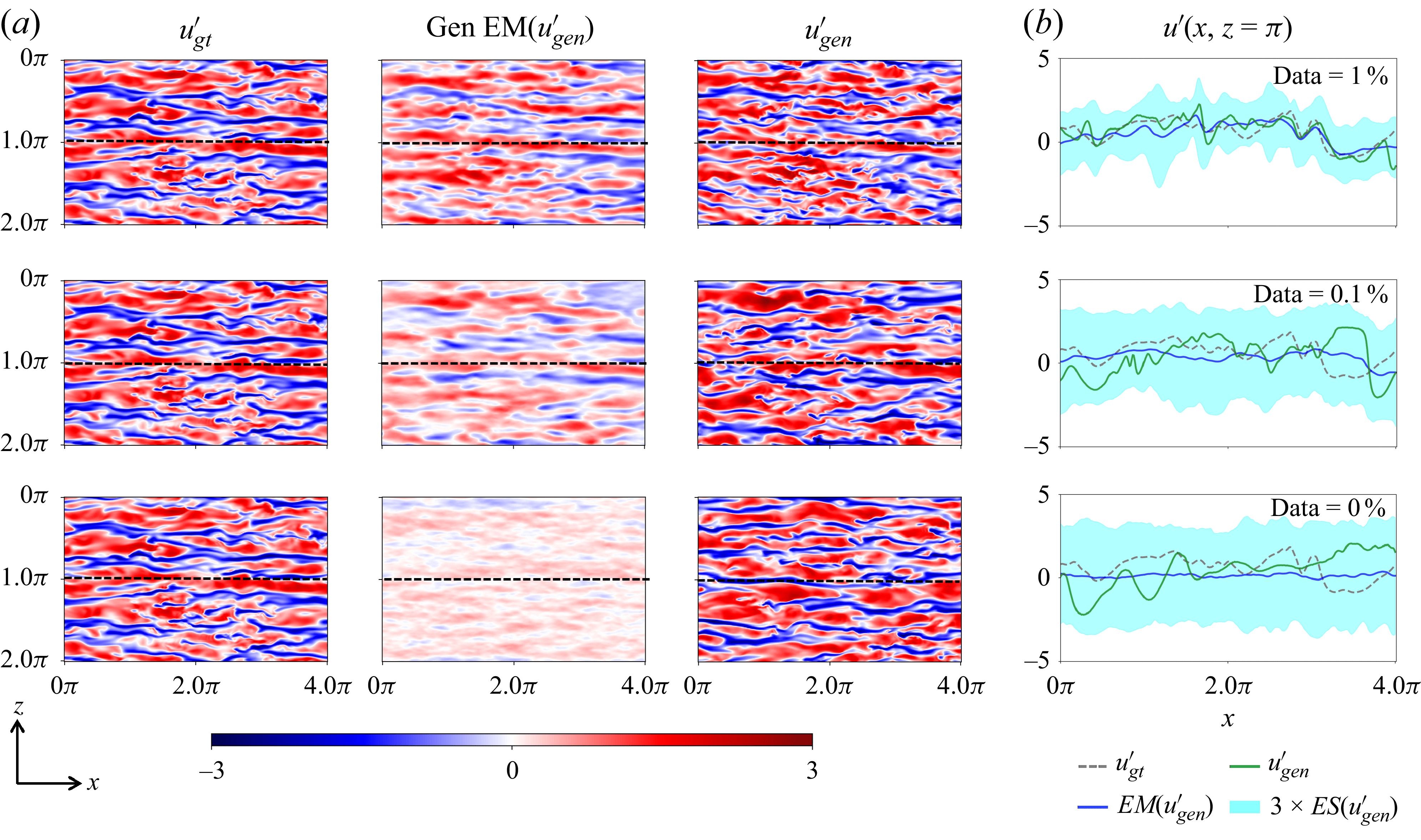

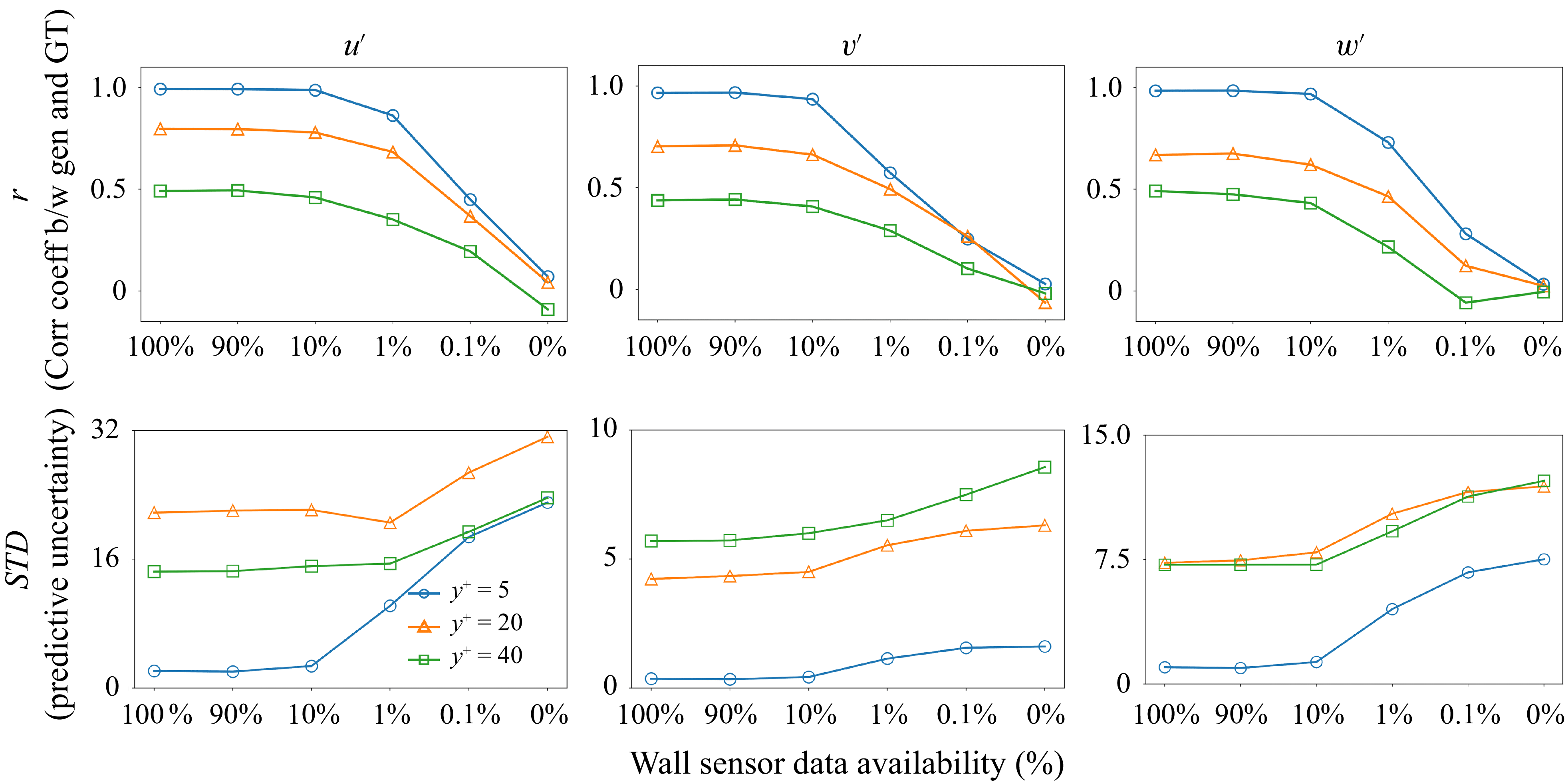

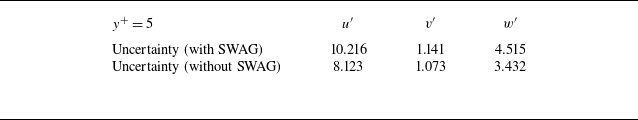

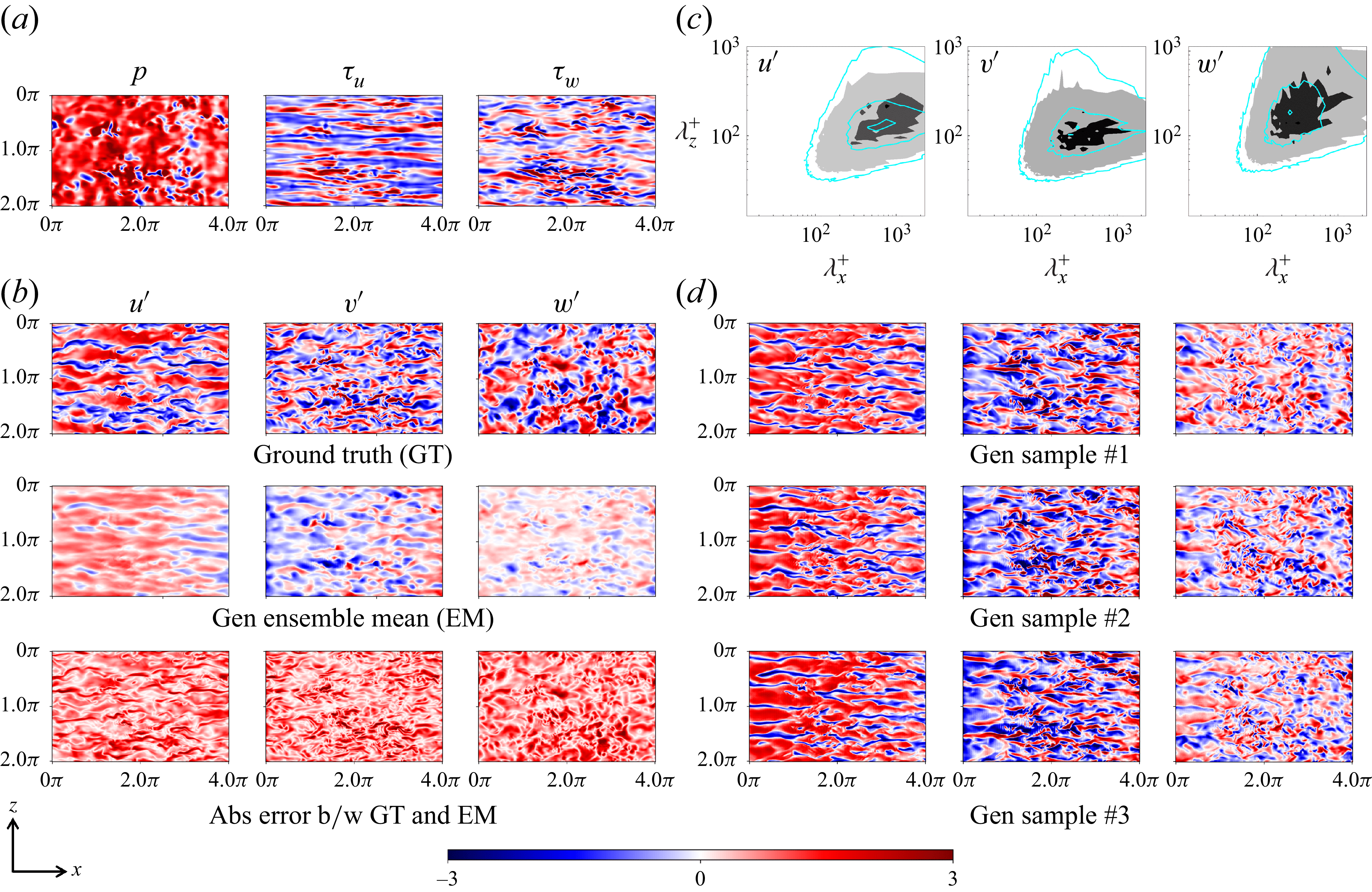

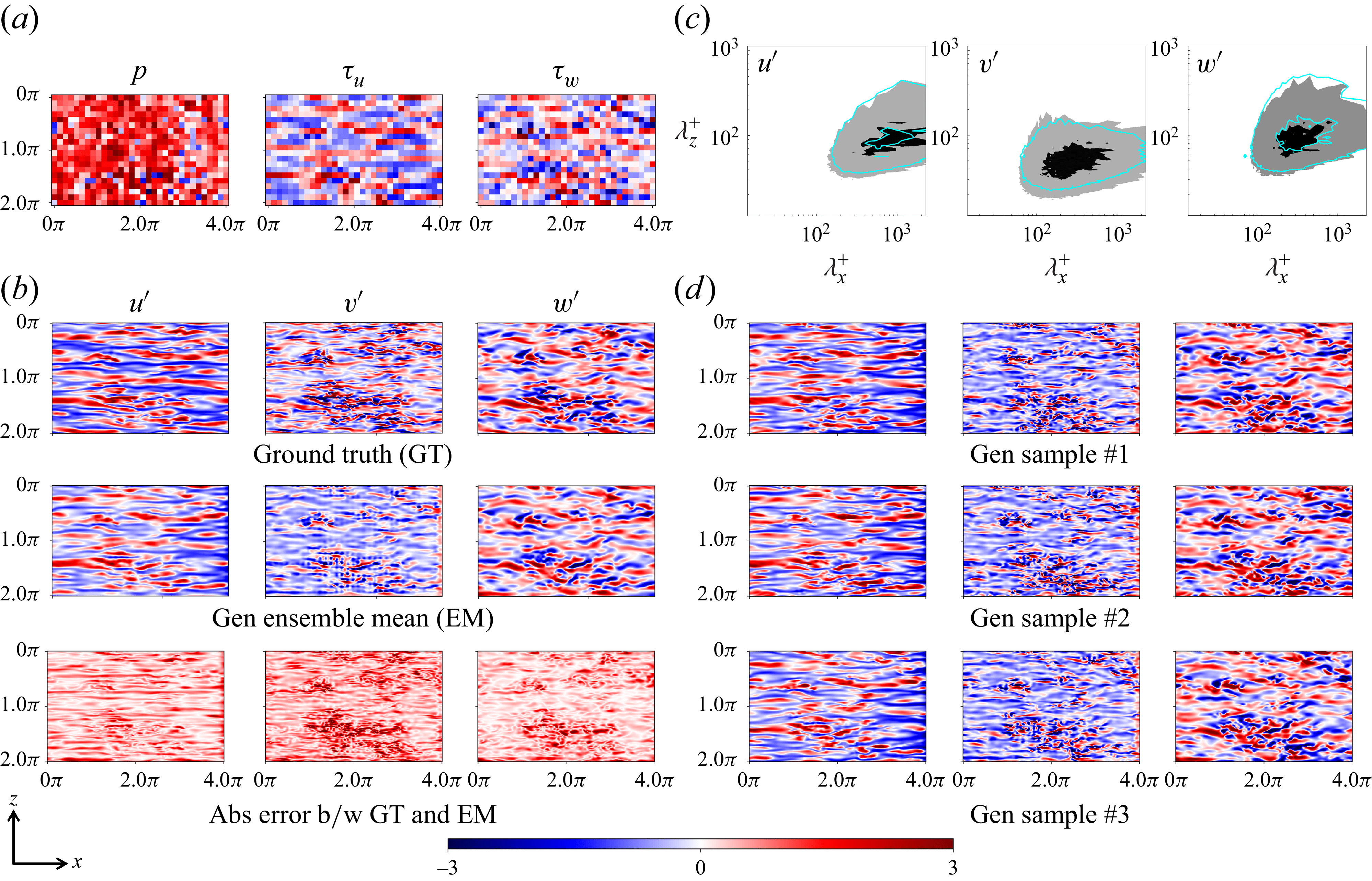

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed framework, we evaluate its conditional generation capabilities under various wall measurement scenarios, including fully observed, partially masked and spatially downsampled sensor configurations. Both qualitative and quantitative analyses are conducted to assess how well the generated velocity fluctuation fields

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}'_i = [u', v', w']$

agree with the ground-truth flow and available wall-based observations. As qualitative assessment, we begin by visualising representative conditional samples generated under different wall measurement settings, allowing us to inspect the model’s ability to synthesise flow realisations that preserve the physical structure and intermittency of near-wall turbulence while adapting to available sensor data. The velocity fluctuation fields are normalised by the root-mean-squared value at their respective wall-normal locations to enable visualisation on a unified scale. For quantitative evaluation, we compute the ensemble mean (EM) and ensemble spread (ES) across multiple conditional samples. For example, the mean and standard deviation of

$\boldsymbol{u}'_i = [u', v', w']$

agree with the ground-truth flow and available wall-based observations. As qualitative assessment, we begin by visualising representative conditional samples generated under different wall measurement settings, allowing us to inspect the model’s ability to synthesise flow realisations that preserve the physical structure and intermittency of near-wall turbulence while adapting to available sensor data. The velocity fluctuation fields are normalised by the root-mean-squared value at their respective wall-normal locations to enable visualisation on a unified scale. For quantitative evaluation, we compute the ensemble mean (EM) and ensemble spread (ES) across multiple conditional samples. For example, the mean and standard deviation of

![]() $u'$

are defined as

$u'$

are defined as

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \textit{EM}(u^{\prime}) &= \frac {1}{N_{\textit{ens}}}\sum ^{N_{\textit{ens}}}_{i=1} {u'}_{\textit{gen,i}},\\[3pt] \textit{ES}(u^{\prime}) &= \sqrt {\frac {\sum ^{N_{\textit{ens}}}_{i=1}|{u'}_{\textit{gen,i}} -\textit{EM}(u^{\prime})|^2}{N_{\textit{ens}}}}, \end{aligned} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \textit{EM}(u^{\prime}) &= \frac {1}{N_{\textit{ens}}}\sum ^{N_{\textit{ens}}}_{i=1} {u'}_{\textit{gen,i}},\\[3pt] \textit{ES}(u^{\prime}) &= \sqrt {\frac {\sum ^{N_{\textit{ens}}}_{i=1}|{u'}_{\textit{gen,i}} -\textit{EM}(u^{\prime})|^2}{N_{\textit{ens}}}}, \end{aligned} \end{equation}

where

![]() $N_{\textit{ens}}$

denotes the number of generated samples. Analogous definitions are used for

$N_{\textit{ens}}$

denotes the number of generated samples. Analogous definitions are used for

![]() $v'$

and

$v'$

and

![]() $w'$

components. We further assess the accuracy of the ensemble mean by comparing it with the ground-truth DNS field using the Pearson correlation coefficient

$w'$

components. We further assess the accuracy of the ensemble mean by comparing it with the ground-truth DNS field using the Pearson correlation coefficient

![]() $r$

. After flattening the

$r$

. After flattening the

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $z$

plane into a one-dimensional vector, the correlation for

$z$

plane into a one-dimensional vector, the correlation for

![]() $u'$

is calculated as follows:

$u'$

is calculated as follows:

\begin{equation} r = \frac {\sum _{i}^{N_x \times N_z} \big ({u'}_{gt, i} - \overline {{u'}_{gt}}\big ) \big (\textit{EM}({u'}_{i}) - \overline {\textit{EM}({u'})}\big )}{\sqrt {\sum _{i}^{N_x \times N_z} \big ({u'}_{gt, i} - \overline {{u'}_{gt}}\big )^2 \sum _{i}^{N_x \times N_z} \big (\textit{EM}({u'}_{i}) - \overline {\textit{EM}({u'})}\big )^2}}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} r = \frac {\sum _{i}^{N_x \times N_z} \big ({u'}_{gt, i} - \overline {{u'}_{gt}}\big ) \big (\textit{EM}({u'}_{i}) - \overline {\textit{EM}({u'})}\big )}{\sqrt {\sum _{i}^{N_x \times N_z} \big ({u'}_{gt, i} - \overline {{u'}_{gt}}\big )^2 \sum _{i}^{N_x \times N_z} \big (\textit{EM}({u'}_{i}) - \overline {\textit{EM}({u'})}\big )^2}}, \end{equation}

where

![]() $\overline {(\boldsymbol{\cdot })}$

denotes spatial mean over the

$\overline {(\boldsymbol{\cdot })}$

denotes spatial mean over the

![]() $x$

–

$x$

–

![]() $z$

plane. To quantify how well each generated sample matches the given wall measurements, we use the normalised pointwise

$z$

plane. To quantify how well each generated sample matches the given wall measurements, we use the normalised pointwise

![]() $L_2$

error

$L_2$

error

![]() $\varDelta _{\boldsymbol{y}}(x,z)$

as proposed in Li et al. (Reference Li, Buzzicotti, Biferale, Bonaccorso, Chen and Wan2023) and Du et al. (Reference Du, Parikh, Fan, Liu and Wang2024):

$\varDelta _{\boldsymbol{y}}(x,z)$

as proposed in Li et al. (Reference Li, Buzzicotti, Biferale, Bonaccorso, Chen and Wan2023) and Du et al. (Reference Du, Parikh, Fan, Liu and Wang2024):

where the normalisation factor

![]() $E_{\boldsymbol{y}}$

accounts for the spatial variability in both the generated and ground-truth wall measurements, and is given by

$E_{\boldsymbol{y}}$

accounts for the spatial variability in both the generated and ground-truth wall measurements, and is given by

![]() $E_{\boldsymbol{y}} = \sigma ^{\textit{gen}}_{\boldsymbol{y}} \times \sigma ^{gt}_{\boldsymbol{y}}$

, where

$E_{\boldsymbol{y}} = \sigma ^{\textit{gen}}_{\boldsymbol{y}} \times \sigma ^{gt}_{\boldsymbol{y}}$

, where

![]() $\sigma ^{\textit{gen}}_{\boldsymbol{y}}$

denotes the ensemble-averaged spatial standard deviation of the generated wall measurements:

$\sigma ^{\textit{gen}}_{\boldsymbol{y}}$

denotes the ensemble-averaged spatial standard deviation of the generated wall measurements:

and

![]() $\sigma ^{gt}_{\boldsymbol{y}}$

is defined analogously using the ground-truth measurements

$\sigma ^{gt}_{\boldsymbol{y}}$

is defined analogously using the ground-truth measurements

![]() $\boldsymbol{y}_{{gt}}$

.

$\boldsymbol{y}_{{gt}}$

.

Finally, to further assess the physical realism of the generated samples, we perform a statistical turbulence analysis on an ensemble of 500 conditional realisations. Specifically, we evaluate the pre-multiplied two-dimensional energy spectra,

![]() $E_{u_i'u_i'}$