1. Introduction

We study the effects of long-run inflation in a model with competitive search and non-degenerate money distribution. Monetary search models provide a deeper microfoundation of money, where important market frictions or behavioral outcomes are not assumed but are consequences of environmental (e.g., informational and contractual) imperfections. The framework has been applied to answer many questions such as the existence and essentiality of money, financial intermediation, asset liquidity, and equilibrium price dispersion.Footnote 1

In this paper, we follow and extend the model of Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013) to study non-zero inflation. The heterogeneity in our model is a result of equilibrium directed search and matching frictions. That is, we do not rely on exogenous shocks to individual states, and, as in Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013), possible persistence in agent heterogeneity is induced by endogenous individual spending cycles.Footnote 2 However, a question remains open in this class of competitive-search models: How does inflation affect the trade-off underlying heterogenous individuals’ matching and market participation rates, their corresponding terms of trade, and the resulting equilibrium distribution of agents’ money holdings? This question is very relevant now as most advanced economies are facing higher inflation rates in recent times.Footnote 3

In our model, individuals direct their search to sellers, and sellers post their trade terms in anticipation of different matching probabilities at different trading posts (or submarkets). These incentives and matching probabilities, in turn, depend on different levels of money holdings and inflation policy. This introduces a different channel of monetary policy that is muted in models without this endogenous mechanism. Consequently, we have equilibrium-determined distributions of market participation, market tightness, relative prices, and trade quantities.Footnote 4 Addressing our question is an important first step towards incorporating competitive search behavior into a more feature-laden and quantitative model.

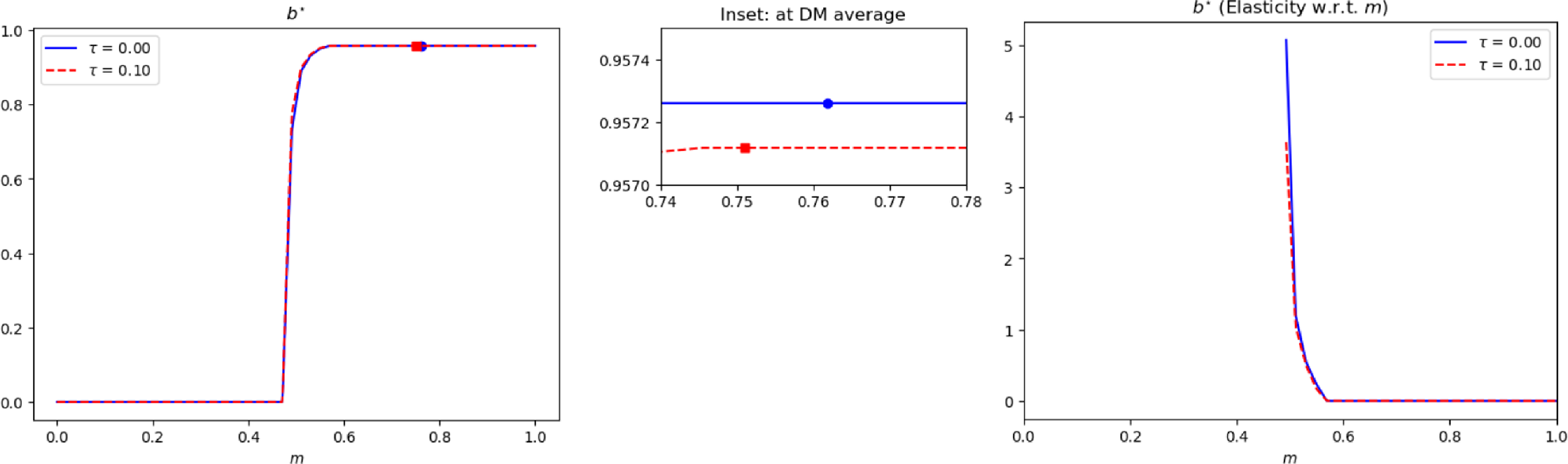

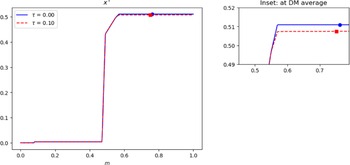

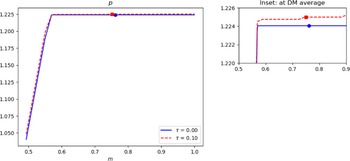

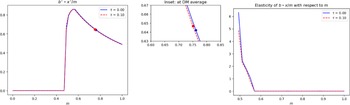

With competitive search, it is well known that individuals face a trade-off between an extensive margin of trading probability and an intensive margin of trade quantity (see, e.g., Wright et al. Reference Wright, Kircher, Julien and Guerrieri2021; Rocheteau and Wright Reference Rocheteau and Wright2005; Moen Reference Moen1997). We emphasize that with a non-degenerate distribution of money balances in equilibrium, the effects of inflation on these trade-offs in our model depend on agents’ money holdings. We provide a numerical comparative study of steady-state equilibria across two inflation regimes to illustrate the results (see Section 4).Footnote 5 In particular, we show that with higher long run inflation, while matching probabilities fall with inflation for all agents, agents with relatively lower money balances (“the poor”) face a steeper decline in payments and matching probabilities than those with higher money holdings (“the rich”).Footnote 6 This translates to an increase in dispersion of total payments and trading probabilities as inflation becomes higher.Footnote 7

The difference in the steepness (with respect to higher inflation regimes) of the decline in matching probabilities and payment amounts between the “rich” and “poor” reflects the underlying tension between the intensive and extensive margin in the competitive search markets. This tension or trade-off varies depending on the agent’s money holding. Our equilibrium comparisons show that the “rich,” relative to the “poor” will also have a higher velocity of spending (i.e., a higher ratio of expected payments per dollar carried) due to the flatter decline in matching rates and payments. This enables the “rich” to replenish their liquidity faster to support better matching and trade outcomes in goods search markets as inflation rises, compared to the “poor.”

Higher inflation has two effects on agents’ money holdings. On one hand, higher inflation tends to compress dispersion in money holding. That comes from the intensive margin effect. This is typically known as the redistributive effect of the inflation tax and is a common feature in all heterogeneous-agent monetary models (see, for example, Erosa and Ventura Reference Erosa and Ventura2002). On the other hand, with higher inflation, the extensive margin aspect of competitive search gives us a rising dispersion in heterogeneous matching opportunities, spending amounts, and speeds of transactions. These gaps between the “rich” and “poor” widen with inflation and deliver an opposing force against the standard redistributive effect of inflation tax. When inflation is low, the intensive margin effect dominates, while the extensive margin effect becomes stronger at sufficiently high inflation rates. This leads to a novel non-monotonic relationship between inflation and money-holding inequality: For low long-run inflation rates, the inequality in money holdings tends to diminish with inflation. However, for sufficiently high inflation rates, the inequality in money holdings increases with inflation.Footnote 8

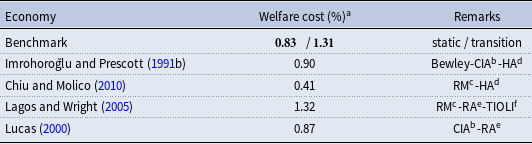

As a consequence of this friction working against the compressing or redistributive effect of inflation, the welfare cost of inflation is nontrivial, especially when transitional dynamics are taken into account. In standard models, due to its redistributive property, the welfare cost of inflation is lowered relative to a representative-agent monetary model. With competitive search, this effect can be dominated by the effects of inflation on the extensive margin of trade. As a result, we find that the welfare cost of inflation can be as high as, or even higher than, the original representative-agent calculation of Lucas Reference Lucas2000.Footnote 9

Finally, we also develop a novel way of solving the equilibrium computationally. There is a technical challenge posed by the theoretical work of Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013): The agents’ ex-ante value function (labeled as

![]() $B$

later) induced by pure strategies with competitive search is typically non-concave/convex over multiple parts of its domain (money holdings). Thus, agents can be better off by choosing lotteries that convexify the graph of

$B$

later) induced by pure strategies with competitive search is typically non-concave/convex over multiple parts of its domain (money holdings). Thus, agents can be better off by choosing lotteries that convexify the graph of

![]() $B$

. We propose a practical, efficient, and high-precision implementation of this idea using standard convex hull computational tools.Footnote

10

We explain this idea further in Section 3.1 and in more detail in Online Appendix E.

$B$

. We propose a practical, efficient, and high-precision implementation of this idea using standard convex hull computational tools.Footnote

10

We explain this idea further in Section 3.1 and in more detail in Online Appendix E.

1.1. Related literature

Our paper uses a competitive search framework to study the effects of inflation. There is a vast literature analyzing the effects of inflation. We briefly review some of them here while paying more attention to papers more closely related to our approach. We then discuss a few papers which also feature non-degenerate distributions of money holdings and emphasize the difference between our model and theirs. Finally, we describe the essence of Menzio et al. Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013, and discuss why it poses an open problem for us to study here in terms of inflation and its distribution and welfare effects.Footnote 11

1.1.1. Inflation, heterogeneity and money distribution

Consider a taxonomy of the costs and benefits of inflation in standard Walrasian-market models (see, e.g., Erosa and Ventura Reference Erosa and Ventura2002). First, inflation acts as an intertemporal tax that distorts consumption. This feature raises the (welfare) cost of inflation in all monetary models (with or without heterogeneous agents). Second, inflation is costly since agents have to engage in precautionary liquidity management activities. Third, inflation may act as a redistributive tax that shifts resources from the “rich” to the “poor.” This force tends to lower the welfare cost of inflation.

In most heterogeneous-agent models (see, e.g., Imrohoroğlu and Prescott Reference Imrohoroğlu and Prescott1991a; Akyol Reference Akyol2004; Boel and Camera Reference Boel and Camera2009; Meh et al. Reference Meh, Ríos-Rull and Terajima2010), the redistributive-tax channel of inflation is strong. This is often because there is only an intensive margin through which inflation tax works.Footnote 12 That is, with higher inflation, agents would like to reduce their money holdings. Those with high money balances reduce their holdings more relative to those at the bottom end of the distribution. This tends to lower the average money balance. Hence, inflation acts as a progressive tax that reduces inequality of money holdings. This explains why in many heterogeneous-agent models, the welfare cost of inflation is often smaller than representative-agent models (Camera and Chien Reference Camera and Chien2014).Footnote 13

In a random-matching, search-theoretic model of money, Molico (Reference Molico2006) shows that as inflation increases agents choose to pay more money in decentralized trades and a higher amount of money is paid per unit of the good.Footnote 14 This “real balance effect” can work against the redistributive effect of inflation. There is a similar effect in our model, but with a different underlying twist. In our setting with competitive search in decentralized trades, this is bolstered by the additional extensive margin effect: Higher inflation exacts a greater downside risk of not matching for agents by reducing the equilibrium matching probability for buyers. Although expected money carried in each decentralized trade will be lower per payment for goods, with lower equilibrium probability of matching, agents who get matched don’t have to reduce consumption as much. This trade-off between matching probability and quantity of goods in the competitive search environment (see, e.g., Peters Reference Peters1984, Reference Peters1991; Moen Reference Moen1997; Burdett et al. Reference Burdett, Shi and Wright2001; Julien et al. Reference Julien, Kennes and King2008; Shi Reference Shi and Shi2008) amplifies the speed at which agents expect to deplete their money in decentralized trades.

Chiu and Molico (Reference Chiu and Molico2010) also have a notion of extensive margin, in the form of costly participation in centralized markets. In our setting, even without costly participation in markets, there is a non-trivial extensive margin. In Chiu and Molico (Reference Chiu and Molico2010) and Rocheteau et al. (Reference Rocheteau, Weill and Wong2021), trading probabilities are fixed in decentralized-market meetings. This is due to their random matching assumption. In our setting, the extensive margin arises in the form of endogenous matching probabilities.

Jin and Zhu (Reference Jin and Zhu2022) also consider the effect of long-run inflation in a random-matching model (Trejos and Wright Reference Trejos and Wright1995; Shi Reference Shi1995). In their setting, agents can only hold indivisible amounts of money. Furthermore, the inflation policy in their framework is indirectly determined through an abstract fiscal tax-and-transfer scheme that is conditioned on individual wealth. In our setting, we take the anonymity of agents literally and do not presume that government policy has such superior informational advantage. Moreover, our setting is closer to the latest generation of monetary search models where goods and assets are divisible. This allows the models to be more amenable to empirical calibration and quantitative work.

1.1.2. Money and competitive search

In contrast to the Walrasian or random matching models discussed above, our Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013) competitive search setup advances another channel to the standard taxonomy previously outlined.Footnote 15 The essence of their model is as follows: Suppose all agents begin in the economy as identical individuals. In one period, each agent has to make a decision whether to enter a centralized market (CM) to work and re-balance their money holdings, or to direct their search in a decentralized market (DM). In the search problem agents direct themselves to different trading posts with different terms of trade and matching probabilities. Firms anticipate that and create these trading posts accordingly. In equilibrium, there is an asymptotic distribution of heterogenous money holdings that must be consistent with the agents’ different responses in trading probabilities, payments and market participation rates. Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013) characterize such an equilibrium in the special case of zero long-run inflation.

Our paper complements Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013). We study how inflation drives agents’ competitive search trade-offs, their endogenous market participations, and how this ties in with distributional outcomes. In our model, the responsiveness of agents in terms of their trading probabilities and quantities is endogenous. We show that because of the Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013) heterogeneity in matching rates, there is an opposing extensive margin effect that helps to mitigate the previously-discussed redistributive channel of inflation.Footnote 16 With higher inflation, agents are also spending faster in decentralized trades and entering the centralized market to rebalance their liquidity more frequently. Higher centralized-market participation implies that there are more agents with less money holding at the end of each period. These agents will enter the centralized market in the subsequent period. Also, there will be a smaller measure of agents at the upper end of the distribution since they top up with less liquidity in the centralized market and spend faster in the decentralized search market.

Endogenous matching probabilities via competitive search is not new (see, e.g., Rocheteau and Wright Reference Rocheteau, Wright, Rocheteau and Wright2009, Reference Rocheteau and Wright2005; Lagos and Rocheteau Reference Lagos and Rocheteau2005). What is different here is that the endogenous matching probabilities are heterogeneous in agent states and its distribution depends on inflation. This creates a nontrivial equilibrium, countervailing effect to what would be a traditional redistributive role of inflation. This is an important feature driving our non-monotone inequality results.Footnote 17 In addition to the introduction and study of inflation, we differ slightly from Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013) by including quasi-linear utility of consumption and labor in the CM. This is done to enable a more flexible way to calibrate the model to data. It does not qualitatively alter the mechanism in Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013).

Sun and Zhou (Reference Sun and Zhou2018) also embed the competitive search market of Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013) to study fiscal and monetary policy. However, there is a crucial difference between their model and Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013), and thus our study of inflation here. They assumed away the endogenous duration of an agent’s participation of the DM in the original Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013) paper. Agents in their model can only stay for one period in the DM and must return to the CM (featuring quasilinear preferences) afterwards. Their model would be a version of the competitive search equilibrium in Rocheteau and Wright (Reference Rocheteau and Wright2005) where there is a degenerate distribution of money and prices, if not for an assumption that agents in the CM draw an (i.i.d.) idiosyncratic income shock.Footnote 18 As a consequence, a one-shot and non-persistent dispersion in matching probabilities in Sun and Zhou (Reference Sun and Zhou2018) is entirely buttressed by an assumption of exogenous heterogeneity in individual labor-supply productivities. In contrast, we follow Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013) where ex-post heterogeneity arises in conjunction with equilibrium competitive-search dispersion in trading posts. This allows us to connect inflation policy to what we call the extensive margin underlying the distributional outcome, through agents’ heterogeneous market participation and duration of such participation, and their transactions’ speed.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we set up and analyze a version of the model of Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013) in a more general setting with non-zero inflation. In Section 3, we discuss our contribution in terms of a novel computational solution approach and also our calibration of the model. In Section 4, we conduct the main study on how inflation affects the equilibrium trade-offs that drive the model’s distributional and welfare outcomes. We do so by comparing monetary equilibria under alternative long-run inflation policies. In section 5, we compute the welfare cost of inflation implied by this model. We conclude with Section 6.

2. The model

The model builds on Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013). Time is discrete and indexed by

![]() $t\in \mathbb{N}$

. Hereinafter, we will denote

$t\in \mathbb{N}$

. Hereinafter, we will denote

![]() $X\,:\!=\,X_{t}$

and

$X\,:\!=\,X_{t}$

and

![]() $X_{+1}\,:\!=\,X_{t+1}$

for dynamic variables. There is one general good denoted by

$X_{+1}\,:\!=\,X_{t+1}$

for dynamic variables. There is one general good denoted by

![]() $C$

. There are also

$C$

. There are also

![]() $I$

types of specific goods indexed by

$I$

types of specific goods indexed by

![]() $i\in {1,2,\ldots \ldots, I}$

, where

$i\in {1,2,\ldots \ldots, I}$

, where

![]() $I\geqslant 3.$

Agents in the economy consist of

$I\geqslant 3.$

Agents in the economy consist of

![]() $I$

types individuals,

$I$

types individuals,

![]() $I$

types of firms, and a government that implements a (long-run) inflation target through controlling money-supply growth. There are measure one of each type

$I$

types of firms, and a government that implements a (long-run) inflation target through controlling money-supply growth. There are measure one of each type

![]() $i$

individuals,

$i$

individuals,

![]() $i\in I$

. An individual

$i\in I$

. An individual

![]() $i$

consumes the general good

$i$

consumes the general good

![]() $C$

, the specific good

$C$

, the specific good

![]() $i$

and produces good

$i$

and produces good

![]() $i+1$

(mod-

$i+1$

(mod-

![]() $\left |I\right |$

) as well as the general good

$\left |I\right |$

) as well as the general good

![]() $C$

. For firms, each type

$C$

. For firms, each type

![]() $i$

firm,

$i$

firm,

![]() $i\in I,$

consists of a large number of firms. A type

$i\in I,$

consists of a large number of firms. A type

![]() $i$

firm produces type

$i$

firm produces type

![]() $i$

good as well as the general good

$i$

good as well as the general good

![]() $C.$

As in Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013), firms are owned by the individuals through a balanced mutual fund.

$C.$

As in Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013), firms are owned by the individuals through a balanced mutual fund.

There is a centralized market (CM) and a decentralized market (DM). The CM is a competitive Walrasian market where the individuals supply labor

![]() $l$

, and, consume the general good

$l$

, and, consume the general good

![]() $C$

. As a result, they also manage their liquidity holding

$C$

. As a result, they also manage their liquidity holding

![]() $y$

to be carried into the following period. In the DM where the specific

$y$

to be carried into the following period. In the DM where the specific

![]() $i$

goods are traded, we have a setting similar to Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013). There is an information friction: Buyers of special DM goods are anonymous and cannot trade using private claims or contracts with selling firms. As a result, the only medium of exchange is money. For each type-

$i$

goods are traded, we have a setting similar to Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013). There is an information friction: Buyers of special DM goods are anonymous and cannot trade using private claims or contracts with selling firms. As a result, the only medium of exchange is money. For each type-

![]() $i$

good, there is a continuum of submarkets indexed by the terms of trade

$i$

good, there is a continuum of submarkets indexed by the terms of trade

![]() $(x,q)\in \mathbb{R}_{+}^{2}$

, where

$(x,q)\in \mathbb{R}_{+}^{2}$

, where

![]() $x$

is a real payment by a buyer and

$x$

is a real payment by a buyer and

![]() $q$

is the quantity traded in exchange. Hereinafter, the explicit dependency on the type of good

$q$

is the quantity traded in exchange. Hereinafter, the explicit dependency on the type of good

![]() $i\in I$

will become unnecessary.Footnote

19

Each

$i\in I$

will become unnecessary.Footnote

19

Each

![]() $i$

-type firm commits to posted terms of trade in all submarkets it chooses to enter. Buyers of good

$i$

-type firm commits to posted terms of trade in all submarkets it chooses to enter. Buyers of good

![]() $i$

direct their search toward these submarkets that sell good

$i$

direct their search toward these submarkets that sell good

![]() $i$

, by choosing the best terms of trade offered. However, as we will see, these buyers will have to balance their decision on terms of trades against the probability of getting matched. Since firms and buyers choose which submarket to participate in, a type

$i$

, by choosing the best terms of trade offered. However, as we will see, these buyers will have to balance their decision on terms of trades against the probability of getting matched. Since firms and buyers choose which submarket to participate in, a type

![]() $i$

buyer will only participate in the submarkets where type

$i$

buyer will only participate in the submarkets where type

![]() $i$

firms sell.

$i$

firms sell.

At any date, each individual decides which market—CM or DM—to participate in. An individual can only be in the CM or DM at a given time period. Firms operate in both CM and DM at the same time. Individuals demand money as a precaution against the need for liquidity in anonymous markets in the DM. A firm in the CM hires labor to produce the general CM good and the special DM goods. A type

![]() $i$

firm hires labor service from type

$i$

firm hires labor service from type

![]() $i-1$

(mod-

$i-1$

(mod-

![]() $\left |I\right |$

) individuals (in the CM spot labor market) and transforms it (linearly) into the same amount of DM good

$\left |I\right |$

) individuals (in the CM spot labor market) and transforms it (linearly) into the same amount of DM good

![]() $i$

.

$i$

.

Two features of the model give rise to market incompleteness: First, equilibrium matching in the DM (where money is essential) implies that agents face ex-ante uncertainty over being able to exchange and consume in those markets. Second, in the equilibria that emerge, there is endogenous limited participation in centralized markets. Since agents are anonymous in the DM, their individual risks are uninsurable: private state-contingent securities are not incentive feasible. Anonymity renders equilibrium value for money as a medium of exchange. Competitive search and matching with options to participate in the CM yields equilibrium-determined ex-post agent heterogeneity.

Figure 1. Timing, markets, outcomes.

Figure 1 summarizes the timing of events and decisions between two arbitrary dates. Next, we detail the model primitives and decision problems.

2.1. Individuals, matching and firms

2.1.1. Preference representation

The per-period utility function of an individual is

where

![]() $U(C)$

is the utility of consuming the general good

$U(C)$

is the utility of consuming the general good

![]() $C$

,

$C$

,

![]() $h(l)$

is the disutility from supplying labor in the CM, and

$h(l)$

is the disutility from supplying labor in the CM, and

![]() $u(q)$

is the utility of consuming the specific good in the DM. We assume that the functions

$u(q)$

is the utility of consuming the specific good in the DM. We assume that the functions

![]() $U$

and

$U$

and

![]() $u$

are continuously differentiable, strictly increasing, strictly concave,

$u$

are continuously differentiable, strictly increasing, strictly concave,

![]() $U_{1},u_{1}\gt 0$

,

$U_{1},u_{1}\gt 0$

,

![]() $U_{11},u_{11}\lt 0$

, and the following boundary conditions hold:

$U_{11},u_{11}\lt 0$

, and the following boundary conditions hold:

![]() $u(0)=U_{1}(\infty )=u_{1}(\infty )=0$

, and

$u(0)=U_{1}(\infty )=u_{1}(\infty )=0$

, and

![]() $u_{1}(0)\lt \infty$

.Footnote

20

Also, we assume that

$u_{1}(0)\lt \infty$

.Footnote

20

Also, we assume that

![]() $h\left (l\right )=l$

. This simplifies the algebraic description of the CM decision problem and ensures that agents exiting the CM are identical.

$h\left (l\right )=l$

. This simplifies the algebraic description of the CM decision problem and ensures that agents exiting the CM are identical.

2.1.2. Matching technology in the DM

Let

![]() $\theta \in \mathbb{R}_{+}$

denote the ratio of trading posts to buyers in a submarket—i.e., its market tightness. In a submarket with tightness

$\theta \in \mathbb{R}_{+}$

denote the ratio of trading posts to buyers in a submarket—i.e., its market tightness. In a submarket with tightness

![]() $\theta$

, the probability that a buyer is matched with a trading post is

$\theta$

, the probability that a buyer is matched with a trading post is

![]() $b=\lambda (\theta )$

. The probability a trading post is matched with a buyer is

$b=\lambda (\theta )$

. The probability a trading post is matched with a buyer is

![]() $s={{\rho }({\theta }) \,:\!=\,}\lambda (\theta )/\theta$

. We assume that the function

$s={{\rho }({\theta }) \,:\!=\,}\lambda (\theta )/\theta$

. We assume that the function

![]() $\lambda :\mathbb{R}_{+}\rightarrow [0,1]$

is strictly increasing, with

$\lambda :\mathbb{R}_{+}\rightarrow [0,1]$

is strictly increasing, with

![]() $\lambda (0)=0$

, and

$\lambda (0)=0$

, and

![]() $\lambda (\infty )=1.$

The function

$\lambda (\infty )=1.$

The function

![]() $\rho (\theta )$

is strictly decreasing, with

$\rho (\theta )$

is strictly decreasing, with

![]() $\rho (0)=1$

, and

$\rho (0)=1$

, and

![]() $\rho (\infty )=0.$

We can re-write a trading post’s matching probability

$\rho (\infty )=0.$

We can re-write a trading post’s matching probability

![]() $s=\rho (\theta )=\rho \circ \lambda ^{-1}(b)\equiv \mu (b)$

. Observe that the matching function

$s=\rho (\theta )=\rho \circ \lambda ^{-1}(b)\equiv \mu (b)$

. Observe that the matching function

![]() $\mu$

is a decreasing function, and that

$\mu$

is a decreasing function, and that

![]() $\mu (0)=1$

and

$\mu (0)=1$

and

![]() $\mu (1)=0$

. Assume that

$\mu (1)=0$

. Assume that

![]() $1/\mu (b)$

is strictly convex in

$1/\mu (b)$

is strictly convex in

![]() $b$

.

$b$

.

2.1.3. Firms

Consider a firm of type

![]() $i\in I$

that takes the CM good’s relative price

$i\in I$

that takes the CM good’s relative price

![]() $p$

(in units of labor) as given. Following Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013), we define labor as the numéraire good. The firm hires labor on the spot market to produce the CM good and the DM good. One unit of labor is transformed into one unit of CM good linearly. In the DM, a firm takes the market tightness function

$p$

(in units of labor) as given. Following Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013), we define labor as the numéraire good. The firm hires labor on the spot market to produce the CM good and the DM good. One unit of labor is transformed into one unit of CM good linearly. In the DM, a firm takes the market tightness function

![]() $\theta$

as given, and chooses the measure of trading posts (viz., shops)

$\theta$

as given, and chooses the measure of trading posts (viz., shops)

![]() $\text{d}N(x,q)$

to open in each submarket.Footnote

21

If

$\text{d}N(x,q)$

to open in each submarket.Footnote

21

If

![]() $x$

is what a matched buyer is willing to pay for

$x$

is what a matched buyer is willing to pay for

![]() $q$

and

$q$

and

![]() $s(x,q)\,:\!=\,\rho \left (\theta \left (x,q\right )\right )$

, then

$s(x,q)\,:\!=\,\rho \left (\theta \left (x,q\right )\right )$

, then

![]() $x\cdot s(x,q)$

is the firm’s expected revenue in submarket

$x\cdot s(x,q)$

is the firm’s expected revenue in submarket

![]() $(x,q)$

. To produce

$(x,q)$

. To produce

![]() $q$

the firm must hire

$q$

the firm must hire

![]() $c(q)$

units of labor. Hence

$c(q)$

units of labor. Hence

![]() $s(x,q)c(q)$

is its expected labor wage bill in submarket

$s(x,q)c(q)$

is its expected labor wage bill in submarket

![]() $(x,q)$

. We assume that

$(x,q)$

. We assume that

![]() $q\mapsto c(q)$

is a continuous convex function. The firm also pays a per-period fixed cost

$q\mapsto c(q)$

is a continuous convex function. The firm also pays a per-period fixed cost

![]() $k$

of creating the trading post in submarket

$k$

of creating the trading post in submarket

![]() $(x,q)$

.

$(x,q)$

.

The firm’s profit is:

where

![]() $N$

is a positive measure on the Borel

$N$

is a positive measure on the Borel

![]() $\sigma$

-algebra

$\sigma$

-algebra

![]() $\mathcal{B}\left (\mathbb{R}_{+}^{2}\right )$

. The first term on the RHS is the firm’s value from operating in the CM. The second is its DM total expected value across all submarkets it chooses to operate in.

$\mathcal{B}\left (\mathbb{R}_{+}^{2}\right )$

. The first term on the RHS is the firm’s value from operating in the CM. The second is its DM total expected value across all submarkets it chooses to operate in.

Note that the firms’ problem above (and also agents’ decision problems to be discussed below) do not explicitly depend on the aggregate distribution of agents. This is because of the nature of competitive search in the DM: Firms and buyers take matching probabilities as given when making their respective price posting and directed search decisions. The observed terms of trade posts and matching probabilities suffice to condition their decision processes. Moreover, CM preferences are quasilinear such that agents are identical at the end of the CM. We discuss this further in Section 2.4.1.

2.2. Money supply

At the start of each date

![]() $t$

, the total stock of money in the economy

$t$

, the total stock of money in the economy

![]() $M$

is known. We assume that

$M$

is known. We assume that

![]() $M$

grows at a constant rate

$M$

grows at a constant rate

![]() $\tau$

:

$\tau$

:

We assume

![]() $\tau \gt \beta -1$

, where

$\tau \gt \beta -1$

, where

![]() $\beta$

is the discount factor. New money stock

$\beta$

is the discount factor. New money stock

![]() $\tau M$

is injected lump sum to all agents at the end of date

$\tau M$

is injected lump sum to all agents at the end of date

![]() $t$

.

$t$

.

Since we define labor as the numéraire good, if we denote

![]() $\omega M$

as the current nominal wage rate, where

$\omega M$

as the current nominal wage rate, where

![]() $\omega$

is normalized nominal wage (i.e., nominal wage rate per units of

$\omega$

is normalized nominal wage (i.e., nominal wage rate per units of

![]() $M$

), then a dollar’s worth of money is equivalent to

$M$

), then a dollar’s worth of money is equivalent to

![]() $1/\omega M$

units of labor. The variable

$1/\omega M$

units of labor. The variable

![]() $\omega$

will be endogenously determined in a monetary equilibrium.Footnote

22

If

$\omega$

will be endogenously determined in a monetary equilibrium.Footnote

22

If

![]() $M$

is the beginning-of-period aggregate stock of money in circulation, then

$M$

is the beginning-of-period aggregate stock of money in circulation, then

![]() $1/\omega =M\times 1/\omega M$

is the beginning-of-period real aggregate (per-capita) stock of money, measured in units of labor.

$1/\omega =M\times 1/\omega M$

is the beginning-of-period real aggregate (per-capita) stock of money, measured in units of labor.

Denote (equilibrium) nominal wage growth as

![]() $\gamma (\tau )\equiv \omega _{+1}M_{+1}/(\omega M)$

. Later, for a stationary monetary equilibrium, we will require that equilibrium nominal wage grows at the same rate as money supply, i.e.,

$\gamma (\tau )\equiv \omega _{+1}M_{+1}/(\omega M)$

. Later, for a stationary monetary equilibrium, we will require that equilibrium nominal wage grows at the same rate as money supply, i.e.,

![]() $\gamma (\tau )\vert _{\left (\omega _{+1}=\omega \right )}=M_{+1}/M$

.

$\gamma (\tau )\vert _{\left (\omega _{+1}=\omega \right )}=M_{+1}/M$

.

2.3. Individuals’ decisions

An individual is identified by her current money balance,

![]() $m$

(measured in units of labor). Given policy

$m$

(measured in units of labor). Given policy

![]() $\tau$

, her decisions also depend on the aggregate wage

$\tau$

, her decisions also depend on the aggregate wage

![]() $\omega$

. Denote the relevant state vector as

$\omega$

. Denote the relevant state vector as

![]() $\textbf{s}\,:\!=\,(m,\omega )$

.Footnote

23

At the beginning of a period (ex ante), an individual decides either to work and consume in the CM or to be a buyer in the frictional DM.Footnote

24

Next, we describe the decision problems of agents who are ex-post CM or DM buyers. We then describe an agent’s ex-ante decision problem of choosing which of CM or DM to go to.

$\textbf{s}\,:\!=\,(m,\omega )$

.Footnote

23

At the beginning of a period (ex ante), an individual decides either to work and consume in the CM or to be a buyer in the frictional DM.Footnote

24

Next, we describe the decision problems of agents who are ex-post CM or DM buyers. We then describe an agent’s ex-ante decision problem of choosing which of CM or DM to go to.

2.3.1. Ex-post CM buyers

Suppose now we have an individual

![]() $\textbf{s}\,:\!=\,(m,\omega )$

who begins the current period in the CM. The individual takes policy,

$\textbf{s}\,:\!=\,(m,\omega )$

who begins the current period in the CM. The individual takes policy,

![]() $\tau$

, and the sequence of aggregate prices,

$\tau$

, and the sequence of aggregate prices,

![]() $\left (\omega, \omega _{+1},\ldots \right )$

, as given. Her value from optimally consuming

$\left (\omega, \omega _{+1},\ldots \right )$

, as given. Her value from optimally consuming

![]() $C$

, supplying labor

$C$

, supplying labor

![]() $l$

, and accumulating end-of-period money balance

$l$

, and accumulating end-of-period money balance

![]() $y$

, is

$y$

, is

where

![]() $\bar {V}:S\rightarrow \mathbb{R}$

is her continuation value function (see Section 2.3.3 on the following page). This continuation value function yields her next-period expected total payoff from state

$\bar {V}:S\rightarrow \mathbb{R}$

is her continuation value function (see Section 2.3.3 on the following page). This continuation value function yields her next-period expected total payoff from state

![]() $m_{+1}$

. The continuation state for the individual,

$m_{+1}$

. The continuation state for the individual,

![]() $m_{+1}$

, is derived as follows: At the end of the CM, the individual would have accumulated balance

$m_{+1}$

, is derived as follows: At the end of the CM, the individual would have accumulated balance

![]() $y$

(measured in units of labor). In current units of nominal money, this is

$y$

(measured in units of labor). In current units of nominal money, this is

![]() $\omega M\times y$

. At the beginning of next period, each individual gets a nominal transfer of new money

$\omega M\times y$

. At the beginning of next period, each individual gets a nominal transfer of new money

![]() $\tau M$

. In units of labor next period, the beginning-of-period balance would thus be

$\tau M$

. In units of labor next period, the beginning-of-period balance would thus be

![]() $m_{+1}=\left (\omega My+\tau M\right )/\left (\omega _{+1}M_{+1}\right )$

. Replacing for

$m_{+1}=\left (\omega My+\tau M\right )/\left (\omega _{+1}M_{+1}\right )$

. Replacing for

![]() $M/M_{+1}$

with the money supply process in (2.3) gives the expression for the individual’s continuation state

$M/M_{+1}$

with the money supply process in (2.3) gives the expression for the individual’s continuation state

![]() $m_{+1}$

in (2.4).

$m_{+1}$

in (2.4).

2.3.2. Ex-post DM buyers

Now we focus on an individual who has just decided to be a DM buyer. The buyer chooses which submarket (or trading post)

![]() $\left (x,q\right )$

to enter, taking the market tightness function

$\left (x,q\right )$

to enter, taking the market tightness function

![]() $\left (x,q\right )\mapsto \theta \left (x,q\right )$

as given. The individual buyer,

$\left (x,q\right )\mapsto \theta \left (x,q\right )$

as given. The individual buyer,

![]() $\textbf{s}\,:\!=\,(m,\omega )$

, has initial value:Footnote

25

$\textbf{s}\,:\!=\,(m,\omega )$

, has initial value:Footnote

25

\begin{align} B(\textbf{s})&=\max _{x\in [0,m],q\in \mathbb{R}_{+}}\left \{ \beta \left [1-b\left (x,q\right )\right ]\left [\bar {V}\left (\frac {\omega m+\tau }{\omega _{+1}\left (1+\tau \right )},\omega _{+1}\right )\right ]\right .\nonumber \\ &\quad +\left .b\left (x,q\right )\left [u(q)+\beta \bar {V}\left (\frac {\omega \left (m-x\right )+\tau }{\omega _{+1}\left (1+\tau \right )},\omega _{+1}\right )\right ]\right \} . \end{align}

\begin{align} B(\textbf{s})&=\max _{x\in [0,m],q\in \mathbb{R}_{+}}\left \{ \beta \left [1-b\left (x,q\right )\right ]\left [\bar {V}\left (\frac {\omega m+\tau }{\omega _{+1}\left (1+\tau \right )},\omega _{+1}\right )\right ]\right .\nonumber \\ &\quad +\left .b\left (x,q\right )\left [u(q)+\beta \bar {V}\left (\frac {\omega \left (m-x\right )+\tau }{\omega _{+1}\left (1+\tau \right )},\omega _{+1}\right )\right ]\right \} . \end{align}

Consider the first two terms on the RHS of Equation (2.5): With probability

![]() $1-b\left (x,q\right )\boldsymbol{\,:\!=\,}1-\lambda \left (\theta \left (x,q\right )\right )$

the buyer fails to match with the trading post and must thus continue the next period with his initial money balance subject to inflationary transfer. With the complementary probability

$1-b\left (x,q\right )\boldsymbol{\,:\!=\,}1-\lambda \left (\theta \left (x,q\right )\right )$

the buyer fails to match with the trading post and must thus continue the next period with his initial money balance subject to inflationary transfer. With the complementary probability

![]() $b\left (x,q\right )\,:\!=\,\lambda \left (\theta \left (x,q\right )\right )$

he matches with a trading post

$b\left (x,q\right )\,:\!=\,\lambda \left (\theta \left (x,q\right )\right )$

he matches with a trading post

![]() $\left (x,q\right )$

, pays the seller

$\left (x,q\right )$

, pays the seller

![]() $x$

in exchange for a flow payoff

$x$

in exchange for a flow payoff

![]() $u\left (q\right )$

, and then continues into the next period with his net balance, also subject to inflationary transfers.

$u\left (q\right )$

, and then continues into the next period with his net balance, also subject to inflationary transfers.

2.3.3. Ex-ante

Given a money balance

![]() $z$

, the individual decides which markets to participate in, and her value becomes

$z$

, the individual decides which markets to participate in, and her value becomes

As shown in Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013), the resulting value function

![]() $B$

in Equation (2.5) may not be strictly concave in

$B$

in Equation (2.5) may not be strictly concave in

![]() $m$

.Footnote

26

This is the case even if primitive functions are strictly concave. As a result, the value function

$m$

.Footnote

26

This is the case even if primitive functions are strictly concave. As a result, the value function

![]() $\tilde {V}$

may not be concave either.Footnote

27

This implies that agents can be weakly better off by choosing a lottery over the pure participation outcomes. Suppose at the beginning of a period, an agent begins with money balance

$\tilde {V}$

may not be concave either.Footnote

27

This implies that agents can be weakly better off by choosing a lottery over the pure participation outcomes. Suppose at the beginning of a period, an agent begins with money balance

![]() $m$

. If there is a non-empty subset

$m$

. If there is a non-empty subset

![]() $\left [z_{1},z_{2}\right ]$

containing

$\left [z_{1},z_{2}\right ]$

containing

![]() $m$

such that any weighted average of the pure-action induced values

$m$

such that any weighted average of the pure-action induced values

![]() $\tilde {V}(z_{1},\omega )$

and

$\tilde {V}(z_{1},\omega )$

and

![]() $\tilde {V}(z_{2},\omega )$

(weakly) dominates

$\tilde {V}(z_{2},\omega )$

(weakly) dominates

![]() $\tilde {V}(m,\omega )$

, then the agent will optimally play a fair lottery

$\tilde {V}(m,\omega )$

, then the agent will optimally play a fair lottery

![]() $\left (\pi _{1},1-\pi _{1}\right )$

over the prizes

$\left (\pi _{1},1-\pi _{1}\right )$

over the prizes

![]() $\left \{ z_{1},z_{2}\right \}$

. This yields the ex-ante value

$\left \{ z_{1},z_{2}\right \}$

. This yields the ex-ante value

2.4. Monetary equilibrium

In this paper, we restrict attention to the case of a monetary equilibrium. Hereinafter, whenever we refer to “monetary equilibrium,” or “equilibrium,” we mean a (Markovian) monetary equilibrium—one in which agent’s decision functions are time-invariant maps. In what follows, we first characterize the equilibrium strategy of firms (section 2.4.1), the equilibrium value and decision functions of agents in the CM (section 2.4.2) and in the DM (section 2.4.3), and then we describe the market clearing conditions in equilibrium (section 2.4.4). At the end of this section, we define formally the notion of a stationary monetary equilibrium (SME).

2.4.1. Equilibrium strategy of firms

A firm’s problem is static. We can characterize the equilibrium behavior of a firm given

![]() $p$

(in the CM). Free entry in the CM will render zero profits to firms in equilibrium, and thus,

$p$

(in the CM). Free entry in the CM will render zero profits to firms in equilibrium, and thus,

![]() $p=1$

. Likewise, free entry and zero-profit in the DM with competitive search imply that

$p=1$

. Likewise, free entry and zero-profit in the DM with competitive search imply that

where the weak inequalities would hold with complementary slackness: For a submarket

![]() $(x,q)$

such that

$(x,q)$

such that

![]() $r(x,q)\lt 0$

, the firm optimally chooses not to post in the submarket. If

$r(x,q)\lt 0$

, the firm optimally chooses not to post in the submarket. If

![]() $r(x,q)=0$

, then the firm is indifferent to creating different numbers of trading posts in submarket

$r(x,q)=0$

, then the firm is indifferent to creating different numbers of trading posts in submarket

![]() $(x,q)$

. We can also deduce that

$(x,q)$

. We can also deduce that

![]() $r(x,q)\gt 0$

cannot be an equilibrium: If expected profit is positive, then this implies

$r(x,q)\gt 0$

cannot be an equilibrium: If expected profit is positive, then this implies

![]() $\theta (x,q)=+\infty$

, and thus

$\theta (x,q)=+\infty$

, and thus

![]() $s\left (\theta (x,q)\right )=0$

which yields a contradiction to the case.Footnote

28

We will restrict attention to an equilibrium where Equation (2.8) also holds for submarkets not visited by any buyer.Footnote

29

$s\left (\theta (x,q)\right )=0$

which yields a contradiction to the case.Footnote

28

We will restrict attention to an equilibrium where Equation (2.8) also holds for submarkets not visited by any buyer.Footnote

29

From (2.8), we can deduce that

\begin{equation} s(x,q)\equiv \mu \circ b\left (x,q\right )=\begin{cases} \frac {k}{x-c(q)} & \iff x-c(q)\gt k\\ 1 & \iff x-c(q)\leq k \end{cases}. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} s(x,q)\equiv \mu \circ b\left (x,q\right )=\begin{cases} \frac {k}{x-c(q)} & \iff x-c(q)\gt k\\ 1 & \iff x-c(q)\leq k \end{cases}. \end{equation}

Observe that the firm’s probability of matching with a buyer,

![]() $s(x,q)\,:\!=\,\rho \left (\theta \left (x,q\right )\right )$

depends only on the posted terms of trade

$s(x,q)\,:\!=\,\rho \left (\theta \left (x,q\right )\right )$

depends only on the posted terms of trade

![]() $(x,q)$

. Likewise, the buyer’s probability of matching with a firm is

$(x,q)$

. Likewise, the buyer’s probability of matching with a firm is

![]() $b(x,q)\,:\!=\,\lambda \left (\theta \left (x,q\right )\right )$

, for a given the matching technology

$b(x,q)\,:\!=\,\lambda \left (\theta \left (x,q\right )\right )$

, for a given the matching technology

![]() $\mu :[0,1]\rightarrow [0,1]$

. Thus, in any submarket with positive measure of buyers, the market tightness,

$\mu :[0,1]\rightarrow [0,1]$

. Thus, in any submarket with positive measure of buyers, the market tightness,

![]() $\theta (x,q)\equiv b(x,q)/s(x,q)$

, is necessarily and sufficiently determined by free entry into the submarket. Moreover, the terms of trade of a submarket

$\theta (x,q)\equiv b(x,q)/s(x,q)$

, is necessarily and sufficiently determined by free entry into the submarket. Moreover, the terms of trade of a submarket

![]() $(x,q)$

is sufficient to identify the submarket. This implies that firms’ and agents’ optimal decision processes do not depend on the equilibrium distribution of agents. They only depend on the distribution through the aggregate statistic

$(x,q)$

is sufficient to identify the submarket. This implies that firms’ and agents’ optimal decision processes do not depend on the equilibrium distribution of agents. They only depend on the distribution through the aggregate statistic

![]() $\omega$

as a result of inflation. The equilibrium will be (partially) block recursive.

$\omega$

as a result of inflation. The equilibrium will be (partially) block recursive.

In equilibrium, there is a relation between

![]() $q$

and

$q$

and

![]() $(x,b)$

. That is, in any equilibrium, each active trading post will produce and trade the quantity:

$(x,b)$

. That is, in any equilibrium, each active trading post will produce and trade the quantity:

given payment

![]() $x$

and its matching probability

$x$

and its matching probability

![]() $s=\mu (b)$

. This relation allows us to perform a change of variables, and re-write the buyers’ problems below in terms choices over

$s=\mu (b)$

. This relation allows us to perform a change of variables, and re-write the buyers’ problems below in terms choices over

![]() $(x,b)$

, instead of over

$(x,b)$

, instead of over

![]() $(x,q)$

.

$(x,q)$

.

2.4.2. Equilibrium CM individual

Denote

![]() $\mathcal{C}[0,\bar {m}]$

as the set of continuous and increasing functions with domain

$\mathcal{C}[0,\bar {m}]$

as the set of continuous and increasing functions with domain

![]() $[0,\bar {m}]$

. Let

$[0,\bar {m}]$

. Let

![]() $\mathcal{V}[0,\bar {m}]\subset \mathcal{C}[0,\bar {m}]$

be the set of continuous, increasing and concave functions on the domain

$\mathcal{V}[0,\bar {m}]\subset \mathcal{C}[0,\bar {m}]$

be the set of continuous, increasing and concave functions on the domain

![]() $[0,\bar {m}]$

.

$[0,\bar {m}]$

.

Proposition 1 (CM value and decision functions)

Assume

![]() $\tau /\omega \lt \bar {m}$

. For a given sequence of prices

$\tau /\omega \lt \bar {m}$

. For a given sequence of prices

![]() $\left \{ \omega, \omega _{+1},\ldots \right \}$

, the value function of the individual beginning in the CM,

$\left \{ \omega, \omega _{+1},\ldots \right \}$

, the value function of the individual beginning in the CM,

![]() $W\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

, has the following properties:

$W\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

, has the following properties:

-

1.

$W\left (\cdot, \omega \right )\in \mathcal{V}[0,\bar {m}]$

, i.e., it is continuous, increasing and concave on

$W\left (\cdot, \omega \right )\in \mathcal{V}[0,\bar {m}]$

, i.e., it is continuous, increasing and concave on

$\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

. Moreover, it is linear on

$\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

. Moreover, it is linear on

$\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

.

$\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

. -

2. The partial derivative functions

$W_{1}\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

and

$W_{1}\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

and

$\bar {V}_{1}\left (\cdot, \omega _{+1}\right )$

exist and satisfy the first-order condition(2.11)and the envelope condition:

$\bar {V}_{1}\left (\cdot, \omega _{+1}\right )$

exist and satisfy the first-order condition(2.11)and the envelope condition: \begin{equation} \frac {\beta }{1+\tau }\left (\frac {\omega }{\omega _{+1}}\right )\bar {V}_{1}\left (\frac {\omega y^{\star }\left (m,\omega \right )+\tau }{\omega _{+1}\left (1+\tau \right )},\omega _{+1}\right )\begin{cases} \leq 1, & y^{\star }\left (m,\omega \right )\geq 0\\ \geq 1, & y^{\star }\left (m,\omega \right )\leq y_{\text{max}}\left (\omega ;\tau \right ) \end{cases}, \end{equation}

(2.12)where

\begin{equation} \frac {\beta }{1+\tau }\left (\frac {\omega }{\omega _{+1}}\right )\bar {V}_{1}\left (\frac {\omega y^{\star }\left (m,\omega \right )+\tau }{\omega _{+1}\left (1+\tau \right )},\omega _{+1}\right )\begin{cases} \leq 1, & y^{\star }\left (m,\omega \right )\geq 0\\ \geq 1, & y^{\star }\left (m,\omega \right )\leq y_{\text{max}}\left (\omega ;\tau \right ) \end{cases}, \end{equation}

(2.12)where \begin{equation} W_{1}\left (m,\omega \right )=1, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} W_{1}\left (m,\omega \right )=1, \end{equation}

$y^{\star }(m,\omega )=m+l^{\star }(m,\omega )-C^{\star }(m,\omega )$

,

$y^{\star }(m,\omega )=m+l^{\star }(m,\omega )-C^{\star }(m,\omega )$

,

$l^{\star }(m,\omega )$

and

$l^{\star }(m,\omega )$

and

$C^{\star }(m,\omega )$

, respectively, are the associated optimal choices on labor effort and consumption in the CM.

$C^{\star }(m,\omega )$

, respectively, are the associated optimal choices on labor effort and consumption in the CM.

-

3. The stationary Markovian policy rules

$y^{\star }\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

and

$y^{\star }\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

and

$l^{\star }\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

are scalar-valued and continuous functions on

$l^{\star }\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

are scalar-valued and continuous functions on

$\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

.

$\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

.

-

(a) The function

$y^{\star }\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

, is constant valued on

$y^{\star }\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

, is constant valued on

$\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

.

$\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

. -

(b) The optimizer

$l^{\star }\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

is an affine and decreasing function on

$l^{\star }\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

is an affine and decreasing function on

$\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

.

$\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

. -

(c) Moreover, for every

$\left (m,\omega \right )$

, the optimal choice

$\left (m,\omega \right )$

, the optimal choice

$l^{\star }(m,\omega )$

is interior:

$l^{\star }(m,\omega )$

is interior:

$0\lt l_{\min }\leq l^{\star }\left (m\right )\leq l_{\max }\left (\omega ;\,\tau \right )\lt +\infty$

, where there is a very small

$0\lt l_{\min }\leq l^{\star }\left (m\right )\leq l_{\max }\left (\omega ;\,\tau \right )\lt +\infty$

, where there is a very small

$l_{\text{min}}\gt 0$

and

$l_{\text{min}}\gt 0$

and

$l_{max}\left (\omega \right )\,:\!=\,y_{\text{max}}\left (\omega ;\,\tau \right )+U^{-1}\left (1\right )\lt 2U^{-1}\left (1\right )\in \left (0,\infty \right )$

.

$l_{max}\left (\omega \right )\,:\!=\,y_{\text{max}}\left (\omega ;\,\tau \right )+U^{-1}\left (1\right )\lt 2U^{-1}\left (1\right )\in \left (0,\infty \right )$

.

In Proposition 1, we provide an extension of the results of Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013) on CM individuals’ value and policy functions to the case with non-zero inflation. (Its proof is relegated to Online Appendix B. The proposition says the following: First,

![]() $W\left (\cdot, \omega \right )\in \mathcal{V}[0,\bar {m}]$

is continuous, increasing and concave on

$W\left (\cdot, \omega \right )\in \mathcal{V}[0,\bar {m}]$

is continuous, increasing and concave on

![]() $\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

, and it is linear on

$\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

, and it is linear on

![]() $\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

. Second, the partial derivative functions

$\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

. Second, the partial derivative functions

![]() $W_{1}\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

and

$W_{1}\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

and

![]() $\bar {V}_{1}\left (\cdot, \omega _{+1}\right )$

exist and satisfy a first-order condition. Third, agents’ optimal money balance and labor decision rules, respectively,

$\bar {V}_{1}\left (\cdot, \omega _{+1}\right )$

exist and satisfy a first-order condition. Third, agents’ optimal money balance and labor decision rules, respectively,

![]() $y^{\star }\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

and

$y^{\star }\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

and

![]() $l^{\star }\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

are scalar-valued and continuous functions on

$l^{\star }\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

are scalar-valued and continuous functions on

![]() $\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

, and their selections are always interior. Also, for a fixed

$\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

, and their selections are always interior. Also, for a fixed

![]() $\omega$

, the graph of

$\omega$

, the graph of

![]() $y^{\star }\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

is downward sloping and that of

$y^{\star }\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

is downward sloping and that of

![]() $l^{\star }\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

is constant-valued or flat. We also derive the equilibrium decisions of the CM agent.

$l^{\star }\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

is constant-valued or flat. We also derive the equilibrium decisions of the CM agent.

2.4.3. Equilibrium DM buyer

Observe that since

![]() $\bar {V}(\cdot, \omega ),W(\cdot, \omega )\in \mathcal{V}[0,\bar {m}]$

(i.e., are continuous, increasing and concave), then by (A.1),

$\bar {V}(\cdot, \omega ),W(\cdot, \omega )\in \mathcal{V}[0,\bar {m}]$

(i.e., are continuous, increasing and concave), then by (A.1),

![]() $\bar {V}\left (\cdot, \omega \right )\in \mathcal{V}[0,\bar {m}]$

. In an equilibrium, the DM buyer’s problem in (2.5) can be re-written as

$\bar {V}\left (\cdot, \omega \right )\in \mathcal{V}[0,\bar {m}]$

. In an equilibrium, the DM buyer’s problem in (2.5) can be re-written as

\begin{align} B(\textbf{s})=\max _{x\in [0,m],b\in [0,1]}\biggl \{\beta (1-b)\left [\bar {V}\left (\frac {\omega m+\tau }{\omega _{+1}\left (1+\omega \right )},\omega _{+1}\right )\right ]\nonumber \\ +b\biggl [u\left (Q(x,b)\right )+\beta \bar {V}\left (\frac {\omega \left (m-x\right )+\tau }{\omega _{+1}\left (1+\tau \right )},\omega _{+1}\right )\biggr ]\biggr \}. \end{align}

\begin{align} B(\textbf{s})=\max _{x\in [0,m],b\in [0,1]}\biggl \{\beta (1-b)\left [\bar {V}\left (\frac {\omega m+\tau }{\omega _{+1}\left (1+\omega \right )},\omega _{+1}\right )\right ]\nonumber \\ +b\biggl [u\left (Q(x,b)\right )+\beta \bar {V}\left (\frac {\omega \left (m-x\right )+\tau }{\omega _{+1}\left (1+\tau \right )},\omega _{+1}\right )\biggr ]\biggr \}. \end{align}

It appears as if the buyer is choosing his matching probability

![]() $b$

along with payment

$b$

along with payment

![]() $x$

. This is comes from a change of variables utilizing the equilibrium relation (2.10) between quantity

$x$

. This is comes from a change of variables utilizing the equilibrium relation (2.10) between quantity

![]() $q$

and terms of trade

$q$

and terms of trade

![]() $(x,b)$

. From this we can begin to see that there will be a trade-off to the buyer, in terms of an extensive margin (i.e., trading opportunity

$(x,b)$

. From this we can begin to see that there will be a trade-off to the buyer, in terms of an extensive margin (i.e., trading opportunity

![]() $b$

), and, an intensive margin (i.e., trading quantity given payment

$b$

), and, an intensive margin (i.e., trading quantity given payment

![]() $x$

).

$x$

).

The operator defined by (2.13) does not preserve concavity: The objective function in (2.13) is not jointly concave in the decisions

![]() $\left (x,b\right )$

and state

$\left (x,b\right )$

and state

![]() $m$

, since it is bilinear in the function

$m$

, since it is bilinear in the function

![]() $b$

and the value function

$b$

and the value function

![]() $\bar {V}$

, or the flow payoff function

$\bar {V}$

, or the flow payoff function

![]() $u$

. However, using lattice programming arguments, we can still show that the resulting DM buyers’ optimal choice functions for

$u$

. However, using lattice programming arguments, we can still show that the resulting DM buyers’ optimal choice functions for

![]() $(x,b)$

, denoted by

$(x,b)$

, denoted by

![]() $\left (x^{\star },b^{\star }\right )$

, are monotone, continuous, and have unique selections.

$\left (x^{\star },b^{\star }\right )$

, are monotone, continuous, and have unique selections.

Proposition 2 (DM value and decision functions)

For a given price sequence

![]() $\left \{ \omega, \omega _{+1},\ldots \right \}$

, the following properties hold.

$\left \{ \omega, \omega _{+1},\ldots \right \}$

, the following properties hold.

-

1. For any

$\bar {V}(\cdot, \omega _{+1})\in \mathcal{V}\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

, the DM buyer’s value function is increasing and continuous in money balances,

$\bar {V}(\cdot, \omega _{+1})\in \mathcal{V}\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

, the DM buyer’s value function is increasing and continuous in money balances,

$B\left (\cdot, \omega \right )\in \mathcal{C}\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

.

$B\left (\cdot, \omega \right )\in \mathcal{C}\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

. -

2. For any

$m\leq k$

, DM buyers’ optimal decisions are

$m\leq k$

, DM buyers’ optimal decisions are

$b^{\star }\left (m,\omega \right )=x^{\star }\left (m,\omega \right )=q^{\star }\left (m,\omega \right )=0$

, and

$b^{\star }\left (m,\omega \right )=x^{\star }\left (m,\omega \right )=q^{\star }\left (m,\omega \right )=0$

, and

$B\left (m,\omega \right )=\beta \bar {V}\left [\phi (m,\omega ),\omega _{+1}\right ]$

, where

$B\left (m,\omega \right )=\beta \bar {V}\left [\phi (m,\omega ),\omega _{+1}\right ]$

, where

$\phi (m,\omega )\,:\!=\,(\omega m+\tau )/\left [\omega _{+1}(1+\tau )\right ]$

.

$\phi (m,\omega )\,:\!=\,(\omega m+\tau )/\left [\omega _{+1}(1+\tau )\right ]$

. -

3. At any

$\left (m,\omega \right )$

, where

$\left (m,\omega \right )$

, where

$m\in \left [k,\bar {m}\right ]$

and the buyer matching probability is positive

$m\in \left [k,\bar {m}\right ]$

and the buyer matching probability is positive

$b^{\star }\left (m,\omega \right )\gt 0$

:

$b^{\star }\left (m,\omega \right )\gt 0$

:

-

(a) The optimal selections

$\left (x^{\star },b^{\star },q^{\star }\right )(m,\omega )$

and

$\left (x^{\star },b^{\star },q^{\star }\right )(m,\omega )$

and

$\phi ^{\star }(m,\omega )\,:\!=\,\phi \left [m-x^{\star }\left (m,\omega \right ),\omega \right ]$

, are unique, continuous, and increasing in

$\phi ^{\star }(m,\omega )\,:\!=\,\phi \left [m-x^{\star }\left (m,\omega \right ),\omega \right ]$

, are unique, continuous, and increasing in

$m$

.

$m$

. -

(b) The buyer’s marginal valuation of money

$B_{1}(m,\omega )$

exists if and only if the marginal ex-ante value of money

$B_{1}(m,\omega )$

exists if and only if the marginal ex-ante value of money

$\bar {V}_{1}\left [\phi (m,\omega ),\omega \right ]$

exists.

$\bar {V}_{1}\left [\phi (m,\omega ),\omega \right ]$

exists. -

(c)

$B(m,\omega )$

is strictly increasing in

$B(m,\omega )$

is strictly increasing in

$m$

.

$m$

. -

(d) the optimal policy functions

$b^{\star }$

and

$b^{\star }$

and

$x^{\star }$

, respectively, satisfy the first-order conditions(2.14)and,

$x^{\star }$

, respectively, satisfy the first-order conditions(2.14)and, \begin{align} &u\circ Q\left [x^{\star }(m,\omega ),b^{\star }(m,\omega )\right ]+b^{\star }(m,\omega )\left (u\circ Q\right )_{2}\left [x^{\star }(m,\omega ),b^{\star }(m,\omega )\right ] \nonumber \\ &\quad =\beta \left [\bar {V}\left (\phi \left (m,\omega \right ),\omega _{+1}\right )-\bar {V}\left (\phi ^{\star }\left (m,\omega \right ),\omega _{+1}\right )\right ], \end{align}

(2.15)

\begin{align} &u\circ Q\left [x^{\star }(m,\omega ),b^{\star }(m,\omega )\right ]+b^{\star }(m,\omega )\left (u\circ Q\right )_{2}\left [x^{\star }(m,\omega ),b^{\star }(m,\omega )\right ] \nonumber \\ &\quad =\beta \left [\bar {V}\left (\phi \left (m,\omega \right ),\omega _{+1}\right )-\bar {V}\left (\phi ^{\star }\left (m,\omega \right ),\omega _{+1}\right )\right ], \end{align}

(2.15) \begin{equation} \left (u\circ Q\right )_{1}\left [x^{\star }(m,\omega ),b^{\star }(m,\omega )\right ]=\frac {\beta }{1+\tau }\left (\frac {\omega }{\omega _{+1}}\right )\bar {V}_{1}\left [\phi ^{\star }(m,\omega ),\omega _{+1}\right ]. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \left (u\circ Q\right )_{1}\left [x^{\star }(m,\omega ),b^{\star }(m,\omega )\right ]=\frac {\beta }{1+\tau }\left (\frac {\omega }{\omega _{+1}}\right )\bar {V}_{1}\left [\phi ^{\star }(m,\omega ),\omega _{+1}\right ]. \end{equation}

Proposition 2 states the properties of a DM agent’s value and policy functions. It extends the results from Menzio et al. (Reference Menzio, Shi and Sun2013) to the setting with non-zero inflation. The proof is given in the appendix, we summarize the idea of the proof: Part 1 of the proposition states that

![]() $B\left (\cdot, \omega \right )\in \mathcal{C}\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

is increasing and continuous in

$B\left (\cdot, \omega \right )\in \mathcal{C}\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

is increasing and continuous in

![]() $m$

. This observation uses standard results from optimization and is contained in Lemma 1 of the appendix. Part 2 is proven in Lemma 2 in the appendix, and its insight here is simple: If buyers do not carry enough money to at least pay for a trading post’s fixed cost, no firm will want to set up that post in equilibrium, and so the buyers get nothing. Part 3(a) is proven in Lemma 3 using the fact that a log-transform of a DM buyer’s objective function is jointly concave in the choice variables

$m$

. This observation uses standard results from optimization and is contained in Lemma 1 of the appendix. Part 2 is proven in Lemma 2 in the appendix, and its insight here is simple: If buyers do not carry enough money to at least pay for a trading post’s fixed cost, no firm will want to set up that post in equilibrium, and so the buyers get nothing. Part 3(a) is proven in Lemma 3 using the fact that a log-transform of a DM buyer’s objective function is jointly concave in the choice variables

![]() $\left (x,b\right )$

, and is continuous in

$\left (x,b\right )$

, and is continuous in

![]() $m$

(fixing the aggregate state

$m$

(fixing the aggregate state

![]() $\omega$

). It nevertheless satisfies an increasing difference—and therefore, supermodularity—property. Thus, by lattice programming arguments, we can show that the DM buyer’s optimal policies are increasing in

$\omega$

). It nevertheless satisfies an increasing difference—and therefore, supermodularity—property. Thus, by lattice programming arguments, we can show that the DM buyer’s optimal policies are increasing in

![]() $m$

. Lemmata 4 and 5 in the appendix, together establish the following properties (Parts 3(b) and 3(c) of Proposition 2): Whenever a buyer has a chance of matching, her value function is differentiable. As a result, we can also characterize her best response in terms of a matching probability (extensive margin) and spending level (intensive margin) via Euler equations—see Part 3(d) in Proposition 2—and this is proven in Lemma 6.

$m$

. Lemmata 4 and 5 in the appendix, together establish the following properties (Parts 3(b) and 3(c) of Proposition 2): Whenever a buyer has a chance of matching, her value function is differentiable. As a result, we can also characterize her best response in terms of a matching probability (extensive margin) and spending level (intensive margin) via Euler equations—see Part 3(d) in Proposition 2—and this is proven in Lemma 6.

2.4.4. Market clearing

In equilibrium, the total production of CM good equals its demand,

![]() $Y=C$

. Given equilibrium policy functions,

$Y=C$

. Given equilibrium policy functions,

![]() $x^{\star }$

and

$x^{\star }$

and

![]() $b^{\star }$

, the equilibrium distribution of money

$b^{\star }$

, the equilibrium distribution of money

![]() $G$

, and wage

$G$

, and wage

![]() $\omega$

, Equation (2.10) pins down market clearing conditions for each submarket in the set of equilibrium submarkets. Money demanded must also equal money supplied:

$\omega$

, Equation (2.10) pins down market clearing conditions for each submarket in the set of equilibrium submarkets. Money demanded must also equal money supplied:

Since

![]() $M$

is the beginning of period aggregate stock of money in circulation, the LHS of (2.16),

$M$

is the beginning of period aggregate stock of money in circulation, the LHS of (2.16),

![]() $1/\omega =M\times 1/\omega M$

, is the beginning of period real aggregate stock of money, measured in units of labor. The RHS of (2.16) is beginning of period aggregate demand, or holdings, of real money balances measured in the same unit.

$1/\omega =M\times 1/\omega M$

, is the beginning of period real aggregate stock of money, measured in units of labor. The RHS of (2.16) is beginning of period aggregate demand, or holdings, of real money balances measured in the same unit.

2.5. Existence of a SME with a unique distribution

For the rest of the paper, we focus on a stationary monetary equilibrium (SME), which comprises the characterizations from Section 2.4, where prices are constant over time:

![]() $\omega =\omega _{+1}$

.

$\omega =\omega _{+1}$

.

Definition 1.

A stationary monetary equilibrium (SME), given an exogenous monetary policy

![]() $\tau$

, is:

(i.)

a list of value functions

$\tau$

, is:

(i.)

a list of value functions

![]() $\textbf{s}\mapsto (W,B,\bar {V})(\textbf{s})$

, satisfying the Bellman equation, jointly in (2.4), (2.5), (2.6) and (2.7);

(ii.)

a list of corresponding decision rules

$\textbf{s}\mapsto (W,B,\bar {V})(\textbf{s})$

, satisfying the Bellman equation, jointly in (2.4), (2.5), (2.6) and (2.7);

(ii.)

a list of corresponding decision rules

![]() $\textbf{s}\mapsto (l^{\star },y^{\star },b^{\star },x^{\star },q^{\star },z^{\star },\pi ^{\star })(\textbf{s})$

supporting the value functions;

(iii.)

a market tightness function

$\textbf{s}\mapsto (l^{\star },y^{\star },b^{\star },x^{\star },q^{\star },z^{\star },\pi ^{\star })(\textbf{s})$

supporting the value functions;

(iii.)

a market tightness function

![]() $\textbf{s}\mapsto \mu \circ b^{\star }(\textbf{s})$

given a matching technology

$\textbf{s}\mapsto \mu \circ b^{\star }(\textbf{s})$

given a matching technology

![]() $\mu$

, satisfying firms’ profit maximizing strategy (2.9) and (2.10) at all active trading posts;

(iv.)

a wage rate function

$\mu$

, satisfying firms’ profit maximizing strategy (2.9) and (2.10) at all active trading posts;

(iv.)

a wage rate function

![]() $\textbf{s}\mapsto \omega (\textbf{s})$

satisfying the money stock adding up condition (2.16); and

(v.)

an ergodic distribution of real money balances

$\textbf{s}\mapsto \omega (\textbf{s})$

satisfying the money stock adding up condition (2.16); and

(v.)

an ergodic distribution of real money balances

![]() $G(\textbf{s})$

satisfying an equilibrium law of motion

$G(\textbf{s})$

satisfying an equilibrium law of motion

where

![]() is the Borel

is the Borel

![]() $\sigma$

-algebra generated by open subsets of the product state space

$\sigma$

-algebra generated by open subsets of the product state space

![]() $S$

, and,

$S$

, and,

![]() $\textbf{s}\mapsto P({\textbf {s}},\cdot )$

is a Markov kernel induced by agents’ best responses

$\textbf{s}\mapsto P({\textbf {s}},\cdot )$

is a Markov kernel induced by agents’ best responses

![]() $(l^{\star },x^{\star },q^{\star },z^{\star },\pi ^{\star })$

and equilibrium matching

$(l^{\star },x^{\star },q^{\star },z^{\star },\pi ^{\star })$

and equilibrium matching

![]() $\mu \circ b^{\star }$

.

$\mu \circ b^{\star }$

.

In Online Appendix D we show that a composite Bellman function for each agent satisfies Banach’s fixed point theorem. Then, from Propositions 1 and 2, we know that agents’ decision functions are monotone and continuous. This implies that for a fixed

![]() $\omega$

, the equilibrium Markov operator on a current distribution of agents

$\omega$

, the equilibrium Markov operator on a current distribution of agents

![]() $G$

is a monotone map and satisfies measurability conditions. This implies a monotone mixing property as a result of the equilibrium self-map (2.17) on the space of distributions

$G$

is a monotone map and satisfies measurability conditions. This implies a monotone mixing property as a result of the equilibrium self-map (2.17) on the space of distributions

![]() $G$

. These allow us to conclude that there is a unique fixed point (in a weak-convergence sense). Finally, we also show that there is at least one fixed point in the space of

$G$

. These allow us to conclude that there is a unique fixed point (in a weak-convergence sense). Finally, we also show that there is at least one fixed point in the space of

![]() $\omega$

satisfying the SME conditions by utilizing the intermediate value theorem.Footnote

30

$\omega$

satisfying the SME conditions by utilizing the intermediate value theorem.Footnote

30

Theorem 1.

There is a SME with a unique nondegenerate distribution

![]() $G$

.

$G$

.

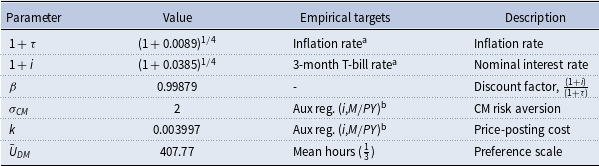

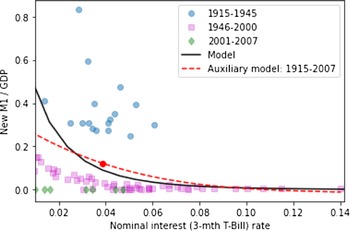

3. Calibrating the SME for analyses

Finding a SME requires numerical computation. In this section, we briefly comment on our contribution in terms of a novel computational solution method. Then, we calibrate the model to the US economy and describe the equilibrium properties of the benchmark model.

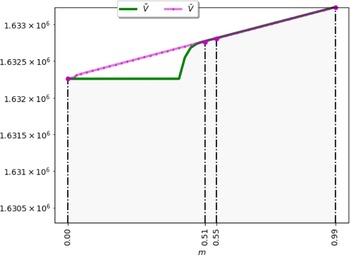

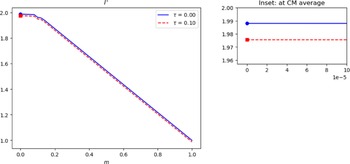

3.1. A novel computational scheme

Recall that the directed search problem makes the value function

![]() $\tilde {V}$

$\tilde {V}$

![]() $\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

non-concave. Since there may exist lotteries that make agents better off than playing pure strategies over participating in DM or CM, we have to devise a means for finding these lotteries that convexify the graph of the function

$\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

non-concave. Since there may exist lotteries that make agents better off than playing pure strategies over participating in DM or CM, we have to devise a means for finding these lotteries that convexify the graph of the function

![]() $\tilde {V}\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

. A common way to do this is to discretize the function’s original domain of

$\tilde {V}\left (\cdot, \omega \right )$

. A common way to do this is to discretize the function’s original domain of

![]() $\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

. Then, around each finite element of the domain, one must check if there is a linear segment that approximately convexifies

$\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

. Then, around each finite element of the domain, one must check if there is a linear segment that approximately convexifies

![]() $graph\left [\tilde {V}\left (\cdot, \omega \right )\right ]$

. This is prone to compounded errors, especially if the grid is coarse.Footnote

31

This approximation scheme works fine when we only have a lottery where the lower bound in the domain

$graph\left [\tilde {V}\left (\cdot, \omega \right )\right ]$

. This is prone to compounded errors, especially if the grid is coarse.Footnote

31

This approximation scheme works fine when we only have a lottery where the lower bound in the domain

![]() $\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

is included, i.e., a lottery on a set like

$\left [0,\bar {m}\right ]$

is included, i.e., a lottery on a set like

![]() $\left \{ 0,z_{2}\right \}$

, where

$\left \{ 0,z_{2}\right \}$

, where

![]() $z_{2}\lt \bar {m}$