Introduction

Rare earth elements (REEs) comprise 17 critical resources that underpin a vast array of modern technologies. Their unique properties make them irreplaceable in many applications, from permanent magnets driving wind turbines and electric vehicles to high-performance electronics and lasers (Natural Resources Canada, 2024). REEs possess a unique blend of optical, mechanical, electronic, and magnetic properties and are poised to revolutionize modern engineering. REEs enable devices with lower energy consumption, enhance technological efficiency, facilitate miniaturization for smaller and lighter devices, and increase the operational speed in specific applications. REEs are pivotal in the development of environmentally friendly energy solutions and are crucial for combating climate change. Projections indicate that REEs are critical components of the forthcoming mid-21st-century technological revolution (Duchna & Cieślik, Reference Duchna, Cieślik and Aide2022). REEs are critical in all military technologies and are central to national security (Auslin, Reference Auslin2024).

China currently holds a dominant position in the REE market, accounting for approximately 70% of the global production capacity and control over the supply chain (Bielawski, Reference Bielawski2020). The processing of REEs presents challenges, such as intricate extraction processes, environmental hazards, and difficulties in separating different REEs from one another (Davris et al., Reference Davris, Balomenos, Taxiarchou, Panias and Paspaliaris2017; Suli et al., Reference Suli, Wan Ibrahim, Abdul Aziz, Deraman and Ismail2017). As the demand for REEs in clean energy and defense technologies continues to grow, efforts are being made globally to reduce dependence on China by exploring alternative sources and enhancing recycling and substitution methods.

The expansion of REE exploration outside China has revealed substantial resources, totaling 98 million metric tons in 2015. However, several significant obstacles must be overcome. Although these resources have the potential to diversify the REE market beyond China, the challenges of processing make development difficult. This situation may prove advantageous for China, the current dominant force in the REE market, because it may be able to acquire these resources for future use (Paulick & Machacek, Reference Paulick and Machacek2017).

The impact of geographical distribution on international relations and state-to-state interactions is known as geopolitics. The geopolitics of REEs examine the political and economic dynamics surrounding the production, distribution, and control of these resources. This includes analyzing the strategic importance of REEs, countries with significant reserves, and the consequences of their control or restriction on national security and economic interests. In this regard, countries such as the United States rely on access to these resources from a limited number of suppliers, particularly China. The dependence on China for REEs can have serious negative consequences for a country’s military capabilities, technological advancements, and economic competitiveness (Chapman, Reference Chapman2018). Consequently, countries are looking for ways to reduce their dependency on China and ensure self-sufficiency in energy transitions. For example, India and the United States are collaborating to develop technology for processing REEs (Vishnoi, Reference Vishnoi2024). A Financial Times study published in 2021 investigated China’s control of REE exports, which are crucial for producing US military technology, such as F-35 fighter jets, as a potential new point of friction between the two nations (Sun & Sevastopulo, Reference Sun and Sevastopulo2021).

In 2023, the Chinese government implemented export limitations, initially targeting gallium and germanium, followed by additional restrictions to include graphite. Additionally, on December 21, 2023, China announced a ban on REEs and separation technologies, with significant implications for U.S. national, economic, and rare earth security (Baskaran, Reference Baskaran2024). This ongoing escalation of trade restrictions has resulted in heightened geopolitical tensions and highlights the potential impact of these developments on the global supply chain, particularly in the context of modern military technology that relies heavily on REEs, as indicated by the Canadian Mining Report for 2023 (Canadian Mining Report, 2023).

The Arctic region has emerged as a critical area for geopolitical rivalry owing to its wealth of natural resources and the recent opening of new shipping pathways (Tomić, Reference Tomić2023). This article examines the evolving discourse on REEs in the Arctic driven by the exposure of extensive reserves due to receding ice and the resulting geopolitical concerns surrounding mineral dependency. By employing the methodology of discourse analysis (Benites-Lazaro et al., Reference Benites-Lazaro, Giatti and Giarolla2018), this study analyzes scholarly publications from 2010–2025 and media coverage from 2012–2025 to identify key research areas and major themes shaping the discourse. While the media shapes public perception and scholars analyze risks, strategic documents reflect the state’s geopolitical intentions. Examining all three provides insight into the interplay between policy, public sentiment, and science. This study specifically focuses on regions in the Swedish, Russian, Finnish, Canadian, US, and Greenlandic Arctic, which are becoming increasingly significant due to their potential REE deposits.

This study examined the dominant discourse themes related to REEs in the Arctic region with a particular emphasis on geopolitical considerations and the REE development impacts on societies, economies, and ecosystems. This research contributes to the importance of responsible resource management and sustainable development and points to the intricate connection between attaining climate objectives and addressing geopolitical challenges in the Arctic area.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows: it provides background information on REEs and Arctic reserves of REEs, details the methodology and data used in the study, analyzes strategic documents, scholarly and media discourses, and concludes with discussions and conclusions.

Background

Critical geopolitics

This study adopts a critical geopolitics framework to examine discourses surrounding REEs in strategic, media, and scholarly discourses on the Arctic. The rationale for this choice lies in the recognition that geopolitics is not reducible to the spatial logics of resource distribution; rather, it is constituted through discursive practices that shape imaginaries, legitimize authority, and influence policy trajectories (Nsude, Reference Nsude2025). By foregrounding discourse analysis, this approach enables an exploration of how resource control is articulated within broader geopolitical projects, thereby revealing the interplay between material realities and symbolic constructions (Huber, Reference Huber2015). Discourses operate as instruments of power, framing geopolitical realities and stabilizing particular configurations of dominance. The production and reproduction of geopolitical discourses consolidate authority within the energy sector, often obscuring the complexity of underlying relations (Nsude, Reference Nsude2025). These discourses frequently invoke dependency tropes, such as reliance on foreign oil, demonstrating that energy considerations are central to theorizing international relations and geopolitical imaginaries (Huber, Reference Huber2015). Furthermore, discourses surrounding renewable energy and energy security recalibrate alliances and strategic orientations during periods of conflict, as exemplified by the Russian-Ukrainian war (Madubuko, Reference Madubuko2024).

Intensifying competition for resources critical to emerging technologies further underscores the discursive dimension of geopolitics. Historical discourses expand or contract under contemporary pressure, reframing resource reliance in ways that intersect with technological and environmental imperatives (Gulley et al., Reference Gulley, Nassar and Xun2018). Such shifts demand an analytical lens that transcends physical availability, interrogating how narratives shape public policy and international governance (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li-mao, Zhong, Xiang and Qu2023). Consequently, lifecycle sustainability assessments must integrate geopolitical considerations with geological models, reinforcing the emphasis on multilayered discourse analysis attentive to power relations, historical trajectories, and political insights (Gemechu et al., Reference Gemechu, Helbig, Sonnemann, Thorenz and Tuma2015).

The transition from hydrocarbon dependence to critical minerals encapsulates a broader geopolitical reconfiguration, wherein resource control and narrative framing converge within global energy debates. This shift foregrounds enduring questions of power and identity as states negotiate pathways toward sustainable development (Gökçe, Reference Gökçe2024). In this sense, critical geopolitics functions as a framework for understanding how resource-related discourses circulate across strategic, media, and scholarly domains, shaping perceptions and practices in Arctic geopolitics (Huber, Reference Huber2015; Madubuko, Reference Madubuko2024; Nsude, Reference Nsude2025).

REE’s definition

Critical minerals encompass a diverse range of naturally occurring inorganic substances that are crucial for driving economic growth, safeguarding national security, and enhancing industrial competitiveness across various sectors. REEs comprise a group of 17 chemical elements in the periodic table. This group includes 15 lanthanides, spanning atomic numbers 57–71, along with scandium and yttrium. With their shared chemical characteristics, REEs play indispensable roles as essential components in numerous contemporary technologies, underpinning advancements in various industries (Schulz et al., Reference Schulz, DeYoung, Seal and Bradley2017). These elements, including praseodymium, gadolinium, and neodymium, belong to the lanthanide series and are chemically similar. Despite their names, their rarity refers to their dispersion rather than their abundance in nature (Fatunde, Reference Fatunde2024). As the retreat of Arctic ice unveils previously undiscovered deposits of REEs, the potential for conflict over their economic and strategic significance has become a growing concern, as illustrated by Bert Chapman, a professor at Purdue University:

“Human nature is inherently contentious, particularly when crucial economic and national security interests are at stake” (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2018).

The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects a significant rise in the demand for REEs, with estimates ranging from three to seven times the current levels by 2040 (IEA, 2021). To achieve the objectives of the Paris Agreement, which aims to restrict the global temperature rise, a fourfold increase in the global mineral supply by 2040 is necessary. However, current projections suggest that supply will only double during the same period. It is noteworthy that all but one of the 17 REEs have been designated as “critical materials,” making them economically significant and vulnerable to supply interruptions.

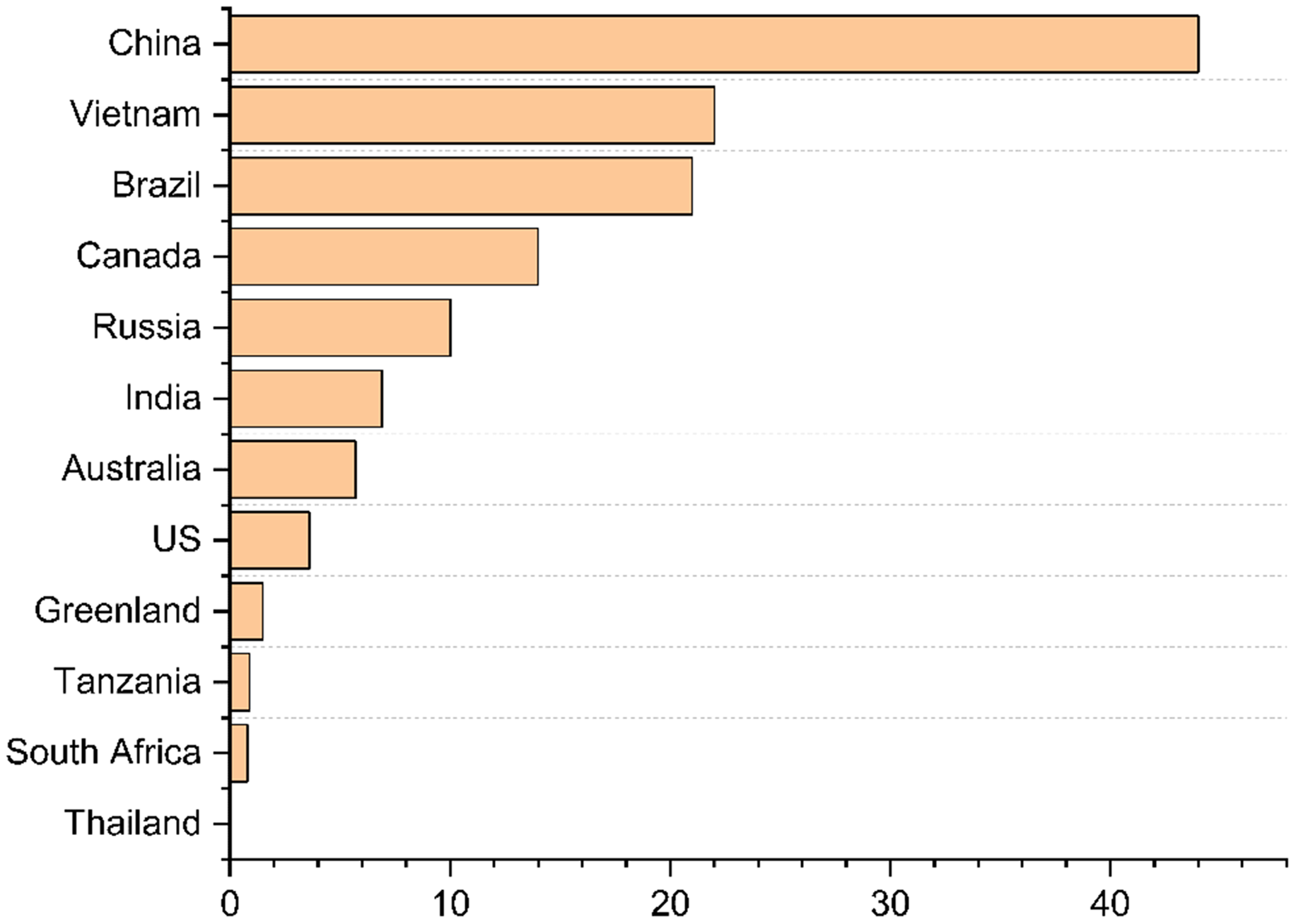

The long-term equilibrium between supply and demand for REEs is heavily influenced by China (see Figure 1). The United States, Burma, and Australia are other significant contributors, accounting for 12%, 11%, and 5% of global production, respectively. The data for China reflect only the production quota and do not include undocumented production. The insignificant production and processing knowledge of REEs in the rest of the world further emphasizes the importance of China’s role in supplying these elements. It is important to note that each rare earth deposit is unique and contains different proportions of various REEs, resulting in different production quantities for individual elements (Al-Ani & Pakkanen, Reference Al-Ani and Pakkanen2013).

Figure 1. Mine production of REEs by country in 2023. Source: Rare Earth 2024, US Government Geological Survey. Chart created by the author.

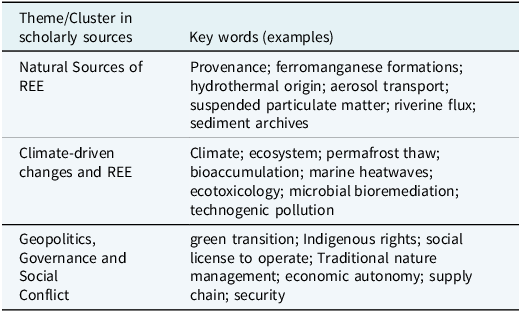

Globally, there are vast untapped reserves of REEs, the majority of which are yet to be explored. As shown in Figure 2, the distribution of known reserves by country reveals that China leads by over 40%, followed by Vietnam (20%), Brazil (19%), Canada (13%), and Russia (9%). Although Greenland has significant reserves, totaling 1,500,000, it only accounts for 2% of the known world reserves. This suggests that Greenland has the potential to become a significant Arctic player in the REE mining industry even though the political and environmental factors surrounding resource extraction are complex. REEs are relatively abundant in the Earth’s crust, but mineable concentrations are less common than for most other mineral commodities. In North America, measured and indicated resources of REEs were estimated to include 3.6 million tons in the United States and over 14 million tons in Canada.

Figure 2. World mine reserves of REEs by country in 2023 in million tons. Source: Rare Earth 2024, US Government Geological Survey. Reserves in Australia, Russia, Thailand, and the United States were revised based on company and government reports. Chart created by the author.

Arctic REE reserves

Canada

Canada is home to a substantial amount of REEs, with an estimated 14 million tons of rare earth oxides available by 2023. Despite these significant reserves, the extraction and refinement processes for REEs are highly complex and present significant challenges for countries such as Canada. Currently, there are three sites in the processing stage, while the majority are in the exploration, resource estimation, and preliminary economic assessments and feasibility stages (Natural Resources Canada, 2024). According to Exner-Pirot (2024), significant increases in critical minerals, including REEs, are needed to achieve net-zero goals, and investor hesitancy and long project timelines hinder domestic mining development. Strategic stockpiles, similar to the IEA’s oil reserves, could incentivize Western production, mitigate supply chain disruptions, and diversify sources away from China (Exner-Pirot, 2024). However, designing such a system requires careful consideration of market dynamics, optimal reserve levels, funding mechanisms, and international cooperation to avoid market distortions.

Greenland

Greenland possesses several sizable REE deposits dispersed across various geological formations. Among these, the most prominent deposits were found within the peralkaline intrusions linked to the Gardar Province in southern Greenland. Notably, these deposits encompass the reserves surrounding Kvanefjeld, Kringlerne, and Motzfeldt Sø (see Map 1).

Map 1. The known REE deposits/occurrences in Greenland (©GEUS). Source: The EURARE project hosted by the British Geological Survey.

Russia

The Arctic region of Russia has crucial REE deposits, which play an important role in global mineral supply and strategic resource security. Notably, over 60% of the nation’s REE reserves and approximately 90% of certain categories are concentrated in the Arctic region. Operational deposits, such as the Lovozero deposit in the Murmansk region, along with active contributors such as the Khibiny Group of deposits, demonstrate the Arctic’s significance. Additionally, deposits such as the Africanda perovskite-titanomagnetite and the Tomtor deposit show promising concentrations of valuable elements, emphasizing the vital role of the Arctic in Russia’s REE industry (Solovyova & Cherepovitsyna, Reference Solovyova and Cherepovitsyna2023).

USA

The potential for REE mining in Alaska is substantial given the growing global demand for these materials. Existing mines, such as the Red Dog Mine, which primarily produces lead and zinc, also have the potential to recover byproducts such as indium and germanium. Furthermore, new mines, such as the Bokan-Dotson Ridge REE project, are being developed to increase domestic REE production. Ucore Rare Metals intends to establish the Alaska Strategic Metals Complex (SMC) processing plant, which will serve as a precursor to the development of the Bokan-Dotson Ridge mine. The plant, estimated to cost $35 million, is envisioned to be located in the Ketchikan Gateway Borough and aims to become one of the nation’s first REE processing facilities, transforming US-allied-sourced feedstock into domestically produced REE oxides (Orr, Reference Orr2021).

Sweden

In January 2023, the state-owned mining company LKAB announced the identification of the Per Geijer deposit near Kiruna, estimating resources of over one million metric tons of rare earth oxides. Although this represents Europe’s largest reported deposit of its kind, industry experts have urged caution regarding its immediate viability. Geologists note that REEs in Per Geijer are bound within apatite minerals as a by-product of iron ore, necessitating complex processing infrastructure that is not yet commercially operational. Analysts such as Per Kalvig have also pointed out that the deposit’s existence has been documented for decades, suggesting that high-profile disclosure was strategically timed to highlight Europe’s critical mineral dependency during Sweden’s EU presidency (Milne, Reference Milne2023).

Beyond Kiruna, geological potential for REEs in the Swedish Arctic links primarily to similar Iron Oxide-Apatite (IOA) formations. Notable rare earth-bearing apatite concentrations exist at the Malmberget mine near Gällivare and the Svappavaara ore fields (Boliden, 2021). Similar to Per Geijer, these deposits are not standalone REE mines but contain rare earths as by-products within iron ore bodies, with extraction tied to iron mining economics and logistics.

Finland

A study conducted by the Finnish Minerals Group uncovered a substantial amount of REEs in the SOKLI mineral deposit in Savukoski, Eastern Lapland. The deposit contains a greater quantity of these metals than previously believed, and it has the potential to provide Europe with 10% of its annual REEs for the production of permanent magnets, as well as meeting over 20% of the region’s phosphate demand for fertilizer production. Acquired from Yara in 2020, the deposit also contains REEs, copper, silver, and uranium. The Finnish Minerals Group has identified the potential for economically feasible and environmentally sustainable mining operations, with estimated construction costs of 1–1.5 billion euros. Assuming that the necessary permits are obtained, mining infrastructure construction can begin in the early part of the next decade. Further investigations and necessary permitting processes are still required (Finnish Minerals Group, 2024).

Methodology and data

Discourse analysis

This article examines the shifting discourse surrounding REE mining in the Arctic region. Utilizing the content analysis approach outlined by Benites-Lazaro et al. (Reference Benites-Lazaro, Giatti and Giarolla2018), this study employs a comprehensive dataset comprising two primary sources: academic literature from 2010 to 2025 and media coverage, including news articles and reports from credible media outlets published between 2012 and 2025. The search terms for media coverage were aligned with those used in scholarly publications to ensure thematic consistency, with “Arctic” and “rare earths” serving as the key search words.

The collected data were subjected to a qualitative content analysis process using Tropes (a semantic analysis software designed to extract relevant information from texts). Thematic analysis and coding techniques were applied to identify recurring themes, arguments, and perspectives presented by scholarly and media sources. To ensure a comprehensive analysis, distinct keyword lists were developed for each thematic cluster (see Appendix C). In scholarly literature, the natural baseline cluster used terms like “provenance” and “hydrothermal,” reflecting the focus on geological baselines. In media sources, the Geopolitics, Governance, and Social Conflict cluster employed keywords such as “technological sovereignty,” “strategic competition,” and “security,” highlighting resources as national assets. Given the interdisciplinary nature of the subject, single articles often contributed to multiple clusters; for example, mining impact studies could address both ecological risks and indigenous rights.

To delineate the boundaries of the research field, the extracted terms were categorized based on semantic proximity and disciplinary focus. This analysis resulted in the identification of three distinct yet interrelated integrated clusters. A detailed breakdown of the specific keywords and concepts used to define these clusters is provided in Appendix C. However, it is important to acknowledge the inherent limitations of this methodology. This study is not a comprehensive review of all possible publications, as it is constrained by the databases used; rather, it is an exploratory study designed to map emerging themes and shifting trajectories across diverse discourses. Specifically, the keyword selection process may have inadvertently excluded relevant publications, and the qualitative nature of the analysis introduced the possibility of subjective bias in data interpretation.

Data

The Scopus database was utilized for the purpose of sourcing scholarly articles for the period 2014–2025, with a total of 360 articles obtained through the search parameters “rare earth” and “Arctic.” Of these, 202 articles were excluded because they pertained to the Earth and Planetary Science domain, which falls outside the scope of this study. This study focuses on discourses pertaining to the environmental and socio-economic impacts of REEs in the Arctic. Among the 121 identified documents, the largest subject areas represented were Environmental Science (93) and Social Sciences (30), followed by smaller clusters in Energy, Multidisciplinary, and Economics, with some documents appearing in multiple categories due to disciplinary overlap. Geographically, the publications were predominantly from the Russian Federation (49), followed by Canada (14), China (12), and the United States (11), with the remaining documents originating from various other countries. The final corpus of papers included 111 available papers.

The ABI/INFORM Complete (ProQuest) database was employed to conduct a media discourse search using the search parameters “rare earth” and “Arctic,” for which 74 newspaper articles and trade reports were available starting from 2012 till November 2025. This bibliographic database indexes a vast array of scholarly and popular literature pertinent to business and economics. Notably, 28 publications were from 2025, indicating a surge in global interest in this topic.

Analysis of strategic documents related to REE

In the Arctic region, strategic approaches to mining activities of REE intertwine economic ambitions with environmental considerations and global energy trends. The US government’s Arctic Strategy emphasizes sustainable growth in Alaska, prioritizing renewable energy, critical minerals, and tourism to foster job creation while ensuring energy transition and protecting biodiversity (US National Strategy for the Arctic region, 2022).

Greenland focuses on reducing global CO2 emissions by making minerals available for renewable energy production and prioritizing climate-friendly trade partnerships, particularly with neighboring markets such as the US and Canada (Greenland’s Arctic Strategy, 2024). Finland underscores the significance of strategic earth metals and minerals in the development of battery technology, aligning with its battery strategy aimed at fostering sustainable mining activities and supporting global energy transitions (Finland’s Strategy for Arctic Policy, 2021). In Sweden’s Arctic strategy, the extraction of ore and minerals, including REE, is recognized as pivotal in meeting the growing demand for metals essential to circular and fossil-free energy technologies (Sweden’s strategy for the Arctic region, 2020). Russia’s Arctic strategy includes REE exploration on the Kola Peninsula and the development of mineral resource centers in the Anabar and Lena basins (Russia’s Arctic Strategy, 2020).

To address the demand for critical raw materials essential for green and digital transitions amidst security and geopolitical considerations, the EU has adopted the Critical Materials Act (Critical Materials Act, 2023). This legislation underscores the pressing need for substantial investment, both globally and within Europe, to address these demands. Estimates project that by 2030 and 2040, investments of EUR 7 billion and EUR 13.2 billion, respectively, are necessary to meet 25% of European demand for key battery materials domestically, requiring significant public support. Initiatives like the European Raw Materials Alliance aim to secure a substantial portion of European demand by 2030 through targeted investments totaling EUR 1.7 billion for REEs and EUR 3.1 billion for other critical raw materials.

Arctic nations see REE mining as crucial for the green energy transition but emphasize sustainability and environmental protection alongside economic development. The EU is looking to the Arctic through the Critical Materials Act and the European Raw Materials Alliance in these resource-rich regions.

Analysis of scholarly discourse related to REE in the Arctic

Natural Sources of REE

Natural baselines for REE in the Arctic

A crucial step in evaluating the environmental impact of future REE mining is setting clear natural baseline measurements of what exists in the environment before any extraction begins. This matters, especially in the US and Greenlandic Arctic, where REE mining has not yet started. Scientists currently have a valuable “baseline window” that allows them to distinguish between natural geological patterns and potential future contamination from human activities.

In Arctic marine environments, layers of sediment on the ocean floor act as natural records. Scientists have found specific mineral patterns in iron-manganese deposits on the seafloor of the Chukchi and East Siberian Seas, which they have traced to natural processes: chemical settling in seawater and input from submarine hot springs rather than industrial pollution (Astakhov et al., 2019; Cui et al., 2020). More recent work has directly linked iron-manganese formations in the East Siberian Sea to submarine hydrothermal vents (underwater hot springs) based on their high iron content and distinctive REE signatures (Sattarova et al., 2025). When researchers analyzed deep-sea sediments from the Gakkel Ridge using advanced techniques, they discovered unique chemical fingerprints, such as specific ratios of cerium and europium, that definitively connect these materials to volcanic activity on the seafloor (Xue et al., 2025).

On land, similar baseline work in the Canadian Arctic has confirmed that REE concentrations found in ancient archaeological soils simply mirror the local bedrock and sediments left behind by glaciers, which proves that these elements come from natural geological sources, not human activity (Butler & Dawson, 2018). In Greenland, extensive mapping of stream sediments has allowed scientists to identify specific regions that are naturally enriched in REEs because of rare rock types called carbonatites, further clarifying the differences between natural geological hotspots and actual pollution (Steenfelt, 2012). These baseline studies establish the natural background against which any future mining impact can be measured, ensuring that human-induced changes in the Arctic can be detected and assessed.

Arctic air and ice transport

The Arctic atmosphere and ice act as global transport systems for particles. Long-term air monitoring in Svalbard found that while pollutants such as lead vary seasonally with industrial winds, REE levels stay remarkably steady year-round, suggesting that they come mainly from natural crustal dust rather than human sources (Bazzano et al., 2016; Conca et al., 2019; Giardi et al., Reference Giardi, Traversi, Becagli, Severi, Caiazzo, Ancillotti and Udisti2018). Ice cores have preserved these signals for thousands of years. Studies using isotopic tracers in Greenland ice have reconstructed where dust originated and how ice sheets changed historically (Graly et al., 2018; Parker et al., 2022). Analysis of dust in Greenland’s melting “dark region” showed that its composition matches the average crustal material, ruling out local volcanic eruptions as a major source (Wientjes et al., 2011). In the context of Arctic discourse, establishing this ‘natural baseline’ is geopolitically critical, as it creates the standard required to distinguish future industrial negligence from background noise in, for example, upcoming transboundary pollution disputes.

River transport to the Arctic Ocean

Rivers are the main pathway for moving REEs from land to the Arctic Ocean. Seasonal extremes, particularly spring floods, drive this process. Peak floodwaters in the Kolyma River mobilize large amounts of dissolved organic carbon and REEs that accumulate in thawing soils during summer (Shulkin et al., 2025). This transport is strongly particle-bound because suspended sediments in the Ob River mouth carry far more REEs than dissolved water (Soromotin et al., 2022). However, when rivers meet the ocean, mixing causes particles to clump and settle, trapping significant amounts of REEs in coastal zones rather than releasing them into open waters (Shirokova et al., 2017).

Climate-driven changes and REEs

Permafrost thaw and REE release

Arctic warming is disrupting geochemical cycles that have historically controlled REE distribution. Thawing permafrost releases metals that have been locked away for thousands of years, increasing baseline concentrations in wetland ecosystems (Jessen et al., Reference Jessen, Holmslykke, Rasmussen, Richardt and Holm2014). In subarctic peatlands, permafrost degradation allows REEs to dissolve and enter lakes, where they are often carried by organic matter (Manasypov et al., Reference Manasypov, Pokrovsky, Shirokova, Auda, Zinner, Vorobyev and Kirpotin2021; Oleinikova et al., Reference Oleinikova, Shirokova, Drozdova, Lapitskiy and Pokrovsky2018). Extreme weather can disrupt these patterns; for instance, an unusually hot summer in the Russian subarctic sharply reduced dissolved REE levels because elevated temperatures boosted microbial breakdown of the organic carriers (Shirokova et al., 2013). Increasing marine heat waves may further disturb these chemical systems, potentially changing both toxicity and how readily organisms absorb REEs (León-FonFay et al., 2025).

Wildlife response to REE

Freshwater zooplankton serve as sensitive indicators, with tissue REE levels accurately reflecting environmental availability (MacMillan et al., 2019). Arctic char in Greenland accumulates REEs in the gills and liver but can excrete them relatively quickly when moved to clean water (Nørregaard et al., Reference Nørregaard, Kaarsholm, Bach, Nowak, Geertz-Hansen, Søndergaard and Sonne2019). Current REE levels do not yet cause significant tissue damage, providing an important benchmark for evaluating future mining impacts (Nørregaard et al., Reference Nørregaard, Bach, Geertz-Hansen, Nabe-Nielsen, Nowak, Jantawongsri and Sonne2022).

Microbes and human health

Certain fungi living in mining waste on Russia’s Kola Peninsula not only tolerate REEs but also grow better at low concentrations, suggesting potential for cleanup strategies (Kasatkina et al., 2023a, 2023b). However, industrial contamination is evident in the Russian part of the Arctic, where wastewater has enriched mountain lake sediments with REEs beyond their natural levels (Dauvalter et al., Reference Dauvalter, Slukovskii, Denisov and Guzeva2022; Slukovskii et al., 2025). Risk assessments for the proposed Canadian mines warn that subarctic conditions could increase occupational and community exposure through inhalation or ingestion of REE-laden dust (Yin et al., Reference Yin, Martineau, Demers, Basiliko and Fenton2021).

Geopolitics, governance, and social conflict

Geopolitics and resource competition

Climate change has transformed the Arctic into a “global arena” where intensified geopolitical competition over strategic resources unfolds (Finger & Rekvig, 2022). Retreating sea ice has fundamentally altered the region’s accessibility, opening new maritime routes and exposing vast mineral deposits, including REEs, which are now viewed through the lens of national security and economic sovereignty (Bert, 2012; Burger, 2012). This shift has created a “metals dilemma”—the global imperative for a green energy transition drives a scramble for critical minerals, positioning the Arctic at the center of US-China strategic rivalry (Howie, 2011; Kravchuk, 2023).

In Greenland, this dynamic is particularly acute; the island’s geostrategic location and substantial REE reserves have attracted significant attention from major powers, with the US and China competing for influence over its resources (Salvador, 2025). The Russian Federation has prioritized the development of its Arctic zone to mitigate import dependence, viewing projects such as the Tomtor niobium-rare earth deposit as essential for revitalizing its high-tech industries and ensuring energy security (Dmitrieva & Solovyova, Reference Dmitrieva and Solovyova2023; Jier & Boyarko, 2025). This politicization of Arctic resources suggests that future development will be driven as much by state-level strategic interests as by market forces (Peimani, 2013).

Infrastructure and governance gaps

The transition from exploration to extraction in the Arctic has been constrained by severe infrastructural deficits and complex governance frameworks. The lack of transportation networks in remote regions has necessitated proposals for novel logistical solutions, such as the deployment of cargo airships for service mining operations, which could offer a more environmentally viable alternative to road construction (Prentice et al., 2021). The economic assessment of these projects requires sophisticated methodologies; recent studies advocate the integration of digital technologies and scenario modeling to better evaluate investment risks in the harsh Arctic environment (Lukichev et al., 2022).

Governance structures are also under strain, particularly in terms of transparency and public participation. In Greenland, the political pursuit of independence from Denmark is deeply intertwined with the mining sector, creating tension between the desire for economic autonomy funded by resource rents and the necessity to maintain rigorous environmental standards (Hall, 2021). Analyses of the legal frameworks governing projects such as Kvanefjeld indicate that the drive for sovereignty may impact decision-making transparency, limiting public access to critical environmental impact assessments (Pelaudeix et al., 2017).

Indigenous rights and social conflict

In the Russian Arctic, mining projects frequently overlap with Traditional Nature Management Territories, leading to conflicts where the macroeconomic goals of the state clash with the subsistence livelihoods of Indigenous peoples (Novoselov et al., Reference Novoselov, Potravnii, Novoselova and Gassiy2016). In the Russian Arctic, the expansion of industrial activities into these territories has raised urgent concerns regarding the adequacy of damage compensation mechanisms, which often fail to account for the holistic loss of cultural and economic resources (Burtseva & Bysyina, 2019; Romanova & Romanov, 2020).

The concept of “ecologically unequal exchange” has been applied to Greenland to argue that the island risks becoming a resource periphery, bearing the local environmental costs of extraction to support the decarbonization of industrialized nations (Henriques & Böhm, Reference Henriques and Böhm2022). To mitigate these conflicts, researchers emphasize the necessity of integrating ethnological expertise into project planning and adopting route selection criteria that explicitly minimize impacts on traditional lands (Novoselov et al., 2017; Potravny et al., Reference Potravny, Novoselov, Novoselova, Chávez Ferreyra and Gassiy2022). Without robust conflict management strategies that prioritize Indigenous self-determination, the “social license to operate” will remain the primary bottleneck for Arctic REE development (Sivtseva et al., 2020).

Analysis of media discourse related to REEs in the Arctic

Media discourse surrounding REEs in the Arctic has evolved significantly over the past few years, reflecting growing anxieties regarding climate change, green energy transition, and geopolitical competition.

Geopolitical competition

The discourse evolved from speculative economic optimism in the early 2010s to urgent national security imperatives by 2025. The United Kingdom’s 2025 defense review explicitly argues for an expanded military footprint in the High North, citing the opening of shipping routes and the accessibility of oil, gas, and REEs as drivers of rivalry among the US, Russia, and China (Fisher et al., 2025). Russia has reopened dozens of Soviet-era military bases, while China has aggressively pursued the “Polar Silk Road” to exploit Greenland’s natural resources (Kantchev, Reference Kantchev2025). The Western imperative to diversify supply chains away from Chinese dominance, which controls over 70% of REE mining and almost 90% of the conversion into magnets, has become a strategic necessity (Meichtry & Hinshaw, Reference Meichtry and Hinshaw2021). Donald Trump’s reiterated ambition to purchase Greenland positioned the island as a “focal point for major rival powers,” fundamentally altering the security landscape in the North Atlantic (Kantchev, 2025).

Broader concerns about unregulated resource extraction and environmental damage have dominated discussions, with anxieties surrounding a potential “free-for-all” scenario in the melting Arctic due to geopolitical competition (Milne & Nordic, Reference Milne and Nordic2023). The 2023 discovery of a 1 million ton REE deposit in Sweden by LKAB was met with skepticism regarding its true potential, and Sami reindeer herders expressed concerns about its impacts on their land (Fleming & Milne, Reference Fleming and Milne2023; Milne, Reference Milne2023). Lengthy permitting processes and potential energy constraints further complicate Europe’s capacity to refine mined REEs (Milne, Reference Milne2023; Fleming & Milne, Reference Milne2023). Canada granted Nunavut control over its mineral resources, including REEs, highlighting the potential for increased access to critical resources and economic empowerment for Arctic territories (Indigenous Affairs, 2024).

Russian technological sovereignty

Sources from 2025 indicate a concerted state-led push for Russia to become a global leader in REE production by 2030, capitalizing on a projected global deficit (“Russia: Russia may become leader,” 2025). This ambition is codified in federal initiatives, such as the “Geology: Legend Rebirth” project, which prioritizes the creation of processing industries in the Arctic (“Russia: Russia may become leader,” 2025). The discourse has shifted dramatically from theoretical aspirations to immediate execution. In 2017, the Tomtor deposit was described in futuristic terms as a “storehouse for missions to Mars and super engines,” reflecting long-term technological ambitions (“Russia: Russia’s Tomtor,” 2017). By 2025, the discourse emphasizes “technological sovereignty” and the immediate construction of full-cycle production facilities to secure Russia’s position against Western sanctions (“Russia: Rare earth metals projects,” 2025). Specific infrastructure projects are central to this strategy. The Murmansk Region is identified as a key hub for creating full-cycle facilities involving lithium and perovskite-titanomagnetite ores (“Russia: Rare earth metals projects,” 2025). The development of the Tomtorskoye (Tomor) deposit in Yakutia is projected to facilitate the creation of an entirely new industrial district in the Arctic, comparable to the Norilsk industrial cluster (“Russia: Development of rare earth metals,” 2025). The Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF) has explicitly discussed investing in Arctic REE projects to support this strategic expansion (“Russia: Russia mulls projects,” 2025).

The Greenland sovereignty

By 2019, Greenland had emerged as a potential “Saudi Arabia of the green future” (Clare, Reference Clare2019; Dempsey, Reference Dempsey2019). However, this path is fraught with structural barriers and internal opposition. Industry analysts cautioned that Greenland’s projects remained constrained by China’s “complex technology” for processing and its control over the market (Dempsey, Reference Dempsey2019). The reliance of Greenland Minerals on a Chinese company (Shenghe) for processing the Kvanefjeld deposit underscores this dependence (Meichtry & Hinshaw, Reference Meichtry and Hinshaw2021).

The 2021 election victory of the left-wing Inuit Ataqatigiit (IA) party was widely interpreted as a mandate against “dirty mining,” specifically the Kvanefjeld REE project, due to concerns over radioactive uranium by-products. Bureaucracy and inexperience are cited as major hurdles, with mining companies complaining that excessive governmental caution has stalled development (Dempsey, Reference Dempsey2019). The political volatility introduced by external actors exacerbates these challenges. The Greenlandic Mining Minister warned in 2025 that the “Trump effect”—characterized by aggressive overtures to buy the island—risked “spooking investors” and creating fear of a land grab rather than fostering stable investment partnerships (Ivanova & Milne, 2025; Kantchev, 2025). The renewed US interest in purchasing Greenland is no longer dismissed as a “fantasy” but is now seen as a destabilizing geopolitical maneuver that necessitates immediate diplomatic and economic responses (Ivanova et al., 2025; Kantchev, 2025). Greenland requires significant foreign investment and assistance to unlock its potential, however, it remains caught between its desire for autonomy and the geopolitical strategies of major powers (Milne, 2025).This dynamic is reflected in the March 2024 EU-Greenland Memorandum of Understanding for a strategic partnership aimed at fostering sustainable raw-material value chains, aligning with the EU’s Global Gateway strategy to secure a reliable supply chain (European Commission, Reference Commission2023).

Discussion

By employing discourse analysis, this study reveals how resource control is articulated within broader geopolitical projects, thereby exposing the interplay between material realities and symbolic constructions (Huber, Reference Huber2015). A comparative longitudinal analysis from 2010 to 2025 reveals a distinct evolution in Arctic REE discourse. Scientific discourse reflects this reconfiguration, moving from static geological baselines to dynamic assessments of how climate change mobilizes pollutants (Astakhov et al., 2019; León-FonFay et al., 2025). Environmental concerns include pollution, metal leaching, and impacts on living organisms, with REEs traveling through air and water, potentially posing ecosystem and human risks (Dauvalter et al., Reference Dauvalter, Slukovskii, Denisov and Guzeva2022). This transition from hydrocarbon dependence to critical minerals encapsulates broader geopolitical reconfiguration, foregrounding enduring questions of power and identity as states negotiate sustainable development pathways (Gökçe, Reference Gökçe2024; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li-mao, Zhong, Xiang and Qu2023).

Media discourse has shifted dramatically from economic optimism to securitization. Media publications from 2014 to 2023 depicted the region as a technological frontier, characterizing deposits such as Russia’s Tomtor as futuristic opportunities (Milne, 2019; Russia: Russia’s Tomtor, 2017). As the “metals dilemma” intensified, when green energy transition drove a scramble for critical minerals (including REEs), discourse pivoted to frame Western reliance on Chinese supply chains as a national security crisis (Howie, 2011; Paulick & Faigen, 2017; Meichtry & Hinshaw, Reference Meichtry and Hinshaw2021). By 2025, this had exploded with record-high publication numbers on REE geopolitics in the Arctic.

Russia’s discourse constructs “technological sovereignty,” justifying full-cycle REE production as the restoration of great power status rather than pure industrial policy (Lazhentsev, Reference Lazhentsev2024; Russia: Russia may become leader, 2025). By 2025, emphasis shifted to immediate construction of production facilities to counter Western sanctions, codified in initiatives like the “Geology: Legend Rebirth” project (“Russia: Rare earth metals projects,” 2025).

Discourses surrounding renewable energy recalibrate alliances during conflict periods, exemplified by the Russian-Ukrainian war and the EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act (2023), pushing for strategic autonomy (Madubuko, Reference Madubuko2024). National Arctic strategies demonstrate the growing recognition of REEs as critical for the global energy transition. The EU has emerged as a leader, where the Critical Raw Materials Act (2023) commits to securing domestic supply chains through investments estimated at billions of euros by 2040, addressing dependence on Chinese suppliers (Critical Raw Materials Act, 2023; Hammond, 2024). The 2024 EU-Greenland Memorandum of Understanding for sustainable raw-material value chains reflects this strategic reorientation (European Union, 2024).

The green transition paradox

The “green transition” theme, heavily present in the discourse, creates complex friction. While the EU frames Arctic resources as essential for climate neutrality, Greenlandic discourse increasingly challenges this through “ecologically unequal exchange,” arguing the island risks becoming a sacrifice zone for industrialized decarbonization (Henriques & Böhm, Reference Henriques and Böhm2022). Greenland’s quest for independence is closely linked to its “mineral bounty,” yet it faces obstacles from external geopolitical maneuvers. The “Trump effect” has recast investment potential as a destabilizing “land grab” (Ivanova, 2025; Kantchev, 2025).

Critical gaps and future directions

Despite the expanding literature, significant gaps remain. Discourse contains limited discussion on specific social impacts on Indigenous communities beyond general concerns, lacking concrete avenues for meaningful participation in project governance. Indigenous communities raise concerns about environmental degradation and disruption of traditional livelihoods, yet the current discourse often obscures their voices (Milne, 2025). Additionally, topics pertaining to innovation and Arctic-specific R&D in extraction technologies are absent. While “geopolitical tensions” are frequently cited, detailed critical geopolitical studies and security considerations are often missing from broader public discourse.

Lifecycle sustainability assessments must integrate geopolitical considerations alongside geological models, emphasizing multi-layered discourse analysis attentive to power relations, historical trajectories, and political imaginaries (Gemechu et al., Reference Gemechu, Helbig, Sonnemann, Thorenz and Tuma2015; Karadoğan & Kuzucuoğlu, Reference Karadoğan and Kuzucuoğlu2022). A nuanced understanding demands the integration of overlooked themes, prioritizing models for effective Indigenous engagement and comprehensive impact analyses accounting for the full spectrum of economic, environmental, and social implications.

Conclusions

REEs are critical for both green energy technologies and defense systems, and China’s market dominance has prompted urgent efforts to diversify supply chains, including Arctic exploration (Meichtry & Hinshaw, Reference Meichtry and Hinshaw2021). Receding ice, resource security imperatives, and intensifying geopolitical competition have positioned the Arctic as a strategic frontier for REE development (Finger & Rekvig, 2022; Fisher et al., 2025).

However, a comprehensive discourse analysis revealed significant gaps. Current discussions lack adequate attention to specific social impacts on Indigenous communities, concrete mechanisms for their meaningful participation in governance, Arctic-specific innovation and R&D in extraction technologies, and detailed critical geopolitical and security assessments. Indigenous concerns about environmental degradation and disruption of traditional livelihoods remain inadequately addressed in high-level strategic discourse (Milne, 2025; Novoselov et al., Reference Novoselov, Potravnii, Novoselova and Gassiy2016).

The 2024 EU-Greenland partnership for sustainable raw materials signals a strategic reorientation toward responsible supply chain development amid current geopolitical realities (European Union, 2024). However, this transition must be supported by thorough scientific research on the feasibility and implications of extraction. Any development of REEs in the Arctic should emphasize active collaboration with local communities, comprehensive impact assessments that consider economic, environmental, and social factors, and effective conflict management strategies that prioritize Indigenous self-determination (Gemechu et al., Reference Gemechu, Helbig, Sonnemann, Thorenz and Tuma2015; Sivtseva et al., 2020).

As the Arctic emerges as a potential REE source, lifecycle sustainability assessments must integrate geopolitical considerations with environmental baselines, ensuring that the pursuit of critical minerals does not transform the region into a resource periphery that bears the costs of global decarbonization (Henriques & Böhm, Reference Henriques and Böhm2022). This study underscores the necessity for advancing the field toward more interdisciplinary and actionable frameworks, emphasizing the importance of integrated sustainability assessments. Securing community acceptance is critical for responsible Arctic REE development and requires addressing these gaps through comprehensive research and inclusive strategies.

Appendix A

Astakhov, A. S., Sattarova, V. V., Xuefa, S., Hu, L., Aksentov, K. I., Alatortsev, A. V., Kolesnik, O. N., & Mariash, A. A. (2019). Distribution and sources of rare earth elements in sediments of the Chukchi and East Siberian Seas. Polar Science, 20, 148–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polar.2019.05.005

Bazzano, A., Ardini, F., Grotti, M., Malandrino, M., Giacomino, A., Abollino, O., Cappelletti, D. M., Becagli, S., Traversi, R., & Udisti, R. (2016). Elemental and lead isotopic composition of atmospheric particulate measured in the Arctic region (Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard Islands). Rendiconti Lincei, 27, 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12210-016-0507-9

Bert, M. (2012). The arctic is now: Economic and national security in the last Frontier. American Foreign Policy Interests, 34(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/10803920.2012.653940

Borovichev, E. A., Kozhin, M. N., Akhmerova, D. R., Koroleva, N. E., & Petrova, O. V. (2021). Protected species of vascular plants in Khibiny Montains: How many representative herbar collections? InterCarto, InterGIS, 27, 230–241. https://doi.org/10.35595/2414-9179-2021-3-27-230-241

Burger, M. (2012). The last, last frontier. In K. H. Hirokawa (Ed.), (pp. 303–332). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139519762.016

Burtseva, E., & Bysyina, A. (2019). Damage compensation for indigenous peoples in the conditions of industrial development of territories on the example of the arctic zone of the Sakha Republic. Resources, 8(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources8010055

Butler, D. H., & Dawson, P. C. (2018). Untangling natural and anthropogenic multi-element signatures in archaeological soils at the Ikirahak site, Arctic Canada. Boreas, 47(1), 189–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/bor.12258

Chen, S.-C., Musat, F., Richnow, H.-H., & Krüger, M. C. (2024). Microbial diversity and oil biodegradation potential of northern Barents Sea sediments. Journal of Environmental Sciences (China), 146, 283–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2023.12.010

Conca, E., Abollino, O., Giacomino, A., Buoso, S., Traversi, R., Becagli, S., Grotti, M., & Malandrino, M. (2019). Source identification and temporal evolution of trace elements in PM10 collected near to Ny-Ålesund (Norwegian Arctic). Atmospheric Environment, 203, 153–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2019.02.001

Costis, S., Coudert, L., Mueller, K. K., Cecchi, E., Neculita, C. M., & Blais, J.-F. (2020). Assessment of the leaching potential of flotation tailings from rare earth mineral extraction in cold climates. Science of the Total Environment, 732, 139225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139225

Cui, Y., Liu, X., Liu, C., Gao, J., Fang, X., Liu, Y., Wang, W., & Li, Y. S. (2020). Mineralogy and geochemistry of ferromanganese oxide deposits from the Chukchi Sea in the Arctic Ocean. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, 52(1), 120–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/15230430.2020.1738824

Dauvalter, V. A., Slukovsky, Z. I., & Denisov, D. B. (2023). The chemical composition of water and sediments of an Arctic mountain lake in the zone of influence of sewage of apatite-nepheline production. Springer Proceedings in Earth and Environmental Sciences, 453–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-23390-6_57

Dauvalter, V. A., Slukovskii, Z. I., Denisov, D. B., & Guzeva, A. V. (2022). A Paleolimnological Perspective on Arctic Mountain Lake Pollution. Water (Switzerland), 14(24), 4044. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14244044

Desjardins, É., Lai, S., Payette, S., Vézina, F., Tam, A., & Berteaux, D. (2021). Vascular Plant Communities in the Polar Desert of Alert (Ellesmere Island, Canada): Establishment of a Baseline Reference for the 21st Century. Ecoscience, 28(3-4), 243–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2021.1907974

Dinu, M. I., Shkinev, V. M., Moiseenko, T. I., Dzhenloda, R. K., & Danilova, T. V. (2020). Quantification and speciation of trace metals under pollution impact: Case study of a subarctic lake. Water (Switzerland), 12(6), 1641. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12061641

Dmitrieva, D., & Solovyova, V. M. (2023). Russian Arctic Mineral Resources Sustainable Development in the Context of Energy Transition, ESG Agenda and Geopolitical Tensions. Energies, 16(13), 5145. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16135145

Du, Z., Xiao, C., Zhang, Q., Handley, M. J., Mayewski, P. A., & Li, C. (2019). Relationship between the 2014–2015 Holuhraun eruption and the iron record in the East GRIP snow pit. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, 51(1), 290–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/15230430.2019.1634441

Dumoulin, J. A., Slack, J. F., Whalen, M. T., & Harris, A. G. (2011). Depositional setting and geochemistry of phosphorites and metalliferous black shales in the Carboniferous-Permian Lisburne Group, northern Alaska. US Geological Survey Professional Paper, (1776 C), 1–30.

Faigen, E., & Kalvig, P. (2016). Assessing advanced rare earth element-bearing deposits for industrial demand in the EU. Resources Policy, 49, 186–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2016.05.004

Fan, M., Xu, J., Chen, Y., & Li, W. (2020). Simulating the precipitation in the data-scarce Tianshan Mountains, Northwest China based on the Earth system data products. Arabian Journal of Geosciences, 13(14), 637. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-020-05509-1

Feria-Tinta, M., & Kamga, M. K. (2024). Mining the bottom of the sea: Potential future disputes and the role of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea. In V. T. Campanella (Ed.), (pp. 239–256). https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429426162-20

Ferrero, L., Sangiorgi, G., Perrone, M. G., Rizzi, C., Cataldi, M., Markuszewski, P., Pakszys, P., Makuch, P., Petelski, T., Becagli, S., Traversi, R., Bolzacchini, E., & Zielinski, T. P. (2019). Chemical composition of aerosol over the Arctic ocean from summer Arctic expedition (AREX) 2011-2012 cruises: Ions, amines, elemental carbon, organic matter, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, n-alkanes, metals, and rare earth elements. Atmosphere, 10(2), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos10020054

Finger, M. P., & Rekvig, G. (2022). Global Arctic: An introduction to the multifaceted dynamics of the Arctic. Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

Giardi, F., Traversi, R., Becagli, S., Severi, M., Caiazzo, L., Ancillotti, C., & Udisti, R. (2018). Determination of Rare Earth Elements in multi-year high-resolution Arctic aerosol record by double focusing Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry with desolvation nebulizer inlet system. Science of the Total Environment, 613-614, 1284–1294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.247

Giesse, C., Notz, D., & Baehr, J. (2024). The shifting distribution of Arctic daily temperatures under global warming. Earth’s Future, 12(11), e2024EF004961. https://doi.org/10.1029/2024EF004961

Goodarzi, F., Goodarzi, N. N., & Małachowska, A. (2021). Elemental composition, environment of deposition of the lower Carboniferous Emma Fiord formation oil shale in Arctic Canada. International Journal of Coal Geology, 244, 103715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2021.103715

Goryunova, V. O., Prokopyev, I. R., Doroshkevich, A. G., Starikova, A. E., Proskurnin, V. F., & Saltanov, V. A. (2024). Rare earth composition of fluorites as an indicator of the origin of carbonatites of Central Tuva and Eastern Taimyr. Geosfernye Issledovaniya, 2024(3), 10–20. https://doi.org/10.17223/25421379/32/2

Graly, J. A., Corbett, L. B., Bierman, P. R., Lini, A., & Neumann, T. A. (2018). Meteoric 10Be as a tracer of subglacial processes and interglacial surface exposure in Greenland. Quaternary Science Reviews, 191, 118–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.05.009

Grégoire, M., Chevet, J., & Maaloe, S. (2010). Composite xenoliths from Spitsbergen: Evidence of the circulation of MORB-related melts within the upper mantle. Geological Society Special Publication, 337, 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP337.4

Hall, D. (2021). Tourism, climate change and the geopolitics of Arctic development: The critical case of Greenland. CABI. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781789246728.0000

Henriques, I., & Böhm, S. (2022). The perils of ecologically unequal exchange: Contesting rare-earth mining in Greenland. Journal of Cleaner Production, 349, 131378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131378

Howie, A. (2011). Metals dilemma for west. Sustainable Business, (177), 36–37.

Huang, Y., Taylor, P. C., Rose, F. G., Rutan, D. A., Shupe, M. D., Webster, M. A., & Smith, M. M. (2022). Toward a more realistic representation of surface albedo in NASA CERES-derived surface radiative fluxes: A comparison with the MOSAiC field campaign. Elementa, 10(1), 00013. https://doi.org/10.1525/elementa.2022.00013

II International Scientific and Practical Conference “Ensuring Sustainable Development in Thecontext of Agriculture, Green Energy, Ecology and Earth Science.” (2022). IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1045(1).

Jessen, S., Holmslykke, H. D. H., Rasmussen, K., Richardt, N., & Holm, P. E. (2014). Hydrology and pore water chemistry in a permafrost wetland, ilulissat, Greenland. Water Resources Research, 50(6), 4760–4774. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013WR014376

Jier, Z., & Boyarko, G. Y. (2025). Development problems and prospects of the Tomtor Niobium-Rare Earth Deposit in the Arctic Zone of Russia: Ecological and economic aspects. Arktika: Ekologia i Ekonomika, 15(2), 226–237. https://doi.org/10.25283/2223-4594-2025-2-226-237

Kaplunov, D. R., & Yukov, V. A. (2018). Accounting for regional features of mineral-resources base in re-equipment of underground mines. Mining Informational and Analytical Bulletin, 2018(9), 25–34. https://doi.org/10.25018/0236-1493-2018-9-0-25-34

Kasatkina, E. A., Shumilov, O. I., Kirtsideli, I. Y., & Makarov, D. V. (2023a). Bioleaching potential of microfungi isolated from Arctic loparite ore tailings (Kola Peninsula, Northwestern Russia). Geomicrobiology Journal, 40(3), 285–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490451.2022.2162166

Kasatkina, E. A., Shumilov, O. I., Kirtsideli, I. Y., & Makarov, D. V. (2023b). Hormesis and low toxic effects of three lanthanides in microfungi isolated from rare earth mining waste in Northwestern Russia. Toxics, 11(12), 1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics11121010

Kompanchenko, A. A., & Neradovsky, Y. N. (2019). Vanadium in the Arctic zone of Russia on the Kola region example: Prevalence, sources, industrial potential. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 302(1), 012045. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/302/1/012045

Kravchuk, A. A. (2023). Prospects for Greenland’s economic autonomy. Sovremennaya Evropa, 2023(1), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.31857/S0201708323010096

Kumar, P., Pattanaik, J. K., Khare, N., & Balakrishnan, S. (2018). Geochemistry and provenance study of sediments from Krossfjorden and Kongsfjorden, Svalbard (Arctic Ocean). Polar Science, 18, 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polar.2018.06.001

Lai, A. M., Shafer, M. M., Dibb, J. E., Polashenski, C. M., & Schauer, J. J. (2017). Elements and inorganic ions as source tracers in recent Greenland snow. Atmospheric Environment, 164, 205–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2017.05.048

Laukert, G., Peeken, I., Bauch, D., Krumpen, T., Hathorne, E. C., Werner, K., Gutjahr, M., & Frank, M. (2022). Neodymium isotopes trace marine provenance of Arctic sea ice. Geochemical Perspectives Letters, 22, 10–15. https://doi.org/10.7185/geochemlet.2220

Layus, P., Kah, P., Parshin, S. G., Dmitriev, V., & Mvola, B. (2018). Study of welding wire nanocoated with lanthanum boride for S960 high-strength steel welding. Proceedings of the International Offshore and Polar Engineering Conference, 2018-June, 146–153.

Lazhentsev, V. N. (2021). The Arctic and the North: A Russian spatial development context. Economy of Regions, 17(3), 737–754. https://doi.org/10.17059/EKON.REG.2021-3-2

Lazhentsev, V. N. (2024). Changes in the mineral resources economy of the Russian North. Studies on Russian Economic Development, 35(1), 144–149. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1075700724010088

Lenaerts, J. T. M., Drew Camron, M., Wyburn-Powell, C. R., & Kay, J. E. (2020). Present-day and future Greenland Ice Sheet precipitation frequency from CloudSat observations and the Community Earth System Model. Cryosphere, 14(7), 2253–2265. https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-14-2253-2020

León-FonFay, D., Barkhordarian, A., Feser, F., & Baehr, J. (2025). Sensitivity of Arctic marine heatwaves to half-a-degree increase in global warming: 10-fold frequency increase and 15-fold extreme intensity likelihood. Environmental Research Letters, 20(1), 014049. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ada029

Lobanov, K. V., Grigorieva, A. V., Volkov, A. V., Chicherov, M. V., & Murashov, K. Y. (2021). Less-common and rare earth elements of the pechenga region ores. Arktika: Ekologia i Ekonomika, 11(3), 406–421. https://doi.org/10.25283/2223-4594-2021-3-406-421

Lobus, N. V., Arashkevich, E. G., & Flerova, E. A. (2019). Major, trace, and rare-earth elements in the zooplankton of the Laptev Sea in relation to community composition. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 26(22), 23044–23060. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-05538-8

Lukichev, S. V., Nagovitsyn, O. V., Churkin, O., & Giliarova, A. A. (2022). Application of digital technologies for investment evaluation of mining projects in the western part of the Arctic. Arktika: Ekologia i Ekonomika, 12(4), 524–537. https://doi.org/10.25283/2223-4594-2022-4-524-537

MacMillan, G. A., Chételat, J., Heath, J. P., Mickpegak, R., & Amyot, M. (2017). Rare earth elements in freshwater, marine, and terrestrial ecosystems in the eastern Canadian Arctic. Environmental Science: Processes and Impacts, 19(10), 1336–1345. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7em00082k

MacMillan, G. A., Clayden, M. G., Chételat, J., Richardson, M. C., Ponton, D. E., Perron, T., & Amyot, M. (2019). Environmental drivers of rare earth element bioaccumulation in freshwater zooplankton. Environmental Science & Technology, 53(3), 1650–1660. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b05547

Makryi, T. V. (2024). Enchylium substellatum, a new lichen species for Russia. Turczaninowia, 27(2), 46–51. https://doi.org/10.14258/turczaninowia.27.2.6

Manasypov, R. M., Pokrovsky, O. S., Shirokova, L. S., Auda, Y., Zinner, N. S., Vorobyov, S. N., & Kirpotin, S. N. (2021). Biogeochemistry of macrophytes, sediments and porewaters in thermokarst lakes of permafrost peatlands, western Siberia. Science of the Total Environment, 763, 144201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144201

Marginson, H., MacMillan, G. A., Wauthy, M., Sicaud, E., Gérin-Lajoie, J., Dedieu, J.-P., & Amyot, M. (2024). Drivers of rare earth elements (REEs) and radionuclides in changing subarctic (Nunavik, Canada) surface waters near a mining project. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 471, 134418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.134418

Masloboev, V. A., Klyuchnikova, E. M., & Makarov, D. V. (2021). Sustainable development of the mining complex of the Murmansk region: Minimization of man-made impacts on the environment. Sustainable Development of Mountain Territories, 13(2), 188–200. https://doi.org/10.21177/1998-4502-2021-13-2-188-200

Maysyuk, E. P., & Ivanova, I. Y. (2020). Environmental assessment of different fuel types for energy production in the arctic regions of the Russian Far East. Arktika: Ekologia i Ekonomika, 37(1), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.25283/2223-4594-2020-1-26-36

Middleton, M., Torppa, J., Wäli, P. R., & Sutinen, R. (2018). Biogeochemical anomaly response of circumboreal shrubs and juniper to the Juomasuo hydrothermal Au-Co deposit in northern Finland. Applied Geochemistry, 98, 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2018.09.006

Morozov, A. N., Vaganova, N. V., Asming, V. E., Peretokin, S. A., & Aleshin, I. M. (2023). Seismicity of the Western Sector of the Russian Arctic. Izvestiya, Physics of the Solid Earth, 59(2), 209–241. https://doi.org/10.1134/S106935132302009X

Nørregaard, R. D., Bach, L., Geertz-Hansen, O., Nabe-Nielsen, J., Nowak, B., Jantawongsri, K., Dang, M., Søndergaard, J., Leifsson, P. S., Jenssen, B. M., Ciesielski, T. M., Arukwe, A., & Sonne, C. (2022). Element concentrations, histology and serum biochemistry of arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus) and shorthorn sculpins (Myoxocephalus scorpius) in northwest Greenland. Environmental Research, 208, 112742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.112742

Nørregaard, R. D., Kaarsholm, H. M., Bach, L., Nowak, B. F., Geertz-Hansen, O., Søndergaard, J., & Sonne, C. (2019). Bioaccumulation of rare earth elements in juvenile arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus) under field experimental conditions. Science of the Total Environment, 688, 529–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.06.180

Novoselov, A. L., Potravny, I. M., Novoselova, I. Y., & Gassiy, V. (2016). Conflicts management in natural resources use and environment protection on the regional level. Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism, 7(3), 407–415. https://doi.org/10.14505/jemt.v7.3(15).06

Novoselov, A. L., Potravny, I. M., Novoselova, I. Y., & Gassiy, V. (2017). Selection of priority investment projects for the development of the Russian Arctic. Polar Science, 14, 68–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polar.2017.10.003

Novoselov, A., Potravny, I. M., Novoselova, I., Chávez Ferreyra, K. Y., & Gassiy, V. (2022). Route Selection for Minerals’ Transportation to Ensure Sustainability of the Arctic. Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(23), 16039. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316039

Ohmura, A. (2012). Present status and variations in the Arctic energy balance. Polar Science, 6(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polar.2012.03.003

Oleinikova, O. V., Shirokova, L. S., Drozdova, O. Y., Lapitskiy, S. A., & Pokrovsky, O. S. (2018). Low biodegradability of dissolved organic matter and trace metals from subarctic waters. Science of the Total Environment, 618, 174–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.10.340

Parker, R. L., Foster, G. L., Gutjahr, M., Wilson, P. A., Littler, K. L., Cooper, M. J., Michalik, A., Milton, J. A., Crocket, K. C., & Bailey, I. (2022). Laurentide Ice Sheet extent over the last 130 thousand years traced by the Pb isotope signature of weathering inputs to the Labrador Sea. Quaternary Science Reviews, 287, 107564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2022.107564

Paulick, H., & Faigen, E. (2017). The global rare earth element exploration boom: An analysis of resources outside of China and discussion of development perspectives. Resources Policy, 52, 134–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2017.02.002

Peimani, H. (2013). Energy security and geopolitics in the Arctic: Challenges and opportunities in the 21st century. World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.

Pelaudeix, C., Basse, E. M., & Loukacheva, N. V. (2017). Openness, transparency and public participation in the governance of uranium mining in Greenland: A legal and political track record. Polar Record, 53(6), 603–616. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247417000596

Potravny, I. M., Yashalova, N. N., Novikov, A. V., & Zhao, J. (2024). Use of rare earth metals in renewable energy: Opportunities and risks. Ecology and Industry of Russia, 28(1), 11–15. https://doi.org/10.18412/1816-0395-2024-1-11-15

Prentice, B. E., Lau, Y. Y., & Ng, A. K. Y. (2021). Transport airships for scheduled supply and emergency response in the arctic. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(9), 5301. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095301

Rabbi, S. F., Sarker, M. M., Rideout, G., Stephen Douglas Butt, S. D., & Rahman, M. A. (2015). Analysis of a hysteresis IPM motor drive for electric submersible pumps in harsh Atlantic offshore environments. Proceedings of the International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering - OMAE, 10. https://doi.org/10.1115/OMAE2015-41955

Rashid, A., Fang, C., Qin, D., Zhang, Y., Nkinahamira, F., Bo, J., & Sun, Q. (2023). Spatiotemporal profile and ecological impacts of major and trace elements in surface sediments of marginal seas of the Arctic and Northern Pacific Oceans. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 197, 115702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2023.115702

Romanova, O. D., & Romanov, P. G. (2020). Strategy for the sustainable development of indigenous peoples of the Arctic: Problems and prospects in the context of new industrial development. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 539(1), 012182. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/539/1/012182

Salvador, A. M. (2025). United States interests and Greenland’s dilemmas. Revista Electronica de Estudios Internacionales, (49), 393–417. https://doi.org/10.36151/reei.49.13

Saneev, B. G., Ivanova, I. Y., & Korneev, A. G. (2020). Assessment of electrical loads of potential projects for the development of mineral resources in the eastern regions of the Arctic Zone of the Russian federation. Arktika: Ekologia i Ekonomika, 37(1), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.25283/2223-4594-2020-1-4-14

Sattarova, V. V., Aksentov, K. I., Kirichenko, I. S., Yaroshchuk, E. I., Charkin, A. N., Zarubina, N. V., & Miroshnichenko, L. V. (2025). Ferromanganese formations of the Chaunskaya Bay (East Siberian Sea): Geochemistry and mineralogy. Geo-Marine Letters, 45(2), 23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00367-025-00813-9

Savenko, A. V., & Savenko, V. S. (2024). Trace Element Composition of the Dissolved Matter Runoff of the Russian Arctic Rivers. Water (Switzerland), 16(4), 565. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16040565

Semenov, V. A., & Latif, M. (2015). Nonlinear winter atmospheric circulation response to Arctic sea ice concentration anomalies for different periods during 1966-2012. Environmental Research Letters, 10(5), 054020. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/10/5/054020

Senzaki, M., Tamura, K., Watanabe, Y., Watanabe, M., & Sato, T. (2024). Rare bird forecast: A combined approach using a long-term dataset of an Arctic seabird and a numerical weather prediction model. Ecology and Evolution, 14(6), e11388. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.11388

Shestak, O. I., Shcheka, O. L., & Klochkov, Y. S. (2020). Methodological aspects of use of countries experience in determining the directions of the strategic development of the Russian Federation arctic regions. International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management, 11, 44–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13198-019-00805-w

Shirokova, L. S., Bredoire, R., Rols, J.-L., & Pokrovsky, O. S. (2017). Moss and peat leachate degradability by heterotrophic bacteria: The fate of organic carbon and trace metals. Geomicrobiology Journal, 34(8), 641–655. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490451.2015.1111470

Shirokova, L. S., Chupakova, A. A., Chupakov, A. V., & Pokrovsky, O. S. (2017). Transformation of dissolved organic matter and related trace elements in the mouth zone of the largest European arctic river: Experimental modeling. Inland Waters, 7(3), 272–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/20442041.2017.1329907

Shirokova, L. S., Pokrovsky, O. S., Moreva, O. Y., Chupakov, A. V., Zabelina, S. A., Klimov, S. I., Shorina, N. V., & Vorobieva, T. Y. (2013). Decrease of concentration and colloidal fraction of organic carbon and trace elements in response to the anomalously hot summer 2010 in a humic boreal lake. Science of the Total Environment, 463-464, 78–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.05.088

Shulkin, V. M., Davydov, S. P., Davydova, A. I., Lutsenko, T. N., & Elovskiy, E. V. (2025). Scale and Reasons for Changes in Chemical Composition of Waters During the Spring Freshet on Kolyma River, Arctic Siberia. Water (Switzerland), 17(16), 2400. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17162400

Sivtseva, A. I., Sivtseva, E. N., Shadrina, S. S., Melnikov, V. N., Boyakova, S. I., & Dokhunaeva, A. M. (2020). Microelement composition of serum in Dolgans, indigenous inhabitants of the Russian Arctic, in the conditions of industrial development of territories. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 79(1), 1764304. https://doi.org/10.1080/22423982.2020.1764304

Slukovskii, Z. I., Guzeva, A. V., & Dauvalter, V. A. (2022). Rare earth elements in surface lake sediments of Russian Arctic: Natural and potential anthropogenic impact to their accumulation. Applied Geochemistry, 142, 105325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2022.105325

Slukovskii, Z. I., Dauvalter, V. A., & Shelekhova, T. S. (2025). Anomalies of rare earth elements and heavy metals/metalloids in modern sediments of small lakes in the north of Karelia (Arctic): Geology and technogenesis influence. Environmental Earth Sciences, 84(2), 68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-024-12073-4

Solovyova, V. M., & Cherepovitsyna, A. (2023). Prospective industrial complexes in the Russian Arctic: Focus on rare-earth metals. E3S Web of Conferences, 378, 06005. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202337806005

Song, J., Wan, S., Piao, S., Knapp, A. K., Classen, A. T., Vicca, S., Ciais, P., Hovenden, M. J., Leuzinger, S., Beier, C., Kardol, P., Xia, J., Liu, Q., Ru, J., Zhou, Z., Luo, Y., Guo, D., Langley, J. A., Zscheischler, J., Dukes, J. S., Tang, J., Chen, J., Hofmockel, K. S., Kueppers, L. M., Rustad, L. E., Liu, L., Smith, M. D., Templer, P. H., Thomas, R. Q., Norby, R. J., Phillips, R. P., Niu, S., Fatichi, S., Wang, Y., Shao, P., Han, H., Wang, D., Lei, L., Wang, J., Li, X., Zhang, Q., Li, X., Su, F., Liu, B., Yang, F., Ma, G., Li, G., Liu, Y., Liu, Y., Yang, Z., Zhang, K., Miao, Y., Hu, M., Yan, C., Zhang, A., Zhong, M., Hui, Y., Li, Y., & Zheng, M. (2019). A meta-analysis of 1,119 manipulative experiments on terrestrial carbon-cycling responses to global change. Nature Ecology and Evolution, 3(9), 1309–1320. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-0958-3

Soromotin, A. V., Moskovchenko, D. V., Khoroshavin, V. Y., Prikhodko, N. V., Puzanov, A. V., Kirillov, V. V., Koveshnikov, M. I., Krylova, E. N., Krasnenko, A. S., & Pechkin, A. S. (2022). Major, Trace and Rare Earth Element Distribution in Water, Suspended Particulate Matter and Stream Sediments of the Ob River Mouth. Water (Switzerland), 14(15), 2442. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14152442

Souza-Kasprzyk, J. S., Tkachenko, Y., Kozak, L., & Niedzielski, P. (2023). Chemical element distribution in Arctic soils: Assessing vertical, spatial, animal and anthropogenic influences in Elsa and Ebba Valleys, Spitsbergen, Svalbard. Chemosphere, 340, 139862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.139862

Souza-Kasprzyk, J. S., Zwolicki, A., Zmudczyńska-Skarbek, K. M., Convey, P., & Niedzielski, P. (2025). Contrasting effects of little auk colonies on potentially toxic and rare earth elements in Arctic soils. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 494, 138726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2025.138726

Steenfelt, A. (2012). Rare earth elements in Greenland: Known and new targets identified and characterised by regional stream sediment data. Geochemistry: Exploration, Environment, Analysis, 12(4), 313–326. https://doi.org/10.1144/geochem2011-113

Sun, J., Zhou, H., Cheng, H., Chen, Z., & Wang, Y. (2024). Bacterial abundant taxa exhibit stronger environmental adaption than rare taxa in the Arctic Ocean sediments. Marine Environmental Research, 199, 106624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marenvres.2024.106624

Turetta, C., Feltracco, M., Barbaro, E., Spolaor, A., Barbante, C., & Gambaro, A. (2021). A year-round measurement of water-soluble trace and rare earth elements in arctic aerosol: Possible inorganic tracers of specific events. Atmosphere, 12(6), 694. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos12060694

Turetta, C., Zangrando, R., Barbaro, E., Gabrieli, J., Scalabrin, E., Zennaro, P., Gambaro, A., Toscano, G., & Barbante, C. (2016). Water-soluble trace, rare earth elements and organic compounds in Arctic aerosol. Rendiconti Lincei, 27, 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12210-016-0518-6

Turetsky, M. R., Baltzer, J. L., Johnstone, J. F., MacK, M. C., McCann, K. S., & Schuur, E. A. G. (2017). Losing legacies, ecological release, and transient responses: Key challenges for the future of northern ecosystem science. Ecosystems, 20(1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-016-0055-2

Vasilevskaya, N. V. (2022). Polyvariance of ontogeny of Castilleja lapponica Gand. under industrial pollution of the Subarctic. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 981(3), 032075. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/981/3/032075