Introduction

On the morning of 4 August 1792, Mariangiola Vitiello appeared before the judge of the Gran Corte della Vicaria Criminale. She had a bottega di zagarellaria – what today would be a haberdashery – on the Riviera di Chiaia, next to the tavern of her husband, Raffaele Marinelli. She testified that while she was washing her youngest daughter’s skirt, her husband grabbed her by the arm and took her home, where both he and her mother-in-law beat her for running late at lunchtime. The following Monday, again at lunchtime, Mariangiola was working in her haberdashery when her husband brought her lunch, which she refused. Faced with this refusal, he took her out into the street and physically assaulted her. Aware that she was about four months pregnant and fearing a miscarriage due to the continuous mistreatment, Mariangiola called an obstetrician, who examined her, medicated her and recommended rest to avoid complications.Footnote 1

Beyond the details of the terrible situation of family and gender violence, this criminal trial presents women actively involved in the workplace, as well as their relationship with urban space. Among the witnesses were Marianna Durante and Antonia Garofaro, who, at the time of the second assault, were on the street buying fruit.

Although these descriptions are often sparse, they represent different forms of female labour, challenging the most widespread European historiographical view that women were relegated to domestic and private space while men left their homes to work.Footnote 2 Indeed, recent research on women’s work in early modern cities has challenged the prevailing notion of their absence from the labour market, a notion based primarily on fiscal and census sources.Footnote 3 Thanks to the use and combination of a wide variety of sources (notarial, judicial, accounting, etc.), economic and social history studies have shown the presence of women in different sectors of the urban economy, from manufacturing to services and retail trade. Urban institutions such as guilds, civic councils and charitable bodies have been identified as contributors to the limitation, or expansion, of women’s opportunities.Footnote 4 For example, in relation to guilds, some studies have proposed ‘an accordion movement’ as opposed to the thesis of a decline after golden years during the medieval age. They have highlighted how women themselves sometimes chose marginality and exclusion rather than admission to the guild, which is an indication of the opportunities offered by the illegal economy.Footnote 5

In these studies, unpaid work is seen as a complement and not a substitute for paid work.Footnote 6 Similarly, no less important was the role of dowries (seen in certain cases as deferred salaries) allowing the beginning of new activities in collaboration with the husband, changes of sector or migratory projects.Footnote 7 Crossing sources and indirect approaches, scholars have re-estimated female market participation, identifying a much more relevant role for the demand side (in terms of manufacturing and commercial activities) rather than the supply side (the time women can devote to work in relation to, for example, the number of children).Footnote 8 In this sense, the urban context offered women numerous legal and illegal employment opportunities.

Notwithstanding the recent research, quantitative approaches remain constrained and concentrated on the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This is characterized by recurrent deficiencies attributable to the comparatively diminished representation of women in documentation relative to their male counterparts. To address this issue, historians in the last two decades have adopted a new theoretical framework and methodological tools borrowed from economics. First, they incorporated a broader concept of work that includes economic activities performed within the household. In addition, they employed the verb-oriented method, which goes beyond reliance on occupational status by focusing on the concrete actions described in court sources and creating tools similar to modern time-use surveys. Studies on south-west Germany, Sweden and England have shown that women were active in almost every sector of the economy, often outnumbering men.Footnote 9 This has led Jane Whittle to propose a reconsideration of the concepts of ‘work’ and ‘economy’ since excluding domestic and care work from these definitions creates a paradoxical situation in which, although women worked more than men, their measured contribution seems smaller. This selective view of economic development ignores important female contributions to the production of goods for household survival, market sales and paid services, as well as the care work performed by men. Often, domestic and care work coincided with significant contributions to agriculture, trade and crafts, thus blurring the boundaries between reciprocal work and market work.Footnote 10

Research has focused mainly on central and northern Europe, while quantitative reconstructions of southern Europe are practically non-existent. In the case of Italy, for example, studies have largely taken a qualitative approach and have concentrated on urban areas, particularly in the central and northern regions of the country, partly because of the importance of institutions such as guilds.Footnote 11 However, the absence of quantitative analyses and case-studies on southern Italy is regrettable. In fact, specifically in Naples, since Luigi De Rosa pointed out the importance of studying women’s work to understand the economy of the kingdom, no comprehensive research has developed along these lines.Footnote 12

The peninsula was at the forefront of economic progress until the Renaissance, and scholars have identified the increase in female participation in the labour market as a key factor in the economic take-off of the North Sea economies at the expense of the rest of the continent, known as the little divergence. Understanding female employment patterns – especially through regional or urban case-studies – is therefore critical to identifying the factors that drove the development of capitalist economies.Footnote 13

This article aims to fill this gap by offering the first quantitative study of women’s work in an Italian urban context between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, particularly in southern Italy. It will show the activities of men and women in different sectors. It will look at gender balance and consider work in all its forms. In addition, the article will incorporate a spatial analysis that will allow us to understand how these gender dynamics at work were embodied in the organization and distribution of urban space.

Naples in the early modern age

The city of Naples is a useful case-study. Despite its relevance in early modern Europe, it has received less attention than other major Italian cities, which has limited understanding of its role in the economic and social dynamics of the period. It was one of the most populated cities on the continent and one of the main capitals of the Hispanic monarchy. Its status as an administrative and political centre fostered a court culture and a sophisticated consumer society sustained by manufacturing and commercial activities.Footnote 14 Its port, one of the most active on the Mediterranean, boosted the exchange of goods, people and ideas, consolidating the city as a strategic node in the Habsburg territorial network and in European trade and politics.Footnote 15

Its jurisdiction extended beyond its walls to include suburban and rural areas.Footnote 16 During the sixteenth century, its population grew exponentially due to peasant migration, making it the most populous city in Italy and the third most populous in Europe.Footnote 17 This influx transformed its economic structure and increased its dependence on agriculture and manufacturing.Footnote 18 At the end of the sixteenth century, however, the economy slowed due to a boom in imports and a fall in exports. Crises such as the eruption of Vesuvius (1631), the Masaniello revolt (1647–48) and the plague of 1656 aggravated the situation.Footnote 19

Despite these difficulties, Naples remained a dynamic city well into the eighteenth century. However, the lack of statistical records make it difficult to study the labour market, and the available sources, such as those of Antonio Genovesi and Giuseppe Maria Galanti, focus on male sectors and underestimate female labour.Footnote 20 In contrast, literary and iconographic sources show female participation in both the domestic and commercial spheres.Footnote 21

Sources and methodology

This article expands the notion of work beyond classical and neoclassical approaches by including all activities essential to household subsistence, such as assistance and care. Not limiting itself to the dichotomy between paid and unpaid work, it highlights the relevance of domestic and care work traditionally performed by women, whose impact on the economy is often underestimated.

In the last 30 years, there has been a push to include care work in economic indicators, although its measurement remains a challenge due to its informal and unpaid nature. To address this problem, economists and economic historians have drawn on the writings of Margaret Reid, who suggested in 1934 that those activities that can be substituted by the paid labour of others should be considered part of production.Footnote 22 In essence, if an activity that is essential for household subsistence can be replaced by wage labour, it should be fully recognized as part of production and included in evaluations of economic performance. Although complex to implement, this approach improves the accuracy of macroeconomic indicators and the understanding of the role of women in the economy. Although the approach was developed to analyse contemporary economies, it is particularly valuable for the study of pre-industrial economies, where domestic work and the role of women in the labour force have been underestimated.

However, tracing these activities is not straightforward. While we now have time-use surveys, we do not have equivalent tools for pre-industrial times. As a result, historians have had to resort to alternative sources to extract information on the rhythms of the lives of past populations. In particular, within European historiography, court records have proved particularly fruitful. The testimonies of victims and witnesses provide us with a vivid picture of the daily lives of pre-industrial populations. Whether directly or indirectly, the witnesses questioned inform us about their interpersonal relationships, social life, economic conditions and state of health, but, above all, they provide numerous details about their work activities.

Inspired by Sheilagh Ogilvie’s study on ‘time-allocation analysis’ in early modern Germany,Footnote 23 Maria Ågren and her co-authors at Uppsala University invented the verb-oriented method in the 2010s. This method focuses on activities described by verb phrases, including unpaid work and care work, as well as activities performed by people without a job title or those performed illegally.Footnote 24 Subsequently, Jane Whittle and Mark Hailwood have incorporated the two approaches, but they have adapted in various ways. In particular, they only collected evidence from court records of specific individuals performing particular tasks, defining their approach as the ‘work-task approach’.Footnote 25

This article follows the ‘work-task approach’ used in the English ‘Forms of labour’ project,Footnote 26 focusing primarily on court records and collecting evidence only of specific people doing particular tasks.Footnote 27 The analysis of court records has indeed been key to identifying the gender dynamics at work in Naples. Nevertheless, working with these sources presents several challenges. To obtain a sufficient volume of information, it was necessary to draw on documentation from two main courts: the Gran Corte della Vicaria and the Ecclesiastical Court of the Archbishopric of Naples. Each of these judicial bodies dealt with different types of offences – civil and criminal in the case of the VicariaFootnote 28 and moral and religious in the ecclesiastical courtFootnote 29 – which required engaging with distinct institutional logics and procedural narratives.

In both cases, priority was given to extracting information from direct interrogations, that is, from the responses provided by witnesses and victims to judicial officers. However, in the civil proceedings of the Vicaria, additional information was at times drawn from complaints or summaries produced by various officials, provided they described specific actions, namely what a particular person was doing at a given moment.

It is also worth briefly reflecting on the implications of using this type of documentation. In contrast to other sources, such as notarial records or documents from guilds and confraternities, judicial records were chosen for their richness and diversity. They offer access to forms of labour not governed by formal contracts, as well as to informal practices that are typically absent from other sources. These aspects are essential for understanding the nature of pre-industrial work and, in particular, women’s labour, as women were formally prohibited from engaging in certain occupations. As such, these records enable a broader and more inclusive understanding of the world of work.

That said, the use of judicial sources is not without its limitations. First, there is a risk of over-representation of certain occupations at the expense of others, particularly in the case of women. Professions related to care work – especially those associated with maternity, such as midwives and obstetricians – appear frequently, notably in cases concerning sexual offences or citizenship claims. In contrast, occupations linked to food preparation (meat, fish or baked goods) or certain manufacturing tasks are less visible. In many testimonies, women report being in markets, stalls or in their husbands’ workshops, without specifying the tasks they carried out. Although such cases have been interpreted as evidence of their involvement in business management, the lack of detail prevents a precise assessment of their actual contribution or level of participation.

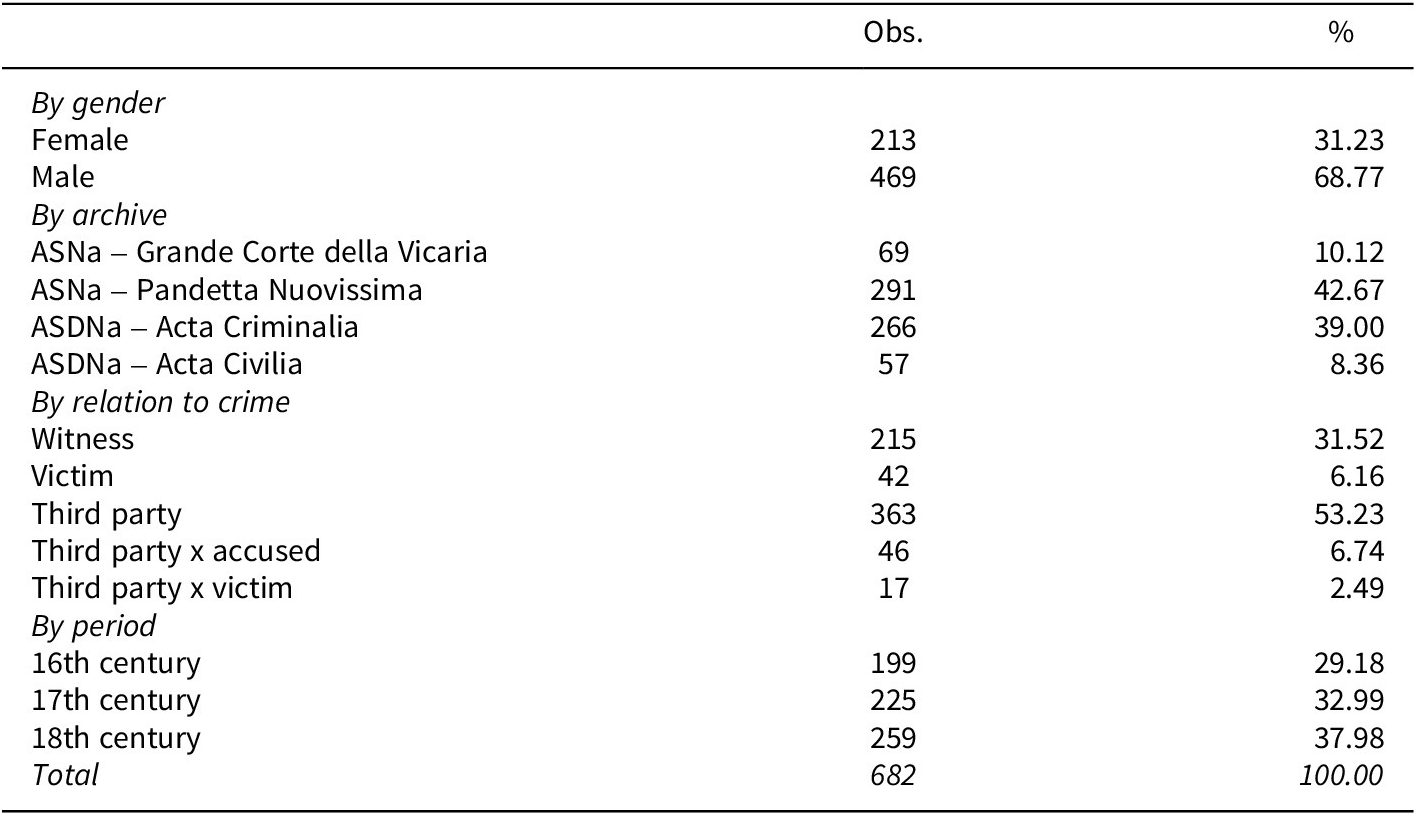

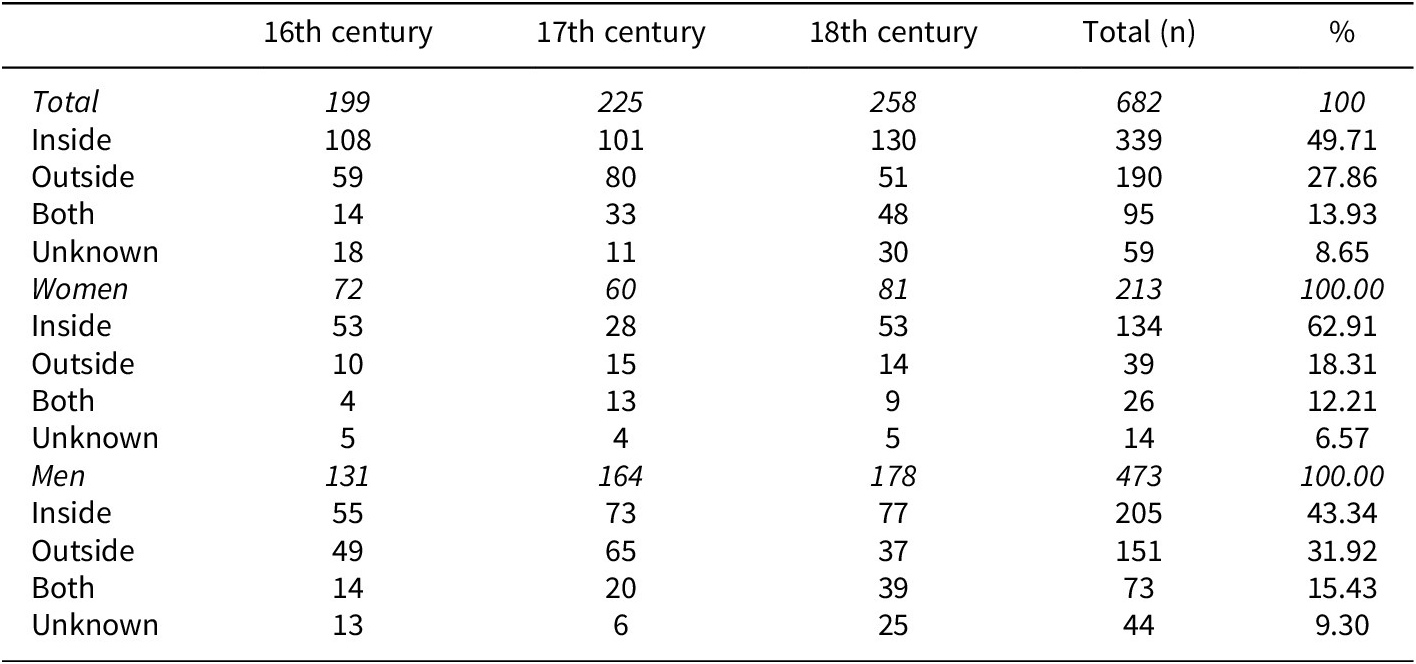

For these reasons, this study draws on records from courts with differing jurisdictions to mitigate, as far as possible, the limitations inherent in each type of source and to provide a more comprehensive and nuanced portrayal of women’s work. The use of this documentation has made it possible to uncover new insights into the labour landscape of urban Naples. One of the key findings is that of the 682 observations of work recorded, 31.23 per cent correspond to women. This can be seen in Table 1, which summarizes all the data obtained according to gender, the archive of provenance, the relationship of the witness to the crime and the chronological period.

Table 1. Work task dataset

Sources: ASNa, Grande Corte della Vicaria – Ordinamento Nocera Iovino, bb. 7, 13, 16, 17, 18, 26, 37, 38, 39, 61; PA, PN, bb. 1486, 1493, 1503, 1506, 1515, 1518, 1519, 1535, 1546, 1547, 1601, 1611, 1621, 1637, 1672, 1681, 1682, 1689, 1790, 2038, 2041. ASDNa, Acta Civilia, bb. 19, 115, 116, 117, 118, 121, 406 407, 631, 1515; Acta Criminalia, bb. 127, 208, 314, 324, 326, 333, 338, 780, 789, 795, 798, 816, 1184, 1194, 1221, 1256, 1821, 1827, 1831, 1844, 2249, 2273, 2276, 2291, 2298, 2305, 2607, 2674, 2738, 2994, 3295, 3414, 3415, 3417, 3665, 3679, 3688.

Although this percentage is similar to those obtained in previous studies, such as those of Whittle and Hailwood (29.04 per cent) andFootnote 30 Ogilvie (33 per cent),Footnote 31 it still reflects the unequal representation of women in historical sources. Most of the data come from male witnesses who reported the work of others. Unfortunately, they refer more to men’s work than to women’s work.Footnote 32 There is also a slight discrepancy in eighteenth-century records due to the uneven preservation of sources.

Finally, an analysis of the judicial records made it possible to identify the areas of the city where economic activity was concentrated. As shown in Figure 1, most of the work recorded was located in the old city centre, especially in the neighbourhood of San Lorenzo, a key area due to its connection with the ecclesiastical hierarchy, the administration of justice, banks and notaries. The areas near the port also stand out, such as the Porto-Pendino neighbourhoods, characterized by a large presence of small shops and workshops. Finally, in the southern sector of the city, the neighbourhoods of Montecalvario and San Ferdinando, together with Borgo di Chiaia, outside the city walls, were home to numerous workshops, taverns and street stalls in an environment marked by a military presence.

Figure 1. Map with total work tasks by neighbourhood.

For the quantitative analysis of our work tasks, we have chosen to adopt the classification system proposed by Whittle and Hailwood,Footnote 33 which consists of 10 overarching categories, each subdivided into a variable number of subcategories. This system was selected for its versatility and adaptability to our context, as its layered structure allows for a detailed and granular analysis while also ensuring that the results are easily comparable with those in the previous literature. The first macro-category is ‘agriculture and land’, encompassing all activities related to fieldwork and livestock. ‘Care work’ pertains to all caregiving activities, such as childcare, nursing and elder care. ‘Commerce’ groups together all tasks that involve some form of exchange, including those that involve monetary transactions as well as barter. ‘Craft and construction’ includes all manufacturing and construction-related activities. ‘Food processing’ is a category that includes all activities related to the transformation of raw materials into consumable items, but it does not encompass cooking. ‘Housework’ refers to all activities related to both house maintenance and caring for a house’s inhabitants, including cooking meals, doing laundry and attending to guests. ‘Management’ is a broad category that combines both work organization activities and financial matters, including lending/borrowing money and goods. This macro-category also includes activities related to farm management and public office roles, such as customs officials and city gatekeepers. ‘Transport’ encompasses all activities related to the transportation of goods and people. Finally, the ‘other’ category includes anything that does not fit within the above-mentioned categories or represents evidence that is too general to categorize, such as ‘that morning on my way to work’. It is worth noting that this final category contains various specific but non-trivial activities, such as those of barbers, doctors, religious figures and gravediggers.

A first quantitative analysis of women’s work

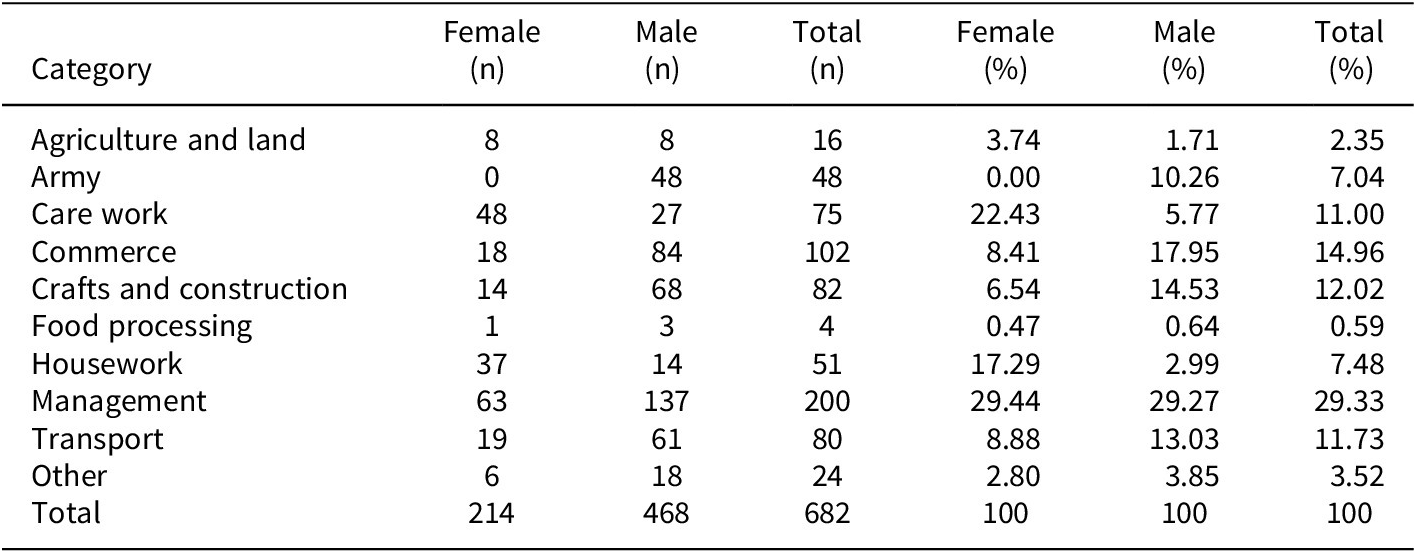

One of the first questions that arises when looking at women’s work regards which sectors they were most active in. Table 2 shows the total number of work activities carried out by men and women divided into nine categories. This shows that women participated in almost all sectors, except for the military, reflecting broad integration into the labour market.

Table 2. Work tasks by gender

As mentioned above, this raw data mask the under-representation of women in judicial sources, where male witnesses predominate.Footnote 34 Further analysis of the dataset shows that 31 per cent of the work activities were performed by women. To address this gender bias, we applied a 50/50 multiplier proposed by Whittle and Hailwood. This adjustment simulates a dataset in which the number of work tasks is evenly divided between men and women.Footnote 35 The method invites us to consider how the data would change if 50 per cent of the work tasks were performed by women. If we look at Table 3, which contains the results obtained applying this method, we can see that women would have performed 68.52 per cent of agricultural tasks, 50.14 per cent of managerial tasks and 57.17 per cent of transport tasks. Their participation in manufacturing and trade was somewhat lower but still significant.

Table 3. Work tasks carried out by women and men by category, with multiplier and gender gap

a The numerical data reflect the difference in percentage – after applying the multiplier – between male and female work tasks. A positive value indicates a gender gap in favour of men; a negative value indicates a gender gap in favour of women.

In contrast, the gender gap was accentuated in the care sector, where almost 80 per cent of the tasks were performed by women, rising to 85 per cent in domestic work. This distribution suggests not only a strong feminization of these jobs but also the possible existence of a double workday for many women.

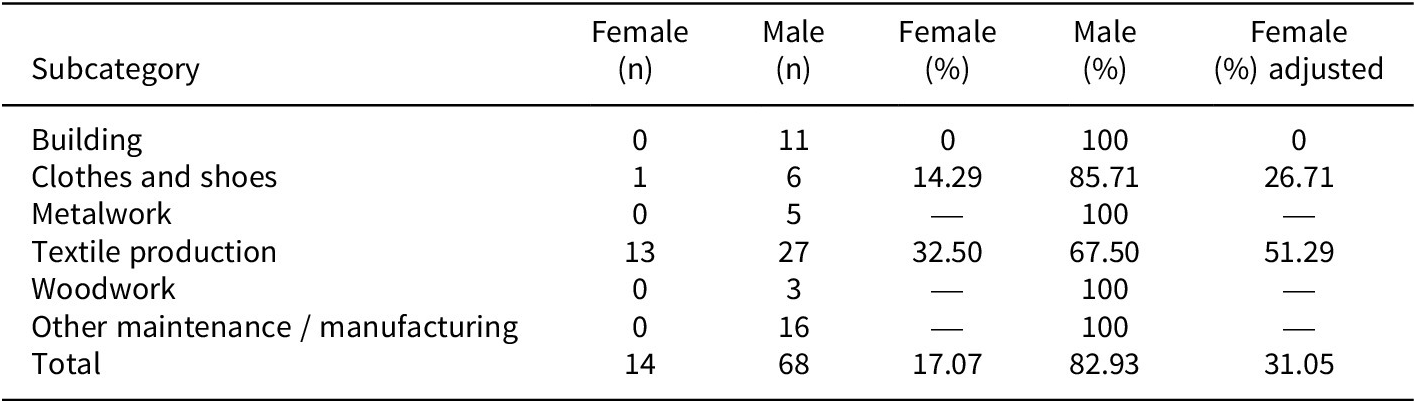

Crafts, commerce and management

In the urban economy of Naples, which was dominated by services, women were active in manufacturing, trade and management, albeit with marked gender segregation. In ‘craft and construction’, they accounted for 31 per cent of registered activities. However, in Naples, where there was a real building frenzy,Footnote 36 while men predominated in construction, building repair and metal and wood working, women played a central role in textile production (Table 4). Their work focused on the management of looms and the processing of velvet, silk and wool, as well as the bleaching and preparation of fabrics – activities closely linked to trade and external consumption. Textile work was usually done at home, where women worked with their families, turning the home into a workshop.Footnote 37 This model encouraged the transmission of knowledge and collaboration in production. A prominent example is that of the masters Olivieri Sorrentino and Isabella Riccia, who lived and worked in a small home-based workshop together with their two sons, a daughter and three employees in 1585.Footnote 38 As their activity expanded, they soon moved to a larger residence in the casale of Torre del Greco, a rural enclave under Neapolitan jurisdiction. The growth of this enterprise therefore relied largely on women’s labour, whose contribution was essential both to production and to the management of the household economy. The family organization of labour not only ensured the manufacture of high-quality goods but also fostered the active involvement of all household members in the business. The Olivieri workshop’s expansion and subsequent relocation demonstrate how home-based labour, beyond securing the family’s subsistence, could underpin the development of broader commercial networks.

Table 4. Gender division of labour in crafts and construction work tasks, with multiplier

This type of situation also allows us to examine the role of women in the textile sector. As it was a collaborative form of work, in some cases, women could be formally recognized as ‘maestre’ (master craftswomen). A telling example is the case of Marco Cauterio and Savoia di Mauro, a wool-weaving couple who, in October 1780, employed around 15 workers in their workshop located near the church of Santa Maria della Scala. In the context of a legal case concerning their production, a witness named Gaetano Mescello stated, ‘This morning, upon arriving at their home – where I also work as a wool weaver – I encountered my mistress, whom I alerted that someone was knocking at the door.’Footnote 39 This testimony not only confirms the active involvement of women in the production process but also reveals that they could hold authority within the workshop and had the capacity to instruct other workers.

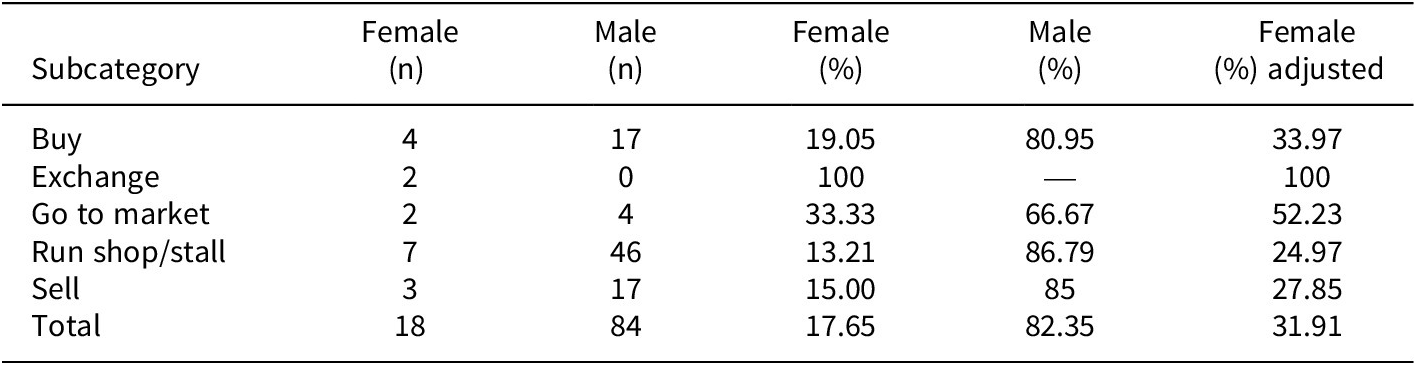

In the commercial sector, as shown in Table 5, women were involved in the commercial activities of the city, working in stores, taverns and workshops. An example is Joana Arzonita, who ran a fruit shop in San Lorenzo with her husband in June 1650.Footnote 40 However, men predominated in the ownership and management of large shops, while women tended to run small businesses, especially in local markets. An example is the widow Domenica Petrella, who sold chestnuts in Santa Lucia.Footnote 41 In addition, tasks such as going to the market were shared by both sexes, reflecting a certain inter-relation in daily economic life.

Table 5. Gender division of labour in commerce, with multiplier

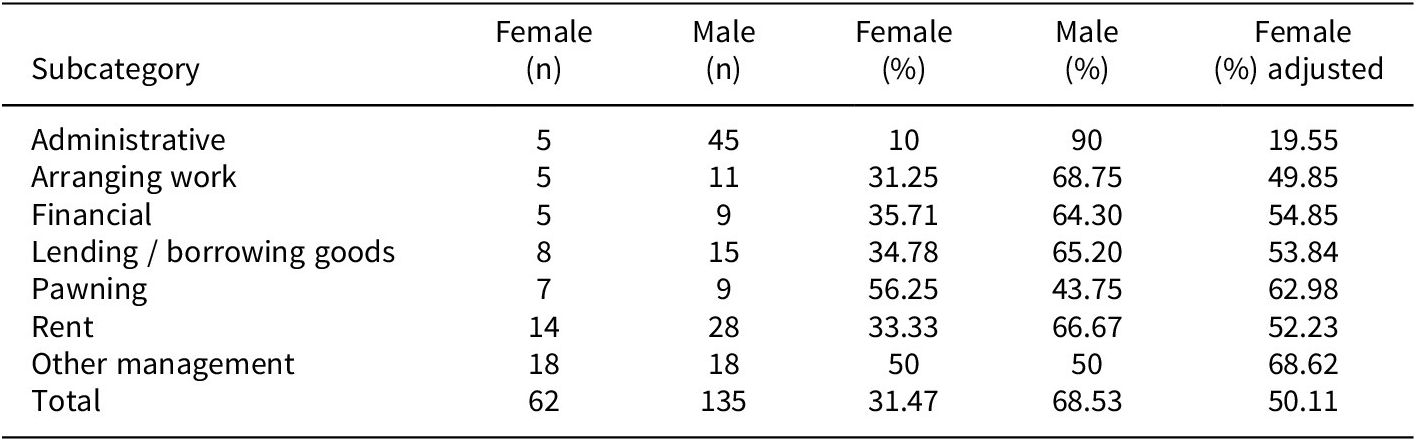

These gender dynamics contrast with those in the management sector. Men and women participated in a similar way, especially in the management of leases, a key aspect of the Neapolitan economy, where women performed more than half of the recorded activitiesFootnote 42 (Table 6). An example is Camilla Seripanna, who managed the lease of a property in San Martino in 1570.Footnote 43 In addition, women stood out in the area of loans,Footnote 44 accounting for 52.23 per cent of these activities, although they were also the most affected by debt (62.98 per cent).Footnote 45 These transactions, often informal and combined with other work, are evidence of women’s pluriactivity and their ability to accumulate capital, especially in the case of maids.Footnote 46 Women were economically versatile in pre-industrial Naples, and the courts recognized their financial transactions as legitimate. In 1675, for example, Giulia de Angelis lent money and managed to recover her debt thanks to a trial before the Archbishop’s Court;Footnote 47 in 1750, Elisabetta de Rojas combined her trattoria on Via Toledo with a clandestine pawnshop.Footnote 48

Table 6. Gender division of labour in management work tasks, with multiplier

However, some reflections are warranted in these latter cases. In that of Elisabetta de Rojas, for instance, the pawning activity appears to have been more structured, with written notes specifying payments and a designated space for the transactions – albeit operating clandestinely – suggesting the existence of formalized loans and credit agreements, possibly with interest. As she herself stated, ‘And the said Giuseppe returned together with the aforementioned cleric, and the witness once again wrote a note for other items pawned by the same individuals, writing it on a decorated writing desk placed in the middle of the room.’Footnote 49 By contrast, most of the documented cases, such as those of Giulia de Angelis, were of a more informal nature, which likely made these women more vulnerable to debt.

Although women were actively involved in management, there were significant differences in administrative tasks. Most of the activities documented were related to the judiciary and the civil service, sectors inaccessible to women. However, many managed estates and debts through notaries and lawyers, demonstrating their involvement in legal matters. In the other management category, tasks related to household management predominated, especially among elite women who supervised domestic services and administration.Footnote 50

One significant – though not isolated – example is that of Ippolita Pollastro, who in 1550 was called to testify in a homicide case that had occurred in Vico Pannetero. In her statement, she declared that ‘in the afternoon, I sent my servant Joan to buy some food’.Footnote 51 Such descriptions reveal her capacity for management within the domestic sphere. Taking on tasks, allocating resources and co-ordinating other household members were activities that likely extended into other work environments as well. The management of the household unit should therefore also be understood as a space of authority and responsibility for women.

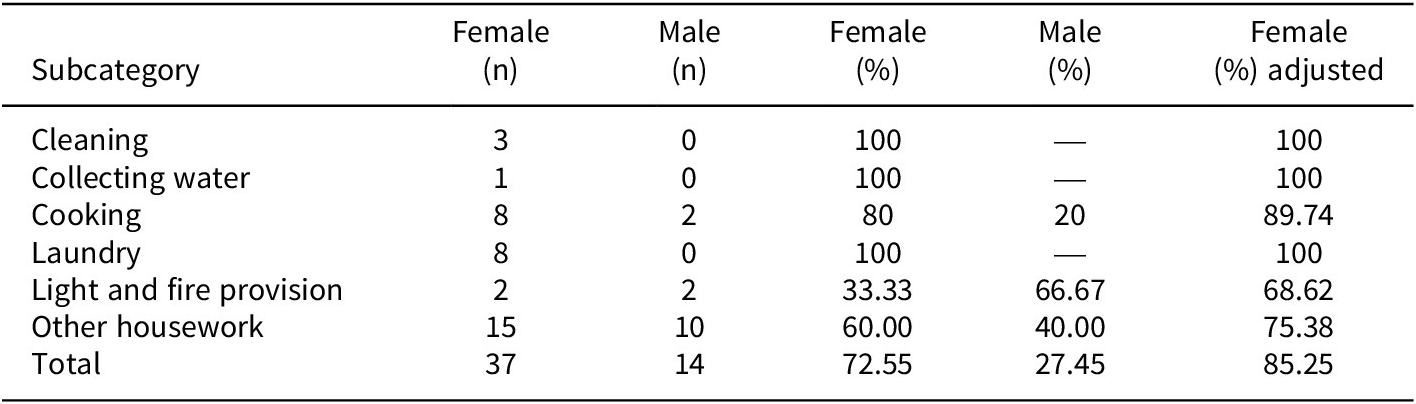

Housework and care

As the slave Fatima Cherchem recounted, because ‘she knows how to cook, spin, weave and do a few other things’,Footnote 52 household activities included cooking, spinning and weaving, although in this study, we have differentiated the tasks intended for commerce. We have thus included in the housework category activities that were carried out inside or outside the house but related to the maintenance of the household, such as cleaning, water collection, cooking for non-commercial purposes, washing clothes and making fires (Table 7). Examples include, once again, the case of Ippolita Pollastro, who ‘was tending the fire when she felt a strong blow to her back’Footnote 53 from the individual under investigation for homicide, or that of Lucia Golena, who in 1571 ‘was paid to wash the clothes of the cleric Giovanni Felice Grosso’.Footnote 54

Table 7. Gender division of labour in housework tasks, with multiplier

Similarly, in this area, it is important to highlight the work of servants employed in households and other institutions, included in the subcategory other housework,Footnote 55 as their functions were not always specified in the legal proceedings. This was the case of Isabella Porcia, who in 1699 declared that she ‘was at service’ (se ritrovava al servitio) with her lords in San Lorenzo, without providing further details about her tasks.Footnote 56 Giulia Buonocore also provides an illustrative example: in 1572, she sued the nuns of Santo Ligorio (Borgo dei Vergini), stating that they owed her wages ‘because for two years she had faithfully served in all duties required of her, both by day and by night’.Footnote 57

However, caution is required when analysing this type of work, as testimonies often reveal that behind generic designations, such as ‘being at service’, lay a wide range of tasks, frequently connected with caregiving and domestic management and therefore included within those same categories. In this sense, the case of Faustina Exposito is particularly significant. Her name appears in several third-party testimonies identifying her as serva di casa, which suggests that her role was clearly recognized within the domestic sphere. Nevertheless, when she was questioned about the death of Patrizia Maggio, she declared, ‘Together with my mother, who helped me with all the services required of me, we dressed his body and placed a piece of white cloth over it.’Footnote 58 This testimony reveals that these women were not only responsible for the everyday maintenance of the household but also for duties linked to care, companionship and the preparation of bodies at the most delicate moments of family life.

A similar situation can be observed in other types of labour related to agriculture and work on land. Such is the case of Portia Buono Accurso, who in 1572 was at the service of Signor Giovanni Francesco de Maiorino. According to his own testimony, ‘I was at the service of Signor Maiorino, my master (padrone), and I did all that he commanded me…and I knew very well those who came there, because they often visited the garden (giardinetto) of his house while I worked the grass there.’Footnote 59 This was related to gardening and was therefore linked to ‘agriculture and land’.

On the other hand, two relevant aspects of domestic work should be noted. The first is that it has been found that much of this work was paid, and the second is that in the majority of the cases recorded, work was done for other families.Footnote 60 Although there is little data on the marital status of the workers, widows and single women predominated among maids and servants. Some, such as Isabella Boccia, gave up her salary in exchange for accommodation after becoming a widow and moved to her nephew’s house in Montecalvario in 1640, where she performed domestic and service tasks.Footnote 61

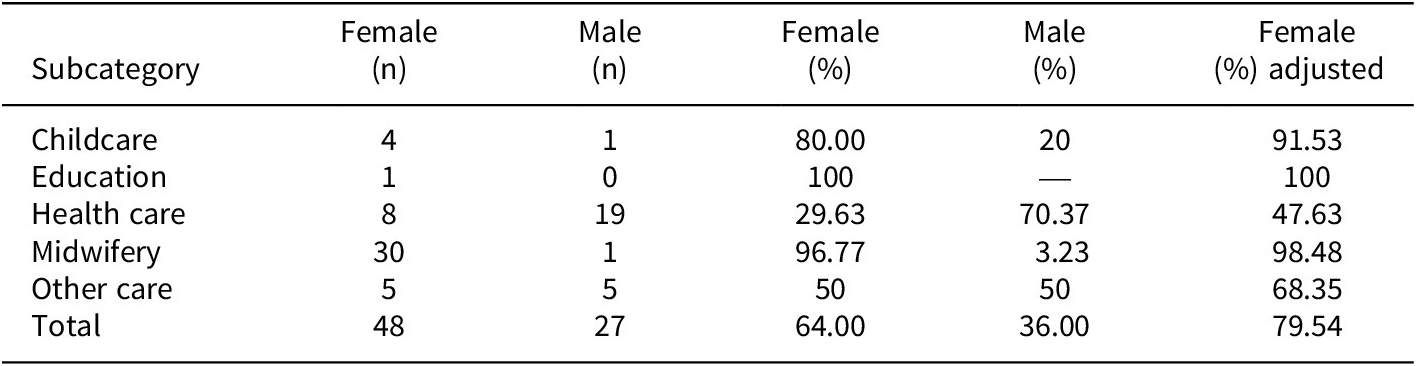

Housework was closely linked to care, with high female participation. Table 8 shows that 79.54 per cent of the caring activities were performed by women. However, men predominated in health care, as this category included barbers and surgeons who testified in court cases about patient care and medication, especially in cases of injuries caused by violence.

Table 8. Gender division of labour in care work tasks, with multiplier

The most important aspect in the field of care in pre-industrial Naples was the work of the mammane – Neapolitan midwives – as shown in Table 8. They were central figures in the care of women and children, with great authority and knowledge of women’s health.Footnote 62 Women such as Camilla de Lieto in 1590Footnote 63 or Silvia Camardella in 1627Footnote 64 would have enjoyed status and social respect. Usually over 30 years of age, they were called immediately when a woman went into labour. The mammane worked with the help of a woman’s relatives and domestic staff. However, in addition to attending births, they performed religious and legal functions, such as registering baptisms or transferring newborns to foundling homes. Although they were not formally organized, in the eighteenth century, they were officially recognized as publica ostetrica (public obstetricians), which allowed them to testify in legal proceedings, especially in cases of rape. Obstetricians such as Carmina Leso in 1773Footnote 65 and Palma Carbone in 1796Footnote 66 were essential for physical examinations and expert opinions. Finally, the paucity of evidence suggests that the care and education of children was carried out alongside other activities.Footnote 67

Gendered spaces

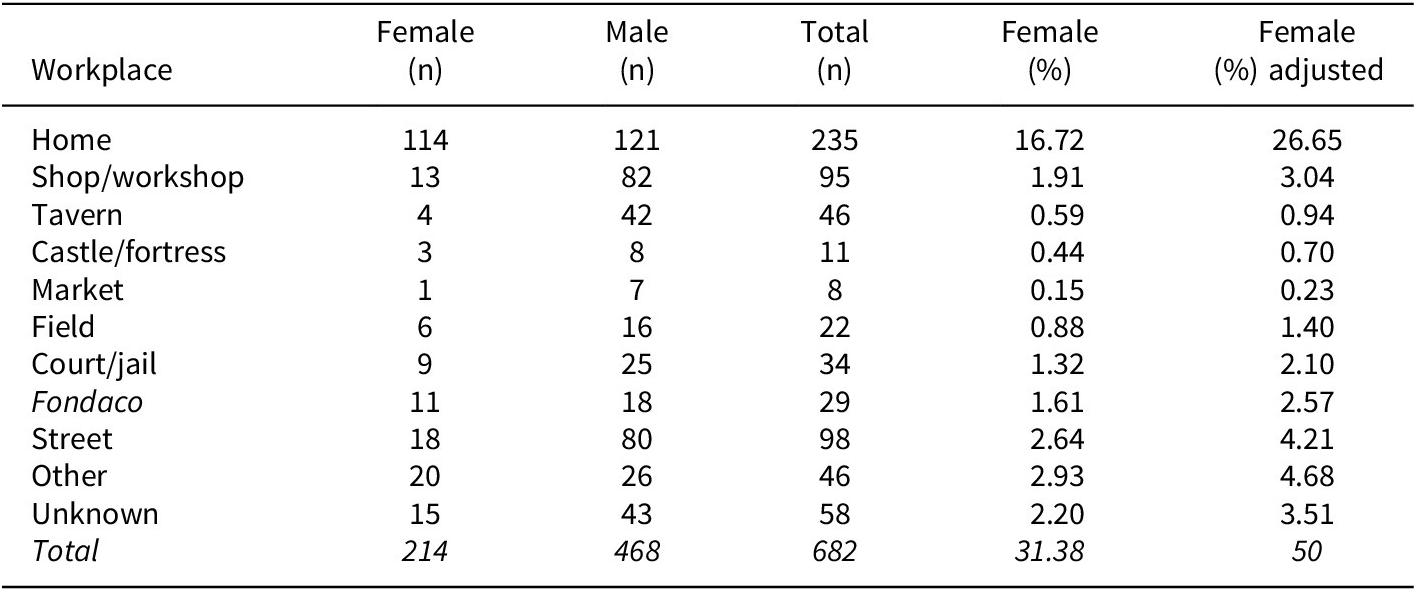

The Neapolitan trials offer a valuable opportunity to analyse how gendered differences in work affected urban space. In recent years, historiography has challenged the public/private, domestic/extra-domestic dichotomy as definitive analytical categories, proposing more flexible approaches that reflect the complexity of the world of work.Footnote 68 As Table 9 shows, although men and women mostly worked in their own or other people’s homes, the diversity of workspaces was significant. While there were gender differences in workplaces, these boundaries were more dynamic and permeable than traditionally assumed, demonstrating the interconnectedness of domestic, commercial and production activities in the city.

Table 9. Workplace by gender (absolute value and %), with multiplier

First, indoor spaces such as homes, workshops, stores and taverns were essential to the urban economy. While the home has traditionally been associated with women and the protection of female honour,Footnote 69 Table 9 demonstrates its role as a centre of labour and commercial activity.Footnote 70 Cases such as those of Casandra Maresca, who in 1547, together with her husband, was a master craftswoman and ‘trained in the arte di opera bianca (bread and pastry making) working from home’,Footnote 71 Isabella de Jorio, who in 1572 managed loans from her residence,Footnote 72 or Adriana Argiento, who in 1773 worked at her loom,Footnote 73 all reflect the multifunctional nature of the household. These examples show that although women carried out much of their work at home, their activities went beyond domestic maintenance, being key in sectors such as textiles.

In addition, we should not forget the presence of men in these domestic-productive environments, including servants, apprentices and tenants, which indicates their role as spaces of production, socialization and trade. In the case of men, their place of work often coincided with their place of residence. A significant proportion of individuals engaged in labour in taverns and workshops and resided within the same physical boundaries where they pursued their occupational endeavours.Footnote 74 This phenomenon is exemplified by the case of Michele Ponte, who, in 1699, was preparing to repose in his wooden workshop when he was abruptly interrupted by an undertaker who required the tool he was working with.Footnote 75 Furthermore, fortresses and castles functioned not only as workplaces but also as residences for military personnel and their families.

An additional noteworthy observation is that the interior spaces exhibiting a more pronounced gender disparity were those associated with commercial activities, such as taverns, stores and workshops. In these contexts, male presence was notably in the majority, although this did not imply that women were not involved, especially in the case of married women, who often participated in the management and operation of the family establishment.Footnote 76 It was customary for women to provide testimony that attested to their presence at their husband’s establishment, whether it be a store or a workshop, during the period in question. To illustrate this point, consider the testimony of Laura de Costa, who, on the afternoon of Holy Monday in 1550, was present in her husband’s tavern in the San Lorenzo neighbourhood when her injured brother-in-law arrived.Footnote 77 A parallel phenomenon emerged in the realm of public street life, where males predominated in military roles, surveillance activities and the transportation of goods. However, it should be noted that the street was not off limits to women. As demonstrated in Table 10, a significant proportion of women were engaged in employment outside of enclosed spaces, albeit in smaller numbers and predominantly in domains such as domestic work, care services and business.

Table 10. Work tasks with location by century and gender

Table 10 presents a categorization of the data according to work environment, distinguishing between external, internal and mixed environments. The results demonstrate the diversity of women’s work in the urban context of Naples. While their presence was less prevalent than that of men, women were also employed in both indoor and outdoor environments and often in both simultaneously. This trend has persisted throughout the early modern age. While the problem of under-representation in the sources remains, many women were engaged in market activities, ran street stalls or performed domestic chores outside the home. A substantial proportion of these activities, including the provision of food, the collection of water and the washing of clothes, constituted extensions of domestic work undertaken outside the home. For instance, in 1775, a group of women was denounced for throwing dirty water on the streets of the Riviera di Chiaia.Footnote 78 Despite the absence of formalization, these activities contributed to domestic maintenance and, in numerous instances, entailed compensation, as evidenced by the employment of domestic servants, couriers and textile workers. These activities, despite their domestic nature, facilitated connections between women and alternative economic circuits.

Thus, women’s work was not limited to indoor or outdoor spaces. As Table 10 shows, in 26 cases, it combined both. They could be inside these places but at the same time have a relationship with the outside. Windows and doors, for example, were key points for the promotion of products or services, as in the case of Constanza, who in 1599 advertised her services from the window.Footnote 79 This example testifies that just as workers in stores, workshops or taverns did, women often projected themselves into the public space by advertising their services in the street. Moreover, in the port cities of pre-industrial Italy, there were fondaci, spaces that perfectly represented the hybridization between the street and the home. These buildings, organized around an open courtyard, were used for storage, as well as for commercial and domestic activities. Women such as Portia della Paterna washed clothes in 1625 for neighbours in the Fundaco di Castiglia (San Lorenzo district).Footnote 80 There were also those such as Anna Picinelli, who managed a small loan business in 1751 in the same neighbourhood, evidencing the interconnection between housing, work and commerce.Footnote 81

Conclusions

A thorough analysis employing the work-task approach and judicial testimonies in early modern Naples reveals the presence of women in all economic sectors, as well as the existence of gender divisions. While women primarily engaged in domestic and care activities, they also made significant contributions to management, trade and manufacturing, albeit with constraints within each sector. In the context of commerce, for instance, women were predominantly present in small local markets, while men were responsible for larger businesses. In the realm of real estate management, the practice was shared, while lending was predominantly undertaken by women in the informal context. The urban economy thus offered employment opportunities, particularly in the field of textile manufacturing, where guilds admitted their employment in several occupations. Jobs related to silk (e.g. thread twisting) and velvet – but most significantly, the ‘new manufactures’ (ribbons, bags and hats) – provided numerous employment opportunities. However, the remuneration offered for these roles was lower than that offered to male workers. Conversely, many domestic and service activities offered partial or full remuneration in the form of salary, food and lodging, the last a particularly valuable benefit for single women and widows. From a social perspective, mammane played a fundamental role, wielding absolute authority over the health of women and children. This role encompassed medical, religious and legal functions, similar to those documented in northern Europe.

At the spatial level, the study calls into question the conventional dichotomy between the public and private spheres by demonstrating that both men and women engaged in a combination of home-based and outside activities. In certain sectors, such as textiles and the management of taverns and inns, there was a convergence of home and work for men. Conversely, the home functioned as a multifunctional space that hosted commercial and productive activities, especially in the textiles sector, and involved individuals outside the family nucleus. Furthermore, while commercial spaces were dominated by men, outdoor public spaces were also frequented by women, demonstrating the mobile nature of their work activities, with frequent travel between the home and the workplace.

In conclusion, the traditional model that separates female work in the home from male work outside it does not reflect the reality of early modern Naples. The home was a productive and commercial space, and domestic activities transcended the private sphere. Rather than a rigid opposition between the private and the public, an interconnected labour system emerges with dynamic, flexible boundaries. This perspective allows us to reinterpret the division of labour in the pre-industrial economy with a more nuanced vision that is far removed from traditional schemes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Maria Ågren, Sheilagh C. Ogilvie, Mattia Viale and Francesco Maria Vianello for discussing various aspects of this study with us and two anonymous referees for their helpful suggestions, which contributed to improving the article. We also thank Carlos Sánchez-García for preparing the map. The sources and methodology section was primarily written by Andrea Caracausi, the case-study and the analysis sections were drafted by Verónica Gallego Manzanares and the introduction and the conclusions were jointly written. We thank all the participants in the project ‘Work, workplaces and mobility in preindustrial Italy: a gender perspective’ for the inspiring scientific exchange.

Funding statement

The research leading to the results presented in this article has been carried out within the framework of the PRIN 2022 project funded by the European Union – NextGenerationEU (Progetto 2022BMSNA3, ‘Work, workplaces and mobility in preindustrial Italy: a gender perspective’).