Introduction

When Luce Irigaray considers the differences between women’s and men’s discourses, she draws attention to the historicality of social communication practices: ‘Language is a product of the sedimentations of languages of former eras. Every era has its specific needs, creates its own ideals, and imposes them as such. Some are more historically durable than others: sexual ideals are a good example here. These ideals have gradually imposed their norms on our language’ (Irigaray, Reference Irigaray1993: 30).

Examining ‘cultural injustices’ and ‘generalized sexism’ manifested in language, she notes that positive valuation of the masculine and negative appraisal of the feminine has been a linguistic condition lasting for centuries (Irigaray, Reference Irigaray1993: 68). It is only natural, then, that feminist interrogations of language as a tool of discrimination will look both into the present and into the past, encroaching on the territory traditionally ascribed to sociolinguistics and historical linguistics, bringing new insights and a fresh perspective on linguistic data.

Sociolinguistics has analysed the relation between gender and language from two research perspectives. On the one hand, numerous studies have focused on the analysis of the way in which women and men differ in their use of language (including, e.g., Lakoff, Reference Lakoff1975; Spender, Reference Spender1980; Fishman, Reference Fishman, Thorne, Kramarae and Henley1983). On the other hand, many other scholars have investigated the way in which men and women are represented in language, which led to the coinage of the term linguistic sexism (Pauwels, Reference Pauwels, Holmes and Meyerhoff2005). Despite its patent advantages, the former perspective cannot be applied to a great number of historical texts, since female authors are practically absent from medieval records of any European language, including English. As a result, scholars quite unanimously admit that ‘there might not be much material to throw light on matters such as social gender differences in Old English’ (Nevalainen & Raumolin-Brunberg, 2014: 18), since:

[t]he texts we do have are all the result of a tiny literate proportion of society – we can have no idea of how the average farm worker or travelling merchant spoke. Such persons remain, forever, a hidden majority. The literate community, furthermore, were, for the most part, members of religious communities, and this necessarily further limits the type of language which was written down. Those who wrote down our texts, although not necessarily those who composed the thoughts that were written down, were from a highly restricted stratum of the society. They were also likely to be from only a restricted age group, and virtually none of them were female.

Therefore, even though Anglo-Saxon textual records are relatively rich, the impact of social variables such as gender, age, education or social class on the English language may be analysed only from the early modern period onwards (Nevalainen & Raumolin-Brunberg, 2014), because in the sixteenth century a growing number of English-speaking women became literate and started to produce private correspondence.Footnote 1 Nevertheless, even for earlier stages of English it is technically possible to analyse the way in which women and men are represented in historical texts. So far, there have been no comprehensive corpus-based diachronic studies of this topic in the context of English, which means that it is still not clear how the linguistic image of men and women has evolved over the centuries. The aim of this Element is to fill in this gap and take a closer look at gender representation in the earliest records of English by means of advanced corpus methods, interpreting the results in a larger framework of feminist theory.

Considering the historical origins of the disadvantaged socio-cultural position of women, Cixous (Reference Cixous1976: 876) argues that they were ‘led into self-disdain by the great arm of parental-conjugal phallocentrism’ which was ‘self-admiring, self-stimulating [and] self-congratulatory’ (879), and manifested also in the power of discourse. If, as feminist linguists claim, gender-based oppression is and has been orchestrated through language, it seems particularly rewarding to trace this oppression back to early medieval times, to the stereotypical representations of gender differences which this Element attempts to demonstrate in the context of the English language. These representations contributed to the formulation of linguistic identity of women and men, informing English-speaking culture for subsequent centuries and legitimising its gender bias. Irigaray (Reference Irigaray1993: 31) identifies gender bias in language as an effect of an intentional strategy: ‘Man seems to have wanted, directly or indirectly, to give the universe his own gender as he has wanted to give his own name to his children, his wife, his possessions.’

1 Old English Written Records and Linguistic Insights into Anglo-Saxon Culture

Old English (OE) is a very well-attested early medieval language: the total length of all surviving texts written by Anglo-Saxons in their vernacular amounts to the impressive figure of 3 million words. This calculation includes poetry, interlinear glosses from Latin and prose texts, many of which have been preserved in multiple copies. The York–Toronto–Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Old English Prose (YCOE, Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Warner, Pintzuk and Beths2003) includes texts which cover 1.5 million words, omitting textual overlaps and word-for-word glosses of questionable value for syntactic investigations. The number might not be impressive from a contemporary corpus perspective, but for a historical language it is a considerable amount of data, allowing for the formulation of reliable conclusions based on recurrent patterns. Therefore, OE is a very good choice for a historical linguist wishing to study the earliest stage of development of an Indo-European language, and it provides a unique opportunity to analyse the relations between culture and language in the early medieval European context.

Naturally, our knowledge of Anglo-Saxon literary culture is mostly based on the well-known Germanic poetry records, including, for example, Beowulf, The Wanderer, The Seafarer and The Dream of the Rood. These works, however, famous as they are, constitute a really small portion of OE textual records. The York–Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Old English Poetry (Pintzuk & Plug, Reference Pintzuk and Plug2001) includes only 71,490 words in total, which is a significantly lower number than the 1.5 million words of the YCOE. What is more, the texts included in the prose corpus, even though most of them are fully focused on the Catholic faith, are quite varied in character. The most frequent genres are homilies (390,925 words altogether), lives of saints (298,316 words), chronicles (236,165 words), biblical translations (136,948 words), religious treatises (129,993 words) and medical remedies (68,315 words), while some minor text types include law collections, prefaces, travelogues, charters and wills. Thus the analysis of OE prose records may provide much more insight into the linguistic reality of Anglo-Saxon England than the study of poetic records, not only because of the sheer quantity of the data, but also because prose works, which are predominantly non-literary texts, may reflect a more conventionalised linguistic image of women in Anglo-Saxon society. Since literary language, which aspires to produce an aesthetic effect rather than conveying straightforward information, avoids patterns and regularities, the analysis of non-literary prose records might yield linguistic evidence with more reality value.

It is only predictable that written historical sources from the Anglo-Saxon period – chronicles, ecclesiastical documents, legal codes or wills – focus chiefly on the male part of society, making women significantly absent. Moreover, the civilisation reflected in Anglo-Saxon poetry was co-ordinated by tribal warfare and naturally centred on men, who formed the warrior class, while women could only assume ‘the non-roles of … peaceweaver and mourner for the dead’ or become symbolic treasure facilitating political goals (Bennett, Reference Bennett, Harwood and Overing1994: 43–45). Many marriages of the epoch were arranged, particularly but not solely in aristocratic circles; Anglo-Saxon women were ‘linked to male kin-groups’ and matrimony meant exchanging the custody of one man for ‘a new role of submission to another’ (Leyser, Reference Leyser1995: 47). The gendered division of population demanded that female activity concentrate on the family and local community matters, not public spheres. The division of labour in the peasant class also depended on sex: heavy agricultural work and craftsmanship was the males’ responsibility, while women engaged in ‘a wide variety of smaller tasks centered on the household’ (Bennett, Reference Bennett, Erler and Kowaleski1988: 18). Fell (Reference Fell1986: 40) notes that early Anglo-Saxon culture ‘distinguished male and female roles as those of the warrior or hunter and of the cloth-maker’. Indeed, archaeological evidence reveals that women were often buried with thread boxes, needles, spindle whorls, table linen or other pieces of cloth (Fell, Reference Fell1986: 40–44; Leyser, Reference Leyser1995: 3–15); their burial places also indicate involvement in other domestic activities, such as the preparation and the serving of food and drink (Fell, Reference Fell1986: 47–49) or medical assistance (Leyser, Reference Leyser1995: 15).

Examining the position of women in Anglo-Saxon society is especially problematic because the scholarly tradition that dominated the field until the 1990s continuously concealed the female presence from the study of historical reality, leaving ‘no place for a woman scholar who wanted to read as a woman’ (Bennett, Reference Bennett, Harwood and Overing1994: 43). Norris et al. (Reference Norris, Stephenson, Trilling, Norris, Stephenson and Trilling2023: 10) explain these discriminating patriarchal academic paradigms with the fact that the field of early medieval English studies was established ‘at the height of British imperialism’, and it developed in a political environment which ‘supported claims to White, male, European superiority’. Lees (Reference Lees and O-Keeffe1997: 148) also claims that ‘the institutional structures of the discipline’ have persistently marginalised ‘the role of women in the formation of [Anglo-Saxon] culture’. Desmond in turn notes that standard literary history studies (such as Greenfield’s Reference Greenfield1965 A Critical History of Old English Literature), rooted in masculine ideology and purporting neutral objectivity, fail to notice the ‘tremendous importance of women in Anglo-Saxon culture, as authors, characters, or voices’ (Desmond, Reference Desmond1990: 575).

As in other fields of cultural and literary studies, feminist criticism attempts to redefine the framework of scholarly approaches to OE texts: it challenges masculinist biased presuppositions, reconsiders the omissions of patriarchal paradigms of historical inquiry, retrieves silenced women’s voices and reclaims suppressed women’s perspectives. Early feminist studies of Anglo-Saxon literature, by such authors as Anne Klinck and Elaine Tuttle Hansen, already in the late 1970s examined OE poetry with the view of situating female anguish, confinement and submission in the context of early medieval English culture as well as moral implications of its poetic representation (Overing, Reference Overing1990: 76–77). Yet a wave of a more determined feminist response rose in the mid 1980s with the publications of Christine E. Fell, Jane Chance and Helen Damico, who strived to recognise women’s position in Anglo-Saxon society by means of presenting notable female individuals – queens, aristocrats, saints, abbesses – ‘to advance the argument that Anglo-Saxon society was relatively … egalitarian’ and to establish the ‘so-called “golden age” for Anglo-Saxon women’ (Lees, Reference Lees and O-Keeffe1997: 148–149). In her monumental 1984 work Women in Anglo-Saxon England, Fell, a historian, inspects multiple records of the epoch – vernacular literature, hagiography, legal documents, letters, inventories, archaeological evidence – to demonstrate the position and agency of women in early medieval English culture. In her study published two years later, Woman as Hero in Old English Literature, Chance (Reference Chance1986: 111) contradicts Fell’s confident view of female significance, pointing out that ‘Anglo-Saxon society demanded passivity, rather than leadership and initiative, from most of its women.’ The scholar finds ‘exceptions’ (111) of strong female individuals but notes that they were ‘permitted an active political role in kingdoms as chaste rulers or strong abbesses, and some became saints who were even allowed to adopt heroic behavior … once their chastity and sanctity had been attested’ (xv): that is to say, ‘the escape from passivity may only be accomplished by … an obliteration of femininity … women may be not-weak as long as they are not-women’ (Overing, Reference Overing1990: 78). Damico (Reference Damico1984) in turn seeks to subvert the pattern of female passivity in early medieval England by re-examining one of the most eminent examples of Old English poetic discourse, Beowulf, to interpret Queen Wealhtheow as ‘an autonomously powerful military figure, with the additional mythic and distinctively menacing qualities of the valkyrie’ (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Lees and Overing1990: 17).

Since the 1990s, feminist studies of Anglo-Saxon culture have continued with a rising awareness that gender actively interrelates to other aspects of human identity and cannot be reviewed in isolation. Recent feminist approaches to the field show an interesting dichotomy. On the one hand, a number of scholars endeavour to evidence substantial marginalisation and objectification of women in early medieval England. Overing (Reference Overing1990: 69–70), for instance, finds Beowulf ‘an overwhelmingly masculine poem’ which does not provide any place for women ‘in [its] masculine economy’: she believes that the Anglo-Saxon ‘system of masculine alliance allows women to signify [only] in a system of apparent exchange’, but not ‘in their own right’ (74), leaving them ‘profoundly silent’ (70) and ‘excluded figures’ (75). Similarly, Fee (Reference Fee1996: 290) discerns in Beowulf’s parallel between the rituals of ring-giving and peace-weaving the analogy which ‘exists between objects of material treasure and objectified women in the culture of the poem’: according to the transactional nature of Anglo-Saxon marriage, women ‘serve as commodities which are exchanged in order to safeguard a particular social or political agenda’ (285). On the other hand, there are concurrent approaches which intend to reclaim female agency in early medieval England and demonstrate that in the texts of this period ‘women are often depicted in roles which … are invested with more importance and capability’ than later (Harris, Reference Harris2014). This agency could be visible in their discourse, like Wealhtheow’s speeches, which, for Damico (Reference Damico2015: 206), prove her authority as ‘a female sovereign central to the administrative power of the court’. Alternatively, it could be part of other activities: for instance, Lee (Reference Lee, Norris, Stephenson and Trilling2023: 53) discerns it in their production of embroidery, ‘artifacts that provide a unique window to the participation … in the political, socio-economic, and intellectual life of the period’.

The relatively privileged status of women in Anglo-Saxon society was postulated and amply illustrated by Fell. The historian refers to numerous legal documents which testify to measures meant to protect women’s standing. Among them, there is morgengifu, ‘morning-gift’, the money that the prospective husband had to pay to effectuate marriage; importantly, it was ‘paid not to the father or kin, but to the woman herself’, and she could fully control it, for example, spend it, give it away, or bequeath it (Fell, Reference Fell1986: 56), because finances in marriage were ‘held to be the property of husband and wife, not of husband only’ (57). Fell also points to legal provisions regarding the economic status of widows or the protection of women against seduction and rape. She evokes instances of wills written by women or those in which men left property to their wives, mothers or daughters. Archaeological evidence or place names originated in this period also attest to women’s financial independence. Fell’s findings, as well as other related publications, indicate that even though women were not equal to men in terms of their legal and economic status, they ‘enjoyed a significant degree of autonomy’ (Desmond Reference Desmond1990: 585).

Yet Fell (Reference Fell1986: 14) discerns a ‘complete shift of pattern … within a single century after 1066’: the status of women in medieval England became aggravated after the Norman Conquest. This observation follows the postulate of Doris Stenton from her long-recognised work The English Woman in History: ‘[W]omen [in Anglo-Saxon England] were … more nearly the equal companions of their husbands and brothers than at any other period before the modern age. In the higher ranges of society this rough and ready partnership was ended by the Norman Conquest, which introduced into England a military society relegating women to a position honourable but essentially unimportant’ (Stenton, Reference Stenton1957: 348). This decline of female position could be seen, for instance, in economical rights: Anglo-Norman women could no longer hold land and make wills independently (Fell, Reference Fell1986: 154; Leyser, Reference Leyser1995: 74). Many historians interpret this as a result of changes in the inheritance system, which became based on male primogeniture (Fell, Reference Fell1986: 149; Leyser, Reference Leyser1995: 83). It was also, however, related to a modified approach to the feudal system: if in post-Conquest England ‘all land belonged to the king, … its use was conditional on the performance of military service’ and therefore ‘only men could hold land’ (Leyser, Reference Leyser1995: 86).

This conventional argument about the post-Conquest radical shift in the situation of women in England has been an object of criticism. Anne L. Klinck (Reference Klinck1982: 109), for instance, argues that ‘there is a much closer resemblance between the situation obtaining in late Anglo-Saxon England and post-Conquest England than there is between the early and late Anglo-Saxon period’ and, therefore, ‘to describe Anglo-Saxon England as a time when women enjoyed an independence which they lost as a result of changes introduced by the Norman Conquest is misleading’. Many feminist scholars claim that what really brought the change was the growing socio-cultural influence of Christianity and, especially, the institutional dimension of the church. Fell herself notes that ‘Christianity as interpreted by the fathers of the church developed a full set of theories on the inferiority of women’, but she puts into doubt ‘the extent of their actual application within society’ (Fell, Reference Fell1986: 13): even though she admits that we can easily find ‘traces of anti-female propaganda in letters or homilies from the pens of clergy and in the penitentials’, she authoritatively deems them ‘ineffectual in practice’ (13–14). For Chance (Reference Chance1986: xvii), however, the significance of the church should not be underestimated: she notes that the ‘two archetypes of women that ordered the Anglo-Saxon social world’ – Eve and the Virgin Mary – were of obvious religious roots, ‘drawn from the Bible’. In her later work, Chance openly asserts that women in medieval England, just like in any other European country of the era, ‘were always propelled by the misogyny of the church, and a masculine church at that’ (Chance, Reference Chance2007: 7). Perhaps the most persuasive work demonstrating the impact of the church on the degradation of the female position in late Anglo-Saxon society is Stephanie Hollis’ Anglo-Saxon Women and the Church. The scholar postulates that the deterioration of the standing of women, especially monastic women, dates ‘from at least as early as the 8th century’ (Hollis, Reference Hollis1992: 7), and that from Alfred’s reign ‘the literature reveals an increase in the prestige and authority of male ecclesiastics and a reduction in the status of women [which] parallels the overall tendency of canon law’ (1). Hollis strongly opposes Fell’s downplaying of ‘the social actualization of the church’s heritage of doctrines inimical to women’ (7) and points out it is impossible to deny ‘the social dominance of an institution whose most committed members were responsible for the composition and preservation of the only written evidence available to us’ (6). She sees this actualisation in numerous Anglo-Saxon texts, for instance in Bede’s hagiography, which propagates the opinion that ‘women constitute a separate and inferior class’ (8), or in Theodore’s penitential canons, which represent numerous ‘repressive conceptions of women … harboured by at least some churchmen, which fairly certainly included the most influential of them’ (8). The critic sees the conversion of England as a long process of cultural negotiation in which ‘[p]atristic-derived conceptions of women, … through mapping on to indigenous prejudices and inequalities, established themselves only slowly in Anglo-Saxon England’ (10) and contends that, at the end of the day, ‘what the assimilation of Roman-Christianity achieved was the alterization of women’ (10). This process must have been reflected in language and therefore, given the historical context, it seems both logical and necessary to take a look at the OE prose records, which are dominated by religious texts, in order to investigate the influence of Roman Christianity on the linguistic image of Anglo-Saxon women.

2 Language and Gender

Feminists have always considered language an important territory of their emancipatory struggle. Yet the onset of substantial and systematic research in feminist linguistics started only in the 1970s and 1980s. One of the landmark publications was Robin Lakoff’s Language and Woman’s Place (Reference Lakoff1975), which, by means of depicting ‘a culture-wide ideology that scorns and trivializes both women and women’s ways of speaking’ (Bucholtz, Reference Bucholtz, Ehrlich, Meyerhoff and Holmes2014: 26), revealed the political capacity of language to devalue and disempower women. An even more radical approach is pursued by Dale Spender in Man Made Language (Reference Spender1980). A wholehearted proponent of the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis, Spender notes that ‘it is language which determines the limits of our world [and] constructs our reality’ (Spender, Reference Spender1980: 139), so that this reality is determined by its linguistic representation. Naturally, then, those who control language are especially privileged, as they also control our notion of reality; Spender claims that men are the superior class which ‘has controlled language in its own interest, constructing sexist categories and meanings through which all speakers of the language view the world’ (Hendricks & Oliver, Reference Hendricks, Oliver, Oliver and Hendricks1999). In her very comprehensive study of the intersections between feminism and linguistics, Feminism and Linguistic Theory (Reference Cameron1992), Deborah Cameron points out that in the view of radical feminist theorists ‘male language is a species of Orwellian thought-control’ (Cameron, Reference Cameron1992: 129); if, as they believe, ‘words embody sexism because their meaning and usage is fixed by men from an antifeminist perspective’, then language can be considered ‘a cause of oppression, and not just a symptom of it’ (104).Footnote 2 Cameron emphasises the indebtedness of many feminist linguists to the theory of Jacques Lacan, who postulates that human subjectivity is formed through being introduced to the symbolic order of language. In this way, the roots of our identity reach the past generations because ‘language, with its structure, exists prior to each subject’s entry into it at a certain moment in [their] mental development’ (Lacan, Reference Lacan2006: 413). The French psychoanalyst also notes the patriarchal nature of the symbolic order, claiming that ‘[i]t is in the name of the father that we must recognize the basis of the symbolic function which, since the dawn of historical time, has identified his person with the figure of the law’ (230). This has obvious political consequences which feminist linguists have pointed out: ‘inserting oneself into culture means submitting to patriarchy’ (Cameron, Reference Cameron1992: 169).

Whether or not feminist linguists advocate the Sapir–Whorf theory and Lacan’s position, they mostly agree that language is a gendered phenomenon and that its ideologies inform our socio-political reality. They also concur that linguistic representations of men and women can function as

part of a society’s apparatus for maintaining gender distinctions and hierarchies. At the most basic level, they help to naturalize the notion of the sexes as ‘opposite’, with differing natures and social roles or responsibilities. Often, too, they naturalize the social inequalities which are associated with gender difference. [Some] feminine qualities are readily invoked to explain and justify the exclusion or marginalization of women in powerful or public roles, while at the same time reinforcing the idea of their natural suitability for other, more menial, tasks. … Ideological representations do not in and of themselves accomplish the subordination of women. Their contribution is rather to justify inequality, making the relationship of women and men in a particular society appear natural and legitimate rather than arbitrary and unfair.

Sexist bias is a very complex mechanism manifested on many different levels of language organisation. Feminist linguists indicate that ‘the lexicon and grammatical system of English contains features that exclude, insult and trivialise women’ (Cameron, Reference Cameron1992: 101).Footnote 3 As Weatherall (Reference Weatherall2002: 13) notes, linguistic manifestations of sexism may roughly be divided into three categories: ‘language that ignores women; language that defines women narrowly; and language that depreciates women’.

One of the most conspicuous issues raised by feminists, clearly related to Weatherall’s (Reference Weatherall2002) ‘ignoring’ type, is ‘the practice of considering the man/the male as the prototype for human representation’ (Pauwels, Reference Pauwels, Holmes and Meyerhoff2005: 553). This is related to the use of he and other masculine generics such as ‘chairman’, ‘mankind’, ‘guys’ or ‘fireman’ (Weatherall, Reference Weatherall2002: 14), the fact that the terms for human and male are often the same (cf. English man, whose sense 1 in the Oxford English Dictionary is defined as ‘a human being (irrespective of sex or age)’) or the frequently derivative nature of female terms (e.g. according to Etymoline the English term woman is an alternation of the compound wifmann, composed of wif ‘woman, wife’ and man ‘man, human being’). What is more, the occupational titles for women are rarely morphologically marked (with actress as a rare exception), and in English it is much more common to mark gender overtly for women (female doctor) than for men (male secretary) (Marco, Reference Marco1997), though English is now adopting a corrective strategy of making terms neutral or unmarked for gender, unlike, for example, French or Polish, where the terms are overtly marked as gender specific (Weatherall, Reference Weatherall2002: 17), for instance, French la ministre or Polish ministra as the overtly female equivalent of minister.

Another aspect of this problem, fitting Weatherall’s (Reference Weatherall2002) ‘narrowing’ type, is that women are often (or at least more often than men) discussed in terms of their physical appearance and family relationships, while in the case of men the focus is rather on their profession (Key, Reference Key1975). A related issue is the European practice of taking the husband’s name after getting married, the fact that female titles, unlike male ones, used to reveal the woman’s marital status (Miss and Mrs vs. the more recent, neutral Ms), and the tendency for female nicknames to be based on appearance and often (though not always) show connotations of beauty (e.g. Blondie, Sweetie, Midget), while male nicknames are rather based on activity and show connotations of power and hardness (e.g. Chaser, Mad Dog) (Phillips, Reference Phillips1990; Weatherall, Reference Weatherall2002: 23). Finally, within the ‘depreciating’ type of language sexism, there is a tendency of masculine terms to have more positive connotations than their feminine equivalents (cf. bachelor vs. spinster or mister vs. mistress), which results from the fact that with time female terms tend to undergo semantic derogation (Schultz, Reference Schulz1975), changing from once neutral to abusive, ‘ending as a sexual slur’ (Pauwels, Reference Pauwels, Holmes and Meyerhoff2005: 554).

Obviously, all of these linguistic aspects of the problem are a logical and clear result of the long-lasting patriarchal structure of European societies, with women’s roles limited to those of mothers, wives and lovers, fully dependent on men and often selected and judged on the basis of their physical appearance. The picture is changing right now, and the growing awareness of gender bias in English-language communities is a fact (Pauwels, Reference Pauwels, Holmes and Meyerhoff2005: 561). The aim of this Element is to take a step back, get to the roots of the issue and investigate the problem of gender representation in the earliest records of English in order to determine how gender bias operated in the Anglo-Saxon reality.

Our initial hypothesis was that at least some of the tendencies which feminist linguists observed in the English language in the 1970s and 1980s should already be visible in the OE data, and many of them should also be identifiable on the basis of recurrent collocations – that is, the fixed combinations of two lexemes that this Element is about to analyse. Therefore, the Element examines to what extent the most frequent collocations centred around a number of gendered nouns reflect the position of women in the Anglo-Saxon society. Our investigation seeks the ways in which OE phraseology suggests a marked difference in the social roles of Anglo-Saxon men and women. Drawing from other sources, we assumed at the outset that linguistic data should show connotations of power, hardness and activity for men, as opposed to beauty, physicality and sexuality for women. We expected that the collocations based on female terms would be more often associated with family relationships and physical appearance, while the equivalent male terms would rather collocate with lexemes focusing on profession or signalling domination. We also believe that establishing which of Weatherall’s types of linguistic manifestations of sexism (ignoring, narrowing and depreciating) may be revealed by a corpus-based analysis of collocations should become useful in the operationalisation of linguistic sexism for various language studies.

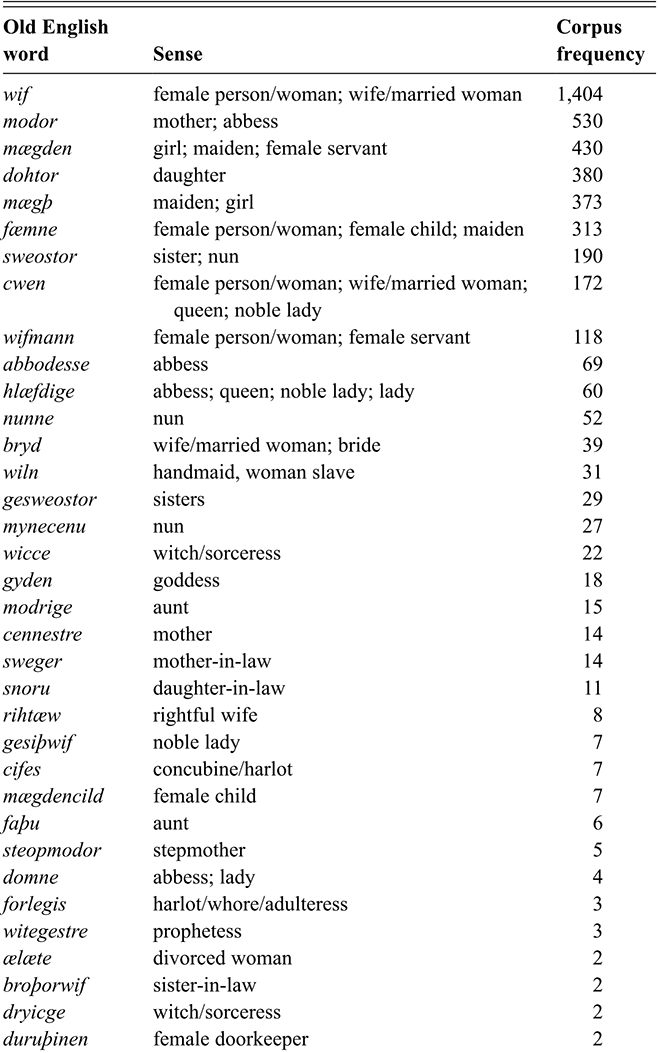

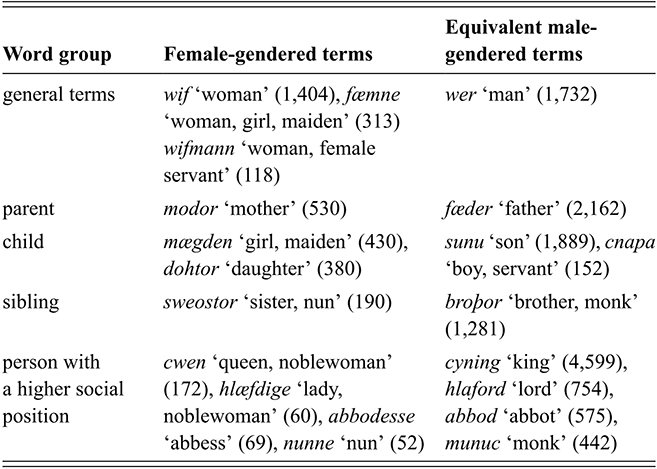

For the purpose of the Element, in order to analyse the linguistic image of women in OE, it was necessary to preselect a number of women terms and their male equivalents. The procedure was as follows: first, A Thesaurus of Old English (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Kay and Grundy2000) was browsed in search of all female-gendered nouns attested in this language. Next, the frequency of these words was checked in the VARIOE morphological dictionary for YCOE (Cichosz et al., 2022), and the words were arranged according to their frequency (cf. Table 1).

Women terms from A Thesaurus of Old English with their YCOE frequency

Table 1aLong description

The table consists of three columns: 1. Old English words, 2. their Modern English equivalents, 3. their frequency in the corpus, from the most frequent one wif (female person/woman; wife/married woman) - 1404 attestations, to duruþinen (female doorkeeper) - 2 attestations.

Table 1bLong description

Continuation of Table 1a. It lists women terms from fostermodor (foster-mother) - 2 attestations, to wifcild (female child) - 1 attestation.

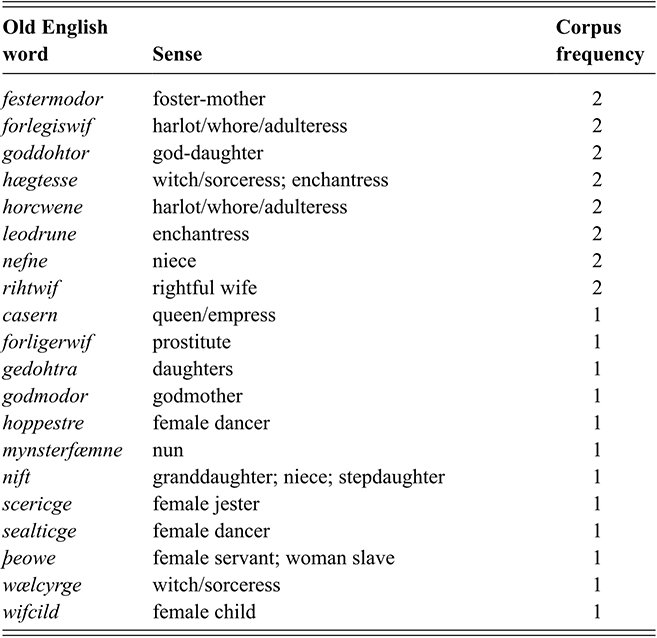

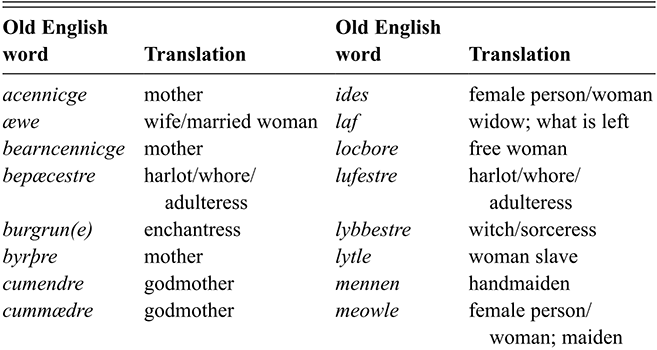

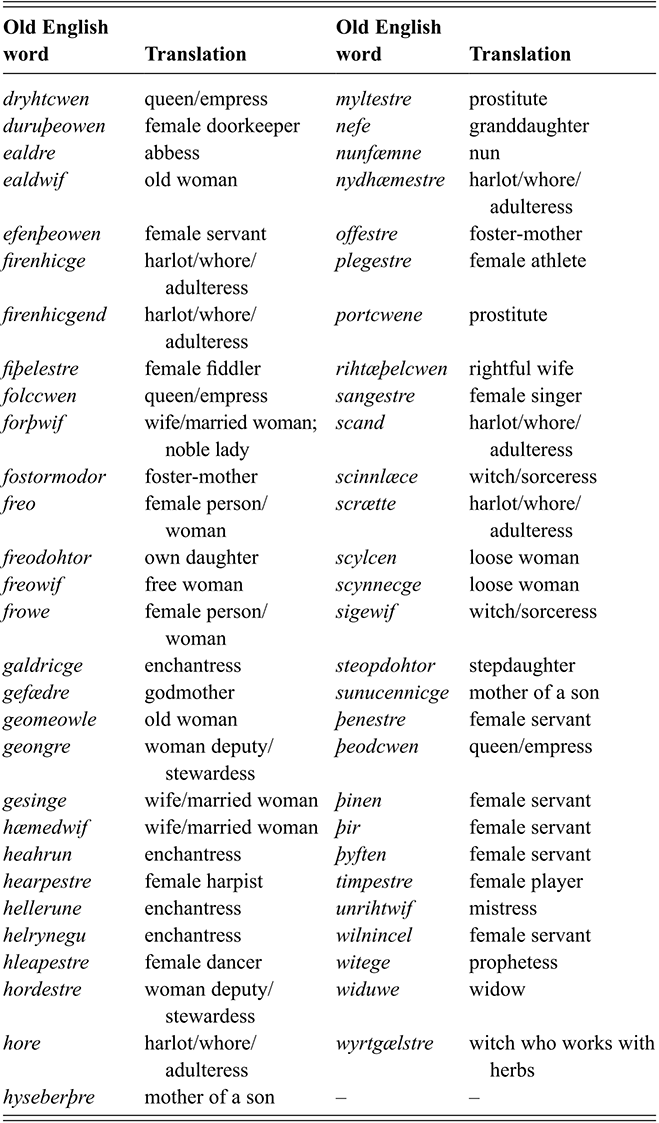

The list of women terms which we checked was much longer, but it turned out that many of the words included in the thesaurus are limited to poetry records or texts not included in YCOE since they are not attested in the corpus. Table 2 presents these items.

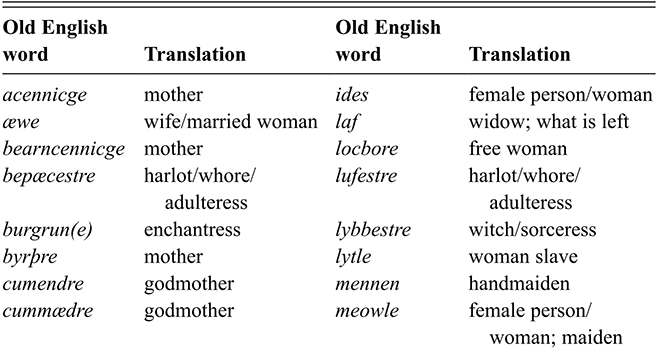

Women terms from A Thesaurus of Old English not attested in YCOE

Table 2aLong description

The table has 2 columns: Old English word and Translation. It reads as follows. Acennicge: mother. Æwe: wife or married woman. Bearncennicge: mother. BepÆcestre: harlot, whore, or adulteress. burgrun(e): enchantress. Byrþre: mother. Cumendre: godmother. CummÆdre: godmother. Ides: female person or woman. Laf: widow; what is left. Locbore: free woman. Lufestre: harlot, whore, or adulteress. Lybbestre: witch or sorceress. Lytle: woman slave. Mennen: handmaiden. Meowle: female person or woman; maiden.

Table 2bLong description

The table has 2 columns: Old English word and Translation. It reads as follows. Dryhtcwen: queen or empress. Duruþeowen: female doorkeeper. Ealdre: abbess. Ealdwif: old woman. Efenþeowen: female servant. Firenhicge: harlot, whore, or adulteress. Firenhicgend: harlot, whore, or adulteress. Fiþelestre: female fiddler. Folccwen: queen or empress. Forþwif: wife or married woman; noble lady. Fostormodor: foster-mother. Freo: female person or woman. Freodohtor: own daughter. Freowif: free woman. Frowe: female person or woman. Galdricge: enchantress. GefÆdre: godmother. Geomeowle: old woman. Geongre: woman deputy or stewardess. Gesinge: wife or married woman. HÆmedwif: wife or married woman. Heahrun: enchantress. Hearpestre: female harpist: hellerune: enchantress. Helrynegu: enchantress. Hleapestre: female dancer. Hordestre: woman deputy or stewardess. Hore: harlot, whore, or adulteress. Hyseberþre: mother of a son.

Myltestre: prostitute. Nefe: granddaughter. NunfÆmne: nun. NydhÆmestre: harlot, whore, or adulteress. Offestre: foster-mother. Plegestre: female athlete. Portcwene: prostitute. RihtÆþelewen: rightful wife: Sangestre: female singer. Scand: harlot, whore, or adulteress. ScinnlÆce: witch or sorceress. ScrÆtte: harlot, whore, or adulteress. Scylcen: loose woman. Scynnecge: loose woman. Sigewif: witch or sorceress. Steopdohtor: stepdaughter. Sunucennicge: mother of a son. þenestre: female servant. þeodcwen: queen or empress. þinen: female servant. þir: female servant. þyften: female servant. Timpestre: female player. Unrihtwif: mistress. Wilnincel: female servant. Witege: prophetess. Widuwe: widow. WyrtgÆlstre: witch who works with herbs.

The only women terms from Table 2 which are potentially present in YCOE for which it is impossible to check it automatically because of their morphological overlap with the equivalent men terms are witege ‘prophetess’ (overlapping with witega ‘prophet’) and widuwe ‘widow’ (overlapping with widuwa ‘widower’). What is more, the primary sense of the word laf is ‘what is left’, and only the secondary meaning is ‘widow (f)’. Since it would be impossible to tell the difference without manual inspection in context, the word was discarded. Finally, despite its high frequency, the word mægþ had to be eliminated from the dataset since its secondary sense – that is, ‘family’ – turned out to be dominant in the data and the lexeme failed to appear in collocations reflecting its primary sense ‘maiden, girl’.

Table 3 presents the final selection of female-gendered nouns with the male-gendered terms chosen on the basis of their semantic equivalence.Footnote 4 The numbers in brackets represent corpus frequencies of the terms. We decided to set the frequency threshold at fifty (which makes nunne ‘nun’ with the frequency of fifty-two the least frequent item in the dataset) since less frequent terms failed to render a substantial number of recurrent collocations in VARIOE.

| Word group | Female-gendered terms | Equivalent male-gendered terms |

|---|---|---|

| general terms | wif ‘woman’ (1,404), fæmne ‘woman, girl, maiden’ (313) wifmann ‘woman, female servant’ (118) | wer ‘man’ (1,732) |

| parent | modor ‘mother’ (530) | fæder ‘father’ (2,162) |

| child | mægden ‘girl, maiden’ (430), dohtor ‘daughter’ (380) | sunu ‘son’ (1,889), cnapa ‘boy, servant’ (152) |

| sibling | sweostor ‘sister, nun’ (190) | broþor ‘brother, monk’ (1,281) |

| person with a higher social position | cwen ‘queen, noblewoman’ (172), hlæfdige ‘lady, noblewoman’ (60), abbodesse ‘abbess’ (69), nunne ‘nun’ (52) | cyning ‘king’ (4,599), hlaford ‘lord’ (754), abbod ‘abbot’ (575), munuc ‘monk’ (442) |

As shown in Table 3, the terms were grouped into five main categories (some of which are represented by single nouns): general terms, parents, children/young adults, siblings and people of higher social status. The last group is most varied but we wanted to see how social position interacts with gender in the Anglo-Saxon context, and the results (cf. Sections 3.1.5, 3.3.5, 4.1.5 and 4.2.5) show that this particular category is really interesting.

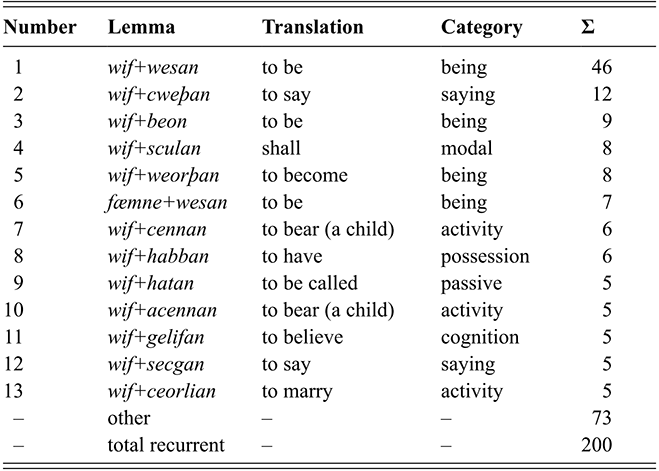

The recently released VARIOE dictionary of OE collocations (Pęzik & Cichosz, Reference Pęzik and Cichosz2021), which was the primary tool used for the research presented in this Element, is based on lemmatised YCOE data – that is, every word form in the corpus was aligned to its base form, which for nouns means the singular nominative form with the dominant spelling. This is a prerequisite of any phraseological study since OE, as an inflected language, uses a great variety of morphological forms for nouns, adjectives, pronouns and verbs. Moreover, without a spelling standard, the lexemes may appear in many different spelling forms, which increases the variation and makes lemmatisation even more important because without it, it would be impossible to perform any kind of automated searches of recurrent collocations.Footnote 5 In addition, OE inflections allowed for a relatively flexible sentence structure and a collocation does not necessarily follow a fixed word order – for example, an adjective could both precede and follow a noun, an object could be placed both before and after a lexical verb, etcetera. VARIOE takes this flexibility into consideration, searching for a given part of speech in close proximity to another one, allowing for intervening phrases and changes in relative order.Footnote 6 The collocation patterns offered by VARIOE that we have decided to use are:

ADJ + N: an adjective preceding or following a noun (irrespective of case, with some intervening elements possible), for example, (se) halga gast ‘(the) holy ghost’

GEN + N: a genitive noun in close proximity to a head noun (irrespective of case, with intervening elements possible), for example, Godes gast ‘God’s spirit’

N + CONJ + N: two nouns linked by a conjunction (irrespective of case, with some intervening elements possible), for example, dæg and niht ‘day and night’

V + N: a verb form (finite or non-finite) in close proximity to a noun in the dative, accusative or genitive case (with some intervening elements possible), for example, lufian God ‘to love God’

N + V: a noun in the nominative case in close proximity to a verb form (finite or non-finite) (with some intervening elements possible), for example, God cwæð ‘God said’.

Since recurrent patterns returned by VARIOE are based on linear co-occurrence, some of the results are linguistic noise that needs to be filtered out. Thus each collocation had to be inspected in context, and on the basis of the analysis of examples we decided whether a given pair of words may indeed be treated as a collocational pattern.Footnote 7 All the data shown in Sections 3 and 4 underwent this clean-up operation and the results can reliably be treated as fully-fledged collocations of the gendered OE nouns analysed in this Element. In the analysis we focus on recurrent patterns – that is, for a collocation to qualify for further processing, it needed to appear at least twice in the YCOE corpus.

The analysis is illustrated with numbered YCOE corpus examples. Following the Leipzig glossing rules, the first line of each example is the original OE text, the second line provides a word-by-word gloss, while the third line is an idiomatic present-day English translation. Every example contains a YCOE identifier, which shows the text file name, for example, cobede for Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, and the numbers indicating the precise location of the fragment in the OE manuscript.

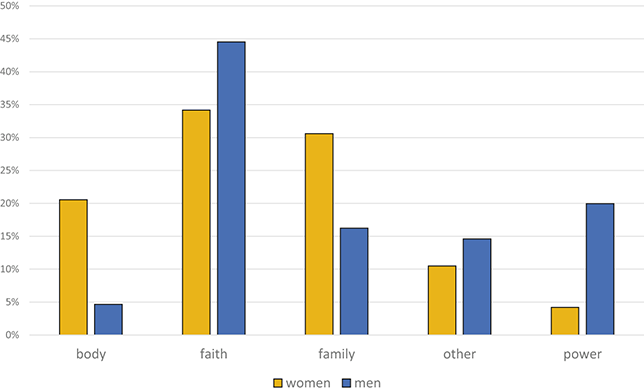

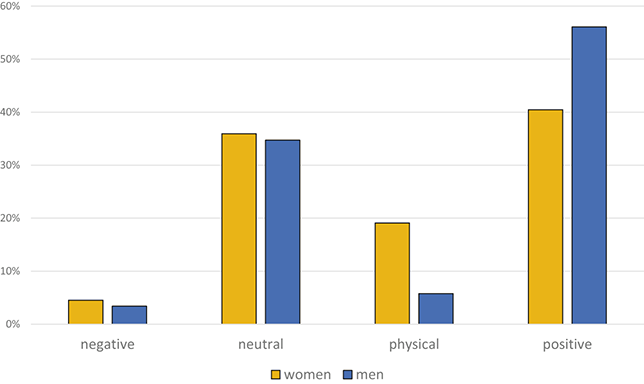

During the analysis, all of the identified collocations were subjected to a simple semantic analysis in order to identify the main tendencies in the data. In the case of adjectives, the lexemes were divided into positive (indicating an objectively positive trait of a person in the early medieval Christian context, such as good, pious or law-abiding), negative (indicating an objectively negative trace of character, such as cruel, evil or dishonest), physical (related to physicality and general appearance, such as beautiful, old or pregnant) and neutral (including quantifier-like adjectives such as other, same or next, indicating other features such as ethnicity, religious denomination, social position, financial situation, e.g. Hebrew or poor, as well as any adjective nor fitting the other categories, e.g. eternal).

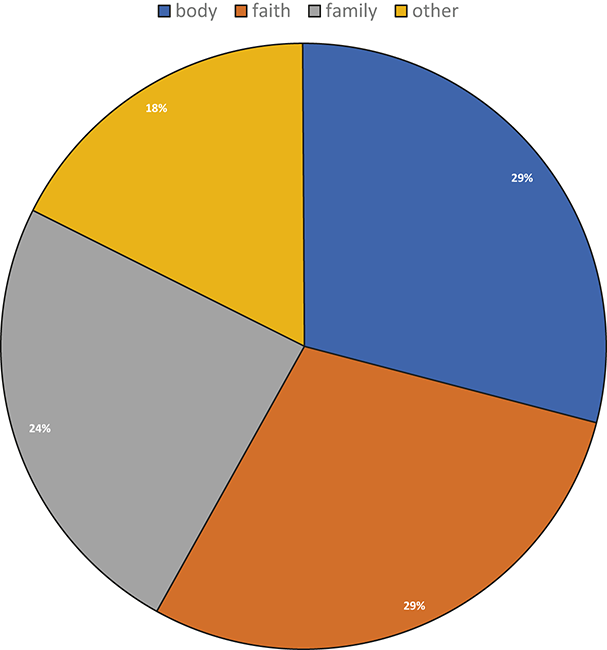

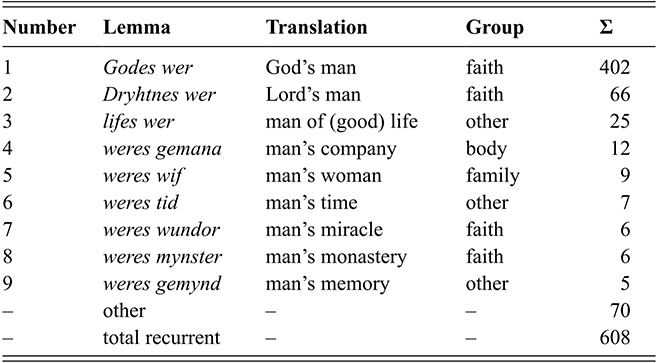

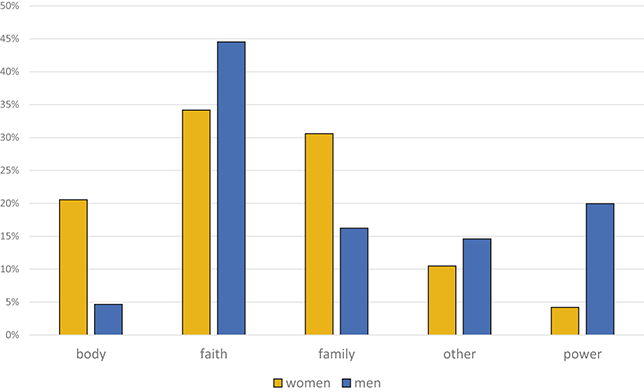

The genitival modifiers were also divided into a few semantic groups based around family (indicating all sorts of family relations, e.g. someone’s wife, brother or child), faith (centred around God or the Catholic Church, e.g. God’s woman, abbess of the monastery), body (parts of the body or inner organs, e.g. someone’s eyes, heart or blood) and power (describing someone’s authority in the form of orders, possession, servants or office), with ‘other’ as the category covering all the remaining semantic fields.

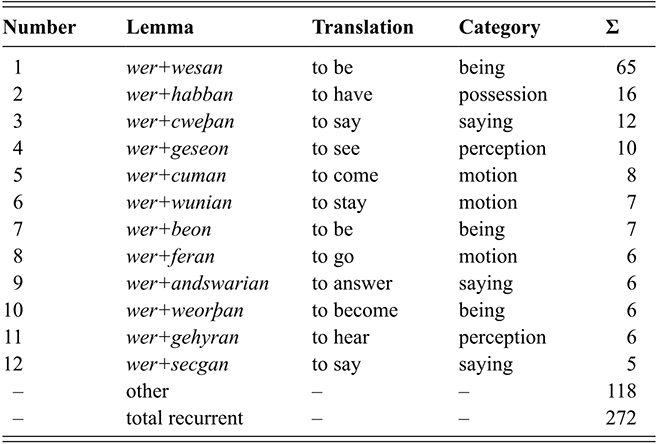

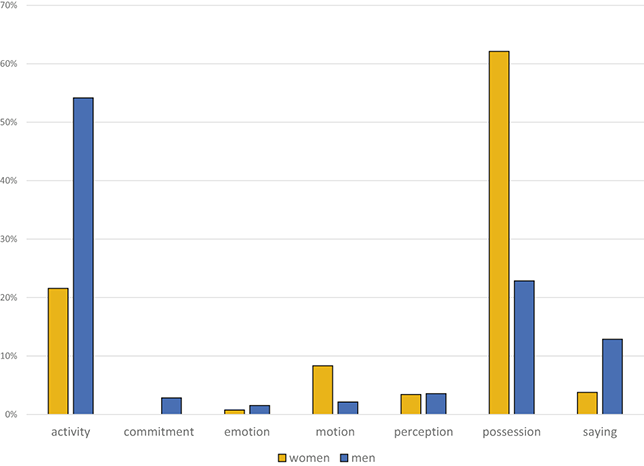

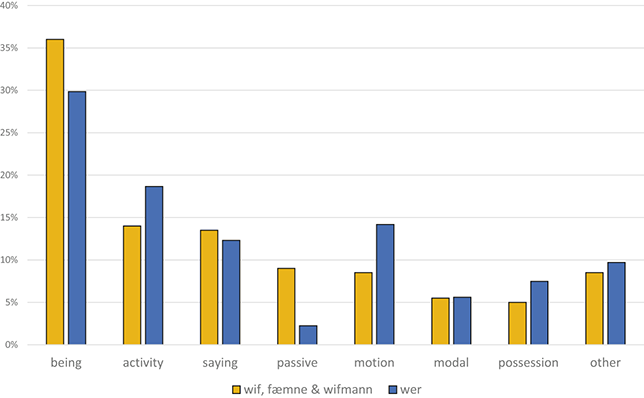

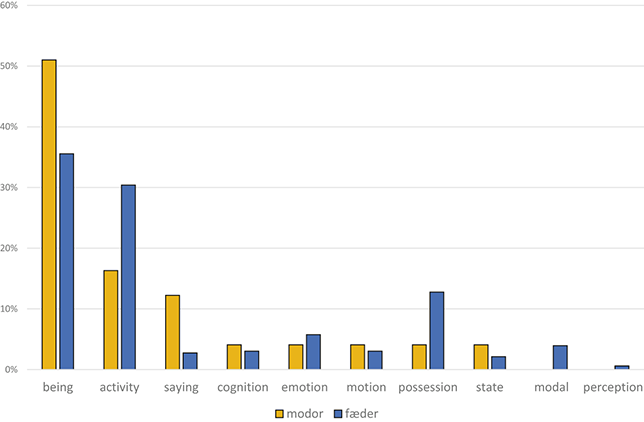

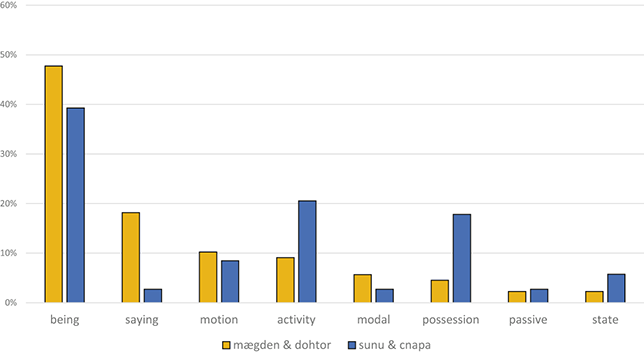

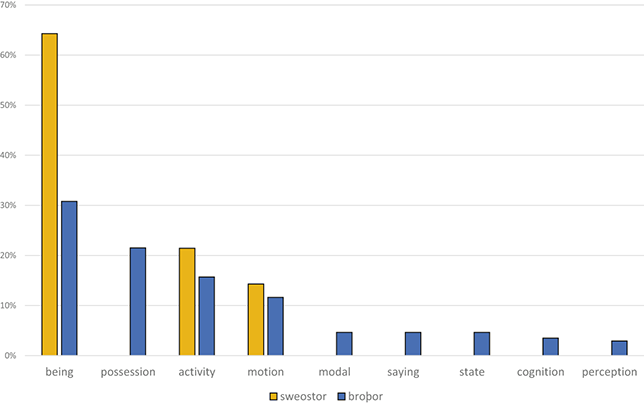

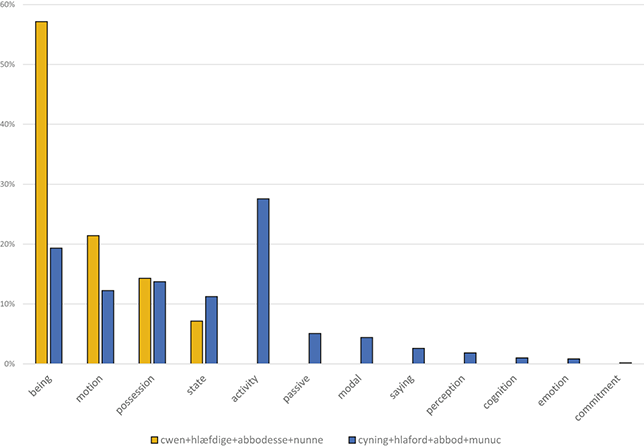

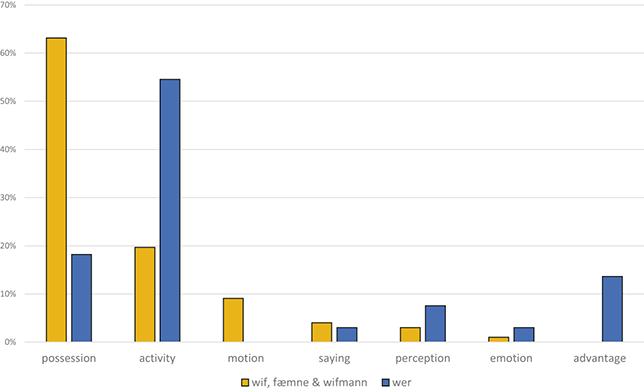

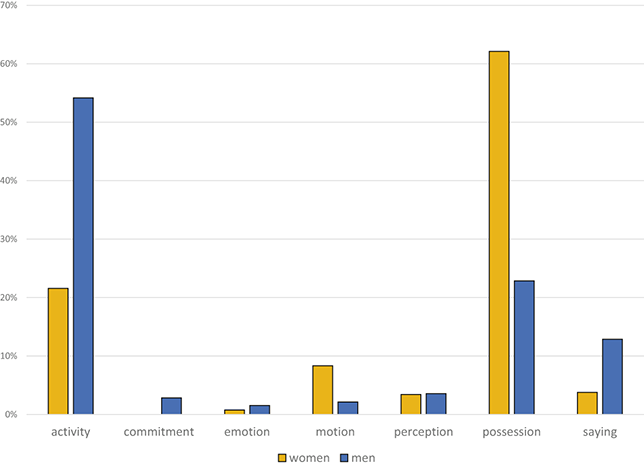

In the case of verb-based collocations, both with subjects and objects, the classification relies on the verb and includes some basic categories such as being (to be, to become), saying (to speak, to answer), possession (both as a stable state, e.g. to have, to own, and the process of transfer, e.g. to give), state (both stable, e.g. to live, and the process of change, e.g. to grow, to die), motion (to go, to leave, to sit down), cognition (to think, to understand), perception (to see, to hear), emotion (to love, to hate) or commitment (to promise, to swear), as well as verbs in the passive voice and modal verbs.

All the tables provide frequency (total number of attestations in the corpus), though for reasons of clarity, in most tables only the data above a certain frequency threshold are presented, which is clearly indicated in the table captions. However, the analysis takes all the recurrent collocations into account, and all the figures presented in Sections 3 and 4 are based on the complete dataset.

3 Collocations on the Level of the Noun Phrase

3.1 Adjectival Modifiers (A + N and N + A)

3.1.1 General Nouns

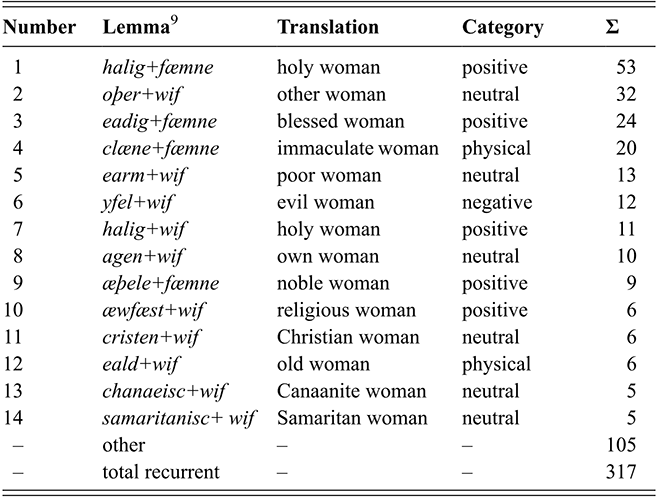

The first category of collocations that we extracted from the YCOE corpus are recurrent adjective + noun combinations. In the case of the basic woman terms – that is, wif, fæmne and wifmann – there are 52 recurrent collocations of this type, amounting to 317 tokens in total (see table 4), which we classified as neutral, positive, negative or physical, according to the methodology presented in Section 2.

| Number | LemmaFootnote 9 | Translation | Category | Σ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | halig+fæmne | holy woman | positive | 53 |

| 2 | oþer+wif | other woman | neutral | 32 |

| 3 | eadig+fæmne | blessed woman | positive | 24 |

| 4 | clæne+fæmne | immaculate woman | physical | 20 |

| 5 | earm+wif | poor woman | neutral | 13 |

| 6 | yfel+wif | evil woman | negative | 12 |

| 7 | halig+wif | holy woman | positive | 11 |

| 8 | agen+wif | own woman | neutral | 10 |

| 9 | æþele+fæmne | noble woman | positive | 9 |

| 10 | æwfæst+wif | religious woman | positive | 6 |

| 11 | cristen+wif | Christian woman | neutral | 6 |

| 12 | eald+wif | old woman | physical | 6 |

| 13 | chanaeisc+wif | Canaanite woman | neutral | 5 |

| 14 | samaritanisc+ wif | Samaritan woman | neutral | 5 |

| – | other | – | – | 105 |

| – | total recurrent | – | – | 317 |

It is interesting to note that among the most frequent collocations there is one extremely negative (yfel ‘evil’) and one extremely positive (halig ‘holy’), as illustrated by (1) and (2).

(1)

Eornostlice nis nan wyrmcynn. ne wildeora cyn. truly not-is no snake-kind nor wild-animal kind on yfelnysse gelic yfelum wife on evilness similar evil woman ‘Truly, there is no kind of snake or wild animal similar in their evilness to an evil woman.’ (cocathom1,+ACHom_I,_32:457.186.6500)

(2)

Ðæt on Berccingum þam mynstre mid heofonlice leohte that on Berching the monastery with heavenly light getacnod wæs, hwær gesette beon sceoldon þa lichaman shown was where placed be should the bodies haligra fæmnena. holy.GEN women.GEN ‘How heavenly light showed the place where the bodies of holy women should be buried in the Berching monastery.’ (cobede,BedeHead:4.18.15.90)

Next, it should be indicated that there is a relatively high proportion of adjectives describing physicality, many of which are related to a woman’s ability or inability to bear children: clæne ‘clean, pure, immaculate’, eald ‘old’, blind ‘blind’,Footnote 10 bearneaca ‘pregnant, big with child’, dead ‘dead’, bearneacnigende ‘pregnant, child-carrying’, unwæstmbære ‘sterile’, untimende ‘barren’, fæger ‘fair, beautiful’, as illustrated in (3). It is noteworthy that the concern with female physicality focuses on nothing else but women’s reproductive potential.

(3)

and æfter þam Boclican regole, ne sceolde nan man and after the biblical rule not should no man bearneacnigendum wife genealæcan, Ne monoðseocum, ne þam pregnant woman approach nor month-sick nor this ðe for ylde untymende byð. that for age barren is ‘And according to the Bible, no man should have sexual intercourse with a pregnant woman or a menstruating one, or the one who is barren because of old age.’ (coaelhom,+AHom_20:111.2991)

Moreover, a few adjectives apart from yfel ‘evil’ are clearly negative – that is, synfull ‘sinful,’ deofolseoc ‘devil-sick’, ungeleafull ‘unbelieving’, see (4) – while the positive ones are related to a woman’s obedience to the rules and the regulations of the Christian faith: halig ‘holy’, arwurþ ‘honourable’, æwfæst ‘pious’, geleafful ‘righteous’, god ‘good’, æw ‘lawful’, æþele ‘noble’. The negative adjectives, then, relate mostly to a woman’s deviation from faith and her consequent iniquities, while the positive ones are very broad in meaning and they do not reveal much about the qualities of the woman’s character or about her skills, as in (5).

(4)

Ac wite þu man Þæt ic eom synful wif but know you man that I am sinful woman ‘But you should know, man, that I am a sinful woman.’ (comary,LS_23_[MaryofEgypt]:284.191)

(5)

Þa wiston hi, þæt þær neah wunode sum eawfæst Then knew they that there near lived some pious wif. woman ‘Then they learned that a pious woman lived nearby.’ (cogregdH,GD_2_[H]:12.126.25.1205)

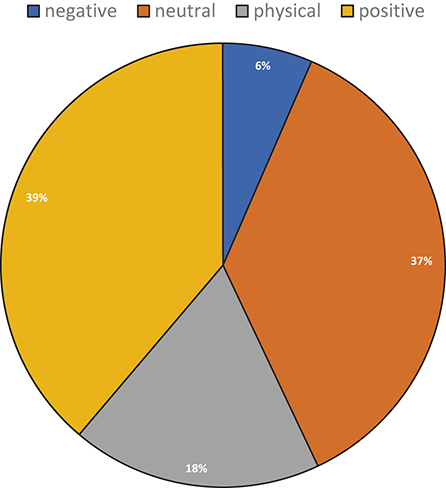

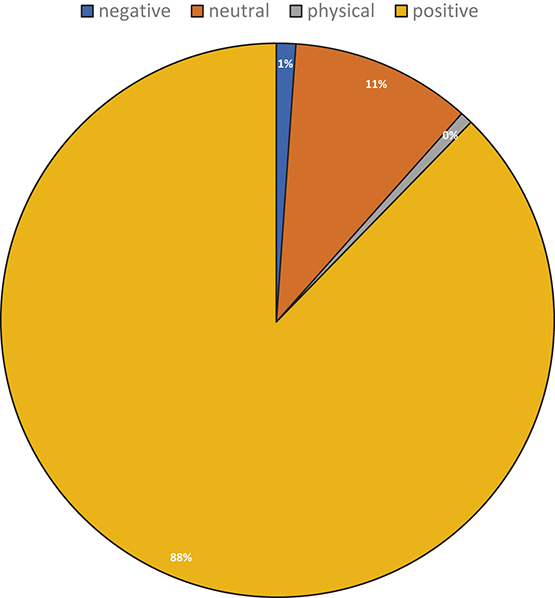

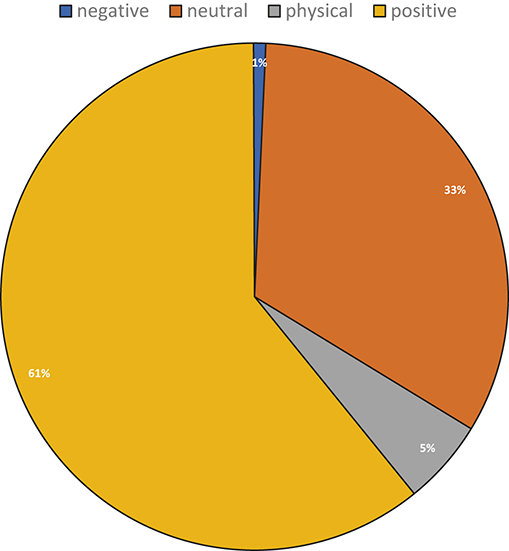

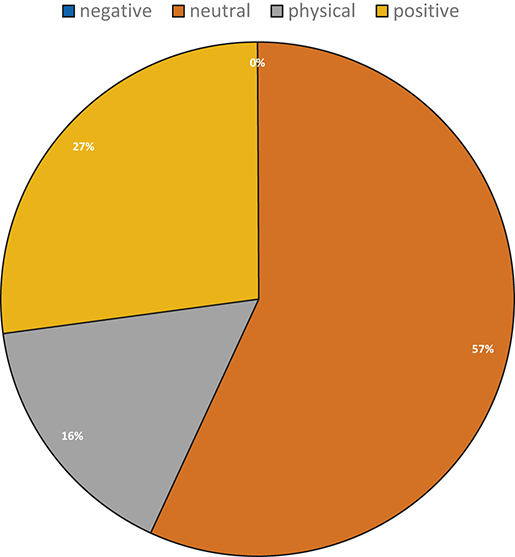

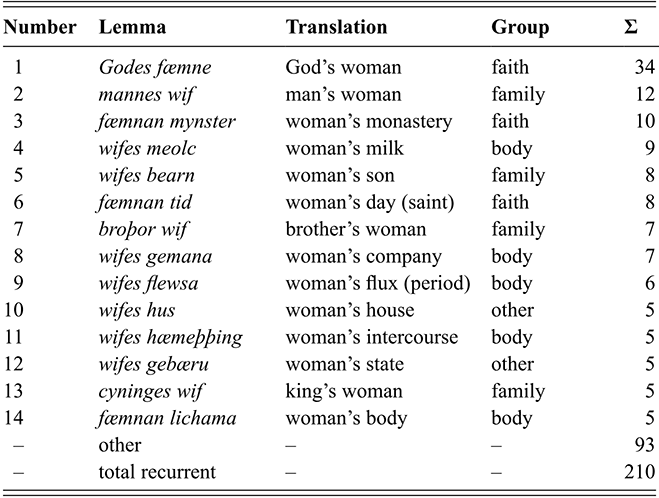

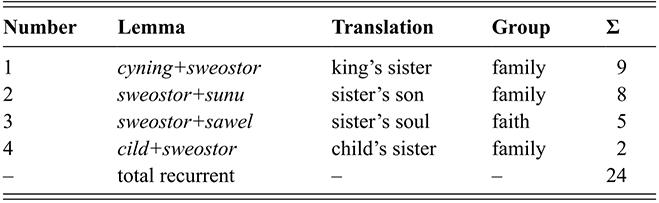

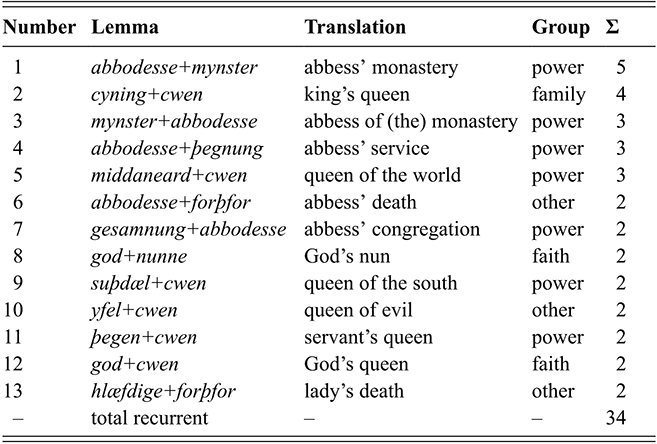

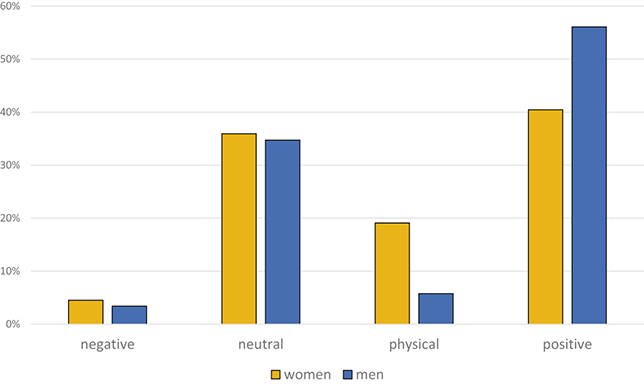

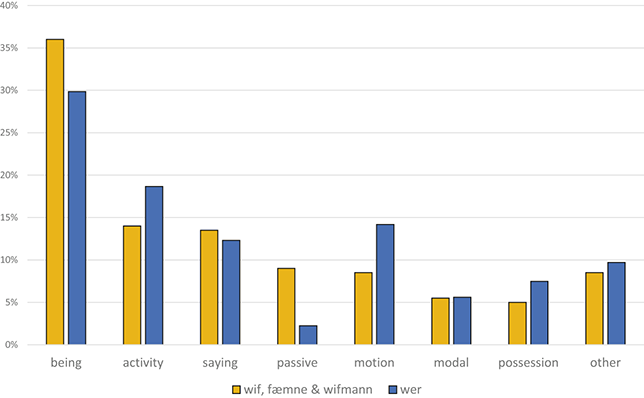

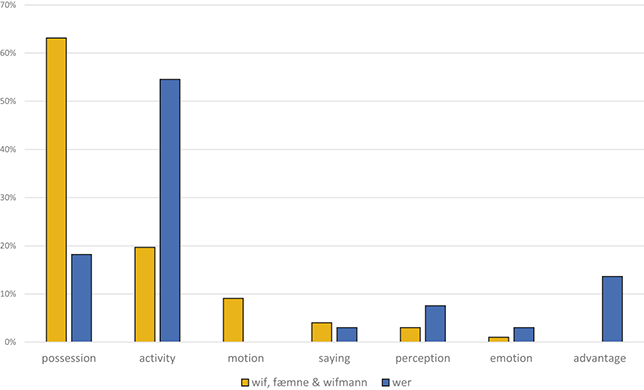

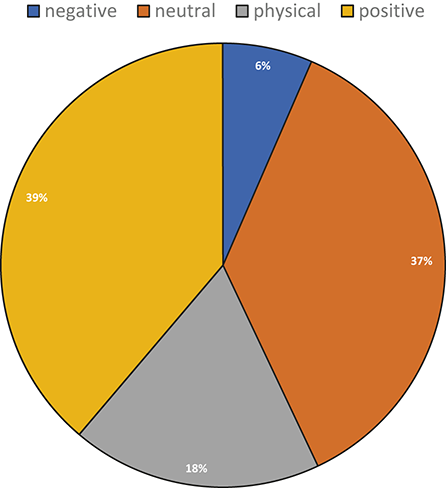

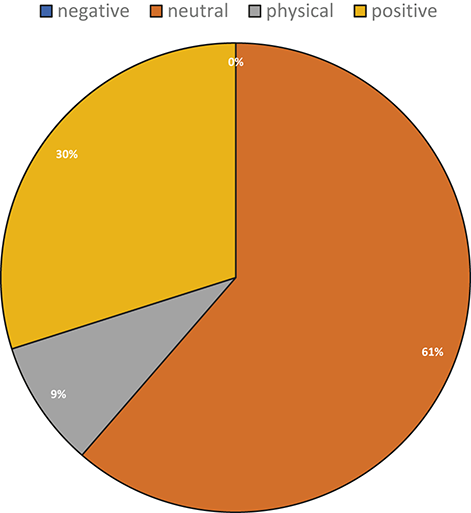

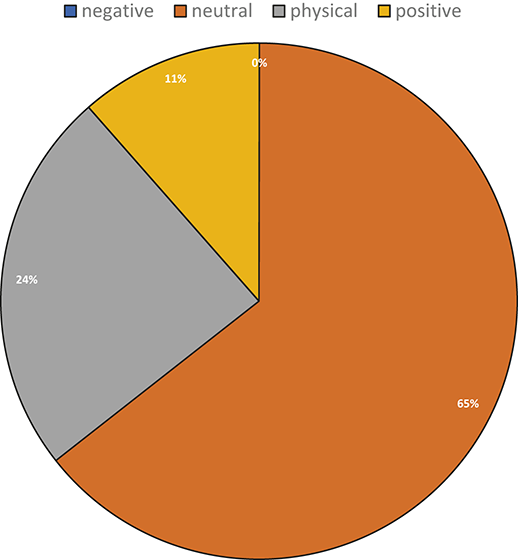

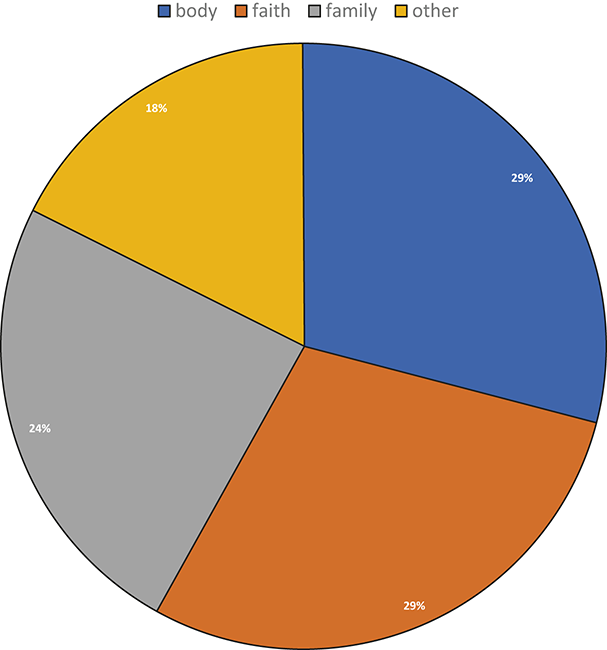

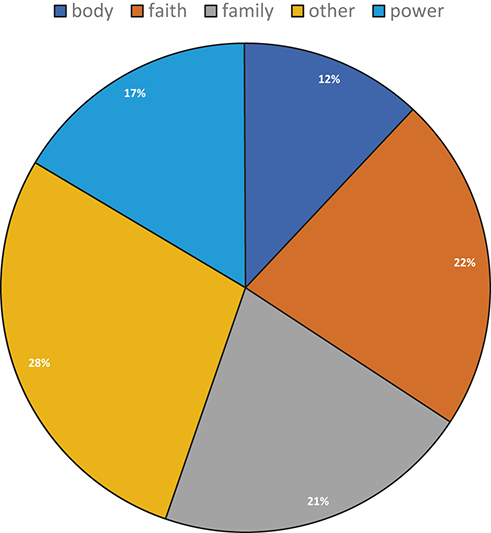

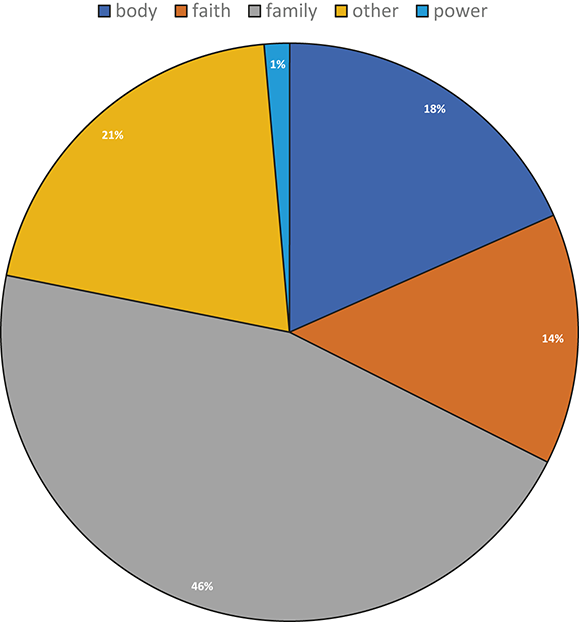

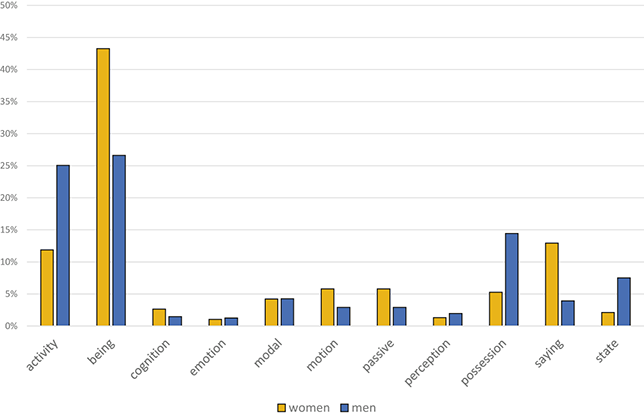

All in all, the majority of adjectives used to describe wif ‘woman’ are positive or neutral in meaning (39 per cent and 37 per cent respectively), 6 per cent are negative, while as many as 18 per cent are related to the woman’s physicality (cf. Figure 1). By contrast, the collocations of wer ‘man’ are predominantly positive, as shown in Table 5 and illustrated with (6).

(6)

Mine gebroðra. we rædað nu æt Godes ðenungum my brothers we read now at God’s service be ðan eadigan were IOB. about the blessed man Job ‘My brothers, during the God’s service we will read about the blessed man Job.’ (cocathom2,+ACHom_II,_35:260.1.5801)

Figure 1 Semantic categories of recurrent adjectival collocates of wif, fæmne and wifmann ‘woman’ in YCOE.

| Number | Lemma | Translation | Category | Σ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | halig+wer | holy man | positive | 453 |

| 2 | arwurþ+wer | honourable man | positive | 144 |

| 3 | eadig+wer | blessed man | positive | 54 |

| 4 | ilca+wer | same man | neutral | 39 |

| 5 | æþele+wer | noble man | positive | 28 |

| 6 | god+wer | good man | positive | 26 |

| 7 | æwfæst+wer | pious man | positive | 21 |

| 8 | oþer+wer | other man | neutral | 17 |

| 9 | mære+wer | great man | positive | 15 |

| 10 | æfæst+wer | pious man | positive | 11 |

| 11 | geleafful+wer | faithful man | positive | 10 |

| 12 | hæþen+wer | heathen man | neutral | 8 |

| 13 | swilc+wer | such man | neutral | 7 |

| 14 | rihtwis+wer | righteous man | positive | 7 |

| 15 | agen+wer | (sb’s) own man | neutral | 5 |

| 16 | beorht+wer | glorious man | positive | 5 |

| 17 | apostolic+wer | apostolic man | neutral | 5 |

| 18 | geþyldig+wer | patient man | positive | 5 |

| – | other | – | – | 60 |

| – | all recurrent | – | – | 920 |

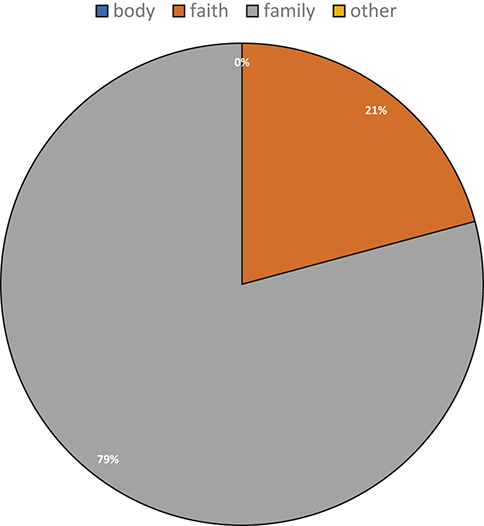

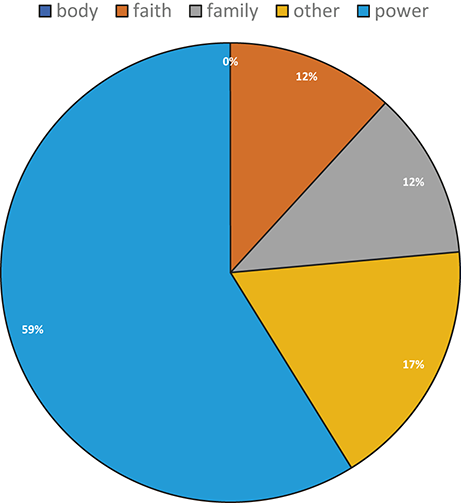

Apart from the dominance of adjectives with clearly positive connotations, the list notably lacks any lexemes describing a man’s physicality. The only two exceptions are strang ‘strong’ and eald ‘old’, both extremely rare considering the generally high frequency of wer in the corpus, and neither of them referring to a man’s sexuality, unlike the adjectives collocating with the women terms. Moreover, negatively connotating adjectives are also practically absent from the study sample, with blodig ‘cruel’ and unrihtwis ‘unrighteous’ representing this rare pattern. Interestingly, two out of these four infrequent collocations – that is, strang ‘strong’ and blodig ‘cruel’ – have connotations befitting the stipulated warrior’s position and signalling power and hardness, cf. (7) and (8). Such instances are not attested with women terms.

(7)

Ða synd blodige weras ðe wyrcað manslihtas, and ða these are cruel men who do man-slaughters and these ðe manna sawla beswicað to forwyrde. that men’s souls lead to destruction ‘These are cruel men who commit murder and these who lead people’s souls to destruction.’

(coaelive,+ALS[Pr_Moses]:305.3038)

(8)

Þæt wæron strange weras ond sigefæste on woroldgefeohtum that were strong men and victorious in world-fights ‘These were strong men, victorious in worldly fights.’ (comart3,Mart_5_[Kotzor]:Ma9,A.3.326)

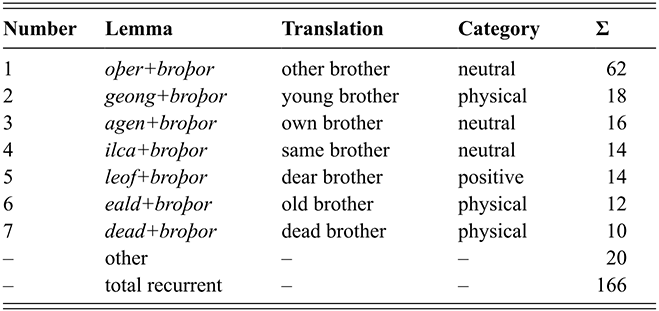

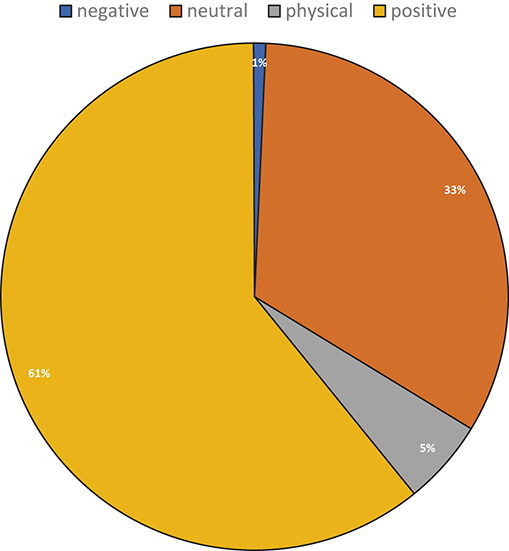

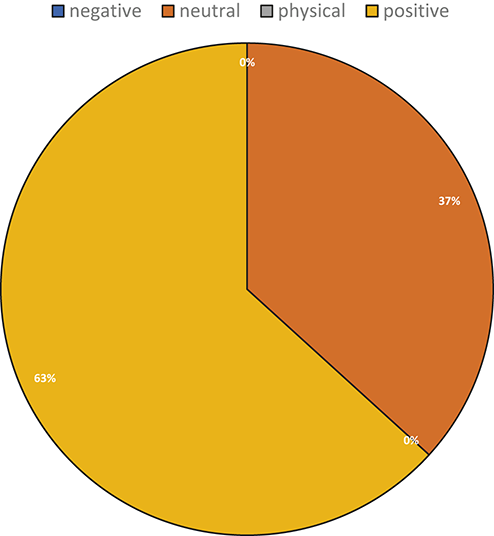

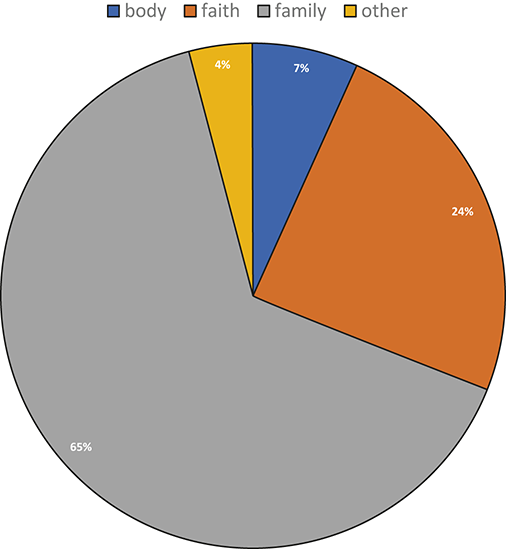

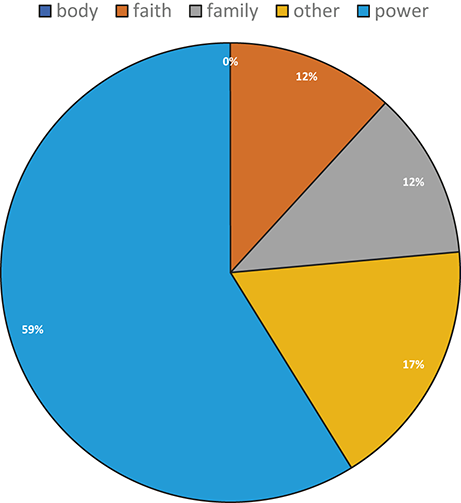

All in all, as shown in Figure 2, the adjectival collocates of wer are predominantly positive, and the difference between the analysed terms is really striking. As can been seen, then, the comparison of adjectival collocates of general OE terms describing women and men shows a significant difference in the linguistic image of both sexes. Men are mostly described in unreservedly positive terms, and even if not, the focus remains on their warrior qualities. Women, in contrast, are frequently valued in (morally) negative terms. An interesting group of collocates consists of adjectives related to the body, which in the Christian tradition is perceived as an imperfect part of a human being and a source of corruption; the particular sphere of interest is the reproductive capability, which signals the instrumental quality of the woman.

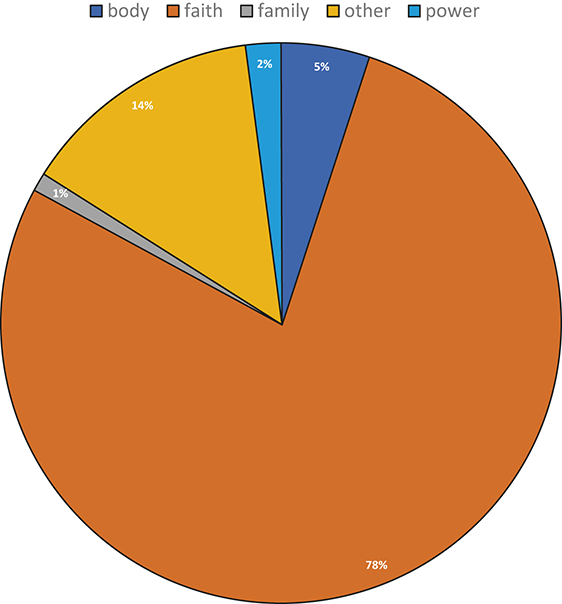

Figure 2 Semantic categories of recurrent adjectival collocates of wer ‘man’ in YCOE.

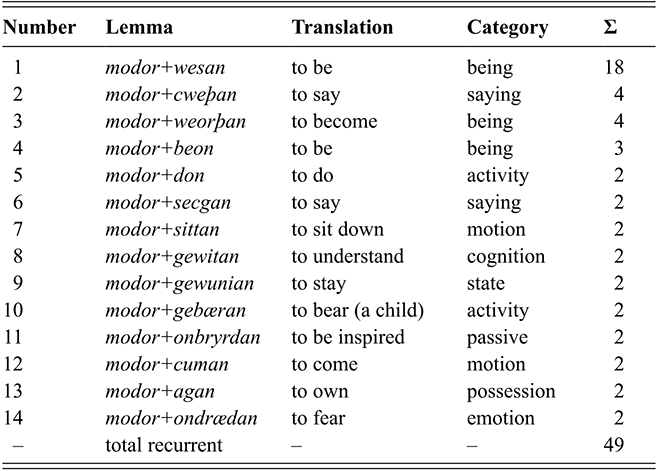

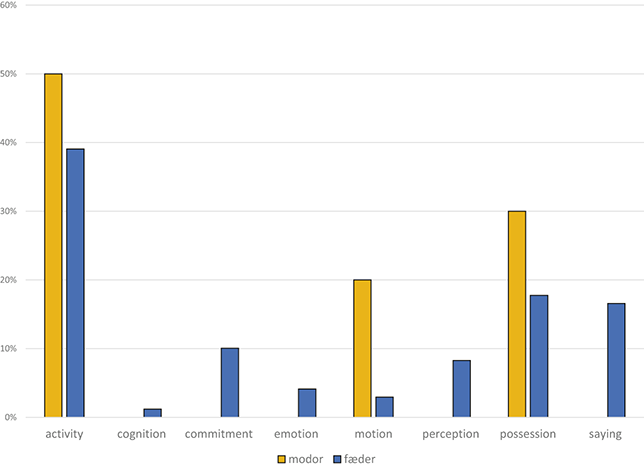

3.1.2 Parent Terms

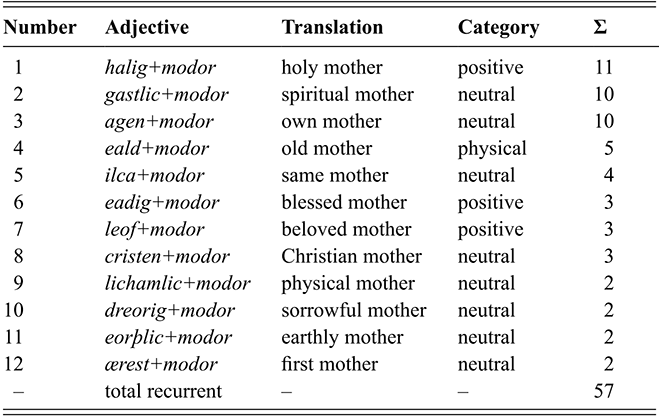

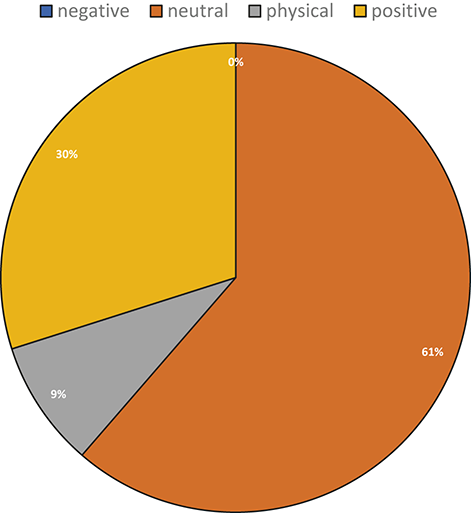

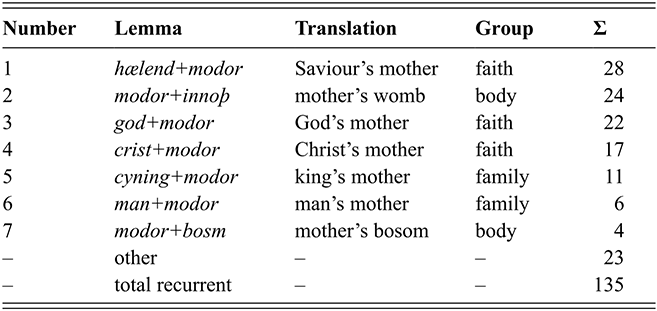

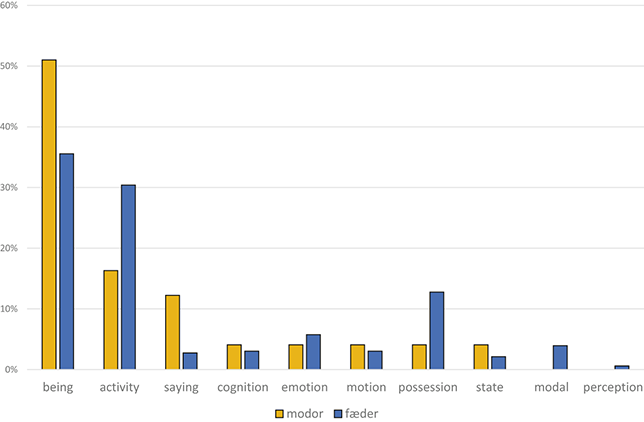

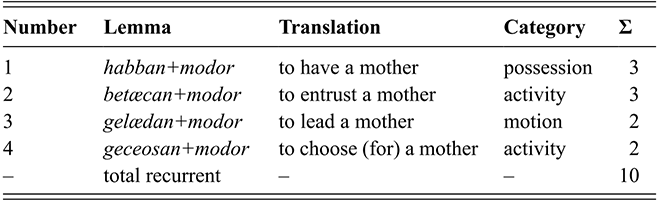

The next gendered noun pair in the analysis is modor ‘mother’ and fæder ‘father’. Table 6 reveals that in the case of the former, adjectival collocations are not very numerous. What is more, many instances of modor are in fact references to Mary, the mother of Christ, which includes all the occurrences of halig ‘holy’ and eadig ‘blessed’, as in (9).

(9)

Seo halige moder Maria þa afedde þæt cyld mid micelre the holy mother Mary then fed the child with great arwyrðnysse. reverence ‘The holy mother Mary then fed the child with great reverence.’ (cocathom1,+ACHom_I,_1:187.246.258)

What is more, the spiritual mother (gastlice modor), which is the second most frequent adjectival collocation in Table 6, is actually a metaphor denoting the Catholic Church (cf. (10)).

(10)

Ealle we habbað ænne heofonlicne fæder and ane gastlice oh we have one heavenly father and one spiritual modor, seo is ecclesia genamod, þæt is mother that is ecclesia called that is Godes cirice, and þa we sculon æfre lufian and wurðian. God’s church and these we should always love and honour ‘Indeed we have a heavenly father and a spiritual mother called ecclesia, which means God’s church, and we should always love and honour them.’ (coinspolD,WPol_2.1.2_[Jost]:99.140)

The most frequent reference to physicality is the adjective eald ‘old’, though in two cases the referent is Eve, the mother of all people, as in (11).

(11)

Ure ealde moder Eua us beleac heofenan rices our old mother Eve us locked heaven kingdom geat. gate ‘Our old (original) mother Eve locked the door to the kingdom of heaven for us.’ (cocathom2,+ACHom_II,_1:11.295.244)

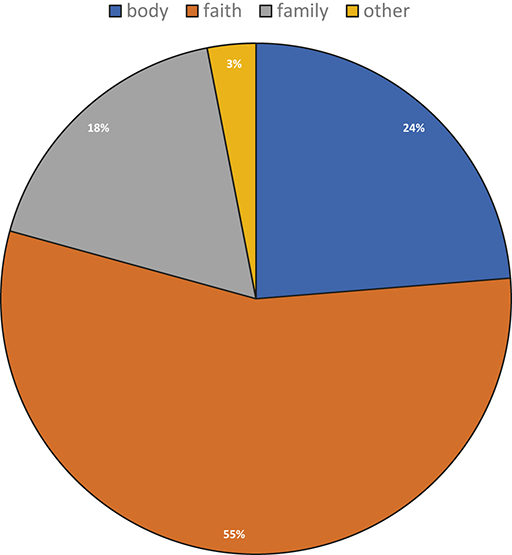

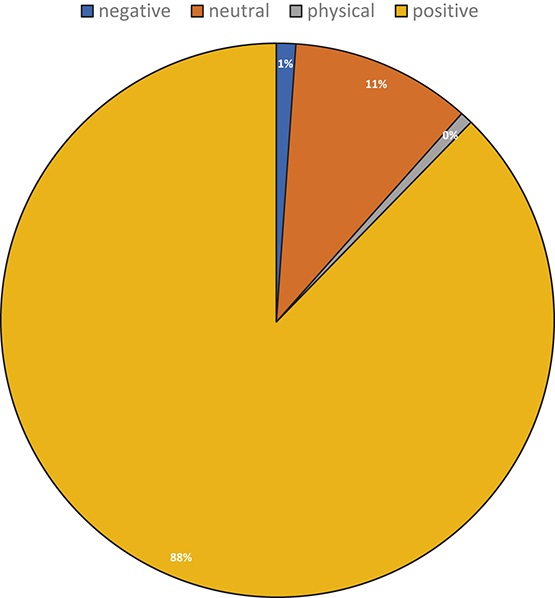

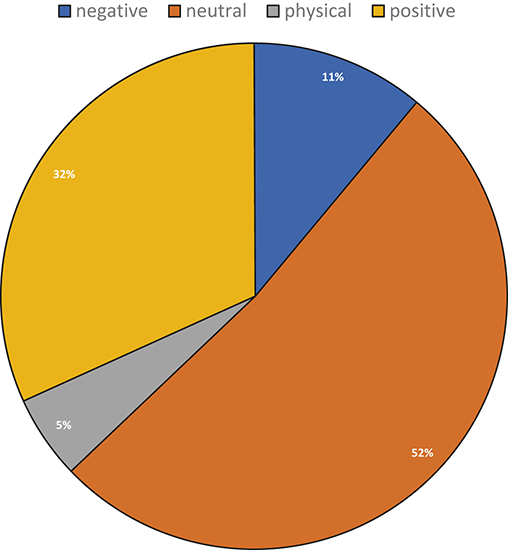

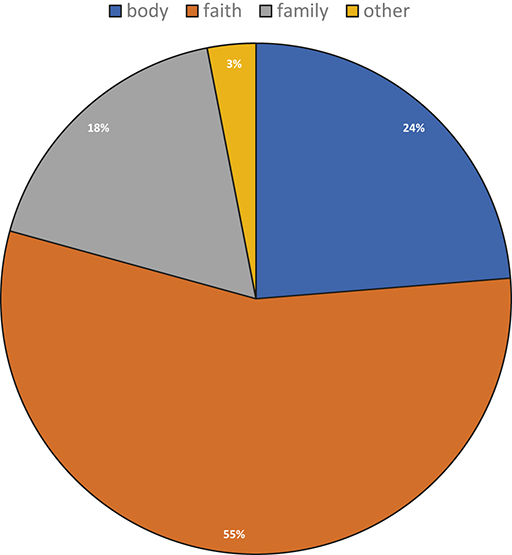

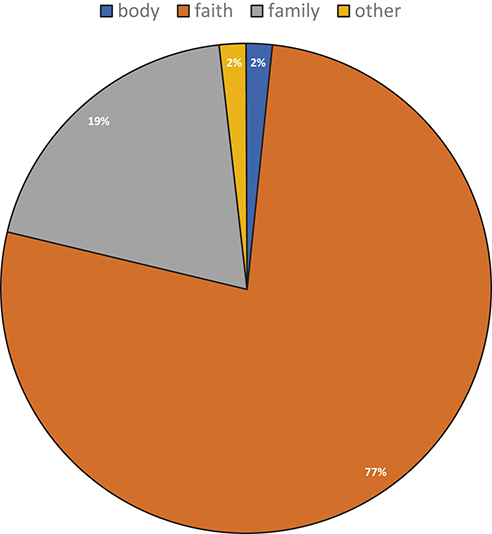

Figure 3 shows that the distribution of collocation types for modor is drastically different from the one obserwed in wer (Figure 2) since the proportion of positive collocations is almost three times lower (30 per cent vs. 88 per cent). Compared to the general women terms shown in Figure 1, there is a visibly lower proportion of physical collocations, which is clearly the result of the strong presence of St. Mary in this category. Naturally, the linguistic image of the mother of Christ does not concentrate on her body. (However, as later analysis will show, the corpus contains references to her womb.)

| Number | Adjective | Translation | Category | Σ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | halig+modor | holy mother | positive | 11 |

| 2 | gastlic+modor | spiritual mother | neutral | 10 |

| 3 | agen+modor | own mother | neutral | 10 |

| 4 | eald+modor | old mother | physical | 5 |

| 5 | ilca+modor | same mother | neutral | 4 |

| 6 | eadig+modor | blessed mother | positive | 3 |

| 7 | leof+modor | beloved mother | positive | 3 |

| 8 | cristen+modor | Christian mother | neutral | 3 |

| 9 | lichamlic+modor | physical mother | neutral | 2 |

| 10 | dreorig+modor | sorrowful mother | neutral | 2 |

| 11 | eorþlic+modor | earthly mother | neutral | 2 |

| 12 | ærest+modor | first mother | neutral | 2 |

| – | total recurrent | – | – | 57 |

Figure 3 Semantic categories of recurrent adjectival collocates of modor ‘mother’ in YCOE.

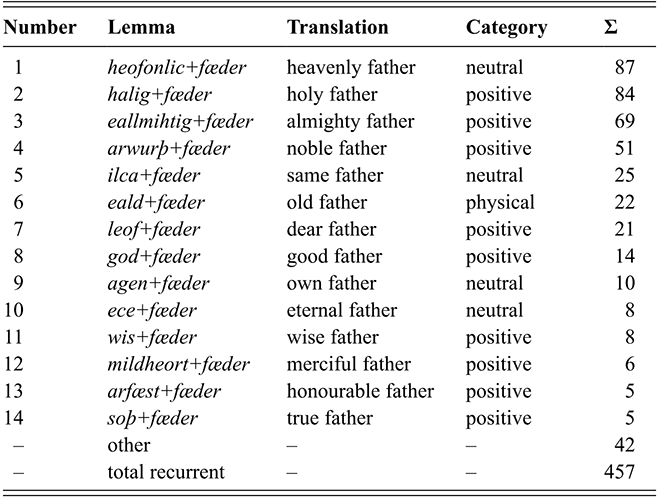

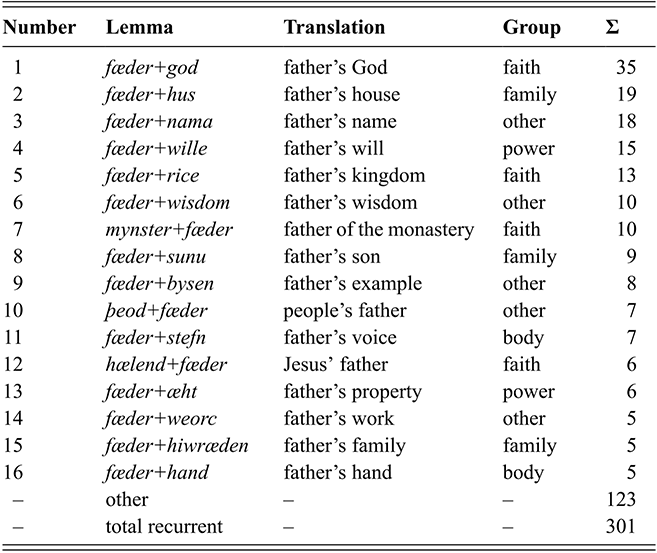

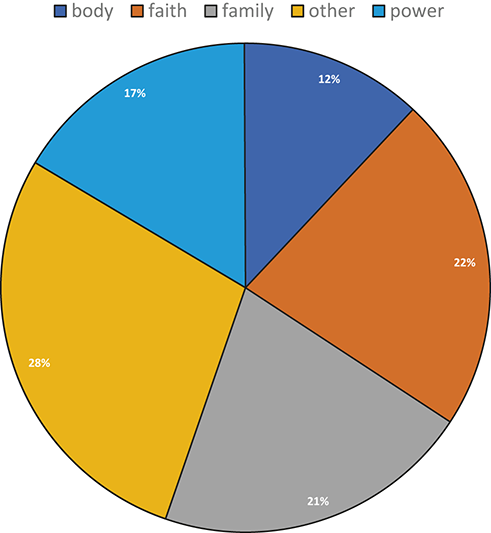

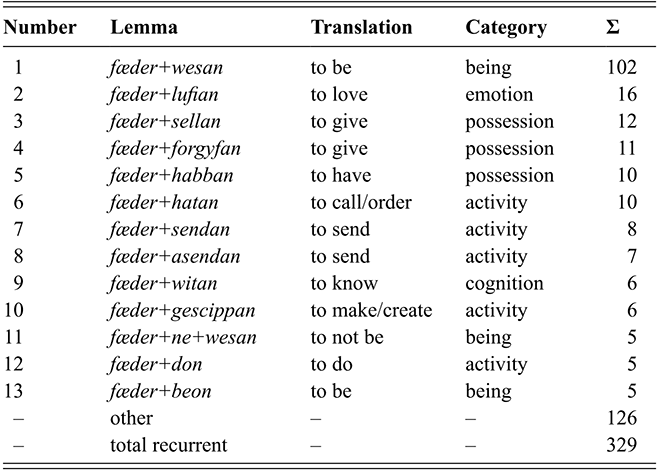

As far as fæder ‘father’ is concerned, the most striking observation is the high frequency of the analysed pattern compared to modor (457 vs. 57 recurrent collocations).

Table 7 shows quite clearly that many of these are references to God, the father of all people, described as holy, almighty and eternal (cf. (12))

(12)

Crist is ancenned Sunu of þam ælmihtigan Fæder; Christ is only begotten son of the almighty father ‘Christ is the only begotten son of the almighty Father.’ (coaelhom,+AHom_1:386.199)

Interestingly, the phrase leof fæder (‘dear father’) is often a vocative phrase directed at God, as in (13).

(13)

leof fæder, we geanbidodon, þæt þu come, swa swa þu dear father we waited that you come so as you behete … promised ‘Dear Father, we waited for you to come as you promised … ’ (cogregdH,GD_2_[H]:22.148.24.1463)

In (14) eald ‘old’ refers to (numerous) male ancestors: this marks a difference to the collocation eald modor ‘old mother’, which usually refers to Eve, as in (11). Apparently, collectively understood familial ancestry is conceptualised only in paternal terms.

(14)

Hwæt hit is gesæd ðæt ure ealdan fæderas wæron what it is said that our old fathers were ceapes hierdas. cattle keepers ‘What! It is said that our old fathers (ancestors) were cowherds.’ (cocura,CP:17.109.4.716)

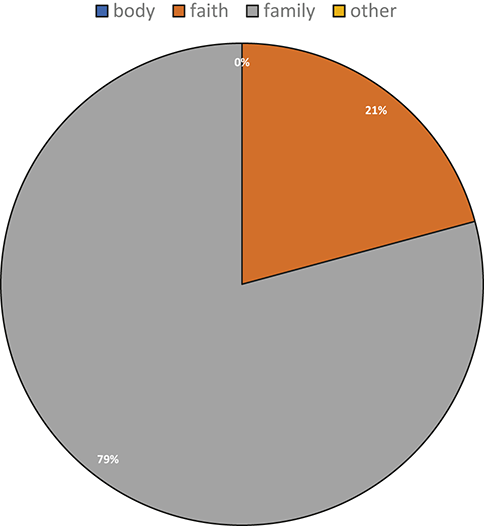

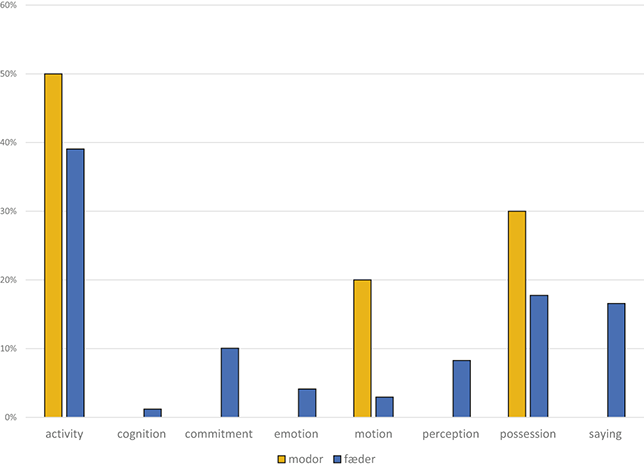

Figure 4 shows that, again, the proportion of positive adjectives is much higher for the male term (61 per cent for fæder and only 30 per cent for modor), and adjectives related to physicality are marginally used in the case of men (only 5 per cent).

| Number | Lemma | Translation | Category | Σ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | heofonlic+fæder | heavenly father | neutral | 87 |

| 2 | halig+fæder | holy father | positive | 84 |

| 3 | eallmihtig+fæder | almighty father | positive | 69 |

| 4 | arwurþ+fæder | noble father | positive | 51 |

| 5 | ilca+fæder | same father | neutral | 25 |

| 6 | eald+fæder | old father | physical | 22 |

| 7 | leof+fæder | dear father | positive | 21 |

| 8 | god+fæder | good father | positive | 14 |

| 9 | agen+fæder | own father | neutral | 10 |

| 10 | ece+fæder | eternal father | neutral | 8 |

| 11 | wis+fæder | wise father | positive | 8 |

| 12 | mildheort+fæder | merciful father | positive | 6 |

| 13 | arfæst+fæder | honourable father | positive | 5 |

| 14 | soþ+fæder | true father | positive | 5 |

| – | other | – | – | 42 |

| – | total recurrent | – | – | 457 |

Figure 4 Semantic categories of recurrent adjectival collocates of fæder ‘father’ in YCOE.

The collocation analysis of the two parental terms yields results similar to the examination of general female and male terms. It has to be noted, nonetheless, that these findings are of more limited relevance: because of their use in religious contexts, both modor and fæder have referents which do not relate to the linguistic image of women and men in Old English. An interesting observation concerns the historical lineage of Anglo-Saxon society: given that ancestors are denoted as ‘old fathers’ and not ‘old mothers’, it can be assumed that the socio-cultural legacy of Anglo-Saxons was found in paternality, which certainly agrees with a tendency generally observed in other cultures and languages.

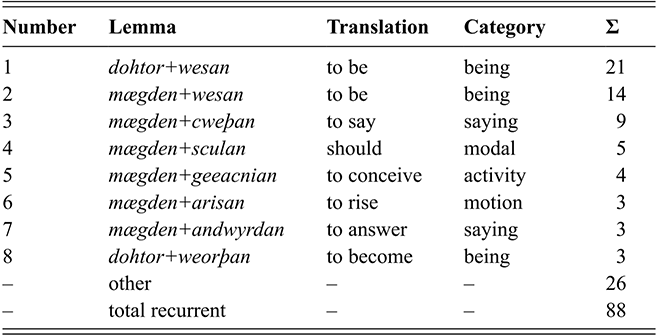

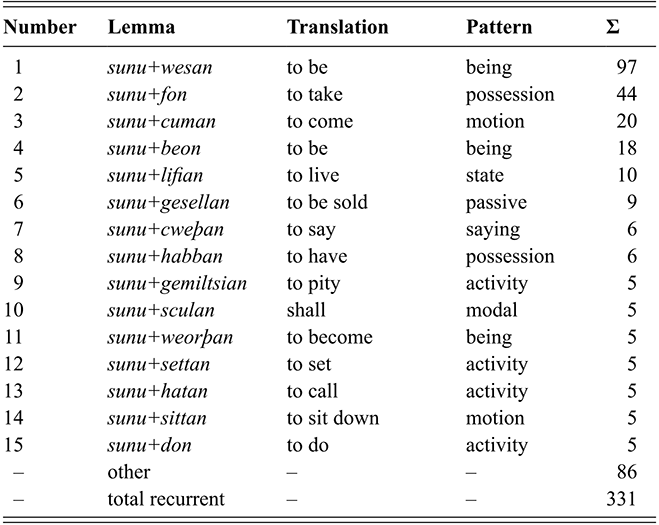

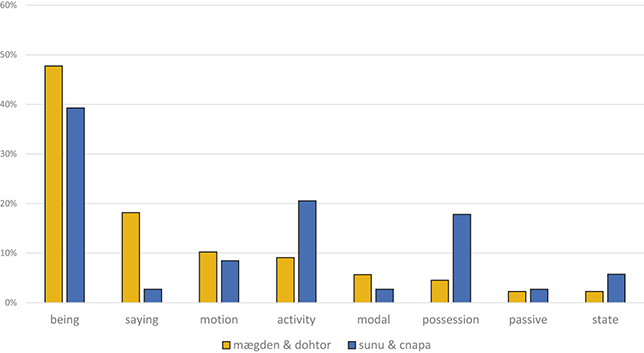

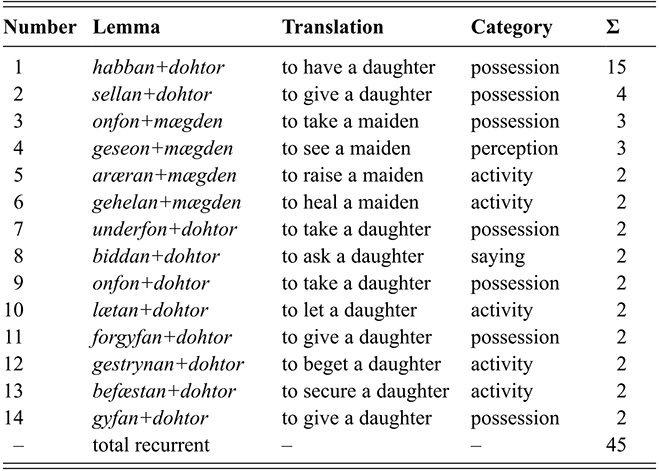

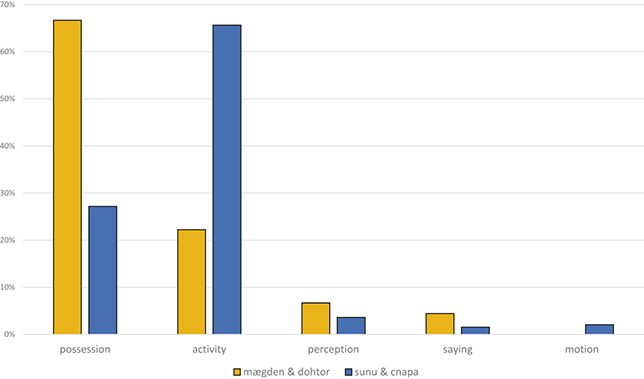

3.1.3 Terms Denoting Children and Young Adults

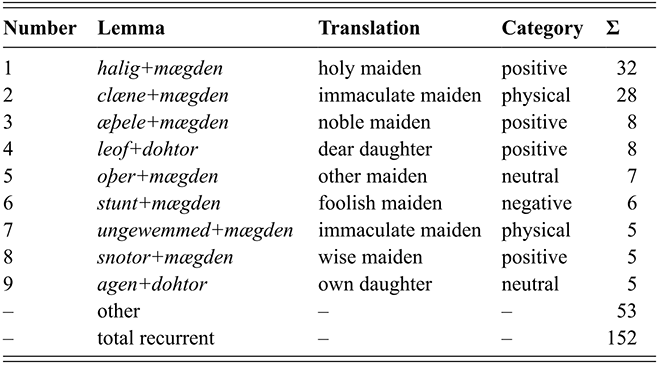

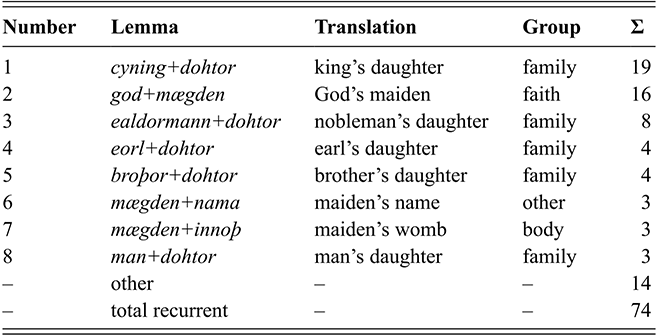

In the ‘child and young adult’ category illustrated in Table 8, the two female nouns, mægden ‘maiden’ and dohtor ‘daughter’, are regularly presented in the context of their sexual purity (clæne ‘clean, immaculate’ and ungewemmed ‘untouched, immaculate’). The holy and immaculate maiden is of course the Virgin Mary who became Christ’s mother, so once again the data are dominated by a single female referent.

(15)

Se ylca Godes sunu geceas him to meder þæt halige the same God’s son chose him to mother the holy mæden, Marian gehaten maiden Mary called ‘God’s son also chose the holy maiden called Mary to be his mother.’ (colwstan1,+ALet_2_[Wulfstan_1]:13.29)

(16)

ac Crist næs na geteald to þissere but Christ not-was not included to this wiðmetenysse, se þe acenned wæs of ðam comparison this that born was of the clænan mædene. clean maiden ‘But Christ was not included in this comparison, he who was born of the clean maiden.’ (colsigewZ,+ALet_4_[SigeweardZ]:855.343)

Sometimes, though, it is a young female, as in the biblical story about wise and foolish virgins, or in the case of Apollonius of Tyre, where the king’s daughter is one of the characters in the story, and leof ‘dear’ is again used in a vocative phrase.

(17)

Þa stuntan mædenu cwædon to ðam snoterum; the stupid maidens said to the wise ‘The foolish maidens said to the wise ones’ (cocathom2,+ACHom_II,_44:327.14.7348)

(18)

and cwæð: leofe dohtor, þu gesingodest; and said dear daughter you sinned ‘And said: Dear daughter, you have sinned’ (coapollo,ApT:16.2.303)

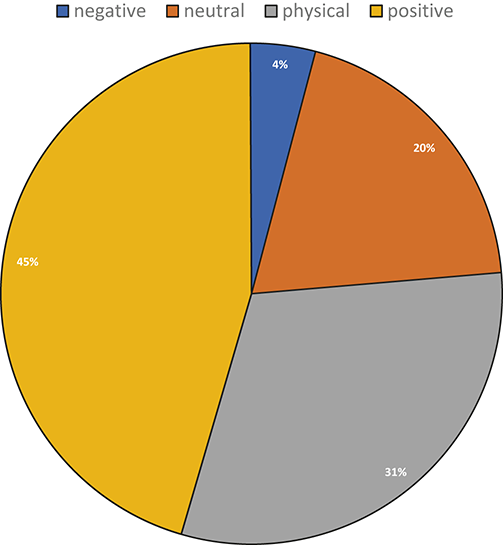

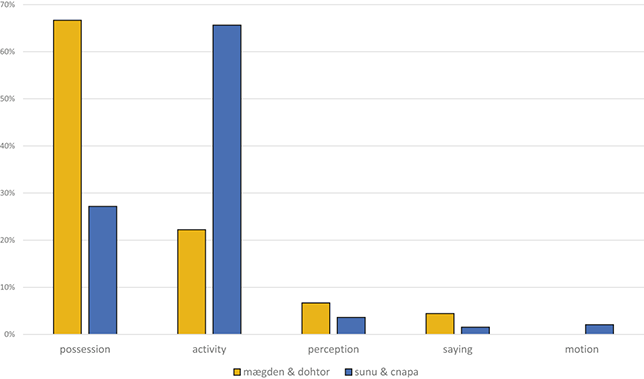

All in all, positive adjectives are the dominant category (cf. Figure 5). This stems mostly from the fact that the texts in the corpus often accentuate the virginity of maidens and daughters, a characteristic strongly valued by the Christian religion and consequently associated with positive features of character. Again, as with previously examined female nouns, the proportion of adjectives describing physicality is high, amounting here to 31 per cent.

| Number | Lemma | Translation | Category | Σ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | halig+mægden | holy maiden | positive | 32 |

| 2 | clæne+mægden | immaculate maiden | physical | 28 |

| 3 | æþele+mægden | noble maiden | positive | 8 |

| 4 | leof+dohtor | dear daughter | positive | 8 |

| 5 | oþer+mægden | other maiden | neutral | 7 |

| 6 | stunt+mægden | foolish maiden | negative | 6 |

| 7 | ungewemmed+mægden | immaculate maiden | physical | 5 |

| 8 | snotor+mægden | wise maiden | positive | 5 |

| 9 | agen+dohtor | own daughter | neutral | 5 |

| – | other | – | – | 53 |

| – | total recurrent | – | – | 152 |

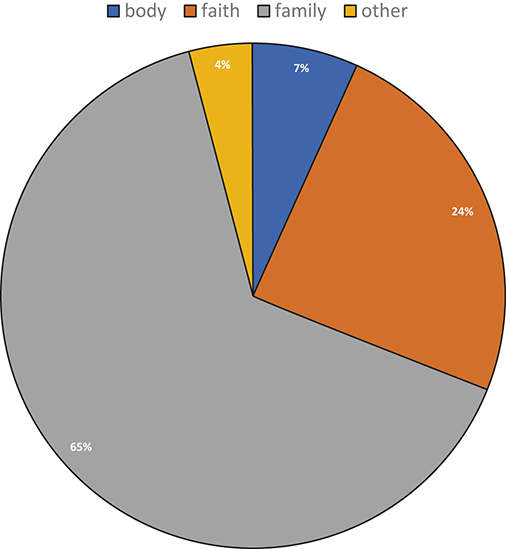

Figure 5 Semantic categories of recurrent adjectival collocates of mægden ‘maiden’ and dohtor ‘daughter’ in YCOE.

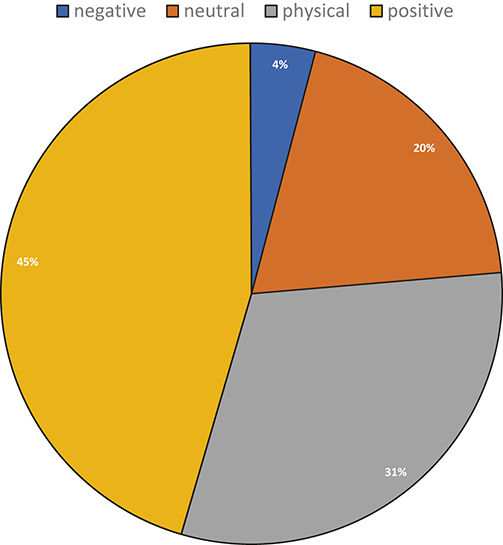

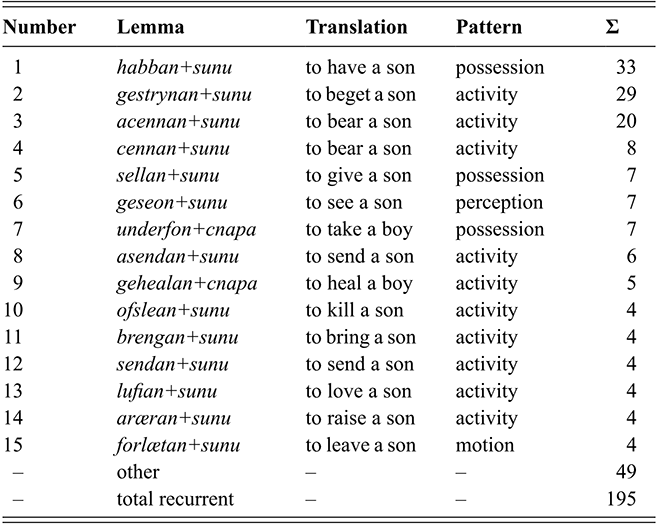

In the case of young males, the most frequent adjectives used to describe them can be classified as neutral (cf. Table 9). It is interesting to note, however, that a significant number of them describe the relation of a son to other (usually male) children (ancenned ‘only begotten’, frumcenned ‘firstborn’, oþer ‘other, second’, etc.). This emphasis on the distinction between firstborn and other sons might be linked with the development of a socio-cultural process which will later, in Norman times, lead to introducing primogeniture as a basis of land inheritance. Primogeniture, whose roots might be traced in the Bible, was not universally observed in early medieval Europe: the inheritance laws followed the pattern of Roman law, which did not distinguish between older and younger or between male and female heirs. Yet, the development of the medieval feudal system stipulated that the socio-political power of a lord depended on keeping the land estate large, so its division between family members was not favourable. Therefore, the Norman laws provided that the lord’s oldest son, not daughter, inherited the entire estate.

| Number | Lemma | Translation | Category | Σ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ancenned+sunu | only begotten son | neutral | 46 |

| 2 | agen+sunu | own son | neutral | 31 |

| 3 | oþer+sunu | other/second son | neutral | 23 |

| 4 | leof+sunu | dear son | positive | 23 |

| 5 | eald+sunu | old son | physical | 13 |

| 6 | frumcenned+sunu | firstborn son | neutral | 11 |

| 7 | ilca+sunu | same son | neutral | 9 |

| 8 | dead+sunu | dead son | physical | 8 |

| 9 | geong+sunu | young son | physical | 7 |

| 10 | soþ+sunu | true son | positive | 5 |

| – | other | – | – | 36 |

| – | total recurrent | – | – | 212 |

The importance of male over female offspring is visible in the higher frequency of the word sunu ‘son’ (1,889) compared to dohtor ‘daughter’ (380). This does not necessarily result from religious referents: while many uses of sunu are references to Jesus, the son of God, most of the collocations listed in Table 9 pertain to other, human sons.

(19)

Æfter þæm Lisimachus ofslog his agenne sunu Agothoclen & after that Lisimachus killed his own son Agothoclen and Antipater his aþum. Antipater his son-in-law ‘Afterwards Lisimachus killed his own son Agothoclen and his son-in-law Antipater.’ (coorosiu,Or_3:11.82.13.1645)

Naturally, Jesus Christ is attested in the data, for example, in (20), but this referent does not dominate in the same way as Mary, the virgin and the mother, dominates the collocation sets for modor ‘mother’ and mæden ‘maiden’.

(20)

& cwæþ, her ys min leofa sunu on þam me and said here is my dear son on whom me wel gelicaþ; well pleases ‘And said: Here is my dear son, in whom I am well pleased.’ (cowsgosp,Mt_[WSCp]:17.5.1128)

All the recurrent adjectival collocations combined prove to be mostly neutral in meaning (cf. Figure 6). For male terms, 16 per cent is quite a high result for collocates related to physicality, but almost all of them are related to the sons’ age or their death; not a single one describes their appearance. Frequently, neutral and physical collocates associate with family seniority, which can have a connection with primogeniture, as indicated previously.

Figure 6 Semantic categories of recurrent adjectival collocates of sunu ‘son’ and cnapa ‘boy’ in YCOE.

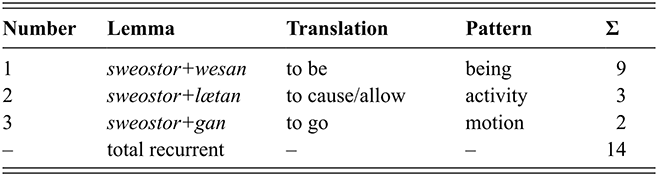

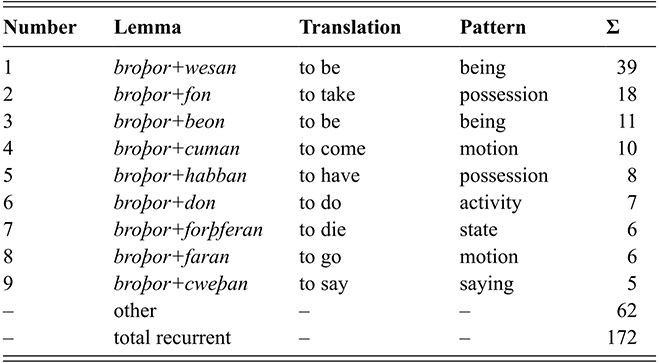

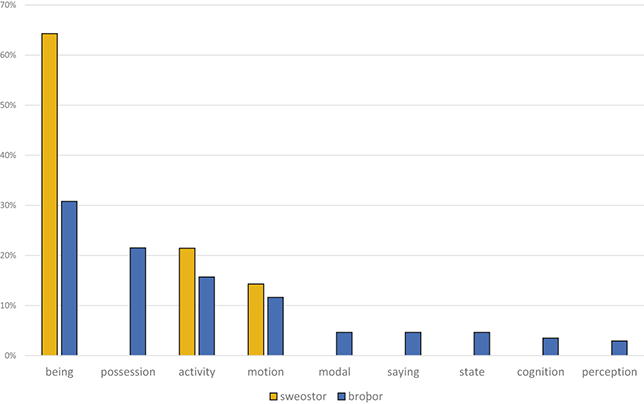

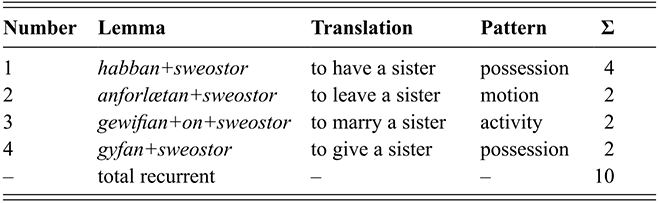

3.1.4 Sibling Terms

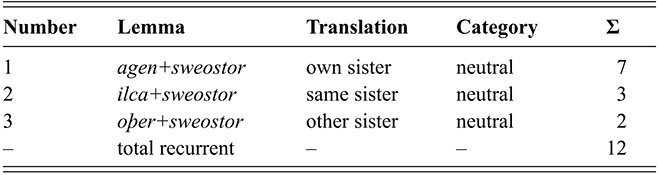

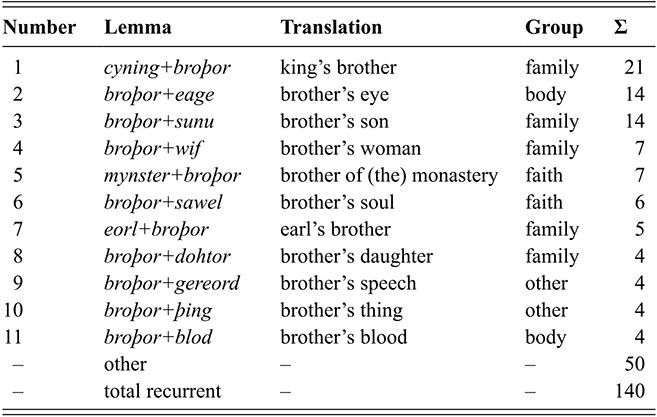

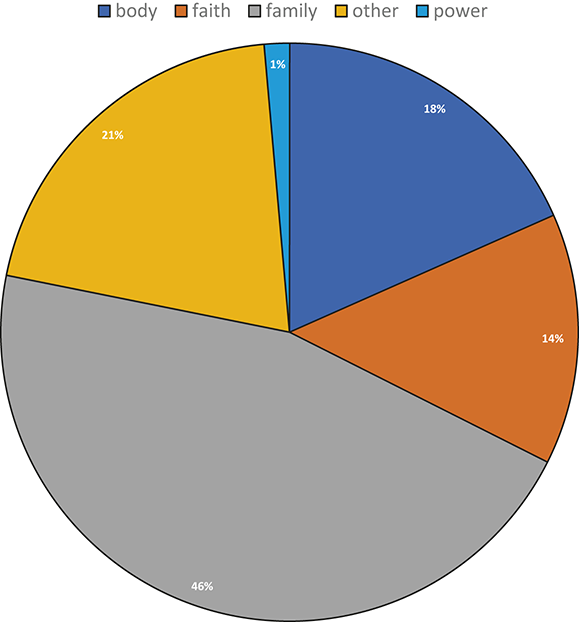

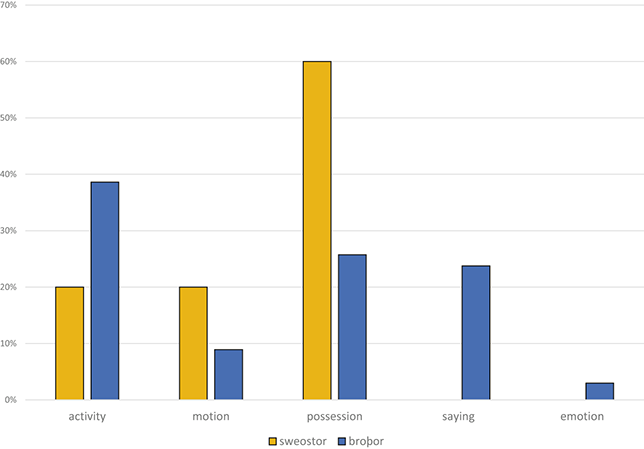

The next set of terms from the semantic field ‘sibling’ prove extremely unevenly represented. In the case of sweostor ‘sister’ there are only three recurrent adjectival collocations amounting to only twelve occurrences in total, all of them completely neutral in meaning, as illustrated by Table 10. The complete asymmetry between sweostor and broþor is quite clearly indicated by Table 11, with 166 tokens representing the latter.

| Number | Lemma | Translation | Category | Σ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | agen+sweostor | own sister | neutral | 7 |

| 2 | ilca+sweostor | same sister | neutral | 3 |

| 3 | oþer+sweostor | other sister | neutral | 2 |

| – | total recurrent | – | – | 12 |

| Number | Lemma | Translation | Category | Σ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | oþer+broþor | other brother | neutral | 62 |

| 2 | geong+broþor | young brother | physical | 18 |

| 3 | agen+broþor | own brother | neutral | 16 |

| 4 | ilca+broþor | same brother | neutral | 14 |

| 5 | leof+broþor | dear brother | positive | 14 |

| 6 | eald+broþor | old brother | physical | 12 |

| 7 | dead+broþor | dead brother | physical | 10 |

| – | other | – | – | 20 |

| – | total recurrent | – | – | 166 |

It is worth noting that most of the brothers referred to in the collocations are monks, disciples and generally ‘spiritual brothers’ as in (21), more often than actual siblings as in (22), which quite clearly shows the stronger association of females with family life and males with public service.

(21)

Þa cwæþ Iohannes, Bletsiað, Broþor þa leofestan, then said John bless brothers the dearest urne God our God ‘Then John said: Dear brothers, bless our God.’ (coblick,LS_20_[AssumptMor[BlHom_13])

(22)

Ic and Ionathas, min gingra broðor, Farað to I and Jonathan my younger brother go to Galaað to afligenne þa hæðenan. Galatia to drive away the heathens ‘I and Jonathan, my younger brother, (will) go to Galatia to drive away the heathens.’ (coaelive,+ALS_[Maccabees]:401.5101)

Since many of the OE texts discuss death of monks and their age, the proportion of physical collocates shown in Figure 7 is quite high, but the only lexemes attested in this group are geong ‘young’, eald ‘old’ and dead ‘dead’.

Figure 7 Semantic categories of recurrent adjectival collocates of broþor ‘brother’ in YCOE.

Generally, it has to be noted that the analysis of the female and male terms in the sibling category does not yield any noteworthy results, mostly due to an insufficient amount of data.

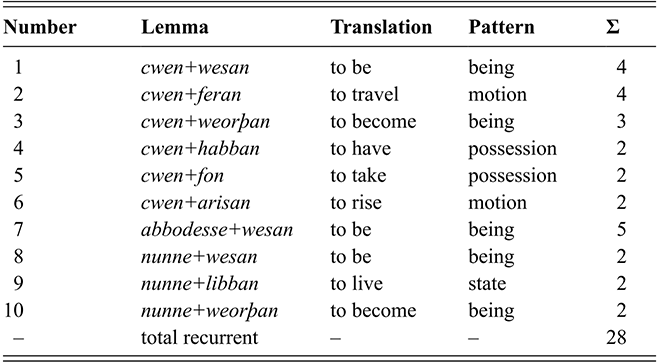

3.1.5 Terms Denoting Women and Men of High Social Status

The last group of gendered nouns represents a different cultural perspective, since it shows a combination of two sociolinguistic features: gender and social position. The category embraces female and male nouns designating people of high social status. The analysis clearly shows that queens, ladies, nuns and abbesses, who were definitely the highest-ranking females in Anglo-Saxon society, do not pattern with other women terms. Table 12 shows that the collocations, infrequent as they are, in most cases are positive and not a single one of them refers to the woman’s physicality. It is important to note that the queen or lady referred to in the data is often Mary, the mother of Jesus, as in (23), but the proportions are quite balanced and (24) is a representative example.

(23)

ala þu wuldorfæste hlæfdige þe þone soðan God oh you glorious lady who the true God æfter flæsces gebyrde acendest … after flesh.GEN origin bore ‘Oh, you glorious lady, who gave birth to the true God in flesh.’ (comary,LS_23_[MaryofEgypt]:431.281)

(24)

He wæs se forma casere þe on Crist gelyfde, he was the first emperor who on Christ believed Sancte Elenan sunu, þære eadigan cwene Saint Elena son the blessed queen ‘He was the first emperor who believed in Christ, the son of Saint Elena, the blessed queen.’ (colwstan1,+ALet_2_[Wulfstan_1]:47.87)

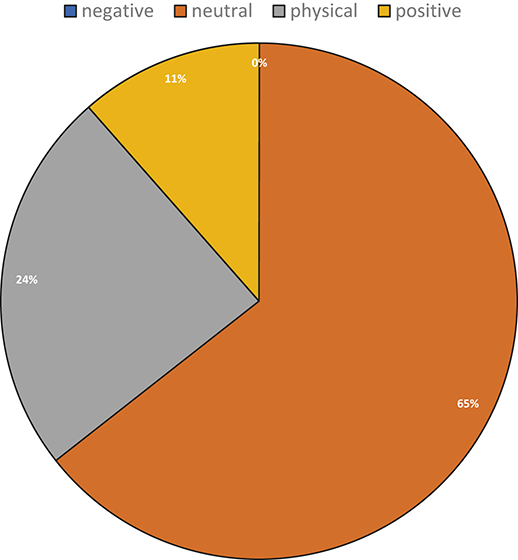

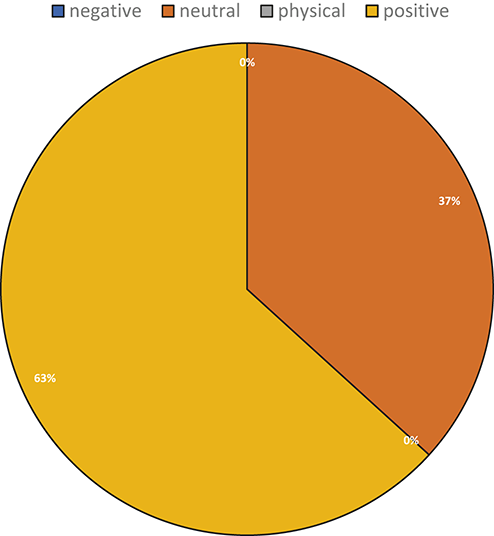

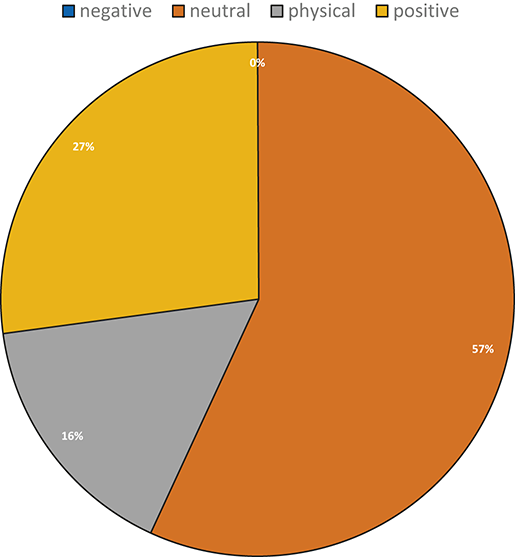

When we look at proportions, shown in Figure 8, the graph resembles a typical one for male-gendered nouns, with positive adjectives completely dominating and physical ones absent from the dataset.

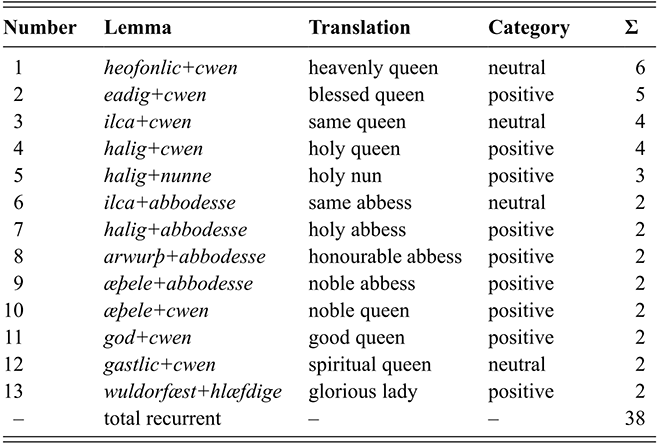

| Number | Lemma | Translation | Category | Σ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | heofonlic+cwen | heavenly queen | neutral | 6 |

| 2 | eadig+cwen | blessed queen | positive | 5 |

| 3 | ilca+cwen | same queen | neutral | 4 |

| 4 | halig+cwen | holy queen | positive | 4 |

| 5 | halig+nunne | holy nun | positive | 3 |

| 6 | ilca+abbodesse | same abbess | neutral | 2 |

| 7 | halig+abbodesse | holy abbess | positive | 2 |

| 8 | arwurþ+abbodesse | honourable abbess | positive | 2 |

| 9 | æþele+abbodesse | noble abbess | positive | 2 |

| 10 | æþele+cwen | noble queen | positive | 2 |

| 11 | god+cwen | good queen | positive | 2 |

| 12 | gastlic+cwen | spiritual queen | neutral | 2 |

| 13 | wuldorfæst+hlæfdige | glorious lady | positive | 2 |

| – | total recurrent | – | – | 38 |

Figure 8 Semantic categories of recurrent adjectival collocates of cwen ‘queen’, abbodesse ‘abbess’, hlæfdige ‘lady’ and nunne ‘nun’ in YCOE.

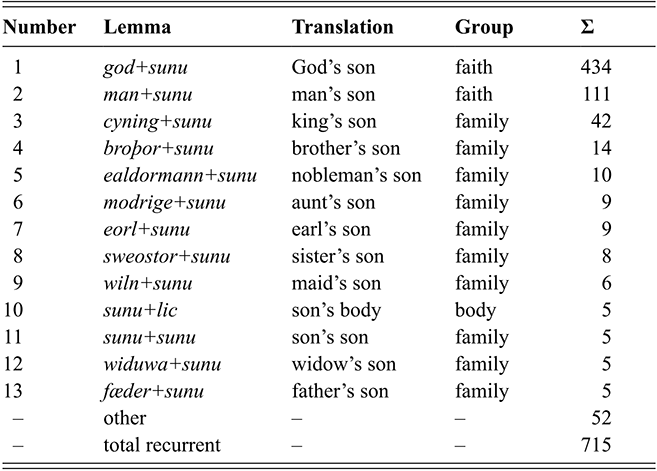

In the case of high-ranking males, there is a real abundance of data, with 630 tokens attested and the most frequent ones listed in Table 13. While the heavenly king in (25) is a clear reference to Jesus Christ, and many instances of the lexeme hlaford ‘lord’ as in (26) are references to God, real kings are definitely present in the data (cf. (27) and (28)), and some of them are not positive characters.

(25)

& he, se heofonlica cyning, þæt eall swiðe and he the heavenly king that all very geðyldelice abær for mancynnes lufan & hælo. patiently bore for mankind’s love and salvation ‘And he, the heavenly king, who suffered everything with great patience for the love and salvation of mankind.’ (coverhomE,HomS_24.1_[Scragg]:259.232)

(26)

We biddað þe, leof hlaford, þæt ðu gehyran we bid you dear lord that you hear wylle ure word. will our words ‘We bid you, dear Lord, that you hear our words.’ (cosevensl,LS_34_[SevenSleepers]:273.210)

(27)

and þæt word sprang Geond eal þæt land þæt and the word sprang throughout all the land that Apollonius, se mæra cyngc, Hæfde funden his wif, Apollonius the great king had found his wife ‘And it became known throughout the land that the great king Apollonius had found a wife.’ (coapollo,ApT:49.9.521)

(28)

Ac on þære nihte þe se arleasa cyning hine on but on the night that the honourless king him on merigen acwellan wolde com Godes engel morning kill wanted came God’s angel scinende of heofenum shining of heaven ‘But the night before the morning when the honourless king wanted to kill him, God’s angel came shining from heaven.’ (cocathom1,+ACHom_I,_37:505.240.7503)

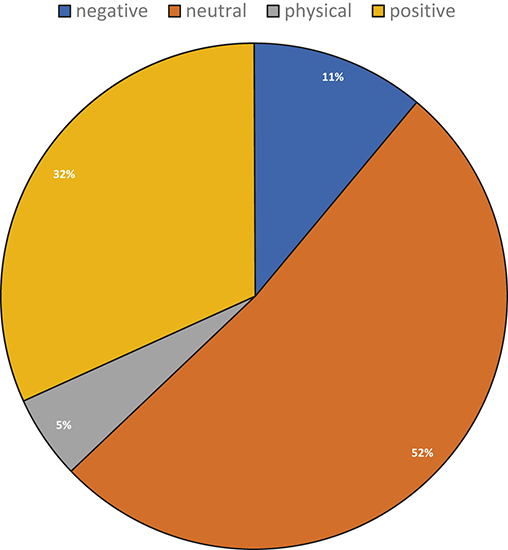

Figure 9 shows that while the most frequent adjective category is neutral collocations, the proportion of positive ones is relatively high and, unsurprisingly, modifiers describing physicality are the least numerous group.

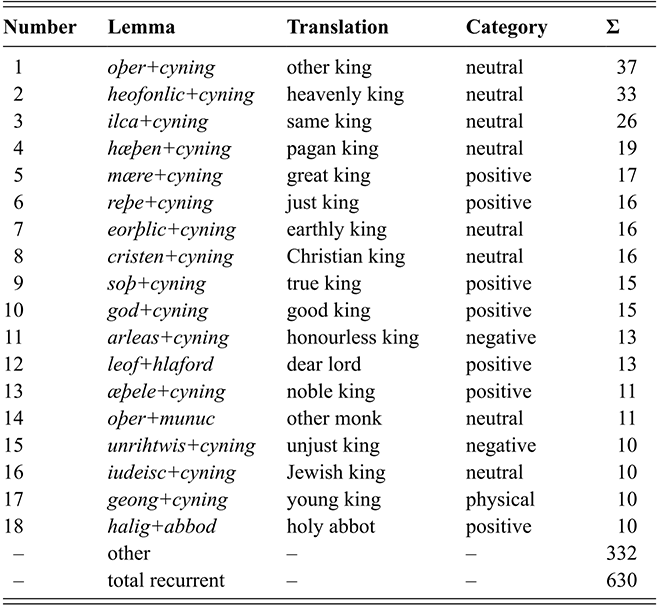

| Number | Lemma | Translation | Category | Σ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | oþer+cyning | other king | neutral | 37 |

| 2 | heofonlic+cyning | heavenly king | neutral | 33 |

| 3 | ilca+cyning | same king | neutral | 26 |

| 4 | hæþen+cyning | pagan king | neutral | 19 |

| 5 | mære+cyning | great king | positive | 17 |

| 6 | reþe+cyning | just king | positive | 16 |

| 7 | eorþlic+cyning | earthly king | neutral | 16 |

| 8 | cristen+cyning | Christian king | neutral | 16 |

| 9 | soþ+cyning | true king | positive | 15 |

| 10 | god+cyning | good king | positive | 15 |

| 11 | arleas+cyning | honourless king | negative | 13 |

| 12 | leof+hlaford | dear lord | positive | 13 |

| 13 | æþele+cyning | noble king | positive | 11 |

| 14 | oþer+munuc | other monk | neutral | 11 |

| 15 | unrihtwis+cyning | unjust king | negative | 10 |

| 16 | iudeisc+cyning | Jewish king | neutral | 10 |

| 17 | geong+cyning | young king | physical | 10 |

| 18 | halig+abbod | holy abbot | positive | 10 |

| – | other | – | – | 332 |

| – | total recurrent | – | – | 630 |

Figure 9 Semantic categories of recurrent adjectival collocates of cyning ‘king’, hlaford ‘lord’, abbod ‘abbot’ and munuc ‘monk’ in YCOE.

The analysis of this category yields particularly interesting results if we examine them against the data from the previous noun groups. It might at first seem paradoxical that high-ranking women have no negative collocates, nor those related to the body. However, since all the referents of female terms examined here are women of an esteemed social status, the results cannot be used to make assumptions about the general position and regard of women in Anglo-Saxon society. A queen or a lady is not supposed to be described in negative terms, either because she is the mother of Christ or because she is a higher-ranking person than the author of the text. An abbess or a nun, in turn, is part of the religious community of the church, which also guarantees her positive social recognition. Furthermore, the fact that Anglo-Saxon society was stratified means that only average (i.e. low-ranking) women were perceived in terms of their physical qualities.

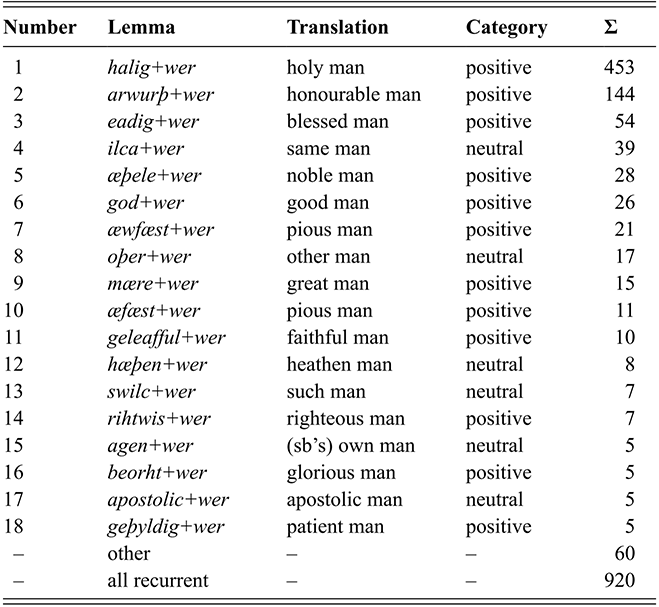

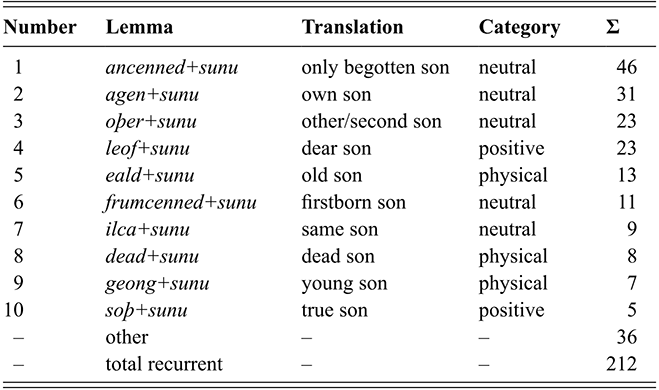

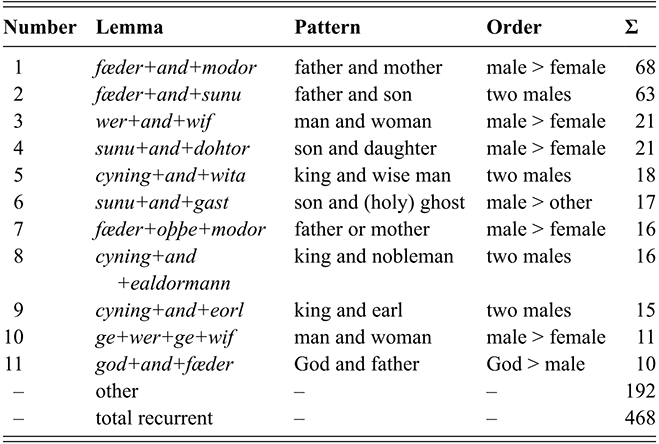

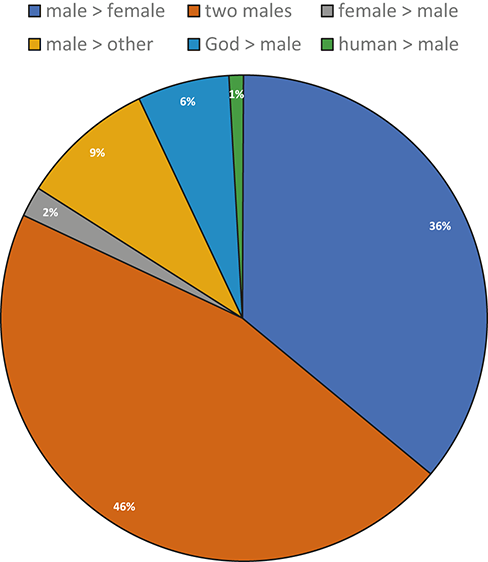

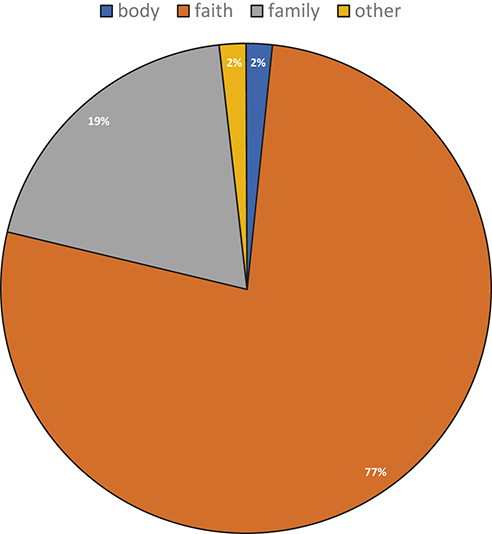

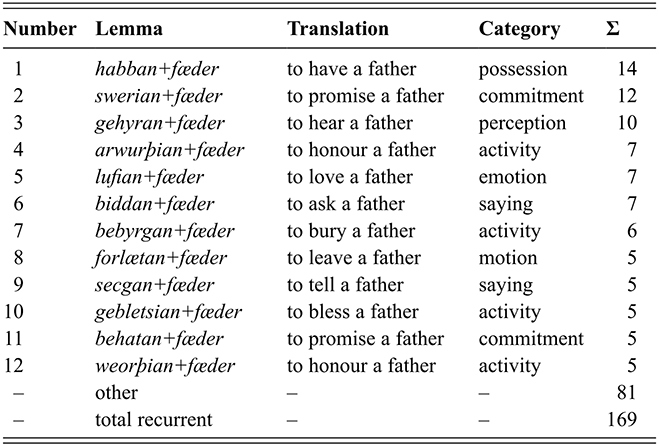

3.2 Binominals (N + CONJ + N)

Studies show that when two nouns are joined by a conjunction, their order is not random and the factors which play a role in the variation are power or importance (the supreme item comes first), length (the shorter item comes first) and frequency (the more frequent item comes first) (Goldberg & Lee, Reference Goldberg and Lee2021). Therefore, for instance, when we compare the order of the two most general gendered nouns, wif and wer, bearing in mind that they are both one-syllable, three-sound words and that the frequency of their designates is comparable, a visible preference of one over the other in the initial position may only be interpreted as difference in power and importance. Table 14 shows very clearly that in the patterns involving two grown-up people of different gender, the male term virtually always comes first, as in (29) and (30).

(29)

Wæron his fæder & his modor buta hæðen. were his father and his mother both heathen ‘His father and his mother were both heathen.’ (coverhom,LS_17.2_[MartinVerc_18]:9.2230)

(30)

And hi ðær genamon inne ealle þa gehadodan and they there took in all the ordained men and weras and wif people and men and women ‘And they took in all the ordained people, both men and women.’ (cochronC,ChronC_[Rositzke]:1011.21.1522)

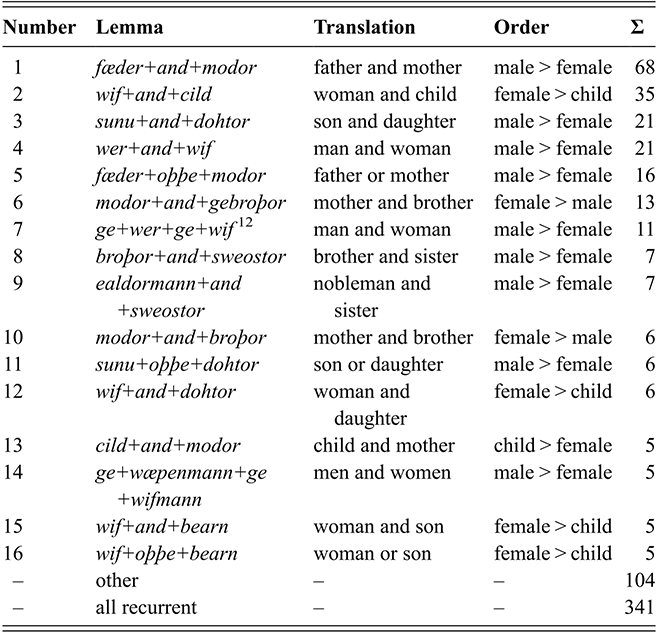

| Number | Lemma | Translation | Order | Σ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | fæder+and+modor | father and mother | male > female | 68 |

| 2 | wif+and+cild | woman and child | female > child | 35 |

| 3 | sunu+and+dohtor | son and daughter | male > female | 21 |

| 4 | wer+and+wif | man and woman | male > female | 21 |

| 5 | fæder+oþþe+modor | father or mother | male > female | 16 |

| 6 | modor+and+gebroþor | mother and brother | female > male | 13 |

| 7 | ge+wer+ge+wifFootnote 12 | man and woman | male > female | 11 |

| 8 | broþor+and+sweostor | brother and sister | male > female | 7 |

| 9 | ealdormann+and+sweostor | nobleman and sister | male > female | 7 |

| 10 | modor+and+broþor | mother and brother | female > male | 6 |

| 11 | sunu+oþþe+dohtor | son or daughter | male > female | 6 |

| 12 | wif+and+dohtor | woman and daughter | female > child | 6 |

| 13 | cild+and+modor | child and mother | child > female | 5 |

| 14 | ge+wæpenmann+ge+wifmann | men and women | male > female | 5 |

| 15 | wif+and+bearn | woman and son | female > child | 5 |

| 16 | wif+oþþe+bearn | woman or son | female > child | 5 |

| – | other | – | – | 104 |

| – | all recurrent | – | – | 341 |

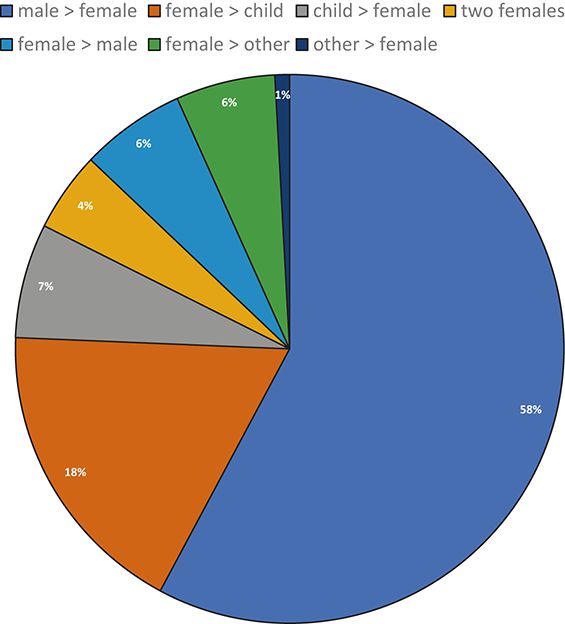

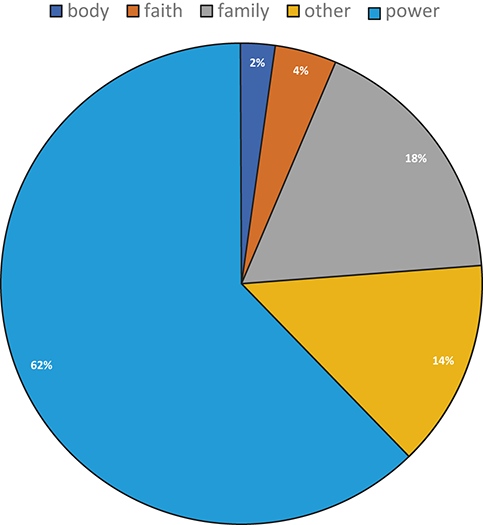

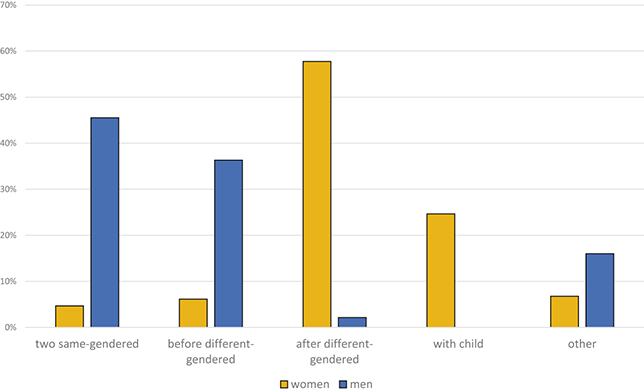

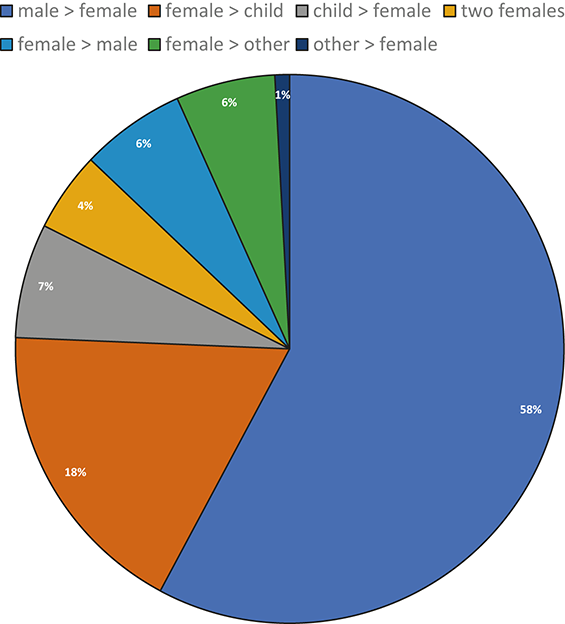

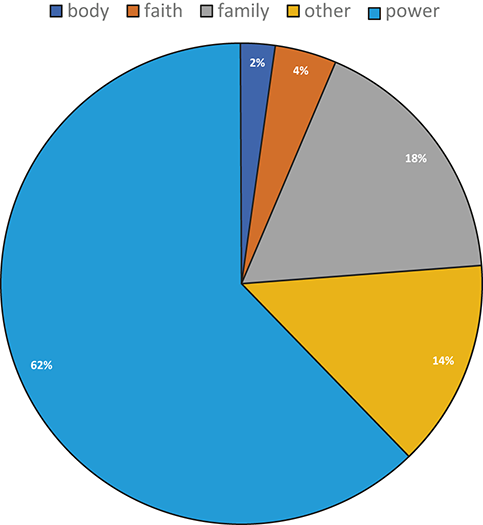

Figure 10 proves that the difference is quite overwhelming. When a pair consists of a female and a male, the order prioritising the male is ten times more frequent (58 per cent vs. 6 per cent). The discrepancy becomes much more striking when we consider that the order privileging women occurs only in the pairs modor+and+gebroþor and modor+and+broþor – that is, mother and brother – in which the female is favoured not because of the gender but due to her age and family position. This is analogous to wif+and+cild, where a woman is phrase-initial when occurring with the gender-neutral child. However, when a child is male, both orders are attested (cf. (31) and (32)).

(31)

& ðu gæst in to ðam arce, & ðine suna, and you go in to the ark and your sons & ðin wif & ðinra suna wif mid ðe. and your woman and your sons’ women with you ‘And you shall go into the ark, and your sons and your wife and your sons’ wives with you.’ (cootest,Gen:6.18.294)

(32)

& Hæstenes wif & his suna twegen mon brohte And Hasten’s woman and his sons two one brought to þæm cyninge to the king ‘And Hasten’s wife and his two sons were brought to the king.’ (cochronA-2a,ChronA_[Plummer]:894.52.1057)

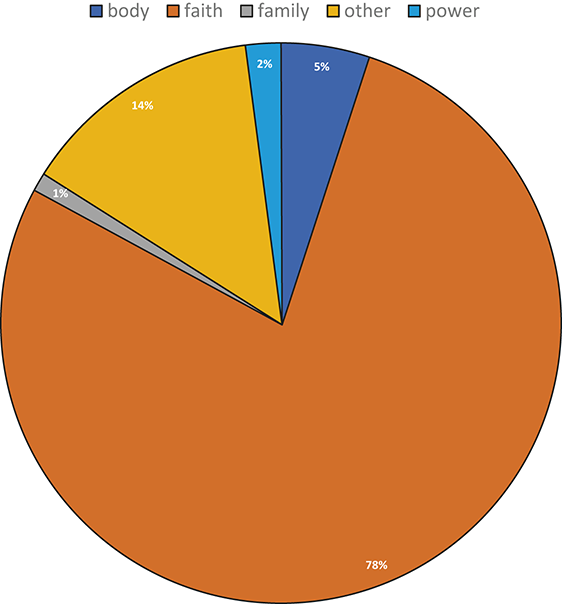

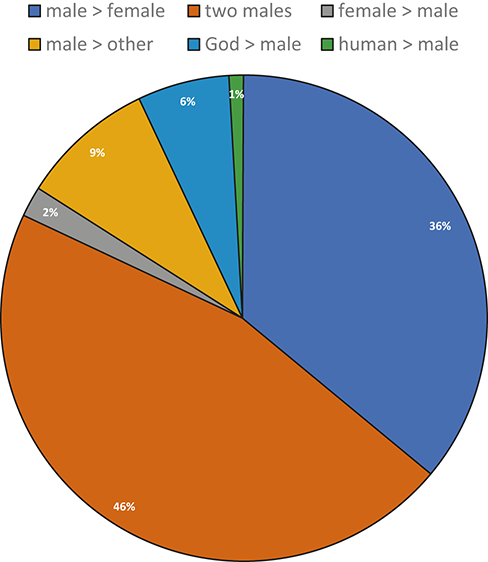

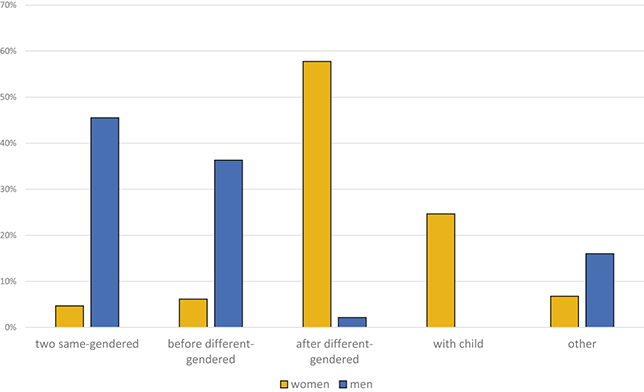

Figure 10 Recurrent binominals with female nouns in YCOE.

Figure 10Long description

The chart shows the following proportions: 58% “male > female”, 18% “female > child”, 7% “child > female”, 6% “female > male”, 6% “female > other”, 4% “two females”, and 1% “other > female”. The largest category is “male > female”, with the rest making up smaller portions.