I said: “Master, would I have been able to understand these things? Nor could some other person, even if they were extremely intelligent, be able to understand them.”

An enslaved person, living in Rome in the fourth century CE, was punished by their enslaver for attempting to flee from their involuntary bondage and exploitation of labor. In order to prevent this from happening again, the enslaver forced the enslaved person to wear a metal collar with a bronze tag. The collar and tag had already been used once before – likely for a different enslaved person. On the already inscribed side of the tag, probably used during the reign of Constantine, it reads: “Detain me because I fled, and return me to Victor the acolyte at the dominicum of Clement ☧.”Footnote 1 Newly engraved on the other side for this enslaved person was: “I fled from Euplogius, from the office of the prefects of the city ☧.”Footnote 2 Given the size and location of the collar and tag, the enslaved person themselves could hardly see it, since it was meant to function as “a visual act … to permanently mark the slave in a certain way for all others to see.”Footnote 3 This enslaved person, whose name is lost to us, was hardly alone in experiencing this practice of marking-via-collar well attested by Italian Christians, which emerged as a substitute for tattooing criminalized and enslaved persons under Constantine.Footnote 4

Enslaved persons such as the unnamed bearer of this collar – willingly or not – likely participated in Christian practices, went to Christian spaces, or heard readings of Christian texts. As scholars like Sandra Joshel, Lauren Hackworth Petersen, and Katherine Shaner have argued in depth, enslaved persons were ubiquitous in the Roman world and are made invisible to scholars by the lack of material evidence they left behind – that “city spaces are rhetorical spaces that attempt to persuade viewers and dwellers alike of enslaved invisibility and compliance with kyriarchial expectations.”Footnote 5 The same holds true for deathscapes, cemeteries, and catacombs where inhabitants of the Roman Empire gathered to bury, mourn, and perform ritual practices for, with, and through enslaved persons.Footnote 6

One of the spaces some enslaved or formerly enslaved persons likely spent time in the Italian landscape is the Catacomb of San Gennaro in Neapolis (modern day Naples), roughly a two-day travel south of the imperial capital of Rome.Footnote 7 While the Neapolitan tomb space was used by others in the early Roman imperial era, by the third century Christians were expanding the catacombs, burying their dead, and decorating their tombs here. By the fourth century, an underground church was constructed in the catacomb complex just a few meters away from the first Christian catacomb space in the complex. In that room, one of the oldest rooms of the catacomb, was a fresco of three women building a tower out of quarried stones. The fresco – alongside others in the room depicting Adam and Eve or David and Goliath – has often been believed to be a scene from the Shepherd of Hermas, a popular early Christian text in which there are two visionary scenes of women involved in the construction of a tower that represents the Assembly (Ἐκκλησία, often translated as “Church”).Footnote 8 While not exactly representative of either scene, the depiction seems closer to the narrative provided by an angelic interlocutor called the Shepherd that occurs near the end of the text. In this visionary experience, the Shepherd explains to an enslaved man named Hermas how the tower represents the assembly of believers – built by women who represent various virtues that one must acquire to enter the tower – and that the tower is constructed from the stones of twelve mountains that represent various types of people. An enslaved or formerly enslaved person, like the unnamed collar-bearer in fourth-century Rome, and other early Jesus adherents entering this catacomb room likely heard the Shepherd recited for moral exhortation and catechetical education in a local Neapolitan church.Footnote 9 Some who heard the story and associated the Neapolitan fresco with the Shepherd may have puzzled over which of the stone’s virtues they embodied, as well as how they could best live their lives in order to be incorporated into the tower and accomplish the Shepherd’s common refrain: to “live to God” (ζῆν τῷ θεῷ).

An enslaved or formerly enslaved person – or even those more cognizant of the pervasiveness of enslavement in the Roman imperial world – might have had other phrases from recitations of the Shepherd come to mind when they encountered this fresco.Footnote 10 From the tower vision itself, they might recall how the Shepherd “explains and speaks to God’s enslaved persons” (ἔδειξα καὶ ἐλάλησα τοῖς δούλοις τοῦ θεοῦ) so that they might live.Footnote 11 They might remember how the Shepherd claimed that the stones from the eleventh mountain – people who suffered for the name of the Son of God – are superior to others because they refused to deny God the enslaver (κύριος), because “the very thought that an enslaved person might deny their own enslaver is evil” (πονηρὰ γὰρ ἡ βουλὴ αὕτη, ἵνα δοῦλος κύριον ἴδιον ἀρνήσηται).Footnote 12 They might think of the twelve women dressed in black from the tower vision, counterparts of the virtuous women who represent various vices, and how the Shepherd claims that “God’s enslaved persons who bear the these names [i.e., Grief, Evil, Irascibility] will see the kingdom of God but will not enter it.”Footnote 13 When they hear that God’s enslaved persons can only live if they “bear the names” (φορεῖν τὰ ὀνόματα) of the virtuous women, they might consider the experience of bearing the name of their own enslaver upon their body by means of collars and wonder what makes “bearing the name” salvific.Footnote 14 While for some the narrative of the Shepherd of Hermas may represent something worth surrounding oneself with images of at one’s death and asking visitors to reflect upon, for others the text may be a constant reminder of their lived realities of enslavement, oppression, and exclusion. Enslavement to God and the mechanisms by which that enslavement was depicted in early Christian literature worked to normalize the ideologies and practices of enslavement.

Goals and Thesis of the Book

The Shepherd of Hermas, a first- or second-century Christian text written in Greek and purportedly from Rome, is a text that tends to confuse and frustrate historians of early Christian history. This 114-chapter collection of visionary and revelatory experiences by an enslaved man named Hermas is one of the most well-read early Christian texts not to have made it into the 27-book New Testament canon as it stands today, leaving scholars to ask: for what purposes did early Christians read and disseminate this text?Footnote 15 Who had interest in Hermas’s extensive visions and dialogues with various divine beings about topics as disparate as the construction of a stone tower, the impact of anger on the body, which types of fear are acceptable or not, and how the archangel Michael used sticks from a willow tree to determine the ethical purity of believers?

Many academic readers of the Shepherd over the last century have expressed their own distaste in the text’s length, lack of theological sophistication, and dearth of stories about Jesus and his apostles. Such critiques claimed that Hermas and his text would have led to the dissolution of the church worldwide because of Hermas’s lack of “intellectual quality,”Footnote 16 that Hermas “is a dilettante author who is simply unable to compose a balanced work of literature,”Footnote 17 that the Shepherd is nothing more than “pottering mediocrity,”Footnote 18 is a “rambling prophetic work which cannot easily be systematized,”Footnote 19 “often appears confused and obscure,”Footnote 20 “cumbersome texts by any account,”Footnote 21 and that “its length, monotony, and the pedantic style of large sections of it pose serious obstacles to all but the most devoted reader.”Footnote 22 Such scholarly boredom and frustration with the Shepherd’s contents and its author have often stood in the way of robust academic interest in a text written contemporaneously to literature that ended up in the New Testament and that, as I will show below, was heavily used by late ancient Christians.

Despite confusion about how to make sense of the Shepherd, some scholars have offered in-depth analyses of the text in order to understand its message. Many scholars have found repentance (μετάνοια) to be the key theme of the Shepherd (with 156 total uses of the term throughout the text), and have suggested that the text is meant to urge other Christians to repent before the end times.Footnote 23 Others, like Norbert Brox, see repentance as central but not the only theme present: “The subject of sin – repentance – improvement has clearly dominated up to this point, but the statements on this are sometimes vague, and other times inconsistent and weak.”Footnote 24 Still others have treated repentance in the Shepherd as the beginnings of formal ecclesiastical procedures of rituals of penitence and reincorporation into a Christian community, although such readings remain in the minority and are often based upon how one early Christian writer in particular (Tertullian of Carthage) attacked the Shepherd’s use in his own North African community.Footnote 25 Mark Grundeken, in his examination of community building in the Shepherd, has taken one more step in line with the history of scholarship on the Shepherd’s penitential focus and suggested that baptism is central to the text’s concept of repentance.Footnote 26 As with the idea of ritual penitence, however, its applicability to the entirety of the Shepherd is both shaped by Tertullian’s third-century debates over the acceptability of post-baptismal repentance in North African congregations and stems from a single passage of the Shepherd: Mandate 4.3 (31).Footnote 27 Still others, like Lage Pernveden, have pushed against the dominance of the repentance reading of the Shepherd by suggesting that participation in the ecclesial structure is the true goal of the text.Footnote 28

Along with highlighting the themes of repentance, baptism, and ritual penance, two other substantial interpretative directions have been taken. The first explores the socioeconomic history underlying the Shepherd with particular interest in its treatment of the rich and poor. For example, scholars like Carolyn Osiek and Jörg Rüpke find Hermas condemning how the wealthy in his Roman community treat the poor. Rüpke in particular begins to map out how Hermas’s visions might stem from local Italian topography and occupations, highlighting agricultural and salt mining contexts.Footnote 29 Jonathon Lookadoo builds upon these arguments and suggests that agricultural tenants were likely among the Shepherd’s original audience, given the types of imagery that Hermas used when recording and transmitting his visionary experiences and divinely given commandments.Footnote 30

Another approach builds upon the prominence of repentance in the Shepherd and asks: What is repentance aiming toward? In his recent book on the Shepherd’s transformation from a popular to an excluded text in late antiquity, Robert Heaton suggests scholars pay attention to how the Shepherd urges readers to inculcate particular virtues. As he puts it: “It [i.e., the Shepherd] was the book of practical salvation” and was “a paraenetic roadmap for the believer and a powerful fantasy-image through which to conceptualize the soteriological endgame.”Footnote 31 Repentance aims at doing, thinking, and feeling differently than before; it is the process but not the end goal for the text, as it has so often been treated. Heaton especially builds upon Patricia Cox Miller’s psychological reading based upon the dreams in the Shepherd, in which she foregrounds salvation as Hermas’s central concern and the thematic fountain from which the rest of the text flows.Footnote 32

Both of these approaches contribute substantially to our understanding of the Shepherd in two ways: they take into account the social context in which the Shepherd may have been written, and urge scholars to consider the types of subjects that the Shepherd’s exhortatory ethical material hopes to mold. Such scholarship has pointed to the inculcation of virtue, the distribution of material wealth and treatment of the poor, and a concern for achieving salvation before the eschaton.

In this book, I build upon such scholarship and put forward two additional points that I think are central for understanding not only the Shepherd, but early Christianity more broadly. Ancient Mediterranean slavery is a significant sociohistorical context for the Shepherd’s composition and literary content, and enslavement to God is central to the Shepherd’s crafting of Christian subjects as virtuous believers. This focus on enslavement does not negate the arguments of other scholars, but demonstrates that slavery is a key component that ought to be accounted for when analyzing the Shepherd’s treatment of God and believers. As a text that depicts itself as a set of revelatory instructions that late ancient Christians treated as a catechetical text and guide for Christian living, understanding how the Shepherd urges Christians to see communal and individual life as discursively built upon enslavement is all the more important to investigate.

My central thesis is that the Shepherd of Hermas crafts the ideal Christian subject within the discursive context of ancient Mediterranean slavery. I suggest that the Shepherd participates in contemporaneous Greek and Roman practices, discourses, and logics of enslavement through how it portrays the relationship between God and believers as that of enslaver and enslaved persons. In doing so, I read the Shepherd in a way that foregrounds and makes explicit language of enslavement, as well as interrogates how the Shepherd conceptualizes obedient enslavement to God as a goal worth achieving. My approach to translation makes this foregrounding visible. The Shepherd calls God a κύριος (kurios), a term that I will primarily define and translate throughout as “enslaver” or “master,” and refers to believers as “God’s enslaved persons” (οἱ δοῦλοι τοῦ θεοῦ).

The Shepherd makes three moves within the discourse of Mediterranean slavery that I will explore throughout the following chapters: (1) the what of enslavement; (2) the how of enslavement; and (3) the effects of enslavement. By “the what of enslavement,” I mean the characteristics of enslaved persons that are disseminated and perpetuated within a particular field of discourse – characteristics that often become stereotypical of the enslaved in ancient literature. “The how of enslavement” refers to the means by which people become enslaved and the mechanisms by which they are subjected and oppressed. Finally, “the effects of enslavement” refers to some of the consequences of existing as an enslaved person in a world populated by the enslaved and the free, and how enslaved persons navigate and negotiate within such a space.

The Shepherd’s crafting of Christian subjects through the discourse of enslavement is expressed extensively in how the text describes how God’s enslaved persons are supposed to behave and relate to God. The writer of the Shepherd participates in a broader Mediterranean discourse of enslavement to clarify what God’s “good slaves” ought to be like, as well as uses the revelatory narrative structure of the Shepherd itself to portray certain enslaved characteristics and behaviors as desirable. Since the Shepherd’s primary status marker for God’s people is as enslaved persons (δοῦλοι), what is at stake in reading the Shepherd as a text shaped by and deeply indebted to the institution of enslavement and its manifestations in the ancient Mediterranean? What might we notice or treat differently in this early Christian text (and others beyond it) when characterization as an enslaved person is foregrounded as the scaffolding upon which the ideal believer is constructed? The discourse of enslavement and its effects on the production of believers’ ethics and subjectivities may not always be equally salient in every verse or chapter of the Shepherd, but nonetheless shapes much of the text.

Such an examination of the Shepherd as one example of the effects of the discursive context of ancient Mediterranean slavery on early Christian literature is critical because of the millennia-long history of Christian institutional support for and normalization of enslavement. As Ulrike Roth powerfully argues in her work on enslavement in Paul’s letter to Philemon: “How the early Christians approached slavery is critical for our understanding of the wider issue of the relationship between the peculiar institution and the Church.”Footnote 33 Particularly since New Testament and early Christian literature are often turned to in modernity as a source of “original” or “essential” Christianity – despite the fact that multiplicity and diversity defines early Christian practices and writings – it is all the more important to elucidate how early Christians and their literature participated in practices, discourses, and logics of enslavement.Footnote 34 Texts like the Shepherd, which were popular among Christian readers in times other than our own, do not provide a window into some “original” Christianity but rather show one way that Christians conceptualized their relationships with God and one another.

Some scholars have noticed the frequency by which the Shepherd speaks of believers as enslaved, but have often treated it as less than central to the Shepherd’s key arguments. As Carolyn Osiek notes, the phrase “God’s enslaved persons” (οἱ δοῦλοι τοῦ θεοῦ) occurs “nearly fifty times in over thirty contexts throughout the Shepherd, an otherwise unusual expression.”Footnote 35 This expression, however, is not unusual for the Shepherd but rather is highly concentrated in the text compared with other early Christian literature. While there are instances, for example, of Paul talking about believers as enslaved to God (Rom 6:22), Mary as enslaved to God (Luke 1:38), and the recipients of John of Patmos’s visions as God’s enslaved persons (Rev 1:1), no other early Christian text contains such a sustained exposition of enslavement to God.Footnote 36

Various explanations have been offered. In his examination of Christian prophecy and Mand. 11, Jannes Reiling argues that enslaved persons in the Shepherd signifies all Christians, because it is an extension of a Septuagintal phrase, “my servants, the prophets” that depicts Hermas’s congregation as sharing in the prophetic lineage.Footnote 37 Lage Pernveden understands God’s enslaved persons in the Shepherd to be a bit of an oddity, arguing that usually Christ is depicted as an enslaved person (as in Phil 2:1–11) but that believers typically are not depicted as such.Footnote 38 Such a claim, however, both ignores evidence of other writers like Paul conceiving of believers as enslaved to God (as in Rom 6:22) and does not further our understanding of the Shepherd’s treatment of God’s enslaved persons. Beyond that, Erik Peterson reads God’s enslaved persons as a distinct subgroup of Christian ascetics to which Hermas writes who show concern for their own self-control.Footnote 39 In James Jeffers’s examination of the social context of the Shepherd in Rome, he argues that the text posits how “Christians owe God the same obedience that masters require of their slaves,” but makes clear that he only views it as metaphorical for Christian obedience.Footnote 40 Marianne Kartzow’s examination of enslavement via Conceptual Metaphor Theory in the Shepherd urges that we consider how enslaved persons might be impacted by how ancient literature uses them as bodies that are “thought with,” and how enslavement to God in the Shepherd might “hide problematic hierarchies” or “offer an alternative way for slaves to reimagine a different future.”Footnote 41

As recently as 2021, Jonathon Lookadoo’s introduction to the Shepherd does not mention those characterized as God’s enslaved persons, despite them being the recipient of the Shepherd’s commandments and parables via Hermas. Up to this point, the intersection of enslavement and the Shepherd has been almost exclusively discussed in relation to Hermas’s enslavement to Rhoda and the unknown man before her (Vision 1), or in relation to the parable of the vineyard (Similitude 5).Footnote 42 When God’s enslaved persons are customarily treated as a textual borrowing from the Hebrew Bible of believers as God’s “servants,” a specific subgroup of the text’s recipients, a merely metaphorical stand-in for “believers,” or are overlooked in favor of characters in the text that are enslaved to humans, the prominence of enslaved subject formation in the Shepherd is obscured.

As the work of scholars of early Christian history and thought like Chris de Wet and Jennifer Glancy have demonstrated in recent decades, the ubiquity and (in)visibility of enslavement in the ancient Mediterranean world impacts and is impacted by early Christian thought and practice, and leaves traces of these impacts in early Christian literature that can be analyzed.Footnote 43 The Shepherd is no exception, but provides an opportunity to explore more robustly how enslavement to a deity plays out discursively in early Christian literature. Early Christian literature, thought, and social relations were not only impacted by a “background” or “context” of the late Roman Republic and early principate, but were actively participating in and constitutive of its Roman colonial culture of enslavement. The Shepherd will help us see how some early Christians construct differences between enslaver and enslaved, utilize techniques of coercion or social control, and envision what virtues are desirable and actions are commendable.

Chapter Layout

To structure my analysis of how the Shepherd crafts the ideal Christian subject within and through the discourse of ancient Mediterranean slavery, I have divided this book into five chapters. Altogether, these chapters answer these three questions: What do God’s enslaved persons do that reveal their status as enslaved persons? How are believers enslaved? What effects does enslavement to God have upon the believer?

The first two chapters demonstrate that believers in the Shepherd are characterized as enslaved persons within the broader Mediterranean discourse of enslavement, with attention paid to particular behaviors and actions that are expected of the enslaved. The latter three chapters place the Shepherd’s treatment of the enslaver–enslaved relationship between God and believers in the context of spirit possession in the ancient Mediterranean. In doing so, I demonstrate that ancient discourses of enslavement and possession are intertwined in the Shepherd – that the crafting of the Christian subject as one of God’s enslaved persons occurs through possession by the holy spirit and the extensibility of God’s presence into the bodies of the enslaved.Footnote 44 While this analysis may be beneficial for other early Jewish and Christian texts, my focus here is primarily on the Shepherd.

To begin, I demonstrate that the Shepherd not only happens to use language associated with enslavement (such as δοῦλος or κύριος), but also that God’s enslaved persons are characterized in similar ways to other enslaved persons across the ancient Mediterranean. Chapter 1 focuses on particular characteristics that the Shepherd suggests God’s enslaved persons ought to have – the what of enslavement to God. While there are many characteristics that could be examined, I focus on three: usefulness, loyalty, and property. I choose these three because of their prevalence as characteristics associated with enslaved persons by enslavers writing in the late Roman republican and early imperial periods. My goal in this first chapter is to demonstrate that the Shepherd participates in a broader Mediterranean discourse of enslavement through how it envisions people who are enslaved to God as ideally making their bodies and actions useful for God’s will, being loyal to God, and functioning as commodifiable, exchangeable entities between divine beings.

Second, I turn my attention to one particular person enslaved to God: Hermas, the protagonist, narrator, and putative author of the Shepherd. I make this turn to demonstrate that some characteristics associated with enslaved persons do not apply to all of God’s enslaved persons in the Shepherd, but primarily to the actions of Hermas. Chapter 2 explores how Hermas is depicted as an enslaved literate worker who is involved in the textual production, dissemination, and reading of the visionary experiences and commandments that he receives from two divine figures. Like Chapter 1, this chapter demonstrates the what of enslavement and fleshes out how enslavement to God impacts the Shepherd’s account of its own textuality and authorship. I put the Shepherd in conversation with Cicero, Pliny the Younger, and Revelation to understand both how enslaved persons were utilized for their scribal skills by enslavers and how the Shepherd’s apocalyptic genre impacts how it centers and makes visible Hermas’s scribal labor. Hermas becomes a model of the ideal enslaved believer through his capacity to act as an enslaved literate worker, and gives us a glimpse into how early Christians who participated in elite literary production imagined the role of enslaved literate labor in the circulation of texts. Not only that, but this chapter introduces an important concept for the overall argument: how ancient enslaved persons could be conceptualized as a limb or extension of the enslaver’s body.

Having focused on various characteristics of God’s enslaved persons in the Shepherd, Chapter 3 focuses on human bodies as contested sites to better understand the means by which believers are enslaved (i.e., the how of enslavement). The chapter lays out the Shepherd’s anthropology and pneumatology, arguing that the text (like much ancient Mediterranean literature) envisions the body to be a porous entity that spirits can enter, exit, and inhabit. The Shepherd pairs spiritual possession with enslavement, characterizing the human as a vessel in which God’s holy spirit or other passion-causing spirits can dwell and can affect a person’s cognition, emotions, and actions. Here I point out how the holy spirit is explicitly depicted as an enslaver that dwells within God’s enslaved persons.

Chapter 4 deals with some of the implications of this anthropological and pneumatological model. In particular, I compare the indwelling holy spirit to the figure of the vilicus, the enslaved overseer in Roman villas who managed the estate and fellow enslaved laborers during the enslaver’s absence. I argue that the Shepherd deals with the common issue among ancient enslavers of how to surveil enslaved persons by implanting God’s presence within their very bodies. After this, I turn to one particular parable from the Shepherd that depicts an enslaved person working in a vineyard (Similitude 5) to explore how the Shepherd’s slavery-inflected anthropology and pneumatology have typically been overlooked, even when scholars examine the text’s most explicit narrative about an enslaved person. Usually read with an eye toward extracting Christological tenets from the parable, I offer a reading of portions of Sim. 5 that highlights how the Shepherd portrays the relationship between the enslaving holy spirit and enslaved flesh as one of idealized obedience motivated by the promise of reward.

Finally, Chapter 5 explores some of the implications of God’s enslaved persons possessing and being possessed by God’s holy spirit, moving from asking how believers are enslaved to asking about the effects of such enslavement to God. I consider how spiritual possession causes God’s enslaved persons to function as instrumental agents for God’s will as a consequence of God’s presence via the holy spirit. As a result of this enslaved instrumentality and possession of the human body, I analyze the Shepherd’s depiction of God’s enslaved persons in conversation with contemporary scholarship on agency among both enslaved and possessed persons, as well as the concept of “masterly extensibility” in classical scholarship. Such scholarship informs how I approach moments in the Shepherd where God’s enslaved persons might refuse to function as instrumental agents by examining how dependency and threats of death are utilized to encourage conformity to God’s will. Such an analysis of enslaved and possessed instrumental agency – and the risks associated with disobedience – lead me to the final portion of the chapter: the Shepherd’s call for individual conformity among God’s enslaved persons within the context of the Christian assembly. Informed by ancient architectural theory, I examine the two visions of a tower under construction that is built out of stones representing various types of believers (Vision 3 and Similitude 9). I suggest that the Shepherd envisions a future for God’s enslaved persons in which their very bodies are reshaped like stones to be useful in the construction of God’s house: the Christian assembly itself. In doing so, the stones representing God’s enslaved persons are physically molded to remove anything deemed undesirable by God and to create the appearance of a perfectly unified, white, seamless tower edifice out of enslaved bodies. This final section works to demonstrate that the Shepherd’s use of enslavement as a model for the ideal Christian believer extends beyond the individual and into the communal and ecclesiastical, conceiving of the church itself as assembled out of enslaved persons who conform to God’s will and take their proper place in the tower’s hierarchical unity.

In the conclusion, I summarize some of the main goals of the book and argue that the crafting of Christian subjects within the context of ancient discourses of slavery and possession is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, enslavement to God is depicted throughout the Shepherd as a relationship that produces a range of actions and behaviors that empower believers – God answers their prayers; they receive God’s power in order to master difficult ethical commandments and conquer creation itself; they protect themselves from passions and other evil entities; and they acquire life and are saved at the end of the world. Other forms of enslavement are critiqued as pale imitations of the most supposedly fruitful enslaving relationship in which one can be. On the other hand, enslavement to God is presented as the benevolent (and, in fact, the only real) alternative to death, and opportunities for freedom, manumission, and emancipation are not offered. The Shepherd paints a cosmological picture in which enslavement is the only option, such that survival depends upon being enslaved to God. In doing so, the Shepherd allows for enslaved persons to acquire some status and authority over their lives, but they are always limited by and constrained within their enslaved relational bond.

Before beginning this investigation, there are four introductory topics that are necessary to explain: (1) an introduction to Chris de Wet’s concept of doulology, which is central to my approach to the Shepherd’s discursive construction of ideal enslaved believers; (2) an overview of the Shepherd’s contents and widespread popularity among Christians; (3) a justification for why I focus this project regarding early Christian doulological discourse on the Shepherd; and (4) a brief examination of translations of terms related to enslavement in the Shepherd and my use of recent translational theory in and beyond biblical studies. By doing so, I hope to give readers some of the necessary information to understand the general narrative flow of the Shepherd, the rationale behind turning to a long visionary text to understand Christian ideals of enslavement, and the complicated legacy of how to translate the Greek terms δοῦλος (doulos) and κύριος (kurios).

Slavery: Definitions and Debates

What I do mean throughout this book when I talk about slavery or enslaved persons?Footnote 45 Many in New Testament and early Christian studies have turned to Orlando Patterson’s famous cross-cultural and sociological definition of slavery as a starting place: “The permanent, violent domination of natally alienated and generally dishonored persons.”Footnote 46 This definition highlights how enslaved persons are torn from their original sociocultural context, and sought to complicate earlier definitions of slavery that focused heavily on an enslaved person’s legal status as property (e.g., the 1926 League of Nations Slavery Convention).

In response, however, various ancient and modern historians have found Patterson’s definition lacking in the face of the diversity of historical manifestations of slavery across time and space. For example, David Lewis suggests that cross-cultural aspects of ownership (a right to possess, right to use, right to manage, right to transmit, etc.) can provide a helpful framework for historians who might then more deeply analyze who can own, who can be owned, and what ownership constitutes in particular historical contexts.Footnote 47 Scholars like Joseph Miller in particular have urged for renewed investigations into the particularities of historical manifestations of slavery. He offers slaving as a helpful term for understanding relationships not only between an enslaved person and their enslaver, but also with other parties (both enslaved persons and enslavers).Footnote 48 For Miller, slaving is a “motivated human action” and “was a particularly efficacious strategy of making a difference in people’s lives, thus generating historical processes.”Footnote 49 Both enslaved persons and enslavers are historical actors and social beings who respond to historical actions and experience forms of historical change through the process of slaving: people, rather abstractions like slavery or Christianity, affect other people’s lives.Footnote 50 While the enslaved–enslaver relationship between God and believers is central to this book, Miller’s call to better understand how both enslavers and enslaved persons built relationships and affected change on others beyond the hierarchical enslaved–enslaver dyad is significant for my analysis, since other parties are involved in the process.

My own approach to slavery will most closely follow the definition(s) offered by ancient historian Kostas Vlassopoulos, who splits the difference between the preceding legal, historical, and sociological camps. Vlassopoulos argues that slavery is “an agglomeration of three distinct but interrelated conceptual systems: of slavery as property, of slavery as a form of status, and of slavery as a cluster of related conceptualizations (modalities).”Footnote 51 These three conceptual systems, he argues, can be salient to varying degrees in different historical contexts of slavery and allow us to handle more robustly the range of historical uses for slavery. Perhaps most helpful for my analysis is that Vlassopoulos views slavery as fundamentally instrumental: “Slavery is a tool that enabled masters to do certain things” that varied in degree and direction.Footnote 52 He offers the term slaving strategies to describe the instrumentalization of slavery for labor, revenue, bureaucracy, and other purposes.Footnote 53 Much like Miller, Vlassopoulos emphasizes that the process of slaving affects historical change, and it is the type, degree, and consequences of that change that should be researched by historians. Slaving involves the instrumentalization of humans for particular purposes and assigning certain status markers to individuals, such that both the material and discursive deployment of slaving strategies are relevant to understanding how the lives of enslaved persons were affected.Footnote 54

Before moving on, there is one more definition from scholar of modern slavery Kevin Bales I think is significant for any analysis of slavery: “Slavery is, first and foremost, a state of being – not a legal definition, an analytical framework, or a philosophical construct.”Footnote 55 While definitional debates rage on, we ought not forget that conceptualizing the boundaries, experiences, effects, and rationales for slavery were (and are) the conditions under which millions of humans have lived and died. While this book is focused heavily on how the discourse of ancient Mediterranean slavery shaped the subjectivities and ethics of early Christians, this discourse emerged through historical processes of domination, exploitation, and physical and psychological violence. The lives of those individuals should not be forgotten as we investigate how early Christians made sense of their world and themselves through enslavement to God.

Doulology and Moving beyond Mere Metaphor

As the Christian subject was constructed in part on the model of enslaved persons, the language of early Christian literature participates in a discourse of slavery. The normalization of language of enslavement to God in biblical and early Christian literature shows how Mediterranean slavery was so deeply ingrained that it became nearly invisible or unnotable – “slave of God” or “servant of God” became so normalized and common that a reader would not think twice about what the phrase implies. To expose this invisibility, the Shepherd gives me an opportunity to ask a question that Marisa Fuentes asked of eighteenth-century urban Caribbean slavery: “[H]ow do slaveholders’ interests affect how they document their world, and in turn, how do these very documents result in persistent historical silences?”Footnote 56 This is one of many early Christian texts that exist within an ancient version of what Saidiya Hartman calls the “archive of slavery” whose foundation upon violence “determines, regulates and organizes the kinds of statements that can be made about slavery as well as creates subjects and objects of power.”Footnote 57 The Shepherd may not, on its surface, appear like a text that belongs in an “archive of slavery”; it is not, for example, an Antebellum plantation owner’s handbook on how to treat enslaved persons or an ancient economic treatise on household or agricultural management. Nevertheless, the Shepherd participates in a common discourse of enslavement, presenting readers with a particular vision for the enslaved–enslaver relationship that attempts to delimit what type of relationship(s) with deities, spirits, and other humans should be possible, thinkable, or profitable, as well as what behaviors and actions make an ideal enslaved person. Better understanding how early Christian literature like the Shepherd handles the topic of enslavement, as Jennifer Glancy suggests for early Christian literature more broadly, might help expose and allow us to challenge both ancient and contemporary ideas about exploited labor and disposable bodies: “To correct the distorting traces of slaveholding values that linger in Christian thought and practice, it is first necessary to acknowledge how thoroughly early Christians internalized the values of the wider society.”Footnote 58 Enslavement to God in particular has cast a long shadow over contemporary Christian vocabulary, practices, and conceptions of the divine that deserves scrutiny.

As we will see throughout this book, the Shepherd is a text baked in a culture of enslavement and, like much early Christian literature, written with the enslaver’s values and interests in mind.Footnote 59 Those who read the Shepherd are encouraged to accept its discursive treatment of slavery – including its assumptions about the normalcy of unfree labor and bodily exploitation under God – as the way that the world works. Rather than “devise formulas to repress the unthinkable and to bring it back within the realm of accepted discourse,” I ask that we more directly encounter and wrestle with the portrayal of God the enslaver and believers as enslaved in the Shepherd.Footnote 60 My hope is that my analysis of the Shepherd is but one contribution that helps urge further examination of the embeddedness of language, practices, and discourse of slavery in early Christian literature and their lingering effects. The language that early Christian literature uses shaped (and still shapes, to a degree) material and discursive practices in the world, and so the ongoing struggle to unthink the embeddedness of enslavement and mastery in the world that we have inherited requires bringing to light just how pervasive it is.Footnote 61

Much scholarship on what it means to be a “slave of God” or “slave of Christ” in New Testament and other early Christian literature has centered around claims of metaphor and determining the origins of this presumed metaphor. This book does not presume that enslavement to God is merely metaphorical, but builds upon Chris de Wet’s model of doulology (discussed and defined below) to argue that the crafting of the Christian subject occurs within the ancient Mediterranean discourse of slavery in the Shepherd.

Biblical scholars tend to start from the assumption that being a “slave of God” or “slave of Christ” – a claim that figures like Paul and John of Patmos make about themselves – is a metaphorical claim. That is to say, their relationship to God is akin to but distinct from “real” enslavement and its traits or realities experienced by other ancient Mediterranean people. Building upon this assumption, much scholarship focuses on determining the origins of the metaphor of enslavement to God or Christ. This is perhaps best summarized by John Byron’s scholarship on Paul, in which he helpfully summarizes the status quo of decades of research between those who read the Greek term doulos as stemming either from a Jewish or Greco-Roman milieu:

(1) The phrase, an honorific title found in the LXX, has been borrowed by Paul from stories about the patriarchs, Moses, David and the prophets; and (2) the phrase is a symbolic adoption taken from Greco-Roman slavery and illustrates that Paul is in a similar relationship with Christ.Footnote 62

Against arguments that favored a Greco-Roman background for Paul’s use of slavery as a metaphor based on funerary inscriptions and Roman law, Byron suggests that Jewish texts from the Second Temple period and the Septuagint best explain how Paul and other early Christians could conceptualize enslavement to God or Christ. In cases like Byron’s, the application and consequences of language of enslavement to God or Christ are downplayed in favor of excavating where figures like Paul acquired this type of language. Additionally, as J. Albert Harrill notes in his review of Byron’s Slavery Metaphors, a “totalizing interpretative framework that sets up an artificial cultural dichotomy between ‘Judaism’ and ‘Hellenism’ as code words masquerading as historical entities” may in fact hinder scholarship on how ancient Mediterranean writers talk about enslavement to God.Footnote 63 Rather than attempting to trace a genealogy of language of slavery that works to reinforce what counts as “real” Jewishness, Greekness, or Romanness, we might pay more attention to how this language and discourse is deployed, as well as its aims and effects.

Such metaphorization tends to treat enslavement to a deity as something that is internal, spiritual, religious, or not-real in some social or material capacity.Footnote 64 For example, in Slave of Christ, Murray Harris distinguishes “literal or physical slavery” from “metaphorical or spiritual slavery.” The former, he claims, is an “outward relationship” between two people, whereas the metaphorical latter is an “inward relationship, where a person is under the sway of another person (e.g., ‘a slave of Christ’).”Footnote 65 By dividing types of enslavement this way, Harris both treats divine figures like Christ as distinctly incapable of enslaving and perpetuates outdated conceptions of religious devotion as internal, mental, and disembodied.Footnote 66 Similarly, Marianne Kartzow’s analysis of slavery through Conceptual Metaphor Theory leads her to argue that there is often a tension in early Christian literature between metaphor and social reality, but nevertheless suggests that enslavement to Christ “was considered an honor and normally did not affect his or her physical body, social status, or life conditions.”Footnote 67 Again and again, the claim that slavery to God or Christ is merely a metaphor leads scholars to claim that such enslavement is internalized in ways that do not actually impact the lives of believers. Slavery to God or Christ is made something that cannot touch or transform the body, but is simply analogical language for spiritual submission.

By spiritualizing and metaphorizing enslavement, such a treatment of enslavement to God or Christ avoids the discomfort of viewing believers as coerced into an enslaved–enslaver relationship, overlooks the possibility of enslavement impacting more than just the inner self, as well as downplays the commodification of enslaved persons to mere internal, mental persuasion. Additionally, as Chris de Wet has argued, metaphors depend upon “an explicit measure of difference between the so-called source domain … and the target domain.”Footnote 68 To speak of something like slavery as a metaphor requires there to be something that is enslavement as the source domain (e.g., slavery in the Roman Empire) and something that is not-enslavement as the target domain (e.g., a believer’s relationship to God). What if some early Christians did not understand themselves to be comparing their not-enslavement experience as an obedient believer to enslavement, but rather understood themselves to be enslaved to God? What if this is not a metaphorical comparison between enslavement and not-enslavement, but rather between two related forms of enslavement? Enslavement to a deity, I suggest, must have some impact on the crafting of believers beyond being a catchy phrase to metaphorically compare their devotion to God or Christ to that of the enslaved.

Paul has been a prominent point of discussion given his own self-identification as an “enslaved person of Jesus Christ” (δοῦλος Χριστοῦ Ἰησοῦ; Rom 1:1, Phil 1:1) in various letters, as well as his treatment of enslavement and freedom in Rom 6, 1 Cor 7–9, and Gal 3–4. Richard Horsley, for example, suggests that Paul’s own enslavement to Christ is important to Paul’s “symbolic universe” and functions as an “organizing metaphor,” but that it is unclear if the term doulos always meant “slave” to Paul.Footnote 69 Especially since doulos is a term that Paul usually (but not exclusively) uses to describe himself, Horsley suggests that doulos functions more as a “designation of his own relation with Christ as a specially designated apostle … perhaps even in a semi-titular sense.”Footnote 70 He even goes so far as to describe Paul’s titular identity as a doulos of Christ as something that is distinct from the “master–slave” relationship of antiquity, since the “title has the primary sense of political ruler, not of slave–master.”Footnote 71 Such an argument not only overlooks instances in which believers are, in no uncertain terms, characterized by an enslaved–enslaver relationship to God or Christ (e.g., Rom 6:16–22), but also follows a standard line of scholarship that euphemizes or metaphorizes language of enslavement.Footnote 72 Stanley Stowers’s response to Horsley’s article, while highlighting that Horsley may be painting too clear of an anti-imperial picture of Paul, ends up agreeing that there is:

No direct correlation between such language and the institution of chattel slavery. Horsley is surely right that the image is often a moral or other sort of metaphor that does not imply a clear idea of slavery to Christ.Footnote 73

Through this short survey of some common approaches to slavery to God or Christ in New Testament literature – especially in relation to Paul – we see a scholarly interest in: (1) determining the origins of the so-called slave metaphor and (2) a treatment of enslavement to deities that often falls into binary models of “real,” embodied, life-altering, human-to-human enslavement and “spiritual,” disembodied, internal, not-life-altering enslavement to God or Christ. I find these models and conclusions unsatisfactory for understanding how enslavement to a deity changes the bodies, actions, behaviors, and lives of those who were called upon to be God’s enslaved persons in the Shepherd of Hermas and in other early Christian literature.

With some of the prominent ways that scholars have approached enslavement to God or Christ discussed, we can turn to Chris de Wet’s concept of doulology. Above, I have used terms like “discourse” and “discursive” without explicitly explaining what I mean by them, so I want to pause here to offer some definitions and highlight how these terms will be used throughout the book. Discourse, as John Fiske phrases it, is a material and linguistic process that:

Challenges the structuralist concept of “language” as an abstract system (Saussure’s langue) and relocates the whole process of making and using meanings from an abstract structural system into particular historical, social, and political conditions. Discourse, then, is language in social use … It is politicized, power-bearing language employed to extend or defend the interests of its discursive community.Footnote 74

In other words, my use of “discourse” and “discursive” presumes that language occurs within sociopolitical contexts and is capable of normalizing particular habits and justifying particular institutions or systems through language. Within my own project, I treat enslavement as a discourse that is tied to the historical, social, and political practices and realities of enslavement, as well as to the ways that elite Greek and Roman writers wrote about the enslaved and enslavers. Put differently by Matthew Elia in his examination of Augustine’s treatment of enslavement: “What if the tradition’s widespread uses of slavery qua symbolic resources cannot be as neatly separated from its approach to slaveholding qua social institution as we usually assume?”Footnote 75 Discourse and the logics of enslavement upon which it functions in the Shepherd are central to how the text offers particular models of the ideal subject and delimits what practices or ideas ought to be acceptable for a believer.

I rely particularly upon Chris de Wet’s scholarship on early and late ancient Christian discourse of enslavement for my project. Building upon the work of Michel Foucault, de Wet coined doulology to refer to:

That enunciative process in which slavery and mastery operate together as a concept ‘to think/communicate with’ – in this process, knowledge and behaviors are produced, reproduced, structured, and distributed in such a way as to establish subjects in/and positions of authority and subjugation, agency and compulsion, ownership and worth, honor and humiliation, discipline and reward/punishment, and captivity and freedom.Footnote 76

Slavery, then, is not merely a sociopolitical phenomenon or a religious metaphor, but a system by which ancient Mediterranean historical actors shaped their material and intellectual worlds that were “embedded in and constitutive of early Christian religious thought.”Footnote 77 Enslavement as a discourse works to craft particular types of subjects as enslaved or enslaver through encouraging or discouraging particular actions and behaviors, using both the practices of enslavement and literary treatment of enslaved persons as its scaffolding. As de Wet notes, doulology in early Christianity impacted the development of Christology, the Trinity, cosmology, pneumatology, hamartiology, soteriology, eschatology, and ascetic practice.Footnote 78 This book does not focus on each of the aspects that de Wet raises, but emphasizes especially how doulological discourse impacts the Shepherd’s treatment of the believer as an idealized enslaved person from the enslaver’s perspective, the role of spirits and anthropological portrayal of the human body, as well as ecclesiology, theology, and agency.

The Shepherd aims to prescribe, inculcate, and advocate for particular sets of characteristics, habits, ethics, or obligations of the enslaved that enslavers in the ancient Mediterranean deemed beneficial. In doing so, the Shepherd participates in doulological logic, functioning as just one window into how antiquity’s enslaving class concocted an “ideal” enslaved person and how ancient literature normalized hierarchical relations. Doulology is laid out through the instruments and actions by which the enslaver imposed their will upon the enslaved. In these cases, we glimpse how Greek and Roman enslavers and elite writers construct certain strategies for management, social control, punishment, reward, and agency.Footnote 79 The chapters of this book deal in different ways with how God and the holy spirit in the Shepherd are prime examples in early Christian literature as to how divine beings can function as enslavers and coerce enslaved persons for their own desires, as well as how God’s enslaved persons are depicted according to despotic logics.Footnote 80

The normalization of slavery as an economic, symbolic, material, and discursive structure in the Shepherd and across the ancient Mediterranean might be thought of in terms of Pierre Bourdieu’s “paradox of doxa.” In short, Bourdieu defines doxa as presuppositions that are so taken-for-granted or self-evident that they are hardly questioned and often determine the limits of what is possible or thinkable – that which “goes without saying because it comes without saying.”Footnote 81 Such doxa are constructed through one’s habitus, a set of dispositions one accumulates and perpetuates based on social location, certain behaviors, beliefs, and social norms that become further solidified.Footnote 82 Doxa are so fundamental that opposing sides of an argument agree upon them as the rules of the game within which discourse happens.Footnote 83 In this case, early Christians and other Mediterranean historical actors who participate in the social life and ideologies of slavery often viewed enslavement as simply part of how the world works. Even texts that might debate individual instances of enslavement, such as Seneca’s famous epistle on the humanity of enslaved persons, do not challenge the practice of enslavement en masse.Footnote 84

Practices, ideologies, and logics of enslavement existed in multifarious forms throughout the Mediterranean and touched almost all aspects of a person’s life, since one would encounter enslaved persons in homes, temples, markets, doing agricultural labor, scribal and bureaucratic labor, extracting natural resources, maintaining cultic and civic institutions, and more.Footnote 85 The way that slavery materially and discursively functioned would likely be recognizable to enslaved persons, formerly enslaved persons, and free persons alike. Those dwelling within the elite’s habitus would view enslavement to deities as simply part of how the world is organized, while others (especially enslaved persons) might challenge the normalcy of enslavement as a cultural practice. I do not want to claim that the writer of the Shepherd is solely or uniquely to blame for its treatment of enslavement to God, since it is difficult to pinpoint a single culpable historical agent who is functioning within their doxic realm of what is thinkable.Footnote 86 Rather, the Shepherd is merely one of the possible paths I am following in order to analyze, expose, and critique how early Christians often participated in the going order of things.

Overview of the Shepherd

A brief introduction to the Shepherd of Hermas is necessary in order to provide an understanding of the text in broad strokes for the rest of the book. I will offer this overview of the Shepherd in three segments: the structure and content of the Shepherd, the manuscript tradition, and the entangled problem of date and authorship.

The Shepherd has three primary sections: five Visions (Vis.), twelve Mandates (Mand.), and ten Similitudes (Sim.).Footnote 87 The first four Visions contain interactions between the narrative’s protagonist, a man named Hermas, and a woman who reveals to him his sin and urges him and his household to repent. The narrative opens with Hermas encountering the woman who had enslaved him, Rhoda, bathing in the Tiber River. (In one of the Latin traditions, however, Rhoda is an enslaved person alongside Hermas.)Footnote 88 While Hermas tells his readers that he thought of her as a sister and a goddess, Rhoda appears in a heavenly vision to rebuke him for his lustful thoughts about her. Hermas is shaken to his core, leading him to ask: “If even this sin is recorded against me, how can I be saved?”Footnote 89

Hermas then encounters another woman who both comforts and reprimands him for his sin. Hermas encounters this woman in multiple visions over the span of a year, occasionally listening to and copying words from a book that she carries so that he can pass on her message to named figures (Maximus; Clement; Grapte). A young man appears to Hermas and reveals the woman’s identity as the Assembly.Footnote 90 Vis. 3 contains the first of the two tower visions, in which Hermas and the woman watch young men build a tower from stones dragged out of the water. The Assembly explains that the tower represents the Assembly herself and that salvation comes from being built upon the water, as well as what types of people the stones represent and what virtues the women who support the tower embody. This tower vision and its later counterpart (Sim. 9) are particularly important for my analysis, since the tower itself is presented as “God’s house,” a physical embodiment of the assembly of believers and an eschatological work-in-progress.Footnote 91 The tower is the edifice in which all believers need to be incorporated if they want to experience eternal life with God. The construction of the tower out of stones is used allegorically by the Shepherd to clarify what types of behaviors and actions allow one to enter the tower, as believers are encouraged to “mend your ways while the tower is still being built.”Footnote 92 As we will see throughout this book, the types of behaviors expected of believers in order to be incorporated into the tower participate in doulological discursive logics, requiring one to become a particular type of enslaved subject in order to be the “correct” type of stone for the tower’s construction. After the first tower vision, Hermas then travels on the Campanian Way and encounters a beast with a head like a ceramic jar, but is emboldened by a divine voice telling him to avoid being doublesouled.

The Visions end with the introduction of a new character: the Shepherd, also known as the angel of repentance.Footnote 93 The Shepherd claims that Hermas has been entrusted to him in order to revisit the main points of what he previously saw, and instructs Hermas to write down the commandments and parables for himself and an unnamed audience – later identified as God’s enslaved persons.Footnote 94 The Shepherd then turns to the second major section, the Mandates. Here, we are presented with a mixture of the Shepherd’s monologue about various topics and dialogues between the Shepherd and Hermas when the latter interjects with questions. The Mandates cover a variety of themes: God as creator (Mand. 1), simplicity and innocence (Mand. 2), truth (Mand. 3), marriage and adultery (Mand. 4), irascibility (Mand. 5), double-souledness (Mand. 9), grief (Mand. 10), prophecy (Mand. 11), and desire (Mand. 12). The Mandates also include a distinct section dedicated to expanding upon Mand. 1’s call for Hermas to “be loyal to him [i.e., God] and fear him and, while fearing him, be self-controlled.”Footnote 95 Mand. 6–8 explain how each of these three qualities are twofold, in that a person can be loyal, fearful, or self-controlled toward either proper things or improper things.

The Shepherd ends with ten Similitudes, a series of further visions and teachings between the Shepherd and Hermas. The Similitudes that I will deal with most extensively in this book are 1, 5, and 9. Sim. 1 discusses how God’s enslaved persons dwell in a foreign country under a foreign ruler, but ought to prepare themselves to return to God’s city. Sim. 2–4 deal parabolically with the relationship between rich and poor people, as well as how the coming age will reveal who is righteous and who is not. Sim. 5 includes a parable about an enslaver leaving an enslaved person to tend to his vineyard, which the Shepherd tells to Hermas in order to clarify what proper fasting looks like. The parable is followed by various explanations of the scene, including who each character represents (e.g., the enslaver = God; the vineyard = God’s people; the son = the holy spirit; the enslaved person = God’s son; Sim. 5.5 [58]), and a further description of the relationship between spirit and flesh. Often, Sim. 5 is latched onto by scholars of early Christianity in order to tease out the Shepherd’s Christology. Sim. 6–7 deal with two additional shepherds – the angel of luxury and angel of punishment – who treat their flock accordingly in order to lead them toward or away from repentance. Hermas himself is tormented by the angel of punishment as the paterfamilias and representative of his family.

Sim. 8 depicts Hermas and the Shepherd viewing various people carrying branches from a willow tree. When the branches are meant to be returned, they represent the types of people who held them – some fully green, some withered to various degrees, some moth-eaten. They are re-planted in order to see which will survive and, by extension, which people have kept God’s law. Sim. 9 is a retelling and expansion of the first tower vision (Vis. 3), in which Hermas is swept away by the Shepherd to Arcadia in central Greece and sees stones quarried from twelve mountains. Each of the mountains, much like the stones pulled from the water in Vis. 3, represent various types of people who may or may not be incorporated into the tower.Footnote 96 Those who are incorporated bear the names of twelve virtuous women who help construct the tower, whereas those who do not are carried off by women representing twelve vices in order to die. Sim. 10 concludes the Shepherd with Hermas, the Shepherd, and the angel who handed Hermas over to the Shepherd meeting in his house. The angel tells Hermas that the Shepherd and the twelve virtuous women from the tower scene will live with him and support him as he keeps his household clean.

The Shepherd was a popular text in the ancient Mediterranean among Christ-followers. As Malcolm Choat and Rachel Yuen-Collingridge note in their examination of pre-Constantinian attestations of the Shepherd in Egypt: “It is by far the best-attested Christian work except those eventually established as canonical; indeed, in the first few centuries its attestation is considerably better than that of some of the canonical books.”Footnote 97 Likewise, Larry Hurtado pointed out that the Shepherd is the most well-attested Christian text in our manuscript records from the first few centuries except for the Psalms and the gospels of Matthew and John.Footnote 98 Frustratingly for scholarship on the Shepherd, no ancient Greek manuscript that survives has more than roughly one-third of the entire text; our most complete attestation of the Shepherd in Greek is Codex Athous Grigoriou 96, a fourteenth-century manuscript.Footnote 99 However, the Shepherd’s popularity and extensive readership is apparent through the various languages into which it was translated and by which it was transmitted across the ancient and medieval world: two Latin translations (called Vulgata and Palatina); four Ge’ez manuscripts; two Coptic translations; a Middle Persian fragment used by Manichaeans in northwestern China, a Georgian translation (likely via a lost Arabic translation) that attributes the text not to Hermas, but to the Syrian ascetic Ephrem; an Armenian fragment used to elucidate a passage in James that attributes the Shepherd to “father Pimen”; and a patristic florilegium that refers to the text as coming “from the apocalypse of St. Germanos” (ἐκ τῆς ἀποκαλύψεως τοῦ ἁγίου Γερμανοῦ).Footnote 100 Each of these transmissions of the Shepherd attest to the broad range of Christian (and Manichaean!) readers that read and interacted with the text as it spread across Afroeurasia.

The questions of the Shepherd’s date and authorship are entangled, since pinpointing one inevitably impacts the other. The widest range of dates for the composition of the Shepherd extend from 70–140 CE.Footnote 101 It has often been dated based on who early Christians hypothesized was its author. Origen, for example, argued that the Hermas of the Shepherd was the colleague of Paul named in Rom 16:14, which has led some scholars to propose first-century dates for (at least part of) the text.Footnote 102 The Muratorian fragment – a text likely forged in the fourth century that represents itself as a second-century work – named Hermas as the brother of bishop Pius I of Rome in the mid second century, leading some to propose an early or mid second-century date for the Shepherd.Footnote 103 Over the last couple of centuries, various academic proposals have arisen for the Shepherd’s multiple authorship or single authorship, with debates raging on as to how many redactional layers the text contains.Footnote 104 I do not focus too intently on source or redaction criticism in this book. Rather my focus is on the Shepherd’s language of enslavement and on how ancient readers may have understood the text in light of Mediterranean discourse and logics of enslavement. At times, textual variants and scribal changes will offer other avenues for interpretation that I will note. I leave open the possibility for multiple authors or redactions, and focus instead on the interaction between a reader cognizant of language of enslavement and the extensive textual remains of the Shepherd.

Why the Shepherd of Hermas?

Why focus so much on the Shepherd of Hermas, a text that is not part of any biblical canon today and that nonspecialists in early Christian studies have perhaps never heard of, let alone read? I find the Shepherd helpful early Christian literature to think with because of its immense popularity and status in the early Christian period. Along with being transmitted and read throughout Afroeurasia well into modernity, it was notable as a text read in churches and used for catechesis into and beyond the fourth and fifth centuries – and some may have in fact classified it as a biblical text.Footnote 105 Christians throughout the Mediterranean copied, read, and heard the Shepherd, often finding it valuable enough to share with others and continually transmit. The Shepherd was an educational tool for some late ancient Christians because its investment in subject formation is central: it is worth focusing on this text to better understand what type of behaviors it urges Christians to exhibit, how it depicts the relationship between believers and God, how believers’ subjectivities are crafted around discursive ideals for enslaved persons, and how it envisions ecclesiastical community based on a model of enslavement. Even if the Shepherd is deemed a marginal, obscure, or somewhat boring text today, it was not always so and deserves attention given its weighty presence in ancient Christian circles. The Shepherd might teach us about how early Christians used the scaffolding of the Mediterranean world and its institutions to concoct its understanding of God, spirits, humans, virtues, vices, life, and death.Footnote 106

Understanding slavery in the Shepherd is important because of the role that this text had in the molding of Christian ethics and identity in late antiquity. As the Shepherd was copied, translated, and transmitted from Ireland to China throughout the late ancient and medieval periods, we find that one of the sections of the text that receives the most attention is the Mandates – the section that coincidentally has the highest rate of language pertaining to enslavement in the text.Footnote 107 This set of commandments is known to fourth-century writers as part of the instructional repertoire for Christian communities that aids catechumens in learning about Christian ethics and practice. For example, the church historian Eusebius of Caesarea considered the Shepherd necessary for “introductory teaching” (στοιχειώσεως εἰσαγωγικῆς) of new Christians; bishop Athanasius of Alexanderia considered the Shepherd helpful reading for “those who newly join us and want to be instructed in the word of piety” (τοῖς ἄρτι προσερχομένοις καὶ βουλομένοις κατηχεῖσθαι τὸν τῆς εὐσεβείας λόγον); prominent Alexandrian teacher Didymus the Blind referred to the Shepherd as “the book of catechism” (τῷ βίβλιῳ τῆς κατηχήσεως).Footnote 108 In stark contrast to modern scholarly complaints about the Shepherd’s mediocrity or monotony, late ancient Christians found the Shepherd to be a powerful tool in crafting Christian subjectivity and shaping the behaviors of new Christians by introducing them to the ethical basics through this text.

The monastic afterlife of the Shepherd also reveals the relationship between logics of enslavement and of asceticism pointed out by Jennifer Glancy, which offer us a potential trace of “the effects of slaveholding in ancient Christian sources and evidence,” such that “ascetic Christians learned to treat their own bodies as slaves.”Footnote 109 By the sixth or seventh century, a Palestinian monastic writer transplanted the ethical teachings of the Mandates into a text entitled the Teachings for Antiochus (Praecepta ad Antiochum), which depicts Athanasius of Alexandria teaching the future monk Antiochus how to live a self-controlled and reverent life through a cut-and-paste version of the Mandates.Footnote 110 The teaching of the Mandates in the Teachings are not attributed to the Shepherd, nor even necessarily to Athanasius, but rather are called “every single commandment of the teachings of Christ” (μίαν ἑκάστην ἐντολὴν τῶν διδαγμάτων τοῦ Χριστοῦ).Footnote 111 Similarly, the Georgian transmission of the Shepherd treats the Mandates and Similitudes as God’s angel-mediated commandments given to the famous Syrian ascetic Ephrem, meant for the salvation of repentant Christians.Footnote 112 Late ancient monastic interest in the Mandates (and Similitudes) diverges from modern scholarly interest in the Visions. Whereas the latter view the text as a site for uncovering the narrator Hermas’s biography, exploring the role of the Assembly as a female divine interlocutor, and contextualizing Hermas’s visionary experiences via scholarship on lived religion,Footnote 113 late ancient Christians and ascetics found the text valuable for education, monastic inculcation, and forging the relationship between piety and slave-like bodily discipline.

While we do not know all of the on-the-ground details of how the Shepherd was used by late ancient Christians to instruct new members, it is noteworthy that the portion that most heavily explores what it means to be a “good slave” for God was so often transmitted, quoted, commented upon, and even imagined to be Jesus’s own teaching. The Shepherd’s words were attributed not only to Hermas, but also on occasion to Jesus, Paul, Ephrem, and Germanos, suggesting that the Shepherd’s vision for ethical instruction and Christian subject formation remained meaningful and useful centuries after its composition.Footnote 114 The continued transmission of enslavement to God as a norm and goal for Christian life and how it could impact the material, social, and spiritual lives of both free and unfree believers urges me to explore why enslavement was such an important discursive model for the Shepherd.

One last rationale for focusing on the Shepherd is because of Hermas himself. Although he has been deemed a formerly enslaved person in most academic literature of the last 150 years, I have argued elsewhere that this assumption stands on shifting ground; Hermas may in fact be presented as still enslaved in the Shepherd.Footnote 115 Given the paucity of early Christian literature that explicitly claims to be written by enslaved or formerly enslaved persons, texts like the Shepherd present us with an opportunity to consider how the conditions of enslavement may have affected how the Shepherd’s writer conceptualizes the effects of slavery within the text.

Translating the Enslaved and Enslavers

Finally, I want to give the rationale behind my translational choices throughout this book. My approach to Greek terms is influenced by a range of feminist and womanist translational theories, especially for the long and complicated history of translating doulos (δοῦλος). Translation is a practice of meaning-making capable of “affect[ing] real human lives” and exposing the worlds for which translators advocate.Footnote 116 I aim to translate in a way that foregrounds how traces of enslavement stick to semantically capacious Greek terms. Put differently, I translate under the assumption that slavery stains words in a way that might be heard innocently or maliciously depending on one’s positionality within the Mediterranean world. Even if the writer did not always intend for enslavement to be the referent when using a particular term, that does not bar a reader or hearer from receiving the term as such; language carries histories, resonances, and connotations that can be foregrounded and encountered by readers no matter the intention of a given writer.Footnote 117 Throughout this book, I attempt to follow suggestions for language regarding enslavement offered by a community-sourced guide produced by senior slavery scholars of color that denaturalizes how we “describe and analyze the intricacies and occurrences of domination, coercion, resistance, and survival under slavery.”Footnote 118 I tend to use language like (formerly) enslaved person and enslaver rather than slave and slaveowner so as to highlight that enslavement is a forced condition and status, rather than a naturalized or essentialized mode of being.

Central to a wave of scholarship that recognizes that translations are never neutral were (and are) womanist scholars. In particular, Clarice Martin’s “Womanist Interpretations of the New Testament” built upon the burgeoning womanist scholarship of the 1980s and persuasively argued that white male biblical interpreters often exhibited linguistic racism and sexism that needed to be undone: translators, she argued, ought to recognize the raced, sexed, and classed nuances of their work.Footnote 119 Through an examination of English dictionaries and Greek lexica, Martin suggests that translating doulos as “servant” rather than “slave” does two things. First, she notes that it “would promote an unrealistic and naively ‘euphemistic’ understanding of slavery” that substitute the offensiveness of the term slave for a less politically charged word.Footnote 120 Secondly, Martin notes that the translation of doulos as servant “minimizes the full psychological weight of the institution of slavery itself,” allowing enslavement in antiquity to appear guised as a normal or inevitable part of life – something that could not be imagined otherwise.Footnote 121 To normalize ancient enslavement by lessening it to an institution that is less-than-enslavement or wholly separate from African and Indigenous enslavement in the early modern and modern eras would allow for the proliferation of stereotypes about the “benevolent masters” and “happy slaves” of antiquity.Footnote 122

Likewise, Wilda Gafney’s notes on womanist translational approaches to the Hebrew Bible reflect on how translation is “the first layer of biblical interpretation” that in Western scholarship is too often presumed to be neutral and transparently express the author’s intent.Footnote 123 Gafney explains how her translational techniques allow her to “assign meanings based on lexical values, not on religious or contemporary cultural traditions, even if it results in a theologically undesirable or untenable outcome.”Footnote 124 I find such an approach to translation helpful for how it allows us as translators–interpreters of the Shepherd and other Christian literature to wrestle with how believers are portrayed as God’s enslaved persons, despite the theological or ethical discomfort such a translation might rightly cause. Womanist scholars call not only for translations of terms like doulos that no longer mask the realities of ancient enslaved persons, but also for such translations to help us overcome misguided and harmful stereotypes about marginalized people in antiquity and today.

I do the same translational work with the Greek terms κύριος (kurios) and κυρία (kuria) – often translated in the Shepherd as “master,” “lord/Lord,” or “sir/lady” – by defaulting toward a translation of “enslaver” and very occasionally “master.” This term is used throughout the Shepherd to refer to Rhoda, the Assembly, the young man of Vis. 4, the Shepherd, and God.Footnote 125 Kurios is a slippery term that can be translated as a title of deference for a social superior (e.g., “sir,” “lady”), but is also used as the antithesis of a doulos – that is, denoting an enslaver.Footnote 126 I make this translational move, in part, to undercut the ubiquity of and familiarity with the term “Lord” as applied to God (and, in other Christian literature, to Jesus) and to more clearly place the term in the discursive context of enslavement.

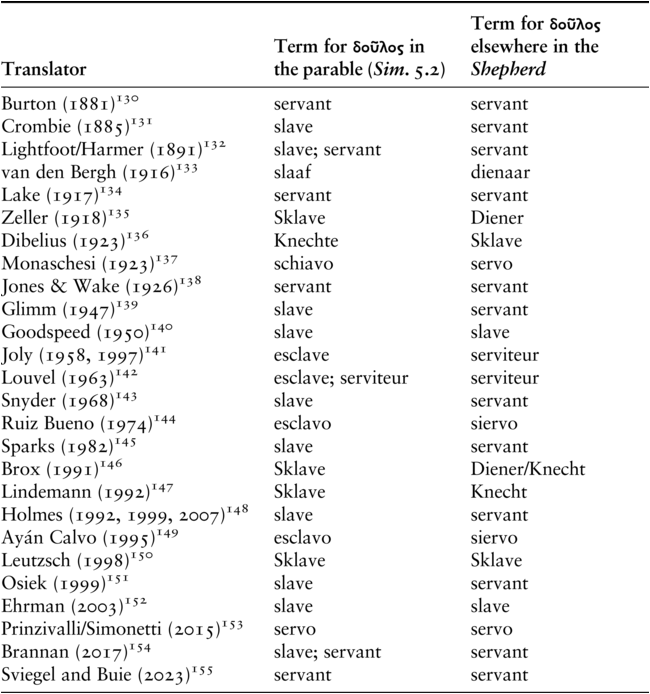

Part of the reason, I argue, that the topic of enslavement in the Shepherd has been overlooked by scholarship is a broader discomfort with the reality of and brutality of the institution of slavery in antiquity. Such discomfort has often led scholars to translate the Greek term doulos or the Latin term servus as “servant” rather than “slave,” thereby masking the ubiquity of enslaved persons and the institution of enslavement in the world early Christ-followers inhabited.Footnote 127