The forest is alive. It can only die if the white people persist in destroying it. If they succeed, the rivers will disappear underground, the soil will crumble, the trees will shrivel up, and the stones will crack in the heat. The dried-up Earth will become empty and silent. (…) We will die one after the other, the white people as well as us. All the shamans will finally perish. Then, if none of them survive to hold it up, the sky will fall.

(Kopenawa & Albert, Reference Kopenawa and Albert2019)Prologue

The epigraph above is a quotation from a Yanomami shaman, David Kopenawa, who lives in the Amazon Forest in Brazil. Kopenawa’s book The Falling Sky is full of stories from Yanomami people, about the forests and spirits (the Xapiri) who inhabit the forest. The book has become a strong symbol in the struggles to protect the environment and the “forest people” throughout Latin America. Kopenawa’s words convey a narrative that many environmental educators can intuitively understand and promptly relate to. “The forest is alive”: rainforests possess astonishing biodiversity, showcasing an extensive and complex web of relationships between cohabitants of this living world that make its existence as a biome possible. We can also understand who they refer to when Kopenawa speaks about white peoples’ persistence in destroying the forests. And it is clear what it means to say that the “sky will fall.” The meaning behind those wise words might be familiar to many readers of the Australian Journal of Environmental Education. This is a simple narrative that conveys enormous meaning with a powerful take-home message.

Nonetheless, we believe we are not alone as environmental educators, when we affirm that the environmental challenges of our times often feel so unsurmountable that one can easily feel hopeless in terms of “how to start” or “what to prioritize” in pre-service teacher education; especially given the case that we are often teaching condensed courses that span only a couple of months. Which narratives should we prioritise when approaching the many, interconnected challenges of our times? How do we grapple with and fully acknowledge complexity without falling into either over-complex or over-simplified narratives? Further, are these narratives sufficient in the task of preparing future teachers to imagine and create new worlds after “the end of the world as we know it” (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Andreotti, Suša, Ahenakew and Čajková2022)?

Departing from our experiences as environmental educators in the Pacific Northwest region, we draw from our distinct academic trajectories, experiences and positionalities to engage with those questions. Cristiano positions himself as a Latino science and environmental educator who moved to Canada and is still learning about the Pacific Northwestern region, while bringing his stories of engagement in the struggles for social justice through education in Latin America. Cary positions himself as a white, settler-Canadian, born and raised in East Vancouver, continually learning about the complex colonial history of this region and working to forge life-long connections with the Salish Sea bioregion.

We offer five touchstones that we hope can achieve what we call “simplexity” – or the ability to portray complex and entangled histories and dynamics through simple narratives. We start by delineating the problem (as we see it) that prompts us to respond through writing this paper. Then, we explore the metacrisis construct in relation to concomitant Anthropocene and de/post-growth debates, the main pillars we consider central to building our arguments. Finally, we present five simplex touchstones to guide environmental teacher education, drawing some final conclusions and insights. Methodologically, we position this paper as a conceptual and reflexive synthesis, grounded in our positionality and pedagogical praxis and drawing from literature on post-growth, environmental education/studies, philosophy of education and other relevant literature from our varied scholarship.

Delineating the problem

Human societies currently face a complex paradox that has intensified over time: the climate crisis is here to stay, and its effects are becoming increasingly palpable, albeit unevenly experienced and distributed (Hickel, Reference Hickel2020; Tuholske et al., Reference Tuholske, Caylor, Funk, Verdin, Sweeney, Grace, Peterson and Evans2021). Some social groups and communities are set to suffer more intensely from the consequences of metacrisis than others. We know, for instance, that 6 out of 9 planetary boundaries were already breached in 2023, with serious consequences for the equilibrium of life on Earth (Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Steffen, Lucht, Bendtsen, Cornell, Donges, Drüke, Fetzer, Bala, von Bloh, Feulner, Fiedler, Gerten, Gleeson, Hofmann, Huiskamp, Kummu, Mohan, Nogués-Bravo and Rockström2023). As is well-documented (Davis & Todd, Reference Davis and Todd2017; Lewis & Maslin, Reference Lewis and Maslin2015), the environmental crisis has had an outsized impact on Indigenous communities, the Global South and minorities around the world. Concepts and ideas such as environmental racism (Holifield, Reference Holifield2001), environmental imperialism (Nygren, Reference Nygren, Lockie, A.Sonnenfeld and Fisher2014) and climate justice (Ogunbode, Reference Ogunbode2022), discussed now for decades, already offer articulate accounts of the ways in which these escalating environmental risks are having a larger toll on marginalised communities. On a global scale, the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN) Index, which assesses countries’ vulnerability and readiness to climate change (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Noble, Hellman, Coffee, Murillo and Chawla2023) summarises the unequal scenario: over 85% of the bottom 50 countries in the ND-GAIN index are in Africa or conflict-affected regions, 40 out of 50 lowest-ranking countries are in Africa, and former colonies in the Global South dominates the bottom half of the list. Even if we take such an index critically, considering the unpredictability of climate change, this constitutes important evidence of inequalities on a global scale.

Meanwhile, there is growing awareness that the response to these escalating and diverse crises is not progressing at the necessary pace to address their consequences in the short, medium or long term. Another challenge is that the escalating effects of climate change, coupled with the overwhelming and growing information (infodemic/information abundance) surrounding it (Campbell, Reference Campbell2023), can lead to paralysis. This infodemic can be particularly daunting for a society already experiencing collective disorientation (Means & Slater, Reference Means and Slater2021) on many levels. However, social and ideological paralysis is something that will only worsen the mutually compounding and entangled polycrises we face (Heinberg & Miller, Reference Heinberg and Miller2023; Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Homer-Dixon, Janzwood, Rockstöm, Renn and Donges2024).

At the heart of this situation lies education as a potential catalyst for social change (Freire, Reference Freire1981). How can education be mobilised to maintain and cultivate healthy, flourishing communities and citizens with agency to navigate these challenging times? The central point is to avoid ideological, social and political paralysis, but, at the same time, conveying narratives that are truthful to recent data on climate change and associated crises and that can provide a robust picture of current structural challenges for environmentally just futures. The robust picture we mention includes a deep understanding of cultural, social and political issues entangled with environmental issues.

More than three decades ago, Jickling (Reference Jickling1992) alerted to the philosophical inconsistency of education for “sustainable development,” and the danger of embracing this discourse as a paradigm for EE (Stables & Bishop, Reference Stables and Bishop2001). Furthermore, several critical scholars have taken up a stark criticism of EE from a socio-political angle. However, in recent years, constant refinement of methods, techniques and diverse analyses have brought new data, and further understandings about the limits of growth in our societies (see Meadows & Randers, Reference Meadows and Randers2012), reinforcing discourses such as the impossibility of the green-transition and the UN sustainable development project (Hickel, Reference Hickel2019). Those current discourses and analyses are yet to be fully accepted in educational discourse (Campbell, Reference Campbell, Lacković, Cvejic, Krstić and Nikolić2024) and, even more importantly, educational practices.

Against this backdrop, our proposal in this paper is to address this mismatch between current state-of-the-art discussions in fields such as political ecology, environmental economics (and so on) and teacher education. At the same time, we want to provide a compelling example of how to translate higher-order scholarly discussions into more straightforward and practical orientations to properly facilitate such discussions with prospective teachers in a non-technicist and non-instrumental way, as we will elaborate below. Our hope is that such simplex touchstones will help with prompting agency and avoid paralysis in the face of threatening times.

Metacrisis, anthropocene and other narratives: Keeping the central message

As Campbell (Reference Campbell2023) alerted, data alone will not save us nor touch fundamental questions needing to be addressed if we are to collectively attune to a new regime of respect towards all beings who co-inhabit Earth with us. Beyond the endless task of gathering newer data, chewing it up and communicating it to prospective teachers, we also need concepts and ideas that will help us tell new stories. The Yanomami people resorted to their fellow spirits of the forest, Xapiri, and a falling sky to guide them towards a constant rebalance in their ways of living and in their attunement to a changing Earth. But where are we to turn to build our own local stories? We propose two candidates as foundational conceptual pillars: the Anthropocene debates and the related idea of metacrisis.

The Anthropocene was a term coined by Crutzen and Stoermer (Reference Crutzen and Stoermer2000) to describe a geological epoch characterised by significant human impact on Earth’s geology and ecosystems, marking a departure from the Holocene. As Trischler (Reference Trischler2016) notes, the influence of the proposed geological epoch spanned beyond Geology circles, sparking heated debates in the social sciences and humanities. We know now, in 2025, that the Anthropocene was officially relinquished by the working group tasked with discussing its adoption (Kellner, Reference Kellner2024). Also, several critiques abound about this concept (see Lewis & Maslin, Reference Lewis and Maslin2015; Morton, Reference Morton2014). Why, then, insist on it as a possible pillar upon which to erect propositions for teacher education on environmental issues?

On this note, we want to emphasise that our main motivation for engaging with the Anthropocene concept in our effort to generate simplex touchstones for teacher education is its powerful pedagogical generativity. Through our touchstones, we decided to conceptualise the Anthropocene as a fundamental idea/event instead of an epoch (Edgeworth et al., Reference Edgeworth, Bauer, Ellis, Finney, Gill, Gibbard, Maslin, Merritts and Walker2024), despite (or maybe because of) its contested and disputed nature. Secondly, we want to invite reflection and propose different forms of engagement with Anthropocene-derived concepts in teacher education. There is always a fine line between producing ideas as academic tools “to think with” – including the ongoing process of rethinking and refining those “tools” through study and teaching – and becoming scholarly-machines that ceaselessly carve out and fill in artificial gaps in the literature, creating new concepts that are explored until exhaustion and “throwing them out” when it seems no longer fashionable or simply contested. Such a posture reproduces the very extractivist logic we criticise in modern industrial societies and sometimes seems driven not by philosophical critique but by demands to produce more and create new fronts for academic productivity.

The Anthropocene discussion sedimented an important message: societal behaviour can be conceptualised as a geological force, changing Earth’s systems in ways that may threaten our own species’ (and countless others) existence on the planet. Along with this central message, this conversation reinforced several other themes long highlighted by environmentalists, such as the implicit anthropocentrism (and human exceptionalism) hidden behind many of our assumptions, including the close connections between the great acceleration (Steffen et al., Reference Steffen, Broadgate, Deutsch, Gaffney and Ludwig2015) and ongoing colonisation and capitalist expansion.

The second pillar informing our five touchstones is the concept of metacrisis, which goes beyond what the literature has termed polycrisis. Emerging from the intersection of Anthropocene studies and complex systems research, the idea of polycrisis relates to the context of human-induced environmental changes and how multiple global crises interact and compound with those changes (see Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Homer-Dixon, Janzwood, Rockstöm, Renn and Donges2024; Heinberg & Miller, Reference Heinberg and Miller2023). It is, thus, perceivable through the sum of the more palpable effects of the multiple and entangled crises in the current stage of Modernity. Some authors (e.g. Stein, Reference Stein2022; Rowson, Reference Rowson2021) have observed that the polycrisis is, actually, a symptom of an underlying ur-crisis, a sense of being lost which is experienced collectively and individually. Such a state of mind is derived from a long-term prevalence of narratives of progress, innovation and success – and, with them, imperialism, colonialism in all its forms – that not only drove Earth systems to the current compounding crises, but failed to provide any “map” that could light up paths to exit such crises. In this sense, metacrisis refers not only to the compounding crises that make up polycrisis but also to the more systemic and underlying causes behind them, which are found in the very project of Modernity (Machado de Oliveira, Reference Machado de Oliveira2021).

Importantly, for our purposes, a focus on metacrisis embeds an opening towards post-growth discourses, most directly by offering a perspective to critique business-as-usual growth-based economics with their reductive focus on what has been coined as carbon-tunnel vision (Konietzko, Reference Konietzko2022) – the basic belief, essentially unquestioned in policy and sustainable development paradigms, that these various interconnected challenges of the metacrisis can be remedied by (only) tackling the problem of carbon emissions.

Navigating simplexity in environmental teacher education

The idea of simplexity is conveyed by the word: it is the blend of simplicity and complexity. It comes, however, with an embedded paradox: how can something be complex and simple at the same time if those words are antonyms? A quick search through the literature, however, shows prior use of this idea in various fields, from natural sciences to systems management. For instance, Pina e Cunha and Rego (Reference Pina e Cunha and Rego2010) present the notion of simplexity in organisations, advocating that this idea can help understand organisations as an interplay between complexity and simplicity in their structures and practices (deeper, inner orders of complex systems). Within natural sciences, complexity is often associated with chaotic natural systems – those we (mostly) cannot predict, control and even understand. On the other hand, simplicity is sometimes considered an aesthetic value in science: solutions or general principles that can explain complex phenomena with small and manageable systems of equations or compact explanations, for instance, are considered simple and sometimes even “beautiful” or “elegant” solutions. Some of those ideas, more akin to the natural sciences, were explored by the French scientist Alain Berthoz (Reference Berthoz2012) in his book “Simplexity.”

Whereas those are interesting examples of what is considered simple or complex (and simplex) in other fields, here we want to craft an idea that emerged from one of our multiple talkative walks in Coast Salish peoples’ unceded territories. Some of those conversations stemmed from Cristiano’s struggles to teach a course on Quantitative Perspectives to Environmental Education, which seemed fated to an insensitive datafication and technocratic approach to EE, in place of a more holistic and deeper ecological sensibility. Conversely, such a course on quantitative perspectives seemed like a window of opportunity to bring in recent discussions on post-growth (Kallis et al., Reference Kallis, Hickel, O’Neill, Jackson, Victor, Raworth, Schor, Steinberger and Ürge-Vorsatz2025) regarding the quantification of several aspects of climate change and their causal connections to continued exponential economic growth (see Hickel, Reference Hickel2020).

Discourses like metacrisis and post-growth, though, bring a great deal of complexity to the classroom, which leads us to a second point of reflection: Is there a way to make those extensive and complex discussions palpable and useful to teachers in our (rather truncated and condensed) courses and programmes? All in all, it is important to remember that the ultimate goal of the EE we envision (and maybe the educational project writ large) is to build a habitable world for enabling human and non-human ways of living and being and flourishing, together, on Earth. Thinking about the Yanomami people, they have a consistent story that prompts them to hold the sky and prevent it from falling. How can we, in our local places, story ourselves to hold the sky together with the Yanomami people? In another way, how can we formulate stories capable of portraying the complexity of the many factors involved in considering the (meta)crisis, but in a relatable and direct way? Instead of being a “simplification” of complex narratives, our touchstones aim to offer simplex pathways through which teachers can pragmatically and iteratively begin to explore such complexities in their own contexts. We stress that we have no intention of turning our idea of simplexity into a general theory or principle, and, though offering some pedagogical examples and exploring implications, we refrain from didactically telling teachers what they should be doing. Still, we wish to preserve some degree of simplicity in our touchstones, to avoid the “infodump” effect.

Five simplex touchstones for environmental teacher education

Our five touchstones are simplified narratives inviting complex discussions in teacher education. As we briefly explored above, environmental teacher education faces a unique paradox in a time of metacrisis: while environmental challenges demand immediate action, the complexity of interconnected crises often leads to educational and ideological paralysis. Teacher educators and teachers must navigate between the extremes of oversimplification and overwhelming complexity, particularly in condensed teacher education courses where strong time constraints often force difficult choices about curriculum priorities. This challenge is further complicated by the need to address growing demands for technical information and techno-media literacy alongside deeper ecological sensibilities (as evidenced by Cristiano’s experiences teaching quantitative perspectives in environmental education programmes).

The situation is particularly acute for prospective teachers (and teacher educators), who perhaps more than ever, need to foster intellectual humility in the face of a radically uncertain future. Furthermore, these teachers must be equipped to work with groups of people and students who are often already experiencing climate anxiety and forms of environmental grief, requiring a delicate balance between truthfulness about current environmental realities while retaining critical hopefulness (Benjamin, Reference Benjamin2024) concerning possibilities for change. Amid this complex scenario, as environmental educators, we realised that starting conversations around central themes and motifs that frequently surface when education is confronted with metacrisis may be useful for other environmental teacher educators.

As such, our simplex touchstones embed key openings for pedagogical practice in this time – beyond didactics, these touchstones are about inspiring teachers in their artistry (Eisner, Reference Eisner2002). They are not meant to be summaries foreclosing an end to conversation, but rather openings for further reflection and ultimately, further practice. Because we believe in the method of currere (Pinar, Reference Pinar1975) – emphasising curriculum as lived experience – as a foundational principle in curriculum production, we suggest that teacher educators can adapt and emphasise different aspects depending on their specific positionalities and evolving contexts. The touchstones that follow present simplex heuristics into complex worlds of discourse that teachers can work with, accompanied by brief pedagogical elaborations.

Challenging nature–culture divides & acknowledging alternative ontologies

Perhaps one of the most central aspects of current debates in EE, particularly drawing from the Anthropocene, is the idea of nature–culture divide. Nature–culture divides are pervasively present across almost every aspect of our lives: from the way we classify and relate to all beings to the ways we attune, more broadly, to our surroundings. Viveiros-de-Castro (Reference Viveiros de Castro2015) recounts, based on Lévi-Strauss’s ethnographic observations, the perplexity with which European colonisers faced Amerindian people experimenting with bodies of some European people to understand if they really had a “flesh-and-bones” body, whereas European people were trying to understand whether Amerindian people had souls.

The Anthropocene as a concept and heuristic embeds key narrative openings that challenge implicit nature–culture divides – already embedding a nascent story connecting global human behaviour to geological and planetary timescales. We are invited, through such openings, to question the most fundamental matrices of human thinking. Where do we draw the line between self-other, biology-culture, nature–culture? And further, why do we draw the line as solely starting from a human vantage point? Consequently, many other epistemological and cultural assumptions based on human exceptionalism/anthropocentrism, especially in relation to current capitalist and colonialist narratives, are being actively questioned in the search for more sustainable ways of living and doing.

There are other important narrative openings from which we might consider ourselves a part of nature – a few more all-encompassing than the notion of Gaia. Here, ask – how might we come to understand the evolutionary and ecological emergence of our humanity, and (possibly) come to understand ourselves as part of an interconnected global superorganism, or Gaia? (see Doolittle, Reference Doolittle2017).

Evolutionary biologist Doolittle (Reference Doolittle2024) has recently explored how modern evolutionary theory (stemming from Darwin’s insights) orients us away from believing in or engage with Gaia-based narratives, speaking to how embedded in the various and often “pseudoscience-inspired” and “commercial” narratives behind the concept of Gaia “are perhaps the most important scientific questions facing us as a species at the beginning of the Anthropocene” (p. 177). The point we want to defend is not that a focus on Gaia alone will help us break with nature–culture duality. Rather, we are simply calling attention to other stories that are “out there” that could potentially help in pointing us towards creating more sustainable ways to live with/on Earth/Gaia/Pacha MamaFootnote 1 . As Doolittle (Reference Doolittle2024) proposes, the concept of Gaia is also an opening to consider other stories, such as the early 20th century concept of Noosphere – the understanding that the development of an increasingly interconnected human mind-scape might represent a major evolutionary transition (Deacon, Reference Deacon2023) developed by Henri Bergson, Vladimir Vernadsky and Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. With this first touchstone, we assert the importance of creating opportunities for students to: 1) acknowledge multiple ontologies and worldviews; 2) understand those views (including the current western ones) as embedded in particular ways of being, doing and thinking with impact in our ecosystems, and; 3) creating possible ways forward in crafting story-worlds that are less self-destructive and ultimately more sustainable.

Pedagogical implications

Through exploring diverse nature–culture narratives, teachers can help students move beyond ingrained dichotomies toward a more integrated understanding of human-Earth relationships. This pluralistic perspective is particularly valuable in addressing climate anxiety and environmental grief, as it helps students understand that through acts of storytelling, they exist, not as external observers of environmental problems but as active participants in Earth’s ongoing evolution.

Such story-based pedagogies could, in this regard, go from embodied and somatic exercises of noticing what is around, acknowledging other presences, towards imagining other ways of interacting with “things” we generally “use” like rocks and trees. A conversation, perhapsFootnote 2 ? Some pedagogical openings: what would a river say if we tried actively to understand its/their language (Ford & Blenkinsop, Reference Ford and Blenkinsop2018)? More complex exercises would include actively trying to redraw the lines of Earth’s cohabitants across various and overlapping scales. Such pedagogy is animated through continued questioning: What human-non-human relations are present behind the seedless grape I am eating? How could I reclaim the grapes’ intrinsic value and rights and, consequently, push for change in farming practices and supply chains?

Talking to rocks, trees and rivers, fighting for the grapes’ rights can sound like mere anecdotal fancy to neoliberal advocates, and completely ineffectual in terms of changing structures in our society towards building a more just and fraternal world for all the Earth dwellers. However, it is important to remember that in South America, New Zealand and other places, there are currently pioneering movements to recognise rivers’ rights under the law (Yanquiling et al., Reference Yanquiling, Cuadrado-Quesada and Schmeier2024). In British Columbia, Canada, Indigenous communities are organising themselves to recognise the rights of salmons (Lee, Reference Lee2022) and so on. As Machado de Oliveira and the group “gesturing towards decolonial futures” remind us, though, there is “internal” work to be made so that we can see things differently to act differently (Machado de Oliveira, Reference Machado de Oliveira2021). Those gestures we suggest (only as examples) here can both serve as triggers for significant internal and contemplative work, which itself can and is an impulse for action (Lilburn, Reference Lilburn2023). Gaia, Pacha Mama and other ways of storying the world can help us in the task of creating engaging educational experiences that foster deeper ecological awareness and challenge human-nature divides while avoiding both oversimplification and overwhelming complexity.

Countering pessimistic and one-dimensional views of the present, and accommodating multiple post-growth imaginaries in pedagogy and curriculum

Much time has passed since scholars first started recognising the direct link between the environmental crisis and growth-based capitalism (Kallis et al., Reference Kallis, Hickel, O’Neill, Jackson, Victor, Raworth, Schor, Steinberger and Ürge-Vorsatz2025; cf. Meadows & Randers, Reference Meadows and Randers2012). At the core of capitalist practices is exponential economic growth. Unlike other assumptions, which would put trade and profit as central aspects of capitalist societies, Hickel (Reference Hickel2021), alongside other degrowth and post-growth scholars, argues that infinite growth is the underpinning assumption of those systems. Initiatives to advance environmental protection, like the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), do not challenge those growth-centred narratives (Hickel, Reference Hickel2019). Exploring multiple post-growth perspectives seems crucial to stop and reverse climate upheaval and environmental destruction.

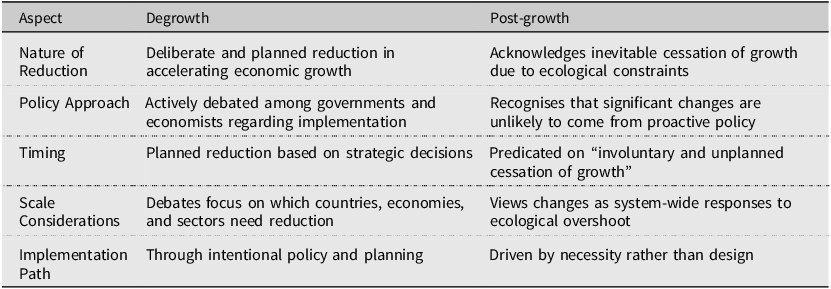

In the last decade or so, we’ve seen a growing movement of researchers starting to consider what post-growth (and degrowth) discourses mean for educational practice and theory in this historical moment (Irwin, Reference Irwin2017, Reference Irwin2024; White & Wolfe, Reference White and Wolfe2022). Degrowth refers to deliberate reduction in accelerating economic growth and overshoot, including often polarising debates around which countries, economies and sectors need to reduce growth and by how much. Acknowledging the long histories and structural inequities underpinning these realities, the post-growth movement generally understands that such changes will be “unlikely to originate from proactive government policy” (Crownshaw et al., Reference Crownshaw, Morgan, Adams, Sers, Britto dos Santos, Damiano, Gilbert, Yahya Haage and Horen Greenford2019, p. 121) and will instead be “predicated on an involuntary and unplanned cessation of growth” (p. 117) brought on by necessity. This reflects some differences in approach and scope between scholars-activist-educators that align more with degrowth rather than those who align with post-growth (see a summary of differences on Table 1). For instance, Kohei Saito’s (Reference Saito2023) recent and popular work on degrowth communism aligns well with degrowth rather than post-growth paradigms, as the Japanese philosopher explicitly advocates political strategies for de-acceleration (slowing down). Again, while the movements are not necessarily or particularly opposed to each other, there are some key differences in orientation, useful for educators to consider:

Table 1. Degrowth vs. post-growth. Source: authors

Through our engagement with post-growth, we acknowledge the structural dimensions underpinning the metacrisis and the fact that slowing down so far proved very challenging in current political landscapes and indeed is not up for serious consideration. The drive for continuing economic growth underpins every aspect of policy and governance (Victor & Jackson, Reference Victor and Jackson2015).

However, simply acknowledging this reality is not in itself a solution. Ruha Benjamin (Reference Benjamin2024) boldly provokes us to take imagination seriously when engaging with worldmaking practices. Currently, most alternatives beyond the horizon of endless growth are simply disregarded as impossible or even ridiculous by many of those currently in power. The degrowth/post-growth conversation is thus educationally necessary, not only to understand the basis of our societies that are driving us to environmental destruction, but also to engage in thinking about futures otherwise. Degrowth proposals can seem absurd in mainstream debates, especially when considering countries with living conditions far from those of the Global North. However, as noted by Kallis et al. (Reference Kallis, Hickel, O’Neill, Jackson, Victor, Raworth, Schor, Steinberger and Ürge-Vorsatz2025), degrowth/post-growth scholars already account for those differences among countries, avoiding one-size-fits-all types of solutions.

Pedagogical implications

For environmental teacher educators, engaging with post-growth/degrowth perspectives can allow for a fuller recognition of the interconnected challenges underpinning the metacrisis. This said, degrowth/post-growth proposals are often regarded as inherently skewed in our current, rapidly politically polarising climate. Still, we understand that with good supporting data and well-grounded curriculum resources, it can be possible to reestablish a well-reasoned debate over current conditions with the aim of cultivating diverse new post-growth imaginaries not currently on the horizon of the wider public.

For instance, teachers can guide students through the distinction between degrowth (deliberate reduction in economic growth) and post-growth (acknowledging inevitable social – ecological constraints that effectively lock us into growth-based ways of living) to arrive at a fuller and more nuanced understanding of our current predicaments. Pedagogically, this could mean having prospective teachers: conduct their own inquiry projects; engage in flipped classroom activities as well as have open debates guided by well thought out provocations and prompts informed by current literature on degrowth/post-growth. Discussing the different policy agendas and ideological stances behind these differences between post and de-, embeds important reflective-dialogical openings, as student-teachers are directed to consider their own orientations, by connecting and synthesising their values and hopes for the future with their own ability to act (or not act) in their current conditions and contexts (Pinar, Reference Pinar2022).

On the imaginative storying side, research on current growth-based ways of living can nurture our ability to imagine diverse and multiple post-growth futures. Here, it is important to consider our own local contexts as well as, importantly, the ways that people in other cultures and parts of the world live. For instance, Cary frequently employs post-growth futures storying exercises with student-teachers. This involves considering our local place of Vancouver and the Lower Mainland, by first attending 7 generations in our regions’ past (the regressive stage in the method of currere), followed by thinking seven generations in the future (progressive stage). Such an activity embeds all kinds of reflective considerations and conversational openings – for instance, students consider how many river and stream networks were diverted, filled in and buried in the development and colonisation of our city and region through the late 19th and early 20th century, then; how local extreme flooding events (floods of November 2021) resurfaced past lakes and rivers; and, finally, how the effects of climate change will likely resurface many of these (nascent) water-bodies and how we might learn to live in this new environment by adopting Indigenous practices of living in close relation to water-ways.

As Santos (Reference Santos, de S. Santos and Meneses2009) argues, prevailing paradigms assume that no valid knowledge exists outside established ways of knowing and living. Yet the world is diverse, and countless ways of life exist beyond the megacities and consumer-driven societies often viewed as the pinnacle of civilisation. These societies are frequently seen as the natural endpoint for any region seeking to provide wellbeing for its people. However, our current concept of “wellbeing” is largely shaped by capitalist ideals, and in the face of environmental crises, we lack the imagination to propose alternatives. Learning about diverse ways of living, including Indigenous worldviews and those buried by colonization machines, can therefore help nurture the imaginative capacity needed to build post-growth futures.

In short, engaging with this touchstone helps student-teachers develop critical perspectives on current economic systems while exploring alternative futures beyond traditional growth paradigms. By examining both the current state of affairs, planned reductions and necessary transitions, student-teachers learn to navigate complex discussions about economic transformation and environmental sustainability, while imagining and opening to new horizons that are currently being disregarded due to the huge changes needed in people’s lifestyles, especially in high-income countries.

Acknowledging the great acceleration and ecological overshoot

Building on Steffen et al.’s (Reference Steffen, Broadgate, Deutsch, Gaffney and Ludwig2015) work on the Great Acceleration and Rees’s (Reference Rees2023) work on ecological overshoot, this touchstone helps teachers frame environmental challenges within the context of rapid planetary-scale changes. Engaging with both constructs can help students explore how activities of some groups of humans (and associated corporations) have accelerated to impact Earth’s systems at unprecedented scales, leading to measurable forms of ecological overshoot. This third touchstone invites bridging abstract and hard-to-relate-to concepts like planetary boundaries by connecting them to tangible (local-global) environmental impacts.

As alluded to above, post-growth discourse is premised on acknowledging the realities of the Great Acceleration and ecological overshoot, “a state in which excess consumption and pollution are eroding the biophysical basis of our own existence” (Rees, Reference Rees2023, p. 16). Population ecologists such as William Rees have offered clear methods for measuring overshoot, such as Ecological Footprint Analysis (See: Rees & Wackernagel, Reference Rees and Wackernagel2023; Wackernagel & Rees, Reference Wackernagel and Rees2004), which clearly correlates increasing consumption and population growth with appropriated land-use.

Here, another concept and heuristic enter the conversation: Unravelling. Unravelling can be explained quite simply as the natural outcome of acceleration: as we reach certain planetary thresholds and boundaries (Steffen et al., Reference Steffen, Broadgate, Deutsch, Gaffney and Ludwig2015) the Great Acceleration will start to slow and recede, which will result in widespread forms of social and environmental unravelling, which, has been recently called The Great Unravelling (Heinberg & Miller, Reference Heinberg and Miller2023; cf. Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Homer-Dixon, Janzwood, Rockstöm, Renn and Donges2024).

In the same note, Richardson et al. (Reference Richardson, Steffen, Lucht, Bendtsen, Cornell, Donges, Drüke, Fetzer, Bala, von Bloh, Feulner, Fiedler, Gerten, Gleeson, Hofmann, Huiskamp, Kummu, Mohan, Nogués-Bravo and Rockström2023) remarked that Earth has crossed several planetary boundaries critical for maintaining a stable and habitable environment, including climate change, biodiversity loss, freshwater overuse and chemical pollution (e.g., plastics and pesticides). These boundaries, for those authors, represent safe operating limits beyond which ecosystems face irreversible damage, threatening human wellbeing and planetary health. The most alarming transgressions include biodiversity decline, with species extinction rates far exceeding natural levels and climate change driven by excessive CO2 emissions. Freshwater systems are being depleted faster than they can replenish, while novel materials like synthetic chemicals disrupt natural processes. Richardson et al. (Reference Richardson, Steffen, Lucht, Bendtsen, Cornell, Donges, Drüke, Fetzer, Bala, von Bloh, Feulner, Fiedler, Gerten, Gleeson, Hofmann, Huiskamp, Kummu, Mohan, Nogués-Bravo and Rockström2023) create a new framework that allows us to understand the current state of ecological overshoot and what the risks are for planetary health.

The discussion on the great acceleration and ecological overshoot is not detached from the previous touchstone on post-growth/degrowth distinctions and how education might cultivate new post-growth imaginaries. However, we understand that the great acceleration and overshoot are a crucial point to be emphasised with teachers, showcasing critical aspects of the metacrisis. In the spirit of simplexifying our narratives, some aspects must be emphasised if one wants to prompt agency. And of course, acknowledging ecological overshoot opens a critical space for thinking of ways to live within the boundaries (cf. Kallis et al., Reference Kallis, Hickel, O’Neill, Jackson, Victor, Raworth, Schor, Steinberger and Ürge-Vorsatz2025) of our mother Earth.

Pedagogical implications

Ecological footprint analysis (EFA) is a method that inherently embeds pedagogical applications – and can be incorporated into the curriculum as early as grade 4 or 5. EFA can be brought into the classroom as a relatively simple way in which students can conduct analysis upon both their own “footprint” and the footprint” of their region. Such analysis can open simplex dialogues around the role and impact of individual and societal responses in reducing our ecological footprint. Fascinatingly and relevant to our context, EFA was first applied to our own lower mainland region of Vancouver – revealing the empirical conundrum that our region was already in overshoot as far back as the 1970s (Rees et al., Reference Rees, Campbell and Hoeller2024). It is an interesting analysis to compare, for instance, trends across different moments in time and to spark critical and reflective conversations – how have our ways of living in this land changed over time, and how do they relate to less destructive ways of cohabiting the world with other species? This kind of pedagogy begins, again, with questioning: how much land and resources do we need to sustain our current metropolitan region? Can we sustain such ways of living? How can we regenerate what was lost due to modernity’s fixation on the narrative of progress? Embedding other smaller questions, such as “where does our food and water come from?.” In thinking about the future, how do our decisions on how to structure our ways of living impact Earth’s cohabitants?

We must emphasise that we take EFA as a starting point for asking hard questions about ecological overshoot. If it is true that this framework allows us to assess our individual ecological footprints, it is not where the analysis ends. We must ask: who is benefitting from overshoot, what systems are in place that prevent us from reducing our EFs, and who (taking here a stance to acknowledge the more-than-human kin and other marginalised populations worldwide) is suffering on a global scale because of our EFs? Applying EFA in the classroom shows, unambiguously, how reliant we are on other parts of the world for what we eat and consume, by directly correlating the ecological costs of our lifestyles with the amount of usable land required to sustain them. Whereas EFA can prompt immediate action related to what one buys, where one travels, and how one commutes daily, one needs to remember that the action must confront structures of oppression so that we can dismantle the system that, on a global scale, is undermining our wellbeing.

Acknowledging power dynamics and inequities across metropolis to periphery due to continued colonialism

Following from the previous touchstone, it is noted that ecological overshoot is not evenly contributed to by all Earth dwellers: while the ecological footprint of high-income, industrial nations may be very high, there are communities and nations with very small footprints from where, often and very likely, many of the raw and critical resources that high-energy-consuming nations need come from. As historical studies on colonialism emphasise, and more recently quantitative studies such as Hickel et al. (Reference Hickel, Sullivan and Zoomkawala2021), this unequal exchange shaped the way the modern world is hierarchised (even after the historical colonialism), meaning that overshoot in some (mainly global-north) countries is historically tied to drain from other parts of the world (mainly the global-south). This is not only true from a global perspective, but also at local scales, as the dynamics are perpetuated and reproduced by local elites who expropriate local populations and resources in an internal process of colonialism (Rivera Cusicanqui, Reference Rivera Cusicanqui2010). The world’s resources are finite – thus, over-expending always comes with a consequence of scarcity somewhere, even when unnoticed.

This touchstone emphasises understanding environmental challenges through the lens of metropolis-periphery relationships. This touchstone naturally builds off touchstone 3, in the sense that, with a greater and more nuanced understanding of how ecological overshoot connects the local with the global, student-teachers are better prepared to tackle the complicated North-South dynamics underpinning overshoot and accelerated growth. The framework of metropolis-periphery derives from research into imperialism and colonialism, by Patnaik & Patnaik (Reference Patnaik and Patnaik2016; Reference Patnaik and Patnaik2021). By acknowledging these power structures through the lens of metropolis-periphery dynamics, student-teachers can develop nuanced perspectives on environmental justice and inequality, recognising how seemingly local environmental issues connect to broader global (and sometimes local, or even glocal) patterns of resource distribution and political influence.

Pedagogical implications

The advantage of framing the conversation around metropolis-periphery dynamics, rather than the more common global-south/global-north distinction, lies in the fact that the former accommodates many embedded, intersecting scales. For instance, Lagos is certainly a metropolis in the West African and Nigerian context, extracting resources (and through this, land) as well as labour from its own periphery. Still, and at the same time, Lagos has historically been subjected to the domain of periphery in the context of colonial European metropolises, chiefly London, which exercises an extractive relationship with many of its former colonies across what is often referred to generically as the Global South.

Another example that can serve as an entry point into this conversation: the history of commodities travelling the global market. A simple example was when Cristiano lived in a city in Rio de Janeiro state, in Brazil, once known as a place for buying cheaper (and good quality) clothes because of local manufacturing. After years of competition with international traders, many local manufacturers closed their doors, resulting in most local clothes being imported from abroad. Teachers can bring pedagogical attention to the environmental (and social) consequences of transporting such products from long distances as opposed to local production and commercialisation. Across globalised economies, this story bears a striking resemblance to many other places around the world, including Canada.

Another opportunity to explore the global-local and metropolis-periphery dynamics is the consequences of local environmental pollution/damage (or, conversely, conservation) on global climate and global ecological patterns. Heat waves, ocean acidification and the impact on marine life, among other environmental challenges, have well-documented analyses about the local-global dynamics. Stemming from those challenges (and crucial to the discussions related to them), we have the whole politics of climate change in the form of different proposals on how to tackle those global problems. All of this ties back very closely to the proposals put forward by post-growth scholars, as discussed in the first touchstone. This touchstone serves as a reminder that the sky above our heads is the same as the one the Yanomami people refer to, even though, historically, some (as the Yanomami people) have kept this sky from falling, some humans and corporations seem to care less about preserving this same sky.

Acknowledging aesthetics and the politics of sensible-embodied experiences, particularly our experiences of climate-related disasters

As noted by Machado de Oliveira (Reference Machado de Oliveira2021), the change we need is not a technocratic cycle of policies and practices deriving exclusively from data, but a reorientation of our sensibilities and sense of attunement with the Earth/ourselves. Earth is changing, and we can feel, hear, see and smell it. We can feel it through the heatwaves and moments when we notice the weather is decidedly very different from what we used to experience in each season; we can smell the smoke of the growing wildfires across the world. We can see this when encountering a species that was previously confined to its territory but now has no choice but to reach urban spaces to find food. Those are disasters, slow violent disasters (Sharma & Kalyanaraman, Reference Sharma, Kalyanaraman and Moura2025) in our metacrisis, piling up on top of other well-known disasters that are happening on a growing scale all over the world. Those disasters have deadly consequences for many places with limited infrastructure to resist those occurrences, as well as for places with more developed infrastructures. This final touchstone focuses on the sensory and aesthetic dimensions of environmental education. With this touchstone, we encourage teachers and students to engage with climate-related phenomena through focusing on direct embodied experiences and sensory observation, in the interest of developing a “politics of sensible-embodied experiences.” Arguably, according to current research in environmental education (see Bentz, Reference Bentz2020), those are fundamental to re-attune us to environmentally sustainable ways of living.

Pedagogical implications

Our sensory experiences are fundamental entry points to important discussions in environmental education. Cristiano, for instance, experienced a very traumatic incident in Petropolis, in 2022, when a flash flood and a series of landslides in Petropolis city killed more than 250 people. A large landslide in a mountain behind his own residence made headlines (with photos and videos of all sorts) as the deadliest landslide on that day. After that, forest glades in the mountains were never seen the same way. The relationship with mountains changed for Cristiano in a way that now those glades feel like scars that hurt as much as remembering the events that unfolded that day. What may be the stories behind those glades? Beyond the trauma of remembrance, this different way of seeing mountains also prompted Cristiano to feel, for instance, the traces of mining in the mountains of Agassiz, a region of British Columbia, as wounds that also hurt, in a different way.

This touchstone has the affordance of grounding abstract environmental concepts in personal experience while acknowledging the emotional and psychological dimensions of environmental learning, helping students build deeper connections between theoretical knowledge and their lived reality.

For instance, people might know, at least on an intellectual level, many ways in which their current lifestyles are unsustainable. For example, one may know many facts about the massive and destructive petroleum industry lobbying behind the creation and continued proliferation of single-use plastics. All this said, somebody otherwise completely informed on the deleterious effects of single-use plastics may only be motivated to change their behaviour because of an aesthetic regime or preference that effectively categorises single-use plastics as aesthetically undesirable or unbeautiful. This reflects the longstanding philosophical perspective that aesthetics is always decidedly political (Ranciere, Reference Rancière2003).

Hoping for new beginnings…

It is important to note that the five touchstones we present are not linear nor hierarchical but rather entangled openings for deepening teacher practice in environmental teacher education. One could argue, for instance, that awareness of ecological overshoot underpins all subsequent discussions on degrowth and post-growth, which is certainly true, at least from a certain analytical vantage point. However, one could respond that the ecological overshoot crisis must be historically linked to the 500-year history of colonial-imperialist land-grabs. This is also very true. What’s important is that there are many openings and pathways into this pedagogical work -- each touchstone embeds simplex take-home messages we encourage teachers to work with. We stress that there is no single way to proceed in this work, nor a single place to start.

Our hope is that these touchstones can help teachers navigate the paradox of simplicity and complexity in environmental education, inspiring new narratives and practices without succumbing to either oversimplification or overwhelming complexity. We crafted these touchstones in relation to the concepts of metacrisis and Anthropocene, aiming to acknowledge the complexity of the themes that environmental education must address in the current times, confronted with the limits of growth.

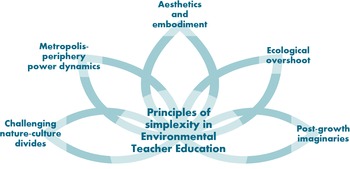

In conclusion, we summarise the five touchstones of simplexity for environmental teacher education with a graphic representation below (Figure 1), based on a lotus flower.

Figure 1. A graphic representation of the five simplex principles for environmental teacher education. Source: authors.

We decided not to over-elaborate this diagram to maintain the original idea of simplexity, i.e., simple narratives inviting complex discussions with actionable pedagogical implications. Each of these short phrases alludes to the five touchstones we elaborate on in this paper. We are inspired by the fact that the beautiful lotus flower can bloom from mud and is resilient even in harsh conditions. Be that the inspiration to put into action the simplexity principles we proposed in this contribution, hoping that many of the examples we used throughout the paper will contribute to a brighter future, where the sky is not only in its place, but shines for all Earth dwellers.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the reviewers and editors for their helpful feedback on previous versions of this work.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical statement

Nothing to note.

Author Biographies

Dr. Cristiano Barbosa de Moura is an Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Education at Simon Fraser University. His work as a science educator bridges historical approaches to science with cultural lenses and socio -political perspectives in science education, promoting justice-centred approaches in K-12 settings and teacher education. Dr. Moura’s research, which has been published in journals such as Science & Education, Science Education and Cultural Studies of Science Education, focuses on developing theoretical and practical approaches to science that challenge the current boundaries of school science and interrogate science production to foster more inclusive and critical pedagogies and socially conscious scientific practices. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Science & Education and recently edited the book “A Sociopolitical Turn in Science Education” published by Springer.

Dr. Cary Campbell is a Lecturer in the Faculty of Education at Simon Fraser University, where he also completed his SSHRC-funded PhD in Arts Education in 2020. His work as an educational theorist, curriculum scholar and music educator bridges biosemiotics, posthumanist theory and place-based pedagogy to address the existential and ecological challenges of the Anthropocene. Dr. Campbell’s research, which has been published in journals such as the Journal of Philosophy of Education and Postdigital Science & Education, focuses on developing critical eco-pedagogies and post-growth imaginaries for a time of social and environmental unravelling. This work extends into community engagement through his role as Director of Research for The New Curriculum Group, where he collaborates to create curriculum resources that foster local and bioregional connections. An active musician and editor for the Journal of Contemplative and Holistic Education, Dr. Campbell’s scholarship is fundamentally committed to reconceptualising education within planetary limits.