Introduction

As herbicide resistance spreads worldwide, applying herbicides before weeds emerge assumes a critical role in weed management. These herbicides not only minimize weed interference but also facilitate crop establishment, thereby alleviating the need to apply postemergence herbicides (Jhala et al. Reference Jhala, Sandell and Kruger2014). Among the preemergence herbicides, those that inhibit very-long-chain fatty acid (VLCFA) elongase (categorized as Group 15 herbicides by the Weed Science Society of America [WSSA]) have been used for the past 60 yr to manage grass weeds in primary crops worldwide (Busi Reference Busi2014). This herbicide group prevents weed emergence and growth by inhibiting shoot development in susceptible species (Jhala et al. Reference Jhala, Singh, Shergill, Singh, Jugulam, Riechers, Ganie, Selby, Werle and Norsworthy2023). Their primary activity targets annual grass, but they also provide effective suppression of small-seeded broadleaf weeds. However, differences in the responses to herbicides by grass species have been demonstrated by, for example, Eckermann et al. (Reference Eckermann, Matthes, Nimtz, Reiser, Lederer, Böger and Schröder2003). This variability suggests that enzymes involved in plant metabolism may heavily influence how these herbicides control the target species. Soltani et al. (Reference Soltani, Brown and Sikkema2019) also demonstrated that the efficacy of various VLCFA-inhibiting herbicides varied between green foxtail [Setaria viridis (L.) P. Beauv.] and barnyardgrass [Echinochloa crus-galli (L.) Beauv.] species.

The existing literature indicates that larger seeds exhibit better survival after an herbicide application, which potentially reduces the effectiveness of soil-residual preemergence herbicides (Darmency et al. Reference Darmency, Colbach and Le Corre2017; Maity et al. Reference Maity, Lujan Rocha, Khalil, Bagavathiannan, Ashworth and Beckie2022; Yanniccari et al. Reference Yanniccari, Vila-Aiub, Istilart, Acciaresi and Castro2016). These findings demonstrate that several factors, including the size of the target weed seeds, can affect the efficacy of herbicide control. However, limited information exists in the literature about the relationship between the efficacy of VLCFA-inhibiting herbicides and the seed size of gramineous weeds. Therefore, the objective of this study was to compare the efficacy of four VLCFA elonagase–inhibiting herbicides applied preemergence to two gramineous weeds, large crabgrass and Texas panicum, which produce seeds of different sizes.

Materials and Methods

Field studies were conducted at the E.V. Smith Research and Extension Center in Macon County, Alabama (32.426873°N, 85.884116°W) during June and July of 2022, and at the Wiregrass Research and Extension Center in Henry County, Alabama (31.358370°N, 85.318742°W), during June and July of 2022 and 2023. The fields at each location were conventionally prepared, and large crabgrass and Texas panicum seeds were individually spread onto tilled plots measuring 1.83 m by 1.83 m, with 1.83-m buffers between plots. Seed densities for crabgrass and Texas panicum were approximately 4,400 seeds m−2 and 1,930 seeds m−2, respectively. The seed of Texas panicum is approximately five times larger than crabgrass seeds, with a 1,000-seed weight of 0.63 g for large crabgrass compared with 3.46 g for Texas panicum. Thus, more large crabgrass seeds were applied given the smaller size of large crabgrass compared with Texas panicum.

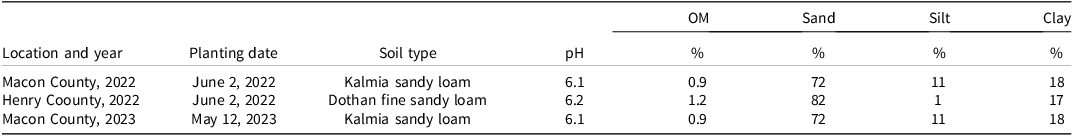

This study was conducted in a non-crop scenario in which only weed seeds were planted. The seeds were incorporated into the soil to a depth of 3 to 4 cm using a rotary tiller. To ensure homogeneity of species that existed in the plots, plots were hand-weeded as needed to remove all other weed species. Details regarding soil type and planting dates for each location are shown in Table 1. The experimental units were arranged in a completely randomized block design with four replications.

a Abbreviation: OM, organic matter.

b Soil type information was provided by Auburn University Soil Testing Laboratory (Auburn, AL).

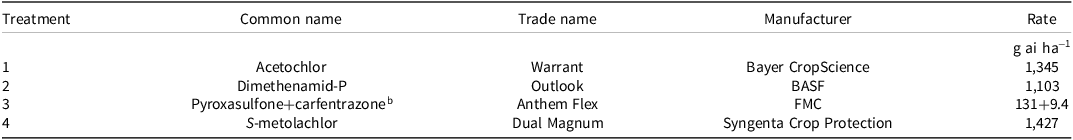

At each location, herbicides were applied immediately after crops were planted with a CO2-pressurized backpack with a four-nozzle boom using AIXR 11002 wide-angle flat-fan nozzles (Teejet Technologies, Glenmont Heights, IL) at a spray volume of 140 L ha−1 at 4.83 km h−1. All locations received at least 12.5 mm of precipitation within 24 h of herbicide applications via either irrigation or rain. Treatments consisted of acetochlor, dimethenamid-P, pyroxasulfone + carfentrazone, and S-metolachlor. Product brands and herbicide rates used in the study are shown in Table 2. In this study, the premix of pyroxasulfone + carfentrazone (Group 15 + Group 14) was included to represent a commercially available and widely used VLCFA-inhibitor option. The treatment comparisons focus on Group 15 residual activity across treatments.

Table 2. Herbicides and rates used in the study. a

a Specimen labels for each product and mailing and website addresses of each manufacturer can be found at www.cdms.net.

b Commercial premix contains pyroxasulfone (Group 15) and carfentrazone (Group 14).

Data collection consisted of four parts. First, plot visible control ratings of each weed species with the range of 0% to 100% (0% = no control, 100% = complete control) were obtained at 14, 28, and 42 d after treatment (DAT). Second, stand counts of each weed species were obtained by assessing two 61- by 61-cm quadrats randomly placed at each plot at 14, 28, and 42 DAT. Third, biomass data were collected for each weed species at 42 DAT. Grass biomass was harvested with a handheld hay cutter throughout the entire plot. After harvest, the collected biomass was placed in an air circulation oven adjusted to 75 C until samples reached a constant weight. The dried biomass was then weighted on a scale and recorded for dry mass values. Fourth, five normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) readings were randomly collected per plot using a GreenSeeker handheld crop sensor (Trimble Inc., Sunnyvale, CA) along with multispectral imaging from a DJI Mavic 3 multispectral drone (DJI; Shenzhen, China) on the entire plot 42 DAT as a plant health indicator. Image data were analyzed with QGIS software (v.3.22; Geographic Information System, QGIS Association).

Biomass, stand count, and NDVI data were converted to percentages of the nontreated control (NTC) before statistical analysis. All data were subjected to ANOVA using the GLIMMIX procedure with SAS software (v.9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Treatment and site were considered fixed effects, while replication was the random effect. If the interaction was significant, data were analyzed and presented separately by location. All means were separated using a Tukey HSD test at α = 0.05 to indicate statistical differences.

Results and Discussion

Visible Control

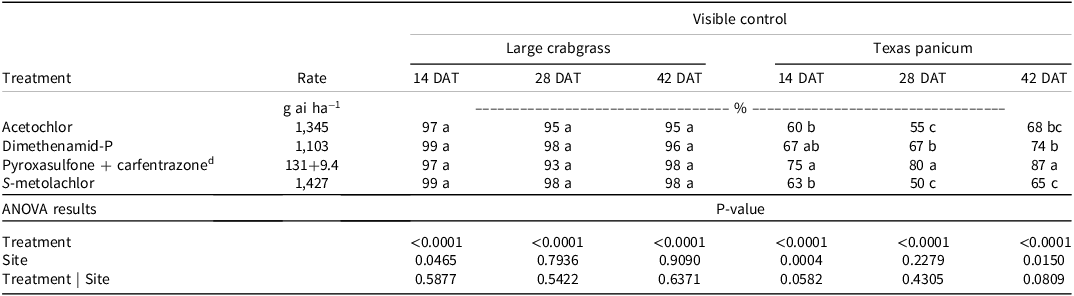

Analysis of control revealed no site by treatment interaction (P = 0.05) for both grass species, and thus data for all site-years were combined and analyzed together (Table 3). Treatment differences were observed at each rating time. All treatments provided good control (>94%) of large crabgrass. All treatments provided more than 94% control of large crabgrass at all rating dates. In contrast, Texas panicum was more challenging to manage. Pyroxasulfone + carfentrazone provided the greatest control of Texas panicum, although control did not exceed 80% during the rating period. Dimethenamid-P provided the second-highest level of control of Texas panicum, followed by acetochlor and S-metolachlor across all ratings.

Table 3. Large crabgrass and Texas panicum control as affected by VLCFA herbicides over 4 site-years. a–c

a Abbreviations: DAT, days after treatment; VLCFA, very-long-chain fatty acid.

b Means followed by the same letter in the same column do not (P = 0.05).

c Results were rounded without exceeding the decimal point.

d The commercial premix contains pyroxasulfone (Group 15) and carfentrazone (Group 14).

Soltani et al. (Reference Soltani, Brown and Sikkema2019) observed variation in control efficacy among gramineous weeds, with pyroxasulfone at 100 g ai ha−1 achieving up to 70% control of green foxtail but only 54% control of barnyardgrass at 8 wk after treatment, which aligns with the crabgrass and Texas panicum control observed in this study. Conversely, pyroxasulfone applied at rates of 125 to 250 g ai ha−1 was reported to suppress barnyardgrass by 93% to 100% as reported by Stephenson et al. (Reference Stephenson, Bond, Griffin, Landry, Woolam, Edwards and Hardwick2017) and Yamaji et al. (Reference Yamaji, Honda, Kobayashi, Hanai and Inoue2014). In our study, variation in control of Texas panicum may be associated with its large seed size, leading to diverse responses to different herbicides.

Stand Count

Analysis of stand count revealed no site by treatment interaction for both grass species, and thus data from all site-years were combined and analyzed together (Table 4). None of the treatments significantly affected the stand count of either large crabgrass or Texas panicum across all ratings. However, a consistent trend was observed for both grass species. Crabgrass stand count remained consistently low across rating dates (up to 4% of NTC at 42 DAT), indicating high efficacy of VLCFA against this weed. In contrast, Texas panicum exhibited more tolerance and thus stand counts were higher than those of crabgrass at each rating, but stand count still decreased over time. Consistent with our findings, previous literature has demonstrated that weed species with larger seeds tend to exhibit accelerated growth and higher dormancy, potentially evading preemergence herbicide control (Maity et al. Reference Maity, Lujan Rocha, Khalil, Bagavathiannan, Ashworth and Beckie2022). This suggests a reason for the higher stand count of Texas panicum observed at 14 DAT, as well as the subsequent decrease noted in the final rating. Environmental factors such as water availability during the progress of the experiment may also have influenced these fluctuations across Texas panicum ratings.

Table 4. Large crabgrass and Texas panicum stand count as affected by VLCFA herbicides over 4 site-years. a–c

a Abbreviations: DAT, days after treatment; VLCFA, very-long-chain fatty acid.

b Means followed by the same letter in the same column do not differ significantly based on analysis of variance of a randomized complete block (P = 0.05). Data are expressed as a percentage of the nontreated control.

c Results were rounded without exceeding the decimal point.

d The commercial premix contains pyroxasulfone (Group 15) and carfentrazone (Group 14).

Biomass

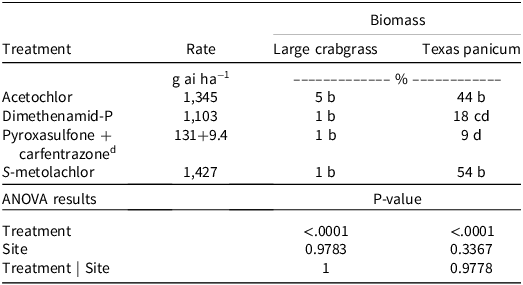

Analysis of biomass revealed no site by treatment interaction for either grass species and thus data were combined for all site-years and analyzed together (Table 5). Consistent with visible control data, all treatments to control crabgrass exhibited significantly lower biomass, with all VLCFA herbicides effectively reducing biomass to less than 5% of the NTC. In contrast, Texas panicum exhibited variations in control, with pyroxasulfone + carfentrazone and dimethenamid-P providing the greatest biomass reduction, followed by acetochlor and S-metolachlor. According to research by Soltani et al. (Reference Soltani, Brown and Sikkema2019), green foxtail dry weight reduction ranged from 63% to 93% when dimethenamid-P, pethoxamid, pyroxasulfone, and S-metolachlor were applied to a soybean field. In our study, biomass was a more reliable indicator of herbicide efficacy than stand counts, because stand counts indicate only the presence of weedy plants, not their productivity. In contrast, biomass provides a comprehensive measure of the actual mass of the living plant material, which offers a more accurate reflection of herbicidal impact on the overall health and growth of weeds.

Table 5. Large crabgrass and Texas panicum biomass affected by VLCFA herbicides over 4 site-years at 42 d after treatment. a–c

a Abbreviations: DAT, days after treatment; NTC, nontreated control.

b Means followed by the same letter in the same column do not differ significantly based on analysis of variance of a randomized complete block (P = 0.05). Data are expressed as a percentage of the NTC.

c Results were rounded without exceeding the decimal point.

d The commercial premix contains pyroxasulfone (Group 15) and carfentrazone (Group 14).

NDVI Values

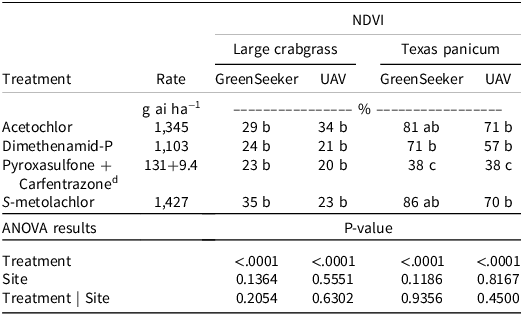

Analysis of NDVI data revealed no site by treatment interaction for either grass species and both types of equipment, thus data were combined across site-years and analyzed together (Table 6). Consistent with visible control evaluations and biomass data for crabgrass, all treatments yielded low NDVI values, ranging from 18% to 35% relative to the NTC, according to both the handheld GreenSeeker and a drone. Notably, pyroxasulfone + carfentrazone exhibited the lowest NDVI value by Texas panicum compared with any other product, followed by dimethenamid-P with the second lowest value. NDVI was significantly reduced with applications of acetochlor and S-metolachlor only when measured by drone but not with the GreenSeeker. While visible estimates may vary between observers, NDVI readings can provide objective data (Dicke et al. Reference Dicke, Jacobi and Büchse2012), particularly when used in conjunction with visible ratings. Moreover, camera drones offer an alternative for assessing plant health and can cover larger areas efficiently. Prudente et al. (Reference Prudente, Mercante, Johann, de Souza, Oldoni, Almeida, Becker and Da Silva2022) reported a significant correlation between NDVI values obtained from GreenSeeker and sensors attached to drones. Additionally, Bautista et al. (Reference Bautista, Tarrazó-Serrano, Uris, Blesa, Estruch-Guitart, Castiñeira-Ibáñez and Rubio2024) demonstrated the utility of NDVI values as a reliable indicator of plant growth and their ability to validate the effectiveness of herbicide treatments. In alignment with our study, both equipment types demonstrated statistical similarity across all products and grass species, indicating their reliability and precision in generating plant health indicators. However, in this study, drone-based NDVI measurements were more accurate in assessing Texas panicum control and for differentiating among treatments than the handheld GreenSeeker.

Table 6. Large crabgrass and Texas panicum NDVI affected by VLCFA herbicides over 4 site-years at 42 d after treatment. a–c

a Abbreviations: NDVI, normalized difference vegetation index; NTC, nontreated control; UAV, unmanned aerial vehicle.

b Means followed by the same letter in the same column do not differ significantly based on analysis of variance of a randomized complete block (P = 0.05). Data are expressed as a percentage of the NTC.

c Results were rounded without exceeding the decimal point.

d The commercial premix contains pyroxasulfone (Group 15) and carfentrazone (Group 14).

Practical Implications

Gramineous weeds pose significant challenges to field crop production, especially in crops with limited herbicide tolerance. This study highlights the utility of applying preemergence herbicides to minimize weed pressure and reduce the need for postemergence treatments, which are less effective on larger weeds. The findings demonstrate that the efficacy of Group 15 herbicides may vary based on grass weed seed size, with pyroxasulfone + carfentrazone providing superior control of larger-seed species such as Texas panicum. These insights can help growers select the appropriate Group 15 herbicide based on the target weed species, thereby improving early-season weed control and enhancing crop competitiveness. Additionally, the study demonstrates that NDVI measurements with drones offer an accurate, labor- and time-saving tool for evaluating weed control in field research.

Funding

Financial support for this work was provided by FMC, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Competing Interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.